User login

Study implicates circular RNAs in leukemia, other cancers

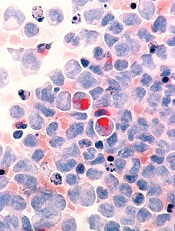

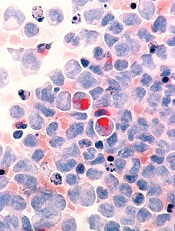

Image courtesy of The Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology

A class of circular RNAs may play a key role in the development and progression of certain leukemias and other cancers, according to research published in Cell.

Investigators found that cancer-associated chromosomal translocations give rise to fusion circular RNAs (f-circRNAs).

And these f-circRNAs aid cellular transformation, promote cell viability, confer treatment resistance, and exhibit tumor-promoting properties in vivo.

“Cancer is essentially a disease of mutated or broken genes, so that motivated us to examine whether circular RNAs, like proteins, can be affected by these chromosomal breaks,” said study author Pier Paolo Pandolfi, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our work paves the way to discovering many more of these unusual RNAs and how they contribute to cancer, which could reveal new mechanisms and druggable pathways involved in tumor progression.”

Curious about the possibility of circular RNAs contributing to cancer, Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues set out to see if they could detect relevant changes in tumors known to harbor distinct fusion proteins.

The team examined acute promyelocytic leukemia, which often carries a translocation between the PML and RARα genes, and acute myeloid leukemia, which can harbor a translocation between the MLL and AF9 genes.

The investigators found f-circRNAs corresponding to different exons associated with the PML-RARα gene fusion and the MLL-AF9 gene fusion. Normally, multiple circular RNAs can be generated from a single gene, so the team was not surprised to find different f-circRNAs emerging from the same fusion gene.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also uncovered f-circRNAs in solid tumors—in Ewing sarcoma and lung cancer.

The team identified the f-circRNAs using 2 distinct methods—PCR-based amplification and sequencing-based approaches. They said this suggests f-circRNAs are bona fide biological entities, rather than experimental artifacts.

“Our ability to readily detect these fusion-circular RNAs—and their normal, non-fused counterparts—will be enhanced by advances in sequencing technology and analytic methods,” said study author Jlenia Guarnerio, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

“Indeed, as we look ahead to cataloguing them comprehensively across all cancers and to deeply understanding their mechanisms of action, we will need to propel these new methodologies even further.”

To determine whether f-circRNAs play a functional role in cancer, the investigators introduced the RNAs into cells. This caused the cells to increase their proliferation and tendency to overgrow—features shared by tumor cells.

On the other hand, when the team blocked f-circRNA activity, the cells’ normal behaviors were restored.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also conducted experiments using a mouse model of leukemia. They focused on a specific f-circRNA associated with the MLL-AF9 fusion gene, called f-circM9.

Although f-circM9 could not trigger leukemia on its own, it appeared to work with other cancer-promoting signals—such as the MLL-AF9 fusion protein—to cause leukemia.

Additional experiments suggested that f-circM9 may also help tumor cells persist despite treatment with anticancer drugs.

“These results are particularly exciting because they suggest that drugs directed at fusion-circular RNAs could be a powerful strategy to pursue for future therapeutic development in cancer,” Dr Pandolfi said.

“[However,] our knowledge of circular RNAs is really in its infancy. We know that, normally, they can bind proteins as well as DNA and microRNAs, but much more needs to be done to understand how fusion-circular RNAs work. We have only scratched the surface of these RNAs and their roles in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

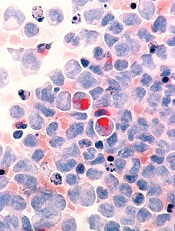

Image courtesy of The Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology

A class of circular RNAs may play a key role in the development and progression of certain leukemias and other cancers, according to research published in Cell.

Investigators found that cancer-associated chromosomal translocations give rise to fusion circular RNAs (f-circRNAs).

And these f-circRNAs aid cellular transformation, promote cell viability, confer treatment resistance, and exhibit tumor-promoting properties in vivo.

“Cancer is essentially a disease of mutated or broken genes, so that motivated us to examine whether circular RNAs, like proteins, can be affected by these chromosomal breaks,” said study author Pier Paolo Pandolfi, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our work paves the way to discovering many more of these unusual RNAs and how they contribute to cancer, which could reveal new mechanisms and druggable pathways involved in tumor progression.”

Curious about the possibility of circular RNAs contributing to cancer, Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues set out to see if they could detect relevant changes in tumors known to harbor distinct fusion proteins.

The team examined acute promyelocytic leukemia, which often carries a translocation between the PML and RARα genes, and acute myeloid leukemia, which can harbor a translocation between the MLL and AF9 genes.

The investigators found f-circRNAs corresponding to different exons associated with the PML-RARα gene fusion and the MLL-AF9 gene fusion. Normally, multiple circular RNAs can be generated from a single gene, so the team was not surprised to find different f-circRNAs emerging from the same fusion gene.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also uncovered f-circRNAs in solid tumors—in Ewing sarcoma and lung cancer.

The team identified the f-circRNAs using 2 distinct methods—PCR-based amplification and sequencing-based approaches. They said this suggests f-circRNAs are bona fide biological entities, rather than experimental artifacts.

“Our ability to readily detect these fusion-circular RNAs—and their normal, non-fused counterparts—will be enhanced by advances in sequencing technology and analytic methods,” said study author Jlenia Guarnerio, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

“Indeed, as we look ahead to cataloguing them comprehensively across all cancers and to deeply understanding their mechanisms of action, we will need to propel these new methodologies even further.”

To determine whether f-circRNAs play a functional role in cancer, the investigators introduced the RNAs into cells. This caused the cells to increase their proliferation and tendency to overgrow—features shared by tumor cells.

On the other hand, when the team blocked f-circRNA activity, the cells’ normal behaviors were restored.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also conducted experiments using a mouse model of leukemia. They focused on a specific f-circRNA associated with the MLL-AF9 fusion gene, called f-circM9.

Although f-circM9 could not trigger leukemia on its own, it appeared to work with other cancer-promoting signals—such as the MLL-AF9 fusion protein—to cause leukemia.

Additional experiments suggested that f-circM9 may also help tumor cells persist despite treatment with anticancer drugs.

“These results are particularly exciting because they suggest that drugs directed at fusion-circular RNAs could be a powerful strategy to pursue for future therapeutic development in cancer,” Dr Pandolfi said.

“[However,] our knowledge of circular RNAs is really in its infancy. We know that, normally, they can bind proteins as well as DNA and microRNAs, but much more needs to be done to understand how fusion-circular RNAs work. We have only scratched the surface of these RNAs and their roles in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

Image courtesy of The Armed

Forces Institute of Pathology

A class of circular RNAs may play a key role in the development and progression of certain leukemias and other cancers, according to research published in Cell.

Investigators found that cancer-associated chromosomal translocations give rise to fusion circular RNAs (f-circRNAs).

And these f-circRNAs aid cellular transformation, promote cell viability, confer treatment resistance, and exhibit tumor-promoting properties in vivo.

“Cancer is essentially a disease of mutated or broken genes, so that motivated us to examine whether circular RNAs, like proteins, can be affected by these chromosomal breaks,” said study author Pier Paolo Pandolfi, MD, PhD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts.

“Our work paves the way to discovering many more of these unusual RNAs and how they contribute to cancer, which could reveal new mechanisms and druggable pathways involved in tumor progression.”

