User login

Antibody may treat cancer cachexia

Preclinical research raises the prospect of more effective treatments for cachexia, a profound wasting of fat and muscle that can increase the risk of death in cancer patients.

In mouse models, an antibody effectively improved or prevented symptoms of cachexia.

The antibody inhibited the effects of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), which is released from many types of cancer cells.

The researchers said their findings, published in Nature, are the first to explain in detail how PTHrP from tumors switches on a thermogenic process in fatty tissues, resulting in unhealthy weight loss.

The team carried out 2 experiments using mice that developed lung tumors and cachexia. In the first, a polyclonal antibody that specifically neutralizes PTHrP prevented cachexia almost completely, while untreated animals became mildly cachexic.

Anti-PTHrP treatment prevented the shrinkage of fat droplets. It blocked thermogenic gene expression in epididymal white adipose tissue, interscapular brown adipose tissue, and inguinal white adipose tissue, which suggests thermogenesis has a causal role in fat wasting.

Treatment with the anti-PTHrP antibody also lowered oxygen consumption in the mice, increased their physical activity, and reduced their heat production.

In the second experiment, the researchers treated mice with the anti-PTHrP antibody until they observed severe cachexia in control animals. The antibody significantly preserved muscle mass, which was evident by improved grip strength and in situ muscle contraction.

“You would have expected, based on our first experiments in cell culture, that blocking PTHrP in the mice would reduce browning of the fat,” said study author Bruce Spiegelman, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“But we were surprised that it also affected the loss of muscle mass and improved health.”

Additional experiments, in which the researchers injected PTHrP into healthy and tumor-bearing mice, suggested that PTHrP alone doesn’t directly cause muscle wasting. But blocking the protein’s activity still prevents cachexia.

Thus, the role of PTHrP “is definitely not the whole answer” to the riddle of cachexia, Dr Spiegelman noted. Furthermore, it may turn out that the PTHrP mechanism is responsible for cachexia in only a subset of cancer patients.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 47 cachexic patients with lung or colon cancer. And they found increased levels of PTHrP in 17 of the patients. Those patients had significantly lower lean body mass and were producing more heat energy at rest than the other patients in the group.

Dr Spiegelman noted that, before they test the anti-PTHrP antibody in clinical trials, clinicians would likely want to determine if the protein is elevated in certain cancers and determine which patients would be good candidates for the treatment. ![]()

Preclinical research raises the prospect of more effective treatments for cachexia, a profound wasting of fat and muscle that can increase the risk of death in cancer patients.

In mouse models, an antibody effectively improved or prevented symptoms of cachexia.

The antibody inhibited the effects of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), which is released from many types of cancer cells.

The researchers said their findings, published in Nature, are the first to explain in detail how PTHrP from tumors switches on a thermogenic process in fatty tissues, resulting in unhealthy weight loss.

The team carried out 2 experiments using mice that developed lung tumors and cachexia. In the first, a polyclonal antibody that specifically neutralizes PTHrP prevented cachexia almost completely, while untreated animals became mildly cachexic.

Anti-PTHrP treatment prevented the shrinkage of fat droplets. It blocked thermogenic gene expression in epididymal white adipose tissue, interscapular brown adipose tissue, and inguinal white adipose tissue, which suggests thermogenesis has a causal role in fat wasting.

Treatment with the anti-PTHrP antibody also lowered oxygen consumption in the mice, increased their physical activity, and reduced their heat production.

In the second experiment, the researchers treated mice with the anti-PTHrP antibody until they observed severe cachexia in control animals. The antibody significantly preserved muscle mass, which was evident by improved grip strength and in situ muscle contraction.

“You would have expected, based on our first experiments in cell culture, that blocking PTHrP in the mice would reduce browning of the fat,” said study author Bruce Spiegelman, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“But we were surprised that it also affected the loss of muscle mass and improved health.”

Additional experiments, in which the researchers injected PTHrP into healthy and tumor-bearing mice, suggested that PTHrP alone doesn’t directly cause muscle wasting. But blocking the protein’s activity still prevents cachexia.

Thus, the role of PTHrP “is definitely not the whole answer” to the riddle of cachexia, Dr Spiegelman noted. Furthermore, it may turn out that the PTHrP mechanism is responsible for cachexia in only a subset of cancer patients.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 47 cachexic patients with lung or colon cancer. And they found increased levels of PTHrP in 17 of the patients. Those patients had significantly lower lean body mass and were producing more heat energy at rest than the other patients in the group.

Dr Spiegelman noted that, before they test the anti-PTHrP antibody in clinical trials, clinicians would likely want to determine if the protein is elevated in certain cancers and determine which patients would be good candidates for the treatment. ![]()

Preclinical research raises the prospect of more effective treatments for cachexia, a profound wasting of fat and muscle that can increase the risk of death in cancer patients.

In mouse models, an antibody effectively improved or prevented symptoms of cachexia.

The antibody inhibited the effects of parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP), which is released from many types of cancer cells.

The researchers said their findings, published in Nature, are the first to explain in detail how PTHrP from tumors switches on a thermogenic process in fatty tissues, resulting in unhealthy weight loss.

The team carried out 2 experiments using mice that developed lung tumors and cachexia. In the first, a polyclonal antibody that specifically neutralizes PTHrP prevented cachexia almost completely, while untreated animals became mildly cachexic.

Anti-PTHrP treatment prevented the shrinkage of fat droplets. It blocked thermogenic gene expression in epididymal white adipose tissue, interscapular brown adipose tissue, and inguinal white adipose tissue, which suggests thermogenesis has a causal role in fat wasting.

Treatment with the anti-PTHrP antibody also lowered oxygen consumption in the mice, increased their physical activity, and reduced their heat production.

In the second experiment, the researchers treated mice with the anti-PTHrP antibody until they observed severe cachexia in control animals. The antibody significantly preserved muscle mass, which was evident by improved grip strength and in situ muscle contraction.

“You would have expected, based on our first experiments in cell culture, that blocking PTHrP in the mice would reduce browning of the fat,” said study author Bruce Spiegelman, PhD, of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston.

“But we were surprised that it also affected the loss of muscle mass and improved health.”

Additional experiments, in which the researchers injected PTHrP into healthy and tumor-bearing mice, suggested that PTHrP alone doesn’t directly cause muscle wasting. But blocking the protein’s activity still prevents cachexia.

Thus, the role of PTHrP “is definitely not the whole answer” to the riddle of cachexia, Dr Spiegelman noted. Furthermore, it may turn out that the PTHrP mechanism is responsible for cachexia in only a subset of cancer patients.

The researchers analyzed blood samples from 47 cachexic patients with lung or colon cancer. And they found increased levels of PTHrP in 17 of the patients. Those patients had significantly lower lean body mass and were producing more heat energy at rest than the other patients in the group.

