User login

EWRS for Sepsis

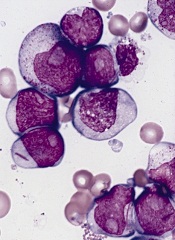

There are as many as 3 million cases of severe sepsis and 750,000 resulting deaths in the United States annually.[1] Interventions such as goal‐directed resuscitation and antibiotics can reduce sepsis mortality, but their effectiveness depends on early administration. Thus, timely recognition is critical.[2, 3, 4, 5]

Despite this, early recognition in hospitalized patients can be challenging. Using chart documentation as a surrogate for provider recognition, we recently found only 20% of patients with severe sepsis admitted to our hospital from the emergency department were recognized.[6] Given these challenges, there has been increasing interest in developing automated systems to improve the timeliness of sepsis detection.[7, 8, 9, 10] Systems described in the literature have varied considerably in triggering criteria, effector responses, and study settings. Of those examining the impact of automated surveillance and response in the nonintensive care unit (ICU) acute inpatient setting, results suggest an increase in the timeliness of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions,[10] but less impact on patient outcomes.[7] Whether these results reflect inadequacies in the criteria used to identify patients (parameters or their thresholds) or an ineffective response to the alert (magnitude or timeliness) is unclear.

Given the consequences of severe sepsis in hospitalized patients, as well as the introduction of vital sign (VS) and provider data in our electronic health record (EHR), we sought to develop and implement an electronic sepsis detection and response system to improve patient outcomes. This study describes the development, validation, and impact of that system.

METHODS

Setting and Data Sources

The University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) includes 3 hospitals with a capacity of over 1500 beds and 70,000 annual admissions. All hospitals use the EHR Sunrise Clinical Manager version 5.5 (Allscripts, Chicago, IL). The study period began in October 2011, when VS and provider contact information became available electronically. Data were retrieved from the Penn Data Store, which includes professionally coded data as well as clinical data from our EHRs. The study received expedited approval and a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver from our institutional review board.

Development of the Intervention

The early warning and response system (EWRS) for sepsis was designed to monitor laboratory values and VSs in real time in our inpatient EHR to detect patients at risk for clinical deterioration and development of severe sepsis. The development team was multidisciplinary, including informaticians, physicians, nurses, and data analysts from all 3 hospitals.

To identify at‐risk patients, we used established criteria for severe sepsis, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria (temperature <36C or >38C, heart rate >90 bpm, respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <32 mm Hg, and total white blood cell count <4000 or >12,000 or >10% bands) coupled with criteria suggesting organ dysfunction (cardiovascular dysfunction based on a systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg, and hypoperfusion based on a serum lactate measure >2.2 mmol/L [the threshold for an abnormal result in our lab]).[11, 12]

To establish a threshold for triggering the system, a derivation cohort was used and defined as patients admitted between October 1, 2011 to October 31, 2011 1 to any inpatient acute care service. Those <18 years old or admitted to hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. We calculated a risk score for each patient, defined as the sum of criteria met at any single time during their visit. At any given point in time, we used the most recent value for each criteria, with a look‐back period of 24 hours for VSs and 48 hours for labs. The minimum and maximum number of criteria that a patient could achieve at any single time was 0 and 6, respectively. We then categorized patients by the maximum number of criteria achieved and estimated the proportion of patients in each category who: (1) were transferred to an ICU during their hospital visit; (2) had a rapid response team (RRT) called during their visit; (3) died during their visit; (4) had a composite of 1, 2, or 3; or (5) were coded as sepsis at discharge (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article for further information). Once a threshold was chosen, we examined the time from first trigger to: (1) any ICU transfer; (2) any RRT; (3) death; or (4) a composite of 1, 2, or 3. We then estimated the screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios of the specified threshold.

The efferent response arm of the EWRS included the covering provider (usually an intern), the bedside nurse, and rapid response coordinators, who were engaged from the outset in developing the operational response to the alert. This team was required to perform a bedside evaluation within 30 minutes of the alert, and enact changes in management if warranted. The rapid response coordinator was required to complete a 3‐question follow‐up assessment in the EHR asking whether all 3 team members gathered at the bedside, the most likely condition triggering the EWRS, and whether management changed (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). To minimize the number of triggers, once a patient triggered an alert, any additional alert triggers during the same hospital stay were censored.

Implementation of the EWRS

All inpatients on noncritical care services were screened continuously. Hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. If a patient met the EWRS criteria threshold, an alert was sent to the covering provider and rapid response coordinator by text page. The bedside nurses, who do not carry text‐enabled devices, were alerted by pop‐up notification in the EHR (see Supporting Figure 2 in the online version of this article). The notification was linked to a task that required nurses to verify in the EHR the VSs triggering the EWRS, and adverse trends in VSs or labs (see Supporting Figure 3 in the online version of this article).

The Preimplementation (Silent) Period and EWRS Validation

The EWRS was initially activated for a preimplementation silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) to both validate the tool and provide the baseline data to which the postimplementation period was compared. During this time, new admissions could trigger the alert, but notifications were not sent. We used admissions from the first 30 days of the preimplementation period to estimate the tool's screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios.

The Postimplementation (Live) Period and Impact Analysis

The EWRS went live September 12, 2012, upon which new admissions triggering the alert would result in a notification and response. Unadjusted analyses using the [2] test for dichotomous variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables compared demographics and the proportion of clinical process and outcome measures for those admitted during the silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) and a similar timeframe 1 year later when the intervention was live (June 6, 2013September 4, 2013). To be included in either of the time periods, patients had to trigger the alert during the period and be discharged within 45 days of the end of the period. The pre‐ and post‐sepsis mortality index was also examined (see the Supporting Information in the online version of this article for a detailed description of study measures). Multivariable regression models estimated the impact of the EWRS on the process and outcome measures, adjusted for differences between the patients in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods with respect to age, gender, Charlson index on admission, admitting service, hospital, and admission month. Logistic regression models examined dichotomous variables. Continuous variables were log transformed and examined using linear regression models. Cox regression models explored time to ICU transfer from trigger. Among patients with sepsis, a logistic regression model was used to compare the odds of mortality between the silent and live periods, adjusted for expected mortality, both within each hospital and across all hospitals.

Because there is a risk of providers becoming overly reliant on automated systems and overlooking those not triggering the system, we also examined the discharge disposition and mortality outcomes of those in both study periods not identified by the EWRS.

The primary analysis examined the impact of the EWRS across UPHS; we also examined the EWRS impact at each of our hospitals. Last, we performed subgroup analyses examining the EWRS impact in those assigned an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision code for sepsis at discharge or death. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In the derivation cohort, 4575 patients met the inclusion criteria. The proportion of those in each category (06) achieving our outcomes of interest are described in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article. We defined a positive trigger as a score 4, as this threshold identified a limited number of patients (3.9% [180/4575]) with a high proportion experiencing our composite outcome (25.6% [46/180]). The proportion of patients with an EWRS score 4 and their time to event by hospital and health system is described in Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article. Those with a score 4 were almost 4 times as likely to be transferred to the ICU, almost 7 times as likely to experience an RRT, and almost 10 times as likely to die. The screen positive, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios using this threshold and our composite outcome in the derivation cohort were 6%, 16%, 97%, 26%, 94%, 5.3, and 0.9, respectively, and in our validation cohort were 6%, 17%, 97%, 28%, 95%, 5.7, and 0.9, respectively.

