User login

Study links gene dysfunction to Fanconi anemia, AML

Credit: Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they’ve discovered “an intimate link” between RUNX genes and Fanconi anemia, a finding that also has implications for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The group found that RUNX1 and RUNX3 interact with Fanconi anemia group D2 (FANCD2), a protein involved in the repair of DNA damage.

The RUNX proteins facilitate the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage in both Fanconi anemia and AML.

Motomi Osato, MD, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and his colleagues recounted these findings in Cell Reports.

The researchers began by studying RUNX deficiency in mice. They found that knockdown of both RUNX1 and RUNX3 led to bone marrow failure or myeloproliferative disorders in the mice.

These clinical manifestations are seen in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes such as Fanconi anemia, which is caused by the disruption of gene products that participate in the repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs).

With this in mind, the researchers decided to investigate RUNX function in the ICL repair pathway. And they found RUNX proteins play a critical role in the pathway by facilitating the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage.

To explore the clinical relevance of RUNX participation in DNA damage repair, the team conducted experiments in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. These AML cell lines express RUNX1-ETO, which is thought to suppress the expression and/or function of RUNX1 and RUNX3 simultaneously.

The researchers showed that Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells were sensitive to the ICL-inducing agent mytomycin C, and knocking down RUNX1-ETO reduced this sensitivity. Depleting RUNX1-ETO also led to increased FANCD2 recruitment to chromatin.

The team said these results suggest that RUNX1-ETO might repress FANCD2 foci formation and ICL repair in AML cells. And they predicted that RUNX dysfunction would sensitize the cells to PARP inhibitors.

So they tested 2 PARP inhibitors—olaparib and rucaparib—in Kasumi-1 cells and observed sensitivity to both drugs. Knocking down RUNX1-ETO partially reduced this sensitivity, while adding mytomycin C increased sensitivity.

“PARP inhibitors have been with us for quite some time, but nobody has realized their application for leukemia,” Dr Osato said. “Our study has shed light on the possibility of a more effective treatment using a combined therapy with PARP inhibitors, which can potentially be extended to other types of common cancers.”

The researchers are now conducting additional drug testing in xenograft models. ![]()

Credit: Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they’ve discovered “an intimate link” between RUNX genes and Fanconi anemia, a finding that also has implications for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The group found that RUNX1 and RUNX3 interact with Fanconi anemia group D2 (FANCD2), a protein involved in the repair of DNA damage.

The RUNX proteins facilitate the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage in both Fanconi anemia and AML.

Motomi Osato, MD, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and his colleagues recounted these findings in Cell Reports.

The researchers began by studying RUNX deficiency in mice. They found that knockdown of both RUNX1 and RUNX3 led to bone marrow failure or myeloproliferative disorders in the mice.

These clinical manifestations are seen in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes such as Fanconi anemia, which is caused by the disruption of gene products that participate in the repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs).

With this in mind, the researchers decided to investigate RUNX function in the ICL repair pathway. And they found RUNX proteins play a critical role in the pathway by facilitating the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage.

To explore the clinical relevance of RUNX participation in DNA damage repair, the team conducted experiments in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. These AML cell lines express RUNX1-ETO, which is thought to suppress the expression and/or function of RUNX1 and RUNX3 simultaneously.

The researchers showed that Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells were sensitive to the ICL-inducing agent mytomycin C, and knocking down RUNX1-ETO reduced this sensitivity. Depleting RUNX1-ETO also led to increased FANCD2 recruitment to chromatin.

The team said these results suggest that RUNX1-ETO might repress FANCD2 foci formation and ICL repair in AML cells. And they predicted that RUNX dysfunction would sensitize the cells to PARP inhibitors.

So they tested 2 PARP inhibitors—olaparib and rucaparib—in Kasumi-1 cells and observed sensitivity to both drugs. Knocking down RUNX1-ETO partially reduced this sensitivity, while adding mytomycin C increased sensitivity.

“PARP inhibitors have been with us for quite some time, but nobody has realized their application for leukemia,” Dr Osato said. “Our study has shed light on the possibility of a more effective treatment using a combined therapy with PARP inhibitors, which can potentially be extended to other types of common cancers.”

The researchers are now conducting additional drug testing in xenograft models. ![]()

Credit: Tom Ellenberger

Researchers say they’ve discovered “an intimate link” between RUNX genes and Fanconi anemia, a finding that also has implications for treating acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

The group found that RUNX1 and RUNX3 interact with Fanconi anemia group D2 (FANCD2), a protein involved in the repair of DNA damage.

The RUNX proteins facilitate the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage in both Fanconi anemia and AML.

Motomi Osato, MD, PhD, of the Cancer Science Institute of Singapore, and his colleagues recounted these findings in Cell Reports.

The researchers began by studying RUNX deficiency in mice. They found that knockdown of both RUNX1 and RUNX3 led to bone marrow failure or myeloproliferative disorders in the mice.

These clinical manifestations are seen in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes such as Fanconi anemia, which is caused by the disruption of gene products that participate in the repair of DNA interstrand crosslinks (ICLs).

With this in mind, the researchers decided to investigate RUNX function in the ICL repair pathway. And they found RUNX proteins play a critical role in the pathway by facilitating the recruitment of FANCD2 to sites of DNA damage.

To explore the clinical relevance of RUNX participation in DNA damage repair, the team conducted experiments in Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells. These AML cell lines express RUNX1-ETO, which is thought to suppress the expression and/or function of RUNX1 and RUNX3 simultaneously.

The researchers showed that Kasumi-1 and SKNO-1 cells were sensitive to the ICL-inducing agent mytomycin C, and knocking down RUNX1-ETO reduced this sensitivity. Depleting RUNX1-ETO also led to increased FANCD2 recruitment to chromatin.

The team said these results suggest that RUNX1-ETO might repress FANCD2 foci formation and ICL repair in AML cells. And they predicted that RUNX dysfunction would sensitize the cells to PARP inhibitors.

So they tested 2 PARP inhibitors—olaparib and rucaparib—in Kasumi-1 cells and observed sensitivity to both drugs. Knocking down RUNX1-ETO partially reduced this sensitivity, while adding mytomycin C increased sensitivity.

“PARP inhibitors have been with us for quite some time, but nobody has realized their application for leukemia,” Dr Osato said. “Our study has shed light on the possibility of a more effective treatment using a combined therapy with PARP inhibitors, which can potentially be extended to other types of common cancers.”

The researchers are now conducting additional drug testing in xenograft models. ![]()

Chemo and CAR T cells prompt responses in NHL

An infusion of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy following chemotherapy can elicit responses in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a small study suggests.

