User login

FDA approves sublingual immunotherapy for dust mite allergies

Odactra (Merck, Sharp & Dohme) had been approved in adults aged 18-65 years, with allergic rhinitis with or without conjunctivitis. The tablets offer an alternative to subcutaneous injections, the FDA said in a statement issued March 1.

The sublingual tablets are intended to be taken daily, year-round, and the first dose must be taken under physician supervision to monitor for adverse reactions, according to the FDA. As with other sublingual immunotherapies, patients using the tablets should be simultaneously prescribed autoinjectable epinephrine.

The approval was based on results from randomized trials enrolling about 2,500 patients in Europe and the United States, according to the FDA. Patients taking the tablets saw a 16%-18% reduction in symptoms across studies, compared with placebo. Clinical benefit may be delayed by 8-14 weeks after starting the therapy, the agency said. Common adverse reactions reported in the studies included nausea, itching of the ears and mouth, and swelling of the lips and tongue.

Odactra is the fourth sublingual immunotherapy to be approved in the United States since 2014. Other approved therapies target grass and ragweed allergies.

Odactra (Merck, Sharp & Dohme) had been approved in adults aged 18-65 years, with allergic rhinitis with or without conjunctivitis. The tablets offer an alternative to subcutaneous injections, the FDA said in a statement issued March 1.

The sublingual tablets are intended to be taken daily, year-round, and the first dose must be taken under physician supervision to monitor for adverse reactions, according to the FDA. As with other sublingual immunotherapies, patients using the tablets should be simultaneously prescribed autoinjectable epinephrine.

The approval was based on results from randomized trials enrolling about 2,500 patients in Europe and the United States, according to the FDA. Patients taking the tablets saw a 16%-18% reduction in symptoms across studies, compared with placebo. Clinical benefit may be delayed by 8-14 weeks after starting the therapy, the agency said. Common adverse reactions reported in the studies included nausea, itching of the ears and mouth, and swelling of the lips and tongue.

Odactra is the fourth sublingual immunotherapy to be approved in the United States since 2014. Other approved therapies target grass and ragweed allergies.

Odactra (Merck, Sharp & Dohme) had been approved in adults aged 18-65 years, with allergic rhinitis with or without conjunctivitis. The tablets offer an alternative to subcutaneous injections, the FDA said in a statement issued March 1.

The sublingual tablets are intended to be taken daily, year-round, and the first dose must be taken under physician supervision to monitor for adverse reactions, according to the FDA. As with other sublingual immunotherapies, patients using the tablets should be simultaneously prescribed autoinjectable epinephrine.

The approval was based on results from randomized trials enrolling about 2,500 patients in Europe and the United States, according to the FDA. Patients taking the tablets saw a 16%-18% reduction in symptoms across studies, compared with placebo. Clinical benefit may be delayed by 8-14 weeks after starting the therapy, the agency said. Common adverse reactions reported in the studies included nausea, itching of the ears and mouth, and swelling of the lips and tongue.

Odactra is the fourth sublingual immunotherapy to be approved in the United States since 2014. Other approved therapies target grass and ragweed allergies.

Use of IHC stains on rise in melanoma diagnosis

While there is little consensus on the ideal role of immunohistochemical (IHC) stains in the diagnosis of melanoma, their use increased dramatically over a 15-year period, according to results from a study.

Randie H. Kim, MD, PhD, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, of New York University, reviewed nearly 6,300 pathology reports from patients with melanomas, all referred (along with tissue samples) to their center from other institutions during 2001-2015. One or more IHC stains were used diagnostically in 871 cases during the study period, with use increasing from 5% of patients in 2001 to 25% in 2015 (P less than .0001). Usage increased gradually over time, although the number of stains used per case did not increase significantly (J Cutan Pathol. 2017 Mar;44[3]:221-7).

IHC stain use was associated with melanomas occurring on the head or neck (odds ratio = 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9), acral melanomas (OR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.1-2.0) and melanomas thicker than 4 mm (OR = 2.5; 95% CI 1.7-3.6). The most common stain used in the study was Melan-A/MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells), the most specific of the IHC markers available and the one “largely responsible for the increased incidence in overall immunostain use in our study,” the researchers wrote. “The perception that melanocytic markers, such as Melan-A, can more accurately stage melanomas, is a potential explanation for its increased usage over the duration of the study period.”

The higher use of immunostains in thicker melanomas may be because these “exhibit greater morphological heterogeneity, such as nodular, spindled and desmoplastic subtypes, that lead to additional confirmational testing,” Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan noted. However, they cautioned that extrinsic factors, including reimbursement fees and concerns about malpractice claims, could also influence the use of IHC stains in the diagnosis of melanomas.

“While Melan-A/MART-1 is a useful adjunct for determining melanocytic density or the presence of invasion in difficult cases, its routine use on melanomas has not been validated,” the researchers wrote in their analysis. “A consensus conference delineating the appropriate use of IHC in the diagnosis of melanoma may be of value in this regard.”

Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan also noted that while a greater proportion of the melanomas seen in the study were thick (greater than 4 mm) compared with most population-based studies, this may reflect patient management practices in which thinner melanomas are treated in outpatient centers while thicker ones get referred to tertiary care centers such as theirs.

The researchers disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

While there is little consensus on the ideal role of immunohistochemical (IHC) stains in the diagnosis of melanoma, their use increased dramatically over a 15-year period, according to results from a study.

Randie H. Kim, MD, PhD, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, of New York University, reviewed nearly 6,300 pathology reports from patients with melanomas, all referred (along with tissue samples) to their center from other institutions during 2001-2015. One or more IHC stains were used diagnostically in 871 cases during the study period, with use increasing from 5% of patients in 2001 to 25% in 2015 (P less than .0001). Usage increased gradually over time, although the number of stains used per case did not increase significantly (J Cutan Pathol. 2017 Mar;44[3]:221-7).

IHC stain use was associated with melanomas occurring on the head or neck (odds ratio = 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9), acral melanomas (OR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.1-2.0) and melanomas thicker than 4 mm (OR = 2.5; 95% CI 1.7-3.6). The most common stain used in the study was Melan-A/MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells), the most specific of the IHC markers available and the one “largely responsible for the increased incidence in overall immunostain use in our study,” the researchers wrote. “The perception that melanocytic markers, such as Melan-A, can more accurately stage melanomas, is a potential explanation for its increased usage over the duration of the study period.”

The higher use of immunostains in thicker melanomas may be because these “exhibit greater morphological heterogeneity, such as nodular, spindled and desmoplastic subtypes, that lead to additional confirmational testing,” Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan noted. However, they cautioned that extrinsic factors, including reimbursement fees and concerns about malpractice claims, could also influence the use of IHC stains in the diagnosis of melanomas.

“While Melan-A/MART-1 is a useful adjunct for determining melanocytic density or the presence of invasion in difficult cases, its routine use on melanomas has not been validated,” the researchers wrote in their analysis. “A consensus conference delineating the appropriate use of IHC in the diagnosis of melanoma may be of value in this regard.”

Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan also noted that while a greater proportion of the melanomas seen in the study were thick (greater than 4 mm) compared with most population-based studies, this may reflect patient management practices in which thinner melanomas are treated in outpatient centers while thicker ones get referred to tertiary care centers such as theirs.

The researchers disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

While there is little consensus on the ideal role of immunohistochemical (IHC) stains in the diagnosis of melanoma, their use increased dramatically over a 15-year period, according to results from a study.

Randie H. Kim, MD, PhD, and Shane A. Meehan, MD, of New York University, reviewed nearly 6,300 pathology reports from patients with melanomas, all referred (along with tissue samples) to their center from other institutions during 2001-2015. One or more IHC stains were used diagnostically in 871 cases during the study period, with use increasing from 5% of patients in 2001 to 25% in 2015 (P less than .0001). Usage increased gradually over time, although the number of stains used per case did not increase significantly (J Cutan Pathol. 2017 Mar;44[3]:221-7).