In the preimplementation period, 3.8% of admissions (595/15,567) triggered the alert, as compared to 3.5% (545/15,526) in the postimplementation period. Demographics were similar across periods, except that in the postimplementation period patients were slightly younger and had a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index at admission (Table 1). The distribution of alerts across medicine and surgery services were similar (Table 1).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of encounters | 15,567 | 15,526 | |

| No. of alerts | 595 (4%) | 545 (4%) | 0.14 |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 62.0 (48.570.5) | 59.7 (46.169.6) | 0.04 |

| Female | 298 (50%) | 274 (50%) | 0.95 |

| Race | |||

| White | 343 (58%) | 312 (57%) | 0.14 |

| Black | 207 (35%) | 171 (31%) | |

| Other | 23 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Unknown | 22 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Admission type | |||

| Elective | 201 (34%) | 167 (31%) | 0.40 |

| ED | 300 (50%) | 278 (51%) | |

| Transfer | 94 (16%) | 99 (18%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 27.0 (23.032.0) | 26.0 (22.031.0) | 0.24 |

| Previous ICU admission | 137 (23%) | 127 (23%) | 0.91 |

| RRT before alert | 27 (5%) | 20 (4%) | 0.46 |

| Admission Charlson index, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 0.04 |

| Admitting service | |||

| Medicine | 398 (67%) | 364 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 173 (29%) | 169 (31%) | |

| Other | 24 (4%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Service where alert fired | |||

| Medicine | 391 (66%) | 365 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 175 (29%) | 164 (30%) | |

| Other | 29 (5%) | 15 (3%) | |

In our postimplementation period, 99% of coordinator pages and over three‐fourths of provider notifications were sent successfully. Almost three‐fourths of nurses reviewed the initial alert notification, and over 99% completed the electronic data verification and adverse trend review, with over half documenting adverse trends. Ninety‐five percent of the time the coordinators completed the follow‐up assessment. Over 90% of the time, the entire team evaluated the patient at bedside within 30 minutes. Almost half of the time, the team thought the patient had no critical illness. Over a third of the time, they thought the patient had sepsis, but reported over 90% of the time that they were aware of the diagnosis prior to the alert. (Supporting Table 3 in the online version of this article includes more details about the responses to the electronic notifications and follow‐up assessments.)

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, ordering of antibiotics, intravenous fluid boluses, and lactate and blood cultures within 3 hours of the trigger increased significantly, as did ordering of blood products, chest radiographs, and cardiac monitoring within 6 hours of the trigger (Tables 2 and 3).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | |

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 142 (26%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 75 (13%) | 123 (23%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 61 (10%) | 85 (16%) | <0.01 |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 57 (10%) | 128 (23%) | <0.01 |

| Blood culture order <3 h after alert | 68 (11%) | 99 (18%) | <0.01 |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 53 (9%) | 59 (11%) | 0.28 |

| CBC or BMP <6 h after alert | 247 (42%) | 219 (40%) | 0.65 |

| Vasopressor <6 h after alert | 17 (3%) | 21 (4%) | 0.35 |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 64 (12%) | 0.92 |

| RBC, plasma, or platelet transfusion order <6 h after alert | 31 (5%) | 52 (10%) | <0.01 |

| Naloxone order <6 h after alert | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.30 |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 35 (6%) | 0.70 |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 28 (5%) | 0.58 |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 113 (21%) | 0.02 |

| CT head, chest, or ABD <6 h after alert | 29 (5%) | 34 (6%) | 0.31 |

| Cardiac monitoring (ECG or telemetry) <6 h after alert | 70 (12%) | 90 (17%) | 0.02 |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | |

| ||||

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 1.93 (1.442.58) | 1.93 (1.432.61) | 1.64 (1.112.43) | 1.65 (1.102.47) |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 2.02 (1.482.77) | 2.02 (1.462.78) | 1.99 (1.323.00) | 2.02 (1.323.09) |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 1.62 (1.142.30) | 1.57 (1.102.25) | 1.63 (1.052.53) | 1.65 (1.052.58) |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 2.90 (2.074.06) | 3.11 (2.194.41) | 2.41 (1.583.67) | 2.79 (1.794.34) |

| Blood culture <3 h after alert | 1.72 (1.232.40) | 1.76 (1.252.47) | 1.36 (0.872.10) | 1.40 (0.902.20) |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 1.24 (0.841.83) | 1.32 (0.891.97) | 1.06 (0.631.77) | 1.13 (0.671.92) |

| BMP or CBC order <6 h after alert | 0.95 (0.751.20) | 0.96 (0.751.21) | 1.00 (0.701.44) | 1.04 (0.721.50) |

| Vasopressor order <6 h after alert | 1.36 (0.712.61) | 1.47 (0.762.83) | 1.32 (0.583.04) | 1.38 (0.593.25) |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 0.98 (0.691.41) | 1.02 (0.701.47) | 1.13 (0.641.99) | 1.17 (0.652.10) |

| Transfusion order <6 h after alert | 1.92 (1.213.04) | 1.95 (1.233.11) | 1.65 (0.913.01) | 1.68 (0.913.10) |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 1.10 (0.681.78) | 1.20 (0.722.00) | 0.38 (0.131.08) | 0.39 (0.121.20) |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 0.87 (0.521.44) | 0.93 (0.561.57) | 1.63 (0.634.21) | 1.87 (0.705.00) |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 1.43 (1.061.94) | 1.47 (1.081.99) | 1.45 (0.942.24) | 1.56 (1.002.43) |

| CT <6 h after alert | 1.30 (0.782.16) | 1.30 (0.782.19) | 0.97 (0.521.82) | 0.94 (0.491.79) |

| Cardiac monitoring <6 h after alert | 1.48 (1.062.08) | 1.54 (1.092.16) | 1.32 (0.792.18) | 1.44 (0.862.41) |

Hospital and ICU length of stay were similar in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods. There was no difference in the proportion of patients transferred to the ICU following the alert; however, the proportion transferred within 6 hours of the alert increased, and the time to ICU transfer was halved (see Supporting Figure 4 in the online version of this article), but neither change was statistically significant in unadjusted analyses. Transfer to the ICU within 6 hours became statistically significant after adjustment. All mortality measures were lower in the postimplementation period, but none reached statistical significance. Discharge to home and sepsis documentation were both statistically higher in the postimplementation period, but discharge to home lost statistical significance after adjustment (Tables 4 and 5) (see Supporting Table 4 in the online version of this article).

| Hospitals AC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | ||

| ||||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | ||

| Hospital LOS, d, median (IQR) | 10.1 (5.119.1) | 9.4 (5.218.9) | 0.92 | |

| ICU LOS after alert, d, median (IQR) | 3.4 (1.77.4) | 3.6 (1.96.8) | 0.72 | |

| ICU transfer <6 h after alert | 40 (7%) | 53 (10%) | 0.06 | |

| ICU transfer <24 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 79 (14%) | 0.20 | |

| ICU transfer any time after alert | 134 (23%) | 124 (23%) | 0.93 | |

| Time to first ICU after alert, h, median (IQR) | 21.3 (4.463.9) | 11.0 (2.358.7) | 0.22 | |

| RRT 6 h after alert | 13 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 0.51 | |

| Mortality of all patients | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | 0.45 | |

| Mortality 30 days after alert | 48 (8%) | 33 (6%) | 0.19 | |

| Mortality of those transferred to ICU | 40 (30%) | 32 (26%) | 0.47 | |

| Deceased or IP hospice | 94 (16%) | 72 (13%) | 0.22 | |

| Discharge to home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.04 | |

| Disposition location | ||||

| Home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.25 | |

| SNF | 89 (15%) | 65 (12%) | ||

| Rehab | 24 (4%) | 20 (4%) | ||

| LTC | 8 (1%) | 9 (2%) | ||

| Other hospital | 16 (3%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Expired | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | ||

| Hospice IP | 42 (7%) | 31 (6%) | ||

| Hospice other | 11 (2%) | 14 (3%) | ||

| Other location | 6 (1%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 230 (39%) | 247 (45%) | 0.02 | |

| Sepsis O/E | 1.37 | 1.06 | 0.18 | |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | |

| ||||

| Hospital LOS, d | 1.01 (0.921.11) | 1.02 (0.931.12) | 0.99 (0.851.15) | 1.00 (0.871.16) |

| ICU transfer | 1.49 (0.972.29) | 1.65 (1.072.55) | 1.61 (0.922.84) | 1.82 (1.023.25) |

| Time to first ICU transfer after alert, h‖ | 1.17 (0.871.57) | 1.23 (0.921.66) | 1.21 (0.831.75) | 1.31 (0.901.90) |

| ICU LOS, d | 1.01 (0.771.31) | 0.99 (0.761.28) | 0.87 (0.621.21) | 0.88 (0.641.21) |

| RRT | 0.75 (0.321.77) | 0.84 (0.352.02) | 0.81 (0.292.27) | 0.82 (0.272.43) |

| Mortality | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) |

| Mortality within 30 days of alert | 0.73 (0.461.16) | 0.87 (0.541.40) | 0.59 (0.341.04) | 0.69 (0.381.26) |

| Mortality or inpatient hospice transfer | 0.82 (0.471.41) | 0.78 (0.441.41) | 0.67 (0.361.25) | 0.65 (0.331.29) |

| Discharge to home | 1.29 (1.021.64) | 1.18 (0.911.52) | 1.36 (0.951.95) | 1.22 (0.811.84) |

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 1.32 (1.041.67) | 1.43 (1.101.85) | NA | NA |

In a subanalysis of EWRS impact on patients documented with sepsis at discharge, unadjusted and adjusted changes in clinical process and outcome measures across the time periods were similar to that of the total population (see Supporting Tables 5 and 6 and Supporting Figure 5 in the online version of this article). The unadjusted composite outcome of mortality or inpatient hospice was statistically lower in the postimplementation period, but lost statistical significance after adjustment.