However, patients also experienced significant acute toxicities, including fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium.

James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, but the CAR T-cell therapy being tested uses the same CAR construct as KTE-C19, which is being developed by Kite Pharma, Inc.

The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies. The patients first received conditioning with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine.

A day later, they received a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy, which consists of T cells taken from each patient’s peripheral blood and modified to target CD19.

The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Response rates

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. One patient was lost to follow-up because of noncompliance, and 1 died soon after treatment. The researchers said the cause of death was likely cardiac arrhythmia.

The overall response rate was 92%. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Three of the CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 9 months to 22 months.

Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. All 3 CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 14 months to 23 months.

Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR. The duration of the ongoing CR is 11 months.

Toxicity

As seen in other studies, the CAR T-cell therapy was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or IL-6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

One of these patients developed aphasia on day 5 after CAR T-cell infusion. It occurred intermittently for 7 days before resolving. The patient also experienced right-sided facial paresis that lasted approximately 20 minutes on day 8 after infusion.

Another patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion, but this was followed by confusion and severe generalized myoclonus. All symptoms resolved by 11 days after the infusion, except for a mild tremor that resolved over the next month.

A third patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion. This was followed by confusion, hemifacial spasms, apraxia, and gait disturbances. These effects varied in severity but dramatically improved 20 days after the infusion, according to the researchers. ![]()

An infusion of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy following chemotherapy can elicit responses in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a small study suggests.

However, patients also experienced significant acute toxicities, including fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium.

James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, but the CAR T-cell therapy being tested uses the same CAR construct as KTE-C19, which is being developed by Kite Pharma, Inc.

The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies. The patients first received conditioning with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine.

A day later, they received a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy, which consists of T cells taken from each patient’s peripheral blood and modified to target CD19.

The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Response rates

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. One patient was lost to follow-up because of noncompliance, and 1 died soon after treatment. The researchers said the cause of death was likely cardiac arrhythmia.

The overall response rate was 92%. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Three of the CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 9 months to 22 months.

Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. All 3 CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 14 months to 23 months.

Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR. The duration of the ongoing CR is 11 months.

Toxicity

As seen in other studies, the CAR T-cell therapy was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or IL-6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

One of these patients developed aphasia on day 5 after CAR T-cell infusion. It occurred intermittently for 7 days before resolving. The patient also experienced right-sided facial paresis that lasted approximately 20 minutes on day 8 after infusion.

Another patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion, but this was followed by confusion and severe generalized myoclonus. All symptoms resolved by 11 days after the infusion, except for a mild tremor that resolved over the next month.

A third patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion. This was followed by confusion, hemifacial spasms, apraxia, and gait disturbances. These effects varied in severity but dramatically improved 20 days after the infusion, according to the researchers. ![]()

An infusion of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy following chemotherapy can elicit responses in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a small study suggests.

However, patients also experienced significant acute toxicities, including fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium.

James N. Kochenderfer, MD, of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, and his colleagues reported these results in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

The trial was sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, but the CAR T-cell therapy being tested uses the same CAR construct as KTE-C19, which is being developed by Kite Pharma, Inc.

The study included 15 patients with advanced B-cell malignancies. The patients first received conditioning with cyclophosphamide and fludarabine.

A day later, they received a single infusion of the CAR T-cell therapy, which consists of T cells taken from each patient’s peripheral blood and modified to target CD19.

The researchers noted that the conditioning regimen is known to be active against B-cell malignancies and could have made a direct contribution to patient responses.

Response rates

Thirteen patients were evaluable for response. One patient was lost to follow-up because of noncompliance, and 1 died soon after treatment. The researchers said the cause of death was likely cardiac arrhythmia.

The overall response rate was 92%. Eight patients achieved a complete response (CR), and 4 had a partial response (PR).

Of the 7 patients with chemotherapy-refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, 4 achieved a CR, 2 achieved a PR, and 1 had stable disease. Three of the CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 9 months to 22 months.

Of the 4 patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, 3 had a CR, and 1 had a PR. All 3 CRs are ongoing, with the duration ranging from 14 months to 23 months.

Among the 2 patients with indolent lymphomas, 1 achieved a CR, and 1 had a PR. The duration of the ongoing CR is 11 months.

Toxicity

As seen in other studies, the CAR T-cell therapy was associated with fever, low blood pressure, focal neurological deficits, and delirium. Toxicities largely occurred in the first 2 weeks after infusion.

All but 2 patients experienced grade 3/4 adverse events. Four patients had grade 3/4 hypotension.

All patients had elevations in serum interferon gamma and/or IL-6 around the time of peak toxicity, but most did not develop elevations in serum tumor necrosis factor.

Neurologic toxicities included confusion and obtundation, which have been reported in previous studies. However, 3 patients developed unexpected neurologic abnormalities.

One of these patients developed aphasia on day 5 after CAR T-cell infusion. It occurred intermittently for 7 days before resolving. The patient also experienced right-sided facial paresis that lasted approximately 20 minutes on day 8 after infusion.

Another patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion, but this was followed by confusion and severe generalized myoclonus. All symptoms resolved by 11 days after the infusion, except for a mild tremor that resolved over the next month.

A third patient developed aphasia 5 days after CAR T-cell infusion. This was followed by confusion, hemifacial spasms, apraxia, and gait disturbances. These effects varied in severity but dramatically improved 20 days after the infusion, according to the researchers. ![]()

Tool mines scientific literature, generates hypotheses

Credit: NIH

A new tool may help researchers sift through the scientific literature to discover hypothesis-generating information relevant to their own research.

The resource, called the Knowledge Integration Toolkit (KnIT), extracts relevant information from the literature, includes it in a network that can be queried, and

then attempts to use these data to generate reasonable and testable hypotheses that can help direct lab studies.

Researchers tested KnIT in a retrospective case study involving published data on p53 and found the tool could accurately predict the existence of proteins that modify p53.

Details from this study were published in the Association for Computing Machinery’s digital library.

Olivier Lichtarge, MD, PhD, of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, is scheduled to discuss the study on August 27 at the 20th Annual Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining Conference in New York, New York.

“On average, a scientist might read between 1 and 5 research papers on a good day,” Dr Lichtarge noted.

“But, to put this in perspective with p53, there are over 70,000 papers published on this protein. Even if a scientist reads 5 papers a day, it could take nearly 38 years to completely understand all of the research already available today on this protein.”

Scientists formulate hypotheses based on what they read and know, but because they cannot read everything, their hypotheses may be biased, according to Dr Lichtarge.

