User login

United States up to 855 cases of Zika in pregnant women

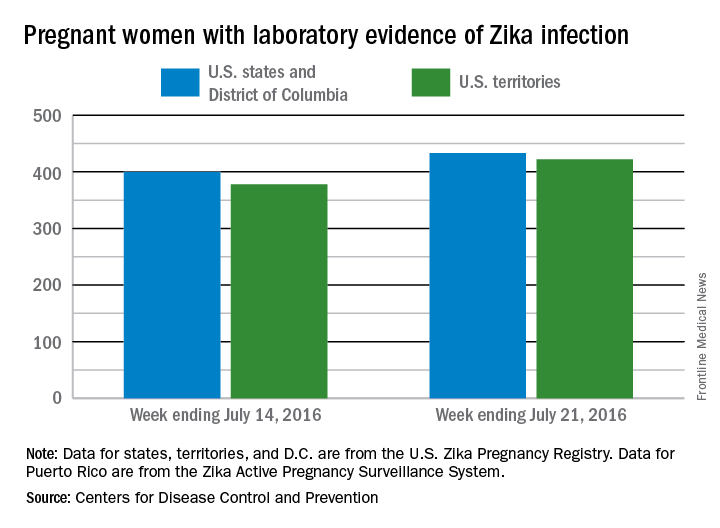

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

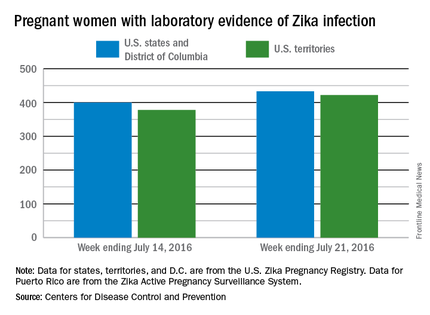

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

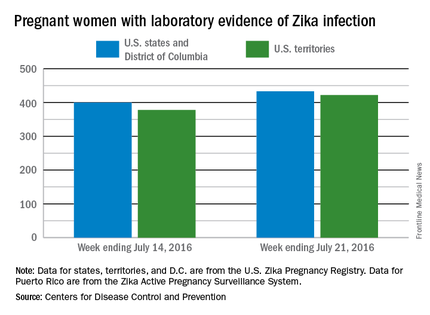

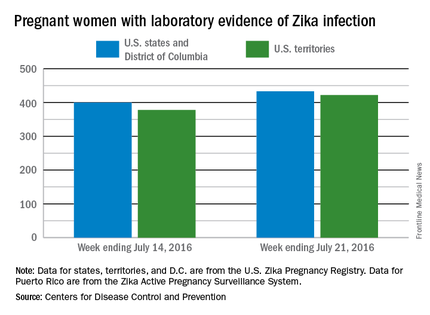

There was one live-born infant with Zika virus–related birth defects and 77 new cases of Zika among pregnant women reported during the week ending July 21, 2016, in the United States, but no additional Zika-related pregnancy losses, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new cases bring the totals to 13 infants born with birth defects and 855 pregnant women with any laboratory evidence of Zika virus infection. All of the infants with birth defects so far were born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia, which is where six of the seven Zika-related pregnancy losses occurred. There has been only one pregnancy loss in the U.S. territories, but the territories account for almost half (422) of the 855 pregnant women with Zika infection. Of the 77 new infections in pregnant women for the week, 44 occurred in the territories and 33 were in the states, the CDC reported July 28.

The figures for states, territories, and the District of Columbia reflect reporting to the U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry; data for Puerto Rico are reported to the U.S. Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System.

Zika-related birth defects recorded by the CDC could include microcephaly, calcium deposits in the brain indicating possible brain damage, excess fluid in the brain cavities and surrounding the brain, absent or poorly formed brain structures, abnormal eye development, or other problems resulting from brain damage that affect nerves, muscles, and bones. The pregnancy losses encompass any miscarriage, stillbirth, and termination with evidence of birth defects.

Aluminum chloride still helps control hyperhidrosis

BOSTON – Aluminum chloride, a chemical found in rocks and as ancient as the earth itself, still can control hyperhidrosis for many people when used correctly. It is the active ingredient in over-the-counter antiperspirants as well as prescription products.

At the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Louis Kuchnir, MD, who is a physical chemist by training as well as a dermatologist, described the chemical properties of aluminum chloride and how it works, based on those properties.

Just as no dermatologist would prescribe isotretinoin for acne without understanding its mechanism of action, so should physicians know how aluminum chloride works to be able to use it effectively, he said. Each aluminum chloride molecule can covalently bind six water molecules and tightly bind another shell or two of 12-20 molecules, with a further third shell, all “making the water very viscous such that the weak muscles that push sweat out of our sweat glands are unable to move the sweat to the surface of our skin,” he said.

“When aluminum chloride gets close to water, it soaks it up and thickens it,” said Dr. Kuchnir, who is in private practice in Marlborough, Mass. “By spreading it over the areas that perspire, it thickens the water in the top of the duct where the sweat’s coming out, and that thickening, like a gel, will block it.” Most people get satisfactory results for a full day from one application of an antiperspirant containing aluminum chloride. A failure to control sweating results from such excessive sweat gland activity that the moisture pushes the gel away from the top of the sweat gland.

Diagnosis of hyperhidrosis

A diagnosis of primary hyperhidrosis requires focal, visible sweating present for at least 6 months with no apparent secondary causes and at least two of the following criteria:

• It is bilateral and symmetric.

• It impairs activities of daily life.

• There is at least one episode per week.

• The age of onset is less than 25 years.

• There is a positive family history.

• There is cessation during sleep.

Patients whose sweating is not controlled with regular antiperspirant deodorants may find relief using an aluminum chloride–containing liquid that is not a classic deodorant. These products are available over the counter. Beyond that, primary care doctors often prescribe a 20% aluminum chloride liquid, which can be very effective.

If a patient still has hyperhidrosis, often of the axillae or the palms of the hand, a dermatologist may recommend injections of botulinum toxin A “to disable sweat glands up to 10 months at a time ... which is a costly procedure that has been heavily marketed over the past 5-10 years,” Dr. Kuchnir said. By asking patients what they have been using and what the problem is, and understanding why aluminum chloride failed them in the past, he has found that he could get “four out of five of these patients to be happy and not perspiring with topical antiperspirants, often prescription strength, even though virtually all of them are ready to go for neurotoxins when I first meet them.” The remaining 20% will need botulinum toxin A to block nerve endings from communicating with the smooth muscle in the eccrine gland, which is required to push sweat out of the gland.

Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis is covered by prescription drug benefit plans, and prior authorization is routine. Patients should obtain the drug at the best price they can find and then bring it to the physician for injection. The duration of action is often 8-10 months, so dosing can be done yearly in the springtime. Aluminum chloride preparations can be retried once botulinum toxin wears off.

Countering common problems with aluminum chloride preparations

The two most common complaints about topical aluminum chloride preparations are that they sting or do not work. Stinging is often from alcohol in the liquids, so letting it evaporate from the armpits before patients put their arms down can solve this problem. As for the problem of not controlling sweating, Dr. Kuchnir said the most common reason is that patients apply the products while they are actively sweating, “so the aluminum chloride doesn’t have time to gel in the eccrine gland.” Another reason is that the preparation has too much moisture in it and will fail to block sweating.