The disposition and mortality outcomes of those not triggering the alert were unchanged across the 2 periods (see Supporting Tables 7, 8, and 9 in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that a predictive tool can accurately identify non‐ICU inpatients at increased risk for deterioration and death. In addition, we demonstrated the feasibility of deploying our EHR to screen patients in real time for deterioration and to trigger electronically a timely, robust, multidisciplinary bedside clinical evaluation. Compared to the control (silent) period, the EWRS resulted in a marked increase in early sepsis care, transfer to the ICU, and sepsis documentation, and an indication of a decreased sepsis mortality index and mortality, and increased discharge to home, although none of these latter 3 findings reached statistical significance.

Our study is unique in that it was implemented across a multihospital health system, which has identical EHRs, but diverse cultures, populations, staffing, and practice models. In addition, our study includes a preimplementation population similar to the postimplementation population (in terms of setting, month of admission, and adjustment for potential confounders).

Interestingly, patients identified by the EWRS who were subsequently transferred to an ICU had higher mortality rates (30% and 26% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) than those transferred to an ICU who were not identified by the EWRS (7% and 6% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) (Table 4) (see Supporting Table 7 in the online version of this article). This finding was robust to the study period, so is likely not related to the bedside evaluation prompted by the EWRS. It suggests the EWRS could help triage patients for appropriateness of ICU transfer, a particularly valuable role that should be explored further given the typical strains on ICU capacity,[13] and the mortality resulting from delays in patient transfers into ICUs.[14, 15]

Although we did not find a statistically significant mortality reduction, our study may have been underpowered to detect this outcome. Our study has other limitations. First, our preimplementation/postimplementation design may not fully account for secular changes in sepsis mortality. However, our comparison of similar time periods and our adjustment for observed demographic differences allow us to estimate with more certainty the change in sepsis care and mortality attributable to the intervention. Second, our study did not examine the effect of the EWRS on mortality after hospital discharge, where many such events occur. However, our capture of at least 45 hospital days on all study patients, as well as our inclusion of only those who died or were discharged during our study period, and our assessment of discharge disposition such as hospice, increase the chance that mortality reductions directly attributable to the EWRS were captured. Third, although the EWRS changed patient management, we did not assess the appropriateness of management changes. However, the impact of care changes was captured crudely by examining mortality rates and discharge disposition. Fourth, our study was limited to a single academic healthcare system, and our experience may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems with different EHRs and staff. However, the integration of our automated alert into a commercial EHR serving a diverse array of patient populations, clinical services, and service models throughout our healthcare system may improve the generalizability of our experience to other settings.

CONCLUSION

By leveraging readily available electronic data, an automated prediction tool identified at‐risk patients and mobilized care teams, resulting in more timely sepsis care, improved sepsis documentation, and a suggestion of reduced mortality. This alert may be scalable to other healthcare systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer Barger, MS, BSN, RN; Patty Baroni, MSN, RN; Patrick J. Donnelly, MS, RN, CCRN; Mika Epps, MSN, RN; Allen L. Fasnacht, MSN, RN; Neil O. Fishman, MD; Kevin M. Fosnocht, MD; David F. Gaieski, MD; Tonya Johnson, MSN, RN, CCRN; Craig R. Kean, MS; Arash Kia, MD, MS; Matthew D. Mitchell, PhD; Stacie Neefe, BSN, RN; Nina J. Renzi, BSN, RN, CCRN; Alexander Roederer, Jean C. Romano, MSN, RN, NE‐BC; Heather Ross, BSN, RN, CCRN; William D. Schweickert, MD; Esme Singer, MD; and Kendal Williams, MD, MPH for their help in developing, testing and operationalizing the EWRS examined in this study; their assistance in data acquisition; and for advice regarding data analysis. This study was previously presented as an oral abstract at the 2013 American Medical Informatics Association Meeting, November 1620, 2013, Washington, DC.

Disclosures: Dr. Umscheid's contribution to this project was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources, grant UL1RR024134, which is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000003. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no potential financial conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

- , , , . Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(5):1167–1174.

- , , , et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):580–637.

- , , , et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign: results of an international guideline‐based performance improvement program targeting severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(2):367–374.

- , , , et al. Early goal‐directed therapy in severe sepsis and septic shock revisited: concepts, controversies, and contemporary findings. Chest. 2006;130(5):1579–1595.

- , , , et al. Early goal‐directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(19):1368–1377.

- , , , , , . Severe sepsis cohorts derived from claims‐based strategies appear to be biased toward a more severely ill patient population. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(4):945–953.

- , , , et al. A trial of a real‐time alert for clinical deterioration in patients hospitalized on general medical wards. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):236–242.

- , , , , , . Bedside electronic capture of clinical observations and automated clinical alerts to improve compliance with an Early Warning Score protocol. Crit Care Resusc. 2011;13(2):83–88.

- , , , . Prospective trial of real‐time electronic surveillance to expedite early care of severe sepsis. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57(5):500–504.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a real‐time computerized sepsis alert in nonintensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(3):469–473.

- , , , et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–1655.

- , , , et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256.

- , , , , . Rationing critical care beds: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(7):1588–1597.

- . Delayed admission to intensive care unit for critically surgical patients is associated with increased mortality. Am J Surg. 2014;208:268–274.

- , , , et al. Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R28.

There are as many as 3 million cases of severe sepsis and 750,000 resulting deaths in the United States annually.[1] Interventions such as goal‐directed resuscitation and antibiotics can reduce sepsis mortality, but their effectiveness depends on early administration. Thus, timely recognition is critical.[2, 3, 4, 5]

Despite this, early recognition in hospitalized patients can be challenging. Using chart documentation as a surrogate for provider recognition, we recently found only 20% of patients with severe sepsis admitted to our hospital from the emergency department were recognized.[6] Given these challenges, there has been increasing interest in developing automated systems to improve the timeliness of sepsis detection.[7, 8, 9, 10] Systems described in the literature have varied considerably in triggering criteria, effector responses, and study settings. Of those examining the impact of automated surveillance and response in the nonintensive care unit (ICU) acute inpatient setting, results suggest an increase in the timeliness of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions,[10] but less impact on patient outcomes.[7] Whether these results reflect inadequacies in the criteria used to identify patients (parameters or their thresholds) or an ineffective response to the alert (magnitude or timeliness) is unclear.

Given the consequences of severe sepsis in hospitalized patients, as well as the introduction of vital sign (VS) and provider data in our electronic health record (EHR), we sought to develop and implement an electronic sepsis detection and response system to improve patient outcomes. This study describes the development, validation, and impact of that system.

METHODS

Setting and Data Sources

The University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) includes 3 hospitals with a capacity of over 1500 beds and 70,000 annual admissions. All hospitals use the EHR Sunrise Clinical Manager version 5.5 (Allscripts, Chicago, IL). The study period began in October 2011, when VS and provider contact information became available electronically. Data were retrieved from the Penn Data Store, which includes professionally coded data as well as clinical data from our EHRs. The study received expedited approval and a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver from our institutional review board.

