User login

VIDEO: Start probiotics within 2 days of antibiotics to prevent CDI

Starting probiotics within 2 days of the first antibiotic dose could cut the risk of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized adults by more than 50%, according to the results of a systemic review and metaregression analysis.

The protective effect waned when patients delayed starting probiotics, reported Nicole T. Shen, MD, of Cornell University, New York, and her associates. The study appears in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003). “Given the magnitude of benefit and the low cost of probiotics, the decision is likely to be highly cost effective,” they added.

Systematic reviews support the use of probiotics for preventing Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), but guidelines do not reflect these findings. To help guide clinical practice, the reviewers searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the International Journal of Probiotics and Prebiotics, and the Cochrane Library databases for randomized controlled trials of probiotics and CDI among hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. This search yielded 19 published studies of 6,261 patients. Two reviewers separately extracted data from these studies and examined quality of evidence and risk of bias.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

A total of 54 patients in the probiotic cohort (1.6%) developed CDI, compared with 115 controls (3.9%), a statistically significant difference (P less than .001). In regression analysis, the probiotic group was about 58% less likely to develop CDI than controls (hazard ratio, 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.57; P less than .001). Importantly, probiotics were significantly effective against CDI only when started within 2 days of antibiotic initiation (relative risk, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48), not when started within 3-7 days (RR, 0.70, 95% CI, 0.40-1.23). The difference between these estimated risk ratios was statistically significant (P = .02).

In 18 of the 19 studies, patients received probiotics within 3 days of starting antibiotics, while patients in the remaining study could start probiotics any time within 7 days of antibiotic initiation. “Not only was [this] study unusual with respect to probiotic timing, it was also much larger than all other studies, and its results were statistically insignificant,” the reviewers wrote. Metaregression analyses of all studies and of all but the outlier study linked delaying probiotics with a decrease in efficacy against CDI, with P values of .04 and .09, respectively. Those findings “suggest that the decrement in efficacy with delay in starting probiotics is not sensitive to inclusion of a single large ‘outlier’ study,” the reviewers emphasized. “In fact, inclusion only dampens the magnitude of the decrement in efficacy, although it is still clinically important and statistically significant.”

The trials included 12 probiotic formulas containing Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus, either alone or in combination. Probiotics were not associated with adverse effects in the trials. Quality of evidence was generally high, but seven trials had missing data on the primary outcome. Furthermore, two studies lacked a placebo group, and lead authors of two studies disclosed ties to the probiotic manufacturers that provided funding.

One reviewer received fellowship support from the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation. None had conflicts of interest.

Starting probiotics within 2 days of the first antibiotic dose could cut the risk of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized adults by more than 50%, according to the results of a systemic review and metaregression analysis.

The protective effect waned when patients delayed starting probiotics, reported Nicole T. Shen, MD, of Cornell University, New York, and her associates. The study appears in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003). “Given the magnitude of benefit and the low cost of probiotics, the decision is likely to be highly cost effective,” they added.

Systematic reviews support the use of probiotics for preventing Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), but guidelines do not reflect these findings. To help guide clinical practice, the reviewers searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the International Journal of Probiotics and Prebiotics, and the Cochrane Library databases for randomized controlled trials of probiotics and CDI among hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. This search yielded 19 published studies of 6,261 patients. Two reviewers separately extracted data from these studies and examined quality of evidence and risk of bias.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

A total of 54 patients in the probiotic cohort (1.6%) developed CDI, compared with 115 controls (3.9%), a statistically significant difference (P less than .001). In regression analysis, the probiotic group was about 58% less likely to develop CDI than controls (hazard ratio, 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.57; P less than .001). Importantly, probiotics were significantly effective against CDI only when started within 2 days of antibiotic initiation (relative risk, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48), not when started within 3-7 days (RR, 0.70, 95% CI, 0.40-1.23). The difference between these estimated risk ratios was statistically significant (P = .02).

In 18 of the 19 studies, patients received probiotics within 3 days of starting antibiotics, while patients in the remaining study could start probiotics any time within 7 days of antibiotic initiation. “Not only was [this] study unusual with respect to probiotic timing, it was also much larger than all other studies, and its results were statistically insignificant,” the reviewers wrote. Metaregression analyses of all studies and of all but the outlier study linked delaying probiotics with a decrease in efficacy against CDI, with P values of .04 and .09, respectively. Those findings “suggest that the decrement in efficacy with delay in starting probiotics is not sensitive to inclusion of a single large ‘outlier’ study,” the reviewers emphasized. “In fact, inclusion only dampens the magnitude of the decrement in efficacy, although it is still clinically important and statistically significant.”

The trials included 12 probiotic formulas containing Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus, either alone or in combination. Probiotics were not associated with adverse effects in the trials. Quality of evidence was generally high, but seven trials had missing data on the primary outcome. Furthermore, two studies lacked a placebo group, and lead authors of two studies disclosed ties to the probiotic manufacturers that provided funding.

One reviewer received fellowship support from the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation. None had conflicts of interest.

Starting probiotics within 2 days of the first antibiotic dose could cut the risk of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized adults by more than 50%, according to the results of a systemic review and metaregression analysis.

The protective effect waned when patients delayed starting probiotics, reported Nicole T. Shen, MD, of Cornell University, New York, and her associates. The study appears in Gastroenterology (doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.003). “Given the magnitude of benefit and the low cost of probiotics, the decision is likely to be highly cost effective,” they added.

Systematic reviews support the use of probiotics for preventing Clostridium difficile infection (CDI), but guidelines do not reflect these findings. To help guide clinical practice, the reviewers searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, the International Journal of Probiotics and Prebiotics, and the Cochrane Library databases for randomized controlled trials of probiotics and CDI among hospitalized adults taking antibiotics. This search yielded 19 published studies of 6,261 patients. Two reviewers separately extracted data from these studies and examined quality of evidence and risk of bias.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

A total of 54 patients in the probiotic cohort (1.6%) developed CDI, compared with 115 controls (3.9%), a statistically significant difference (P less than .001). In regression analysis, the probiotic group was about 58% less likely to develop CDI than controls (hazard ratio, 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.30-0.57; P less than .001). Importantly, probiotics were significantly effective against CDI only when started within 2 days of antibiotic initiation (relative risk, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48), not when started within 3-7 days (RR, 0.70, 95% CI, 0.40-1.23). The difference between these estimated risk ratios was statistically significant (P = .02).

