User login

Severe right hip pain

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

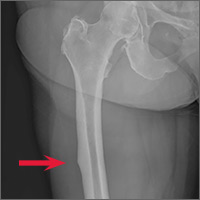

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

A 63-year-old woman with a 3-year history of osteoporosis presented to our clinic with a 2-week history of severe right hip pain. She had been taking a bisphosphonate—oral ibandronate sodium, 150 mg, once monthly—for about 6 years. The postmenopausal patient had a history of degenerative disc disease and lumbar back pain, but no known history of recent trauma or falls.

A clinical exam revealed full passive and active range of motion; however, she had pain with weight bearing. A full metabolic panel revealed no significant abnormalities. A leg length discrepancy was noted, so a bone length study was ordered. Anteroposterior x-rays of the bilateral lower extremities demonstrated a focal convexity along the lateral cortical junction of the proximal right femur (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Bisphosphonate-associated proximal insufficiency fracture

Based on the patient’s clinical history and x-ray findings, we determined that the patient had sustained a bisphosphonate-associated proximal femoral insufficiency fracture. Insufficiency fractures arise from normal physiologic stress on abnormal bone. They commonly occur in conditions that impair normal bone physiology and remodeling, such as osteoporosis, renal insufficiency, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.1

Could a bisphosphonate be to blame? Bisphosphonate therapy has been associated with significant benefits, including increased bone mineral density (BMD), decreased incidence of fracture, and improved mortality.2-4 But it’s been postulated that the global suppression of bone turnover caused by these drugs may also impair the bone remodeling process.5 Some case reports have suggested an association between chronic bisphosphonate use and atypical insufficiency fractures. These atypical femur fractures are characterized by their location (along the diaphysis in the region distal to the lesser trochanter), the patient’s history (there may be minimal to no trauma), and the potential for “beaking” (localized periosteal or endosteal thickening of the lateral cortex).6,7

Several large, population-based, case-control studies have found a temporal relationship between bisphosphonate therapy and a statistically significant increased risk of subtrochanteric fractures.8-10 These studies do note, however, that the absolute risk of insufficiency fracture is very low, and that the benefits of bisphosphonate therapy greatly outweigh the risks. A 2013 meta-analysis came to the same conclusion.11

Treatment options include PT, surgical intervention

When an insufficiency fracture is identified in a patient taking a bisphosphonate, the medication should be discontinued and a consultation with Endocrinology should be arranged. Nonsurgical management ranges from physical therapy to alternative medication regimens, such as teriparatide—a recombinant human parathyroid hormone used to restore bone quality. A variety of surgical stabilization options are also available.6

In contrast to typical subtrochanteric fractures, about half of patients with atypical insufficiency fractures demonstrate poor fracture healing that requires surgical intervention.12 Complete fractures almost always require surgery, while incomplete subtrochanteric femur fractures can usually be managed conservatively by altering pharmacologic prophylaxis (interval dosing or discontinuation of the bisphosphonate and initiation of an alternative therapy like teriparatide) in conjunction with routine radiologic surveillance. Internal fixation may be considered for cases of persistent pain or those that progress to an unstable fracture.13

Our patient declined surgical intervention. We switched her monthly ibandronate dosage to a periodic dosing schedule (6 months on, followed by 6 months off) and advised her to rest and take nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs when needed. While consensus guidelines exist for the management of osteoporosis (see Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient’s risk), there is still debate over the optimal length of bisphosphonate therapy and the impact of drug holidays; a recent review in The BMJ discusses bisphosphonate use in detail.5

SIDEBAR

Osteoporosis: Assessing your patient's riskApproximately 9.9 million Americans have osteoporosis, and while the disease is more common in Caucasian females, patients with osteoporosis have the same elevated fracture risk regardless of their race.14 The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends bone mineral density (BMD) testing for all women ages 65 years and older (earlier if risk factor profile warrants).15

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), patients with BMD T-scores at the hip or lumbar spine that are ≤2.5 standard deviations below the mean BMD of a young-adult reference population are at highest risk for osteoporotic fractures.16 There are also free online risk assessment tools, like the WHO’s FRAX calculator (available at: http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/tool.jsp?locationValue=9), which integrate clinical data to generate an evidence-based assessment of fracture risk.17

Follow-up x-rays 14 months later revealed that the insufficiency fracture had healed with a bony callus.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joseph S. McMonagle, MD, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Department of Radiology, P.O. Box 1980, Norfolk, VA; [email protected].

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

1. Sheehan SE, Shyu JY, Weaver MJ, et al. Proximal femoral fractures: what the orthopedic surgeon wants to know. Radiographics. 2015;35:1563-1584.

2. Wells G, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Risedronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD004523.

3. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD001155.

4. Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, et al. Etidronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD003376.

5. Maraka S, Kennel KA. Bisphosphonates for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. BMJ. 2015;351:h3783.

6. Balach T, Baldwin PC, Intravia J. Atypical femur fractures associated with diphosphonate use. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2015;23:550-557.

7. Porrino JA Jr, Kohl CA, Taljanovic M, et al. Diagnosis of proximal femoral insufficiency fractures in patients receiving bisphosphonate therapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:1061-1064.

8. Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Lane J, et al. Bisphosphonates and nonhealing femoral fractures: analysis of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) and international safety efforts: a systematic review from the Research on Adverse Drug Events And Reports (RADAR) project. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:297-307.

9. Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011;305:783-789.

10. Schilcher J, Michaëlsson K, Aspenberg P. Bisphosphonate use and atypical fractures of the femoral shaft. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1728-1737.

11. Gedmintas L, Solomon DH, Kim SC. Bisphosphonates and risk of subtrochanteric, femoral shaft, and atypical femur fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2013;28:1729-1737.

12. Weil YA, Rivkin G, Safran O, et al. The outcome of surgically treated femur fractures associated with long-term bisphosphonate use. J Trauma. 2011;71:186-190.

13. Khan AA, Leslie WD, Lentle B, et al. Atypical femoral fractures: a teaching perspective. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2015;66:102-107.

14. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al; National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2014;25:2359-2381.

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:356-364.

16. World Health Organization (WHO). 1994. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: report of a WHO study group. WHO Technical Report Series, Report No. 843. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland.

17. Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, et al. Development and use of FRAX in osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2010;21:S407-S413.

Bipolar disorder: Making the Dx, selecting the right Rx

THE CASE

A 23-year-old woman seeks medical attention at the request of her boyfriend because she’s been “miserable” for 3 weeks. In the examination room, she slouches in the chair and says her mood is low, her grades have dropped, and she no longer enjoys social gatherings or her other usual activities. She has no thoughts of suicide, no weight loss, and no somatic symptoms.

She says she is generally healthy, does not take any regular medications, and has never been pregnant. When asked about previous similar episodes, she admits to feeling this way about 3 times a year for one to 2 months at a time. She has tried different antidepressants, which haven’t helped much and have made her irritable and interfered with sleep.

When asked about mania or hypomania, she says there are short periods, roughly a couple of weeks 2 or 3 times a year, when she will get a lot of work done and can get by with little sleep. She has never gone on “spending sprees,” though, or indulged in any other unusual or dangerous behavior. And she has never been hospitalized for symptoms.

Bipolar disorders, over time, typically cause fluctuations in mood, activity, and energy level. If disorders go untreated, a patient’s behavior may cause considerable damage to relationships, finances, and reputations. And for some patients, the disorder can take the ultimate toll, resulting in death by suicide or accident.

Subtypes of bipolar disorder differ in the timing and severity of manic (or hypomanic) and depressive symptoms or episodes. Type I is the classic manic-depressive illness; type II is characterized by chronic treatment-resistant depression punctuated by hypomanic episodes; and cyclothymia leads to chronic fluctuations in mood. The diagnostic category “bipolar disorder not otherwise specified” applies to patients who meet some, but not all, of the criteria for other bipolar disorder subtypes.1

Prevalence. As with other mood symptoms or disorders, patients with bipolar disorder are often seen first in primary care due, in part, to barriers to obtaining psychiatric care or to avoidance of the perceived stigma in seeking such care.2 In a systematic review of patients who were interviewed randomly in primary care settings, 0.5% to 4.3% met criteria for bipolar disorder.3 The average age of onset for bipolar disorder is 15 to 19 years.4 In the United States, the prevalence of bipolar disorder type I is 1%; type II is 1.1%.3

The cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but familial predisposition, biopsychosocial factors, and environment all seem to play a role. Children of parents with bipolar disorder have a 4% to 15% chance of receiving the same diagnosis, compared with children of parents without bipolar disorder, whose risk is only as high as 2%.5,6

Clinical presentation varies

When patients with bipolar disorder are first seen in the office, their state may be depression, mania, hypomania, or even euthymia. Keep in mind that the first 3 aberrations may indicate other disorders, either

Verify a true depressive episode

Symptoms must last for 2 weeks and include anhedonia or depressed mood, as well as some combination of changes in sleep, increased feelings of guilt, poor concentration, changes in appetite, loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or suicidal thoughts.1

Know the criteria for mania

True mania is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy, and lasting at least one week for most of the day, nearly every day (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary).

During that time, the patient must also exhibit at least 3 or more of the following symptoms (not counting irritability, if present): 1

- distractibility,

- insomnia,

- grandiosity,

- flights of ideas,

- increased goal-directed activity or agitation,

- rapid/pressured speech, or

- reckless behaviors.

