User login

Bench-to-bedside challenges in developing immune protection against breast cancer

The most proven, effective way to control disease is through prophylactic vaccination. The childhood vaccination program is a testament to this disease prevention approach, and in its current form protects us from diseases caused by 16 different pathogens.1

Childhood immunization ends in the teen years with recommended vaccination against multiple strains of human papillomavirus that are associated with several cancers, most notably cervical carcinoma.2 However, even though we have known for over 30 years that the immune system can provide considerable vaccine-induced protection against the development of cancer,3 we have not produced any vaccines that prevent cancers that commonly occur with age, such as breast and prostate cancer, which afflict 1 of 8 women and 1 of 6 men, respectively.4,5

The lack of an adult vaccine program that provides protection against such commonly occurring adult-onset cancers represents a glaring health care deficiency and a challenge for this current generation to protect coming generations.

THE ‘RETIRED’ PROTEIN HYPOTHESIS

Given that most cancers are not associated with any disease-inducing pathogens, at what targets can we aim our immune system to induce safe and effective protection against these commonly occurring adult-onset cancers?

Perhaps an understanding of the natural aging process may provide us with insights regarding possible vaccine targets. As we age, there is a decline in expression of many tissue-specific proteins, often to the point where they may be considered “retired” and no longer found at detectable or immunogenic levels in normal cells. Examples of this natural aging process include the pigment proteins as our hair whitens, certain lactation proteins when breastfeeding ceases, and some ovarian proteins as menopause begins and production of mature egg follicles ceases. If these retired proteins are expressed in invigorated emerging tumors, then preemptive immunity directed against these retired proteins would attack and destroy the emerging tumors and ignore normal tissues, thereby avoiding any complicating collateral autoimmune damage.

Thus, we propose that retired tissue-specific self-proteins may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for mediating safe and effective immune protection against adult-onset cancers such as breast cancer.

SAFE AND EFFECTIVE PREVENTION OF BREAST CANCER IN MICE

To test this retired-protein hypothesis for immunoprevention of breast cancer, we selected alpha-lactalbumin as our vaccine target, for two reasons:

- Alpha-lactalbumin is a protein expressed exclusively in lactating breast tissue and is not expressed at immunogenic levels in either normal nonlactating breast tissues or in any of 78 other normal human tissues examined.6–8

- Alpha-lactalbumin is expressed in most human triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC),9,10 the most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer, and the predominant form that occurs in women with mutations in the breast cancer 1, early-onset gene (BRCA1).11,12

We found that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination consistently inhibited the formation and growth of breast tumors in three different mouse models commonly used in breast cancer research.13 More importantly, the observed immune protection against the development of breast cancer in mice occurred in the absence of any detectable autoimmune inflammatory damage in any normal tissues examined. Thus, we concluded that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination could provide healthy women with safe and effective immune protection against the more malignant forms of breast cancer.

FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

How then do we determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination prevents the development of TNBC in otherwise healthy cancer-free women, and whether it prevents recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with TNBC? Our initial approach will involve two phase 1 clinical trials designed to determine the safety of the vaccine as well as the dose and number of vaccinations needed to induce optimum tumor immunity.

The first (phase 1a) trial will involve vaccination of women recently diagnosed with TNBC who have recovered with the current standard of care. These women will be vaccinated in groups receiving various doses of both recombinant human alpha-lactalbumin and an appropriate immune adjuvant that activates the immune system so it responds aggressively to the alpha-lactalbumin and creates the proinflammatory T-cell response needed for effective tumor immunity. This trial will simply provide dosage and safety profiles of the vaccine and will thereby lay the groundwork for subsequent (phase 2 and 3) trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease.

The dosage and number of immunizations shown to provide optimum immunity in the phase 1a trial will be used in a second (phase 1b) trial designed primarily to determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women who have elected to undergo voluntary prophylactic mastectomy to reduce their breast cancer risk. Most of the women who elect to have this surgery have an established family history of breast cancer or a known BRCA1 mutation associated with high breast cancer risk, or both.11,12 Consenting women will be vaccinated against alpha-lactalbumin several months before their mastectomy, and their surgically removed breast tissues will be examined extensively for signs of vaccine-induced autoimmune damage. Thus, this trial will determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women and will lay the groundwork for subsequent phase 2 and 3 trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing TNBC in women at high risk of developing this form of breast cancer.

We estimate that completing our preclinical studies, obtaining permission from the US Food and Drug Administration to test our investigational new drug, and completing both phase 1 clinical trials will require about 5 years. Thereafter, completion of phase 2 and 3 trials designed to prevent both recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and occurrence of TNBC in otherwise healthy, cancer-free women will likely take at least another 5 years, so that this vaccine will likely not be available to the general public before 2024.

TO SUM UP

Although our immune system is potentially capable of protecting us from some cancers, we currently have no immune protection against cancers we commonly confront as we age. We propose that tissue-specific self proteins that are retired from expression with age in normal tissues but are expressed at immunogenic levels in emerging tumors may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for immunoprevention of adult-onset cancers that commonly occur with age. We know that the retired breast-specific protein, alpha-lactalbumin, is overexpressed in TNBC and that vaccination with alpha-lactalbumin provides safe and effective protection from breast cancer in preclinical mouse studies. Clinical trials are planned to ultimately determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination can prevent recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and prevent the initiation of TNBC in women at high risk of developing this most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer.

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by a grant from Shield Biotech, Inc., Cleveland, OH. In addition, the author wishes to recognize and express his sincere gratitude for the support and encouragement received from numerous organizations that have been instrumental in making this work possible, including November Philanthropy, Brakes for Breasts, the Breast Health and Healing Foundation, the Toni Turchi Foundation, the Coalition of Women Who Care About Breast Cancer, the Sisters for Prevention, the Previvors and Survivors, the Champions of the Pink Vaccine, the Race at Legacy Village, the National Greek Orthodox Ladies Philopto-chos Society, the Daughters of Penelope Icarus Chapter 321, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, the Babylon Breast Cancer Coalition, and Walk With A Doc.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization schedules. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10:681–692.

- Van Pel A, Boon T. Protection against a nonimmunogenic mouse leukemia by an immunogenic variant obtained by mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79:4718–4722.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63:11–30.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Previous version: SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:1248–1250.

- Pontén F, Gry M, Fagerberg L, et al. A global view of protein expression in human cells, tissues, and organs. Mol Syst Biol 2009; 5:337.

- The Human Protein Atlas. www.proteinatlas.org. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia 2004; 6:1–6.

- ONCOMINEdatabase. www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:4282–4288.

- Comen E, Davids M, Kirchhoff T, Hudis C, Offit K, Robson M. Relative contributions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to “triple-negative” breast cancer in Ashkenazi women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 129:185–190.

- Jaini R, Kesaraju P, Johnson JM, Altuntas CZ, Jane-Wit D, Tuohy VK. An autoimmune-mediated strategy for prophylactic breast cancer vaccination. Nat Med 2010; 16:799–803.

The most proven, effective way to control disease is through prophylactic vaccination. The childhood vaccination program is a testament to this disease prevention approach, and in its current form protects us from diseases caused by 16 different pathogens.1

Childhood immunization ends in the teen years with recommended vaccination against multiple strains of human papillomavirus that are associated with several cancers, most notably cervical carcinoma.2 However, even though we have known for over 30 years that the immune system can provide considerable vaccine-induced protection against the development of cancer,3 we have not produced any vaccines that prevent cancers that commonly occur with age, such as breast and prostate cancer, which afflict 1 of 8 women and 1 of 6 men, respectively.4,5

The lack of an adult vaccine program that provides protection against such commonly occurring adult-onset cancers represents a glaring health care deficiency and a challenge for this current generation to protect coming generations.

