User login

Drug combinations found to increase upper gastrointestinal bleeding risk

Combining nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increased the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding by up to 190% beyond the baseline risk found for NSAID monotherapy, researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients also faced excess risks of upper GI bleeding when they took corticosteroids, aldosterone antagonists, or anticoagulants together with low-dose aspirin or nonselective NSAIDs, although the effect was not seen for COX-2 inhibitors, said Dr. Gwen Masclee at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and her associates.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings should help clinicians tailor treatments to minimize chances of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly for elderly patients who often take multiple drugs, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.007]).

The researchers analyzed 114,835 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including all gastroduodenal ulcers and hemorrhages extracted from seven electronic health record databases from the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark. Three databases included primary care data, and four were administrative claims data, the investigators said. Cases served as their own controls, they noted.

Monotherapy with prescription nonselective NSAIDs increased the chances of an upper gastrointestinal bleed by 4.3 times, compared with not using any of the drugs studied (95% confidence interval, 4.1-4.4), the researchers said. Notably, bleeding risk from taking either nonselective NSAIDs or corticosteroids was the same, they said, adding that previous studies have yielded inconsistent findings on the topic. The incidence ratios for monotherapy with low-dose aspirin and COX-2 inhibitors were slightly lower at 3.1 (95% CI, 2.9-3.2) and 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.2), respectively, they added.

Combining nonselective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, or low-dose aspirin with SSRIs led to excess risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding of 1.6 (95% CI, 0.5-2.6), 1.9 (95% CI, 0.2-3.4), and 0.49 (–0.05-1.03), respectively, the researchers reported. "From a biological point of view, this interaction seems plausible because SSRIs decrease the serotonin level, resulting in impaired thrombocyte aggregation and an increased risk of bleeding in general," they said.

Corticosteroids combined with nonselective NSAIDs led to the greatest increases in bleeding risk, with an incidence ratio of 12.8 (95% CI, 11.1-14.7), compared with nonuse of any drug studied, and an excess risk of 5.5 (3.7-7.3), compared with NSAID use alone, said the researchers. Adding aldosterone antagonists to nonselective NSAIDs led to an excess risk of 4.46, compared with using nonselective NSAIDs alone, they reported (95% CI, 1.79-7.13).

Because the study did not capture over-the-counter NSAID prescriptions, it could have underestimated use of these drugs, the investigators said. Also, changes in health or NSAID use during the study could have created residual confounding, although sensitivity analyses did not reveal problems, they reported. They added that misclassification of some data could have led them to underestimate risks. "Finally, we did not take any carryover effect or dose of drug exposure into account, which potentially limits the generalizability concerning causality of the associations," they concluded.

Five authors reported employment or other financial support from Erasmus University Medical Center, AstraZeneca, Janssen, PHARMO Institute, and the European Medicines Agency. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interests.

Gastrointestinal toxicity is the major issue limiting nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use. The excess annual risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding per 1,000 patients is about 1 with low-dose aspirin, about 2 with coxibs, and about 4-6 with traditional NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen). However, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding increases markedly with several factors, including the use of concomitant medications.

Ideally, large randomized trials comparing NSAIDs with and without a concomitant medication would inform our assessment of risk. However, few such trials are available, so we commonly rely on observational database studies, such as that of Masclee et al. These studies have the important benefit of large sample size and "real world" results, but also have potential limitations, including reliability of data (for example, accuracy of diagnostic coding) and potential bias because of unequal distribution of confounding factors between cases and controls.

Masclee et al. report significant synergy (more than additive risk) of traditional NSAIDs with corticosteroids, SSRIs, aldosterone antagonists, and antithrombotic agents other than low-dose aspirin (although risk was increased with traditional NSAIDs plus low-dose aspirin). Low-dose aspirin was synergistic with antithrombotic agents and corticosteroids, while coxibs were synergistic with low-dose aspirin and SSRIs.

The results of Masclee et al. support current North American guidelines, which suggest use of proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol for traditional NSAID users taking concomitant medications such as antithrombotics, corticosteroids, or SSRIs, and use of PPIs for low-dose-aspirin users taking antithrombotics or taking corticosteroids if greater than or equal to 60 years old. Their results also suggest further evaluation of aldosterone antagonists is warranted as another possible risk factor.

Dr. Loren Laine is professor of medicine, department of internal medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He is on the Data Safety Monitoring Boards of Eisai, BMS, and Bayer; and is a consultant for AstraZeneca.

Gastrointestinal toxicity is the major issue limiting nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use. The excess annual risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding per 1,000 patients is about 1 with low-dose aspirin, about 2 with coxibs, and about 4-6 with traditional NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen). However, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding increases markedly with several factors, including the use of concomitant medications.

Ideally, large randomized trials comparing NSAIDs with and without a concomitant medication would inform our assessment of risk. However, few such trials are available, so we commonly rely on observational database studies, such as that of Masclee et al. These studies have the important benefit of large sample size and "real world" results, but also have potential limitations, including reliability of data (for example, accuracy of diagnostic coding) and potential bias because of unequal distribution of confounding factors between cases and controls.

Masclee et al. report significant synergy (more than additive risk) of traditional NSAIDs with corticosteroids, SSRIs, aldosterone antagonists, and antithrombotic agents other than low-dose aspirin (although risk was increased with traditional NSAIDs plus low-dose aspirin). Low-dose aspirin was synergistic with antithrombotic agents and corticosteroids, while coxibs were synergistic with low-dose aspirin and SSRIs.

The results of Masclee et al. support current North American guidelines, which suggest use of proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol for traditional NSAID users taking concomitant medications such as antithrombotics, corticosteroids, or SSRIs, and use of PPIs for low-dose-aspirin users taking antithrombotics or taking corticosteroids if greater than or equal to 60 years old. Their results also suggest further evaluation of aldosterone antagonists is warranted as another possible risk factor.

Dr. Loren Laine is professor of medicine, department of internal medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He is on the Data Safety Monitoring Boards of Eisai, BMS, and Bayer; and is a consultant for AstraZeneca.

Gastrointestinal toxicity is the major issue limiting nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use. The excess annual risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding per 1,000 patients is about 1 with low-dose aspirin, about 2 with coxibs, and about 4-6 with traditional NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen). However, the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding increases markedly with several factors, including the use of concomitant medications.

Ideally, large randomized trials comparing NSAIDs with and without a concomitant medication would inform our assessment of risk. However, few such trials are available, so we commonly rely on observational database studies, such as that of Masclee et al. These studies have the important benefit of large sample size and "real world" results, but also have potential limitations, including reliability of data (for example, accuracy of diagnostic coding) and potential bias because of unequal distribution of confounding factors between cases and controls.

Masclee et al. report significant synergy (more than additive risk) of traditional NSAIDs with corticosteroids, SSRIs, aldosterone antagonists, and antithrombotic agents other than low-dose aspirin (although risk was increased with traditional NSAIDs plus low-dose aspirin). Low-dose aspirin was synergistic with antithrombotic agents and corticosteroids, while coxibs were synergistic with low-dose aspirin and SSRIs.

The results of Masclee et al. support current North American guidelines, which suggest use of proton pump inhibitors or misoprostol for traditional NSAID users taking concomitant medications such as antithrombotics, corticosteroids, or SSRIs, and use of PPIs for low-dose-aspirin users taking antithrombotics or taking corticosteroids if greater than or equal to 60 years old. Their results also suggest further evaluation of aldosterone antagonists is warranted as another possible risk factor.

Dr. Loren Laine is professor of medicine, department of internal medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn. He is on the Data Safety Monitoring Boards of Eisai, BMS, and Bayer; and is a consultant for AstraZeneca.

Combining nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increased the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding by up to 190% beyond the baseline risk found for NSAID monotherapy, researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients also faced excess risks of upper GI bleeding when they took corticosteroids, aldosterone antagonists, or anticoagulants together with low-dose aspirin or nonselective NSAIDs, although the effect was not seen for COX-2 inhibitors, said Dr. Gwen Masclee at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and her associates.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings should help clinicians tailor treatments to minimize chances of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly for elderly patients who often take multiple drugs, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.007]).

The researchers analyzed 114,835 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including all gastroduodenal ulcers and hemorrhages extracted from seven electronic health record databases from the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark. Three databases included primary care data, and four were administrative claims data, the investigators said. Cases served as their own controls, they noted.

Monotherapy with prescription nonselective NSAIDs increased the chances of an upper gastrointestinal bleed by 4.3 times, compared with not using any of the drugs studied (95% confidence interval, 4.1-4.4), the researchers said. Notably, bleeding risk from taking either nonselective NSAIDs or corticosteroids was the same, they said, adding that previous studies have yielded inconsistent findings on the topic. The incidence ratios for monotherapy with low-dose aspirin and COX-2 inhibitors were slightly lower at 3.1 (95% CI, 2.9-3.2) and 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.2), respectively, they added.