Curious about the possibility of circular RNAs contributing to cancer, Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues set out to see if they could detect relevant changes in tumors known to harbor distinct fusion proteins.

The team examined acute promyelocytic leukemia, which often carries a translocation between the PML and RARα genes, and acute myeloid leukemia, which can harbor a translocation between the MLL and AF9 genes.

The investigators found f-circRNAs corresponding to different exons associated with the PML-RARα gene fusion and the MLL-AF9 gene fusion. Normally, multiple circular RNAs can be generated from a single gene, so the team was not surprised to find different f-circRNAs emerging from the same fusion gene.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also uncovered f-circRNAs in solid tumors—in Ewing sarcoma and lung cancer.

The team identified the f-circRNAs using 2 distinct methods—PCR-based amplification and sequencing-based approaches. They said this suggests f-circRNAs are bona fide biological entities, rather than experimental artifacts.

“Our ability to readily detect these fusion-circular RNAs—and their normal, non-fused counterparts—will be enhanced by advances in sequencing technology and analytic methods,” said study author Jlenia Guarnerio, PhD, also of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

“Indeed, as we look ahead to cataloguing them comprehensively across all cancers and to deeply understanding their mechanisms of action, we will need to propel these new methodologies even further.”

To determine whether f-circRNAs play a functional role in cancer, the investigators introduced the RNAs into cells. This caused the cells to increase their proliferation and tendency to overgrow—features shared by tumor cells.

On the other hand, when the team blocked f-circRNA activity, the cells’ normal behaviors were restored.

Dr Pandolfi and his colleagues also conducted experiments using a mouse model of leukemia. They focused on a specific f-circRNA associated with the MLL-AF9 fusion gene, called f-circM9.

Although f-circM9 could not trigger leukemia on its own, it appeared to work with other cancer-promoting signals—such as the MLL-AF9 fusion protein—to cause leukemia.

Additional experiments suggested that f-circM9 may also help tumor cells persist despite treatment with anticancer drugs.

“These results are particularly exciting because they suggest that drugs directed at fusion-circular RNAs could be a powerful strategy to pursue for future therapeutic development in cancer,” Dr Pandolfi said.

“[However,] our knowledge of circular RNAs is really in its infancy. We know that, normally, they can bind proteins as well as DNA and microRNAs, but much more needs to be done to understand how fusion-circular RNAs work. We have only scratched the surface of these RNAs and their roles in cancer and other diseases.” ![]()

FDA grants product orphan designation for AML

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for the radioimmunoconjugate Iomab-B to be used as a conditioning agent for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Iomab-B is a radioimmunoconjugate consisting of BC8, a novel murine monoclonal antibody, and the radioisotope iodine-131.

BC8 targets CD45, a pan-leukocytic antigen widely expressed on white blood cells. This makes BC8 potentially useful in targeting white blood cells in preparation for HSCT.

When labeled with radioactive isotopes, BC8 carries radioactivity directly to the site of cancerous growth and bone marrow, while avoiding the effects of radiation on most healthy tissues, according to Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing Iomab-B.

Actinium said Iomab-B has been tested as a myeloconditioning/myeloablative agent in more than 250 patients with incurable hematologic malignancies.

The company has released data from a phase 1/2 trial of Iomab-B in patients with relapsed/refractory AML who are older than 50.

The data show that patients who received Iomab-B before HSCT (n=27) had higher rates of survival at 1 and 2 years than patients who underwent HSCT with conventional myeloablative conditioning (n=10) or chemotherapy (n=61).

One-year survival rates were 30% in the Iomab-B arm and 10% each in the conventional conditioning and chemotherapy arms. Two-year survival rates were 19%, 0%, and 0%, respectively.

Now, Actinium is planning a phase 3 trial of Iomab-B in relapsed/refractory AML patients over the age of 55.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

The designation provides the drug’s sponsor with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US market exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for the radioimmunoconjugate Iomab-B to be used as a conditioning agent for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Iomab-B is a radioimmunoconjugate consisting of BC8, a novel murine monoclonal antibody, and the radioisotope iodine-131.

BC8 targets CD45, a pan-leukocytic antigen widely expressed on white blood cells. This makes BC8 potentially useful in targeting white blood cells in preparation for HSCT.

When labeled with radioactive isotopes, BC8 carries radioactivity directly to the site of cancerous growth and bone marrow, while avoiding the effects of radiation on most healthy tissues, according to Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing Iomab-B.

Actinium said Iomab-B has been tested as a myeloconditioning/myeloablative agent in more than 250 patients with incurable hematologic malignancies.

The company has released data from a phase 1/2 trial of Iomab-B in patients with relapsed/refractory AML who are older than 50.

The data show that patients who received Iomab-B before HSCT (n=27) had higher rates of survival at 1 and 2 years than patients who underwent HSCT with conventional myeloablative conditioning (n=10) or chemotherapy (n=61).

One-year survival rates were 30% in the Iomab-B arm and 10% each in the conventional conditioning and chemotherapy arms. Two-year survival rates were 19%, 0%, and 0%, respectively.

Now, Actinium is planning a phase 3 trial of Iomab-B in relapsed/refractory AML patients over the age of 55.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

The designation provides the drug’s sponsor with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US market exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for the radioimmunoconjugate Iomab-B to be used as a conditioning agent for patients with relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who are undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Iomab-B is a radioimmunoconjugate consisting of BC8, a novel murine monoclonal antibody, and the radioisotope iodine-131.

BC8 targets CD45, a pan-leukocytic antigen widely expressed on white blood cells. This makes BC8 potentially useful in targeting white blood cells in preparation for HSCT.

When labeled with radioactive isotopes, BC8 carries radioactivity directly to the site of cancerous growth and bone marrow, while avoiding the effects of radiation on most healthy tissues, according to Actinium Pharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing Iomab-B.

Actinium said Iomab-B has been tested as a myeloconditioning/myeloablative agent in more than 250 patients with incurable hematologic malignancies.

The company has released data from a phase 1/2 trial of Iomab-B in patients with relapsed/refractory AML who are older than 50.

The data show that patients who received Iomab-B before HSCT (n=27) had higher rates of survival at 1 and 2 years than patients who underwent HSCT with conventional myeloablative conditioning (n=10) or chemotherapy (n=61).

One-year survival rates were 30% in the Iomab-B arm and 10% each in the conventional conditioning and chemotherapy arms. Two-year survival rates were 19%, 0%, and 0%, respectively.

Now, Actinium is planning a phase 3 trial of Iomab-B in relapsed/refractory AML patients over the age of 55.

About orphan designation

The FDA grants orphan designation to drugs intended to treat diseases or conditions affecting fewer than 200,000 patients in the US.

The designation provides the drug’s sponsor with various development incentives, including opportunities to apply for research-related tax credits and grant funding, assistance in designing clinical trials, and 7 years of US market exclusivity if the drug is approved. ![]()

Drug bests placebo in iron deficiency anemia trial

Top-line results from a phase 3 trial suggest the oral, iron-based drug ferric citrate is more effective than placebo for treating iron deficiency anemia in adults with stage 3-5, non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received ferric citrate achieved at least a 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin over a 16-week period, compared to 19% of patients who received placebo.

Researchers said the safety profile of ferric citrate in this trial was consistent with that in previous studies.