In 18 of the 19 studies, patients received probiotics within 3 days of starting antibiotics, while patients in the remaining study could start probiotics any time within 7 days of antibiotic initiation. “Not only was [this] study unusual with respect to probiotic timing, it was also much larger than all other studies, and its results were statistically insignificant,” the reviewers wrote. Metaregression analyses of all studies and of all but the outlier study linked delaying probiotics with a decrease in efficacy against CDI, with P values of .04 and .09, respectively. Those findings “suggest that the decrement in efficacy with delay in starting probiotics is not sensitive to inclusion of a single large ‘outlier’ study,” the reviewers emphasized. “In fact, inclusion only dampens the magnitude of the decrement in efficacy, although it is still clinically important and statistically significant.”

The trials included 12 probiotic formulas containing Lactobacillus, Saccharomyces, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus, either alone or in combination. Probiotics were not associated with adverse effects in the trials. Quality of evidence was generally high, but seven trials had missing data on the primary outcome. Furthermore, two studies lacked a placebo group, and lead authors of two studies disclosed ties to the probiotic manufacturers that provided funding.

One reviewer received fellowship support from the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation. None had conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Starting probiotics within 2 days of antibiotics was associated with a significantly reduced risk of Clostridium difficile infection among hospitalized patients.

Major finding: Probiotics were significantly effective against CDI only when started within 2 days of antibiotic initiation (relative risk, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.22-0.48), not when started within 3-7 days (RR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.40-1.23).

Data source: A systematic review and metaregression analysis of 19 studies of 6,261 patients.

Disclosures: One reviewer received fellowship support from the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation. None had conflicts of interest.

Distance from transplant center predicted mortality in chronic liver disease

Living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center was associated with a higher risk of mortality among patients with chronic liver failure, regardless of etiology, transplantation status, or whether patients had decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to a first-in-kind, population-based study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.023).

The findings underscore the need for accessible, specialized liver care irrespective of whether patients with chronic liver failure (CLF) are destined for transplantation, David S. Goldberg, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote with his associates. The associations “do not provide cause and effect,” but underscore the need to consider “the broader impact of transplant-related policies that could decrease transplant volumes and threaten closures of smaller liver transplant centers that serve geographically isolated populations in the Southeast and Midwest,” they added.

A total of 879 (5.2%) patients lived more than 150 miles from the nearest liver transplant center, the analysis showed. Even after controlling for etiology of liver disease, this subgroup was at significantly greater risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-1.3; P less than .001) and of dying without undergoing transplantation (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P = .003) than were patients who were less geographically isolated. Distance from a transplant center also predicted overall and transplant-free mortality when modeled as a continuous variable, with hazard ratios of 1.02 (P = .02) and 1.03 (P = .04), respectively. “Although patients living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center had fewer outpatient gastroenterologist visits, this covariate did not affect the final models,” the investigators reported. Rural locality did not predict mortality after controlling for distance from a transplant center, and neither did living in a low-income zip code, they added.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that age-adjusted rates of death from liver disease are lowest in New York, where the entire population lives within 150 miles of a liver transplant center, the researchers noted. “By contrast, New Mexico and Wyoming have the highest age-adjusted death rates, and more than 95% of those states’ populations live more than 150 miles from a [transplant] center,” they emphasized. “The management of most patients with CLF is not centered on transplantation, but rather the spectrum of care for decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, maintaining access to specialized liver care is important for patients with CLF.”

Dr. Goldberg received support from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts.

Living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center was associated with a higher risk of mortality among patients with chronic liver failure, regardless of etiology, transplantation status, or whether patients had decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to a first-in-kind, population-based study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.023).

The findings underscore the need for accessible, specialized liver care irrespective of whether patients with chronic liver failure (CLF) are destined for transplantation, David S. Goldberg, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote with his associates. The associations “do not provide cause and effect,” but underscore the need to consider “the broader impact of transplant-related policies that could decrease transplant volumes and threaten closures of smaller liver transplant centers that serve geographically isolated populations in the Southeast and Midwest,” they added.

A total of 879 (5.2%) patients lived more than 150 miles from the nearest liver transplant center, the analysis showed. Even after controlling for etiology of liver disease, this subgroup was at significantly greater risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-1.3; P less than .001) and of dying without undergoing transplantation (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P = .003) than were patients who were less geographically isolated. Distance from a transplant center also predicted overall and transplant-free mortality when modeled as a continuous variable, with hazard ratios of 1.02 (P = .02) and 1.03 (P = .04), respectively. “Although patients living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center had fewer outpatient gastroenterologist visits, this covariate did not affect the final models,” the investigators reported. Rural locality did not predict mortality after controlling for distance from a transplant center, and neither did living in a low-income zip code, they added.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that age-adjusted rates of death from liver disease are lowest in New York, where the entire population lives within 150 miles of a liver transplant center, the researchers noted. “By contrast, New Mexico and Wyoming have the highest age-adjusted death rates, and more than 95% of those states’ populations live more than 150 miles from a [transplant] center,” they emphasized. “The management of most patients with CLF is not centered on transplantation, but rather the spectrum of care for decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, maintaining access to specialized liver care is important for patients with CLF.”

Dr. Goldberg received support from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts.

Living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center was associated with a higher risk of mortality among patients with chronic liver failure, regardless of etiology, transplantation status, or whether patients had decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, according to a first-in-kind, population-based study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.023).

The findings underscore the need for accessible, specialized liver care irrespective of whether patients with chronic liver failure (CLF) are destined for transplantation, David S. Goldberg, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote with his associates. The associations “do not provide cause and effect,” but underscore the need to consider “the broader impact of transplant-related policies that could decrease transplant volumes and threaten closures of smaller liver transplant centers that serve geographically isolated populations in the Southeast and Midwest,” they added.

A total of 879 (5.2%) patients lived more than 150 miles from the nearest liver transplant center, the analysis showed. Even after controlling for etiology of liver disease, this subgroup was at significantly greater risk of mortality (hazard ratio, 1.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.1-1.3; P less than .001) and of dying without undergoing transplantation (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P = .003) than were patients who were less geographically isolated. Distance from a transplant center also predicted overall and transplant-free mortality when modeled as a continuous variable, with hazard ratios of 1.02 (P = .02) and 1.03 (P = .04), respectively. “Although patients living more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center had fewer outpatient gastroenterologist visits, this covariate did not affect the final models,” the investigators reported. Rural locality did not predict mortality after controlling for distance from a transplant center, and neither did living in a low-income zip code, they added.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that age-adjusted rates of death from liver disease are lowest in New York, where the entire population lives within 150 miles of a liver transplant center, the researchers noted. “By contrast, New Mexico and Wyoming have the highest age-adjusted death rates, and more than 95% of those states’ populations live more than 150 miles from a [transplant] center,” they emphasized. “The management of most patients with CLF is not centered on transplantation, but rather the spectrum of care for decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, maintaining access to specialized liver care is important for patients with CLF.”

