User login

Catheter-based transarterial therapies for hepatocellular cancer

Liver cancer is increasing in prevalence; from 2000 to 2010, the prevalence increased from 7.1 per 100,000 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 This increase is due in part to an increase in chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B and C and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2 In addition, liver metastases, especially from colorectal cancer and breast cancer, are also on the rise worldwide. More than 60% of patients with colorectal cancer will have a liver metastasis at some point in the course of their disease.

However, only 10% to 15% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma are candidates for surgical resection.3,4 And for patients who are not surgical candidates, there are currently no accepted guidelines on treatment.5 Treatment of metastatic liver cancer has consisted mainly of systemic chemotherapy, but if standard treatments fail, other options need to be considered.

A number of minimally invasive treatments are available for primary and metastatic liver cancer.6 These treatments are for the most part palliative, but in rare instances they are curative. They can be divided into percutaneous imaging-guided therapy (eg, radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation) and four catheter-based transarterial therapies:

- Bland embolization

- Chemoembolization

- Chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres

- Yttrium-90 radioembolization.

In this article, we focus only on the four catheter-based transarterial therapies, providing a brief description of each and a discussion of potential postprocedural complications and the key elements of postprocedural care.

The rationale for catheter-based transarterial therapy

Primary and metastatic liver malignancies depend mainly on the hepatic arterial blood supply for their survival and growth, whereas normal liver tissue is supplied mainly by the portal vein. Therapy applied through the hepatic arterial system is distributed directly to malignant tissue and spares healthy liver tissue. (Note: The leg is the route of access for all catheter-based transarterial therapies.)

BLAND EMBOLIZATION

In transarterial bland embolization, tiny spheres of a neutral (ie, bland) material are injected into the distal branches of the arteries that supply the tumor. These microemboli, 45 to 150 µm in diameter,7 permanently occlude the blood vessels.

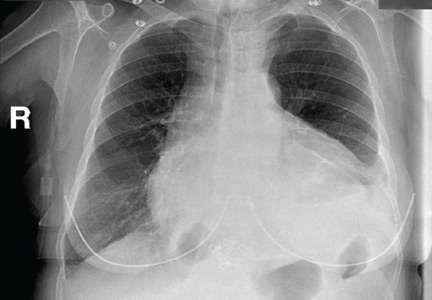

Bland embolization carries a risk of pulmonary embolism if there is shunting between the pulmonary and hepatic circulation via the hepatic vein.8,9 Fortunately, this serious complication is rare. Technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m MAA) scanning is done before the procedure to assess the risk.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Patients require follow-up with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure to evaluate tumor regression.

Further treatment

If follow-up CT shows that the lesion or lesions have not regressed or have increased in size, the embolization procedure can be repeated about 12 weeks after the initial treatment. The most likely cause of a poor response to therapy is failure to adequately identify all tumor-supplying vessels.10

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION

Transarterial chemoembolization targets the blood supply of the tumor with a combination of chemotherapeutic drugs and an embolizing agent. Standard chemotherapy agents used include doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitomycin-C. A microcatheter is advanced into the vessel supplying the tumor, and the combination drug is injected as close to the tumor as possible.11

Transarterial chemoembolization is the most commonly performed hepatic artery-directed therapy for liver cancer. It has been used to treat solitary tumors as well as multifocal disease. It allows for maximum embolization potential while preserving liver function.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome, characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain, is common after transarterial chemoembolization. Therefore, the patient is usually admitted to the hospital overnight for monitoring and control of symptoms such as pain and nausea. Mild abdominal pain is common and should resolve within several days; severe abdominal pain should be evaluated, as chemical and ischemic cholecystitis have been reported. Severe abdominal pain also raises concern for possible tumor rupture or liver infarction.

At the time of discharge, patients should be instructed to contact their clinician if they experience high fever, jaundice, or abdominal swelling. Liver function testing is not recommended within 7 to 10 days of treatment, as the expected rise in aminotransferase levels could prompt an unnecessary workup. Barring additional complications, patients should be seen in the office 2 weeks after the procedure.12

Lesions should be followed by serial contrast-enhanced CT to determine response to therapy. The current recommendation for stable patients is CT every 3 months for 2 years, and then every 6 months until active disease recurs.13

Safety concerns

A rare but serious concern after this procedure is fulminant hepatic failure, which has a high death rate. It has been reported in fewer than 1% of patients. Less severe complications include liver failure and infection.13

Further treatment

Patients with multifocal disease may require further treatment, usually 4 to 6 weeks after the initial procedure. If a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is already in place, the patient can undergo chemoembolization as long as liver function is preserved. However, these patients generally have a poorer prognosis.

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION WITH DRUG-ELUTING MICROSPHERES

In transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres, beads loaded with chemotherapeutic drugs provide controlled delivery, resulting in both ischemia of the tumor and slow release of chemotherapy.

Several types of beads are currently available, with different degrees of affinity for chemotherapy agents. An advantage of the beads is that they can be used in patients with tumors that show aggressive shunting or in tumors that have vascular invasion. The technique for delivering the beads is similar to that used in standard chemoembolization.14

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome is common. Treatment usually consists of hydration and control of pain and nausea. Follow-up includes serial CT to evaluate tumor response.

Safety concerns

Overall, this procedure is safe. A phase 1 and 2 trial15 showed adverse effects similar to those seen in chemoembolization. The most common adverse effect was a transient increase in liver enzymes. Serious complications such as tumor rupture, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and liver failure were rare.

YTTRIUM-90 RADIOEMBOLIZATION

In yttrium-90 radioembolization, radioactive microspheres are injected into the hepatic arterial supply. The procedure involves careful planning and is usually completed in stages.

The first stage involves angiography to map the hepatic vascular anatomy, as well as prophylactic embolization to protect against unintended delivery of the radioactive drug to vessels of the gastrointestinal tract (such as a branch of the hepatic artery that may supply the duodenum), causing tissue necrosis. Another reason for mapping is to look for any potential shunt between the tumor’s blood supply and the lung16,17 and thus prevent pulmonary embolism from the embolization procedure. The gastric mucosa and the salivary glands are also studied, as isolated gastric mucosal uptake indicates gastrointestinal vascular shunting.

The mapping stage involves injecting radioactive particles of technetium-99m microaggregated albumin, which are close in size to the yttrium-90 particles used during the actual procedure. The dose injected is usually 4 to 5 mCi (much lower than the typical tumor-therapy dose of 100–120 Gy), and imaging is done with either planar or single-photon emission CT. The patient is usually admitted for overnight observation after angiography.

In the second stage, 1 or 2 weeks later, the patient undergoes injection of the radiopharmaceuticals into the hepatic artery supplying the tumor. If disease burden is high or there is bilobar disease, the treatment is repeated in another 6 to 8 weeks. After the procedure, the patient is admitted to the hospital for observation by an inpatient team.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

The major concern after yttrium-90 radioembolization is reflux of the microspheres through unrecognized gastrointestinal channels,18 particularly into the mucosa of the stomach and proximal duodenum, causing the formation of nonhealing ulcers, which can cause major morbidity and even death. Antiulcer medications can be started immediately after the procedure.

Postembolization syndrome is frequently seen, and the fever usually responds to acetaminophen. Nausea and vomiting can be managed conservatively.19

The patient returns for a follow-up visit within 4 to 6 weeks of the injection procedure, mainly for assessment of liver function. A transient increase in liver enzymes and tumor markers may be seen at this time. A massive increase in liver enzyme levels should be investigated further.

