User login

CPSTF: A lesser known, but valuable, resource for FPs

Family physicians have come to rely on the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for rigorous, evidence-based recommendations on the use of clinical preventive services. Still, many such services reach too few individuals who need them. And that’s where the less well known Community Preventive Services Task Force comes in. The CPSTF makes recommendations regarding public health interventions and ways to increase the use of preventive services in the clinical setting—eg, means of improving childhood immunization rates or increasing screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer.

To better understand how the CPSTF can serve as a resource to busy family physicians, it’s helpful to first understand a bit about the inner-workings of the CPSTF itself.

How CPSTF figures out what works

Formed in 1996, the CPSTF consists of 15 independent, nonfederal members with expertise in public health and preventive medicine, appointed by the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Task Force makes recommendations and develops guidance on which community-based health promotion and disease-prevention interventions work and which do not, based on available scientific evidence. The Task Force uses an evidence-based methodology similar to that of the USPSTF—ie, assessing systematic reviews of the evidence and tying recommendations to the strength of the evidence. However, the Task Force has only 3 levels of recommendations: recommend for, recommend against, and insufficient evidence to recommend.

Three CPSTF meetings are held each year, and a representative from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) attends as a liaison, along with liaisons from other organizations with an interest in the methods and recommendations. The CDC provides the CPSTF with technical and administrative support. However, the recommendations developed do not undergo review or approval by the CDC and are the sole responsibility of the Task Force.

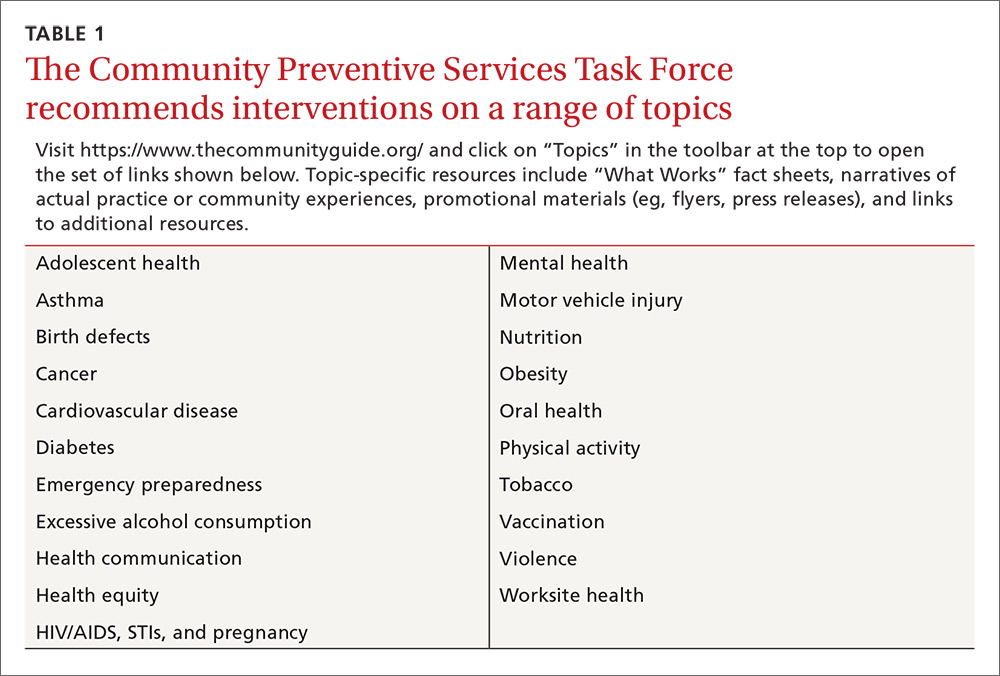

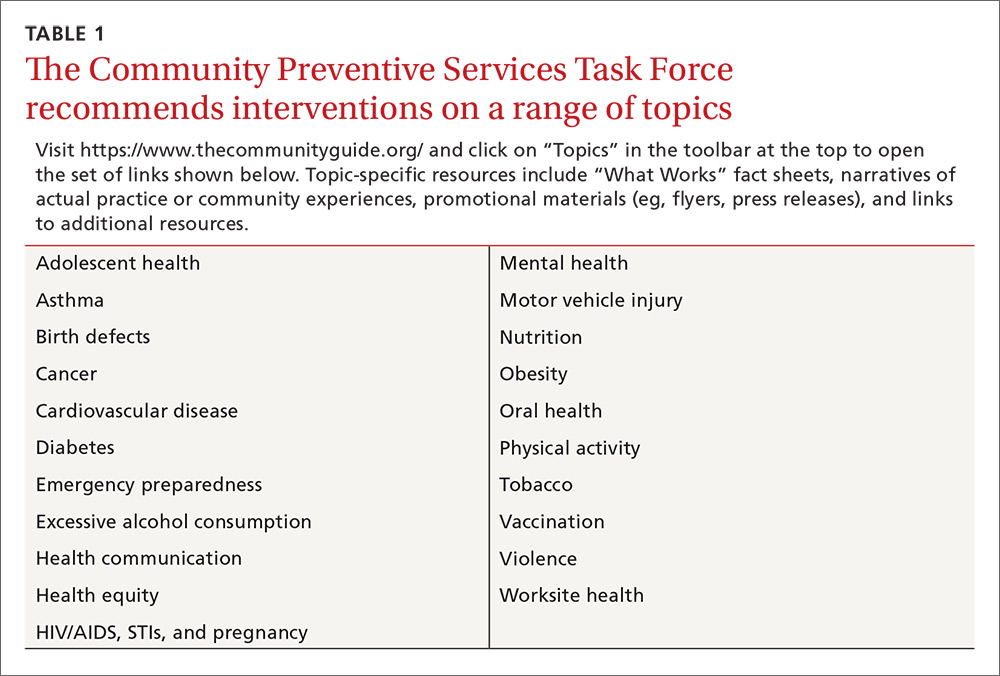

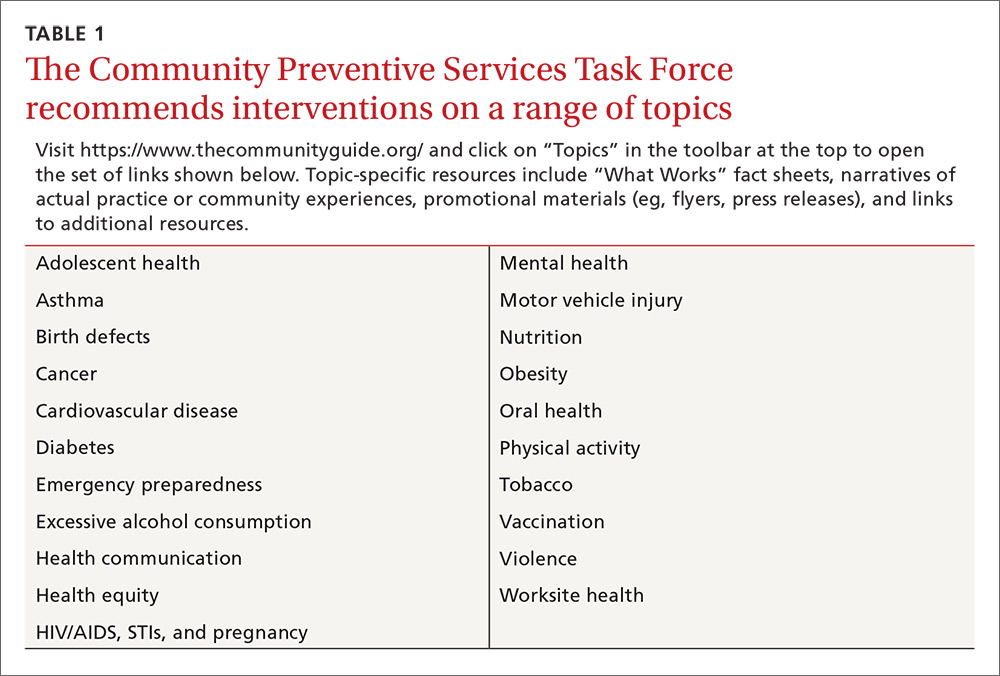

The recommendations made are contained in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, often called The Community Guide, which is available on the Task Force’s Web site at www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. The topics on which the CPSTF currently has recommendations are listed in TABLE 1. (Since community-wide recommendations are rarely subjected to controlled clinical trials, methods of assessing and ranking other forms of evidence are required. To learn more about how the CPSTF approaches this, see: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/our-methodology.)

Improving immunization rates

The topic of immunizations is an example of how synergistic the CPSTF recommendations can be with those from clinical organizations. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) makes recommendations on the use of vaccines.1 The CPSTF has developed a set of recommendations on how to increase the uptake of vaccines to improve rates of immunization.2 Interventions they recommend include vaccine requirements for attendance at preschool, primary and secondary school, and college; patient reminder and recall systems; patient and family incentives and rewards; providing vaccines at Women, Infants, and Children clinics, schools, work sites, and homes; standing orders for vaccine administration; physician reminders; physician assessments and feedback; reducing out-of-pocket expenses for vaccines; and using immunization registries. Just as important, the CPSTF identifies interventions that lack hard evidence to support their effectiveness.

Cancer screening works, but patient buy-in lags

The USPSTF recommends screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. And yet, despite the proven effectiveness of these screening tests in decreasing cancer mortality, many people do not get screened. The CPSTF has developed a set of implementation recommendations that are proven to increase the uptake of recommended cancer screening tests.3 These include:

- sending reminders to patients when screening tests are due

- providing one-on-one or group educational sessions

- providing videos and printed materials that describe screening tests and recommendations

- offering testing at locations and times that are convenient for patients

- offering on-site translation, transportation, patient navigators, and other administrative services to facilitate screening

- assessing provider performance and providing feedback.

