User login

Flight plan for robotic surgery credentialing: New AAGL guidelines

The AAGL, formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, has approved the first-ever set of privileging and credentialing guidelines for robotic surgery.1

Why has this prestigious minimally invasive surgery organization done that?

Maybe you’ve seen the Internet and TV ads and billboard trucks driving outside of many major medical society meetings recently, advertising “1-800-BAD-Robot.”2 You also are probably aware of recent articles in the headlines of national periodicals like the Wall Street Journal claiming that robotic surgery can be harmful.3

And yet, robotic gynecologic surgery has grown at an unprecedented rate since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2005. Recent data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicate that robot-assisted hysterectomies have increased at a dramatic rate.4 In a recent study of the FDA’s MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) database, investigators found that more than 30% of injuries during robotic surgery are related to operator error or robot failure, but the majority of problems are not associated with the technology.5

In this article, I use the aviation industry as an example of a sector that has gotten safety right. By emulating many of its standards, our specialty can make great strides toward patient safety and improved outcomes. I also outline the main points of the new AAGL guidelines and the rationale behind them.1 See, for example, the summary box on page 46.

A “shining example”

The robot clearly is an enabling technology. With its high-definition 3D vision and scaled motion with wristed instruments, surgeons are more comfortable performing many complex gynecologic procedures that previously would have required open surgery to safely accomplish … but the da Vinci Robot does not make a poor surgeon a great surgeon.

Hospitals now are being sued for allowing surgeons to perform robotic surgery on patients without documenting adequate surgeon training or providing consistent oversight.6 This new technology has outpaced the ability of hospital medical staffs to establish practice guidelines and rules to ensure patient safety.

The aviation industry is a shining example of a highly reliable industry. Each day, thousands of commercial aircraft fly all over the world with amazing safety. Most of the time, the pilot and copilot have never flown together. However, each crew member knows his or her role precisely and clearly understands what is expected. Crew members must meet standards that transcend all airlines and all aircraft.7 They all practice communication and undergo standardized training, including simulation, prior to taking off with live passengers on board.

In addition, all pilots must demonstrate their proficiency and competence on a regular basis—by exhibiting actual safe flight performance (over multiple takeoffs and landings) and undergoing check rides with flight examiners and practicing routine and emergency procedures on flight simulators. Airline passengers have come to expect that all pilots are equally proficient and safe. Shouldn’t patients be able to expect the same from their surgeons and hospitals? And yet there is no national or local organization that ensures that all surgeons are equally safe in the operating room. That responsibility is too often left up to the courts.

Three requirements of robotic credentialing

In 2008, the MultiCare Health System in the Pacific Northwest adopted a unique system of robotic credentialing that was based on the aviation model.8 This model has three main components, which are identical to the guidelines imposed on pilots:

- Surgeons selected for training should be likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

- Practice makes perfect. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills. The aviation world calls this concept “currency.”

- Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Adoption of these tried-and-true safety principles would ensure that hospitals exercise their responsibility to protect patients who undergo robotic surgeries in their systems.

The AAGL’s Robotics Special Interest Group, formed in 2010, is now the largest special interest group in the organization. The group was initially tasked to develop evidence-based guidelines for robotic surgery training and credentialing. Using the aviation industry’s model, the group developed a basic template of robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines that can be used anywhere in the world. This proposal is not meant to be a standard-of-care definition; rather, it is intended simply as a starting point.

Key components of new AAGL robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines1

Initial training

- Train only surgeons who have an adequate case volume to get through the learning curve. Recommended: at least 20 major cases per year.

- Current training pathways include computer-based learning, case observations, pig labs, simulation, and proctored cases. More intense validated simulation training could replace pig labs.

- Surgeons should initially perform only simple, basic procedures with surgeon first-assists until they develop the necessary skills to safely operate the robotic console and start performing more complex cases.

Annual currency

- Surgeons should perform at least 20 major cases per year, with at least one case every 8 weeks.

- If surgeons operate less frequently, proficiency should be verified on a simulator before operation on a live patient.

Annual recertification

- All surgeons should demonstrate competency annually on a simulator, regardless of case volume.

Initial training involves a long learning curve

There is a long learning curve for surgeons to become competent in robotic surgery. In initial studies of experienced advanced laparoscopic surgeons, investigators found that learning curves could involve 50 cases or more.9,10 In a recent study of gynecologic oncologists and urogynecologists at the Mayo Clinic, researchers found that it took 91 cases for experienced surgeons to become proficient on the robot.11

ObGyns in the United States are doing fewer hysterectomies than they used to.12 Many surgeons now perform fewer than 10 hysterectomies per year. These surgeons clearly have worse outcomes than surgeons who operate more frequently.13–15 Therefore, these new guidelines suggest that hospitals should choose to train only surgeons who have a case volume that will allow them to get through their learning curve in a short time and continue to have enough surgeries to maintain their skills. These guidelines recommend that surgeons who are candidates for robotic surgery training already perform a minimum of 20 major gynecologic operations per year.

It is important to learn to walk before you run. New student pilots start out with single-engine propeller planes before graduating to multi-engine props, jets, and commercial aircraft. Similarly, new medical students start out with easy surgical tasks before training for more complex procedures. This approach seems like common sense, although many surgeons may feel that, after orienting on the robot, they can start doing complex cases right away, as the robot enables them to do better and more precise surgery. Nothing could be further from the truth.

It is very important that new robotic surgeons start with easy, basic cases to completely familiarize themselves with the operation of the robot console before attempting more complex and difficult cases.

There is no absolute number of cases that ensures competency with the robot; the number depends on the surgeon’s case load, surgical prowess, and psychomotor skills. A surgeon should be restricted to simple cases initially, and should have an experienced robot-credentialed surgeon operating with him or her during this initial learning period.

Practice makes perfect

Musicians will tell you that the more often you practice, the more skilled you become. This is true for anyone whose job requires special training. It would be naïve to assume that surgeons can maintain optimal skills for robotic surgery by performing only a few cases each year.

Psychomotor skill degradation has been explored in relation to various surgical skills. The more complex the skill, the more likely that skill set will deteriorate without use. In recent studies, investigators have shown that robotic surgery skills begin to decline significantly after only 2 weeks of inactivity, and that skills continue to degrade without use.16,17

Based on this information, the currency requirement for surgeons to maintain privileges was set at 20 cases per year—fewer than two cases per month. Although the members of the Robotics Special Interest Group strongly agree that

maintenance of privileges should not be based entirely on an arbitrary currency number, as Tracy and colleagues also argue in a recent publication,18 it is clear that frequent performance of robotic surgery by high-volume surgeons clearly is more efficient and safer, with lower total operative times and complication rates, than robotic surgery performed by lower-volume surgeons.8

Currency is a well-accepted safety standard in aviation, and pilots know the importance of frequent practice and repetition in the cockpit under real-world conditions.

Ensure annual competency

Although a pilot must accomplish a minimum number of flying hours each year to maintain certification, this does not ensure that passengers will be safe. Pilots also must prove their competence by undergoing periodic check rides and demonstrating their skills on flight simulators.

Surgeons also can use these models to verify competency. Proctors who are independently certified by the FDA or another government agency as examiners could observe and evaluate surgeons performing robotic surgery using standardized checklists and grading forms. If done locally, care must be taken to assure standardization, as local hospital politics could interfere.

