User login

More RNs are delaying retirement, study shows

chemo to a cancer patient

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The nursing workforce in the US has grown substantially in recent years, and this is only partly due to an increase in nursing graduates, according to a new study.

The research revealed that registered nurses (RNs) are putting off retirement for longer than they have in the past.

From 1991 to 2012, 24% of RNs who were working at age 50 remained working as late as age 69. From 1969 to 1990, however, only 9% of nurses were still working at age 69.

These findings appear in Health Affairs.

“We estimate this trend accounts for about a quarter of an unexpected surge in the supply of registered nurses that the nation has experienced in recent years,” said study author David Auerbach, PhD, of RAND Corporation in Boston. “This may provide advantages to parts of the US healthcare system.”

The researchers noted that the RN workforce has surpassed forecasts from a decade ago, growing to 2.7 million in 2012 instead of peaking at 2.2 million as predicted. While much of the difference is the result of a surge in new nursing graduates, the size of the workforce is particularly sensitive to changes in retirement age.

Dr Auerbach and his colleagues uncovered the trend of delaying retirement by analyzing data from the Current Population Survey and the American Community Survey.

The team included all respondents aged 23 to 69 who reported being employed as an RN during the week of the relevant survey from 1969 to 2012. There were 70,724 RNs who responded to the Current Population Survey and 307,187 who responded to the American Community Survey.

The researchers found that, from 1969 to 1990, for a given number of RNs working at age 50, 47% were still working at age 62. From 1991 to 2012, 74% of RNs were working at age 62.

The trend of RNs delaying retirement, which largely predates the recent recession, extended nursing careers by 2.5 years after age 50 and increased the 2012 RN workforce by 136,000 people, according to the researchers.

The team said the reasons older RNs are working longer is unclear, but it is likely part of an overall trend that has seen more Americans—particularly women—stay in the workforce longer because of lengthening life expectancy and the satisfaction they derive from employment. ![]()

chemo to a cancer patient

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The nursing workforce in the US has grown substantially in recent years, and this is only partly due to an increase in nursing graduates, according to a new study.

The research revealed that registered nurses (RNs) are putting off retirement for longer than they have in the past.

From 1991 to 2012, 24% of RNs who were working at age 50 remained working as late as age 69. From 1969 to 1990, however, only 9% of nurses were still working at age 69.

These findings appear in Health Affairs.

“We estimate this trend accounts for about a quarter of an unexpected surge in the supply of registered nurses that the nation has experienced in recent years,” said study author David Auerbach, PhD, of RAND Corporation in Boston. “This may provide advantages to parts of the US healthcare system.”

The researchers noted that the RN workforce has surpassed forecasts from a decade ago, growing to 2.7 million in 2012 instead of peaking at 2.2 million as predicted. While much of the difference is the result of a surge in new nursing graduates, the size of the workforce is particularly sensitive to changes in retirement age.

Dr Auerbach and his colleagues uncovered the trend of delaying retirement by analyzing data from the Current Population Survey and the American Community Survey.

The team included all respondents aged 23 to 69 who reported being employed as an RN during the week of the relevant survey from 1969 to 2012. There were 70,724 RNs who responded to the Current Population Survey and 307,187 who responded to the American Community Survey.

The researchers found that, from 1969 to 1990, for a given number of RNs working at age 50, 47% were still working at age 62. From 1991 to 2012, 74% of RNs were working at age 62.

The trend of RNs delaying retirement, which largely predates the recent recession, extended nursing careers by 2.5 years after age 50 and increased the 2012 RN workforce by 136,000 people, according to the researchers.

The team said the reasons older RNs are working longer is unclear, but it is likely part of an overall trend that has seen more Americans—particularly women—stay in the workforce longer because of lengthening life expectancy and the satisfaction they derive from employment. ![]()

chemo to a cancer patient

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The nursing workforce in the US has grown substantially in recent years, and this is only partly due to an increase in nursing graduates, according to a new study.

The research revealed that registered nurses (RNs) are putting off retirement for longer than they have in the past.

From 1991 to 2012, 24% of RNs who were working at age 50 remained working as late as age 69. From 1969 to 1990, however, only 9% of nurses were still working at age 69.

These findings appear in Health Affairs.

“We estimate this trend accounts for about a quarter of an unexpected surge in the supply of registered nurses that the nation has experienced in recent years,” said study author David Auerbach, PhD, of RAND Corporation in Boston. “This may provide advantages to parts of the US healthcare system.”

The researchers noted that the RN workforce has surpassed forecasts from a decade ago, growing to 2.7 million in 2012 instead of peaking at 2.2 million as predicted. While much of the difference is the result of a surge in new nursing graduates, the size of the workforce is particularly sensitive to changes in retirement age.

Dr Auerbach and his colleagues uncovered the trend of delaying retirement by analyzing data from the Current Population Survey and the American Community Survey.

The team included all respondents aged 23 to 69 who reported being employed as an RN during the week of the relevant survey from 1969 to 2012. There were 70,724 RNs who responded to the Current Population Survey and 307,187 who responded to the American Community Survey.

The researchers found that, from 1969 to 1990, for a given number of RNs working at age 50, 47% were still working at age 62. From 1991 to 2012, 74% of RNs were working at age 62.

The trend of RNs delaying retirement, which largely predates the recent recession, extended nursing careers by 2.5 years after age 50 and increased the 2012 RN workforce by 136,000 people, according to the researchers.

The team said the reasons older RNs are working longer is unclear, but it is likely part of an overall trend that has seen more Americans—particularly women—stay in the workforce longer because of lengthening life expectancy and the satisfaction they derive from employment. ![]()

VTE Prevention After Orthopedic Surgery

Each year in the United States, over 1 million adults undergo hip fracture surgery or elective total knee or hip arthroplasty.[1] Although highly effective for improving functional status and quality of life,[2, 3] each of these procedures is associated with a substantial risk of developing a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).[4, 5] Collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), these clots in the venous system are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for patients, as well as substantial costs to the healthcare system.[6] Although VTE is considered to be a preventable cause of hospital admission and death,[7, 8] the postoperative setting presents a particular challenge, as efforts to reduce clotting must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

Despite how common this scenario is, there is no consensus regarding the best pharmacologic strategy. National guidelines recommend pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, leaving the clinician to select the specific agent.[4, 5] Explicitly endorsed options include aspirin, vitamin K antagonists (VKA), unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) and IIa/Xa factor inhibitors. Among these, aspirin, the only nonanticoagulant, has been the source of greatest controversy.[4, 9, 10]

Two previous systematic reviews comparing aspirin to anticoagulation for VTE prevention found conflicting results.[11, 12] In addition, both used indirect comparisons, a method in which the intervention and comparison data come from different studies, and susceptibility to confounding is high.[13, 14] We aimed to overcome the limitations of prior efforts to address this commonly encountered clinical question by conducting a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials that directly compared the efficacy and safety of aspirin to anticoagulants for VTE prevention in adults undergoing common high‐risk major orthopedic surgeries of the lower extremities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Review Protocol

Prior to conducting the review, we outlined an approach to identifying and selecting eligible studies, prespecified outcomes of interest, and planned subgroup analyses. The meta‐analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses and Cochrane guidelines.[15, 16]

Study Eligibility Criteria

We prespecified the following inclusion criteria: (1) the design was a randomized controlled trial; (2) the population consisted of patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery including hip fracture surgery or total knee or hip arthroplasty; (3) the study compared aspirin to 1 or more anticoagulants: VKA, unfractionated heparin, LMWH, thrombin inhibitors, pentasaccharides (eg, fondaparinux), factor Xa/IIa inhibitors dosed for VTE prevention; (4) subjects were followed for at least 7 days; and (5) the study reported at least 1 prespecified outcome of interest. We allowed the use of pneumatic compression devices, as long as devices were used in both arms of the study.

Outcome Measures

We designated the rate of proximal DVT (occurring in the popliteal vein and above) as the primary outcome of interest. Additional efficacy outcomes included rates of PE, PE‐related mortality, and all‐cause mortality. We required that DVT and PE were diagnosed by venography, computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest, pulmonary angiography, ultrasound Doppler of the legs, or ventilation/perfusion scan. We allowed studies that screened participants for VTE (including the use of fibrinogen leg scanning).

A bleeding event was defined as any need for postoperative blood transfusion or otherwise clinically significant bleeding (eg, prolonged postoperative wound bleeding). We further defined major bleeding as the requirement for blood transfusion of more than 2 U, hematoma requiring surgical evacuation, and bleeding into a critical organ.

Study Identification

We searched Medline (January 1948 to June 2013), Cochrane Library (through June 2013), and CINAHL (January 1974 to June 2013) to locate studies meeting our inclusion criteria. We used exploded Medical Subject Headings terms and key words to generate sets for aspirin and major orthopedic surgery themes, then used the Boolean term, AND, to find their intersection.