Dr Spiegelman noted that, before they test the anti-PTHrP antibody in clinical trials, clinicians would likely want to determine if the protein is elevated in certain cancers and determine which patients would be good candidates for the treatment. ![]()

HSC engraftment across the species barrier

Scientists say they’ve generated a mouse model that supports the transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), despite the species barrier and without the need for irradiation.

The group used a mutation of the Kit receptor in the mouse stem cells to facilitate the engraftment of human cells.

In this model, human HSCs can expand and differentiate into all blood cell types without any additional treatment.

Even cells of the innate immune system that are not typically found in “humanized” mice were efficiently generated in this mouse.

Furthermore, the stem cells can be maintained in the mouse over a longer period of time.

The researchers reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“Our goal was to develop an optimal model for the transplantation and study of human blood stem cells,” said study author Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universität Dresden in Germany.

To achieve optimal stem cell engraftment, she and her colleagues introduced a naturally occurring mutation of the Kit receptor into mice lacking a functional immune system.

In this way, the team circumvented the 2 major obstacles of HSC transplantation: the rejection by the recipient’s immune system and the absence of free niche space for the incoming donor stem cells in the recipient’s bone marrow.

The Kit mutation in the new mouse model impairs the recipient’s stem cell compartment in such a way that the endogenous HSCs can be easily replaced by human donor stem cells with a functional Kit receptor.

The researchers said this replacement works so efficiently that irradiation can be completely omitted, allowing the study of human blood development in a physiological setting. The model can now be used to study diseases of the human blood and immune system or to test new treatment options.

The results of this research also show that the Kit receptor is important for the function of human HSCs, notably in a transplant setting. The researchers said future studies will focus on using this knowledge to improve conditioning therapy for patients undergoing HSC transplant. ![]()

Scientists say they’ve generated a mouse model that supports the transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), despite the species barrier and without the need for irradiation.

The group used a mutation of the Kit receptor in the mouse stem cells to facilitate the engraftment of human cells.

In this model, human HSCs can expand and differentiate into all blood cell types without any additional treatment.

Even cells of the innate immune system that are not typically found in “humanized” mice were efficiently generated in this mouse.

Furthermore, the stem cells can be maintained in the mouse over a longer period of time.

The researchers reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“Our goal was to develop an optimal model for the transplantation and study of human blood stem cells,” said study author Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universität Dresden in Germany.

To achieve optimal stem cell engraftment, she and her colleagues introduced a naturally occurring mutation of the Kit receptor into mice lacking a functional immune system.

In this way, the team circumvented the 2 major obstacles of HSC transplantation: the rejection by the recipient’s immune system and the absence of free niche space for the incoming donor stem cells in the recipient’s bone marrow.

The Kit mutation in the new mouse model impairs the recipient’s stem cell compartment in such a way that the endogenous HSCs can be easily replaced by human donor stem cells with a functional Kit receptor.

The researchers said this replacement works so efficiently that irradiation can be completely omitted, allowing the study of human blood development in a physiological setting. The model can now be used to study diseases of the human blood and immune system or to test new treatment options.

The results of this research also show that the Kit receptor is important for the function of human HSCs, notably in a transplant setting. The researchers said future studies will focus on using this knowledge to improve conditioning therapy for patients undergoing HSC transplant. ![]()

Scientists say they’ve generated a mouse model that supports the transplantation of human hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), despite the species barrier and without the need for irradiation.

The group used a mutation of the Kit receptor in the mouse stem cells to facilitate the engraftment of human cells.

In this model, human HSCs can expand and differentiate into all blood cell types without any additional treatment.

Even cells of the innate immune system that are not typically found in “humanized” mice were efficiently generated in this mouse.

Furthermore, the stem cells can be maintained in the mouse over a longer period of time.

The researchers reported these results in Cell Stem Cell.

“Our goal was to develop an optimal model for the transplantation and study of human blood stem cells,” said study author Claudia Waskow, PhD, of Technische Universität Dresden in Germany.

To achieve optimal stem cell engraftment, she and her colleagues introduced a naturally occurring mutation of the Kit receptor into mice lacking a functional immune system.

In this way, the team circumvented the 2 major obstacles of HSC transplantation: the rejection by the recipient’s immune system and the absence of free niche space for the incoming donor stem cells in the recipient’s bone marrow.

The Kit mutation in the new mouse model impairs the recipient’s stem cell compartment in such a way that the endogenous HSCs can be easily replaced by human donor stem cells with a functional Kit receptor.

The researchers said this replacement works so efficiently that irradiation can be completely omitted, allowing the study of human blood development in a physiological setting. The model can now be used to study diseases of the human blood and immune system or to test new treatment options.

The results of this research also show that the Kit receptor is important for the function of human HSCs, notably in a transplant setting. The researchers said future studies will focus on using this knowledge to improve conditioning therapy for patients undergoing HSC transplant. ![]()

RBC Transfusion Reduction

Historically, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions have been viewed as safe and effective means of treating anemia and improving oxygen delivery to tissues. Beginning in the early 1980s, primarily driven by concerns related to the risks of transfusion‐related infection, transfusion practice began to come under scrutiny.

Numerous studies over the past 2 decades have failed to demonstrate a benefit of RBC transfusion in many of the clinical situations in which RBC transfusions are routinely given, and many of these studies have in fact shown that RBC transfusion may lead to worse clinical outcomes in some patients.[1, 2] The few available large, randomized clinical trials and prospective observational studies that have assessed the effectiveness of allogeneic RBC transfusion have demonstrated that a more restrictive approach to RBC transfusion results in at least equivalent patient outcomes as compared to a liberal approach, and may in fact reduce morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2]

Over the last decade, RBC transfusion best‐practice guidelines have been developed by a number of professional societies,[3] addressing RBC transfusion practice in specific patient populations including critical care as well as more general hospitalized populations. These guidelines are generally consistent, strongly recommending a restrictive RBC transfusion approach in most clinical populations. However, despite the general consistency of the guidelines and the lack of evidence for the efficacy of RBC transfusion, there still remains significant variability in clinical RBC transfusion practice.[4, 5]

The difficulty in getting physicians to follow clinical guidelines in general has been well described.[6] Over the last 2 decades there have been reports of a variety of interventions directed toward improving RBC transfusion practice either in specific care units (eg, intensive care units [ICUs]) or institution wide.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These initiatives have had varying degrees of success and have employed strategies that have included clinical guidelines, education, audit/feedback, and most recently computer order entry and decision support. We report on the effectiveness of an institution‐wide intervention to align RBC transfusion practice with best‐practice clinical guidelines. Our approach included institutional endorsement of a RBC transfusion guideline coupled with an ongoing education program and RBC transfusion order set.

METHODS

Study Setting

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) is a tertiary care university teaching hospital with a total of 437 patient beds. UAMS is a level 1 trauma center and has 52 ICU beds. The study took place between July 2012 and December 2013. At the time of study initiation, there was no institutional RBC transfusion protocol or guideline.