CPSTF’s range of resources

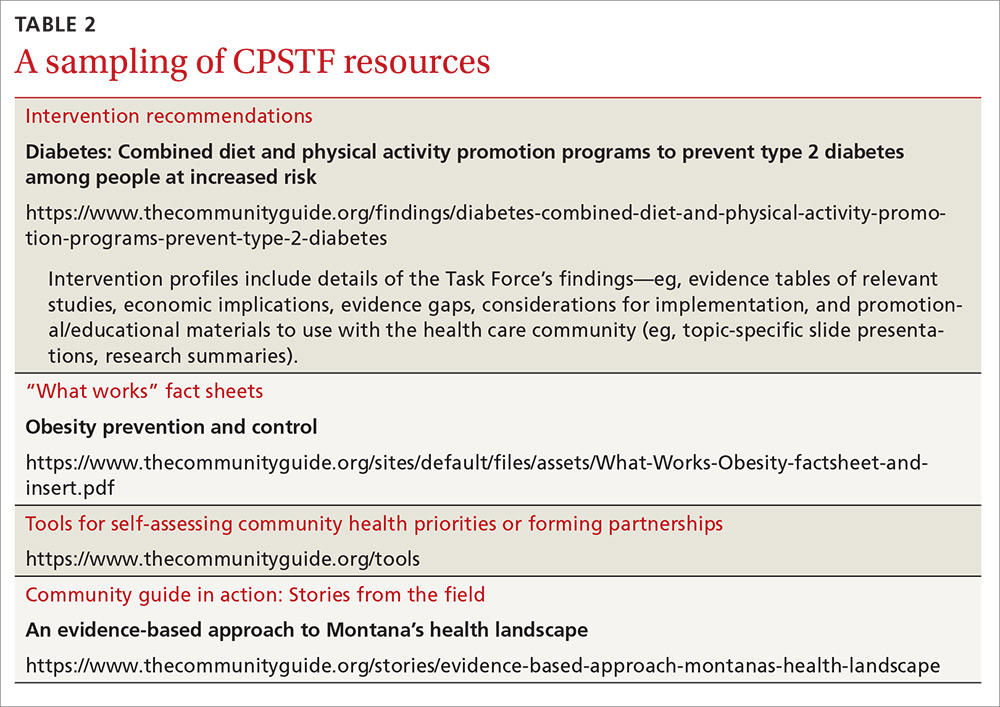

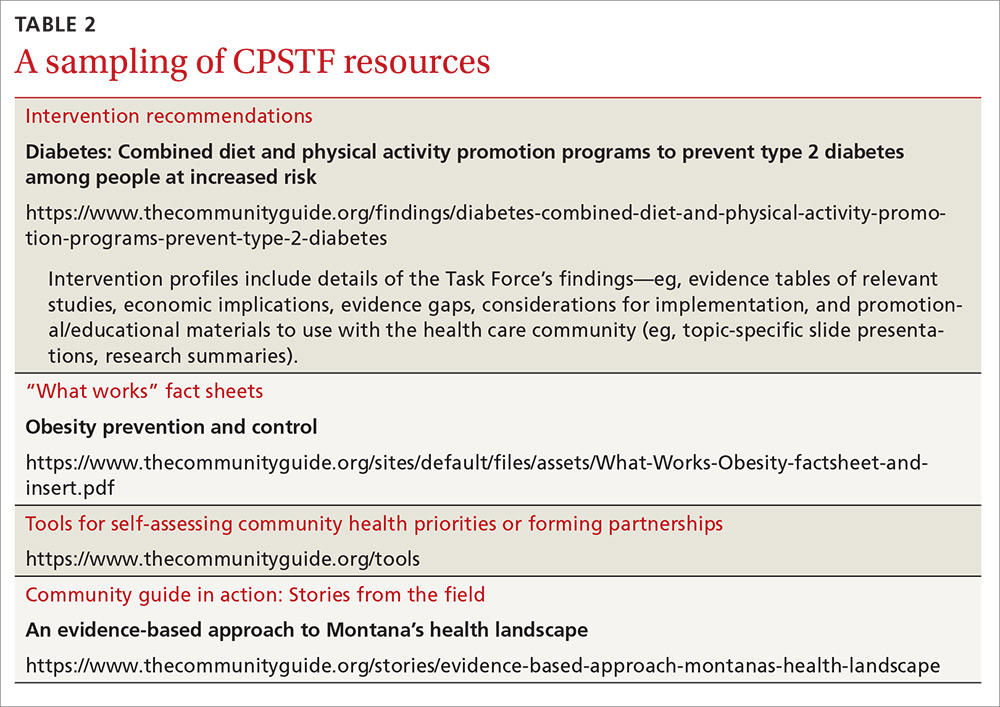

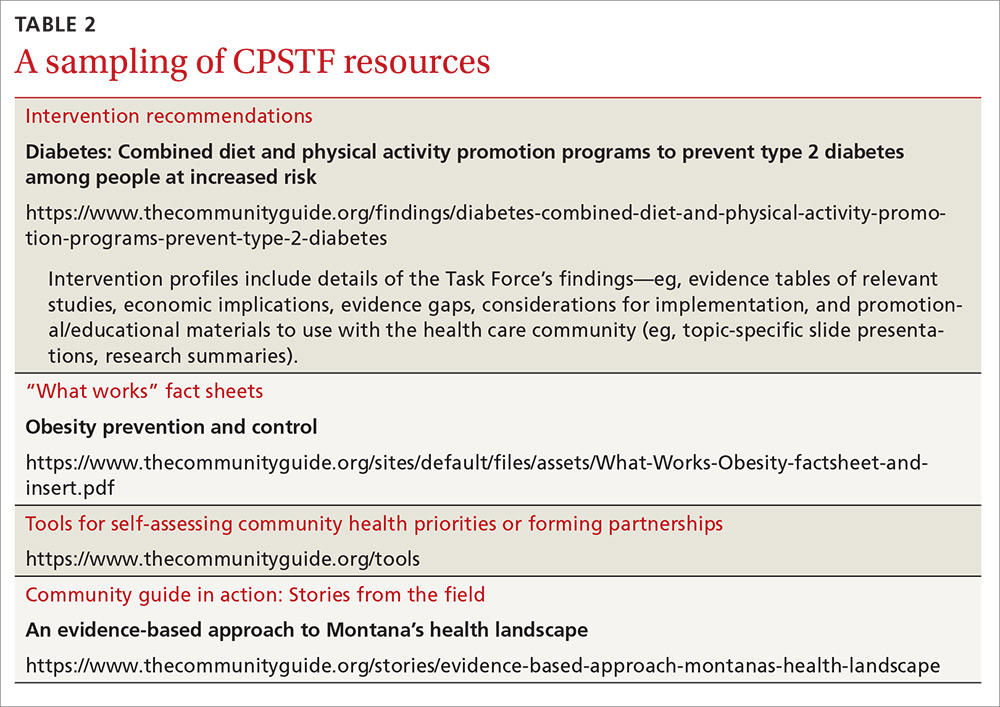

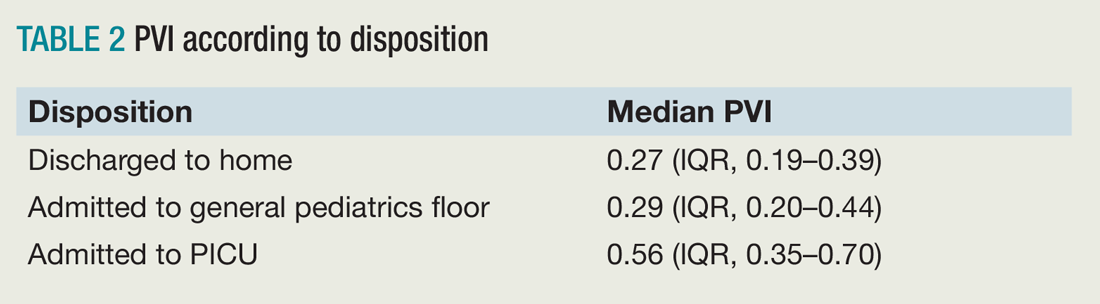

Resources provided by the CPSTF (TABLE 2) also include the following materials for physicians, patients, and policy makers:

- tools to assist communities in performing a community health assessment and in prioritizing health needs

- fact sheets on what works for specific populations or conditions. (One recently added fact sheet is a description of interventions to address the leading health problems that affect women.4)

- examples of how communities have used CPSTF recommendations to address a major health concern in their populations. (See “An immunization ‘success story’ from the field.”)

Tackling controversial social issues

Public health interventions are often politically charged, and the CPSTF at times makes recommendations that, while supported by evidence, raise objections from certain groups. One example is a recommendation for “comprehensive risk reduction interventions to promote behaviors that prevent or reduce the risk of pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).”5 These interventions may include a hierarchy of recommended behaviors that identifies abstinence as the best or preferred method, but also provides information about sexual risk reduction strategies. Abstinence-only education initiatives were rated as having insufficient evidence for effectiveness.6

Another example that falls in the controversial realm is a recommendation against “policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles from juvenile to adult criminal justice systems for the purpose of reducing violence, based on strong evidence that these laws and policies are associated with increased subsequent violent behavior among transferred youth.”7

And a third example is a recommendation for “the use of regulatory authority (eg, through licensing and zoning) to limit alcohol outlet density on the basis of sufficient evidence of a positive association between outlet density and excessive alcohol consumption and related harms.”8 The CPSTF also recommends increasing taxes on alcohol products to reduce excess alcohol consumption.9

SIDEBAR

An immunization “success story” from the field

Before 2009, the vaccination completion rates for 2-year-olds in Duval County, Florida, consistently ranked below the national target of 90%, with particularly low rates in Jacksonville. With the aim of improving vaccination rates—and not wanting to waste time “reinventing the wheel”—the Duval County Health Department (DCHD) turned to The Community Guide for interventions proven to work synergistically: system-based efforts (eg, client reminders, standing orders, clinic-based education) and community-based efforts (eg, staff outreach to clients, educational activities).

Checking the Florida Shots Registry, clinic staff identified infants and toddlers who were due for, or had missed, vaccinations. They sent monthly reminders to parents, urging them to make appointments. DCHD also provided parents with educational materials, vaccination schedules, and safety evidence to reinforce awareness of the need for immunizations.

At local clinics, DCHD trained staff to administer vaccines and established standing orders authorizing them to do so even in the absence of a physician or other approving practitioner.

DCHD also formed an immunization task force of community stakeholders that worked with hospitals to send nurses and physicians each week to immunize children at churches and other convenient locations.

Within one year, the rate of complete immunization for 2-year-olds rose from 75% to 90%—the national target. DCHD is now applying interventions from The Community Guide to discourage tobacco use and to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Read the full story at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/stories/good-shot-reaching-immunization-targets-duval-county.

Reducing health disparities

The CPSTF places a high priority on interventions that can reduce health disparities. Many of their topics of interest focus on interventions to reduce health inequities among racial and ethnic minorities and low-income populations. For instance, the Task Force recommends early childhood education, all-day kindergarten, and after-school academic programs as ways to improve health and decrease health disparities.10

Social determinants of health for individuals and populations are increasingly appreciated as issues to be addressed by physicians and health systems. The CPSTF can serve as a valuable evidence-based resource in these efforts, and their recommendations complement and build on those of other authoritative groups such as the USPSTF, ACIP, and AAFP.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP vaccine recommendations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. Accessed December 6, 2016.

2. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Vaccination. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination. Accessed December 6, 2016.

3. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Cancer prevention and control: cancer screening [fact sheet]. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/What-Works-Cancer-Screening-factsheet-and-insert.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Fo

5. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, other STIs, and teen pregnancy: group-based comprehensive risk reduction interventions for adolescents. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/hivaids-other-stis-and-teen-pregnancy-group-based-comprehensive-risk-reduction-interventions. Accessed December 6, 2016.

6. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, STIs and pregnancy. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/hivaids-stis-and-pregnancy. Accessed December 6, 2016.

7. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Violence: policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles to adult justice systems. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/violence-policies-facilitating-transfer-juveniles-adult-justice-systems. Accessed December 6, 2016.

8. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Alcohol – excessive consumption: regulation of alcohol outlet density. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-regulation-alcohol-outlet-density. Accessed December 6, 2016.

9. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Excessive alcohol consumption. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/excessive-alcohol-consumption. Accessed December 6, 2016.

10. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Health equity. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/health-equity. Accessed December 6, 2016.

Family physicians have come to rely on the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for rigorous, evidence-based recommendations on the use of clinical preventive services. Still, many such services reach too few individuals who need them. And that’s where the less well known Community Preventive Services Task Force comes in. The CPSTF makes recommendations regarding public health interventions and ways to increase the use of preventive services in the clinical setting—eg, means of improving childhood immunization rates or increasing screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer.

To better understand how the CPSTF can serve as a resource to busy family physicians, it’s helpful to first understand a bit about the inner-workings of the CPSTF itself.

How CPSTF figures out what works

Formed in 1996, the CPSTF consists of 15 independent, nonfederal members with expertise in public health and preventive medicine, appointed by the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Task Force makes recommendations and develops guidance on which community-based health promotion and disease-prevention interventions work and which do not, based on available scientific evidence. The Task Force uses an evidence-based methodology similar to that of the USPSTF—ie, assessing systematic reviews of the evidence and tying recommendations to the strength of the evidence. However, the Task Force has only 3 levels of recommendations: recommend for, recommend against, and insufficient evidence to recommend.

Three CPSTF meetings are held each year, and a representative from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) attends as a liaison, along with liaisons from other organizations with an interest in the methods and recommendations. The CDC provides the CPSTF with technical and administrative support. However, the recommendations developed do not undergo review or approval by the CDC and are the sole responsibility of the Task Force.

The recommendations made are contained in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, often called The Community Guide, which is available on the Task Force’s Web site at www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. The topics on which the CPSTF currently has recommendations are listed in TABLE 1. (Since community-wide recommendations are rarely subjected to controlled clinical trials, methods of assessing and ranking other forms of evidence are required. To learn more about how the CPSTF approaches this, see: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/our-methodology.)