Development of the Intervention

The early warning and response system (EWRS) for sepsis was designed to monitor laboratory values and VSs in real time in our inpatient EHR to detect patients at risk for clinical deterioration and development of severe sepsis. The development team was multidisciplinary, including informaticians, physicians, nurses, and data analysts from all 3 hospitals.

To identify at‐risk patients, we used established criteria for severe sepsis, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria (temperature <36C or >38C, heart rate >90 bpm, respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <32 mm Hg, and total white blood cell count <4000 or >12,000 or >10% bands) coupled with criteria suggesting organ dysfunction (cardiovascular dysfunction based on a systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg, and hypoperfusion based on a serum lactate measure >2.2 mmol/L [the threshold for an abnormal result in our lab]).[11, 12]

To establish a threshold for triggering the system, a derivation cohort was used and defined as patients admitted between October 1, 2011 to October 31, 2011 1 to any inpatient acute care service. Those <18 years old or admitted to hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. We calculated a risk score for each patient, defined as the sum of criteria met at any single time during their visit. At any given point in time, we used the most recent value for each criteria, with a look‐back period of 24 hours for VSs and 48 hours for labs. The minimum and maximum number of criteria that a patient could achieve at any single time was 0 and 6, respectively. We then categorized patients by the maximum number of criteria achieved and estimated the proportion of patients in each category who: (1) were transferred to an ICU during their hospital visit; (2) had a rapid response team (RRT) called during their visit; (3) died during their visit; (4) had a composite of 1, 2, or 3; or (5) were coded as sepsis at discharge (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article for further information). Once a threshold was chosen, we examined the time from first trigger to: (1) any ICU transfer; (2) any RRT; (3) death; or (4) a composite of 1, 2, or 3. We then estimated the screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios of the specified threshold.

The efferent response arm of the EWRS included the covering provider (usually an intern), the bedside nurse, and rapid response coordinators, who were engaged from the outset in developing the operational response to the alert. This team was required to perform a bedside evaluation within 30 minutes of the alert, and enact changes in management if warranted. The rapid response coordinator was required to complete a 3‐question follow‐up assessment in the EHR asking whether all 3 team members gathered at the bedside, the most likely condition triggering the EWRS, and whether management changed (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). To minimize the number of triggers, once a patient triggered an alert, any additional alert triggers during the same hospital stay were censored.

Implementation of the EWRS

All inpatients on noncritical care services were screened continuously. Hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. If a patient met the EWRS criteria threshold, an alert was sent to the covering provider and rapid response coordinator by text page. The bedside nurses, who do not carry text‐enabled devices, were alerted by pop‐up notification in the EHR (see Supporting Figure 2 in the online version of this article). The notification was linked to a task that required nurses to verify in the EHR the VSs triggering the EWRS, and adverse trends in VSs or labs (see Supporting Figure 3 in the online version of this article).

The Preimplementation (Silent) Period and EWRS Validation

The EWRS was initially activated for a preimplementation silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) to both validate the tool and provide the baseline data to which the postimplementation period was compared. During this time, new admissions could trigger the alert, but notifications were not sent. We used admissions from the first 30 days of the preimplementation period to estimate the tool's screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios.

The Postimplementation (Live) Period and Impact Analysis

The EWRS went live September 12, 2012, upon which new admissions triggering the alert would result in a notification and response. Unadjusted analyses using the [2] test for dichotomous variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables compared demographics and the proportion of clinical process and outcome measures for those admitted during the silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) and a similar timeframe 1 year later when the intervention was live (June 6, 2013September 4, 2013). To be included in either of the time periods, patients had to trigger the alert during the period and be discharged within 45 days of the end of the period. The pre‐ and post‐sepsis mortality index was also examined (see the Supporting Information in the online version of this article for a detailed description of study measures). Multivariable regression models estimated the impact of the EWRS on the process and outcome measures, adjusted for differences between the patients in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods with respect to age, gender, Charlson index on admission, admitting service, hospital, and admission month. Logistic regression models examined dichotomous variables. Continuous variables were log transformed and examined using linear regression models. Cox regression models explored time to ICU transfer from trigger. Among patients with sepsis, a logistic regression model was used to compare the odds of mortality between the silent and live periods, adjusted for expected mortality, both within each hospital and across all hospitals.

Because there is a risk of providers becoming overly reliant on automated systems and overlooking those not triggering the system, we also examined the discharge disposition and mortality outcomes of those in both study periods not identified by the EWRS.

The primary analysis examined the impact of the EWRS across UPHS; we also examined the EWRS impact at each of our hospitals. Last, we performed subgroup analyses examining the EWRS impact in those assigned an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision code for sepsis at discharge or death. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In the derivation cohort, 4575 patients met the inclusion criteria. The proportion of those in each category (06) achieving our outcomes of interest are described in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article. We defined a positive trigger as a score 4, as this threshold identified a limited number of patients (3.9% [180/4575]) with a high proportion experiencing our composite outcome (25.6% [46/180]). The proportion of patients with an EWRS score 4 and their time to event by hospital and health system is described in Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article. Those with a score 4 were almost 4 times as likely to be transferred to the ICU, almost 7 times as likely to experience an RRT, and almost 10 times as likely to die. The screen positive, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios using this threshold and our composite outcome in the derivation cohort were 6%, 16%, 97%, 26%, 94%, 5.3, and 0.9, respectively, and in our validation cohort were 6%, 17%, 97%, 28%, 95%, 5.7, and 0.9, respectively.

In the preimplementation period, 3.8% of admissions (595/15,567) triggered the alert, as compared to 3.5% (545/15,526) in the postimplementation period. Demographics were similar across periods, except that in the postimplementation period patients were slightly younger and had a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index at admission (Table 1). The distribution of alerts across medicine and surgery services were similar (Table 1).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of encounters | 15,567 | 15,526 | |

| No. of alerts | 595 (4%) | 545 (4%) | 0.14 |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 62.0 (48.570.5) | 59.7 (46.169.6) | 0.04 |

| Female | 298 (50%) | 274 (50%) | 0.95 |

| Race | |||

| White | 343 (58%) | 312 (57%) | 0.14 |

| Black | 207 (35%) | 171 (31%) | |

| Other | 23 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Unknown | 22 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Admission type | |||

| Elective | 201 (34%) | 167 (31%) | 0.40 |

| ED | 300 (50%) | 278 (51%) | |

| Transfer | 94 (16%) | 99 (18%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 27.0 (23.032.0) | 26.0 (22.031.0) | 0.24 |

| Previous ICU admission | 137 (23%) | 127 (23%) | 0.91 |

| RRT before alert | 27 (5%) | 20 (4%) | 0.46 |

| Admission Charlson index, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 0.04 |

| Admitting service | |||

| Medicine | 398 (67%) | 364 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 173 (29%) | 169 (31%) | |

| Other | 24 (4%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Service where alert fired | |||

| Medicine | 391 (66%) | 365 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 175 (29%) | 164 (30%) | |

| Other | 29 (5%) | 15 (3%) | |

In our postimplementation period, 99% of coordinator pages and over three‐fourths of provider notifications were sent successfully. Almost three‐fourths of nurses reviewed the initial alert notification, and over 99% completed the electronic data verification and adverse trend review, with over half documenting adverse trends. Ninety‐five percent of the time the coordinators completed the follow‐up assessment. Over 90% of the time, the entire team evaluated the patient at bedside within 30 minutes. Almost half of the time, the team thought the patient had no critical illness. Over a third of the time, they thought the patient had sepsis, but reported over 90% of the time that they were aware of the diagnosis prior to the alert. (Supporting Table 3 in the online version of this article includes more details about the responses to the electronic notifications and follow‐up assessments.)