Keryx Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ferric citrate, recently announced these results.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 study, researchers compared treatment with ferric citrate to placebo in 234 patients who previously had not adequately responded to or tolerated current oral iron therapies. The patients were not allowed to receive any iron (intravenous or oral) or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents during this study.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive ferric citrate (n=117) or placebo (n=115). Two patients in the placebo arm discontinued the study and were not included in the efficacy analysis. One discontinued after randomization prior to receiving placebo, and the other discontinued after taking a dose of placebo but before having laboratory values drawn.

The study had a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy period, followed by an 8-week, open-label safety extension period. During the extension period, all patients remaining in the study, including the placebo arm, received ferric citrate.

During the efficacy period, ferric citrate was administered at a starting dose of 3 tablets per day, with food, and could be titrated every 4 weeks by an additional 3 tablets, for up to 12 tablets per day. The mean dose of ferric citrate was 5 tablets per day.

Baseline laboratory values were similar between the treatment arms. The mean hemoglobin was 10.4 g/dL in both arms.

The mean transferrin saturation was 20.2% in the ferric citrate arm and 19.6% in the placebo arm. The mean ferritin was 85.9 ng/mL and 81.7 ng/mL, respectively. And the mean serum phosphate was 4.2 mg/dL and 4.1 mg/dL, respectively.

Efficacy results

The study achieved its primary endpoint, with 52.1% (61/117) of patients who received ferric citrate achieving a 1g/dL or greater rise in hemoglobin at any time point during the 16-week efficacy period, compared to 19.1% (22/115) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The researchers also observed significant differences in all pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoints.

The mean change in hemoglobin was 0.75 g/dL in the ferric citrate arm and -0.08 g/dL in the placebo arm (P<0.001). The mean change in transferrin saturation was 17.8% and -0.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The mean change in ferritin was 162.5 ng/mL and -7.7 ng/mL, respectively (P<0.001). And the mean change in serum phosphate was -0.43 mg/dL and -0.22 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.02).

The proportion of patients with a durable response during the efficacy period was 48.7% in the ferric citrate arm and 14.8% in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

A durable response was defined as a mean change in hemoglobin from baseline of at least 0.75 g/dL over any 4-week time period during the efficacy period, provided that an increase of at least 1.0 g/dL had occurred during that 4-week period.

Safety results

During the efficacy period, the majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate. The most common AEs—in the ferric citrate and placebo arms, respectively—were diarrhea (20.5% vs 16.4%), constipation (18.8% vs 12.9%), discolored feces (14.5% vs 0%), and nausea (11.1% vs 2.6%).

Hypophosphatemia was reported in 4 patients—1 in the ferric citrate arm and 3 in the placebo arm.

Twenty-six percent (31/117) of ferric citrate-treated patients and 30% (35/116) of patients receiving placebo discontinued treatment during the efficacy period. Twelve patients treated with ferric citrate discontinued due to an AE, as did 10 patients who received placebo.

During the efficacy period, the rate of serious AEs was balanced between the ferric citrate and placebo arms, at 12% and 10%, respectively. None of the serious AEs were deemed drug-related.

Over the course of the study, there were 2 deaths reported. Both occurred in patients receiving ferric citrate, but neither were considered drug-related. ![]()

Top-line results from a phase 3 trial suggest the oral, iron-based drug ferric citrate is more effective than placebo for treating iron deficiency anemia in adults with stage 3-5, non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received ferric citrate achieved at least a 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin over a 16-week period, compared to 19% of patients who received placebo.

Researchers said the safety profile of ferric citrate in this trial was consistent with that in previous studies.

Keryx Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ferric citrate, recently announced these results.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 study, researchers compared treatment with ferric citrate to placebo in 234 patients who previously had not adequately responded to or tolerated current oral iron therapies. The patients were not allowed to receive any iron (intravenous or oral) or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents during this study.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive ferric citrate (n=117) or placebo (n=115). Two patients in the placebo arm discontinued the study and were not included in the efficacy analysis. One discontinued after randomization prior to receiving placebo, and the other discontinued after taking a dose of placebo but before having laboratory values drawn.

The study had a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy period, followed by an 8-week, open-label safety extension period. During the extension period, all patients remaining in the study, including the placebo arm, received ferric citrate.

During the efficacy period, ferric citrate was administered at a starting dose of 3 tablets per day, with food, and could be titrated every 4 weeks by an additional 3 tablets, for up to 12 tablets per day. The mean dose of ferric citrate was 5 tablets per day.

Baseline laboratory values were similar between the treatment arms. The mean hemoglobin was 10.4 g/dL in both arms.

The mean transferrin saturation was 20.2% in the ferric citrate arm and 19.6% in the placebo arm. The mean ferritin was 85.9 ng/mL and 81.7 ng/mL, respectively. And the mean serum phosphate was 4.2 mg/dL and 4.1 mg/dL, respectively.

Efficacy results

The study achieved its primary endpoint, with 52.1% (61/117) of patients who received ferric citrate achieving a 1g/dL or greater rise in hemoglobin at any time point during the 16-week efficacy period, compared to 19.1% (22/115) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The researchers also observed significant differences in all pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoints.

The mean change in hemoglobin was 0.75 g/dL in the ferric citrate arm and -0.08 g/dL in the placebo arm (P<0.001). The mean change in transferrin saturation was 17.8% and -0.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The mean change in ferritin was 162.5 ng/mL and -7.7 ng/mL, respectively (P<0.001). And the mean change in serum phosphate was -0.43 mg/dL and -0.22 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.02).

The proportion of patients with a durable response during the efficacy period was 48.7% in the ferric citrate arm and 14.8% in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

A durable response was defined as a mean change in hemoglobin from baseline of at least 0.75 g/dL over any 4-week time period during the efficacy period, provided that an increase of at least 1.0 g/dL had occurred during that 4-week period.

Safety results

During the efficacy period, the majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate. The most common AEs—in the ferric citrate and placebo arms, respectively—were diarrhea (20.5% vs 16.4%), constipation (18.8% vs 12.9%), discolored feces (14.5% vs 0%), and nausea (11.1% vs 2.6%).

Hypophosphatemia was reported in 4 patients—1 in the ferric citrate arm and 3 in the placebo arm.

Twenty-six percent (31/117) of ferric citrate-treated patients and 30% (35/116) of patients receiving placebo discontinued treatment during the efficacy period. Twelve patients treated with ferric citrate discontinued due to an AE, as did 10 patients who received placebo.

During the efficacy period, the rate of serious AEs was balanced between the ferric citrate and placebo arms, at 12% and 10%, respectively. None of the serious AEs were deemed drug-related.

Over the course of the study, there were 2 deaths reported. Both occurred in patients receiving ferric citrate, but neither were considered drug-related. ![]()

Top-line results from a phase 3 trial suggest the oral, iron-based drug ferric citrate is more effective than placebo for treating iron deficiency anemia in adults with stage 3-5, non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease.

Fifty-two percent of patients who received ferric citrate achieved at least a 1 g/dL increase in hemoglobin over a 16-week period, compared to 19% of patients who received placebo.

Researchers said the safety profile of ferric citrate in this trial was consistent with that in previous studies.

Keryx Biopharmaceuticals, Inc., the company developing ferric citrate, recently announced these results.

Patients and treatment

In this phase 3 study, researchers compared treatment with ferric citrate to placebo in 234 patients who previously had not adequately responded to or tolerated current oral iron therapies. The patients were not allowed to receive any iron (intravenous or oral) or erythropoiesis-stimulating agents during this study.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive ferric citrate (n=117) or placebo (n=115). Two patients in the placebo arm discontinued the study and were not included in the efficacy analysis. One discontinued after randomization prior to receiving placebo, and the other discontinued after taking a dose of placebo but before having laboratory values drawn.