Dr. Goldberg received support from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Geographic isolation from a liver transplant center independently predicted mortality among patients with chronic liver failure.

Major finding: In adjusted analyses, patients who lived more than 150 miles from a liver transplant center were at significantly greater risk of mortality (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P less than .001) and of dying without undergoing transplantation (HR, 1.2; 95% CI, 1.1-1.3; P = .003) than were patients who were less geographically isolated.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of 16,824 patients with chronic liver failure who were included in the Healthcare Integrated Research Database between 2006 and 2014.

Disclosures: Dr. Goldberg received support from the National Institutes of Health. The investigators had no conflicts.

Time-to-Treatment Predicts Oral Cancer Survival

Oral cancer has a low 5-year survival rate compared with other major types of cancer, and the rate hasn’t improved much in recent years, say researchers from China Medical University, Asia University, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, and National Yang-Ming University; all in Taichung, Taiwan. That may be due in part to delay in treatment, they say. Their analysis of data of 21,263 patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) bears out their theory.

Related: Predicting Tongue Cancer Recurrence

About 40% of the patients presented with stage IV disease. More than one-third had tongue cancer. The average time from diagnosis to treatment was 24 days. Most patients (86%) were treated within 30 days of diagnosis; 12% were treated between 31 and 120 days after diagnosis, and 2.7% received treatment 120 days after diagnosis. Surgery was usually the first treatment.

The time interval from diagnosis to treatment (the phrase the researchers prefer to “treatment delay” or “wait time”) was an independent prognostic factor in OCSCC patients. The average interval was 24 days. Those treated within 30 days tended to have a higher survival rate. Treatment after 120 days from diagnosis increased the risk of death by 1.32-fold.

The average follow-up period was 44 months. When the researchers stratified patients according to the time between diagnosis and treatment, they found patients aged ≥ 65 years or who had advanced cancer were more likely to be treated later. Patients treated initially with radiotherapy or chemotherapy were more likely to have a longer mean time interval when compared with those who were treated first with surgery.

Related: Shorter Length of Stay May Not Mean Higher Readmission Rates

The researchers also found that patients treated in private hospitals had a shorter time interval compared with those treated in public hospitals (although the latter were more likely to survive). Patients who received treatment in hospitals with a low- to medium-service volume had a longer interval compared with those treated in hospitals with a high-service volume. Other predictors of longer survival included being female, younger, primary tumor site at the tongue, and earlier stage disease.

The researchers cite a study that found the median duration of clinical upstaging from early to late stage was 11.3 months, whereas the average period from advanced tumor to untreatable tumor was 3.8 months. That might explain why they found that the longer delay to treatment increased the risk of death, they suggest. The researchers also point to reasons such as pending second opinions, shortages of therapeutic instruments and manpower, and lack of public awareness.

Related: IBD and the Risk of Oral Cancer

All told however, the researchers conclude, the reasons for the increased time interval from diagnosis to treatment of OCSCC patients remain “multifaceted, integrated, and poorly understood.”

Source:

Tsai WC, Kung PT, Wang YH, Huang KH, Liu SA. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175148.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175148.

Oral cancer has a low 5-year survival rate compared with other major types of cancer, and the rate hasn’t improved much in recent years, say researchers from China Medical University, Asia University, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, and National Yang-Ming University; all in Taichung, Taiwan. That may be due in part to delay in treatment, they say. Their analysis of data of 21,263 patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) bears out their theory.

Related: Predicting Tongue Cancer Recurrence

About 40% of the patients presented with stage IV disease. More than one-third had tongue cancer. The average time from diagnosis to treatment was 24 days. Most patients (86%) were treated within 30 days of diagnosis; 12% were treated between 31 and 120 days after diagnosis, and 2.7% received treatment 120 days after diagnosis. Surgery was usually the first treatment.

The time interval from diagnosis to treatment (the phrase the researchers prefer to “treatment delay” or “wait time”) was an independent prognostic factor in OCSCC patients. The average interval was 24 days. Those treated within 30 days tended to have a higher survival rate. Treatment after 120 days from diagnosis increased the risk of death by 1.32-fold.

The average follow-up period was 44 months. When the researchers stratified patients according to the time between diagnosis and treatment, they found patients aged ≥ 65 years or who had advanced cancer were more likely to be treated later. Patients treated initially with radiotherapy or chemotherapy were more likely to have a longer mean time interval when compared with those who were treated first with surgery.

Related: Shorter Length of Stay May Not Mean Higher Readmission Rates

The researchers also found that patients treated in private hospitals had a shorter time interval compared with those treated in public hospitals (although the latter were more likely to survive). Patients who received treatment in hospitals with a low- to medium-service volume had a longer interval compared with those treated in hospitals with a high-service volume. Other predictors of longer survival included being female, younger, primary tumor site at the tongue, and earlier stage disease.

The researchers cite a study that found the median duration of clinical upstaging from early to late stage was 11.3 months, whereas the average period from advanced tumor to untreatable tumor was 3.8 months. That might explain why they found that the longer delay to treatment increased the risk of death, they suggest. The researchers also point to reasons such as pending second opinions, shortages of therapeutic instruments and manpower, and lack of public awareness.

Related: IBD and the Risk of Oral Cancer

All told however, the researchers conclude, the reasons for the increased time interval from diagnosis to treatment of OCSCC patients remain “multifaceted, integrated, and poorly understood.”

Source:

Tsai WC, Kung PT, Wang YH, Huang KH, Liu SA. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175148.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175148.

Oral cancer has a low 5-year survival rate compared with other major types of cancer, and the rate hasn’t improved much in recent years, say researchers from China Medical University, Asia University, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, and National Yang-Ming University; all in Taichung, Taiwan. That may be due in part to delay in treatment, they say. Their analysis of data of 21,263 patients with oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (OCSCC) bears out their theory.

Related: Predicting Tongue Cancer Recurrence

About 40% of the patients presented with stage IV disease. More than one-third had tongue cancer. The average time from diagnosis to treatment was 24 days. Most patients (86%) were treated within 30 days of diagnosis; 12% were treated between 31 and 120 days after diagnosis, and 2.7% received treatment 120 days after diagnosis. Surgery was usually the first treatment.