Study Design

In June 2012, a program was initiated to align RBC transfusion practice at UAMS with best‐practice RBC transfusion guidelines. This initiative consisted of several components: a series of educational programs, followed by hospital medical board approval of an intuitional RBC transfusion guideline, and initiation of an RBC transfusion order set of approved RBC transfusion guideline recommendations (Table 1).

| RBC Transfusion Guideline | |

|---|---|

| |

| PURPOSE: Unnecessary blood transfusions increase healthcare costs and expose patients to potential infectious and noninfectious risks. The purpose of this clinical practice guideline is to establish an evidence‐based approach to the transfusion of RBCs in hospitalized patients at UAMS. | |

| GUIDELINE: In order to avoid the potential risks and increased costs associated with unnecessary blood transfusions, the medical staff of UAMS will adhere to a restrictive transfusion strategy in which: | |

| (I) RBC transfusion should be considered unnecessary for hospitalized, hemodynamically stable patients unless the hemoglobin concentration is <78 g/dL. | |

| (II) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients who have evidence of acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock. | |

| (III) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients with acute MI or unstable myocardial ischemia if the hemoglobin concentration is 8 g/dL. | |

| (IV) The use of the hemoglobin concentration alone as a trigger for RBC transfusion should be avoided. The decision to order an RBC transfusion should also consider a patient's intravascular volume status, evidence of shock, duration and extent of anemia, and cardiopulmonary physiologic parameters as well as other symptomatology. | |

| (V) In the absence of acute hemorrhage, an RBC transfusion should be ordered and administered as single units. | |

| (VI) It is the physician's responsibility to weigh the risks and benefits of an RBC transfusion for a particular patient based on their medical condition. As such, it is recognized that there will be situations in which an RBC transfusion is appropriate outside of the guidelines put forth in this document. In these instances, the physician should document in the medical record his/her rationale for the RBC transfusion. | |

| RBC Transfusion Order Form | |

| The following are RBC transfusion indications consistent with UAMS‐approved guidelines (check 1): | |

| Acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock | Yes |

| Hgb <78 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute MI, Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute coronary syndrome Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| If the RBC transfusion is for an indication other than those listed above, please note the indication and attending physician in the space provided. | |

| Other indications/attending physician | Free text of other indications. |

| In the absence of acute hemorrhage or a hemoglobin concentration <6.5 g/dL, it is recommended that RBCs be ordered as single units. | |

The educational program included grand rounds presentations for all major clinical departments (internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, geriatrics, anesthesiology), presentations to high‐volume transfusing services (hematology, vascular surgery, cardiac surgery), presentations to hightransfusion‐volume nursing units (eg, medical and surgical ICUs, intermediate care unit, hematology), and scheduled and ad hoc resident educational programs. Educational sessions were repeated over the 18 months of the study and were presented by a clinical content expert.

A UAMS‐specific transfusion guideline was developed based on published best‐practice guidelines.[15, 16] The UAMS medical board approved this guideline in November 2012 (Table 1). The guidelines were disseminated to the entire medical staff in December 2012 via email communication from the hospital's chief medical officer. Membership of the medical board included clinical leadership of the medical center (ie, department chairs) as well as ad hoc members from the hospital administrative leadership.

An RBC transfusion order form that included the guideline recommendations was implemented in the electronic medical record (Sunrise Enterprise 5.5; Eclipsys Corp., Atlanta, GA) in March 2013. There was no hard stop for an RBC transfusion order that was outside of the guideline recommendations; however, for documentation, the ordering physician was required to note the indication and the supervising attending physician for these out‐of‐guideline RBC transfusions. RBC transfusion orders are entered in an electronic medical record. There was no alert triggered by an RBC transfusion order outside of the RBC transfusion guideline.

Outcomes

The number of RBC units transfused during the baseline period of January 2011 through June 2012 was compared with RBC units transfused July 2012 through December 2013. The latter period was further divided into the time period July 2012 through December 2012, during which the education program was initiated (education) as well as the time period January 2013 through December 2013 following the transfusion guideline approval and the initiation of the transfusion order set (decision support). All adult inpatient RBC units transfused, excluding RBC units transfused in the operating room and emergency room, were included in the analysis. RBC transfusions per month were normalized to RBC transfusions per 28 days. RBC transfusions were also calculated as RBC units per adult hospital admission and RBC units per 100 patient‐days.

Hospital mortality is presented as mortality index (observed/predicted mortality). The mean weighted diagnosis‐related group (DRG) was calculated using the monthly average of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)‐derived relative weighted DRGs.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as meanstandard deviation. Comparisons were by Student t test or analysis of variance as appropriate. GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis, and Minitab (Minitab Inc., State College, PA) was used for control graphs.

RESULTS

There were 28,393 adult admissions (excluding psychiatry) during the baseline period (January 2011June 2012) and 35,743 (12,353 education, 23,390 decision support) adult admissions during the study period (July 2012December 2013). The patient demographics for the 3 time periods were comparable (Table 2).

| Baseline | Education | Decision Support | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Total patients | 28,393 | 12,353 | 23,390 |

| Age, mean, y* | 48.20.6 | 480.1 | 480.5 |

| Gender, % female | 56 | 57 | 58 |

| Race, % non‐Caucasian | 63 | 61 | 61 |

| Weighted DRG | 1.60 | 1.59 | 1.59 |

| MDC, % | |||

| Nervous system | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Circulatory system | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Digestive system | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Respiratory system | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Kidney and urinary tract | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Hepatobiliary system | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Infectious and parasitic | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Endocrine, metabolic | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Blood, immunologic | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Myeloproliferative | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Multiple significant trauma | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 20 | 20 | 22 |