Safety concerns

The postprocedural radiation exposure from the patient is within the acceptable safety range; therefore, no special precautions are necessary. However, since resin spheres are excreted in the urine, precautions are needed for urine disposal during the first 24 hours.20,21

Further treatments

If there is multifocal disease or a poor response to the initial treatment, a second session can be done 6 to 8 weeks after the first one. Before the second session, the liver tumor is imaged.22 For hepatocellular carcinoma, imaging may show shrinkage and necrosis of the tumor. For metastatic tumors, this imaging is important as it may show either failure or progression of disease.23 For this reason, functional imaging such as positron-emission tomography is important as it may show the extrahepatic spread of tumor, thereby halting further treatment. A complete blood cell count may also be done at 30 days to look for radiation-related cytopenia. A scrupulous log of the radiation dose received by the patient should be maintained.

PUNCTURE-SITE COMPLICATIONS

Hematoma

Hematoma at the puncture site is the most common complication of arterial access, with an incidence of 5% to 23%. The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity can also occur.

Simple hematomas exhibit a stable size and hemoglobin count and are managed conservatively. Initial management involves marking the site and checking frequently for a change in size, as well as applying pressure. Strict bed rest is recommended, with the affected leg kept straight for 4 to 6 hours. The hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit should be monitored for acute blood loss. Simple hematomas usually resolve in 2 to 4 weeks.

Complicated hematoma is characterized by continuous blood loss and can be compounded by a coagulopathy coexistent with underlying liver disease. Severe blood loss can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in the hemoglobin concentration.

Of note, a complicated hematoma can manifest superficially in the groin and may not change size over time, as most of the bleeding is intrapelvic.

Complicated hematomas require management by an interventional radiologist, including urgent noncontrast CT of the pelvis to evaluate for bleeding. In severe cases, embolization or stent graft placement by the interventional radiologist may be necessary. Open surgical evacuation is usually done only when compartment syndrome is a concern.24–26

Pseudoaneurysm

Pseudoaneurysm occurs in 0.5% to 9% of patients who undergo arterial puncture. It primarily arises from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and from inadequate compression after removal of the vascular sheath.

The signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those of hematoma, but it presents with a palpable thrill or bruit on auscultation. Ultrasonography is used for diagnosis.

As with hematoma treatment, bed rest and close monitoring are important. Mild pseudoaneurysm usually responds to manual compression for 20 to 30 minutes. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or percutaneous thrombin injection under ultrasonographic guidance.25,27

Infection

Infection of the puncture site is rare, with an incidence of about 1%. However, with the advent of closure devices such as Angio-Seal (St. Jude Medical), the incidence of infection has been on the rise, as these devices leave a tract from the skin to the vessel, providing a nidus for infection.25,28

The hallmarks of infection are straightforward and include pain, swelling, erythema, fever, and leukocytosis, and treatment involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage

In rare cases, puncture or postprocedural compression can damage surrounding nerves. The incidence of nerve damage is less than 0.5%. Symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site and limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage can also result from nerve sheath compression by a hematoma.25,29

Arterial thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry, but this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on the clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.25,30

SYSTEMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Postembolization syndrome

Postembolization syndrome is characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain. Although not a true complication of the procedure, it is an expected event in postprocedural care and should not be confused with systemic infection.

The pathophysiology of postembolization syndrome is not completely understood, but it is believed to be a sequela of liver necrosis and resulting inflammatory reaction.31 The incidence has been reported to be as high as 90% to 95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% of patients experience low-grade fever.32 Higher doses of chemotherapy and inadvertent embolization of the gallbladder have been associated with a higher incidence of postembolization syndrome.32

Symptoms typically peak within 5 days of the procedure and can last up to 10 days. If symptoms do not resolve during this time, infection should be ruled out. Blood cultures and aspirates from infarcted liver tissue remain sterile in postembolization syndrome, thus helping to rule out infection.32

Treatment with corticosteroids, analgesics, antinausea drugs, and intravenous fluids have all been used individually or in combination, with varying success rates. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment does not appear to play a role.33

Tumor lysis syndrome

Tumor lysis syndrome—a complex of severe metabolic disturbances potentially resulting in nephropathy and kidney failure—is extremely rare, with only a handful of individual case reports. It can occur with any embolization technique. Hsieh et al34 reported two cases arising 24 hours to 3 days after treatment. Hsieh et al,34 Burney,35 and Sakamoto et al36 reported tumor lysis syndrome in patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, suggesting that these patients may be at higher risk.

Tumor lysis syndrome typically presents with oliguria and subsequently progresses to electrolyte abnormalities, defined by Cairo and Bishop37 as a 25% increase or decrease in the serum concentration of two of the following within 7 days after tumor therapy: uric acid, potassium, calcium, or phosphate. Treatment involves correction of electrolyte disturbances, as well as aggressive rehydration and allopurinol for high uric acid levels.

Hypersensitivity to iodinated contrast

Contrast reactions range from immediate (within 1 hour) to delayed (from 1 hour to several days after administration). The most common symptoms of an immediate reaction are pruritus, flushing, angioedema, bronchospasm, wheezing, hypotension, and shock. Delayed reactions typically involve mild to moderate skin rash, mild angioedema, minor erythema multiforme, and, rarely, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.38 Dermatology consultation should always be considered for delayed reactions, particularly for severe skin manifestations.

Immediate reactions should be treated with intravenous (IV) fluid support and bronchodilators, and in life-threatening situations, epinephrine. Treatment of delayed reaction is guided by the symptoms. If the reaction is mild (pruritus or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider giving diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or by mouth. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphen-hydramine allergy. For severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 intramuscularly or 1:10,000 IV) should be given immediately.39

Ideally, high-risk patients (ie, those with known contrast allergies) should avoid contrast medium if possible. However, if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided. The American College of Radiology recommends the following preprocedural regimen: prednisone 50 mg by mouth 13 hours, 7 hours, and 1 hour before contrast administration, then 50 mg of diphenhydramine (IV, intramuscular, or oral) 1 hour before the procedure. Methylprednisolone 32 mg by mouth 12 hours and 2 hours before the procedure is an alternative to prednisone; 200 mg of IV hydrocortisone can be used if the patient cannot take oral medication.40–42

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents

In chemoembolization procedures, ethiodized oil is used as both a contrast medium and an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined and injected with the chemotherapy drug. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, but the mechanism is not well understood.

One study43 showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to lipiodol combined with cisplatin, a frequently used combination. The most common reaction was dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were also observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involved corticosteroids and antihistamines; blood pressure support with vasopressors was used as needed.43

Contrast-induced nephropathy

Contrast-induced nephropathy is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment.

Prophylactic strategies rely primarily on intravenous hydration before exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can also be considered, but its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended in the United States.

Managing acute renal failure, whether new or due to chronic renal impairment, should first involve rehydration. In cases of a severe rise in creatinine or uremia, dialysis should be considered as well as a nephrology consultation.44,45

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/. Accessed August 3, 2015.

- Cortez-Pinto H, Camilo ME. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH): diagnosis and clinical course. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 18:1089–1104.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004; 7:431–441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol 2002; 29:107–118.

- Geschwind JF, Salem R, Carr BI, et al. Yttrium-90 microspheres for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(suppl 1):S194–S205.

- Messersmith W, Laheru D, Hidalgo M. Recent advances in the pharmacological treatment of colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2003; 12:423–434.

