User login

Whole blood PCR improves diagnosis of pediatric bacterial sepsis

MADRID – Whole blood multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) holds considerable promise as a rapid noninvasive test to improve diagnosis of life-threatening bacterial infections in children with suspected sepsis yet negative blood cultures, Clare Thakker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

There are several disadvantages with blood cultures – the current diagnostic standard. The turnaround time is 48 hours or longer. Moreover, false-negative culture results are common because of prior antibiotic therapy. And blood cultures require a considerable amount of blood, which becomes an issue in younger children with small blood volumes. Whole blood PCR is unfettered by these limitations, and it could reduce the need for invasive sampling, such as pleural or joint aspiration or CSF sampling, in blood culture–negative children, observed Dr. Thakker of Imperial College London.

The challenge posed by febrile children is that even though the vast majority will turn out to have a self-limited viral illness, a small proportion will have a life-threatening bacterial infection. And distinguishing between the two groups in timely fashion often remains difficult today, the pediatrician said.

Dr. Thakker reported on 504 EUCLIDS participants with suspected sepsis who had blood cultures and whole blood PCR testing done on the same day. The multiplex PCR, developed by Micropathology of Coventry, England, was set up to test simultaneously for five clinically important bacterial pathogens: Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae. Prior to testing, the blood samples underwent lysozyme/lysostaphin digestion and silica bead disruption in order to break down cell walls and facilitate nucleic acid extraction.

Of the 504 children with suspected sepsis, 438 (87%) had negative blood cultures, among whom were 326 patients (74%) with clinically suspected or definite bacterial infection. The PCR test identified one of the five target pathogens in 25 of the 326 patients (8%) where physicians suspected bacterial sepsis despite negative cultures. Ten blood culture-negative patients (40%) were whole blood PCR positive for N. meningitidis, 6 (24%) for H. influenzae, 5 (20%) for S. pneumoniae, 3 (12%) for S. aureus, and 1 (4%) for S. pyogenes. Three of the 25 positive tests showed poor clinical correlation consistent with environmental contamination. The other 22 positive PCR results were consistent with the patient’s clinical syndrome – for example, N. meningitidis being found in the blood of a child with meningeal encephalitis – or concordant with the results of a culture obtained invasively at a sterile body site.

Ninety-two patients with negative blood cultures were culture positive for a causative bacterial pathogen obtained by invasive sampling of a sterile body site such as the CSF. In 68 of these 92 cases (74%), the pathogen was among those on the multiplex PCR panel.

“Our study results bring into question whether blood culture should be the gold standard; clearly, blood culture is not capturing everything. Our findings also highlight the need for developing additional diagnostic markers, maybe based upon the host inflammatory response, to delineate which of these detections are pathogens and which are passengers,” Dr. Thakker said.

She reported having no relevant financial conflicts regarding the European Union–sponsored study.

MADRID – Whole blood multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) holds considerable promise as a rapid noninvasive test to improve diagnosis of life-threatening bacterial infections in children with suspected sepsis yet negative blood cultures, Clare Thakker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

There are several disadvantages with blood cultures – the current diagnostic standard. The turnaround time is 48 hours or longer. Moreover, false-negative culture results are common because of prior antibiotic therapy. And blood cultures require a considerable amount of blood, which becomes an issue in younger children with small blood volumes. Whole blood PCR is unfettered by these limitations, and it could reduce the need for invasive sampling, such as pleural or joint aspiration or CSF sampling, in blood culture–negative children, observed Dr. Thakker of Imperial College London.

The challenge posed by febrile children is that even though the vast majority will turn out to have a self-limited viral illness, a small proportion will have a life-threatening bacterial infection. And distinguishing between the two groups in timely fashion often remains difficult today, the pediatrician said.

Dr. Thakker reported on 504 EUCLIDS participants with suspected sepsis who had blood cultures and whole blood PCR testing done on the same day. The multiplex PCR, developed by Micropathology of Coventry, England, was set up to test simultaneously for five clinically important bacterial pathogens: Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae. Prior to testing, the blood samples underwent lysozyme/lysostaphin digestion and silica bead disruption in order to break down cell walls and facilitate nucleic acid extraction.

Of the 504 children with suspected sepsis, 438 (87%) had negative blood cultures, among whom were 326 patients (74%) with clinically suspected or definite bacterial infection. The PCR test identified one of the five target pathogens in 25 of the 326 patients (8%) where physicians suspected bacterial sepsis despite negative cultures. Ten blood culture-negative patients (40%) were whole blood PCR positive for N. meningitidis, 6 (24%) for H. influenzae, 5 (20%) for S. pneumoniae, 3 (12%) for S. aureus, and 1 (4%) for S. pyogenes. Three of the 25 positive tests showed poor clinical correlation consistent with environmental contamination. The other 22 positive PCR results were consistent with the patient’s clinical syndrome – for example, N. meningitidis being found in the blood of a child with meningeal encephalitis – or concordant with the results of a culture obtained invasively at a sterile body site.

Ninety-two patients with negative blood cultures were culture positive for a causative bacterial pathogen obtained by invasive sampling of a sterile body site such as the CSF. In 68 of these 92 cases (74%), the pathogen was among those on the multiplex PCR panel.

“Our study results bring into question whether blood culture should be the gold standard; clearly, blood culture is not capturing everything. Our findings also highlight the need for developing additional diagnostic markers, maybe based upon the host inflammatory response, to delineate which of these detections are pathogens and which are passengers,” Dr. Thakker said.

She reported having no relevant financial conflicts regarding the European Union–sponsored study.

MADRID – Whole blood multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) holds considerable promise as a rapid noninvasive test to improve diagnosis of life-threatening bacterial infections in children with suspected sepsis yet negative blood cultures, Clare Thakker, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the European Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases.

There are several disadvantages with blood cultures – the current diagnostic standard. The turnaround time is 48 hours or longer. Moreover, false-negative culture results are common because of prior antibiotic therapy. And blood cultures require a considerable amount of blood, which becomes an issue in younger children with small blood volumes. Whole blood PCR is unfettered by these limitations, and it could reduce the need for invasive sampling, such as pleural or joint aspiration or CSF sampling, in blood culture–negative children, observed Dr. Thakker of Imperial College London.

The challenge posed by febrile children is that even though the vast majority will turn out to have a self-limited viral illness, a small proportion will have a life-threatening bacterial infection. And distinguishing between the two groups in timely fashion often remains difficult today, the pediatrician said.

Dr. Thakker reported on 504 EUCLIDS participants with suspected sepsis who had blood cultures and whole blood PCR testing done on the same day. The multiplex PCR, developed by Micropathology of Coventry, England, was set up to test simultaneously for five clinically important bacterial pathogens: Neisseria meningitidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus, and Haemophilus influenzae. Prior to testing, the blood samples underwent lysozyme/lysostaphin digestion and silica bead disruption in order to break down cell walls and facilitate nucleic acid extraction.

Of the 504 children with suspected sepsis, 438 (87%) had negative blood cultures, among whom were 326 patients (74%) with clinically suspected or definite bacterial infection. The PCR test identified one of the five target pathogens in 25 of the 326 patients (8%) where physicians suspected bacterial sepsis despite negative cultures. Ten blood culture-negative patients (40%) were whole blood PCR positive for N. meningitidis, 6 (24%) for H. influenzae, 5 (20%) for S. pneumoniae, 3 (12%) for S. aureus, and 1 (4%) for S. pyogenes. Three of the 25 positive tests showed poor clinical correlation consistent with environmental contamination. The other 22 positive PCR results were consistent with the patient’s clinical syndrome – for example, N. meningitidis being found in the blood of a child with meningeal encephalitis – or concordant with the results of a culture obtained invasively at a sterile body site.

Ninety-two patients with negative blood cultures were culture positive for a causative bacterial pathogen obtained by invasive sampling of a sterile body site such as the CSF. In 68 of these 92 cases (74%), the pathogen was among those on the multiplex PCR panel.

“Our study results bring into question whether blood culture should be the gold standard; clearly, blood culture is not capturing everything. Our findings also highlight the need for developing additional diagnostic markers, maybe based upon the host inflammatory response, to delineate which of these detections are pathogens and which are passengers,” Dr. Thakker said.

She reported having no relevant financial conflicts regarding the European Union–sponsored study.

AT ESPID 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Twenty-five of 326 children (8%) clinically suspected of having bacterial sepsis despite negative blood cultures proved positive for one of five important bacterial pathogens upon whole blood multiplex PCR testing .

Data source: EUCLIDS, a large, ongoing, 5-year international genomic study aimed at learning why some children with a bacterial infection develop serious illness while others do not.

Disclosures: The European Union sponsored the study. Dr. Thakker reported having no relevant financial conflicts.

Identifying type 1 diabetes drivers at risk of mishaps

A risk assessment score could help identify individuals with type 1 diabetes who are at higher risk of driving mishaps and who may benefit from interventions to reduce their risk, a new study suggests.

