User login

Veteran Homelessness Drops 47% Since 2010

In the latest Department of Housing and Urban Development annual Point-in-Time (PIT) estimate of America’s homeless population, President Barak Obama revealed that since 2010 the rate of homelessness among veterans has dropped 47%. The January count found 13,000 homeless veterans, although the count fell well short of the President’s pledge to completely eliminate homelessness by 2016. “We will not stop until every veteran who fought for America has a home in America,” President Obama told the national Disabled American Veterans (DAV) convention on August 1. “This is something we’ve got to get done.”

“The dramatic decline in veteran homelessness is the result of the Obama administration’s investments in permanent supportive housing solutions, such as HUD-VASH [Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing] and Supportive Services for Veteran Families programs, extensive community partnerships, coordinated data and outreach, and other proven strategies that put Veterans first,” said VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald in a release. According to the VA, Virginia, Connecticut and 27 cities and towns across the country have “effectively ended” veteran homelessness.

In the DAV speech, President Obama also touted a number of VA health care programs, ranging from rural telehealth initiatives to increased funding for prosthetics and access to women’s health providers at all VA clinics. Pointing out that VA funding has increased during his administration, the President noted that “We’ve made VA benefits available to more than 2 million veterans who didn’t have them before.” The President also pointed out that veterans can apply for VA health care “…from any device, including your smartphone—simple, easy, in as little as 20 minutes.”

The White House also announced that the Million Veteran Program (MVP) had reached a new milestone with 500,000 veterans enrolled. About 62% of MVP enrollees reported a current or past diagnosis of high blood pressure and about one-third reported tinnitus. Also, nearly one-third, or 32%, of veterans present with a history or current diagnosis of cancer. “We believe MVP will accelerate our understanding of disease detection, progression, prevention and treatment by combining this rich clinical, environmental and genomic data,” said VA Under Secretary for Health David J. Shulkin, MD, in a statement. “VA has a deep history of innovation and research. The MVP will allow the nation’s top researchers to perform the most cutting-edge science to treat some of the nation’s most troubling diseases.”

“What this does is it gives us a better understanding of genetics, which will allow us to improve treatments for things like traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress, and diabetes, and cancer,” President Obama told the DAV audience. “And that won’t just help veterans. It will help all Americans. And it’s just one more example of how our veterans keep serving our country even after they come home.”

While Acknowledging the VA’s challenges to meet the needs of veterans, President Obama was insistent that VA care was essential for veterans. “Study after study shows that in many areas, like mental health, the quality of care at the VA is often better than in private care,” he told the DAV members. “So let’s listen to our veterans, who are telling us: Don’t destroy VA health care. Fix it and make it work, but don’t break our covenant with our veterans.”

In the latest Department of Housing and Urban Development annual Point-in-Time (PIT) estimate of America’s homeless population, President Barak Obama revealed that since 2010 the rate of homelessness among veterans has dropped 47%. The January count found 13,000 homeless veterans, although the count fell well short of the President’s pledge to completely eliminate homelessness by 2016. “We will not stop until every veteran who fought for America has a home in America,” President Obama told the national Disabled American Veterans (DAV) convention on August 1. “This is something we’ve got to get done.”

“The dramatic decline in veteran homelessness is the result of the Obama administration’s investments in permanent supportive housing solutions, such as HUD-VASH [Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing] and Supportive Services for Veteran Families programs, extensive community partnerships, coordinated data and outreach, and other proven strategies that put Veterans first,” said VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald in a release. According to the VA, Virginia, Connecticut and 27 cities and towns across the country have “effectively ended” veteran homelessness.

In the DAV speech, President Obama also touted a number of VA health care programs, ranging from rural telehealth initiatives to increased funding for prosthetics and access to women’s health providers at all VA clinics. Pointing out that VA funding has increased during his administration, the President noted that “We’ve made VA benefits available to more than 2 million veterans who didn’t have them before.” The President also pointed out that veterans can apply for VA health care “…from any device, including your smartphone—simple, easy, in as little as 20 minutes.”

The White House also announced that the Million Veteran Program (MVP) had reached a new milestone with 500,000 veterans enrolled. About 62% of MVP enrollees reported a current or past diagnosis of high blood pressure and about one-third reported tinnitus. Also, nearly one-third, or 32%, of veterans present with a history or current diagnosis of cancer. “We believe MVP will accelerate our understanding of disease detection, progression, prevention and treatment by combining this rich clinical, environmental and genomic data,” said VA Under Secretary for Health David J. Shulkin, MD, in a statement. “VA has a deep history of innovation and research. The MVP will allow the nation’s top researchers to perform the most cutting-edge science to treat some of the nation’s most troubling diseases.”

“What this does is it gives us a better understanding of genetics, which will allow us to improve treatments for things like traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress, and diabetes, and cancer,” President Obama told the DAV audience. “And that won’t just help veterans. It will help all Americans. And it’s just one more example of how our veterans keep serving our country even after they come home.”

While Acknowledging the VA’s challenges to meet the needs of veterans, President Obama was insistent that VA care was essential for veterans. “Study after study shows that in many areas, like mental health, the quality of care at the VA is often better than in private care,” he told the DAV members. “So let’s listen to our veterans, who are telling us: Don’t destroy VA health care. Fix it and make it work, but don’t break our covenant with our veterans.”

In the latest Department of Housing and Urban Development annual Point-in-Time (PIT) estimate of America’s homeless population, President Barak Obama revealed that since 2010 the rate of homelessness among veterans has dropped 47%. The January count found 13,000 homeless veterans, although the count fell well short of the President’s pledge to completely eliminate homelessness by 2016. “We will not stop until every veteran who fought for America has a home in America,” President Obama told the national Disabled American Veterans (DAV) convention on August 1. “This is something we’ve got to get done.”

“The dramatic decline in veteran homelessness is the result of the Obama administration’s investments in permanent supportive housing solutions, such as HUD-VASH [Housing and Urban Development-VA Supportive Housing] and Supportive Services for Veteran Families programs, extensive community partnerships, coordinated data and outreach, and other proven strategies that put Veterans first,” said VA Secretary Robert A. McDonald in a release. According to the VA, Virginia, Connecticut and 27 cities and towns across the country have “effectively ended” veteran homelessness.

In the DAV speech, President Obama also touted a number of VA health care programs, ranging from rural telehealth initiatives to increased funding for prosthetics and access to women’s health providers at all VA clinics. Pointing out that VA funding has increased during his administration, the President noted that “We’ve made VA benefits available to more than 2 million veterans who didn’t have them before.” The President also pointed out that veterans can apply for VA health care “…from any device, including your smartphone—simple, easy, in as little as 20 minutes.”

The White House also announced that the Million Veteran Program (MVP) had reached a new milestone with 500,000 veterans enrolled. About 62% of MVP enrollees reported a current or past diagnosis of high blood pressure and about one-third reported tinnitus. Also, nearly one-third, or 32%, of veterans present with a history or current diagnosis of cancer. “We believe MVP will accelerate our understanding of disease detection, progression, prevention and treatment by combining this rich clinical, environmental and genomic data,” said VA Under Secretary for Health David J. Shulkin, MD, in a statement. “VA has a deep history of innovation and research. The MVP will allow the nation’s top researchers to perform the most cutting-edge science to treat some of the nation’s most troubling diseases.”

“What this does is it gives us a better understanding of genetics, which will allow us to improve treatments for things like traumatic brain injury and posttraumatic stress, and diabetes, and cancer,” President Obama told the DAV audience. “And that won’t just help veterans. It will help all Americans. And it’s just one more example of how our veterans keep serving our country even after they come home.”

While Acknowledging the VA’s challenges to meet the needs of veterans, President Obama was insistent that VA care was essential for veterans. “Study after study shows that in many areas, like mental health, the quality of care at the VA is often better than in private care,” he told the DAV members. “So let’s listen to our veterans, who are telling us: Don’t destroy VA health care. Fix it and make it work, but don’t break our covenant with our veterans.”

Preorder 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report

The State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report is the most comprehensive survey of hospital medicine in the country and provides current data on hospitalist compensation and productivity, plus covers practice demographics, staffing levels, staff growth, and compensation models.

