User login

Treatment facility volume linked to survival in MM

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) are more likely to live longer if they are treated at a medical center where the staff has more experience with the disease, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The study showed that patients treated at medical centers seeing 10 new MM patients per year had a 20% higher risk of death than patients treated at centers seeing 40 new MM patients per year.

Most cancer treatment centers in the US see fewer than 10 new MM patients per year.

“It is very difficult to be proficient when doctors are seeing only 1 or 2 new cases of multiple myeloma per year,” said study author Ronald Go, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Studies on cancer surgery have shown the more experience the center or practitioner has, the better the outcome. We wanted to see if volume matters when it comes to nonsurgical treatment of rare cancers such as multiple myeloma.”

To investigate, Dr Go and his colleagues used the National Cancer Database, examining outcomes for 94,722 newly diagnosed MM patients treated at 1333 facilities between 2003 and 2011.

The researchers grouped the facilities into quartiles according to the volume of MM patients treated there each year.

The mean number of MM patients treated per year was:

- Less than 3.6 for quartile 1 (Q1)

- 3.6 to 6.1 for Q2

- 6.1 to 10.3 for Q3

- More than 10.3 for Q4.

The majority of patients (60.3%) were treated in Q4 facilities. For all facilities, the median number of new MM patients per year was 6.1 (range, 3.6 to 10.3). The mean was 8.8 ± 9.9.

The researchers calculated the relationship between MM patient volume at these facilities and patient mortality, adjusting for demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, geographic factors, comorbidities, and year of diagnosis.

Outcomes

The unadjusted median overall survival was 26.9 months for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 29.1 months for Q2, 31.9 months for Q3, and 49.1 months for Q4 (P<0.001).

The 1-year mortality rate was 33.5% for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 32.3% for Q2, 30.7% for Q3, and 21.9% for Q4.

The researchers’ multivariable analysis showed that facility volume was independently associated with all-cause mortality.

Patients treated at the lower-quartile facilities had a higher risk of death than patients treated at Q4 facilities. The hazard ratios were 1.12 for patients at Q3 facilities, 1.12 for Q2, and 1.22 for Q1.

The researchers performed another analysis in which volume was treated as a continuous variable, and they compared various volume sizes to a reference volume of 10 patients per year.

Compared with facilities treating 10 new MM patients per year, facilities treating 20 MM patients per year had roughly 10% lower overall mortality rates.

Facilities treating 30 MM patients per year had about 15% lower mortality rates. And facilities treating 40 MM patients per year had 20% lower overall mortality rates. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) are more likely to live longer if they are treated at a medical center where the staff has more experience with the disease, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The study showed that patients treated at medical centers seeing 10 new MM patients per year had a 20% higher risk of death than patients treated at centers seeing 40 new MM patients per year.

Most cancer treatment centers in the US see fewer than 10 new MM patients per year.

“It is very difficult to be proficient when doctors are seeing only 1 or 2 new cases of multiple myeloma per year,” said study author Ronald Go, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Studies on cancer surgery have shown the more experience the center or practitioner has, the better the outcome. We wanted to see if volume matters when it comes to nonsurgical treatment of rare cancers such as multiple myeloma.”

To investigate, Dr Go and his colleagues used the National Cancer Database, examining outcomes for 94,722 newly diagnosed MM patients treated at 1333 facilities between 2003 and 2011.

The researchers grouped the facilities into quartiles according to the volume of MM patients treated there each year.

The mean number of MM patients treated per year was:

- Less than 3.6 for quartile 1 (Q1)

- 3.6 to 6.1 for Q2

- 6.1 to 10.3 for Q3

- More than 10.3 for Q4.

The majority of patients (60.3%) were treated in Q4 facilities. For all facilities, the median number of new MM patients per year was 6.1 (range, 3.6 to 10.3). The mean was 8.8 ± 9.9.

The researchers calculated the relationship between MM patient volume at these facilities and patient mortality, adjusting for demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, geographic factors, comorbidities, and year of diagnosis.

Outcomes

The unadjusted median overall survival was 26.9 months for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 29.1 months for Q2, 31.9 months for Q3, and 49.1 months for Q4 (P<0.001).

The 1-year mortality rate was 33.5% for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 32.3% for Q2, 30.7% for Q3, and 21.9% for Q4.

The researchers’ multivariable analysis showed that facility volume was independently associated with all-cause mortality.

Patients treated at the lower-quartile facilities had a higher risk of death than patients treated at Q4 facilities. The hazard ratios were 1.12 for patients at Q3 facilities, 1.12 for Q2, and 1.22 for Q1.

The researchers performed another analysis in which volume was treated as a continuous variable, and they compared various volume sizes to a reference volume of 10 patients per year.

Compared with facilities treating 10 new MM patients per year, facilities treating 20 MM patients per year had roughly 10% lower overall mortality rates.

Facilities treating 30 MM patients per year had about 15% lower mortality rates. And facilities treating 40 MM patients per year had 20% lower overall mortality rates. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Patients with multiple myeloma (MM) are more likely to live longer if they are treated at a medical center where the staff has more experience with the disease, according to research published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The study showed that patients treated at medical centers seeing 10 new MM patients per year had a 20% higher risk of death than patients treated at centers seeing 40 new MM patients per year.

Most cancer treatment centers in the US see fewer than 10 new MM patients per year.

“It is very difficult to be proficient when doctors are seeing only 1 or 2 new cases of multiple myeloma per year,” said study author Ronald Go, MD, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

“Studies on cancer surgery have shown the more experience the center or practitioner has, the better the outcome. We wanted to see if volume matters when it comes to nonsurgical treatment of rare cancers such as multiple myeloma.”

To investigate, Dr Go and his colleagues used the National Cancer Database, examining outcomes for 94,722 newly diagnosed MM patients treated at 1333 facilities between 2003 and 2011.

The researchers grouped the facilities into quartiles according to the volume of MM patients treated there each year.

The mean number of MM patients treated per year was:

- Less than 3.6 for quartile 1 (Q1)

- 3.6 to 6.1 for Q2

- 6.1 to 10.3 for Q3

- More than 10.3 for Q4.

The majority of patients (60.3%) were treated in Q4 facilities. For all facilities, the median number of new MM patients per year was 6.1 (range, 3.6 to 10.3). The mean was 8.8 ± 9.9.

The researchers calculated the relationship between MM patient volume at these facilities and patient mortality, adjusting for demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, geographic factors, comorbidities, and year of diagnosis.

Outcomes

The unadjusted median overall survival was 26.9 months for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 29.1 months for Q2, 31.9 months for Q3, and 49.1 months for Q4 (P<0.001).

The 1-year mortality rate was 33.5% for patients treated at Q1 facilities, 32.3% for Q2, 30.7% for Q3, and 21.9% for Q4.

The researchers’ multivariable analysis showed that facility volume was independently associated with all-cause mortality.

Patients treated at the lower-quartile facilities had a higher risk of death than patients treated at Q4 facilities. The hazard ratios were 1.12 for patients at Q3 facilities, 1.12 for Q2, and 1.22 for Q1.

The researchers performed another analysis in which volume was treated as a continuous variable, and they compared various volume sizes to a reference volume of 10 patients per year.

Compared with facilities treating 10 new MM patients per year, facilities treating 20 MM patients per year had roughly 10% lower overall mortality rates.

Facilities treating 30 MM patients per year had about 15% lower mortality rates. And facilities treating 40 MM patients per year had 20% lower overall mortality rates. ![]()

Agent could treat hemophilia A and B, team says

A new bypassing agent mimics the pro-clotting activity of factor V Leiden and might prove effective for treating hemophilia A and B, according to preclinical research published in Blood.

“We know that patients who have severe hemophilia and also have mutations that increase clotting, such as factor V Leiden, experience less severe bleeding,” said study author Trevor Baglin, MD, of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, UK.