Improving immunization rates

The topic of immunizations is an example of how synergistic the CPSTF recommendations can be with those from clinical organizations. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) makes recommendations on the use of vaccines.1 The CPSTF has developed a set of recommendations on how to increase the uptake of vaccines to improve rates of immunization.2 Interventions they recommend include vaccine requirements for attendance at preschool, primary and secondary school, and college; patient reminder and recall systems; patient and family incentives and rewards; providing vaccines at Women, Infants, and Children clinics, schools, work sites, and homes; standing orders for vaccine administration; physician reminders; physician assessments and feedback; reducing out-of-pocket expenses for vaccines; and using immunization registries. Just as important, the CPSTF identifies interventions that lack hard evidence to support their effectiveness.

Cancer screening works, but patient buy-in lags

The USPSTF recommends screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. And yet, despite the proven effectiveness of these screening tests in decreasing cancer mortality, many people do not get screened. The CPSTF has developed a set of implementation recommendations that are proven to increase the uptake of recommended cancer screening tests.3 These include:

- sending reminders to patients when screening tests are due

- providing one-on-one or group educational sessions

- providing videos and printed materials that describe screening tests and recommendations

- offering testing at locations and times that are convenient for patients

- offering on-site translation, transportation, patient navigators, and other administrative services to facilitate screening

- assessing provider performance and providing feedback.

CPSTF’s range of resources

Resources provided by the CPSTF (TABLE 2) also include the following materials for physicians, patients, and policy makers:

- tools to assist communities in performing a community health assessment and in prioritizing health needs

- fact sheets on what works for specific populations or conditions. (One recently added fact sheet is a description of interventions to address the leading health problems that affect women.4)

- examples of how communities have used CPSTF recommendations to address a major health concern in their populations. (See “An immunization ‘success story’ from the field.”)

Tackling controversial social issues

Public health interventions are often politically charged, and the CPSTF at times makes recommendations that, while supported by evidence, raise objections from certain groups. One example is a recommendation for “comprehensive risk reduction interventions to promote behaviors that prevent or reduce the risk of pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).”5 These interventions may include a hierarchy of recommended behaviors that identifies abstinence as the best or preferred method, but also provides information about sexual risk reduction strategies. Abstinence-only education initiatives were rated as having insufficient evidence for effectiveness.6

Another example that falls in the controversial realm is a recommendation against “policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles from juvenile to adult criminal justice systems for the purpose of reducing violence, based on strong evidence that these laws and policies are associated with increased subsequent violent behavior among transferred youth.”7

And a third example is a recommendation for “the use of regulatory authority (eg, through licensing and zoning) to limit alcohol outlet density on the basis of sufficient evidence of a positive association between outlet density and excessive alcohol consumption and related harms.”8 The CPSTF also recommends increasing taxes on alcohol products to reduce excess alcohol consumption.9

SIDEBAR

An immunization “success story” from the field

Before 2009, the vaccination completion rates for 2-year-olds in Duval County, Florida, consistently ranked below the national target of 90%, with particularly low rates in Jacksonville. With the aim of improving vaccination rates—and not wanting to waste time “reinventing the wheel”—the Duval County Health Department (DCHD) turned to The Community Guide for interventions proven to work synergistically: system-based efforts (eg, client reminders, standing orders, clinic-based education) and community-based efforts (eg, staff outreach to clients, educational activities).

Checking the Florida Shots Registry, clinic staff identified infants and toddlers who were due for, or had missed, vaccinations. They sent monthly reminders to parents, urging them to make appointments. DCHD also provided parents with educational materials, vaccination schedules, and safety evidence to reinforce awareness of the need for immunizations.

At local clinics, DCHD trained staff to administer vaccines and established standing orders authorizing them to do so even in the absence of a physician or other approving practitioner.

DCHD also formed an immunization task force of community stakeholders that worked with hospitals to send nurses and physicians each week to immunize children at churches and other convenient locations.

Within one year, the rate of complete immunization for 2-year-olds rose from 75% to 90%—the national target. DCHD is now applying interventions from The Community Guide to discourage tobacco use and to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Read the full story at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/stories/good-shot-reaching-immunization-targets-duval-county.

Reducing health disparities

The CPSTF places a high priority on interventions that can reduce health disparities. Many of their topics of interest focus on interventions to reduce health inequities among racial and ethnic minorities and low-income populations. For instance, the Task Force recommends early childhood education, all-day kindergarten, and after-school academic programs as ways to improve health and decrease health disparities.10

Social determinants of health for individuals and populations are increasingly appreciated as issues to be addressed by physicians and health systems. The CPSTF can serve as a valuable evidence-based resource in these efforts, and their recommendations complement and build on those of other authoritative groups such as the USPSTF, ACIP, and AAFP.

Family physicians have come to rely on the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for rigorous, evidence-based recommendations on the use of clinical preventive services. Still, many such services reach too few individuals who need them. And that’s where the less well known Community Preventive Services Task Force comes in. The CPSTF makes recommendations regarding public health interventions and ways to increase the use of preventive services in the clinical setting—eg, means of improving childhood immunization rates or increasing screening for cervical, breast, and colon cancer.

To better understand how the CPSTF can serve as a resource to busy family physicians, it’s helpful to first understand a bit about the inner-workings of the CPSTF itself.

How CPSTF figures out what works

Formed in 1996, the CPSTF consists of 15 independent, nonfederal members with expertise in public health and preventive medicine, appointed by the Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Task Force makes recommendations and develops guidance on which community-based health promotion and disease-prevention interventions work and which do not, based on available scientific evidence. The Task Force uses an evidence-based methodology similar to that of the USPSTF—ie, assessing systematic reviews of the evidence and tying recommendations to the strength of the evidence. However, the Task Force has only 3 levels of recommendations: recommend for, recommend against, and insufficient evidence to recommend.

Three CPSTF meetings are held each year, and a representative from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) attends as a liaison, along with liaisons from other organizations with an interest in the methods and recommendations. The CDC provides the CPSTF with technical and administrative support. However, the recommendations developed do not undergo review or approval by the CDC and are the sole responsibility of the Task Force.

The recommendations made are contained in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, often called The Community Guide, which is available on the Task Force’s Web site at www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. The topics on which the CPSTF currently has recommendations are listed in TABLE 1. (Since community-wide recommendations are rarely subjected to controlled clinical trials, methods of assessing and ranking other forms of evidence are required. To learn more about how the CPSTF approaches this, see: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/our-methodology.)

Improving immunization rates

The topic of immunizations is an example of how synergistic the CPSTF recommendations can be with those from clinical organizations. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) makes recommendations on the use of vaccines.1 The CPSTF has developed a set of recommendations on how to increase the uptake of vaccines to improve rates of immunization.2 Interventions they recommend include vaccine requirements for attendance at preschool, primary and secondary school, and college; patient reminder and recall systems; patient and family incentives and rewards; providing vaccines at Women, Infants, and Children clinics, schools, work sites, and homes; standing orders for vaccine administration; physician reminders; physician assessments and feedback; reducing out-of-pocket expenses for vaccines; and using immunization registries. Just as important, the CPSTF identifies interventions that lack hard evidence to support their effectiveness.

Cancer screening works, but patient buy-in lags

The USPSTF recommends screening for breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer. And yet, despite the proven effectiveness of these screening tests in decreasing cancer mortality, many people do not get screened. The CPSTF has developed a set of implementation recommendations that are proven to increase the uptake of recommended cancer screening tests.3 These include:

- sending reminders to patients when screening tests are due

- providing one-on-one or group educational sessions

- providing videos and printed materials that describe screening tests and recommendations

- offering testing at locations and times that are convenient for patients

- offering on-site translation, transportation, patient navigators, and other administrative services to facilitate screening

- assessing provider performance and providing feedback.

CPSTF’s range of resources

Resources provided by the CPSTF (TABLE 2) also include the following materials for physicians, patients, and policy makers:

- tools to assist communities in performing a community health assessment and in prioritizing health needs

- fact sheets on what works for specific populations or conditions. (One recently added fact sheet is a description of interventions to address the leading health problems that affect women.4)

- examples of how communities have used CPSTF recommendations to address a major health concern in their populations. (See “An immunization ‘success story’ from the field.”)

Tackling controversial social issues

Public health interventions are often politically charged, and the CPSTF at times makes recommendations that, while supported by evidence, raise objections from certain groups. One example is a recommendation for “comprehensive risk reduction interventions to promote behaviors that prevent or reduce the risk of pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).”5 These interventions may include a hierarchy of recommended behaviors that identifies abstinence as the best or preferred method, but also provides information about sexual risk reduction strategies. Abstinence-only education initiatives were rated as having insufficient evidence for effectiveness.6

Another example that falls in the controversial realm is a recommendation against “policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles from juvenile to adult criminal justice systems for the purpose of reducing violence, based on strong evidence that these laws and policies are associated with increased subsequent violent behavior among transferred youth.”7

And a third example is a recommendation for “the use of regulatory authority (eg, through licensing and zoning) to limit alcohol outlet density on the basis of sufficient evidence of a positive association between outlet density and excessive alcohol consumption and related harms.”8 The CPSTF also recommends increasing taxes on alcohol products to reduce excess alcohol consumption.9

SIDEBAR

An immunization “success story” from the field

Before 2009, the vaccination completion rates for 2-year-olds in Duval County, Florida, consistently ranked below the national target of 90%, with particularly low rates in Jacksonville. With the aim of improving vaccination rates—and not wanting to waste time “reinventing the wheel”—the Duval County Health Department (DCHD) turned to The Community Guide for interventions proven to work synergistically: system-based efforts (eg, client reminders, standing orders, clinic-based education) and community-based efforts (eg, staff outreach to clients, educational activities).

Checking the Florida Shots Registry, clinic staff identified infants and toddlers who were due for, or had missed, vaccinations. They sent monthly reminders to parents, urging them to make appointments. DCHD also provided parents with educational materials, vaccination schedules, and safety evidence to reinforce awareness of the need for immunizations.

At local clinics, DCHD trained staff to administer vaccines and established standing orders authorizing them to do so even in the absence of a physician or other approving practitioner.

DCHD also formed an immunization task force of community stakeholders that worked with hospitals to send nurses and physicians each week to immunize children at churches and other convenient locations.

Within one year, the rate of complete immunization for 2-year-olds rose from 75% to 90%—the national target. DCHD is now applying interventions from The Community Guide to discourage tobacco use and to prevent sexually transmitted infections.

Read the full story at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/stories/good-shot-reaching-immunization-targets-duval-county.

Reducing health disparities

The CPSTF places a high priority on interventions that can reduce health disparities. Many of their topics of interest focus on interventions to reduce health inequities among racial and ethnic minorities and low-income populations. For instance, the Task Force recommends early childhood education, all-day kindergarten, and after-school academic programs as ways to improve health and decrease health disparities.10

Social determinants of health for individuals and populations are increasingly appreciated as issues to be addressed by physicians and health systems. The CPSTF can serve as a valuable evidence-based resource in these efforts, and their recommendations complement and build on those of other authoritative groups such as the USPSTF, ACIP, and AAFP.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP vaccine recommendations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. Accessed December 6, 2016.

2. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Vaccination. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination. Accessed December 6, 2016.

3. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Cancer prevention and control: cancer screening [fact sheet]. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/What-Works-Cancer-Screening-factsheet-and-insert.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Fo

5. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, other STIs, and teen pregnancy: group-based comprehensive risk reduction interventions for adolescents. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/hivaids-other-stis-and-teen-pregnancy-group-based-comprehensive-risk-reduction-interventions. Accessed December 6, 2016.

6. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, STIs and pregnancy. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/hivaids-stis-and-pregnancy. Accessed December 6, 2016.

7. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Violence: policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles to adult justice systems. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/violence-policies-facilitating-transfer-juveniles-adult-justice-systems. Accessed December 6, 2016.

8. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Alcohol – excessive consumption: regulation of alcohol outlet density. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-regulation-alcohol-outlet-density. Accessed December 6, 2016.

9. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Excessive alcohol consumption. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/excessive-alcohol-consumption. Accessed December 6, 2016.

10. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Health equity. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/health-equity. Accessed December 6, 2016.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP vaccine recommendations. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/acip-recs/index.html. Accessed December 6, 2016.

2. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Vaccination. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/vaccination. Accessed December 6, 2016.

3. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Cancer prevention and control: cancer screening [fact sheet]. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/sites/default/files/assets/What-Works-Cancer-Screening-factsheet-and-insert.pdf. Accessed December 6, 2016.

4. Community Preventive Services Task Fo

5. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, other STIs, and teen pregnancy: group-based comprehensive risk reduction interventions for adolescents. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/hivaids-other-stis-and-teen-pregnancy-group-based-comprehensive-risk-reduction-interventions. Accessed December 6, 2016.

6. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. HIV/AIDS, STIs and pregnancy. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/hivaids-stis-and-pregnancy. Accessed December 6, 2016.

7. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Violence: policies facilitating the transfer of juveniles to adult justice systems. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/violence-policies-facilitating-transfer-juveniles-adult-justice-systems. Accessed December 6, 2016.

8. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Alcohol – excessive consumption: regulation of alcohol outlet density. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-regulation-alcohol-outlet-density. Accessed December 6, 2016.

9. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Excessive alcohol consumption. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/excessive-alcohol-consumption. Accessed December 6, 2016.

10. Community Preventive Services Task Force. The Community Guide. Health equity. Available at: https://www.thecommunityguide.org/topic/health-equity. Accessed December 6, 2016.

How in-office and ambulatory BP monitoring compare: A systematic review and meta-analysis

ABSTRACT

Purpose We performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office blood pressure (BP) measurement in a primary care setting, using ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

Methods We conducted a literature search for studies published up to December 2013 that included hypertensive patients receiving treatment in a primary care setting. We compared the mean office BP with readings obtained by ABPM. We summarized the diagnostic accuracy of office BP with respect to ABPM in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR), with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results Only 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and contained data to calculate the differences between the means of office and ambulatory BP measurements. Five were suitable for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios, and 4 contained sufficient extractable data for meta-analysis. Compared with ABPM (thresholds of 140/90 mm Hg for office BP; 130/80 mmHg for ABPM) in diagnosing uncontrolled BP, office BP measurement had a sensitivity of 81.9% (95% CI, 74.8%-87%) and specificity of 41.1% (95% CI, 35.1%-48.4%). Positive LR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.32-1.38), and the negative LR was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.37-0.53).

Conclusion Likelihood ratios show that isolated BP measurement in the office does not confirm or rule out the presence of poor BP control. Likelihood of underestimating or overestimating BP control is high when relying on in-office BP measurement alone.

A growing body of evidence supports more frequent use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension1 and to monitor blood pressure (BP) response to treatment.2 The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure has long accepted ABPM for diagnosis of hypertension,3 and many clinicians consider ABPM the reference standard for diagnosing true hypertension and for accurately assessing associated cardiovascular risk in adults, regardless of office BP readings.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends obtaining BP measurements outside the clinical setting to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension before starting treatment.5 The USPSTF also asserts that elevated 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP is consistently and significantly associated with stroke and other cardiovascular events independent of office BP readings and has greater predictive value than office monitoring.5 The USPSTF concludes that ABPM, because of its large evidence base, is the best confirmatory test for hypertension.6 The recommendation of the American Academy of Family Physicians is similar to that of the USPSTF.7

The challenge. Despite the considerable support for ABPM, this method of BP measurement is still not sufficiently integrated into primary care. And some guidelines, such as those of

But ABPM’s advantages are numerous. Ambulatory monitors, which can record BP for 24 hours, are typically programmed to take readings every 15 to 30 minutes, providing estimates of mean daytime and nighttime BP and revealing an individual’s circadian pattern of BP.8-10 Ambulatory BP values usually considered the uppermost limit of normal are 135/85 mm Hg (day), 120/70 mm Hg (night), and 130/80 mm Hg (24 hour).8

Office BP monitoring, usually performed manually by medical staff, has 2 main drawbacks: the well-known white-coat effect experienced by many patients, and the relatively small number of possible measurements. A more reliable in-office BP estimation of BP would require repeated measurements at each of several visits.

By comparing ABPM and office measurements, 4 clinical findings are possible: isolated clinic or office (white-coat) hypertension (ICH); isolated ambulatory (masked) hypertension (IAH); consistent normotension; or sustained hypertension. With ICH, BP is high in the office and normal with ABPM. With IAH, BP is normal in the office and high with ABPM. With consistent normotension and sustained hypertension, BP readings with both types of measurement agree.8,9

In patients being treated for hypertension, ICH leads to an overestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in overtreatment. The cardiovascular risk, although controversial, is usually lower than in patients diagnosed with sustained hypertension.11 IAH leads to an underestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in undertreatment; its associated cardiovascular risk is similar to that of sustained hypertension.12

Our research objective. We recently published a study conducted with 137 hypertensive patients in a primary care center.13 Our conclusion was that in-office measurement of BP had insufficient clinical validity to be recommended as a sole method of monitoring BP control. In accurately classifying BP as controlled or uncontrolled, clinic measurement agreed with 24h-ABPM in just 64.2% of cases.13

In our present study, we performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office BP measurement in a primary care setting, using ABPM as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

METHODS

Most published studies comparing conventional office BP measurement with ABPM have been conducted with patients not taking antihypertensive medication. We excluded these studies and conducted a literature search for studies published up to December 2013 that included hypertensive patients receiving treatment in a primary care setting.

We searched Medline (from 1950 onward) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. For the Medline search, we combined keywords for office BP, hypertension, and ambulatory BP with keywords for outpatient setting and primary care, using the following syntax: (((“clinic blood pressure” OR “office blood pressure” OR “casual blood pressure”))) AND (“hypertension” AND ((((“24-h ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “24 h ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “24 hour ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory”[Mesh]) AND ((((((“outpatient setting”) OR “primary care”) OR “family care”) OR “family physician”) OR “family practice”) OR “general practice”)). We chose studies published in English and reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified articles.

With the aim of identifying additional candidate studies, we reviewed the reference lists of eligible primary studies, narrative reviews, and systematic reviews. The studies were generally of good quality and used appropriate statistical methods. Only primary studies qualified for meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Acceptable studies had to be conducted in a primary care setting with patients being treated for hypertension, and had to provide data comparing office BP measurement with ABPM. We excluded studies in which participants were treated in the hospital, were untreated, or had not been diagnosed with hypertension.

The quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis was judged by 2 independent observers according to the following criteria: the clear classification and initial comparison of both measurements; explicit and defined diagnostic criteria; compliance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria; and clear and precise definition of outcome variables.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each included study: study population, number of patients included, age, gender distribution, number of measurements (ambulatory and office BP), equipment validation, mean office and ambulatory BP, and the period of ambulatory BP measurement. We included adult patients of all ages, and we compared the mean office BP with those obtained by ABPM in hypertensive patients.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For each study, we summarized the diagnostic accuracy of office BP with respect to ABPM in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), with the 95% confidence interval (CI), if available. If these rates were not directly reported in the original papers, we used the published data to calculate them.

We used the R v2.15.1 software with the “mada” package for meta-analysis.14 Although a bivariate approach is preferred for the meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy, it cannot be recommended if the number of primary studies to pool is too small,14 as happened in our case. Therefore, we used a univariate approach and pooled summary statistics for positive LR, negative LR, and the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with their 95% confidence intervals. We used the DerSimonian-Laird method to perform a random-effect meta-analysis. To explore heterogeneity between the studies, we used the Cochran’s Q heterogeneity test, I2 index, and Galbraith and L’Abbé plots.