Combining nonselective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, or low-dose aspirin with SSRIs led to excess risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding of 1.6 (95% CI, 0.5-2.6), 1.9 (95% CI, 0.2-3.4), and 0.49 (–0.05-1.03), respectively, the researchers reported. "From a biological point of view, this interaction seems plausible because SSRIs decrease the serotonin level, resulting in impaired thrombocyte aggregation and an increased risk of bleeding in general," they said.

Corticosteroids combined with nonselective NSAIDs led to the greatest increases in bleeding risk, with an incidence ratio of 12.8 (95% CI, 11.1-14.7), compared with nonuse of any drug studied, and an excess risk of 5.5 (3.7-7.3), compared with NSAID use alone, said the researchers. Adding aldosterone antagonists to nonselective NSAIDs led to an excess risk of 4.46, compared with using nonselective NSAIDs alone, they reported (95% CI, 1.79-7.13).

Because the study did not capture over-the-counter NSAID prescriptions, it could have underestimated use of these drugs, the investigators said. Also, changes in health or NSAID use during the study could have created residual confounding, although sensitivity analyses did not reveal problems, they reported. They added that misclassification of some data could have led them to underestimate risks. "Finally, we did not take any carryover effect or dose of drug exposure into account, which potentially limits the generalizability concerning causality of the associations," they concluded.

Five authors reported employment or other financial support from Erasmus University Medical Center, AstraZeneca, Janssen, PHARMO Institute, and the European Medicines Agency. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interests.

Combining nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increased the risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding by up to 190% beyond the baseline risk found for NSAID monotherapy, researchers reported in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Patients also faced excess risks of upper GI bleeding when they took corticosteroids, aldosterone antagonists, or anticoagulants together with low-dose aspirin or nonselective NSAIDs, although the effect was not seen for COX-2 inhibitors, said Dr. Gwen Masclee at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam, the Netherlands and her associates.

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings should help clinicians tailor treatments to minimize chances of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly for elderly patients who often take multiple drugs, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 [doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.007]).

The researchers analyzed 114,835 cases of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, including all gastroduodenal ulcers and hemorrhages extracted from seven electronic health record databases from the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark. Three databases included primary care data, and four were administrative claims data, the investigators said. Cases served as their own controls, they noted.

Monotherapy with prescription nonselective NSAIDs increased the chances of an upper gastrointestinal bleed by 4.3 times, compared with not using any of the drugs studied (95% confidence interval, 4.1-4.4), the researchers said. Notably, bleeding risk from taking either nonselective NSAIDs or corticosteroids was the same, they said, adding that previous studies have yielded inconsistent findings on the topic. The incidence ratios for monotherapy with low-dose aspirin and COX-2 inhibitors were slightly lower at 3.1 (95% CI, 2.9-3.2) and 2.9 (95% CI, 2.7-3.2), respectively, they added.

Combining nonselective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, or low-dose aspirin with SSRIs led to excess risks of upper gastrointestinal bleeding of 1.6 (95% CI, 0.5-2.6), 1.9 (95% CI, 0.2-3.4), and 0.49 (–0.05-1.03), respectively, the researchers reported. "From a biological point of view, this interaction seems plausible because SSRIs decrease the serotonin level, resulting in impaired thrombocyte aggregation and an increased risk of bleeding in general," they said.

Corticosteroids combined with nonselective NSAIDs led to the greatest increases in bleeding risk, with an incidence ratio of 12.8 (95% CI, 11.1-14.7), compared with nonuse of any drug studied, and an excess risk of 5.5 (3.7-7.3), compared with NSAID use alone, said the researchers. Adding aldosterone antagonists to nonselective NSAIDs led to an excess risk of 4.46, compared with using nonselective NSAIDs alone, they reported (95% CI, 1.79-7.13).

Because the study did not capture over-the-counter NSAID prescriptions, it could have underestimated use of these drugs, the investigators said. Also, changes in health or NSAID use during the study could have created residual confounding, although sensitivity analyses did not reveal problems, they reported. They added that misclassification of some data could have led them to underestimate risks. "Finally, we did not take any carryover effect or dose of drug exposure into account, which potentially limits the generalizability concerning causality of the associations," they concluded.

Five authors reported employment or other financial support from Erasmus University Medical Center, AstraZeneca, Janssen, PHARMO Institute, and the European Medicines Agency. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interests.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Excess risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding occurred with combinations of NSAIDs and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and with combinations of nonselective NSAIDs or low-dose aspirin with corticosteroids, aldosterone antagonists, or anticoagulants.

Major finding: Excess risks from combining SSRIs with nonselective NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, or low-dose aspirin were 1.62 (95% CI, 0.58-2.66), 1.86 (95% CI, 0.28- 3.44), and 0.49 (95% CI, –0.05-1.03), respectively.

Data source: Case series analysis of 114,835 patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Patients were identified from seven electronic health record databases from the Netherlands, Italy, and Denmark, and cases served as their own controls.

Disclosures: Five authors reported employment or other financial support from Erasmus University Medical Center, AstraZeneca, Janssen, PHARMO Institute, and the European Medicines Agency. The other authors reported no relevant conflicts of interests.

Pediatric IBD rose by more than 40% in 15 years

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease grew by more than 40% in a 15-year period in Ontario, Canada, according to a retrospective cohort study published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Although rates of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rose in children and adolescents of all ages, the steepest increase occurred in children with very-early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD), defined as disease diagnosed before they were 10 years old, said Dr. Eric Benchimol at the University of Ottawa and his associates. But these patients also tended to use fewer health services and have fewer surgeries for IBD, compared with older children with the disease, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 October [doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.023]).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings add to research indicating that VEO-IBD is a distinct form of IBD and indicate the need to assess subgroups of these patients to look at phenotype, genotype, intestinal microbiome, and treatment response, the investigators said.

For the study, researchers created a cohort based on an algorithm of health care visits that identified all children and adolescents in Ontario diagnosed with IBD before age 18 years. The analysis included 7,143 patients with IBD, among whom about 14% had VEO-IBD, the investigators reported.

The overall rate of IBD in children up to 18 years old increased from 9.4 to 13.2 cases per 100,000 population from 1994 through 2009 (P less than .0001), the researchers said. And the yearly increase in VEO-IBD averaged 7.4% – more than three times greater than the 2.2% average annual rise among children diagnosed at 10 years and older, the investigators reported.

But health care utilization trends did not mirror changes in incidence, Dr. Benchimol and associates reported. For example, children diagnosed before they were 6 years old had significantly fewer outpatient visits for IBD, compared with children diagnosed at 10 years and older (odds ratio for girls, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-0.78; OR for boys, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98). Furthermore, patients diagnosed before age 6 years were less likely to be hospitalized for IBD than were older children with the disease (hazard ratio for girls, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.87; HR for boys, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.94-1.33), the investigators said.

The likelihood of undergoing intestinal resection also was lower for children diagnosed before age 6 years with Crohn’s disease, compared with older girls (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16-0.78) and boys (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34-0.99), said the researchers. And patients diagnosed before age 6 years with ulcerative colitis were less likely to undergo colectomy than were older girls (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.47-1.63) and boys (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85). In contrast, rates of IBD-related surgery and hospitalization were similar between children diagnosed at 6-9.9 years of age and those diagnosed at age 10 up to 18 years, the investigators said.

A cohort study from the United States also found a lower likelihood of surgery in children with VEO-IBD, the researchers noted. Large-bowel involvement without ileal disease is prominent in young children with IBD, and these patients might be unlikely to undergo resection because colectomy requires a permanent ostotomy, they added.

The work was supported by the American College of Gastroenterology, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, the National Institutes of Health, the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research, the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease grew by more than 40% in a 15-year period in Ontario, Canada, according to a retrospective cohort study published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Although rates of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rose in children and adolescents of all ages, the steepest increase occurred in children with very-early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD), defined as disease diagnosed before they were 10 years old, said Dr. Eric Benchimol at the University of Ottawa and his associates. But these patients also tended to use fewer health services and have fewer surgeries for IBD, compared with older children with the disease, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 October [doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.023]).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings add to research indicating that VEO-IBD is a distinct form of IBD and indicate the need to assess subgroups of these patients to look at phenotype, genotype, intestinal microbiome, and treatment response, the investigators said.

For the study, researchers created a cohort based on an algorithm of health care visits that identified all children and adolescents in Ontario diagnosed with IBD before age 18 years. The analysis included 7,143 patients with IBD, among whom about 14% had VEO-IBD, the investigators reported.

The overall rate of IBD in children up to 18 years old increased from 9.4 to 13.2 cases per 100,000 population from 1994 through 2009 (P less than .0001), the researchers said. And the yearly increase in VEO-IBD averaged 7.4% – more than three times greater than the 2.2% average annual rise among children diagnosed at 10 years and older, the investigators reported.