How hypomania differs from mania. The symptoms of hypomania are less severe than those of mania—eg, social functioning is less impaired or is even normal, and there is no need for hospitalization. Patients may feel they have been much more productive than usual or have needed less sleep to engage in daily activities. Hypomania may be present but not reported by patients who perceive nothing wrong.1,4

Rule out alternate diagnoses and apply DSM-5 criteria

There are no objective tests to confirm a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. If you suspect bipolar disorder, focus your clinical evaluation on ruling out competing mental health or medical diagnoses, and on determining whether the patient’s history meets criteria for a bipolar disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).1

Explore the patient’s psychiatric history (including hospitalizations, medications, and electroconvulsive therapy), general medical history, family history of psychiatric disorders (including suicide), and social history (including substance use and abuse). And carefully observe mental status. Confirming a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may take multiple visits, but strongly suggestive symptoms could warrant empirical treatment.

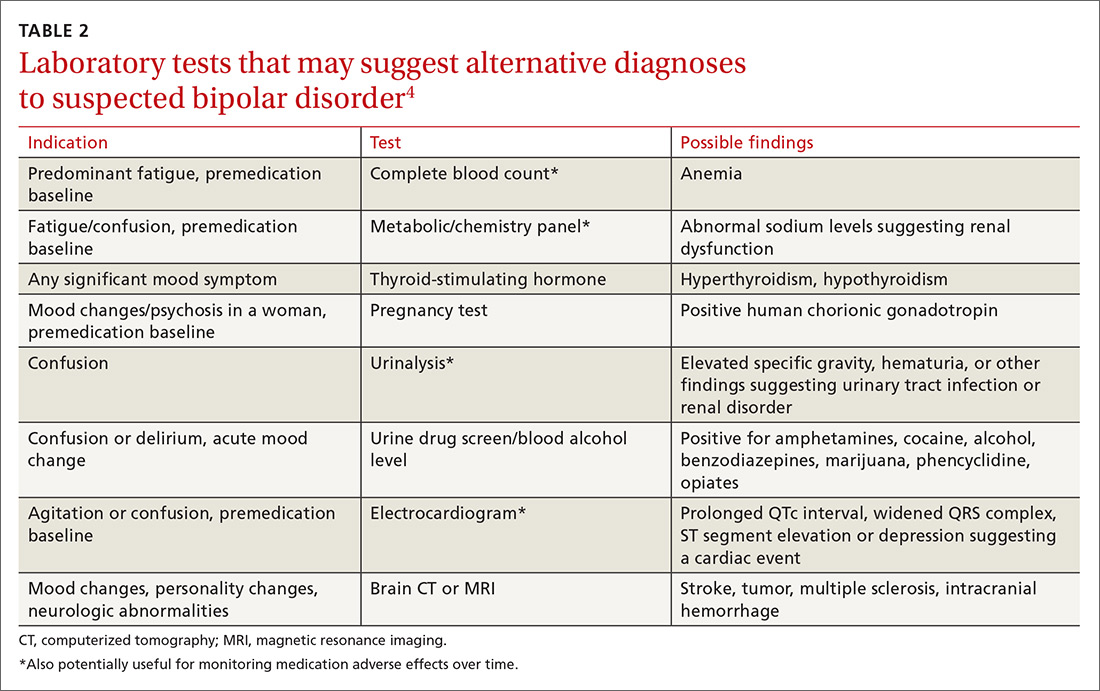

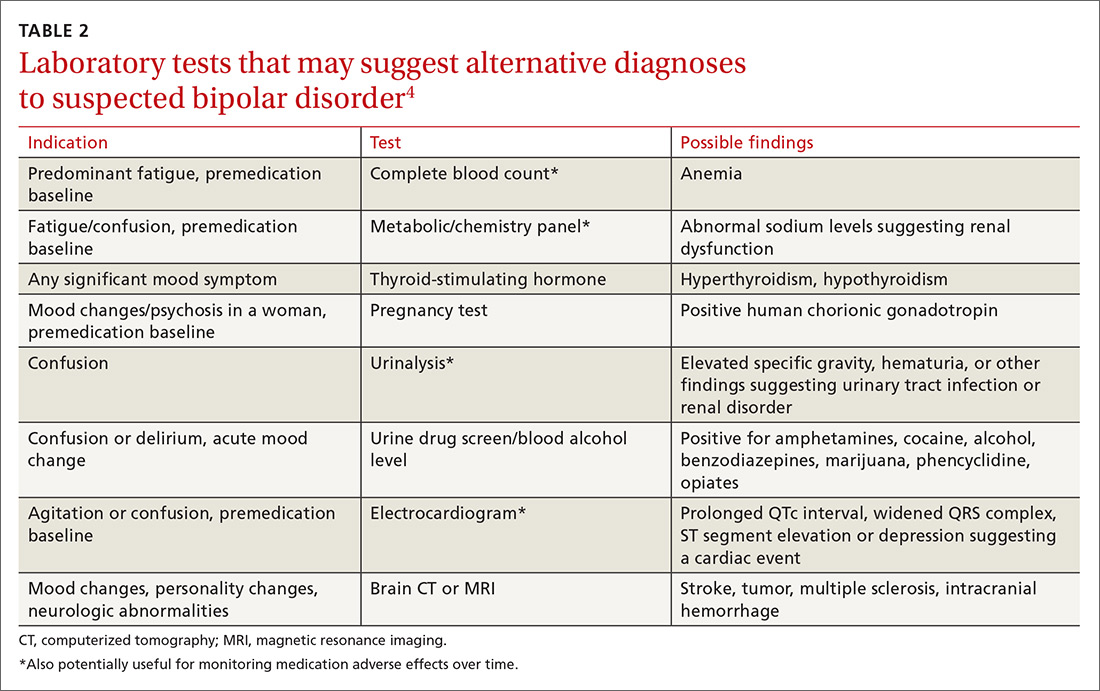

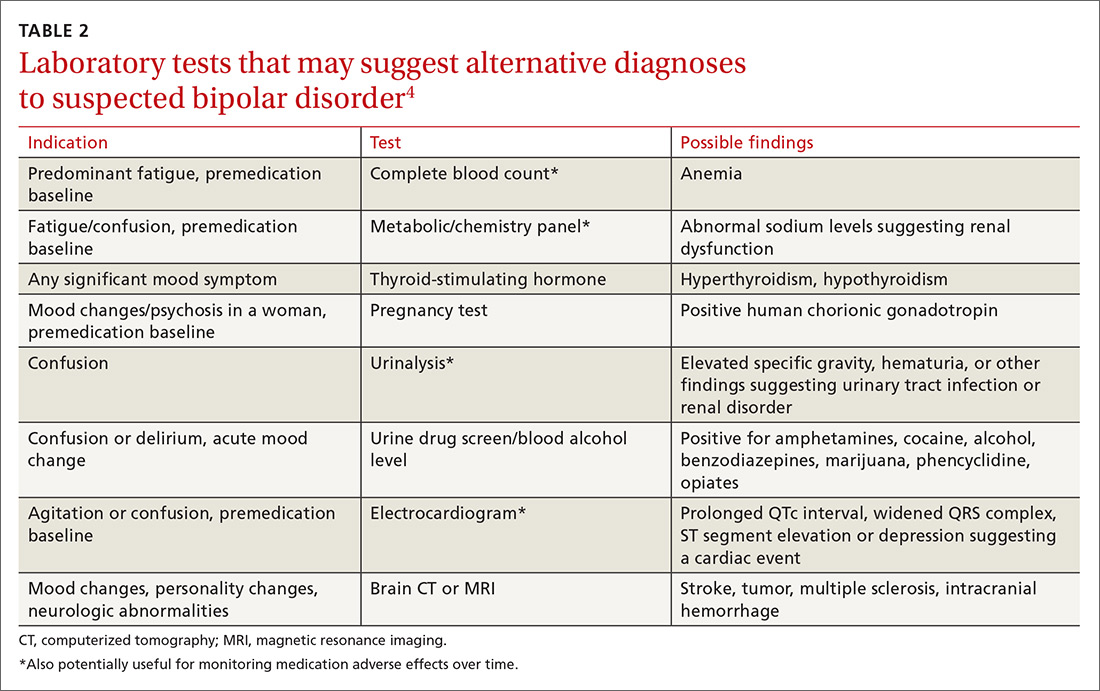

Helpful scales. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218) and the Beck Depression Inventory (http://www.hr.ucdavis.edu/asap/pdf_files/Beck_Depression_Inventory.pdf) are useful for ruling out depressive disorders. Other scales are available, but they cannot confirm bipolar disorder. Laboratory testing selected according to patient symptoms (TABLE 24) can help rule out alternative diagnoses, but are also useful for establishing a baseline for medications.