The only other methods currently available to verify surgeon competency are to demonstrate proficiency on simulation and to review outcomes data, looking for outliers in important areas such as complications, robotic console times, total operative times, length of stay, etc.

Simulation offers a standardized, independent method to monitor competency.19 A passing test score on a robotic simulator exercise could be a way for a surgeon to prove his or her competency. Basic robotic skills such as camera control and clutching, energy use, and sewing and needle control can be practiced on a robotic simulator.

Virtual cases such as hysterectomy and myomectomy are not yet available on the simulator, nor are cases involving typical complications. These are being developed, however, and will be available shortly.

Several gynecologic resident and fellowship training programs are using simulation to train novice surgeons, and some community hospitals are using simulation as an annual requirement for all practicing surgeons to demonstrate proficiency, similar to pilots.8 Some newer validated training protocols require a surgeon to demonstrate mastery of a particular robotic skill by achieving passing scores at least five times, with at least two consecutive passing scores.20,21

As simulators evolve, they will continue to be incorporated into training, used for surgeon warm-up before surgery, as refreshers for surgeons after a period of robotic inactivity, and for annual recertification.

When robotic surgery leads to legal trouble

A recent medical malpractice case highlights the importance of having guidelines in place to protect patients. In Bremerton, Washington, in 2008,1 a urologist performed his first nonproctored robotic prostatectomy. The challenging and difficult procedure took more than 13 hours; he converted to an open procedure after 7 hours. The patient developed significant postoperative complications and died.1

In the litigation that followed, the surgeon was sued for negligence and for failing to disclose that this was his first solo robot-assisted surgery. The surgeon settled, as did the hospital, which was sued for not supervising the surgeon and failing to ensure that he could use the robot safely. The family also sued Intuitive Surgical, the manufacturer of the da Vinci Robot, for failing to provide adequate training to the surgeon.2

The jury ruled in favor of the manufacturer, stating that the verification of adequate surgeon training was the responsibility of the hospital and specialty medical societies, not the industry.

References

- Estate of Fred Taylor v. Intuitive Surgical Inc., 09-2-03136-5, Superior Court, State of Washington, Kitsap County (Port Orchard).

- Ostrom C. Failed robotic surgery focus of Kitsap trial. Seattle Times. http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2020918732_robottrialxml.html Published May 3, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

A word to the wise

If hospital departments really want to ensure that they are doing all that they can to make robotic surgeries safe for their patients, they will utilize the recent guidelines approved by AAGL. In order for these guidelines to work, hospital systems need to commit resources for medical staff oversight, including a robotics peer-review committee with a physician chairman and adequate medical staff support to monitor physicians and manage those who cannot meet these goals.

There clearly will be push-back from surgeons who feel that it is unfair to restrict their ability to perform surgery just because their volumes are low or they can’t master the simulation exercises. However, in the final analysis, would we want the airlines to employ pilots who fly only a couple of times a year or who can’t master the required simulation skills to safely operate a commercial passenger jet?

The important question is, what is our focus? Is it to be “fair” to all surgeons, or is it to provide the best and safest outcomes for our patients? As surgeons, we each need to remember the oath we took when we became physicians to “First, do no harm.” By following these new AAGL robotic surgery guidelines, we will reassure our patients that we, as physicians, do take that oath seriously.

INSTANT POLL

For credentialing and privileging of robotic gynecologic surgery, do you agree that the following points are essential components of the process?

1. Surgeons should be selected for training who are most likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

2. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills.

3. Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Answer:

a. Yes, I agree.

b. No, I believe this approach is too restrictive.

c. No, I believe this approach is not restrictive enough.

To vote, please visit obgmanagement.com and look for “Quick Poll” on the right side of the homepage.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Guidelines for privileging for robotic-assisted gynecologic laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):157–167.

2. Becnel Law Firm LLC. Bad Robot Surgery. http://badrobotsurgery.com. Accessed October 10, 2014.

3. Burton TM. Report raises concern on robotic surgery device. Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304672404579186190568061568 Published November 8, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Rosero E, Kho K, Joshi G, Giesecke M, Schaffer J. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):778–786.

5. Fuchs Weizman N, Cohen S, Manoucheri E, Wang K, Einarsson J. Surgical errors associated with robotic surgery in gynecology: a review of the FDA MAUDE database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):S171.

6. Lee YL, Kilic G, Phelps J. Medicolegal review of liability risks for gynecologists stemming from lack of training in robotic assisted surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(4):512–515.

7. Federal Aviation Administration. Pilot Regulations. http://www.faa.gov/pilots/regs/. Updated March 20, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

8. Lenihan JP. Navigating credentialing, privileging, and learning curves in robotics with an evidence- and experience-based approach. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(3):382–390.

9. Lenihan J, Kovanda C, Kreaden U. What is the learning curve for robotic Gyn surgery? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(5):589–594.

10. Payne T, Dauterive F. A comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy to robotically assisted hysterectomy: surgical outcomes in a community practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):286–291.

11. Woelk J, Casiano E, Weaver A, Gostout B, Trabuco E, Gebhart A. The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):87–96.

12. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

13. Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):909–915.

14. Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effects of surgical volumes on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):710–716.

15. Doll K, Milad M, Gossett D. Surgeon volume and outcomes in benign hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):554–561.

16. Jenison E, Gil K, Lendvay T, Guy M. Robotic surgical skills: acquisition, maintenance and degradation. JSLS. 2012;16(2):218–228.

17. Guseila L, Jenison E. Maintaining robotic surgical skills during periods of robotic inactivity. J Robotic Surg. 2014;8(3):261–268.

18. Tracy E, Zephyrin L, Rosman D, Berkowitz L. Credentialing based on surgical volume. Physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):947–951.

19. Brand T. Madigan Protocol – Si Version. Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=17. Accessed October 10, 2014.

20. Culligan P, Salamon C. Validation of a robotic simulator: transferring simulator skills to the operating room. Validation of a robotic surgery simulator protocol—transfer of simulator skills to the operating room. Fem Pelvic Med Recon Surg. 2014;20(1):48–51.

21. Culligan P. Morristown Protocol (Morristown Memorial Hospital). Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=11. Accessed October 10, 2014.

The AAGL, formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, has approved the first-ever set of privileging and credentialing guidelines for robotic surgery.1

Why has this prestigious minimally invasive surgery organization done that?

Maybe you’ve seen the Internet and TV ads and billboard trucks driving outside of many major medical society meetings recently, advertising “1-800-BAD-Robot.”2 You also are probably aware of recent articles in the headlines of national periodicals like the Wall Street Journal claiming that robotic surgery can be harmful.3

And yet, robotic gynecologic surgery has grown at an unprecedented rate since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2005. Recent data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicate that robot-assisted hysterectomies have increased at a dramatic rate.4 In a recent study of the FDA’s MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) database, investigators found that more than 30% of injuries during robotic surgery are related to operator error or robot failure, but the majority of problems are not associated with the technology.5

In this article, I use the aviation industry as an example of a sector that has gotten safety right. By emulating many of its standards, our specialty can make great strides toward patient safety and improved outcomes. I also outline the main points of the new AAGL guidelines and the rationale behind them.1 See, for example, the summary box on page 46.

A “shining example”

The robot clearly is an enabling technology. With its high-definition 3D vision and scaled motion with wristed instruments, surgeons are more comfortable performing many complex gynecologic procedures that previously would have required open surgery to safely accomplish … but the da Vinci Robot does not make a poor surgeon a great surgeon.