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, ordering of antibiotics, intravenous fluid boluses, and lactate and blood cultures within 3 hours of the trigger increased significantly, as did ordering of blood products, chest radiographs, and cardiac monitoring within 6 hours of the trigger (Tables 2 and 3).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | |

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 142 (26%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 75 (13%) | 123 (23%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 61 (10%) | 85 (16%) | <0.01 |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 57 (10%) | 128 (23%) | <0.01 |

| Blood culture order <3 h after alert | 68 (11%) | 99 (18%) | <0.01 |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 53 (9%) | 59 (11%) | 0.28 |

| CBC or BMP <6 h after alert | 247 (42%) | 219 (40%) | 0.65 |

| Vasopressor <6 h after alert | 17 (3%) | 21 (4%) | 0.35 |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 64 (12%) | 0.92 |

| RBC, plasma, or platelet transfusion order <6 h after alert | 31 (5%) | 52 (10%) | <0.01 |

| Naloxone order <6 h after alert | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.30 |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 35 (6%) | 0.70 |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 28 (5%) | 0.58 |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 113 (21%) | 0.02 |

| CT head, chest, or ABD <6 h after alert | 29 (5%) | 34 (6%) | 0.31 |

| Cardiac monitoring (ECG or telemetry) <6 h after alert | 70 (12%) | 90 (17%) | 0.02 |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | |

| ||||

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 1.93 (1.442.58) | 1.93 (1.432.61) | 1.64 (1.112.43) | 1.65 (1.102.47) |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 2.02 (1.482.77) | 2.02 (1.462.78) | 1.99 (1.323.00) | 2.02 (1.323.09) |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 1.62 (1.142.30) | 1.57 (1.102.25) | 1.63 (1.052.53) | 1.65 (1.052.58) |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 2.90 (2.074.06) | 3.11 (2.194.41) | 2.41 (1.583.67) | 2.79 (1.794.34) |

| Blood culture <3 h after alert | 1.72 (1.232.40) | 1.76 (1.252.47) | 1.36 (0.872.10) | 1.40 (0.902.20) |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 1.24 (0.841.83) | 1.32 (0.891.97) | 1.06 (0.631.77) | 1.13 (0.671.92) |

| BMP or CBC order <6 h after alert | 0.95 (0.751.20) | 0.96 (0.751.21) | 1.00 (0.701.44) | 1.04 (0.721.50) |

| Vasopressor order <6 h after alert | 1.36 (0.712.61) | 1.47 (0.762.83) | 1.32 (0.583.04) | 1.38 (0.593.25) |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 0.98 (0.691.41) | 1.02 (0.701.47) | 1.13 (0.641.99) | 1.17 (0.652.10) |

| Transfusion order <6 h after alert | 1.92 (1.213.04) | 1.95 (1.233.11) | 1.65 (0.913.01) | 1.68 (0.913.10) |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 1.10 (0.681.78) | 1.20 (0.722.00) | 0.38 (0.131.08) | 0.39 (0.121.20) |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 0.87 (0.521.44) | 0.93 (0.561.57) | 1.63 (0.634.21) | 1.87 (0.705.00) |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 1.43 (1.061.94) | 1.47 (1.081.99) | 1.45 (0.942.24) | 1.56 (1.002.43) |

| CT <6 h after alert | 1.30 (0.782.16) | 1.30 (0.782.19) | 0.97 (0.521.82) | 0.94 (0.491.79) |

| Cardiac monitoring <6 h after alert | 1.48 (1.062.08) | 1.54 (1.092.16) | 1.32 (0.792.18) | 1.44 (0.862.41) |

Hospital and ICU length of stay were similar in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods. There was no difference in the proportion of patients transferred to the ICU following the alert; however, the proportion transferred within 6 hours of the alert increased, and the time to ICU transfer was halved (see Supporting Figure 4 in the online version of this article), but neither change was statistically significant in unadjusted analyses. Transfer to the ICU within 6 hours became statistically significant after adjustment. All mortality measures were lower in the postimplementation period, but none reached statistical significance. Discharge to home and sepsis documentation were both statistically higher in the postimplementation period, but discharge to home lost statistical significance after adjustment (Tables 4 and 5) (see Supporting Table 4 in the online version of this article).

| Hospitals AC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | ||

| ||||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | ||

| Hospital LOS, d, median (IQR) | 10.1 (5.119.1) | 9.4 (5.218.9) | 0.92 | |

| ICU LOS after alert, d, median (IQR) | 3.4 (1.77.4) | 3.6 (1.96.8) | 0.72 | |

| ICU transfer <6 h after alert | 40 (7%) | 53 (10%) | 0.06 | |

| ICU transfer <24 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 79 (14%) | 0.20 | |

| ICU transfer any time after alert | 134 (23%) | 124 (23%) | 0.93 | |

| Time to first ICU after alert, h, median (IQR) | 21.3 (4.463.9) | 11.0 (2.358.7) | 0.22 | |

| RRT 6 h after alert | 13 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 0.51 | |

| Mortality of all patients | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | 0.45 | |

| Mortality 30 days after alert | 48 (8%) | 33 (6%) | 0.19 | |

| Mortality of those transferred to ICU | 40 (30%) | 32 (26%) | 0.47 | |

| Deceased or IP hospice | 94 (16%) | 72 (13%) | 0.22 | |

| Discharge to home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.04 | |

| Disposition location | ||||

| Home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.25 | |

| SNF | 89 (15%) | 65 (12%) | ||

| Rehab | 24 (4%) | 20 (4%) | ||

| LTC | 8 (1%) | 9 (2%) | ||

| Other hospital | 16 (3%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Expired | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | ||

| Hospice IP | 42 (7%) | 31 (6%) | ||

| Hospice other | 11 (2%) | 14 (3%) | ||

| Other location | 6 (1%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 230 (39%) | 247 (45%) | 0.02 | |

| Sepsis O/E | 1.37 | 1.06 | 0.18 | |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | |

| ||||

| Hospital LOS, d | 1.01 (0.921.11) | 1.02 (0.931.12) | 0.99 (0.851.15) | 1.00 (0.871.16) |

| ICU transfer | 1.49 (0.972.29) | 1.65 (1.072.55) | 1.61 (0.922.84) | 1.82 (1.023.25) |

| Time to first ICU transfer after alert, h‖ | 1.17 (0.871.57) | 1.23 (0.921.66) | 1.21 (0.831.75) | 1.31 (0.901.90) |

| ICU LOS, d | 1.01 (0.771.31) | 0.99 (0.761.28) | 0.87 (0.621.21) | 0.88 (0.641.21) |

| RRT | 0.75 (0.321.77) | 0.84 (0.352.02) | 0.81 (0.292.27) | 0.82 (0.272.43) |

| Mortality | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) |

| Mortality within 30 days of alert | 0.73 (0.461.16) | 0.87 (0.541.40) | 0.59 (0.341.04) | 0.69 (0.381.26) |

| Mortality or inpatient hospice transfer | 0.82 (0.471.41) | 0.78 (0.441.41) | 0.67 (0.361.25) | 0.65 (0.331.29) |

| Discharge to home | 1.29 (1.021.64) | 1.18 (0.911.52) | 1.36 (0.951.95) | 1.22 (0.811.84) |

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 1.32 (1.041.67) | 1.43 (1.101.85) | NA | NA |

In a subanalysis of EWRS impact on patients documented with sepsis at discharge, unadjusted and adjusted changes in clinical process and outcome measures across the time periods were similar to that of the total population (see Supporting Tables 5 and 6 and Supporting Figure 5 in the online version of this article). The unadjusted composite outcome of mortality or inpatient hospice was statistically lower in the postimplementation period, but lost statistical significance after adjustment.

The disposition and mortality outcomes of those not triggering the alert were unchanged across the 2 periods (see Supporting Tables 7, 8, and 9 in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that a predictive tool can accurately identify non‐ICU inpatients at increased risk for deterioration and death. In addition, we demonstrated the feasibility of deploying our EHR to screen patients in real time for deterioration and to trigger electronically a timely, robust, multidisciplinary bedside clinical evaluation. Compared to the control (silent) period, the EWRS resulted in a marked increase in early sepsis care, transfer to the ICU, and sepsis documentation, and an indication of a decreased sepsis mortality index and mortality, and increased discharge to home, although none of these latter 3 findings reached statistical significance.

Our study is unique in that it was implemented across a multihospital health system, which has identical EHRs, but diverse cultures, populations, staffing, and practice models. In addition, our study includes a preimplementation population similar to the postimplementation population (in terms of setting, month of admission, and adjustment for potential confounders).