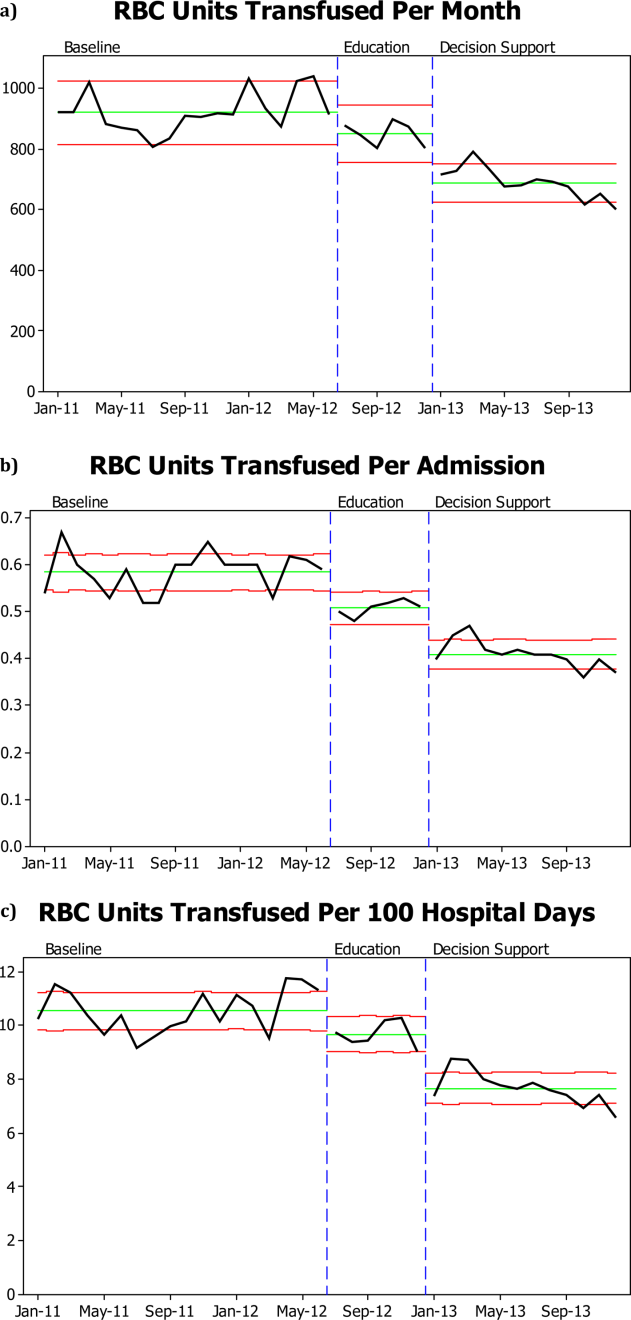

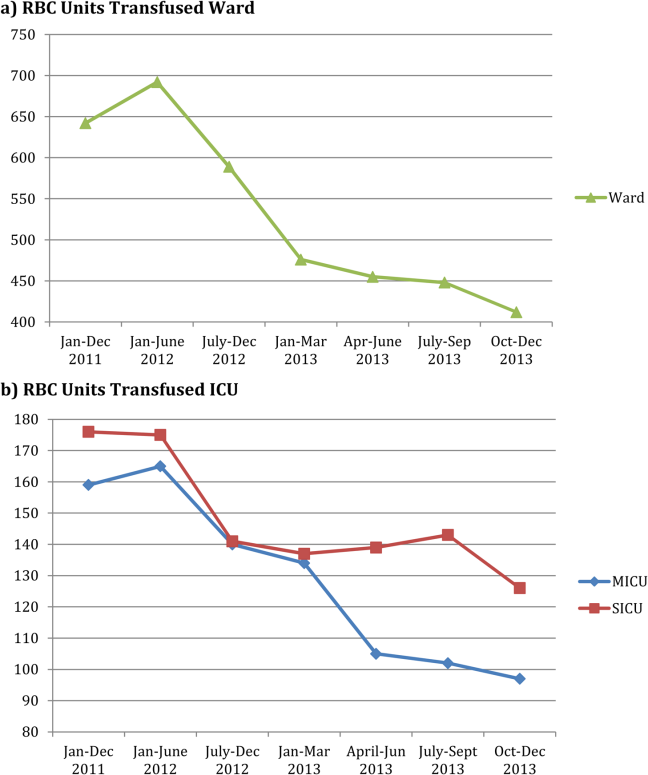

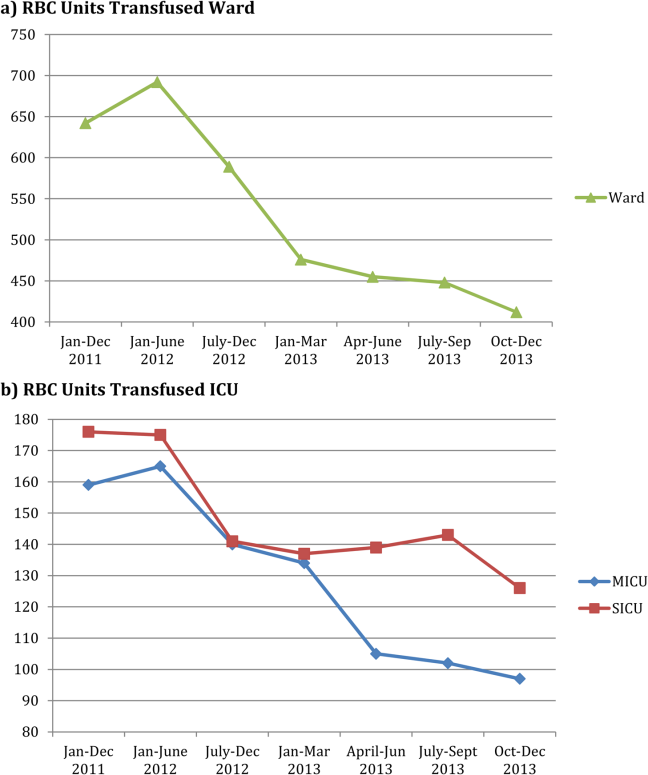

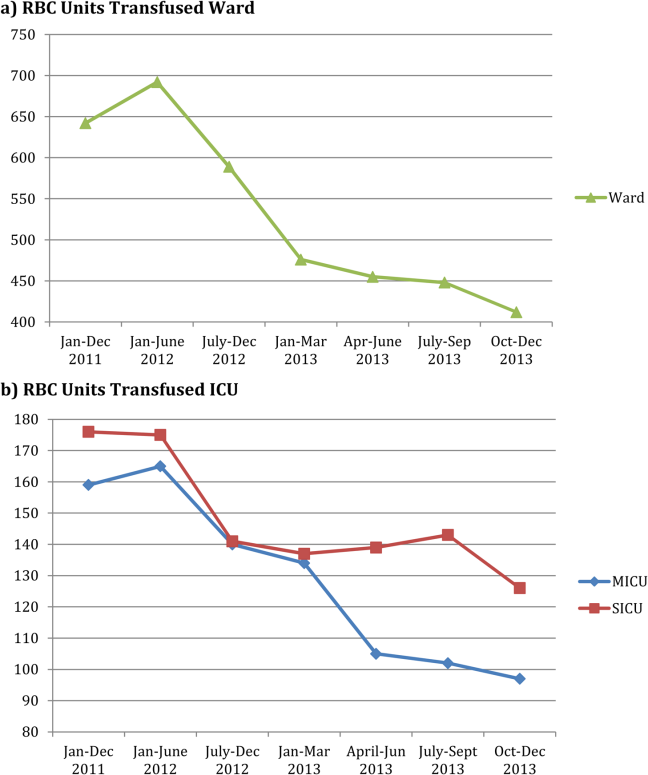

There was a significant decrease in the mean number of RBC units transfused as a result of the RBC transfusion program (Figure 1A). As compared to the baseline period, the mean number of RBC units transfused fell immediately during the 6 months following the initiation of the education program (92368 to 85240, P=0.02), and further still during the subsequent 12 months following the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the UAMS medical board and initiation of the RBC transfusion order set (to 69052, P<0.0001). These results do not reflect a change in the number of hospital admissions or length of stay; results are comparable if calculated based on RBC units transfused per patient admission or RBC per 100 patient‐days (Figure 1B,C). Overall, there was a 29% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per hospital admission (0.580.040.410.03, P=0.0001) and a 27% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per 100 hospital‐days (10.560.87.680.63, P=0.0001).