Writing in the June edition of Diabetes Care, Daniel J. Cox, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his coauthors reported on their efforts to develop and validate a “Risk Assessment of Diabetic Drivers” (RADD) scoring system.

In the first part of the two-part study, 1,371 drivers with type 1 diabetes filled out a series of questionnaires about diabetes and driving, then recorded their driving mishaps over the subsequent year (Diabetes Care. 2017;40:742-50).

This revealed that annual driving distance, peripheral neuropathy, number of past hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, and the degree to which the individual is bothered by hypoglycemia in general were all significantly associated with a risk of future driving incidents.

Based on this, the authors developed a scoring system using these factors and identified the optimum cut-off point for maximum sensitivity and specificity.

“The area under the curve, a global measure of model performance, was estimated to be 0.73, indicating that the model performed better than chance at classifying participants into the two risk categories,” the authors wrote.

When applied to the original participants, the model classified 37.5% of them as being high-risk. This group had an average of 3.03 driving mishaps over the 12-month follow-up, compared with 0.87 mishaps in the participants who fell into the lowest 37.5% of risk (P = .002).

In the second part of the study, 1,737 drivers with type 1 diabetes completed a version of the scoring questionnaire online, and 118 low-risk and 372 high-risk individuals were recruited.

The high-risk individuals were randomized either to a 2-month online intervention that aimed at helping people with type 1 diabetes anticipate, prevent, detect, and treat hypoglycemia while driving, as well as a program of motivational interviewing, the online intervention alone, or routine care, with 12 months of follow-up. The low-risk individuals all received routine care only.

As with the first part of the study, researchers saw a significantly lower number of driving mishaps in the low-risk participants, compared with the high-risk participants (1.65 mishaps per driver per year vs. 4.26 mishaps per driver per year; P less than .001).

After adjusting for other factors such as age, sex, method of insulin delivery, and hypoglycemia awareness, the rate of mishaps was still 2.83 times higher in the high-risk group, compared with the low-risk group (P less than .001).

The authors noted that their RADD scoring system did have a false-negative rate of 24%, classifying people as low-risk even though they reported more than one driving mishap in the following 12 months.

“This illustrates that any driver has a risk of being involved in a collision or receiving a citation, and any driver with type 1 diabetes has the additional risk of experiencing disruptive extreme [blood glucose (BG)] that can result in a mishap while driving,” they wrote. “While, ideally, all drivers with type 1 diabetes should measure their BG before driving, they should at least be counseled that, whenever they take more insulin, eat fewer carbohydrates, or engage in more physical activity than usual, they should measure their BG before driving.”

With respect to the impact of the intervention and motivational interviewing, researchers found no significant differences in the rate of mishaps between the groups who received intervention plus interview and those who received the intervention alone, and, as a result, combined these two groups into one.

The high-risk group who underwent the online intervention had fewer driving mishaps than did the high-risk group who received routine care. However, they still had 1.58 times more incidents than did the low-risk individuals who received routine care.

The intervention decreased the risk of mishaps associated with hypoglycemia in high-risk individuals, compared with that in those who recieved routine care, but these individuals still had a higher incidence of hypoglycemia-associated mishaps, compared with the low-risk individuals.

“It is also important to note that [the online intervention] only affected hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, not hyperglycemia- or nondiabetes-related mishaps,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and supported in-kind by LifeScan, Abbott Laboratories, MyGlu.com, dLife.com, and Dex4.com.

A risk assessment score could help identify individuals with type 1 diabetes who are at higher risk of driving mishaps and who may benefit from interventions to reduce their risk, a new study suggests.

Writing in the June edition of Diabetes Care, Daniel J. Cox, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his coauthors reported on their efforts to develop and validate a “Risk Assessment of Diabetic Drivers” (RADD) scoring system.

In the first part of the two-part study, 1,371 drivers with type 1 diabetes filled out a series of questionnaires about diabetes and driving, then recorded their driving mishaps over the subsequent year (Diabetes Care. 2017;40:742-50).

This revealed that annual driving distance, peripheral neuropathy, number of past hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, and the degree to which the individual is bothered by hypoglycemia in general were all significantly associated with a risk of future driving incidents.

Based on this, the authors developed a scoring system using these factors and identified the optimum cut-off point for maximum sensitivity and specificity.

“The area under the curve, a global measure of model performance, was estimated to be 0.73, indicating that the model performed better than chance at classifying participants into the two risk categories,” the authors wrote.

When applied to the original participants, the model classified 37.5% of them as being high-risk. This group had an average of 3.03 driving mishaps over the 12-month follow-up, compared with 0.87 mishaps in the participants who fell into the lowest 37.5% of risk (P = .002).

In the second part of the study, 1,737 drivers with type 1 diabetes completed a version of the scoring questionnaire online, and 118 low-risk and 372 high-risk individuals were recruited.

The high-risk individuals were randomized either to a 2-month online intervention that aimed at helping people with type 1 diabetes anticipate, prevent, detect, and treat hypoglycemia while driving, as well as a program of motivational interviewing, the online intervention alone, or routine care, with 12 months of follow-up. The low-risk individuals all received routine care only.

As with the first part of the study, researchers saw a significantly lower number of driving mishaps in the low-risk participants, compared with the high-risk participants (1.65 mishaps per driver per year vs. 4.26 mishaps per driver per year; P less than .001).

After adjusting for other factors such as age, sex, method of insulin delivery, and hypoglycemia awareness, the rate of mishaps was still 2.83 times higher in the high-risk group, compared with the low-risk group (P less than .001).

The authors noted that their RADD scoring system did have a false-negative rate of 24%, classifying people as low-risk even though they reported more than one driving mishap in the following 12 months.

“This illustrates that any driver has a risk of being involved in a collision or receiving a citation, and any driver with type 1 diabetes has the additional risk of experiencing disruptive extreme [blood glucose (BG)] that can result in a mishap while driving,” they wrote. “While, ideally, all drivers with type 1 diabetes should measure their BG before driving, they should at least be counseled that, whenever they take more insulin, eat fewer carbohydrates, or engage in more physical activity than usual, they should measure their BG before driving.”

With respect to the impact of the intervention and motivational interviewing, researchers found no significant differences in the rate of mishaps between the groups who received intervention plus interview and those who received the intervention alone, and, as a result, combined these two groups into one.

The high-risk group who underwent the online intervention had fewer driving mishaps than did the high-risk group who received routine care. However, they still had 1.58 times more incidents than did the low-risk individuals who received routine care.

The intervention decreased the risk of mishaps associated with hypoglycemia in high-risk individuals, compared with that in those who recieved routine care, but these individuals still had a higher incidence of hypoglycemia-associated mishaps, compared with the low-risk individuals.

“It is also important to note that [the online intervention] only affected hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, not hyperglycemia- or nondiabetes-related mishaps,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and supported in-kind by LifeScan, Abbott Laboratories, MyGlu.com, dLife.com, and Dex4.com.

A risk assessment score could help identify individuals with type 1 diabetes who are at higher risk of driving mishaps and who may benefit from interventions to reduce their risk, a new study suggests.

Writing in the June edition of Diabetes Care, Daniel J. Cox, MD, of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, and his coauthors reported on their efforts to develop and validate a “Risk Assessment of Diabetic Drivers” (RADD) scoring system.

In the first part of the two-part study, 1,371 drivers with type 1 diabetes filled out a series of questionnaires about diabetes and driving, then recorded their driving mishaps over the subsequent year (Diabetes Care. 2017;40:742-50).

This revealed that annual driving distance, peripheral neuropathy, number of past hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, and the degree to which the individual is bothered by hypoglycemia in general were all significantly associated with a risk of future driving incidents.

Based on this, the authors developed a scoring system using these factors and identified the optimum cut-off point for maximum sensitivity and specificity.

“The area under the curve, a global measure of model performance, was estimated to be 0.73, indicating that the model performed better than chance at classifying participants into the two risk categories,” the authors wrote.

When applied to the original participants, the model classified 37.5% of them as being high-risk. This group had an average of 3.03 driving mishaps over the 12-month follow-up, compared with 0.87 mishaps in the participants who fell into the lowest 37.5% of risk (P = .002).

In the second part of the study, 1,737 drivers with type 1 diabetes completed a version of the scoring questionnaire online, and 118 low-risk and 372 high-risk individuals were recruited.

The high-risk individuals were randomized either to a 2-month online intervention that aimed at helping people with type 1 diabetes anticipate, prevent, detect, and treat hypoglycemia while driving, as well as a program of motivational interviewing, the online intervention alone, or routine care, with 12 months of follow-up. The low-risk individuals all received routine care only.

As with the first part of the study, researchers saw a significantly lower number of driving mishaps in the low-risk participants, compared with the high-risk participants (1.65 mishaps per driver per year vs. 4.26 mishaps per driver per year; P less than .001).