Pharmacologic treatment: Match agents to symptoms

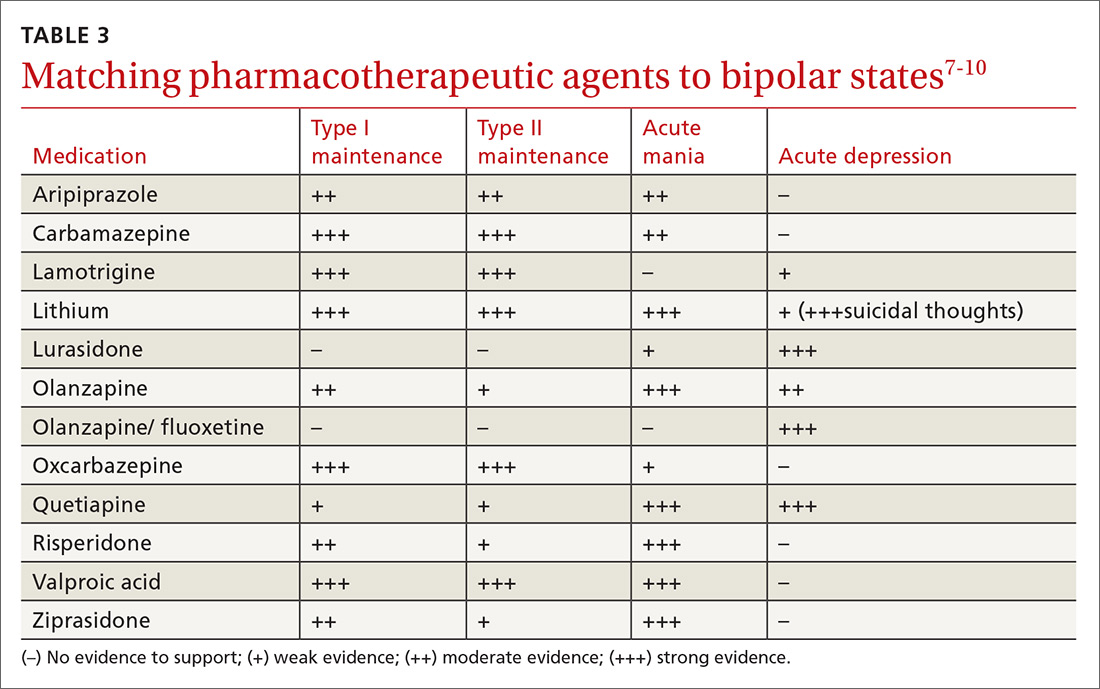

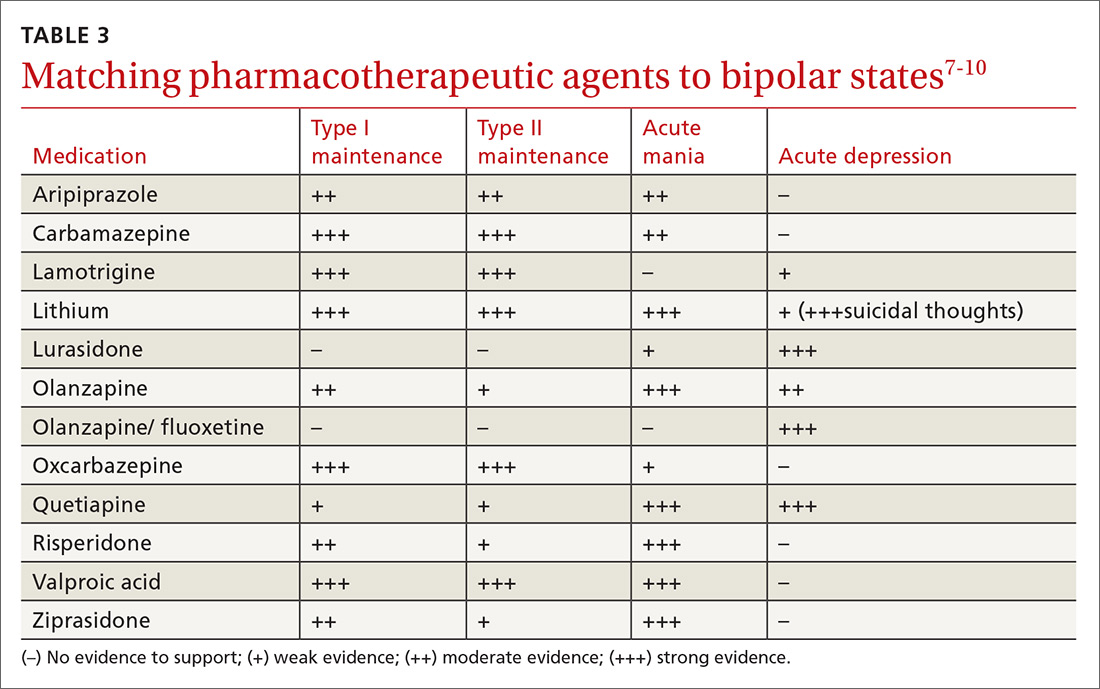

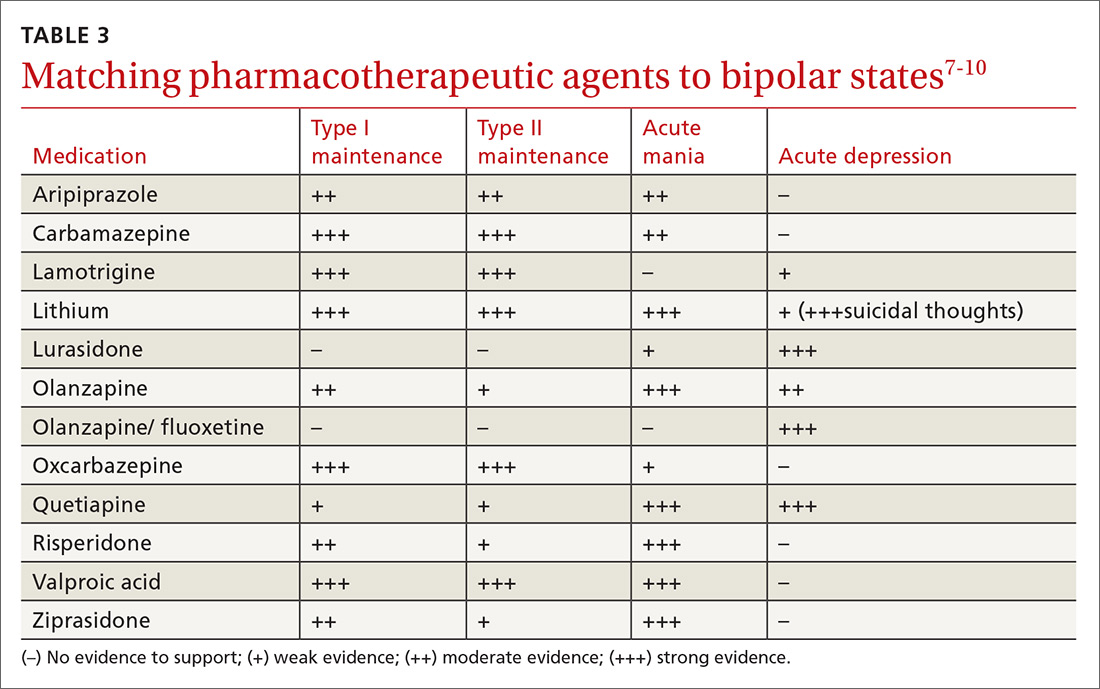

When treating bipolar disorder, choose a drug that targets a patient’s specific symptoms (TABLE 3).7-10 In primary care, the most commonly-used treatments for bipolar disorder type II are lamotrigine, valproic acid, and lithium.11

When to refer

Many cases of bipolar disorder type II can be managed successfully in a primary care practice, as can some cases of stable bipolar disorder type I. Psychiatric consultation may be most beneficial if the patient has recently attempted suicide or has suicidal ideation, has symptoms refractory to treatment, has poor medication adherence, or is misusing medications.

Even when patients are co-managed with psychiatric consultation, family physicians often ensure patients’ medication adherence, help patients understand their illness, manage overall health-related behaviors (including getting sufficient sleep), and make sure patients follow up as needed with their psychiatrist. Often, once patients have achieved equilibrium on mood-stabilizing (or other) medications, you can manage them and monitor medications with further consultation only as needed for clinical deterioration or other issues. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be useful as adjunctive treatment, particularly when patients are in active treatment.12

› CASE

This case is typical for many patients with depressed mood. A few key features in the patient’s history suggest bipolar disorder type II:

- depression that has been refractory to treatment

- multiple failed drug treatments, with mood-related adverse effects

- hypomania perceived as a “productive time,” and not as a problem

- absence of overt manic symptoms.

The patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type II with current depressed mood and no evidence of acute mania. She was started on valproic acid 250 mg po tid. She reported an initial improvement in mood but stopped the medication after one month because it caused intolerable drowsiness. She was then prescribed lamotrigine progressing gradually in 2-week intervals from 25 mg to 100 mg daily. She tolerated the medication well, and after 3 months of treatment, her mood symptoms improved and she had no further episodes of depressed mood.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Jason Wells, MD, Department of Family and Geriatric Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 201 Abraham Flexner Way, Suite 690, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected].

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, O’Donnell AN, et al. Integrated bipolar disorder management in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:687-695.

3. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

4. Malhi GS, Adams D, Lampe L, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for bipolar disorder. Acta Pscyhiatr Scand. 2009:119(Suppl 439):27-46.

5. Abell S, Ey J. Bipolar Disorder. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:693-694.

6. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders of school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287-296.

7. Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, et al. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

8. De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, et al. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:603-617.

9. Gitlin M, Frye MA. Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2012:14(Suppl 2):51-65.

10. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

11. Ostacher M, Tandon R, Suppes T. Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults with Bipolar Disorder: a novel, practical, patient-centered guide for clinicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:920-926.

12. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

THE CASE

A 23-year-old woman seeks medical attention at the request of her boyfriend because she’s been “miserable” for 3 weeks. In the examination room, she slouches in the chair and says her mood is low, her grades have dropped, and she no longer enjoys social gatherings or her other usual activities. She has no thoughts of suicide, no weight loss, and no somatic symptoms.

She says she is generally healthy, does not take any regular medications, and has never been pregnant. When asked about previous similar episodes, she admits to feeling this way about 3 times a year for one to 2 months at a time. She has tried different antidepressants, which haven’t helped much and have made her irritable and interfered with sleep.

When asked about mania or hypomania, she says there are short periods, roughly a couple of weeks 2 or 3 times a year, when she will get a lot of work done and can get by with little sleep. She has never gone on “spending sprees,” though, or indulged in any other unusual or dangerous behavior. And she has never been hospitalized for symptoms.

Bipolar disorders, over time, typically cause fluctuations in mood, activity, and energy level. If disorders go untreated, a patient’s behavior may cause considerable damage to relationships, finances, and reputations. And for some patients, the disorder can take the ultimate toll, resulting in death by suicide or accident.