THE ‘RETIRED’ PROTEIN HYPOTHESIS

Given that most cancers are not associated with any disease-inducing pathogens, at what targets can we aim our immune system to induce safe and effective protection against these commonly occurring adult-onset cancers?

Perhaps an understanding of the natural aging process may provide us with insights regarding possible vaccine targets. As we age, there is a decline in expression of many tissue-specific proteins, often to the point where they may be considered “retired” and no longer found at detectable or immunogenic levels in normal cells. Examples of this natural aging process include the pigment proteins as our hair whitens, certain lactation proteins when breastfeeding ceases, and some ovarian proteins as menopause begins and production of mature egg follicles ceases. If these retired proteins are expressed in invigorated emerging tumors, then preemptive immunity directed against these retired proteins would attack and destroy the emerging tumors and ignore normal tissues, thereby avoiding any complicating collateral autoimmune damage.

Thus, we propose that retired tissue-specific self-proteins may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for mediating safe and effective immune protection against adult-onset cancers such as breast cancer.

SAFE AND EFFECTIVE PREVENTION OF BREAST CANCER IN MICE

To test this retired-protein hypothesis for immunoprevention of breast cancer, we selected alpha-lactalbumin as our vaccine target, for two reasons:

- Alpha-lactalbumin is a protein expressed exclusively in lactating breast tissue and is not expressed at immunogenic levels in either normal nonlactating breast tissues or in any of 78 other normal human tissues examined.6–8

- Alpha-lactalbumin is expressed in most human triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC),9,10 the most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer, and the predominant form that occurs in women with mutations in the breast cancer 1, early-onset gene (BRCA1).11,12

We found that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination consistently inhibited the formation and growth of breast tumors in three different mouse models commonly used in breast cancer research.13 More importantly, the observed immune protection against the development of breast cancer in mice occurred in the absence of any detectable autoimmune inflammatory damage in any normal tissues examined. Thus, we concluded that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination could provide healthy women with safe and effective immune protection against the more malignant forms of breast cancer.

FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

How then do we determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination prevents the development of TNBC in otherwise healthy cancer-free women, and whether it prevents recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with TNBC? Our initial approach will involve two phase 1 clinical trials designed to determine the safety of the vaccine as well as the dose and number of vaccinations needed to induce optimum tumor immunity.

The first (phase 1a) trial will involve vaccination of women recently diagnosed with TNBC who have recovered with the current standard of care. These women will be vaccinated in groups receiving various doses of both recombinant human alpha-lactalbumin and an appropriate immune adjuvant that activates the immune system so it responds aggressively to the alpha-lactalbumin and creates the proinflammatory T-cell response needed for effective tumor immunity. This trial will simply provide dosage and safety profiles of the vaccine and will thereby lay the groundwork for subsequent (phase 2 and 3) trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease.

The dosage and number of immunizations shown to provide optimum immunity in the phase 1a trial will be used in a second (phase 1b) trial designed primarily to determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women who have elected to undergo voluntary prophylactic mastectomy to reduce their breast cancer risk. Most of the women who elect to have this surgery have an established family history of breast cancer or a known BRCA1 mutation associated with high breast cancer risk, or both.11,12 Consenting women will be vaccinated against alpha-lactalbumin several months before their mastectomy, and their surgically removed breast tissues will be examined extensively for signs of vaccine-induced autoimmune damage. Thus, this trial will determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women and will lay the groundwork for subsequent phase 2 and 3 trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing TNBC in women at high risk of developing this form of breast cancer.

We estimate that completing our preclinical studies, obtaining permission from the US Food and Drug Administration to test our investigational new drug, and completing both phase 1 clinical trials will require about 5 years. Thereafter, completion of phase 2 and 3 trials designed to prevent both recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and occurrence of TNBC in otherwise healthy, cancer-free women will likely take at least another 5 years, so that this vaccine will likely not be available to the general public before 2024.

TO SUM UP

Although our immune system is potentially capable of protecting us from some cancers, we currently have no immune protection against cancers we commonly confront as we age. We propose that tissue-specific self proteins that are retired from expression with age in normal tissues but are expressed at immunogenic levels in emerging tumors may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for immunoprevention of adult-onset cancers that commonly occur with age. We know that the retired breast-specific protein, alpha-lactalbumin, is overexpressed in TNBC and that vaccination with alpha-lactalbumin provides safe and effective protection from breast cancer in preclinical mouse studies. Clinical trials are planned to ultimately determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination can prevent recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and prevent the initiation of TNBC in women at high risk of developing this most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer.

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by a grant from Shield Biotech, Inc., Cleveland, OH. In addition, the author wishes to recognize and express his sincere gratitude for the support and encouragement received from numerous organizations that have been instrumental in making this work possible, including November Philanthropy, Brakes for Breasts, the Breast Health and Healing Foundation, the Toni Turchi Foundation, the Coalition of Women Who Care About Breast Cancer, the Sisters for Prevention, the Previvors and Survivors, the Champions of the Pink Vaccine, the Race at Legacy Village, the National Greek Orthodox Ladies Philopto-chos Society, the Daughters of Penelope Icarus Chapter 321, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, the Babylon Breast Cancer Coalition, and Walk With A Doc.

The most proven, effective way to control disease is through prophylactic vaccination. The childhood vaccination program is a testament to this disease prevention approach, and in its current form protects us from diseases caused by 16 different pathogens.1

Childhood immunization ends in the teen years with recommended vaccination against multiple strains of human papillomavirus that are associated with several cancers, most notably cervical carcinoma.2 However, even though we have known for over 30 years that the immune system can provide considerable vaccine-induced protection against the development of cancer,3 we have not produced any vaccines that prevent cancers that commonly occur with age, such as breast and prostate cancer, which afflict 1 of 8 women and 1 of 6 men, respectively.4,5

The lack of an adult vaccine program that provides protection against such commonly occurring adult-onset cancers represents a glaring health care deficiency and a challenge for this current generation to protect coming generations.

THE ‘RETIRED’ PROTEIN HYPOTHESIS

Given that most cancers are not associated with any disease-inducing pathogens, at what targets can we aim our immune system to induce safe and effective protection against these commonly occurring adult-onset cancers?

Perhaps an understanding of the natural aging process may provide us with insights regarding possible vaccine targets. As we age, there is a decline in expression of many tissue-specific proteins, often to the point where they may be considered “retired” and no longer found at detectable or immunogenic levels in normal cells. Examples of this natural aging process include the pigment proteins as our hair whitens, certain lactation proteins when breastfeeding ceases, and some ovarian proteins as menopause begins and production of mature egg follicles ceases. If these retired proteins are expressed in invigorated emerging tumors, then preemptive immunity directed against these retired proteins would attack and destroy the emerging tumors and ignore normal tissues, thereby avoiding any complicating collateral autoimmune damage.

Thus, we propose that retired tissue-specific self-proteins may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for mediating safe and effective immune protection against adult-onset cancers such as breast cancer.

SAFE AND EFFECTIVE PREVENTION OF BREAST CANCER IN MICE

To test this retired-protein hypothesis for immunoprevention of breast cancer, we selected alpha-lactalbumin as our vaccine target, for two reasons:

- Alpha-lactalbumin is a protein expressed exclusively in lactating breast tissue and is not expressed at immunogenic levels in either normal nonlactating breast tissues or in any of 78 other normal human tissues examined.6–8

- Alpha-lactalbumin is expressed in most human triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC),9,10 the most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer, and the predominant form that occurs in women with mutations in the breast cancer 1, early-onset gene (BRCA1).11,12

We found that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination consistently inhibited the formation and growth of breast tumors in three different mouse models commonly used in breast cancer research.13 More importantly, the observed immune protection against the development of breast cancer in mice occurred in the absence of any detectable autoimmune inflammatory damage in any normal tissues examined. Thus, we concluded that alpha-lactalbumin vaccination could provide healthy women with safe and effective immune protection against the more malignant forms of breast cancer.