The study had a 16-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy period, followed by an 8-week, open-label safety extension period. During the extension period, all patients remaining in the study, including the placebo arm, received ferric citrate.

During the efficacy period, ferric citrate was administered at a starting dose of 3 tablets per day, with food, and could be titrated every 4 weeks by an additional 3 tablets, for up to 12 tablets per day. The mean dose of ferric citrate was 5 tablets per day.

Baseline laboratory values were similar between the treatment arms. The mean hemoglobin was 10.4 g/dL in both arms.

The mean transferrin saturation was 20.2% in the ferric citrate arm and 19.6% in the placebo arm. The mean ferritin was 85.9 ng/mL and 81.7 ng/mL, respectively. And the mean serum phosphate was 4.2 mg/dL and 4.1 mg/dL, respectively.

Efficacy results

The study achieved its primary endpoint, with 52.1% (61/117) of patients who received ferric citrate achieving a 1g/dL or greater rise in hemoglobin at any time point during the 16-week efficacy period, compared to 19.1% (22/115) of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The researchers also observed significant differences in all pre-specified secondary efficacy endpoints.

The mean change in hemoglobin was 0.75 g/dL in the ferric citrate arm and -0.08 g/dL in the placebo arm (P<0.001). The mean change in transferrin saturation was 17.8% and -0.6%, respectively (P<0.001).

The mean change in ferritin was 162.5 ng/mL and -7.7 ng/mL, respectively (P<0.001). And the mean change in serum phosphate was -0.43 mg/dL and -0.22 mg/dL, respectively (P=0.02).

The proportion of patients with a durable response during the efficacy period was 48.7% in the ferric citrate arm and 14.8% in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

A durable response was defined as a mean change in hemoglobin from baseline of at least 0.75 g/dL over any 4-week time period during the efficacy period, provided that an increase of at least 1.0 g/dL had occurred during that 4-week period.

Safety results

During the efficacy period, the majority of adverse events (AEs) were mild to moderate. The most common AEs—in the ferric citrate and placebo arms, respectively—were diarrhea (20.5% vs 16.4%), constipation (18.8% vs 12.9%), discolored feces (14.5% vs 0%), and nausea (11.1% vs 2.6%).

Hypophosphatemia was reported in 4 patients—1 in the ferric citrate arm and 3 in the placebo arm.

Twenty-six percent (31/117) of ferric citrate-treated patients and 30% (35/116) of patients receiving placebo discontinued treatment during the efficacy period. Twelve patients treated with ferric citrate discontinued due to an AE, as did 10 patients who received placebo.

During the efficacy period, the rate of serious AEs was balanced between the ferric citrate and placebo arms, at 12% and 10%, respectively. None of the serious AEs were deemed drug-related.

Over the course of the study, there were 2 deaths reported. Both occurred in patients receiving ferric citrate, but neither were considered drug-related. ![]()

Pathophysiology of Type 2 Diabetes: The Evolution of Our Understanding

April 2016 Digital Edition

Table of Contents

- Lessons From History: The Ethical Foundation of VA Health Care

- Calcium-Containing Crystal-Associated Arthropathies in the Elderly

- Recurrent Abdominal Pain and Bowel Edema in a Middle-Aged Woman

- Implementing the EQUiPPED Medication Management Program

- Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 1

- An ECHO-Based Program to Provide Geriatric Specialty Care Consultation and Education

- Possible Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir-Induced Hepatic Decompensation With Acute Kidney Failure

Table of Contents

- Lessons From History: The Ethical Foundation of VA Health Care

- Calcium-Containing Crystal-Associated Arthropathies in the Elderly

- Recurrent Abdominal Pain and Bowel Edema in a Middle-Aged Woman

- Implementing the EQUiPPED Medication Management Program

- Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 1

- An ECHO-Based Program to Provide Geriatric Specialty Care Consultation and Education

- Possible Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir-Induced Hepatic Decompensation With Acute Kidney Failure

Table of Contents

- Lessons From History: The Ethical Foundation of VA Health Care

- Calcium-Containing Crystal-Associated Arthropathies in the Elderly

- Recurrent Abdominal Pain and Bowel Edema in a Middle-Aged Woman

- Implementing the EQUiPPED Medication Management Program

- Academic Reasonable Accommodations for Post-9/11 Veterans With Psychiatric Diagnoses, Part 1

- An ECHO-Based Program to Provide Geriatric Specialty Care Consultation and Education

- Possible Simeprevir/Sofosbuvir-Induced Hepatic Decompensation With Acute Kidney Failure

VIDEO: Eight new quality measures key to performance of esophageal manometry

Health care providers performing esophageal manometry should keep in mind eight new quality measures listed and validated in a recent study published in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.006), which researchers believe will significantly improve the performance of esophageal manometry and interpretation of data culled from such procedures.

“Despite its critical importance in the diagnosis and management of esophageal motility disorders, features of a high-quality esophageal manometry [study] have not been formally defined,” said the study authors, led by Dr. Rena Yadlapati of Northwestern University in Chicago. “Standardizing key aspects of esophageal manometry is imperative to ensure the delivery of high-quality care.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Yadlapati and her coinvestigators carried out the study in accordance with guidelines set out by the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM), They began by recruiting a panel of 15 esophageal manometry experts with leadership, geographical diversity, and a wide range of practice settings being the key criteria in their selection.

Investigators then conducted a literature review, selecting the 30 most relevant randomized, controlled trials, retrospective studies, and systematic reviews from the past 10 years. From this review, investigators created a list of 30 possible quality measures, all of which were then sent to each member of the expert panel via email for them to rank on a 9-point interval scale, and modify if necessary.

Those rankings were then used to determine the appropriateness of each proposed quality measure at a face-to-face meeting among the investigators and the 15-member expert panel, at which 17 quality measures were determined to be appropriate. In all, 2 measures dealt with competency, 2 pertained to assessment before procedure, 3 were regarding performance of the procedure itself, and 10 were about interpretation of data obtained from esophageal manometry; the 10 measures concerning interpretation of data were compiled into 1 measure, leaving a total of 8 that were ultimately approved.

The quality measures for competency are as follows:

• “If esophageal manometry is performed, then the technician must be competent to perform esophageal manometry.”

• “If a physician is considered competent to interpret esophageal manometry, then the physician must interpret a minimum number of esophageal manometry studies annually.”

For assessment before procedure, the measures state the following:

• “If a patient is referred for esophageal manometry, then the patient should have undergone an evaluation for structural abnormalities before manometry.”

• “If an esophageal manometry is performed, then informed consent must be obtained and documented.”

Quality measures regarding the procedure itself state the following:

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then a time interval of at least 30 seconds should occur between swallows.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least 10 wet swallows should be attempted.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least seven evaluable wet swallows should be included.”

Finally, regarding interpretation of data, the single quality measures states that “If an esophageal manometry study is interpreted, then a complete procedure report should document the following:

• “Reason for referral.”

• “Clinical diagnosis.”

• “Diagnosis according to formally validated classification scheme.”

• “Documentation of formally validated classification scheme used.”

• “Summary of results”

• “Tabulated results including upper esophageal sphincter activity, interpretation of esophagogastric junction relaxation, documentation of pressure inversion point if technically feasible, pressurization pattern and contractile pattern.”

• “Technical limitation (if applicable).”

• “Communication to referring provider.”