In patients with factor V Leiden, defects in the anticoagulant activated protein C (APC) mechanism lead to an overactive production of thrombin.

The researchers set out to determine if they could exploit this phenomenon to treat hemophilia by developing a direct inhibitor of APC. They modified serine protease inhibitors, known as serpins, to make them specific and efficient inhibitors of APC.

“We hypothesized that if we targeted the protein C pathway we could prolong thrombin production,” said study author James Huntington, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“We engineered a serpin so that it could selectively prevent APC from shutting down thrombin production before the formation of a stable clot.”

The researchers administered the serpin to mice with hemophilia B and clipped their tails. In this model, the blood loss decreased as the dose increased, with the highest dose reducing bleeding to the level of healthy mice.

Further injury models underscored that the serpin helped the majority of mice form stable clots, with higher doses resulting in quicker clot formation.

The serpin was also able to accelerate clot formation when added to blood samples from patients with hemophilia A.

“It is our understanding that because we are targeting a general anticlotting process, our serpin could effectively treat patients with either hemophilia A or B, including those who develop inhibitors to more traditional therapy,” Dr Huntington said.

“Additionally, we have focused on engineering the serpin to be both subcutaneously delivered and long-acting. This will free patients from the cumbersome thrice-weekly infusions that are necessary under many contemporary therapy regimens.”

“Within 3 years, we hope to be conducting our first-in-man trials of a subcutaneously administered form of our serpin,” Dr Baglin added.

“It is important to remember that the majority of people in the world with hemophilia have no access to therapy. A stable, subcutaneous, long-acting, effective hemostatic agent could bring treatment to a great deal many more hemophilia sufferers.”

This study forms part of a patent application by the authors, and the serpin is being developed into a therapeutic by a start-up company known as ApcinteX, with funding from Medicxi. ![]()

A new bypassing agent mimics the pro-clotting activity of factor V Leiden and might prove effective for treating hemophilia A and B, according to preclinical research published in Blood.

“We know that patients who have severe hemophilia and also have mutations that increase clotting, such as factor V Leiden, experience less severe bleeding,” said study author Trevor Baglin, MD, of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, UK.

In patients with factor V Leiden, defects in the anticoagulant activated protein C (APC) mechanism lead to an overactive production of thrombin.

The researchers set out to determine if they could exploit this phenomenon to treat hemophilia by developing a direct inhibitor of APC. They modified serine protease inhibitors, known as serpins, to make them specific and efficient inhibitors of APC.

“We hypothesized that if we targeted the protein C pathway we could prolong thrombin production,” said study author James Huntington, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“We engineered a serpin so that it could selectively prevent APC from shutting down thrombin production before the formation of a stable clot.”

The researchers administered the serpin to mice with hemophilia B and clipped their tails. In this model, the blood loss decreased as the dose increased, with the highest dose reducing bleeding to the level of healthy mice.

Further injury models underscored that the serpin helped the majority of mice form stable clots, with higher doses resulting in quicker clot formation.

The serpin was also able to accelerate clot formation when added to blood samples from patients with hemophilia A.

“It is our understanding that because we are targeting a general anticlotting process, our serpin could effectively treat patients with either hemophilia A or B, including those who develop inhibitors to more traditional therapy,” Dr Huntington said.

“Additionally, we have focused on engineering the serpin to be both subcutaneously delivered and long-acting. This will free patients from the cumbersome thrice-weekly infusions that are necessary under many contemporary therapy regimens.”

“Within 3 years, we hope to be conducting our first-in-man trials of a subcutaneously administered form of our serpin,” Dr Baglin added.

“It is important to remember that the majority of people in the world with hemophilia have no access to therapy. A stable, subcutaneous, long-acting, effective hemostatic agent could bring treatment to a great deal many more hemophilia sufferers.”

This study forms part of a patent application by the authors, and the serpin is being developed into a therapeutic by a start-up company known as ApcinteX, with funding from Medicxi. ![]()

A new bypassing agent mimics the pro-clotting activity of factor V Leiden and might prove effective for treating hemophilia A and B, according to preclinical research published in Blood.

“We know that patients who have severe hemophilia and also have mutations that increase clotting, such as factor V Leiden, experience less severe bleeding,” said study author Trevor Baglin, MD, of Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge, UK.

In patients with factor V Leiden, defects in the anticoagulant activated protein C (APC) mechanism lead to an overactive production of thrombin.

The researchers set out to determine if they could exploit this phenomenon to treat hemophilia by developing a direct inhibitor of APC. They modified serine protease inhibitors, known as serpins, to make them specific and efficient inhibitors of APC.

“We hypothesized that if we targeted the protein C pathway we could prolong thrombin production,” said study author James Huntington, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“We engineered a serpin so that it could selectively prevent APC from shutting down thrombin production before the formation of a stable clot.”

The researchers administered the serpin to mice with hemophilia B and clipped their tails. In this model, the blood loss decreased as the dose increased, with the highest dose reducing bleeding to the level of healthy mice.

Further injury models underscored that the serpin helped the majority of mice form stable clots, with higher doses resulting in quicker clot formation.

The serpin was also able to accelerate clot formation when added to blood samples from patients with hemophilia A.

“It is our understanding that because we are targeting a general anticlotting process, our serpin could effectively treat patients with either hemophilia A or B, including those who develop inhibitors to more traditional therapy,” Dr Huntington said.

“Additionally, we have focused on engineering the serpin to be both subcutaneously delivered and long-acting. This will free patients from the cumbersome thrice-weekly infusions that are necessary under many contemporary therapy regimens.”

“Within 3 years, we hope to be conducting our first-in-man trials of a subcutaneously administered form of our serpin,” Dr Baglin added.

“It is important to remember that the majority of people in the world with hemophilia have no access to therapy. A stable, subcutaneous, long-acting, effective hemostatic agent could bring treatment to a great deal many more hemophilia sufferers.”

This study forms part of a patent application by the authors, and the serpin is being developed into a therapeutic by a start-up company known as ApcinteX, with funding from Medicxi. ![]()

NORD publishes physician guide to CTCL

mycosis fungoides

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has published a guide for physicians treating patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The guide contains information about disease classification, signs and symptoms of CTCL, methods of diagnosing the disease, standard therapies, and investigational therapies for CTCL.

The guide also includes a list of resources for physicians and patients.

“The NORD Physician Guide to Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL)” is available for free on the NORD Physician Guides website.

The guide was made possible by an educational grant from Therakos, now a part of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

The guide was developed in collaboration with Oleg E. Akilov, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pennsylvania.

“Eczema and even some cases of psoriasis may look very similar to mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas,” Dr Akilov noted.

“It is important to be aware of these similarities and to be ready to think about cutaneous lymphoma when a patient with ‘common dermatosis’ does not respond to regular treatments.”

About NORD guides

NORD established its physician guide series as part of a broader strategic initiative to promote earlier diagnosis and state-of-the-art care for people with rare diseases. Each online guide is written or reviewed by a medical professional with expertise on the topic.

Other recent guides in the series include:

- The NORD Physician Guide to Mitochondrial Myopathies

- The NORD Physician Guide to Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease.

“People who have rare diseases often go for many years without a diagnosis,” said Marsha Lanes, a genetic counselor in NORD’s Educational Initiatives Department.

“The purpose of NORD’s free online physician guides is to reduce the time to diagnosis and encourage optimal treatment for patients with little-known and little-understood rare diseases.” ![]()

mycosis fungoides

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has published a guide for physicians treating patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The guide contains information about disease classification, signs and symptoms of CTCL, methods of diagnosing the disease, standard therapies, and investigational therapies for CTCL.

The guide also includes a list of resources for physicians and patients.

“The NORD Physician Guide to Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL)” is available for free on the NORD Physician Guides website.

