User login

Lack of energy, petechiae, elevated PSA level—Dx?

THE CASE

A 57-year-old Hispanic man sought treatment because he had been feeling tired for a few weeks. He had not seen a physician for 15 years. When he came in, his temperature was 98.8°F, blood pressure was 132/82 mm Hg, pulse was 82 beats/min, respiration rate was 16 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 93% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems was normal. Skin examination showed petechiae and bruising on his abdomen, left ankle, right thigh, and bilateral shin area. His abdomen was nontender with no organomegaly. There was no focal neurological finding or spinal tenderness. Our patient had no chills, chest pains, shortness of breath, headache, dizziness, or loss of consciousness. There was no hematemesis, melena, hematuria, edema, or weight loss. He had no medical or surgical history and denied substance abuse or taking any medications recently; he did use alcohol previously.

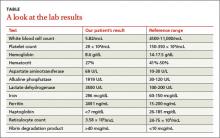

Results of some initial lab tests were abnormal, including a decreased white blood cell count (5.82/mcL), platelet count (29 x 103/mcL), hemoglobin (8.6 g/dL), and hematocrit (27%) (TABLE). A peripheral blood smear showed decreased normocytic red blood cells and scattered schistocytes. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was elevated at 212 ng/mL.

The patient’s coagulation profile was normal, and his von Willebrand factor (vWF) protease (ADAMTS-13) level was within normal limits (13.83). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody tests were negative. Testing for pulmonary embolism was negative, as was testing for human immunodeficiency virus. An abdominal ultrasound was normal, as well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on our patient’s abnormal blood test results and the presence of petechiae and bruising, we diagnosed thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The patient’s elevated PSA prompted us to order computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, which showed an enlarged prostate gland and mixed lytic sclerotic lesions in T3 to T5 and T9 vertebrae and in his ribs. A bone marrow biopsy revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma and a bone scan confirmed multiple metastases in the spine, pelvis, and shoulders.

DISCUSSION

TTP is a rare disorder of increased clotting in small blood vessels throughout the body that can include thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), fever, renal dysfunction, and neurological deficits.1 It’s important to maintain a high index of suspicion for TTP because the condition is a hematologic medical emergency that can quickly cause multiorgan failure and death.2

Almost always an acquired condition, TTP can be idiopathic or secondary to another condition, such as collagen vascular diseases, transplants, certain drugs, infections, pregnancy, or cancer.3 In idiopathic TTP, the cause of the condition is believed to be reduced activity of ADAMTS-13, the protease that breaks vWF into smaller pieces—thus preventing the formation of unnecessary blood clots.

In cancer-associated TTP, which could be a complication resulting from chemotherapy or a manifestation of cancer itself,3 ADAMTS-13 level is normal and the condition is likely the result of an increased tumor cell load, which leads to endothelial damage and fragmentation of red blood cells (RBC) as they traverse the injured microvasculature.4 In an analysis of 154 cases of “solid” cancer-related MAHA, Lechner and Obermeier5 found 23 cases were related to prostate cancer, as was the case with our patient.

Treatment for TTP is plasma exchange. The mortality rate of untreated TTP can exceed 90%, but plasma exchange therapy has reduced that rate to <20%.6 It has been suggested that proteolysis of vWF may play a central role in the efficacy of plasma exchange for TTP.7

Our patient was hospitalized and received 2 units of packed RBCs. He also received plasma exchange for 9 days with minimal response. On Day 5, our patient was started on leuprorelin and parenteral steroids. Soon after, his platelet count rose to 33 × 103/mcL and lactate dehydrogenase decreased. He was discharged approximately one week after the steroids were started.

After several months of outpatient treatment with leuprorelin and bicalutamide, the patient’s platelet count normalized to 212 × 103/mcL (from 29 × 103/mcL), alkaline phosphatase decreased to 402 U/L (from 1919 U/L), and PSA levels trended downward to 8.63 ng/mL (from 212 ng/mL). He continued to receive care from our oncology clinic for the next several months and his PSA level continued to decline. However, at his last few visits, his PSA level had trended up, suggesting progression of his prostate cancer. The patient has not followed up with our clinic recently.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect TTP in patients who present with unexplained petechiae and bruising, and whose blood work reveals thrombocytopenia and MAHA.2 Patients with TTP who do not respond to plasma exchange should be evaluated for underlying cancer or other potential secondary causes.3 Patients with cancer-associated TTP may respond to steroid therapy.

1. Lichtin AE, Schreiber AD, Hurwitz S, et al. Efficacy of intensive plasmapheresis in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Archives Intern Med. 1987;147:2122-2126.

2. Blombery P, Scully M. Management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: current perspectives. J Blood Med. 2014;5:15-23.

3. Chang JC, Naqvi T. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with bone marrow metastasis and secondary myelofibrosis in cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:375-380.

4. Pirrotta MT, Bucalossi A, Forconi F, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura secondary to an occult adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2005;10:299-300.

5. Lechner K, Obermeier HL. Cancer-related microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: clinical and laboratory features in 168 reported cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91: 195-205.

6. Oberic L, Buffet, M, Scwarzinger M, et al; Reference Center for the Management of Thrombotic Microangiopathies. Cancer awareness in atypical thrombotic microangiopathies. Oncologist. 2009;14:769-779.

7. Zheng X, Chung D, Takayama TK, et al. Structure of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS 13), a metalloprotease involved in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41059-41063.

THE CASE

A 57-year-old Hispanic man sought treatment because he had been feeling tired for a few weeks. He had not seen a physician for 15 years. When he came in, his temperature was 98.8°F, blood pressure was 132/82 mm Hg, pulse was 82 beats/min, respiration rate was 16 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 93% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems was normal. Skin examination showed petechiae and bruising on his abdomen, left ankle, right thigh, and bilateral shin area. His abdomen was nontender with no organomegaly. There was no focal neurological finding or spinal tenderness. Our patient had no chills, chest pains, shortness of breath, headache, dizziness, or loss of consciousness. There was no hematemesis, melena, hematuria, edema, or weight loss. He had no medical or surgical history and denied substance abuse or taking any medications recently; he did use alcohol previously.

Results of some initial lab tests were abnormal, including a decreased white blood cell count (5.82/mcL), platelet count (29 x 103/mcL), hemoglobin (8.6 g/dL), and hematocrit (27%) (TABLE). A peripheral blood smear showed decreased normocytic red blood cells and scattered schistocytes. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was elevated at 212 ng/mL.

The patient’s coagulation profile was normal, and his von Willebrand factor (vWF) protease (ADAMTS-13) level was within normal limits (13.83). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody tests were negative. Testing for pulmonary embolism was negative, as was testing for human immunodeficiency virus. An abdominal ultrasound was normal, as well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on our patient’s abnormal blood test results and the presence of petechiae and bruising, we diagnosed thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The patient’s elevated PSA prompted us to order computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, which showed an enlarged prostate gland and mixed lytic sclerotic lesions in T3 to T5 and T9 vertebrae and in his ribs. A bone marrow biopsy revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma and a bone scan confirmed multiple metastases in the spine, pelvis, and shoulders.

DISCUSSION

TTP is a rare disorder of increased clotting in small blood vessels throughout the body that can include thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), fever, renal dysfunction, and neurological deficits.1 It’s important to maintain a high index of suspicion for TTP because the condition is a hematologic medical emergency that can quickly cause multiorgan failure and death.2

Almost always an acquired condition, TTP can be idiopathic or secondary to another condition, such as collagen vascular diseases, transplants, certain drugs, infections, pregnancy, or cancer.3 In idiopathic TTP, the cause of the condition is believed to be reduced activity of ADAMTS-13, the protease that breaks vWF into smaller pieces—thus preventing the formation of unnecessary blood clots.