Hospitals now are being sued for allowing surgeons to perform robotic surgery on patients without documenting adequate surgeon training or providing consistent oversight.6 This new technology has outpaced the ability of hospital medical staffs to establish practice guidelines and rules to ensure patient safety.

The aviation industry is a shining example of a highly reliable industry. Each day, thousands of commercial aircraft fly all over the world with amazing safety. Most of the time, the pilot and copilot have never flown together. However, each crew member knows his or her role precisely and clearly understands what is expected. Crew members must meet standards that transcend all airlines and all aircraft.7 They all practice communication and undergo standardized training, including simulation, prior to taking off with live passengers on board.

In addition, all pilots must demonstrate their proficiency and competence on a regular basis—by exhibiting actual safe flight performance (over multiple takeoffs and landings) and undergoing check rides with flight examiners and practicing routine and emergency procedures on flight simulators. Airline passengers have come to expect that all pilots are equally proficient and safe. Shouldn’t patients be able to expect the same from their surgeons and hospitals? And yet there is no national or local organization that ensures that all surgeons are equally safe in the operating room. That responsibility is too often left up to the courts.

Three requirements of robotic credentialing

In 2008, the MultiCare Health System in the Pacific Northwest adopted a unique system of robotic credentialing that was based on the aviation model.8 This model has three main components, which are identical to the guidelines imposed on pilots:

- Surgeons selected for training should be likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

- Practice makes perfect. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills. The aviation world calls this concept “currency.”

- Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Adoption of these tried-and-true safety principles would ensure that hospitals exercise their responsibility to protect patients who undergo robotic surgeries in their systems.

The AAGL’s Robotics Special Interest Group, formed in 2010, is now the largest special interest group in the organization. The group was initially tasked to develop evidence-based guidelines for robotic surgery training and credentialing. Using the aviation industry’s model, the group developed a basic template of robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines that can be used anywhere in the world. This proposal is not meant to be a standard-of-care definition; rather, it is intended simply as a starting point.

Key components of new AAGL robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines1

Initial training

- Train only surgeons who have an adequate case volume to get through the learning curve. Recommended: at least 20 major cases per year.

- Current training pathways include computer-based learning, case observations, pig labs, simulation, and proctored cases. More intense validated simulation training could replace pig labs.

- Surgeons should initially perform only simple, basic procedures with surgeon first-assists until they develop the necessary skills to safely operate the robotic console and start performing more complex cases.

Annual currency

- Surgeons should perform at least 20 major cases per year, with at least one case every 8 weeks.

- If surgeons operate less frequently, proficiency should be verified on a simulator before operation on a live patient.

Annual recertification

- All surgeons should demonstrate competency annually on a simulator, regardless of case volume.

Initial training involves a long learning curve

There is a long learning curve for surgeons to become competent in robotic surgery. In initial studies of experienced advanced laparoscopic surgeons, investigators found that learning curves could involve 50 cases or more.9,10 In a recent study of gynecologic oncologists and urogynecologists at the Mayo Clinic, researchers found that it took 91 cases for experienced surgeons to become proficient on the robot.11

ObGyns in the United States are doing fewer hysterectomies than they used to.12 Many surgeons now perform fewer than 10 hysterectomies per year. These surgeons clearly have worse outcomes than surgeons who operate more frequently.13–15 Therefore, these new guidelines suggest that hospitals should choose to train only surgeons who have a case volume that will allow them to get through their learning curve in a short time and continue to have enough surgeries to maintain their skills. These guidelines recommend that surgeons who are candidates for robotic surgery training already perform a minimum of 20 major gynecologic operations per year.

It is important to learn to walk before you run. New student pilots start out with single-engine propeller planes before graduating to multi-engine props, jets, and commercial aircraft. Similarly, new medical students start out with easy surgical tasks before training for more complex procedures. This approach seems like common sense, although many surgeons may feel that, after orienting on the robot, they can start doing complex cases right away, as the robot enables them to do better and more precise surgery. Nothing could be further from the truth.

It is very important that new robotic surgeons start with easy, basic cases to completely familiarize themselves with the operation of the robot console before attempting more complex and difficult cases.

There is no absolute number of cases that ensures competency with the robot; the number depends on the surgeon’s case load, surgical prowess, and psychomotor skills. A surgeon should be restricted to simple cases initially, and should have an experienced robot-credentialed surgeon operating with him or her during this initial learning period.

Practice makes perfect

Musicians will tell you that the more often you practice, the more skilled you become. This is true for anyone whose job requires special training. It would be naïve to assume that surgeons can maintain optimal skills for robotic surgery by performing only a few cases each year.

Psychomotor skill degradation has been explored in relation to various surgical skills. The more complex the skill, the more likely that skill set will deteriorate without use. In recent studies, investigators have shown that robotic surgery skills begin to decline significantly after only 2 weeks of inactivity, and that skills continue to degrade without use.16,17

Based on this information, the currency requirement for surgeons to maintain privileges was set at 20 cases per year—fewer than two cases per month. Although the members of the Robotics Special Interest Group strongly agree that

maintenance of privileges should not be based entirely on an arbitrary currency number, as Tracy and colleagues also argue in a recent publication,18 it is clear that frequent performance of robotic surgery by high-volume surgeons clearly is more efficient and safer, with lower total operative times and complication rates, than robotic surgery performed by lower-volume surgeons.8

Currency is a well-accepted safety standard in aviation, and pilots know the importance of frequent practice and repetition in the cockpit under real-world conditions.

Ensure annual competency

Although a pilot must accomplish a minimum number of flying hours each year to maintain certification, this does not ensure that passengers will be safe. Pilots also must prove their competence by undergoing periodic check rides and demonstrating their skills on flight simulators.

Surgeons also can use these models to verify competency. Proctors who are independently certified by the FDA or another government agency as examiners could observe and evaluate surgeons performing robotic surgery using standardized checklists and grading forms. If done locally, care must be taken to assure standardization, as local hospital politics could interfere.

The only other methods currently available to verify surgeon competency are to demonstrate proficiency on simulation and to review outcomes data, looking for outliers in important areas such as complications, robotic console times, total operative times, length of stay, etc.

Simulation offers a standardized, independent method to monitor competency.19 A passing test score on a robotic simulator exercise could be a way for a surgeon to prove his or her competency. Basic robotic skills such as camera control and clutching, energy use, and sewing and needle control can be practiced on a robotic simulator.

Virtual cases such as hysterectomy and myomectomy are not yet available on the simulator, nor are cases involving typical complications. These are being developed, however, and will be available shortly.

Several gynecologic resident and fellowship training programs are using simulation to train novice surgeons, and some community hospitals are using simulation as an annual requirement for all practicing surgeons to demonstrate proficiency, similar to pilots.8 Some newer validated training protocols require a surgeon to demonstrate mastery of a particular robotic skill by achieving passing scores at least five times, with at least two consecutive passing scores.20,21

As simulators evolve, they will continue to be incorporated into training, used for surgeon warm-up before surgery, as refreshers for surgeons after a period of robotic inactivity, and for annual recertification.