- Bonomo G, Pedicini V, Monfardini L, et al. Bland embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using precise, tightly size-calibrated, anti-inflammatory microparticles: first clinical experience and one-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010; 33:552–559.

- Brown KT. Fatal pulmonary complications after arterial embolization with 40-120- micro m tris-acryl gelatin microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:197–200.

- Noguera JJ, Martínez-Cuesta A, Sangro B, Bilbao JI. Fatal pulmonary embolism after embolization of a hepatocellular carcinoma using microspheres. Radiologia 2008; 50:248–250. Spanish.

- Beland MD, Mayo-Smith WW. Image-guided tumor ablation: basic principles. In: Kaufman J, Lee MJ, eds. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2014.

- Huppert P. Current concepts in transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 2011; 36:677–683.

- Kanaan RA, Kim JS, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD, Barker GJ, McGuire PK. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:921–929.

- Brown DB, Cardella JF, Sacks D, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, embolization, and chemotherapeutic infusion for hepatic malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17:225–232.

- Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008; 31:269–280.

- Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:1100–1108.

- Mounajjed T, Salem R, Rhee TK, et al. Multi-institutional comparison of 99mTc-MAA lung shunt fraction for transcatheter Y-90 radioembolization. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Interventional Radiology, 2005. New Orleans, LA.

- Hung JC, Redfern MG, Mahoney DW, Thorson LM, Wiseman GA. Evaluation of macroaggregated albumin particle sizes for use in pulmonary shunt patient studies. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2000; 40:46–51.

- Yip D, Allen R, Ashton C, Jain S. Radiation-induced ulceration of the stomach secondary to hepatic embolization with radioactive yttrium microspheres in the treatment of metastatic colon cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19:347–349.

- Goin J, Dancey JE, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of post-embolization syndrome in the treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: trans-catheter arterial chemo-embolization versus yttrium-90 glass microspheres. World J Nucl Med 2004; 3:49–56.

- Gaba RC, Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Safety of yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization in patients with biliary obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:1213–1218.

- Kennedy A, Nag S, Salem R, et al. Recommendations for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies using yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy: a consensus panel report from the radioembolization brachytherapy oncology consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 68:13–23.

- Kosmider S, Tan TH, Yip D, Dowling R, Lichtenstein M, Gibbs P. Radioembolization in combination with systemic chemotherapy as first-line therapy for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011; 22:780–786.

- Sato K, Lewandowski RJ, Bui JT, et al. Treatment of unresectable primary and metastatic liver cancer with yttrium-90 microspheres (TheraSphere): assessment of hepatic arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006; 29:522–529.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1978; 130:455–460.

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse 2012; 32:16–29.

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2006; 23:119–125.

- Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation 2007; 115:2666–2674.

- Abando A, Hood D, Weaver F, Katz S. The use of the Angioseal device for femoral artery closure. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40:287–290.

- Tran DD, Andersen CA. Axillary sheath hematomas causing neurologic complications following arterial access. Ann Vasc Surg 2011; 25:697.e5–697.e8.

- Hall R. Vascular injuries resulting from arterial puncture of catheterization. Br J Surg 1971; 58:513–516.

- Wigmore SJ, Redhead DN, Thomson BN, et al. Postchemoembolisation syndrome—tumour necrosis or hepatocyte injury? Br J Cancer 2003; 89:1423–1427.

- Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001; 12:321–326.

- Castells A, Bruix J, Ayuso C, et al. Transarterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Antibiotic prophylaxis and clinical meaning of postembolization fever. J Hepatol 1995; 22:410–415.

- Hsieh PM, Hung KC, Chen YS. Tumor lysis syndrome after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: case reports and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:4726–4728.

- Burney IA. Acute tumor lysis syndrome after transcatheter chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. South Med J 1998; 91:467–470.

- Sakamoto N, Monzawa S, Nagano H, Nishizaki H, Arai Y, Sugimura K. Acute tumor lysis syndrome caused by transcatheter oily chemoembolization in a patient with a large hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007; 30:508–511.

- Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol 2004; 127:3–11.

- Brockow K, Christiansen C, Kanny G, et al; ENDA; EAACI interest group on drug hypersensitivity. Management of hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy 2005; 60:150–158.

- Cochran ST. Anaphylactoid reactions to radiocontrast media. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2005; 5:28–31.

- Lasser EC, Berry CC, Talner LB, et al. Pretreatment with corticosteroids to alleviate reactions to intravenous contrast material. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:845–849.

- Greenberger PA, Halwig JM, Patterson R, Wallemark CB. Emergency administration of radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1986; 77:630–634.

- Greenberger PA, Patterson R. The prevention of immediate generalized reactions to radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1991; 87:867–872.

- Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Katamura Y, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to transcatheter chemoembolization with cisplatin and lipiodol suspension for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:1219–1225.

- Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:379–386.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, et al; CIN Consensus Working Panel. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98:27K–36K.

Liver cancer is increasing in prevalence; from 2000 to 2010, the prevalence increased from 7.1 per 100,000 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 This increase is due in part to an increase in chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B and C and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2 In addition, liver metastases, especially from colorectal cancer and breast cancer, are also on the rise worldwide. More than 60% of patients with colorectal cancer will have a liver metastasis at some point in the course of their disease.

However, only 10% to 15% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma are candidates for surgical resection.3,4 And for patients who are not surgical candidates, there are currently no accepted guidelines on treatment.5 Treatment of metastatic liver cancer has consisted mainly of systemic chemotherapy, but if standard treatments fail, other options need to be considered.

A number of minimally invasive treatments are available for primary and metastatic liver cancer.6 These treatments are for the most part palliative, but in rare instances they are curative. They can be divided into percutaneous imaging-guided therapy (eg, radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation) and four catheter-based transarterial therapies:

- Bland embolization

- Chemoembolization

- Chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres

- Yttrium-90 radioembolization.

In this article, we focus only on the four catheter-based transarterial therapies, providing a brief description of each and a discussion of potential postprocedural complications and the key elements of postprocedural care.

The rationale for catheter-based transarterial therapy

Primary and metastatic liver malignancies depend mainly on the hepatic arterial blood supply for their survival and growth, whereas normal liver tissue is supplied mainly by the portal vein. Therapy applied through the hepatic arterial system is distributed directly to malignant tissue and spares healthy liver tissue. (Note: The leg is the route of access for all catheter-based transarterial therapies.)

BLAND EMBOLIZATION

In transarterial bland embolization, tiny spheres of a neutral (ie, bland) material are injected into the distal branches of the arteries that supply the tumor. These microemboli, 45 to 150 µm in diameter,7 permanently occlude the blood vessels.

Bland embolization carries a risk of pulmonary embolism if there is shunting between the pulmonary and hepatic circulation via the hepatic vein.8,9 Fortunately, this serious complication is rare. Technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m MAA) scanning is done before the procedure to assess the risk.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Patients require follow-up with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure to evaluate tumor regression.