“These eight appropriate quality measures are considered absolutely necessary in the performance and interpretation of esophageal manometry,” the authors concluded. “In particular, measures 3-8 are clinically feasible and measurable, and should serve as an initial framework to benchmark quality and reduce variability in esophageal manometry practices.”

This study was funded by the Alumnae of Northwestern University, and a grant to Dr. Yadlapati (T32 DK101363-02). Five coinvestigators disclosed consultancy and speaking relationships with Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, EndoStim, Given Imaging, Covidien, and Sandhill Scientific.

Health care providers performing esophageal manometry should keep in mind eight new quality measures listed and validated in a recent study published in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.006), which researchers believe will significantly improve the performance of esophageal manometry and interpretation of data culled from such procedures.

“Despite its critical importance in the diagnosis and management of esophageal motility disorders, features of a high-quality esophageal manometry [study] have not been formally defined,” said the study authors, led by Dr. Rena Yadlapati of Northwestern University in Chicago. “Standardizing key aspects of esophageal manometry is imperative to ensure the delivery of high-quality care.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Yadlapati and her coinvestigators carried out the study in accordance with guidelines set out by the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM), They began by recruiting a panel of 15 esophageal manometry experts with leadership, geographical diversity, and a wide range of practice settings being the key criteria in their selection.

Investigators then conducted a literature review, selecting the 30 most relevant randomized, controlled trials, retrospective studies, and systematic reviews from the past 10 years. From this review, investigators created a list of 30 possible quality measures, all of which were then sent to each member of the expert panel via email for them to rank on a 9-point interval scale, and modify if necessary.

Those rankings were then used to determine the appropriateness of each proposed quality measure at a face-to-face meeting among the investigators and the 15-member expert panel, at which 17 quality measures were determined to be appropriate. In all, 2 measures dealt with competency, 2 pertained to assessment before procedure, 3 were regarding performance of the procedure itself, and 10 were about interpretation of data obtained from esophageal manometry; the 10 measures concerning interpretation of data were compiled into 1 measure, leaving a total of 8 that were ultimately approved.

The quality measures for competency are as follows:

• “If esophageal manometry is performed, then the technician must be competent to perform esophageal manometry.”

• “If a physician is considered competent to interpret esophageal manometry, then the physician must interpret a minimum number of esophageal manometry studies annually.”

For assessment before procedure, the measures state the following:

• “If a patient is referred for esophageal manometry, then the patient should have undergone an evaluation for structural abnormalities before manometry.”

• “If an esophageal manometry is performed, then informed consent must be obtained and documented.”

Quality measures regarding the procedure itself state the following:

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then a time interval of at least 30 seconds should occur between swallows.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least 10 wet swallows should be attempted.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least seven evaluable wet swallows should be included.”

Finally, regarding interpretation of data, the single quality measures states that “If an esophageal manometry study is interpreted, then a complete procedure report should document the following:

• “Reason for referral.”

• “Clinical diagnosis.”

• “Diagnosis according to formally validated classification scheme.”

• “Documentation of formally validated classification scheme used.”

• “Summary of results”

• “Tabulated results including upper esophageal sphincter activity, interpretation of esophagogastric junction relaxation, documentation of pressure inversion point if technically feasible, pressurization pattern and contractile pattern.”

• “Technical limitation (if applicable).”

• “Communication to referring provider.”

“These eight appropriate quality measures are considered absolutely necessary in the performance and interpretation of esophageal manometry,” the authors concluded. “In particular, measures 3-8 are clinically feasible and measurable, and should serve as an initial framework to benchmark quality and reduce variability in esophageal manometry practices.”

This study was funded by the Alumnae of Northwestern University, and a grant to Dr. Yadlapati (T32 DK101363-02). Five coinvestigators disclosed consultancy and speaking relationships with Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, EndoStim, Given Imaging, Covidien, and Sandhill Scientific.

Health care providers performing esophageal manometry should keep in mind eight new quality measures listed and validated in a recent study published in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 20. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.006), which researchers believe will significantly improve the performance of esophageal manometry and interpretation of data culled from such procedures.

“Despite its critical importance in the diagnosis and management of esophageal motility disorders, features of a high-quality esophageal manometry [study] have not been formally defined,” said the study authors, led by Dr. Rena Yadlapati of Northwestern University in Chicago. “Standardizing key aspects of esophageal manometry is imperative to ensure the delivery of high-quality care.”

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Yadlapati and her coinvestigators carried out the study in accordance with guidelines set out by the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM), They began by recruiting a panel of 15 esophageal manometry experts with leadership, geographical diversity, and a wide range of practice settings being the key criteria in their selection.

Investigators then conducted a literature review, selecting the 30 most relevant randomized, controlled trials, retrospective studies, and systematic reviews from the past 10 years. From this review, investigators created a list of 30 possible quality measures, all of which were then sent to each member of the expert panel via email for them to rank on a 9-point interval scale, and modify if necessary.

Those rankings were then used to determine the appropriateness of each proposed quality measure at a face-to-face meeting among the investigators and the 15-member expert panel, at which 17 quality measures were determined to be appropriate. In all, 2 measures dealt with competency, 2 pertained to assessment before procedure, 3 were regarding performance of the procedure itself, and 10 were about interpretation of data obtained from esophageal manometry; the 10 measures concerning interpretation of data were compiled into 1 measure, leaving a total of 8 that were ultimately approved.

The quality measures for competency are as follows:

• “If esophageal manometry is performed, then the technician must be competent to perform esophageal manometry.”

• “If a physician is considered competent to interpret esophageal manometry, then the physician must interpret a minimum number of esophageal manometry studies annually.”

For assessment before procedure, the measures state the following:

• “If a patient is referred for esophageal manometry, then the patient should have undergone an evaluation for structural abnormalities before manometry.”

• “If an esophageal manometry is performed, then informed consent must be obtained and documented.”

Quality measures regarding the procedure itself state the following:

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then a time interval of at least 30 seconds should occur between swallows.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least 10 wet swallows should be attempted.”

• “If an esophageal manometry study is performed, then at least seven evaluable wet swallows should be included.”

Finally, regarding interpretation of data, the single quality measures states that “If an esophageal manometry study is interpreted, then a complete procedure report should document the following:

• “Reason for referral.”

• “Clinical diagnosis.”

• “Diagnosis according to formally validated classification scheme.”

• “Documentation of formally validated classification scheme used.”

• “Summary of results”

• “Tabulated results including upper esophageal sphincter activity, interpretation of esophagogastric junction relaxation, documentation of pressure inversion point if technically feasible, pressurization pattern and contractile pattern.”

• “Technical limitation (if applicable).”

• “Communication to referring provider.”

“These eight appropriate quality measures are considered absolutely necessary in the performance and interpretation of esophageal manometry,” the authors concluded. “In particular, measures 3-8 are clinically feasible and measurable, and should serve as an initial framework to benchmark quality and reduce variability in esophageal manometry practices.”

This study was funded by the Alumnae of Northwestern University, and a grant to Dr. Yadlapati (T32 DK101363-02). Five coinvestigators disclosed consultancy and speaking relationships with Boston Scientific, Cook Endoscopy, EndoStim, Given Imaging, Covidien, and Sandhill Scientific.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Health care providers should consider eight new validated quality measures when performing and interpreting esophageal manometry data.

Major finding: Of 30 possible measures, 10 regarding interpretation of data were compiled into a single quality measure, 2 were classified as competency measures, 2 were classified as assessments necessary prior to an esophageal manometry procedure, and 3 were classified as integral to the procedure of esophageal manometry, for a total of 8.