Interestingly, patients identified by the EWRS who were subsequently transferred to an ICU had higher mortality rates (30% and 26% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) than those transferred to an ICU who were not identified by the EWRS (7% and 6% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) (Table 4) (see Supporting Table 7 in the online version of this article). This finding was robust to the study period, so is likely not related to the bedside evaluation prompted by the EWRS. It suggests the EWRS could help triage patients for appropriateness of ICU transfer, a particularly valuable role that should be explored further given the typical strains on ICU capacity,[13] and the mortality resulting from delays in patient transfers into ICUs.[14, 15]

Although we did not find a statistically significant mortality reduction, our study may have been underpowered to detect this outcome. Our study has other limitations. First, our preimplementation/postimplementation design may not fully account for secular changes in sepsis mortality. However, our comparison of similar time periods and our adjustment for observed demographic differences allow us to estimate with more certainty the change in sepsis care and mortality attributable to the intervention. Second, our study did not examine the effect of the EWRS on mortality after hospital discharge, where many such events occur. However, our capture of at least 45 hospital days on all study patients, as well as our inclusion of only those who died or were discharged during our study period, and our assessment of discharge disposition such as hospice, increase the chance that mortality reductions directly attributable to the EWRS were captured. Third, although the EWRS changed patient management, we did not assess the appropriateness of management changes. However, the impact of care changes was captured crudely by examining mortality rates and discharge disposition. Fourth, our study was limited to a single academic healthcare system, and our experience may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems with different EHRs and staff. However, the integration of our automated alert into a commercial EHR serving a diverse array of patient populations, clinical services, and service models throughout our healthcare system may improve the generalizability of our experience to other settings.

CONCLUSION

By leveraging readily available electronic data, an automated prediction tool identified at‐risk patients and mobilized care teams, resulting in more timely sepsis care, improved sepsis documentation, and a suggestion of reduced mortality. This alert may be scalable to other healthcare systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer Barger, MS, BSN, RN; Patty Baroni, MSN, RN; Patrick J. Donnelly, MS, RN, CCRN; Mika Epps, MSN, RN; Allen L. Fasnacht, MSN, RN; Neil O. Fishman, MD; Kevin M. Fosnocht, MD; David F. Gaieski, MD; Tonya Johnson, MSN, RN, CCRN; Craig R. Kean, MS; Arash Kia, MD, MS; Matthew D. Mitchell, PhD; Stacie Neefe, BSN, RN; Nina J. Renzi, BSN, RN, CCRN; Alexander Roederer, Jean C. Romano, MSN, RN, NE‐BC; Heather Ross, BSN, RN, CCRN; William D. Schweickert, MD; Esme Singer, MD; and Kendal Williams, MD, MPH for their help in developing, testing and operationalizing the EWRS examined in this study; their assistance in data acquisition; and for advice regarding data analysis. This study was previously presented as an oral abstract at the 2013 American Medical Informatics Association Meeting, November 1620, 2013, Washington, DC.

Disclosures: Dr. Umscheid's contribution to this project was supported in part by the National Center for Research Resources, grant UL1RR024134, which is now at the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000003. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no potential financial conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

There are as many as 3 million cases of severe sepsis and 750,000 resulting deaths in the United States annually.[1] Interventions such as goal‐directed resuscitation and antibiotics can reduce sepsis mortality, but their effectiveness depends on early administration. Thus, timely recognition is critical.[2, 3, 4, 5]

Despite this, early recognition in hospitalized patients can be challenging. Using chart documentation as a surrogate for provider recognition, we recently found only 20% of patients with severe sepsis admitted to our hospital from the emergency department were recognized.[6] Given these challenges, there has been increasing interest in developing automated systems to improve the timeliness of sepsis detection.[7, 8, 9, 10] Systems described in the literature have varied considerably in triggering criteria, effector responses, and study settings. Of those examining the impact of automated surveillance and response in the nonintensive care unit (ICU) acute inpatient setting, results suggest an increase in the timeliness of diagnostic and therapeutic interventions,[10] but less impact on patient outcomes.[7] Whether these results reflect inadequacies in the criteria used to identify patients (parameters or their thresholds) or an ineffective response to the alert (magnitude or timeliness) is unclear.

Given the consequences of severe sepsis in hospitalized patients, as well as the introduction of vital sign (VS) and provider data in our electronic health record (EHR), we sought to develop and implement an electronic sepsis detection and response system to improve patient outcomes. This study describes the development, validation, and impact of that system.

METHODS

Setting and Data Sources

The University of Pennsylvania Health System (UPHS) includes 3 hospitals with a capacity of over 1500 beds and 70,000 annual admissions. All hospitals use the EHR Sunrise Clinical Manager version 5.5 (Allscripts, Chicago, IL). The study period began in October 2011, when VS and provider contact information became available electronically. Data were retrieved from the Penn Data Store, which includes professionally coded data as well as clinical data from our EHRs. The study received expedited approval and a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver from our institutional review board.

Development of the Intervention

The early warning and response system (EWRS) for sepsis was designed to monitor laboratory values and VSs in real time in our inpatient EHR to detect patients at risk for clinical deterioration and development of severe sepsis. The development team was multidisciplinary, including informaticians, physicians, nurses, and data analysts from all 3 hospitals.

To identify at‐risk patients, we used established criteria for severe sepsis, including the systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria (temperature <36C or >38C, heart rate >90 bpm, respiratory rate >20 breaths/min or PaCO2 <32 mm Hg, and total white blood cell count <4000 or >12,000 or >10% bands) coupled with criteria suggesting organ dysfunction (cardiovascular dysfunction based on a systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg, and hypoperfusion based on a serum lactate measure >2.2 mmol/L [the threshold for an abnormal result in our lab]).[11, 12]

To establish a threshold for triggering the system, a derivation cohort was used and defined as patients admitted between October 1, 2011 to October 31, 2011 1 to any inpatient acute care service. Those <18 years old or admitted to hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. We calculated a risk score for each patient, defined as the sum of criteria met at any single time during their visit. At any given point in time, we used the most recent value for each criteria, with a look‐back period of 24 hours for VSs and 48 hours for labs. The minimum and maximum number of criteria that a patient could achieve at any single time was 0 and 6, respectively. We then categorized patients by the maximum number of criteria achieved and estimated the proportion of patients in each category who: (1) were transferred to an ICU during their hospital visit; (2) had a rapid response team (RRT) called during their visit; (3) died during their visit; (4) had a composite of 1, 2, or 3; or (5) were coded as sepsis at discharge (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article for further information). Once a threshold was chosen, we examined the time from first trigger to: (1) any ICU transfer; (2) any RRT; (3) death; or (4) a composite of 1, 2, or 3. We then estimated the screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios of the specified threshold.

The efferent response arm of the EWRS included the covering provider (usually an intern), the bedside nurse, and rapid response coordinators, who were engaged from the outset in developing the operational response to the alert. This team was required to perform a bedside evaluation within 30 minutes of the alert, and enact changes in management if warranted. The rapid response coordinator was required to complete a 3‐question follow‐up assessment in the EHR asking whether all 3 team members gathered at the bedside, the most likely condition triggering the EWRS, and whether management changed (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). To minimize the number of triggers, once a patient triggered an alert, any additional alert triggers during the same hospital stay were censored.

Implementation of the EWRS

All inpatients on noncritical care services were screened continuously. Hospice, research, and obstetrics services were excluded. If a patient met the EWRS criteria threshold, an alert was sent to the covering provider and rapid response coordinator by text page. The bedside nurses, who do not carry text‐enabled devices, were alerted by pop‐up notification in the EHR (see Supporting Figure 2 in the online version of this article). The notification was linked to a task that required nurses to verify in the EHR the VSs triggering the EWRS, and adverse trends in VSs or labs (see Supporting Figure 3 in the online version of this article).

The Preimplementation (Silent) Period and EWRS Validation

The EWRS was initially activated for a preimplementation silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) to both validate the tool and provide the baseline data to which the postimplementation period was compared. During this time, new admissions could trigger the alert, but notifications were not sent. We used admissions from the first 30 days of the preimplementation period to estimate the tool's screen positive rate, test characteristics, predictive values, and likelihood ratios.