The guide was made possible by an educational grant from Therakos, now a part of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

The guide was developed in collaboration with Oleg E. Akilov, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pennsylvania.

“Eczema and even some cases of psoriasis may look very similar to mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas,” Dr Akilov noted.

“It is important to be aware of these similarities and to be ready to think about cutaneous lymphoma when a patient with ‘common dermatosis’ does not respond to regular treatments.”

About NORD guides

NORD established its physician guide series as part of a broader strategic initiative to promote earlier diagnosis and state-of-the-art care for people with rare diseases. Each online guide is written or reviewed by a medical professional with expertise on the topic.

Other recent guides in the series include:

- The NORD Physician Guide to Mitochondrial Myopathies

- The NORD Physician Guide to Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease.

“People who have rare diseases often go for many years without a diagnosis,” said Marsha Lanes, a genetic counselor in NORD’s Educational Initiatives Department.

“The purpose of NORD’s free online physician guides is to reduce the time to diagnosis and encourage optimal treatment for patients with little-known and little-understood rare diseases.” ![]()

mycosis fungoides

The National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) has published a guide for physicians treating patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

The guide contains information about disease classification, signs and symptoms of CTCL, methods of diagnosing the disease, standard therapies, and investigational therapies for CTCL.

The guide also includes a list of resources for physicians and patients.

“The NORD Physician Guide to Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL)” is available for free on the NORD Physician Guides website.

The guide was made possible by an educational grant from Therakos, now a part of Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals.

The guide was developed in collaboration with Oleg E. Akilov, MD, PhD, of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pennsylvania.

“Eczema and even some cases of psoriasis may look very similar to mycosis fungoides, the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas,” Dr Akilov noted.

“It is important to be aware of these similarities and to be ready to think about cutaneous lymphoma when a patient with ‘common dermatosis’ does not respond to regular treatments.”

About NORD guides

NORD established its physician guide series as part of a broader strategic initiative to promote earlier diagnosis and state-of-the-art care for people with rare diseases. Each online guide is written or reviewed by a medical professional with expertise on the topic.

Other recent guides in the series include:

- The NORD Physician Guide to Mitochondrial Myopathies

- The NORD Physician Guide to Paroxysmal Nocturnal Hemoglobinuria (PNH)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome (aHUS)

- The NORD Physician Guide to Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Lung Disease.

“People who have rare diseases often go for many years without a diagnosis,” said Marsha Lanes, a genetic counselor in NORD’s Educational Initiatives Department.

“The purpose of NORD’s free online physician guides is to reduce the time to diagnosis and encourage optimal treatment for patients with little-known and little-understood rare diseases.” ![]()

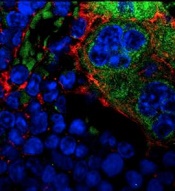

Explaining the development of MPNs, leukemia

MSPCs with mutant PTPN11

(red) and monocytes (green).

Image courtesy of

Dong et al, Nature 2016

New research published in Nature has shown how certain mutations drive the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and leukemia.

Investigators discovered that PTPN11 activating mutations promote the development and progression of MPNs through “profound detrimental effects” on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

The team also identified a potential method of treating MPNs in patients with Noonan syndrome.

Noonan syndrome can be caused by mutations in several genes, but the most common is PTPN11. Children with Noonan syndrome are known to have an increased risk of developing MPNs/leukemia.

Previous research had established that mutations in PTPN11 have a conventional cell-autonomous effect on HSC growth.

In the current study, investigators showed that PTPN11 mutations also affect mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (MSPCs) and osteoprogenitors.

The mutations cause over-production of the CC chemokine CCL3, which attracts monocytes into the HSCs’ niches. The monocytes make inflammatory molecules that stimulate the HSCs to differentiate and proliferate, leading to MPNs and leukemia.

“We have identified CCL3 as a potential therapeutic target for controlling leukemic progression in Noonan syndrome and for improving stem cell transplantation therapy in Noonan syndrome-associated leukemias,” said study author Cheng-Kui Qu, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr Qu and his colleagues began this research intending to investigate the effects of PTPN11 mutations in the nervous system. The team developed genetically engineered mice that had altered PTPN11 in neural cells.

The mice all developed a condition resembling an MPN at an early age. It turned out that the mice had changes in the PTPN11 gene in their MSPCs and osteoprogenitors (in addition to their neural cells) but not in their HSCs.

The investigators found the MPN in these PTPN11-mutant mice can be treated in the short-term by HSC transplant, but the condition comes back within months.

However, drugs counteracting CCL3 successfully reversed MPN phenotypes. One of the drugs is the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc, which is approved in the US to combat HIV infection, and another is the CCR1 antagonist BX471.

The investigators noted that other Noonan syndrome mutations, in genes besides PTPN11, need to be assessed for their effects on MPN/leukemia formation. ![]()

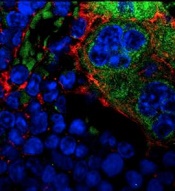

MSPCs with mutant PTPN11

(red) and monocytes (green).

Image courtesy of

Dong et al, Nature 2016

New research published in Nature has shown how certain mutations drive the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and leukemia.

Investigators discovered that PTPN11 activating mutations promote the development and progression of MPNs through “profound detrimental effects” on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

The team also identified a potential method of treating MPNs in patients with Noonan syndrome.

Noonan syndrome can be caused by mutations in several genes, but the most common is PTPN11. Children with Noonan syndrome are known to have an increased risk of developing MPNs/leukemia.

Previous research had established that mutations in PTPN11 have a conventional cell-autonomous effect on HSC growth.

In the current study, investigators showed that PTPN11 mutations also affect mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (MSPCs) and osteoprogenitors.

The mutations cause over-production of the CC chemokine CCL3, which attracts monocytes into the HSCs’ niches. The monocytes make inflammatory molecules that stimulate the HSCs to differentiate and proliferate, leading to MPNs and leukemia.

“We have identified CCL3 as a potential therapeutic target for controlling leukemic progression in Noonan syndrome and for improving stem cell transplantation therapy in Noonan syndrome-associated leukemias,” said study author Cheng-Kui Qu, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr Qu and his colleagues began this research intending to investigate the effects of PTPN11 mutations in the nervous system. The team developed genetically engineered mice that had altered PTPN11 in neural cells.

The mice all developed a condition resembling an MPN at an early age. It turned out that the mice had changes in the PTPN11 gene in their MSPCs and osteoprogenitors (in addition to their neural cells) but not in their HSCs.

The investigators found the MPN in these PTPN11-mutant mice can be treated in the short-term by HSC transplant, but the condition comes back within months.

However, drugs counteracting CCL3 successfully reversed MPN phenotypes. One of the drugs is the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc, which is approved in the US to combat HIV infection, and another is the CCR1 antagonist BX471.

The investigators noted that other Noonan syndrome mutations, in genes besides PTPN11, need to be assessed for their effects on MPN/leukemia formation. ![]()

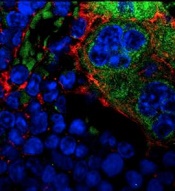

MSPCs with mutant PTPN11

(red) and monocytes (green).

Image courtesy of

Dong et al, Nature 2016

New research published in Nature has shown how certain mutations drive the development of myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) and leukemia.

Investigators discovered that PTPN11 activating mutations promote the development and progression of MPNs through “profound detrimental effects” on hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

The team also identified a potential method of treating MPNs in patients with Noonan syndrome.

Noonan syndrome can be caused by mutations in several genes, but the most common is PTPN11. Children with Noonan syndrome are known to have an increased risk of developing MPNs/leukemia.

Previous research had established that mutations in PTPN11 have a conventional cell-autonomous effect on HSC growth.

In the current study, investigators showed that PTPN11 mutations also affect mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells (MSPCs) and osteoprogenitors.