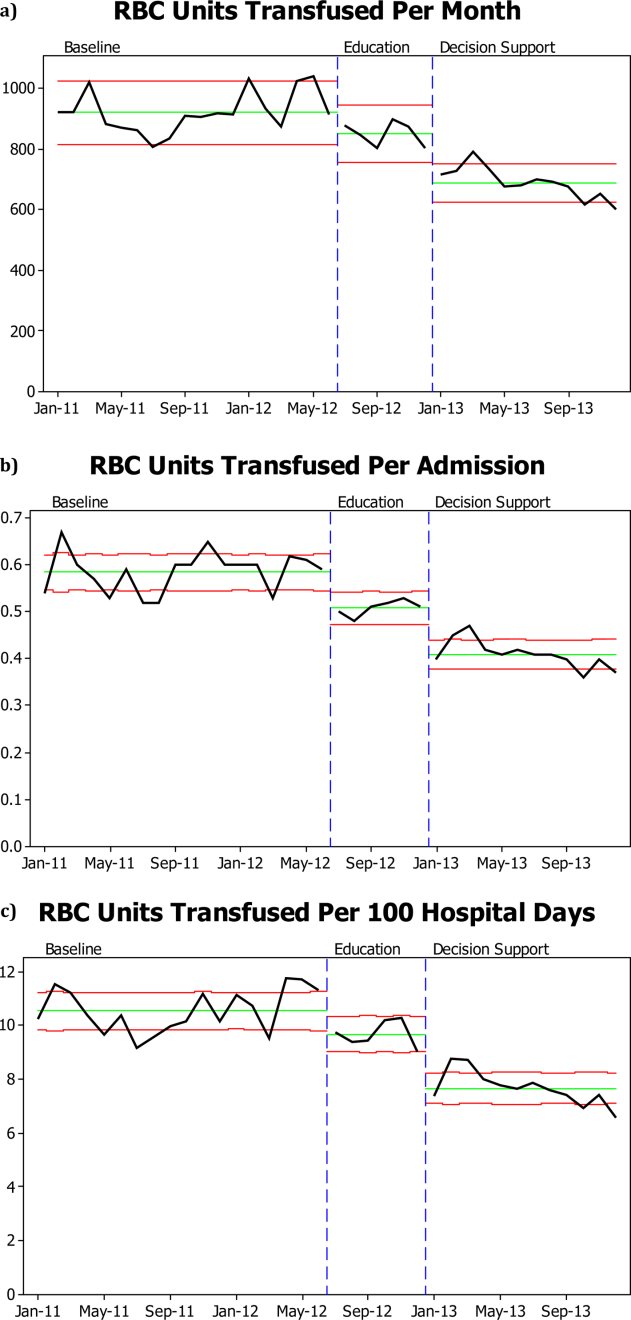

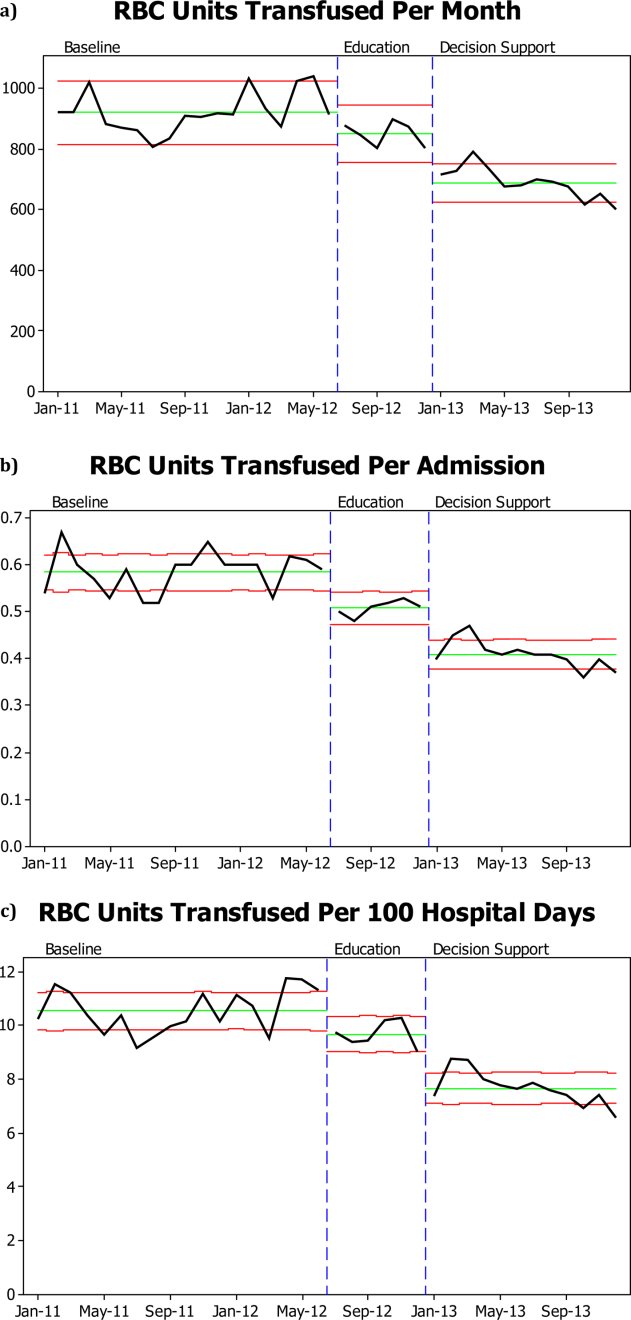

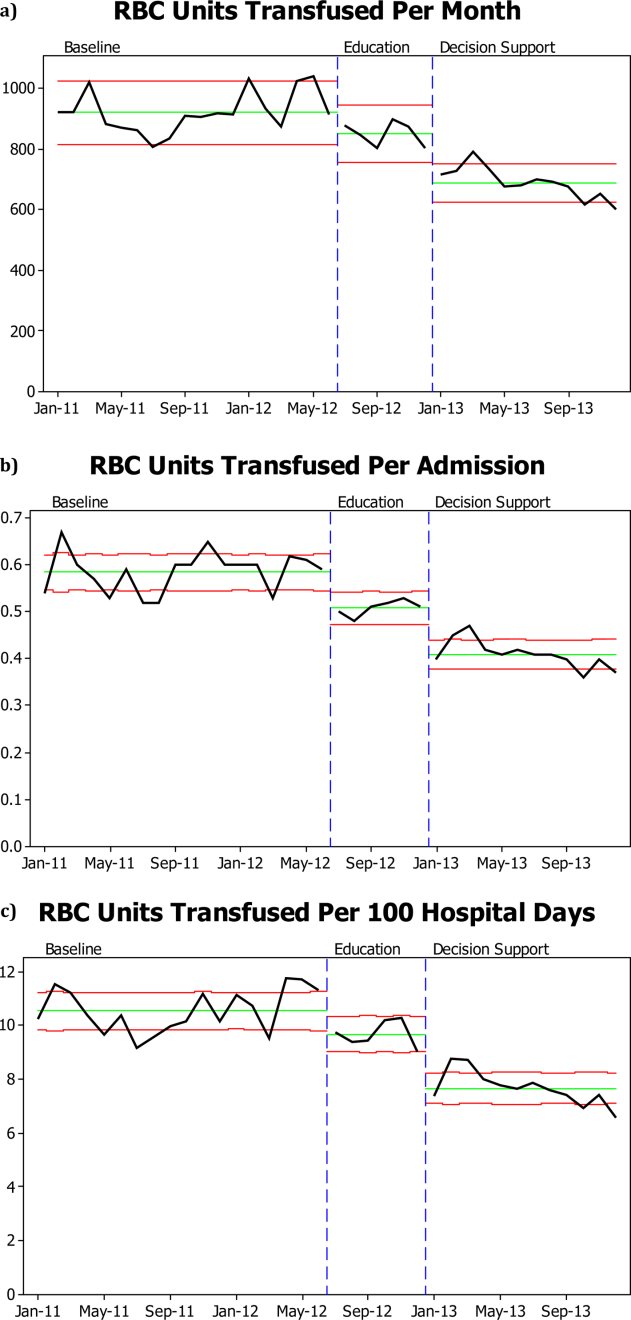

RBC transfusion reduction was observed in both the medical and surgical ICUs (Figure 2B) as well as the general patient wards (Figure 2A). The trends noted above were similar in the medical ICU and general patient wards; however, in the surgical ICU, the RBC transfusion rate fell on initiation of the education program and remained stable at this lower rate for the subsequent 18 months, with no further decrease following RBC transfusion guideline approval and initiation of the RBC order set.

There was no significant difference in hospital mortality observed pre‐ versus post‐RBC transfusion program (mortality index 0.890.05 vs 0.840.04, P=0.13).

DISCUSSION

We were able to demonstrate a 25% reduction in total RBC units transfused with an ongoing education program coupled with an institutional adoption of an RBC transfusion guideline that was incorporated into an RBC transfusion order set. Our program was novel in that the RBC transfusion guideline was approved by the hospital medical board as an institutional practice guideline. Importantly, the RBC transfusion reduction has been maintained over a 18‐month period. The program was instituted in stages: educational program, followed by guideline approval by the hospital medical board, and the initiation of an RBC transfusion order set. At each stage we observed an additive increase in RBC transfusion reduction, with the largest reduction following guideline approval and initiation of the order set.

The pattern of RBC transfusion reduction was observed in all areas of the hospital with the exception of the surgical ICU, where transfusion practice remained stable after the initial decrease in RBC transfusions following initiation of the education program. That RBC transfusion practice on the general surgical wards mirrored practice in other areas of the hospital suggests that the difference seen in the surgical ICU reflects factors unique to that specific area rather than the general approach of surgeons to RBC transfusion.

Despite the substantial data now available regarding RBC transfusion risks and the proliferation of RBC transfusion practice guidelines, wide variation in clinical practice still exists.[4, 5] The delay for evidence from clinical studies to be incorporated into clinical practice can be considerable. Balas and Boren[17] have estimated that it may take over 15 years from publication of a landmark study for the results to reach a 50% utilization rate in clinical practice. The barriers to guideline adherence have been described, including lack of familiarity, lack of agreement, and external factors.[6] Overcoming these barriers involve approaches toward knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

There have been a number of approaches to changing RBC transfusion practice over the last 2 decades.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These interventions have all achieved varying degrees of success. Most have involved some combination of education, practice guideline, and audit/feedback. More recently, technology has allowed computer‐assisted order entry and feedback. Goodnough et al.,[7] employing real‐time clinical decision support and best‐practice alerts, were able to achieve sustained adherence to clinical guidelines and a 24% reduction in RBC units transfused. Other recent reports have shown improvement in RBC transfusion practices comparable to what we observed with programs including audit/feedback and educational efforts.[13, 14]