FROM BENCH TO BEDSIDE

How then do we determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination prevents the development of TNBC in otherwise healthy cancer-free women, and whether it prevents recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with TNBC? Our initial approach will involve two phase 1 clinical trials designed to determine the safety of the vaccine as well as the dose and number of vaccinations needed to induce optimum tumor immunity.

The first (phase 1a) trial will involve vaccination of women recently diagnosed with TNBC who have recovered with the current standard of care. These women will be vaccinated in groups receiving various doses of both recombinant human alpha-lactalbumin and an appropriate immune adjuvant that activates the immune system so it responds aggressively to the alpha-lactalbumin and creates the proinflammatory T-cell response needed for effective tumor immunity. This trial will simply provide dosage and safety profiles of the vaccine and will thereby lay the groundwork for subsequent (phase 2 and 3) trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease.

The dosage and number of immunizations shown to provide optimum immunity in the phase 1a trial will be used in a second (phase 1b) trial designed primarily to determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women who have elected to undergo voluntary prophylactic mastectomy to reduce their breast cancer risk. Most of the women who elect to have this surgery have an established family history of breast cancer or a known BRCA1 mutation associated with high breast cancer risk, or both.11,12 Consenting women will be vaccinated against alpha-lactalbumin several months before their mastectomy, and their surgically removed breast tissues will be examined extensively for signs of vaccine-induced autoimmune damage. Thus, this trial will determine the safety of alpha-lactalbumin vaccination in healthy cancer-free women and will lay the groundwork for subsequent phase 2 and 3 trials designed to determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination is effective in preventing TNBC in women at high risk of developing this form of breast cancer.

We estimate that completing our preclinical studies, obtaining permission from the US Food and Drug Administration to test our investigational new drug, and completing both phase 1 clinical trials will require about 5 years. Thereafter, completion of phase 2 and 3 trials designed to prevent both recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and occurrence of TNBC in otherwise healthy, cancer-free women will likely take at least another 5 years, so that this vaccine will likely not be available to the general public before 2024.

TO SUM UP

Although our immune system is potentially capable of protecting us from some cancers, we currently have no immune protection against cancers we commonly confront as we age. We propose that tissue-specific self proteins that are retired from expression with age in normal tissues but are expressed at immunogenic levels in emerging tumors may substitute for unavailable pathogens as targets for immunoprevention of adult-onset cancers that commonly occur with age. We know that the retired breast-specific protein, alpha-lactalbumin, is overexpressed in TNBC and that vaccination with alpha-lactalbumin provides safe and effective protection from breast cancer in preclinical mouse studies. Clinical trials are planned to ultimately determine whether alpha-lactalbumin vaccination can prevent recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease and prevent the initiation of TNBC in women at high risk of developing this most aggressive and lethal form of breast cancer.

Acknowledgment: This work was supported by a grant from Shield Biotech, Inc., Cleveland, OH. In addition, the author wishes to recognize and express his sincere gratitude for the support and encouragement received from numerous organizations that have been instrumental in making this work possible, including November Philanthropy, Brakes for Breasts, the Breast Health and Healing Foundation, the Toni Turchi Foundation, the Coalition of Women Who Care About Breast Cancer, the Sisters for Prevention, the Previvors and Survivors, the Champions of the Pink Vaccine, the Race at Legacy Village, the National Greek Orthodox Ladies Philopto-chos Society, the Daughters of Penelope Icarus Chapter 321, Can’t Stop Won’t Stop, the Babylon Breast Cancer Coalition, and Walk With A Doc.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization schedules. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10:681–692.

- Van Pel A, Boon T. Protection against a nonimmunogenic mouse leukemia by an immunogenic variant obtained by mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79:4718–4722.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63:11–30.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Previous version: SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:1248–1250.

- Pontén F, Gry M, Fagerberg L, et al. A global view of protein expression in human cells, tissues, and organs. Mol Syst Biol 2009; 5:337.

- The Human Protein Atlas. www.proteinatlas.org. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia 2004; 6:1–6.

- ONCOMINEdatabase. www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:4282–4288.

- Comen E, Davids M, Kirchhoff T, Hudis C, Offit K, Robson M. Relative contributions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to “triple-negative” breast cancer in Ashkenazi women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 129:185–190.

- Jaini R, Kesaraju P, Johnson JM, Altuntas CZ, Jane-Wit D, Tuohy VK. An autoimmune-mediated strategy for prophylactic breast cancer vaccination. Nat Med 2010; 16:799–803.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization schedules. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Schiller JT, Lowy DR. Understanding and learning from the success of prophylactic human papillomavirus vaccines. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012; 10:681–692.

- Van Pel A, Boon T. Protection against a nonimmunogenic mouse leukemia by an immunogenic variant obtained by mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1982; 79:4718–4722.

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63:11–30.

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. Previous version: SEER cancer statistics review 1975–2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2010/. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Uhlen M, Oksvold P, Fagerberg L, et al. Towards a knowledge-based human protein atlas. Nat Biotechnol 2010; 28:1248–1250.

- Pontén F, Gry M, Fagerberg L, et al. A global view of protein expression in human cells, tissues, and organs. Mol Syst Biol 2009; 5:337.

- The Human Protein Atlas. www.proteinatlas.org. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia 2004; 6:1–6.

- ONCOMINEdatabase. www.oncomine.org/resource/login.html. Accessed September 4, 2014.

- Atchley DP, Albarracin CT, Lopez A, et al. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of patients with BRCA-positive and BRCA-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26:4282–4288.

- Comen E, Davids M, Kirchhoff T, Hudis C, Offit K, Robson M. Relative contributions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations to “triple-negative” breast cancer in Ashkenazi women. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011; 129:185–190.

- Jaini R, Kesaraju P, Johnson JM, Altuntas CZ, Jane-Wit D, Tuohy VK. An autoimmune-mediated strategy for prophylactic breast cancer vaccination. Nat Med 2010; 16:799–803.

KEY POINTS

- “Retired” tissue-specific self proteins may substitute for unavailable pathogens as vaccine targets for mediating immune prevention of adult-onset cancers.

- Vaccination against the retired breast-specific protein alpha-lactalbumin provides safe and effective immune protection against the development of breast tumors in several mouse models.

- Alpha-lactalbumin is overexpressed in most human triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC), the most aggressive and lethal form of human breast cancer.

- Forthcoming are clinical trials designed to prevent the initiation of TNBC in otherwise healthy cancer-free women, as well as trials designed to prevent recurrence of TNBC in women already diagnosed with this disease.

Diabetes therapy and cancer risk: Where do we stand when treating patients?