The mutations cause over-production of the CC chemokine CCL3, which attracts monocytes into the HSCs’ niches. The monocytes make inflammatory molecules that stimulate the HSCs to differentiate and proliferate, leading to MPNs and leukemia.

“We have identified CCL3 as a potential therapeutic target for controlling leukemic progression in Noonan syndrome and for improving stem cell transplantation therapy in Noonan syndrome-associated leukemias,” said study author Cheng-Kui Qu, MD, PhD, of Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dr Qu and his colleagues began this research intending to investigate the effects of PTPN11 mutations in the nervous system. The team developed genetically engineered mice that had altered PTPN11 in neural cells.

The mice all developed a condition resembling an MPN at an early age. It turned out that the mice had changes in the PTPN11 gene in their MSPCs and osteoprogenitors (in addition to their neural cells) but not in their HSCs.

The investigators found the MPN in these PTPN11-mutant mice can be treated in the short-term by HSC transplant, but the condition comes back within months.

However, drugs counteracting CCL3 successfully reversed MPN phenotypes. One of the drugs is the CCR5 antagonist maraviroc, which is approved in the US to combat HIV infection, and another is the CCR1 antagonist BX471.

The investigators noted that other Noonan syndrome mutations, in genes besides PTPN11, need to be assessed for their effects on MPN/leukemia formation. ![]()

Telehealth has value in Parkinson’s and poststroke care

BALTIMORE – The broadening of access to medical care through telemedicine that’s been occurring for acute neurologic conditions such as stroke has begun to expand to care for more chronic conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and poststroke recovery, according to presentations given at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Telemedicine care for patients with Parkinson’s appears feasible and acceptable to both patients and clinicians alike, based on recent findings. Ray Dorsey, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) initiated the Connect.Parkinson study with his colleagues in 2014 to compare usual care enhanced with educational materials against others who received usual care, educational materials, and four virtual sessions with a Parkinson’s disease specialist from 1 of 18 neurology centers nationwide. Some of the participants who lived far away from one of these centers would not otherwise have received such specialized care (Telemed J E Health. 2016;22[7]:590-8).

The participating physicians had concerns about the quality of the video connection, but otherwise were satisfied with the care delivered to the patients. Surveys of participants revealed no differences between the two groups in quality of life and quality of care. About 80% of those who received virtual calls preferred this contact to the regular office visits.

The development of smartphone apps that allow aspects of diseases like Parkinson’s to be monitored are also enabling high-quality, diagnostic telecare. A pilot study of an Android smartphone Parkinson’s disease app by Dr. Dorsey and his colleagues demonstrated its utility in tests of voice, postural sway, gait, finger tapping, and reaction time (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21[6]:650-3).

Since that study was completed, an iOS smartphone version of the app, called mPower, has been developed and has enrolled many Parkinson’s disease patients. The technology is being tested to virtually gauge Parkinson’s disease symptoms and the effects of medications on them. This has opened the door to the world of virtual clinical trials and longitudinal studies targeting genetic subpopulations, Dr. Dorsey said at the meeting.

The telehealth portion of COMPASS – in the form of regular phone calls and web-based feedback – enables better stroke care following hospital discharge by keeping track of common complications that are partly responsible for a readmittance rate of around 25% within 90 days of hospital discharge and tracking physiological aspects like blood pressure, diabetes, diet, exercise, and smoking.

The pilot demonstration of the potential of the program was pivotal in securing funding for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. The trial will randomize hospitals to normal discharge or discharge followed by regular poststroke contact. Patient functional status at 90 days post stroke will be assessed for 1 year. After the year, the hospitals randomized to COMPASS care delivery will continue this care, and the hospitals offering normal discharge will also adopt this poststroke service care. Patient outcome will be followed for another year.

The anticipated patient enrollment is 5,400. Results from the first year of the 2-year study are expected in Spring 2018. “COMPASS will have an impact on the post-acute stroke care pathway. After evaluating the effectiveness, the goal is to disseminate and scale to other settings,” Dr. Bushnell said at the meeting.

Dr. Dorsey receives research support from Excellus BlueCross BlueShield, Google, and the Verizon Foundation. He has received compensation for consulting services for Medtronic and owns stock options in ConsultingMD. Dr. Bushnell acknowledged salary support from the COMPASS program, which receives funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

BALTIMORE – The broadening of access to medical care through telemedicine that’s been occurring for acute neurologic conditions such as stroke has begun to expand to care for more chronic conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and poststroke recovery, according to presentations given at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Telemedicine care for patients with Parkinson’s appears feasible and acceptable to both patients and clinicians alike, based on recent findings. Ray Dorsey, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) initiated the Connect.Parkinson study with his colleagues in 2014 to compare usual care enhanced with educational materials against others who received usual care, educational materials, and four virtual sessions with a Parkinson’s disease specialist from 1 of 18 neurology centers nationwide. Some of the participants who lived far away from one of these centers would not otherwise have received such specialized care (Telemed J E Health. 2016;22[7]:590-8).

The participating physicians had concerns about the quality of the video connection, but otherwise were satisfied with the care delivered to the patients. Surveys of participants revealed no differences between the two groups in quality of life and quality of care. About 80% of those who received virtual calls preferred this contact to the regular office visits.

The development of smartphone apps that allow aspects of diseases like Parkinson’s to be monitored are also enabling high-quality, diagnostic telecare. A pilot study of an Android smartphone Parkinson’s disease app by Dr. Dorsey and his colleagues demonstrated its utility in tests of voice, postural sway, gait, finger tapping, and reaction time (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21[6]:650-3).

Since that study was completed, an iOS smartphone version of the app, called mPower, has been developed and has enrolled many Parkinson’s disease patients. The technology is being tested to virtually gauge Parkinson’s disease symptoms and the effects of medications on them. This has opened the door to the world of virtual clinical trials and longitudinal studies targeting genetic subpopulations, Dr. Dorsey said at the meeting.

The telehealth portion of COMPASS – in the form of regular phone calls and web-based feedback – enables better stroke care following hospital discharge by keeping track of common complications that are partly responsible for a readmittance rate of around 25% within 90 days of hospital discharge and tracking physiological aspects like blood pressure, diabetes, diet, exercise, and smoking.

The pilot demonstration of the potential of the program was pivotal in securing funding for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. The trial will randomize hospitals to normal discharge or discharge followed by regular poststroke contact. Patient functional status at 90 days post stroke will be assessed for 1 year. After the year, the hospitals randomized to COMPASS care delivery will continue this care, and the hospitals offering normal discharge will also adopt this poststroke service care. Patient outcome will be followed for another year.

The anticipated patient enrollment is 5,400. Results from the first year of the 2-year study are expected in Spring 2018. “COMPASS will have an impact on the post-acute stroke care pathway. After evaluating the effectiveness, the goal is to disseminate and scale to other settings,” Dr. Bushnell said at the meeting.

Dr. Dorsey receives research support from Excellus BlueCross BlueShield, Google, and the Verizon Foundation. He has received compensation for consulting services for Medtronic and owns stock options in ConsultingMD. Dr. Bushnell acknowledged salary support from the COMPASS program, which receives funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

BALTIMORE – The broadening of access to medical care through telemedicine that’s been occurring for acute neurologic conditions such as stroke has begun to expand to care for more chronic conditions such as Parkinson’s disease and poststroke recovery, according to presentations given at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Telemedicine care for patients with Parkinson’s appears feasible and acceptable to both patients and clinicians alike, based on recent findings. Ray Dorsey, MD, of the University of Rochester (N.Y.) initiated the Connect.Parkinson study with his colleagues in 2014 to compare usual care enhanced with educational materials against others who received usual care, educational materials, and four virtual sessions with a Parkinson’s disease specialist from 1 of 18 neurology centers nationwide. Some of the participants who lived far away from one of these centers would not otherwise have received such specialized care (Telemed J E Health. 2016;22[7]:590-8).