The time interval from diagnosis to treatment (the phrase the researchers prefer to “treatment delay” or “wait time”) was an independent prognostic factor in OCSCC patients. The average interval was 24 days. Those treated within 30 days tended to have a higher survival rate. Treatment after 120 days from diagnosis increased the risk of death by 1.32-fold.

The average follow-up period was 44 months. When the researchers stratified patients according to the time between diagnosis and treatment, they found patients aged ≥ 65 years or who had advanced cancer were more likely to be treated later. Patients treated initially with radiotherapy or chemotherapy were more likely to have a longer mean time interval when compared with those who were treated first with surgery.

Related: Shorter Length of Stay May Not Mean Higher Readmission Rates

The researchers also found that patients treated in private hospitals had a shorter time interval compared with those treated in public hospitals (although the latter were more likely to survive). Patients who received treatment in hospitals with a low- to medium-service volume had a longer interval compared with those treated in hospitals with a high-service volume. Other predictors of longer survival included being female, younger, primary tumor site at the tongue, and earlier stage disease.

The researchers cite a study that found the median duration of clinical upstaging from early to late stage was 11.3 months, whereas the average period from advanced tumor to untreatable tumor was 3.8 months. That might explain why they found that the longer delay to treatment increased the risk of death, they suggest. The researchers also point to reasons such as pending second opinions, shortages of therapeutic instruments and manpower, and lack of public awareness.

Related: IBD and the Risk of Oral Cancer

All told however, the researchers conclude, the reasons for the increased time interval from diagnosis to treatment of OCSCC patients remain “multifaceted, integrated, and poorly understood.”

Source:

Tsai WC, Kung PT, Wang YH, Huang KH, Liu SA. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175148.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175148.

My, How You've Grown

Six years ago, a lesion appeared on this now 39-year-old woman’s forehead. It grew steadily to its current size, impinging on her brow line. Although it has been asymptomatic, the patient is concerned about malignancy, since she has a significant personal and family history of skin cancer. She has had several lesions removed from her face and back over the years.

EXAMINATION

There is a 2.2-cm, roughly round, white, cicatricial, concave lesion on the patient’s lower right forehead, extending into the brow line. Around the periphery are several 2- to 5-mm eroded papules. There are no palpable nodes on the head or neck.

Several scars are seen elsewhere on the patient’s face and back, consistent with her history. Her type II/VI skin is quite fair and sun-damaged.

A 6-mm deep punch biopsy of the lesion is obtained.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Biopsy reveals a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC; also known as cicatricial BCC) with perineural involvement that extends to the margin of the sample. While BCCs are almost never fatal, if ignored, their relentless growth can be problematic. This case illustrates that, along with the wide variety of morphologic presentations.

Of the different types of BCC, the most common are nodular. These present as pearly (ie, translucent) papules or nodules, with or without focal erosion or frank ulceration; they often have prominent telangiectasias coursing over their surfaces. BCCs can also appear as rashes (superficial BCC) that may not attract attention.

This patient’s lesion is one of the least common variations: It combines features of a morpheaform (scarlike) BCC with focal noduloulcerative papular lesions studding its periphery. The concavity of the scarlike portion, along with its prolonged presence, predicted deep involvement of adjacent tissue—confirmed by the biopsy results.

At a minimum, this patient will need Mohs micrographic surgical removal, with closure by skin graft or secondary intention. Given the deep perineural involvement, surgery alone may not clear the cancer; radiation therapy may be necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), also known as cicatricial BCC, can present as a white, scarlike patch, often with an atrophic surface.

- This type of BCC is more aggressive than most, often requiring Mohs surgery.

- There are at least three other types of BCC, most of which involve nonhealing ulcerative papules or nodules.

- This patient’s history of sun-caused skin cancers makes recurrence likely.

Six years ago, a lesion appeared on this now 39-year-old woman’s forehead. It grew steadily to its current size, impinging on her brow line. Although it has been asymptomatic, the patient is concerned about malignancy, since she has a significant personal and family history of skin cancer. She has had several lesions removed from her face and back over the years.

EXAMINATION

There is a 2.2-cm, roughly round, white, cicatricial, concave lesion on the patient’s lower right forehead, extending into the brow line. Around the periphery are several 2- to 5-mm eroded papules. There are no palpable nodes on the head or neck.

Several scars are seen elsewhere on the patient’s face and back, consistent with her history. Her type II/VI skin is quite fair and sun-damaged.

A 6-mm deep punch biopsy of the lesion is obtained.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Biopsy reveals a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC; also known as cicatricial BCC) with perineural involvement that extends to the margin of the sample. While BCCs are almost never fatal, if ignored, their relentless growth can be problematic. This case illustrates that, along with the wide variety of morphologic presentations.

Of the different types of BCC, the most common are nodular. These present as pearly (ie, translucent) papules or nodules, with or without focal erosion or frank ulceration; they often have prominent telangiectasias coursing over their surfaces. BCCs can also appear as rashes (superficial BCC) that may not attract attention.

This patient’s lesion is one of the least common variations: It combines features of a morpheaform (scarlike) BCC with focal noduloulcerative papular lesions studding its periphery. The concavity of the scarlike portion, along with its prolonged presence, predicted deep involvement of adjacent tissue—confirmed by the biopsy results.

At a minimum, this patient will need Mohs micrographic surgical removal, with closure by skin graft or secondary intention. Given the deep perineural involvement, surgery alone may not clear the cancer; radiation therapy may be necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), also known as cicatricial BCC, can present as a white, scarlike patch, often with an atrophic surface.

- This type of BCC is more aggressive than most, often requiring Mohs surgery.

- There are at least three other types of BCC, most of which involve nonhealing ulcerative papules or nodules.

- This patient’s history of sun-caused skin cancers makes recurrence likely.

Six years ago, a lesion appeared on this now 39-year-old woman’s forehead. It grew steadily to its current size, impinging on her brow line. Although it has been asymptomatic, the patient is concerned about malignancy, since she has a significant personal and family history of skin cancer. She has had several lesions removed from her face and back over the years.

EXAMINATION

There is a 2.2-cm, roughly round, white, cicatricial, concave lesion on the patient’s lower right forehead, extending into the brow line. Around the periphery are several 2- to 5-mm eroded papules. There are no palpable nodes on the head or neck.

Several scars are seen elsewhere on the patient’s face and back, consistent with her history. Her type II/VI skin is quite fair and sun-damaged.