In cancer-associated TTP, which could be a complication resulting from chemotherapy or a manifestation of cancer itself,3 ADAMTS-13 level is normal and the condition is likely the result of an increased tumor cell load, which leads to endothelial damage and fragmentation of red blood cells (RBC) as they traverse the injured microvasculature.4 In an analysis of 154 cases of “solid” cancer-related MAHA, Lechner and Obermeier5 found 23 cases were related to prostate cancer, as was the case with our patient.

Treatment for TTP is plasma exchange. The mortality rate of untreated TTP can exceed 90%, but plasma exchange therapy has reduced that rate to <20%.6 It has been suggested that proteolysis of vWF may play a central role in the efficacy of plasma exchange for TTP.7

Our patient was hospitalized and received 2 units of packed RBCs. He also received plasma exchange for 9 days with minimal response. On Day 5, our patient was started on leuprorelin and parenteral steroids. Soon after, his platelet count rose to 33 × 103/mcL and lactate dehydrogenase decreased. He was discharged approximately one week after the steroids were started.

After several months of outpatient treatment with leuprorelin and bicalutamide, the patient’s platelet count normalized to 212 × 103/mcL (from 29 × 103/mcL), alkaline phosphatase decreased to 402 U/L (from 1919 U/L), and PSA levels trended downward to 8.63 ng/mL (from 212 ng/mL). He continued to receive care from our oncology clinic for the next several months and his PSA level continued to decline. However, at his last few visits, his PSA level had trended up, suggesting progression of his prostate cancer. The patient has not followed up with our clinic recently.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect TTP in patients who present with unexplained petechiae and bruising, and whose blood work reveals thrombocytopenia and MAHA.2 Patients with TTP who do not respond to plasma exchange should be evaluated for underlying cancer or other potential secondary causes.3 Patients with cancer-associated TTP may respond to steroid therapy.

THE CASE

A 57-year-old Hispanic man sought treatment because he had been feeling tired for a few weeks. He had not seen a physician for 15 years. When he came in, his temperature was 98.8°F, blood pressure was 132/82 mm Hg, pulse was 82 beats/min, respiration rate was 16 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation was 93% on room air. Examination of the head, neck, and respiratory and cardiovascular systems was normal. Skin examination showed petechiae and bruising on his abdomen, left ankle, right thigh, and bilateral shin area. His abdomen was nontender with no organomegaly. There was no focal neurological finding or spinal tenderness. Our patient had no chills, chest pains, shortness of breath, headache, dizziness, or loss of consciousness. There was no hematemesis, melena, hematuria, edema, or weight loss. He had no medical or surgical history and denied substance abuse or taking any medications recently; he did use alcohol previously.

Results of some initial lab tests were abnormal, including a decreased white blood cell count (5.82/mcL), platelet count (29 x 103/mcL), hemoglobin (8.6 g/dL), and hematocrit (27%) (TABLE). A peripheral blood smear showed decreased normocytic red blood cells and scattered schistocytes. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was elevated at 212 ng/mL.

The patient’s coagulation profile was normal, and his von Willebrand factor (vWF) protease (ADAMTS-13) level was within normal limits (13.83). Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and antinuclear antibody tests were negative. Testing for pulmonary embolism was negative, as was testing for human immunodeficiency virus. An abdominal ultrasound was normal, as well.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on our patient’s abnormal blood test results and the presence of petechiae and bruising, we diagnosed thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP). The patient’s elevated PSA prompted us to order computed tomography of the chest and abdomen, which showed an enlarged prostate gland and mixed lytic sclerotic lesions in T3 to T5 and T9 vertebrae and in his ribs. A bone marrow biopsy revealed metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma and a bone scan confirmed multiple metastases in the spine, pelvis, and shoulders.

DISCUSSION

TTP is a rare disorder of increased clotting in small blood vessels throughout the body that can include thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA), fever, renal dysfunction, and neurological deficits.1 It’s important to maintain a high index of suspicion for TTP because the condition is a hematologic medical emergency that can quickly cause multiorgan failure and death.2

Almost always an acquired condition, TTP can be idiopathic or secondary to another condition, such as collagen vascular diseases, transplants, certain drugs, infections, pregnancy, or cancer.3 In idiopathic TTP, the cause of the condition is believed to be reduced activity of ADAMTS-13, the protease that breaks vWF into smaller pieces—thus preventing the formation of unnecessary blood clots.

In cancer-associated TTP, which could be a complication resulting from chemotherapy or a manifestation of cancer itself,3 ADAMTS-13 level is normal and the condition is likely the result of an increased tumor cell load, which leads to endothelial damage and fragmentation of red blood cells (RBC) as they traverse the injured microvasculature.4 In an analysis of 154 cases of “solid” cancer-related MAHA, Lechner and Obermeier5 found 23 cases were related to prostate cancer, as was the case with our patient.

Treatment for TTP is plasma exchange. The mortality rate of untreated TTP can exceed 90%, but plasma exchange therapy has reduced that rate to <20%.6 It has been suggested that proteolysis of vWF may play a central role in the efficacy of plasma exchange for TTP.7

Our patient was hospitalized and received 2 units of packed RBCs. He also received plasma exchange for 9 days with minimal response. On Day 5, our patient was started on leuprorelin and parenteral steroids. Soon after, his platelet count rose to 33 × 103/mcL and lactate dehydrogenase decreased. He was discharged approximately one week after the steroids were started.

After several months of outpatient treatment with leuprorelin and bicalutamide, the patient’s platelet count normalized to 212 × 103/mcL (from 29 × 103/mcL), alkaline phosphatase decreased to 402 U/L (from 1919 U/L), and PSA levels trended downward to 8.63 ng/mL (from 212 ng/mL). He continued to receive care from our oncology clinic for the next several months and his PSA level continued to decline. However, at his last few visits, his PSA level had trended up, suggesting progression of his prostate cancer. The patient has not followed up with our clinic recently.

THE TAKEAWAY

Suspect TTP in patients who present with unexplained petechiae and bruising, and whose blood work reveals thrombocytopenia and MAHA.2 Patients with TTP who do not respond to plasma exchange should be evaluated for underlying cancer or other potential secondary causes.3 Patients with cancer-associated TTP may respond to steroid therapy.

1. Lichtin AE, Schreiber AD, Hurwitz S, et al. Efficacy of intensive plasmapheresis in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Archives Intern Med. 1987;147:2122-2126.

2. Blombery P, Scully M. Management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: current perspectives. J Blood Med. 2014;5:15-23.

3. Chang JC, Naqvi T. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with bone marrow metastasis and secondary myelofibrosis in cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:375-380.

4. Pirrotta MT, Bucalossi A, Forconi F, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura secondary to an occult adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2005;10:299-300.

5. Lechner K, Obermeier HL. Cancer-related microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: clinical and laboratory features in 168 reported cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91: 195-205.

6. Oberic L, Buffet, M, Scwarzinger M, et al; Reference Center for the Management of Thrombotic Microangiopathies. Cancer awareness in atypical thrombotic microangiopathies. Oncologist. 2009;14:769-779.

7. Zheng X, Chung D, Takayama TK, et al. Structure of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS 13), a metalloprotease involved in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41059-41063.

1. Lichtin AE, Schreiber AD, Hurwitz S, et al. Efficacy of intensive plasmapheresis in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Archives Intern Med. 1987;147:2122-2126.

2. Blombery P, Scully M. Management of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: current perspectives. J Blood Med. 2014;5:15-23.

3. Chang JC, Naqvi T. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with bone marrow metastasis and secondary myelofibrosis in cancer. Oncologist. 2003;8:375-380.

4. Pirrotta MT, Bucalossi A, Forconi F, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura secondary to an occult adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2005;10:299-300.