“A computer certainly may not reason as well as a scientist,” he said, “but the little it can, logically and objectively, may contribute greatly when applied to our entire body of knowledge.”

With that in mind, Dr Lichtarge and his colleagues initiated a project to develop a knowledge integration tool that took advantage of existing text mining capabilities, such as those used by IBM’s Watson technology—cognitive technology that processes information more like a human than a computer.

And the team came up with KnIT. In the first test using KnIT, they sought to identify new protein kinases that phosphorylate p53.

There are more than 500 known human kinases and tens of thousands of possible proteins they can target. Thirty-three are currently known to modify p53.

The researchers used KnIT to mine the scientific literature up to 2003, when only half of the 33 phosphorylating protein kinases had been discovered.

Seventy-four kinases were extracted as potential modifiers. Of these, prior to 2003, 10 were known to phosphorylate p53, and 9 were discovered at a later date.

Of the 10 already known, KnIT accounted for them in reasoning as well as ranking the likelihood that the other 64 kinases targeted p53. Of the 9 found nearly a decade later, KnIT accurately predicted 7.

“This study showed that, in a very narrow field of study regarding p53, we can, in fact, suggest new relationships and new functions associated with p53, which can later be directly validated in the laboratory,” Dr Lichtarge said.

“Our long-term hope is to systematically extract knowledge directly from the totality of the public medical literature. For this, we need technological advances to read text, extract facts from every sentence, and to integrate this information into a network that describes the relationship between all of the objects and entities discussed in the literature.”

“This first study is promising, because it suggests a proof of principle for a small step towards this type of knowledge discovery. With more research, we hope to get closer to clinical and therapeutic applications.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

A new tool may help researchers sift through the scientific literature to discover hypothesis-generating information relevant to their own research.

The resource, called the Knowledge Integration Toolkit (KnIT), extracts relevant information from the literature, includes it in a network that can be queried, and

then attempts to use these data to generate reasonable and testable hypotheses that can help direct lab studies.

Researchers tested KnIT in a retrospective case study involving published data on p53 and found the tool could accurately predict the existence of proteins that modify p53.

Details from this study were published in the Association for Computing Machinery’s digital library.

Olivier Lichtarge, MD, PhD, of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, is scheduled to discuss the study on August 27 at the 20th Annual Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining Conference in New York, New York.

“On average, a scientist might read between 1 and 5 research papers on a good day,” Dr Lichtarge noted.

“But, to put this in perspective with p53, there are over 70,000 papers published on this protein. Even if a scientist reads 5 papers a day, it could take nearly 38 years to completely understand all of the research already available today on this protein.”

Scientists formulate hypotheses based on what they read and know, but because they cannot read everything, their hypotheses may be biased, according to Dr Lichtarge.

“A computer certainly may not reason as well as a scientist,” he said, “but the little it can, logically and objectively, may contribute greatly when applied to our entire body of knowledge.”

With that in mind, Dr Lichtarge and his colleagues initiated a project to develop a knowledge integration tool that took advantage of existing text mining capabilities, such as those used by IBM’s Watson technology—cognitive technology that processes information more like a human than a computer.

And the team came up with KnIT. In the first test using KnIT, they sought to identify new protein kinases that phosphorylate p53.

There are more than 500 known human kinases and tens of thousands of possible proteins they can target. Thirty-three are currently known to modify p53.

The researchers used KnIT to mine the scientific literature up to 2003, when only half of the 33 phosphorylating protein kinases had been discovered.

Seventy-four kinases were extracted as potential modifiers. Of these, prior to 2003, 10 were known to phosphorylate p53, and 9 were discovered at a later date.

Of the 10 already known, KnIT accounted for them in reasoning as well as ranking the likelihood that the other 64 kinases targeted p53. Of the 9 found nearly a decade later, KnIT accurately predicted 7.

“This study showed that, in a very narrow field of study regarding p53, we can, in fact, suggest new relationships and new functions associated with p53, which can later be directly validated in the laboratory,” Dr Lichtarge said.

“Our long-term hope is to systematically extract knowledge directly from the totality of the public medical literature. For this, we need technological advances to read text, extract facts from every sentence, and to integrate this information into a network that describes the relationship between all of the objects and entities discussed in the literature.”

“This first study is promising, because it suggests a proof of principle for a small step towards this type of knowledge discovery. With more research, we hope to get closer to clinical and therapeutic applications.” ![]()

Credit: NIH

A new tool may help researchers sift through the scientific literature to discover hypothesis-generating information relevant to their own research.

The resource, called the Knowledge Integration Toolkit (KnIT), extracts relevant information from the literature, includes it in a network that can be queried, and

then attempts to use these data to generate reasonable and testable hypotheses that can help direct lab studies.

Researchers tested KnIT in a retrospective case study involving published data on p53 and found the tool could accurately predict the existence of proteins that modify p53.

Details from this study were published in the Association for Computing Machinery’s digital library.

Olivier Lichtarge, MD, PhD, of the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, is scheduled to discuss the study on August 27 at the 20th Annual Association for Computing Machinery’s Special Interest Group on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining Conference in New York, New York.

“On average, a scientist might read between 1 and 5 research papers on a good day,” Dr Lichtarge noted.

“But, to put this in perspective with p53, there are over 70,000 papers published on this protein. Even if a scientist reads 5 papers a day, it could take nearly 38 years to completely understand all of the research already available today on this protein.”

Scientists formulate hypotheses based on what they read and know, but because they cannot read everything, their hypotheses may be biased, according to Dr Lichtarge.

“A computer certainly may not reason as well as a scientist,” he said, “but the little it can, logically and objectively, may contribute greatly when applied to our entire body of knowledge.”

With that in mind, Dr Lichtarge and his colleagues initiated a project to develop a knowledge integration tool that took advantage of existing text mining capabilities, such as those used by IBM’s Watson technology—cognitive technology that processes information more like a human than a computer.

And the team came up with KnIT. In the first test using KnIT, they sought to identify new protein kinases that phosphorylate p53.

There are more than 500 known human kinases and tens of thousands of possible proteins they can target. Thirty-three are currently known to modify p53.

The researchers used KnIT to mine the scientific literature up to 2003, when only half of the 33 phosphorylating protein kinases had been discovered.

Seventy-four kinases were extracted as potential modifiers. Of these, prior to 2003, 10 were known to phosphorylate p53, and 9 were discovered at a later date.

Of the 10 already known, KnIT accounted for them in reasoning as well as ranking the likelihood that the other 64 kinases targeted p53. Of the 9 found nearly a decade later, KnIT accurately predicted 7.