To be able to apply an antiperspirant to dry skin, patients should minimize the causes of sweating by being in a cool, calm environment. The temporary use of anticholinergic drugs may help. Once control of sweating is achieved, the aluminum chloride–containing preparation should be reapplied before it wears off.

Dr. Kuchnir says he encourages dermatologists to bring the same level of care, understanding, and communication to patients suffering from hyperhidrosis that they do to patients whom they see for acne. Just as clinicians do not always use the strongest medicines but choose the safest ones, especially ones that can be self-administered and self-guided, teaching patients how to use antiperspirants when they will work “is as important as being able to effectively and safely inject neurotoxins,” Dr. Kuchnir advised.

While many patients have heard reports of an association between the use of aluminum chloride–containing antiperspirants and a risk of breast cancer or of aluminum in general being associated with Alzheimer’s disease, he says he tells his patients that “aluminum chloride is completely safe, and I don’t say that about a lot of prescription medicines.”

Dr. Kuchnir reported having no financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Aluminum chloride, a chemical found in rocks and as ancient as the earth itself, still can control hyperhidrosis for many people when used correctly. It is the active ingredient in over-the-counter antiperspirants as well as prescription products.

At the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Louis Kuchnir, MD, who is a physical chemist by training as well as a dermatologist, described the chemical properties of aluminum chloride and how it works, based on those properties.

Just as no dermatologist would prescribe isotretinoin for acne without understanding its mechanism of action, so should physicians know how aluminum chloride works to be able to use it effectively, he said. Each aluminum chloride molecule can covalently bind six water molecules and tightly bind another shell or two of 12-20 molecules, with a further third shell, all “making the water very viscous such that the weak muscles that push sweat out of our sweat glands are unable to move the sweat to the surface of our skin,” he said.

“When aluminum chloride gets close to water, it soaks it up and thickens it,” said Dr. Kuchnir, who is in private practice in Marlborough, Mass. “By spreading it over the areas that perspire, it thickens the water in the top of the duct where the sweat’s coming out, and that thickening, like a gel, will block it.” Most people get satisfactory results for a full day from one application of an antiperspirant containing aluminum chloride. A failure to control sweating results from such excessive sweat gland activity that the moisture pushes the gel away from the top of the sweat gland.

Diagnosis of hyperhidrosis

A diagnosis of primary hyperhidrosis requires focal, visible sweating present for at least 6 months with no apparent secondary causes and at least two of the following criteria:

• It is bilateral and symmetric.

• It impairs activities of daily life.

• There is at least one episode per week.

• The age of onset is less than 25 years.

• There is a positive family history.

• There is cessation during sleep.

Patients whose sweating is not controlled with regular antiperspirant deodorants may find relief using an aluminum chloride–containing liquid that is not a classic deodorant. These products are available over the counter. Beyond that, primary care doctors often prescribe a 20% aluminum chloride liquid, which can be very effective.

If a patient still has hyperhidrosis, often of the axillae or the palms of the hand, a dermatologist may recommend injections of botulinum toxin A “to disable sweat glands up to 10 months at a time ... which is a costly procedure that has been heavily marketed over the past 5-10 years,” Dr. Kuchnir said. By asking patients what they have been using and what the problem is, and understanding why aluminum chloride failed them in the past, he has found that he could get “four out of five of these patients to be happy and not perspiring with topical antiperspirants, often prescription strength, even though virtually all of them are ready to go for neurotoxins when I first meet them.” The remaining 20% will need botulinum toxin A to block nerve endings from communicating with the smooth muscle in the eccrine gland, which is required to push sweat out of the gland.

Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis is covered by prescription drug benefit plans, and prior authorization is routine. Patients should obtain the drug at the best price they can find and then bring it to the physician for injection. The duration of action is often 8-10 months, so dosing can be done yearly in the springtime. Aluminum chloride preparations can be retried once botulinum toxin wears off.

Countering common problems with aluminum chloride preparations

The two most common complaints about topical aluminum chloride preparations are that they sting or do not work. Stinging is often from alcohol in the liquids, so letting it evaporate from the armpits before patients put their arms down can solve this problem. As for the problem of not controlling sweating, Dr. Kuchnir said the most common reason is that patients apply the products while they are actively sweating, “so the aluminum chloride doesn’t have time to gel in the eccrine gland.” Another reason is that the preparation has too much moisture in it and will fail to block sweating.

To be able to apply an antiperspirant to dry skin, patients should minimize the causes of sweating by being in a cool, calm environment. The temporary use of anticholinergic drugs may help. Once control of sweating is achieved, the aluminum chloride–containing preparation should be reapplied before it wears off.

Dr. Kuchnir says he encourages dermatologists to bring the same level of care, understanding, and communication to patients suffering from hyperhidrosis that they do to patients whom they see for acne. Just as clinicians do not always use the strongest medicines but choose the safest ones, especially ones that can be self-administered and self-guided, teaching patients how to use antiperspirants when they will work “is as important as being able to effectively and safely inject neurotoxins,” Dr. Kuchnir advised.

While many patients have heard reports of an association between the use of aluminum chloride–containing antiperspirants and a risk of breast cancer or of aluminum in general being associated with Alzheimer’s disease, he says he tells his patients that “aluminum chloride is completely safe, and I don’t say that about a lot of prescription medicines.”

Dr. Kuchnir reported having no financial disclosures.

BOSTON – Aluminum chloride, a chemical found in rocks and as ancient as the earth itself, still can control hyperhidrosis for many people when used correctly. It is the active ingredient in over-the-counter antiperspirants as well as prescription products.

At the American Academy of Dermatology summer meeting, Louis Kuchnir, MD, who is a physical chemist by training as well as a dermatologist, described the chemical properties of aluminum chloride and how it works, based on those properties.

Just as no dermatologist would prescribe isotretinoin for acne without understanding its mechanism of action, so should physicians know how aluminum chloride works to be able to use it effectively, he said. Each aluminum chloride molecule can covalently bind six water molecules and tightly bind another shell or two of 12-20 molecules, with a further third shell, all “making the water very viscous such that the weak muscles that push sweat out of our sweat glands are unable to move the sweat to the surface of our skin,” he said.

“When aluminum chloride gets close to water, it soaks it up and thickens it,” said Dr. Kuchnir, who is in private practice in Marlborough, Mass. “By spreading it over the areas that perspire, it thickens the water in the top of the duct where the sweat’s coming out, and that thickening, like a gel, will block it.” Most people get satisfactory results for a full day from one application of an antiperspirant containing aluminum chloride. A failure to control sweating results from such excessive sweat gland activity that the moisture pushes the gel away from the top of the sweat gland.

Diagnosis of hyperhidrosis

A diagnosis of primary hyperhidrosis requires focal, visible sweating present for at least 6 months with no apparent secondary causes and at least two of the following criteria:

• It is bilateral and symmetric.

• It impairs activities of daily life.

• There is at least one episode per week.

• The age of onset is less than 25 years.

• There is a positive family history.

• There is cessation during sleep.

Patients whose sweating is not controlled with regular antiperspirant deodorants may find relief using an aluminum chloride–containing liquid that is not a classic deodorant. These products are available over the counter. Beyond that, primary care doctors often prescribe a 20% aluminum chloride liquid, which can be very effective.