IHC stain use was associated with melanomas occurring on the head or neck (odds ratio = 1.6; 95% confidence interval, 1.4-1.9), acral melanomas (OR = 1.5; 95% CI 1.1-2.0) and melanomas thicker than 4 mm (OR = 2.5; 95% CI 1.7-3.6). The most common stain used in the study was Melan-A/MART-1 (melanoma antigen recognized by T cells), the most specific of the IHC markers available and the one “largely responsible for the increased incidence in overall immunostain use in our study,” the researchers wrote. “The perception that melanocytic markers, such as Melan-A, can more accurately stage melanomas, is a potential explanation for its increased usage over the duration of the study period.”

The higher use of immunostains in thicker melanomas may be because these “exhibit greater morphological heterogeneity, such as nodular, spindled and desmoplastic subtypes, that lead to additional confirmational testing,” Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan noted. However, they cautioned that extrinsic factors, including reimbursement fees and concerns about malpractice claims, could also influence the use of IHC stains in the diagnosis of melanomas.

“While Melan-A/MART-1 is a useful adjunct for determining melanocytic density or the presence of invasion in difficult cases, its routine use on melanomas has not been validated,” the researchers wrote in their analysis. “A consensus conference delineating the appropriate use of IHC in the diagnosis of melanoma may be of value in this regard.”

Dr. Kim and Dr. Meehan also noted that while a greater proportion of the melanomas seen in the study were thick (greater than 4 mm) compared with most population-based studies, this may reflect patient management practices in which thinner melanomas are treated in outpatient centers while thicker ones get referred to tertiary care centers such as theirs.

The researchers disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CUTANEOUS PATHOLOGY

Key clinical point:

Major finding: One or more stains was used diagnostically in 5% of melanoma cases in 2001, compared with 25% in 2015 (P less than .0001).

Data source: A retrospective review of more than 6,000 case records referred after diagnosis to a tertiary care center during 2001-2015.

Disclosures: The researchers disclosed no outside funding or conflicts of interest.