Additional Search Methods

We manually reviewed references of relevant articles and searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any ongoing studies or unpublished data. We further searched the following sources: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines,[4, 17] American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines (AAOS),[5] and annual meeting abstracts of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery,[18] the American Society of Hematology,[19] and the ACCP.[20]

Study Selection

Two pairs of 2 reviewers independently scanned the titles and abstracts of identified studies, excluding only those that were clearly not relevant. The same reviewers independently reviewed the full text of each remaining study to make final decisions about eligibility.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted data from each included study and rendered judgments regarding the methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.[21]

Data Synthesis

We used Review Manager (RevMan 5.1) to calculate pooled risk ratios using the Mantel‐Haenszel method and random‐effects models, which take into account the presence of variability among included studies.[16, 22] We also manually pooled absolute event rates for each study arm using the study weights assigned in the pooled risk ratio models.

Assessment of Heterogeneity and Reporting Biases

We assessed statistical variability among the studies contributing to each summary estimate and considered studies unacceptably heterogeneous if the test for heterogeneity P value was <0.10 or the I2 exceeded 50%.[14, 16] We constructed funnel plots to assess for publication bias but had too few studies for reliable interpretation.

Subgroup Analyses

We prespecified subgroup analyses based on the indication for the surgery: hip fracture surgery versus total knee or hip arthroplasty, and according to class of anticoagulation used: VKA versus heparin compounds.

RESULTS

Results of Search

Figure 1 shows the number of studies that we evaluated during each stage of the study selection process. After full‐text review, 8 randomized trials met all inclusion criteria.[23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]

Included Studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 8 included randomized trials. All were published in peer‐reviewed journals from 1982 through 2006.2330 The trials included a combined total of 1408 subjects, and took place in 4 different countries, including the United States,[24, 26, 28, 29, 30] Spain,[23] Sweden,[27] and Canada.[25] Enrolled patients had a mean age of 76 years (range, 7477 years) among hip fracture surgery studies and 66 years (range, 5969 years) among elective knee/hip arthroplasty studies.

| Author, Year | Surgery | Pneumatic Compression | Intervention | Control | Duration (Days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (Total/Day) | No. | Mean Age, Years | Anticoagulant | No. | Mean Age, Years | ||||

| |||||||||

| Powers, 1989 | Hip fracture | No | 1,300 mg | 66 | 73 | Warfarin | 65 | 75 | 21 |

| Gent, 1996 | Hip fracture | No | 200 mg | 126* | 77 | Danaparoid | 125* | 77 | 11 |

| Harris, 1982 | THA | No | 1,200 mg | 51 | 58 | Heparin or warfarin | 75 | 60 | 21 |

| Alfaro, 1986 | THA | No | 250 mg/1,000 mg | 60 | 64 | Heparin | 30 | 58 | 7 |

| Josefsson, 1987 | THA | No | 3,000 mg | 40 | N/A | Heparin | 42 | N/A | 9 |

| Woolson, 1991 | THA | Yes | 1,300 mg | 72 | 62 | Warfarin | 69 | 68 | 7 |

| Lotke, 1996 | THA or TKA | No | 650 mg | 166 | 66 | Warfarin | 146 | 67 | 9 |

| Westrich, 2006 | TKA | Yes | 650 mg | 136 | 69 | Enoxaparin | 139 | 69 | 21 |

Pneumatic compression devices were used in addition to pharmacologic prevention in 2 studies.[29, 30] The different classes of anticoagulants used included warfarin,[26, 28, 30] heparin,[23, 27] LMWH,[29] heparin or warfarin,[24] and danaparoid.[25] Treatment duration was 7 to 21 days. Clinical follow‐up extended up to 6 months after surgery. Patients in all included studies were screened for DVT during the trial period by I‐fibrinogen leg scanning,[23, 25, 26, 27] venography,[24, 28] or ultrasound[29, 30]; some trials also screened all participants for PE with ventilation/perfusion scanning.[27, 28]

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Only 3 studies described their method of random sequence generation,[24, 25, 26] and 2 studies specified their method of allocation concealment.[25, 26] Only 1 study used placebo controls to double blind the study arm assignments.[25] We judged the overall potential risk of bias among the eligible studies to be moderate.

Rate of Proximal DVT

Pooling findings of all 7 studies that reported proximal DVT rates, we observed no statistically significant difference between aspirin and anticoagulants (10.4% vs 9.2%, relative risk [RR]: 1.15 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.68‐1.96], I2=41%). Although rates did not statistically differ between aspirin and anticoagulants in either operative subgroup, there appeared to be a nonsignificant trend favoring anticoagulation after hip fracture repair (12.7% vs 7.8%, RR: 1.60 [95% CI: 0.80‐3.20], I2=0%, 2 trials) but not following knee or hip arthroplasty (9.3% vs 9.7%, RR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.49‐2.05], I2=49%, 5 trials) (Figure 2).

Rate of Pulmonary Embolism

Just 14 participants experienced a PE across all 6 trials reporting this outcome (aspirin n=9/405 versus anticoagulation n=5/415). Although PE was numerically more likely in the aspirin group, this difference was not statistically significant (overall: 1.9% vs 0.9%, RR: 1.83 [95% CI: 0.64, 5.21], I2=0%). The very small number of events rendered extremely wide 95% CIs in operative subgroup analyses (Figure 3).

Rates of All‐Cause Mortality

Only 2 trials, both evaluating aspirin versus anticoagulation following hip fracture repair, reported death events, both after 3 months follow‐up.[25, 26] Pooling these results, there was no statistically significant difference (7.3% vs 6.8%, RR: 1.07 [95% CI: 0.512.21], I2=0%).