RESULTS

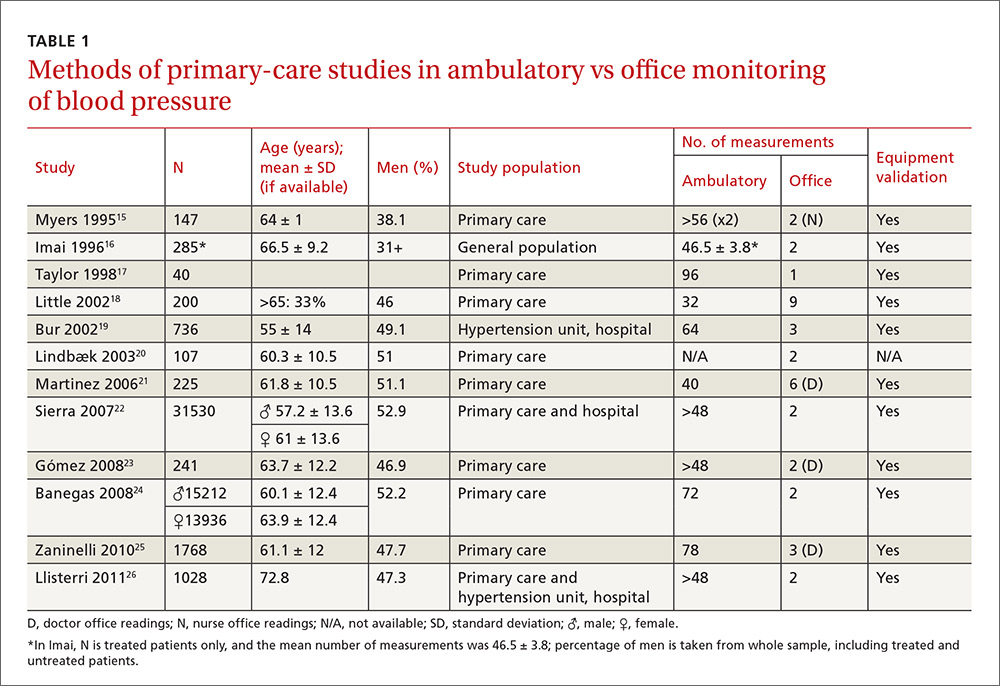

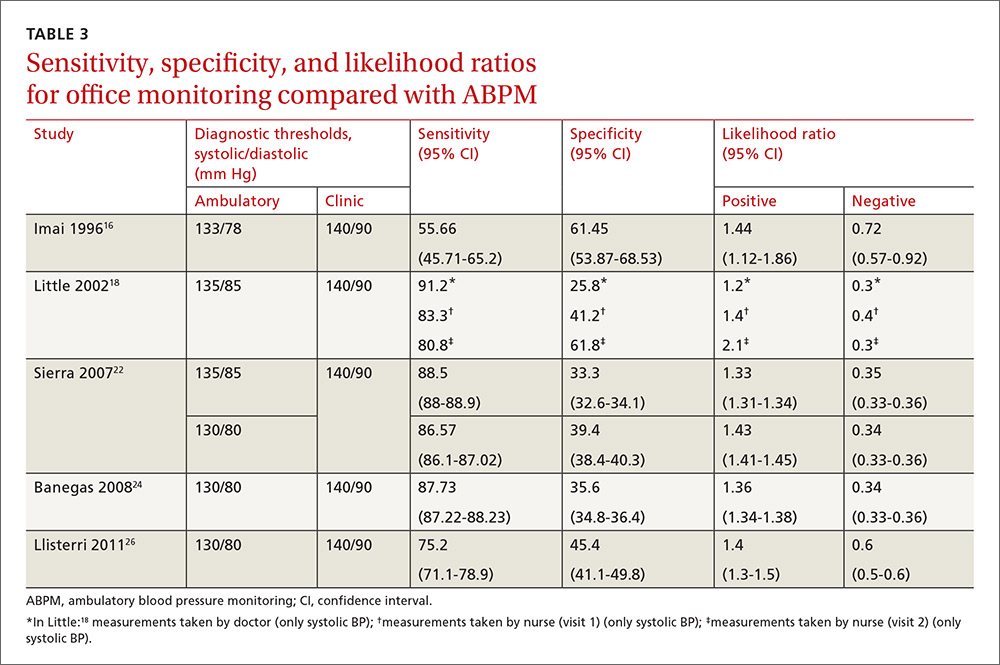

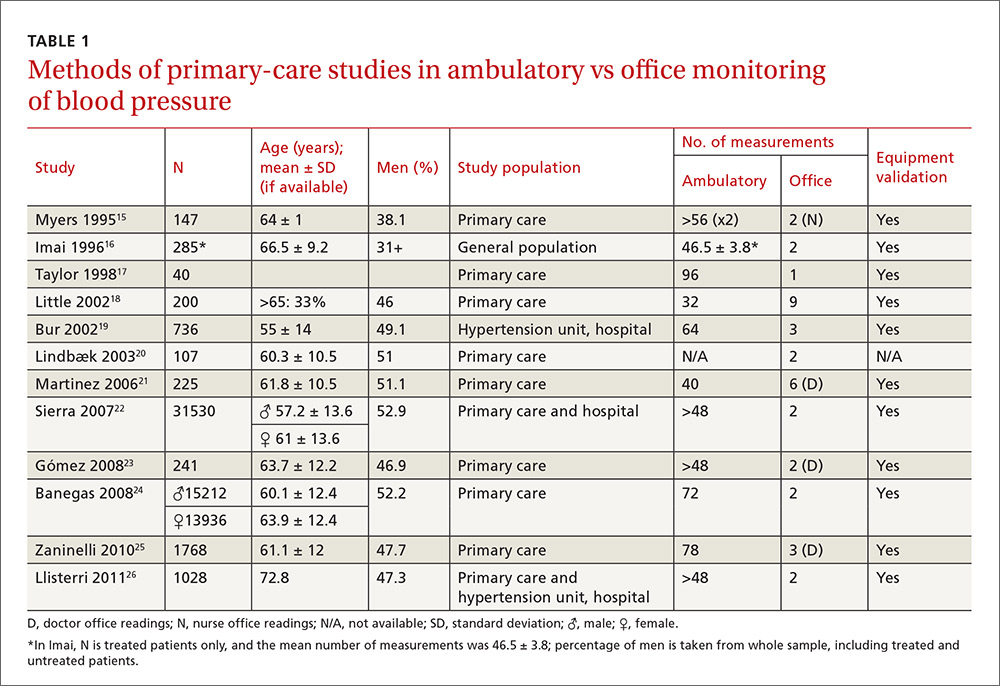

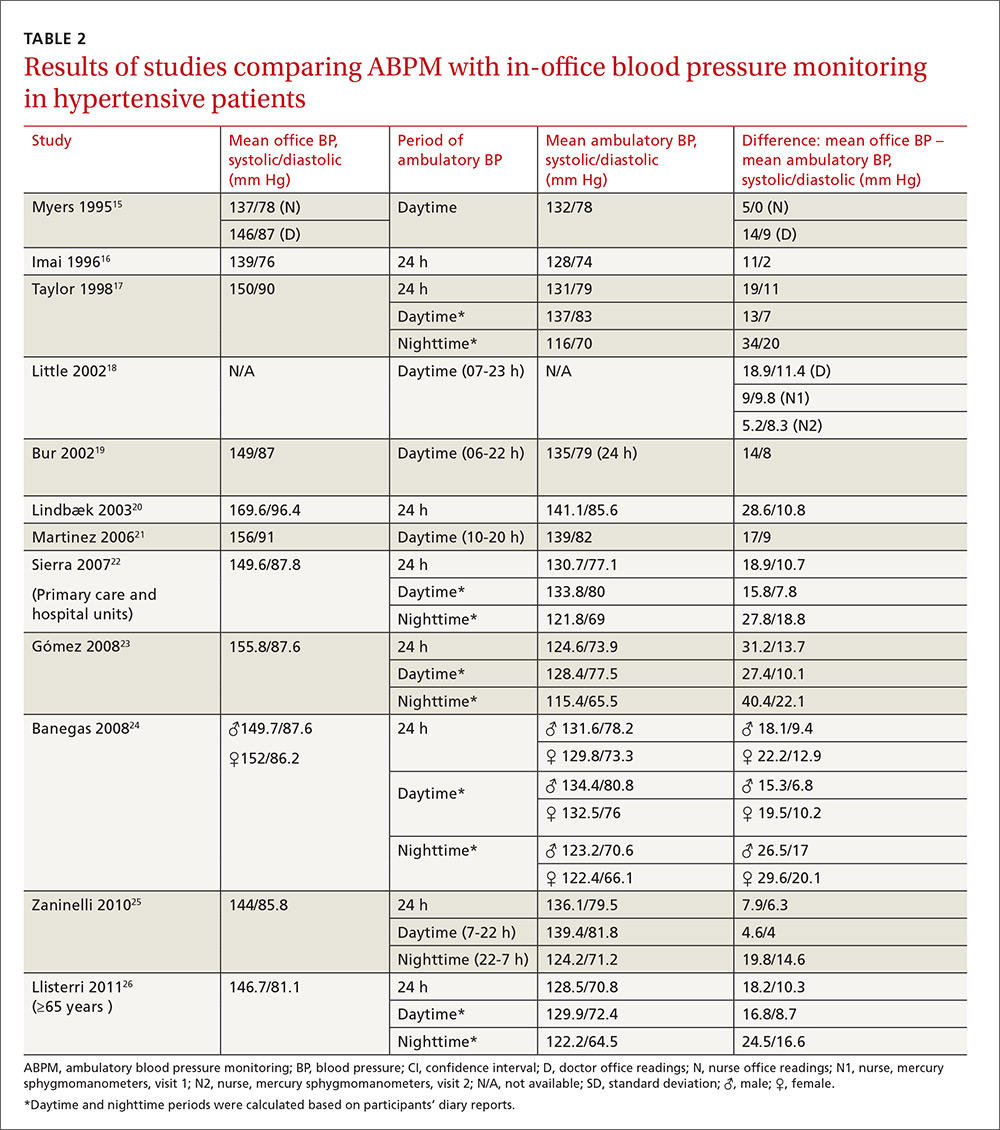

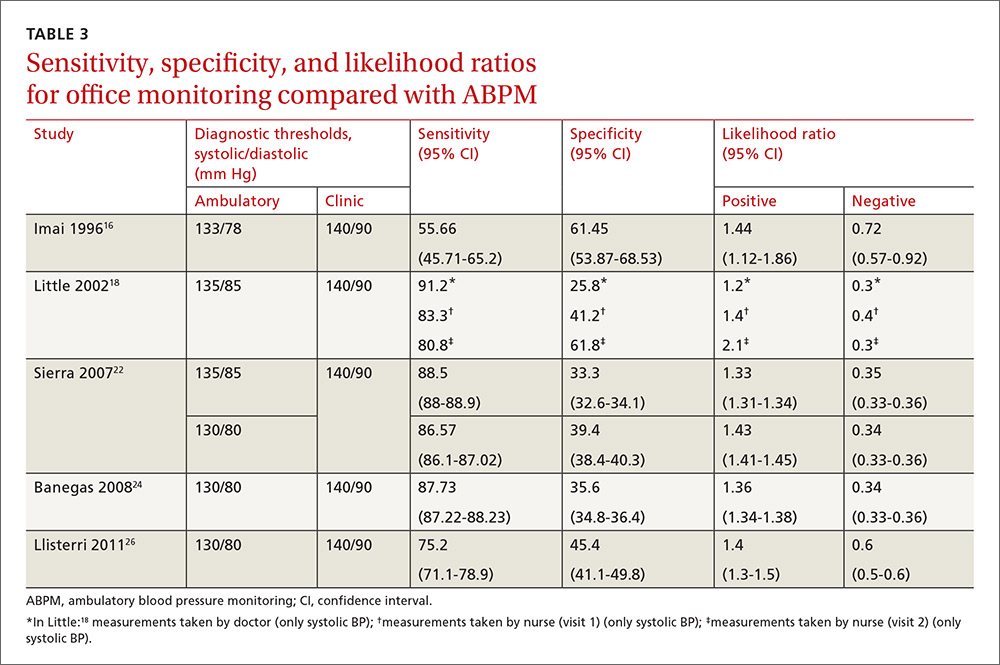

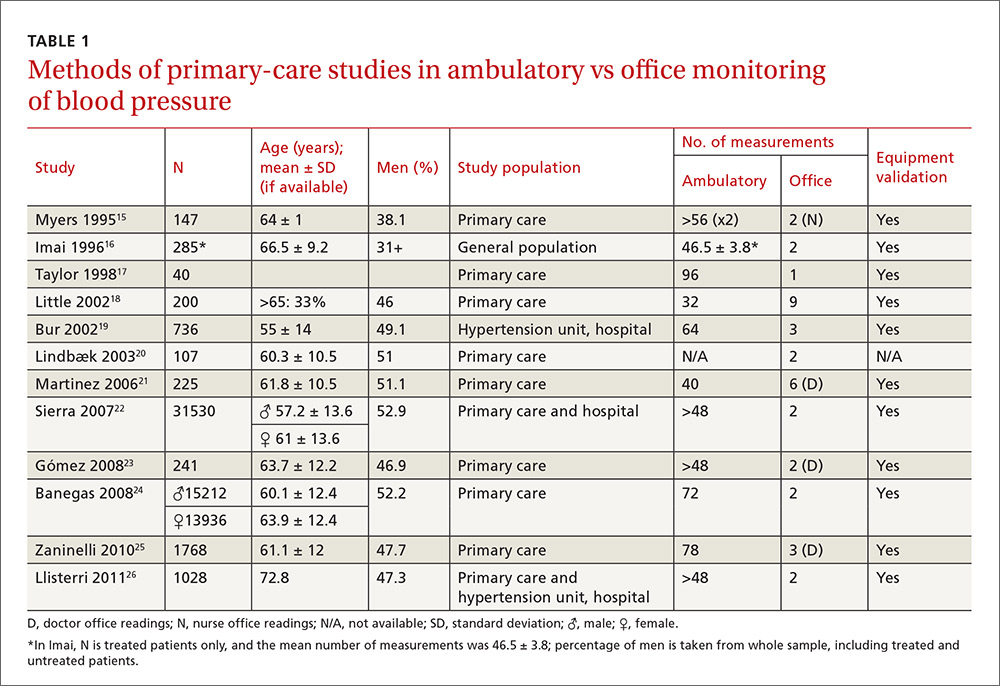

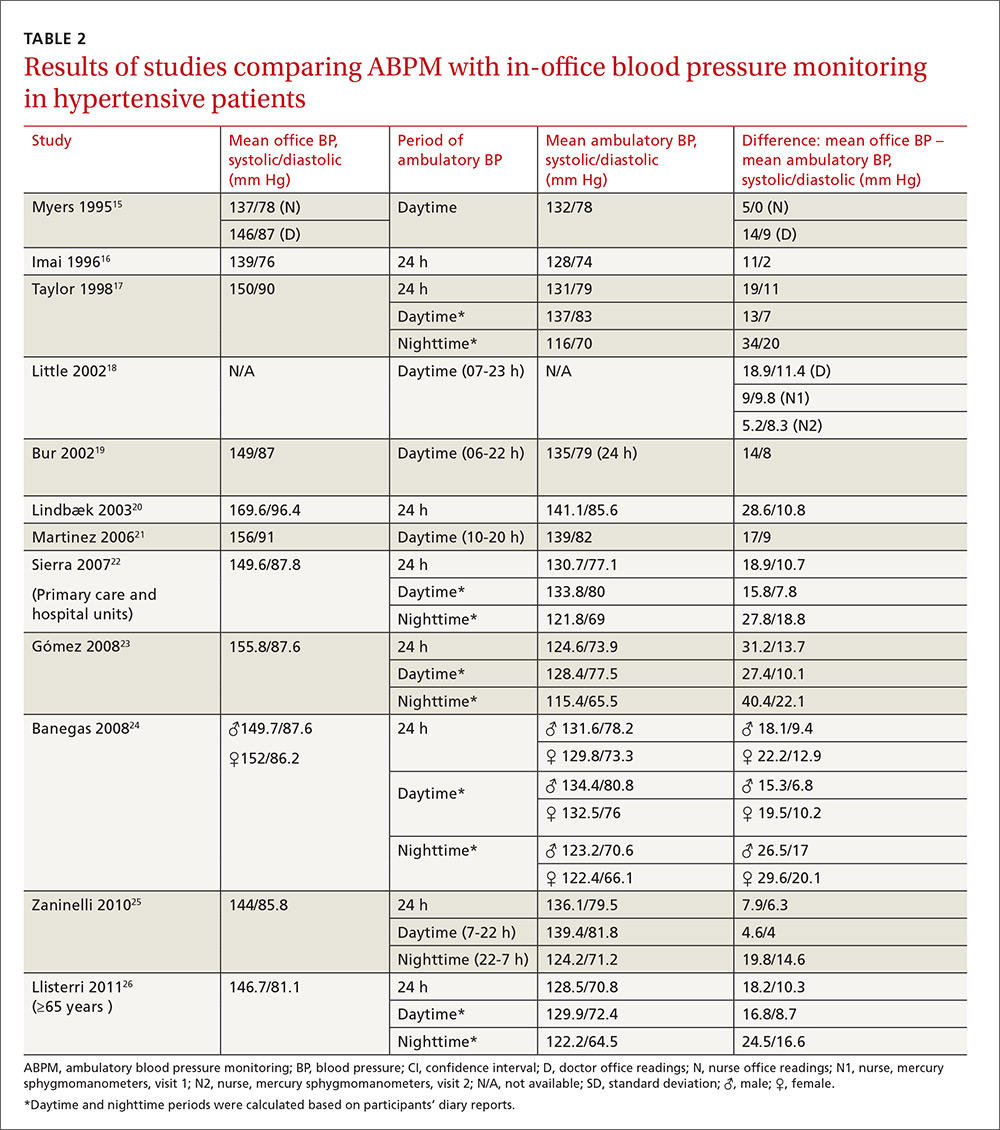

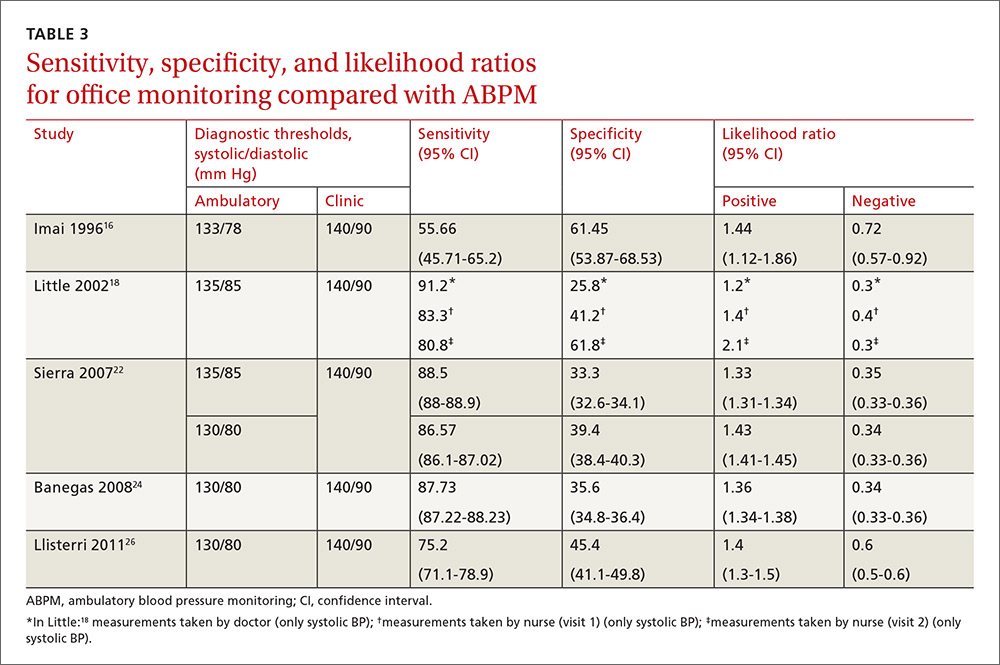

Our search identified 237 studies, only 12 of which met the inclusion criteria and contained data to calculate the differences between the means of office and ambulatory BP measurements (TABLES 1 AND 2).15-26 Of these 12 studies, 5 were suitable for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and LR (TABLE 3),16,18,22,24,26 and 4 contained sufficient extractable data for meta-analysis. The study by Little et al18 was not included in the meta-analysis, as the number of true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative results could not be deduced from published data.

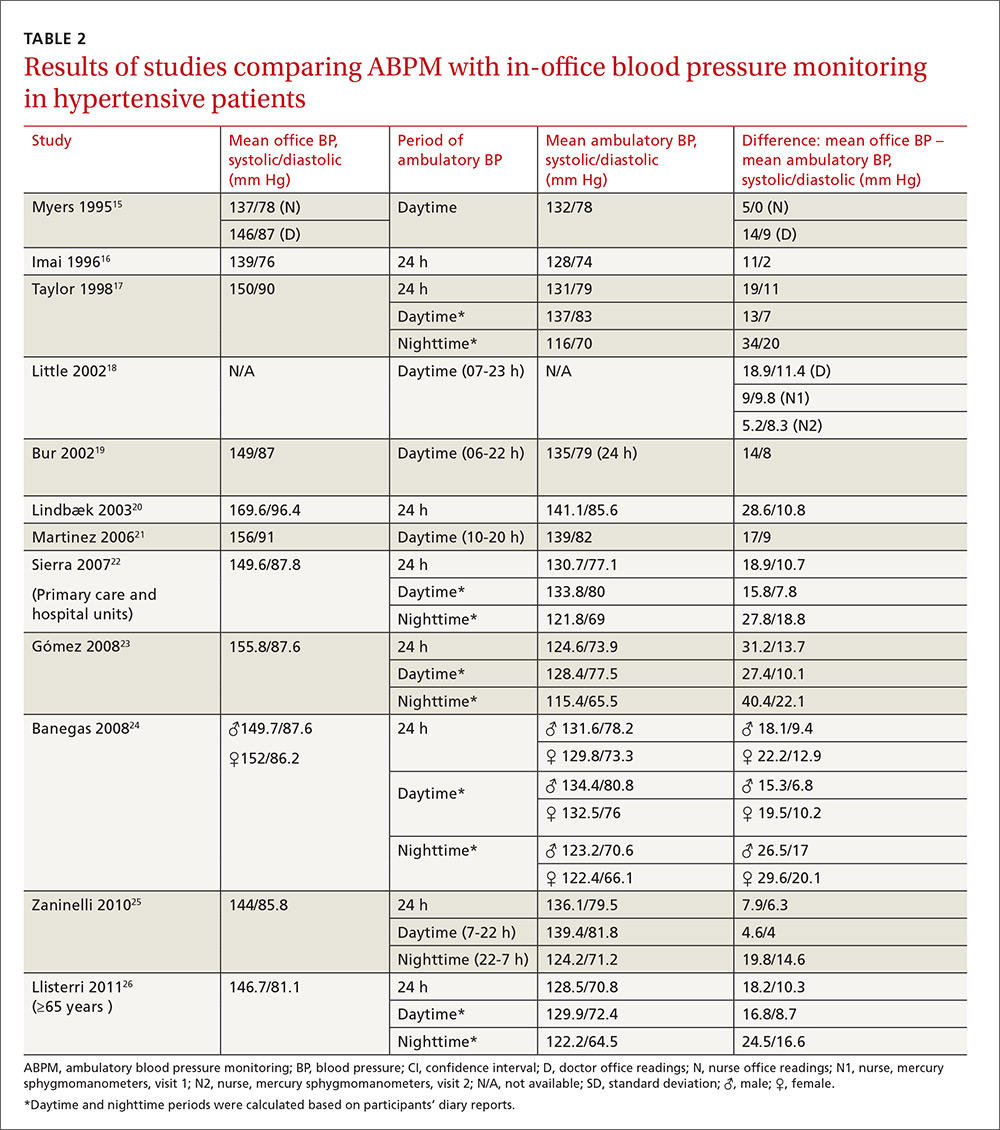

The studies differed in sample size (40-31,530), patient ages (mean, 55-72.8 years), sex (percentage of men, 31%-52.9%), and number of measurements for office BP (1-9) and ABPM (32-96) (TABLE 1),15-26 as well as in daytime and nighttime periods for ABPM and BP thresholds, and in differences between the mean office and ambulatory BPs (TABLE 2).15-26

In general, the mean office BP measurements were higher than those obtained with ABPM in any period—from 5/0 mm Hg to 27.4/10.1 mm Hg in the day, and from 7.9/6.3 mm Hg to 31.2/13.7 mm Hg over 24 hours (TABLE 2).15-26

Compared with ABPM in diagnosing uncontrolled BP, office BP measurement had a sensitivity of 55.7% to 91.2% and a specificity of 25.8% to 61.8% (depending on whether the measure was carried out by the doctor or nurse18); positive LR ranged from 1.2 to 1.4, and negative LR from 0.3 to 0.72 (TABLE 3).16,18,22,24,26

For meta-analysis, we pooled studies with the same thresholds (140/90 mm Hg for office BP; 130/80 mm Hg for ABPM), with diagnostic accuracy of office BP expressed as pooled positive and negative LR, and as pooled DOR. The meta-analysis revealed that the pooled positive LR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.32-1.38), and the pooled negative LR was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.37-0.53). The pooled DOR was 3.47 (95% CI, 3.02-3.98). Sensitivity was 81.9% (95% CI, 74.8%-87%) and specificity was 41.1% (95% CI, 35.1%-48.4%).

One study16 had a slightly different ambulatory diagnostic threshold (133/78 mm Hg), so we excluded it from a second meta-analysis. Results after the exclusion did not change significantly: positive LR was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.34-1.45); negative LR was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.33-0.44); and DOR was 3.77 (95% CI, 3.31-4.43).