After adjusting for other factors such as age, sex, method of insulin delivery, and hypoglycemia awareness, the rate of mishaps was still 2.83 times higher in the high-risk group, compared with the low-risk group (P less than .001).

The authors noted that their RADD scoring system did have a false-negative rate of 24%, classifying people as low-risk even though they reported more than one driving mishap in the following 12 months.

“This illustrates that any driver has a risk of being involved in a collision or receiving a citation, and any driver with type 1 diabetes has the additional risk of experiencing disruptive extreme [blood glucose (BG)] that can result in a mishap while driving,” they wrote. “While, ideally, all drivers with type 1 diabetes should measure their BG before driving, they should at least be counseled that, whenever they take more insulin, eat fewer carbohydrates, or engage in more physical activity than usual, they should measure their BG before driving.”

With respect to the impact of the intervention and motivational interviewing, researchers found no significant differences in the rate of mishaps between the groups who received intervention plus interview and those who received the intervention alone, and, as a result, combined these two groups into one.

The high-risk group who underwent the online intervention had fewer driving mishaps than did the high-risk group who received routine care. However, they still had 1.58 times more incidents than did the low-risk individuals who received routine care.

The intervention decreased the risk of mishaps associated with hypoglycemia in high-risk individuals, compared with that in those who recieved routine care, but these individuals still had a higher incidence of hypoglycemia-associated mishaps, compared with the low-risk individuals.

“It is also important to note that [the online intervention] only affected hypoglycemia-related driving mishaps, not hyperglycemia- or nondiabetes-related mishaps,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and supported in-kind by LifeScan, Abbott Laboratories, MyGlu.com, dLife.com, and Dex4.com.

FROM DIABETES CARE

Key clinical point: A scoring questionnaire could help identify drivers with type 1 diabetes at greater risk of driving mishaps and those who could benefit from an intervention to reduce their risk.

Major finding: Individuals with type 1 diabetes who were classified as high-risk according to a scoring system had a more than threefold greater incidence of driving mishaps than those classified as low-risk.

Data source: A two-part study in 1,371 and 1,737 drivers with type 1 diabetes.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and supported in-kind by LifeScan, Abbott Laboratories, MyGlu.com, dLife.com, and Dex4.com.

Earlier childhood measles vaccination elevates the risk of vaccine failure

of age or younger, compared with 15 months of age or older, said Sara Carazo Perez, MD, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and her associates.

Studies suggest that measles elimination “requires the maintenance of population immunity above 92%-94%.” So, “the additional protection of 3%-5% of vaccinated children against secondary vaccine failures by postponing the first dose from 12 to 15 months of age would be significant, and the risk would be minimal in countries that achieved elimination” of measles, said Dr. Perez and her colleagues.

The percentage of children who were seronegative for measles after being vaccinated decreased significantly with older age at the first dose, from 8.5% in children vaccinated at 11 months to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 1.5% with vaccination at 12 months, 13-14 months, and 15-22 months, respectively (P less than .001).

Geometric mean concentrations (GMC) after the second dose were highly correlated with GMCs after the first dose.

The investigators then performed multivariable analysis, adjusting for the type of vaccine, the country, and the study. GMCs rose significantly with older age at first dose. Children vaccinated at 11 months had a 23% lower GMC and 30% increased risk of seronegativity than children vaccinated at 12 months.

In children first vaccinated at 13-14 months or 15-22 months, GMCs were 1.21 and 1.37 times greater than in children vaccinated at 12 months, respectively, and their risks for seronegativity were 49% and 71% lower, respectively.

“After two doses, the association between the age at first dose and the GMC was slightly weaker but still significant,” the researchers said.

Read more in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Jun 8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix510).

of age or younger, compared with 15 months of age or older, said Sara Carazo Perez, MD, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and her associates.

Studies suggest that measles elimination “requires the maintenance of population immunity above 92%-94%.” So, “the additional protection of 3%-5% of vaccinated children against secondary vaccine failures by postponing the first dose from 12 to 15 months of age would be significant, and the risk would be minimal in countries that achieved elimination” of measles, said Dr. Perez and her colleagues.

The percentage of children who were seronegative for measles after being vaccinated decreased significantly with older age at the first dose, from 8.5% in children vaccinated at 11 months to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 1.5% with vaccination at 12 months, 13-14 months, and 15-22 months, respectively (P less than .001).

Geometric mean concentrations (GMC) after the second dose were highly correlated with GMCs after the first dose.

The investigators then performed multivariable analysis, adjusting for the type of vaccine, the country, and the study. GMCs rose significantly with older age at first dose. Children vaccinated at 11 months had a 23% lower GMC and 30% increased risk of seronegativity than children vaccinated at 12 months.

In children first vaccinated at 13-14 months or 15-22 months, GMCs were 1.21 and 1.37 times greater than in children vaccinated at 12 months, respectively, and their risks for seronegativity were 49% and 71% lower, respectively.

“After two doses, the association between the age at first dose and the GMC was slightly weaker but still significant,” the researchers said.

Read more in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Jun 8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix510).

of age or younger, compared with 15 months of age or older, said Sara Carazo Perez, MD, PhD, of Laval University, Quebec City, and her associates.

Studies suggest that measles elimination “requires the maintenance of population immunity above 92%-94%.” So, “the additional protection of 3%-5% of vaccinated children against secondary vaccine failures by postponing the first dose from 12 to 15 months of age would be significant, and the risk would be minimal in countries that achieved elimination” of measles, said Dr. Perez and her colleagues.

The percentage of children who were seronegative for measles after being vaccinated decreased significantly with older age at the first dose, from 8.5% in children vaccinated at 11 months to 3.2%, 2.4%, and 1.5% with vaccination at 12 months, 13-14 months, and 15-22 months, respectively (P less than .001).

Geometric mean concentrations (GMC) after the second dose were highly correlated with GMCs after the first dose.

The investigators then performed multivariable analysis, adjusting for the type of vaccine, the country, and the study. GMCs rose significantly with older age at first dose. Children vaccinated at 11 months had a 23% lower GMC and 30% increased risk of seronegativity than children vaccinated at 12 months.

In children first vaccinated at 13-14 months or 15-22 months, GMCs were 1.21 and 1.37 times greater than in children vaccinated at 12 months, respectively, and their risks for seronegativity were 49% and 71% lower, respectively.

“After two doses, the association between the age at first dose and the GMC was slightly weaker but still significant,” the researchers said.

Read more in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Jun 8. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix510).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

See one, do one ...

It rolls off your tongue so easily. See-one, do-one, teach-one has been the mantra recited to doctors-in-training for hundreds of years. It purports to characterize the process by which technical skills are passed from one generation of physicians to the next. However, you know as well as I do that the process of learning a skill such as performing a lumbar puncture on a squirming 6-month-old almost never conforms to the see-one, do-one, teach-one dictum.

Although I recall that it was not until my 7th birthday that I could consistently and confidently tie my own shoes, I consider myself reasonably dexterous. As a woodcarver, I was comfortable around sharp instruments, but that comfort zone quickly disappeared when it came to poking and cutting another human being who had nerves and blood vessels.

In a Pediatric Perspective in the June 2017 issue of Pediatrics, two anesthesiologists at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia address that question of, How many tries is reasonable for a physician attempting to learn a new technique (“When Should Trainees Call for Help with Invasive Procedures?” Pediatrics. 2017, June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3673)? They illustrate their insightful discussion with the gruesome image of the wrist of an infant who had endured 21 attempts at percutaneous arterial line placement.

In addition to direct supervision, the authors recommend that instructors engage the trainee in a preprocedure discussion that includes setting a predetermined number of unsuccessful attempts at which the trainee will stop and ask for help. They suggest that the “trainee should be taught the self-insight to summon a more experienced provider or perhaps just a fresh pair of hands.”

For the general pediatrician or family physician, many of the technical skills we learned in training are likely to fade from disuse in the real world of office practice. However, learning when and how to step back in the face of multiple failures is a skill that every physician will continue to use regardless of where he or she is on his or her professional trajectory.

It isn’t always easy. It challenges our egos to ask for help when we have failed at making the diagnosis or not chosen the most effective therapy. At a minimum, stepping back and taking a deep breath (or three) may allow us a window through which we can finally see outside the box we find ourselves in.

Persistence is an attribute that allowed us to navigate the long and challenging path of our medical education. But, there are situations when it gets in the way of good medical care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

It rolls off your tongue so easily. See-one, do-one, teach-one has been the mantra recited to doctors-in-training for hundreds of years. It purports to characterize the process by which technical skills are passed from one generation of physicians to the next. However, you know as well as I do that the process of learning a skill such as performing a lumbar puncture on a squirming 6-month-old almost never conforms to the see-one, do-one, teach-one dictum.

Although I recall that it was not until my 7th birthday that I could consistently and confidently tie my own shoes, I consider myself reasonably dexterous. As a woodcarver, I was comfortable around sharp instruments, but that comfort zone quickly disappeared when it came to poking and cutting another human being who had nerves and blood vessels.