Data source: Survey of existing literature and expert interviews on validated quality measures on the basis of the RAM.

Disclosures: Study was partly funded by a grant from the Alumnae of Northwestern University; five coauthors reported financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Rectal indomethacin does not prevent pancreatitis post ERCP

Patients who receive rectal indomethacin after undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are not any less likely to develop pancreatitis than individuals who don’t, according to the findings of a recent study published in Gastroenterology (2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

“These results are in contrast to recent studies highlighting the benefit of rectal NSAIDS to prevent PEP [post-ECRP pancreatitis] in high-risk patients [and] counter the guidelines espoused by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, which recently recommended giving rectal indomethacin to prevent PEP in all patients undergoing ERCP,” said the study authors, led by Dr. John M. Levenick of Penn State University in Hershey, Pa.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Levenick and his coinvestigators screened 604 consecutive patients undergoing ERCP, with and without endoscopic ultrasound, at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center between March 2013 and December 2014, eventually enrolling and randomizing 449 subjects into two cohorts: one in which subjects were given indomethacin after undergoing ERCP (n = 223), and one in which subjects were simply given a placebo (n = 226). Randomization happened after subjects’ major papilla had been reached, and cannulation attempts were started.

Individuals were excluded if they had active acute pancreatitis or had undergone ERCP to treat or diagnose acute pancreatitis, if they had any contraindications or allergies to NSAIDs, or were younger than 18 years of age, among other factors. The mean age of the indomethacin cohort was 64.9 years, with 118 (52.9%) females; in the placebo cohort, mean age was 64.3 years and 118 (52.2%) were female.

Pancreatitis occurred in 27 subjects overall, 16 (7.2%) of whom were in the indomethacin cohort and the other 11 (4.9%) were on placebo followed ERCP (P = .33). No subjects receiving indomethacin had severe or moderately severe PEP, but one subject had severe PEP and one had moderately severe PEP in the placebo cohort (P = 1.0). There was no necrotizing pancreatitis in either cohort, nor were there any significant differences in gastrointestinal bleeding (P = .75), death (P = .25), or 30-day hospital readmission (P = .1) between the two cohorts.

“Prophylactic rectal indomethacin did not reduce the incidence or severity of PEP in consecutive patients undergoing ERCP,” Dr. Levenick and his coauthors concluded, adding that “guidelines that recommend the administration of rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP should be reconsidered.”

This study was funded by the National Pancreas Foundation and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Levenick and his coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

Acute pancreatitis is the most common and feared complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis is around 10% with a mortality of 0.7% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-9). Recent advances in noninvasive pancreaticobiliary imaging, risk stratification before ERCP, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement, and administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have improved the overall risk benefit ratio of ERCP.

NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and of the activation of platelets and endothelium, all of which play a central role in the pathogenesis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. NSAIDs constitute an attractive option in clinical practice, because they are inexpensive and widely available with a favorable risk profile. A recent multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 602 patients at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis showed that rectal indomethacin is associated with a 7.7% absolute and a 46% relative risk reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-22). These findings have been broadly adapted in endoscopic practice in the United States.

|

| Dr. Georgios Papachristou |

The presented RCT by Dr. Levenick and his colleagues evaluated the efficacy of rectal indomethacin in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis among consecutive patients undergoing ERCP in a single U.S. center. This study was a well designed and conducted RCT following the CONSORT guidelines and utilizing an independent data and safety monitoring board.

The authors reported that rectal indomethacin did not result in reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (7.2%) when compared with placebo (4.9%). Of importance, 70% of patients included were at average risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Furthermore, despite a calculated sample size of 1,398 patients, the study was terminated early after enrolling only 449 patients based on the interim analysis showing futility to reach a statistically different outcome.

This well executed RCT reports no benefit in administering rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP. Evidence strongly supports that rectal indomethacin remains an important advancement in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, its benefit is likely limited to a selected group of patients, those at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Further studies are under way to clarify whether rectal indomethacin alone vs. indomethacin plus prophylactic pancreatic stenting is more effective in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.

Dr. Georgios Papachristou is associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a consultant for Shire and has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the VA Health System.

Acute pancreatitis is the most common and feared complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis is around 10% with a mortality of 0.7% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-9). Recent advances in noninvasive pancreaticobiliary imaging, risk stratification before ERCP, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement, and administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have improved the overall risk benefit ratio of ERCP.

NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and of the activation of platelets and endothelium, all of which play a central role in the pathogenesis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. NSAIDs constitute an attractive option in clinical practice, because they are inexpensive and widely available with a favorable risk profile. A recent multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 602 patients at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis showed that rectal indomethacin is associated with a 7.7% absolute and a 46% relative risk reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-22). These findings have been broadly adapted in endoscopic practice in the United States.

|

| Dr. Georgios Papachristou |

The presented RCT by Dr. Levenick and his colleagues evaluated the efficacy of rectal indomethacin in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis among consecutive patients undergoing ERCP in a single U.S. center. This study was a well designed and conducted RCT following the CONSORT guidelines and utilizing an independent data and safety monitoring board.

The authors reported that rectal indomethacin did not result in reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (7.2%) when compared with placebo (4.9%). Of importance, 70% of patients included were at average risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Furthermore, despite a calculated sample size of 1,398 patients, the study was terminated early after enrolling only 449 patients based on the interim analysis showing futility to reach a statistically different outcome.

This well executed RCT reports no benefit in administering rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP. Evidence strongly supports that rectal indomethacin remains an important advancement in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, its benefit is likely limited to a selected group of patients, those at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Further studies are under way to clarify whether rectal indomethacin alone vs. indomethacin plus prophylactic pancreatic stenting is more effective in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.

Dr. Georgios Papachristou is associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a consultant for Shire and has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the VA Health System.

Acute pancreatitis is the most common and feared complication of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). The incidence of post-ERCP pancreatitis is around 10% with a mortality of 0.7% (Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:143-9). Recent advances in noninvasive pancreaticobiliary imaging, risk stratification before ERCP, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement, and administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have improved the overall risk benefit ratio of ERCP.

NSAIDs are potent inhibitors of phospholipase A2, cyclooxygenase, and of the activation of platelets and endothelium, all of which play a central role in the pathogenesis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. NSAIDs constitute an attractive option in clinical practice, because they are inexpensive and widely available with a favorable risk profile. A recent multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 602 patients at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis showed that rectal indomethacin is associated with a 7.7% absolute and a 46% relative risk reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1414-22). These findings have been broadly adapted in endoscopic practice in the United States.

|

| Dr. Georgios Papachristou |

The presented RCT by Dr. Levenick and his colleagues evaluated the efficacy of rectal indomethacin in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis among consecutive patients undergoing ERCP in a single U.S. center. This study was a well designed and conducted RCT following the CONSORT guidelines and utilizing an independent data and safety monitoring board.

The authors reported that rectal indomethacin did not result in reduction of post-ERCP pancreatitis (7.2%) when compared with placebo (4.9%). Of importance, 70% of patients included were at average risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Furthermore, despite a calculated sample size of 1,398 patients, the study was terminated early after enrolling only 449 patients based on the interim analysis showing futility to reach a statistically different outcome.

This well executed RCT reports no benefit in administering rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP. Evidence strongly supports that rectal indomethacin remains an important advancement in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis. However, its benefit is likely limited to a selected group of patients, those at high-risk for post-ERCP pancreatitis. Further studies are under way to clarify whether rectal indomethacin alone vs. indomethacin plus prophylactic pancreatic stenting is more effective in preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis in high-risk patients.