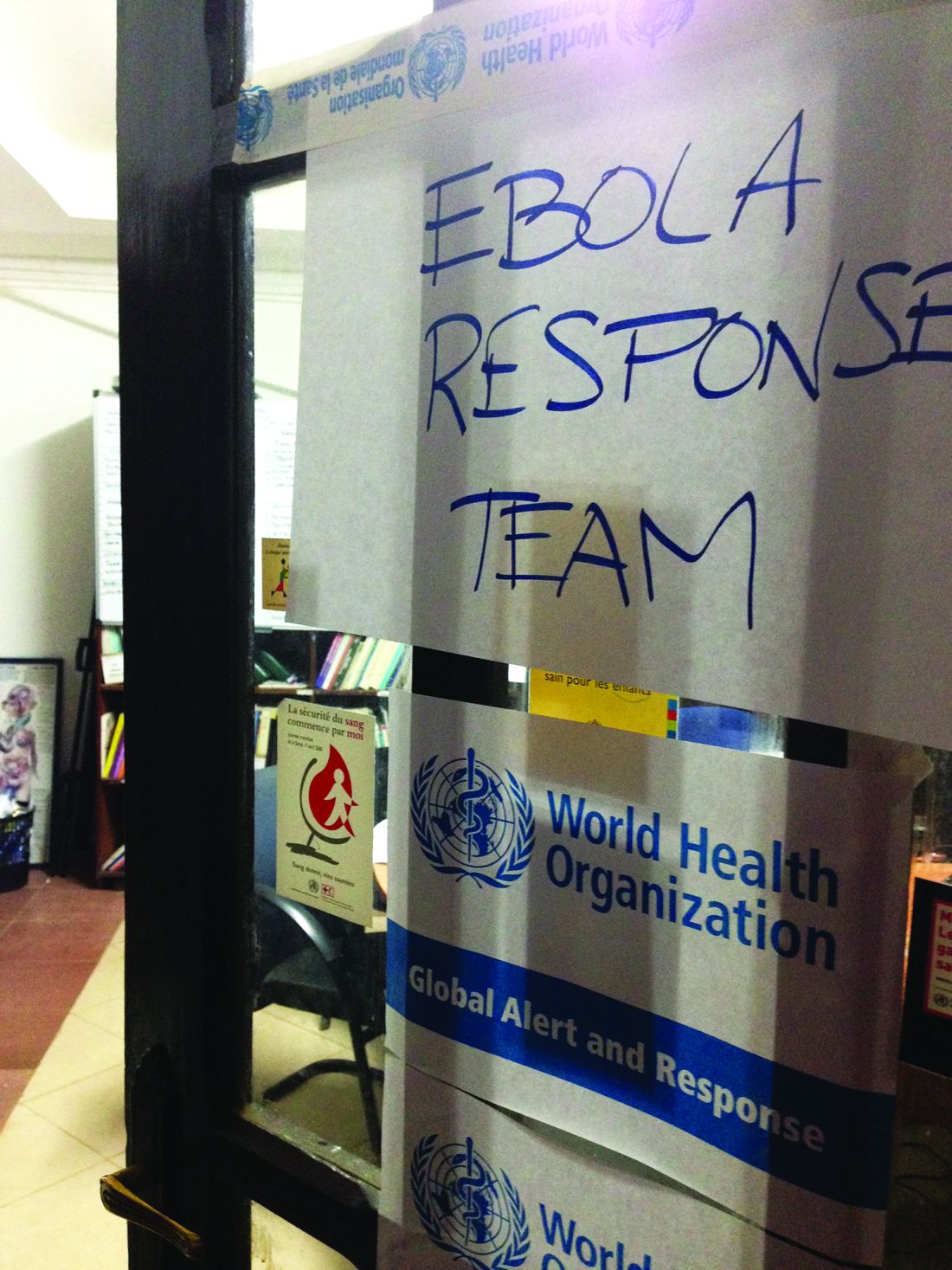

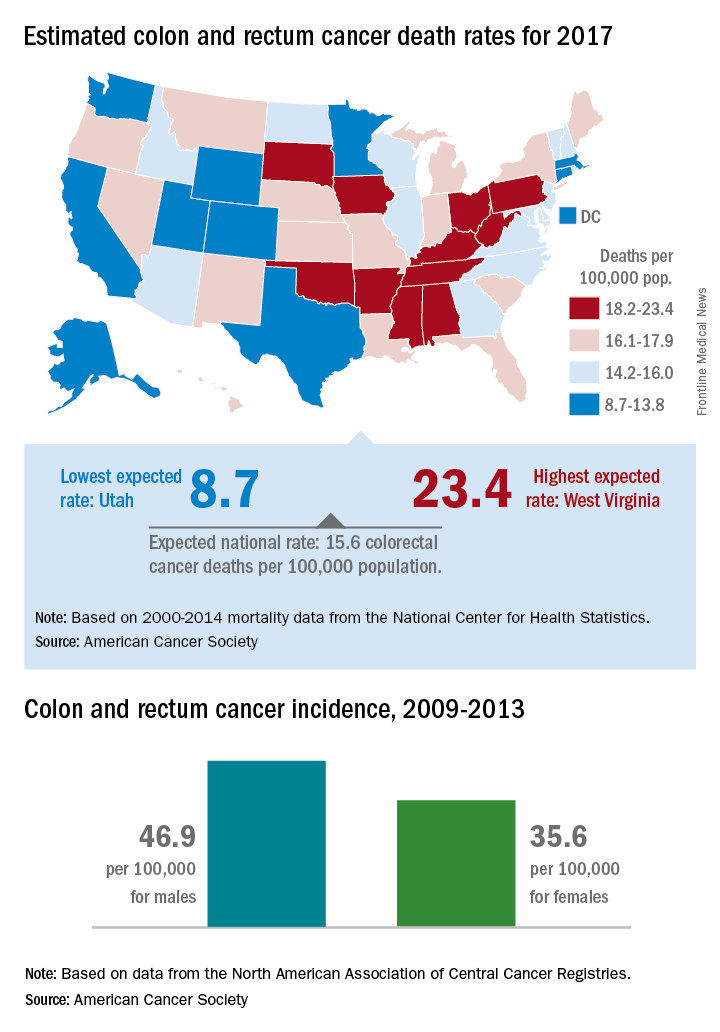

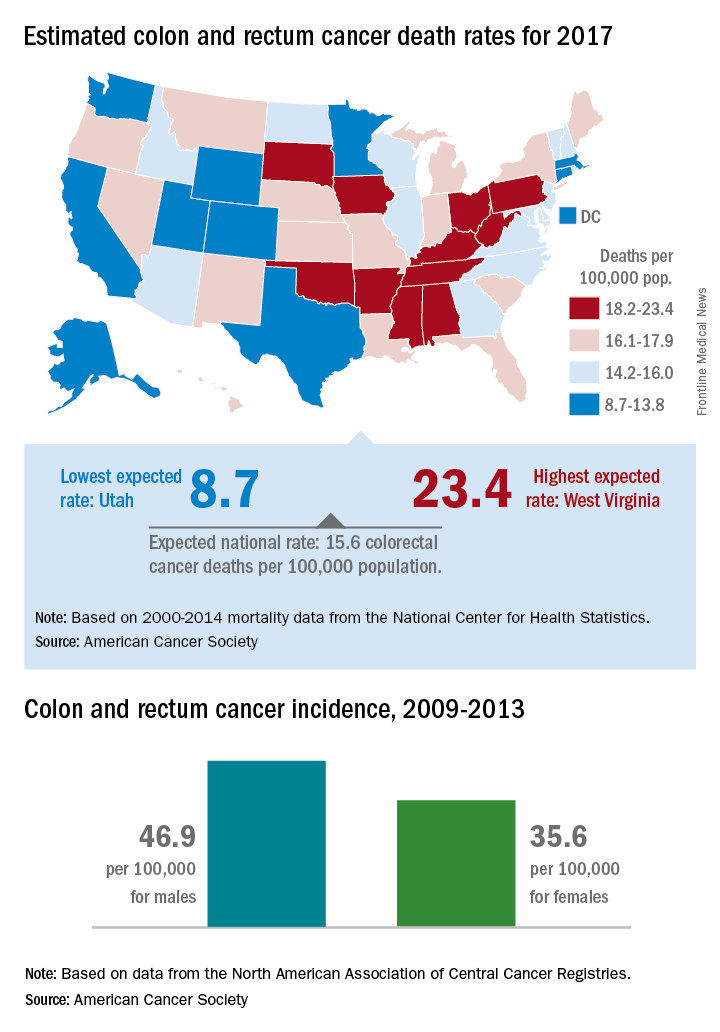

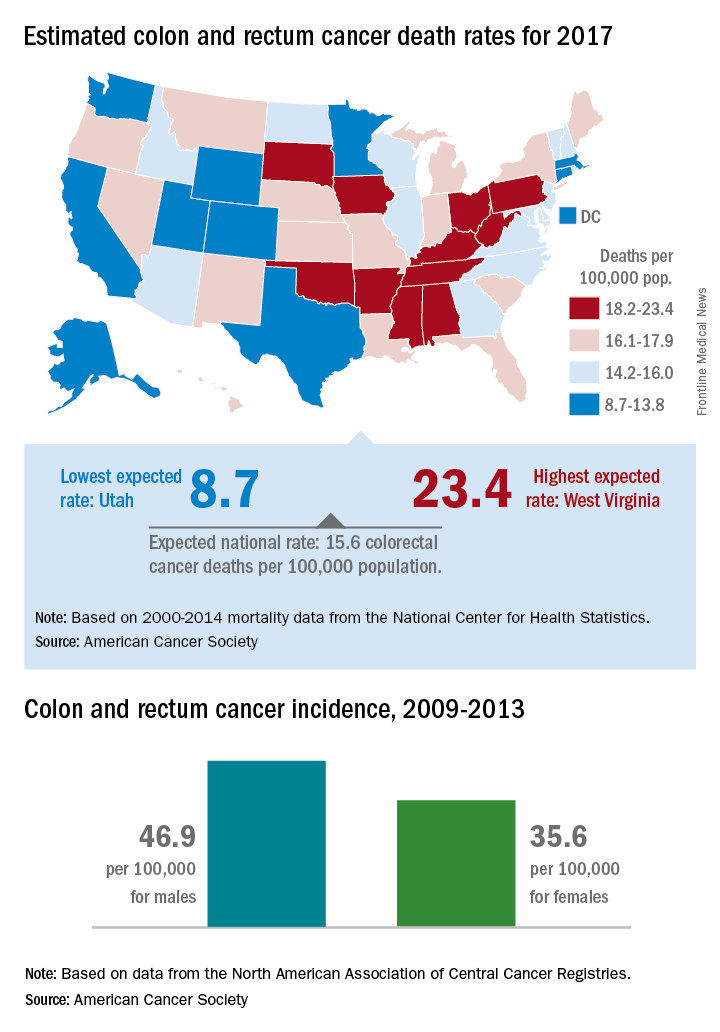

Colorectal cancer mortality highest in W.Va., lowest in Utah

Mortality from cancers of the colon and rectum is expected to be about 15.6 per 100,000 in 2017, with the highest rate in West Virginia and the lowest in Utah.

Approximately 50,260 colorectal cancer deaths are predicted for the year in the United States by the American Cancer Society in its Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, based on 2000-2014 data from the National Center for Health Statistics. With the population currently around 321 million, that works out to an expected death rate of 15.6 per 100,000 population. Doing a little more math produces death rates of 23.4 for West Virginia and 8.7 for Utah.

Utah had the lowest incidence rate over that time period for both men (36.1 per 100,000) and women (28.2 per 100,000), and Kentucky had the highest for both, with rates of 59.6 for men and 43.7 for women, the ACS said.

Mortality from cancers of the colon and rectum is expected to be about 15.6 per 100,000 in 2017, with the highest rate in West Virginia and the lowest in Utah.

Approximately 50,260 colorectal cancer deaths are predicted for the year in the United States by the American Cancer Society in its Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, based on 2000-2014 data from the National Center for Health Statistics. With the population currently around 321 million, that works out to an expected death rate of 15.6 per 100,000 population. Doing a little more math produces death rates of 23.4 for West Virginia and 8.7 for Utah.

Utah had the lowest incidence rate over that time period for both men (36.1 per 100,000) and women (28.2 per 100,000), and Kentucky had the highest for both, with rates of 59.6 for men and 43.7 for women, the ACS said.

Mortality from cancers of the colon and rectum is expected to be about 15.6 per 100,000 in 2017, with the highest rate in West Virginia and the lowest in Utah.

Approximately 50,260 colorectal cancer deaths are predicted for the year in the United States by the American Cancer Society in its Cancer Facts & Figures 2017, based on 2000-2014 data from the National Center for Health Statistics. With the population currently around 321 million, that works out to an expected death rate of 15.6 per 100,000 population. Doing a little more math produces death rates of 23.4 for West Virginia and 8.7 for Utah.

Utah had the lowest incidence rate over that time period for both men (36.1 per 100,000) and women (28.2 per 100,000), and Kentucky had the highest for both, with rates of 59.6 for men and 43.7 for women, the ACS said.