A 6-mm deep punch biopsy of the lesion is obtained.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

Biopsy reveals a morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC; also known as cicatricial BCC) with perineural involvement that extends to the margin of the sample. While BCCs are almost never fatal, if ignored, their relentless growth can be problematic. This case illustrates that, along with the wide variety of morphologic presentations.

Of the different types of BCC, the most common are nodular. These present as pearly (ie, translucent) papules or nodules, with or without focal erosion or frank ulceration; they often have prominent telangiectasias coursing over their surfaces. BCCs can also appear as rashes (superficial BCC) that may not attract attention.

This patient’s lesion is one of the least common variations: It combines features of a morpheaform (scarlike) BCC with focal noduloulcerative papular lesions studding its periphery. The concavity of the scarlike portion, along with its prolonged presence, predicted deep involvement of adjacent tissue—confirmed by the biopsy results.

At a minimum, this patient will need Mohs micrographic surgical removal, with closure by skin graft or secondary intention. Given the deep perineural involvement, surgery alone may not clear the cancer; radiation therapy may be necessary.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

- Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma (BCC), also known as cicatricial BCC, can present as a white, scarlike patch, often with an atrophic surface.

- This type of BCC is more aggressive than most, often requiring Mohs surgery.

- There are at least three other types of BCC, most of which involve nonhealing ulcerative papules or nodules.

- This patient’s history of sun-caused skin cancers makes recurrence likely.

Persistently nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus did not protect against progression

Patients with at least five biopsies showing nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus were statistically as likely to progress to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma as patients with a single such biopsy, according to a multicenter prospective registry study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.019).

The findings, which contradict those from another recent multicenter cohort study (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[3]:548-53), highlight the need for more studies before lengthening the time between surveillance biopsies in patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., wrote with his associates.

Barrett’s esophagus is the strongest predictor of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but studies have reported mixed results as to whether the risk of this cancer increases over time or wanes with consecutive biopsies that indicate nondysplasia, the researchers noted. Therefore, they studied the prospective, multicenter Mayo Clinic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s Esophagus registry, excluding patients who progressed to adenocarcinoma within 12 months, had missing data, or had no follow-up biopsies. This approach left 480 subjects for analysis. Patients averaged 63 years of age, 78% were male, the mean length of Barrett’s esophagus was 5.7 cm, and the average time between biopsies was 1.8 years, with a standard deviation of 1.3 years.

A total of 16 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma over 1,832 patient-years of follow-up, for an overall annual risk of progression of 0.87%. Two patients progressed to esophageal adenocarcinoma (annual risk, 0.11%; 95% confidence interval, 0.03% to 0.44%), while 14 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia (annual risk, 0.76%; 95% CI, 0.45% to 1.29%). Eight patients progressed to one of these two outcomes after a single nondysplastic biopsy, three progressed after two such biopsies, three progressed after three such biopsies, none progressed after four such biopsies, and two progressed after five such biopsies. Statistically, patients with at least five consecutive nondysplastic biopsies were no less likely to progress than were patients with only one nondysplastic biopsy (hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.07 to 1.92; P = .32). Hazard ratios for the other groups ranged between 0.0 and 0.85, with no significant difference in estimated risk between groups (P = .68) after controlling for age, sex, and length of Barrett’s esophagus.

The previous multicenter cohort study linked persistently nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus with a lower rate of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, and, based on those findings, the authors suggested lengthening intervals between biopsy surveillance or even stopping surveillance, Dr. Krishnamoorthi and his associates noted. However, that study did not have mutually exclusive groups. “Additional data are required before increasing the interval between surveillance endoscopies based on persistence of nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus,” they concluded.

The study lacked misclassification bias given long-segment Barrett’s esophagus, and specialized gastrointestinal pathologists interpreted all histology specimens, the researchers noted. “The small number of progressors is a potential limitation, reducing power to assess associations,” they added.

The investigators did not report funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

Current practice guidelines recommend endoscopic surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients to detect esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) at an early and potentially curable stage.

As currently practiced, endoscopic surveillance of BE has numerous limitations and provides the impetus for improved risk-stratification and, ultimately, the effectiveness of current surveillance strategies. Persistence of nondysplastic BE (NDBE) has previously been shown to be an indicator of lower risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/EAC. However, outcomes studies on this topic have reported conflicting results.

Where do we stand with regard to persistence of NDBE and its impact on surveillance intervals? Future large cohort studies are required that address all potential confounders and include a large number of patients with progression to HGD/EAC (a challenge given the rarity of this outcome). At the present time, based on the available data, surveillance intervals cannot be lengthened in patients with persistent NDBE. Future studies also need to focus on the development and validation of prediction models that incorporate clinical, endoscopic, and histologic factors in risk stratification. Until then, meticulous examination techniques, cognitive knowledge and training, use of standardized grading systems, and use of high-definition white light endoscopy are critical in improving effectiveness of surveillance programs in BE patients.

Sachin Wani, MD, is associate professor of medicine and Medical codirector of the Esophageal and Gastric Center of Excellence, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He is supported by the University of Colorado Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Scholars Program and is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

Current practice guidelines recommend endoscopic surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients to detect esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) at an early and potentially curable stage.

As currently practiced, endoscopic surveillance of BE has numerous limitations and provides the impetus for improved risk-stratification and, ultimately, the effectiveness of current surveillance strategies. Persistence of nondysplastic BE (NDBE) has previously been shown to be an indicator of lower risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/EAC. However, outcomes studies on this topic have reported conflicting results.

Where do we stand with regard to persistence of NDBE and its impact on surveillance intervals? Future large cohort studies are required that address all potential confounders and include a large number of patients with progression to HGD/EAC (a challenge given the rarity of this outcome). At the present time, based on the available data, surveillance intervals cannot be lengthened in patients with persistent NDBE. Future studies also need to focus on the development and validation of prediction models that incorporate clinical, endoscopic, and histologic factors in risk stratification. Until then, meticulous examination techniques, cognitive knowledge and training, use of standardized grading systems, and use of high-definition white light endoscopy are critical in improving effectiveness of surveillance programs in BE patients.

Sachin Wani, MD, is associate professor of medicine and Medical codirector of the Esophageal and Gastric Center of Excellence, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He is supported by the University of Colorado Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Scholars Program and is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

Current practice guidelines recommend endoscopic surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus (BE) patients to detect esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) at an early and potentially curable stage.

As currently practiced, endoscopic surveillance of BE has numerous limitations and provides the impetus for improved risk-stratification and, ultimately, the effectiveness of current surveillance strategies. Persistence of nondysplastic BE (NDBE) has previously been shown to be an indicator of lower risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia (HGD)/EAC. However, outcomes studies on this topic have reported conflicting results.