5. Lechner K, Obermeier HL. Cancer-related microangiopathic hemolytic anemia: clinical and laboratory features in 168 reported cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91: 195-205.

6. Oberic L, Buffet, M, Scwarzinger M, et al; Reference Center for the Management of Thrombotic Microangiopathies. Cancer awareness in atypical thrombotic microangiopathies. Oncologist. 2009;14:769-779.

7. Zheng X, Chung D, Takayama TK, et al. Structure of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS 13), a metalloprotease involved in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41059-41063.

Nausea, vomiting, malaise, frequent urination—Dx?

THE CASE

A 63-year-old multiparous woman visited her general practitioner because of nausea, vomiting, and general malaise. A proton pump inhibitor was prescribed, which temporarily relieved her symptoms. Two weeks later, however, her symptoms worsened and she was admitted to the hospital.

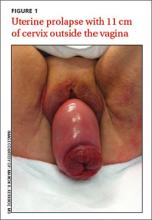

The patient’s physical examination on admission was normal, but laboratory findings revealed severe renal failure with a creatinine level of 7.4 mg/dL (normal, 0.6-1.1 mg/dL), potassium level of 7.4 mmol/L (3.5-5 mmol/L), and a sodium level of 123 mmol/L (135-145 mmol/L). A renal ultrasound revealed severe bilateral hydronephrosis with hydroureteronephrosis caused by obstructive uropathy. A radiologist examined the patient and determined that she had a total uterine prolapse; the cervix was 11 cm outside of the vagina (FIGURE 1). Our patient’s untreated pelvic organ prolapse (POP) had caused chronic renal failure. The patient was referred to a urogynecologist.

Previous attempts at treatment. It appeared that our patient had POP for years and there had been a previous attempt to treat it with a pessary. However, because of an unpleasant experience at her initial appointment and because her biggest complaint (until recently) had been the need to urinate frequently, she had not returned for follow-up appointments.

DISCUSSION

POP is not life-threatening, but the condition lowers the quality of life for 50% of parous women age >50 years.1 It can present as stress urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mechanical problems due to vaginal bulging or pelvic pressure.2 With the exception of vaginal bulging, symptoms are not specific for POP and there is no linear relationship between the severity of the prolapse and the symptoms.3,4

The condition is staged using the POP-Quantification (POP-Q) system5:

1. Stage 0: no prolapse

2. Stage I: the most distal portion of the prolapse is >1 cm above the hymen

3. Stage II: the prolapse is ≤1 cm proximal or distal to the plane of the hymen

4. Stage III: the prolapse is >1 cm below the plane of the hymen, but protrudes no farther

than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length

5. Stage IV: complete eversion of the lower genital tract.

As was the case with our patient, it is possible for a woman with severe total uterine prolapse (Stage IV) to have no major problems with urination or defecation.

The link between POP and hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis appears to be a frequent finding in women with POP.4 A recent prospective observational study reported an overall prevalence of 10.3% (95% confidence interval, 6%-14%) in women with POP.4 Patients with advanced stages of POP (POP-Q Stage III or IV)4 who also had diabetes mellitus and hypertension were at particularly high risk, with a prevalence of about 20%. An analysis of factors, including age, parity, diabetes, hypertension, and type of prolapse, found that severity of POP was the strongest predictor of hydronephrosis: Patients with a Stage III to IV prolapse are 3.4 times more likely to have hydronephrosis than those with a Stage I or II prolapse.4,6

Possible causes of hydronephrosis in POP patients. Some researchers have proposed that hydronephrosis in patients with uterine prolapse may be due to a kinking of the ureters by the extrinsic compression of the prolapsed uterus. In patients with vaginal vault prolapse, the cause of the hydronephrosis could be a weakening or disintegration of the cardinal ligaments after hysterectomy.4,7

Patients may not complain. When hydronephrosis caused by POP occurs, it may develop slowly, causing little or no discomfort. As time passes, patients may complain of dull pain in the flank, suffer from urinary tract infections, or develop kidney stones before progressive renal dysfunction or renal failure occurs.4

There are 2 other cases in the literature of women who, like our patient, had uterine prolapse that went untreated until they were in renal failure.8,9 The patients noticed only mechanical problems due to the POP; bilateral hydroureteronephrosis and renal failure had developed undetected. In the end, both women needed lifelong hemodialysis.

Treatment options

Treatment options for POP include supervised pelvic floor exercise programs, pessary insertion, or reconstructive pelvic surgery. If POP is treated adequately, an estimated 95% of the hydronephrosis can resolve, regardless of its severity at presentation.4

Our patient was treated with a 95 mm Falk pessary. After 24 hours, renal ultrasonography showed a decrease in both the hydroureteronephrosis and the hydronephrosis (FIGURE 2A and 2B). Four weeks later, her serum creatinine level had decreased to 3.3 mg/dL. Four years later, our patient continues to wear the pessary but has chronic renal failure.

THE TAKEAWAY

POP often is viewed as a minor problem, but it can cause obstructive uropathy with unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis or renal dysfunction and/or failure. The delay often seen with reporting genital prolapse may be due to the mild symptoms or feelings of shame or fear. Combining screening for cervical pathology in general practice with a screening for genital prolapse could identify these problems.

Monitoring renal function is advised in patients with a Stage III or IV POP and any patients with POP who also have hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Because only minor changes in laboratory findings may be observed in patients with unilateral hydronephrosis, consider renal ultrasonography.

Treatment options for POP includes pelvic floor exercises, pessary insertion, and reconstructive surgery. Early treatment can resolve hydronephrosis and possibly prevent irreversible renal damage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Wilhelm Van Dorp, MD, Rob A. van de Beek, MD, and Alan Brind for their help with this manuscript.

1. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD004014.

2. Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369:1027-1038.

3. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184. e1-184.e7.

4. Hui SY, Chan SC, Lam SY, et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of hydronephrosis in women with pelvic organ prolapse and their outcomes after treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1529-1534.

5. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

6. Gemer O, Bergman M, Segal S. Prevalence of hydronephrosis in patients with genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:11-13.

7. Lieberthal F, Frankenthal L Jr. The mechanism of urethral obstruction in prolapse of the uterus. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1941;73:838-842.

8. Sanai T, Yamashiro Y, Nakayama M, et al. End-stage renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Urology. 2006;67:622. e5-622.e7.

9. Nässberger L, Larsson R. End-stage chronic renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1982;61: 495-497.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old multiparous woman visited her general practitioner because of nausea, vomiting, and general malaise. A proton pump inhibitor was prescribed, which temporarily relieved her symptoms. Two weeks later, however, her symptoms worsened and she was admitted to the hospital.

The patient’s physical examination on admission was normal, but laboratory findings revealed severe renal failure with a creatinine level of 7.4 mg/dL (normal, 0.6-1.1 mg/dL), potassium level of 7.4 mmol/L (3.5-5 mmol/L), and a sodium level of 123 mmol/L (135-145 mmol/L). A renal ultrasound revealed severe bilateral hydronephrosis with hydroureteronephrosis caused by obstructive uropathy. A radiologist examined the patient and determined that she had a total uterine prolapse; the cervix was 11 cm outside of the vagina (FIGURE 1). Our patient’s untreated pelvic organ prolapse (POP) had caused chronic renal failure. The patient was referred to a urogynecologist.

Previous attempts at treatment. It appeared that our patient had POP for years and there had been a previous attempt to treat it with a pessary. However, because of an unpleasant experience at her initial appointment and because her biggest complaint (until recently) had been the need to urinate frequently, she had not returned for follow-up appointments.