“This study showed that, in a very narrow field of study regarding p53, we can, in fact, suggest new relationships and new functions associated with p53, which can later be directly validated in the laboratory,” Dr Lichtarge said.

“Our long-term hope is to systematically extract knowledge directly from the totality of the public medical literature. For this, we need technological advances to read text, extract facts from every sentence, and to integrate this information into a network that describes the relationship between all of the objects and entities discussed in the literature.”

“This first study is promising, because it suggests a proof of principle for a small step towards this type of knowledge discovery. With more research, we hope to get closer to clinical and therapeutic applications.” ![]()

USPSTF: Offer behavioral counseling to prevent cardiovascular disease

Overweight or obese adults at risk for cardiovascular disease should receive intensive behavioral counseling interventions, according to a recommendation statement by the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force.

After a comprehensive review of the current literature, the USPSTF concluded "with moderate certainty" that interventions promoting a healthful diet and increased physical activity have a moderate net benefit in this patient population, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force at the time the recommendation was finalized, and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

The recommendation statement issued Aug. 25 is "an update and refinement" of the 2003 USPSTF recommendation on dietary counseling for at-risk adults, this time targeting overweight or obese patients who have additional CVD risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose, or metabolic syndrome.

The group reviewed 74 trials assessing the effectiveness of behavioral counseling interventions of various intensities. Only 16 reported on direct health outcomes such as CVD events, mortality, or quality of life, the task force noted, so there is inadequate evidence about intensive behavioral counseling’s effect on such outcomes.

A total of 71 trials involving more than 32,000 participants focused on intermediate health outcomes such as lipid levels, blood pressure, glucose levels, weight, and medication use. Overall, intensive counseling interventions made "small but important changes" in these outcomes, with total cholesterol levels decreasing approximately 3-6 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol decreasing by 1.5-5.0 mg/dL, systolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-3 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-2 mm Hg, and fasting glucose levels decreasing by 1-3 mg/dL.

In addition, weight decreased by a mean of approximately 3 kg, and the proportion of patients who participated in moderate-intensity exercise for 150 minutes per week rose from 10% to 25%. However, few of these studies followed patients for more than 1-2 years, so the evidence was inadequate to assess longer-term benefits.

Because very few and mostly minor adverse events were associated with these interventions, they yielded a moderate net benefit.

Most of the intensive behavioral counseling interventions that were assessed averaged 5-16 individual or group sessions during a period of 9-12 months. All included didactic education; in most programs, specially trained professionals (dietitians, nutritionists, physiotherapists, exercise professionals, health educators, and psychologists) provided monitoring and feedback for the participants, devised individualized care plans, and taught problem-solving skills. Many types and combinations of interventions were effective, and almost all were delivered outside the primary care setting.

The recommendation statement is in line with others published by the American Heart Association, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The AAFP is updating its recommendations regarding behavioral counseling to prevent CVD, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF, funded by but independent of the federal government, makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive-care services based on evidence of benefits and harms, without considering costs.

Do you refer overweight or obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors for intensive behavioral counseling? Take our Quick Poll on the Family Practice News homepage.

Overweight or obese adults at risk for cardiovascular disease should receive intensive behavioral counseling interventions, according to a recommendation statement by the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force.

After a comprehensive review of the current literature, the USPSTF concluded "with moderate certainty" that interventions promoting a healthful diet and increased physical activity have a moderate net benefit in this patient population, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force at the time the recommendation was finalized, and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

The recommendation statement issued Aug. 25 is "an update and refinement" of the 2003 USPSTF recommendation on dietary counseling for at-risk adults, this time targeting overweight or obese patients who have additional CVD risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose, or metabolic syndrome.

The group reviewed 74 trials assessing the effectiveness of behavioral counseling interventions of various intensities. Only 16 reported on direct health outcomes such as CVD events, mortality, or quality of life, the task force noted, so there is inadequate evidence about intensive behavioral counseling’s effect on such outcomes.

A total of 71 trials involving more than 32,000 participants focused on intermediate health outcomes such as lipid levels, blood pressure, glucose levels, weight, and medication use. Overall, intensive counseling interventions made "small but important changes" in these outcomes, with total cholesterol levels decreasing approximately 3-6 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol decreasing by 1.5-5.0 mg/dL, systolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-3 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-2 mm Hg, and fasting glucose levels decreasing by 1-3 mg/dL.

In addition, weight decreased by a mean of approximately 3 kg, and the proportion of patients who participated in moderate-intensity exercise for 150 minutes per week rose from 10% to 25%. However, few of these studies followed patients for more than 1-2 years, so the evidence was inadequate to assess longer-term benefits.

Because very few and mostly minor adverse events were associated with these interventions, they yielded a moderate net benefit.

Most of the intensive behavioral counseling interventions that were assessed averaged 5-16 individual or group sessions during a period of 9-12 months. All included didactic education; in most programs, specially trained professionals (dietitians, nutritionists, physiotherapists, exercise professionals, health educators, and psychologists) provided monitoring and feedback for the participants, devised individualized care plans, and taught problem-solving skills. Many types and combinations of interventions were effective, and almost all were delivered outside the primary care setting.

The recommendation statement is in line with others published by the American Heart Association, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The AAFP is updating its recommendations regarding behavioral counseling to prevent CVD, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF, funded by but independent of the federal government, makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive-care services based on evidence of benefits and harms, without considering costs.

Do you refer overweight or obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors for intensive behavioral counseling? Take our Quick Poll on the Family Practice News homepage.

Overweight or obese adults at risk for cardiovascular disease should receive intensive behavioral counseling interventions, according to a recommendation statement by the U. S. Preventive Services Task Force.

After a comprehensive review of the current literature, the USPSTF concluded "with moderate certainty" that interventions promoting a healthful diet and increased physical activity have a moderate net benefit in this patient population, said Dr. Michael L. LeFevre, chair of the task force at the time the recommendation was finalized, and professor of family medicine at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

The recommendation statement issued Aug. 25 is "an update and refinement" of the 2003 USPSTF recommendation on dietary counseling for at-risk adults, this time targeting overweight or obese patients who have additional CVD risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose, or metabolic syndrome.

The group reviewed 74 trials assessing the effectiveness of behavioral counseling interventions of various intensities. Only 16 reported on direct health outcomes such as CVD events, mortality, or quality of life, the task force noted, so there is inadequate evidence about intensive behavioral counseling’s effect on such outcomes.

A total of 71 trials involving more than 32,000 participants focused on intermediate health outcomes such as lipid levels, blood pressure, glucose levels, weight, and medication use. Overall, intensive counseling interventions made "small but important changes" in these outcomes, with total cholesterol levels decreasing approximately 3-6 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol decreasing by 1.5-5.0 mg/dL, systolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-3 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-2 mm Hg, and fasting glucose levels decreasing by 1-3 mg/dL.