In the last quarter century, many new drugs have become available for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists incorporated these new agents in its updated glycemic control algorithm in 2013.1 Because diabetes affects 25.8 million Americans and can lead to blindness, renal failure, cardiovascular disease, and amputation, agents that help us treat it more effectively are valuable.2

One of the barriers to effective treatment is the side effects of the agents. Because some of these drugs have been in use for only a short time, concerns of potential adverse effects have arisen. Cancer is one such concern, especially since type 2 diabetes mellitus by itself increases the risk of cancer by 20% to 50% compared with no diabetes.3

Type 2 diabetes has been linked to risk of cancers of the pancreas,4 colorectum,5,6 liver,7 kidney,8,9 breast,10 bladder,11 and endometri-um,12 as well as to hematologic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma.13 The risk of bladder cancer appears to depend on how long the patient has had type 2 diabetes. Newton et al,14 in a prospective cohort study, found that those who had diabetes for more than 15 years and used insulin had the highest risk of bladder cancer. On the other hand, the risk of prostate cancer is actually lower in people with diabetes,15 particularly in those who have had diabetes for longer than 4 years.16

Cancer and type 2 diabetes share many risk factors and underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. Nonmodifiable risk factors for both diseases include advanced age, male sex, ethnicity (African American men appear to be most vulnerable to both cancer and diabetes),17,18 and family history. Modifiable risk factors include lower socioeconomic status, obesity, and alcohol consumption. These common risk factors lead to hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, changes in mitochondrial function, low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress,3 which promote both diabetes and cancer. Diabetes therapy may influence several of these processes.

Several classes of diabetes drugs, including exogenous insulin,19–22 insulin secretagogues,23–25 and incretin-based therapies,26–28 have been under scrutiny because of their potential influences on cancer development in a population already at risk (Table 1).

INSULIN ANALOGUES: MIXED EVIDENCE

Insulin promotes cell division by binding to insulin receptor isoform A and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors.29 Because endogenous hyperinsulinemia has been linked to cancer risk, growth, and proliferation, some speculate that exogenous insulin may also increase cancer risk.

In 2009, a retrospective study by Hemkens et al linked the long-acting insulin analogue glargine to risk of cancer.19 This finding set off a tumult of controversy within the medical community and concern among patients. Several limitations of the study were brought to light, including a short duration of follow-up, and several other studies have refuted the study’s findings.20,21

More recently, the Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial22 found no higher cancer risk with glargine use than with placebo. This study enrolled 12,537 participants from 573 sites in 40 countries. Specifically, risks with glargine use were as follows:

- Any cancer—hazard ratio 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88–1.13, P = .97

- Cancer death—hazard ratio 0.94, 95% CI 0.77–1.15, P = .52.

However, the study was designed to assess cardiovascular outcomes, not cancer risk. Furthermore, the participants were not typical of patients seen in clinical practice: their insulin doses were lower (the median insulin dose was 0.4 units/kg/day by year 6, whereas in clinical practice, those with type 2 diabetes mellitus often use more than 1 unit/kg/day, depending on duration of diabetes, diet, and exercise regimen), and their baseline median hemoglobin A1c level was only 6.4%. And one may argue that the median follow-up of 6.2 years was too short for cancer to develop.22

In vitro studies indicate that long-acting analogue insulin therapy may promote cancer cell growth more than endogenous insulin,30 but epidemiologic data have not unequivocally substantiated this.20–22 There is no clear evidence that analogue insulin therapy raises cancer risk above that of human recombinant insulin, and starting insulin therapy should not be delayed because of concerns about cancer risk, particularly in uncontrolled diabetes.

INSULIN SECRETAGOGUES

Sulfonylureas: Higher risk

Before 1995, only two classes of diabetes drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—insulin and sulfonylureas.

Sulfonylureas lower blood sugar levels by binding to sulfonylurea receptors and inhibiting adenosine triphosphate-dependent potassium channels. The resulting change in resting potential causes an influx of calcium, ultimately leading to insulin secretion.

Sulfonylureas are effective, and because of their low cost, physicians often pick them as a second-line agent after metformin.

The main disadvantage of sulfonylureas is the risk of hypoglycemia, particularly in patients with renal failure, the elderly, and diabetic patients who are unaware of when they are hypoglycemic. Other potential drawbacks are that they impair cardiac ischemic preconditioning31 and possibly increase cancer risk.21,32 (Ischemic preconditioning is the process in which transient episodes of ischemia “condition” the myocardium so that it better withstands future episodes with minimal anginal pain and tissue injury.33) Of the sulfonylureas, glyburide has been most implicated in cardiovascular risk.32

In a retrospective cohort study of 62,809 patients from a general-practice database in the United Kingdom, Currie et al21 found that sulfonylurea monotherapy was associated with a 36% higher risk of cancer (95% CI 1.19–1.54, P < .001) than metformin monotherapy. Prescribing bias may have influenced the results: practitioners are more likely to prescribe sulfonylureas to leaner patients, who have a greater likelihood of occult cancer. However, other studies also found that the cancer death rate is higher in those who take a sulfonylurea alone than in those who use metformin alone.23,24

Some evidence indicates that long-acting sulfonylurea formulations (eg, glyburide) likely hold the most danger, certainly in regard to hypoglycemia, but it is less clear if this translates to cancer concerns.31

Meglitinides: Limited evidence

Meglitinides, the other class of insulin secretagogues, are less commonly used but are similar to sulfonylureas in the way they increase endogenous insulin levels. The data are limited regarding cancer risk and meglitinide therapy, but the magnitude of the association is similar to that with sulfonylurea therapy.25

INSULIN SENSITIZERS

There are currently two classes of insulin sensitizers: biguanides and thiazolidinediones (TZDs, also known as glitazones). These drugs show less risk of both cancer incidence and cancer death than insulin secretagogues such as sulfonylureas.21,23,24 In fact, they may decrease cancer potential by alteration of signaling via the AKT/mTOR (v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway.34

Metformin, a biguanide, is the oral drug of choice

Metformin is the only biguanide currently available in the United States. It was approved by the FDA in 1995, although it had been in clinical use since the 1950s. Inexpensive and familiar, it is the oral antihyperglycemic of choice if there are no contraindications to it, such as renal dysfunction (creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL in women and ≥ 1.5 mg/dL in men), acute decompensated heart failure, or pulmonary or hepatic insufficiency, all of which may lead to an increased risk of lactic acidosis.1

Metformin lowers blood sugar levels primarily by inhibiting hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis) and by improving peripheral insulin sensitivity. It directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which affects insulin signaling and glucose and fat metabolism.35 It may exert further beneficial effects by acutely increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels and inducing islet incretin-receptor gene expression.36 Although the exact mechanisms have not been fully elucidated, metformin’s insulin-sensitizing properties are likely from favorable effects on insulin receptor expression, tyrosine kinase activity, and influences on the incretin pathway.36,37 These effects also mitigate carcinogenesis, both directly (via AMPK and liver kinase B1, a tumor-suppressor gene) and indirectly (via reduction of hyperinsulinemia).35

Overall, biguanide therapy is associated with a lower cancer incidence or, at worst, no effect on cancer incidence. In vitro studies demonstrate that metformin both suppresses cancer cell growth and induces apoptosis, resulting in fewer live cancer cells.34 Several retrospective studies found lower cancer risk in metformin users than in patients receiving antidiabetes drugs other than insulin-sensitizing agents,21,23,25,38–40 while others have shown no effect.41 Use of metformin was specifically associated with lower risk of cancers of the liver, colon and rectum, and lung.42 Further, metformin users have a lower cancer mortality rate than nonusers.24,43

Thiazolidinediones

TZDs, such as pioglitazone, work by binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated gamma receptors in the cell nucleus, altering gene transcription.44 They reduce insulin resistance and levels of endogenous insulin levels and free fatty acids.44

Concern over bladder cancer risk with TZD use, particularly with pioglitazone, has increased in the last few years, as various cohort studies found a statistically significant increased risk with this agent.44 The risk appears to rise with cumulative dose.45,46

Randomized controlled trials also found an increased risk of bladder cancer with TZD therapy, although the difference was not statistically significant.47–49 In a mean follow-up of 8.7 years, the Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular Events reported 23 cases of bladder cancer in the pioglitazone group vs 22 cases in the placebo group, for rates of 0.9% vs 0.8% (relative risk [RR] 1.06, 95% CI 0.59–1.89).49

On the other hand, the risk of cancer of the breast, colon, and lung has been found to be lower with TZD use.47 In vitro studies support the clinical data, showing that TZDs inhibit growth of human cancer cells derived from cancers of the lung, colon, breast, stomach, ovary, and prostate.50–53

Home et al54 compared rosiglitazone against a sulfonylurea in patients already taking metformin in the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiovascular Outcomes in Oral Agent Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes (RECORD) trial. Malignancies developed in 6.7% of the sulfonylurea group compared with 5.1% of the rosiglitazone group, for a hazard ratio of 1.33 (95% CI 0.94–1.88).