DISCUSSION

POP is not life-threatening, but the condition lowers the quality of life for 50% of parous women age >50 years.1 It can present as stress urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mechanical problems due to vaginal bulging or pelvic pressure.2 With the exception of vaginal bulging, symptoms are not specific for POP and there is no linear relationship between the severity of the prolapse and the symptoms.3,4

The condition is staged using the POP-Quantification (POP-Q) system5:

1. Stage 0: no prolapse

2. Stage I: the most distal portion of the prolapse is >1 cm above the hymen

3. Stage II: the prolapse is ≤1 cm proximal or distal to the plane of the hymen

4. Stage III: the prolapse is >1 cm below the plane of the hymen, but protrudes no farther

than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length

5. Stage IV: complete eversion of the lower genital tract.

As was the case with our patient, it is possible for a woman with severe total uterine prolapse (Stage IV) to have no major problems with urination or defecation.

The link between POP and hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis appears to be a frequent finding in women with POP.4 A recent prospective observational study reported an overall prevalence of 10.3% (95% confidence interval, 6%-14%) in women with POP.4 Patients with advanced stages of POP (POP-Q Stage III or IV)4 who also had diabetes mellitus and hypertension were at particularly high risk, with a prevalence of about 20%. An analysis of factors, including age, parity, diabetes, hypertension, and type of prolapse, found that severity of POP was the strongest predictor of hydronephrosis: Patients with a Stage III to IV prolapse are 3.4 times more likely to have hydronephrosis than those with a Stage I or II prolapse.4,6

Possible causes of hydronephrosis in POP patients. Some researchers have proposed that hydronephrosis in patients with uterine prolapse may be due to a kinking of the ureters by the extrinsic compression of the prolapsed uterus. In patients with vaginal vault prolapse, the cause of the hydronephrosis could be a weakening or disintegration of the cardinal ligaments after hysterectomy.4,7

Patients may not complain. When hydronephrosis caused by POP occurs, it may develop slowly, causing little or no discomfort. As time passes, patients may complain of dull pain in the flank, suffer from urinary tract infections, or develop kidney stones before progressive renal dysfunction or renal failure occurs.4

There are 2 other cases in the literature of women who, like our patient, had uterine prolapse that went untreated until they were in renal failure.8,9 The patients noticed only mechanical problems due to the POP; bilateral hydroureteronephrosis and renal failure had developed undetected. In the end, both women needed lifelong hemodialysis.

Treatment options

Treatment options for POP include supervised pelvic floor exercise programs, pessary insertion, or reconstructive pelvic surgery. If POP is treated adequately, an estimated 95% of the hydronephrosis can resolve, regardless of its severity at presentation.4

Our patient was treated with a 95 mm Falk pessary. After 24 hours, renal ultrasonography showed a decrease in both the hydroureteronephrosis and the hydronephrosis (FIGURE 2A and 2B). Four weeks later, her serum creatinine level had decreased to 3.3 mg/dL. Four years later, our patient continues to wear the pessary but has chronic renal failure.

THE TAKEAWAY

POP often is viewed as a minor problem, but it can cause obstructive uropathy with unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis or renal dysfunction and/or failure. The delay often seen with reporting genital prolapse may be due to the mild symptoms or feelings of shame or fear. Combining screening for cervical pathology in general practice with a screening for genital prolapse could identify these problems.

Monitoring renal function is advised in patients with a Stage III or IV POP and any patients with POP who also have hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Because only minor changes in laboratory findings may be observed in patients with unilateral hydronephrosis, consider renal ultrasonography.

Treatment options for POP includes pelvic floor exercises, pessary insertion, and reconstructive surgery. Early treatment can resolve hydronephrosis and possibly prevent irreversible renal damage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Wilhelm Van Dorp, MD, Rob A. van de Beek, MD, and Alan Brind for their help with this manuscript.

THE CASE

A 63-year-old multiparous woman visited her general practitioner because of nausea, vomiting, and general malaise. A proton pump inhibitor was prescribed, which temporarily relieved her symptoms. Two weeks later, however, her symptoms worsened and she was admitted to the hospital.

The patient’s physical examination on admission was normal, but laboratory findings revealed severe renal failure with a creatinine level of 7.4 mg/dL (normal, 0.6-1.1 mg/dL), potassium level of 7.4 mmol/L (3.5-5 mmol/L), and a sodium level of 123 mmol/L (135-145 mmol/L). A renal ultrasound revealed severe bilateral hydronephrosis with hydroureteronephrosis caused by obstructive uropathy. A radiologist examined the patient and determined that she had a total uterine prolapse; the cervix was 11 cm outside of the vagina (FIGURE 1). Our patient’s untreated pelvic organ prolapse (POP) had caused chronic renal failure. The patient was referred to a urogynecologist.

Previous attempts at treatment. It appeared that our patient had POP for years and there had been a previous attempt to treat it with a pessary. However, because of an unpleasant experience at her initial appointment and because her biggest complaint (until recently) had been the need to urinate frequently, she had not returned for follow-up appointments.

DISCUSSION

POP is not life-threatening, but the condition lowers the quality of life for 50% of parous women age >50 years.1 It can present as stress urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, sexual dysfunction, and mechanical problems due to vaginal bulging or pelvic pressure.2 With the exception of vaginal bulging, symptoms are not specific for POP and there is no linear relationship between the severity of the prolapse and the symptoms.3,4

The condition is staged using the POP-Quantification (POP-Q) system5:

1. Stage 0: no prolapse

2. Stage I: the most distal portion of the prolapse is >1 cm above the hymen

3. Stage II: the prolapse is ≤1 cm proximal or distal to the plane of the hymen

4. Stage III: the prolapse is >1 cm below the plane of the hymen, but protrudes no farther

than 2 cm less than the total vaginal length

5. Stage IV: complete eversion of the lower genital tract.

As was the case with our patient, it is possible for a woman with severe total uterine prolapse (Stage IV) to have no major problems with urination or defecation.

The link between POP and hydronephrosis

Hydronephrosis appears to be a frequent finding in women with POP.4 A recent prospective observational study reported an overall prevalence of 10.3% (95% confidence interval, 6%-14%) in women with POP.4 Patients with advanced stages of POP (POP-Q Stage III or IV)4 who also had diabetes mellitus and hypertension were at particularly high risk, with a prevalence of about 20%. An analysis of factors, including age, parity, diabetes, hypertension, and type of prolapse, found that severity of POP was the strongest predictor of hydronephrosis: Patients with a Stage III to IV prolapse are 3.4 times more likely to have hydronephrosis than those with a Stage I or II prolapse.4,6

Possible causes of hydronephrosis in POP patients. Some researchers have proposed that hydronephrosis in patients with uterine prolapse may be due to a kinking of the ureters by the extrinsic compression of the prolapsed uterus. In patients with vaginal vault prolapse, the cause of the hydronephrosis could be a weakening or disintegration of the cardinal ligaments after hysterectomy.4,7

Patients may not complain. When hydronephrosis caused by POP occurs, it may develop slowly, causing little or no discomfort. As time passes, patients may complain of dull pain in the flank, suffer from urinary tract infections, or develop kidney stones before progressive renal dysfunction or renal failure occurs.4

There are 2 other cases in the literature of women who, like our patient, had uterine prolapse that went untreated until they were in renal failure.8,9 The patients noticed only mechanical problems due to the POP; bilateral hydroureteronephrosis and renal failure had developed undetected. In the end, both women needed lifelong hemodialysis.

Treatment options

Treatment options for POP include supervised pelvic floor exercise programs, pessary insertion, or reconstructive pelvic surgery. If POP is treated adequately, an estimated 95% of the hydronephrosis can resolve, regardless of its severity at presentation.4

Our patient was treated with a 95 mm Falk pessary. After 24 hours, renal ultrasonography showed a decrease in both the hydroureteronephrosis and the hydronephrosis (FIGURE 2A and 2B). Four weeks later, her serum creatinine level had decreased to 3.3 mg/dL. Four years later, our patient continues to wear the pessary but has chronic renal failure.