But health care utilization trends did not mirror changes in incidence, Dr. Benchimol and associates reported. For example, children diagnosed before they were 6 years old had significantly fewer outpatient visits for IBD, compared with children diagnosed at 10 years and older (odds ratio for girls, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-0.78; OR for boys, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98). Furthermore, patients diagnosed before age 6 years were less likely to be hospitalized for IBD than were older children with the disease (hazard ratio for girls, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.87; HR for boys, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.94-1.33), the investigators said.

The likelihood of undergoing intestinal resection also was lower for children diagnosed before age 6 years with Crohn’s disease, compared with older girls (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16-0.78) and boys (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34-0.99), said the researchers. And patients diagnosed before age 6 years with ulcerative colitis were less likely to undergo colectomy than were older girls (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.47-1.63) and boys (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85). In contrast, rates of IBD-related surgery and hospitalization were similar between children diagnosed at 6-9.9 years of age and those diagnosed at age 10 up to 18 years, the investigators said.

A cohort study from the United States also found a lower likelihood of surgery in children with VEO-IBD, the researchers noted. Large-bowel involvement without ileal disease is prominent in young children with IBD, and these patients might be unlikely to undergo resection because colectomy requires a permanent ostotomy, they added.

The work was supported by the American College of Gastroenterology, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, the National Institutes of Health, the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research, the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Pediatric inflammatory bowel disease grew by more than 40% in a 15-year period in Ontario, Canada, according to a retrospective cohort study published in the October issue of Gastroenterology.

Although rates of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) rose in children and adolescents of all ages, the steepest increase occurred in children with very-early-onset IBD (VEO-IBD), defined as disease diagnosed before they were 10 years old, said Dr. Eric Benchimol at the University of Ottawa and his associates. But these patients also tended to use fewer health services and have fewer surgeries for IBD, compared with older children with the disease, the investigators said (Gastroenterology 2014 October [doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2014.06.023]).

Source: American Gastroenterological Association

The findings add to research indicating that VEO-IBD is a distinct form of IBD and indicate the need to assess subgroups of these patients to look at phenotype, genotype, intestinal microbiome, and treatment response, the investigators said.

For the study, researchers created a cohort based on an algorithm of health care visits that identified all children and adolescents in Ontario diagnosed with IBD before age 18 years. The analysis included 7,143 patients with IBD, among whom about 14% had VEO-IBD, the investigators reported.

The overall rate of IBD in children up to 18 years old increased from 9.4 to 13.2 cases per 100,000 population from 1994 through 2009 (P less than .0001), the researchers said. And the yearly increase in VEO-IBD averaged 7.4% – more than three times greater than the 2.2% average annual rise among children diagnosed at 10 years and older, the investigators reported.

But health care utilization trends did not mirror changes in incidence, Dr. Benchimol and associates reported. For example, children diagnosed before they were 6 years old had significantly fewer outpatient visits for IBD, compared with children diagnosed at 10 years and older (odds ratio for girls, 0.67; 95% confidence interval, 0.58-0.78; OR for boys, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98). Furthermore, patients diagnosed before age 6 years were less likely to be hospitalized for IBD than were older children with the disease (hazard ratio for girls, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56-0.87; HR for boys, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.94-1.33), the investigators said.

The likelihood of undergoing intestinal resection also was lower for children diagnosed before age 6 years with Crohn’s disease, compared with older girls (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.16-0.78) and boys (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.34-0.99), said the researchers. And patients diagnosed before age 6 years with ulcerative colitis were less likely to undergo colectomy than were older girls (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.47-1.63) and boys (HR, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85). In contrast, rates of IBD-related surgery and hospitalization were similar between children diagnosed at 6-9.9 years of age and those diagnosed at age 10 up to 18 years, the investigators said.

A cohort study from the United States also found a lower likelihood of surgery in children with VEO-IBD, the researchers noted. Large-bowel involvement without ileal disease is prominent in young children with IBD, and these patients might be unlikely to undergo resection because colectomy requires a permanent ostotomy, they added.

The work was supported by the American College of Gastroenterology, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, the National Institutes of Health, the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research, the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Key clinical point: Although the steepest rise in inflammatory bowel disease occurred in children diagnosed before age 10 years, children diagnosed before age 6 years had the lowest rates of IBD-related outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and surgeries.

Major finding: Rates of pediatric IBD increased by more than 40% between 1994 and 2009 in Ontario, Canada. Rates rose by an average of 7.4% annually in children diagnosed before age 10 years, compared with 2.2% for children diagnosed from 10 years to before 18 years of age. Rates of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and IBD-related surgeries were significantly lower in children diagnosed before age 6 years, compared with children diagnosed at 10 years or older.

Data Source: Retrospective study of the Ontario Crohn’s and Colitis Cohort, which included 7,143 children and adolescents with IBD diagnosed between 1994 and 2009 in Ontario, Canada.

Disclosures: The work was supported by grants and researcher awards from the American College of Gastroenterology, the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, the National Institutes of Health, the Wolpow Family Chair in IBD Treatment and Research, the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation, and the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Metastatic Brain Tumors

Series Editor: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Systemic cancer can affect the central nervous system in several different ways, including direct tumor metastasis and indirect remote effects. Intracranial metastasis can involve the skull, dura, and leptomeninges (arachnoid and pia mater), as well as the brain parenchyma. Of these, parenchymal brain metastases are the most common and have been found in as many as 24% of cancer patients in autopsy studies. It has been reported that metastatic brain tumors outnumber primary brain tumors 10 to 1.

To read the full article in PDF:

Series Editor: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Systemic cancer can affect the central nervous system in several different ways, including direct tumor metastasis and indirect remote effects. Intracranial metastasis can involve the skull, dura, and leptomeninges (arachnoid and pia mater), as well as the brain parenchyma. Of these, parenchymal brain metastases are the most common and have been found in as many as 24% of cancer patients in autopsy studies. It has been reported that metastatic brain tumors outnumber primary brain tumors 10 to 1.

To read the full article in PDF:

Series Editor: Arthur T. Skarin, MD, FACP, FCCP

Systemic cancer can affect the central nervous system in several different ways, including direct tumor metastasis and indirect remote effects. Intracranial metastasis can involve the skull, dura, and leptomeninges (arachnoid and pia mater), as well as the brain parenchyma. Of these, parenchymal brain metastases are the most common and have been found in as many as 24% of cancer patients in autopsy studies. It has been reported that metastatic brain tumors outnumber primary brain tumors 10 to 1.

To read the full article in PDF:

Quality and Safety During Off Hours

Patients experience acute illness at all hours of the day. In acute care hospitals, over 60% of patient admissions occur outside of normal business hours, or the off hours.[1, 2] Similarly, the acute decompensation of patients already admitted to hospital‐based units is frequent, with 90% of rapid responses occurring between 9 pm and 6 am.[3] Research suggests worse hospital performance during off hours, including increased patient falls, in‐hospital cardiac arrest mortality, and severity of hospital employee injuries.[2, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Although hospital‐based services should match care demand, the disparity between patient acuity and hospital capability at night is significant. Off hours typically have lower staffing of nurses, and attending and housestaff physicians, and ancillary staff as well as limited availability of consultative and supportive services.[8] Additionally, off‐hours providers are subject to the physiological effects of imbalanced circadian rhythms, including fatigue, attenuating their abilities to provide high‐quality care. The significant patient care needs mandate continuous patient care delivery without compromising quality or safety. To achieve this, further defining the barriers to delivering quality care during off hours is essential to improvement efforts in medicine‐based units.

Previous investigations have found increased occurrence and severity of worker accidents, increased potential for higher occurrence of preventable adverse patient events, and decreased performance during off hours.[4, 9, 10] Additionally, detrimental effects of off‐hours care may be further magnified by rotating employees through both day and night shifts, a common practice in academic hospitals.[11, 12] Potentially modifiable outcomes, such as patient fall rate and in‐hospital cardiac arrest survival differ markedly between day and night shifts.[6, 13] These studies primarily report on specific diseases, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, and are investigated from the perspective of hospital‐level outcomes.

To our knowledge, no study has reported provider‐perceived quality and safety issues occurring during off hours in an academic setting. Likewise, although off‐hours collaborative care requires shared, interprofessional conceptualization regarding care delivery, this perspective has not been reported. Understanding the similarities and differences between provider perceptions will allow the construction of an interprofessional team mental model, facilitating the design of future quality improvement initiatives.[14, 15] Our objectives were to: (1) identify off‐hours quality and safety issues, (2) assess which issues are perceived as most significant, and (3) evaluate differences in perceptions of these issues between nurses, and attending and housestaff physicians.