In addition, weight decreased by a mean of approximately 3 kg, and the proportion of patients who participated in moderate-intensity exercise for 150 minutes per week rose from 10% to 25%. However, few of these studies followed patients for more than 1-2 years, so the evidence was inadequate to assess longer-term benefits.

Because very few and mostly minor adverse events were associated with these interventions, they yielded a moderate net benefit.

Most of the intensive behavioral counseling interventions that were assessed averaged 5-16 individual or group sessions during a period of 9-12 months. All included didactic education; in most programs, specially trained professionals (dietitians, nutritionists, physiotherapists, exercise professionals, health educators, and psychologists) provided monitoring and feedback for the participants, devised individualized care plans, and taught problem-solving skills. Many types and combinations of interventions were effective, and almost all were delivered outside the primary care setting.

The recommendation statement is in line with others published by the American Heart Association, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the American Academy of Family Physicians. The AAFP is updating its recommendations regarding behavioral counseling to prevent CVD, Dr. LeFevre and his associates noted.

The USPSTF, funded by but independent of the federal government, makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive-care services based on evidence of benefits and harms, without considering costs.

Do you refer overweight or obese patients with cardiovascular risk factors for intensive behavioral counseling? Take our Quick Poll on the Family Practice News homepage.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Refer overweight or obese patients at risk of cardiovascular disease for intensive behavioral counseling.

Major Finding: Intensive behavioral counseling interventions made small but important changes in several intermediate health outcomes, with total cholesterol levels decreasing by about 3-6 mg/dL, LDL cholesterol decreasing by 1.5-5.0 mg/dL, systolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-3 mm Hg, diastolic blood pressure decreasing by 1-2 mm Hg, fasting glucose levels decreasing by 1-3 mg/dL, and weight decreasing by a mean of 3 kg.

Data Source: An update and refinement of a 2003 USPSTF recommendation on dietary counseling for overweight/obese adults who have additional risk factors for CVD, based on a comprehensive review of the literature.

Disclosures: The USPSTF, funded by but independent of the federal government, makes recommendations about the effectiveness of specific preventive-care services based on evidence of benefits and harms, without considering costs.

AHA wants e-cigarettes regulated but notes they help some smokers quit

The American Heart Association has released its recommendations regarding the sale and usage of e-cigarettes, cautioning that the devices should be regulated to avoid enticing children to smoke while also saying that e-cigarettes could be used as a way to help some current smokers quit.

The guidelines, published online Aug. 24 in Circulation, state that clinicians "should not discourage" their patients from resorting to e-cigarettes if other approved forms of smoking cessation, such as the nicotine patch, have been exhausted. The AHA warned, however, that further studies are needed to fully understand the effects of e-cigarette usage, stressing that e-cigarettes have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as an acceptable smoking cessation device and could contain low amounts of toxic chemicals that would prove more harmful than helpful to patients in the long run.

"E-cigarettes have caused a major shift in the tobacco-control landscape," Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., lead author of the guidelines and chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Louisville, Ky., said in a statement. "It’s critical that we rigorously examine the long-term impact of this new technology on public health, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, and pay careful attention to the effect of e-cigarettes on adolescents."

For now, the AHA says that clinicians should tell their patients who use e-cigarettes to set a firm quit date, warning that any device that delivers nicotine into the body is harmful and likely lethal.

"Nicotine is a dangerous and highly addictive chemical no matter what form it takes – conventional cigarettes or some other tobacco product," Dr. Elliott Antman, AHA president, said in the statement. "Every life that has been lost to tobacco addiction" could have been saved, he noted.

To that end, the AHA also called for strong regulations regarding the potential marketability of e-cigarettes to youngsters. The group recommended a federal ban on the sale of e-cigarettes to minors, warning that the devices could become a gateway to actual cigarettes for young people who see e-cigarettes as "high-tech, accessible, and convenient," according to a JAMA Pediatrics study of 40,000 middle and high school students. The AHA also recommended that all existing rules and regulations in place for tobacco-related products should apply to e-cigarettes.

"We must protect future generations from any potential smokescreens in the tobacco product landscape that will cause us to lose precious ground in the fight to make our nation 100% tobacco-free," Dr. Antman said.

According to the AHA, 20 million Americans have lost their lives to tobacco over the last 50 years.

The American Heart Association has released its recommendations regarding the sale and usage of e-cigarettes, cautioning that the devices should be regulated to avoid enticing children to smoke while also saying that e-cigarettes could be used as a way to help some current smokers quit.

The guidelines, published online Aug. 24 in Circulation, state that clinicians "should not discourage" their patients from resorting to e-cigarettes if other approved forms of smoking cessation, such as the nicotine patch, have been exhausted. The AHA warned, however, that further studies are needed to fully understand the effects of e-cigarette usage, stressing that e-cigarettes have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as an acceptable smoking cessation device and could contain low amounts of toxic chemicals that would prove more harmful than helpful to patients in the long run.

"E-cigarettes have caused a major shift in the tobacco-control landscape," Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., lead author of the guidelines and chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Louisville, Ky., said in a statement. "It’s critical that we rigorously examine the long-term impact of this new technology on public health, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, and pay careful attention to the effect of e-cigarettes on adolescents."

For now, the AHA says that clinicians should tell their patients who use e-cigarettes to set a firm quit date, warning that any device that delivers nicotine into the body is harmful and likely lethal.

"Nicotine is a dangerous and highly addictive chemical no matter what form it takes – conventional cigarettes or some other tobacco product," Dr. Elliott Antman, AHA president, said in the statement. "Every life that has been lost to tobacco addiction" could have been saved, he noted.

To that end, the AHA also called for strong regulations regarding the potential marketability of e-cigarettes to youngsters. The group recommended a federal ban on the sale of e-cigarettes to minors, warning that the devices could become a gateway to actual cigarettes for young people who see e-cigarettes as "high-tech, accessible, and convenient," according to a JAMA Pediatrics study of 40,000 middle and high school students. The AHA also recommended that all existing rules and regulations in place for tobacco-related products should apply to e-cigarettes.

"We must protect future generations from any potential smokescreens in the tobacco product landscape that will cause us to lose precious ground in the fight to make our nation 100% tobacco-free," Dr. Antman said.

According to the AHA, 20 million Americans have lost their lives to tobacco over the last 50 years.