Further treatment

If follow-up CT shows that the lesion or lesions have not regressed or have increased in size, the embolization procedure can be repeated about 12 weeks after the initial treatment. The most likely cause of a poor response to therapy is failure to adequately identify all tumor-supplying vessels.10

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION

Transarterial chemoembolization targets the blood supply of the tumor with a combination of chemotherapeutic drugs and an embolizing agent. Standard chemotherapy agents used include doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitomycin-C. A microcatheter is advanced into the vessel supplying the tumor, and the combination drug is injected as close to the tumor as possible.11

Transarterial chemoembolization is the most commonly performed hepatic artery-directed therapy for liver cancer. It has been used to treat solitary tumors as well as multifocal disease. It allows for maximum embolization potential while preserving liver function.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome, characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain, is common after transarterial chemoembolization. Therefore, the patient is usually admitted to the hospital overnight for monitoring and control of symptoms such as pain and nausea. Mild abdominal pain is common and should resolve within several days; severe abdominal pain should be evaluated, as chemical and ischemic cholecystitis have been reported. Severe abdominal pain also raises concern for possible tumor rupture or liver infarction.

At the time of discharge, patients should be instructed to contact their clinician if they experience high fever, jaundice, or abdominal swelling. Liver function testing is not recommended within 7 to 10 days of treatment, as the expected rise in aminotransferase levels could prompt an unnecessary workup. Barring additional complications, patients should be seen in the office 2 weeks after the procedure.12

Lesions should be followed by serial contrast-enhanced CT to determine response to therapy. The current recommendation for stable patients is CT every 3 months for 2 years, and then every 6 months until active disease recurs.13

Safety concerns

A rare but serious concern after this procedure is fulminant hepatic failure, which has a high death rate. It has been reported in fewer than 1% of patients. Less severe complications include liver failure and infection.13

Further treatment

Patients with multifocal disease may require further treatment, usually 4 to 6 weeks after the initial procedure. If a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is already in place, the patient can undergo chemoembolization as long as liver function is preserved. However, these patients generally have a poorer prognosis.

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION WITH DRUG-ELUTING MICROSPHERES

In transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres, beads loaded with chemotherapeutic drugs provide controlled delivery, resulting in both ischemia of the tumor and slow release of chemotherapy.

Several types of beads are currently available, with different degrees of affinity for chemotherapy agents. An advantage of the beads is that they can be used in patients with tumors that show aggressive shunting or in tumors that have vascular invasion. The technique for delivering the beads is similar to that used in standard chemoembolization.14

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome is common. Treatment usually consists of hydration and control of pain and nausea. Follow-up includes serial CT to evaluate tumor response.

Safety concerns

Overall, this procedure is safe. A phase 1 and 2 trial15 showed adverse effects similar to those seen in chemoembolization. The most common adverse effect was a transient increase in liver enzymes. Serious complications such as tumor rupture, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and liver failure were rare.

YTTRIUM-90 RADIOEMBOLIZATION

In yttrium-90 radioembolization, radioactive microspheres are injected into the hepatic arterial supply. The procedure involves careful planning and is usually completed in stages.

The first stage involves angiography to map the hepatic vascular anatomy, as well as prophylactic embolization to protect against unintended delivery of the radioactive drug to vessels of the gastrointestinal tract (such as a branch of the hepatic artery that may supply the duodenum), causing tissue necrosis. Another reason for mapping is to look for any potential shunt between the tumor’s blood supply and the lung16,17 and thus prevent pulmonary embolism from the embolization procedure. The gastric mucosa and the salivary glands are also studied, as isolated gastric mucosal uptake indicates gastrointestinal vascular shunting.

The mapping stage involves injecting radioactive particles of technetium-99m microaggregated albumin, which are close in size to the yttrium-90 particles used during the actual procedure. The dose injected is usually 4 to 5 mCi (much lower than the typical tumor-therapy dose of 100–120 Gy), and imaging is done with either planar or single-photon emission CT. The patient is usually admitted for overnight observation after angiography.

In the second stage, 1 or 2 weeks later, the patient undergoes injection of the radiopharmaceuticals into the hepatic artery supplying the tumor. If disease burden is high or there is bilobar disease, the treatment is repeated in another 6 to 8 weeks. After the procedure, the patient is admitted to the hospital for observation by an inpatient team.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

The major concern after yttrium-90 radioembolization is reflux of the microspheres through unrecognized gastrointestinal channels,18 particularly into the mucosa of the stomach and proximal duodenum, causing the formation of nonhealing ulcers, which can cause major morbidity and even death. Antiulcer medications can be started immediately after the procedure.

Postembolization syndrome is frequently seen, and the fever usually responds to acetaminophen. Nausea and vomiting can be managed conservatively.19

The patient returns for a follow-up visit within 4 to 6 weeks of the injection procedure, mainly for assessment of liver function. A transient increase in liver enzymes and tumor markers may be seen at this time. A massive increase in liver enzyme levels should be investigated further.

Safety concerns

The postprocedural radiation exposure from the patient is within the acceptable safety range; therefore, no special precautions are necessary. However, since resin spheres are excreted in the urine, precautions are needed for urine disposal during the first 24 hours.20,21

Further treatments

If there is multifocal disease or a poor response to the initial treatment, a second session can be done 6 to 8 weeks after the first one. Before the second session, the liver tumor is imaged.22 For hepatocellular carcinoma, imaging may show shrinkage and necrosis of the tumor. For metastatic tumors, this imaging is important as it may show either failure or progression of disease.23 For this reason, functional imaging such as positron-emission tomography is important as it may show the extrahepatic spread of tumor, thereby halting further treatment. A complete blood cell count may also be done at 30 days to look for radiation-related cytopenia. A scrupulous log of the radiation dose received by the patient should be maintained.

PUNCTURE-SITE COMPLICATIONS

Hematoma

Hematoma at the puncture site is the most common complication of arterial access, with an incidence of 5% to 23%. The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity can also occur.

Simple hematomas exhibit a stable size and hemoglobin count and are managed conservatively. Initial management involves marking the site and checking frequently for a change in size, as well as applying pressure. Strict bed rest is recommended, with the affected leg kept straight for 4 to 6 hours. The hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit should be monitored for acute blood loss. Simple hematomas usually resolve in 2 to 4 weeks.

Complicated hematoma is characterized by continuous blood loss and can be compounded by a coagulopathy coexistent with underlying liver disease. Severe blood loss can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in the hemoglobin concentration.

Of note, a complicated hematoma can manifest superficially in the groin and may not change size over time, as most of the bleeding is intrapelvic.

Complicated hematomas require management by an interventional radiologist, including urgent noncontrast CT of the pelvis to evaluate for bleeding. In severe cases, embolization or stent graft placement by the interventional radiologist may be necessary. Open surgical evacuation is usually done only when compartment syndrome is a concern.24–26

Pseudoaneurysm

Pseudoaneurysm occurs in 0.5% to 9% of patients who undergo arterial puncture. It primarily arises from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and from inadequate compression after removal of the vascular sheath.

The signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those of hematoma, but it presents with a palpable thrill or bruit on auscultation. Ultrasonography is used for diagnosis.

As with hematoma treatment, bed rest and close monitoring are important. Mild pseudoaneurysm usually responds to manual compression for 20 to 30 minutes. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or percutaneous thrombin injection under ultrasonographic guidance.25,27

Infection

Infection of the puncture site is rare, with an incidence of about 1%. However, with the advent of closure devices such as Angio-Seal (St. Jude Medical), the incidence of infection has been on the rise, as these devices leave a tract from the skin to the vessel, providing a nidus for infection.25,28

The hallmarks of infection are straightforward and include pain, swelling, erythema, fever, and leukocytosis, and treatment involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage

In rare cases, puncture or postprocedural compression can damage surrounding nerves. The incidence of nerve damage is less than 0.5%. Symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site and limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage can also result from nerve sheath compression by a hematoma.25,29

Arterial thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry, but this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on the clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.25,30

SYSTEMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Postembolization syndrome

Postembolization syndrome is characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain. Although not a true complication of the procedure, it is an expected event in postprocedural care and should not be confused with systemic infection.