Where do we stand with regard to persistence of NDBE and its impact on surveillance intervals? Future large cohort studies are required that address all potential confounders and include a large number of patients with progression to HGD/EAC (a challenge given the rarity of this outcome). At the present time, based on the available data, surveillance intervals cannot be lengthened in patients with persistent NDBE. Future studies also need to focus on the development and validation of prediction models that incorporate clinical, endoscopic, and histologic factors in risk stratification. Until then, meticulous examination techniques, cognitive knowledge and training, use of standardized grading systems, and use of high-definition white light endoscopy are critical in improving effectiveness of surveillance programs in BE patients.

Sachin Wani, MD, is associate professor of medicine and Medical codirector of the Esophageal and Gastric Center of Excellence, division of gastroenterology and hepatology, University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. He is supported by the University of Colorado Department of Medicine Outstanding Early Scholars Program and is a consultant for Medtronic and Boston Scientific.

Patients with at least five biopsies showing nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus were statistically as likely to progress to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma as patients with a single such biopsy, according to a multicenter prospective registry study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.019).

The findings, which contradict those from another recent multicenter cohort study (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[3]:548-53), highlight the need for more studies before lengthening the time between surveillance biopsies in patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., wrote with his associates.

Barrett’s esophagus is the strongest predictor of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but studies have reported mixed results as to whether the risk of this cancer increases over time or wanes with consecutive biopsies that indicate nondysplasia, the researchers noted. Therefore, they studied the prospective, multicenter Mayo Clinic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s Esophagus registry, excluding patients who progressed to adenocarcinoma within 12 months, had missing data, or had no follow-up biopsies. This approach left 480 subjects for analysis. Patients averaged 63 years of age, 78% were male, the mean length of Barrett’s esophagus was 5.7 cm, and the average time between biopsies was 1.8 years, with a standard deviation of 1.3 years.

A total of 16 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma over 1,832 patient-years of follow-up, for an overall annual risk of progression of 0.87%. Two patients progressed to esophageal adenocarcinoma (annual risk, 0.11%; 95% confidence interval, 0.03% to 0.44%), while 14 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia (annual risk, 0.76%; 95% CI, 0.45% to 1.29%). Eight patients progressed to one of these two outcomes after a single nondysplastic biopsy, three progressed after two such biopsies, three progressed after three such biopsies, none progressed after four such biopsies, and two progressed after five such biopsies. Statistically, patients with at least five consecutive nondysplastic biopsies were no less likely to progress than were patients with only one nondysplastic biopsy (hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.07 to 1.92; P = .32). Hazard ratios for the other groups ranged between 0.0 and 0.85, with no significant difference in estimated risk between groups (P = .68) after controlling for age, sex, and length of Barrett’s esophagus.

The previous multicenter cohort study linked persistently nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus with a lower rate of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, and, based on those findings, the authors suggested lengthening intervals between biopsy surveillance or even stopping surveillance, Dr. Krishnamoorthi and his associates noted. However, that study did not have mutually exclusive groups. “Additional data are required before increasing the interval between surveillance endoscopies based on persistence of nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus,” they concluded.

The study lacked misclassification bias given long-segment Barrett’s esophagus, and specialized gastrointestinal pathologists interpreted all histology specimens, the researchers noted. “The small number of progressors is a potential limitation, reducing power to assess associations,” they added.

The investigators did not report funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

Patients with at least five biopsies showing nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus were statistically as likely to progress to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma as patients with a single such biopsy, according to a multicenter prospective registry study reported in the June issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.02.019).

The findings, which contradict those from another recent multicenter cohort study (Gastroenterology. 2013;145[3]:548-53), highlight the need for more studies before lengthening the time between surveillance biopsies in patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus, Rajesh Krishnamoorthi, MD, of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., wrote with his associates.

Barrett’s esophagus is the strongest predictor of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but studies have reported mixed results as to whether the risk of this cancer increases over time or wanes with consecutive biopsies that indicate nondysplasia, the researchers noted. Therefore, they studied the prospective, multicenter Mayo Clinic Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s Esophagus registry, excluding patients who progressed to adenocarcinoma within 12 months, had missing data, or had no follow-up biopsies. This approach left 480 subjects for analysis. Patients averaged 63 years of age, 78% were male, the mean length of Barrett’s esophagus was 5.7 cm, and the average time between biopsies was 1.8 years, with a standard deviation of 1.3 years.

A total of 16 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma over 1,832 patient-years of follow-up, for an overall annual risk of progression of 0.87%. Two patients progressed to esophageal adenocarcinoma (annual risk, 0.11%; 95% confidence interval, 0.03% to 0.44%), while 14 patients progressed to high-grade dysplasia (annual risk, 0.76%; 95% CI, 0.45% to 1.29%). Eight patients progressed to one of these two outcomes after a single nondysplastic biopsy, three progressed after two such biopsies, three progressed after three such biopsies, none progressed after four such biopsies, and two progressed after five such biopsies. Statistically, patients with at least five consecutive nondysplastic biopsies were no less likely to progress than were patients with only one nondysplastic biopsy (hazard ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.07 to 1.92; P = .32). Hazard ratios for the other groups ranged between 0.0 and 0.85, with no significant difference in estimated risk between groups (P = .68) after controlling for age, sex, and length of Barrett’s esophagus.

The previous multicenter cohort study linked persistently nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus with a lower rate of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, and, based on those findings, the authors suggested lengthening intervals between biopsy surveillance or even stopping surveillance, Dr. Krishnamoorthi and his associates noted. However, that study did not have mutually exclusive groups. “Additional data are required before increasing the interval between surveillance endoscopies based on persistence of nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus,” they concluded.

The study lacked misclassification bias given long-segment Barrett’s esophagus, and specialized gastrointestinal pathologists interpreted all histology specimens, the researchers noted. “The small number of progressors is a potential limitation, reducing power to assess associations,” they added.

The investigators did not report funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Patients with multiple consecutive biopsies showing nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus were statistically as likely to progress to esophageal adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia as those with a single nondysplastic biopsy.

Major finding: Hazard ratios for progression ranged between 0.00 and 0.85, with no significant difference in estimated risk among groups stratified by number of consecutive nondysplastic biopsies (P = .68), after controlling for age, sex, and length of Barrett’s esophagus.

Data source: A prospective multicenter registry of 480 patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus and multiple surveillance biopsies.