The American Heart Association has released its recommendations regarding the sale and usage of e-cigarettes, cautioning that the devices should be regulated to avoid enticing children to smoke while also saying that e-cigarettes could be used as a way to help some current smokers quit.

The guidelines, published online Aug. 24 in Circulation, state that clinicians "should not discourage" their patients from resorting to e-cigarettes if other approved forms of smoking cessation, such as the nicotine patch, have been exhausted. The AHA warned, however, that further studies are needed to fully understand the effects of e-cigarette usage, stressing that e-cigarettes have not been approved by the Food and Drug Administration as an acceptable smoking cessation device and could contain low amounts of toxic chemicals that would prove more harmful than helpful to patients in the long run.

"E-cigarettes have caused a major shift in the tobacco-control landscape," Aruni Bhatnagar, Ph.D., lead author of the guidelines and chair of cardiovascular medicine at the University of Louisville, Ky., said in a statement. "It’s critical that we rigorously examine the long-term impact of this new technology on public health, cardiovascular disease, and stroke, and pay careful attention to the effect of e-cigarettes on adolescents."

For now, the AHA says that clinicians should tell their patients who use e-cigarettes to set a firm quit date, warning that any device that delivers nicotine into the body is harmful and likely lethal.

"Nicotine is a dangerous and highly addictive chemical no matter what form it takes – conventional cigarettes or some other tobacco product," Dr. Elliott Antman, AHA president, said in the statement. "Every life that has been lost to tobacco addiction" could have been saved, he noted.

To that end, the AHA also called for strong regulations regarding the potential marketability of e-cigarettes to youngsters. The group recommended a federal ban on the sale of e-cigarettes to minors, warning that the devices could become a gateway to actual cigarettes for young people who see e-cigarettes as "high-tech, accessible, and convenient," according to a JAMA Pediatrics study of 40,000 middle and high school students. The AHA also recommended that all existing rules and regulations in place for tobacco-related products should apply to e-cigarettes.

"We must protect future generations from any potential smokescreens in the tobacco product landscape that will cause us to lose precious ground in the fight to make our nation 100% tobacco-free," Dr. Antman said.

According to the AHA, 20 million Americans have lost their lives to tobacco over the last 50 years.