Subtypes of bipolar disorder differ in the timing and severity of manic (or hypomanic) and depressive symptoms or episodes. Type I is the classic manic-depressive illness; type II is characterized by chronic treatment-resistant depression punctuated by hypomanic episodes; and cyclothymia leads to chronic fluctuations in mood. The diagnostic category “bipolar disorder not otherwise specified” applies to patients who meet some, but not all, of the criteria for other bipolar disorder subtypes.1

Prevalence. As with other mood symptoms or disorders, patients with bipolar disorder are often seen first in primary care due, in part, to barriers to obtaining psychiatric care or to avoidance of the perceived stigma in seeking such care.2 In a systematic review of patients who were interviewed randomly in primary care settings, 0.5% to 4.3% met criteria for bipolar disorder.3 The average age of onset for bipolar disorder is 15 to 19 years.4 In the United States, the prevalence of bipolar disorder type I is 1%; type II is 1.1%.3

The cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but familial predisposition, biopsychosocial factors, and environment all seem to play a role. Children of parents with bipolar disorder have a 4% to 15% chance of receiving the same diagnosis, compared with children of parents without bipolar disorder, whose risk is only as high as 2%.5,6

Clinical presentation varies

When patients with bipolar disorder are first seen in the office, their state may be depression, mania, hypomania, or even euthymia. Keep in mind that the first 3 aberrations may indicate other disorders, either

Verify a true depressive episode

Symptoms must last for 2 weeks and include anhedonia or depressed mood, as well as some combination of changes in sleep, increased feelings of guilt, poor concentration, changes in appetite, loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or suicidal thoughts.1

Know the criteria for mania

True mania is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy, and lasting at least one week for most of the day, nearly every day (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary).

During that time, the patient must also exhibit at least 3 or more of the following symptoms (not counting irritability, if present): 1

- distractibility,

- insomnia,

- grandiosity,

- flights of ideas,

- increased goal-directed activity or agitation,

- rapid/pressured speech, or

- reckless behaviors.

How hypomania differs from mania. The symptoms of hypomania are less severe than those of mania—eg, social functioning is less impaired or is even normal, and there is no need for hospitalization. Patients may feel they have been much more productive than usual or have needed less sleep to engage in daily activities. Hypomania may be present but not reported by patients who perceive nothing wrong.1,4

Rule out alternate diagnoses and apply DSM-5 criteria

There are no objective tests to confirm a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. If you suspect bipolar disorder, focus your clinical evaluation on ruling out competing mental health or medical diagnoses, and on determining whether the patient’s history meets criteria for a bipolar disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).1

Explore the patient’s psychiatric history (including hospitalizations, medications, and electroconvulsive therapy), general medical history, family history of psychiatric disorders (including suicide), and social history (including substance use and abuse). And carefully observe mental status. Confirming a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may take multiple visits, but strongly suggestive symptoms could warrant empirical treatment.

Helpful scales. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218) and the Beck Depression Inventory (http://www.hr.ucdavis.edu/asap/pdf_files/Beck_Depression_Inventory.pdf) are useful for ruling out depressive disorders. Other scales are available, but they cannot confirm bipolar disorder. Laboratory testing selected according to patient symptoms (TABLE 24) can help rule out alternative diagnoses, but are also useful for establishing a baseline for medications.

Pharmacologic treatment: Match agents to symptoms

When treating bipolar disorder, choose a drug that targets a patient’s specific symptoms (TABLE 3).7-10 In primary care, the most commonly-used treatments for bipolar disorder type II are lamotrigine, valproic acid, and lithium.11

When to refer

Many cases of bipolar disorder type II can be managed successfully in a primary care practice, as can some cases of stable bipolar disorder type I. Psychiatric consultation may be most beneficial if the patient has recently attempted suicide or has suicidal ideation, has symptoms refractory to treatment, has poor medication adherence, or is misusing medications.

Even when patients are co-managed with psychiatric consultation, family physicians often ensure patients’ medication adherence, help patients understand their illness, manage overall health-related behaviors (including getting sufficient sleep), and make sure patients follow up as needed with their psychiatrist. Often, once patients have achieved equilibrium on mood-stabilizing (or other) medications, you can manage them and monitor medications with further consultation only as needed for clinical deterioration or other issues. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be useful as adjunctive treatment, particularly when patients are in active treatment.12

› CASE

This case is typical for many patients with depressed mood. A few key features in the patient’s history suggest bipolar disorder type II:

- depression that has been refractory to treatment

- multiple failed drug treatments, with mood-related adverse effects

- hypomania perceived as a “productive time,” and not as a problem

- absence of overt manic symptoms.

The patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type II with current depressed mood and no evidence of acute mania. She was started on valproic acid 250 mg po tid. She reported an initial improvement in mood but stopped the medication after one month because it caused intolerable drowsiness. She was then prescribed lamotrigine progressing gradually in 2-week intervals from 25 mg to 100 mg daily. She tolerated the medication well, and after 3 months of treatment, her mood symptoms improved and she had no further episodes of depressed mood.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Jason Wells, MD, Department of Family and Geriatric Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 201 Abraham Flexner Way, Suite 690, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected].

THE CASE

A 23-year-old woman seeks medical attention at the request of her boyfriend because she’s been “miserable” for 3 weeks. In the examination room, she slouches in the chair and says her mood is low, her grades have dropped, and she no longer enjoys social gatherings or her other usual activities. She has no thoughts of suicide, no weight loss, and no somatic symptoms.

She says she is generally healthy, does not take any regular medications, and has never been pregnant. When asked about previous similar episodes, she admits to feeling this way about 3 times a year for one to 2 months at a time. She has tried different antidepressants, which haven’t helped much and have made her irritable and interfered with sleep.

When asked about mania or hypomania, she says there are short periods, roughly a couple of weeks 2 or 3 times a year, when she will get a lot of work done and can get by with little sleep. She has never gone on “spending sprees,” though, or indulged in any other unusual or dangerous behavior. And she has never been hospitalized for symptoms.

Bipolar disorders, over time, typically cause fluctuations in mood, activity, and energy level. If disorders go untreated, a patient’s behavior may cause considerable damage to relationships, finances, and reputations. And for some patients, the disorder can take the ultimate toll, resulting in death by suicide or accident.

Subtypes of bipolar disorder differ in the timing and severity of manic (or hypomanic) and depressive symptoms or episodes. Type I is the classic manic-depressive illness; type II is characterized by chronic treatment-resistant depression punctuated by hypomanic episodes; and cyclothymia leads to chronic fluctuations in mood. The diagnostic category “bipolar disorder not otherwise specified” applies to patients who meet some, but not all, of the criteria for other bipolar disorder subtypes.1

Prevalence. As with other mood symptoms or disorders, patients with bipolar disorder are often seen first in primary care due, in part, to barriers to obtaining psychiatric care or to avoidance of the perceived stigma in seeking such care.2 In a systematic review of patients who were interviewed randomly in primary care settings, 0.5% to 4.3% met criteria for bipolar disorder.3 The average age of onset for bipolar disorder is 15 to 19 years.4 In the United States, the prevalence of bipolar disorder type I is 1%; type II is 1.1%.3

The cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but familial predisposition, biopsychosocial factors, and environment all seem to play a role. Children of parents with bipolar disorder have a 4% to 15% chance of receiving the same diagnosis, compared with children of parents without bipolar disorder, whose risk is only as high as 2%.5,6

Clinical presentation varies

When patients with bipolar disorder are first seen in the office, their state may be depression, mania, hypomania, or even euthymia. Keep in mind that the first 3 aberrations may indicate other disorders, either

Verify a true depressive episode

Symptoms must last for 2 weeks and include anhedonia or depressed mood, as well as some combination of changes in sleep, increased feelings of guilt, poor concentration, changes in appetite, loss of energy, psychomotor agitation or retardation, or suicidal thoughts.1

Know the criteria for mania

True mania is a distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood, accompanied by abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy, and lasting at least one week for most of the day, nearly every day (or any duration if hospitalization is necessary).

During that time, the patient must also exhibit at least 3 or more of the following symptoms (not counting irritability, if present): 1

- distractibility,

- insomnia,

- grandiosity,

- flights of ideas,

- increased goal-directed activity or agitation,

- rapid/pressured speech, or

- reckless behaviors.

How hypomania differs from mania. The symptoms of hypomania are less severe than those of mania—eg, social functioning is less impaired or is even normal, and there is no need for hospitalization. Patients may feel they have been much more productive than usual or have needed less sleep to engage in daily activities. Hypomania may be present but not reported by patients who perceive nothing wrong.1,4

Rule out alternate diagnoses and apply DSM-5 criteria

There are no objective tests to confirm a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. If you suspect bipolar disorder, focus your clinical evaluation on ruling out competing mental health or medical diagnoses, and on determining whether the patient’s history meets criteria for a bipolar disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).1

Explore the patient’s psychiatric history (including hospitalizations, medications, and electroconvulsive therapy), general medical history, family history of psychiatric disorders (including suicide), and social history (including substance use and abuse). And carefully observe mental status. Confirming a diagnosis of bipolar disorder may take multiple visits, but strongly suggestive symptoms could warrant empirical treatment.

Helpful scales. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/218) and the Beck Depression Inventory (http://www.hr.ucdavis.edu/asap/pdf_files/Beck_Depression_Inventory.pdf) are useful for ruling out depressive disorders. Other scales are available, but they cannot confirm bipolar disorder. Laboratory testing selected according to patient symptoms (TABLE 24) can help rule out alternative diagnoses, but are also useful for establishing a baseline for medications.