If a patient still has hyperhidrosis, often of the axillae or the palms of the hand, a dermatologist may recommend injections of botulinum toxin A “to disable sweat glands up to 10 months at a time ... which is a costly procedure that has been heavily marketed over the past 5-10 years,” Dr. Kuchnir said. By asking patients what they have been using and what the problem is, and understanding why aluminum chloride failed them in the past, he has found that he could get “four out of five of these patients to be happy and not perspiring with topical antiperspirants, often prescription strength, even though virtually all of them are ready to go for neurotoxins when I first meet them.” The remaining 20% will need botulinum toxin A to block nerve endings from communicating with the smooth muscle in the eccrine gland, which is required to push sweat out of the gland.

Botulinum toxin for hyperhidrosis is covered by prescription drug benefit plans, and prior authorization is routine. Patients should obtain the drug at the best price they can find and then bring it to the physician for injection. The duration of action is often 8-10 months, so dosing can be done yearly in the springtime. Aluminum chloride preparations can be retried once botulinum toxin wears off.

Countering common problems with aluminum chloride preparations

The two most common complaints about topical aluminum chloride preparations are that they sting or do not work. Stinging is often from alcohol in the liquids, so letting it evaporate from the armpits before patients put their arms down can solve this problem. As for the problem of not controlling sweating, Dr. Kuchnir said the most common reason is that patients apply the products while they are actively sweating, “so the aluminum chloride doesn’t have time to gel in the eccrine gland.” Another reason is that the preparation has too much moisture in it and will fail to block sweating.

To be able to apply an antiperspirant to dry skin, patients should minimize the causes of sweating by being in a cool, calm environment. The temporary use of anticholinergic drugs may help. Once control of sweating is achieved, the aluminum chloride–containing preparation should be reapplied before it wears off.

Dr. Kuchnir says he encourages dermatologists to bring the same level of care, understanding, and communication to patients suffering from hyperhidrosis that they do to patients whom they see for acne. Just as clinicians do not always use the strongest medicines but choose the safest ones, especially ones that can be self-administered and self-guided, teaching patients how to use antiperspirants when they will work “is as important as being able to effectively and safely inject neurotoxins,” Dr. Kuchnir advised.

While many patients have heard reports of an association between the use of aluminum chloride–containing antiperspirants and a risk of breast cancer or of aluminum in general being associated with Alzheimer’s disease, he says he tells his patients that “aluminum chloride is completely safe, and I don’t say that about a lot of prescription medicines.”

Dr. Kuchnir reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AAD SUMMER ACADEMY 2016

The EHR Report: The vortex that sucks you in

Recently, a colleague of ours described the office electronic health record as “the vortex that sucks you in.” This statement occurred during a departmental meeting focused on physician burnout. When members of the department were asked about what things they felt contributed to a feeling of dissatisfaction with work, the electronic health record quickly emerged as a common denominator of dissatisfaction. There were certainly other contributors – the changing and challenging medical environment, fighting with insurance companies, decreased autonomy over practice decisions – but far and away the most cited contributor to dissatisfaction among members of the department was the EHR.

The reasons that EHRs have led to dissatisfaction seem to have changed over the last few years. Initially, physicians found it difficult to suddenly adapt practice styles developed over many years to the new world of electronic documentation. Suddenly they needed to type (or in the case of many, hunt and peck) notes into the history of present illness and fit patient histories into templates seemingly developed by engineers rather than physicians. Now, while most of us have adapted to the logistics of the EHR, there is no escaping the increasing demands for more and more information. There is also ongoing frustration with the lack of control in deciding whether information is relevant for the patient, as well as disparity between the promise and expectation of what electronic records should deliver and what we experience each day in front of us.

Given the degree to which EHRs are contributing to physician dissatisfaction and burnout, it is incumbent upon us to figure out ways to make the EHR work better for clinicians. The literature describes burnout as “a syndrome characterized by a loss of enthusiasm for work (emotional exhaustion), feelings of cynicism (depersonalization), and a low sense of personal accomplishment.” In a recent study, almost half of all physicians described at least one symptom of burnout. Interestingly, physician burnout is greatest in primary care specialties. Surprisingly, compared with other working adults in the United States, physicians are more likely to have symptoms of burnout (38% vs 28%) as well as express dissatisfaction with their work-life balance (40% vs. 23%).1 This issue is important because burnout – in addition to its negative effects on physicians’ experience and quality of life – can erode the quality of the care they give, increase the risk of medical errors, and lead to early ending of lifelong careers.2 The literature suggests that the high prevalence of burnout among U.S. physicians means that “the problem lies more with the system and environment in which physicians work rather than being due to innate vulnerabilities in a few susceptible individuals.” Not surprisingly, we have received letters from readers of our column over many years discussing how the entry of EHRs into their practice was a critical influence in their decisions to retire early.

In our discussion after the department meeting, several physicians described the need to do charting at night from home in order to have their work accomplished for the next day. This is not surprising to any of us who work in primary care and use EHRs. The ability to have access to the EHR anytime and from anywhere is a classic double-edged sword. It is certainly convenient to be able to complete our charting from home without having to stay late in the office on nights and weekends. Unfortunately, bringing work home also erodes into time that could otherwise be spent with family and pursuing other interests.

This is just one of many frustrations. Another common issue is superfluous documentation on the part of specialists. Often, the information is entered by physician extenders or using canned macros to “pad” the note. Sifting through paragraphs of this irrelevant – and sometimes inaccurate – information in consultant notes devalues the integrity of the interaction. It also minimizes the time that was actually spent in the office doing the real hard work of medicine instead of the rudimentary work of documenting things that were either never said or mentioned briefly in passing.

The week after our department meeting was the first week of work for our new interns. Rounding in one of our nursing homes, I handed the intern a patient’s chart and began to explain how the chart was organized – where the orders, progress notes, and labs were located in the chart. The intern had an odd smile on her face. I asked her what was wrong. She replied, “I didn’t know anyone still had paper charts; how do you enter a note there?”

So we come full circle. You can’t miss what you never had. Younger physicians do not resent the EHR, nor can they perceive the EHR to be contributing to discontent. That is not to say that it does not contribute; it is just difficult to identify problems when the way things are is what you have always known. The issue of EHRs contributing to physician burnout is real, and we need to learn more about its causes. Please email us with your thoughts about the aspects of EHRs that you find most frustrating or challenging. Our goal in hearing from you is that it is only by knowing the challenges that we face that we can begin to formulate solutions to overcome those challenges and together make tomorrow’s practice better than today’s.

References

1. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-85.

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

Recently, a colleague of ours described the office electronic health record as “the vortex that sucks you in.” This statement occurred during a departmental meeting focused on physician burnout. When members of the department were asked about what things they felt contributed to a feeling of dissatisfaction with work, the electronic health record quickly emerged as a common denominator of dissatisfaction. There were certainly other contributors – the changing and challenging medical environment, fighting with insurance companies, decreased autonomy over practice decisions – but far and away the most cited contributor to dissatisfaction among members of the department was the EHR.

The reasons that EHRs have led to dissatisfaction seem to have changed over the last few years. Initially, physicians found it difficult to suddenly adapt practice styles developed over many years to the new world of electronic documentation. Suddenly they needed to type (or in the case of many, hunt and peck) notes into the history of present illness and fit patient histories into templates seemingly developed by engineers rather than physicians. Now, while most of us have adapted to the logistics of the EHR, there is no escaping the increasing demands for more and more information. There is also ongoing frustration with the lack of control in deciding whether information is relevant for the patient, as well as disparity between the promise and expectation of what electronic records should deliver and what we experience each day in front of us.