The participating physicians had concerns about the quality of the video connection, but otherwise were satisfied with the care delivered to the patients. Surveys of participants revealed no differences between the two groups in quality of life and quality of care. About 80% of those who received virtual calls preferred this contact to the regular office visits.

The development of smartphone apps that allow aspects of diseases like Parkinson’s to be monitored are also enabling high-quality, diagnostic telecare. A pilot study of an Android smartphone Parkinson’s disease app by Dr. Dorsey and his colleagues demonstrated its utility in tests of voice, postural sway, gait, finger tapping, and reaction time (Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015;21[6]:650-3).

Since that study was completed, an iOS smartphone version of the app, called mPower, has been developed and has enrolled many Parkinson’s disease patients. The technology is being tested to virtually gauge Parkinson’s disease symptoms and the effects of medications on them. This has opened the door to the world of virtual clinical trials and longitudinal studies targeting genetic subpopulations, Dr. Dorsey said at the meeting.

The telehealth portion of COMPASS – in the form of regular phone calls and web-based feedback – enables better stroke care following hospital discharge by keeping track of common complications that are partly responsible for a readmittance rate of around 25% within 90 days of hospital discharge and tracking physiological aspects like blood pressure, diabetes, diet, exercise, and smoking.

The pilot demonstration of the potential of the program was pivotal in securing funding for a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. The trial will randomize hospitals to normal discharge or discharge followed by regular poststroke contact. Patient functional status at 90 days post stroke will be assessed for 1 year. After the year, the hospitals randomized to COMPASS care delivery will continue this care, and the hospitals offering normal discharge will also adopt this poststroke service care. Patient outcome will be followed for another year.

The anticipated patient enrollment is 5,400. Results from the first year of the 2-year study are expected in Spring 2018. “COMPASS will have an impact on the post-acute stroke care pathway. After evaluating the effectiveness, the goal is to disseminate and scale to other settings,” Dr. Bushnell said at the meeting.

Dr. Dorsey receives research support from Excellus BlueCross BlueShield, Google, and the Verizon Foundation. He has received compensation for consulting services for Medtronic and owns stock options in ConsultingMD. Dr. Bushnell acknowledged salary support from the COMPASS program, which receives funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ANA 2016

Genetic Variations May Affect Vitamin D Level and MS Relapse Rate

BALTIMORE—A genetic scoring system for identifying individuals at high risk for low vitamin D levels also detects patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who have an increased risk for relapse, according to a multicenter cohort study. The findings could have clinical significance in MS treatment and patient counseling, said Jennifer S. Graves, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, at the 141st Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Low vitamin D levels are associated with an increased risk of MS, but whether this association is causal has not been determined. Dr. Graves and her colleagues sought to gain insight into the association by focusing on 29 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within genes that previously had been discovered to be involved in the manufacture of 25-OH vitamin D. The investigators analyzed the relationship of these SNPs to relapses in patients with MS.

They compared the SNP profiles of 181 patients with MS or high-risk clinically isolated syndrome (the discovery cohort) with those of a replication cohort of 110 patients of comparable age, race, and median vitamin D serum level. Patients in the discovery cohort were enrolled at two pediatric MS centers in California between 2006 and 2011, and those in the replication cohort were enrolled at nine MS centers in the United States from 2011 to 2015.

Three of the SNPs were strongly associated with the vitamin D levels in the discovery cohort after a statistical correction that revealed individual influences of genes among the 29 different mutations. The researchers used these three SNPs to generate risk scores for vitamin D levels. The lowest and highest risk scores had linear associations with vitamin D levels. The highest scores were associated with serum vitamin D levels that were nearly 15 ng/mL lower in the discovery and replication cohorts. The risk of MS relapse for individuals with the highest risk score in the discovery cohort was nearly twice as high as it was for individuals with the lowest risk score.

“A genetic score of three functional SNPs captures risk of low vitamin D level and identifies those who may be at risk of relapse related to this risk factor. These findings support a causal association of vitamin D with relapse rate,” Dr. Graves said.

The study may potentially be important beyond MS. “This risk score may also have some utility in other disease states where vitamin D deficiency may be contributing to disease course,” she said.

The study was funded by the Race to Erase MS, the National MS Society, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

—Brian Hoyle

BALTIMORE—A genetic scoring system for identifying individuals at high risk for low vitamin D levels also detects patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who have an increased risk for relapse, according to a multicenter cohort study. The findings could have clinical significance in MS treatment and patient counseling, said Jennifer S. Graves, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, at the 141st Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Low vitamin D levels are associated with an increased risk of MS, but whether this association is causal has not been determined. Dr. Graves and her colleagues sought to gain insight into the association by focusing on 29 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within genes that previously had been discovered to be involved in the manufacture of 25-OH vitamin D. The investigators analyzed the relationship of these SNPs to relapses in patients with MS.

They compared the SNP profiles of 181 patients with MS or high-risk clinically isolated syndrome (the discovery cohort) with those of a replication cohort of 110 patients of comparable age, race, and median vitamin D serum level. Patients in the discovery cohort were enrolled at two pediatric MS centers in California between 2006 and 2011, and those in the replication cohort were enrolled at nine MS centers in the United States from 2011 to 2015.

Three of the SNPs were strongly associated with the vitamin D levels in the discovery cohort after a statistical correction that revealed individual influences of genes among the 29 different mutations. The researchers used these three SNPs to generate risk scores for vitamin D levels. The lowest and highest risk scores had linear associations with vitamin D levels. The highest scores were associated with serum vitamin D levels that were nearly 15 ng/mL lower in the discovery and replication cohorts. The risk of MS relapse for individuals with the highest risk score in the discovery cohort was nearly twice as high as it was for individuals with the lowest risk score.

“A genetic score of three functional SNPs captures risk of low vitamin D level and identifies those who may be at risk of relapse related to this risk factor. These findings support a causal association of vitamin D with relapse rate,” Dr. Graves said.

The study may potentially be important beyond MS. “This risk score may also have some utility in other disease states where vitamin D deficiency may be contributing to disease course,” she said.

The study was funded by the Race to Erase MS, the National MS Society, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

—Brian Hoyle

BALTIMORE—A genetic scoring system for identifying individuals at high risk for low vitamin D levels also detects patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) who have an increased risk for relapse, according to a multicenter cohort study. The findings could have clinical significance in MS treatment and patient counseling, said Jennifer S. Graves, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, at the 141st Annual Meeting of the American Neurological Association.

Low vitamin D levels are associated with an increased risk of MS, but whether this association is causal has not been determined. Dr. Graves and her colleagues sought to gain insight into the association by focusing on 29 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within genes that previously had been discovered to be involved in the manufacture of 25-OH vitamin D. The investigators analyzed the relationship of these SNPs to relapses in patients with MS.

They compared the SNP profiles of 181 patients with MS or high-risk clinically isolated syndrome (the discovery cohort) with those of a replication cohort of 110 patients of comparable age, race, and median vitamin D serum level. Patients in the discovery cohort were enrolled at two pediatric MS centers in California between 2006 and 2011, and those in the replication cohort were enrolled at nine MS centers in the United States from 2011 to 2015.

Three of the SNPs were strongly associated with the vitamin D levels in the discovery cohort after a statistical correction that revealed individual influences of genes among the 29 different mutations. The researchers used these three SNPs to generate risk scores for vitamin D levels. The lowest and highest risk scores had linear associations with vitamin D levels. The highest scores were associated with serum vitamin D levels that were nearly 15 ng/mL lower in the discovery and replication cohorts. The risk of MS relapse for individuals with the highest risk score in the discovery cohort was nearly twice as high as it was for individuals with the lowest risk score.