Order now and be notified directly when the report is released in September 2016 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

The State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report is the most comprehensive survey of hospital medicine in the country and provides current data on hospitalist compensation and productivity, plus covers practice demographics, staffing levels, staff growth, and compensation models.

Order now and be notified directly when the report is released in September 2016 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

The State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report is the most comprehensive survey of hospital medicine in the country and provides current data on hospitalist compensation and productivity, plus covers practice demographics, staffing levels, staff growth, and compensation models.

Order now and be notified directly when the report is released in September 2016 at www.hospitalmedicine.org/survey.

PAs, NPs: Register for 2016 Adult Hospital Medicine Boot Camp

During the course, you will:

- Learn the most current evidence-based clinical practices for key topics in hospital medicine

- Augment your knowledge base to enhance your existing hospital medicine practice

- Expand your knowledge to transition into hospital medicine practice

- Network with like-minded practitioners

To learn more and register, visit www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

During the course, you will:

- Learn the most current evidence-based clinical practices for key topics in hospital medicine

- Augment your knowledge base to enhance your existing hospital medicine practice

- Expand your knowledge to transition into hospital medicine practice

- Network with like-minded practitioners

To learn more and register, visit www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

During the course, you will:

- Learn the most current evidence-based clinical practices for key topics in hospital medicine

- Augment your knowledge base to enhance your existing hospital medicine practice

- Expand your knowledge to transition into hospital medicine practice

- Network with like-minded practitioners

To learn more and register, visit www.aapa.org/bootcamp.

Gene therapy reduces need for FIX prophylaxis

Image courtesy of NIGMS

ORLANDO—The gene therapy AMT-060 can reduce the need for factor IX (FIX) prophylaxis in patients with severe hemophilia B, results of a phase 1/2 study suggest.

All of the patients treated in the low-dose cohort of this study have had sustained improvements in their disease phenotype and continue to maintain durable levels of FIX gene activity for up to 39 weeks post-treatment.

Four of the 5 patients were able to discontinue prophylactic FIX infusions.

In addition, AMT-060 was considered well-tolerated. There were 2 serious adverse events, but both were temporary. And none of the patients developed FIX inhibitors.

These data were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research is sponsored by uniQure.

“I am very encouraged by the stability of increased FIX activity of AMT-060 and the significant reduction in required infusions of factor replacement,” said study investigator Wolfgang Miesbach, MD, of the University of Frankfurt in Germany.

“This effect is particularly important because it is seen in severe patients with established joint disease who experienced a high frequency of joint bleeds despite intense use of prophylactic FIX prior to study entry.”

Patients and treatment

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type FIX gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform.

In this phase 1/2 trial, Dr Miesbach and his colleagues are testing AMT-060 in 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5x1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2x1013 gc/kg.

Dr Miesbach presented results observed in the low-dose cohort. Patients in the high-dose cohort are still in the early stages of follow-up.

Most patients in the low-dose cohort were older than 50 years of age (range, 35-72). Four patients had severe hemophilia B, and 4 had advanced joint disease. All of the patients had frequent bleeding episodes, despite receiving once- or twice-weekly FIX prophylaxis.

Efficacy

For all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort, the mean annualized total FIX usage declined 75% after treatment with AMT-060.

“The majority of patients in this low-dose cohort of AMT-060 are showing FIX activity in the range of 5% of normal, and clinical experience has shown that patients in this range generally do not require prophylactic factor replacement and have a very low frequency of spontaneous joint bleeding episodes,” Dr Miesbach said.

Four patients discontinued prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylactic therapy has sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

Through up to 9 months of follow-up, the mean steady-state FIX activity for the 4 patients who discontinued prophylactic FIX therapy was 5.4% of normal, with a range from 3.1% to 6.7% of normal. These patients had a mean reduction in annualized total FIX usage of 82%.

Safety and immunogenicity

Two patients experienced serious adverse events. One patient had self-limiting fever in the first 24 hours after receiving AMT-060.

The other patient had a transient elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) that was responsive to tapering prednisolone (60 mg/day start dose) without loss of FIX activity. At baseline, this patient’s ALT was 26 IU/L. It hit a peak of 61 IU/L at week 10, but values returned to baseline levels within 2 weeks of treatment.

As expected, all of the patients developed anti-AAV5 antibodies after week 1. None of the patients developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX.

There was no evidence of sustained AAV5 capsid-specific T-cell activation, although 1 patient had transient T-cell activation slightly above the positive threshold at 1 time point. This patient did not have ALT elevation. ![]()

*Miesbach W et al, Updated results from a dose escalating study in adult patients with haemophilia B treated with AMT-060 (AAV5-hFIX) gene therapy, WFH 2016 World

Congress, July 2016.

Image courtesy of NIGMS

ORLANDO—The gene therapy AMT-060 can reduce the need for factor IX (FIX) prophylaxis in patients with severe hemophilia B, results of a phase 1/2 study suggest.

All of the patients treated in the low-dose cohort of this study have had sustained improvements in their disease phenotype and continue to maintain durable levels of FIX gene activity for up to 39 weeks post-treatment.

Four of the 5 patients were able to discontinue prophylactic FIX infusions.

In addition, AMT-060 was considered well-tolerated. There were 2 serious adverse events, but both were temporary. And none of the patients developed FIX inhibitors.

These data were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research is sponsored by uniQure.

“I am very encouraged by the stability of increased FIX activity of AMT-060 and the significant reduction in required infusions of factor replacement,” said study investigator Wolfgang Miesbach, MD, of the University of Frankfurt in Germany.

“This effect is particularly important because it is seen in severe patients with established joint disease who experienced a high frequency of joint bleeds despite intense use of prophylactic FIX prior to study entry.”

Patients and treatment

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type FIX gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform.

In this phase 1/2 trial, Dr Miesbach and his colleagues are testing AMT-060 in 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5x1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2x1013 gc/kg.

Dr Miesbach presented results observed in the low-dose cohort. Patients in the high-dose cohort are still in the early stages of follow-up.

Most patients in the low-dose cohort were older than 50 years of age (range, 35-72). Four patients had severe hemophilia B, and 4 had advanced joint disease. All of the patients had frequent bleeding episodes, despite receiving once- or twice-weekly FIX prophylaxis.

Efficacy

For all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort, the mean annualized total FIX usage declined 75% after treatment with AMT-060.

“The majority of patients in this low-dose cohort of AMT-060 are showing FIX activity in the range of 5% of normal, and clinical experience has shown that patients in this range generally do not require prophylactic factor replacement and have a very low frequency of spontaneous joint bleeding episodes,” Dr Miesbach said.

Four patients discontinued prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylactic therapy has sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

Through up to 9 months of follow-up, the mean steady-state FIX activity for the 4 patients who discontinued prophylactic FIX therapy was 5.4% of normal, with a range from 3.1% to 6.7% of normal. These patients had a mean reduction in annualized total FIX usage of 82%.

Safety and immunogenicity

Two patients experienced serious adverse events. One patient had self-limiting fever in the first 24 hours after receiving AMT-060.

The other patient had a transient elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) that was responsive to tapering prednisolone (60 mg/day start dose) without loss of FIX activity. At baseline, this patient’s ALT was 26 IU/L. It hit a peak of 61 IU/L at week 10, but values returned to baseline levels within 2 weeks of treatment.

As expected, all of the patients developed anti-AAV5 antibodies after week 1. None of the patients developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX.

There was no evidence of sustained AAV5 capsid-specific T-cell activation, although 1 patient had transient T-cell activation slightly above the positive threshold at 1 time point. This patient did not have ALT elevation. ![]()

*Miesbach W et al, Updated results from a dose escalating study in adult patients with haemophilia B treated with AMT-060 (AAV5-hFIX) gene therapy, WFH 2016 World

Congress, July 2016.

Image courtesy of NIGMS

ORLANDO—The gene therapy AMT-060 can reduce the need for factor IX (FIX) prophylaxis in patients with severe hemophilia B, results of a phase 1/2 study suggest.

All of the patients treated in the low-dose cohort of this study have had sustained improvements in their disease phenotype and continue to maintain durable levels of FIX gene activity for up to 39 weeks post-treatment.

Four of the 5 patients were able to discontinue prophylactic FIX infusions.