In conclusion, the use of office-based BP readings in the outpatient clinic does not correlate well with ABPM. Therefore, caution must be used when making management decisions based solely on in-office readings of BP.

DISCUSSION

The European Society of Hypertension still regards office BP measurement as the gold standard in screening for, diagnosing, and managing hypertension. As previously mentioned, though, office measurements are usually handled by medical staff and can be compromised by the white-coat effect and a small number of measurements. The USPSTF now considers ABPM the reference standard in primary care to diagnose hypertension in adults, to corroborate or contradict office-based determinations of elevated BP (whether based on single or repeated-interval measurements), and to avoid overtreatment of individuals displaying elevated office BP yet proven normotensive by ABPM.4,7 The recommendation of the American Academy of Family Physicians is similar to that of the USPSTF.7 Therefore, evidence supports ABPM as the reference standard for confirming elevated office BP screening results to avoid misdiagnosis and overtreatment of individuals with isolated clinic hypertension.7

How office measurements stack up against ABPM

Checking the validity of decisions in clinical practice is extremely important for patient management. One of the tools used for decision-making is an estimate of the LR. We used the LR to assess the value of office BP measurement in determining controlled or uncontrolled BP. A high LR (eg, >10) indicates that the office BP can be used to rule in the disease (uncontrolled BP) with a high probability, while a low LR (eg, <0.1) could rule it out. An LR of around one indicates that the office BP measurement cannot rule the diagnosis of uncontrolled BP in or out.27 In our meta-analysis, the positive LR is 1.35 and negative LR is 0.44. Therefore, in treated hypertensive patients, an indication of uncontrolled BP as measured in the clinic does not confirm a diagnosis of uncontrolled BP (as judged by the reference standard of ABPM). On the other hand, the negative LR means that normal office BP does not rule out uncontrolled BP, which may be detected with ABPM. Consequently, the measurement of BP in the office does not change the degree of (un)certainty of adequate control of BP. This knowledge is important, to avoid overtreatment of white coat hypertension and undertreatment of masked cases.