Given the degree to which EHRs are contributing to physician dissatisfaction and burnout, it is incumbent upon us to figure out ways to make the EHR work better for clinicians. The literature describes burnout as “a syndrome characterized by a loss of enthusiasm for work (emotional exhaustion), feelings of cynicism (depersonalization), and a low sense of personal accomplishment.” In a recent study, almost half of all physicians described at least one symptom of burnout. Interestingly, physician burnout is greatest in primary care specialties. Surprisingly, compared with other working adults in the United States, physicians are more likely to have symptoms of burnout (38% vs 28%) as well as express dissatisfaction with their work-life balance (40% vs. 23%).1 This issue is important because burnout – in addition to its negative effects on physicians’ experience and quality of life – can erode the quality of the care they give, increase the risk of medical errors, and lead to early ending of lifelong careers.2 The literature suggests that the high prevalence of burnout among U.S. physicians means that “the problem lies more with the system and environment in which physicians work rather than being due to innate vulnerabilities in a few susceptible individuals.” Not surprisingly, we have received letters from readers of our column over many years discussing how the entry of EHRs into their practice was a critical influence in their decisions to retire early.

In our discussion after the department meeting, several physicians described the need to do charting at night from home in order to have their work accomplished for the next day. This is not surprising to any of us who work in primary care and use EHRs. The ability to have access to the EHR anytime and from anywhere is a classic double-edged sword. It is certainly convenient to be able to complete our charting from home without having to stay late in the office on nights and weekends. Unfortunately, bringing work home also erodes into time that could otherwise be spent with family and pursuing other interests.

This is just one of many frustrations. Another common issue is superfluous documentation on the part of specialists. Often, the information is entered by physician extenders or using canned macros to “pad” the note. Sifting through paragraphs of this irrelevant – and sometimes inaccurate – information in consultant notes devalues the integrity of the interaction. It also minimizes the time that was actually spent in the office doing the real hard work of medicine instead of the rudimentary work of documenting things that were either never said or mentioned briefly in passing.

The week after our department meeting was the first week of work for our new interns. Rounding in one of our nursing homes, I handed the intern a patient’s chart and began to explain how the chart was organized – where the orders, progress notes, and labs were located in the chart. The intern had an odd smile on her face. I asked her what was wrong. She replied, “I didn’t know anyone still had paper charts; how do you enter a note there?”

So we come full circle. You can’t miss what you never had. Younger physicians do not resent the EHR, nor can they perceive the EHR to be contributing to discontent. That is not to say that it does not contribute; it is just difficult to identify problems when the way things are is what you have always known. The issue of EHRs contributing to physician burnout is real, and we need to learn more about its causes. Please email us with your thoughts about the aspects of EHRs that you find most frustrating or challenging. Our goal in hearing from you is that it is only by knowing the challenges that we face that we can begin to formulate solutions to overcome those challenges and together make tomorrow’s practice better than today’s.

References

1. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-85.

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

Recently, a colleague of ours described the office electronic health record as “the vortex that sucks you in.” This statement occurred during a departmental meeting focused on physician burnout. When members of the department were asked about what things they felt contributed to a feeling of dissatisfaction with work, the electronic health record quickly emerged as a common denominator of dissatisfaction. There were certainly other contributors – the changing and challenging medical environment, fighting with insurance companies, decreased autonomy over practice decisions – but far and away the most cited contributor to dissatisfaction among members of the department was the EHR.

The reasons that EHRs have led to dissatisfaction seem to have changed over the last few years. Initially, physicians found it difficult to suddenly adapt practice styles developed over many years to the new world of electronic documentation. Suddenly they needed to type (or in the case of many, hunt and peck) notes into the history of present illness and fit patient histories into templates seemingly developed by engineers rather than physicians. Now, while most of us have adapted to the logistics of the EHR, there is no escaping the increasing demands for more and more information. There is also ongoing frustration with the lack of control in deciding whether information is relevant for the patient, as well as disparity between the promise and expectation of what electronic records should deliver and what we experience each day in front of us.

Given the degree to which EHRs are contributing to physician dissatisfaction and burnout, it is incumbent upon us to figure out ways to make the EHR work better for clinicians. The literature describes burnout as “a syndrome characterized by a loss of enthusiasm for work (emotional exhaustion), feelings of cynicism (depersonalization), and a low sense of personal accomplishment.” In a recent study, almost half of all physicians described at least one symptom of burnout. Interestingly, physician burnout is greatest in primary care specialties. Surprisingly, compared with other working adults in the United States, physicians are more likely to have symptoms of burnout (38% vs 28%) as well as express dissatisfaction with their work-life balance (40% vs. 23%).1 This issue is important because burnout – in addition to its negative effects on physicians’ experience and quality of life – can erode the quality of the care they give, increase the risk of medical errors, and lead to early ending of lifelong careers.2 The literature suggests that the high prevalence of burnout among U.S. physicians means that “the problem lies more with the system and environment in which physicians work rather than being due to innate vulnerabilities in a few susceptible individuals.” Not surprisingly, we have received letters from readers of our column over many years discussing how the entry of EHRs into their practice was a critical influence in their decisions to retire early.

In our discussion after the department meeting, several physicians described the need to do charting at night from home in order to have their work accomplished for the next day. This is not surprising to any of us who work in primary care and use EHRs. The ability to have access to the EHR anytime and from anywhere is a classic double-edged sword. It is certainly convenient to be able to complete our charting from home without having to stay late in the office on nights and weekends. Unfortunately, bringing work home also erodes into time that could otherwise be spent with family and pursuing other interests.

This is just one of many frustrations. Another common issue is superfluous documentation on the part of specialists. Often, the information is entered by physician extenders or using canned macros to “pad” the note. Sifting through paragraphs of this irrelevant – and sometimes inaccurate – information in consultant notes devalues the integrity of the interaction. It also minimizes the time that was actually spent in the office doing the real hard work of medicine instead of the rudimentary work of documenting things that were either never said or mentioned briefly in passing.

The week after our department meeting was the first week of work for our new interns. Rounding in one of our nursing homes, I handed the intern a patient’s chart and began to explain how the chart was organized – where the orders, progress notes, and labs were located in the chart. The intern had an odd smile on her face. I asked her what was wrong. She replied, “I didn’t know anyone still had paper charts; how do you enter a note there?”

So we come full circle. You can’t miss what you never had. Younger physicians do not resent the EHR, nor can they perceive the EHR to be contributing to discontent. That is not to say that it does not contribute; it is just difficult to identify problems when the way things are is what you have always known. The issue of EHRs contributing to physician burnout is real, and we need to learn more about its causes. Please email us with your thoughts about the aspects of EHRs that you find most frustrating or challenging. Our goal in hearing from you is that it is only by knowing the challenges that we face that we can begin to formulate solutions to overcome those challenges and together make tomorrow’s practice better than today’s.

References

1. Shanafelt TD et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among U.S. physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-85.

2. Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995-1000.