Dr. Georgios Papachristou is associate professor of medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. He is a consultant for Shire and has received funding from the National Institutes of Health and the VA Health System.

Patients who receive rectal indomethacin after undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are not any less likely to develop pancreatitis than individuals who don’t, according to the findings of a recent study published in Gastroenterology (2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

“These results are in contrast to recent studies highlighting the benefit of rectal NSAIDS to prevent PEP [post-ECRP pancreatitis] in high-risk patients [and] counter the guidelines espoused by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, which recently recommended giving rectal indomethacin to prevent PEP in all patients undergoing ERCP,” said the study authors, led by Dr. John M. Levenick of Penn State University in Hershey, Pa.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Levenick and his coinvestigators screened 604 consecutive patients undergoing ERCP, with and without endoscopic ultrasound, at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center between March 2013 and December 2014, eventually enrolling and randomizing 449 subjects into two cohorts: one in which subjects were given indomethacin after undergoing ERCP (n = 223), and one in which subjects were simply given a placebo (n = 226). Randomization happened after subjects’ major papilla had been reached, and cannulation attempts were started.

Individuals were excluded if they had active acute pancreatitis or had undergone ERCP to treat or diagnose acute pancreatitis, if they had any contraindications or allergies to NSAIDs, or were younger than 18 years of age, among other factors. The mean age of the indomethacin cohort was 64.9 years, with 118 (52.9%) females; in the placebo cohort, mean age was 64.3 years and 118 (52.2%) were female.

Pancreatitis occurred in 27 subjects overall, 16 (7.2%) of whom were in the indomethacin cohort and the other 11 (4.9%) were on placebo followed ERCP (P = .33). No subjects receiving indomethacin had severe or moderately severe PEP, but one subject had severe PEP and one had moderately severe PEP in the placebo cohort (P = 1.0). There was no necrotizing pancreatitis in either cohort, nor were there any significant differences in gastrointestinal bleeding (P = .75), death (P = .25), or 30-day hospital readmission (P = .1) between the two cohorts.

“Prophylactic rectal indomethacin did not reduce the incidence or severity of PEP in consecutive patients undergoing ERCP,” Dr. Levenick and his coauthors concluded, adding that “guidelines that recommend the administration of rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP should be reconsidered.”

This study was funded by the National Pancreas Foundation and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Levenick and his coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

Patients who receive rectal indomethacin after undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) are not any less likely to develop pancreatitis than individuals who don’t, according to the findings of a recent study published in Gastroenterology (2016 Jan 9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.018).

“These results are in contrast to recent studies highlighting the benefit of rectal NSAIDS to prevent PEP [post-ECRP pancreatitis] in high-risk patients [and] counter the guidelines espoused by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, which recently recommended giving rectal indomethacin to prevent PEP in all patients undergoing ERCP,” said the study authors, led by Dr. John M. Levenick of Penn State University in Hershey, Pa.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Dr. Levenick and his coinvestigators screened 604 consecutive patients undergoing ERCP, with and without endoscopic ultrasound, at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center between March 2013 and December 2014, eventually enrolling and randomizing 449 subjects into two cohorts: one in which subjects were given indomethacin after undergoing ERCP (n = 223), and one in which subjects were simply given a placebo (n = 226). Randomization happened after subjects’ major papilla had been reached, and cannulation attempts were started.

Individuals were excluded if they had active acute pancreatitis or had undergone ERCP to treat or diagnose acute pancreatitis, if they had any contraindications or allergies to NSAIDs, or were younger than 18 years of age, among other factors. The mean age of the indomethacin cohort was 64.9 years, with 118 (52.9%) females; in the placebo cohort, mean age was 64.3 years and 118 (52.2%) were female.

Pancreatitis occurred in 27 subjects overall, 16 (7.2%) of whom were in the indomethacin cohort and the other 11 (4.9%) were on placebo followed ERCP (P = .33). No subjects receiving indomethacin had severe or moderately severe PEP, but one subject had severe PEP and one had moderately severe PEP in the placebo cohort (P = 1.0). There was no necrotizing pancreatitis in either cohort, nor were there any significant differences in gastrointestinal bleeding (P = .75), death (P = .25), or 30-day hospital readmission (P = .1) between the two cohorts.

“Prophylactic rectal indomethacin did not reduce the incidence or severity of PEP in consecutive patients undergoing ERCP,” Dr. Levenick and his coauthors concluded, adding that “guidelines that recommend the administration of rectal indomethacin in all patients undergoing ERCP should be reconsidered.”

This study was funded by the National Pancreas Foundation and a grant from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Levenick and his coauthors did not report any financial disclosures.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Rectal indomethacin does not prevent pancreatitis in patients who undergo endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

Major finding: 7.2% of subjects on indomethacin and 4.9% on placebo developed post-ERCP pancreatitis, indicating no significant difference between the two cohorts (P = .33).

Data source: Prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 449 ERCP patients between March 2013 and December 2014.

Disclosures: Study funded by National Pancreas Foundation and National Institutes of Health. Dr. Levenick and his coauthors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: Newer MRI hardware, software significantly better at detecting pancreatic cysts

As magnetic resonance imaging technology continues to advance year after year, so does MRI’s ability to accurately detect pancreatic cysts, according to a new study published in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.038).

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the relationship between the technical improvements in imaging techniques (specifically, MRI) and the presence of incidentally found PCLs [pancreatic cystic lesions],” said the study authors, led by Dr. Michael B. Wallace of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Dr. Wallace and his coinvestigators launched this retrospective descriptive study selecting the first 50 consecutive abdominal MRI patients at the Jacksonville Mayo Clinic during January and February of each year from 2005 through 2014, for a total of 500 cases who met inclusion criteria included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had preexisting symptomatic or asymptomatic pancreatitis, either acute or chronic, pancreatic masses, pancreatic cysts, pancreatic surgery, pancreatic symptoms, or any pancreas-related indications found by MRI.

The clinic underwent periodic MRI updates over the course of the 10-year study, along with requisite software updates to “take advantage of the new hardware technology,” the study explains. Major hardware improvements, provided by Siemens Medical Solutions USA, were Symphony/Sonata, Espree/Avanto, and Aera/Skyra, while software updates corresponding to each hardware update were VA, VB, and VD, respectively.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Furthermore, each software update had other, smaller upgrades, leading to a total of 20 combinations of MRI hardware and software on which MRIs were performed over the 10 years. Every MRI taken included “an axial and a coronal T2-weighted single-shot (HASTE) pulse sequence [with] TR 1400-1500 ms, TE 82-99 ms, and slice thickness 5-7 mm (gap, 0.5-0.7 mm).” Each MRI was analyzed by a pancreatic MRI specialist to find incidental cysts.

The number of patients found with pancreatic cysts increased incrementally from 2005 to 2014, with 2010 being the year with the highest number. A total of 208 subjects (41.6%) were found to have incidental cysts, but only 44 of these cases were discovered in the original MRI. The presence of cysts was associated with older age in patients who had them; only 20% of all subjects under 50 years of age had cysts, compared to 32.4% of those between 50 and 60 years, 54.9% of those between 60 and 70 years, and 61.5% of those over the age of 70 years (P less than .01).