When robotic surgery leads to legal trouble

A recent medical malpractice case highlights the importance of having guidelines in place to protect patients. In Bremerton, Washington, in 2008,1 a urologist performed his first nonproctored robotic prostatectomy. The challenging and difficult procedure took more than 13 hours; he converted to an open procedure after 7 hours. The patient developed significant postoperative complications and died.1

In the litigation that followed, the surgeon was sued for negligence and for failing to disclose that this was his first solo robot-assisted surgery. The surgeon settled, as did the hospital, which was sued for not supervising the surgeon and failing to ensure that he could use the robot safely. The family also sued Intuitive Surgical, the manufacturer of the da Vinci Robot, for failing to provide adequate training to the surgeon.2

The jury ruled in favor of the manufacturer, stating that the verification of adequate surgeon training was the responsibility of the hospital and specialty medical societies, not the industry.

References

- Estate of Fred Taylor v. Intuitive Surgical Inc., 09-2-03136-5, Superior Court, State of Washington, Kitsap County (Port Orchard).

- Ostrom C. Failed robotic surgery focus of Kitsap trial. Seattle Times. http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2020918732_robottrialxml.html Published May 3, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

A word to the wise

If hospital departments really want to ensure that they are doing all that they can to make robotic surgeries safe for their patients, they will utilize the recent guidelines approved by AAGL. In order for these guidelines to work, hospital systems need to commit resources for medical staff oversight, including a robotics peer-review committee with a physician chairman and adequate medical staff support to monitor physicians and manage those who cannot meet these goals.

There clearly will be push-back from surgeons who feel that it is unfair to restrict their ability to perform surgery just because their volumes are low or they can’t master the simulation exercises. However, in the final analysis, would we want the airlines to employ pilots who fly only a couple of times a year or who can’t master the required simulation skills to safely operate a commercial passenger jet?

The important question is, what is our focus? Is it to be “fair” to all surgeons, or is it to provide the best and safest outcomes for our patients? As surgeons, we each need to remember the oath we took when we became physicians to “First, do no harm.” By following these new AAGL robotic surgery guidelines, we will reassure our patients that we, as physicians, do take that oath seriously.

INSTANT POLL

For credentialing and privileging of robotic gynecologic surgery, do you agree that the following points are essential components of the process?

1. Surgeons should be selected for training who are most likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

2. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills.

3. Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Answer:

a. Yes, I agree.

b. No, I believe this approach is too restrictive.

c. No, I believe this approach is not restrictive enough.

To vote, please visit obgmanagement.com and look for “Quick Poll” on the right side of the homepage.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The AAGL, formerly the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists, has approved the first-ever set of privileging and credentialing guidelines for robotic surgery.1

Why has this prestigious minimally invasive surgery organization done that?

Maybe you’ve seen the Internet and TV ads and billboard trucks driving outside of many major medical society meetings recently, advertising “1-800-BAD-Robot.”2 You also are probably aware of recent articles in the headlines of national periodicals like the Wall Street Journal claiming that robotic surgery can be harmful.3

And yet, robotic gynecologic surgery has grown at an unprecedented rate since its approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in April 2005. Recent data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicate that robot-assisted hysterectomies have increased at a dramatic rate.4 In a recent study of the FDA’s MAUDE (Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience) database, investigators found that more than 30% of injuries during robotic surgery are related to operator error or robot failure, but the majority of problems are not associated with the technology.5

In this article, I use the aviation industry as an example of a sector that has gotten safety right. By emulating many of its standards, our specialty can make great strides toward patient safety and improved outcomes. I also outline the main points of the new AAGL guidelines and the rationale behind them.1 See, for example, the summary box on page 46.

A “shining example”

The robot clearly is an enabling technology. With its high-definition 3D vision and scaled motion with wristed instruments, surgeons are more comfortable performing many complex gynecologic procedures that previously would have required open surgery to safely accomplish … but the da Vinci Robot does not make a poor surgeon a great surgeon.

Hospitals now are being sued for allowing surgeons to perform robotic surgery on patients without documenting adequate surgeon training or providing consistent oversight.6 This new technology has outpaced the ability of hospital medical staffs to establish practice guidelines and rules to ensure patient safety.

The aviation industry is a shining example of a highly reliable industry. Each day, thousands of commercial aircraft fly all over the world with amazing safety. Most of the time, the pilot and copilot have never flown together. However, each crew member knows his or her role precisely and clearly understands what is expected. Crew members must meet standards that transcend all airlines and all aircraft.7 They all practice communication and undergo standardized training, including simulation, prior to taking off with live passengers on board.

In addition, all pilots must demonstrate their proficiency and competence on a regular basis—by exhibiting actual safe flight performance (over multiple takeoffs and landings) and undergoing check rides with flight examiners and practicing routine and emergency procedures on flight simulators. Airline passengers have come to expect that all pilots are equally proficient and safe. Shouldn’t patients be able to expect the same from their surgeons and hospitals? And yet there is no national or local organization that ensures that all surgeons are equally safe in the operating room. That responsibility is too often left up to the courts.

Three requirements of robotic credentialing

In 2008, the MultiCare Health System in the Pacific Northwest adopted a unique system of robotic credentialing that was based on the aviation model.8 This model has three main components, which are identical to the guidelines imposed on pilots:

- Surgeons selected for training should be likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

- Practice makes perfect. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills. The aviation world calls this concept “currency.”

- Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Adoption of these tried-and-true safety principles would ensure that hospitals exercise their responsibility to protect patients who undergo robotic surgeries in their systems.

The AAGL’s Robotics Special Interest Group, formed in 2010, is now the largest special interest group in the organization. The group was initially tasked to develop evidence-based guidelines for robotic surgery training and credentialing. Using the aviation industry’s model, the group developed a basic template of robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines that can be used anywhere in the world. This proposal is not meant to be a standard-of-care definition; rather, it is intended simply as a starting point.

Key components of new AAGL robotic surgery credentialing and privileging guidelines1

Initial training

- Train only surgeons who have an adequate case volume to get through the learning curve. Recommended: at least 20 major cases per year.

- Current training pathways include computer-based learning, case observations, pig labs, simulation, and proctored cases. More intense validated simulation training could replace pig labs.

- Surgeons should initially perform only simple, basic procedures with surgeon first-assists until they develop the necessary skills to safely operate the robotic console and start performing more complex cases.

Annual currency

- Surgeons should perform at least 20 major cases per year, with at least one case every 8 weeks.

- If surgeons operate less frequently, proficiency should be verified on a simulator before operation on a live patient.

Annual recertification

- All surgeons should demonstrate competency annually on a simulator, regardless of case volume.

Initial training involves a long learning curve

There is a long learning curve for surgeons to become competent in robotic surgery. In initial studies of experienced advanced laparoscopic surgeons, investigators found that learning curves could involve 50 cases or more.9,10 In a recent study of gynecologic oncologists and urogynecologists at the Mayo Clinic, researchers found that it took 91 cases for experienced surgeons to become proficient on the robot.11

ObGyns in the United States are doing fewer hysterectomies than they used to.12 Many surgeons now perform fewer than 10 hysterectomies per year. These surgeons clearly have worse outcomes than surgeons who operate more frequently.13–15 Therefore, these new guidelines suggest that hospitals should choose to train only surgeons who have a case volume that will allow them to get through their learning curve in a short time and continue to have enough surgeries to maintain their skills. These guidelines recommend that surgeons who are candidates for robotic surgery training already perform a minimum of 20 major gynecologic operations per year.