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University, Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

Location of UCL Tears May Help Determine If Surgery Is Needed

The location of ligament tears within a pitcher’s elbow can be key to predicting the success of non-operative treatment for injuries, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers examined 38 pitchers from one professional baseball organization (both major and minor league teams) who sustained ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries between 2006 and 2015,. Thirty-two players (84%) received non-operative treatment for partial ligament tears. A proximal tear of the UCL was identified in 81% of the patients who were successfully treated non-operatively. By contrast, a distal tear of the UCL was detected in 90% of patients who failed non-operative treatment and required surgery.

Suggested Reading

Frangiamore S, Lynch TS, Vaugh MD, Soloff L, Schickendantz MS. MRI predictors of failure in non-operative management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in professional baseball pitchers. Paper presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_116.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

The location of ligament tears within a pitcher’s elbow can be key to predicting the success of non-operative treatment for injuries, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers examined 38 pitchers from one professional baseball organization (both major and minor league teams) who sustained ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries between 2006 and 2015,. Thirty-two players (84%) received non-operative treatment for partial ligament tears. A proximal tear of the UCL was identified in 81% of the patients who were successfully treated non-operatively. By contrast, a distal tear of the UCL was detected in 90% of patients who failed non-operative treatment and required surgery.

The location of ligament tears within a pitcher’s elbow can be key to predicting the success of non-operative treatment for injuries, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers examined 38 pitchers from one professional baseball organization (both major and minor league teams) who sustained ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries between 2006 and 2015,. Thirty-two players (84%) received non-operative treatment for partial ligament tears. A proximal tear of the UCL was identified in 81% of the patients who were successfully treated non-operatively. By contrast, a distal tear of the UCL was detected in 90% of patients who failed non-operative treatment and required surgery.

Suggested Reading

Frangiamore S, Lynch TS, Vaugh MD, Soloff L, Schickendantz MS. MRI predictors of failure in non-operative management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in professional baseball pitchers. Paper presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_116.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

Suggested Reading

Frangiamore S, Lynch TS, Vaugh MD, Soloff L, Schickendantz MS. MRI predictors of failure in non-operative management of ulnar collateral ligament injuries in professional baseball pitchers. Paper presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_116.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

Women Under Age 25 at Greater Risk for ACL Re-Tear

After anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, women younger than age 25 with a graft size of <8 mm have an increased change of re-tearing their ACL, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers studied 503 athletes (235 women and 268 men; average age 27) undergoing primary, autograft hamstring ACL reconstruction. The surgeries were all performed at a single center by a single surgeon between September through December 2012. Patients were followed for 2 years. Overall, the rate of re-tears was 6% and the mean graft size was 7.9 mm.

Graft size <8 mm and age < 25 years were significantly predictive of re‐tear. Female sex was correlated with re‐tear but was not significant.

Suggested Reading

Nguyen D. Sex, age, and graft size as predictors of ACL: re‐tear: a multivariate logistic regression of a cohort of 503 athletes. Paper presented at 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_111.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

After anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, women younger than age 25 with a graft size of <8 mm have an increased change of re-tearing their ACL, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers studied 503 athletes (235 women and 268 men; average age 27) undergoing primary, autograft hamstring ACL reconstruction. The surgeries were all performed at a single center by a single surgeon between September through December 2012. Patients were followed for 2 years. Overall, the rate of re-tears was 6% and the mean graft size was 7.9 mm.

Graft size <8 mm and age < 25 years were significantly predictive of re‐tear. Female sex was correlated with re‐tear but was not significant.

After anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, women younger than age 25 with a graft size of <8 mm have an increased change of re-tearing their ACL, according to the results of a study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine.

Researchers studied 503 athletes (235 women and 268 men; average age 27) undergoing primary, autograft hamstring ACL reconstruction. The surgeries were all performed at a single center by a single surgeon between September through December 2012. Patients were followed for 2 years. Overall, the rate of re-tears was 6% and the mean graft size was 7.9 mm.

Graft size <8 mm and age < 25 years were significantly predictive of re‐tear. Female sex was correlated with re‐tear but was not significant.

Suggested Reading

Nguyen D. Sex, age, and graft size as predictors of ACL: re‐tear: a multivariate logistic regression of a cohort of 503 athletes. Paper presented at 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_111.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

Suggested Reading

Nguyen D. Sex, age, and graft size as predictors of ACL: re‐tear: a multivariate logistic regression of a cohort of 503 athletes. Paper presented at 2016 annual meeting of the American Orthopedic Society of Sports Medicine. Available at: http://apps.sportsmed.org/meetings/am2016/files/Paper_111.pdf. Accessed July 29, 2016.

How Do Age, Sex Affect Outcomes After Arthroscopy for Hip Impingement?

Although both men and women generally do well after having arthroscopic surgery for hip impingement, patients over age 45, particularly women over 45, don’t fare quite as well, according to a study published May 18 in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

Researchers examined 150 men and women of various ages, who underwent hip arthroscopy to treat femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). Patients were divided into groups based on age and sex. Outcomes were evaluated based on results from several instruments, include the Hip Outcome Score Activities of Daily Living Subscale, Hip Outcome Score Sport-Specific Subscale, and modified Harris hip score, as well as by clinical improvement at follow-up.

Researchers found that while all patients had significant improvements after hip arthroscopy for FAI, patients under age 45 had better overall results and fewer complications compared with people over age 45. Women older than age 45 had lower outcome scores than their male counterparts.

Suggested Reading

Frank MR, Lee S, Bush-Joseph C, et al. Outcomes for hip arthroscopy according to sex and age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(10):797-804.

Although both men and women generally do well after having arthroscopic surgery for hip impingement, patients over age 45, particularly women over 45, don’t fare quite as well, according to a study published May 18 in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

Researchers examined 150 men and women of various ages, who underwent hip arthroscopy to treat femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). Patients were divided into groups based on age and sex. Outcomes were evaluated based on results from several instruments, include the Hip Outcome Score Activities of Daily Living Subscale, Hip Outcome Score Sport-Specific Subscale, and modified Harris hip score, as well as by clinical improvement at follow-up.

Researchers found that while all patients had significant improvements after hip arthroscopy for FAI, patients under age 45 had better overall results and fewer complications compared with people over age 45. Women older than age 45 had lower outcome scores than their male counterparts.

Although both men and women generally do well after having arthroscopic surgery for hip impingement, patients over age 45, particularly women over 45, don’t fare quite as well, according to a study published May 18 in The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

Researchers examined 150 men and women of various ages, who underwent hip arthroscopy to treat femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). Patients were divided into groups based on age and sex. Outcomes were evaluated based on results from several instruments, include the Hip Outcome Score Activities of Daily Living Subscale, Hip Outcome Score Sport-Specific Subscale, and modified Harris hip score, as well as by clinical improvement at follow-up.

Researchers found that while all patients had significant improvements after hip arthroscopy for FAI, patients under age 45 had better overall results and fewer complications compared with people over age 45. Women older than age 45 had lower outcome scores than their male counterparts.

Suggested Reading

Frank MR, Lee S, Bush-Joseph C, et al. Outcomes for hip arthroscopy according to sex and age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(10):797-804.

Suggested Reading

Frank MR, Lee S, Bush-Joseph C, et al. Outcomes for hip arthroscopy according to sex and age. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(10):797-804.