Our approach to RBC transfusion practice was relatively simple, involving education followed by institutional adoption of a best‐practice guideline and simple RBC transfusion order form. We were able to begin to change RBC transfusion practice with the initiation of an education program; however, there was a more marked and persistent decrease in RBC transfusions following the adoption of the institution's RBC transfusion guideline and RBC transfusion order set. Although education alone is often ineffective in causing sustained change in behavior, a key aspect of our program was the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the hospital medical board. The approval by the hospital medical board, made up in part by the clinical leadership, was instrumental in changing the transfusion culture, or beliefs, in the institution. The consistency of practice seen within the time periods both before and after our intervention suggest a given set of beliefs driving RBC transfusion in each time period. Further supporting this view is the consistency of RBC transfusion practice change throughout the institution, and the fact that patient volumes and severity of illness were comparable pre‐ and postintervention. It is difficult to know which elements of the program were most important. It is likely that optimal transfusion practices promoted by the education program were reinforced by the guideline, which were further reinforced by the order set.

Given the known risks of RBC transfusion and the data supporting a restrictive approach to RBC transfusion practice, improved patient safety by aligning RBC transfusion with best‐practice guidelines was the primary goal of our RBC transfusion program.[1, 2] Although we were not able to look at specific complications such as infection rate, there was no change in overall hospital mortality. The total RBC units transfused at our institution fell by almost 30%. We estimate that in the 18 months following initiation of our program we saved approximately 3200 RBC units as compared with the number of RBC units that would have been transfused based on the transfusion rate prior to the initiation of our educational program. This preserves a scarce resource, RBCs, as a well as reduces cost. The cost of an RBC transfusion involves both the direct cost of the RBC unit as well as the cost of activities surrounding an RBC transfusion. Shander et al.,[18] using an activities‐based costing model, have estimated the direct and indirect cost of an RBC transfusion as between $522 and $1183 (mean $761). Over the last 18 months we have achieved a direct savings of $704,000 for purchase of RBC units and, using the low estimate based on the activities‐based costing model, a total savings of at least $1.7 million.

This study is limited by the fact that it reflects a single‐institution experience. Although we cannot exclude other factors contributing to the decrease in RBC transfusion, the pattern of response suggests that the RBC transfusion program was largely responsible for the results observed. Further, patient volumes at our institution have remained constant, as have surgical volumes. RBC transfusions are reduced comparably whether analyzed as total units transfused, units transfused per admission, or units transfused per 100 patient‐days. The complexity of care also limits our ability to draw any conclusions regarding the impact of RBC transfusion reduction on patient outcome. We also do not know how consistent RBC transfusion practice prior to our program was with our guideline; however, the significant decline in RBC units transfused following our intervention suggests that there was a discrepancy in RBC transfusion practice preintervention.