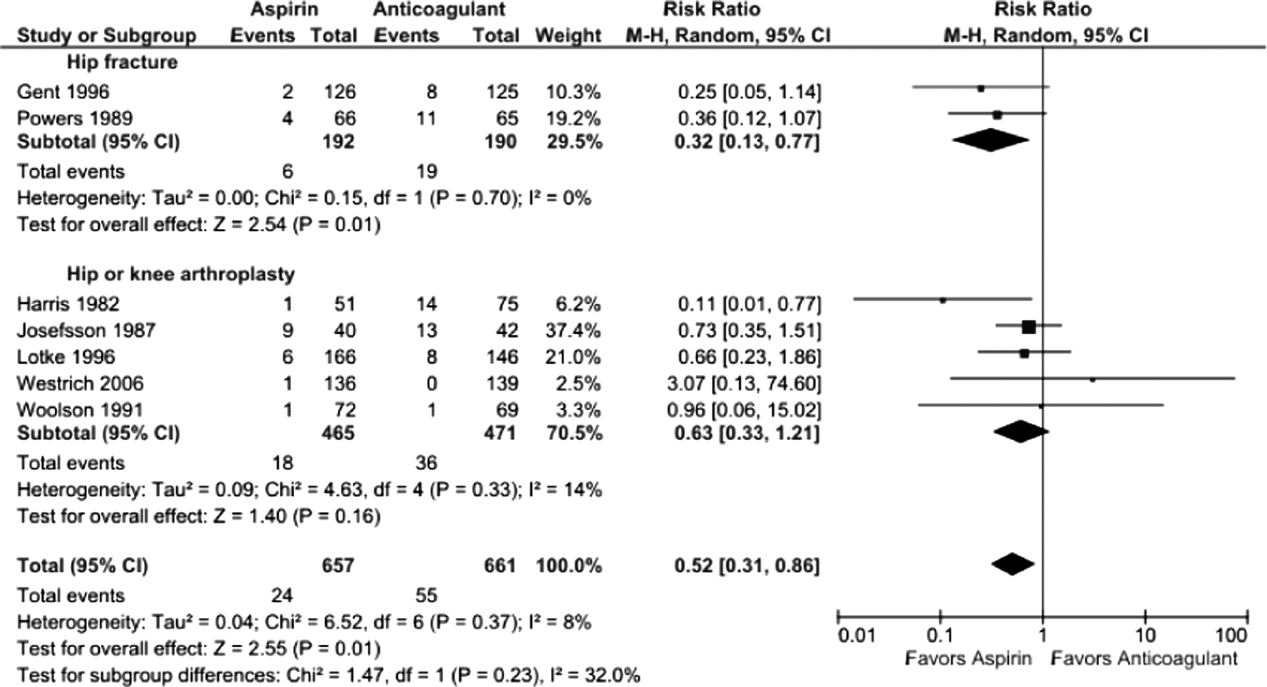

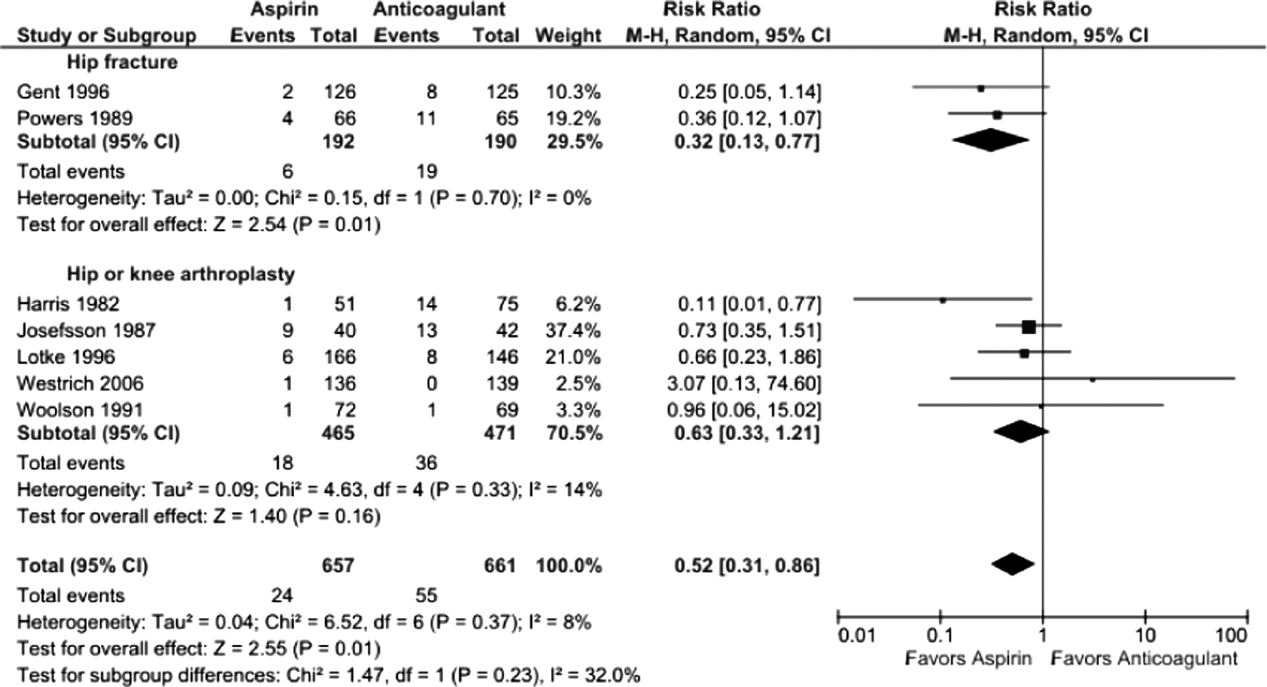

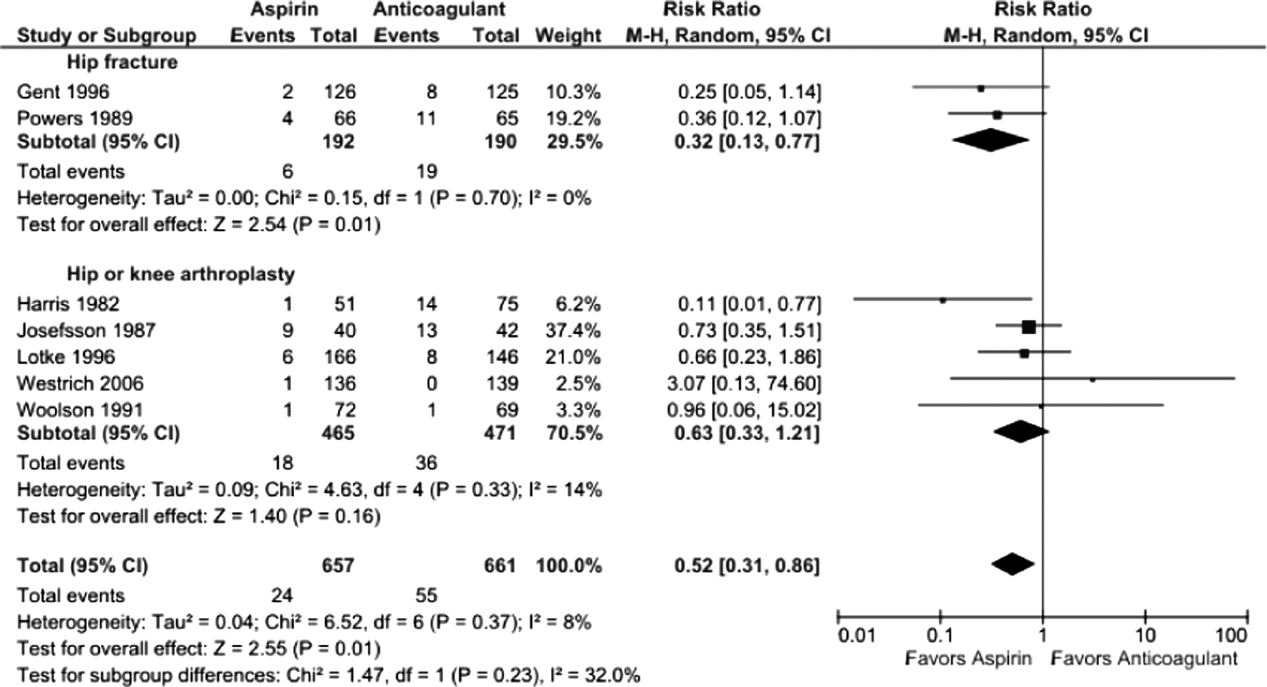

Bleeding Rates

Pooling all 8 studies, aspirin was associated with a statistically significant 48% decreased risk of bleeding events compared to anticoagulants (3.8% vs 8.0%, RR: 0.52 [95% CI: 0.310.86], I2=8%). When subgrouped according to procedure, bleeding rates remained statistically significantly lower in the aspirin group following hip fracture (3.1% vs 10%, RR: 0.32 [95% CI: 0.130.77], I2=0%, 2 trials); however, the observed trend favoring aspirin was not statistically significant following arthroplasty (3.9% vs 7.8%, RR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.331.21], I2=14%, 5 trials) (Figure 4).

Five studies reported major bleeding; event rates were low and no statistically significant differences between aspirin and anticoagulants were observed (hip fracture: 3.5% vs 6.3%, RR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.141.48], I2=0%, 2 trials; knee/hip arthroplasty: 2.1% vs 0.6%, RR: 2.86 [95% CI: 0.6512.60], I2=0%, 3 trials).

Subgroup Analysis

Rates of proximal DVT did not differ between aspirin and anticoagulants when subgrouped according to anticoagulant class (aspirin vs warfarin: 9.7% vs 10.7%, RR: 0.90 [95% CI: 0.561.45], I2=0%, 3 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 10.5% vs 7.9%, RR: 1.37 [95% CI: 0.473.96], I2=44%, 4 trials) (data not shown).

Bleeding rates were lower with aspirin when subgrouped according to type of anticoagulant, but the finding was only statistically significant when compared to VKA (aspirin vs VKA: 4.2% vs 11.1%, RR: 0.43 [95% CI: 0.220.86] I2=0%, 4 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 3.7% vs 7.7%, RR: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.151.28], I2=44, 4 trials) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found the balance of risk versus benefit of aspirin compared to anticoagulation differed markedly according to type of surgery. After hip fracture repair, we found a 68% reduction in bleeding risk with aspirin compared to anticoagulants. This benefit, however, was associated with a nonsignificant increase in screen‐detected proximal DVT. Conversely, among patients undergoing knee or hip arthroplasty, we found no difference in proximal DVT risk between aspirin and anticoagulants and a possible trend toward less bleeding risk with aspirin. The rarity of pulmonary emboli (and death) made meaningful comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation impossible for either type of surgery.

Our systematic review has several strengths that differentiate it from previous analyses. First, we only included head‐to‐head randomized trials such that all included data reflect direct comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation in well‐balanced populations. Conversely, both recent reviews[11, 12] were based on indirect comparisons, a type of analysis in which data for the intervention and control arms are taken from different studies and thus different populations. This methodology is not recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration[13, 14] because of the increased risk of an unbalanced comparison. For example, Brown and colleagues' meta‐analysis, which pooled data from selected arms of 14 randomized controlled trials, found the efficacy of aspirin comparable to that of anticoagulants, but all aspirin subjects came from a single trial of patients at such low risk of VTE that a placebo arm was considered justified.[31] Similarly, in the indirect comparison of Westrich and colleagues,[12] which found anticoagulation superior to aspirin, the likelihood of an unbalanced comparison was further heightened by their inclusion of observational studies, with the attendant risk of confounding by indication.