It is important to learn to walk before you run. New student pilots start out with single-engine propeller planes before graduating to multi-engine props, jets, and commercial aircraft. Similarly, new medical students start out with easy surgical tasks before training for more complex procedures. This approach seems like common sense, although many surgeons may feel that, after orienting on the robot, they can start doing complex cases right away, as the robot enables them to do better and more precise surgery. Nothing could be further from the truth.

It is very important that new robotic surgeons start with easy, basic cases to completely familiarize themselves with the operation of the robot console before attempting more complex and difficult cases.

There is no absolute number of cases that ensures competency with the robot; the number depends on the surgeon’s case load, surgical prowess, and psychomotor skills. A surgeon should be restricted to simple cases initially, and should have an experienced robot-credentialed surgeon operating with him or her during this initial learning period.

Practice makes perfect

Musicians will tell you that the more often you practice, the more skilled you become. This is true for anyone whose job requires special training. It would be naïve to assume that surgeons can maintain optimal skills for robotic surgery by performing only a few cases each year.

Psychomotor skill degradation has been explored in relation to various surgical skills. The more complex the skill, the more likely that skill set will deteriorate without use. In recent studies, investigators have shown that robotic surgery skills begin to decline significantly after only 2 weeks of inactivity, and that skills continue to degrade without use.16,17

Based on this information, the currency requirement for surgeons to maintain privileges was set at 20 cases per year—fewer than two cases per month. Although the members of the Robotics Special Interest Group strongly agree that

maintenance of privileges should not be based entirely on an arbitrary currency number, as Tracy and colleagues also argue in a recent publication,18 it is clear that frequent performance of robotic surgery by high-volume surgeons clearly is more efficient and safer, with lower total operative times and complication rates, than robotic surgery performed by lower-volume surgeons.8

Currency is a well-accepted safety standard in aviation, and pilots know the importance of frequent practice and repetition in the cockpit under real-world conditions.

Ensure annual competency

Although a pilot must accomplish a minimum number of flying hours each year to maintain certification, this does not ensure that passengers will be safe. Pilots also must prove their competence by undergoing periodic check rides and demonstrating their skills on flight simulators.

Surgeons also can use these models to verify competency. Proctors who are independently certified by the FDA or another government agency as examiners could observe and evaluate surgeons performing robotic surgery using standardized checklists and grading forms. If done locally, care must be taken to assure standardization, as local hospital politics could interfere.

The only other methods currently available to verify surgeon competency are to demonstrate proficiency on simulation and to review outcomes data, looking for outliers in important areas such as complications, robotic console times, total operative times, length of stay, etc.

Simulation offers a standardized, independent method to monitor competency.19 A passing test score on a robotic simulator exercise could be a way for a surgeon to prove his or her competency. Basic robotic skills such as camera control and clutching, energy use, and sewing and needle control can be practiced on a robotic simulator.

Virtual cases such as hysterectomy and myomectomy are not yet available on the simulator, nor are cases involving typical complications. These are being developed, however, and will be available shortly.

Several gynecologic resident and fellowship training programs are using simulation to train novice surgeons, and some community hospitals are using simulation as an annual requirement for all practicing surgeons to demonstrate proficiency, similar to pilots.8 Some newer validated training protocols require a surgeon to demonstrate mastery of a particular robotic skill by achieving passing scores at least five times, with at least two consecutive passing scores.20,21

As simulators evolve, they will continue to be incorporated into training, used for surgeon warm-up before surgery, as refreshers for surgeons after a period of robotic inactivity, and for annual recertification.

When robotic surgery leads to legal trouble

A recent medical malpractice case highlights the importance of having guidelines in place to protect patients. In Bremerton, Washington, in 2008,1 a urologist performed his first nonproctored robotic prostatectomy. The challenging and difficult procedure took more than 13 hours; he converted to an open procedure after 7 hours. The patient developed significant postoperative complications and died.1

In the litigation that followed, the surgeon was sued for negligence and for failing to disclose that this was his first solo robot-assisted surgery. The surgeon settled, as did the hospital, which was sued for not supervising the surgeon and failing to ensure that he could use the robot safely. The family also sued Intuitive Surgical, the manufacturer of the da Vinci Robot, for failing to provide adequate training to the surgeon.2

The jury ruled in favor of the manufacturer, stating that the verification of adequate surgeon training was the responsibility of the hospital and specialty medical societies, not the industry.

References

- Estate of Fred Taylor v. Intuitive Surgical Inc., 09-2-03136-5, Superior Court, State of Washington, Kitsap County (Port Orchard).

- Ostrom C. Failed robotic surgery focus of Kitsap trial. Seattle Times. http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2020918732_robottrialxml.html Published May 3, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

A word to the wise

If hospital departments really want to ensure that they are doing all that they can to make robotic surgeries safe for their patients, they will utilize the recent guidelines approved by AAGL. In order for these guidelines to work, hospital systems need to commit resources for medical staff oversight, including a robotics peer-review committee with a physician chairman and adequate medical staff support to monitor physicians and manage those who cannot meet these goals.

There clearly will be push-back from surgeons who feel that it is unfair to restrict their ability to perform surgery just because their volumes are low or they can’t master the simulation exercises. However, in the final analysis, would we want the airlines to employ pilots who fly only a couple of times a year or who can’t master the required simulation skills to safely operate a commercial passenger jet?

The important question is, what is our focus? Is it to be “fair” to all surgeons, or is it to provide the best and safest outcomes for our patients? As surgeons, we each need to remember the oath we took when we became physicians to “First, do no harm.” By following these new AAGL robotic surgery guidelines, we will reassure our patients that we, as physicians, do take that oath seriously.

INSTANT POLL

For credentialing and privileging of robotic gynecologic surgery, do you agree that the following points are essential components of the process?

1. Surgeons should be selected for training who are most likely to be successful in performing robotic surgeries safely and efficiently.

2. There should be a minimum number of procedures performed on a regular basis to ensure that the surgeon maintains his or her psychomotor (hand-eye coordination) skills.

3. Surgeons, like pilots, should be required to demonstrate their competency in operating the robot on a regular basis.

Answer:

a. Yes, I agree.

b. No, I believe this approach is too restrictive.

c. No, I believe this approach is not restrictive enough.

To vote, please visit obgmanagement.com and look for “Quick Poll” on the right side of the homepage.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Guidelines for privileging for robotic-assisted gynecologic laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):157–167.

2. Becnel Law Firm LLC. Bad Robot Surgery. http://badrobotsurgery.com. Accessed October 10, 2014.

3. Burton TM. Report raises concern on robotic surgery device. Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304672404579186190568061568 Published November 8, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Rosero E, Kho K, Joshi G, Giesecke M, Schaffer J. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):778–786.

5. Fuchs Weizman N, Cohen S, Manoucheri E, Wang K, Einarsson J. Surgical errors associated with robotic surgery in gynecology: a review of the FDA MAUDE database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):S171.

6. Lee YL, Kilic G, Phelps J. Medicolegal review of liability risks for gynecologists stemming from lack of training in robotic assisted surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(4):512–515.

7. Federal Aviation Administration. Pilot Regulations. http://www.faa.gov/pilots/regs/. Updated March 20, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

8. Lenihan JP. Navigating credentialing, privileging, and learning curves in robotics with an evidence- and experience-based approach. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(3):382–390.

9. Lenihan J, Kovanda C, Kreaden U. What is the learning curve for robotic Gyn surgery? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(5):589–594.