In a Pediatric Perspective in the June 2017 issue of Pediatrics, two anesthesiologists at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia address that question of, How many tries is reasonable for a physician attempting to learn a new technique (“When Should Trainees Call for Help with Invasive Procedures?” Pediatrics. 2017, June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3673)? They illustrate their insightful discussion with the gruesome image of the wrist of an infant who had endured 21 attempts at percutaneous arterial line placement.

In addition to direct supervision, the authors recommend that instructors engage the trainee in a preprocedure discussion that includes setting a predetermined number of unsuccessful attempts at which the trainee will stop and ask for help. They suggest that the “trainee should be taught the self-insight to summon a more experienced provider or perhaps just a fresh pair of hands.”

For the general pediatrician or family physician, many of the technical skills we learned in training are likely to fade from disuse in the real world of office practice. However, learning when and how to step back in the face of multiple failures is a skill that every physician will continue to use regardless of where he or she is on his or her professional trajectory.

It isn’t always easy. It challenges our egos to ask for help when we have failed at making the diagnosis or not chosen the most effective therapy. At a minimum, stepping back and taking a deep breath (or three) may allow us a window through which we can finally see outside the box we find ourselves in.

Persistence is an attribute that allowed us to navigate the long and challenging path of our medical education. But, there are situations when it gets in the way of good medical care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

It rolls off your tongue so easily. See-one, do-one, teach-one has been the mantra recited to doctors-in-training for hundreds of years. It purports to characterize the process by which technical skills are passed from one generation of physicians to the next. However, you know as well as I do that the process of learning a skill such as performing a lumbar puncture on a squirming 6-month-old almost never conforms to the see-one, do-one, teach-one dictum.

Although I recall that it was not until my 7th birthday that I could consistently and confidently tie my own shoes, I consider myself reasonably dexterous. As a woodcarver, I was comfortable around sharp instruments, but that comfort zone quickly disappeared when it came to poking and cutting another human being who had nerves and blood vessels.

In a Pediatric Perspective in the June 2017 issue of Pediatrics, two anesthesiologists at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia address that question of, How many tries is reasonable for a physician attempting to learn a new technique (“When Should Trainees Call for Help with Invasive Procedures?” Pediatrics. 2017, June. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-3673)? They illustrate their insightful discussion with the gruesome image of the wrist of an infant who had endured 21 attempts at percutaneous arterial line placement.

In addition to direct supervision, the authors recommend that instructors engage the trainee in a preprocedure discussion that includes setting a predetermined number of unsuccessful attempts at which the trainee will stop and ask for help. They suggest that the “trainee should be taught the self-insight to summon a more experienced provider or perhaps just a fresh pair of hands.”

For the general pediatrician or family physician, many of the technical skills we learned in training are likely to fade from disuse in the real world of office practice. However, learning when and how to step back in the face of multiple failures is a skill that every physician will continue to use regardless of where he or she is on his or her professional trajectory.

It isn’t always easy. It challenges our egos to ask for help when we have failed at making the diagnosis or not chosen the most effective therapy. At a minimum, stepping back and taking a deep breath (or three) may allow us a window through which we can finally see outside the box we find ourselves in.

Persistence is an attribute that allowed us to navigate the long and challenging path of our medical education. But, there are situations when it gets in the way of good medical care.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Email him at [email protected].

Use of probiotics in hospitalized adults to prevent Clostridium difficile infection

Clinical Question: Does the use and timing of probiotics in hospitalized adult patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) improve clinical outcomes?

Background: The incidence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased significantly over the past years, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Improved prevention of CDI could have substantial public health benefits.

Study design: Systematic review and metaregression analysis.

Setting: 19 studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating probiotic effects on CDI in hospitalized adults taking antibiotics.

Comprising 6261 subjects, 19 RCTs were analyzed. The incidence of CDI was lower in the probiotic cohort than in the control group (1.6% vs. 3.9%; P less than 0.001). The pooled relative risk of CDI in probiotic users was 0.42 (95% CI, 0.30-0.57). Metaregression analysis demonstrated that probiotics were significantly more effective if given closer to the first antibiotic dose, with a decrease in efficacy for every day of delay in starting probiotics (P = .04). Probiotics given within 2 days of antibiotic initiation produced a greater reduction of risk for CDI (RR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48) than later administration (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40-1.23; P = .02). There was no increased risk for adverse events among patients receiving probiotics.

Limitations included high risk of bias because of missing data, attrition, restricted patient population, lack of placebo, and conflict of interest.

Bottom Line: Administration of probiotics soon after the first dose of antibiotic reduces the risk of CDI by more than 50% in hospitalized adults without any increased risk of adverse events.

Reference: Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL et al. Timely use of Probiotics in Hospitalized Adults Prevents Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review with Meta-Regression Analysis. Gastroenterology. Published on 9 Feb 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: Does the use and timing of probiotics in hospitalized adult patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) improve clinical outcomes?

Background: The incidence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased significantly over the past years, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Improved prevention of CDI could have substantial public health benefits.

Study design: Systematic review and metaregression analysis.

Setting: 19 studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating probiotic effects on CDI in hospitalized adults taking antibiotics.

Comprising 6261 subjects, 19 RCTs were analyzed. The incidence of CDI was lower in the probiotic cohort than in the control group (1.6% vs. 3.9%; P less than 0.001). The pooled relative risk of CDI in probiotic users was 0.42 (95% CI, 0.30-0.57). Metaregression analysis demonstrated that probiotics were significantly more effective if given closer to the first antibiotic dose, with a decrease in efficacy for every day of delay in starting probiotics (P = .04). Probiotics given within 2 days of antibiotic initiation produced a greater reduction of risk for CDI (RR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48) than later administration (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40-1.23; P = .02). There was no increased risk for adverse events among patients receiving probiotics.

Limitations included high risk of bias because of missing data, attrition, restricted patient population, lack of placebo, and conflict of interest.

Bottom Line: Administration of probiotics soon after the first dose of antibiotic reduces the risk of CDI by more than 50% in hospitalized adults without any increased risk of adverse events.

Reference: Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL et al. Timely use of Probiotics in Hospitalized Adults Prevents Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review with Meta-Regression Analysis. Gastroenterology. Published on 9 Feb 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: Does the use and timing of probiotics in hospitalized adult patients with Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) improve clinical outcomes?

Background: The incidence of CDI in hospitalized patients has increased significantly over the past years, resulting in significant morbidity and mortality. Improved prevention of CDI could have substantial public health benefits.

Study design: Systematic review and metaregression analysis.

Setting: 19 studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating probiotic effects on CDI in hospitalized adults taking antibiotics.

Comprising 6261 subjects, 19 RCTs were analyzed. The incidence of CDI was lower in the probiotic cohort than in the control group (1.6% vs. 3.9%; P less than 0.001). The pooled relative risk of CDI in probiotic users was 0.42 (95% CI, 0.30-0.57). Metaregression analysis demonstrated that probiotics were significantly more effective if given closer to the first antibiotic dose, with a decrease in efficacy for every day of delay in starting probiotics (P = .04). Probiotics given within 2 days of antibiotic initiation produced a greater reduction of risk for CDI (RR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48) than later administration (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40-1.23; P = .02). There was no increased risk for adverse events among patients receiving probiotics.

Limitations included high risk of bias because of missing data, attrition, restricted patient population, lack of placebo, and conflict of interest.

Bottom Line: Administration of probiotics soon after the first dose of antibiotic reduces the risk of CDI by more than 50% in hospitalized adults without any increased risk of adverse events.

Reference: Shen NT, Maw A, Tmanova LL et al. Timely use of Probiotics in Hospitalized Adults Prevents Clostridium difficile Infection: A Systematic Review with Meta-Regression Analysis. Gastroenterology. Published on 9 Feb 2017. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Sooner may not be better: Study shows no benefit of urgent colonoscopy for lower GI bleeding

Clinical Question: In patients hospitalized for a lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), does an urgent colonoscopy (less than 24 hours after admission) result in any clinical benefits, compared with waiting for an elective colonoscopy?

Background: LGIB is a common cause of morbidity and mortality, often requiring hospitalization. While colonoscopy is necessary for appropriate work-up and treatment, it remains unclear if time to colonoscopy (urgent vs. elective) confers any clinical benefit in hospitalized patients.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twelve studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for appropriate studies, and 12 met inclusion criteria, resulting in a total sample size of 10,172 patients in the urgent colonoscopy arm and 14,224 patients in the elective colonoscopy.

Outcome measures included bleeding source identified on colonoscopy, therapeutic endoscopic interventions performed, patients requiring blood transfusions, rebleeding, adverse events, and mortality.