Our systematic review further differs from previous analyses by examining both beneficial and harmful clinical outcomes, and doing so separately for the 2 most common types of major orthopedic lower extremity surgery. This allowed us to discover important differences in the comparative efficacy (benefit vs harm) of aspirin versus anticoagulants across different procedure types. Finding that aspirin may have lower efficacy for preventing VTE following hip fracture repair than arthroplasty may not be surprising in light of the nature of the 2 procedures, the disparate mean ages typical of patients who undergo each procedure, and the underlying trauma in hip fracture patients.

The limitations of our review largely reflect the quality of the studies we were able to include. First, our pooled sample size remains relatively small, meaning that observed nonsignificant differences between aspirin and anticoagulation groups (eg, a nonsignificant 60% increased risk of DVT for aspirin after hip repair, 95% CI: 0.803.20) could reasonably reflect up to 3‐fold differences in DVT risk and 5‐fold differences in PE rates. Second, screening for DVT, which is neither recommended nor common in clinical practice, was used in all studies. Reported DVT incidence, therefore, is undoubtedly higher than what would be observed in practice; however, the effect on the direction and magnitude of observed relative risks is unpredictable. Third, included studies used a wide range of aspirin doses, as well as a variety of anticoagulant types. Although supratherapeutic aspirin doses are unlikely to confer additional benefit for venous thromboprophylaxis, they may be associated with excess bleeding risk.[32] Finally, several of the studies were conducted more than10 years ago. Given changes in treatment practices, surgical technique, and prophylaxis options, the findings of these studies may not reflect current practice, in which early mobilization and intermittent pneumatic compression devices are standard prophylaxis against postoperative VTE. In fact, only 2 trials used concomitant pneumatic compression devices, and none treated patients longer than 21 days, the current standard being up to 35 days.[4] Although these limitations may affect overall event rates, this bias should be balanced between comparison groups, because we only included randomized controlled trials.

What is a clinician to do? Based on our findings, current guidelines recommending aspirin prophylaxis against VTE as an alternative following major lower extremity surgery may not be universally appropriate. We found that although overall bleeding complications are lower with aspirin, concerns about poor efficacy remain, specifically for patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Although some have suggested that aspirin use be restricted to low risk patients, this strategy has not been experimentally evaluated.[33] On the other hand, switching to aspirin after a brief initial course of LMWH may be an approach warranting further study, in light of a recent randomized controlled trial of 778 patients after elective hip replacement, which found equivalent efficacy using 10 days of LMWH followed by aspirin versus additional LMWH for 28 days.[34]

We are able to be more definitive, based on our study of best available trial data, in making recommendations to investigators embarking on further study of optimal VTE prophylaxis following major orthopedic surgery. First, distinguishing a priori between the 2 major types of lower extremity major orthopedic surgery is a high priority. Second, both bleeding and thromboembolic outcomes must be evaluated. Third, only symptomatic events should be used to measure VTE outcomes; clinical follow‐up must continue well beyond discharge, for at least 3 months to ensure ascertainment of clinically relevant VTE. Fourth, nonpharmacologic cointerventions should be standardized and represent the standard of care, including early immobilization and mechanical compression devices.

In summary, although definitive recommendations for or against the use of aspirin instead of anticoagulation for VTE prevention following major orthopedic surgery are not possible, our findings suggest that, following hip fracture repair, the lower risk of bleeding with aspirin is likely outweighed by a probable trend toward higher risk of VTE. On the other hand, the balance of these opposing risks may favor aspirin after elective knee or hip arthroplasty. A comparative study of aspirin, anticoagulation, and a hybrid strategy (eg, brief anticoagulation followed by aspirin) after elective knee or hip arthroplasty should be a high priority given our aging population and increasing demand for major orthopedic lower extremity surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Deborah Ornstein (Associate Professor of Medicine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Section of Hematology Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, Lebanon, New Hampshire) for sparking the idea for this systematic review.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , et al. Outcomes after hip or knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study comparing patients' quality of life before and after surgery with age‐related population norms. Med J Aust. 1999;171(5):235–238.

- , , . Quality of life and functional outcome after primary total hip replacement. A five‐year follow‐up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(7):868–873.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2011. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , . Economic burden of deep‐vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post‐thrombotic syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(20 suppl 6):S5–S15.

- , . Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med. 1989;82(4):203–205.

- , , . Autopsy‐verified pulmonary embolism in a surgical department: analysis of the period from 1951 to 1988. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):849–852.

- . What is the state of the art in orthopaedic thromboprophylaxis in lower extremity reconstruction? Instr Course Lect. 2011;60:283–290.

- , . Aspirin for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients: a comparison of the AAOS and ACCP guidelines with review of the evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(1):63–74.

- . Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 supplement 1):77–83.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):795–800.

- , , , , , . Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ. 2009;338:b1147.

- Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , ; the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- , , , et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

- , , , et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts‐Blood. Available at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/site/misc/ASH_Meeting_Abstracts_Info.xhtml. Accessed June 2013.

- CHEST Publications Meeting Abstracts. Available at: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ss/meetingabstracts.aspx. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- , , . Prophylaxis of thromboembolic disease and platelet‐related changes following total hip replacement: a comparative study of aspirin and heparin‐dihydroergotamine. Thromb Haemost. 1986;56(1):53–56.

- , , , . High and low‐dose aspirin prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic disease in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(1):63–66.

- , , , et al. Low‐molecular‐weight heparinoid orgaran is more effective than aspirin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery for hip fracture. Circulation. 1996;93(1):80–84.

- , , , et al. A randomized trial of less intense postoperative warfarin or aspirin therapy in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery for fractured hip. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(4):771–774.

- , , . Prevention of thromboembolism in total hip replacement. Aspirin versus dihydroergotamine‐heparin. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58(6):626–629.

- , , , et al. Aspirin and warfarin for thromboembolic disease after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(324):251–258.

- , , , , , . VenaFlow plus Lovenox vs VenaFlow plus aspirin for thromboembolic disease prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6 suppl 2):139–143.

- , . Intermittent pneumatic compression to prevent proximal deep venous thrombosis during and after total hip replacement. A prospective, randomized study of compression alone, compression and aspirin, and compression and low‐dose warfarin. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(4):507–512.

- Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9212):1295–1302.

- , , , et al. Safety and efficacy of high‐ versus low‐dose aspirin after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS‐AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(12):1231–1238.

- Intermountain Joint Replacement Center Writing Committee. A prospective comparison of warfarin to aspirin for thromboprophylaxis in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;27:e1–e9.

- , , , et al. Aspirin versus low‐molecular‐weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):800–806.

Each year in the United States, over 1 million adults undergo hip fracture surgery or elective total knee or hip arthroplasty.[1] Although highly effective for improving functional status and quality of life,[2, 3] each of these procedures is associated with a substantial risk of developing a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).[4, 5] Collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), these clots in the venous system are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for patients, as well as substantial costs to the healthcare system.[6] Although VTE is considered to be a preventable cause of hospital admission and death,[7, 8] the postoperative setting presents a particular challenge, as efforts to reduce clotting must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

Despite how common this scenario is, there is no consensus regarding the best pharmacologic strategy. National guidelines recommend pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, leaving the clinician to select the specific agent.[4, 5] Explicitly endorsed options include aspirin, vitamin K antagonists (VKA), unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) and IIa/Xa factor inhibitors. Among these, aspirin, the only nonanticoagulant, has been the source of greatest controversy.[4, 9, 10]

Two previous systematic reviews comparing aspirin to anticoagulation for VTE prevention found conflicting results.[11, 12] In addition, both used indirect comparisons, a method in which the intervention and comparison data come from different studies, and susceptibility to confounding is high.[13, 14] We aimed to overcome the limitations of prior efforts to address this commonly encountered clinical question by conducting a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials that directly compared the efficacy and safety of aspirin to anticoagulants for VTE prevention in adults undergoing common high‐risk major orthopedic surgeries of the lower extremities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Review Protocol

Prior to conducting the review, we outlined an approach to identifying and selecting eligible studies, prespecified outcomes of interest, and planned subgroup analyses. The meta‐analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses and Cochrane guidelines.[15, 16]

Study Eligibility Criteria

We prespecified the following inclusion criteria: (1) the design was a randomized controlled trial; (2) the population consisted of patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery including hip fracture surgery or total knee or hip arthroplasty; (3) the study compared aspirin to 1 or more anticoagulants: VKA, unfractionated heparin, LMWH, thrombin inhibitors, pentasaccharides (eg, fondaparinux), factor Xa/IIa inhibitors dosed for VTE prevention; (4) subjects were followed for at least 7 days; and (5) the study reported at least 1 prespecified outcome of interest. We allowed the use of pneumatic compression devices, as long as devices were used in both arms of the study.