In conclusion, an education program coupled with institutional adoption of a best‐practice RBC transfusion guideline and a RBC transfusion order set resulted in consistent reduction in RBC units transfused. The improvement in RBC transfusion practice was additive with implementation of each intervention. RBC transfusion practice was changed in all areas of the hospital and resulted in less exposure of patients to RBC transfusion risks, preserved a scarce resource, and was a direct cost savings.

- , , . Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD002042.

- , . Efficacy of RBC transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2667–2674.

- , , , , . A new perspective on best transfusion practice. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:193–202.

- , , , et al. Variation in use of blood transfusion in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1568–1575.

- , , , et al. RBC transfusion practices among critically ill patients: has evidence changed practice? Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2344–2353.

- , , , et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465.

- , , , , , . Improved blood utilization using real‐time clinical decision support. Transfusion. 2014;54:1358–1365.

- , , , , , . Computerized physician order entry with decision support decreases blood transfusion in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1112–e1119.

- , , , et al. Reducing the amount of blood transfused. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:845–852.

- , , , et al. Assessment of education and computerized decision support interventions for improving transfusion practice. Transfusion. 2007;47:228–239.

- , , , , Transfusion insurgency: practice change through education and evidence‐based recommendations. Am J Surg. 2009;197:279–283.

- , , , et al. Evidence‐based red cell transfusion in the critically ill: quality improvement using computerized physician order entry. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1892–1897.

- , , . The addition of decision support into computerize physician order entry reduces red blood cell transfusion resource utilization in the intensive care unit. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:631–633.

- , , , et al. How we closed the gap between red blood cell utilization and whole blood collections in our institution. Transfusion. 2012;52:1857–1867.

- , , , et al. American College of Critical Care and Eastern Association of Trauma. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion practice in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3124–3157.

- , , , et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline of the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49–58.

- , . Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray AT, eds. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient‐Centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft; 2000:65–70.

- , , , et al. Activity‐based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion. 2010;50:753–764.

Historically, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions have been viewed as safe and effective means of treating anemia and improving oxygen delivery to tissues. Beginning in the early 1980s, primarily driven by concerns related to the risks of transfusion‐related infection, transfusion practice began to come under scrutiny.

Numerous studies over the past 2 decades have failed to demonstrate a benefit of RBC transfusion in many of the clinical situations in which RBC transfusions are routinely given, and many of these studies have in fact shown that RBC transfusion may lead to worse clinical outcomes in some patients.[1, 2] The few available large, randomized clinical trials and prospective observational studies that have assessed the effectiveness of allogeneic RBC transfusion have demonstrated that a more restrictive approach to RBC transfusion results in at least equivalent patient outcomes as compared to a liberal approach, and may in fact reduce morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2]

Over the last decade, RBC transfusion best‐practice guidelines have been developed by a number of professional societies,[3] addressing RBC transfusion practice in specific patient populations including critical care as well as more general hospitalized populations. These guidelines are generally consistent, strongly recommending a restrictive RBC transfusion approach in most clinical populations. However, despite the general consistency of the guidelines and the lack of evidence for the efficacy of RBC transfusion, there still remains significant variability in clinical RBC transfusion practice.[4, 5]

The difficulty in getting physicians to follow clinical guidelines in general has been well described.[6] Over the last 2 decades there have been reports of a variety of interventions directed toward improving RBC transfusion practice either in specific care units (eg, intensive care units [ICUs]) or institution wide.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These initiatives have had varying degrees of success and have employed strategies that have included clinical guidelines, education, audit/feedback, and most recently computer order entry and decision support. We report on the effectiveness of an institution‐wide intervention to align RBC transfusion practice with best‐practice clinical guidelines. Our approach included institutional endorsement of a RBC transfusion guideline coupled with an ongoing education program and RBC transfusion order set.

METHODS

Study Setting

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) is a tertiary care university teaching hospital with a total of 437 patient beds. UAMS is a level 1 trauma center and has 52 ICU beds. The study took place between July 2012 and December 2013. At the time of study initiation, there was no institutional RBC transfusion protocol or guideline.

Study Design

In June 2012, a program was initiated to align RBC transfusion practice at UAMS with best‐practice RBC transfusion guidelines. This initiative consisted of several components: a series of educational programs, followed by hospital medical board approval of an intuitional RBC transfusion guideline, and initiation of an RBC transfusion order set of approved RBC transfusion guideline recommendations (Table 1).

| RBC Transfusion Guideline | |

|---|---|

| |

| PURPOSE: Unnecessary blood transfusions increase healthcare costs and expose patients to potential infectious and noninfectious risks. The purpose of this clinical practice guideline is to establish an evidence‐based approach to the transfusion of RBCs in hospitalized patients at UAMS. | |

| GUIDELINE: In order to avoid the potential risks and increased costs associated with unnecessary blood transfusions, the medical staff of UAMS will adhere to a restrictive transfusion strategy in which: | |

| (I) RBC transfusion should be considered unnecessary for hospitalized, hemodynamically stable patients unless the hemoglobin concentration is <78 g/dL. | |

| (II) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients who have evidence of acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock. | |

| (III) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients with acute MI or unstable myocardial ischemia if the hemoglobin concentration is 8 g/dL. | |

| (IV) The use of the hemoglobin concentration alone as a trigger for RBC transfusion should be avoided. The decision to order an RBC transfusion should also consider a patient's intravascular volume status, evidence of shock, duration and extent of anemia, and cardiopulmonary physiologic parameters as well as other symptomatology. | |

| (V) In the absence of acute hemorrhage, an RBC transfusion should be ordered and administered as single units. | |

| (VI) It is the physician's responsibility to weigh the risks and benefits of an RBC transfusion for a particular patient based on their medical condition. As such, it is recognized that there will be situations in which an RBC transfusion is appropriate outside of the guidelines put forth in this document. In these instances, the physician should document in the medical record his/her rationale for the RBC transfusion. | |

| RBC Transfusion Order Form | |

| The following are RBC transfusion indications consistent with UAMS‐approved guidelines (check 1): | |

| Acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock | Yes |

| Hgb <78 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute MI, Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute coronary syndrome Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| If the RBC transfusion is for an indication other than those listed above, please note the indication and attending physician in the space provided. | |

| Other indications/attending physician | Free text of other indications. |

| In the absence of acute hemorrhage or a hemoglobin concentration <6.5 g/dL, it is recommended that RBCs be ordered as single units. | |

The educational program included grand rounds presentations for all major clinical departments (internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, geriatrics, anesthesiology), presentations to high‐volume transfusing services (hematology, vascular surgery, cardiac surgery), presentations to hightransfusion‐volume nursing units (eg, medical and surgical ICUs, intermediate care unit, hematology), and scheduled and ad hoc resident educational programs. Educational sessions were repeated over the 18 months of the study and were presented by a clinical content expert.