Both ADOPT (A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial) and the RECORD trial found rosiglitazone comparable to metformin in terms of cancer risk.54

Colmers et al47 pooled data from four randomized controlled trials, seven cohort studies, and nine case-control studies to assess the risk of cancer with TZD use in type 2 diabetes. Both the randomized and observational data showed neutral overall cancer risk with TZDs. However, pooled data from observational studies showed significantly lower risk with TZD use in terms of:

- Colorectal cancer RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.87–1.00

- Lung cancer RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84–0.98

- Breast cancer RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.98.

INCRETIN-BASED THERAPIES

Incretins are hormones released from the gut in response to food ingestion, triggering release of insulin before blood glucose levels rise. Their action explains why insulin secretion increases more after an oral glucose load than after an intravenous glucose load, a phenomenon called the incretin effect.55

There are two incretin hormones: glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). They have short a half-life because they are rapidly degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV).55 Available incretin-based therapies are GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-IV inhibitors.

When used as monotherapy, incretin-based therapies do not cause hypoglycemia because their effect is glucose-dependent.55 GLP-1 receptor antagonists have the added benefit of inducing weight loss, but DPP-IV inhibitors are considered to be weight-neutral.

GLP-1 receptor agonists

Exenatide, the first of the GLP-1 receptor agonists, was approved in 2005. The original formulation (Byetta) is taken by injection twice daily, and timing in conjunction with food intake is important: it should be taken within 60 minutes before the morning and evening meals. Extended-release exenatide (Bydureon) is a once-weekly formulation taken without regard to timing of food intake. Exenatide (either twice-daily Byetta or once-weekly Bydureon) should not be used in those with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min or end-stage renal disease and should be used with caution in patients with renal transplantation.

Liraglutide (Victoza), a once-daily formulation, can be injected irrespective of food intake. The dose does not have to be adjusted for renal function, although it should be used with caution in those with renal impairment, including end-stage renal disease. Approval for a 3-mg formulation is pending with the FDA as a weight-loss drug on the basis of promising results in a randomized phase 3 trial.56

Albiglutide (Tanzeum), a once-weekly GLP-1 receptor antagonist, was recently approved by the FDA.

DPP-IV inhibitors

Whereas GLP-1 receptor agonists are injected, the DPP-IV inhibitors have the advantage of being oral agents.

Sitagliptin (Januvia), the first DPP-IV inhibitor, became available in the United States in 2006. Since then, three more have become available: saxagliptin (Onglyza), linagliptin (Tradjenta), and alogliptin (Nesina).

Concerns about thyroid cancer with incretin drugs

Concerns of increased risk of cancer, particularly of the thyroid and pancreas, have been raised since GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-IV inhibitors became available.

Studies in rodents have shown C-cell hyperplasia, sometimes resulting in increased incidence of thyroid carcinoma, and dose-dependent rises in serum calcitonin, particularly with liraglutide.26 This has raised concern about an increased risk of medullary thyroid carcinoma in humans. However, the density of C cells in rodents is up to 45 times greater than in humans, and C cells also express functional GLP-1 receptors.26

Gier et al27 assessed the expression of calcitonin and human GLP-1 receptors in normal C cells, C cell hyperplasia, and medullary cancer. In this study, calcitonin and GLP-1 receptor were co-expressed in medullary thyroid cancer (10 of 12 cases) and C-cell hyperplasia (9 of 9 cases) more commonly than in normal C cells (5 of 15 cases). Further, GLP-1 receptor was expressed in 3 of 17 cases of papillary thyroid cancer.

Calcitonin, a polypeptide hormone produced by thyroid C cells and used as a medullary thyroid cancer biomarker, was increased in a slightly higher percentage of patients treated with liraglutide than in controls, without an increase above the normal range.57

A meta-analysis by Alves et al58 of 25 studies found that neither exenatide (no cases reported) nor liraglutide (odds ratio 1.54, 95% CI 0.40–6.02) was associated with increased thyroid cancer risk.

MacConell et al59 pooled the results of 19 placebo-controlled trials of twice-daily exenatide and found a thyroid cancer incidence rate of 0.3 per 100 patient-years (< 0.1%) vs 0 per 100 patient-years in pooled comparators.

Concerns about pancreatic cancer with incretin drugs

Increased risk of acute pancreatitis is a potential side effect of both DPP-IV inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists and has led to speculation that this translates to an increased risk of pancreatic cancer.

In a point-counterpoint debate, Butler et al28 argued that incretin-based medications have questionable safety, with increased rates of pancreatitis possibly leading to pancreatic cancer. In counterpoint, Nauck60 argued that the risk of pancreatitis or cancer is extremely low, and clinical cases are unsubstantiated.

Bailey61 outlined the complexities and difficulties in drawing firm conclusions from individual clinical trials regarding possible adverse effects of diabetes drugs. The trials are typically designed to assess hemoglobin A1c reduction at varying doses and are typically restricted in patient selection, patient numbers, and drug-exposure duration, which may introduce allocation and ascertainment biases. The attempt to draw firm conclusions from such trials can be problematic and can lead to increased alarm, warranted or not.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus itself is associated with an increased incidence of pancreatic cancer, and whether incretin therapy enhances this risk is still controversial. Whether more episodes of acute pancreatitis without chronic pancreatitis can be extrapolated to an increased incidence of pancreatic cancer is doubtful. A normal pancreatic duct cell may take up to 12 years to become a tumor cell from which pancreatic carcinoma develops, another 7 years to develop metastatic capacity, and another 3 years before a diagnosis is made from clinical symptoms (which are usually accompanied by metastases).62

The risks and benefits of incretin therapies remain a contentious issue, and there are no clear prospective data at this time on increased pancreatic cancer incidence. Long-term prospective studies designed to analyze these specific outcomes (pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer, and medullary thyroid cancer) need to be undertaken.63

OTHER DIABETES THERAPIES

Alpha glucosidase inhibitors

Oral glucosidase inhibitors ameliorate hyperglycemia by inhibiting alpha glucosidase enzymes in the brush border of the small intestines, preventing conversion of polysaccharides to monosaccharides.64 This slows digestion of carbohydrates and glucose release into the bloodstream and blunts the postprandial hyperglycemic excursion.

The two alpha glucosidase inhibitors currently available in the United States are acarbose and miglitol, and although data are limited, they do not appear to increase the risk of cancer.65,66

Sodium-glucose-linked cotransporter 2 inhibitors

The newest class of oral diabetes agents to be approved are the sodium-glucose-linked cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors canagliflozin (Invokana) and dapagliflozin (Farxiga).