The pathophysiology of postembolization syndrome is not completely understood, but it is believed to be a sequela of liver necrosis and resulting inflammatory reaction.31 The incidence has been reported to be as high as 90% to 95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% of patients experience low-grade fever.32 Higher doses of chemotherapy and inadvertent embolization of the gallbladder have been associated with a higher incidence of postembolization syndrome.32

Symptoms typically peak within 5 days of the procedure and can last up to 10 days. If symptoms do not resolve during this time, infection should be ruled out. Blood cultures and aspirates from infarcted liver tissue remain sterile in postembolization syndrome, thus helping to rule out infection.32

Treatment with corticosteroids, analgesics, antinausea drugs, and intravenous fluids have all been used individually or in combination, with varying success rates. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment does not appear to play a role.33

Tumor lysis syndrome

Tumor lysis syndrome—a complex of severe metabolic disturbances potentially resulting in nephropathy and kidney failure—is extremely rare, with only a handful of individual case reports. It can occur with any embolization technique. Hsieh et al34 reported two cases arising 24 hours to 3 days after treatment. Hsieh et al,34 Burney,35 and Sakamoto et al36 reported tumor lysis syndrome in patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, suggesting that these patients may be at higher risk.

Tumor lysis syndrome typically presents with oliguria and subsequently progresses to electrolyte abnormalities, defined by Cairo and Bishop37 as a 25% increase or decrease in the serum concentration of two of the following within 7 days after tumor therapy: uric acid, potassium, calcium, or phosphate. Treatment involves correction of electrolyte disturbances, as well as aggressive rehydration and allopurinol for high uric acid levels.

Hypersensitivity to iodinated contrast

Contrast reactions range from immediate (within 1 hour) to delayed (from 1 hour to several days after administration). The most common symptoms of an immediate reaction are pruritus, flushing, angioedema, bronchospasm, wheezing, hypotension, and shock. Delayed reactions typically involve mild to moderate skin rash, mild angioedema, minor erythema multiforme, and, rarely, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.38 Dermatology consultation should always be considered for delayed reactions, particularly for severe skin manifestations.

Immediate reactions should be treated with intravenous (IV) fluid support and bronchodilators, and in life-threatening situations, epinephrine. Treatment of delayed reaction is guided by the symptoms. If the reaction is mild (pruritus or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider giving diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or by mouth. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphen-hydramine allergy. For severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 intramuscularly or 1:10,000 IV) should be given immediately.39

Ideally, high-risk patients (ie, those with known contrast allergies) should avoid contrast medium if possible. However, if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided. The American College of Radiology recommends the following preprocedural regimen: prednisone 50 mg by mouth 13 hours, 7 hours, and 1 hour before contrast administration, then 50 mg of diphenhydramine (IV, intramuscular, or oral) 1 hour before the procedure. Methylprednisolone 32 mg by mouth 12 hours and 2 hours before the procedure is an alternative to prednisone; 200 mg of IV hydrocortisone can be used if the patient cannot take oral medication.40–42

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents

In chemoembolization procedures, ethiodized oil is used as both a contrast medium and an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined and injected with the chemotherapy drug. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, but the mechanism is not well understood.

One study43 showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to lipiodol combined with cisplatin, a frequently used combination. The most common reaction was dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were also observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involved corticosteroids and antihistamines; blood pressure support with vasopressors was used as needed.43

Contrast-induced nephropathy

Contrast-induced nephropathy is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment.

Prophylactic strategies rely primarily on intravenous hydration before exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can also be considered, but its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended in the United States.

Managing acute renal failure, whether new or due to chronic renal impairment, should first involve rehydration. In cases of a severe rise in creatinine or uremia, dialysis should be considered as well as a nephrology consultation.44,45

Liver cancer is increasing in prevalence; from 2000 to 2010, the prevalence increased from 7.1 per 100,000 to 8.4 per 100,000 people.1 This increase is due in part to an increase in chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B and C and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.2 In addition, liver metastases, especially from colorectal cancer and breast cancer, are also on the rise worldwide. More than 60% of patients with colorectal cancer will have a liver metastasis at some point in the course of their disease.

However, only 10% to 15% of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma are candidates for surgical resection.3,4 And for patients who are not surgical candidates, there are currently no accepted guidelines on treatment.5 Treatment of metastatic liver cancer has consisted mainly of systemic chemotherapy, but if standard treatments fail, other options need to be considered.

A number of minimally invasive treatments are available for primary and metastatic liver cancer.6 These treatments are for the most part palliative, but in rare instances they are curative. They can be divided into percutaneous imaging-guided therapy (eg, radiofrequency ablation, microwave ablation) and four catheter-based transarterial therapies:

- Bland embolization

- Chemoembolization

- Chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres

- Yttrium-90 radioembolization.

In this article, we focus only on the four catheter-based transarterial therapies, providing a brief description of each and a discussion of potential postprocedural complications and the key elements of postprocedural care.

The rationale for catheter-based transarterial therapy

Primary and metastatic liver malignancies depend mainly on the hepatic arterial blood supply for their survival and growth, whereas normal liver tissue is supplied mainly by the portal vein. Therapy applied through the hepatic arterial system is distributed directly to malignant tissue and spares healthy liver tissue. (Note: The leg is the route of access for all catheter-based transarterial therapies.)

BLAND EMBOLIZATION

In transarterial bland embolization, tiny spheres of a neutral (ie, bland) material are injected into the distal branches of the arteries that supply the tumor. These microemboli, 45 to 150 µm in diameter,7 permanently occlude the blood vessels.

Bland embolization carries a risk of pulmonary embolism if there is shunting between the pulmonary and hepatic circulation via the hepatic vein.8,9 Fortunately, this serious complication is rare. Technetium-99m macroaggregated albumin (Tc-99m MAA) scanning is done before the procedure to assess the risk.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Patients require follow-up with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) 6 to 8 weeks after the procedure to evaluate tumor regression.

Further treatment

If follow-up CT shows that the lesion or lesions have not regressed or have increased in size, the embolization procedure can be repeated about 12 weeks after the initial treatment. The most likely cause of a poor response to therapy is failure to adequately identify all tumor-supplying vessels.10

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION

Transarterial chemoembolization targets the blood supply of the tumor with a combination of chemotherapeutic drugs and an embolizing agent. Standard chemotherapy agents used include doxorubicin, cisplatin, and mitomycin-C. A microcatheter is advanced into the vessel supplying the tumor, and the combination drug is injected as close to the tumor as possible.11

Transarterial chemoembolization is the most commonly performed hepatic artery-directed therapy for liver cancer. It has been used to treat solitary tumors as well as multifocal disease. It allows for maximum embolization potential while preserving liver function.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome, characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain, is common after transarterial chemoembolization. Therefore, the patient is usually admitted to the hospital overnight for monitoring and control of symptoms such as pain and nausea. Mild abdominal pain is common and should resolve within several days; severe abdominal pain should be evaluated, as chemical and ischemic cholecystitis have been reported. Severe abdominal pain also raises concern for possible tumor rupture or liver infarction.