METHODS

Study Design

To investigate quality and safety issues occurring during off hours, we employed a prospective, mixed‐methods sequential exploratory study design, involving an initial qualitative analysis of adverse events followed by quantitative survey assessment.[16] We chose a mixed‐methods approach because provider‐perceived off‐hours issues had not been explicitly identified in the literature, requiring preliminary qualitative assessment. For the purpose of this study, we defined off hours as the 7 pm to 7am time period, which overlapped night shifts for both nurses and physicians. The study was approved by the institutional review board as a quality improvement project.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a 378‐bed, university‐based acute care hospital in central Pennsylvania. There are a total of 64 internal medicine beds located in 2 units: a general medicine unit (44 beds, staffed by 60 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:4) and an intermediate care unit (20 beds, staffed by 41 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:3). The medicine residency program consists of 69 residents and 14 combined internal medicinepediatrics residents. During the day, 3 teaching teams and 1 nonteaching team care for all medicine patients. Overnight, 3 junior/senior level residents admit patients to the medicine service, whereas 2 interns provide cross‐coverage for all medicine and specialty service patients. Starting in September 2012 (before data collection), an overnight faculty‐level academic hospitalist, or nocturnist, provided on‐site housestaff supervision.

Qualitative Data Collection

For the qualitative analysis, we used 2 methods to develop our database. First, we created an electronic survey (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article) to identify near misses/adverse events occurring overnight, distributed to the nocturnist, 3 daytime hospitalists, and unit charge nurses following each shift (October 2012March 2013). The survey items were developed for the purpose of this study, with several items modified from a previously published survey.[17] Second, residency program directors recorded field notes during end‐of‐rotation debriefings (1 hour) with departing overnight housestaff, which were then dictated and transcribed. The subsequent analysis from these sources informed the quantitative survey (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).

Survey Instrument

Three months after the initiation of qualitative data collection, 1 investigator (J.D.G.) developed a preliminary codebook to identify categories and themes. From this codebook, the research team drafted a survey instrument (the complete qualitative analysis occurred after survey development). To maintain focus on systematic quality improvement, items related to perceived mismanagement, relationship tensions, and professionalism were excluded. The survey was pilot‐tested with 5 faculty physicians and 2 nursing staff, prompting several modifications to improve clarity. Primary demographic items included provider role (nurse, attending physician, or housestaff physician) and years in current role. The 24 survey items were grouped into 5 different categories: (1) Quality of Care Delivery, (2) Communication and Coordination, (3) Staffing and Supervision, (4) Patient Transfers, and (5) Consulting Service Issues. Each item was investigated on a 7‐point scale (1=lowest rating, 7=highest rating). Descriptive text was provided at the extremes (choices 1 and 7), whereas intermediary values (26) did not have descriptive cues. The descriptive anchors for Quality of Care Delivery and Patient Transfers were 1=never and 7=always, whereas the descriptive anchors Communication and Coordination and Staffing and Supervision were 1=poor and 7=superior; Consulting Service Issues used a mix of both. Providers with off‐hours experience were asked to rank 4 time periods (710 pm, 10 pm1 am, 14 am, 47 am) regarding quality of care delivery in the medicine units (1=best, 4=worst). We asked both daytime and nighttime providers about perceptions of off‐hours care because, given the boundary spanning the nature of medical care across work shifts, daytime providers frequently identify issues not apparent until hours (or even days) after completion of a night shift. A similar design was used in prior work investigating safety at night.[17]

Quantitative Data Collection

In June of 2013, we emailed a survey link (

Data Analysis

Using the preliminary codebook, 2 investigators (J.D.G., E.M.) jointly analyzed a segment of the dataset using Atlas.ti 6.0 (Scientific Software, Berlin, Germany). Two investigators independently coded the data, compared codes for agreement, and updated the codebook. The remaining data were coded independently, with regular adjudication sessions to modify the codebook. All investigators reviewed and agreed upon themes and representative quotations.

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation statistics, Kruskal‐Wallis tests, and signed rank tests (with Bonferroni correction) were used to report group characteristics, correlate rank order, make comparisons between groups (nursing staff, and attending and housestaff physicians; day/night providers), and compare quality rankings by time period, respectively. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata/IC‐8 (StataCorp, College Park, TX).

RESULTS

Qualitative Analysis of Off‐Hours' Adverse Events and Near Misses

A total of 190 events were reported by daytime attending physicians (n=100), nocturnists (n=60), and nighttime charge nurses (n=30). Although questions asked participants to describe near misses/adverse events, respondents also reported a number of global quality issues not related to specific events. Similarly, debriefing sessions with housestaff (n=5) addressed both specific overnight events and residency‐related issues. Seven themes were identified: (1) perceived mismanagement, (2) quality of delivery processes, (3) communication and coordination, (4) staffing and supervision, (5) patient transfers, (6) consulting service issues, and, (7) professionalism/relational tensions. Table 1 lists the code frequencies and exemplary quotations.

| Category and Themes | Code Frequency No. (% of 322) | Representative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Perceived mismanagement | 97 (30) | We had a new admission to the general medicine unit with atrial flutter and rapid ventricular response who did not receive rate controlling agents but rather received diuretics. [The patient's] heart rate remained between 110 and 130 overnight, with a troponin rise in the am likely from demand. The attending note states rate controllers and discussed with housestaff, but this was not performed. |

| Quality of delivery processes | 63 (20) | One patient had a delay in MRI scanning in the off hours due to the scanner being down and scheduling. When the patient went down, there seemed to be little attempt to make sure patient went through scanner; unclear if housestaff called or not to come to assist. Now, the delay in care is even further along. |

| Communication and coordination | 50 (16) | A patient was transferred to the intermediate care unit with hypercarbic respiratory failure. The patient had delay of >1 hour to receive IV Bumex because pharmacy would not release the dose from Pyxis, and the nurse did not let us know there was a delay. When I asked the nurse why, she responded because she's not the only patient I have. I pointed out that the patient was in failure and needed Bumex, stat. If we had not clearly communicated either verbally or via computer, she should let us know how to do that better. |

| Staffing and supervision | 39 (12) | A patient was admitted DNR/DNI with advanced dementia, new on BiPaP at 100%, and hypotensive. The team's intern [identified] the need for interventions, including a central line. This was discussed with overloaded intensive care unit resident. The intern struggled until another resident assisted along with the night attending. Issues included: initial triage, no resident backup for team, and attending backup. I should have been more hands on in the moment to assist the intern navigating the system of care. Many issues here, but no senior resident was involved in care until [late]. |

| Patient transfers | 38 (12) | One patient went from the emergency department [to us] on the 5th floor at 7:45 pm. The ED placed an order for packed red blood cells and it was written at 4:45 pm. When patient arrived on our floor at 7:45 pm, the transfusion had not been started. The floor nurse started it at 8:10 pm . |

| Consulting services | 18 (6) | Regarding a new outside hospital transfer, the medicine team was informed that [the consulting service] would place official consult on the chart when imaging studies from the outside institution were available. Despite this, the consult was still not done after 36 hours, and [we are] still waiting. We contacted service several times. |

| Professionalism and relational tensions | 17 (5) | [One admission from the emergency department] involved a patient who received subcutaneous insulin for hyperkalemia as opposed to intravenous insulin. When brought to [their] attention, they became very confrontational and abrupt and denied having ordered or administered it that way, although it was documented in the EMR. |

Perceived Mismanagement

Participants commonly questioned the decision making, diagnosis, or management of off‐hours providers. Concerns included the response to acute illness (eg, delay in calling a code), treatment decisions (eg, diuresis in a patient with urinary retention), or omission of necessary actions (eg, no cultures ordered for septicemia).

Quality of Delivery Processes

Participants frequently described quality of care delivery issues primarily related to timeliness or delays in delivery processes (34/63 coding references), or patient safety issues (29/63 coding references). Described events revealed concerns about the timeliness of lab reporting, imaging, blood draws, and medication ordering/processing.

Communication and Coordination

Breakdowns in communication and coordination often threatened patient safety. Identified issues included poor communication between primary physicians, nurses, consulting services, and emergency department (ED) providers, as well as documentation within the electronic medical record.

Staffing and Supervision

Several events highlighted staffing or supervision limitations, such as perceived low nursing or physician staffing levels. The degree of nocturnist supervision was polarizing, with both increased and decreased levels of supervision reported as limiting care delivery (or housestaff education).

Patient Transfers

Patient transfers to medicine units from the ED, other inpatient units, or outside hospitals, were identified several times as an influential factor. The care transition and need for information exchange led to a perceived compromise in quality or safety.

Consulting Service Issues

Several examples highlighted perceived issues related to the communication, coordination, or timeliness of consultant services in providing care.

Professionalism/Relational Tensions

Last, providers described situations in which they perceived lack of professionalism or relational tensions between providers, either in regard to interactions or clinical decisions in patient care.