“A genetic score of three functional SNPs captures risk of low vitamin D level and identifies those who may be at risk of relapse related to this risk factor. These findings support a causal association of vitamin D with relapse rate,” Dr. Graves said.

The study may potentially be important beyond MS. “This risk score may also have some utility in other disease states where vitamin D deficiency may be contributing to disease course,” she said.

The study was funded by the Race to Erase MS, the National MS Society, and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

—Brian Hoyle

Early Epilepsy Increases Risk of Later Comorbid ADHD in Autism

VIENNA—Early-onset idiopathic epilepsy occurring before age 7 nearly doubles the likelihood that a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) will later develop comorbid ADHD, reported Johnny Downs, MD, a child psychiatrist at King’s College in London, at the 29th Annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Comorbid ADHD is common in the setting of ASD. In a search for risk factors for the comorbid condition, Dr. Downs and his colleagues reviewed the physical health records prior to age 7 of 3,032 patients with ASD referred at ages 3 to 17 to child and adolescent mental health services clinics serving South London. “That’s information that often doesn’t make it into the clinical psychiatric record,” said Dr. Downs.

Half of the 3,032 subjects were diagnosed with ASD at ages 6 to 12 and another 39% at ages 13 to 17. During five years of prospective follow-up after being diagnosed with ASD, 25.5% of patients were diagnosed with comorbid ADHD. When reviewing early physical health records, researchers observed that 114 (3.76%) of study participants had experienced early-onset epilepsy before age 7.

A large sample size allowed for robust multivariate adjustment for potential confounders. In a multivariate analysis, patients with ASD and a history of early-onset epilepsy were at a significant 1.75-fold increased risk for subsequent comorbid ADHD. The analysis was adjusted for family history of epilepsy, sociodemographic factors, intellectual disability, previous head injury, perinatal complications, CNS tumors, early meningitis, and other confounders.

Compared with white subjects with ASD, the risk of developing comorbid ADHD was reduced by 37% in black patients and by 52% in Asian patients with ASD.

“The take-home message would be if you’ve got social and communication difficulties in a young child appearing at the age of 5, 6, or 7, and there’s a history of seizures, we are seeing from observational data that the child is at increased risk of ADHD over the age of 7,” said Dr. Downs.

—Bruce Jancin

VIENNA—Early-onset idiopathic epilepsy occurring before age 7 nearly doubles the likelihood that a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) will later develop comorbid ADHD, reported Johnny Downs, MD, a child psychiatrist at King’s College in London, at the 29th Annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Comorbid ADHD is common in the setting of ASD. In a search for risk factors for the comorbid condition, Dr. Downs and his colleagues reviewed the physical health records prior to age 7 of 3,032 patients with ASD referred at ages 3 to 17 to child and adolescent mental health services clinics serving South London. “That’s information that often doesn’t make it into the clinical psychiatric record,” said Dr. Downs.

Half of the 3,032 subjects were diagnosed with ASD at ages 6 to 12 and another 39% at ages 13 to 17. During five years of prospective follow-up after being diagnosed with ASD, 25.5% of patients were diagnosed with comorbid ADHD. When reviewing early physical health records, researchers observed that 114 (3.76%) of study participants had experienced early-onset epilepsy before age 7.

A large sample size allowed for robust multivariate adjustment for potential confounders. In a multivariate analysis, patients with ASD and a history of early-onset epilepsy were at a significant 1.75-fold increased risk for subsequent comorbid ADHD. The analysis was adjusted for family history of epilepsy, sociodemographic factors, intellectual disability, previous head injury, perinatal complications, CNS tumors, early meningitis, and other confounders.

Compared with white subjects with ASD, the risk of developing comorbid ADHD was reduced by 37% in black patients and by 52% in Asian patients with ASD.

“The take-home message would be if you’ve got social and communication difficulties in a young child appearing at the age of 5, 6, or 7, and there’s a history of seizures, we are seeing from observational data that the child is at increased risk of ADHD over the age of 7,” said Dr. Downs.

—Bruce Jancin

VIENNA—Early-onset idiopathic epilepsy occurring before age 7 nearly doubles the likelihood that a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) will later develop comorbid ADHD, reported Johnny Downs, MD, a child psychiatrist at King’s College in London, at the 29th Annual Congress of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology.

Comorbid ADHD is common in the setting of ASD. In a search for risk factors for the comorbid condition, Dr. Downs and his colleagues reviewed the physical health records prior to age 7 of 3,032 patients with ASD referred at ages 3 to 17 to child and adolescent mental health services clinics serving South London. “That’s information that often doesn’t make it into the clinical psychiatric record,” said Dr. Downs.

Half of the 3,032 subjects were diagnosed with ASD at ages 6 to 12 and another 39% at ages 13 to 17. During five years of prospective follow-up after being diagnosed with ASD, 25.5% of patients were diagnosed with comorbid ADHD. When reviewing early physical health records, researchers observed that 114 (3.76%) of study participants had experienced early-onset epilepsy before age 7.

A large sample size allowed for robust multivariate adjustment for potential confounders. In a multivariate analysis, patients with ASD and a history of early-onset epilepsy were at a significant 1.75-fold increased risk for subsequent comorbid ADHD. The analysis was adjusted for family history of epilepsy, sociodemographic factors, intellectual disability, previous head injury, perinatal complications, CNS tumors, early meningitis, and other confounders.

Compared with white subjects with ASD, the risk of developing comorbid ADHD was reduced by 37% in black patients and by 52% in Asian patients with ASD.

“The take-home message would be if you’ve got social and communication difficulties in a young child appearing at the age of 5, 6, or 7, and there’s a history of seizures, we are seeing from observational data that the child is at increased risk of ADHD over the age of 7,” said Dr. Downs.

—Bruce Jancin

Mefloquine labeling falls short on adverse reaction recommendations

The current labeling for the antimalarial mefloquine is inconsistent internationally with medication guides regarding certain adverse reactions, including depression and anxiety, according to a review of drug labels and medication guides from six English-speaking countries.

Neuropsychiatric reactions have been reported by 29% to 77% of mefloquine users at prophylactic doses of 250 mg per week, wrote Remington L. Nevin, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Aricia M. Byrd, an MD student at Trinity School of Medicine, Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. “Neuropsychiatric adverse reactions may occur early during use – frequently within the first three doses – and may even occur after only a single dose,” the researchers said (Neurol Ther. 2016 Jun;5[1]:69-83).

In addition, data suggest that the neuropsychiatric adverse reactions, including nightmares and cognitive dysfunction, can last many years after the drug has been discontinued, and a black box warning was added to the U.S. label in 2013 to emphasize the potential long-term impact, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd reported.

In this study, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd compared prescribing information and patient safety guidance in the United States and five other English-speaking countries: the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

At the time of the study, mefloquine was licensed in all six countries, but the innovator product was withdrawn from the United States in 2011 and from Canada in 2013.

In addition to the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland recommended discontinuing mefloquine at the onset of any general neurologic or psychiatric symptoms, the researchers noted.

All six countries were in complete agreement with corresponding medication guides and drug labeling that recommended discontinuing mefloquine or consulting a healthcare provider if adverse reactions occurred within four high level group terms (HLGTs): anxiety disorders and symptoms, changes in physical activity, depressed mood disorders and disturbances, and deliria (including confusion).

Three of the six countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland) show partial agreement in medication guides and drug labeling recommendations to discontinue the drug or consult a healthcare provider in the instance of three other HLGTs: disturbances in thinking and perception, personality disorders and disturbances in behavior, and suicidal and self-injurious behaviors not elsewhere classified. The United Kingdom and Ireland also showed partial agreement in corresponding medication guides and drug labeling, drug discontinuation, or consulting a healthcare provider for the following adverse reactions: neuromuscular disorders, sleep disorders and disturbances, and peripheral neuropathies.