At the time of discharge, patients should be instructed to contact their clinician if they experience high fever, jaundice, or abdominal swelling. Liver function testing is not recommended within 7 to 10 days of treatment, as the expected rise in aminotransferase levels could prompt an unnecessary workup. Barring additional complications, patients should be seen in the office 2 weeks after the procedure.12

Lesions should be followed by serial contrast-enhanced CT to determine response to therapy. The current recommendation for stable patients is CT every 3 months for 2 years, and then every 6 months until active disease recurs.13

Safety concerns

A rare but serious concern after this procedure is fulminant hepatic failure, which has a high death rate. It has been reported in fewer than 1% of patients. Less severe complications include liver failure and infection.13

Further treatment

Patients with multifocal disease may require further treatment, usually 4 to 6 weeks after the initial procedure. If a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is already in place, the patient can undergo chemoembolization as long as liver function is preserved. However, these patients generally have a poorer prognosis.

CHEMOEMBOLIZATION WITH DRUG-ELUTING MICROSPHERES

In transarterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting microspheres, beads loaded with chemotherapeutic drugs provide controlled delivery, resulting in both ischemia of the tumor and slow release of chemotherapy.

Several types of beads are currently available, with different degrees of affinity for chemotherapy agents. An advantage of the beads is that they can be used in patients with tumors that show aggressive shunting or in tumors that have vascular invasion. The technique for delivering the beads is similar to that used in standard chemoembolization.14

Posttreatment care and follow-up

Postembolization syndrome is common. Treatment usually consists of hydration and control of pain and nausea. Follow-up includes serial CT to evaluate tumor response.

Safety concerns

Overall, this procedure is safe. A phase 1 and 2 trial15 showed adverse effects similar to those seen in chemoembolization. The most common adverse effect was a transient increase in liver enzymes. Serious complications such as tumor rupture, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and liver failure were rare.

YTTRIUM-90 RADIOEMBOLIZATION

In yttrium-90 radioembolization, radioactive microspheres are injected into the hepatic arterial supply. The procedure involves careful planning and is usually completed in stages.

The first stage involves angiography to map the hepatic vascular anatomy, as well as prophylactic embolization to protect against unintended delivery of the radioactive drug to vessels of the gastrointestinal tract (such as a branch of the hepatic artery that may supply the duodenum), causing tissue necrosis. Another reason for mapping is to look for any potential shunt between the tumor’s blood supply and the lung16,17 and thus prevent pulmonary embolism from the embolization procedure. The gastric mucosa and the salivary glands are also studied, as isolated gastric mucosal uptake indicates gastrointestinal vascular shunting.

The mapping stage involves injecting radioactive particles of technetium-99m microaggregated albumin, which are close in size to the yttrium-90 particles used during the actual procedure. The dose injected is usually 4 to 5 mCi (much lower than the typical tumor-therapy dose of 100–120 Gy), and imaging is done with either planar or single-photon emission CT. The patient is usually admitted for overnight observation after angiography.

In the second stage, 1 or 2 weeks later, the patient undergoes injection of the radiopharmaceuticals into the hepatic artery supplying the tumor. If disease burden is high or there is bilobar disease, the treatment is repeated in another 6 to 8 weeks. After the procedure, the patient is admitted to the hospital for observation by an inpatient team.

Posttreatment care and follow-up

The major concern after yttrium-90 radioembolization is reflux of the microspheres through unrecognized gastrointestinal channels,18 particularly into the mucosa of the stomach and proximal duodenum, causing the formation of nonhealing ulcers, which can cause major morbidity and even death. Antiulcer medications can be started immediately after the procedure.

Postembolization syndrome is frequently seen, and the fever usually responds to acetaminophen. Nausea and vomiting can be managed conservatively.19

The patient returns for a follow-up visit within 4 to 6 weeks of the injection procedure, mainly for assessment of liver function. A transient increase in liver enzymes and tumor markers may be seen at this time. A massive increase in liver enzyme levels should be investigated further.

Safety concerns

The postprocedural radiation exposure from the patient is within the acceptable safety range; therefore, no special precautions are necessary. However, since resin spheres are excreted in the urine, precautions are needed for urine disposal during the first 24 hours.20,21

Further treatments

If there is multifocal disease or a poor response to the initial treatment, a second session can be done 6 to 8 weeks after the first one. Before the second session, the liver tumor is imaged.22 For hepatocellular carcinoma, imaging may show shrinkage and necrosis of the tumor. For metastatic tumors, this imaging is important as it may show either failure or progression of disease.23 For this reason, functional imaging such as positron-emission tomography is important as it may show the extrahepatic spread of tumor, thereby halting further treatment. A complete blood cell count may also be done at 30 days to look for radiation-related cytopenia. A scrupulous log of the radiation dose received by the patient should be maintained.

PUNCTURE-SITE COMPLICATIONS

Hematoma

Hematoma at the puncture site is the most common complication of arterial access, with an incidence of 5% to 23%. The main clinical findings are erythema and swelling at the puncture site, with a palpable hardening of the skin. Pain and decreased range of motion in the affected extremity can also occur.

Simple hematomas exhibit a stable size and hemoglobin count and are managed conservatively. Initial management involves marking the site and checking frequently for a change in size, as well as applying pressure. Strict bed rest is recommended, with the affected leg kept straight for 4 to 6 hours. The hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit should be monitored for acute blood loss. Simple hematomas usually resolve in 2 to 4 weeks.

Complicated hematoma is characterized by continuous blood loss and can be compounded by a coagulopathy coexistent with underlying liver disease. Severe blood loss can result in hypotension and tachycardia with an acute drop in the hemoglobin concentration.

Of note, a complicated hematoma can manifest superficially in the groin and may not change size over time, as most of the bleeding is intrapelvic.

Complicated hematomas require management by an interventional radiologist, including urgent noncontrast CT of the pelvis to evaluate for bleeding. In severe cases, embolization or stent graft placement by the interventional radiologist may be necessary. Open surgical evacuation is usually done only when compartment syndrome is a concern.24–26

Pseudoaneurysm

Pseudoaneurysm occurs in 0.5% to 9% of patients who undergo arterial puncture. It primarily arises from difficulty with cannulation of the artery and from inadequate compression after removal of the vascular sheath.

The signs of pseudoaneurysm are similar to those of hematoma, but it presents with a palpable thrill or bruit on auscultation. Ultrasonography is used for diagnosis.

As with hematoma treatment, bed rest and close monitoring are important. Mild pseudoaneurysm usually responds to manual compression for 20 to 30 minutes. More severe cases may require surgical intervention or percutaneous thrombin injection under ultrasonographic guidance.25,27

Infection

Infection of the puncture site is rare, with an incidence of about 1%. However, with the advent of closure devices such as Angio-Seal (St. Jude Medical), the incidence of infection has been on the rise, as these devices leave a tract from the skin to the vessel, providing a nidus for infection.25,28

The hallmarks of infection are straightforward and include pain, swelling, erythema, fever, and leukocytosis, and treatment involves antibiotics.

Nerve damage

In rare cases, puncture or postprocedural compression can damage surrounding nerves. The incidence of nerve damage is less than 0.5%. Symptoms include numbness and tingling at the access site and limb weakness. Treatment involves symptomatic management and physical therapy. Nerve damage can also result from nerve sheath compression by a hematoma.25,29

Arterial thrombosis

Arterial thrombosis can occur at the site of sheath entry, but this can be avoided by administering anticoagulation during the procedure. Classic symptoms include the “5 P’s”: pain, pallor, paresthesia, pulselessness, and paralysis. Treatment depends on the clot burden, with small clots potentially dissolving and larger clots requiring possible thrombolysis, embolectomy, or surgery.25,30

SYSTEMIC CONSIDERATIONS

Postembolization syndrome

Postembolization syndrome is characterized by low-grade fever, mild leukocytosis, and pain. Although not a true complication of the procedure, it is an expected event in postprocedural care and should not be confused with systemic infection.