As previously mentioned, we reported similar results in a study designed to determine the validity of office BP measurement in a primary care setting compared with ABPM.13 In that paper, the level of agreement between both methods was poor, indicating that clinic measurements could not be recommended as a single method of BP control in hypertensive patients.

The use of ABPM in diagnosing hypertension is likely to increase as a consequence of some guideline updates.2 Our study emphasizes the importance of their use in the control of hypertensive patients.

Another published meta-analysis1 investigated the validity of office BP for the diagnosis of hypertension in untreated patients, with diagnostic thresholds for arterial hypertension set at 140/90 mm Hg for office measurement, and 135/85 mm Hg for ABPM. In that paper, the sensitivity of office BP was 74.6% (95% CI, 60.7-84.8) and the specificity was 74.6% (95% CI, 47.9-90.4).

In our present study carried out with hypertensive patients receiving treatment, we obtained a slightly higher sensitivity value of 81.9% (within the CI of this meta-analysis) and a lower specificity of 41.1%. Therefore, the discordance between office BP and ABPM seems to be similar for the diagnosis of hypertension and the classification of hypertension as being well or poorly controlled. This confirms the low validity of the office BP, both for diagnosis and monitoring of hypertensive patients.

Strengths of our study. The study focused on (treated) hypertensive patients in a primary care setting, where hypertension is most often managed. It confirms that ABPM is indispensable to a good clinical practice.

Limitations of our study are those inherent to meta-analyses. The main weakness of our study is the paucity of data available regarding the utility of ABPM for monitoring BP control with treatment in a primary care setting. Other limitations are the variability in BP thresholds used, the number of measurements performed, and the ambulatory BP devices used. These differences could contribute to the observed heterogeneity.

Application of our results must take into account that we included only those studies performed in a primary care setting with treated hypertensive patients.

Moreover, this study was not designed to evaluate the consequences of over- and undertreatment of blood pressure, nor to address the accuracy of automated blood pressure machines or newer health and fitness devices.

Implications for practice, policy, or future research. Alternative monitoring methods are home BP self-measurement and automated 30-minute clinic BP measurement.28 However, ABPM provides us with unique information about the BP pattern (dipping or non-dipping), BP variability, and mean nighttime BP. This paper establishes that the measurement of BP in the office is not an accurate method to monitor BP control. ABPM should be incorporated in usual clinical practice in primary care. Although the consequences of ambulatory monitoring are not the focus of this study, we acknowledge that the decision to incorporate ABPM in clinical practice depends on the availability of ambulatory devices, proper training of health care workers, and a cost-effectiveness analysis of its use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sergio Reino-González, MD, PhD, Adormideras Primary Health Center, Poligono de Adormideras s/n. 15002 A Coruña, Spain; [email protected].

1. Hodgkinson J, Mant J, Martin U, et al. Relative effectiveness of clinic and home blood pressure monitoring compared with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in diagnosis of hypertension: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3621.

2. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG127. Accessed November 15, 2016.

3. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252.

4. Hermida RC, Smolensky MH, Ayala DE, et al. Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring (ABPM) as the reference standard for diagnosis of hypertension and assessment of vascular risk in adults. Chronobiol Int. 2015;32:1329-1342.

5. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

6. Piper MA, Evans CV

7. American Academy of Family Physicians. Hypertension. Available at: www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/hypertension.html. Accessed February 10, 2016.

8. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC Practice Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension. Blood Press. 2013;23:3-16.

9. Marin R, de la Sierra A, Armario P, et al. 2005 Spanish guidelines in diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension. Medicina Clínica. 2005;125:24-34.

10. Fagard RH, Celis H, Thijs L, et al. Daytime and nighttime blood pressure as predictors of death and cause-specific cardiovascular events in hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;51:55-61.

11. Sega R, Trocino G, Lanzarotti A, et al. Alterations of cardiac structure in patients with isolated office, ambulatory, or home hypertension: Data from the general population (Pressione Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni [PAMELA] Study). Circulation. 2001;104:1385-1392.

12. Verberk WJ, Kessels AG, de Leeuw PW. Prevalence, causes, and consequences of masked hypertension: a meta-analysis. Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:969-975.

13. Reino-González S, Pita-Fernández S, Cibiriain-Sola M, et al. Validity of clinic blood pressure compared to ambulatory monitoring in hypertensive patients in a primary care setting. Blood Press. 2015;24:111-118.

14. Doebler P, Holling H. Meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy with mada. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/mada/vignettes/mada.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2015.

15. Myers MG, Oh PI, Reeves RA, et al. Prevalence of white coat effect in treated hypertensive patients in the community. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:591-597.

16. Imai Y, Tsuji I, Nagai K, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in evaluating the prevalence of hypertension in adults in Ohasama, a rural Japanese community. Hypertens Res. 1996;19:207-212.

17. Taylor RS, Stockman J, Kernick D, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring for hypertension in general practice. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:301-304.

18. Little P, Barnett J, Barnsley L, et al. Comparison of agreement between different measures of blood pressure in primary care and daytime ambulatory blood pressure. BMJ. 2002;325:254.

19. Bur A, Herkner H, Vlcek M, et al. Classification of blood pressure levels by ambulatory blood pressure in hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;40:817-822.

20. Lindbaek M, Sandvik E, Liodden K, et al. Predictors for the white coat effect in general practice patients with suspected and treated hypertension. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53:790-793.

21. Martínez MA, Sancho T, García P, et al. Home blood pressure in poorly controlled hypertension: relationship with ambulatory blood pressure and organ damage. Blood Press Monit. 2006;11:207-213.

22. Sierra BC, de la Sierra IA, Sobrino J, et al. Monitorización ambulatoria de la presión arterial (MAPA): características clínicas de 31.530 pacientes. Medicina Clínica. 2007;129:1-5.

23. Gómez MA, García L, Sánchez Á, et al. Agreement and disagreement between different methods of measuring blood pressure. Hipertensión (Madr). 2008;25:231-239.

24. Banegas JR, Segura J, De la Sierra A, et al. Gender differences in office and ambulatory control of hypertension. Am J Med. 2008;121:1078-1084.

25. Zaninelli A, Parati G, Cricelli C, et al. Office and 24-h ambulatory blood pressure control by treatment in general practice: the ‘Monitoraggio della pressione ARteriosa nella medicina TErritoriale’ study. J Hypertens. 2010;28:910-917.

26. Llisterri JL, Morillas P, Pallarés V, et al. Differences in the degree of control of arterial hypertension according to the measurement procedure of blood pressure in patients ≥ 65 years. FAPRES study. Rev Clin Esp. 2011;211:76-84.

27. Straus SE, Richardson WS, Glasziou P, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to practice and teach it. 4th ed. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.

28. Van der Wel MC, Buunk IE, van Weel C, et al. A novel approach to office blood pressure measurement: 30-minute office blood pressure vs daytime ambulatory blood pressure. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:128-135.

ABSTRACT

Purpose We performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office blood pressure (BP) measurement in a primary care setting, using ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

Methods We conducted a literature search for studies published up to December 2013 that included hypertensive patients receiving treatment in a primary care setting. We compared the mean office BP with readings obtained by ABPM. We summarized the diagnostic accuracy of office BP with respect to ABPM in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR), with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results Only 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and contained data to calculate the differences between the means of office and ambulatory BP measurements. Five were suitable for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios, and 4 contained sufficient extractable data for meta-analysis. Compared with ABPM (thresholds of 140/90 mm Hg for office BP; 130/80 mmHg for ABPM) in diagnosing uncontrolled BP, office BP measurement had a sensitivity of 81.9% (95% CI, 74.8%-87%) and specificity of 41.1% (95% CI, 35.1%-48.4%). Positive LR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.32-1.38), and the negative LR was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.37-0.53).

Conclusion Likelihood ratios show that isolated BP measurement in the office does not confirm or rule out the presence of poor BP control. Likelihood of underestimating or overestimating BP control is high when relying on in-office BP measurement alone.

A growing body of evidence supports more frequent use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension1 and to monitor blood pressure (BP) response to treatment.2 The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure has long accepted ABPM for diagnosis of hypertension,3 and many clinicians consider ABPM the reference standard for diagnosing true hypertension and for accurately assessing associated cardiovascular risk in adults, regardless of office BP readings.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends obtaining BP measurements outside the clinical setting to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension before starting treatment.5 The USPSTF also asserts that elevated 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP is consistently and significantly associated with stroke and other cardiovascular events independent of office BP readings and has greater predictive value than office monitoring.5 The USPSTF concludes that ABPM, because of its large evidence base, is the best confirmatory test for hypertension.6 The recommendation of the American Academy of Family Physicians is similar to that of the USPSTF.7

The challenge. Despite the considerable support for ABPM, this method of BP measurement is still not sufficiently integrated into primary care. And some guidelines, such as those of

But ABPM’s advantages are numerous. Ambulatory monitors, which can record BP for 24 hours, are typically programmed to take readings every 15 to 30 minutes, providing estimates of mean daytime and nighttime BP and revealing an individual’s circadian pattern of BP.8-10 Ambulatory BP values usually considered the uppermost limit of normal are 135/85 mm Hg (day), 120/70 mm Hg (night), and 130/80 mm Hg (24 hour).8

Office BP monitoring, usually performed manually by medical staff, has 2 main drawbacks: the well-known white-coat effect experienced by many patients, and the relatively small number of possible measurements. A more reliable in-office BP estimation of BP would require repeated measurements at each of several visits.

By comparing ABPM and office measurements, 4 clinical findings are possible: isolated clinic or office (white-coat) hypertension (ICH); isolated ambulatory (masked) hypertension (IAH); consistent normotension; or sustained hypertension. With ICH, BP is high in the office and normal with ABPM. With IAH, BP is normal in the office and high with ABPM. With consistent normotension and sustained hypertension, BP readings with both types of measurement agree.8,9

In patients being treated for hypertension, ICH leads to an overestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in overtreatment. The cardiovascular risk, although controversial, is usually lower than in patients diagnosed with sustained hypertension.11 IAH leads to an underestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in undertreatment; its associated cardiovascular risk is similar to that of sustained hypertension.12

Our research objective. We recently published a study conducted with 137 hypertensive patients in a primary care center.13 Our conclusion was that in-office measurement of BP had insufficient clinical validity to be recommended as a sole method of monitoring BP control. In accurately classifying BP as controlled or uncontrolled, clinic measurement agreed with 24h-ABPM in just 64.2% of cases.13

In our present study, we performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office BP measurement in a primary care setting, using ABPM as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

METHODS

Most published studies comparing conventional office BP measurement with ABPM have been conducted with patients not taking antihypertensive medication. We excluded these studies and conducted a literature search for studies published up to December 2013 that included hypertensive patients receiving treatment in a primary care setting.

We searched Medline (from 1950 onward) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. For the Medline search, we combined keywords for office BP, hypertension, and ambulatory BP with keywords for outpatient setting and primary care, using the following syntax: (((“clinic blood pressure” OR “office blood pressure” OR “casual blood pressure”))) AND (“hypertension” AND ((((“24-h ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “24 h ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “24 hour ambulatory blood pressure”) OR “blood pressure monitoring, ambulatory”[Mesh]) AND ((((((“outpatient setting”) OR “primary care”) OR “family care”) OR “family physician”) OR “family practice”) OR “general practice”)). We chose studies published in English and reviewed the titles and abstracts of identified articles.

With the aim of identifying additional candidate studies, we reviewed the reference lists of eligible primary studies, narrative reviews, and systematic reviews. The studies were generally of good quality and used appropriate statistical methods. Only primary studies qualified for meta-analysis.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Acceptable studies had to be conducted in a primary care setting with patients being treated for hypertension, and had to provide data comparing office BP measurement with ABPM. We excluded studies in which participants were treated in the hospital, were untreated, or had not been diagnosed with hypertension.