In addition, AMT-060 was considered well-tolerated. There were 2 serious adverse events, but both were temporary. And none of the patients developed FIX inhibitors.

These data were presented at the World Federation of Hemophilia 2016 World Congress.* The research is sponsored by uniQure.

“I am very encouraged by the stability of increased FIX activity of AMT-060 and the significant reduction in required infusions of factor replacement,” said study investigator Wolfgang Miesbach, MD, of the University of Frankfurt in Germany.

“This effect is particularly important because it is seen in severe patients with established joint disease who experienced a high frequency of joint bleeds despite intense use of prophylactic FIX prior to study entry.”

Patients and treatment

AMT-060 consists of a codon-optimized wild-type FIX gene cassette, the LP1 liver promoter, and an AAV5 viral vector manufactured by uniQure using its proprietary insect cell-based technology platform.

In this phase 1/2 trial, Dr Miesbach and his colleagues are testing AMT-060 in 10 patients. All patients had severe or moderately severe hemophilia at baseline, including documented FIX levels less than 1% to 2% of normal, and required chronic infusions of prophylactic or on-demand FIX therapy at the time of enrollment.

Each patient received a 1-time, 30-minute, intravenous dose of AMT-060, without the use of corticosteroids. Five patients received AMT-060 at 5x1012 gc/kg, and 5 received AMT-060 at 2x1013 gc/kg.

Dr Miesbach presented results observed in the low-dose cohort. Patients in the high-dose cohort are still in the early stages of follow-up.

Most patients in the low-dose cohort were older than 50 years of age (range, 35-72). Four patients had severe hemophilia B, and 4 had advanced joint disease. All of the patients had frequent bleeding episodes, despite receiving once- or twice-weekly FIX prophylaxis.

Efficacy

For all 5 patients in the low-dose cohort, the mean annualized total FIX usage declined 75% after treatment with AMT-060.

“The majority of patients in this low-dose cohort of AMT-060 are showing FIX activity in the range of 5% of normal, and clinical experience has shown that patients in this range generally do not require prophylactic factor replacement and have a very low frequency of spontaneous joint bleeding episodes,” Dr Miesbach said.

Four patients discontinued prophylactic therapy. The 1 patient who remained on prophylactic therapy has sustained an improved disease phenotype and also required materially less FIX concentrate after treatment with AMT-060.

Through up to 9 months of follow-up, the mean steady-state FIX activity for the 4 patients who discontinued prophylactic FIX therapy was 5.4% of normal, with a range from 3.1% to 6.7% of normal. These patients had a mean reduction in annualized total FIX usage of 82%.

Safety and immunogenicity

Two patients experienced serious adverse events. One patient had self-limiting fever in the first 24 hours after receiving AMT-060.

The other patient had a transient elevation of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) that was responsive to tapering prednisolone (60 mg/day start dose) without loss of FIX activity. At baseline, this patient’s ALT was 26 IU/L. It hit a peak of 61 IU/L at week 10, but values returned to baseline levels within 2 weeks of treatment.

As expected, all of the patients developed anti-AAV5 antibodies after week 1. None of the patients developed inhibitory antibodies against FIX.

There was no evidence of sustained AAV5 capsid-specific T-cell activation, although 1 patient had transient T-cell activation slightly above the positive threshold at 1 time point. This patient did not have ALT elevation. ![]()

*Miesbach W et al, Updated results from a dose escalating study in adult patients with haemophilia B treated with AMT-060 (AAV5-hFIX) gene therapy, WFH 2016 World

Congress, July 2016.

Microneedle system could replace blood draws, team says

Photo courtesy of

Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi

A new microneedle drug monitoring system could one day replace invasive blood draws, according to researchers.

The system consists of a small, thin patch that is pressed against a patient’s arm during medical treatment and measures drugs in the bloodstream painlessly without drawing any blood.

The tiny projections on this patch resemble hollow cones and don’t pierce the skin like a standard hypodermic needle.

The researchers described this system in Scientific Reports.

“Many groups are researching microneedle technology for painless vaccines and drug delivery,” said study author Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. “Using them to painlessly monitor drugs is a newer idea.”

The microneedle system Ranamukhaarachchi and his colleagues created was developed to monitor the antibiotic vancomycin. Patients taking vancomycin must be closely monitored because the drug can cause life-threatening side effects, so the patients undergo 3 to 4 blood draws per day.

The researchers discovered they could use fluid found just below the outer layer of skin, instead of blood, to monitor levels of vancomycin in the bloodstream.

The microneedle patch collects a tiny amount of the fluid, less than 1 nL, and a reaction occurs on the inside of the microneedles that can be detected using an optical sensor. This allows the user to quickly determine the concentration of vancomycin.

“This is probably one of the smallest probe volumes ever recorded for a medically relevant analysis,” said study author Urs Häfeli, PhD, of UBC.

This microneedle drug monitoring system was developed out of a research collaboration between Dr Häfeli and Boris Stoeber, PhD, also of UBC. The system is being commercialized by the UBC spin-off Microdermics Inc. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi

A new microneedle drug monitoring system could one day replace invasive blood draws, according to researchers.

The system consists of a small, thin patch that is pressed against a patient’s arm during medical treatment and measures drugs in the bloodstream painlessly without drawing any blood.

The tiny projections on this patch resemble hollow cones and don’t pierce the skin like a standard hypodermic needle.

The researchers described this system in Scientific Reports.

“Many groups are researching microneedle technology for painless vaccines and drug delivery,” said study author Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. “Using them to painlessly monitor drugs is a newer idea.”

The microneedle system Ranamukhaarachchi and his colleagues created was developed to monitor the antibiotic vancomycin. Patients taking vancomycin must be closely monitored because the drug can cause life-threatening side effects, so the patients undergo 3 to 4 blood draws per day.

The researchers discovered they could use fluid found just below the outer layer of skin, instead of blood, to monitor levels of vancomycin in the bloodstream.

The microneedle patch collects a tiny amount of the fluid, less than 1 nL, and a reaction occurs on the inside of the microneedles that can be detected using an optical sensor. This allows the user to quickly determine the concentration of vancomycin.

“This is probably one of the smallest probe volumes ever recorded for a medically relevant analysis,” said study author Urs Häfeli, PhD, of UBC.

This microneedle drug monitoring system was developed out of a research collaboration between Dr Häfeli and Boris Stoeber, PhD, also of UBC. The system is being commercialized by the UBC spin-off Microdermics Inc. ![]()

Photo courtesy of

Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi

A new microneedle drug monitoring system could one day replace invasive blood draws, according to researchers.

The system consists of a small, thin patch that is pressed against a patient’s arm during medical treatment and measures drugs in the bloodstream painlessly without drawing any blood.

The tiny projections on this patch resemble hollow cones and don’t pierce the skin like a standard hypodermic needle.

The researchers described this system in Scientific Reports.

“Many groups are researching microneedle technology for painless vaccines and drug delivery,” said study author Sahan Ranamukhaarachchi, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. “Using them to painlessly monitor drugs is a newer idea.”

The microneedle system Ranamukhaarachchi and his colleagues created was developed to monitor the antibiotic vancomycin. Patients taking vancomycin must be closely monitored because the drug can cause life-threatening side effects, so the patients undergo 3 to 4 blood draws per day.

The researchers discovered they could use fluid found just below the outer layer of skin, instead of blood, to monitor levels of vancomycin in the bloodstream.

The microneedle patch collects a tiny amount of the fluid, less than 1 nL, and a reaction occurs on the inside of the microneedles that can be detected using an optical sensor. This allows the user to quickly determine the concentration of vancomycin.

“This is probably one of the smallest probe volumes ever recorded for a medically relevant analysis,” said study author Urs Häfeli, PhD, of UBC.

This microneedle drug monitoring system was developed out of a research collaboration between Dr Häfeli and Boris Stoeber, PhD, also of UBC. The system is being commercialized by the UBC spin-off Microdermics Inc. ![]()

FDA approves reconstitution system for FVIII product

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Baxject III reconstitution system for Adynovate, a pegylated recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) product.

The system is designed to mix a FVIII product with a diluent prior to infusion.

The Baxject III reconstitution system was previously FDA-approved for use with Advate, a recombinant FVIII product.