Pharmacologic treatment: Match agents to symptoms

When treating bipolar disorder, choose a drug that targets a patient’s specific symptoms (TABLE 3).7-10 In primary care, the most commonly-used treatments for bipolar disorder type II are lamotrigine, valproic acid, and lithium.11

When to refer

Many cases of bipolar disorder type II can be managed successfully in a primary care practice, as can some cases of stable bipolar disorder type I. Psychiatric consultation may be most beneficial if the patient has recently attempted suicide or has suicidal ideation, has symptoms refractory to treatment, has poor medication adherence, or is misusing medications.

Even when patients are co-managed with psychiatric consultation, family physicians often ensure patients’ medication adherence, help patients understand their illness, manage overall health-related behaviors (including getting sufficient sleep), and make sure patients follow up as needed with their psychiatrist. Often, once patients have achieved equilibrium on mood-stabilizing (or other) medications, you can manage them and monitor medications with further consultation only as needed for clinical deterioration or other issues. Cognitive behavioral therapy may be useful as adjunctive treatment, particularly when patients are in active treatment.12

› CASE

This case is typical for many patients with depressed mood. A few key features in the patient’s history suggest bipolar disorder type II:

- depression that has been refractory to treatment

- multiple failed drug treatments, with mood-related adverse effects

- hypomania perceived as a “productive time,” and not as a problem

- absence of overt manic symptoms.

The patient was given a diagnosis of bipolar disorder type II with current depressed mood and no evidence of acute mania. She was started on valproic acid 250 mg po tid. She reported an initial improvement in mood but stopped the medication after one month because it caused intolerable drowsiness. She was then prescribed lamotrigine progressing gradually in 2-week intervals from 25 mg to 100 mg daily. She tolerated the medication well, and after 3 months of treatment, her mood symptoms improved and she had no further episodes of depressed mood.

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Jason Wells, MD, Department of Family and Geriatric Medicine, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 201 Abraham Flexner Way, Suite 690, Louisville, KY 40202; [email protected].

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, O’Donnell AN, et al. Integrated bipolar disorder management in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:687-695.

3. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

4. Malhi GS, Adams D, Lampe L, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for bipolar disorder. Acta Pscyhiatr Scand. 2009:119(Suppl 439):27-46.

5. Abell S, Ey J. Bipolar Disorder. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:693-694.

6. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders of school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287-296.

7. Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, et al. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

8. De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, et al. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:603-617.

9. Gitlin M, Frye MA. Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2012:14(Suppl 2):51-65.

10. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

11. Ostacher M, Tandon R, Suppes T. Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults with Bipolar Disorder: a novel, practical, patient-centered guide for clinicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:920-926.

12. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, O’Donnell AN, et al. Integrated bipolar disorder management in primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14:687-695.

3. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

4. Malhi GS, Adams D, Lampe L, et al. Clinical practice recommendations for bipolar disorder. Acta Pscyhiatr Scand. 2009:119(Suppl 439):27-46.

5. Abell S, Ey J. Bipolar Disorder. Clin Pediatr. 2009;48:693-694.

6. Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, et al. Lifetime psychiatric disorders of school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:287-296.

7. Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, et al. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;346:f3646.

8. De Fruyt J, Deschepper E, Audenaert K, et al. Second generation antipsychotics in the treatment of bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26:603-617.

9. Gitlin M, Frye MA. Maintenance therapies in bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2012:14(Suppl 2):51-65.

10. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

11. Ostacher M, Tandon R, Suppes T. Florida Best Practice Psychotherapeutic Medication Guidelines for Adults with Bipolar Disorder: a novel, practical, patient-centered guide for clinicians. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77:920-926.

12. Szentagotai A, David D. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy in bipolar disorder: a quantitative meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:66-72.

These 3 tools can help you streamline management of IBS

CASE › Amber S,* a 33-year-old woman who works on the production line at a bread factory, sought care at my health center with a several month history of non-bloody diarrhea that was increasing in frequency and urgency and was accompanied by painful abdominal bloating and cramping. She said that these symptoms were negatively impacting her interpersonal relationships, as well as her productivity at work. She reported that “almost everything” she ate upset her stomach and “goes right through her,” including fruits, vegetables, and meat, as well as greasy fast food. She had researched her symptoms on the Internet and was worried that she might have something serious like inflammatory bowel disease or cancer.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) that negatively impacts the quality of life (QOL) of millions of people worldwide.1 In fact, one study of 179 people with IBS found that 76% of survey respondents reported some degree of IBS-related impairment in at least 5 domains of daily life: daily activities, comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, symptom severity, QOL, and symptom-specific cognitive affective factors related to IBS.2

Estimating prevalence and incidence is a formidable challenge given various diagnostic criteria, the influence of population selection, inclusion or exclusion of non-GI comorbidities, and various cultural influences.3 That said, it’s estimated that IBS impacts approximately 11% of the world’s population, and approximately 30% of these individuals seek treatment.1,4 While there are no significant differences in GI symptoms between those who consult physicians and those who do not, those who do seek treatment report higher pain scores, greater levels of anxiety, and a greater reduction in QOL.5

All ages affected. IBS has been reported in patients of all ages, including children and the elderly, with no definable difference reported in the frequency of subtypes (diarrhea- or constipation-predominant).

This article reviews the latest explanations, diagnostic criteria, and treatment guidelines for this challenging condition so that you can offer your patients confident care without needless testing or referral.

[polldaddy:9755564]

A lack of consensus among practicing physicians

Historically, IBS has been regarded by many primary care physicians (PCPs) as a diagnosis of exclusion. Lab tests would be ordered, nothing significant would be found, and the patient would be referred to the gastroenterologist for a definitive diagnosis.

Perceptions and misconceptions about IBS continue to abound to this day. Many are neither completely right nor wrong partly because so many triggers for IBS exist and partly because of the heretofore lack of simple, standardized criteria to diagnose the condition. Other factors contributing to the confusion are that the diagnosis of IBS is purely symptom-based and that proposals of its pathophysiology have traditionally been complex.

For example, a 2006 survey-based study of PCPs and gastroenterologists found that PCPs were less likely than gastroenterologists to believe that IBS was related to prior physical or sexual abuse, previous infection, or learned behavior, but were more likely to associate dietary factors or a linkable genetic etiology with IBS.6 Both sets of beliefs, however, may be considered correct.

Similarly, a 2009 qualitative study conducted in the Netherlands found that general practitioners (GPs) considered smoking, caffeine, diet, “hasty lifestyle,” and lack of exercise as potential triggers for IBS symptoms, while PCPs in the United Kingdom considered diet, infection, and travel to be possible triggers.7 Again, all play a role.

While GPs reported that patients should take responsibility for managing their IBS and for minimizing its impact on their daily lives, they admitted limited awareness of the extent to which IBS affected their patients’ daily living.7

A 2013 survey-based study in England determined that GPs understand the relationship between IBS and psychological symptoms including anxiety and stress, and posited that the majority of patients could be managed within primary care without referral for psychological interventions.8 Moreover, they reported that a dedicated risk assessment tool for patients with IBS would be helpful to stratify severity of disease. The study concluded that the reluctance of GPs to refer patients for evidence-based psychological treatments may prevent them from obtaining appropriate services and care.