Additionally, 56.4% of all subjects with diabetes (P less than .01), 59.0% of subjects with nonmelanoma skin cancer (P less than .03), and 58.1% of those with hepatocarcinoma (P less than .02) were also found to have cysts. Most striking, however, is that newer hardware and software permutations were able to detect cysts in 56.3% (Skyra) of patients who had them, compared with only 30.3% (Symphony) of patients who underwent MRI on older technology.

“The variable field strength” (1.5 T vs. 3 T) was not significantly related to the presence of PCLs,” Dr. Wallace and his coauthors concluded. “We believe this may be secondary to the lack of power of the analysis, because only 6% of the examinations were 3-T studies. Therefore, we speculate that this relationship may be confirmed if the number of 3-T studies increased.”

Males and females each made up roughly 50% of the study population, with a median age of 60 years and 85% being white. Additionally, 4% of subjects had a family history of pancreatic cancer, 12% had a personal history of solid organ transplant, and 53% had a personal history of smoking.

This study was funded by the Mayo Clinic. Dr. Wallace disclosed that he has received grant funding from Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, and travel support from Olympus. No other authors reported any financial disclosures.

The increasing prevalence of pancreatic cystic lesions on MRI scanning may provide an important opportunity for detection of early precursors of pancreatic cancer – or may represent just another insignificant incidental finding. What is the implication of a small asymptomatic cyst?

MRI scanning of the pancreas has revolutionized our ability to detect early cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatic cysts appear as well-defined, small, round fluid-filled structures within the pancreas. The inner structures – such as septations, nodules, and adjacent masses – offer clues as to the type of cyst and the risk of malignancy. But the real strength of pancreatic MRI scanning is the ability to detect and portray small cysts and the adjacent main pancreatic duct.

The size, number, and distribution of cysts over time can be tracked with MRI surveillance. By tracking the diameter of cysts and calculating the rate of growth of cysts, clinicians may be able to predict the development of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.

How should these patients be managed clinically? Once a cyst has been identified, are clinicians obligated to notify the patient, monitor the cyst with an established surveillance program, or biopsy the cyst? If the cyst is very small and benign appearing, can the clinician ignore the finding and perhaps not notify the patient?

Once again, we are watching dilemmas unfold as technology outstrips our understanding of diseases and their management. We are going to need some good correlations between imaging and tissue of pancreatic cystic lesions. In the meantime, it is important to reserve the use of pancreatic MRI scanning to high-risk patients or patients with CT scan abnormalities.

Dr. William R. Brugge, AGAF, is professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, and director, Pancreas Biliary Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant with Boston Scientific.

The increasing prevalence of pancreatic cystic lesions on MRI scanning may provide an important opportunity for detection of early precursors of pancreatic cancer – or may represent just another insignificant incidental finding. What is the implication of a small asymptomatic cyst?

MRI scanning of the pancreas has revolutionized our ability to detect early cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatic cysts appear as well-defined, small, round fluid-filled structures within the pancreas. The inner structures – such as septations, nodules, and adjacent masses – offer clues as to the type of cyst and the risk of malignancy. But the real strength of pancreatic MRI scanning is the ability to detect and portray small cysts and the adjacent main pancreatic duct.

The size, number, and distribution of cysts over time can be tracked with MRI surveillance. By tracking the diameter of cysts and calculating the rate of growth of cysts, clinicians may be able to predict the development of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.

How should these patients be managed clinically? Once a cyst has been identified, are clinicians obligated to notify the patient, monitor the cyst with an established surveillance program, or biopsy the cyst? If the cyst is very small and benign appearing, can the clinician ignore the finding and perhaps not notify the patient?

Once again, we are watching dilemmas unfold as technology outstrips our understanding of diseases and their management. We are going to need some good correlations between imaging and tissue of pancreatic cystic lesions. In the meantime, it is important to reserve the use of pancreatic MRI scanning to high-risk patients or patients with CT scan abnormalities.

Dr. William R. Brugge, AGAF, is professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, and director, Pancreas Biliary Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant with Boston Scientific.

The increasing prevalence of pancreatic cystic lesions on MRI scanning may provide an important opportunity for detection of early precursors of pancreatic cancer – or may represent just another insignificant incidental finding. What is the implication of a small asymptomatic cyst?

MRI scanning of the pancreas has revolutionized our ability to detect early cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatic cysts appear as well-defined, small, round fluid-filled structures within the pancreas. The inner structures – such as septations, nodules, and adjacent masses – offer clues as to the type of cyst and the risk of malignancy. But the real strength of pancreatic MRI scanning is the ability to detect and portray small cysts and the adjacent main pancreatic duct.

The size, number, and distribution of cysts over time can be tracked with MRI surveillance. By tracking the diameter of cysts and calculating the rate of growth of cysts, clinicians may be able to predict the development of malignancy in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms.

How should these patients be managed clinically? Once a cyst has been identified, are clinicians obligated to notify the patient, monitor the cyst with an established surveillance program, or biopsy the cyst? If the cyst is very small and benign appearing, can the clinician ignore the finding and perhaps not notify the patient?

Once again, we are watching dilemmas unfold as technology outstrips our understanding of diseases and their management. We are going to need some good correlations between imaging and tissue of pancreatic cystic lesions. In the meantime, it is important to reserve the use of pancreatic MRI scanning to high-risk patients or patients with CT scan abnormalities.

Dr. William R. Brugge, AGAF, is professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, and director, Pancreas Biliary Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston. He is a consultant with Boston Scientific.

As magnetic resonance imaging technology continues to advance year after year, so does MRI’s ability to accurately detect pancreatic cysts, according to a new study published in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.038).

“To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyze the relationship between the technical improvements in imaging techniques (specifically, MRI) and the presence of incidentally found PCLs [pancreatic cystic lesions],” said the study authors, led by Dr. Michael B. Wallace of the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Fla.

Dr. Wallace and his coinvestigators launched this retrospective descriptive study selecting the first 50 consecutive abdominal MRI patients at the Jacksonville Mayo Clinic during January and February of each year from 2005 through 2014, for a total of 500 cases who met inclusion criteria included in the study. Patients were excluded if they had preexisting symptomatic or asymptomatic pancreatitis, either acute or chronic, pancreatic masses, pancreatic cysts, pancreatic surgery, pancreatic symptoms, or any pancreas-related indications found by MRI.

The clinic underwent periodic MRI updates over the course of the 10-year study, along with requisite software updates to “take advantage of the new hardware technology,” the study explains. Major hardware improvements, provided by Siemens Medical Solutions USA, were Symphony/Sonata, Espree/Avanto, and Aera/Skyra, while software updates corresponding to each hardware update were VA, VB, and VD, respectively.

SOURCE: AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

Furthermore, each software update had other, smaller upgrades, leading to a total of 20 combinations of MRI hardware and software on which MRIs were performed over the 10 years. Every MRI taken included “an axial and a coronal T2-weighted single-shot (HASTE) pulse sequence [with] TR 1400-1500 ms, TE 82-99 ms, and slice thickness 5-7 mm (gap, 0.5-0.7 mm).” Each MRI was analyzed by a pancreatic MRI specialist to find incidental cysts.

The number of patients found with pancreatic cysts increased incrementally from 2005 to 2014, with 2010 being the year with the highest number. A total of 208 subjects (41.6%) were found to have incidental cysts, but only 44 of these cases were discovered in the original MRI. The presence of cysts was associated with older age in patients who had them; only 20% of all subjects under 50 years of age had cysts, compared to 32.4% of those between 50 and 60 years, 54.9% of those between 60 and 70 years, and 61.5% of those over the age of 70 years (P less than .01).