Standardize opioid prescribing after endocrine neck surgery, researchers say

Twenty oral morphine equivalents is the best option for pain relief medication with which to discharge outpatients after thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy surgery, according to researchers. The report was published online in Annals of Surgical Oncology.

Irene Lou, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and her coauthors conducted a prospective observational cohort study collecting data on pain scores and the oral morphine equivalents used by 313 adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy at two large endocrine surgery centers.

While patients were prescribed a median of 30 oral morphine equivalents at discharge – with a range from 0 to 120 – the median number of equivalents taken was 3 (with a range of 0-60).

Overall, 68.4% of patients took at least one oral morphine equivalent. The majority of patients (83%) took 10 or fewer oral morphine equivalents, and only 7% of patients took more than 20 oral morphine equivalents (Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 Feb 3. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5781-y).

Among the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents, 85% said it was for incisional pain, 4% said it was for sore throat, and 11% said it was for some other pain.

While the overall mean pain score after surgery was 2, the study found that mean pain scores in the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents were significantly higher than in patients who took 10 or fewer. Among patients who used narcotic pain relief, 1% said they did so because they were instructed to despite having reported no pain.

Other factors predicting higher oral morphine equivalent use were age – patients tended to be younger than 45 years – total thyroidectomy, or a history of previous narcotic use.

“Based on our results, we have changed our practices to discharge all patients undergoing parathyroid or thyroid surgery and to request an oral narcotic prescription with no more than 20 equivalents, which translates to 20 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325” the authors wrote.

Noting that the abuse and misuse of prescription opioids is the leading cause of overdose deaths in the United States, they argued that standardized prescribing practices are a way to not only reduce waste but also to improve patient safety.

“We also discovered that even between our two institutions, there was no standard prescribing pattern, with a wide range of prescriptions and number of equivalents dispensed.”

The authors also examined alternative and adjunctive methods of pain relief, pointing to previous studies suggesting benefits from preoperative gabapentin, postoperative music therapy, postoperative ice packs, and nonopioid analgesics.

They noted that because their study covered the breadth of endocrine neck operations, it did include patients who had minimally invasive surgery through to those who underwent total thyroidectomy with neck dissections. They also pointed out that the data pain scores and oral morphine equivalent use was based on patient recollection.

“Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is the first to examine outpatient narcotic pain medication use after thyroid and parathyroid surgery,” they said. “A standardized practice of prescribing stands to increase patient safety and minimize the risks of dependence and overdose.”

Two authors were supported by National Institutes of Health grants. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Twenty oral morphine equivalents is the best option for pain relief medication with which to discharge outpatients after thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy surgery, according to researchers. The report was published online in Annals of Surgical Oncology.

Irene Lou, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and her coauthors conducted a prospective observational cohort study collecting data on pain scores and the oral morphine equivalents used by 313 adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy at two large endocrine surgery centers.

While patients were prescribed a median of 30 oral morphine equivalents at discharge – with a range from 0 to 120 – the median number of equivalents taken was 3 (with a range of 0-60).

Overall, 68.4% of patients took at least one oral morphine equivalent. The majority of patients (83%) took 10 or fewer oral morphine equivalents, and only 7% of patients took more than 20 oral morphine equivalents (Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 Feb 3. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5781-y).

Among the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents, 85% said it was for incisional pain, 4% said it was for sore throat, and 11% said it was for some other pain.

While the overall mean pain score after surgery was 2, the study found that mean pain scores in the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents were significantly higher than in patients who took 10 or fewer. Among patients who used narcotic pain relief, 1% said they did so because they were instructed to despite having reported no pain.

Other factors predicting higher oral morphine equivalent use were age – patients tended to be younger than 45 years – total thyroidectomy, or a history of previous narcotic use.

“Based on our results, we have changed our practices to discharge all patients undergoing parathyroid or thyroid surgery and to request an oral narcotic prescription with no more than 20 equivalents, which translates to 20 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325” the authors wrote.

Noting that the abuse and misuse of prescription opioids is the leading cause of overdose deaths in the United States, they argued that standardized prescribing practices are a way to not only reduce waste but also to improve patient safety.

“We also discovered that even between our two institutions, there was no standard prescribing pattern, with a wide range of prescriptions and number of equivalents dispensed.”

The authors also examined alternative and adjunctive methods of pain relief, pointing to previous studies suggesting benefits from preoperative gabapentin, postoperative music therapy, postoperative ice packs, and nonopioid analgesics.

They noted that because their study covered the breadth of endocrine neck operations, it did include patients who had minimally invasive surgery through to those who underwent total thyroidectomy with neck dissections. They also pointed out that the data pain scores and oral morphine equivalent use was based on patient recollection.

“Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is the first to examine outpatient narcotic pain medication use after thyroid and parathyroid surgery,” they said. “A standardized practice of prescribing stands to increase patient safety and minimize the risks of dependence and overdose.”

Two authors were supported by National Institutes of Health grants. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Twenty oral morphine equivalents is the best option for pain relief medication with which to discharge outpatients after thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy surgery, according to researchers. The report was published online in Annals of Surgical Oncology.

Irene Lou, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, and her coauthors conducted a prospective observational cohort study collecting data on pain scores and the oral morphine equivalents used by 313 adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy at two large endocrine surgery centers.

While patients were prescribed a median of 30 oral morphine equivalents at discharge – with a range from 0 to 120 – the median number of equivalents taken was 3 (with a range of 0-60).

Overall, 68.4% of patients took at least one oral morphine equivalent. The majority of patients (83%) took 10 or fewer oral morphine equivalents, and only 7% of patients took more than 20 oral morphine equivalents (Ann Surg Oncol. 2017 Feb 3. doi: 10.1245/s10434-017-5781-y).

Among the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents, 85% said it was for incisional pain, 4% said it was for sore throat, and 11% said it was for some other pain.

While the overall mean pain score after surgery was 2, the study found that mean pain scores in the patients who took more than 10 oral morphine equivalents were significantly higher than in patients who took 10 or fewer. Among patients who used narcotic pain relief, 1% said they did so because they were instructed to despite having reported no pain.

Other factors predicting higher oral morphine equivalent use were age – patients tended to be younger than 45 years – total thyroidectomy, or a history of previous narcotic use.

“Based on our results, we have changed our practices to discharge all patients undergoing parathyroid or thyroid surgery and to request an oral narcotic prescription with no more than 20 equivalents, which translates to 20 tablets of hydrocodone/acetaminophen 5/325” the authors wrote.

Noting that the abuse and misuse of prescription opioids is the leading cause of overdose deaths in the United States, they argued that standardized prescribing practices are a way to not only reduce waste but also to improve patient safety.

“We also discovered that even between our two institutions, there was no standard prescribing pattern, with a wide range of prescriptions and number of equivalents dispensed.”

The authors also examined alternative and adjunctive methods of pain relief, pointing to previous studies suggesting benefits from preoperative gabapentin, postoperative music therapy, postoperative ice packs, and nonopioid analgesics.

They noted that because their study covered the breadth of endocrine neck operations, it did include patients who had minimally invasive surgery through to those who underwent total thyroidectomy with neck dissections. They also pointed out that the data pain scores and oral morphine equivalent use was based on patient recollection.

“Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is the first to examine outpatient narcotic pain medication use after thyroid and parathyroid surgery,” they said. “A standardized practice of prescribing stands to increase patient safety and minimize the risks of dependence and overdose.”

Two authors were supported by National Institutes of Health grants. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM ANNALS OF SURGICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Twenty oral morphine equivalents is the ideal amount of pain relief medication with which to discharge outpatients after thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy surgery.

Major finding: Only 7% of patients who undergo thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy use more than 20 oral morphine equivalents for postoperative pain relief.

Data source: Observational cohort study of 313 adult patients undergoing thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy.