C6 EIA testing can guide Lyme disease treatment in children

The C6 Lyme enzyme immunoassay is an effective diagnostic tool for children who are being tested for Lyme disease, according to Susan C. Lipsett, MD, and her associates.

Of the 944 samples collected for the study, 114 were positive for Lyme disease. The sensitivity of C6 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing alone was 79.8% and the specificity was 94.2%, slightly less than the standard two-tiered testing approach, which had a sensitivity of 81.6% and a specificity of 98.8%. The specificity of C6 EIA testing was increased to 98.6% when a supplemental immunoblot was added to testing.

The specificity of C6 EIA testing alone was significantly lower than standard testing in the control group. When the supplemental immunoblot was added to testing, the specificity of C6 EIA testing did match the specificity of standard testing in children who did not have Lyme disease.

“Although supplemental immunoblots are still required to confirm a Lyme disease diagnosis, our study supports using the C6 EIA as a first-line diagnostic test in children undergoing evaluation for Lyme disease. In the appropriate clinical scenario, the C6 EIA could limit unnecessary procedures and allow for prompt initiation of appropriate therapy,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi:10.1093/cid/ciw427).

The C6 Lyme enzyme immunoassay is an effective diagnostic tool for children who are being tested for Lyme disease, according to Susan C. Lipsett, MD, and her associates.

Of the 944 samples collected for the study, 114 were positive for Lyme disease. The sensitivity of C6 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing alone was 79.8% and the specificity was 94.2%, slightly less than the standard two-tiered testing approach, which had a sensitivity of 81.6% and a specificity of 98.8%. The specificity of C6 EIA testing was increased to 98.6% when a supplemental immunoblot was added to testing.

The specificity of C6 EIA testing alone was significantly lower than standard testing in the control group. When the supplemental immunoblot was added to testing, the specificity of C6 EIA testing did match the specificity of standard testing in children who did not have Lyme disease.

“Although supplemental immunoblots are still required to confirm a Lyme disease diagnosis, our study supports using the C6 EIA as a first-line diagnostic test in children undergoing evaluation for Lyme disease. In the appropriate clinical scenario, the C6 EIA could limit unnecessary procedures and allow for prompt initiation of appropriate therapy,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi:10.1093/cid/ciw427).

The C6 Lyme enzyme immunoassay is an effective diagnostic tool for children who are being tested for Lyme disease, according to Susan C. Lipsett, MD, and her associates.

Of the 944 samples collected for the study, 114 were positive for Lyme disease. The sensitivity of C6 enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing alone was 79.8% and the specificity was 94.2%, slightly less than the standard two-tiered testing approach, which had a sensitivity of 81.6% and a specificity of 98.8%. The specificity of C6 EIA testing was increased to 98.6% when a supplemental immunoblot was added to testing.

The specificity of C6 EIA testing alone was significantly lower than standard testing in the control group. When the supplemental immunoblot was added to testing, the specificity of C6 EIA testing did match the specificity of standard testing in children who did not have Lyme disease.

“Although supplemental immunoblots are still required to confirm a Lyme disease diagnosis, our study supports using the C6 EIA as a first-line diagnostic test in children undergoing evaluation for Lyme disease. In the appropriate clinical scenario, the C6 EIA could limit unnecessary procedures and allow for prompt initiation of appropriate therapy,” the investigators concluded.

Find the full study in Clinical Infectious Diseases (doi:10.1093/cid/ciw427).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

Law & Medicine: Discovery rule and statute of limitations

Question: In July 2002, a patient in California underwent surgery for a herniated T8-9 disk, but the surgeon instead removed the T6-7 and T7-8 disks. On Sept. 11, 2002, the surgeon discussed with the patient the MRI findings showing his mistake. On Sept. 17, 2003, the patient filed a malpractice lawsuit, just 6 days beyond California’s 1-year limitations period. California subscribes to the discovery rule, that is, a cause of action accrues only when a claimant discovers or should have discovered injury was the result of negligence.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. The lawsuit filed Sept. 17, 2003, is time barred, as the negligent surgery took place in July 2002.

B. On its face, the lawsuit was filed too late, being 1 year and 6 days after the Sept. 11, 2002, discussion date.

C. The lawsuit was timely filed, so long as the claimant can prove he was out of town for more than 6 days of that year.

D. The patient should sue as an action in battery, which has a longer statute of limitations.

E. All choices except A are correct.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although an equitable doctrine of laches existed to foreclose an action that had long lapsed. Statutory changes in the law now require that lawsuits be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable.

Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, that is, relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. This time period, during which a lawsuit must be filed or it will be barred, is termed the statute of limitations. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, with states such as California and Tennessee placing a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims. In California, the running of the statute is tolled (temporarily halted) for the days a claimant is out of state.

The above case scenario is taken from Kaplan v. Mamelak,1 where the plaintiff’s lawsuit was not barred to allow him to identify the number of days he was out of town. The court also permitted a cause of action in battery, which is covered under a longer statute of limitations, as well as one sounding in malpractice.

Patients who are injured from malpractice may not always be aware that a negligent act had taken place, and some injuries may remain latent for a long period. Recognizing this, statutes of limitation emphasize the date when the plaintiff first discovered that the injury resulted from negligence. This is termed the discovery rule.

Stated more formally, the limitations period commences at the time the cause of action (negligence or other wrongs) accrues, and this usually means when the claimant knew (actual knowledge) or should have known (constructive knowledge).

The rule, in the words of one court, is meant to balance the need for “prompt assertion of claims” against a policy “favoring adjudication of claims on the merits and ensuring that a party with a valid claim will be given an opportunity to present it.”

As is typical of other jurisdictions, Hawaii sought to clarify the discovery rule in a series of court cases, beginning with Yoshizaki v. Hilo Hospital,2 where the court deemed a cause of action “does not begin to run until the plaintiff knew or should have known of the defendant’s negligence.”

Subsequently, Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals explained that the state’s 2-year limitations statute commences when the plaintiff discovers, or through the use of reasonable diligence should have discovered, 1) the damage; 2) the violation of the duty; and 3) the causal connection between the violation of the duty and the damage.3

The court subsequently held that the rule prevents the running of the limitations period until “the plaintiff [has] knowledge of those facts which are necessary for an actionable claim.”4 In 1999, the Hawaii Supreme Court clarified that it was “factual knowledge,” rather than “legal knowledge,” that starts the clock running, and that legal knowledge of a defendant’s negligence was not required.5

More recently, litigation over the time barring of claims was evident in Moon v. Rhode,6 where Dr. Clarissa Rhode and Central Illinois Radiological Associates were sued for negligently misreading a patient’s CT scans.

The 90-year-old patient, Kathryn Moon, was admitted to Proctor Hospital May 18, 2009, and died 11 days later following surgery and complications of fluid overload and a pneumoperitoneum. Dr. Rhode, a radiologist, interpreted two CT scans, which an independent expert in 2013 determined were negligently misread. A lawsuit was then brought against Dr. Rhode, who was not a named defendant when the plaintiff had timely filed a medical negligence action back in 2011 against the surgeon and the attending doctor.

The court of appeals held that the discovery rule can be applied to wrongful death and survival actions, and that the statute of limitations begins to run when the plaintiff knows or should have known that the death was “wrongfully caused.” However, this did not necessarily mean knowledge of a specific defendant’s negligent conduct or knowledge of the existence of a cause of action.