Outcome Measures

We designated the rate of proximal DVT (occurring in the popliteal vein and above) as the primary outcome of interest. Additional efficacy outcomes included rates of PE, PE‐related mortality, and all‐cause mortality. We required that DVT and PE were diagnosed by venography, computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest, pulmonary angiography, ultrasound Doppler of the legs, or ventilation/perfusion scan. We allowed studies that screened participants for VTE (including the use of fibrinogen leg scanning).

A bleeding event was defined as any need for postoperative blood transfusion or otherwise clinically significant bleeding (eg, prolonged postoperative wound bleeding). We further defined major bleeding as the requirement for blood transfusion of more than 2 U, hematoma requiring surgical evacuation, and bleeding into a critical organ.

Study Identification

We searched Medline (January 1948 to June 2013), Cochrane Library (through June 2013), and CINAHL (January 1974 to June 2013) to locate studies meeting our inclusion criteria. We used exploded Medical Subject Headings terms and key words to generate sets for aspirin and major orthopedic surgery themes, then used the Boolean term, AND, to find their intersection.

Additional Search Methods

We manually reviewed references of relevant articles and searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any ongoing studies or unpublished data. We further searched the following sources: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines,[4, 17] American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines (AAOS),[5] and annual meeting abstracts of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery,[18] the American Society of Hematology,[19] and the ACCP.[20]

Study Selection

Two pairs of 2 reviewers independently scanned the titles and abstracts of identified studies, excluding only those that were clearly not relevant. The same reviewers independently reviewed the full text of each remaining study to make final decisions about eligibility.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted data from each included study and rendered judgments regarding the methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.[21]

Data Synthesis

We used Review Manager (RevMan 5.1) to calculate pooled risk ratios using the Mantel‐Haenszel method and random‐effects models, which take into account the presence of variability among included studies.[16, 22] We also manually pooled absolute event rates for each study arm using the study weights assigned in the pooled risk ratio models.

Assessment of Heterogeneity and Reporting Biases

We assessed statistical variability among the studies contributing to each summary estimate and considered studies unacceptably heterogeneous if the test for heterogeneity P value was <0.10 or the I2 exceeded 50%.[14, 16] We constructed funnel plots to assess for publication bias but had too few studies for reliable interpretation.

Subgroup Analyses

We prespecified subgroup analyses based on the indication for the surgery: hip fracture surgery versus total knee or hip arthroplasty, and according to class of anticoagulation used: VKA versus heparin compounds.

RESULTS

Results of Search

Figure 1 shows the number of studies that we evaluated during each stage of the study selection process. After full‐text review, 8 randomized trials met all inclusion criteria.[23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]

Included Studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 8 included randomized trials. All were published in peer‐reviewed journals from 1982 through 2006.2330 The trials included a combined total of 1408 subjects, and took place in 4 different countries, including the United States,[24, 26, 28, 29, 30] Spain,[23] Sweden,[27] and Canada.[25] Enrolled patients had a mean age of 76 years (range, 7477 years) among hip fracture surgery studies and 66 years (range, 5969 years) among elective knee/hip arthroplasty studies.

| Author, Year | Surgery | Pneumatic Compression | Intervention | Control | Duration (Days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (Total/Day) | No. | Mean Age, Years | Anticoagulant | No. | Mean Age, Years | ||||

| |||||||||

| Powers, 1989 | Hip fracture | No | 1,300 mg | 66 | 73 | Warfarin | 65 | 75 | 21 |

| Gent, 1996 | Hip fracture | No | 200 mg | 126* | 77 | Danaparoid | 125* | 77 | 11 |

| Harris, 1982 | THA | No | 1,200 mg | 51 | 58 | Heparin or warfarin | 75 | 60 | 21 |

| Alfaro, 1986 | THA | No | 250 mg/1,000 mg | 60 | 64 | Heparin | 30 | 58 | 7 |

| Josefsson, 1987 | THA | No | 3,000 mg | 40 | N/A | Heparin | 42 | N/A | 9 |

| Woolson, 1991 | THA | Yes | 1,300 mg | 72 | 62 | Warfarin | 69 | 68 | 7 |

| Lotke, 1996 | THA or TKA | No | 650 mg | 166 | 66 | Warfarin | 146 | 67 | 9 |

| Westrich, 2006 | TKA | Yes | 650 mg | 136 | 69 | Enoxaparin | 139 | 69 | 21 |

Pneumatic compression devices were used in addition to pharmacologic prevention in 2 studies.[29, 30] The different classes of anticoagulants used included warfarin,[26, 28, 30] heparin,[23, 27] LMWH,[29] heparin or warfarin,[24] and danaparoid.[25] Treatment duration was 7 to 21 days. Clinical follow‐up extended up to 6 months after surgery. Patients in all included studies were screened for DVT during the trial period by I‐fibrinogen leg scanning,[23, 25, 26, 27] venography,[24, 28] or ultrasound[29, 30]; some trials also screened all participants for PE with ventilation/perfusion scanning.[27, 28]

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Only 3 studies described their method of random sequence generation,[24, 25, 26] and 2 studies specified their method of allocation concealment.[25, 26] Only 1 study used placebo controls to double blind the study arm assignments.[25] We judged the overall potential risk of bias among the eligible studies to be moderate.

Rate of Proximal DVT

Pooling findings of all 7 studies that reported proximal DVT rates, we observed no statistically significant difference between aspirin and anticoagulants (10.4% vs 9.2%, relative risk [RR]: 1.15 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.68‐1.96], I2=41%). Although rates did not statistically differ between aspirin and anticoagulants in either operative subgroup, there appeared to be a nonsignificant trend favoring anticoagulation after hip fracture repair (12.7% vs 7.8%, RR: 1.60 [95% CI: 0.80‐3.20], I2=0%, 2 trials) but not following knee or hip arthroplasty (9.3% vs 9.7%, RR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.49‐2.05], I2=49%, 5 trials) (Figure 2).

Rate of Pulmonary Embolism

Just 14 participants experienced a PE across all 6 trials reporting this outcome (aspirin n=9/405 versus anticoagulation n=5/415). Although PE was numerically more likely in the aspirin group, this difference was not statistically significant (overall: 1.9% vs 0.9%, RR: 1.83 [95% CI: 0.64, 5.21], I2=0%). The very small number of events rendered extremely wide 95% CIs in operative subgroup analyses (Figure 3).

Rates of All‐Cause Mortality

Only 2 trials, both evaluating aspirin versus anticoagulation following hip fracture repair, reported death events, both after 3 months follow‐up.[25, 26] Pooling these results, there was no statistically significant difference (7.3% vs 6.8%, RR: 1.07 [95% CI: 0.512.21], I2=0%).

Bleeding Rates

Pooling all 8 studies, aspirin was associated with a statistically significant 48% decreased risk of bleeding events compared to anticoagulants (3.8% vs 8.0%, RR: 0.52 [95% CI: 0.310.86], I2=8%). When subgrouped according to procedure, bleeding rates remained statistically significantly lower in the aspirin group following hip fracture (3.1% vs 10%, RR: 0.32 [95% CI: 0.130.77], I2=0%, 2 trials); however, the observed trend favoring aspirin was not statistically significant following arthroplasty (3.9% vs 7.8%, RR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.331.21], I2=14%, 5 trials) (Figure 4).

Five studies reported major bleeding; event rates were low and no statistically significant differences between aspirin and anticoagulants were observed (hip fracture: 3.5% vs 6.3%, RR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.141.48], I2=0%, 2 trials; knee/hip arthroplasty: 2.1% vs 0.6%, RR: 2.86 [95% CI: 0.6512.60], I2=0%, 3 trials).

Subgroup Analysis

Rates of proximal DVT did not differ between aspirin and anticoagulants when subgrouped according to anticoagulant class (aspirin vs warfarin: 9.7% vs 10.7%, RR: 0.90 [95% CI: 0.561.45], I2=0%, 3 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 10.5% vs 7.9%, RR: 1.37 [95% CI: 0.473.96], I2=44%, 4 trials) (data not shown).

Bleeding rates were lower with aspirin when subgrouped according to type of anticoagulant, but the finding was only statistically significant when compared to VKA (aspirin vs VKA: 4.2% vs 11.1%, RR: 0.43 [95% CI: 0.220.86] I2=0%, 4 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 3.7% vs 7.7%, RR: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.151.28], I2=44, 4 trials) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found the balance of risk versus benefit of aspirin compared to anticoagulation differed markedly according to type of surgery. After hip fracture repair, we found a 68% reduction in bleeding risk with aspirin compared to anticoagulants. This benefit, however, was associated with a nonsignificant increase in screen‐detected proximal DVT. Conversely, among patients undergoing knee or hip arthroplasty, we found no difference in proximal DVT risk between aspirin and anticoagulants and a possible trend toward less bleeding risk with aspirin. The rarity of pulmonary emboli (and death) made meaningful comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation impossible for either type of surgery.