Urgent colonoscopy was associated with increased use of endoscopic therapeutic intervention (relative risk, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.08-2.67). There were no significant differences in bleeding source localization (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.92-1.25), adverse event rates (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.65-1.71), rebleeding rates (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.74-1.78), transfusion requirement (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.73-1.41), or mortality (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.45-3.02) between urgent and elective colonoscopy.

Limitations of the study comprise of inclusion of small number of studies, underpowered statistical analysis, and possible variation in quality assessment of articles evaluated.

Bottom Line: Urgent colonoscopy is safe and usually well tolerated in hospitalized patients with LGIB, but, compared with elective colonoscopy, there is no clear evidence it alters important clinical outcomes.

Reference: Kouanda AM, Somsouk M, Sewell JL, Day LW. Urgent colonoscopy in patients with lower GI bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. Published online Feb 4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.035.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: In patients hospitalized for a lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), does an urgent colonoscopy (less than 24 hours after admission) result in any clinical benefits, compared with waiting for an elective colonoscopy?

Background: LGIB is a common cause of morbidity and mortality, often requiring hospitalization. While colonoscopy is necessary for appropriate work-up and treatment, it remains unclear if time to colonoscopy (urgent vs. elective) confers any clinical benefit in hospitalized patients.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twelve studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for appropriate studies, and 12 met inclusion criteria, resulting in a total sample size of 10,172 patients in the urgent colonoscopy arm and 14,224 patients in the elective colonoscopy.

Outcome measures included bleeding source identified on colonoscopy, therapeutic endoscopic interventions performed, patients requiring blood transfusions, rebleeding, adverse events, and mortality.

Urgent colonoscopy was associated with increased use of endoscopic therapeutic intervention (relative risk, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.08-2.67). There were no significant differences in bleeding source localization (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.92-1.25), adverse event rates (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.65-1.71), rebleeding rates (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.74-1.78), transfusion requirement (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.73-1.41), or mortality (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.45-3.02) between urgent and elective colonoscopy.

Limitations of the study comprise of inclusion of small number of studies, underpowered statistical analysis, and possible variation in quality assessment of articles evaluated.

Bottom Line: Urgent colonoscopy is safe and usually well tolerated in hospitalized patients with LGIB, but, compared with elective colonoscopy, there is no clear evidence it alters important clinical outcomes.

Reference: Kouanda AM, Somsouk M, Sewell JL, Day LW. Urgent colonoscopy in patients with lower GI bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. Published online Feb 4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.035.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

Clinical Question: In patients hospitalized for a lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), does an urgent colonoscopy (less than 24 hours after admission) result in any clinical benefits, compared with waiting for an elective colonoscopy?

Background: LGIB is a common cause of morbidity and mortality, often requiring hospitalization. While colonoscopy is necessary for appropriate work-up and treatment, it remains unclear if time to colonoscopy (urgent vs. elective) confers any clinical benefit in hospitalized patients.

Study Design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twelve studies meeting inclusion criteria.

Synopsis: Computerized bibliography databases were searched for appropriate studies, and 12 met inclusion criteria, resulting in a total sample size of 10,172 patients in the urgent colonoscopy arm and 14,224 patients in the elective colonoscopy.

Outcome measures included bleeding source identified on colonoscopy, therapeutic endoscopic interventions performed, patients requiring blood transfusions, rebleeding, adverse events, and mortality.

Urgent colonoscopy was associated with increased use of endoscopic therapeutic intervention (relative risk, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.08-2.67). There were no significant differences in bleeding source localization (RR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.92-1.25), adverse event rates (RR, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.65-1.71), rebleeding rates (RR, 1.14; 95% CI, 0.74-1.78), transfusion requirement (RR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.73-1.41), or mortality (RR, 1.17; 95% CI, 0.45-3.02) between urgent and elective colonoscopy.

Limitations of the study comprise of inclusion of small number of studies, underpowered statistical analysis, and possible variation in quality assessment of articles evaluated.

Bottom Line: Urgent colonoscopy is safe and usually well tolerated in hospitalized patients with LGIB, but, compared with elective colonoscopy, there is no clear evidence it alters important clinical outcomes.

Reference: Kouanda AM, Somsouk M, Sewell JL, Day LW. Urgent colonoscopy in patients with lower GI bleeding: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. Published online Feb 4, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.035.

Dr. Martin is clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine, department of medicine, University of California, San Diego.

CANVAS: Canagliflozin cuts cardiovascular events, doubles risk of amputations

SAN DIEGO –

After an average of 188 weeks of follow-up, the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke was 26.9 events per 1,000 person-years of canagliflozin treatment and 31.5 events per 1,000 person-years of placebo treatment (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.97; P less than .001 for noninferiority; P = .02 for superiority) in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) and its sister trial, CANVAS-R, investigators reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The report was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925).

But unexpectedly, canagliflozin also doubled the risk of amputations, said Dr. Neal, who is with the University of New South Wales and the George Institute for Global Health in Sydney. Treating 1,000 patients for 5 years would lead to 15 excess amputations, including 10 amputations of the toes or forefoot and five amputations at the ankle or above, he said.

The reason for this heightened risk is unknown. Other sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) development programs did not comprehensively monitor amputations, so it is unclear whether this is a class effect, Dr. Neal said. For now, the Food and Drug Administration is requiring a boxed warning for canagliflozin, while its European Union product label recommends carefully monitoring patients, emphasizing foot care and hydration, and considering stopping treatment if patients develop lower-extremity ulcers, infection, osteomyelitis, or gangrene.

Canagliflozin might also increase the risk of fractures, Dr. Bruce and his coinvestigators noted. Hazard ratios for overall and low-trauma fractures reached statistical significance in CANVAS, but not in CANVAS-R. As in other trials of SGLT-2 inhibitors, canagliflozin significantly increased the risk of female and male genital mycotic infections (respective HR, 4.27 and 3.76) and was associated with osmotic diuresis (HR, 2.80), and volume depletion (HR, 1.44). However, canagliflozin was not associated with malignancies, hepatic injury, pancreatitis, diabetic ketoacidosis, photosensitivity, hypersensitivity reactions, hypoglycemia, venous thrombotic events, or urinary tract infections.

Canagliflozin (Invokana, Janssen) inhibits SGLT-2, which is responsible for about 90% of renal glucose reabsorption. The FDA approved the medication in 2013 based on interim results from the CANVAS trial, which included 4,330 adults with type 2 diabetes and a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Patients were usually in their 60s, male, and hypertensive. Two-thirds had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and about 14% had heart failure. Background medications included metformin, insulin, sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and cardioprotective agents. Patients were randomly assigned to receive canagliflozin 300 mg or 100 mg or placebo.

Investigators designed the CANVAS-R trial to further evaluate canagliflozin in another 5,813 patients with type 2 diabetes. The SGLT-2 inhibitor met its primary MACE endpoint in the overall pooled analysis and in numerous demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Neal said. Canagliflozin also significantly cut the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.67), and met a “hard” composite endpoint of renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a 40% reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (HR, 0.60).

Compared with placebo, treatment induced regression of albuminuria and reduced loss of renal function, said coinvestigator Dick de Zeeuw, MD, PhD, of the University of Groningen (the Netherlands). “These data suggest a potential renoprotective effect of canagliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk, on top of treatment with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers,” he said.

However, patients were twice as likely to undergo amputations on canagliflozin, compared with those on placebo (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.41-2.75). Risks were similar for amputation of the toe or forefoot, at the ankle, below the knee, and above the knee, Dr. Neal said. Predictors of amputation also were similar in all arms of the trials, and included peripheral vascular disease, male sex, neuropathy, and hemoglobin A1c above 8%. Amputation was not associated with non-loop diuretic therapy, smoking, hypertension, or age.

Janssen Research and Development makes canagliflozin and sponsored the trials. Dr. Neal and Dr. Zeeuw disclosed consultancy, travel support, or grants from Janssen paid to their institutions, and ties to several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO –

After an average of 188 weeks of follow-up, the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke was 26.9 events per 1,000 person-years of canagliflozin treatment and 31.5 events per 1,000 person-years of placebo treatment (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.97; P less than .001 for noninferiority; P = .02 for superiority) in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) and its sister trial, CANVAS-R, investigators reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The report was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925).

But unexpectedly, canagliflozin also doubled the risk of amputations, said Dr. Neal, who is with the University of New South Wales and the George Institute for Global Health in Sydney. Treating 1,000 patients for 5 years would lead to 15 excess amputations, including 10 amputations of the toes or forefoot and five amputations at the ankle or above, he said.

The reason for this heightened risk is unknown. Other sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) development programs did not comprehensively monitor amputations, so it is unclear whether this is a class effect, Dr. Neal said. For now, the Food and Drug Administration is requiring a boxed warning for canagliflozin, while its European Union product label recommends carefully monitoring patients, emphasizing foot care and hydration, and considering stopping treatment if patients develop lower-extremity ulcers, infection, osteomyelitis, or gangrene.