The court stated: “Plaintiff filed his complaint long after he became possessed with sufficient information, which put him on inquiry to determine whether actionable conduct was involved.” The court ruled that the relevant inquiry was not when the plaintiff became aware that Dr. Rhode may have committed medical negligence, but when any defendant may have committed medical negligence against the patient Kathryn. The case is currently on appeal to the Supreme Court of Illinois.

In addition to the discovery rule, other situations may toll the limitations period. One example is fraudulent concealment of a right of action, where the statute may be tolled during the period of concealment. And in all jurisdictions, the running of the time period is halted in malpractice complaints involving treatment of a minor until that minor reaches a certain age, such as age of majority, or after a stipulated number of years, for example, 6 years.

Occasionally, a health care provider may overlook an important tolling provision. California, for example, has a rule that any “payment” made to an injured party must be accompanied by a written statement regarding the applicable statute of limitations.

In the recent Coastal Surgical Institute v. Blevins case,7 the defendant surgeon made a payment of $4,118.23 for medical expenses incurred by an unrepresented plaintiff, but had neglected to attach a release or a written notice regarding the statute of limitations. The plaintiff subsequently decided to file a lawsuit, even though more than a year – the statutory period – had lapsed.

Under the facts, the limitation period was tolled, and the trial court allowed the case to go forward, ultimately finding liability and awarding damages of $500,000, later reduced to $285,114. The court of appeals affirmed the decision.

This case has prompted MIEC, a malpractice insurance carrier, to emphasize putting in writing the restrictions imposed by the limitations statute to any unrepresented patient. MIEC also warned that the term “payment” might be construed liberally, citing case examples that include a free counseling session and the provision of specialized care for a student injured by a school’s gym equipment.

References

1. Kaplan v. Mamelak, 162 Cal. App. 4th 637 (2008).

2. Yoshizaki v. Hilo Hospital, 433 P.2d 220 (1967).

3. Jacoby v. Kaiser Foundation Hospital, 622 P.2d 613 (1981).

4. Yamaguchi v. Queen’s Medical Center, 648 P.2d 689 (1982).

5. Buck v. Miles, 971 P.2d 717 (1999).

6. Moon v. Rhode, IL. 2015 App. 3d 130613.

7. Coastal Surgical Institute v. Blevins, 232 Cal. App. 4th 1321 (2015).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. It is adapted from the author’s book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk” (2006). For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: In July 2002, a patient in California underwent surgery for a herniated T8-9 disk, but the surgeon instead removed the T6-7 and T7-8 disks. On Sept. 11, 2002, the surgeon discussed with the patient the MRI findings showing his mistake. On Sept. 17, 2003, the patient filed a malpractice lawsuit, just 6 days beyond California’s 1-year limitations period. California subscribes to the discovery rule, that is, a cause of action accrues only when a claimant discovers or should have discovered injury was the result of negligence.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. The lawsuit filed Sept. 17, 2003, is time barred, as the negligent surgery took place in July 2002.

B. On its face, the lawsuit was filed too late, being 1 year and 6 days after the Sept. 11, 2002, discussion date.

C. The lawsuit was timely filed, so long as the claimant can prove he was out of town for more than 6 days of that year.

D. The patient should sue as an action in battery, which has a longer statute of limitations.

E. All choices except A are correct.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although an equitable doctrine of laches existed to foreclose an action that had long lapsed. Statutory changes in the law now require that lawsuits be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable.

Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, that is, relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. This time period, during which a lawsuit must be filed or it will be barred, is termed the statute of limitations. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, with states such as California and Tennessee placing a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims. In California, the running of the statute is tolled (temporarily halted) for the days a claimant is out of state.

The above case scenario is taken from Kaplan v. Mamelak,1 where the plaintiff’s lawsuit was not barred to allow him to identify the number of days he was out of town. The court also permitted a cause of action in battery, which is covered under a longer statute of limitations, as well as one sounding in malpractice.

Patients who are injured from malpractice may not always be aware that a negligent act had taken place, and some injuries may remain latent for a long period. Recognizing this, statutes of limitation emphasize the date when the plaintiff first discovered that the injury resulted from negligence. This is termed the discovery rule.

Stated more formally, the limitations period commences at the time the cause of action (negligence or other wrongs) accrues, and this usually means when the claimant knew (actual knowledge) or should have known (constructive knowledge).

The rule, in the words of one court, is meant to balance the need for “prompt assertion of claims” against a policy “favoring adjudication of claims on the merits and ensuring that a party with a valid claim will be given an opportunity to present it.”

As is typical of other jurisdictions, Hawaii sought to clarify the discovery rule in a series of court cases, beginning with Yoshizaki v. Hilo Hospital,2 where the court deemed a cause of action “does not begin to run until the plaintiff knew or should have known of the defendant’s negligence.”

Subsequently, Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals explained that the state’s 2-year limitations statute commences when the plaintiff discovers, or through the use of reasonable diligence should have discovered, 1) the damage; 2) the violation of the duty; and 3) the causal connection between the violation of the duty and the damage.3

The court subsequently held that the rule prevents the running of the limitations period until “the plaintiff [has] knowledge of those facts which are necessary for an actionable claim.”4 In 1999, the Hawaii Supreme Court clarified that it was “factual knowledge,” rather than “legal knowledge,” that starts the clock running, and that legal knowledge of a defendant’s negligence was not required.5

More recently, litigation over the time barring of claims was evident in Moon v. Rhode,6 where Dr. Clarissa Rhode and Central Illinois Radiological Associates were sued for negligently misreading a patient’s CT scans.

The 90-year-old patient, Kathryn Moon, was admitted to Proctor Hospital May 18, 2009, and died 11 days later following surgery and complications of fluid overload and a pneumoperitoneum. Dr. Rhode, a radiologist, interpreted two CT scans, which an independent expert in 2013 determined were negligently misread. A lawsuit was then brought against Dr. Rhode, who was not a named defendant when the plaintiff had timely filed a medical negligence action back in 2011 against the surgeon and the attending doctor.

The court of appeals held that the discovery rule can be applied to wrongful death and survival actions, and that the statute of limitations begins to run when the plaintiff knows or should have known that the death was “wrongfully caused.” However, this did not necessarily mean knowledge of a specific defendant’s negligent conduct or knowledge of the existence of a cause of action.

The court stated: “Plaintiff filed his complaint long after he became possessed with sufficient information, which put him on inquiry to determine whether actionable conduct was involved.” The court ruled that the relevant inquiry was not when the plaintiff became aware that Dr. Rhode may have committed medical negligence, but when any defendant may have committed medical negligence against the patient Kathryn. The case is currently on appeal to the Supreme Court of Illinois.

In addition to the discovery rule, other situations may toll the limitations period. One example is fraudulent concealment of a right of action, where the statute may be tolled during the period of concealment. And in all jurisdictions, the running of the time period is halted in malpractice complaints involving treatment of a minor until that minor reaches a certain age, such as age of majority, or after a stipulated number of years, for example, 6 years.

Occasionally, a health care provider may overlook an important tolling provision. California, for example, has a rule that any “payment” made to an injured party must be accompanied by a written statement regarding the applicable statute of limitations.