Our systematic review has several strengths that differentiate it from previous analyses. First, we only included head‐to‐head randomized trials such that all included data reflect direct comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation in well‐balanced populations. Conversely, both recent reviews[11, 12] were based on indirect comparisons, a type of analysis in which data for the intervention and control arms are taken from different studies and thus different populations. This methodology is not recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration[13, 14] because of the increased risk of an unbalanced comparison. For example, Brown and colleagues' meta‐analysis, which pooled data from selected arms of 14 randomized controlled trials, found the efficacy of aspirin comparable to that of anticoagulants, but all aspirin subjects came from a single trial of patients at such low risk of VTE that a placebo arm was considered justified.[31] Similarly, in the indirect comparison of Westrich and colleagues,[12] which found anticoagulation superior to aspirin, the likelihood of an unbalanced comparison was further heightened by their inclusion of observational studies, with the attendant risk of confounding by indication.

Our systematic review further differs from previous analyses by examining both beneficial and harmful clinical outcomes, and doing so separately for the 2 most common types of major orthopedic lower extremity surgery. This allowed us to discover important differences in the comparative efficacy (benefit vs harm) of aspirin versus anticoagulants across different procedure types. Finding that aspirin may have lower efficacy for preventing VTE following hip fracture repair than arthroplasty may not be surprising in light of the nature of the 2 procedures, the disparate mean ages typical of patients who undergo each procedure, and the underlying trauma in hip fracture patients.

The limitations of our review largely reflect the quality of the studies we were able to include. First, our pooled sample size remains relatively small, meaning that observed nonsignificant differences between aspirin and anticoagulation groups (eg, a nonsignificant 60% increased risk of DVT for aspirin after hip repair, 95% CI: 0.803.20) could reasonably reflect up to 3‐fold differences in DVT risk and 5‐fold differences in PE rates. Second, screening for DVT, which is neither recommended nor common in clinical practice, was used in all studies. Reported DVT incidence, therefore, is undoubtedly higher than what would be observed in practice; however, the effect on the direction and magnitude of observed relative risks is unpredictable. Third, included studies used a wide range of aspirin doses, as well as a variety of anticoagulant types. Although supratherapeutic aspirin doses are unlikely to confer additional benefit for venous thromboprophylaxis, they may be associated with excess bleeding risk.[32] Finally, several of the studies were conducted more than10 years ago. Given changes in treatment practices, surgical technique, and prophylaxis options, the findings of these studies may not reflect current practice, in which early mobilization and intermittent pneumatic compression devices are standard prophylaxis against postoperative VTE. In fact, only 2 trials used concomitant pneumatic compression devices, and none treated patients longer than 21 days, the current standard being up to 35 days.[4] Although these limitations may affect overall event rates, this bias should be balanced between comparison groups, because we only included randomized controlled trials.

What is a clinician to do? Based on our findings, current guidelines recommending aspirin prophylaxis against VTE as an alternative following major lower extremity surgery may not be universally appropriate. We found that although overall bleeding complications are lower with aspirin, concerns about poor efficacy remain, specifically for patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Although some have suggested that aspirin use be restricted to low risk patients, this strategy has not been experimentally evaluated.[33] On the other hand, switching to aspirin after a brief initial course of LMWH may be an approach warranting further study, in light of a recent randomized controlled trial of 778 patients after elective hip replacement, which found equivalent efficacy using 10 days of LMWH followed by aspirin versus additional LMWH for 28 days.[34]

We are able to be more definitive, based on our study of best available trial data, in making recommendations to investigators embarking on further study of optimal VTE prophylaxis following major orthopedic surgery. First, distinguishing a priori between the 2 major types of lower extremity major orthopedic surgery is a high priority. Second, both bleeding and thromboembolic outcomes must be evaluated. Third, only symptomatic events should be used to measure VTE outcomes; clinical follow‐up must continue well beyond discharge, for at least 3 months to ensure ascertainment of clinically relevant VTE. Fourth, nonpharmacologic cointerventions should be standardized and represent the standard of care, including early immobilization and mechanical compression devices.

In summary, although definitive recommendations for or against the use of aspirin instead of anticoagulation for VTE prevention following major orthopedic surgery are not possible, our findings suggest that, following hip fracture repair, the lower risk of bleeding with aspirin is likely outweighed by a probable trend toward higher risk of VTE. On the other hand, the balance of these opposing risks may favor aspirin after elective knee or hip arthroplasty. A comparative study of aspirin, anticoagulation, and a hybrid strategy (eg, brief anticoagulation followed by aspirin) after elective knee or hip arthroplasty should be a high priority given our aging population and increasing demand for major orthopedic lower extremity surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Deborah Ornstein (Associate Professor of Medicine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Section of Hematology Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, Lebanon, New Hampshire) for sparking the idea for this systematic review.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

Each year in the United States, over 1 million adults undergo hip fracture surgery or elective total knee or hip arthroplasty.[1] Although highly effective for improving functional status and quality of life,[2, 3] each of these procedures is associated with a substantial risk of developing a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE).[4, 5] Collectively referred to as venous thromboembolism (VTE), these clots in the venous system are associated with significant morbidity and mortality for patients, as well as substantial costs to the healthcare system.[6] Although VTE is considered to be a preventable cause of hospital admission and death,[7, 8] the postoperative setting presents a particular challenge, as efforts to reduce clotting must be balanced against the risk of bleeding.

Despite how common this scenario is, there is no consensus regarding the best pharmacologic strategy. National guidelines recommend pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis, leaving the clinician to select the specific agent.[4, 5] Explicitly endorsed options include aspirin, vitamin K antagonists (VKA), unfractionated heparin, fondaparinux, low‐molecular‐weight heparin (LMWH) and IIa/Xa factor inhibitors. Among these, aspirin, the only nonanticoagulant, has been the source of greatest controversy.[4, 9, 10]

Two previous systematic reviews comparing aspirin to anticoagulation for VTE prevention found conflicting results.[11, 12] In addition, both used indirect comparisons, a method in which the intervention and comparison data come from different studies, and susceptibility to confounding is high.[13, 14] We aimed to overcome the limitations of prior efforts to address this commonly encountered clinical question by conducting a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials that directly compared the efficacy and safety of aspirin to anticoagulants for VTE prevention in adults undergoing common high‐risk major orthopedic surgeries of the lower extremities.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Review Protocol

Prior to conducting the review, we outlined an approach to identifying and selecting eligible studies, prespecified outcomes of interest, and planned subgroup analyses. The meta‐analysis was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses and Cochrane guidelines.[15, 16]

Study Eligibility Criteria

We prespecified the following inclusion criteria: (1) the design was a randomized controlled trial; (2) the population consisted of patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery including hip fracture surgery or total knee or hip arthroplasty; (3) the study compared aspirin to 1 or more anticoagulants: VKA, unfractionated heparin, LMWH, thrombin inhibitors, pentasaccharides (eg, fondaparinux), factor Xa/IIa inhibitors dosed for VTE prevention; (4) subjects were followed for at least 7 days; and (5) the study reported at least 1 prespecified outcome of interest. We allowed the use of pneumatic compression devices, as long as devices were used in both arms of the study.

Outcome Measures

We designated the rate of proximal DVT (occurring in the popliteal vein and above) as the primary outcome of interest. Additional efficacy outcomes included rates of PE, PE‐related mortality, and all‐cause mortality. We required that DVT and PE were diagnosed by venography, computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest, pulmonary angiography, ultrasound Doppler of the legs, or ventilation/perfusion scan. We allowed studies that screened participants for VTE (including the use of fibrinogen leg scanning).

A bleeding event was defined as any need for postoperative blood transfusion or otherwise clinically significant bleeding (eg, prolonged postoperative wound bleeding). We further defined major bleeding as the requirement for blood transfusion of more than 2 U, hematoma requiring surgical evacuation, and bleeding into a critical organ.

Study Identification

We searched Medline (January 1948 to June 2013), Cochrane Library (through June 2013), and CINAHL (January 1974 to June 2013) to locate studies meeting our inclusion criteria. We used exploded Medical Subject Headings terms and key words to generate sets for aspirin and major orthopedic surgery themes, then used the Boolean term, AND, to find their intersection.