FROM CIRCULATION

Gestational diabetes and the Barker Hypothesis

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

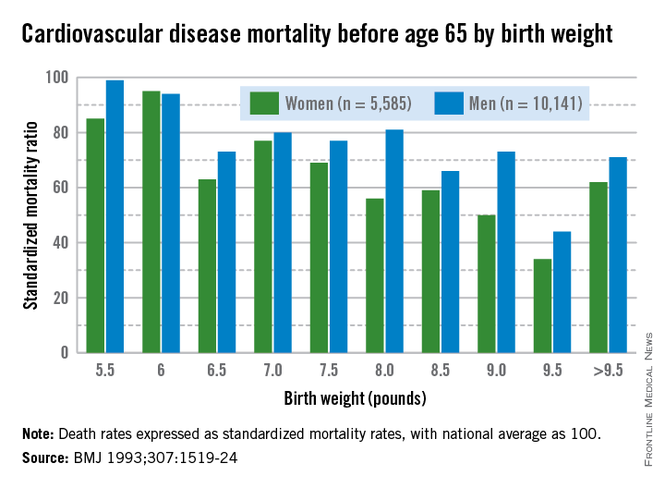

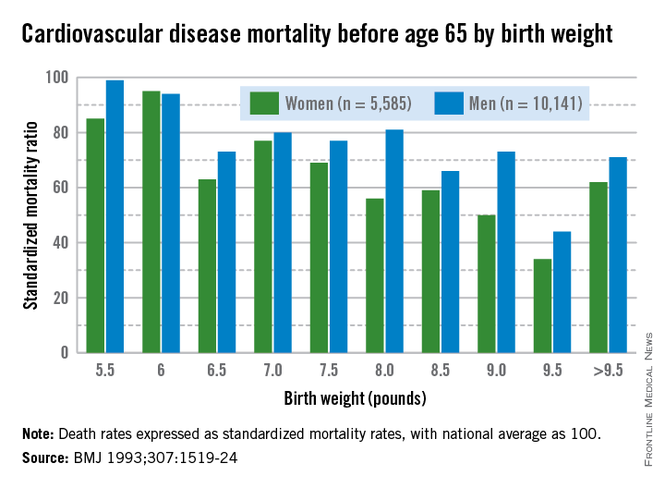

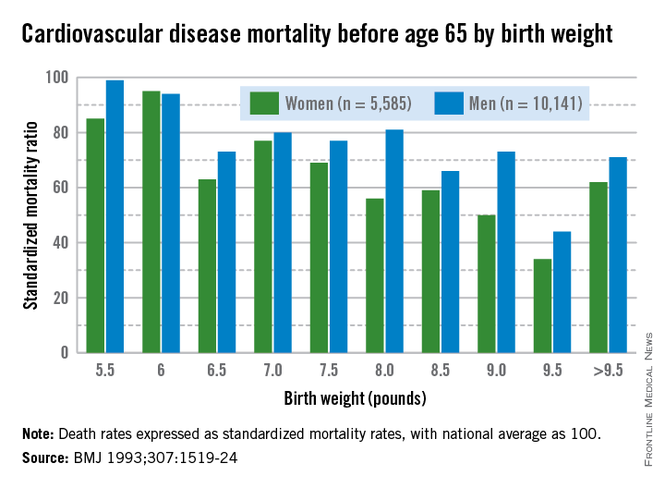

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

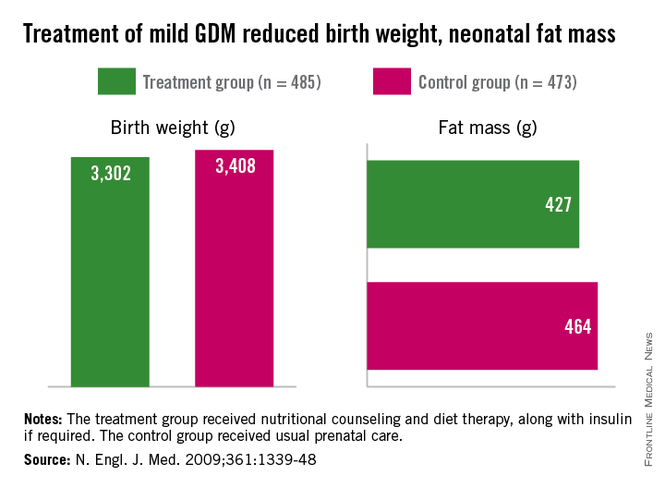

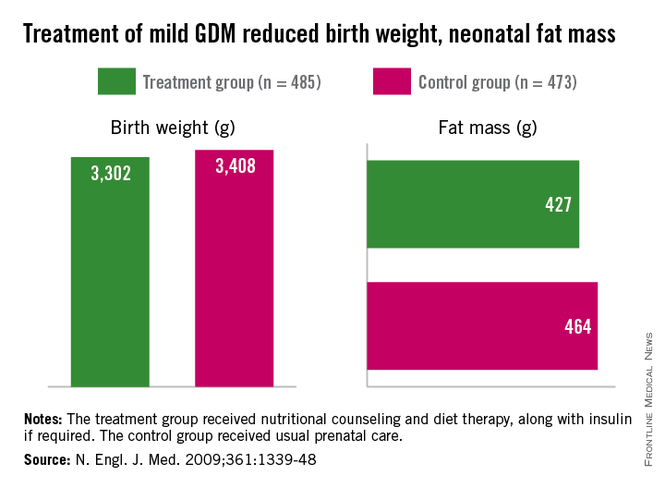

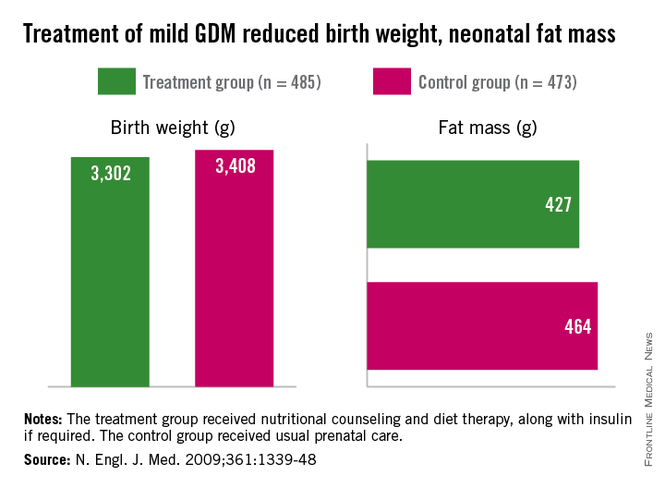

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

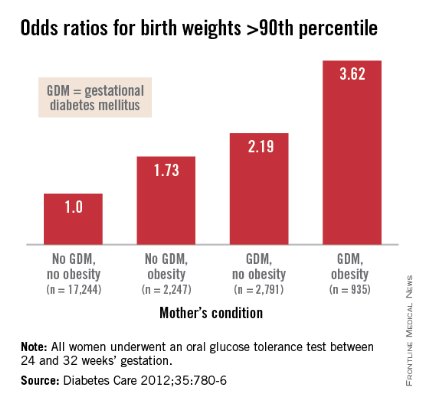

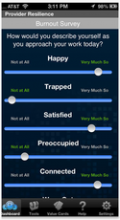

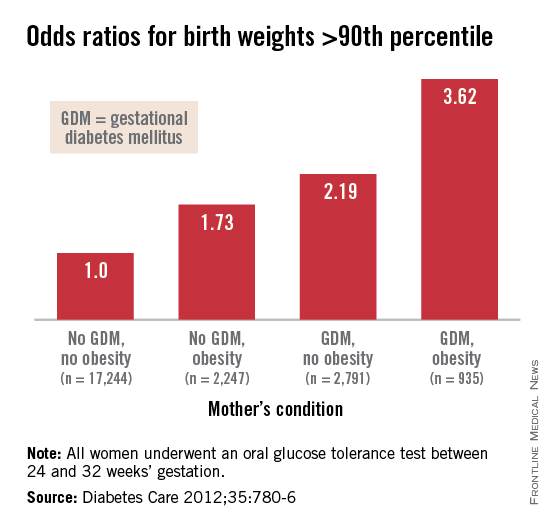

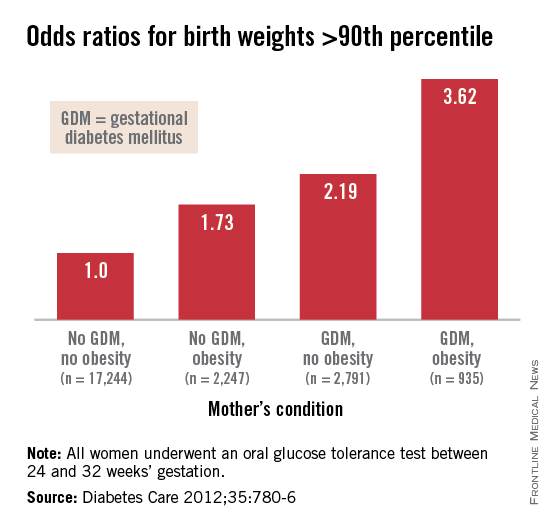

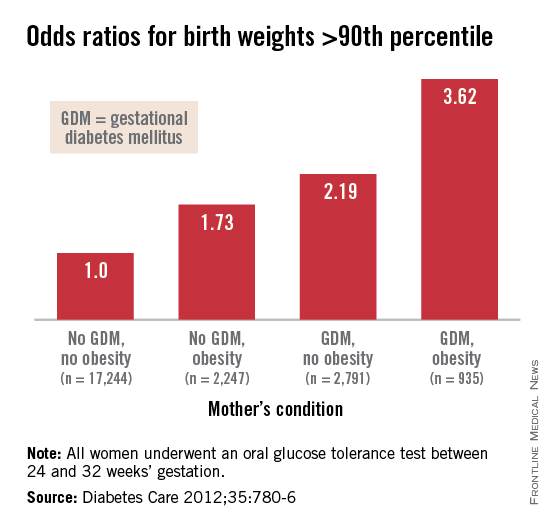

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

Although there are some glimmers of hope that U.S. birthweights may be declining, the average infant birthweight has remained significantly tilted toward obesity. Moreover, and alarming number of infants, children, and adolescents are obese.

In 2007-2008, 9.5% of infants and toddlers were at or above the 95th percentile of the weight-for-recumbent-length growth charts. Among children and adolescents aged 2-19 years, 11.9% were at or above the 97th percentile of the body-mass-index-for-age growth charts; 16.9% were at or above the 95th percentile; and 31.7% were at or above the 85th percentile of BMI for age (JAMA 2010;303:242-9).

While more recent reports of obesity in children indicate a modest decline in obesity among 2- to 5-year-olds (JAMA 2014;311:806-14), an alarming number of infants and children have excess adiposity (roughly twice what is expected). In addition, cardiovascular mortality later in life continues to rise.