Quantitative Results

Of 214 surveys sent, data were collected from 160 respondents (75% response), including 64/101 nursing staff (63% response), 25/28 attending physicians (80% response), and 71/85 housestaff physicians (84% response). Table 2 describes the participant demographics.

| Variable | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| |

| Nursing staff | 64 (40) |

| Intermediate care unit | 20 |

| General medicine ward | 44 |

| All night shifts | 16 |

| Mix of day and night shifts | 26 |

| Years of experience, mean (SD) | 7.7 (9.7) |

| Attending physicians | 25 (16) |

| No. providing care only at night | 4 |

| No. of weeks as overnight hospitalist in past year, mean (SD) | 11.5 (4.1) |

| No. providing care only during the day | 21 |

| Years since residency graduation, mean (SD) | 9.0 (8.5) |

| Medicine residents | 71 (44) |

| Intern | 27 |

| Junior resident | 23 |

| Senior resident* | 21 |

Off‐Hours Quality and Safety Issues

Ratings and comparisons of the 24 items are shown in Table 3. For all items, the mean rating was below 5 (7‐point scale). Lowest‐rated (least optimal) items were: timeliness, safety, and communication involved with patients admitted from the ED, number of attending physicians, and timeliness of consults and blood draws. Highest‐rated (more optimal) items were: timely reporting of labs, timely identification of deteriorating status, medication ordering and processing, communication between physicians, and safety and communication involved with intraservice transfers.

| Category and Survey Item, Mean (SD)* | Total (160) | Providers With Night Experience | Nighttime Providers (116) | Daytime Providers (44) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurses (41) | Attending Physicians (4) | Housestaff (71) | P Value | |||||

| ||||||||

| Quality of care delivery | ||||||||

| Timely reporting of labs at night | 4.70 (1.39) | 5.12 (1.50) | 4.50 (1.00) | 4.61 (1.47) | 0.11 | 4.78 (1.48) | 4.48 (1.11) | 0.09 |

| Timely identification of deteriorating status | 4.67 (1.34) | 4.88 (1.36) | 5.00 (0.82) | 4.85 (1.20) | 0.93 | 4.86 (1.24) | 4.16 (1.45) | 0.006 |

| Medication ordering and processing | 4.63 (1.13) | 4.88 (1.25) | 5.25 (0.50) | 4.66 (1.08) | 0.19 | 4.76 (1.13) | 4.27 (1.06) | 0.01 |

| Timely completion of imaging at night | 4.29 (1.32) | 4.32 (1.46) | 4.75 (0.96) | 4.39 (1.29) | 0.88 | 4.38 (1.34) | 4.05 (1.26) | 0.12 |

| Timely reporting of results at night | 4.19 (1.43) | 4.27 (1.53) | 4.00 (1.83) | 4.11 (1.44) | 0.84 | 4.16 (1.47) | 4.27 (1.30) | 0.76 |

| Timely med release from pharmacy at night | 4.16 (1.29) | 4.00 (1.32) | 4.50 (0.58) | 4.28 (1.29) | 0.44 | 4.19 (1.28) | 4.09 (1.31) | 0.90 |

| Timely blood draws at night | 3.96 (1.52) | 4.63 (1.44) | 4.50 (0.58) | 3.53 (1.49) | <0.001 | 3.96 (1.54) | 3.98 (1.47) | 0.98 |

| Communication and coordination | ||||||||

| Communication between physicians | 4.63 (1.26) | 4.29 (1.23) | 6.00 (1.15) | 5.14 (1.12) | <0.001 | 4.87 (1.24) | 3.98 (1.09) | <0.001 |

| Communication between nursing and pharmacy | 4.39 (1.27) | 4.83 (1.41) | 5.00 (0.82) | 4.27 (1.29) | 0.04 | 4.49 (1.34) | 4.11 (4.11) | 0.08 |

| Communication between nursing and physicians | 4.39 (1.28) | 4.44 (1.36) | 5.00 (0.82) | 4.58 (1.31) | 0.64 | 4.54 (1.31) | 3.98 (1.13) | 0.01 |

| Documentation in medical record | 4.33 (1.36) | 5.00 (1.36) | 6.00 (0.82) | 4.23 1.19) | <0.001 | 4.56 (1.31) | 3.70 (1.30) | <0.001 |

| Ease of contacting primary providers at night | 4.31 (1.29) | 4.46 (1.27) | 6.00 (0.00) | 4.54 (1.18) | 0.02 | 4.56 (1.22) | 3.66 (1.27) | <0.001 |

| Staffing and supervision | ||||||||

| No. of nursing staff | 4.51 (1.27) | 4.54 (1.50) | 5.50 (0.58) | 4.59 (1.21) | 0.25 | 4.60 (1.31) | 4.25 (1.14) | 0.025 |

| Supervision of housestaff | 4.43 (1.34) | 4.56 (1.40) | 6.25 (0.50) | 4.55 (1.34) | 0.03 | 4.61 (1.37) | 3.95 (1.14) | 0.002 |

| No. of housestaff | 4.09 (1.39) | 4.27 (1.40) | 4.50 (1.29) | 4.11 (1.44) | 0.70 | 4.18 (1.41) | 3.86 (1.32) | 0.12 |

| No. of ancillary staff | 4.00 (1.40) | 4.27 (1.53) | 5.75 (0.96) | 3.85 (1.40) | 0.02 | 4.06 (1.48) | 3.84 (1.18) | 0.27 |

| No. of attending physicians | 3.79 (1.50) | 3.49 (1.76) | 5.25 (0.96) | 3.89 (1.43) | 0.07 | 3.79 (1.57) | 3.80 (1.32) | 0.98 |

| Patient transfers | ||||||||

| For patients accepted to medicine from another medicine unit | ||||||||

| Timely and safe patient transfers | 4.56 (1.28) | 5.15 (1.11) | 4.75 (0.50) | 4.55 (1.23) | 0.025 | 4.77 (1.20) | 4.00 (1.33) | 0.001 |

| High quality communication between providers | 4.55 (1.35) | 5.34 (1.13) | 5.00 (0.82) | 4.49 (1.22) | 0.001 | 4.81 (1.24) | 3.86 (1.41) | <0.001 |

| For patients admitted from emergency department to medicine unit | ||||||||

| Appropriate testing and treatment | 4.16 (1.34) | 4.15 (1.30) | 4.00 (1.83) | 4.21 (1.43) | 0.96 | 4.18 (1.39) | 4.11 (1.20) | 0.66 |

| Timely and safe transfers | 3.89 (1.38) | 3.63 (1.50) | 5.50 (0.58) | 4.08 (1.32) | 0.02 | 3.97 (1.40) | 3.68 1.29) | 0.23 |

| High‐quality communication between providers | 2.93 (1.38) | 2.56 (1.23) | 3.75 (1.26) | 3.00 (1.39) | 0.08 | 2.87 (1.35) | 3.07 (1.47) | 0.41 |

| Consulting service issues | ||||||||

| Timely consults at night | 4.04 (1.35) | 4.27 (1.28) | 4.00 (0.82) | 4.10 (1.47) | 0.69 | 4.16 (1.38) | 3.73 (1.25) | 0.053 |

| Communication between consults and physicians | 3.93 (1.40) | 3.46 (1.45) | 5.75 (1.26) | 4.35 (1.27) | <0.001 | 4.09 (1.42) | 3.50 (1.27) | 0.016 |

Comparisons Between Professional Groups With Night Experience

Of the 24 items, 11 showed statistically significant differences between groups (P<0.05). Items with the largest difference between groups included: timely blood draws at night (housestaff physicians lowest), communication between physicians (nursing lowest), documentation in medical record (housestaff physicians lowest), and communication between consults and physicians (nursing lowest). The rank order between housestaff physicians and nurses, and housestaff and attending physicians showed moderately positive correlations (r=0.61, P=0.002 and r=0.47, P=0.022, respectively). The correlation between nurses and attending physicians showed a weak correlation (r=0.19, P=0.375).

Comparisons Between Front‐Line Providers With and Without Night Experience

Of the 24 items, 12 showed statistically significant differences between groups (P<0.05), with day providers reporting lower ratings in all 12. Items with the largest difference between groups included: communication between consults and physicians, ease of contacting providers, communication between providers, documentation, and safety and communication related to transfers from other units. The rank order between night and day groups showed a statistically significant positive correlation (r=0.65, P=0.001).