In the United States alone, medication guides and drug labeling corresponded in terms of drug discontinuation or healthcare provider consultation in cases of cranial nerve disorders, excluding neoplasms and neurologic disorders not elsewhere classified. For nine other areas of adverse reactions, medication guidelines recommended healthcare provider consultation, but no corresponding guidance was found on the drug labeling.

The review was limited by several factors, including the use of data from only six countries and the subjective interpretation of the language used in the drug labeling and medication guides, the researchers noted.

However, the results “suggest opportunities for physicians in these countries to improve patient counseling by specifically emphasizing the need to discontinue at the onset of these adverse reactions,” they said.

“The results of this analysis also suggest opportunities for international drug regulators to clarify language in future updates to remaining mefloquine drug labels and medication guides to better reflect national risk-benefit considerations for continued use of the drug,” they concluded.

Dr. Nevin disclosed that he has been retained as consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving antimalarial drug toxicity claims. Ms. Byrd had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“The big picture is that it is critically important to fund research on mefloquine, because there has been relatively little postmarketing surveillance,” said Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, a forensic psychiatrist with expertise in military and veterans’ issues. Although the risk of neuropsychiatric side effects associated with mefloquine has been known, it has become more recognized in the past 15 years in the United States, she said.

“Dr. Nevin has really been a leader in this area for 10 years; he was a major force in putting the black box warning on this drug that led to the U.S. military dramatically decreasing their use of it,” Dr. Ritchie said.

As for further research, Dr. Ritchie said, “I think we need a good definition of mefloquine toxicity. We need to determine the best medication to treat the neuropsychiatric side effects and determine what part of the brain is affected.”

A systematic review of the side effects also is needed to help determine treatment, she added.

Dr. Ritchie retired from the U.S. Army in 2010 after serving for 24 years and holding many leadership positions, including chief of psychiatry. Currently, Dr. Ritchie is chief of mental health for the community-based outpatient clinics at the Washington VA Medical Center. She also serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University and Howard University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“The big picture is that it is critically important to fund research on mefloquine, because there has been relatively little postmarketing surveillance,” said Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, a forensic psychiatrist with expertise in military and veterans’ issues. Although the risk of neuropsychiatric side effects associated with mefloquine has been known, it has become more recognized in the past 15 years in the United States, she said.

“Dr. Nevin has really been a leader in this area for 10 years; he was a major force in putting the black box warning on this drug that led to the U.S. military dramatically decreasing their use of it,” Dr. Ritchie said.

As for further research, Dr. Ritchie said, “I think we need a good definition of mefloquine toxicity. We need to determine the best medication to treat the neuropsychiatric side effects and determine what part of the brain is affected.”

A systematic review of the side effects also is needed to help determine treatment, she added.

Dr. Ritchie retired from the U.S. Army in 2010 after serving for 24 years and holding many leadership positions, including chief of psychiatry. Currently, Dr. Ritchie is chief of mental health for the community-based outpatient clinics at the Washington VA Medical Center. She also serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University and Howard University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

“The big picture is that it is critically important to fund research on mefloquine, because there has been relatively little postmarketing surveillance,” said Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, a forensic psychiatrist with expertise in military and veterans’ issues. Although the risk of neuropsychiatric side effects associated with mefloquine has been known, it has become more recognized in the past 15 years in the United States, she said.

“Dr. Nevin has really been a leader in this area for 10 years; he was a major force in putting the black box warning on this drug that led to the U.S. military dramatically decreasing their use of it,” Dr. Ritchie said.

As for further research, Dr. Ritchie said, “I think we need a good definition of mefloquine toxicity. We need to determine the best medication to treat the neuropsychiatric side effects and determine what part of the brain is affected.”

A systematic review of the side effects also is needed to help determine treatment, she added.

Dr. Ritchie retired from the U.S. Army in 2010 after serving for 24 years and holding many leadership positions, including chief of psychiatry. Currently, Dr. Ritchie is chief of mental health for the community-based outpatient clinics at the Washington VA Medical Center. She also serves as professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Md., and at Georgetown University and Howard University, both in Washington. She had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The current labeling for the antimalarial mefloquine is inconsistent internationally with medication guides regarding certain adverse reactions, including depression and anxiety, according to a review of drug labels and medication guides from six English-speaking countries.

Neuropsychiatric reactions have been reported by 29% to 77% of mefloquine users at prophylactic doses of 250 mg per week, wrote Remington L. Nevin, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Aricia M. Byrd, an MD student at Trinity School of Medicine, Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. “Neuropsychiatric adverse reactions may occur early during use – frequently within the first three doses – and may even occur after only a single dose,” the researchers said (Neurol Ther. 2016 Jun;5[1]:69-83).

In addition, data suggest that the neuropsychiatric adverse reactions, including nightmares and cognitive dysfunction, can last many years after the drug has been discontinued, and a black box warning was added to the U.S. label in 2013 to emphasize the potential long-term impact, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd reported.

In this study, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd compared prescribing information and patient safety guidance in the United States and five other English-speaking countries: the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

At the time of the study, mefloquine was licensed in all six countries, but the innovator product was withdrawn from the United States in 2011 and from Canada in 2013.

In addition to the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland recommended discontinuing mefloquine at the onset of any general neurologic or psychiatric symptoms, the researchers noted.

All six countries were in complete agreement with corresponding medication guides and drug labeling that recommended discontinuing mefloquine or consulting a healthcare provider if adverse reactions occurred within four high level group terms (HLGTs): anxiety disorders and symptoms, changes in physical activity, depressed mood disorders and disturbances, and deliria (including confusion).

Three of the six countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland) show partial agreement in medication guides and drug labeling recommendations to discontinue the drug or consult a healthcare provider in the instance of three other HLGTs: disturbances in thinking and perception, personality disorders and disturbances in behavior, and suicidal and self-injurious behaviors not elsewhere classified. The United Kingdom and Ireland also showed partial agreement in corresponding medication guides and drug labeling, drug discontinuation, or consulting a healthcare provider for the following adverse reactions: neuromuscular disorders, sleep disorders and disturbances, and peripheral neuropathies.

In the United States alone, medication guides and drug labeling corresponded in terms of drug discontinuation or healthcare provider consultation in cases of cranial nerve disorders, excluding neoplasms and neurologic disorders not elsewhere classified. For nine other areas of adverse reactions, medication guidelines recommended healthcare provider consultation, but no corresponding guidance was found on the drug labeling.

The review was limited by several factors, including the use of data from only six countries and the subjective interpretation of the language used in the drug labeling and medication guides, the researchers noted.

However, the results “suggest opportunities for physicians in these countries to improve patient counseling by specifically emphasizing the need to discontinue at the onset of these adverse reactions,” they said.

“The results of this analysis also suggest opportunities for international drug regulators to clarify language in future updates to remaining mefloquine drug labels and medication guides to better reflect national risk-benefit considerations for continued use of the drug,” they concluded.

Dr. Nevin disclosed that he has been retained as consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving antimalarial drug toxicity claims. Ms. Byrd had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The current labeling for the antimalarial mefloquine is inconsistent internationally with medication guides regarding certain adverse reactions, including depression and anxiety, according to a review of drug labels and medication guides from six English-speaking countries.

Neuropsychiatric reactions have been reported by 29% to 77% of mefloquine users at prophylactic doses of 250 mg per week, wrote Remington L. Nevin, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and Aricia M. Byrd, an MD student at Trinity School of Medicine, Kingstown, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. “Neuropsychiatric adverse reactions may occur early during use – frequently within the first three doses – and may even occur after only a single dose,” the researchers said (Neurol Ther. 2016 Jun;5[1]:69-83).