The pathophysiology of postembolization syndrome is not completely understood, but it is believed to be a sequela of liver necrosis and resulting inflammatory reaction.31 The incidence has been reported to be as high as 90% to 95%, with 81% of patients reporting nausea, vomiting, malaise, and myalgias; 42% of patients experience low-grade fever.32 Higher doses of chemotherapy and inadvertent embolization of the gallbladder have been associated with a higher incidence of postembolization syndrome.32

Symptoms typically peak within 5 days of the procedure and can last up to 10 days. If symptoms do not resolve during this time, infection should be ruled out. Blood cultures and aspirates from infarcted liver tissue remain sterile in postembolization syndrome, thus helping to rule out infection.32

Treatment with corticosteroids, analgesics, antinausea drugs, and intravenous fluids have all been used individually or in combination, with varying success rates. Prophylactic antibiotic treatment does not appear to play a role.33

Tumor lysis syndrome

Tumor lysis syndrome—a complex of severe metabolic disturbances potentially resulting in nephropathy and kidney failure—is extremely rare, with only a handful of individual case reports. It can occur with any embolization technique. Hsieh et al34 reported two cases arising 24 hours to 3 days after treatment. Hsieh et al,34 Burney,35 and Sakamoto et al36 reported tumor lysis syndrome in patients with tumors larger than 5 cm, suggesting that these patients may be at higher risk.

Tumor lysis syndrome typically presents with oliguria and subsequently progresses to electrolyte abnormalities, defined by Cairo and Bishop37 as a 25% increase or decrease in the serum concentration of two of the following within 7 days after tumor therapy: uric acid, potassium, calcium, or phosphate. Treatment involves correction of electrolyte disturbances, as well as aggressive rehydration and allopurinol for high uric acid levels.

Hypersensitivity to iodinated contrast

Contrast reactions range from immediate (within 1 hour) to delayed (from 1 hour to several days after administration). The most common symptoms of an immediate reaction are pruritus, flushing, angioedema, bronchospasm, wheezing, hypotension, and shock. Delayed reactions typically involve mild to moderate skin rash, mild angioedema, minor erythema multiforme, and, rarely, Stevens-Johnson syndrome.38 Dermatology consultation should always be considered for delayed reactions, particularly for severe skin manifestations.

Immediate reactions should be treated with intravenous (IV) fluid support and bronchodilators, and in life-threatening situations, epinephrine. Treatment of delayed reaction is guided by the symptoms. If the reaction is mild (pruritus or rash), secure IV access, have oxygen on standby, begin IV fluids, and consider giving diphenhydramine 50 mg IV or by mouth. Hydrocortisone 200 mg IV can be substituted if the patient has a diphen-hydramine allergy. For severe reactions, epinephrine (1:1,000 intramuscularly or 1:10,000 IV) should be given immediately.39

Ideally, high-risk patients (ie, those with known contrast allergies) should avoid contrast medium if possible. However, if contrast is necessary, premedication should be provided. The American College of Radiology recommends the following preprocedural regimen: prednisone 50 mg by mouth 13 hours, 7 hours, and 1 hour before contrast administration, then 50 mg of diphenhydramine (IV, intramuscular, or oral) 1 hour before the procedure. Methylprednisolone 32 mg by mouth 12 hours and 2 hours before the procedure is an alternative to prednisone; 200 mg of IV hydrocortisone can be used if the patient cannot take oral medication.40–42

Hypersensitivity to embolizing agents

In chemoembolization procedures, ethiodized oil is used as both a contrast medium and an occluding agent. This lipiodol suspension is combined and injected with the chemotherapy drug. Hypersensitivity reactions have been reported, but the mechanism is not well understood.

One study43 showed a 3.2% occurrence of hypersensitivity to lipiodol combined with cisplatin, a frequently used combination. The most common reaction was dyspnea and urticaria (observed in 57% of patients); bronchospasm, altered mental status, and pruritus were also observed in lower frequencies. Treatment involved corticosteroids and antihistamines; blood pressure support with vasopressors was used as needed.43

Contrast-induced nephropathy

Contrast-induced nephropathy is defined as a 25% rise in serum creatinine from baseline after exposure to iodinated contrast agents. Patients particularly at risk include those with preexisting renal impairment, diabetes mellitus, or acute renal failure due to dehydration. Other risk factors include age, preexisting cardiovascular disease, and hepatic impairment.

Prophylactic strategies rely primarily on intravenous hydration before exposure. The use of N-acetylcysteine can also be considered, but its effectiveness is controversial and it is not routinely recommended in the United States.

Managing acute renal failure, whether new or due to chronic renal impairment, should first involve rehydration. In cases of a severe rise in creatinine or uremia, dialysis should be considered as well as a nephrology consultation.44,45

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/. Accessed August 3, 2015.

- Cortez-Pinto H, Camilo ME. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH): diagnosis and clinical course. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 18:1089–1104.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004; 7:431–441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol 2002; 29:107–118.

- Geschwind JF, Salem R, Carr BI, et al. Yttrium-90 microspheres for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(suppl 1):S194–S205.

- Messersmith W, Laheru D, Hidalgo M. Recent advances in the pharmacological treatment of colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2003; 12:423–434.

- Bonomo G, Pedicini V, Monfardini L, et al. Bland embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using precise, tightly size-calibrated, anti-inflammatory microparticles: first clinical experience and one-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010; 33:552–559.

- Brown KT. Fatal pulmonary complications after arterial embolization with 40-120- micro m tris-acryl gelatin microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:197–200.

- Noguera JJ, Martínez-Cuesta A, Sangro B, Bilbao JI. Fatal pulmonary embolism after embolization of a hepatocellular carcinoma using microspheres. Radiologia 2008; 50:248–250. Spanish.

- Beland MD, Mayo-Smith WW. Image-guided tumor ablation: basic principles. In: Kaufman J, Lee MJ, eds. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2014.

- Huppert P. Current concepts in transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 2011; 36:677–683.

- Kanaan RA, Kim JS, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD, Barker GJ, McGuire PK. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:921–929.

- Brown DB, Cardella JF, Sacks D, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, embolization, and chemotherapeutic infusion for hepatic malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17:225–232.

- Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008; 31:269–280.

- Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:1100–1108.

- Mounajjed T, Salem R, Rhee TK, et al. Multi-institutional comparison of 99mTc-MAA lung shunt fraction for transcatheter Y-90 radioembolization. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Interventional Radiology, 2005. New Orleans, LA.

- Hung JC, Redfern MG, Mahoney DW, Thorson LM, Wiseman GA. Evaluation of macroaggregated albumin particle sizes for use in pulmonary shunt patient studies. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2000; 40:46–51.

- Yip D, Allen R, Ashton C, Jain S. Radiation-induced ulceration of the stomach secondary to hepatic embolization with radioactive yttrium microspheres in the treatment of metastatic colon cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19:347–349.

- Goin J, Dancey JE, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of post-embolization syndrome in the treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: trans-catheter arterial chemo-embolization versus yttrium-90 glass microspheres. World J Nucl Med 2004; 3:49–56.