10. Payne T, Dauterive F. A comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy to robotically assisted hysterectomy: surgical outcomes in a community practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):286–291.

11. Woelk J, Casiano E, Weaver A, Gostout B, Trabuco E, Gebhart A. The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):87–96.

12. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

13. Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):909–915.

14. Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effects of surgical volumes on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):710–716.

15. Doll K, Milad M, Gossett D. Surgeon volume and outcomes in benign hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):554–561.

16. Jenison E, Gil K, Lendvay T, Guy M. Robotic surgical skills: acquisition, maintenance and degradation. JSLS. 2012;16(2):218–228.

17. Guseila L, Jenison E. Maintaining robotic surgical skills during periods of robotic inactivity. J Robotic Surg. 2014;8(3):261–268.

18. Tracy E, Zephyrin L, Rosman D, Berkowitz L. Credentialing based on surgical volume. Physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):947–951.

19. Brand T. Madigan Protocol – Si Version. Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=17. Accessed October 10, 2014.

20. Culligan P, Salamon C. Validation of a robotic simulator: transferring simulator skills to the operating room. Validation of a robotic surgery simulator protocol—transfer of simulator skills to the operating room. Fem Pelvic Med Recon Surg. 2014;20(1):48–51.

21. Culligan P. Morristown Protocol (Morristown Memorial Hospital). Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=11. Accessed October 10, 2014.

1. Guidelines for privileging for robotic-assisted gynecologic laparoscopy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(2):157–167.

2. Becnel Law Firm LLC. Bad Robot Surgery. http://badrobotsurgery.com. Accessed October 10, 2014.

3. Burton TM. Report raises concern on robotic surgery device. Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304672404579186190568061568 Published November 8, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

4. Rosero E, Kho K, Joshi G, Giesecke M, Schaffer J. Comparison of robotic and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(4):778–786.

5. Fuchs Weizman N, Cohen S, Manoucheri E, Wang K, Einarsson J. Surgical errors associated with robotic surgery in gynecology: a review of the FDA MAUDE database. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(6):S171.

6. Lee YL, Kilic G, Phelps J. Medicolegal review of liability risks for gynecologists stemming from lack of training in robotic assisted surgery. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(4):512–515.

7. Federal Aviation Administration. Pilot Regulations. http://www.faa.gov/pilots/regs/. Updated March 20, 2013. Accessed October 10, 2014.

8. Lenihan JP. Navigating credentialing, privileging, and learning curves in robotics with an evidence- and experience-based approach. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;54(3):382–390.

9. Lenihan J, Kovanda C, Kreaden U. What is the learning curve for robotic Gyn surgery? J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(5):589–594.

10. Payne T, Dauterive F. A comparison of total laparoscopic hysterectomy to robotically assisted hysterectomy: surgical outcomes in a community practice. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(3):286–291.

11. Woelk J, Casiano E, Weaver A, Gostout B, Trabuco E, Gebhart A. The learning curve of robotic hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(1):87–96.

12. Wright JD, Herzog TJ, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2 pt 1):233–241.

13. Boyd LR, Novetsky AP, Curtin JP. Effect of surgical volume on route of hysterectomy and short-term morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(4):909–915.

14. Wallenstein MR, Ananth CV, Kim JH, et al. Effects of surgical volumes on outcomes for laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign conditions. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):710–716.

15. Doll K, Milad M, Gossett D. Surgeon volume and outcomes in benign hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(5):554–561.

16. Jenison E, Gil K, Lendvay T, Guy M. Robotic surgical skills: acquisition, maintenance and degradation. JSLS. 2012;16(2):218–228.

17. Guseila L, Jenison E. Maintaining robotic surgical skills during periods of robotic inactivity. J Robotic Surg. 2014;8(3):261–268.

18. Tracy E, Zephyrin L, Rosman D, Berkowitz L. Credentialing based on surgical volume. Physician workforce challenges, and patient access. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(5):947–951.

19. Brand T. Madigan Protocol – Si Version. Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=17. Accessed October 10, 2014.

20. Culligan P, Salamon C. Validation of a robotic simulator: transferring simulator skills to the operating room. Validation of a robotic surgery simulator protocol—transfer of simulator skills to the operating room. Fem Pelvic Med Recon Surg. 2014;20(1):48–51.

21. Culligan P. Morristown Protocol (Morristown Memorial Hospital). Mimic Technologies Web site. http://www.mimicsimulation.com/training/mshare/curriculum/?id=11. Accessed October 10, 2014.

Optimal obstetric care for women aged 40 and older

CASE: Preterm labor in an older woman

G.S. is a 41-year-old G1P0 with a several-year history of infertility and a medical history of chronic hypertension. She undergoes in vitro fertilization (IVF) using her own oocytes, with transfer of two embryos. Early ultrasonography (US) confirms a diamniotic/dichorionic twin gestation. She undergoes chorionic villus sampling (CVS) during the first trimester, with normal fetal karyotypes noted.

For her chronic hypertension, the patient is treated with oral labetalol 200 mg twice daily, beginning in the first trimester. Results of a baseline comprehensive metabolic profile and complete blood count, and electrocardiogram are normal. Baseline 24-hour urine study results reveal no significant proteinuria and a normal creatinine clearance.

At 18 weeks’ gestation, US results show normal growth and amniotic fluid volume for each fetus, with no anomalies detected. Because of a gradual increase in the patient’s blood pressure, her labetalol dose is increased to 400 mg orally thrice daily. Her urine protein output remains negative on dipstick, and US every 4 weeks until 28 weeks’ gestation continues to show normal fetal growth and amniotic fluid volume.

At 33 weeks’ gestation, the patient presents with regular uterine activity. Nonstress tests for both fetuses are reactive. She is given a 1-L intravenous (IV) fluid bolus of lactated Ringers solution, as well as subcutaneous terbutaline sulfate every 15 minutes for four doses, without resolution of the uterine contractions. Her pulse has increased to 120 bpm.

How do you manage this patient’s care?

Nine times as many women aged 35 and older gave birth to their first child in 2012 than did women of the same age 40 years ago, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Health Statistics.1 The rate of first births for women aged 40 to 44 remained essentially stable during the 1970s and early 1980s but increased more than fourfold from 1985 through 2012—from 0.5 to 2.3 per 1,000 women.1 Clearly, more women are delaying childbearing to a later age by personal choice for reasons such as completion of education and career advancement.2

The path to late motherhood is not without thorns, however. Heightened risks associated with increasing maternal age include:

- fetal aneuploidy

- fetal malformation

- gestational diabetes

- chronic and gestational hypertension

- antepartum hemorrhage

- placenta previa

- prelabor rupture of membranes

- preterm labor.3,4

Women with advanced age at conception also are more likely to have a multifetal gestation because of the need for assisted reproduction and are more likely to require cesarean delivery5 as a result of abnormal placentation, fetal malpresentation, an abnormal pattern of labor, or increased use of oxytocin in labor. In addition, they are more likely to experience rupture of the sphincter, postpartum hemorrhage, and thromboembolism.3 Advanced maternal age also is associated with a higher risk of stillbirth throughout gestation, with the peak risk period reported to occur at 37 to 41 weeks.6

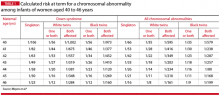

Maternal age-related risks of autosomal trisomies (especially Down syndrome) are well understood and have been quantified for singleton and twin gestations. TABLE 1 shows the risks at term for singleton and twin gestations for at least one chromosomally abnormal fetus by maternal age (40–46 years) and race.7

Preconception considerations

Aging and fertility

These combined result of aging of the ovary and uterus and an escalating risk of underlying medical comorbidities has a detrimental effect on fertility.8 Although assisted reproductive technologies are helpful, they cannot guarantee a live birth or completely compensate for an age-related decline in fertility.9

Many IVF programs refuse infertility treatment to women over age 43 or 44 who want to use their own oocytes. The reason: low pregnancy rates. The use of donor oocytes, however, increases the risks of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. And if assisted reproductive technologies are needed, the risk for multifetal pregnancy increases.