Newer explanatory model shines light on IBS

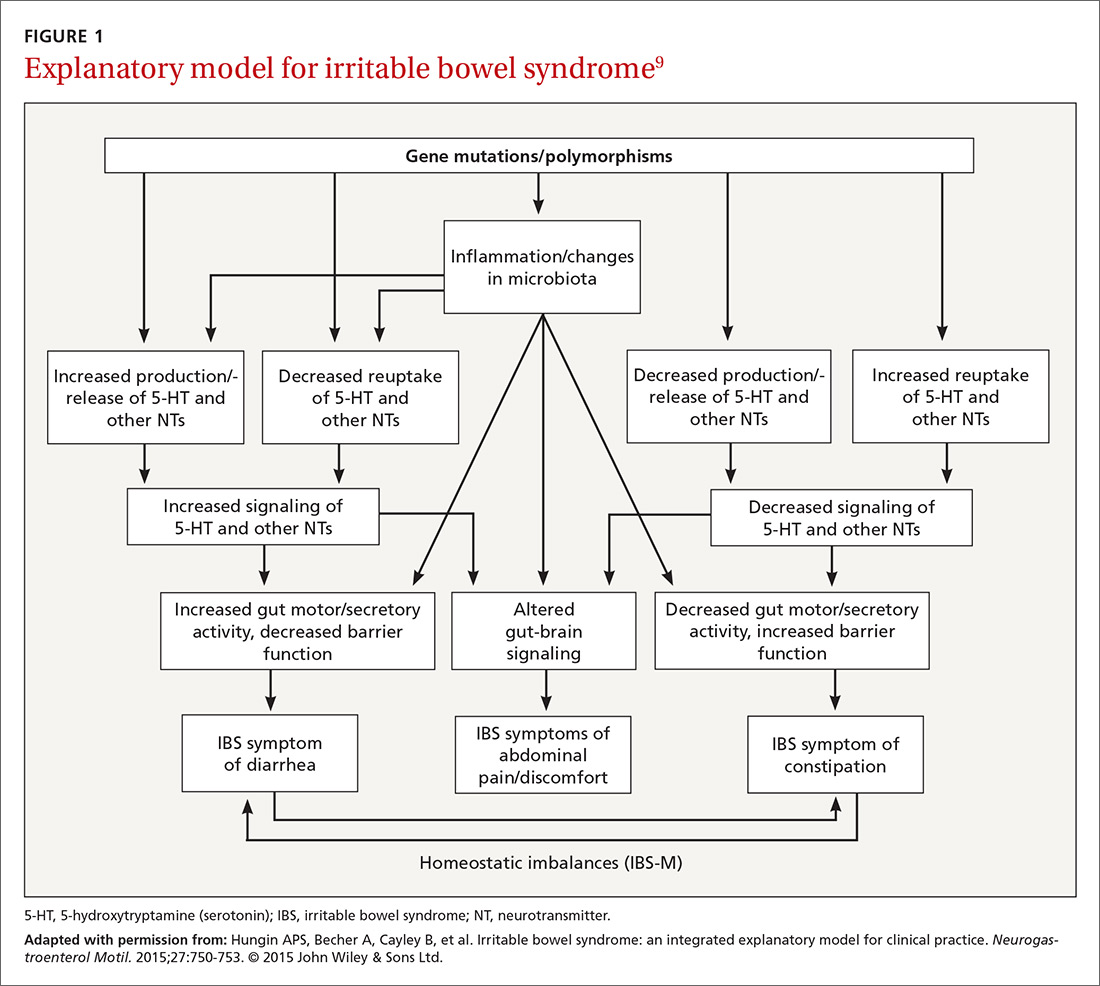

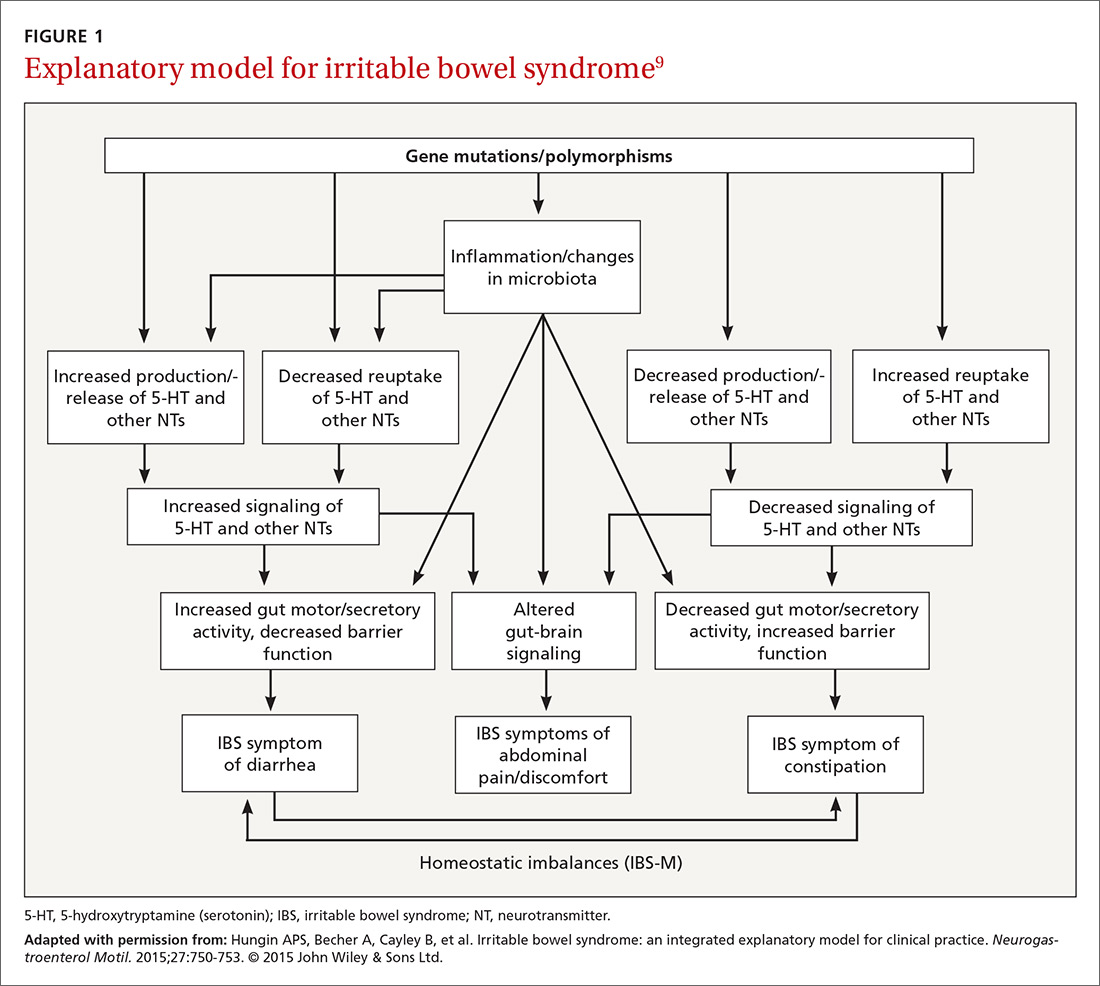

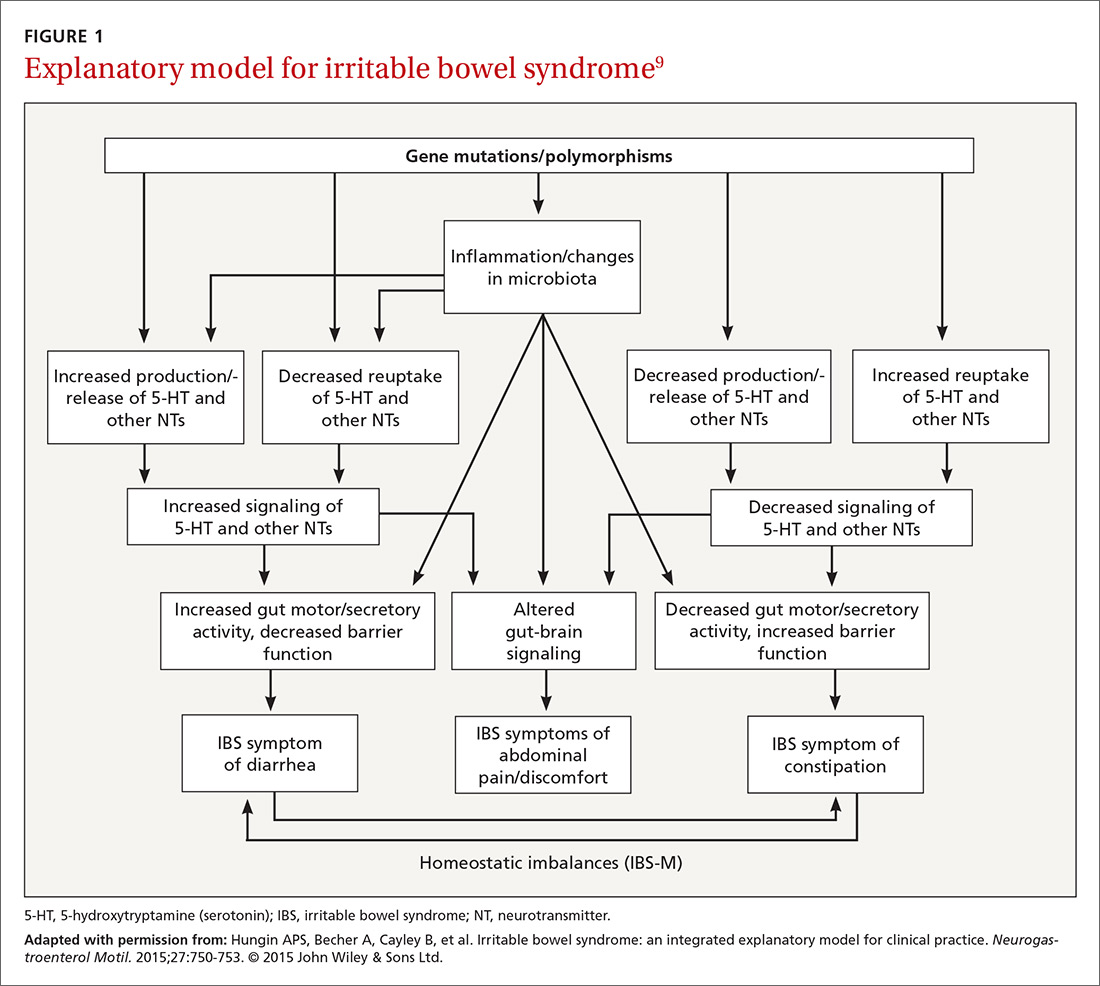

A newer explanation that is based on 3 main hypotheses is elucidating the true nature of IBS and providing a pragmatic model for the clinical setting (FIGURE 1).9 According to the model, IBS entails the following 3 elements, which combined lead to the symptoms of IBS:

- Altered or abnormal peripheral regulation of gut function (including sensory and secretory mechanisms)

- Altered brain-gut signaling (including visceral hypersensitivity)

- Psychological distress.

It is reasonable to consider that epigenetic changes may underlie the etiology and pathophysiology of IBS and could increase one’s susceptibility to developing the disorder. Additionally, it is presumed that IBS shares common pathophysiologic mechanisms, including visceral hypersensitivity, with other associated functional syndromes, such as functional dyspepsia.

New criteria make diagnosis on symptoms alone easier

In addition to a new explanatory model, clear criteria for diagnosing the disorder now exist, which should make it easier for PCPs to make the diagnosis without additional testing or referral. The 2016 Rome IV criteria3 provide guidelines for diagnosing the various subtypes of IBS including IBS-D (diarrhea predominant), IBS-C (constipation predominant), and IBS-M (mixed subtypes). A laboratory evaluation is really only needed for patients who fall outside the criteria or who have alarm symptoms, which include:

- age >50 years at onset of symptoms,

- new onset of constipation in the elderly,

- rectal bleeding,

- unexplained weight loss or anemia,

- family history of organic GI disease, and

- a palpable abdominal or rectal mass.

These symptoms should prompt referral to a gastroenterologist. Once alarm symptoms have been excluded, the diagnosis of IBS is based upon the presence of characteristic symptoms and changes in stool habits (FIGURE 23,10).