THE TAKEAWAY

POP often is viewed as a minor problem, but it can cause obstructive uropathy with unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis or renal dysfunction and/or failure. The delay often seen with reporting genital prolapse may be due to the mild symptoms or feelings of shame or fear. Combining screening for cervical pathology in general practice with a screening for genital prolapse could identify these problems.

Monitoring renal function is advised in patients with a Stage III or IV POP and any patients with POP who also have hypertension or diabetes mellitus. Because only minor changes in laboratory findings may be observed in patients with unilateral hydronephrosis, consider renal ultrasonography.

Treatment options for POP includes pelvic floor exercises, pessary insertion, and reconstructive surgery. Early treatment can resolve hydronephrosis and possibly prevent irreversible renal damage.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Wilhelm Van Dorp, MD, Rob A. van de Beek, MD, and Alan Brind for their help with this manuscript.

1. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD004014.

2. Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369:1027-1038.

3. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184. e1-184.e7.

4. Hui SY, Chan SC, Lam SY, et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of hydronephrosis in women with pelvic organ prolapse and their outcomes after treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1529-1534.

5. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

6. Gemer O, Bergman M, Segal S. Prevalence of hydronephrosis in patients with genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:11-13.

7. Lieberthal F, Frankenthal L Jr. The mechanism of urethral obstruction in prolapse of the uterus. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1941;73:838-842.

8. Sanai T, Yamashiro Y, Nakayama M, et al. End-stage renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Urology. 2006;67:622. e5-622.e7.

9. Nässberger L, Larsson R. End-stage chronic renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1982;61: 495-497.

1. Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, et al. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD004014.

2. Jelovsek JE, Maher C, Barber MD. Pelvic organ prolapse. Lancet. 2007;369:1027-1038.

3. Slieker-ten Hove MC, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Eijkemans MJ, et al. Symptomatic pelvic organ prolapse and possible risk factors in a general population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:184. e1-184.e7.

4. Hui SY, Chan SC, Lam SY, et al. A prospective study on the prevalence of hydronephrosis in women with pelvic organ prolapse and their outcomes after treatment. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1529-1534.

5. Bump RC, Mattiasson A, Bø K, et al. The standardization of terminology of female pelvic organ prolapse and pelvic floor dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:10-17.

6. Gemer O, Bergman M, Segal S. Prevalence of hydronephrosis in patients with genital prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1999;86:11-13.

7. Lieberthal F, Frankenthal L Jr. The mechanism of urethral obstruction in prolapse of the uterus. Surg Gynaecol Obstet. 1941;73:838-842.

8. Sanai T, Yamashiro Y, Nakayama M, et al. End-stage renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Urology. 2006;67:622. e5-622.e7.

9. Nässberger L, Larsson R. End-stage chronic renal failure due to total uterine prolapse. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1982;61: 495-497.

Hot topics in vaccines

I recently attended the International Interscience Conference of Infectious Diseases and Vaccines, and I would like to share some of the presentations from the session entitled “Hot Topics in Vaccines.”

CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus infection

Dr. Michelle Science of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and her associates described the spectrum of CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in children admitted to the hospital during 1999-2012 (J. Pediatr. 2014;165:779-85). Clinical syndromes included 26 cases of acute cerebellar ataxia, 17 of encephalitis, 16 isolated seizures, 10 strokes, 10 cases of meningitis, 2 cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, 2 cases of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case of Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In children with acute nonstroke complications, neurologic symptoms occurred a median 5 days after the onset of rash, but neurologic symptoms predated the onset of rash in five cases and in two cases there were no exanthems. Time between rash onset and stroke ranged from 2 to 26 weeks (median 16 weeks). There were three deaths among the 17 (18%) children with encephalitis. Among the 39 children with follow-up at 1 year, residual neurologic sequelae occurred in 9 (23%). Only four of the children had received a VZV vaccine. Although an effective vaccine exists, neurologic complications of VZV infection continue to occur.

Timely versus delayed early childhood vaccination and seizures

Dr. Simon J. Hambidge of Denver Health, Colorado, and his associates studied a cohort of 323,247 U.S. children from the Vaccine Safety Datalink born during 2004-2008 for an association between the timing of childhood vaccination and the first occurrence of seizures (Pediatrics 2014;133(6):e1492-9). In the first year, there was no association between the timing of infant vaccination and postvaccination seizures. In the second year, the incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first MMR dose at 12-15 months was 2.7, compared with a rate of 6.5 after an MMR dose at 16-23 months; thus there were more seizures when MMR was delayed. The incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine (MMRV) dose at 12-15 months was 4.95, compared with 9.80 after an MMRV dose at 16-23 months. Again, there were more seizures when MMRV was delayed. These findings suggest that on-time vaccination is as safe with regard to seizures as delayed vaccination in year 1, and that delayed vaccination in year 2 is linked to more postvaccination seizures than on-time vaccination with MMR and that risk is doubled with MMRV.

Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial

Brendan Nyhan, Ph.D., of Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., and his associates tested the efficacy of various informational messages tailored to reduce misperceptions about vaccines and increase MMR vaccination rates (Pediatrics 2014;133:e835-42). Nearly 1,800 parents were randomly assigned to receive one of four interventions: information explaining the lack of evidence that MMR causes autism from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; information about the danger of the diseases prevented by MMR from the Vaccine Information Statement; photos of children with diseases prevented by the MMR vaccine; a dramatic narrative about an infant who almost died of measles from a CDC fact sheet. In addition there was a control group. None of the four interventions increased parents’ intention to vaccinate another child if they had one in the future. Although refuting claims of an MMR/autism link did reduce misperceptions that vaccines cause autism, it decreased intent to vaccinate among parents who had the least favorable attitudes toward vaccines. Also, photos of sick children increased belief in an association between vaccines and autism, and the dramatic narrative about an infant in danger increased belief in serious vaccine side effects. Attempts to rectify misperceptions about vaccines may be counterproductive in some populations, so public health communications about vaccines should be tested before being widely disseminated.

Silent reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus to Israel, 2013

Dr. E. Kaliner of the Israeli Ministry of Health, Jerusalem, and associates, reported that Israel has been certified as polio-free by the World Health Organization for decades and its routine immunization schedule, like the United States, consists of inactivated poliovirus vaccine only (Euro. Surveill. 2014;19:20703). At the end of May 2013, the Israeli Ministry of Health confirmed the reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus 1 into the country. Documented ongoing human-to-human transmission required a thorough risk assessment followed by a supplemental immunization campaign using oral polio vaccine.

Trends in otitis media–related health care use in the United States, 2001-2011

Dr. Tal Marom of the University of Texas, Galveston, and associates studied the trend in otitis media–related health care use in the United States during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) era in 2001-2011 (JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:68-75). An analysis of an insurance claims database of a large, nationwide managed health care plan was conducted; 7.82 million children aged 6 years and under had 6.21 million primary otitis media (OM) visits. There was an overall downward trend in OM-related health care use across the 10-year study. Recurrent OM rates (defined as greater than or equal to three OM visits within 6 months) decreased at 0.003 per child-year in 2001-2009 and at 0.018 per child-year in 2010-2011. Prior to the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13), there was a stable rate ratio of 1.38 between OM visit rates. During the transition year 2010, the RR decreased significantly to 1.32, and in 2011 the RR decreased further to 1.01. Mastoiditis rates significantly decreased from 61 per 100,000 child-years in 2008 to 37 per 100,000 child-years in 2011. The ventilating tube insertion rate decreased by 19% from 2010 to 2011. Tympanic membrane perforation/otorrhea rates increased gradually and significantly from 3,721 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2001 to 4,542 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2011; the reasons for this are unclear.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no financial disclosures relevant to this article. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

I recently attended the International Interscience Conference of Infectious Diseases and Vaccines, and I would like to share some of the presentations from the session entitled “Hot Topics in Vaccines.”

CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus infection

Dr. Michelle Science of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and her associates described the spectrum of CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in children admitted to the hospital during 1999-2012 (J. Pediatr. 2014;165:779-85). Clinical syndromes included 26 cases of acute cerebellar ataxia, 17 of encephalitis, 16 isolated seizures, 10 strokes, 10 cases of meningitis, 2 cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, 2 cases of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case of Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In children with acute nonstroke complications, neurologic symptoms occurred a median 5 days after the onset of rash, but neurologic symptoms predated the onset of rash in five cases and in two cases there were no exanthems. Time between rash onset and stroke ranged from 2 to 26 weeks (median 16 weeks). There were three deaths among the 17 (18%) children with encephalitis. Among the 39 children with follow-up at 1 year, residual neurologic sequelae occurred in 9 (23%). Only four of the children had received a VZV vaccine. Although an effective vaccine exists, neurologic complications of VZV infection continue to occur.

Timely versus delayed early childhood vaccination and seizures

Dr. Simon J. Hambidge of Denver Health, Colorado, and his associates studied a cohort of 323,247 U.S. children from the Vaccine Safety Datalink born during 2004-2008 for an association between the timing of childhood vaccination and the first occurrence of seizures (Pediatrics 2014;133(6):e1492-9). In the first year, there was no association between the timing of infant vaccination and postvaccination seizures. In the second year, the incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first MMR dose at 12-15 months was 2.7, compared with a rate of 6.5 after an MMR dose at 16-23 months; thus there were more seizures when MMR was delayed. The incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine (MMRV) dose at 12-15 months was 4.95, compared with 9.80 after an MMRV dose at 16-23 months. Again, there were more seizures when MMRV was delayed. These findings suggest that on-time vaccination is as safe with regard to seizures as delayed vaccination in year 1, and that delayed vaccination in year 2 is linked to more postvaccination seizures than on-time vaccination with MMR and that risk is doubled with MMRV.

Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial

Brendan Nyhan, Ph.D., of Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., and his associates tested the efficacy of various informational messages tailored to reduce misperceptions about vaccines and increase MMR vaccination rates (Pediatrics 2014;133:e835-42). Nearly 1,800 parents were randomly assigned to receive one of four interventions: information explaining the lack of evidence that MMR causes autism from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; information about the danger of the diseases prevented by MMR from the Vaccine Information Statement; photos of children with diseases prevented by the MMR vaccine; a dramatic narrative about an infant who almost died of measles from a CDC fact sheet. In addition there was a control group. None of the four interventions increased parents’ intention to vaccinate another child if they had one in the future. Although refuting claims of an MMR/autism link did reduce misperceptions that vaccines cause autism, it decreased intent to vaccinate among parents who had the least favorable attitudes toward vaccines. Also, photos of sick children increased belief in an association between vaccines and autism, and the dramatic narrative about an infant in danger increased belief in serious vaccine side effects. Attempts to rectify misperceptions about vaccines may be counterproductive in some populations, so public health communications about vaccines should be tested before being widely disseminated.

Silent reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus to Israel, 2013

Dr. E. Kaliner of the Israeli Ministry of Health, Jerusalem, and associates, reported that Israel has been certified as polio-free by the World Health Organization for decades and its routine immunization schedule, like the United States, consists of inactivated poliovirus vaccine only (Euro. Surveill. 2014;19:20703). At the end of May 2013, the Israeli Ministry of Health confirmed the reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus 1 into the country. Documented ongoing human-to-human transmission required a thorough risk assessment followed by a supplemental immunization campaign using oral polio vaccine.

Trends in otitis media–related health care use in the United States, 2001-2011

Dr. Tal Marom of the University of Texas, Galveston, and associates studied the trend in otitis media–related health care use in the United States during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) era in 2001-2011 (JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:68-75). An analysis of an insurance claims database of a large, nationwide managed health care plan was conducted; 7.82 million children aged 6 years and under had 6.21 million primary otitis media (OM) visits. There was an overall downward trend in OM-related health care use across the 10-year study. Recurrent OM rates (defined as greater than or equal to three OM visits within 6 months) decreased at 0.003 per child-year in 2001-2009 and at 0.018 per child-year in 2010-2011. Prior to the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13), there was a stable rate ratio of 1.38 between OM visit rates. During the transition year 2010, the RR decreased significantly to 1.32, and in 2011 the RR decreased further to 1.01. Mastoiditis rates significantly decreased from 61 per 100,000 child-years in 2008 to 37 per 100,000 child-years in 2011. The ventilating tube insertion rate decreased by 19% from 2010 to 2011. Tympanic membrane perforation/otorrhea rates increased gradually and significantly from 3,721 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2001 to 4,542 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2011; the reasons for this are unclear.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no financial disclosures relevant to this article. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

I recently attended the International Interscience Conference of Infectious Diseases and Vaccines, and I would like to share some of the presentations from the session entitled “Hot Topics in Vaccines.”

CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus infection

Dr. Michelle Science of the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, and her associates described the spectrum of CNS complications of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) in children admitted to the hospital during 1999-2012 (J. Pediatr. 2014;165:779-85). Clinical syndromes included 26 cases of acute cerebellar ataxia, 17 of encephalitis, 16 isolated seizures, 10 strokes, 10 cases of meningitis, 2 cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome, 2 cases of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and 1 case of Ramsay Hunt syndrome. In children with acute nonstroke complications, neurologic symptoms occurred a median 5 days after the onset of rash, but neurologic symptoms predated the onset of rash in five cases and in two cases there were no exanthems. Time between rash onset and stroke ranged from 2 to 26 weeks (median 16 weeks). There were three deaths among the 17 (18%) children with encephalitis. Among the 39 children with follow-up at 1 year, residual neurologic sequelae occurred in 9 (23%). Only four of the children had received a VZV vaccine. Although an effective vaccine exists, neurologic complications of VZV infection continue to occur.

Timely versus delayed early childhood vaccination and seizures

Dr. Simon J. Hambidge of Denver Health, Colorado, and his associates studied a cohort of 323,247 U.S. children from the Vaccine Safety Datalink born during 2004-2008 for an association between the timing of childhood vaccination and the first occurrence of seizures (Pediatrics 2014;133(6):e1492-9). In the first year, there was no association between the timing of infant vaccination and postvaccination seizures. In the second year, the incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first MMR dose at 12-15 months was 2.7, compared with a rate of 6.5 after an MMR dose at 16-23 months; thus there were more seizures when MMR was delayed. The incidence rate ratio for seizures after receiving the first measles-mumps-rubella-varicella vaccine (MMRV) dose at 12-15 months was 4.95, compared with 9.80 after an MMRV dose at 16-23 months. Again, there were more seizures when MMRV was delayed. These findings suggest that on-time vaccination is as safe with regard to seizures as delayed vaccination in year 1, and that delayed vaccination in year 2 is linked to more postvaccination seizures than on-time vaccination with MMR and that risk is doubled with MMRV.

Effective messages in vaccine promotion: a randomized trial

Brendan Nyhan, Ph.D., of Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., and his associates tested the efficacy of various informational messages tailored to reduce misperceptions about vaccines and increase MMR vaccination rates (Pediatrics 2014;133:e835-42). Nearly 1,800 parents were randomly assigned to receive one of four interventions: information explaining the lack of evidence that MMR causes autism from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; information about the danger of the diseases prevented by MMR from the Vaccine Information Statement; photos of children with diseases prevented by the MMR vaccine; a dramatic narrative about an infant who almost died of measles from a CDC fact sheet. In addition there was a control group. None of the four interventions increased parents’ intention to vaccinate another child if they had one in the future. Although refuting claims of an MMR/autism link did reduce misperceptions that vaccines cause autism, it decreased intent to vaccinate among parents who had the least favorable attitudes toward vaccines. Also, photos of sick children increased belief in an association between vaccines and autism, and the dramatic narrative about an infant in danger increased belief in serious vaccine side effects. Attempts to rectify misperceptions about vaccines may be counterproductive in some populations, so public health communications about vaccines should be tested before being widely disseminated.