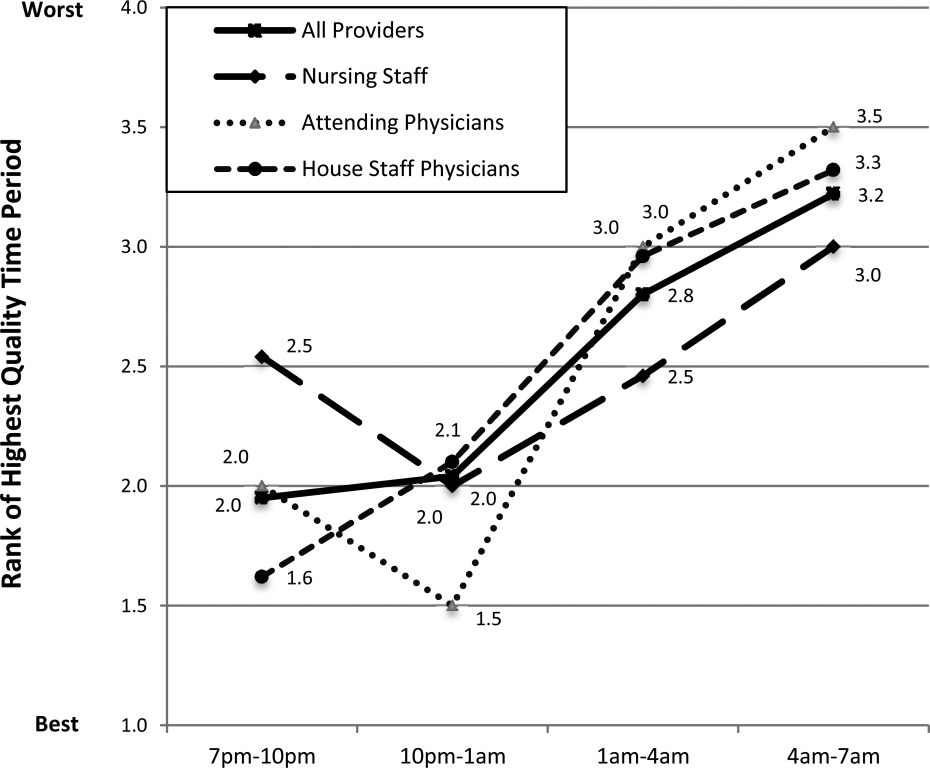

Perceived Highest Quality of Care Time Period During Off Hours

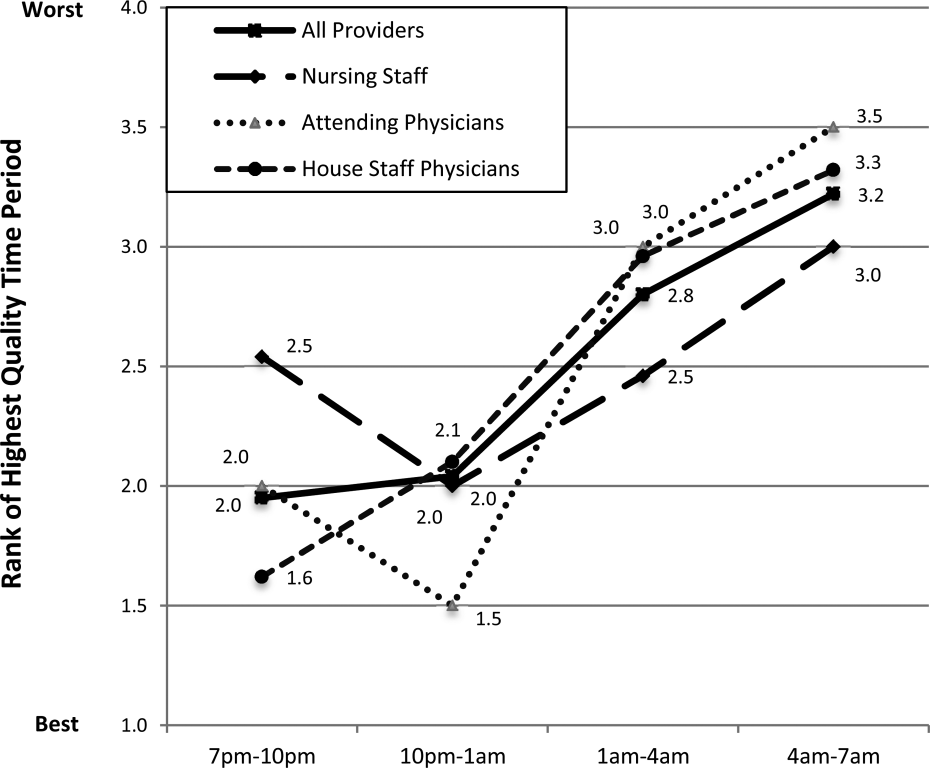

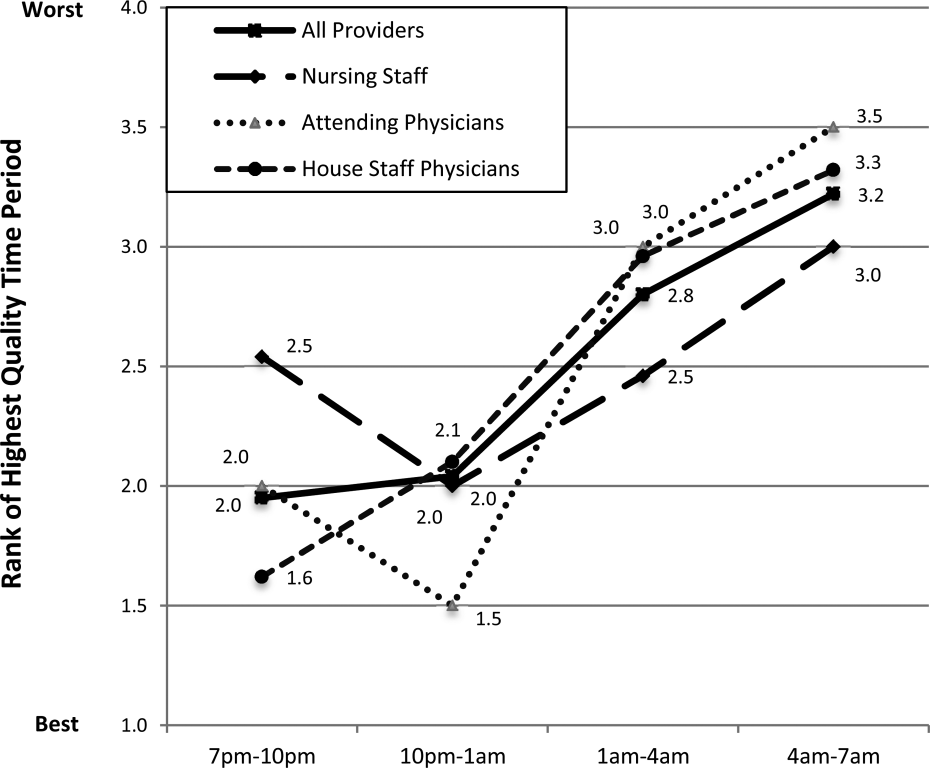

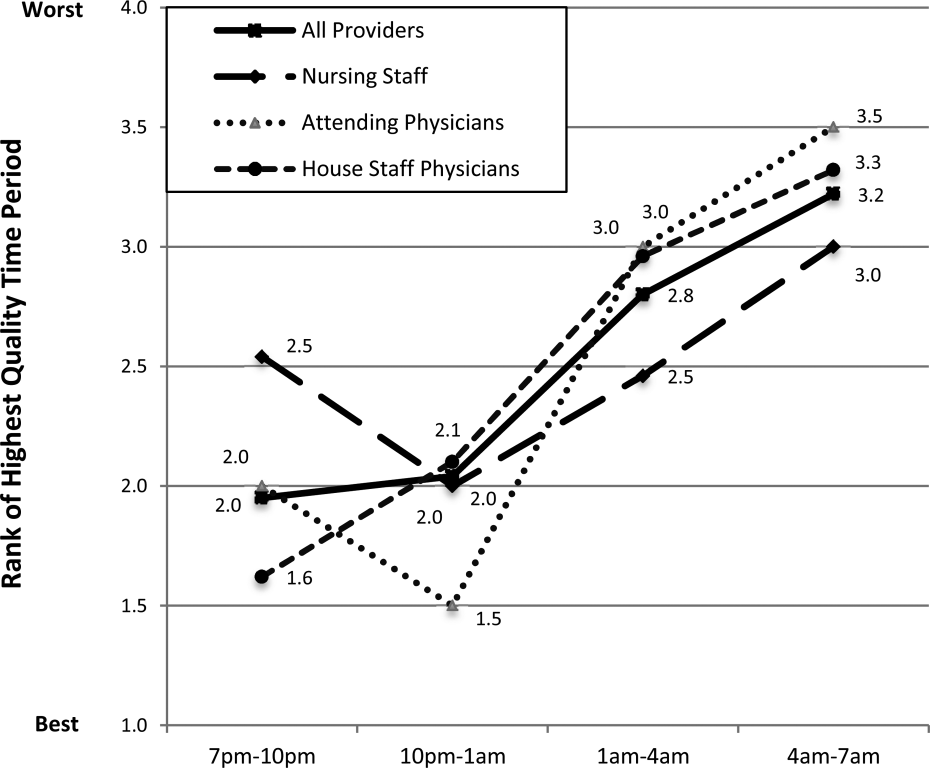

Compared with other time periods, all providers ranked 4 to 7 am as the period with the lowest quality of care delivery (mean rank 3.2, P0.001) (Figure 1). Nursing staff and attending physicians both ranked the 10 pm to 1 am time period as the best period (mean of 2.0 and 1.5, respectively), whereas housestaff physicians ranked the 7 to 10 pm as the best time period (mean 1.62). The only statistical difference between provider groups for any given time period was the 7 to 10 pm time period (P=0.002).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective, mixed‐methods study evaluating perceived off‐hours quality and safety issues, several themes were identified, including perceived mismanagement, insufficient quality of delivery processes, communication/coordination breakdowns, and staffing and supervision issues. In the quantitative analysis, lowest‐rated items (lowest quality) related to timeliness/safety/communication involved with ED transfers, number of attending physicians, and timeliness of consults and blood draws. Highest‐rated items (highest quality) related to timeliness of lab reporting and identification of deteriorating patients, medication ordering/processing, communication between physicians, and safety/communication during intraservice transfers. In general, day providers reported lower ratings than night providers on nearly all quality‐related items. Nursing staff reported the lowest ratings regarding communication between physicians and consults, whereas housestaff physicians reported the lowest ratings regarding documentation in the medical record and timely blood draws. These between‐group differences reveal the lack of shared conceptual understanding regarding off‐hours care delivery.