Patterns of migration. Over time, patients may migrate between subtypes, most commonly from IBS-C or IBS-D to IBS-M; switching between IBS-C and IBS-D occurs less commonly.11 Patients who meet criteria for IBS but whose bowel habits and symptoms cannot be grouped into any of these 3 categories are considered to have IBS unclassified. The Bristol Stool Form Scale (available at: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-communication-programs/bowel-control-awareness-campaign/Documents/Bristol_Stool_Form_Scale_508.pdf) should be used to gauge and track stool consistency.

A novel diagnostic test for IBS has been validated for differentiating patients with IBS-D from those with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).12 The test focused on the beliefs that cytolethal distending toxin B (CdtB) is produced by bacteria that cause acute viral gastroenteritis (eg, norovirus, rotavirus), and that host antibodies to CdtB cross-react with the protein vinculin in the host gut, producing an “IBS-like phenotype.”

In a 2015 large-scale multicenter trial, both anti-CdtB and anti-vinculin antibodies were found to be significantly elevated in subjects with IBS-D compared to non-IBS subjects,12 providing evidence to support the long-held belief that viral gastroenteritis is often at the root of IBS.

Treatment aims to decrease symptoms and improve QOL

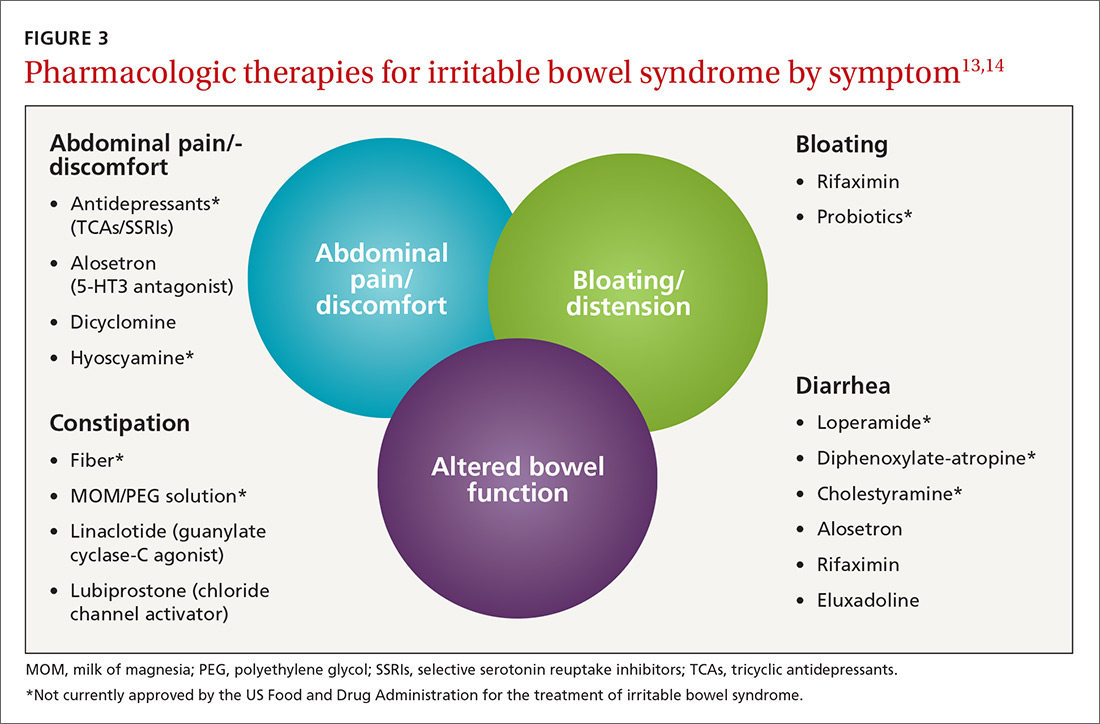

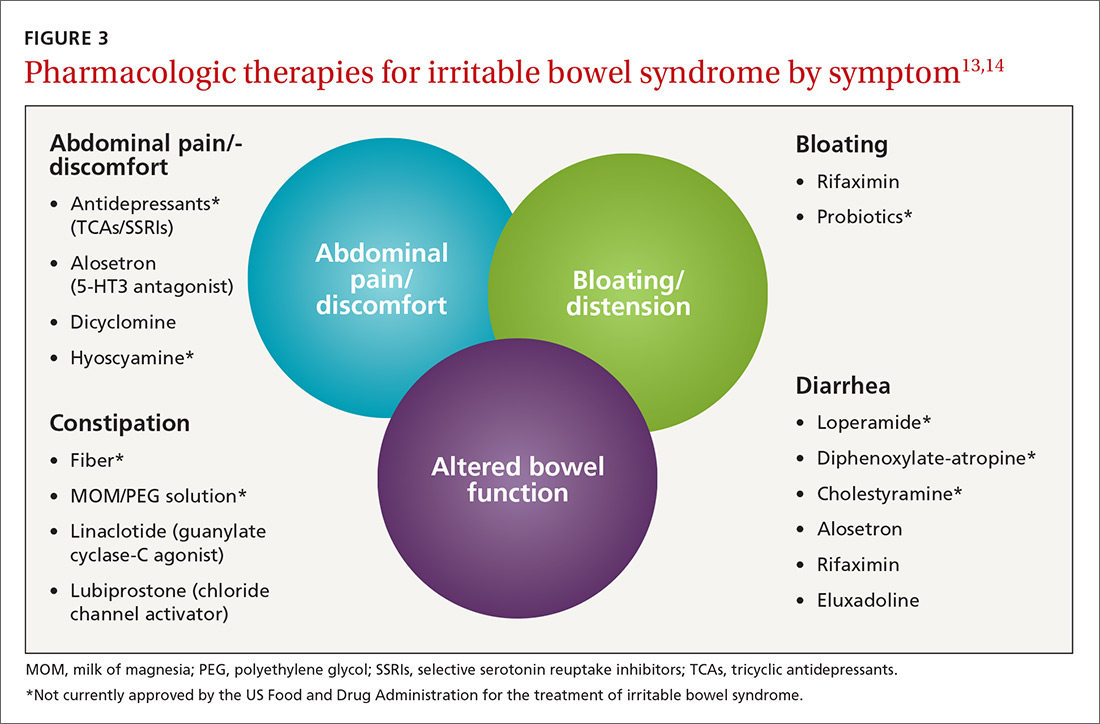

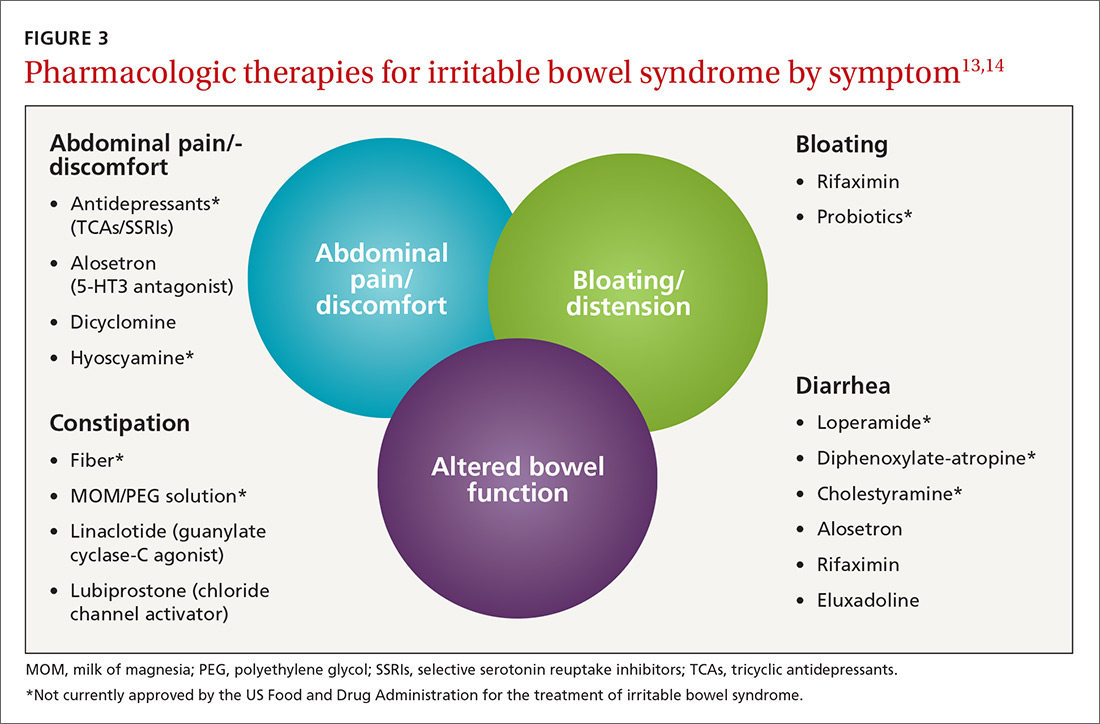

Treatment of IBS is directed at decreasing symptoms of abdominal pain and discomfort, bloating, diarrhea, and constipation while improving QOL. Therapeutic options for treatment of each symptom are listed in FIGURE 3

Current evidence-based pharmacologic guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) can be found at: https://www.guideline.gov/summaries/summary/49122?osrc=12. Figure 313,14 provides a few additional options not included in the AGA guidelines and presents the information in a simple schematic.

Pharmacologic therapies for IBS-D

Eluxadoline is a novel mixed mu opioid receptor agonist and delta opioid receptor antagonist developed for the treatment of IBS-D. It normalizes GI transit and defecation under conditions of environmental stress or post-inflammatory altered GI function.15 A 2016 study involving almost 2500 patients found that eluxadoline was significantly better than placebo at decreasing abdominal pain and improving stool consistency on the same day for at least half of a 26-week period.13 The most common adverse effects were nausea, constipation, and abdominal pain. Pancreatitis occurred rarely.