SGLT2 is a protein in the S1 segment of the proximal renal tubules responsible for over 90% of renal glucose reabsorption. SGLT2 inhibitors lower serum glucose levels by promoting glycosuria and have also been shown to have favorable effects on blood pressure and weight.67,68

Canagliflozin was the first of its class to gain FDA approval in the United States. It has not been found to be associated with increased cancer risk.68

Dapagliflozin, originally approved in Europe, was approved in the United States on January 8, 2014. Because of a possible increased incidence of breast and bladder malignancies, the FDA advisory committee initially recommended against approval and required further data. In those who were treated, nine cases of bladder cancer and nine cases of breast cancer were reported, compared with one case of bladder cancer and no cases of breast cancer in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significant.68

Since SGLT2 inhibitors are still new, data on long-term outcomes are lacking. Early clinical data do not show a significant increase in cancer risk.

WHAT THIS MEANS IN PRACTICE

Many studies have found associations between diabetes, obesity, hyperinsulinemia, and cancer risk. In the last decade, concerns implicating antihyperglycemic agents in cancer development have arisen but have not been well substantiated. At this time, there are no definitive prospective data indicating that the currently available type 2 diabetes therapies increase the incidence of cancer beyond the inherent increased risk in this population. What, then, is one to do?

Educate. Lifestyle modification, including weight management, should continue to be emphasized in diabetes education, as no therapy is completely effective without adjunct modifications in diet and physical activity. Epidemiologic studies have shown the benefits of lifestyle modifications, which ameliorate many of the adverse metabolic conditions that coexist in type 2 diabetes and cancer.

Screen for cancer. Given the associations between diabetes and malignancy, cancer screening is especially important in this high-risk population.

Customize therapy to individual patients. Those with a personal history of bladder cancer should avoid pioglitazone, and those who have had pancreatic cancer should avoid sitagliptin until definitive clinical data become available.

Moreover, patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer should not receive GLP-1 receptor agonists. These agents should also probably be avoided in patients with a personal history of differentiated thyroid carcinoma or a history of familial nonmedullary thyroid carcinoma. Until we have further elucidating data, it is not possible to say whether a family history of any of the other types of cancer should represent a contraindication to the use of any of these agents.

Discuss. The multitude of diabetes therapies warrants physician-patient discussions that carefully weigh the risks and benefits of additional agents to optimize glycemic control and metabolic factors in individual patients.

- Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. AACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2013. Endocr Pract 2013; 19:327–336.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Diabetes data and trends. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/statistics/. Accessed April 8, 2014.

- Vigneri P, Frasca F, Sciacca L, Pandini G, Vigneri R. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2009; 16:1103–1123.

- Huxley R, Ansary-Moghaddam A, Berrington de González A, Barzi F, Woodward M. Type-II diabetes and pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis of 36 studies. Br J Cancer 2005; 92:2076–2083.

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97:1679–1687.

- Limburg PJ, Vierkant RA, Fredericksen ZS, et al. Clinically confirmed type 2 diabetes mellitus and colorectal cancer risk: a population-based, retrospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101:1872–1879.

- El-Serag HB, Hampel H, Javadi F. The association between diabetes and hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:369–380.

- Lindblad P, Chow WH, Chan J, et al. The role of diabetes mellitus in the aetiology of renal cell cancer. Diabetologia 1999; 42:107–112.

- Washio M, Mori M, Khan M, et al; JACC Study Group. Diabetes mellitus and kidney cancer risk: the results of Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risk (JACC Study). Int J Urol 2007; 14:393–397.

- Larsson SC, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 2007; 121:856–862.

- Larsson SC, Orsini N, Brismar K, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2006; 49:2819–2823.

- Friberg E, Orsini N, Mantzoros CS, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2007; 50:1365–1374.

- Mitri J, Castillo J, Pittas AG. Diabetes and risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:2391–2397.

- Newton CC, Gapstur SM, Campbell PT, Jacobs EJ. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin-use and risk of bladder cancer in a large cohort study. Int J Cancer 2013; 132:2186–2191.

- Kasper JS, Giovannucci E. A meta-analysis of diabetes mellitus and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006; 15:2056–2062.

- Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Mondul AM, Jacobs EJ, Thun MJ, Calle EE. Diabetes and risk of prostate cancer in a prospective cohort of US men. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 161:147–152.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes public health resource. National diabetes statistics report, 2014. Estimates of diabetes and its burden in the United States. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/estimates14.htm. Accessed August 12, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer prevention and control cancer rates by race and ethnicity. www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/race.htm. Accessed August 12, 2014.

- Hemkens LG, Grouven U, Bender R, et al. Risk of malignancies in patients with diabetes treated with human insulin or insulin analogues: a cohort study. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1732–1744.

- Colhoun HMSDRN Epidemiology Group. Use of insulin glargine and cancer incidence in Scotland: a study from the Scottish Diabetes Research Network Epidemiology Group. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1755–1765.

- Currie CJ, Poole CD, Gale EA. The influence of glucose-lowering therapies on cancer risk in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009; 52:1766–1777.

- ORIGIN Trial Investigators; Gerstein HC, Bosch J, Dagenais GR, et al. Basal insulin and cardiovascular and other outcomes in dysglycemia. N Engl J Med 2012; 367:319–328.

- Baur DM, Klotsche J, Hamnvik OP, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and medications for type 2 diabetes mellitus are associated with risk for and mortality from cancer in a German primary care cohort. Metabolism 2011; 60:1363–1371.

- Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:254–258.

- Li D, Yeung SC, Hassan MM, Konopleva M, Abbruzzese JL. Antidiabetic therapies affect risk of pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:482–488.

- Bjerre Knudsen L, Madsen LW, Andersen S, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists activate rodent thyroid C-cells causing calcitonin release and C-cell proliferation. Endocrinology 2010; 151:1473–1486.

- Gier B, Butler PC, Lai CK, Kirakossian D, DeNicola MM, Yeh MW. Glucagon like peptide-1 receptor expression in the human thyroid gland. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:121–131.

- Butler PC, Elashoff M, Elashoff R, Gale EA. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: are the GLP-1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2118–2125.

- Belfiore A, Malaguarnera R. Insulin receptor and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 2011; 18:R125–R147.

- Weinstein D, Simon M, Yehezkel E, Laron Z, Werner H. Insulin analogues display IGF-I-like mitogenic and anti-apoptotic activities in cultured cancer cells. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2009; 25:41–49.

- Riddle MC. Editorial: sulfonylureas differ in effects on ischemic preconditioning—is it time to retire glyburide? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:528–530.

- Bodmer M, Becker C, Meier C, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of antidiabetic agents and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a case-control analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:620–626.

- Deutsch E, Berger M, Kussmaul WG, Hirshfeld JW, Herrmann HC, Laskey WK. Adaptation to ischemia during percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Clinical, hemodynamic, and metabolic features. Circulation 1990; 82:2044–2051.

- Feng YH, Velazquez-Torres G, Gully C, Chen J, Lee MH, Yeung SC. The impact of type 2 diabetes and antidiabetic drugs on cancer cell growth. J Cell Mol Med 2011; 15:825–836.

- Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, Leclerc J, Foretz M, Andreelli F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012; 122:253–270.

- Maida A, Lamont BJ, Cao X, Drucker DJ. Metformin regulates the incretin receptor axis via a pathway dependent on peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α in mice. Diabetologia 2011; 54:339–349.

- Gunton JE, Delhanty PJ, Takahashi S, Baxter RC. Metformin rapidly increases insulin receptor activation in human liver and signals preferentially through insulin-receptor substrate-2. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88:1323–1332.

- Ruiter R, Visser LE, van Herk-Sukel MP, et al. Lower risk of cancer in patients on metformin in comparison with those on sulfonylurea derivatives: results from a large population-based follow-up study. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:119–124.

- Libby G, Donnelly LA, Donnan PT, Alessi DR, Morris AD, Evans JM. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:1620–1625.

- Bodmer M, Becker C, Meier C, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of metformin and the risk of ovarian cancer: a case-control analysis. Gynecol Oncol 2011; 123:200–204.