The latest FDA approval means the system will be available with Adynovate as well.

Adynovate and the diluent will come pre-packaged in the reconstitution system.

The Baxject III reconstitution system with Adynovate will be available to most customers in the fourth quarter of 2016, with a 2 mL diluent for the 250, 500, and 1000 IU potencies; and a 5 mL diluent for the 2000 IU potency.

Adynovate was approved by the FDA in 2015 for use in hemophilia A patients age 12 and older for on-demand treatment and control of bleeding and for prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

Advate was first approved by the FDA in 2003. The product is indicated for use in children and adults with hemophilia A for the control and prevention of bleeding episodes, perioperative management, and routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

The Baxject III reconstitution system, Adynovate, and Advate are all products of Baxalta, which is now a part of Shire. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Baxject III reconstitution system for Adynovate, a pegylated recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) product.

The system is designed to mix a FVIII product with a diluent prior to infusion.

The Baxject III reconstitution system was previously FDA-approved for use with Advate, a recombinant FVIII product.

The latest FDA approval means the system will be available with Adynovate as well.

Adynovate and the diluent will come pre-packaged in the reconstitution system.

The Baxject III reconstitution system with Adynovate will be available to most customers in the fourth quarter of 2016, with a 2 mL diluent for the 250, 500, and 1000 IU potencies; and a 5 mL diluent for the 2000 IU potency.

Adynovate was approved by the FDA in 2015 for use in hemophilia A patients age 12 and older for on-demand treatment and control of bleeding and for prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

Advate was first approved by the FDA in 2003. The product is indicated for use in children and adults with hemophilia A for the control and prevention of bleeding episodes, perioperative management, and routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

The Baxject III reconstitution system, Adynovate, and Advate are all products of Baxalta, which is now a part of Shire. ![]()

Photo courtesy of Baxalta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the Baxject III reconstitution system for Adynovate, a pegylated recombinant factor VIII (FVIII) product.

The system is designed to mix a FVIII product with a diluent prior to infusion.

The Baxject III reconstitution system was previously FDA-approved for use with Advate, a recombinant FVIII product.

The latest FDA approval means the system will be available with Adynovate as well.

Adynovate and the diluent will come pre-packaged in the reconstitution system.

The Baxject III reconstitution system with Adynovate will be available to most customers in the fourth quarter of 2016, with a 2 mL diluent for the 250, 500, and 1000 IU potencies; and a 5 mL diluent for the 2000 IU potency.

Adynovate was approved by the FDA in 2015 for use in hemophilia A patients age 12 and older for on-demand treatment and control of bleeding and for prophylaxis to reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

Advate was first approved by the FDA in 2003. The product is indicated for use in children and adults with hemophilia A for the control and prevention of bleeding episodes, perioperative management, and routine prophylaxis to prevent or reduce the frequency of bleeding episodes. Full prescribing information is available here.

The Baxject III reconstitution system, Adynovate, and Advate are all products of Baxalta, which is now a part of Shire. ![]()

HDAC inhibitor granted breakthrough designation

Image by Eric Smith

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor pracinostat to be used in combination with azacitidine to treat newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who are 75 and older or unfit for intensive chemotherapy.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

The breakthrough therapy designation for pracinostat is supported by data from a phase 2 study of the HDAC inhibitor in combination with azacitidine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML who were not candidates for induction chemotherapy.

Detailed results from this trial were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association last year. The research was sponsored by MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

The study included 50 AML patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84).

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

According to updated data from MEI Pharma, the complete response rate was 42% (n=21), and the median overall survival was 19.1 months.

The company said these data compare favorably to a phase 3 study of azacitidine (AZA-AML-0011), which showed a median overall survival of 10.4 months with azacitidine alone and a complete response rate of 19.5% in a similar patient population.

The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine was thought to be well tolerated overall, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events included febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and fatigue. ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor pracinostat to be used in combination with azacitidine to treat newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who are 75 and older or unfit for intensive chemotherapy.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

The breakthrough therapy designation for pracinostat is supported by data from a phase 2 study of the HDAC inhibitor in combination with azacitidine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML who were not candidates for induction chemotherapy.

Detailed results from this trial were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association last year. The research was sponsored by MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

The study included 50 AML patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84).

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

According to updated data from MEI Pharma, the complete response rate was 42% (n=21), and the median overall survival was 19.1 months.

The company said these data compare favorably to a phase 3 study of azacitidine (AZA-AML-0011), which showed a median overall survival of 10.4 months with azacitidine alone and a complete response rate of 19.5% in a similar patient population.

The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine was thought to be well tolerated overall, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events included febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and fatigue. ![]()

Image by Eric Smith

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation for the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor pracinostat to be used in combination with azacitidine to treat newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who are 75 and older or unfit for intensive chemotherapy.

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new therapies for serious or life-threatening conditions.

To earn the designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need.

The breakthrough therapy designation for pracinostat is supported by data from a phase 2 study of the HDAC inhibitor in combination with azacitidine in elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML who were not candidates for induction chemotherapy.

Detailed results from this trial were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association last year. The research was sponsored by MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

The study included 50 AML patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84).

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

According to updated data from MEI Pharma, the complete response rate was 42% (n=21), and the median overall survival was 19.1 months.

The company said these data compare favorably to a phase 3 study of azacitidine (AZA-AML-0011), which showed a median overall survival of 10.4 months with azacitidine alone and a complete response rate of 19.5% in a similar patient population.

The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine was thought to be well tolerated overall, with no unexpected toxicities. The most common grade 3-4 treatment-emergent adverse events included febrile neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and fatigue. ![]()

Overtreatment of Nonpurulent Cellulitis

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 65‐year‐old immunocompetent man with a history of obesity, diabetes, and chronic lower extremity edema presents to the emergency room with a 1‐day history of right lower extremity pain and increased swelling. He reports no antecedent trauma and states he just noticed the symptoms that morning. On examination, he appears generally well. His temperature is 100F, pulse 92 beats per minute, blood pressure 120/60 mm Hg, and respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute. The rest of the exam is notable for right lower extremity erythema and swelling extending from his right shin to his right medial thigh without associated fluctuance or drainage. Labs reveal a mildly elevated white blood cell count of 13,000/L and normal serum creatinine. Are broad‐spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam the preferred regimen?