Our qualitative results reveal several significant issues related to care delivery during off hours, many of which are not obtainable by hospital‐level data or chart review.[18] For hospital‐based medicine units, an understanding of the structure‐ and process‐related factors associated with events is required for quality improvement efforts. Although the primary focus for this work was the off hours, it is plausible that providers may have identified similar issues as important issues during daytime hours. Our study was not designed to investigate if these perceived issues are specific to off hours, or if these issues are an accurate reflection of objective events occurring during this time period. We believe this topic deserves further investigation, as understanding if these off‐hours perceptions are unique to this time period would change the scope of future quality improvement initiatives.

The most significant finding in the quantitative results was the vulnerability in quality and safety during patient admissions from the ED, specifically in relation to communication and timeliness of transfer. Between‐unit handoffs for patients admitted from the ED to medicine units have been identified as particularly vulnerable to breakdowns in the communication process.[19, 20, 21, 22] There are multiple etiologies, including clinical uncertainty, higher acuity in patient illness early in hospitalization, and cultural differences between services.[23] Additionally, patterns of communication and standardized handoff processes are often insufficient. In our hospital system, the transfer process relies primarily upon synchronous communication methods without standardized, asynchronous information exchange. We hypothesize front‐line providers perceive this lack of standardization as a primary threat to quality. Because approximately 60% of new patient admissions from the ED to medicine service (both in our hospital and in prior studies) occur during off hours, these findings highlight a need for subsequent study and quality improvement efforts.[24]

During the time of this study, our medicine units were staffed at night by 5 medicine housestaff physicians and 1 academic hospitalist, or nocturnist. In efforts to improve quality and safety during off hours, our hospital, as well as other health systems, implemented the nocturnist position, a faculty‐level attending physician to provide off‐hours clinical care and housestaff supervision.[25] Although participants reported a moderate rating of housestaff supervision, participants provided lower scores for staffing numbers of nurses, and housestaff and attending physicians, despite nocturnist presence. With both increased off‐hours supervision in our hospital and increasing use of faculty‐level physicians in other academic programs, these results provide context for the anticipated level of overnight housestaff supervision.[26, 27] To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate perceived overnight quality issues on medicine units following such staffing models. Although this model of direct, on‐site supervision in academic medicine programs may help offset staffing and supervisory issues during off hours, the nocturnist role is insufficient to offset threats to quality/safety already inherent within the system. Furthermore, prospective trials following implementation of nocturnist systems have shown mixed results in improving patient outcomes.[28] These findings have led some to question whether resources dedicated to nocturnist staffing may be better allocated to other overnight initiatives, highlighting the need for a more subtle understanding of quality issues to design targeted interventions.[29]

A notable finding from this work is that providers without night experience reported lower scores for 20 of 24 items, highlighting their perceptions of the quality of care delivery during off hours are lower than those who experience this environment. Although day providers are not directly experiencing off‐hours delivery processes, these providers receive and detect the results from care delivery at night.[17] Most nurse, physician, and hospital leaders are present in the hospital only during day hours, requiring these individuals to account for differences in perceived and actual care delivered overnight.[1] These individuals make critical decisions pertaining to process changes and quality improvement efforts in these units. We believe these results raise awareness for leadership decisions and quality improvement efforts in medicine service units, specifically to focus on overnight issues beyond staffing issues alone.

All respondent groups ranked the latter half of the shift (17 am) as lower in quality compared to the first 6 hours (7 pm1 am). This finding is contrary to our hypothesis that earlier time periods, during the majority of patient admissions (and presumed higher workload for all providers), would be perceived as lower quality. Reasons for this finding are unknown, but may relate to end‐of‐shift tasks, sign‐out preparation, provider fatigue, or disease‐related concerns (eg, increased incidence of stroke and myocardial infarction) during the latter portions of night shifts. One study identified a decrease in nursing clinical judgments from the beginning to end of 12‐hour shifts, with a potential suggested mechanism of decrease in ability to maintain attention during judgments.[30] Additionally, in a study by Folkard et al., risk was highest within the first several hours and fell substantially thereafter during a shift.[9] To our knowledge, no work has investigated perceived or objective quality outcomes by time period during the off‐hours shift in medicine units. Further work could help delineate why provider‐perceived compromises in quality occur late in off‐hours shifts and whether this correlates to safety events.

There are several limitations to our study. First, although all surveys were pilot tested for content validity, the construct validity was not rigorously assessed. Second, although data were collected from all participant groups, the collection methods were unbalanced, favoring attending‐level physician perspectives. Although the relative incidence of vulnerabilities in quality and safety should be interpreted with caution, our methods and general taxonomy provide a framework for developing and monitoring the perceptions of future interventions. Due to limitations in infrastructure, our findings could not be independently validated through review of reported adverse events, but previous investigations have found the vast majority of adverse events are not detected by standard anonymous reporting.[31, 32, 33] Our methodology (used in our prior work) may provide an independent means of detecting causes of poor quality not easily observed through routine surveillance.[22] Although many survey items showed statistical differences between provider groups, the clinical significance is subject to interpretation. Last, the perceptions and events related to our institution may not be fully generalizable to other academic programs or service lines, particularly in community‐based, nonteaching hospitals.

In conclusion, our results suggest a significant discrepancy between the concerns of day and night providers regarding the quality of care delivered to inpatients during the off hours, specifically with issues related to communication, quality‐of‐care delivery processes, and patient transfers from the ED. Although specific concerns may be institution‐ (and service line‐) dependent, appropriately designing initiatives to improve the quality of care delivered overnight will need to take the perspectives of both provider groups into account. Additionally, educational initiatives should focus on achieving a shared mental model among all providers to improve collaboration and performance.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the nurses, internal medicine housestaff physicians, and general internal medicine attending physicians at the Penn State Hershey Medical Center for their participation in this study.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- . Like night and day—shedding light on off‐hours care. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(20):2091–2093.

- , , , . Call nights and patient care. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(4):405–410.

- , , , et al. Uncovering system errors using a rapid response team: cross‐coverage caught in the crossfire. Discussion. J Trauma. 2009;67(1):173–179.

- , . The impact of shift work on the risk and severity of injuries for hospital employees: an analysis using Oregon workers' compensation data. Occup Med (Lond). 2004;54(8):556–563.

- , . Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(9):663–668.

- , , , et al. The association of shift‐level nurse staffing with adverse patient events. J Nurs Adm. 2011;41(2):64–70.

- , , , et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;121(7):e46–e215.

- , , , , O'Neil E. Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios In California Acute Care Hospitals. Oakland, CA: California Workforce Initiative; 2000.

- , . Shift work, safety and productivity. Occup Med (Lond). 2003;53(2):95–101.

- , , . Increased injuries on night shift. Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1137–1139.

- , . Shift and night work and long working hours‐a systematic review of safety implications. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011:37(3):173–185.

- , , , et al. Rotating shift work, sleep, and accidents related to sleepiness in hospital nurses. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(7):1011–1014.

- , , , et al. Survival from in‐hospital cardiac arrest during nights and weekends. JAMA. 2008;299(7):785–792.

- , , , , . The influence of shared mental models on team process and performance. J Appl Psychol. 2000;85(2):273.

- , . Team mental models and their potential to improve teamwork and safety: a review and implications for future research in healthcare. Saf Sci. 2012;50(5):1344–1354.

- . Editorial: mapping the field of mixed methods research. J Mix Methods Res. 2009;3(2):95–108.

- , . Decreasing adverse events through night talks: an interdisciplinary, hospital‐based quality improvement project. Perm J. Fall 2009;13(4):16–22.

- , , , et al. “Global trigger tool” shows that adverse events in hospitals may be ten times greater than previously measured. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(4):581–589.

- , , , , , . Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6):701–710.e704.

- . Smoothing transitions. Joint Commission targets patient handoffs. Mod Healthc. 2010;40(43):8–9.

- , , , , , . The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):411–418.

- , , , , , . Patient care transitions from the emergency department to the medicine ward: evaluation of a standardized electronic signout tool. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(4):337–347.