The Postimplementation (Live) Period and Impact Analysis

The EWRS went live September 12, 2012, upon which new admissions triggering the alert would result in a notification and response. Unadjusted analyses using the [2] test for dichotomous variables and the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables compared demographics and the proportion of clinical process and outcome measures for those admitted during the silent period (June 6, 2012September 4, 2012) and a similar timeframe 1 year later when the intervention was live (June 6, 2013September 4, 2013). To be included in either of the time periods, patients had to trigger the alert during the period and be discharged within 45 days of the end of the period. The pre‐ and post‐sepsis mortality index was also examined (see the Supporting Information in the online version of this article for a detailed description of study measures). Multivariable regression models estimated the impact of the EWRS on the process and outcome measures, adjusted for differences between the patients in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods with respect to age, gender, Charlson index on admission, admitting service, hospital, and admission month. Logistic regression models examined dichotomous variables. Continuous variables were log transformed and examined using linear regression models. Cox regression models explored time to ICU transfer from trigger. Among patients with sepsis, a logistic regression model was used to compare the odds of mortality between the silent and live periods, adjusted for expected mortality, both within each hospital and across all hospitals.

Because there is a risk of providers becoming overly reliant on automated systems and overlooking those not triggering the system, we also examined the discharge disposition and mortality outcomes of those in both study periods not identified by the EWRS.

The primary analysis examined the impact of the EWRS across UPHS; we also examined the EWRS impact at each of our hospitals. Last, we performed subgroup analyses examining the EWRS impact in those assigned an International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision code for sepsis at discharge or death. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

In the derivation cohort, 4575 patients met the inclusion criteria. The proportion of those in each category (06) achieving our outcomes of interest are described in Supporting Table 1 in the online version of this article. We defined a positive trigger as a score 4, as this threshold identified a limited number of patients (3.9% [180/4575]) with a high proportion experiencing our composite outcome (25.6% [46/180]). The proportion of patients with an EWRS score 4 and their time to event by hospital and health system is described in Supporting Table 2 in the online version of this article. Those with a score 4 were almost 4 times as likely to be transferred to the ICU, almost 7 times as likely to experience an RRT, and almost 10 times as likely to die. The screen positive, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratios using this threshold and our composite outcome in the derivation cohort were 6%, 16%, 97%, 26%, 94%, 5.3, and 0.9, respectively, and in our validation cohort were 6%, 17%, 97%, 28%, 95%, 5.7, and 0.9, respectively.

In the preimplementation period, 3.8% of admissions (595/15,567) triggered the alert, as compared to 3.5% (545/15,526) in the postimplementation period. Demographics were similar across periods, except that in the postimplementation period patients were slightly younger and had a lower Charlson Comorbidity Index at admission (Table 1). The distribution of alerts across medicine and surgery services were similar (Table 1).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of encounters | 15,567 | 15,526 | |

| No. of alerts | 595 (4%) | 545 (4%) | 0.14 |

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 62.0 (48.570.5) | 59.7 (46.169.6) | 0.04 |

| Female | 298 (50%) | 274 (50%) | 0.95 |

| Race | |||

| White | 343 (58%) | 312 (57%) | 0.14 |

| Black | 207 (35%) | 171 (31%) | |

| Other | 23 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Unknown | 22 (4%) | 31 (6%) | |

| Admission type | |||

| Elective | 201 (34%) | 167 (31%) | 0.40 |

| ED | 300 (50%) | 278 (51%) | |

| Transfer | 94 (16%) | 99 (18%) | |

| BMI, kg/m2, median (IQR) | 27.0 (23.032.0) | 26.0 (22.031.0) | 0.24 |

| Previous ICU admission | 137 (23%) | 127 (23%) | 0.91 |

| RRT before alert | 27 (5%) | 20 (4%) | 0.46 |

| Admission Charlson index, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 2.0 (1.04.0) | 0.04 |

| Admitting service | |||

| Medicine | 398 (67%) | 364 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 173 (29%) | 169 (31%) | |

| Other | 24 (4%) | 12 (2%) | |

| Service where alert fired | |||

| Medicine | 391 (66%) | 365 (67%) | 0.18 |

| Surgery | 175 (29%) | 164 (30%) | |

| Other | 29 (5%) | 15 (3%) | |

In our postimplementation period, 99% of coordinator pages and over three‐fourths of provider notifications were sent successfully. Almost three‐fourths of nurses reviewed the initial alert notification, and over 99% completed the electronic data verification and adverse trend review, with over half documenting adverse trends. Ninety‐five percent of the time the coordinators completed the follow‐up assessment. Over 90% of the time, the entire team evaluated the patient at bedside within 30 minutes. Almost half of the time, the team thought the patient had no critical illness. Over a third of the time, they thought the patient had sepsis, but reported over 90% of the time that they were aware of the diagnosis prior to the alert. (Supporting Table 3 in the online version of this article includes more details about the responses to the electronic notifications and follow‐up assessments.)

In unadjusted and adjusted analyses, ordering of antibiotics, intravenous fluid boluses, and lactate and blood cultures within 3 hours of the trigger increased significantly, as did ordering of blood products, chest radiographs, and cardiac monitoring within 6 hours of the trigger (Tables 2 and 3).

| Hospitals AC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | |

| |||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | |

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 142 (26%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 75 (13%) | 123 (23%) | <0.01 |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 61 (10%) | 85 (16%) | <0.01 |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 57 (10%) | 128 (23%) | <0.01 |

| Blood culture order <3 h after alert | 68 (11%) | 99 (18%) | <0.01 |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 53 (9%) | 59 (11%) | 0.28 |

| CBC or BMP <6 h after alert | 247 (42%) | 219 (40%) | 0.65 |

| Vasopressor <6 h after alert | 17 (3%) | 21 (4%) | 0.35 |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 64 (12%) | 0.92 |

| RBC, plasma, or platelet transfusion order <6 h after alert | 31 (5%) | 52 (10%) | <0.01 |

| Naloxone order <6 h after alert | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0.30 |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 35 (6%) | 0.70 |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 35 (6%) | 28 (5%) | 0.58 |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 92 (15%) | 113 (21%) | 0.02 |

| CT head, chest, or ABD <6 h after alert | 29 (5%) | 34 (6%) | 0.31 |

| Cardiac monitoring (ECG or telemetry) <6 h after alert | 70 (12%) | 90 (17%) | 0.02 |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | Unadjusted Odds Ratio | Adjusted Odds Ratio | |

| ||||

| 500 mL IV bolus order <3 h after alert | 1.93 (1.442.58) | 1.93 (1.432.61) | 1.64 (1.112.43) | 1.65 (1.102.47) |

| IV/PO antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 2.02 (1.482.77) | 2.02 (1.462.78) | 1.99 (1.323.00) | 2.02 (1.323.09) |

| IV/PO sepsis antibiotic order <3 h after alert | 1.62 (1.142.30) | 1.57 (1.102.25) | 1.63 (1.052.53) | 1.65 (1.052.58) |

| Lactic acid order <3 h after alert | 2.90 (2.074.06) | 3.11 (2.194.41) | 2.41 (1.583.67) | 2.79 (1.794.34) |

| Blood culture <3 h after alert | 1.72 (1.232.40) | 1.76 (1.252.47) | 1.36 (0.872.10) | 1.40 (0.902.20) |

| Blood gas order <6 h after alert | 1.24 (0.841.83) | 1.32 (0.891.97) | 1.06 (0.631.77) | 1.13 (0.671.92) |

| BMP or CBC order <6 h after alert | 0.95 (0.751.20) | 0.96 (0.751.21) | 1.00 (0.701.44) | 1.04 (0.721.50) |

| Vasopressor order <6 h after alert | 1.36 (0.712.61) | 1.47 (0.762.83) | 1.32 (0.583.04) | 1.38 (0.593.25) |

| Bronchodilator administration <6 h after alert | 0.98 (0.691.41) | 1.02 (0.701.47) | 1.13 (0.641.99) | 1.17 (0.652.10) |

| Transfusion order <6 h after alert | 1.92 (1.213.04) | 1.95 (1.233.11) | 1.65 (0.913.01) | 1.68 (0.913.10) |

| AV node blocker order <6 h after alert | 1.10 (0.681.78) | 1.20 (0.722.00) | 0.38 (0.131.08) | 0.39 (0.121.20) |

| Loop diuretic order <6 h after alert | 0.87 (0.521.44) | 0.93 (0.561.57) | 1.63 (0.634.21) | 1.87 (0.705.00) |

| CXR <6 h after alert | 1.43 (1.061.94) | 1.47 (1.081.99) | 1.45 (0.942.24) | 1.56 (1.002.43) |

| CT <6 h after alert | 1.30 (0.782.16) | 1.30 (0.782.19) | 0.97 (0.521.82) | 0.94 (0.491.79) |

| Cardiac monitoring <6 h after alert | 1.48 (1.062.08) | 1.54 (1.092.16) | 1.32 (0.792.18) | 1.44 (0.862.41) |