Canagliflozin might also increase the risk of fractures, Dr. Bruce and his coinvestigators noted. Hazard ratios for overall and low-trauma fractures reached statistical significance in CANVAS, but not in CANVAS-R. As in other trials of SGLT-2 inhibitors, canagliflozin significantly increased the risk of female and male genital mycotic infections (respective HR, 4.27 and 3.76) and was associated with osmotic diuresis (HR, 2.80), and volume depletion (HR, 1.44). However, canagliflozin was not associated with malignancies, hepatic injury, pancreatitis, diabetic ketoacidosis, photosensitivity, hypersensitivity reactions, hypoglycemia, venous thrombotic events, or urinary tract infections.

Canagliflozin (Invokana, Janssen) inhibits SGLT-2, which is responsible for about 90% of renal glucose reabsorption. The FDA approved the medication in 2013 based on interim results from the CANVAS trial, which included 4,330 adults with type 2 diabetes and a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Patients were usually in their 60s, male, and hypertensive. Two-thirds had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and about 14% had heart failure. Background medications included metformin, insulin, sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and cardioprotective agents. Patients were randomly assigned to receive canagliflozin 300 mg or 100 mg or placebo.

Investigators designed the CANVAS-R trial to further evaluate canagliflozin in another 5,813 patients with type 2 diabetes. The SGLT-2 inhibitor met its primary MACE endpoint in the overall pooled analysis and in numerous demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Neal said. Canagliflozin also significantly cut the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.67), and met a “hard” composite endpoint of renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a 40% reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (HR, 0.60).

Compared with placebo, treatment induced regression of albuminuria and reduced loss of renal function, said coinvestigator Dick de Zeeuw, MD, PhD, of the University of Groningen (the Netherlands). “These data suggest a potential renoprotective effect of canagliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk, on top of treatment with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers,” he said.

However, patients were twice as likely to undergo amputations on canagliflozin, compared with those on placebo (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.41-2.75). Risks were similar for amputation of the toe or forefoot, at the ankle, below the knee, and above the knee, Dr. Neal said. Predictors of amputation also were similar in all arms of the trials, and included peripheral vascular disease, male sex, neuropathy, and hemoglobin A1c above 8%. Amputation was not associated with non-loop diuretic therapy, smoking, hypertension, or age.

Janssen Research and Development makes canagliflozin and sponsored the trials. Dr. Neal and Dr. Zeeuw disclosed consultancy, travel support, or grants from Janssen paid to their institutions, and ties to several other pharmaceutical companies.

SAN DIEGO –

After an average of 188 weeks of follow-up, the combined rate of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke was 26.9 events per 1,000 person-years of canagliflozin treatment and 31.5 events per 1,000 person-years of placebo treatment (hazard ratio, 0.86; 95% confidence interval, 0.75-0.97; P less than .001 for noninferiority; P = .02 for superiority) in the Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study (CANVAS) and its sister trial, CANVAS-R, investigators reported at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association. The report was published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med. 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611925).

But unexpectedly, canagliflozin also doubled the risk of amputations, said Dr. Neal, who is with the University of New South Wales and the George Institute for Global Health in Sydney. Treating 1,000 patients for 5 years would lead to 15 excess amputations, including 10 amputations of the toes or forefoot and five amputations at the ankle or above, he said.

The reason for this heightened risk is unknown. Other sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 (SGLT-2) development programs did not comprehensively monitor amputations, so it is unclear whether this is a class effect, Dr. Neal said. For now, the Food and Drug Administration is requiring a boxed warning for canagliflozin, while its European Union product label recommends carefully monitoring patients, emphasizing foot care and hydration, and considering stopping treatment if patients develop lower-extremity ulcers, infection, osteomyelitis, or gangrene.

Canagliflozin might also increase the risk of fractures, Dr. Bruce and his coinvestigators noted. Hazard ratios for overall and low-trauma fractures reached statistical significance in CANVAS, but not in CANVAS-R. As in other trials of SGLT-2 inhibitors, canagliflozin significantly increased the risk of female and male genital mycotic infections (respective HR, 4.27 and 3.76) and was associated with osmotic diuresis (HR, 2.80), and volume depletion (HR, 1.44). However, canagliflozin was not associated with malignancies, hepatic injury, pancreatitis, diabetic ketoacidosis, photosensitivity, hypersensitivity reactions, hypoglycemia, venous thrombotic events, or urinary tract infections.

Canagliflozin (Invokana, Janssen) inhibits SGLT-2, which is responsible for about 90% of renal glucose reabsorption. The FDA approved the medication in 2013 based on interim results from the CANVAS trial, which included 4,330 adults with type 2 diabetes and a history of symptomatic atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Patients were usually in their 60s, male, and hypertensive. Two-thirds had atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and about 14% had heart failure. Background medications included metformin, insulin, sulfonylurea, DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists, and cardioprotective agents. Patients were randomly assigned to receive canagliflozin 300 mg or 100 mg or placebo.

Investigators designed the CANVAS-R trial to further evaluate canagliflozin in another 5,813 patients with type 2 diabetes. The SGLT-2 inhibitor met its primary MACE endpoint in the overall pooled analysis and in numerous demographic and clinical subgroups, Dr. Neal said. Canagliflozin also significantly cut the risk of hospitalization for heart failure (HR, 0.67), and met a “hard” composite endpoint of renal death, end-stage renal disease, or a 40% reduction in estimated glomerular filtration rate (HR, 0.60).

Compared with placebo, treatment induced regression of albuminuria and reduced loss of renal function, said coinvestigator Dick de Zeeuw, MD, PhD, of the University of Groningen (the Netherlands). “These data suggest a potential renoprotective effect of canagliflozin treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes at high cardiovascular risk, on top of treatment with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers,” he said.

However, patients were twice as likely to undergo amputations on canagliflozin, compared with those on placebo (HR, 1.97; 95% CI, 1.41-2.75). Risks were similar for amputation of the toe or forefoot, at the ankle, below the knee, and above the knee, Dr. Neal said. Predictors of amputation also were similar in all arms of the trials, and included peripheral vascular disease, male sex, neuropathy, and hemoglobin A1c above 8%. Amputation was not associated with non-loop diuretic therapy, smoking, hypertension, or age.

Janssen Research and Development makes canagliflozin and sponsored the trials. Dr. Neal and Dr. Zeeuw disclosed consultancy, travel support, or grants from Janssen paid to their institutions, and ties to several other pharmaceutical companies.

AT THE ADA ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Canagliflozin significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular and renal events but doubled the risk of amputation, compared with placebo, in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Major finding: The hazard ratio for cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and nonfatal stroke was 0.86 in favor of canagliflozin (P = .02 for superiority). Patients on treatment were twice as likely to undergo amputations, compared to those on placebo (HR, 1.97).

Data source: Two international, randomized, double-blind trials of more than 10,000 adults with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Disclosures: Janssen Research and Development makes canagliflozin and sponsored the trials. Dr. Neal and Dr. Zeeuw disclosed consultancy, travel support, or grants from Janssen paid to their institutions and ties to several other pharmaceutical companies.

Recurring Yellowish Papules and Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Nevus Lipomatosus Cutaneous Superficialis