- , . The unappreciated challenges of between‐unit handoffs: negotiating and coordinating across boundaries. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61(2):155–160.

- , , , , , . The association between night or weekend admission and hospitalization‐relevant patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(1):10–14.

- . Middle‐of‐the‐night medicine is rarely patient‐centred. CMAJ. 2011;183(13):1467–1468.

- , , , et al. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):521–523.

- , , , , , . Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision‐making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610.

- , , , et al. A randomized trial of nighttime physician staffing in an intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(23):2201–2209.

- . Intensivists at night: putting resources in the right place. Crit Care. 2013;17(5):1008.

- , , . Changes in nurses' decision making during a 12‐h day shift. Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63(1):60–65.

- , , , , , . The incident reporting system does not detect adverse drug events: a problem for quality improvement. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1995;21(10):541–548.

- , , , , . An evaluation of adverse incident reporting. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999;5(1):5–12.

- , . Reporting and preventing medical mishaps: lessons from non‐medical near miss reporting systems. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):759–763.

Patients experience acute illness at all hours of the day. In acute care hospitals, over 60% of patient admissions occur outside of normal business hours, or the off hours.[1, 2] Similarly, the acute decompensation of patients already admitted to hospital‐based units is frequent, with 90% of rapid responses occurring between 9 pm and 6 am.[3] Research suggests worse hospital performance during off hours, including increased patient falls, in‐hospital cardiac arrest mortality, and severity of hospital employee injuries.[2, 4, 5, 6, 7]

Although hospital‐based services should match care demand, the disparity between patient acuity and hospital capability at night is significant. Off hours typically have lower staffing of nurses, and attending and housestaff physicians, and ancillary staff as well as limited availability of consultative and supportive services.[8] Additionally, off‐hours providers are subject to the physiological effects of imbalanced circadian rhythms, including fatigue, attenuating their abilities to provide high‐quality care. The significant patient care needs mandate continuous patient care delivery without compromising quality or safety. To achieve this, further defining the barriers to delivering quality care during off hours is essential to improvement efforts in medicine‐based units.

Previous investigations have found increased occurrence and severity of worker accidents, increased potential for higher occurrence of preventable adverse patient events, and decreased performance during off hours.[4, 9, 10] Additionally, detrimental effects of off‐hours care may be further magnified by rotating employees through both day and night shifts, a common practice in academic hospitals.[11, 12] Potentially modifiable outcomes, such as patient fall rate and in‐hospital cardiac arrest survival differ markedly between day and night shifts.[6, 13] These studies primarily report on specific diseases, such as myocardial infarction and stroke, and are investigated from the perspective of hospital‐level outcomes.

To our knowledge, no study has reported provider‐perceived quality and safety issues occurring during off hours in an academic setting. Likewise, although off‐hours collaborative care requires shared, interprofessional conceptualization regarding care delivery, this perspective has not been reported. Understanding the similarities and differences between provider perceptions will allow the construction of an interprofessional team mental model, facilitating the design of future quality improvement initiatives.[14, 15] Our objectives were to: (1) identify off‐hours quality and safety issues, (2) assess which issues are perceived as most significant, and (3) evaluate differences in perceptions of these issues between nurses, and attending and housestaff physicians.

METHODS

Study Design

To investigate quality and safety issues occurring during off hours, we employed a prospective, mixed‐methods sequential exploratory study design, involving an initial qualitative analysis of adverse events followed by quantitative survey assessment.[16] We chose a mixed‐methods approach because provider‐perceived off‐hours issues had not been explicitly identified in the literature, requiring preliminary qualitative assessment. For the purpose of this study, we defined off hours as the 7 pm to 7am time period, which overlapped night shifts for both nurses and physicians. The study was approved by the institutional review board as a quality improvement project.

Study Setting

The study was conducted at a 378‐bed, university‐based acute care hospital in central Pennsylvania. There are a total of 64 internal medicine beds located in 2 units: a general medicine unit (44 beds, staffed by 60 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:4) and an intermediate care unit (20 beds, staffed by 41 nurses, nurse‐to‐patient ratio 1:3). The medicine residency program consists of 69 residents and 14 combined internal medicinepediatrics residents. During the day, 3 teaching teams and 1 nonteaching team care for all medicine patients. Overnight, 3 junior/senior level residents admit patients to the medicine service, whereas 2 interns provide cross‐coverage for all medicine and specialty service patients. Starting in September 2012 (before data collection), an overnight faculty‐level academic hospitalist, or nocturnist, provided on‐site housestaff supervision.

Qualitative Data Collection

For the qualitative analysis, we used 2 methods to develop our database. First, we created an electronic survey (see Supporting Information, Appendix 1, in the online version of this article) to identify near misses/adverse events occurring overnight, distributed to the nocturnist, 3 daytime hospitalists, and unit charge nurses following each shift (October 2012March 2013). The survey items were developed for the purpose of this study, with several items modified from a previously published survey.[17] Second, residency program directors recorded field notes during end‐of‐rotation debriefings (1 hour) with departing overnight housestaff, which were then dictated and transcribed. The subsequent analysis from these sources informed the quantitative survey (see Supporting Information, Appendix 2, in the online version of this article).

Survey Instrument

Three months after the initiation of qualitative data collection, 1 investigator (J.D.G.) developed a preliminary codebook to identify categories and themes. From this codebook, the research team drafted a survey instrument (the complete qualitative analysis occurred after survey development). To maintain focus on systematic quality improvement, items related to perceived mismanagement, relationship tensions, and professionalism were excluded. The survey was pilot‐tested with 5 faculty physicians and 2 nursing staff, prompting several modifications to improve clarity. Primary demographic items included provider role (nurse, attending physician, or housestaff physician) and years in current role. The 24 survey items were grouped into 5 different categories: (1) Quality of Care Delivery, (2) Communication and Coordination, (3) Staffing and Supervision, (4) Patient Transfers, and (5) Consulting Service Issues. Each item was investigated on a 7‐point scale (1=lowest rating, 7=highest rating). Descriptive text was provided at the extremes (choices 1 and 7), whereas intermediary values (26) did not have descriptive cues. The descriptive anchors for Quality of Care Delivery and Patient Transfers were 1=never and 7=always, whereas the descriptive anchors Communication and Coordination and Staffing and Supervision were 1=poor and 7=superior; Consulting Service Issues used a mix of both. Providers with off‐hours experience were asked to rank 4 time periods (710 pm, 10 pm1 am, 14 am, 47 am) regarding quality of care delivery in the medicine units (1=best, 4=worst). We asked both daytime and nighttime providers about perceptions of off‐hours care because, given the boundary spanning the nature of medical care across work shifts, daytime providers frequently identify issues not apparent until hours (or even days) after completion of a night shift. A similar design was used in prior work investigating safety at night.[17]

Quantitative Data Collection

In June of 2013, we emailed a survey link (

Data Analysis

Using the preliminary codebook, 2 investigators (J.D.G., E.M.) jointly analyzed a segment of the dataset using Atlas.ti 6.0 (Scientific Software, Berlin, Germany). Two investigators independently coded the data, compared codes for agreement, and updated the codebook. The remaining data were coded independently, with regular adjudication sessions to modify the codebook. All investigators reviewed and agreed upon themes and representative quotations.

Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation statistics, Kruskal‐Wallis tests, and signed rank tests (with Bonferroni correction) were used to report group characteristics, correlate rank order, make comparisons between groups (nursing staff, and attending and housestaff physicians; day/night providers), and compare quality rankings by time period, respectively. The data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Stata/IC‐8 (StataCorp, College Park, TX).

RESULTS

Qualitative Analysis of Off‐Hours' Adverse Events and Near Misses

A total of 190 events were reported by daytime attending physicians (n=100), nocturnists (n=60), and nighttime charge nurses (n=30). Although questions asked participants to describe near misses/adverse events, respondents also reported a number of global quality issues not related to specific events. Similarly, debriefing sessions with housestaff (n=5) addressed both specific overnight events and residency‐related issues. Seven themes were identified: (1) perceived mismanagement, (2) quality of delivery processes, (3) communication and coordination, (4) staffing and supervision, (5) patient transfers, (6) consulting service issues, and, (7) professionalism/relational tensions. Table 1 lists the code frequencies and exemplary quotations.

| Category and Themes | Code Frequency No. (% of 322) | Representative Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Perceived mismanagement | 97 (30) | We had a new admission to the general medicine unit with atrial flutter and rapid ventricular response who did not receive rate controlling agents but rather received diuretics. [The patient's] heart rate remained between 110 and 130 overnight, with a troponin rise in the am likely from demand. The attending note states rate controllers and discussed with housestaff, but this was not performed. |

| Quality of delivery processes | 63 (20) | One patient had a delay in MRI scanning in the off hours due to the scanner being down and scheduling. When the patient went down, there seemed to be little attempt to make sure patient went through scanner; unclear if housestaff called or not to come to assist. Now, the delay in care is even further along. |