Disclosures: Two authors were supported by National Institutes of Health grants. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Resective Epilepsy Surgery May Be Beneficial in Patients 70 and Older

HOUSTON—Elderly patients with refractory epilepsy may achieve a positive surgical outcome from resective epilepsy surgery, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” said Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland. “We expected that [the rate of] complications would be higher, because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Cases of new-onset epilepsy have increased nearly fivefold during the past 40 years in patients ages 65 and older. “With a rapidly growing, healthier, and longer living population, it is a matter of time before we see more and more elderly patients with medically refractory epilepsy who may be potential candidates for resective epilepsy surgery,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

Dr. Abdelkader and colleagues used the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center database to identify patients ages 70 and older who underwent resective epilepsy surgery between January 1, 2000, and September 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of postsurgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73, and the age at epilepsy onset ranged from 24 to 71, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. The mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%.

Four patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures. All but one patient, however, had a positive MRI. Three patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique, because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. No surgical complications were reported. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale. Four patients were completely free of seizures at one year of follow-up.

One of the patients underwent two resective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes 11 years after the first surgery; he was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

Future multicenter collaborative studies should “prospectively study factors influencing resective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

—Doug Brunk

Suggested Reading

Dewar S, Eliashiv D, Walshaw PD, et al. Safety, efficacy, and life satisfaction following epilepsy surgery in patients aged 60 years and older. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(4):945-951.

HOUSTON—Elderly patients with refractory epilepsy may achieve a positive surgical outcome from resective epilepsy surgery, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” said Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland. “We expected that [the rate of] complications would be higher, because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Cases of new-onset epilepsy have increased nearly fivefold during the past 40 years in patients ages 65 and older. “With a rapidly growing, healthier, and longer living population, it is a matter of time before we see more and more elderly patients with medically refractory epilepsy who may be potential candidates for resective epilepsy surgery,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

Dr. Abdelkader and colleagues used the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center database to identify patients ages 70 and older who underwent resective epilepsy surgery between January 1, 2000, and September 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of postsurgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73, and the age at epilepsy onset ranged from 24 to 71, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. The mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%.

Four patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures. All but one patient, however, had a positive MRI. Three patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique, because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. No surgical complications were reported. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale. Four patients were completely free of seizures at one year of follow-up.

One of the patients underwent two resective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes 11 years after the first surgery; he was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

Future multicenter collaborative studies should “prospectively study factors influencing resective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

—Doug Brunk

Suggested Reading

Dewar S, Eliashiv D, Walshaw PD, et al. Safety, efficacy, and life satisfaction following epilepsy surgery in patients aged 60 years and older. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(4):945-951.

HOUSTON—Elderly patients with refractory epilepsy may achieve a positive surgical outcome from resective epilepsy surgery, according to research presented at the 70th Annual Meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

The findings “were a surprise to us,” said Ahmed Abdelkader, MD, a research fellow at University Hospitals Case Medical Center in Cleveland. “We expected that [the rate of] complications would be higher, because this is a vulnerable age group with multiple comorbidities.”

Cases of new-onset epilepsy have increased nearly fivefold during the past 40 years in patients ages 65 and older. “With a rapidly growing, healthier, and longer living population, it is a matter of time before we see more and more elderly patients with medically refractory epilepsy who may be potential candidates for resective epilepsy surgery,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

Dr. Abdelkader and colleagues used the Cleveland Clinic Epilepsy Center database to identify patients ages 70 and older who underwent resective epilepsy surgery between January 1, 2000, and September 30, 2015. They limited the analysis to seven patients who had at least one year of postsurgical follow-up. The mean age of the patients at surgery was 73, and the age at epilepsy onset ranged from 24 to 71, with a monthly frequency of 4.2 seizures. The mean Charlson Combined Comorbidity Index score was 4, which translated into a 10-year mean survival probability of 53%.

Four patients (57%) had a history of significant injuries due to seizures. All but one patient, however, had a positive MRI. Three patients had hippocampal sclerosis, “which is unique, because most cases of hippocampal sclerosis are in younger age groups,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

All patients underwent anterior temporal lobectomy, four on the left side. No surgical complications were reported. Six of the seven patients had a good surgical outcome, defined as a Class I or II on the Engel Epilepsy Surgery Outcome Scale. Four patients were completely free of seizures at one year of follow-up.

One of the patients underwent two resective epilepsy surgeries: the first at age 72 and the second at age 75. He died of natural causes 11 years after the first surgery; he was the only patient to pass away during the follow-up period.

Future multicenter collaborative studies should “prospectively study factors influencing resective epilepsy surgery recommendation and its outcome in this rapidly growing population,” said Dr. Abdelkader.

—Doug Brunk

Suggested Reading

Dewar S, Eliashiv D, Walshaw PD, et al. Safety, efficacy, and life satisfaction following epilepsy surgery in patients aged 60 years and older. J Neurosurg. 2016;124(4):945-951.

As-Needed Anticoagulation for Intermittent Atrial Fibrillation Raises Concerns

ORLANDO—As-needed anticoagulation could be effective in preventing stroke in at least some patients after successful ablation of atrial fibrillation, according to a pilot study presented at the 22nd Annual International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium. Neurologists are interpreting the results with caution, however.

The positive findings, originally reported at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), were updated at the International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium by Francis Marchlinski, MD, Director of Cardiac Electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. When delivering the data, he provided several caveats before other atrial fibrillation experts added their own.

Guidelines Recommend Anticoagulation

The study was conducted in response to the substantial number of patients who request discontinuation of their anticoagulation therapy after a successful ablation for atrial fibrillation, according to Dr. Marchlinski. Current guidelines recommend anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation following ablation if they have risk factors for stroke, even if their atrial fibrillation is controlled. The risk of stroke in patients with a negative ECG after ablation, however, appears to be “in the neighborhood of 0.1%,” according to Dr. Marchlinski, who cited five observational studies.

“There are no randomized prospective trials that have assessed the safety of stopping anticoagulants, but the fact is that this is a pretty low event rate if the observational studies are accurate, and even if they are off by severalfold, it is likely that we would be unable to show the benefit of continuing anticoagulants in these patients,” Dr. Marchlinski observed.

Researchers Observed One Cerebrovascular Accident

A strategy of as-needed anticoagulation has been made practical by the introduction of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), which have a rapid onset of action, relative to warfarin, and would therefore be expected to provide rapid protection against atrial-fibrillation-related stroke risk if initiated upon atrial fibrillation onset, according to Dr. Marchlinski. To test this approach, 105 “highly motivated” patients with atrial fibrillation were selected for the pilot study.

In addition to three weeks of ECG monitoring to confirm the absence of atrial fibrillation, patients participating in the trial were required to demonstrate skill in pulse assessment, which they agreed to perform on a twice-daily basis. Use of a smartphone app that can detect atrial fibrillation was encouraged, but not required. All patients were required to fill a prescription for a NOAC and told to initiate therapy for any atrial fibrillation episode of more than one hour.

Of the 105 patients, four were noncompliant with atrial fibrillation monitoring and were removed from the study. Another two patients voluntarily requested to return to daily NOAC treatment. The remaining 99 were followed for 30 months. Of these participants, 18 had multiple episodes of atrial fibrillation and were transitioned back to daily NOAC therapy. In all, 15 patients used NOAC on an as-needed basis at least once, but remained off daily therapy, and the remaining 66 did not have an episode of atrial fibrillation that triggered a course of NOAC therapy.

In 263 patient years of follow-up, there was a single cerebrovascular accident (CVA). This event occurred in an 81-year-old patient with a history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and an atherosclerotic aortic arch on imaging. The patient presented with neurologic symptoms, but had a negative ECG. The CVA symptoms resolved with treatment.