- Azoulay L, Dell’Aniello S, Gagnon B, Pollak M, Suissa S. Metformin and the incidence of prostate cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2011; 20:337–344.

- Noto H, Goto A, Tsujimoto T, Noda M. Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2012; 7:e33411.

- Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL. Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care 2012; 35:299–304.

- Yki-Järvinen H. Thiazolidinediones. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:1106–1118.

- Azoulay L, Yin H, Filion KB, et al. The use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer in people with type 2 diabetes: nested case-control study. BMJ 2012; 344:e3645.

- Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care 2011; 34:916–922.

- Colmers IN, Bowker SL, Johnson JA. Thiazolidinedione use and cancer incidence in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab 2012; 38:475–484.

- Dormandy J, Bhattacharya M, van Troostenburg de Bruyn AR; PROactive investigators. Safety and tolerability of pioglitazone in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes: an overview of data from PROactive. Drug Saf 2009; 32:187–202.

- Erdmann E, Song E, Spanheimer R, van Troostenburg de Bruyn A, Perez A. Pioglitazone and bladder malignancy during observational follow-up of PROactive: 6-year update. Abstract presented at the 72nd Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association; June 8–12, 2012; Philadelphia, PA.

- Akinyeke TO, Stewart LV. Troglitazone suppresses c-Myc levels in human prostate cancer cells via a PPARγ-independent mechanism. Cancer Biol Ther 2011; 11:1046–1058.

- Ban JO, Oh JH, Son SM, et al. Troglitazone, a PPAR agonist, inhibits human prostate cancer cell growth through inactivation of NFKB via suppression of GSK-3B expression. Cancer Biol Ther 2011; 12:288–296.

- Yan KH, Yao CJ, Chang HY, Lai GM, Cheng AL, Chuang SE. The synergistic anticancer effect of troglitazone combined with aspirin causes cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Mol Carcinog 2010; 49:235–246.

- Rashid-Kolvear F, Taboski MA, Nguyen J, Wang DY, Harrington LA, Done SJ. Troglitazone suppresses telomerase activity independently of PPARgamma in estrogen-receptor negative breast cancer cells. BMC Cancer 2010; 10:390.

- Home PD, Kahn SE, Jones NP, Noronha D, Beck-Nielsen H, Viberti GADOPT Study Group; RECORD Steering Committee. Experience of malignancies with oral glucose-lowering drugs in the randomised controlled ADOPT (A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial) and RECORD (Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiovascular Outcomes and Regulation of Glycaemia in Diabetes) clinical trials. Diabetologia 2010; 53:1838–1845.

- Martin JH, Deacon CF, Gorrell MD, Prins JB. Incretin-based therapies—review of the physiology, pharmacology and emerging clinical experience. Intern Med J 2011; 41:299–307.

- Wadden TA, Hollander P, Klein S, et al; NN8022-1923 Investigators. Weight maintenance and additional weight loss with liraglutide after low-calorie-diet-induced weight loss: the SCALE Maintenance randomized study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013; 37:1443–1451.

- Hegedüs L, Moses AC, Zdravkovic M, Le Thi T, Daniels GH. GLP-1 and calcitonin concentration in humans: lack of evidence of calcitonin release from sequential screening in over 5,000 subjects with type 2 diabetes or nondiabetic obese subjects treated with the human GLP-1 analog, liraglutide. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96:853–860.

- Alves C, Batel-Marques F, Macedo AF. A meta-analysis of serious adverse events reported with exenatide and liraglutide: acute pancreatitis and cancer. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 98:271–284.

- MacConell L, Brown C, Gurney K, Han J. Safety and tolerability of exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes: integrated analysis of 5,594 patients from 19 placebo-controlled and comparator-controlled clinical trials. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2012; 5:29–41.

- Nauck MA. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin-based therapies: The benefits by far outweigh the potential risks. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2126–2132.

- Bailey CJ. Interpreting adverse signals in diabetes drug development programs. Diabetes Care 2013; 36:2098–2106.

- Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature 2010; 467:1114–1117.

- Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K, et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin-based drugs—FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:794–797.

- Bischoff H. The mechanism of alpha-glucosidase inhibition in the management of diabetes. Clin Invest Med 1995; 18:303–311.

- Monami M, Lamanna C, Balzi D, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Sulphonylureas and cancer: a case-control study. Acta Diabetol 2009; 46:279–284.

- Tseng CH. Diabetes and risk of bladder cancer: a study using the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan. Diabetologia 2011; 54:2009–2015.

- Vallon V. The proximal tubule in the pathophysiology of the diabetic kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2011; 300:R1009–R1022.

- Kim Y, Babu AR. Clinical potential of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the management of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2012; 5:313–527.

In the last quarter century, many new drugs have become available for treating type 2 diabetes mellitus. The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists incorporated these new agents in its updated glycemic control algorithm in 2013.1 Because diabetes affects 25.8 million Americans and can lead to blindness, renal failure, cardiovascular disease, and amputation, agents that help us treat it more effectively are valuable.2

One of the barriers to effective treatment is the side effects of the agents. Because some of these drugs have been in use for only a short time, concerns of potential adverse effects have arisen. Cancer is one such concern, especially since type 2 diabetes mellitus by itself increases the risk of cancer by 20% to 50% compared with no diabetes.3

Type 2 diabetes has been linked to risk of cancers of the pancreas,4 colorectum,5,6 liver,7 kidney,8,9 breast,10 bladder,11 and endometri-um,12 as well as to hematologic malignancies such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma.13 The risk of bladder cancer appears to depend on how long the patient has had type 2 diabetes. Newton et al,14 in a prospective cohort study, found that those who had diabetes for more than 15 years and used insulin had the highest risk of bladder cancer. On the other hand, the risk of prostate cancer is actually lower in people with diabetes,15 particularly in those who have had diabetes for longer than 4 years.16

Cancer and type 2 diabetes share many risk factors and underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms. Nonmodifiable risk factors for both diseases include advanced age, male sex, ethnicity (African American men appear to be most vulnerable to both cancer and diabetes),17,18 and family history. Modifiable risk factors include lower socioeconomic status, obesity, and alcohol consumption. These common risk factors lead to hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance, changes in mitochondrial function, low-grade inflammation, and oxidative stress,3 which promote both diabetes and cancer. Diabetes therapy may influence several of these processes.

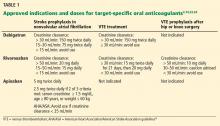

Several classes of diabetes drugs, including exogenous insulin,19–22 insulin secretagogues,23–25 and incretin-based therapies,26–28 have been under scrutiny because of their potential influences on cancer development in a population already at risk (Table 1).

INSULIN ANALOGUES: MIXED EVIDENCE

Insulin promotes cell division by binding to insulin receptor isoform A and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors.29 Because endogenous hyperinsulinemia has been linked to cancer risk, growth, and proliferation, some speculate that exogenous insulin may also increase cancer risk.

In 2009, a retrospective study by Hemkens et al linked the long-acting insulin analogue glargine to risk of cancer.19 This finding set off a tumult of controversy within the medical community and concern among patients. Several limitations of the study were brought to light, including a short duration of follow-up, and several other studies have refuted the study’s findings.20,21

More recently, the Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial22 found no higher cancer risk with glargine use than with placebo. This study enrolled 12,537 participants from 573 sites in 40 countries. Specifically, risks with glargine use were as follows:

- Any cancer—hazard ratio 1.00, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88–1.13, P = .97

- Cancer death—hazard ratio 0.94, 95% CI 0.77–1.15, P = .52.