Additional Search Methods

We manually reviewed references of relevant articles and searched ClinicalTrials.gov to identify any ongoing studies or unpublished data. We further searched the following sources: American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) Evidence‐Based Clinical Practice Guidelines,[4, 17] American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines (AAOS),[5] and annual meeting abstracts of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgery,[18] the American Society of Hematology,[19] and the ACCP.[20]

Study Selection

Two pairs of 2 reviewers independently scanned the titles and abstracts of identified studies, excluding only those that were clearly not relevant. The same reviewers independently reviewed the full text of each remaining study to make final decisions about eligibility.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two reviewers independently extracted data from each included study and rendered judgments regarding the methodological quality using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool.[21]

Data Synthesis

We used Review Manager (RevMan 5.1) to calculate pooled risk ratios using the Mantel‐Haenszel method and random‐effects models, which take into account the presence of variability among included studies.[16, 22] We also manually pooled absolute event rates for each study arm using the study weights assigned in the pooled risk ratio models.

Assessment of Heterogeneity and Reporting Biases

We assessed statistical variability among the studies contributing to each summary estimate and considered studies unacceptably heterogeneous if the test for heterogeneity P value was <0.10 or the I2 exceeded 50%.[14, 16] We constructed funnel plots to assess for publication bias but had too few studies for reliable interpretation.

Subgroup Analyses

We prespecified subgroup analyses based on the indication for the surgery: hip fracture surgery versus total knee or hip arthroplasty, and according to class of anticoagulation used: VKA versus heparin compounds.

RESULTS

Results of Search

Figure 1 shows the number of studies that we evaluated during each stage of the study selection process. After full‐text review, 8 randomized trials met all inclusion criteria.[23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30]

Included Studies

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the 8 included randomized trials. All were published in peer‐reviewed journals from 1982 through 2006.2330 The trials included a combined total of 1408 subjects, and took place in 4 different countries, including the United States,[24, 26, 28, 29, 30] Spain,[23] Sweden,[27] and Canada.[25] Enrolled patients had a mean age of 76 years (range, 7477 years) among hip fracture surgery studies and 66 years (range, 5969 years) among elective knee/hip arthroplasty studies.

| Author, Year | Surgery | Pneumatic Compression | Intervention | Control | Duration (Days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (Total/Day) | No. | Mean Age, Years | Anticoagulant | No. | Mean Age, Years | ||||

| |||||||||

| Powers, 1989 | Hip fracture | No | 1,300 mg | 66 | 73 | Warfarin | 65 | 75 | 21 |

| Gent, 1996 | Hip fracture | No | 200 mg | 126* | 77 | Danaparoid | 125* | 77 | 11 |

| Harris, 1982 | THA | No | 1,200 mg | 51 | 58 | Heparin or warfarin | 75 | 60 | 21 |

| Alfaro, 1986 | THA | No | 250 mg/1,000 mg | 60 | 64 | Heparin | 30 | 58 | 7 |

| Josefsson, 1987 | THA | No | 3,000 mg | 40 | N/A | Heparin | 42 | N/A | 9 |

| Woolson, 1991 | THA | Yes | 1,300 mg | 72 | 62 | Warfarin | 69 | 68 | 7 |

| Lotke, 1996 | THA or TKA | No | 650 mg | 166 | 66 | Warfarin | 146 | 67 | 9 |

| Westrich, 2006 | TKA | Yes | 650 mg | 136 | 69 | Enoxaparin | 139 | 69 | 21 |

Pneumatic compression devices were used in addition to pharmacologic prevention in 2 studies.[29, 30] The different classes of anticoagulants used included warfarin,[26, 28, 30] heparin,[23, 27] LMWH,[29] heparin or warfarin,[24] and danaparoid.[25] Treatment duration was 7 to 21 days. Clinical follow‐up extended up to 6 months after surgery. Patients in all included studies were screened for DVT during the trial period by I‐fibrinogen leg scanning,[23, 25, 26, 27] venography,[24, 28] or ultrasound[29, 30]; some trials also screened all participants for PE with ventilation/perfusion scanning.[27, 28]

Methodological Quality of Included Studies

Only 3 studies described their method of random sequence generation,[24, 25, 26] and 2 studies specified their method of allocation concealment.[25, 26] Only 1 study used placebo controls to double blind the study arm assignments.[25] We judged the overall potential risk of bias among the eligible studies to be moderate.

Rate of Proximal DVT

Pooling findings of all 7 studies that reported proximal DVT rates, we observed no statistically significant difference between aspirin and anticoagulants (10.4% vs 9.2%, relative risk [RR]: 1.15 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.68‐1.96], I2=41%). Although rates did not statistically differ between aspirin and anticoagulants in either operative subgroup, there appeared to be a nonsignificant trend favoring anticoagulation after hip fracture repair (12.7% vs 7.8%, RR: 1.60 [95% CI: 0.80‐3.20], I2=0%, 2 trials) but not following knee or hip arthroplasty (9.3% vs 9.7%, RR: 1.00 [95% CI: 0.49‐2.05], I2=49%, 5 trials) (Figure 2).

Rate of Pulmonary Embolism

Just 14 participants experienced a PE across all 6 trials reporting this outcome (aspirin n=9/405 versus anticoagulation n=5/415). Although PE was numerically more likely in the aspirin group, this difference was not statistically significant (overall: 1.9% vs 0.9%, RR: 1.83 [95% CI: 0.64, 5.21], I2=0%). The very small number of events rendered extremely wide 95% CIs in operative subgroup analyses (Figure 3).

Rates of All‐Cause Mortality

Only 2 trials, both evaluating aspirin versus anticoagulation following hip fracture repair, reported death events, both after 3 months follow‐up.[25, 26] Pooling these results, there was no statistically significant difference (7.3% vs 6.8%, RR: 1.07 [95% CI: 0.512.21], I2=0%).

Bleeding Rates

Pooling all 8 studies, aspirin was associated with a statistically significant 48% decreased risk of bleeding events compared to anticoagulants (3.8% vs 8.0%, RR: 0.52 [95% CI: 0.310.86], I2=8%). When subgrouped according to procedure, bleeding rates remained statistically significantly lower in the aspirin group following hip fracture (3.1% vs 10%, RR: 0.32 [95% CI: 0.130.77], I2=0%, 2 trials); however, the observed trend favoring aspirin was not statistically significant following arthroplasty (3.9% vs 7.8%, RR: 0.63 [95% CI: 0.331.21], I2=14%, 5 trials) (Figure 4).

Five studies reported major bleeding; event rates were low and no statistically significant differences between aspirin and anticoagulants were observed (hip fracture: 3.5% vs 6.3%, RR: 0.46 [95% CI: 0.141.48], I2=0%, 2 trials; knee/hip arthroplasty: 2.1% vs 0.6%, RR: 2.86 [95% CI: 0.6512.60], I2=0%, 3 trials).

Subgroup Analysis

Rates of proximal DVT did not differ between aspirin and anticoagulants when subgrouped according to anticoagulant class (aspirin vs warfarin: 9.7% vs 10.7%, RR: 0.90 [95% CI: 0.561.45], I2=0%, 3 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 10.5% vs 7.9%, RR: 1.37 [95% CI: 0.473.96], I2=44%, 4 trials) (data not shown).

Bleeding rates were lower with aspirin when subgrouped according to type of anticoagulant, but the finding was only statistically significant when compared to VKA (aspirin vs VKA: 4.2% vs 11.1%, RR: 0.43 [95% CI: 0.220.86] I2=0%, 4 trials; aspirin vs heparin: 3.7% vs 7.7%, RR: 0.44 [95% CI: 0.151.28], I2=44, 4 trials) (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

We found the balance of risk versus benefit of aspirin compared to anticoagulation differed markedly according to type of surgery. After hip fracture repair, we found a 68% reduction in bleeding risk with aspirin compared to anticoagulants. This benefit, however, was associated with a nonsignificant increase in screen‐detected proximal DVT. Conversely, among patients undergoing knee or hip arthroplasty, we found no difference in proximal DVT risk between aspirin and anticoagulants and a possible trend toward less bleeding risk with aspirin. The rarity of pulmonary emboli (and death) made meaningful comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation impossible for either type of surgery.

Our systematic review has several strengths that differentiate it from previous analyses. First, we only included head‐to‐head randomized trials such that all included data reflect direct comparisons between aspirin and anticoagulation in well‐balanced populations. Conversely, both recent reviews[11, 12] were based on indirect comparisons, a type of analysis in which data for the intervention and control arms are taken from different studies and thus different populations. This methodology is not recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration[13, 14] because of the increased risk of an unbalanced comparison. For example, Brown and colleagues' meta‐analysis, which pooled data from selected arms of 14 randomized controlled trials, found the efficacy of aspirin comparable to that of anticoagulants, but all aspirin subjects came from a single trial of patients at such low risk of VTE that a placebo arm was considered justified.[31] Similarly, in the indirect comparison of Westrich and colleagues,[12] which found anticoagulation superior to aspirin, the likelihood of an unbalanced comparison was further heightened by their inclusion of observational studies, with the attendant risk of confounding by indication.