In presenting these data, Dr. Marchlinski said, “Pro re nata use of NOACs may be safe and effective to maintain a low risk of stroke when patients are adherent to diligent pulse monitoring.” However, he reiterated that the study group consisted of “a select group of motivated patients,” and he emphasized that the patients must be followed closely.

Are Risk Factors Well Understood?

In a discussion that followed this presentation, several experts expressed the usual caution about drawing conclusions from a single uncontrolled study, but Elaine M. Hylek, MD, Professor of Medicine at Boston University, expressed additional reservations about the “pill in a pocket” strategy. In particular, she noted an imperfect correlation between onset of atrial fibrillation and stroke risk. “I think this makes us [reluctant] to stop oral anticoagulation,” she said.

The available data suggest that “once the atrial fibrillation is gone, the risk of stroke recedes,” according to Daniel Singer, MD, Chief of Epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston. He indicated, however, that all the variables of risk may not be fully understood. More “hard data” are needed to endorse a wider application of on-demand anticoagulation in patients like those entered into this study, he said.

The fact that patients without atrial fibrillation following ablation remain at substantial risk of atrial fibrillation recurrences, including asymptomatic episodes, is a liability of as-needed anticoagulation, conceded Dr. Marchlinski. However, these initial results provide promise for the substantial proportion of patients without atrial fibrillation after ablation who wish to avoid anticoagulants and are willing to consider risks and benefits.

Dr. Marchlinski reported financial relationships with Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic.

—Ted Bosworth

Suggested Reading

Karasoy D, Gislason GH, Hansen J, et al. Oral anticoagulation therapy after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation and the risk of thromboembolism and serious bleeding: long-term follow-up in nationwide cohort of Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(5):307-314a.

Link MS, Haïssaguerre M, Natale A. Ablation of atrial fibrillation: patient selection, periprocedural anticoagulation, techniques, and preventive measures after ablation. Circulation. 2016;134(4):339-352.

Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Deshmukh AJ, et al. Patterns of anticoagulation use and cardioembolic risk after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11). pii: e002597.

ORLANDO—As-needed anticoagulation could be effective in preventing stroke in at least some patients after successful ablation of atrial fibrillation, according to a pilot study presented at the 22nd Annual International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium. Neurologists are interpreting the results with caution, however.

The positive findings, originally reported at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), were updated at the International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium by Francis Marchlinski, MD, Director of Cardiac Electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. When delivering the data, he provided several caveats before other atrial fibrillation experts added their own.

Guidelines Recommend Anticoagulation

The study was conducted in response to the substantial number of patients who request discontinuation of their anticoagulation therapy after a successful ablation for atrial fibrillation, according to Dr. Marchlinski. Current guidelines recommend anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation following ablation if they have risk factors for stroke, even if their atrial fibrillation is controlled. The risk of stroke in patients with a negative ECG after ablation, however, appears to be “in the neighborhood of 0.1%,” according to Dr. Marchlinski, who cited five observational studies.

“There are no randomized prospective trials that have assessed the safety of stopping anticoagulants, but the fact is that this is a pretty low event rate if the observational studies are accurate, and even if they are off by severalfold, it is likely that we would be unable to show the benefit of continuing anticoagulants in these patients,” Dr. Marchlinski observed.

Researchers Observed One Cerebrovascular Accident

A strategy of as-needed anticoagulation has been made practical by the introduction of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), which have a rapid onset of action, relative to warfarin, and would therefore be expected to provide rapid protection against atrial-fibrillation-related stroke risk if initiated upon atrial fibrillation onset, according to Dr. Marchlinski. To test this approach, 105 “highly motivated” patients with atrial fibrillation were selected for the pilot study.

In addition to three weeks of ECG monitoring to confirm the absence of atrial fibrillation, patients participating in the trial were required to demonstrate skill in pulse assessment, which they agreed to perform on a twice-daily basis. Use of a smartphone app that can detect atrial fibrillation was encouraged, but not required. All patients were required to fill a prescription for a NOAC and told to initiate therapy for any atrial fibrillation episode of more than one hour.

Of the 105 patients, four were noncompliant with atrial fibrillation monitoring and were removed from the study. Another two patients voluntarily requested to return to daily NOAC treatment. The remaining 99 were followed for 30 months. Of these participants, 18 had multiple episodes of atrial fibrillation and were transitioned back to daily NOAC therapy. In all, 15 patients used NOAC on an as-needed basis at least once, but remained off daily therapy, and the remaining 66 did not have an episode of atrial fibrillation that triggered a course of NOAC therapy.

In 263 patient years of follow-up, there was a single cerebrovascular accident (CVA). This event occurred in an 81-year-old patient with a history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and an atherosclerotic aortic arch on imaging. The patient presented with neurologic symptoms, but had a negative ECG. The CVA symptoms resolved with treatment.

In presenting these data, Dr. Marchlinski said, “Pro re nata use of NOACs may be safe and effective to maintain a low risk of stroke when patients are adherent to diligent pulse monitoring.” However, he reiterated that the study group consisted of “a select group of motivated patients,” and he emphasized that the patients must be followed closely.

Are Risk Factors Well Understood?

In a discussion that followed this presentation, several experts expressed the usual caution about drawing conclusions from a single uncontrolled study, but Elaine M. Hylek, MD, Professor of Medicine at Boston University, expressed additional reservations about the “pill in a pocket” strategy. In particular, she noted an imperfect correlation between onset of atrial fibrillation and stroke risk. “I think this makes us [reluctant] to stop oral anticoagulation,” she said.

The available data suggest that “once the atrial fibrillation is gone, the risk of stroke recedes,” according to Daniel Singer, MD, Chief of Epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston. He indicated, however, that all the variables of risk may not be fully understood. More “hard data” are needed to endorse a wider application of on-demand anticoagulation in patients like those entered into this study, he said.

The fact that patients without atrial fibrillation following ablation remain at substantial risk of atrial fibrillation recurrences, including asymptomatic episodes, is a liability of as-needed anticoagulation, conceded Dr. Marchlinski. However, these initial results provide promise for the substantial proportion of patients without atrial fibrillation after ablation who wish to avoid anticoagulants and are willing to consider risks and benefits.

Dr. Marchlinski reported financial relationships with Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic.

—Ted Bosworth

Suggested Reading

Karasoy D, Gislason GH, Hansen J, et al. Oral anticoagulation therapy after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation and the risk of thromboembolism and serious bleeding: long-term follow-up in nationwide cohort of Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(5):307-314a.

Link MS, Haïssaguerre M, Natale A. Ablation of atrial fibrillation: patient selection, periprocedural anticoagulation, techniques, and preventive measures after ablation. Circulation. 2016;134(4):339-352.

Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Deshmukh AJ, et al. Patterns of anticoagulation use and cardioembolic risk after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11). pii: e002597.

ORLANDO—As-needed anticoagulation could be effective in preventing stroke in at least some patients after successful ablation of atrial fibrillation, according to a pilot study presented at the 22nd Annual International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium. Neurologists are interpreting the results with caution, however.

The positive findings, originally reported at the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), were updated at the International Atrial Fibrillation Symposium by Francis Marchlinski, MD, Director of Cardiac Electrophysiology at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. When delivering the data, he provided several caveats before other atrial fibrillation experts added their own.

Guidelines Recommend Anticoagulation

The study was conducted in response to the substantial number of patients who request discontinuation of their anticoagulation therapy after a successful ablation for atrial fibrillation, according to Dr. Marchlinski. Current guidelines recommend anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation following ablation if they have risk factors for stroke, even if their atrial fibrillation is controlled. The risk of stroke in patients with a negative ECG after ablation, however, appears to be “in the neighborhood of 0.1%,” according to Dr. Marchlinski, who cited five observational studies.