The quality of the studies included in the meta-analysis was judged by 2 independent observers according to the following criteria: the clear classification and initial comparison of both measurements; explicit and defined diagnostic criteria; compliance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria; and clear and precise definition of outcome variables.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from each included study: study population, number of patients included, age, gender distribution, number of measurements (ambulatory and office BP), equipment validation, mean office and ambulatory BP, and the period of ambulatory BP measurement. We included adult patients of all ages, and we compared the mean office BP with those obtained by ABPM in hypertensive patients.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

For each study, we summarized the diagnostic accuracy of office BP with respect to ABPM in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LRs), with the 95% confidence interval (CI), if available. If these rates were not directly reported in the original papers, we used the published data to calculate them.

We used the R v2.15.1 software with the “mada” package for meta-analysis.14 Although a bivariate approach is preferred for the meta-analysis of diagnostic accuracy, it cannot be recommended if the number of primary studies to pool is too small,14 as happened in our case. Therefore, we used a univariate approach and pooled summary statistics for positive LR, negative LR, and the diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with their 95% confidence intervals. We used the DerSimonian-Laird method to perform a random-effect meta-analysis. To explore heterogeneity between the studies, we used the Cochran’s Q heterogeneity test, I2 index, and Galbraith and L’Abbé plots.

RESULTS

Our search identified 237 studies, only 12 of which met the inclusion criteria and contained data to calculate the differences between the means of office and ambulatory BP measurements (TABLES 1 AND 2).15-26 Of these 12 studies, 5 were suitable for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and LR (TABLE 3),16,18,22,24,26 and 4 contained sufficient extractable data for meta-analysis. The study by Little et al18 was not included in the meta-analysis, as the number of true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative results could not be deduced from published data.

The studies differed in sample size (40-31,530), patient ages (mean, 55-72.8 years), sex (percentage of men, 31%-52.9%), and number of measurements for office BP (1-9) and ABPM (32-96) (TABLE 1),15-26 as well as in daytime and nighttime periods for ABPM and BP thresholds, and in differences between the mean office and ambulatory BPs (TABLE 2).15-26

In general, the mean office BP measurements were higher than those obtained with ABPM in any period—from 5/0 mm Hg to 27.4/10.1 mm Hg in the day, and from 7.9/6.3 mm Hg to 31.2/13.7 mm Hg over 24 hours (TABLE 2).15-26

Compared with ABPM in diagnosing uncontrolled BP, office BP measurement had a sensitivity of 55.7% to 91.2% and a specificity of 25.8% to 61.8% (depending on whether the measure was carried out by the doctor or nurse18); positive LR ranged from 1.2 to 1.4, and negative LR from 0.3 to 0.72 (TABLE 3).16,18,22,24,26

For meta-analysis, we pooled studies with the same thresholds (140/90 mm Hg for office BP; 130/80 mm Hg for ABPM), with diagnostic accuracy of office BP expressed as pooled positive and negative LR, and as pooled DOR. The meta-analysis revealed that the pooled positive LR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.32-1.38), and the pooled negative LR was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.37-0.53). The pooled DOR was 3.47 (95% CI, 3.02-3.98). Sensitivity was 81.9% (95% CI, 74.8%-87%) and specificity was 41.1% (95% CI, 35.1%-48.4%).

One study16 had a slightly different ambulatory diagnostic threshold (133/78 mm Hg), so we excluded it from a second meta-analysis. Results after the exclusion did not change significantly: positive LR was 1.39 (95% CI, 1.34-1.45); negative LR was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.33-0.44); and DOR was 3.77 (95% CI, 3.31-4.43).

In conclusion, the use of office-based BP readings in the outpatient clinic does not correlate well with ABPM. Therefore, caution must be used when making management decisions based solely on in-office readings of BP.

DISCUSSION

The European Society of Hypertension still regards office BP measurement as the gold standard in screening for, diagnosing, and managing hypertension. As previously mentioned, though, office measurements are usually handled by medical staff and can be compromised by the white-coat effect and a small number of measurements. The USPSTF now considers ABPM the reference standard in primary care to diagnose hypertension in adults, to corroborate or contradict office-based determinations of elevated BP (whether based on single or repeated-interval measurements), and to avoid overtreatment of individuals displaying elevated office BP yet proven normotensive by ABPM.4,7 The recommendation of the American Academy of Family Physicians is similar to that of the USPSTF.7 Therefore, evidence supports ABPM as the reference standard for confirming elevated office BP screening results to avoid misdiagnosis and overtreatment of individuals with isolated clinic hypertension.7

How office measurements stack up against ABPM

Checking the validity of decisions in clinical practice is extremely important for patient management. One of the tools used for decision-making is an estimate of the LR. We used the LR to assess the value of office BP measurement in determining controlled or uncontrolled BP. A high LR (eg, >10) indicates that the office BP can be used to rule in the disease (uncontrolled BP) with a high probability, while a low LR (eg, <0.1) could rule it out. An LR of around one indicates that the office BP measurement cannot rule the diagnosis of uncontrolled BP in or out.27 In our meta-analysis, the positive LR is 1.35 and negative LR is 0.44. Therefore, in treated hypertensive patients, an indication of uncontrolled BP as measured in the clinic does not confirm a diagnosis of uncontrolled BP (as judged by the reference standard of ABPM). On the other hand, the negative LR means that normal office BP does not rule out uncontrolled BP, which may be detected with ABPM. Consequently, the measurement of BP in the office does not change the degree of (un)certainty of adequate control of BP. This knowledge is important, to avoid overtreatment of white coat hypertension and undertreatment of masked cases.

As previously mentioned, we reported similar results in a study designed to determine the validity of office BP measurement in a primary care setting compared with ABPM.13 In that paper, the level of agreement between both methods was poor, indicating that clinic measurements could not be recommended as a single method of BP control in hypertensive patients.

The use of ABPM in diagnosing hypertension is likely to increase as a consequence of some guideline updates.2 Our study emphasizes the importance of their use in the control of hypertensive patients.

Another published meta-analysis1 investigated the validity of office BP for the diagnosis of hypertension in untreated patients, with diagnostic thresholds for arterial hypertension set at 140/90 mm Hg for office measurement, and 135/85 mm Hg for ABPM. In that paper, the sensitivity of office BP was 74.6% (95% CI, 60.7-84.8) and the specificity was 74.6% (95% CI, 47.9-90.4).

In our present study carried out with hypertensive patients receiving treatment, we obtained a slightly higher sensitivity value of 81.9% (within the CI of this meta-analysis) and a lower specificity of 41.1%. Therefore, the discordance between office BP and ABPM seems to be similar for the diagnosis of hypertension and the classification of hypertension as being well or poorly controlled. This confirms the low validity of the office BP, both for diagnosis and monitoring of hypertensive patients.

Strengths of our study. The study focused on (treated) hypertensive patients in a primary care setting, where hypertension is most often managed. It confirms that ABPM is indispensable to a good clinical practice.

Limitations of our study are those inherent to meta-analyses. The main weakness of our study is the paucity of data available regarding the utility of ABPM for monitoring BP control with treatment in a primary care setting. Other limitations are the variability in BP thresholds used, the number of measurements performed, and the ambulatory BP devices used. These differences could contribute to the observed heterogeneity.

Application of our results must take into account that we included only those studies performed in a primary care setting with treated hypertensive patients.

Moreover, this study was not designed to evaluate the consequences of over- and undertreatment of blood pressure, nor to address the accuracy of automated blood pressure machines or newer health and fitness devices.

Implications for practice, policy, or future research. Alternative monitoring methods are home BP self-measurement and automated 30-minute clinic BP measurement.28 However, ABPM provides us with unique information about the BP pattern (dipping or non-dipping), BP variability, and mean nighttime BP. This paper establishes that the measurement of BP in the office is not an accurate method to monitor BP control. ABPM should be incorporated in usual clinical practice in primary care. Although the consequences of ambulatory monitoring are not the focus of this study, we acknowledge that the decision to incorporate ABPM in clinical practice depends on the availability of ambulatory devices, proper training of health care workers, and a cost-effectiveness analysis of its use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Sergio Reino-González, MD, PhD, Adormideras Primary Health Center, Poligono de Adormideras s/n. 15002 A Coruña, Spain; [email protected].

ABSTRACT

Purpose We performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office blood pressure (BP) measurement in a primary care setting, using ambulatory blood pressure measurement (ABPM) as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

Methods We conducted a literature search for studies published up to December 2013 that included hypertensive patients receiving treatment in a primary care setting. We compared the mean office BP with readings obtained by ABPM. We summarized the diagnostic accuracy of office BP with respect to ABPM in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR), with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results Only 12 studies met the inclusion criteria and contained data to calculate the differences between the means of office and ambulatory BP measurements. Five were suitable for calculating sensitivity, specificity, and likelihood ratios, and 4 contained sufficient extractable data for meta-analysis. Compared with ABPM (thresholds of 140/90 mm Hg for office BP; 130/80 mmHg for ABPM) in diagnosing uncontrolled BP, office BP measurement had a sensitivity of 81.9% (95% CI, 74.8%-87%) and specificity of 41.1% (95% CI, 35.1%-48.4%). Positive LR was 1.35 (95% CI, 1.32-1.38), and the negative LR was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.37-0.53).

Conclusion Likelihood ratios show that isolated BP measurement in the office does not confirm or rule out the presence of poor BP control. Likelihood of underestimating or overestimating BP control is high when relying on in-office BP measurement alone.

A growing body of evidence supports more frequent use of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension1 and to monitor blood pressure (BP) response to treatment.2 The Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure has long accepted ABPM for diagnosis of hypertension,3 and many clinicians consider ABPM the reference standard for diagnosing true hypertension and for accurately assessing associated cardiovascular risk in adults, regardless of office BP readings.4 The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends obtaining BP measurements outside the clinical setting to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension before starting treatment.5 The USPSTF also asserts that elevated 24-hour ambulatory systolic BP is consistently and significantly associated with stroke and other cardiovascular events independent of office BP readings and has greater predictive value than office monitoring.5 The USPSTF concludes that ABPM, because of its large evidence base, is the best confirmatory test for hypertension.6 The recommendation of the American Academy of Family Physicians is similar to that of the USPSTF.7

The challenge. Despite the considerable support for ABPM, this method of BP measurement is still not sufficiently integrated into primary care. And some guidelines, such as those of

But ABPM’s advantages are numerous. Ambulatory monitors, which can record BP for 24 hours, are typically programmed to take readings every 15 to 30 minutes, providing estimates of mean daytime and nighttime BP and revealing an individual’s circadian pattern of BP.8-10 Ambulatory BP values usually considered the uppermost limit of normal are 135/85 mm Hg (day), 120/70 mm Hg (night), and 130/80 mm Hg (24 hour).8

Office BP monitoring, usually performed manually by medical staff, has 2 main drawbacks: the well-known white-coat effect experienced by many patients, and the relatively small number of possible measurements. A more reliable in-office BP estimation of BP would require repeated measurements at each of several visits.

By comparing ABPM and office measurements, 4 clinical findings are possible: isolated clinic or office (white-coat) hypertension (ICH); isolated ambulatory (masked) hypertension (IAH); consistent normotension; or sustained hypertension. With ICH, BP is high in the office and normal with ABPM. With IAH, BP is normal in the office and high with ABPM. With consistent normotension and sustained hypertension, BP readings with both types of measurement agree.8,9

In patients being treated for hypertension, ICH leads to an overestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in overtreatment. The cardiovascular risk, although controversial, is usually lower than in patients diagnosed with sustained hypertension.11 IAH leads to an underestimation of uncontrolled BP and may result in undertreatment; its associated cardiovascular risk is similar to that of sustained hypertension.12

Our research objective. We recently published a study conducted with 137 hypertensive patients in a primary care center.13 Our conclusion was that in-office measurement of BP had insufficient clinical validity to be recommended as a sole method of monitoring BP control. In accurately classifying BP as controlled or uncontrolled, clinic measurement agreed with 24h-ABPM in just 64.2% of cases.13

In our present study, we performed a literature review and meta-analysis to ascertain the validity of office BP measurement in a primary care setting, using ABPM as a benchmark in the monitoring of hypertensive patients receiving treatment.

METHODS