Women of advanced maternal age are likely to have an older spouse or partner. There is no clearly accepted definition of advanced paternal age, but it is most often defined as an age of 40 years or older at the time of conception. Advanced paternal age has been associated with a higher risk for autism spectrum disorder and schizophrenia, as well as mutations in the FGFR2 and FGFR3 genes that result in skeletal dysplasias and craniosynostosis syndromes.10

Medical conditions are more common

Women of advanced maternal age have an increased rate of such prepregnancy chronic medical complications as diabetes, chronic hypertension, obesity, and renal and cardiac disease. Therefore, it is best to optimize control of these chronic illnesses prior to conception to minimize the risks of miscarriage, fetal anomalies, and gestational hypertension and preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia. Although daily low-dose (60–81 mg) aspirin has been used to reduce the risk of preeclampsia, current recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) suggest that this therapy be reserved for women with a medical history of early-onset preeclampsia or those who have had preeclampsia in more than one pregnancy.11

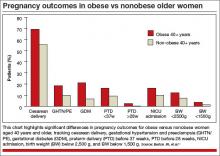

Impact of obesity. We recently examined the influence of age and obesity on pregnancy outcomes of nulliparous women aged 40 or older at delivery.12 The study included women aged 20 to 29 years (n = 52,249) and 40 or older (n = 1,231) who delivered singleton infants. Women who reported medical disorders, tobacco use, or conception with assisted reproductive technology were excluded.

In the older age group (≥40 years), obese women had significantly higher rates of cesarean delivery, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, preterm delivery before 37 weeks’ gestation, and preterm delivery before 28 weeks, and their infants had higher rates of admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), compared with nonobese women (FIGURE).

It would appear, however, that healthy, obese women who delay pregnancy until the age of 40 or later may modify their risk for cesarean delivery, gestational diabetes mellitus, and gestational hypertension and preeclampsia by reducing their body mass index to nonobese levels prior to conception.

In addition to maternal risks for women of advanced maternal age, there are risks to the fetus and neonate, as well as a risk of placental abnormalities. These risks are summarized in TABLE 2.

Placental

- Molar or partial molar pregnancy

- Fetus or twins with a complete mole

- Placenta previa, vasa previa

Fetal/neonatal

- Aneuploidy

- Selective fetal growth restriction in twin gestation

- Twin-twin transfusion syndrome

- Preterm birth

- Perinatal death

Antepartum

- Gestational diabetes

- Insulin-dependent diabetes

- Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia

- Cholestasis of pregnancy

- Acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- Venous thromboembolism

- Preterm labor, preterm premature rupture

of membranes

Intrapartum

- Dysfunctional labor

- Malpresentation

- Cesarean delivery

Postpartum

- Venous thromboembolism

- Postpartum hemorrhage

Folic acid supplementation can reduce some risks

The potential benefit of folic acid supplementation to reduce the risk of fetal open neural tube defects is well documented. More recent data suggest that folic acid also is associated with a reduction in the risks of congenital heart defects, abdominal wall defects, cleft lip and palate, and spontaneous abortion. Supplementation should be initiated at least 3 months prior to conception and continued through the first trimester.

The first trimester

Early pregnancy loss is a risk

Women of advanced maternal age are more likely than younger women to experience early pregnancy loss. This risk is due to higher rates of fetal aneuploidy as well as declining ovarian and uterine function and a higher rate of ectopic pregnancy.

In the First and Second Trimester Evaluation of Risk (FASTER) trial, in which investigators reported pregnancy outcomes by maternal age for 36,056 pregnancies, the rate of spontaneous abortion after 10 weeks of gestation was 0.8% among women younger than 35 years, compared with 2.2% for women aged 40 or older.4

The likelihood of multiple gestation increases

The background risk of multiple births is higher in women of advanced maternal age, compared with younger women. This risk increases further with fertility treatment.

Multiple gestations at any age are associated with increased risks for preterm birth and very-low–birthweight infants. Potential maternal risks are listed in TABLE 3.

- Hypertension (2.5 times the risk of a singleton gestation)

- Abruption (3.0 times the risk)

- Anemia (2.5 times the risk)

- Urinary tract infection (1.5 times the risk)

- Preeclampsia (risk of 26%–75%) (occurs at earlier gestation) — HELLP syndrome (risk of 9%)

- Abruption (20%) (10 times the risk of a singleton gestation)

- Anemia (24%)

- Preterm premature rupture of membranes (24%)

- Gestational diabetes (14%)

- Acute fatty liver (4%) (1 in 10,000 singletons)

- Postpartum hemorrhage (9%)

To reduce the number of multiple gestations with assisted reproduction, consider elective single embryo transfer, especially if the mother has significant underlying medical complications.

Multiple gestations present difficult management issues in older women. Strategies shown to prevent preterm delivery in singleton gestations, including weekly 17-hydroxyprogesterone injections and cervical cerclage, are not effective in multiple gestations. Moreover, many of these therapies—including bed rest—increase the risk of thromboembolic events in multiple gestations, particularly when the mother is of advanced age.

Maternal adaptations in multiple gestations also may be poorly tolerated by older patients, particularly cardiac changes that markedly increase stroke volume, heart rate, cardiac output, and plasma volume.

The range of genetic screening and testing options has broadened

Options include first-trimester CVS, which provides information about the fetal chromosomal complement but not the presence of a fetal open neural tube defect. The procedure-related rate of fetal loss with CVS is quoted as 1%.

Options for genetic testing in the second trimester include transabdominal amniocentesis. A procedure-related fetal loss rate of 1 in 500 to 1 in 1,600 is quoted for midtrimester amniocentesis.

A relatively new screening option is analysis of cell-free fetal DNA in maternal blood, which can be performed after 10 weeks’ gestation in singleton and multiple gestations. This directed analysis measures the relative proportions of chromosomes. The detection rate for fetal Down syndrome using cell-free fetal DNA is greater than 98%, with a false-positive rate of less than 0.5%. However, this screening is unreliable in triplet gestations.

Other screening options include US and biochemical screening to detect fetal aneuploidy and open neural tube defects during the second trimester. These options should be included in counseling of the patient.