Rifaximin. Because GI flora play a central role in the pathophysiology of IBS, researchers have found that rifaximin, a minimally absorbed antibiotic, is a potentially important player in treatment. Two double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (TARGET 1 and TARGET 2) found that after 4 weeks of treatment, patients experienced significant improvement in global IBS symptoms including bloating, abdominal pain, and stool consistency on rifaximin vs placebo (40.7% vs 31.7%; P<.001 in the 2 studies combined).16 The incidence of adverse effects (headache, upper respiratory infection, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and urinary tract infection) was comparable to that with placebo.

Alosetron. Research has shown this selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist to improve all IBS QOL measures, restriction of daily activities, and patient satisfaction significantly more than placebo in women.17 While initial use of alosetron in 2000 was widespread, the rare serious adverse event of ischemic colitis led to its withdrawal from the US market within a few months.18 Alosetron returned to the market in 2002 with restricted marketing (to treat only women with severe diarrhea-predominant IBS). (See Lotronex [alosetron hydrochloride] full prescribing information available at: https://lotronex.com/hcp/index.html.) Data from a 9-year risk management program subsequently found a cumulative incidence rate for ischemic colitis of 1.03 cases per 1000 patient/years.19

Other possible options include various antidepressants (tricyclics such as amitriptyline, imipramine, and nortriptyline; or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] such as citalopram, fluoxetine, and paroxetine) and antispasmodics such as dicyclomine and hyoscyamine.

Pharmacologic therapies for IBS-C

Linaclotide is a guanylate cyclase-C agonist with an indication for treatment of IBS-C. A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled trial found that the percentage of patients who experienced a decrease in abdominal pain was nearly 25%, with statistically significant improvements in bloating, straining, and stool consistency over a 26-week period.20 In a report on 2 phase 3 trials, researchers found that linaclotide improved global symptom scores and significantly decreased abdominal bloating and fullness, pain, cramping, and discomfort vs placebo. Diarrhea was the most commonly reported adverse event in patients with severe abdominal symptoms (18.8%-21%).21

Lubiprostone is a prostaglandin E1 analogue that activates type-2-chloride channels on the apical membrane of epithelial cells in the intestine. In a combined analysis of 2 phase 3 randomized trials, lubiprostone was administered twice daily for 12 weeks vs placebo and patients were asked to describe how they felt after the trial period. Survey responders reported significant improvements in global IBS-C symptoms (17.9% vs 10.1%; P=.001).22 A meta-analysis of studies on lubiprostone found that diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain were the most common adverse effects, but their occurrence was not that much greater than with placebo.23

Diet and probiotics can play a significant role

The role of dietary components in the treatment of IBS is gaining increasing attention. Such components can have a direct effect on gastric and intestinal motility, visceral sensation, immune activation, brain-gut interactions, and the microbiome. Current evidence suggests that targeted carbohydrate and gluten exclusion plays a favorable role in the treatment and symptomatic improvement of patients with IBS.24

A 2014 study conducted in Australia showed that a diet low in FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols), which is characterized by avoiding foods containing gluten and those that are high in fructose, reduced overall GI symptom scores (including scores involving abdominal bloating, pain, and flatus) in patients with IBS compared to those consuming a normal Australian diet.25 The International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders’ Web site provides a detailed guide to low FODMAP foods and can be found at: http://www.aboutibs.org/low-fodmap-diet.html.

Probiotics are now commonly used in the symptomatic treatment of many upper and lower GI disorders. While much anecdotal evidence exists to support their benefit, there is a paucity of large-scale and rigorous research to provide substantial outcomes-based evidence. The theory for their use is that they support regulation of the gut microbiome, which in turn improves the imbalance between the intestinal microbiome and a dysfunctional intestinal barrier.

A 2014 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving multispecies probiotics (a mixture of Bifidobacterium longum, B. bifidum, B. lactis, Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. rhamnosus, and Streptococcus thermophilus) found that patients who received probiotics had significantly reduced symptoms of IBS after 4 weeks compared with placebo, and modest improvement in abdominal pain and discomfort as well as bloating.26 One study involving 122 patients from 2011 found that B. bifidum MIMBb75 reduced the global assessment of IBS symptoms by -88 points (95% CI, -1.07 to -0.69) when compared with only -0.16 (95% CI, -.32 to 0.00) points in the placebo group (P<.0001).27 MIMBb75 also significantly improved the IBS symptoms of pain/discomfort, distension/bloating, urgency, and digestive disorder. And one randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 67 patients found that QOL scores improved two-fold when patients took Saccharomyces boulardii (15.4% vs 7.0%; P<.05).28

Dried plums or prunes have been used successfully for decades for the symptomatic treatment of constipation. A single-blinded, randomized, cross-over study compared prunes 50 g/d to psyllium fiber 11 g/d and found that prunes were more efficacious (P<.05) with spontaneous bowel movements and stool consistency scores.29

Peppermint oil has been studied as an alternative therapy for symptoms of IBS, but efficacy and tolerability are concerns. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with a minimum duration of 2 weeks found that compared with placebo, peppermint oil provided improvement in abdominal pain, bloating, and global symptoms, but some patients reported transient heartburn.30 A 4-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial sponsored by IM HealthScience found a novel oral formulation of triple-enteric-coated sustained-release peppermint oil microspheres caused less heartburn than was reported in the previous study, but still significantly improved abdominal symptoms and lessened pain on defecation and fecal urgency.31

CASE › Suspecting IBS-D, the FP ordered a complete blood count, tissue transglutaminase antibodies, and a stool culture, all of which were unremarkable. Ms. S has been trying to follow a low FODMAP diet and has been taking some over-the-counter probiotics with only minimal relief of abdominal bloating and cramping and no improvement in stool consistency. Her FP started her on eluxadoline 100 mg twice daily with food. After 12 weeks of therapy, she reports significant improvement in global IBS symptoms and nearly complete resolution of her diarrhea.

*Amber S is a real patient in my practice. Her name has been changed to protect her identity.

CORRESPONDENCE

Joel J. Heidelbaugh, MD, FAAFP, FACG, Ypsilanti Health Center, 200 Arnet Suite 200, Ypsilanti, MI 48198; [email protected].

1. Lovell RM, Ford AC. Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:712-721.

2. Ballou S, Keefer L. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on daily functioning: characterizing and understanding daily consequences of IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2017;29. Epub 2016 Oct 25.

3. Heidelbaugh J, Hungin P, eds. ROME IV: Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders for Primary Care and Non-GI Clinicians. 1st ed. Raleigh, NC: Rome Foundation, Inc.; 2016.

4. Canavan C, West J, Card T. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:71-80.

5. Lee V, Guthrie E, Robinson A, et al. Functional bowel disorders in primary care: factors associated with health-related quality of life and doctor consultation. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64:129-138.

6. Lacy BE, Rosemore J, Robertson D, et al. Physicians’ attitudes and practices in the evaluation and treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:892-902.

7. Casiday RE, Hungin AP, Cornford CS, et al. GPs’ explanatory models for irritable bowel syndrome: a mismatch with patient models? J Fam Pract. 2009;26:34-39.

8. Harkness EF, Harrington V, Hinder S, et al. GP perspectives of irritable bowel syndrome—an accepted illness, but management deviates from guidelines: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2013;14:92.

9. Hungin AP, Becher A, Cayley B, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: an integrated explanatory model for clinical practice. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:750-753.

10. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterol. 2016;150:1393-1407.

11. Engsbro AL, Simren M, Bytzer P. Short-term stability of subtypes in the irritable bowel syndrome: prospective evaluation using the Rome III classification. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:350-359.

12. Pimentel M, Morales W, Rezaie A, et al. Development and validation of a biomarker for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome in human subjects. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126438.

13. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:242-253.

14. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1547-1561.

15. Fujita W, Gomes I, Dove LS, et al. Molecular characterization of eluxadoline as a potential ligand targeting mu-delta opioid receptor heteromers. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014;92:448-456.

16. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al, for the TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:22-32.

17. Cremonini F, Nicandro JP, Atkinson V, et al. Randomised clinical trial: alosetron improves quality of life and reduces restriction of daily activities in women with severe diarrhoea-predominant IBS. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:437-448.

18. Lewis JH. Alosetron for severe diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: safety and efficacy in perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;4:13-29.

19. Tong K, Nicandro JP, Shringarpure R, et al. A 9-year evaluation of temporal trends in alosetron postmarketing safety under the risk management program. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:344-357.

20. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: a 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1702-1712.

21. Rao SS, Quigley EM, Shiff SJ, et al. Effect of linaclotide on severe abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:616-623.

22. Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome—results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:329-341.

23. Lacy BE, Chey WD. Lubiprostone: chronic constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:143-152.

24. Spencer M, Chey WD, Eswaran S. Dietary Renaissance in IBS: has food replaced medications as a primary treatment strategy? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:424-440.

25. Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, et al. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:67-75.

26. Yoon JS, Sohn W, Lee OY, et al. Effect of multispecies probiotics on irritable bowel syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:52-59.

27. Guglielmetti S, Mora D, Gschwender M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Bifidobacterium bifidum MIMBb75 significantly alleviates irritable bowel syndrome and improves quality of life—a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1123-1132.

28. Choi CH, Jo SY, Park HJ, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial of saccharomyces boulardii in irritable bowel syndrome: effect on quality of life. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:679-683.

29. Attaluri A, Donahoe R, Valestin J, et al. Randomised clinical trial: dried plums (prunes) vs. psyllium for constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:822-828.

30. Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG. Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:505-512.

31. Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:560-571.