“There are no randomized prospective trials that have assessed the safety of stopping anticoagulants, but the fact is that this is a pretty low event rate if the observational studies are accurate, and even if they are off by severalfold, it is likely that we would be unable to show the benefit of continuing anticoagulants in these patients,” Dr. Marchlinski observed.

Researchers Observed One Cerebrovascular Accident

A strategy of as-needed anticoagulation has been made practical by the introduction of novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), which have a rapid onset of action, relative to warfarin, and would therefore be expected to provide rapid protection against atrial-fibrillation-related stroke risk if initiated upon atrial fibrillation onset, according to Dr. Marchlinski. To test this approach, 105 “highly motivated” patients with atrial fibrillation were selected for the pilot study.

In addition to three weeks of ECG monitoring to confirm the absence of atrial fibrillation, patients participating in the trial were required to demonstrate skill in pulse assessment, which they agreed to perform on a twice-daily basis. Use of a smartphone app that can detect atrial fibrillation was encouraged, but not required. All patients were required to fill a prescription for a NOAC and told to initiate therapy for any atrial fibrillation episode of more than one hour.

Of the 105 patients, four were noncompliant with atrial fibrillation monitoring and were removed from the study. Another two patients voluntarily requested to return to daily NOAC treatment. The remaining 99 were followed for 30 months. Of these participants, 18 had multiple episodes of atrial fibrillation and were transitioned back to daily NOAC therapy. In all, 15 patients used NOAC on an as-needed basis at least once, but remained off daily therapy, and the remaining 66 did not have an episode of atrial fibrillation that triggered a course of NOAC therapy.

In 263 patient years of follow-up, there was a single cerebrovascular accident (CVA). This event occurred in an 81-year-old patient with a history of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and an atherosclerotic aortic arch on imaging. The patient presented with neurologic symptoms, but had a negative ECG. The CVA symptoms resolved with treatment.

In presenting these data, Dr. Marchlinski said, “Pro re nata use of NOACs may be safe and effective to maintain a low risk of stroke when patients are adherent to diligent pulse monitoring.” However, he reiterated that the study group consisted of “a select group of motivated patients,” and he emphasized that the patients must be followed closely.

Are Risk Factors Well Understood?

In a discussion that followed this presentation, several experts expressed the usual caution about drawing conclusions from a single uncontrolled study, but Elaine M. Hylek, MD, Professor of Medicine at Boston University, expressed additional reservations about the “pill in a pocket” strategy. In particular, she noted an imperfect correlation between onset of atrial fibrillation and stroke risk. “I think this makes us [reluctant] to stop oral anticoagulation,” she said.

The available data suggest that “once the atrial fibrillation is gone, the risk of stroke recedes,” according to Daniel Singer, MD, Chief of Epidemiology at Harvard School of Public Health in Boston. He indicated, however, that all the variables of risk may not be fully understood. More “hard data” are needed to endorse a wider application of on-demand anticoagulation in patients like those entered into this study, he said.

The fact that patients without atrial fibrillation following ablation remain at substantial risk of atrial fibrillation recurrences, including asymptomatic episodes, is a liability of as-needed anticoagulation, conceded Dr. Marchlinski. However, these initial results provide promise for the substantial proportion of patients without atrial fibrillation after ablation who wish to avoid anticoagulants and are willing to consider risks and benefits.

Dr. Marchlinski reported financial relationships with Abbott, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, St. Jude Medical, and Medtronic.

—Ted Bosworth

Suggested Reading

Karasoy D, Gislason GH, Hansen J, et al. Oral anticoagulation therapy after radiofrequency ablation of atrial fibrillation and the risk of thromboembolism and serious bleeding: long-term follow-up in nationwide cohort of Denmark. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(5):307-314a.

Link MS, Haïssaguerre M, Natale A. Ablation of atrial fibrillation: patient selection, periprocedural anticoagulation, techniques, and preventive measures after ablation. Circulation. 2016;134(4):339-352.

Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Deshmukh AJ, et al. Patterns of anticoagulation use and cardioembolic risk after catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11). pii: e002597.

Ebola research update: January-February 2017

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

Italian researchers observed the presence of total Ebola virus RNA and replication markers in specimens of the lower respiratory tract, even after viral clearance from plasma, suggesting possible local replication.

Researchers have identified a mechanism that appears to represent one way that host cells have evolved to outsmart infection by Ebola and other viruses, according to a study in PLOS Pathogens.

Post–Ebola virus disease symptoms can remain long after recovery and long-term viral persistence in semen is confirmed, according to a study in Lancet Infectious Diseases. The authors say the results justify calls for regular check-ups of survivors at least 18 months after recovery.

A new mouse model of early Ebola virus infection may show how early immune responses can affect the development of Ebola virus disease, according to a study in Cell Reports, and identify protective immune responses as targets for developing human Ebola virus therapeutics.

The addition of disease surveillance officers in Kambia, Sierra Leone, enabled public health officials to provide a more timely response to Ebola virus alerts as well as conduct active case searching throughout the district, according to a report in MMWR, which investigators said was associated with earlier detection and a decline in number of new Ebola virus disease cases recorded.

A study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases proposed highly predictive and easy-to-use prognostic tools that stratify the risk of Ebola virus disease mortality at or after Ebola virus disease triage.

According to a study published in the Journal of Human Lactation, donor human milk processed at nonprofit milk banks is safe from Ebola and Marburg viruses because the viruses are safely inactivated in human milk by standard North American pasteurization techniques.

A recent study found that the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola epidemic was largely driven and sustained by “superspreadings” that were ubiquitous throughout the outbreak, and that age is an important demographic predictor for superspreading. The authors said their results highlight the importance of control measures targeted at potential superspreaders and enhance understanding of causes and consequences of superspreading for Ebola virus.

Ebola, and more recently Zika and yellow fever, have demonstrated that the world does not yet have a reliable or robust global system for preventing, detecting, and responding to disease outbreaks, according to an analysis in BMJ.

Ebola virus strains can be generated that replicate and cause disease within new host rodent species, according to a bioinformatics study, raising concerns that few mutations may result in novel human pathogenic Ebola viruses.

A study in Sierra Leone using a new highly specific and sensitive assay found that asymptomatic infection with Ebola virus was uncommon despite high exposure. The authors said “low prevalence suggests asymptomatic infection contributes little to herd immunity in Ebola, and even if infectious, would account for few transmissions.”

Malaria parasite coinfection was common in patients presenting to Ebola Treatment Units in Sierra Leone, according to a study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, and conferred an increased mortality risk in patients infected with Ebola virus, supporting empirical malaria treatment in Ebola Treatment Units. The authors said high mortality among patients without Ebola virus disease or malaria suggests expanded testing and treatment might improve care in future Ebola epidemics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

Italian researchers observed the presence of total Ebola virus RNA and replication markers in specimens of the lower respiratory tract, even after viral clearance from plasma, suggesting possible local replication.

Researchers have identified a mechanism that appears to represent one way that host cells have evolved to outsmart infection by Ebola and other viruses, according to a study in PLOS Pathogens.

Post–Ebola virus disease symptoms can remain long after recovery and long-term viral persistence in semen is confirmed, according to a study in Lancet Infectious Diseases. The authors say the results justify calls for regular check-ups of survivors at least 18 months after recovery.

A new mouse model of early Ebola virus infection may show how early immune responses can affect the development of Ebola virus disease, according to a study in Cell Reports, and identify protective immune responses as targets for developing human Ebola virus therapeutics.

The addition of disease surveillance officers in Kambia, Sierra Leone, enabled public health officials to provide a more timely response to Ebola virus alerts as well as conduct active case searching throughout the district, according to a report in MMWR, which investigators said was associated with earlier detection and a decline in number of new Ebola virus disease cases recorded.

A study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases proposed highly predictive and easy-to-use prognostic tools that stratify the risk of Ebola virus disease mortality at or after Ebola virus disease triage.