Disclosures: The investigators did not report funding sources. They reported having no conflicts of interest.

Combating Public Pathogens in Federal Health Care Systems (June 2017)

Click here to access Combating Public Pathogens in Federal Health Care Systems

Table of Contents

- Open Clinical Trials for Patients With HIV and/or Viral Hepatitis

- HIV Update: Which Single-Tablet Regimens, and When

- Improving Veteran Access to Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection

- Strategies to Improve Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Veterans With Hepatitis B Virus Infection

- Heart Transplantation Outcomes in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Potential Impact of Newer Antiviral Treatments After Transplantation

Click here to access Combating Public Pathogens in Federal Health Care Systems

Table of Contents

- Open Clinical Trials for Patients With HIV and/or Viral Hepatitis

- HIV Update: Which Single-Tablet Regimens, and When

- Improving Veteran Access to Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection

- Strategies to Improve Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Veterans With Hepatitis B Virus Infection

- Heart Transplantation Outcomes in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Potential Impact of Newer Antiviral Treatments After Transplantation

Click here to access Combating Public Pathogens in Federal Health Care Systems

Table of Contents

- Open Clinical Trials for Patients With HIV and/or Viral Hepatitis

- HIV Update: Which Single-Tablet Regimens, and When

- Improving Veteran Access to Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection

- Strategies to Improve Hepatocellular Carcinoma Surveillance in Veterans With Hepatitis B Virus Infection

- Heart Transplantation Outcomes in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Potential Impact of Newer Antiviral Treatments After Transplantation

June 2017 Digital Edition

Click here to access the June 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Pathway to Full Practice Authority for Physician Assistants in the VA

- Outcomes Associated With a Multidisciplinary Pain Oversight Committee to Facilitate Management of Chronic Opioid Therapy

- Quality of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Related Health Care in Rural and Urban Clinics

- Three Anomalies and a Complication: Ruptured Noncoronary Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm, Atrial Septal Aneurysm, and Patent Foramen Ovale

- Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating

- Interprofessional Education in PACT Primary Care-Mental Health Integration

Click here to access the June 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Pathway to Full Practice Authority for Physician Assistants in the VA

- Outcomes Associated With a Multidisciplinary Pain Oversight Committee to Facilitate Management of Chronic Opioid Therapy

- Quality of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Related Health Care in Rural and Urban Clinics

- Three Anomalies and a Complication: Ruptured Noncoronary Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm, Atrial Septal Aneurysm, and Patent Foramen Ovale

- Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating

- Interprofessional Education in PACT Primary Care-Mental Health Integration

Click here to access the June 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- A Pathway to Full Practice Authority for Physician Assistants in the VA

- Outcomes Associated With a Multidisciplinary Pain Oversight Committee to Facilitate Management of Chronic Opioid Therapy

- Quality of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease-Related Health Care in Rural and Urban Clinics

- Three Anomalies and a Complication: Ruptured Noncoronary Sinus of Valsalva Aneurysm, Atrial Septal Aneurysm, and Patent Foramen Ovale

- Orthorexia Nervosa: An Obsession With Healthy Eating

- Interprofessional Education in PACT Primary Care-Mental Health Integration

Long-Term Effects of Concussive TBI

What are the long-term clinical effects of wartime traumatic brain injuries (TBIs)? Most are mild, but in general all are incompletely described, say researchers from University of Washington in Seattle and Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. However, their own study found that service members with even mild concussive TBI often “experienced evolution, not resolution” of symptoms.

The researchers compared the results of 1-year and 5-year clinical evaluations of 50 active-duty U.S. military with acute to subacute concussive blast injury and 44 deployed but uninjured service members. The evaluations included neurobehavioral and neuropsychological performance and mental health burden.

At 5 years, global disability, satisfaction with life, neurobehavioral symptom severity, psychiatric symptom severity, and sleep impairment were significantly worse in patients with concussive blast TBI. Of the patients with concussive blast TBI, 36 (72%) showed decline, compared with only 5 of the combat-deployed group (11%). The researchers also found symptoms of PTSD and depression worsened in the concussive TBI patients. Performance on cognitive measures was no different between the 2 groups. A combination of factors, including neurobehavioral symptom severity, walking ability, and verbal fluency at 1 year after injury, was highly predictive of poor outcomes 5 years later.

“This is one of the first studies to connect the dots from injury to longer term outcomes and it shows that even mild concussions can lead to long-term impairment and continued decline in satisfaction with life,” said lead author Christine L. Mac Donald, PhD. “Most physicians believe that patients will stabilize 6 to 12 months postinjury, but this study challenges that.”

What are the long-term clinical effects of wartime traumatic brain injuries (TBIs)? Most are mild, but in general all are incompletely described, say researchers from University of Washington in Seattle and Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. However, their own study found that service members with even mild concussive TBI often “experienced evolution, not resolution” of symptoms.

The researchers compared the results of 1-year and 5-year clinical evaluations of 50 active-duty U.S. military with acute to subacute concussive blast injury and 44 deployed but uninjured service members. The evaluations included neurobehavioral and neuropsychological performance and mental health burden.

At 5 years, global disability, satisfaction with life, neurobehavioral symptom severity, psychiatric symptom severity, and sleep impairment were significantly worse in patients with concussive blast TBI. Of the patients with concussive blast TBI, 36 (72%) showed decline, compared with only 5 of the combat-deployed group (11%). The researchers also found symptoms of PTSD and depression worsened in the concussive TBI patients. Performance on cognitive measures was no different between the 2 groups. A combination of factors, including neurobehavioral symptom severity, walking ability, and verbal fluency at 1 year after injury, was highly predictive of poor outcomes 5 years later.

“This is one of the first studies to connect the dots from injury to longer term outcomes and it shows that even mild concussions can lead to long-term impairment and continued decline in satisfaction with life,” said lead author Christine L. Mac Donald, PhD. “Most physicians believe that patients will stabilize 6 to 12 months postinjury, but this study challenges that.”

What are the long-term clinical effects of wartime traumatic brain injuries (TBIs)? Most are mild, but in general all are incompletely described, say researchers from University of Washington in Seattle and Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. However, their own study found that service members with even mild concussive TBI often “experienced evolution, not resolution” of symptoms.

The researchers compared the results of 1-year and 5-year clinical evaluations of 50 active-duty U.S. military with acute to subacute concussive blast injury and 44 deployed but uninjured service members. The evaluations included neurobehavioral and neuropsychological performance and mental health burden.