Hospital and ICU length of stay were similar in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods. There was no difference in the proportion of patients transferred to the ICU following the alert; however, the proportion transferred within 6 hours of the alert increased, and the time to ICU transfer was halved (see Supporting Figure 4 in the online version of this article), but neither change was statistically significant in unadjusted analyses. Transfer to the ICU within 6 hours became statistically significant after adjustment. All mortality measures were lower in the postimplementation period, but none reached statistical significance. Discharge to home and sepsis documentation were both statistically higher in the postimplementation period, but discharge to home lost statistical significance after adjustment (Tables 4 and 5) (see Supporting Table 4 in the online version of this article).

| Hospitals AC | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation | Postimplementation | P Value | ||

| ||||

| No. of alerts | 595 | 545 | ||

| Hospital LOS, d, median (IQR) | 10.1 (5.119.1) | 9.4 (5.218.9) | 0.92 | |

| ICU LOS after alert, d, median (IQR) | 3.4 (1.77.4) | 3.6 (1.96.8) | 0.72 | |

| ICU transfer <6 h after alert | 40 (7%) | 53 (10%) | 0.06 | |

| ICU transfer <24 h after alert | 71 (12%) | 79 (14%) | 0.20 | |

| ICU transfer any time after alert | 134 (23%) | 124 (23%) | 0.93 | |

| Time to first ICU after alert, h, median (IQR) | 21.3 (4.463.9) | 11.0 (2.358.7) | 0.22 | |

| RRT 6 h after alert | 13 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 0.51 | |

| Mortality of all patients | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | 0.45 | |

| Mortality 30 days after alert | 48 (8%) | 33 (6%) | 0.19 | |

| Mortality of those transferred to ICU | 40 (30%) | 32 (26%) | 0.47 | |

| Deceased or IP hospice | 94 (16%) | 72 (13%) | 0.22 | |

| Discharge to home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.04 | |

| Disposition location | ||||

| Home | 347 (58%) | 351 (64%) | 0.25 | |

| SNF | 89 (15%) | 65 (12%) | ||

| Rehab | 24 (4%) | 20 (4%) | ||

| LTC | 8 (1%) | 9 (2%) | ||

| Other hospital | 16 (3%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Expired | 52 (9%) | 41 (8%) | ||

| Hospice IP | 42 (7%) | 31 (6%) | ||

| Hospice other | 11 (2%) | 14 (3%) | ||

| Other location | 6 (1%) | 8 (1%) | ||

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 230 (39%) | 247 (45%) | 0.02 | |

| Sepsis O/E | 1.37 | 1.06 | 0.18 | |

| All Alerted Patients | Discharged With Sepsis Code* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | Unadjusted Estimate | Adjusted Estimate | |

| ||||

| Hospital LOS, d | 1.01 (0.921.11) | 1.02 (0.931.12) | 0.99 (0.851.15) | 1.00 (0.871.16) |

| ICU transfer | 1.49 (0.972.29) | 1.65 (1.072.55) | 1.61 (0.922.84) | 1.82 (1.023.25) |

| Time to first ICU transfer after alert, h‖ | 1.17 (0.871.57) | 1.23 (0.921.66) | 1.21 (0.831.75) | 1.31 (0.901.90) |

| ICU LOS, d | 1.01 (0.771.31) | 0.99 (0.761.28) | 0.87 (0.621.21) | 0.88 (0.641.21) |

| RRT | 0.75 (0.321.77) | 0.84 (0.352.02) | 0.81 (0.292.27) | 0.82 (0.272.43) |

| Mortality | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) | 0.85 (0.551.30) | 0.98 (0.631.53) |

| Mortality within 30 days of alert | 0.73 (0.461.16) | 0.87 (0.541.40) | 0.59 (0.341.04) | 0.69 (0.381.26) |

| Mortality or inpatient hospice transfer | 0.82 (0.471.41) | 0.78 (0.441.41) | 0.67 (0.361.25) | 0.65 (0.331.29) |

| Discharge to home | 1.29 (1.021.64) | 1.18 (0.911.52) | 1.36 (0.951.95) | 1.22 (0.811.84) |

| Sepsis discharge diagnosis | 1.32 (1.041.67) | 1.43 (1.101.85) | NA | NA |

In a subanalysis of EWRS impact on patients documented with sepsis at discharge, unadjusted and adjusted changes in clinical process and outcome measures across the time periods were similar to that of the total population (see Supporting Tables 5 and 6 and Supporting Figure 5 in the online version of this article). The unadjusted composite outcome of mortality or inpatient hospice was statistically lower in the postimplementation period, but lost statistical significance after adjustment.

The disposition and mortality outcomes of those not triggering the alert were unchanged across the 2 periods (see Supporting Tables 7, 8, and 9 in the online version of this article).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that a predictive tool can accurately identify non‐ICU inpatients at increased risk for deterioration and death. In addition, we demonstrated the feasibility of deploying our EHR to screen patients in real time for deterioration and to trigger electronically a timely, robust, multidisciplinary bedside clinical evaluation. Compared to the control (silent) period, the EWRS resulted in a marked increase in early sepsis care, transfer to the ICU, and sepsis documentation, and an indication of a decreased sepsis mortality index and mortality, and increased discharge to home, although none of these latter 3 findings reached statistical significance.

Our study is unique in that it was implemented across a multihospital health system, which has identical EHRs, but diverse cultures, populations, staffing, and practice models. In addition, our study includes a preimplementation population similar to the postimplementation population (in terms of setting, month of admission, and adjustment for potential confounders).

Interestingly, patients identified by the EWRS who were subsequently transferred to an ICU had higher mortality rates (30% and 26% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) than those transferred to an ICU who were not identified by the EWRS (7% and 6% in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods, respectively, across UPHS) (Table 4) (see Supporting Table 7 in the online version of this article). This finding was robust to the study period, so is likely not related to the bedside evaluation prompted by the EWRS. It suggests the EWRS could help triage patients for appropriateness of ICU transfer, a particularly valuable role that should be explored further given the typical strains on ICU capacity,[13] and the mortality resulting from delays in patient transfers into ICUs.[14, 15]

Although we did not find a statistically significant mortality reduction, our study may have been underpowered to detect this outcome. Our study has other limitations. First, our preimplementation/postimplementation design may not fully account for secular changes in sepsis mortality. However, our comparison of similar time periods and our adjustment for observed demographic differences allow us to estimate with more certainty the change in sepsis care and mortality attributable to the intervention. Second, our study did not examine the effect of the EWRS on mortality after hospital discharge, where many such events occur. However, our capture of at least 45 hospital days on all study patients, as well as our inclusion of only those who died or were discharged during our study period, and our assessment of discharge disposition such as hospice, increase the chance that mortality reductions directly attributable to the EWRS were captured. Third, although the EWRS changed patient management, we did not assess the appropriateness of management changes. However, the impact of care changes was captured crudely by examining mortality rates and discharge disposition. Fourth, our study was limited to a single academic healthcare system, and our experience may not be generalizable to other healthcare systems with different EHRs and staff. However, the integration of our automated alert into a commercial EHR serving a diverse array of patient populations, clinical services, and service models throughout our healthcare system may improve the generalizability of our experience to other settings.

CONCLUSION

By leveraging readily available electronic data, an automated prediction tool identified at‐risk patients and mobilized care teams, resulting in more timely sepsis care, improved sepsis documentation, and a suggestion of reduced mortality. This alert may be scalable to other healthcare systems.

Acknowledgements