According to a study published in the Journal of Human Lactation, donor human milk processed at nonprofit milk banks is safe from Ebola and Marburg viruses because the viruses are safely inactivated in human milk by standard North American pasteurization techniques.

A recent study found that the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola epidemic was largely driven and sustained by “superspreadings” that were ubiquitous throughout the outbreak, and that age is an important demographic predictor for superspreading. The authors said their results highlight the importance of control measures targeted at potential superspreaders and enhance understanding of causes and consequences of superspreading for Ebola virus.

Ebola, and more recently Zika and yellow fever, have demonstrated that the world does not yet have a reliable or robust global system for preventing, detecting, and responding to disease outbreaks, according to an analysis in BMJ.

Ebola virus strains can be generated that replicate and cause disease within new host rodent species, according to a bioinformatics study, raising concerns that few mutations may result in novel human pathogenic Ebola viruses.

A study in Sierra Leone using a new highly specific and sensitive assay found that asymptomatic infection with Ebola virus was uncommon despite high exposure. The authors said “low prevalence suggests asymptomatic infection contributes little to herd immunity in Ebola, and even if infectious, would account for few transmissions.”

Malaria parasite coinfection was common in patients presenting to Ebola Treatment Units in Sierra Leone, according to a study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, and conferred an increased mortality risk in patients infected with Ebola virus, supporting empirical malaria treatment in Ebola Treatment Units. The authors said high mortality among patients without Ebola virus disease or malaria suggests expanded testing and treatment might improve care in future Ebola epidemics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

The struggle to defeat Ebola virus disease continues globally, although it may not always make the headlines. To catch up on what you may have missed, here are some notable news items and journal articles published over the past few weeks that are worth a second look.

Italian researchers observed the presence of total Ebola virus RNA and replication markers in specimens of the lower respiratory tract, even after viral clearance from plasma, suggesting possible local replication.

Researchers have identified a mechanism that appears to represent one way that host cells have evolved to outsmart infection by Ebola and other viruses, according to a study in PLOS Pathogens.

Post–Ebola virus disease symptoms can remain long after recovery and long-term viral persistence in semen is confirmed, according to a study in Lancet Infectious Diseases. The authors say the results justify calls for regular check-ups of survivors at least 18 months after recovery.

A new mouse model of early Ebola virus infection may show how early immune responses can affect the development of Ebola virus disease, according to a study in Cell Reports, and identify protective immune responses as targets for developing human Ebola virus therapeutics.

The addition of disease surveillance officers in Kambia, Sierra Leone, enabled public health officials to provide a more timely response to Ebola virus alerts as well as conduct active case searching throughout the district, according to a report in MMWR, which investigators said was associated with earlier detection and a decline in number of new Ebola virus disease cases recorded.

A study published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases proposed highly predictive and easy-to-use prognostic tools that stratify the risk of Ebola virus disease mortality at or after Ebola virus disease triage.

According to a study published in the Journal of Human Lactation, donor human milk processed at nonprofit milk banks is safe from Ebola and Marburg viruses because the viruses are safely inactivated in human milk by standard North American pasteurization techniques.

A recent study found that the 2014-2015 West Africa Ebola epidemic was largely driven and sustained by “superspreadings” that were ubiquitous throughout the outbreak, and that age is an important demographic predictor for superspreading. The authors said their results highlight the importance of control measures targeted at potential superspreaders and enhance understanding of causes and consequences of superspreading for Ebola virus.

Ebola, and more recently Zika and yellow fever, have demonstrated that the world does not yet have a reliable or robust global system for preventing, detecting, and responding to disease outbreaks, according to an analysis in BMJ.

Ebola virus strains can be generated that replicate and cause disease within new host rodent species, according to a bioinformatics study, raising concerns that few mutations may result in novel human pathogenic Ebola viruses.

A study in Sierra Leone using a new highly specific and sensitive assay found that asymptomatic infection with Ebola virus was uncommon despite high exposure. The authors said “low prevalence suggests asymptomatic infection contributes little to herd immunity in Ebola, and even if infectious, would account for few transmissions.”

Malaria parasite coinfection was common in patients presenting to Ebola Treatment Units in Sierra Leone, according to a study in The Lancet Infectious Diseases, and conferred an increased mortality risk in patients infected with Ebola virus, supporting empirical malaria treatment in Ebola Treatment Units. The authors said high mortality among patients without Ebola virus disease or malaria suggests expanded testing and treatment might improve care in future Ebola epidemics.

[email protected]

On Twitter @richpizzi

Epilepsy Research Requires Better Selection Algorithms

Epilepsy-related research studies that rely on medical claims data have significant limitations that can be improved by choosing better selection algorithms. When Moura et al performed a medical chart review of 1377 patients, they found that the best algorithms to identify people with epilepsy included diagnostic and prescription drug data, as well as current antiepileptic drug usage, the location of the site that patients received medical care, and the specialty of the physician providing that care.

Moura LM, Price M, Cole AJ, et al. Accuracy of claims-based algorithms for epilepsy research: Revealing the unseen performance of claims-based studies. Epilepsia. 2017; Feb 15. doi: 10.1111/epi.13691. [Epub ahead of print]

Epilepsy-related research studies that rely on medical claims data have significant limitations that can be improved by choosing better selection algorithms. When Moura et al performed a medical chart review of 1377 patients, they found that the best algorithms to identify people with epilepsy included diagnostic and prescription drug data, as well as current antiepileptic drug usage, the location of the site that patients received medical care, and the specialty of the physician providing that care.

Moura LM, Price M, Cole AJ, et al. Accuracy of claims-based algorithms for epilepsy research: Revealing the unseen performance of claims-based studies. Epilepsia. 2017; Feb 15. doi: 10.1111/epi.13691. [Epub ahead of print]

Epilepsy-related research studies that rely on medical claims data have significant limitations that can be improved by choosing better selection algorithms. When Moura et al performed a medical chart review of 1377 patients, they found that the best algorithms to identify people with epilepsy included diagnostic and prescription drug data, as well as current antiepileptic drug usage, the location of the site that patients received medical care, and the specialty of the physician providing that care.

Moura LM, Price M, Cole AJ, et al. Accuracy of claims-based algorithms for epilepsy research: Revealing the unseen performance of claims-based studies. Epilepsia. 2017; Feb 15. doi: 10.1111/epi.13691. [Epub ahead of print]

Self-Management Skills Vary Among People with Epilepsy

People with epilepsy vary widely in their self-management skills according to a survey of 172 patients with the disease. Using the Epilepsy Self-Management Scale, investigators found that respondents scored better on medication, seizure, and safety management when compared to lifestyle and information management (P<.01). The differences have implications for how patients are counseled and educated, according to Ramon Edmundo D. Bautista of the University of Florida Health Sciences Center.

Bautista RE. Understanding the self-management skills of persons with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;69:7-11.

People with epilepsy vary widely in their self-management skills according to a survey of 172 patients with the disease. Using the Epilepsy Self-Management Scale, investigators found that respondents scored better on medication, seizure, and safety management when compared to lifestyle and information management (P<.01). The differences have implications for how patients are counseled and educated, according to Ramon Edmundo D. Bautista of the University of Florida Health Sciences Center.

Bautista RE. Understanding the self-management skills of persons with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;69:7-11.

People with epilepsy vary widely in their self-management skills according to a survey of 172 patients with the disease. Using the Epilepsy Self-Management Scale, investigators found that respondents scored better on medication, seizure, and safety management when compared to lifestyle and information management (P<.01). The differences have implications for how patients are counseled and educated, according to Ramon Edmundo D. Bautista of the University of Florida Health Sciences Center.

Bautista RE. Understanding the self-management skills of persons with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;69:7-11.