Silent reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus to Israel, 2013

Dr. E. Kaliner of the Israeli Ministry of Health, Jerusalem, and associates, reported that Israel has been certified as polio-free by the World Health Organization for decades and its routine immunization schedule, like the United States, consists of inactivated poliovirus vaccine only (Euro. Surveill. 2014;19:20703). At the end of May 2013, the Israeli Ministry of Health confirmed the reintroduction of wild-type poliovirus 1 into the country. Documented ongoing human-to-human transmission required a thorough risk assessment followed by a supplemental immunization campaign using oral polio vaccine.

Trends in otitis media–related health care use in the United States, 2001-2011

Dr. Tal Marom of the University of Texas, Galveston, and associates studied the trend in otitis media–related health care use in the United States during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) era in 2001-2011 (JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:68-75). An analysis of an insurance claims database of a large, nationwide managed health care plan was conducted; 7.82 million children aged 6 years and under had 6.21 million primary otitis media (OM) visits. There was an overall downward trend in OM-related health care use across the 10-year study. Recurrent OM rates (defined as greater than or equal to three OM visits within 6 months) decreased at 0.003 per child-year in 2001-2009 and at 0.018 per child-year in 2010-2011. Prior to the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV-13), there was a stable rate ratio of 1.38 between OM visit rates. During the transition year 2010, the RR decreased significantly to 1.32, and in 2011 the RR decreased further to 1.01. Mastoiditis rates significantly decreased from 61 per 100,000 child-years in 2008 to 37 per 100,000 child-years in 2011. The ventilating tube insertion rate decreased by 19% from 2010 to 2011. Tympanic membrane perforation/otorrhea rates increased gradually and significantly from 3,721 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2001 to 4,542 per 100,000 OM child-years in 2011; the reasons for this are unclear.

Dr. Pichichero, a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, is director of the Research Institute, Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He is also a pediatrician at Legacy Pediatrics in Rochester. Dr. Pichichero said he had no financial disclosures relevant to this article. To comment, e-mail him at [email protected].

Why is metformin contraindicated in chronic kidney disease?

To the Editor: In their article about the care of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, Sakhuja et al1 mentioned that metformin is contraindicated in chronic kidney disease.

Metformin is a good and useful drug. Not only is it one of the cheapest antidiabetic medications, it is the only one shown to reduce cardiovascular mortality rates in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Although metformin is thought to increase the risk of lactic acidosis, a Cochrane review2 found that the incidence of lactic acidosis was only 4.3 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients taking metformin, compared with 5.4 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients not taking metformin. Furthermore, in a large registry of patients with type 2 diabetes and atherothrombosis,3 the rate of all-cause mortality was 24% lower in metformin users than in nonusers, and in those who had moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) the difference was 36%.3

A trial by Rachmani et al4 raised questions about the standard contraindications to metformin. The authors reviewed 393 patients who had at least one contraindication to metformin but who were receiving it anyway. Their serum creatinine levels ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 mg/dL. There were no cases of lactic acidosis reported. The patients were then randomized either to continue taking metformin or to stop taking it. At 2 years, the group that had stopped taking it had gained more weight, and their glycemic control was worse.

In the Cochrane analysis,2 although individual creatinine levels were not available, 53% of the studies reviewed did not exclude patients with serum creatinine levels higher than 1.5 mg/dL. This equated to 37,360 patient-years of metformin use in studies that included patients with chronic kidney disease, and did not lead to lactic acidosis.

Even though metformin’s US package insert says that it is contraindicated if the serum creatinine level is 1.5 mg/dL or higher in men or 1.4 mg/dL or higher in women or if the creatinine clearance is “abnormal,” in view of the available evidence, many countries (eg, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands) now allow metformin to be used in patients with glomerular filtration rates as low as 30 mL/min/1.73m2, with lower doses if the glomerular filtration rate is lower than 45.5

The current contraindication to metformin in chronic kidney disease needs to be reviewed. In poor countries like India, this cheap medicine may be the only option available for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus, and it remains the first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus as recommended by the International Diabetes Federation, the American Diabetes Association, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.5

- Sakhuja A, Hyland J, Simon JF. Managing advanced chronic kidney disease: a primary care guide. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:289–299.

- Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 4:CD002967.

- Roussel R, Travert F, Pasquet B, et al; Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry Investigators. Metformin use and mortality among patients with diabetes and atherothrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:1892–1899.

- Rachmani R, Slavachevski I, Levi Z, Zadok B, Kedar Y, Ravid M. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: reconsideration of traditional contraindications. Eur J Intern Med 2002; 13:428–433.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35:1364–1379.

To the Editor: In their article about the care of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, Sakhuja et al1 mentioned that metformin is contraindicated in chronic kidney disease.

Metformin is a good and useful drug. Not only is it one of the cheapest antidiabetic medications, it is the only one shown to reduce cardiovascular mortality rates in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Although metformin is thought to increase the risk of lactic acidosis, a Cochrane review2 found that the incidence of lactic acidosis was only 4.3 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients taking metformin, compared with 5.4 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients not taking metformin. Furthermore, in a large registry of patients with type 2 diabetes and atherothrombosis,3 the rate of all-cause mortality was 24% lower in metformin users than in nonusers, and in those who had moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) the difference was 36%.3

A trial by Rachmani et al4 raised questions about the standard contraindications to metformin. The authors reviewed 393 patients who had at least one contraindication to metformin but who were receiving it anyway. Their serum creatinine levels ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 mg/dL. There were no cases of lactic acidosis reported. The patients were then randomized either to continue taking metformin or to stop taking it. At 2 years, the group that had stopped taking it had gained more weight, and their glycemic control was worse.

In the Cochrane analysis,2 although individual creatinine levels were not available, 53% of the studies reviewed did not exclude patients with serum creatinine levels higher than 1.5 mg/dL. This equated to 37,360 patient-years of metformin use in studies that included patients with chronic kidney disease, and did not lead to lactic acidosis.

Even though metformin’s US package insert says that it is contraindicated if the serum creatinine level is 1.5 mg/dL or higher in men or 1.4 mg/dL or higher in women or if the creatinine clearance is “abnormal,” in view of the available evidence, many countries (eg, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands) now allow metformin to be used in patients with glomerular filtration rates as low as 30 mL/min/1.73m2, with lower doses if the glomerular filtration rate is lower than 45.5

The current contraindication to metformin in chronic kidney disease needs to be reviewed. In poor countries like India, this cheap medicine may be the only option available for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus, and it remains the first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus as recommended by the International Diabetes Federation, the American Diabetes Association, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.5

To the Editor: In their article about the care of patients with advanced chronic kidney disease, Sakhuja et al1 mentioned that metformin is contraindicated in chronic kidney disease.