The question arises, have childhood and adult obesity rates remained high because mothers are feeding their children the wrong foods or because these children were born obese? One also wonders, with respect to cardiovascular mortality in adulthood, is the in utero environment playing a role?

Old lessons, growing relevance

More than 3 decades ago, the late British physician Dr. David Barker got us thinking about how a challenging life in the womb can set us up for downstream ill health. He studied births from 1910 to 1945 and found that the cardiovascular mortality of individuals born during that time was inversely related to birthweight. Smaller babies, he found, could have cardiovascular mortality risks that were double or even quadruple the risks of larger babies.

Dr. Barker theorized that, when faced with undernutrition, the fetus adapts by sending more blood to the brain and sacrificing blood flow to less essential tissues. His theory about how growth and nutrition before birth may affect the heart became known as the "Barker Hypothesis." It was initially controversial, but it led to an explosion of research – especially since 2000 – on various downstream effects of the intrauterine environment.

Investigators have learned that it is not only cardiovascular mortality that is affected by low birthweight, but also the risk of developing diabetes and being overweight. This is because the fetus makes less essential systems insulin resistant. Insulin resistance persists in the womb and after birth as well, predisposing individuals to insulin resistance and obesity, both of which are closely linked to the risk of metabolic syndrome – a group of risk factors that raises the likelihood of developing heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.

In fact, further research on cohorts of Barker children – individuals who had low birthweights – has shown that not only have they had higher rates of cardiovascular disease, but they have had higher blood sugars and higher rates of insulin resistance as well.

Today, we appreciate a fuller picture of the Barker data, one that shows a reversal of this trend when birthweights reach 4,000-4,500 grams. At this point, what was a progressively downward slope of cardiovascular mortality rates with increasing birthweight suddenly shoots upward again when birthweight exceeds 4,000 g.

It is this end of the curve that is most relevant – and most concerning – for ob.gyns. today. Our problem in the United States is not so much one of starving or growth-restricted newborns, as these babies account for 5% or less of all births. It is one of overweight and obese newborns who now represent as many as 1 in 7 births. Just like the Barker babies who were growth restricted, these newborns have high insulin levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease as adults.

Changing the trajectory

Both maternal obesity and gestational diabetes get at the heart of the Barker Hypothesis, albeit a twist, in that excessive maternal adiposity and associated insulin resistance results in high maternal blood glucose, transferring excessive nutrients to the fetus. This causes accumulation of fat in the fetus and programs the fetus for an increased and persistent risk of adiposity after birth, early-onset metabolic syndrome, and downstream cardiovascular disease in adulthood.

Dr. Dana Dabelea’s sibling study of almost 15 years ago demonstrated the long-term impact of the adverse intrauterine environment associated with maternal diabetes. Matched siblings who were born after their mothers had developed diabetes had almost double the rate of obesity as adolescents, compared with the siblings born before their mothers were diagnosed with diabetes. In childhood, these siblings ate at the same table and came from the same gene pools (with the same fathers), but they experienced dramatically different health outcomes (Diabetes 2000:49:2208-11).

This landmark study has been reproduced by other investigators who have compared children of mothers who had gestational diabetes and/or were overweight, with children whose mothers did not have gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) or were of normal weight. Such studies have consistently shown that, faced with either or both maternal obesity and diabetes in utero, offspring were significantly more likely to become overweight children and adults with insulin resistance and other components of the metabolic syndrome.

Importantly, we have evidence from randomized trials that interventions to treat GDM can effectively reduce rates of newborn obesity. While differences in birthweight between treatment and no-treatment arms have been modest, reductions in neonatal body fat, as measured by skin-fold thickness, the ponderal index, and birthweight percentile, have been highly significant.

The offspring of mothers who were treated in these trials, the Australian Carbohydrate Intolerance Study in Pregnant Women (N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:2477-86), and a study by Dr. Mark B. Landon and his colleagues (N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1339-48), had approximately half of the newborn adiposity than did offspring of mothers who were not treated. In the latter study, maternal dietary measures alone were successful in reducing neonatal adiposity in over 80% of infants.

While published follow-up data of the offspring in these cohorts have covered only 5-8 years (showing persistently less adiposity in the treated groups), the offspring in the Australian cohort are still being monitored. Based on the cohort and case-control studies summarized above, it seems fair to expect that the children of mothers who were treated for GDM will have significantly better health profiles into and through adulthood.

We know from the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study that what were formerly considered mild and inconsequential maternal blood glucose levels are instead potentially quite harmful. The study showed a clear linear relationship between maternal fasting blood glucose levels, fetal cord blood insulin concentrations (a reflection of fetal glucose levels), and newborn body fat percentage (N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;358:1991-2002).

Interestingly, Dr. Patrick Catalano’s analysis of data from the HAPO study (Diabetes Care 2012;35:780-6) shows us more: Maternal obesity is almost as strong a driver of newborn obesity as is GDM. Compared with GDM (which increased the percentage of infant birthweights to greater than the 90th percentile by a factor of 2.19), maternal obesity alone increased the frequency of LGA by a factor of 1.73, and maternal obesity and GDM together increased LGA newborns by 3.62-fold.

In light of these recent findings, it is critical that we not only treat our patients who have GDM, but that we attempt to interrupt the chain of obesity that passes from mother to fetus, and from obese newborns onto their subsequent offspring.

A growing proportion of women across all race and ethnicity groups gain more than 40 pounds during pregnancy for singleton births, and many of them do not lose the weight between pregnancies. Increasingly, we have patients whose first child may not have been exposed to obesity in utero, but whose second child is exposed to overweight or obesity and higher levels of insulin resistance and glycemia.

The Institute of Medicine documented these issues in its 2009 report, "Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines." Data on maternal postpartum weights are not widely available, but data that have been collected suggest that gaining above recommended ranges is associated with excess maternal weight retention post partum, regardless of prepregnancy BMI. Women who gained above the range recommended by the IOM in 1990 had postpartum weight retention of 15-20 pounds. Among women who gained excessive amounts of weight, moreover, more than 40% retained more than 20 pounds, according to the report.

We must break the intergenerational transfer of obesity and insulin resistance by liberally treating GDM and optimizing glucose control during pregnancy. More importantly, we must emphasize to women the importance of having healthy weights at the time of conception. Recent research affirms that moderately simple interventions, such as dietary improvements and exercise can go a long way to achieving these goals. If we don’t – in keeping with the knowledge spurred on by Dr. Barker – we will be programming more newborns for life with insulin resistance, obesity, and disease.

Dr. Moore is a perinatologist who is chair of the department of reproductive medicine at the University of California, San Diego. He said he had no relevant financial disclosures.

The fetal origins hypothesis