In the recent Coastal Surgical Institute v. Blevins case,7 the defendant surgeon made a payment of $4,118.23 for medical expenses incurred by an unrepresented plaintiff, but had neglected to attach a release or a written notice regarding the statute of limitations. The plaintiff subsequently decided to file a lawsuit, even though more than a year – the statutory period – had lapsed.

Under the facts, the limitation period was tolled, and the trial court allowed the case to go forward, ultimately finding liability and awarding damages of $500,000, later reduced to $285,114. The court of appeals affirmed the decision.

This case has prompted MIEC, a malpractice insurance carrier, to emphasize putting in writing the restrictions imposed by the limitations statute to any unrepresented patient. MIEC also warned that the term “payment” might be construed liberally, citing case examples that include a free counseling session and the provision of specialized care for a student injured by a school’s gym equipment.

References

1. Kaplan v. Mamelak, 162 Cal. App. 4th 637 (2008).

2. Yoshizaki v. Hilo Hospital, 433 P.2d 220 (1967).

3. Jacoby v. Kaiser Foundation Hospital, 622 P.2d 613 (1981).

4. Yamaguchi v. Queen’s Medical Center, 648 P.2d 689 (1982).

5. Buck v. Miles, 971 P.2d 717 (1999).

6. Moon v. Rhode, IL. 2015 App. 3d 130613.

7. Coastal Surgical Institute v. Blevins, 232 Cal. App. 4th 1321 (2015).

Dr. Tan is emeritus professor of medicine and a former adjunct professor of law at the University of Hawaii. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute medical, ethical, or legal advice. It is adapted from the author’s book, “Medical Malpractice: Understanding the Law, Managing the Risk” (2006). For additional information, readers may contact the author at [email protected].

Question: In July 2002, a patient in California underwent surgery for a herniated T8-9 disk, but the surgeon instead removed the T6-7 and T7-8 disks. On Sept. 11, 2002, the surgeon discussed with the patient the MRI findings showing his mistake. On Sept. 17, 2003, the patient filed a malpractice lawsuit, just 6 days beyond California’s 1-year limitations period. California subscribes to the discovery rule, that is, a cause of action accrues only when a claimant discovers or should have discovered injury was the result of negligence.

Which of the following choices is best?

A. The lawsuit filed Sept. 17, 2003, is time barred, as the negligent surgery took place in July 2002.

B. On its face, the lawsuit was filed too late, being 1 year and 6 days after the Sept. 11, 2002, discussion date.

C. The lawsuit was timely filed, so long as the claimant can prove he was out of town for more than 6 days of that year.

D. The patient should sue as an action in battery, which has a longer statute of limitations.

E. All choices except A are correct.

Answer: E. At common law, there was no time limit that barred a plaintiff from bringing a claim, although an equitable doctrine of laches existed to foreclose an action that had long lapsed. Statutory changes in the law now require that lawsuits be brought in a timely manner so that the evidence remains fresh, accurate, and reliable.

Another reason is to provide repose to the wrongdoer, that is, relief from worrying for an indefinite period of time whether a lawsuit will be brought. This time period, during which a lawsuit must be filed or it will be barred, is termed the statute of limitations. It is 2 years for the tort of negligence in most jurisdictions, with states such as California and Tennessee placing a 1-year limit on medical malpractice claims. In California, the running of the statute is tolled (temporarily halted) for the days a claimant is out of state.

The above case scenario is taken from Kaplan v. Mamelak,1 where the plaintiff’s lawsuit was not barred to allow him to identify the number of days he was out of town. The court also permitted a cause of action in battery, which is covered under a longer statute of limitations, as well as one sounding in malpractice.

Patients who are injured from malpractice may not always be aware that a negligent act had taken place, and some injuries may remain latent for a long period. Recognizing this, statutes of limitation emphasize the date when the plaintiff first discovered that the injury resulted from negligence. This is termed the discovery rule.

Stated more formally, the limitations period commences at the time the cause of action (negligence or other wrongs) accrues, and this usually means when the claimant knew (actual knowledge) or should have known (constructive knowledge).

The rule, in the words of one court, is meant to balance the need for “prompt assertion of claims” against a policy “favoring adjudication of claims on the merits and ensuring that a party with a valid claim will be given an opportunity to present it.”

As is typical of other jurisdictions, Hawaii sought to clarify the discovery rule in a series of court cases, beginning with Yoshizaki v. Hilo Hospital,2 where the court deemed a cause of action “does not begin to run until the plaintiff knew or should have known of the defendant’s negligence.”

Subsequently, Hawaii’s Intermediate Court of Appeals explained that the state’s 2-year limitations statute commences when the plaintiff discovers, or through the use of reasonable diligence should have discovered, 1) the damage; 2) the violation of the duty; and 3) the causal connection between the violation of the duty and the damage.3

The court subsequently held that the rule prevents the running of the limitations period until “the plaintiff [has] knowledge of those facts which are necessary for an actionable claim.”4 In 1999, the Hawaii Supreme Court clarified that it was “factual knowledge,” rather than “legal knowledge,” that starts the clock running, and that legal knowledge of a defendant’s negligence was not required.5

More recently, litigation over the time barring of claims was evident in Moon v. Rhode,6 where Dr. Clarissa Rhode and Central Illinois Radiological Associates were sued for negligently misreading a patient’s CT scans.

The 90-year-old patient, Kathryn Moon, was admitted to Proctor Hospital May 18, 2009, and died 11 days later following surgery and complications of fluid overload and a pneumoperitoneum. Dr. Rhode, a radiologist, interpreted two CT scans, which an independent expert in 2013 determined were negligently misread. A lawsuit was then brought against Dr. Rhode, who was not a named defendant when the plaintiff had timely filed a medical negligence action back in 2011 against the surgeon and the attending doctor.

The court of appeals held that the discovery rule can be applied to wrongful death and survival actions, and that the statute of limitations begins to run when the plaintiff knows or should have known that the death was “wrongfully caused.” However, this did not necessarily mean knowledge of a specific defendant’s negligent conduct or knowledge of the existence of a cause of action.

The court stated: “Plaintiff filed his complaint long after he became possessed with sufficient information, which put him on inquiry to determine whether actionable conduct was involved.” The court ruled that the relevant inquiry was not when the plaintiff became aware that Dr. Rhode may have committed medical negligence, but when any defendant may have committed medical negligence against the patient Kathryn. The case is currently on appeal to the Supreme Court of Illinois.

In addition to the discovery rule, other situations may toll the limitations period. One example is fraudulent concealment of a right of action, where the statute may be tolled during the period of concealment. And in all jurisdictions, the running of the time period is halted in malpractice complaints involving treatment of a minor until that minor reaches a certain age, such as age of majority, or after a stipulated number of years, for example, 6 years.

Occasionally, a health care provider may overlook an important tolling provision. California, for example, has a rule that any “payment” made to an injured party must be accompanied by a written statement regarding the applicable statute of limitations.

In the recent Coastal Surgical Institute v. Blevins case,7 the defendant surgeon made a payment of $4,118.23 for medical expenses incurred by an unrepresented plaintiff, but had neglected to attach a release or a written notice regarding the statute of limitations. The plaintiff subsequently decided to file a lawsuit, even though more than a year – the statutory period – had lapsed.

Under the facts, the limitation period was tolled, and the trial court allowed the case to go forward, ultimately finding liability and awarding damages of $500,000, later reduced to $285,114. The court of appeals affirmed the decision.