BACKGROUND

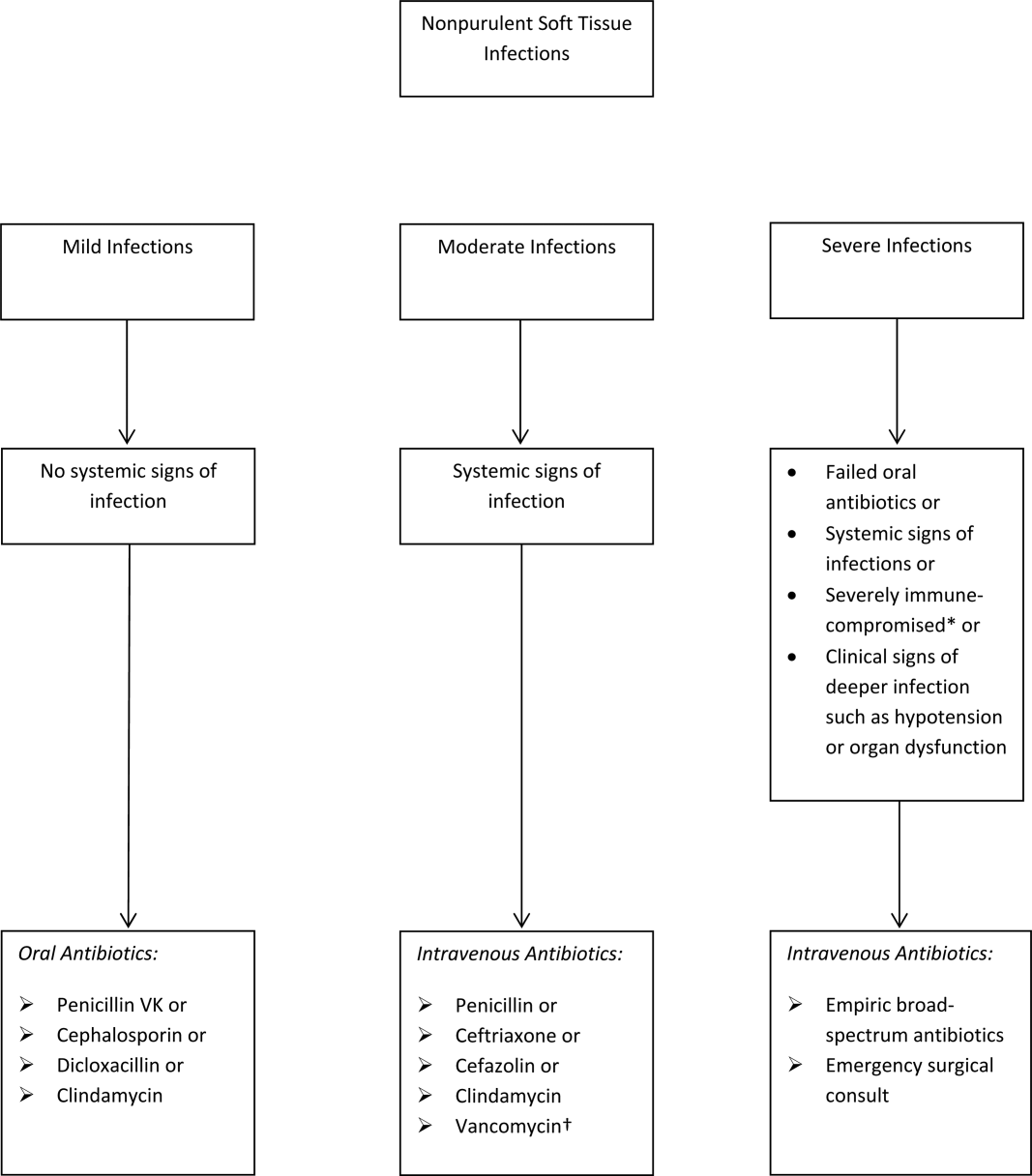

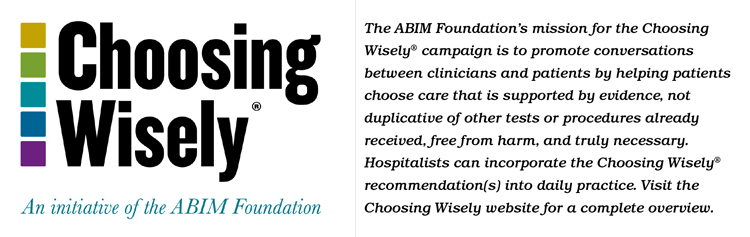

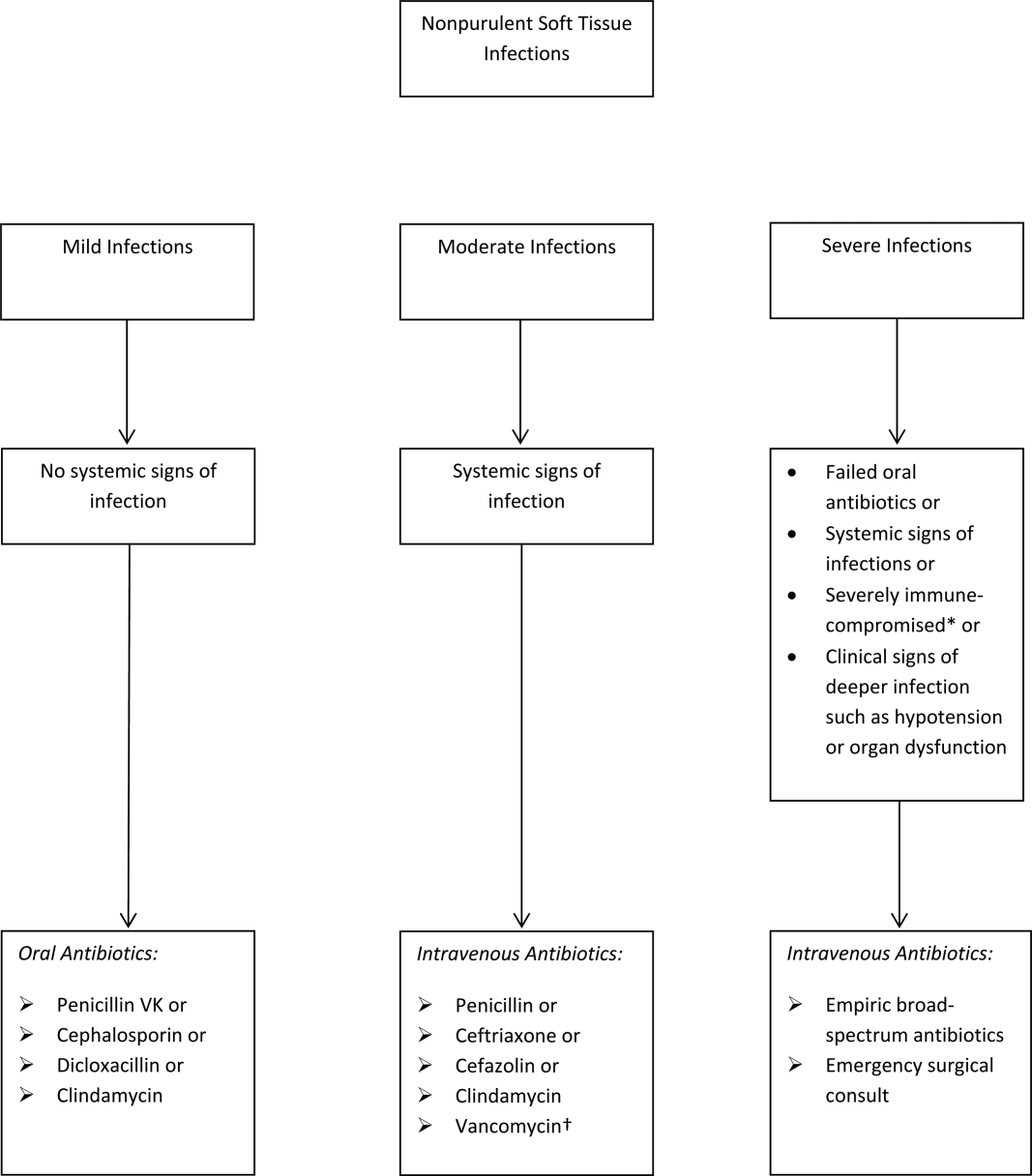

The term skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) includes a heterogeneous group of infections including cellulitis, cutaneous abscess, diabetic foot infections, surgical site infections, and necrotizing soft tissue infections. As a group, SSTIs are the second most common type of infection in hospitalized adults in the United States behind pneumonia and result in more than 600,000 admissions per year.[1] The current guideline on SSTIs by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) makes the distinction between purulent and nonpurulent soft tissue infections based on the presence or absence of purulent drainage or abscess and between mild, moderate, and severe infections based on the presence and severity of systemic signs of infection.[2] Figure 1 provides an overview of the IDSA recommendations.