However, the study was designed to assess cardiovascular outcomes, not cancer risk. Furthermore, the participants were not typical of patients seen in clinical practice: their insulin doses were lower (the median insulin dose was 0.4 units/kg/day by year 6, whereas in clinical practice, those with type 2 diabetes mellitus often use more than 1 unit/kg/day, depending on duration of diabetes, diet, and exercise regimen), and their baseline median hemoglobin A1c level was only 6.4%. And one may argue that the median follow-up of 6.2 years was too short for cancer to develop.22

In vitro studies indicate that long-acting analogue insulin therapy may promote cancer cell growth more than endogenous insulin,30 but epidemiologic data have not unequivocally substantiated this.20–22 There is no clear evidence that analogue insulin therapy raises cancer risk above that of human recombinant insulin, and starting insulin therapy should not be delayed because of concerns about cancer risk, particularly in uncontrolled diabetes.

INSULIN SECRETAGOGUES

Sulfonylureas: Higher risk

Before 1995, only two classes of diabetes drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)—insulin and sulfonylureas.

Sulfonylureas lower blood sugar levels by binding to sulfonylurea receptors and inhibiting adenosine triphosphate-dependent potassium channels. The resulting change in resting potential causes an influx of calcium, ultimately leading to insulin secretion.

Sulfonylureas are effective, and because of their low cost, physicians often pick them as a second-line agent after metformin.

The main disadvantage of sulfonylureas is the risk of hypoglycemia, particularly in patients with renal failure, the elderly, and diabetic patients who are unaware of when they are hypoglycemic. Other potential drawbacks are that they impair cardiac ischemic preconditioning31 and possibly increase cancer risk.21,32 (Ischemic preconditioning is the process in which transient episodes of ischemia “condition” the myocardium so that it better withstands future episodes with minimal anginal pain and tissue injury.33) Of the sulfonylureas, glyburide has been most implicated in cardiovascular risk.32

In a retrospective cohort study of 62,809 patients from a general-practice database in the United Kingdom, Currie et al21 found that sulfonylurea monotherapy was associated with a 36% higher risk of cancer (95% CI 1.19–1.54, P < .001) than metformin monotherapy. Prescribing bias may have influenced the results: practitioners are more likely to prescribe sulfonylureas to leaner patients, who have a greater likelihood of occult cancer. However, other studies also found that the cancer death rate is higher in those who take a sulfonylurea alone than in those who use metformin alone.23,24

Some evidence indicates that long-acting sulfonylurea formulations (eg, glyburide) likely hold the most danger, certainly in regard to hypoglycemia, but it is less clear if this translates to cancer concerns.31

Meglitinides: Limited evidence

Meglitinides, the other class of insulin secretagogues, are less commonly used but are similar to sulfonylureas in the way they increase endogenous insulin levels. The data are limited regarding cancer risk and meglitinide therapy, but the magnitude of the association is similar to that with sulfonylurea therapy.25

INSULIN SENSITIZERS

There are currently two classes of insulin sensitizers: biguanides and thiazolidinediones (TZDs, also known as glitazones). These drugs show less risk of both cancer incidence and cancer death than insulin secretagogues such as sulfonylureas.21,23,24 In fact, they may decrease cancer potential by alteration of signaling via the AKT/mTOR (v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway.34

Metformin, a biguanide, is the oral drug of choice

Metformin is the only biguanide currently available in the United States. It was approved by the FDA in 1995, although it had been in clinical use since the 1950s. Inexpensive and familiar, it is the oral antihyperglycemic of choice if there are no contraindications to it, such as renal dysfunction (creatinine ≥ 1.4 mg/dL in women and ≥ 1.5 mg/dL in men), acute decompensated heart failure, or pulmonary or hepatic insufficiency, all of which may lead to an increased risk of lactic acidosis.1

Metformin lowers blood sugar levels primarily by inhibiting hepatic glucose production (gluconeogenesis) and by improving peripheral insulin sensitivity. It directly activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which affects insulin signaling and glucose and fat metabolism.35 It may exert further beneficial effects by acutely increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) levels and inducing islet incretin-receptor gene expression.36 Although the exact mechanisms have not been fully elucidated, metformin’s insulin-sensitizing properties are likely from favorable effects on insulin receptor expression, tyrosine kinase activity, and influences on the incretin pathway.36,37 These effects also mitigate carcinogenesis, both directly (via AMPK and liver kinase B1, a tumor-suppressor gene) and indirectly (via reduction of hyperinsulinemia).35

Overall, biguanide therapy is associated with a lower cancer incidence or, at worst, no effect on cancer incidence. In vitro studies demonstrate that metformin both suppresses cancer cell growth and induces apoptosis, resulting in fewer live cancer cells.34 Several retrospective studies found lower cancer risk in metformin users than in patients receiving antidiabetes drugs other than insulin-sensitizing agents,21,23,25,38–40 while others have shown no effect.41 Use of metformin was specifically associated with lower risk of cancers of the liver, colon and rectum, and lung.42 Further, metformin users have a lower cancer mortality rate than nonusers.24,43

Thiazolidinediones

TZDs, such as pioglitazone, work by binding to peroxisome proliferator-activated gamma receptors in the cell nucleus, altering gene transcription.44 They reduce insulin resistance and levels of endogenous insulin levels and free fatty acids.44

Concern over bladder cancer risk with TZD use, particularly with pioglitazone, has increased in the last few years, as various cohort studies found a statistically significant increased risk with this agent.44 The risk appears to rise with cumulative dose.45,46

Randomized controlled trials also found an increased risk of bladder cancer with TZD therapy, although the difference was not statistically significant.47–49 In a mean follow-up of 8.7 years, the Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular Events reported 23 cases of bladder cancer in the pioglitazone group vs 22 cases in the placebo group, for rates of 0.9% vs 0.8% (relative risk [RR] 1.06, 95% CI 0.59–1.89).49

On the other hand, the risk of cancer of the breast, colon, and lung has been found to be lower with TZD use.47 In vitro studies support the clinical data, showing that TZDs inhibit growth of human cancer cells derived from cancers of the lung, colon, breast, stomach, ovary, and prostate.50–53

Home et al54 compared rosiglitazone against a sulfonylurea in patients already taking metformin in the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiovascular Outcomes in Oral Agent Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes (RECORD) trial. Malignancies developed in 6.7% of the sulfonylurea group compared with 5.1% of the rosiglitazone group, for a hazard ratio of 1.33 (95% CI 0.94–1.88).

Both ADOPT (A Diabetes Outcome Progression Trial) and the RECORD trial found rosiglitazone comparable to metformin in terms of cancer risk.54

Colmers et al47 pooled data from four randomized controlled trials, seven cohort studies, and nine case-control studies to assess the risk of cancer with TZD use in type 2 diabetes. Both the randomized and observational data showed neutral overall cancer risk with TZDs. However, pooled data from observational studies showed significantly lower risk with TZD use in terms of:

- Colorectal cancer RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.87–1.00

- Lung cancer RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.84–0.98

- Breast cancer RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.81–0.98.

INCRETIN-BASED THERAPIES

Incretins are hormones released from the gut in response to food ingestion, triggering release of insulin before blood glucose levels rise. Their action explains why insulin secretion increases more after an oral glucose load than after an intravenous glucose load, a phenomenon called the incretin effect.55

There are two incretin hormones: glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). They have short a half-life because they are rapidly degraded by dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV).55 Available incretin-based therapies are GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-IV inhibitors.

When used as monotherapy, incretin-based therapies do not cause hypoglycemia because their effect is glucose-dependent.55 GLP-1 receptor antagonists have the added benefit of inducing weight loss, but DPP-IV inhibitors are considered to be weight-neutral.

GLP-1 receptor agonists