Our systematic review further differs from previous analyses by examining both beneficial and harmful clinical outcomes, and doing so separately for the 2 most common types of major orthopedic lower extremity surgery. This allowed us to discover important differences in the comparative efficacy (benefit vs harm) of aspirin versus anticoagulants across different procedure types. Finding that aspirin may have lower efficacy for preventing VTE following hip fracture repair than arthroplasty may not be surprising in light of the nature of the 2 procedures, the disparate mean ages typical of patients who undergo each procedure, and the underlying trauma in hip fracture patients.

The limitations of our review largely reflect the quality of the studies we were able to include. First, our pooled sample size remains relatively small, meaning that observed nonsignificant differences between aspirin and anticoagulation groups (eg, a nonsignificant 60% increased risk of DVT for aspirin after hip repair, 95% CI: 0.803.20) could reasonably reflect up to 3‐fold differences in DVT risk and 5‐fold differences in PE rates. Second, screening for DVT, which is neither recommended nor common in clinical practice, was used in all studies. Reported DVT incidence, therefore, is undoubtedly higher than what would be observed in practice; however, the effect on the direction and magnitude of observed relative risks is unpredictable. Third, included studies used a wide range of aspirin doses, as well as a variety of anticoagulant types. Although supratherapeutic aspirin doses are unlikely to confer additional benefit for venous thromboprophylaxis, they may be associated with excess bleeding risk.[32] Finally, several of the studies were conducted more than10 years ago. Given changes in treatment practices, surgical technique, and prophylaxis options, the findings of these studies may not reflect current practice, in which early mobilization and intermittent pneumatic compression devices are standard prophylaxis against postoperative VTE. In fact, only 2 trials used concomitant pneumatic compression devices, and none treated patients longer than 21 days, the current standard being up to 35 days.[4] Although these limitations may affect overall event rates, this bias should be balanced between comparison groups, because we only included randomized controlled trials.

What is a clinician to do? Based on our findings, current guidelines recommending aspirin prophylaxis against VTE as an alternative following major lower extremity surgery may not be universally appropriate. We found that although overall bleeding complications are lower with aspirin, concerns about poor efficacy remain, specifically for patients undergoing hip fracture repair. Although some have suggested that aspirin use be restricted to low risk patients, this strategy has not been experimentally evaluated.[33] On the other hand, switching to aspirin after a brief initial course of LMWH may be an approach warranting further study, in light of a recent randomized controlled trial of 778 patients after elective hip replacement, which found equivalent efficacy using 10 days of LMWH followed by aspirin versus additional LMWH for 28 days.[34]

We are able to be more definitive, based on our study of best available trial data, in making recommendations to investigators embarking on further study of optimal VTE prophylaxis following major orthopedic surgery. First, distinguishing a priori between the 2 major types of lower extremity major orthopedic surgery is a high priority. Second, both bleeding and thromboembolic outcomes must be evaluated. Third, only symptomatic events should be used to measure VTE outcomes; clinical follow‐up must continue well beyond discharge, for at least 3 months to ensure ascertainment of clinically relevant VTE. Fourth, nonpharmacologic cointerventions should be standardized and represent the standard of care, including early immobilization and mechanical compression devices.

In summary, although definitive recommendations for or against the use of aspirin instead of anticoagulation for VTE prevention following major orthopedic surgery are not possible, our findings suggest that, following hip fracture repair, the lower risk of bleeding with aspirin is likely outweighed by a probable trend toward higher risk of VTE. On the other hand, the balance of these opposing risks may favor aspirin after elective knee or hip arthroplasty. A comparative study of aspirin, anticoagulation, and a hybrid strategy (eg, brief anticoagulation followed by aspirin) after elective knee or hip arthroplasty should be a high priority given our aging population and increasing demand for major orthopedic lower extremity surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Deborah Ornstein (Associate Professor of Medicine, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Section of Hematology Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, Lebanon, New Hampshire) for sparking the idea for this systematic review.

Disclosures: Nothing to report.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , et al. Outcomes after hip or knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study comparing patients' quality of life before and after surgery with age‐related population norms. Med J Aust. 1999;171(5):235–238.

- , , . Quality of life and functional outcome after primary total hip replacement. A five‐year follow‐up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(7):868–873.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2011. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , . Economic burden of deep‐vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post‐thrombotic syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(20 suppl 6):S5–S15.

- , . Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med. 1989;82(4):203–205.

- , , . Autopsy‐verified pulmonary embolism in a surgical department: analysis of the period from 1951 to 1988. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):849–852.

- . What is the state of the art in orthopaedic thromboprophylaxis in lower extremity reconstruction? Instr Course Lect. 2011;60:283–290.

- , . Aspirin for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients: a comparison of the AAOS and ACCP guidelines with review of the evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(1):63–74.

- . Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 supplement 1):77–83.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):795–800.

- , , , , , . Methodological problems in the use of indirect comparisons for evaluating healthcare interventions: survey of published systematic reviews. BMJ. 2009;338:b1147.

- Higgins J, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available at: http://handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , ; the PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- , , , et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100.

- , , , et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 suppl):381S–453S.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e195S–e226S.

- ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts‐Blood. Available at: http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/site/misc/ASH_Meeting_Abstracts_Info.xhtml. Accessed June 2013.

- CHEST Publications Meeting Abstracts. Available at: http://journal.publications.chestnet.org/ss/meetingabstracts.aspx. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

- Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.1. Copenhagen, Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- , , . Prophylaxis of thromboembolic disease and platelet‐related changes following total hip replacement: a comparative study of aspirin and heparin‐dihydroergotamine. Thromb Haemost. 1986;56(1):53–56.

- , , , . High and low‐dose aspirin prophylaxis against venous thromboembolic disease in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(1):63–66.

- , , , et al. Low‐molecular‐weight heparinoid orgaran is more effective than aspirin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery for hip fracture. Circulation. 1996;93(1):80–84.

- , , , et al. A randomized trial of less intense postoperative warfarin or aspirin therapy in the prevention of venous thromboembolism after surgery for fractured hip. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(4):771–774.

- , , . Prevention of thromboembolism in total hip replacement. Aspirin versus dihydroergotamine‐heparin. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58(6):626–629.

- , , , et al. Aspirin and warfarin for thromboembolic disease after total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(324):251–258.

- , , , , , . VenaFlow plus Lovenox vs VenaFlow plus aspirin for thromboembolic disease prophylaxis in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6 suppl 2):139–143.

- , . Intermittent pneumatic compression to prevent proximal deep venous thrombosis during and after total hip replacement. A prospective, randomized study of compression alone, compression and aspirin, and compression and low‐dose warfarin. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(4):507–512.

- Prevention of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with low dose aspirin: Pulmonary Embolism Prevention (PEP) trial. Lancet. 2000;355(9212):1295–1302.

- , , , et al. Safety and efficacy of high‐ versus low‐dose aspirin after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST‐segment elevation myocardial infarction: the HORIZONS‐AMI (Harmonizing Outcomes With Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5(12):1231–1238.

- Intermountain Joint Replacement Center Writing Committee. A prospective comparison of warfarin to aspirin for thromboprophylaxis in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;27:e1–e9.

- , , , et al. Aspirin versus low‐molecular‐weight heparin for extended venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip arthroplasty: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(11):800–806.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , et al. Outcomes after hip or knee replacement surgery for osteoarthritis. A prospective cohort study comparing patients' quality of life before and after surgery with age‐related population norms. Med J Aust. 1999;171(5):235–238.

- , , . Quality of life and functional outcome after primary total hip replacement. A five‐year follow‐up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(7):868–873.

- , , , et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 suppl):e278S–e325S.

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons clinical practice guideline on preventing venous thromboembolic disease in patients undergoing elective hip and knee arthroplasty. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2011. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines. Accessed June 2013.

- , , , . Economic burden of deep‐vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and post‐thrombotic syndrome. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(20 suppl 6):S5–S15.

- , . Autopsy proven pulmonary embolism in hospital patients: are we detecting enough deep vein thrombosis? J R Soc Med. 1989;82(4):203–205.

- , , . Autopsy‐verified pulmonary embolism in a surgical department: analysis of the period from 1951 to 1988. Br J Surg. 1991;78(7):849–852.

- . What is the state of the art in orthopaedic thromboprophylaxis in lower extremity reconstruction? Instr Course Lect. 2011;60:283–290.

- , . Aspirin for the prophylaxis of venous thromboembolic events in orthopedic surgery patients: a comparison of the AAOS and ACCP guidelines with review of the evidence. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(1):63–74.

- . Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after major orthopaedic surgery: A pooled analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 supplement 1):77–83.

- , , , . Meta‐analysis of thromboembolic prophylaxis after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(6):795–800.