THE PROBLEM: OVERUSE OF BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS

Studies over the past decade have shown that the majority of patients hospitalized with SSTI receive broad‐spectrum antibiotics, usually with combinations of antibiotics active against gram‐positive (including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]), gram‐negative (often including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and anaerobic organisms. Broad‐spectrum treatment occurs despite guidelines from the IDSA, which state that the most common pathogens for nonpurulent cellulitis are ‐hemolytic streptococci, which remain susceptible to penicillin.[2, 3] One multicenter study of hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis, for example, reported that 85% of patients received therapy effective against MRSA (primarily vancomycin), 61% received broad gram‐negative coverage (primarily ‐lactam with ‐lactamase inhibitor), and 74% received anaerobic coverage.[4] Another multicenter study reported that the most common antibiotics given for cellulitis (excluding cases associated with cutaneous abscess) were vancomycin (60%), ‐lactam/‐lactamase combinations (32%), and clindamycin (19%). Only 13% of patients with cellulitis were treated with cefazolin, and only 1.1% of patients were treated with nafcillin or oxacillin.[5] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unnecessary antibiotic use is associated with increased cost, development of antibiotic resistance, and increased rates of Clostridium difficile.[6]

The current use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics for nonpurulent cellulitis is likely due to several factors, including the emergence of community‐associated (CA)‐MRSA, confusion due to the heterogeneity of SSTI, and the limited data regarding the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis. The resulting uncertainty about cellulitis has been termed an existential crisis for the treating physician and is likely the single biggest factor behind the out‐of‐control prescribing.[7]

The Emergence of CA‐MRSA

Over the past decade, numerous studies have reported the increasing frequency of CA‐MRSA soft tissue infections, predominantly with the pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis type USA‐300. Originally, MRSA infections were limited to nosocomial infections. Subsequent multicenter studies from the United States have shown that CA‐MRSA is the most frequent pathogen isolated from purulent soft tissue infections presenting to emergency rooms[8] and the most frequent pathogen isolated from SSTI specimens in labs.[9] Many authors have therefore concluded that empiric antibiotics for SSTI should include coverage for MRSA.[8, 9]

Heterogeneity of SSTI

As already discussed, the term SSTI is an umbrella term that encompasses several types of clinically distinct infections. The only commonality between the SSTI is that that they all involve the skin and soft tissues in some way. Diabetic foot infections, cutaneous abscesses, surgical site infections, and nonpurulent cellulitis have different hosts, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, and microbiology. At one end of the spectrum is the cutaneous abscess, which is readily culturable through incision and drainage. At the other end of the spectrum is cellulitis, which is typically nonculturable. Unfortunately, studies of SSTI tend to lump all of these entities together when reporting microbiology. The landmark study by Moran et al., for example, described the microbiology of purulent soft tissue infections presenting to a network of emergency rooms across the county. Although all patients had by definition purulent infections, and 81% were abscesses, the authors made broad conclusions about skin and soft tissue infections in general and recommended antimicrobials effective against MRSA for empiric coverage for SSTIs.[8]

Uncertainty About the Microbiology of Nonpurulent Cellulitis

What then is the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis? As stated in the 2005 and 2014 IDSA guidelines, traditional teaching remains that nonpurulent cellulitis is primarily due to ‐hemolytic streptococci.[2, 3] Studies using needle aspiration have yielded conflicting results, although a systematic review of these studies concluded that S aureus was the most common pathogen.[10] On the other hand, a systematic review of positive blood cultures of patients identified as having cellulitis found that 61% were due to ‐hemolytic streptococci, and only 15% were due to S aureus.[11] Both reviews, however, comment on the limited quality of the included studies. Ultimately, because nonpurulent soft tissue infections are basically nonculturable, their true microbiologic etiology remains uncertain. Given this uncertainty, as well as the impressive evidence for CA‐MRSA causing cutaneous abscesses, along with the confusion about types of SSTI, it is not surprising that front‐line clinicians have resorted to prescribing broad‐spectrum antibiotics.

THE SOLUTION: NARROW‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS FOR MOST

Although studies of the microbiology of cellulitis remain inconclusive, several recent clinical trials have indicated that treatment with antimicrobials limited to ‐hemolytic streptococci and methicillin‐susceptible S aureus (MSSA) are as effective as antimicrobials against MRSA. A prospective study from 2010 of consecutive hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis found that 73% had serologic evidence for streptococcal infection, and overall 95.8% responded to cefazolin monotherapy.[12] More recently, a study of emergency room patients with nonpurulent cellulitis randomized patients to cephalexin alone or cephalexin plus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. These authors found no difference in response rates and concluded that the addition of anti‐MRSA therapy (trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, in this study) for uncomplicated cellulitis was unnecessary.[13] This later study is the only randomized controlled study to assess the need for MRSA coverage for cellulitis, and the answer for outpatients, at least, is that MRSA coverage is unnecessary. Both of these studies are cited by the IDSA guideline from 2014, which recommends antibiotics for mild‐moderate cellulitis to be limited to antimicrobials effective against ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA. The guideline specifically does not recommend routinely treating for MRSA, gram‐negative, or anaerobic organisms citing lack of benefit as well as risks of antibiotic resistance and C difficile infection. A recent study from the University of Utah reported the development of a cellulitis order set, which included a pathway for nonpurulent cellulitis based on the use of cefazolin. These authors reported that the use of the pathway was associated with a 59% decrease in the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics, a 23% decrease in pharmacy costs, a 13% decrease in total facility cost, with no change in hospital length of stay or readmission rate.[14] One important caveat to the use of clinical pathways is that they are often underused. In the study from the University of Utah, for example, only 55% of eligible patients had the clinical pathway ordered.

WHEN BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS ARE RECOMMENDED

The IDSA does recommend empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics with combination gram‐positive and gram‐negative coverage in several situations, including severe infections in which necrotizing soft tissue infection is suspected, animal bites, immersion injuries, as well as for severely immunocompromised patients or those who have failed limited spectrum antibiotics. Additionally, the IDSA recommends antimicrobials effective against MRSA for purulent infections with systemic signs of inflammation as well as severe nonpurulent infections or those associated with penetrating trauma, injection drug use, and nasal colonization with MRSA (Figure 1).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our patient has no associated purulence and no abscess and therefore has nonpurulent cellulitis. Based on his mild tachycardia and leukocytosis but intact immune system and lack of suspicion for necrotizing soft tissue infection, he would be classified as moderate‐severity cellulitis by the IDSA. In patients hospitalized with nonpurulent cellulitis who are not severely immunocompromised or severely ill and for whom necrotizing soft tissue infection is not suspected:

- Antibiotics should be directed at ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA, with 1 of the suggested antibiotics by the IDSA including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

- Antibiotics effective against MRSA should be limited to situations described by the IDSA.

- If the cellulitis has not improved within 48 hours, then consider broader‐spectrum antibiotics.

- Hospitals should strongly consider implementation of a cellulitis pathway based on the IDSA recommendations to improve antibiotic stewardship as well as costs.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low‐value practice? Is this truly a Thing We Do for No Reason? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other Things We Do for No Reason topics by emailing [email protected].

- , , . Most frequent conditions in U.S. hospitals, 2011. HCUP statistical brief #162. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project statistical briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 2013.

- , , , et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2):e10–e52.

- , , , et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft‐tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1373–1406.

- , , , , , . Skin and soft‐tissue infections requiring hospitalization at an academic medical center: opportunities for antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(8):895–903.

- , , , , , . A prospective, multicenter, observational study of complicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized patients: clinical characteristics, medical treatment, and outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:227.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overview and evidence to support stewardship. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/evidence.html. Accessed March 2, 2016.

- . Cellulitis, by any other name. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1763–1764.

- , , , et al. Methicillin‐resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(7):666–674.

- , , , , , . Emergence of community‐acquired methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA 300 clone as the predominant cause of skin and soft‐tissue infections. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(5):309–317.

- , . Staphylococcus aureus is the most common identified cause of cellulitis: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(3):313–317.

- , . A systematic review of bacteremias in cellulitis and erysipelas. J Infect. 2012;64(2):148–155.

- , , , . The role of beta‐hemolytic streptococci in causing diffuse, nonculturable cellulitis: a prospective investigation. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89(4):217–226.

- , , , et al. Clinical trial: comparative effectiveness of cephalexin plus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole versus cephalexin alone for treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(12):1754–1762.

- , , , , . Evidence‐based care pathway for cellulitis improves process, clinical, and cost outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2015;10:780–786.

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 65‐year‐old immunocompetent man with a history of obesity, diabetes, and chronic lower extremity edema presents to the emergency room with a 1‐day history of right lower extremity pain and increased swelling. He reports no antecedent trauma and states he just noticed the symptoms that morning. On examination, he appears generally well. His temperature is 100F, pulse 92 beats per minute, blood pressure 120/60 mm Hg, and respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute. The rest of the exam is notable for right lower extremity erythema and swelling extending from his right shin to his right medial thigh without associated fluctuance or drainage. Labs reveal a mildly elevated white blood cell count of 13,000/L and normal serum creatinine. Are broad‐spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam the preferred regimen?