Second and third trimesters

Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia are significant risks

Older pregnant women have an incidence of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia 2 to 4 times as high as that of patients younger than 30 years.13 The underlying risk for preeclampsia is further increased if coexisting medical disorders such as diabetes or chronic hypertension are present. Moreover, the risk for preeclampsia increases to 10% to 20% in twin gestations and 25% to 60% in triplet gestations. Le Ray and colleagues reported that, if oocyte donation is used with IVF in women older than age 43, the risk for preeclampsia triples.14

We previously studied 379 women aged 35 and older who had mild gestational hypertension remote from term, comparing them with their younger adult counterparts in a matched cohort design.15 Outpatient management produced similar maternal outcomes in both groups, but older women had a statistically insignificant increase in the rate of stillbirth (5 vs 0; P = .063).15

Gestational diabetes risk doubles

The rates of both diabetes mellitus and gestational diabetes increase with advanced maternal age. Data from the FASTER consortium included an adjusted odds ratio of 2.4 for gestational diabetes in women aged 40 or older, compared with a younger control group.4 This increased risk may be a consequence of greater maternal habitus as well as declining insulin sensitivity.

Diabetes increases the risks of macrosomia, cesarean birth, and gestational hypertension. Among women with pregestational diabetes, the risks of congenital heart disease and fetal neural tube defects increase threefold. Because of this increased risk, perinatal screening is indicated for both anomalies in older women.

Pulmonary complications increase

Another risk facing women of advanced maternal age—particularly those carrying a multiple gestation—is pulmonary edema, owing to the increased cardiac output, heart rate, and blood volume, the decreased systemic vascular resistance, and the physiologic anemia of pregnancy. These risks rise further in women who develop preterm labor that requires therapy and in those who develop gestational hypertension and/or preeclampsia. Judicious use of IV fluids, particularly those with lower sodium concentrations, can reduce the risk of pulmonary complications.

Women who develop pulmonary edema have an increased risk of peripartum cardiomyopathy.16

Preterm delivery is more common

Cleary-Goodman and colleagues noted an increased incidence of preterm delivery in women aged 40 and older, compared with women younger than age 35, but no increase in spontaneous preterm labor.4 Advanced maternal age appears to be associated with an increased risk of preterm birth largely as a consequence of underlying complications of fetal growth restriction and maternal disease, including hypertension. Because preterm birth is an important contributor to perinatal morbidity and mortality, steroids should be administered for fetal lung maturity whenever preterm labor is diagnosed before 34 weeks’ gestation.

Risk of placenta previa is 1.1%

Joseph and colleagues found the risk of placenta previa to be 1.1% in women aged 40 and older, compared with 0.3% in women aged 25 to 29 years.17 This increased risk likely is a consequence not only of maternal age but increased parity and a history of prior uterine surgery. If transabdominal US results are suspicious for placenta previa, transvaginal US is indicated for confirmation. Additional US assessment of the cord insertion site to the placenta also should be performed to rule out vasa previa.

Look for neonatal complications

Ziadeh and colleagues found that, although maternal morbidity was increased in older women, the overall neonatal outcome did not appear to be affected.18 However, we noted a higher rate of neonatal complications in women aged 40 or older, including higher NICU admission rates and more low-birth–weight infants.11

In addition, Odibo and colleagues found advanced maternal age to be an independent risk factor for intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).19 In that study, the odds ratio for IUGR was 3.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.9–5.4) for a maternal age of 40 years or older, compared with a control group. For that reason, they recommend routine screening for IUGR in all pregnant women of advanced age.

Stillbirth risk peaks at 37 to 41 weeks

In a review of more than 5.4 million singleton pregnancies without reported congenital anomalies, Reddy and colleagues found an association between advanced maternal age and stillbirth, with a higher risk of stillbirth at 37 to 41 weeks’ gestation.6 This effect of maternal age persisted despite adjusting for medical disease, parity, and race/ethnicity.

Many women older than age 40 have independent medical or fetal indications for antenatal testing. Some experts have suggested antepartum surveillance starting at 37 weeks for women of advanced maternal age; they argue that the risk of stillbirth at this gestational age is similar in frequency to other high-risk conditions for which testing is performed routinely. However, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) workshop on antepartum fetal monitoring found insufficient evidence that antenatal testing for the sole indication of advanced maternal age reduces stillbirth or improves perinatal outcomes.20

If increased antenatal testing is indicated for a high-risk condition or electively chosen given advanced age, it should include electronic fetal monitoring as well as amniotic fluid volume assessment. Because the risk of fetal loss sharply increased at 40 weeks’ gestation in the study by Reddy and colleagues,6 women older than age 40 should be considered for delivery by 40 weeks’ gestation in the presence of good dating criteria.

Some clinicians also would consider delivery by 39 weeks’ gestation with good dating criteria if the Bishop score is favorable.

Risks of labor and delivery

Multiple variables contribute to a higher cesarean delivery rate

The risk of cesarean delivery increases with advancing maternal age.5,11 This increased risk is a consequence of multiple variables, including the rate of previous cesarean delivery, malpresentation, underlying complications such as preeclampsia and diabetes, and a higher prevalence of dysfunctional labor.21 Further, Vaughn and colleagues noted that the cesarean delivery rate increases in direct proportion to age, with a rate of 54.4% in women older than age 40.5

As Cohen pointed out in a commentary accompanying a study of dysfunctional labor in women of advancing age, “the notion of a premium baby (ie, that the fetus of a woman with a reduced likelihood of having another pregnancy is somehow more deserving of being spared the rigours of labour than the fetus of a young woman) may play a role” in the high rate of cesarean delivery.21,22

Postpartum hemorrhage risk may be lower in older women

Advanced maternal age is assumed to be a risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage.23 The increased risk was thought to be related to the increased incidence of multiple underlying factors, such as cesarean delivery, multiple gestation, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

However, in a retrospective cohort study, Lao and colleagues found that advanced maternal age (≥35 years) served only as a surrogate factor for postpartum hemorrhage due to associated risk factors, obstetric complications, and interventions.24 After multivariate analysis, aging was associated with a decreased rate of postpartum hemorrhage, which declined progressively from ages 25 to 40 years and older, compared with women aged 20 to 24.24

Nevertheless, medical interventions should be readily available at the time of delivery for treatment of uterine atony, especially with multiple gestation and grand multiparity.

Case: Resolved

The patient is admitted to the hospital, where she is given IV magnesium sulfate (6-g load followed by an infusion of 3 g/hr) and betamethasone for fetal lung maturity enhancement. She continues to receive IV fluids as well (125 mL/hr lactated Ringers solution). Uterine activity abates.

IV magnesium sulfate is continued for 36 hours, but urine protein output is not monitored. Her heart rate ranges from 105 to 115 bpm, and blood pressure from 130/80 mm Hg to 138/88 mm Hg. Forty-eight hours after admission, she reports a gradual onset of tightness of the chest and breathlessness. She is agitated, with a pulse of 130 bpm, 30 respirations/min, and room air pulse oximetry of 90%. Rales are noted upon auscultation of both lungs. A radiograph of the chest demonstrates bilateral air-space disease consistent with pulmonary edema. IV furosemide and oxygen (by mask) are provided, with some respiratory improvement.

The patient then reports leakage of amniotic fluid, and preterm rupture of membranes is confirmed on examination. Because steroids for fetal lung maturity have been administered, and given improvement in her pulmonary edema and a footling breech presentation for Twin A, cesarean delivery is performed.

The patient’s immediate postoperative course is uncomplicated. On postoperative day 2, however, she develops recurrent pulmonary edema, as confirmed by physical examination and chest radiograph. She also reports headache, and her blood pressure rises to 164/114 mm Hg—findings consistent with postpartum preeclampsia. Magnesium sulfate and antihypertensive therapy are initiated, along with IV furosemide and oxygen, which improves her respiratory status.