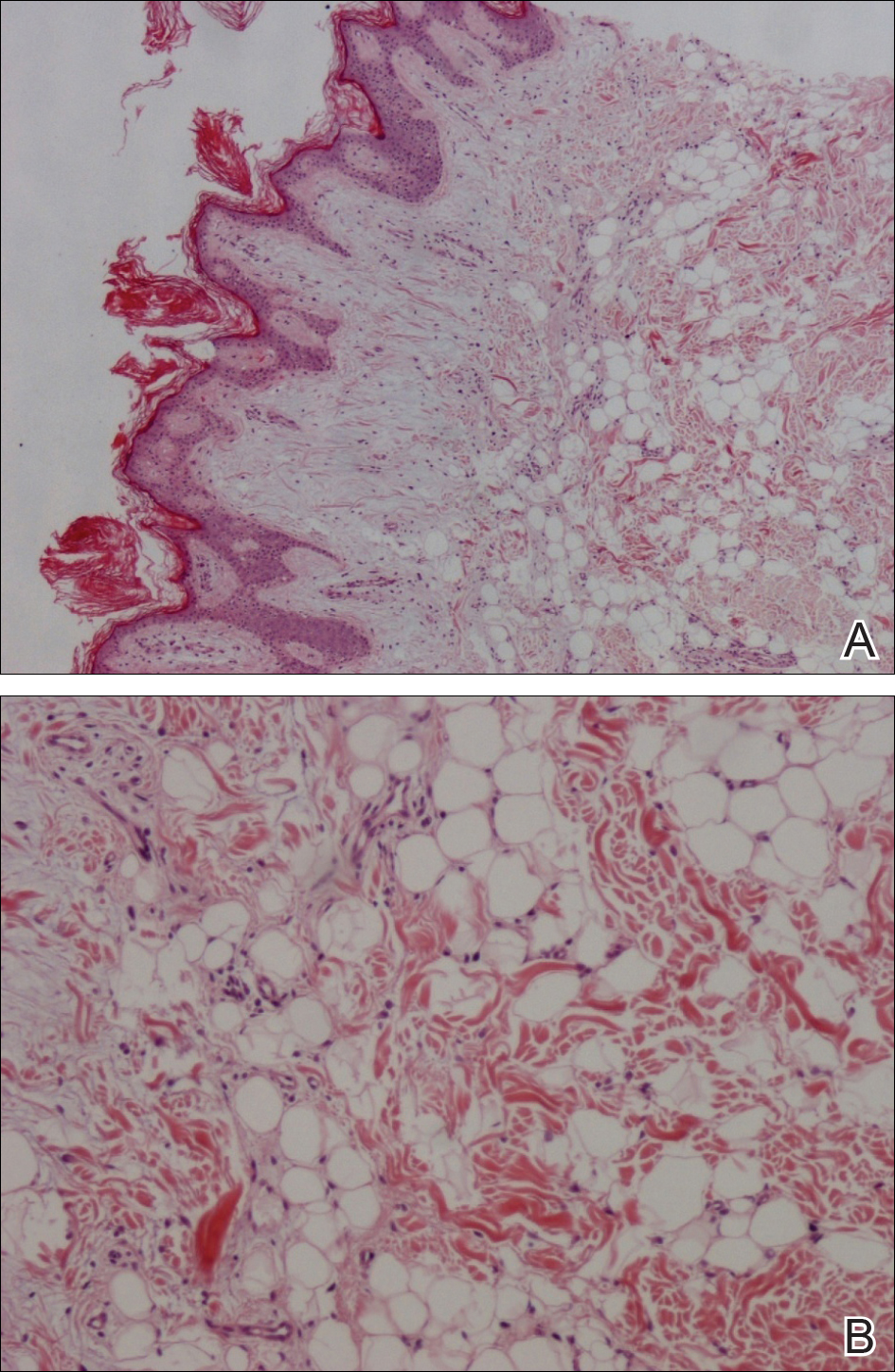

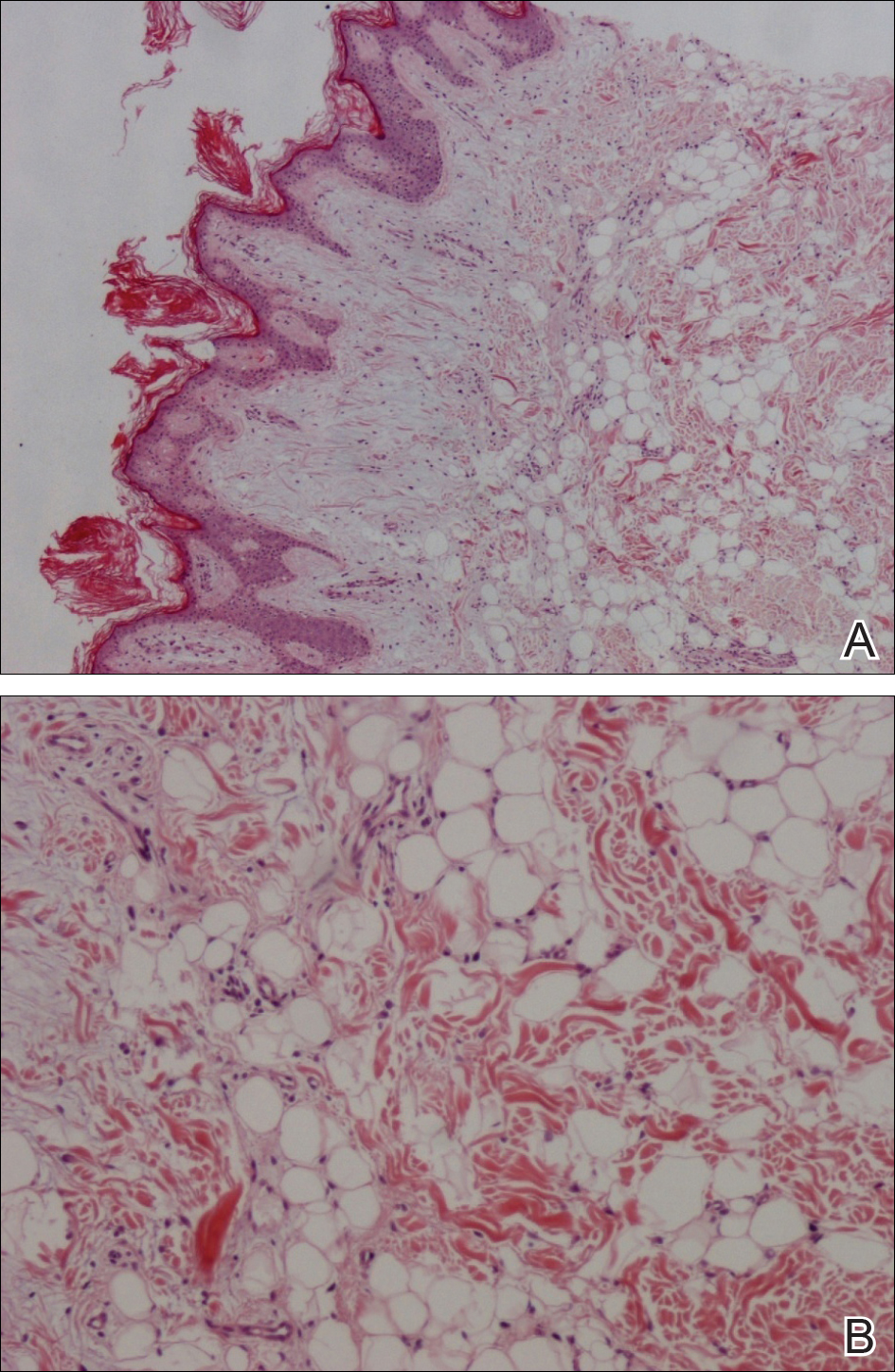

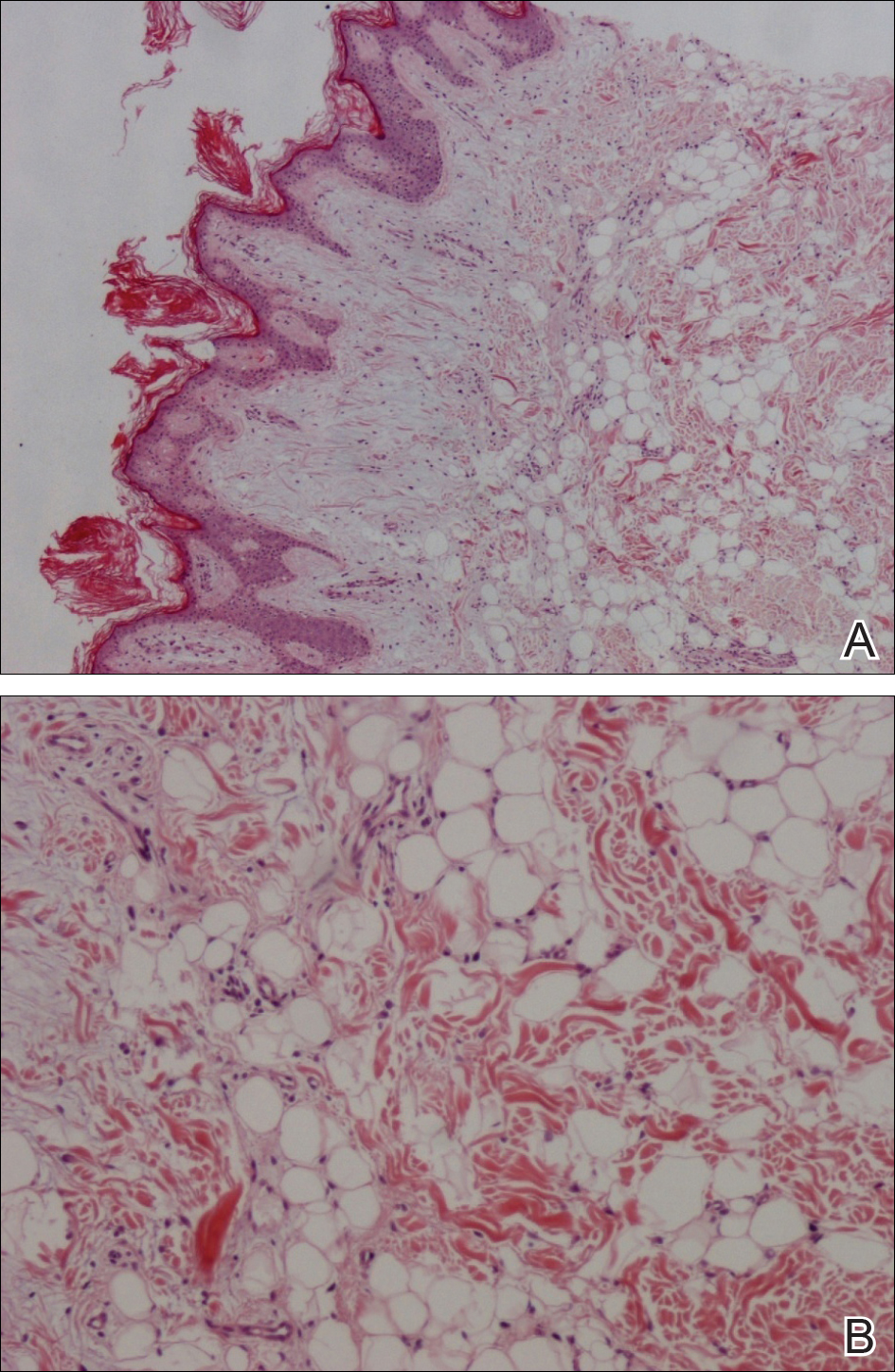

A punch biopsy was obtained from a skin lesion, which showed orthokeratosis, irregular acanthosis, papillomatosis, intense edema in the upper dermis, and mature fat lobules that dissected collagen fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure). Classical-type nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS) was diagnosed based on these clinical and histopathological findings. The patient was referred to the plastic surgery clinic for total excision of all lesions.

Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis is a rare hamartoma characterized by ectopic deposition of mature adipose tissue in the dermis.1 It was first described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle2 in 1921. Clinically, NLCS is classified into 2 subtypes: classical (multiple) and solitary. Classical-type NLCS is characterized by multiple pedunculated or sessile, soft, cerebriform, yellowish papules and nodules, especially in the pelvic area. Solitary-type NLCS presents as a sessile papule or nodule with no predilection for localization. Although the classical form of NLCS generally occurs in the first 2 decades of life, the solitary form usually appears in adulthood.3 Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis has no gender predilection and there is no genetic or congenital defect association.1,4

The pathogenesis of NLCS still is unknown, but some theories have been proposed, such as the development of adipose metaplasia secondary to degeneration of connective tissue, the formation of a true nevus resulting from heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and the development of mature adipocytes from pericytes in dermal vessels.1,5

Histopathology of NLCS shows clusters of ectopic mature adipose tissue in varying rates (10%-50%) between collagen bundles in the dermis. Characteristically, there is no connection between the ectopic mature adipose tissue and the subcutaneous adipose tissue.3 The differential diagnosis of NLCS includes neurofibroma, lymphangioma, sebaceous nevus, fibroepithelial polyps, leiomyoma, and lipomas.1,6

Treatment of NLCS generally involves basic surgical excision; however, patients treated with CO2 laser also have been reported in the literature.5 Because of the growth tendency and the large size of the classical form of NLCS, recurrence may occur, as in our case. In such cases, gradual surgical excision is recommended.5 We present this case to indicate that undesirable surgical results or relapse may occur in untreated patients because of lesion growth and delayed diagnosis.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Zéglaoui F, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis: report of eight cases. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2011;1:25-30.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Ubereinen nevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linkenglutaalgegend. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Patil SB, Narchal S, Paricharak M, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis: a rare case report. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39:304-307.

- Bancalari E, Martínez-Sánchez D, Tardío JC. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis with a folliculosebaceous component: report of 2 cases. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:105973.

- Kim YJ, Choi JH, Kim H, et al. Recurrence of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis after CO(2) laser treatment [published online November 14, 2012]. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:671-673.

- Wollina U. Photoletter to the editor - nevus lipomatosus superficialis (Hoffmann-Zurhelle). three new cases including one with ulceration and one with ipsilateral gluteal hypertrophy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:71-73.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Lipomatosus Cutaneous Superficialis

A punch biopsy was obtained from a skin lesion, which showed orthokeratosis, irregular acanthosis, papillomatosis, intense edema in the upper dermis, and mature fat lobules that dissected collagen fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure). Classical-type nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS) was diagnosed based on these clinical and histopathological findings. The patient was referred to the plastic surgery clinic for total excision of all lesions.

Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis is a rare hamartoma characterized by ectopic deposition of mature adipose tissue in the dermis.1 It was first described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle2 in 1921. Clinically, NLCS is classified into 2 subtypes: classical (multiple) and solitary. Classical-type NLCS is characterized by multiple pedunculated or sessile, soft, cerebriform, yellowish papules and nodules, especially in the pelvic area. Solitary-type NLCS presents as a sessile papule or nodule with no predilection for localization. Although the classical form of NLCS generally occurs in the first 2 decades of life, the solitary form usually appears in adulthood.3 Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis has no gender predilection and there is no genetic or congenital defect association.1,4

The pathogenesis of NLCS still is unknown, but some theories have been proposed, such as the development of adipose metaplasia secondary to degeneration of connective tissue, the formation of a true nevus resulting from heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and the development of mature adipocytes from pericytes in dermal vessels.1,5

Histopathology of NLCS shows clusters of ectopic mature adipose tissue in varying rates (10%-50%) between collagen bundles in the dermis. Characteristically, there is no connection between the ectopic mature adipose tissue and the subcutaneous adipose tissue.3 The differential diagnosis of NLCS includes neurofibroma, lymphangioma, sebaceous nevus, fibroepithelial polyps, leiomyoma, and lipomas.1,6

Treatment of NLCS generally involves basic surgical excision; however, patients treated with CO2 laser also have been reported in the literature.5 Because of the growth tendency and the large size of the classical form of NLCS, recurrence may occur, as in our case. In such cases, gradual surgical excision is recommended.5 We present this case to indicate that undesirable surgical results or relapse may occur in untreated patients because of lesion growth and delayed diagnosis.

The Diagnosis: Nevus Lipomatosus Cutaneous Superficialis

A punch biopsy was obtained from a skin lesion, which showed orthokeratosis, irregular acanthosis, papillomatosis, intense edema in the upper dermis, and mature fat lobules that dissected collagen fibers in the reticular dermis (Figure). Classical-type nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis (NLCS) was diagnosed based on these clinical and histopathological findings. The patient was referred to the plastic surgery clinic for total excision of all lesions.

Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis is a rare hamartoma characterized by ectopic deposition of mature adipose tissue in the dermis.1 It was first described by Hoffmann and Zurhelle2 in 1921. Clinically, NLCS is classified into 2 subtypes: classical (multiple) and solitary. Classical-type NLCS is characterized by multiple pedunculated or sessile, soft, cerebriform, yellowish papules and nodules, especially in the pelvic area. Solitary-type NLCS presents as a sessile papule or nodule with no predilection for localization. Although the classical form of NLCS generally occurs in the first 2 decades of life, the solitary form usually appears in adulthood.3 Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis has no gender predilection and there is no genetic or congenital defect association.1,4

The pathogenesis of NLCS still is unknown, but some theories have been proposed, such as the development of adipose metaplasia secondary to degeneration of connective tissue, the formation of a true nevus resulting from heterotopic development of adipose tissue, and the development of mature adipocytes from pericytes in dermal vessels.1,5

Histopathology of NLCS shows clusters of ectopic mature adipose tissue in varying rates (10%-50%) between collagen bundles in the dermis. Characteristically, there is no connection between the ectopic mature adipose tissue and the subcutaneous adipose tissue.3 The differential diagnosis of NLCS includes neurofibroma, lymphangioma, sebaceous nevus, fibroepithelial polyps, leiomyoma, and lipomas.1,6

Treatment of NLCS generally involves basic surgical excision; however, patients treated with CO2 laser also have been reported in the literature.5 Because of the growth tendency and the large size of the classical form of NLCS, recurrence may occur, as in our case. In such cases, gradual surgical excision is recommended.5 We present this case to indicate that undesirable surgical results or relapse may occur in untreated patients because of lesion growth and delayed diagnosis.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Zéglaoui F, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis: report of eight cases. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2011;1:25-30.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Ubereinen nevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linkenglutaalgegend. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1921;130:327-333.

- Patil SB, Narchal S, Paricharak M, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis: a rare case report. Iran J Med Sci. 2014;39:304-307.

- Bancalari E, Martínez-Sánchez D, Tardío JC. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis with a folliculosebaceous component: report of 2 cases. Patholog Res Int. 2011;2011:105973.

- Kim YJ, Choi JH, Kim H, et al. Recurrence of nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis after CO(2) laser treatment [published online November 14, 2012]. Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:671-673.

- Wollina U. Photoletter to the editor - nevus lipomatosus superficialis (Hoffmann-Zurhelle). three new cases including one with ulceration and one with ipsilateral gluteal hypertrophy. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2013;7:71-73.

- Goucha S, Khaled A, Zéglaoui F, et al. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneous superficialis: report of eight cases. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2011;1:25-30.

- Hoffmann E, Zurhelle E. Ubereinen nevus lipomatodes cutaneous superficialis der linkenglutaalgegend. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1921;130:327-333.