BACKGROUND

The term skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) includes a heterogeneous group of infections including cellulitis, cutaneous abscess, diabetic foot infections, surgical site infections, and necrotizing soft tissue infections. As a group, SSTIs are the second most common type of infection in hospitalized adults in the United States behind pneumonia and result in more than 600,000 admissions per year.[1] The current guideline on SSTIs by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) makes the distinction between purulent and nonpurulent soft tissue infections based on the presence or absence of purulent drainage or abscess and between mild, moderate, and severe infections based on the presence and severity of systemic signs of infection.[2] Figure 1 provides an overview of the IDSA recommendations.

THE PROBLEM: OVERUSE OF BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS

Studies over the past decade have shown that the majority of patients hospitalized with SSTI receive broad‐spectrum antibiotics, usually with combinations of antibiotics active against gram‐positive (including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]), gram‐negative (often including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and anaerobic organisms. Broad‐spectrum treatment occurs despite guidelines from the IDSA, which state that the most common pathogens for nonpurulent cellulitis are ‐hemolytic streptococci, which remain susceptible to penicillin.[2, 3] One multicenter study of hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis, for example, reported that 85% of patients received therapy effective against MRSA (primarily vancomycin), 61% received broad gram‐negative coverage (primarily ‐lactam with ‐lactamase inhibitor), and 74% received anaerobic coverage.[4] Another multicenter study reported that the most common antibiotics given for cellulitis (excluding cases associated with cutaneous abscess) were vancomycin (60%), ‐lactam/‐lactamase combinations (32%), and clindamycin (19%). Only 13% of patients with cellulitis were treated with cefazolin, and only 1.1% of patients were treated with nafcillin or oxacillin.[5] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unnecessary antibiotic use is associated with increased cost, development of antibiotic resistance, and increased rates of Clostridium difficile.[6]

The current use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics for nonpurulent cellulitis is likely due to several factors, including the emergence of community‐associated (CA)‐MRSA, confusion due to the heterogeneity of SSTI, and the limited data regarding the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis. The resulting uncertainty about cellulitis has been termed an existential crisis for the treating physician and is likely the single biggest factor behind the out‐of‐control prescribing.[7]

The Emergence of CA‐MRSA

Over the past decade, numerous studies have reported the increasing frequency of CA‐MRSA soft tissue infections, predominantly with the pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis type USA‐300. Originally, MRSA infections were limited to nosocomial infections. Subsequent multicenter studies from the United States have shown that CA‐MRSA is the most frequent pathogen isolated from purulent soft tissue infections presenting to emergency rooms[8] and the most frequent pathogen isolated from SSTI specimens in labs.[9] Many authors have therefore concluded that empiric antibiotics for SSTI should include coverage for MRSA.[8, 9]

Heterogeneity of SSTI

As already discussed, the term SSTI is an umbrella term that encompasses several types of clinically distinct infections. The only commonality between the SSTI is that that they all involve the skin and soft tissues in some way. Diabetic foot infections, cutaneous abscesses, surgical site infections, and nonpurulent cellulitis have different hosts, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, and microbiology. At one end of the spectrum is the cutaneous abscess, which is readily culturable through incision and drainage. At the other end of the spectrum is cellulitis, which is typically nonculturable. Unfortunately, studies of SSTI tend to lump all of these entities together when reporting microbiology. The landmark study by Moran et al., for example, described the microbiology of purulent soft tissue infections presenting to a network of emergency rooms across the county. Although all patients had by definition purulent infections, and 81% were abscesses, the authors made broad conclusions about skin and soft tissue infections in general and recommended antimicrobials effective against MRSA for empiric coverage for SSTIs.[8]

Uncertainty About the Microbiology of Nonpurulent Cellulitis

What then is the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis? As stated in the 2005 and 2014 IDSA guidelines, traditional teaching remains that nonpurulent cellulitis is primarily due to ‐hemolytic streptococci.[2, 3] Studies using needle aspiration have yielded conflicting results, although a systematic review of these studies concluded that S aureus was the most common pathogen.[10] On the other hand, a systematic review of positive blood cultures of patients identified as having cellulitis found that 61% were due to ‐hemolytic streptococci, and only 15% were due to S aureus.[11] Both reviews, however, comment on the limited quality of the included studies. Ultimately, because nonpurulent soft tissue infections are basically nonculturable, their true microbiologic etiology remains uncertain. Given this uncertainty, as well as the impressive evidence for CA‐MRSA causing cutaneous abscesses, along with the confusion about types of SSTI, it is not surprising that front‐line clinicians have resorted to prescribing broad‐spectrum antibiotics.

THE SOLUTION: NARROW‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS FOR MOST

Although studies of the microbiology of cellulitis remain inconclusive, several recent clinical trials have indicated that treatment with antimicrobials limited to ‐hemolytic streptococci and methicillin‐susceptible S aureus (MSSA) are as effective as antimicrobials against MRSA. A prospective study from 2010 of consecutive hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis found that 73% had serologic evidence for streptococcal infection, and overall 95.8% responded to cefazolin monotherapy.[12] More recently, a study of emergency room patients with nonpurulent cellulitis randomized patients to cephalexin alone or cephalexin plus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. These authors found no difference in response rates and concluded that the addition of anti‐MRSA therapy (trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, in this study) for uncomplicated cellulitis was unnecessary.[13] This later study is the only randomized controlled study to assess the need for MRSA coverage for cellulitis, and the answer for outpatients, at least, is that MRSA coverage is unnecessary. Both of these studies are cited by the IDSA guideline from 2014, which recommends antibiotics for mild‐moderate cellulitis to be limited to antimicrobials effective against ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA. The guideline specifically does not recommend routinely treating for MRSA, gram‐negative, or anaerobic organisms citing lack of benefit as well as risks of antibiotic resistance and C difficile infection. A recent study from the University of Utah reported the development of a cellulitis order set, which included a pathway for nonpurulent cellulitis based on the use of cefazolin. These authors reported that the use of the pathway was associated with a 59% decrease in the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics, a 23% decrease in pharmacy costs, a 13% decrease in total facility cost, with no change in hospital length of stay or readmission rate.[14] One important caveat to the use of clinical pathways is that they are often underused. In the study from the University of Utah, for example, only 55% of eligible patients had the clinical pathway ordered.

WHEN BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS ARE RECOMMENDED

The IDSA does recommend empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics with combination gram‐positive and gram‐negative coverage in several situations, including severe infections in which necrotizing soft tissue infection is suspected, animal bites, immersion injuries, as well as for severely immunocompromised patients or those who have failed limited spectrum antibiotics. Additionally, the IDSA recommends antimicrobials effective against MRSA for purulent infections with systemic signs of inflammation as well as severe nonpurulent infections or those associated with penetrating trauma, injection drug use, and nasal colonization with MRSA (Figure 1).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our patient has no associated purulence and no abscess and therefore has nonpurulent cellulitis. Based on his mild tachycardia and leukocytosis but intact immune system and lack of suspicion for necrotizing soft tissue infection, he would be classified as moderate‐severity cellulitis by the IDSA. In patients hospitalized with nonpurulent cellulitis who are not severely immunocompromised or severely ill and for whom necrotizing soft tissue infection is not suspected:

- Antibiotics should be directed at ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA, with 1 of the suggested antibiotics by the IDSA including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

- Antibiotics effective against MRSA should be limited to situations described by the IDSA.

- If the cellulitis has not improved within 48 hours, then consider broader‐spectrum antibiotics.

- Hospitals should strongly consider implementation of a cellulitis pathway based on the IDSA recommendations to improve antibiotic stewardship as well as costs.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Do you think this is a low‐value practice? Is this truly a Thing We Do for No Reason? Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other Things We Do for No Reason topics by emailing [email protected].

The Things We Do for No Reason (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent black and white conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

A 65‐year‐old immunocompetent man with a history of obesity, diabetes, and chronic lower extremity edema presents to the emergency room with a 1‐day history of right lower extremity pain and increased swelling. He reports no antecedent trauma and states he just noticed the symptoms that morning. On examination, he appears generally well. His temperature is 100F, pulse 92 beats per minute, blood pressure 120/60 mm Hg, and respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute. The rest of the exam is notable for right lower extremity erythema and swelling extending from his right shin to his right medial thigh without associated fluctuance or drainage. Labs reveal a mildly elevated white blood cell count of 13,000/L and normal serum creatinine. Are broad‐spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin and piperacillin/tazobactam the preferred regimen?