Metformin is a good and useful drug. Not only is it one of the cheapest antidiabetic medications, it is the only one shown to reduce cardiovascular mortality rates in type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Although metformin is thought to increase the risk of lactic acidosis, a Cochrane review2 found that the incidence of lactic acidosis was only 4.3 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients taking metformin, compared with 5.4 cases per 100,000 patient-years in patients not taking metformin. Furthermore, in a large registry of patients with type 2 diabetes and atherothrombosis,3 the rate of all-cause mortality was 24% lower in metformin users than in nonusers, and in those who had moderate renal impairment (creatinine clearance 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2) the difference was 36%.3

A trial by Rachmani et al4 raised questions about the standard contraindications to metformin. The authors reviewed 393 patients who had at least one contraindication to metformin but who were receiving it anyway. Their serum creatinine levels ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 mg/dL. There were no cases of lactic acidosis reported. The patients were then randomized either to continue taking metformin or to stop taking it. At 2 years, the group that had stopped taking it had gained more weight, and their glycemic control was worse.

In the Cochrane analysis,2 although individual creatinine levels were not available, 53% of the studies reviewed did not exclude patients with serum creatinine levels higher than 1.5 mg/dL. This equated to 37,360 patient-years of metformin use in studies that included patients with chronic kidney disease, and did not lead to lactic acidosis.

Even though metformin’s US package insert says that it is contraindicated if the serum creatinine level is 1.5 mg/dL or higher in men or 1.4 mg/dL or higher in women or if the creatinine clearance is “abnormal,” in view of the available evidence, many countries (eg, the United Kingdom, Australia, the Netherlands) now allow metformin to be used in patients with glomerular filtration rates as low as 30 mL/min/1.73m2, with lower doses if the glomerular filtration rate is lower than 45.5

The current contraindication to metformin in chronic kidney disease needs to be reviewed. In poor countries like India, this cheap medicine may be the only option available for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus, and it remains the first-line therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus as recommended by the International Diabetes Federation, the American Diabetes Association, and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.5

- Sakhuja A, Hyland J, Simon JF. Managing advanced chronic kidney disease: a primary care guide. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:289–299.

- Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 4:CD002967.

- Roussel R, Travert F, Pasquet B, et al; Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry Investigators. Metformin use and mortality among patients with diabetes and atherothrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:1892–1899.

- Rachmani R, Slavachevski I, Levi Z, Zadok B, Kedar Y, Ravid M. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: reconsideration of traditional contraindications. Eur J Intern Med 2002; 13:428–433.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35:1364–1379.

- Sakhuja A, Hyland J, Simon JF. Managing advanced chronic kidney disease: a primary care guide. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:289–299.

- Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010; 4:CD002967.

- Roussel R, Travert F, Pasquet B, et al; Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry Investigators. Metformin use and mortality among patients with diabetes and atherothrombosis. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170:1892–1899.

- Rachmani R, Slavachevski I, Levi Z, Zadok B, Kedar Y, Ravid M. Metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: reconsideration of traditional contraindications. Eur J Intern Med 2002; 13:428–433.

- Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al; American Diabetes Association (ADA); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2012; 35:1364–1379.

In reply: Why is metformin contraindicated in chronic kidney disease?

In Reply: We appreciate Dr. Imam’s comments regarding using metformin in those with chronic kidney disease.

The US Food and Drug Administration currently lists metformin as contraindicated in those with mild to moderate renal insufficiency, with serum creatinine levels greater than or equal to 1.5 mg/dL in males and greater than or equal to 1.4 mg/dL in females. This contraindication is based on the pharmacokinetics of the medication and, likely, the association of a similar medication, phenformin, with lactic acidosis, which eventually led to its withdrawal from the market. However, lactic acidosis is much less frequent with metformin than with phenformin.1

We agree that metformin is an invaluable medication for diabetes mellitus not requiring insulin. We also agree that lactic acidosis is rare, especially in those with mild renal insufficiency. However, lactic acidosis does occur in patients with chronic kidney disease while on metformin and, however rare, when it does occur it is a life-threatening event.2

The clearance of metformin is strongly dependent on kidney function,3 and therefore guidelines still recommend reducing the dose in those with moderate renal insufficiency and recommend considering stopping the medication in those with severe renal insufficiency—the population we were talking about in our article.4 We are aware of changes to the guidelines that have been made by various groups, and in many circumstances we ourselves take an individualized approach, weighing the risks and benefits of continued therapy with the patient and his or her primary care provider. That being said, we did not believe that such nuanced recommendations were appropriate for our article, especially since they are contrary to marketing restrictions for the drug.

- Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:574–579.

- Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. Prognostic value of arterial lactate levels and plasma metformin concentrations. Drug Saf 1999; 20:377–384.

- Sambol NC, Chiang J, Lin ET, et al. Kidney function and age are both predictors of pharmacokinetics of metformin. J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 35:1094–1102.

- Sakhuja A, Hyland J, Simon JF. Managing advanced chronic kidney disease: a primary care guide. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:289–299.

In Reply: We appreciate Dr. Imam’s comments regarding using metformin in those with chronic kidney disease.

The US Food and Drug Administration currently lists metformin as contraindicated in those with mild to moderate renal insufficiency, with serum creatinine levels greater than or equal to 1.5 mg/dL in males and greater than or equal to 1.4 mg/dL in females. This contraindication is based on the pharmacokinetics of the medication and, likely, the association of a similar medication, phenformin, with lactic acidosis, which eventually led to its withdrawal from the market. However, lactic acidosis is much less frequent with metformin than with phenformin.1

We agree that metformin is an invaluable medication for diabetes mellitus not requiring insulin. We also agree that lactic acidosis is rare, especially in those with mild renal insufficiency. However, lactic acidosis does occur in patients with chronic kidney disease while on metformin and, however rare, when it does occur it is a life-threatening event.2

The clearance of metformin is strongly dependent on kidney function,3 and therefore guidelines still recommend reducing the dose in those with moderate renal insufficiency and recommend considering stopping the medication in those with severe renal insufficiency—the population we were talking about in our article.4 We are aware of changes to the guidelines that have been made by various groups, and in many circumstances we ourselves take an individualized approach, weighing the risks and benefits of continued therapy with the patient and his or her primary care provider. That being said, we did not believe that such nuanced recommendations were appropriate for our article, especially since they are contrary to marketing restrictions for the drug.

In Reply: We appreciate Dr. Imam’s comments regarding using metformin in those with chronic kidney disease.

The US Food and Drug Administration currently lists metformin as contraindicated in those with mild to moderate renal insufficiency, with serum creatinine levels greater than or equal to 1.5 mg/dL in males and greater than or equal to 1.4 mg/dL in females. This contraindication is based on the pharmacokinetics of the medication and, likely, the association of a similar medication, phenformin, with lactic acidosis, which eventually led to its withdrawal from the market. However, lactic acidosis is much less frequent with metformin than with phenformin.1

We agree that metformin is an invaluable medication for diabetes mellitus not requiring insulin. We also agree that lactic acidosis is rare, especially in those with mild renal insufficiency. However, lactic acidosis does occur in patients with chronic kidney disease while on metformin and, however rare, when it does occur it is a life-threatening event.2

The clearance of metformin is strongly dependent on kidney function,3 and therefore guidelines still recommend reducing the dose in those with moderate renal insufficiency and recommend considering stopping the medication in those with severe renal insufficiency—the population we were talking about in our article.4 We are aware of changes to the guidelines that have been made by various groups, and in many circumstances we ourselves take an individualized approach, weighing the risks and benefits of continued therapy with the patient and his or her primary care provider. That being said, we did not believe that such nuanced recommendations were appropriate for our article, especially since they are contrary to marketing restrictions for the drug.

- Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:574–579.

- Lalau JD, Race JM. Lactic acidosis in metformin-treated patients. Prognostic value of arterial lactate levels and plasma metformin concentrations. Drug Saf 1999; 20:377–384.

- Sambol NC, Chiang J, Lin ET, et al. Kidney function and age are both predictors of pharmacokinetics of metformin. J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 35:1094–1102.

- Sakhuja A, Hyland J, Simon JF. Managing advanced chronic kidney disease: a primary care guide. Cleve Clin J Med 2014; 81:289–299.

- Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:574–579.