In addition, data suggest that the neuropsychiatric adverse reactions, including nightmares and cognitive dysfunction, can last many years after the drug has been discontinued, and a black box warning was added to the U.S. label in 2013 to emphasize the potential long-term impact, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd reported.

In this study, Dr. Nevin and Ms. Byrd compared prescribing information and patient safety guidance in the United States and five other English-speaking countries: the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

At the time of the study, mefloquine was licensed in all six countries, but the innovator product was withdrawn from the United States in 2011 and from Canada in 2013.

In addition to the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland recommended discontinuing mefloquine at the onset of any general neurologic or psychiatric symptoms, the researchers noted.

All six countries were in complete agreement with corresponding medication guides and drug labeling that recommended discontinuing mefloquine or consulting a healthcare provider if adverse reactions occurred within four high level group terms (HLGTs): anxiety disorders and symptoms, changes in physical activity, depressed mood disorders and disturbances, and deliria (including confusion).

Three of the six countries (the United States, the United Kingdom, and Ireland) show partial agreement in medication guides and drug labeling recommendations to discontinue the drug or consult a healthcare provider in the instance of three other HLGTs: disturbances in thinking and perception, personality disorders and disturbances in behavior, and suicidal and self-injurious behaviors not elsewhere classified. The United Kingdom and Ireland also showed partial agreement in corresponding medication guides and drug labeling, drug discontinuation, or consulting a healthcare provider for the following adverse reactions: neuromuscular disorders, sleep disorders and disturbances, and peripheral neuropathies.

In the United States alone, medication guides and drug labeling corresponded in terms of drug discontinuation or healthcare provider consultation in cases of cranial nerve disorders, excluding neoplasms and neurologic disorders not elsewhere classified. For nine other areas of adverse reactions, medication guidelines recommended healthcare provider consultation, but no corresponding guidance was found on the drug labeling.

The review was limited by several factors, including the use of data from only six countries and the subjective interpretation of the language used in the drug labeling and medication guides, the researchers noted.

However, the results “suggest opportunities for physicians in these countries to improve patient counseling by specifically emphasizing the need to discontinue at the onset of these adverse reactions,” they said.

“The results of this analysis also suggest opportunities for international drug regulators to clarify language in future updates to remaining mefloquine drug labels and medication guides to better reflect national risk-benefit considerations for continued use of the drug,” they concluded.

Dr. Nevin disclosed that he has been retained as consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving antimalarial drug toxicity claims. Ms. Byrd had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM NEUROLOGY AND THERAPY

Key clinical point: Drug labeling and medication guides are inconsistent in some aspects of recommendations to discontinue use of the antimalarial drug mefloquine in cases of certain neuropsychiatric adverse reactions.

Major finding: All six countries were in complete agreement with corresponding medication guides and drug labeling that recommended discontinuing mefloquine or consulting a healthcare provider if adverse reactions occurred within four high level group terms (HLGTs): anxiety disorders and symptoms, changes in physical activity, depressed mood disorders and disturbances, and deliria (including confusion).

Data source: A review of drug labeling and medication guides in six countries: the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

Disclosures: Dr. Nevin disclosed that he has been retained as consultant and expert witness in legal cases involving antimalarial drug toxicity claims. Ms. Byrd had no financial conflicts to disclose.

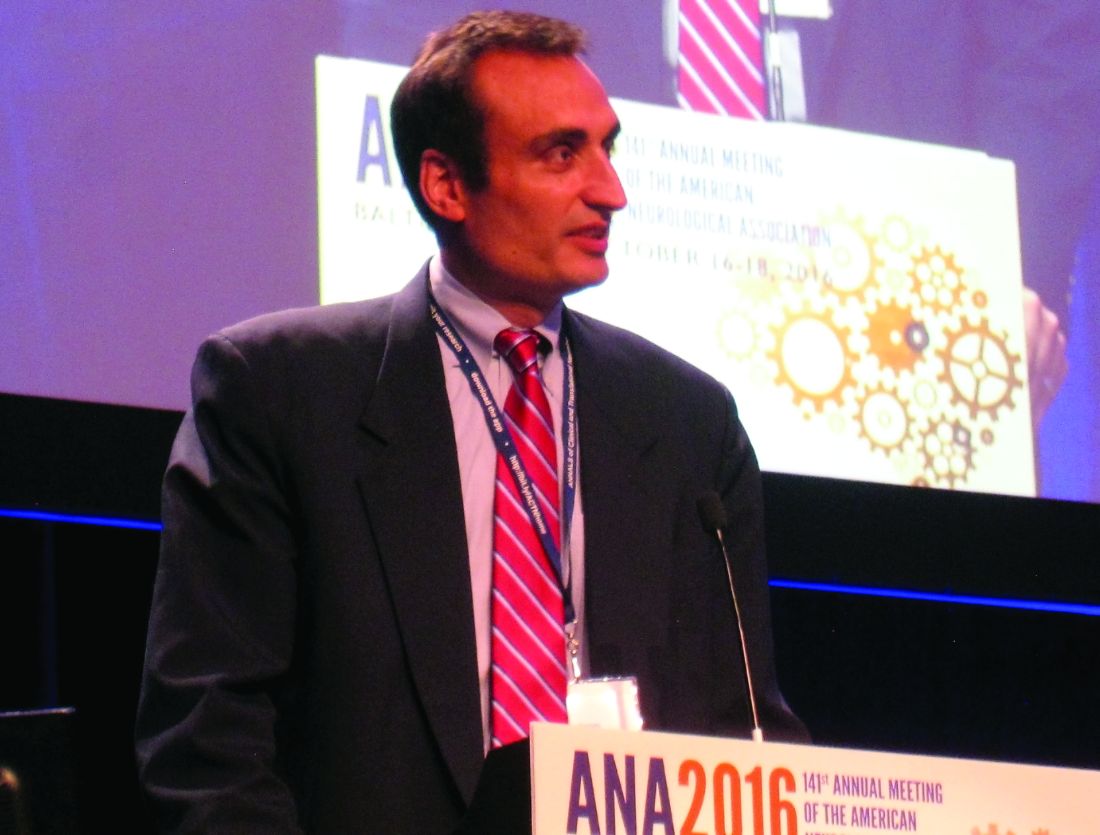

Launching a quality improvement initiative

This article by Adam Weizman and colleagues is the first of a three-part series that will provide practical advice for practices that wish to develop a quality initiative. The first article, “Launching a quality improvement initiative” describes the infrastructure, personnel, and structure needed to approach an identified problem within a practice (variability in adenoma detection rates). This case-based approach helps us understand the step-by-step approach needed to reduce variability and improve quality. The authors present a plan (road map) in a straightforward and practical way that seems simple, but if followed carefully, leads to success. These articles are rich in resources and link to state-of-the-art advice.

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF, Special Section Editor

There has been increasing focus on measuring quality indicators in gastroenterology over the past few years. The adenoma detection rate (ADR) has emerged as one of the most important quality indicators because it is supported by robust clinical evidence.1-3 With every 1% increase in ADR, a 3% reduction in interval colorectal cancer has been noted.3 As such, an ADR of 25% has been designated as an important quality target for all endoscopists who perform colorectal cancer screening.1

You work at a community hospital in a large, metropolitan area. Your colleagues in a number of other departments across your hospital have been increasingly interested in quality improvement (QI) and have launched QI interventions, although none in your department. Moreover, there have been reforms in how hospital endoscopy units are funded in your jurisdiction, with a move toward volume-based funding with a quality overlay. In an effort to improve efficiency and better characterize performance, the hospital has been auditing the performance of all endoscopists at your institution over the past year. Among the eight endoscopists who work at your hospital, the overall ADR has been found to be 19%, decreasing to less than the generally accepted benchmark.1

In response to the results of the audit in your unit, you decide that you would like to develop an initiative to improve your group’s ADR.

Forming a quality improvement team