BACKGROUND

The term skin and soft tissue infection (SSTI) includes a heterogeneous group of infections including cellulitis, cutaneous abscess, diabetic foot infections, surgical site infections, and necrotizing soft tissue infections. As a group, SSTIs are the second most common type of infection in hospitalized adults in the United States behind pneumonia and result in more than 600,000 admissions per year.[1] The current guideline on SSTIs by the Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) makes the distinction between purulent and nonpurulent soft tissue infections based on the presence or absence of purulent drainage or abscess and between mild, moderate, and severe infections based on the presence and severity of systemic signs of infection.[2] Figure 1 provides an overview of the IDSA recommendations.

THE PROBLEM: OVERUSE OF BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS

Studies over the past decade have shown that the majority of patients hospitalized with SSTI receive broad‐spectrum antibiotics, usually with combinations of antibiotics active against gram‐positive (including methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA]), gram‐negative (often including Pseudomonas aeruginosa), and anaerobic organisms. Broad‐spectrum treatment occurs despite guidelines from the IDSA, which state that the most common pathogens for nonpurulent cellulitis are ‐hemolytic streptococci, which remain susceptible to penicillin.[2, 3] One multicenter study of hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis, for example, reported that 85% of patients received therapy effective against MRSA (primarily vancomycin), 61% received broad gram‐negative coverage (primarily ‐lactam with ‐lactamase inhibitor), and 74% received anaerobic coverage.[4] Another multicenter study reported that the most common antibiotics given for cellulitis (excluding cases associated with cutaneous abscess) were vancomycin (60%), ‐lactam/‐lactamase combinations (32%), and clindamycin (19%). Only 13% of patients with cellulitis were treated with cefazolin, and only 1.1% of patients were treated with nafcillin or oxacillin.[5] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, unnecessary antibiotic use is associated with increased cost, development of antibiotic resistance, and increased rates of Clostridium difficile.[6]

The current use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics for nonpurulent cellulitis is likely due to several factors, including the emergence of community‐associated (CA)‐MRSA, confusion due to the heterogeneity of SSTI, and the limited data regarding the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis. The resulting uncertainty about cellulitis has been termed an existential crisis for the treating physician and is likely the single biggest factor behind the out‐of‐control prescribing.[7]

The Emergence of CA‐MRSA

Over the past decade, numerous studies have reported the increasing frequency of CA‐MRSA soft tissue infections, predominantly with the pulsed‐field gel electrophoresis type USA‐300. Originally, MRSA infections were limited to nosocomial infections. Subsequent multicenter studies from the United States have shown that CA‐MRSA is the most frequent pathogen isolated from purulent soft tissue infections presenting to emergency rooms[8] and the most frequent pathogen isolated from SSTI specimens in labs.[9] Many authors have therefore concluded that empiric antibiotics for SSTI should include coverage for MRSA.[8, 9]

Heterogeneity of SSTI

As already discussed, the term SSTI is an umbrella term that encompasses several types of clinically distinct infections. The only commonality between the SSTI is that that they all involve the skin and soft tissues in some way. Diabetic foot infections, cutaneous abscesses, surgical site infections, and nonpurulent cellulitis have different hosts, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, and microbiology. At one end of the spectrum is the cutaneous abscess, which is readily culturable through incision and drainage. At the other end of the spectrum is cellulitis, which is typically nonculturable. Unfortunately, studies of SSTI tend to lump all of these entities together when reporting microbiology. The landmark study by Moran et al., for example, described the microbiology of purulent soft tissue infections presenting to a network of emergency rooms across the county. Although all patients had by definition purulent infections, and 81% were abscesses, the authors made broad conclusions about skin and soft tissue infections in general and recommended antimicrobials effective against MRSA for empiric coverage for SSTIs.[8]

Uncertainty About the Microbiology of Nonpurulent Cellulitis

What then is the microbiology of nonpurulent cellulitis? As stated in the 2005 and 2014 IDSA guidelines, traditional teaching remains that nonpurulent cellulitis is primarily due to ‐hemolytic streptococci.[2, 3] Studies using needle aspiration have yielded conflicting results, although a systematic review of these studies concluded that S aureus was the most common pathogen.[10] On the other hand, a systematic review of positive blood cultures of patients identified as having cellulitis found that 61% were due to ‐hemolytic streptococci, and only 15% were due to S aureus.[11] Both reviews, however, comment on the limited quality of the included studies. Ultimately, because nonpurulent soft tissue infections are basically nonculturable, their true microbiologic etiology remains uncertain. Given this uncertainty, as well as the impressive evidence for CA‐MRSA causing cutaneous abscesses, along with the confusion about types of SSTI, it is not surprising that front‐line clinicians have resorted to prescribing broad‐spectrum antibiotics.

THE SOLUTION: NARROW‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS FOR MOST

Although studies of the microbiology of cellulitis remain inconclusive, several recent clinical trials have indicated that treatment with antimicrobials limited to ‐hemolytic streptococci and methicillin‐susceptible S aureus (MSSA) are as effective as antimicrobials against MRSA. A prospective study from 2010 of consecutive hospitalized adults with nonpurulent cellulitis found that 73% had serologic evidence for streptococcal infection, and overall 95.8% responded to cefazolin monotherapy.[12] More recently, a study of emergency room patients with nonpurulent cellulitis randomized patients to cephalexin alone or cephalexin plus trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole. These authors found no difference in response rates and concluded that the addition of anti‐MRSA therapy (trimethoprim‐sulfamethoxazole, in this study) for uncomplicated cellulitis was unnecessary.[13] This later study is the only randomized controlled study to assess the need for MRSA coverage for cellulitis, and the answer for outpatients, at least, is that MRSA coverage is unnecessary. Both of these studies are cited by the IDSA guideline from 2014, which recommends antibiotics for mild‐moderate cellulitis to be limited to antimicrobials effective against ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA. The guideline specifically does not recommend routinely treating for MRSA, gram‐negative, or anaerobic organisms citing lack of benefit as well as risks of antibiotic resistance and C difficile infection. A recent study from the University of Utah reported the development of a cellulitis order set, which included a pathway for nonpurulent cellulitis based on the use of cefazolin. These authors reported that the use of the pathway was associated with a 59% decrease in the use of broad‐spectrum antibiotics, a 23% decrease in pharmacy costs, a 13% decrease in total facility cost, with no change in hospital length of stay or readmission rate.[14] One important caveat to the use of clinical pathways is that they are often underused. In the study from the University of Utah, for example, only 55% of eligible patients had the clinical pathway ordered.

WHEN BROAD‐SPECTRUM ANTIBIOTICS ARE RECOMMENDED

The IDSA does recommend empiric broad‐spectrum antibiotics with combination gram‐positive and gram‐negative coverage in several situations, including severe infections in which necrotizing soft tissue infection is suspected, animal bites, immersion injuries, as well as for severely immunocompromised patients or those who have failed limited spectrum antibiotics. Additionally, the IDSA recommends antimicrobials effective against MRSA for purulent infections with systemic signs of inflammation as well as severe nonpurulent infections or those associated with penetrating trauma, injection drug use, and nasal colonization with MRSA (Figure 1).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Our patient has no associated purulence and no abscess and therefore has nonpurulent cellulitis. Based on his mild tachycardia and leukocytosis but intact immune system and lack of suspicion for necrotizing soft tissue infection, he would be classified as moderate‐severity cellulitis by the IDSA. In patients hospitalized with nonpurulent cellulitis who are not severely immunocompromised or severely ill and for whom necrotizing soft tissue infection is not suspected:

- Antibiotics should be directed at ‐hemolytic streptococci and MSSA, with 1 of the suggested antibiotics by the IDSA including penicillin, ceftriaxone, cefazolin, or clindamycin.

- Antibiotics effective against MRSA should be limited to situations described by the IDSA.

- If the cellulitis has not improved within 48 hours, then consider broader‐spectrum antibiotics.

- Hospitals should strongly consider implementation of a cellulitis pathway based on the IDSA recommendations to improve antibiotic stewardship as well as costs.

Disclosure