- Gaba RC, Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Safety of yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization in patients with biliary obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:1213–1218.

- Kennedy A, Nag S, Salem R, et al. Recommendations for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies using yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy: a consensus panel report from the radioembolization brachytherapy oncology consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 68:13–23.

- Kosmider S, Tan TH, Yip D, Dowling R, Lichtenstein M, Gibbs P. Radioembolization in combination with systemic chemotherapy as first-line therapy for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011; 22:780–786.

- Sato K, Lewandowski RJ, Bui JT, et al. Treatment of unresectable primary and metastatic liver cancer with yttrium-90 microspheres (TheraSphere): assessment of hepatic arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006; 29:522–529.

- Sigstedt B, Lunderquist A. Complications of angiographic examinations. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1978; 130:455–460.

- Merriweather N, Sulzbach-Hoke LM. Managing risk of complications at femoral vascular access sites in percutaneous coronary intervention. Crit Care Nurse 2012; 32:16–29.

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol 2006; 23:119–125.

- Webber GW, Jang J, Gustavson S, Olin JW. Contemporary management of postcatheterization pseudoaneurysms. Circulation 2007; 115:2666–2674.

- Abando A, Hood D, Weaver F, Katz S. The use of the Angioseal device for femoral artery closure. J Vasc Surg 2004; 40:287–290.

- Tran DD, Andersen CA. Axillary sheath hematomas causing neurologic complications following arterial access. Ann Vasc Surg 2011; 25:697.e5–697.e8.

- Hall R. Vascular injuries resulting from arterial puncture of catheterization. Br J Surg 1971; 58:513–516.

- Wigmore SJ, Redhead DN, Thomson BN, et al. Postchemoembolisation syndrome—tumour necrosis or hepatocyte injury? Br J Cancer 2003; 89:1423–1427.

- Leung DA, Goin JE, Sickles C, Raskay BJ, Soulen MC. Determinants of postembolization syndrome after hepatic chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001; 12:321–326.

- Castells A, Bruix J, Ayuso C, et al. Transarterial embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Antibiotic prophylaxis and clinical meaning of postembolization fever. J Hepatol 1995; 22:410–415.

- Hsieh PM, Hung KC, Chen YS. Tumor lysis syndrome after transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma: case reports and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15:4726–4728.

- Burney IA. Acute tumor lysis syndrome after transcatheter chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. South Med J 1998; 91:467–470.

- Sakamoto N, Monzawa S, Nagano H, Nishizaki H, Arai Y, Sugimura K. Acute tumor lysis syndrome caused by transcatheter oily chemoembolization in a patient with a large hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2007; 30:508–511.

- Cairo MS, Bishop M. Tumour lysis syndrome: new therapeutic strategies and classification. Br J Haematol 2004; 127:3–11.

- Brockow K, Christiansen C, Kanny G, et al; ENDA; EAACI interest group on drug hypersensitivity. Management of hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media. Allergy 2005; 60:150–158.

- Cochran ST. Anaphylactoid reactions to radiocontrast media. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2005; 5:28–31.

- Lasser EC, Berry CC, Talner LB, et al. Pretreatment with corticosteroids to alleviate reactions to intravenous contrast material. N Engl J Med 1987; 317:845–849.

- Greenberger PA, Halwig JM, Patterson R, Wallemark CB. Emergency administration of radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1986; 77:630–634.

- Greenberger PA, Patterson R. The prevention of immediate generalized reactions to radiocontrast media in high-risk patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1991; 87:867–872.

- Kawaoka T, Aikata H, Katamura Y, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to transcatheter chemoembolization with cisplatin and lipiodol suspension for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:1219–1225.

- Barrett BJ, Parfrey PS. Clinical practice. Preventing nephropathy induced by contrast medium. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:379–386.

- McCullough PA, Adam A, Becker CR, et al; CIN Consensus Working Panel. Risk prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy. Am J Cardiol 2006; 98:27K–36K.

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2012/. Accessed August 3, 2015.

- Cortez-Pinto H, Camilo ME. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NAFLD/NASH): diagnosis and clinical course. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 18:1089–1104.

- Llovet JM. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2004; 7:431–441.

- Sasson AR, Sigurdson ER. Surgical treatment of liver metastases. Semin Oncol 2002; 29:107–118.

- Geschwind JF, Salem R, Carr BI, et al. Yttrium-90 microspheres for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2004; 127(suppl 1):S194–S205.

- Messersmith W, Laheru D, Hidalgo M. Recent advances in the pharmacological treatment of colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2003; 12:423–434.

- Bonomo G, Pedicini V, Monfardini L, et al. Bland embolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma using precise, tightly size-calibrated, anti-inflammatory microparticles: first clinical experience and one-year follow-up. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2010; 33:552–559.

- Brown KT. Fatal pulmonary complications after arterial embolization with 40-120- micro m tris-acryl gelatin microspheres. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:197–200.

- Noguera JJ, Martínez-Cuesta A, Sangro B, Bilbao JI. Fatal pulmonary embolism after embolization of a hepatocellular carcinoma using microspheres. Radiologia 2008; 50:248–250. Spanish.

- Beland MD, Mayo-Smith WW. Image-guided tumor ablation: basic principles. In: Kaufman J, Lee MJ, eds. Vascular and Interventional Radiology: The Requisites. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2014.

- Huppert P. Current concepts in transarterial chemoembolization of hepatocellular carcinoma. Abdom Imaging 2011; 36:677–683.

- Kanaan RA, Kim JS, Kaufmann WE, Pearlson GD, Barker GJ, McGuire PK. Diffusion tensor imaging in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2005; 58:921–929.

- Brown DB, Cardella JF, Sacks D, et al. Quality improvement guidelines for transhepatic arterial chemoembolization, embolization, and chemotherapeutic infusion for hepatic malignancy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17:225–232.

- Malagari K, Chatzimichael K, Alexopoulou E, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization of unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma with drug eluting beads: results of an open-label study of 62 patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008; 31:269–280.

- Poon RT, Tso WK, Pang RW, et al. A phase I/II trial of chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel intra-arterial drug-eluting bead. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 5:1100–1108.

- Mounajjed T, Salem R, Rhee TK, et al. Multi-institutional comparison of 99mTc-MAA lung shunt fraction for transcatheter Y-90 radioembolization. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Interventional Radiology, 2005. New Orleans, LA.

- Hung JC, Redfern MG, Mahoney DW, Thorson LM, Wiseman GA. Evaluation of macroaggregated albumin particle sizes for use in pulmonary shunt patient studies. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2000; 40:46–51.

- Yip D, Allen R, Ashton C, Jain S. Radiation-induced ulceration of the stomach secondary to hepatic embolization with radioactive yttrium microspheres in the treatment of metastatic colon cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19:347–349.

- Goin J, Dancey JE, Roberts C, et al. Comparison of post-embolization syndrome in the treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: trans-catheter arterial chemo-embolization versus yttrium-90 glass microspheres. World J Nucl Med 2004; 3:49–56.

- Gaba RC, Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Safety of yttrium-90 microsphere radioembolization in patients with biliary obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010; 21:1213–1218.

- Kennedy A, Nag S, Salem R, et al. Recommendations for radioembolization of hepatic malignancies using yttrium-90 microsphere brachytherapy: a consensus panel report from the radioembolization brachytherapy oncology consortium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007; 68:13–23.