At 5 years, global disability, satisfaction with life, neurobehavioral symptom severity, psychiatric symptom severity, and sleep impairment were significantly worse in patients with concussive blast TBI. Of the patients with concussive blast TBI, 36 (72%) showed decline, compared with only 5 of the combat-deployed group (11%). The researchers also found symptoms of PTSD and depression worsened in the concussive TBI patients. Performance on cognitive measures was no different between the 2 groups. A combination of factors, including neurobehavioral symptom severity, walking ability, and verbal fluency at 1 year after injury, was highly predictive of poor outcomes 5 years later.

“This is one of the first studies to connect the dots from injury to longer term outcomes and it shows that even mild concussions can lead to long-term impairment and continued decline in satisfaction with life,” said lead author Christine L. Mac Donald, PhD. “Most physicians believe that patients will stabilize 6 to 12 months postinjury, but this study challenges that.”

How One GI Is Tackling His Student Debt – And the Lessons He’s Learned Along the Way

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

The AGA recently partnered with CommonBond (studentloans.gastro.org) to help its members save thousands by refinancing their student loans. Kevin Tin, MD, who is an AGA member, has a student loan story that can certainly offer guidance and perspective to others. Kevin earned his B.S. in health sciences from Stony Brook University and his M.D. from American University of Antigua. He completed his residency at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he is currently a gastroenterology fellow.

How was your medical school experience?

My medical school experience was memorable for many reasons, particularly because I had an opportunity to study in Antigua. My time there allowed me to experience a different culture and, ultimately, a different perspective. I believe this taught me how to relate to each of my patients’ individual situations and to see things from their eyes. But, the overall cost of medical school (i.e., tuition, cost of living, medical supplies, and study resources) caught me off guard. By the time I graduated, I had amassed more than $200,000 in student loans; this was not something that I felt prepared to deal with.

How would you describe your initial experience with student loans?

What strategies have you implemented to pay off your student loans?

I’ve learned a few crucial strategies that any physician could, and should, take advantage of to save money on their student loans. First, be sure to spend responsibly while in medical school. I focused on finding free study resources and medical supplies as well as sharing materials with friends and roommates whenever possible. As I mentioned earlier, make small payments when you can; as soon as I entered residency, I started making interest payments on my loans. I wanted to contribute as much as I could, as early as I could, to get out of debt. Second, after graduation, endeavor to live frugally. Although I knew my salary would ultimately increase, I saved as much money as I could and put money toward paying off my loans. Finally, try to refinance your student loans; I refinanced mine with CommonBond. It was an unexpectedly pleasant experience: the website was extremely easy to navigate and any time I needed help, a representative was available to answer my questions. CommonBond also gave me the best rates I could find.

What were the benefits of refinancing your student loans?

What is your advice to early-career GIs who have or need to take out loans?

Do your research and do it early. While in medical school, understand what options are available to you and learn to live within your means. In your residency, plan to use a portion of your salary for paying off your student loans, even if it is only a small amount each month. This will reduce the volume of interest that will capitalize, so your loan balance doesn’t grow over time. When you start your full-time job, be financially responsible and limit your spending so you can devote additional funds to paying off your student loans.

If you would like to learn more about student loan refinancing with CommonBond, please visit studentloans.gastro.org. AGA members get a $200 cash bonus for refinancing!

Ms. Duggal is vice president of marketing for CommonBond.

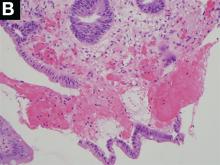

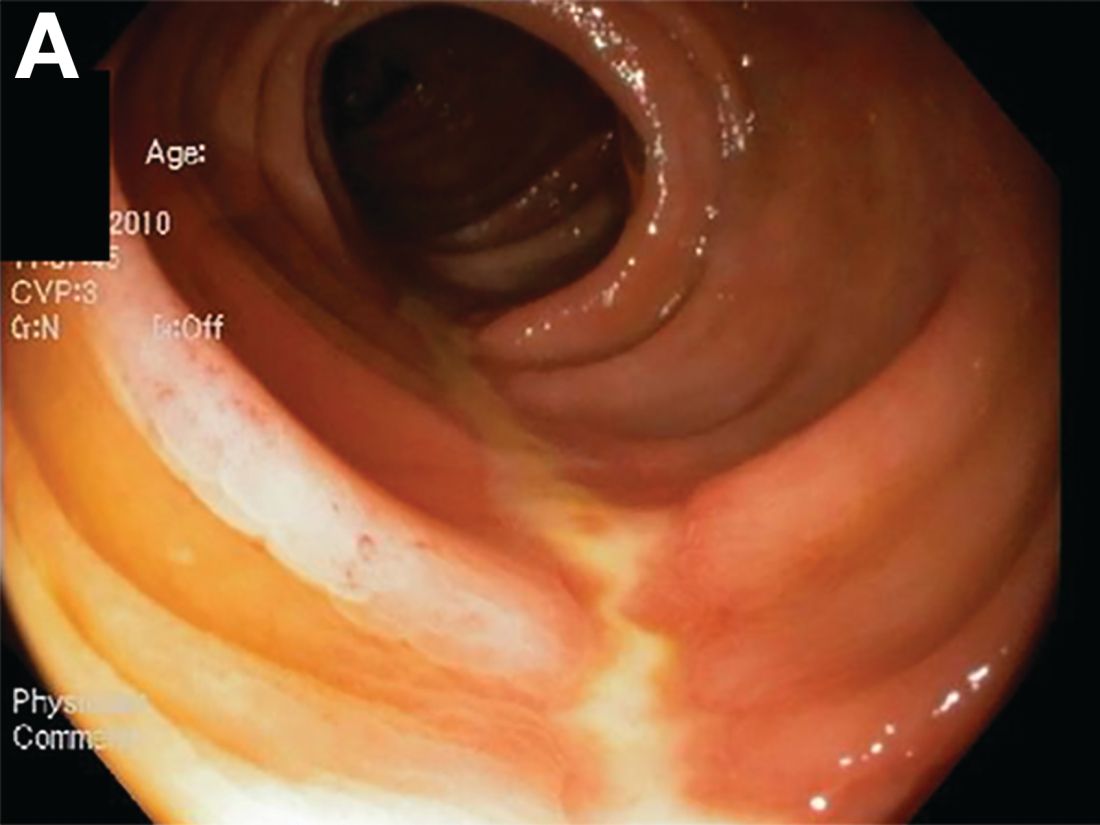

A Rare Endoscopic Clue to a Common Clinical Condition

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2017;152:492-3)

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Sweetser are in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.