A UAMS‐specific transfusion guideline was developed based on published best‐practice guidelines.[15, 16] The UAMS medical board approved this guideline in November 2012 (Table 1). The guidelines were disseminated to the entire medical staff in December 2012 via email communication from the hospital's chief medical officer. Membership of the medical board included clinical leadership of the medical center (ie, department chairs) as well as ad hoc members from the hospital administrative leadership.

An RBC transfusion order form that included the guideline recommendations was implemented in the electronic medical record (Sunrise Enterprise 5.5; Eclipsys Corp., Atlanta, GA) in March 2013. There was no hard stop for an RBC transfusion order that was outside of the guideline recommendations; however, for documentation, the ordering physician was required to note the indication and the supervising attending physician for these out‐of‐guideline RBC transfusions. RBC transfusion orders are entered in an electronic medical record. There was no alert triggered by an RBC transfusion order outside of the RBC transfusion guideline.

Outcomes

The number of RBC units transfused during the baseline period of January 2011 through June 2012 was compared with RBC units transfused July 2012 through December 2013. The latter period was further divided into the time period July 2012 through December 2012, during which the education program was initiated (education) as well as the time period January 2013 through December 2013 following the transfusion guideline approval and the initiation of the transfusion order set (decision support). All adult inpatient RBC units transfused, excluding RBC units transfused in the operating room and emergency room, were included in the analysis. RBC transfusions per month were normalized to RBC transfusions per 28 days. RBC transfusions were also calculated as RBC units per adult hospital admission and RBC units per 100 patient‐days.

Hospital mortality is presented as mortality index (observed/predicted mortality). The mean weighted diagnosis‐related group (DRG) was calculated using the monthly average of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)‐derived relative weighted DRGs.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as meanstandard deviation. Comparisons were by Student t test or analysis of variance as appropriate. GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis, and Minitab (Minitab Inc., State College, PA) was used for control graphs.

RESULTS

There were 28,393 adult admissions (excluding psychiatry) during the baseline period (January 2011June 2012) and 35,743 (12,353 education, 23,390 decision support) adult admissions during the study period (July 2012December 2013). The patient demographics for the 3 time periods were comparable (Table 2).

| Baseline | Education | Decision Support | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Total patients | 28,393 | 12,353 | 23,390 |

| Age, mean, y* | 48.20.6 | 480.1 | 480.5 |

| Gender, % female | 56 | 57 | 58 |

| Race, % non‐Caucasian | 63 | 61 | 61 |

| Weighted DRG | 1.60 | 1.59 | 1.59 |

| MDC, % | |||

| Nervous system | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Circulatory system | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Digestive system | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Respiratory system | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Kidney and urinary tract | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Hepatobiliary system | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Infectious and parasitic | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Endocrine, metabolic | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Blood, immunologic | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Myeloproliferative | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Multiple significant trauma | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 20 | 20 | 22 |

There was a significant decrease in the mean number of RBC units transfused as a result of the RBC transfusion program (Figure 1A). As compared to the baseline period, the mean number of RBC units transfused fell immediately during the 6 months following the initiation of the education program (92368 to 85240, P=0.02), and further still during the subsequent 12 months following the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the UAMS medical board and initiation of the RBC transfusion order set (to 69052, P<0.0001). These results do not reflect a change in the number of hospital admissions or length of stay; results are comparable if calculated based on RBC units transfused per patient admission or RBC per 100 patient‐days (Figure 1B,C). Overall, there was a 29% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per hospital admission (0.580.040.410.03, P=0.0001) and a 27% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per 100 hospital‐days (10.560.87.680.63, P=0.0001).

RBC transfusion reduction was observed in both the medical and surgical ICUs (Figure 2B) as well as the general patient wards (Figure 2A). The trends noted above were similar in the medical ICU and general patient wards; however, in the surgical ICU, the RBC transfusion rate fell on initiation of the education program and remained stable at this lower rate for the subsequent 18 months, with no further decrease following RBC transfusion guideline approval and initiation of the RBC order set.

There was no significant difference in hospital mortality observed pre‐ versus post‐RBC transfusion program (mortality index 0.890.05 vs 0.840.04, P=0.13).

DISCUSSION

We were able to demonstrate a 25% reduction in total RBC units transfused with an ongoing education program coupled with an institutional adoption of an RBC transfusion guideline that was incorporated into an RBC transfusion order set. Our program was novel in that the RBC transfusion guideline was approved by the hospital medical board as an institutional practice guideline. Importantly, the RBC transfusion reduction has been maintained over a 18‐month period. The program was instituted in stages: educational program, followed by guideline approval by the hospital medical board, and the initiation of an RBC transfusion order set. At each stage we observed an additive increase in RBC transfusion reduction, with the largest reduction following guideline approval and initiation of the order set.

The pattern of RBC transfusion reduction was observed in all areas of the hospital with the exception of the surgical ICU, where transfusion practice remained stable after the initial decrease in RBC transfusions following initiation of the education program. That RBC transfusion practice on the general surgical wards mirrored practice in other areas of the hospital suggests that the difference seen in the surgical ICU reflects factors unique to that specific area rather than the general approach of surgeons to RBC transfusion.

Despite the substantial data now available regarding RBC transfusion risks and the proliferation of RBC transfusion practice guidelines, wide variation in clinical practice still exists.[4, 5] The delay for evidence from clinical studies to be incorporated into clinical practice can be considerable. Balas and Boren[17] have estimated that it may take over 15 years from publication of a landmark study for the results to reach a 50% utilization rate in clinical practice. The barriers to guideline adherence have been described, including lack of familiarity, lack of agreement, and external factors.[6] Overcoming these barriers involve approaches toward knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

There have been a number of approaches to changing RBC transfusion practice over the last 2 decades.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These interventions have all achieved varying degrees of success. Most have involved some combination of education, practice guideline, and audit/feedback. More recently, technology has allowed computer‐assisted order entry and feedback. Goodnough et al.,[7] employing real‐time clinical decision support and best‐practice alerts, were able to achieve sustained adherence to clinical guidelines and a 24% reduction in RBC units transfused. Other recent reports have shown improvement in RBC transfusion practices comparable to what we observed with programs including audit/feedback and educational efforts.[13, 14]

Our approach to RBC transfusion practice was relatively simple, involving education followed by institutional adoption of a best‐practice guideline and simple RBC transfusion order form. We were able to begin to change RBC transfusion practice with the initiation of an education program; however, there was a more marked and persistent decrease in RBC transfusions following the adoption of the institution's RBC transfusion guideline and RBC transfusion order set. Although education alone is often ineffective in causing sustained change in behavior, a key aspect of our program was the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the hospital medical board. The approval by the hospital medical board, made up in part by the clinical leadership, was instrumental in changing the transfusion culture, or beliefs, in the institution. The consistency of practice seen within the time periods both before and after our intervention suggest a given set of beliefs driving RBC transfusion in each time period. Further supporting this view is the consistency of RBC transfusion practice change throughout the institution, and the fact that patient volumes and severity of illness were comparable pre‐ and postintervention. It is difficult to know which elements of the program were most important. It is likely that optimal transfusion practices promoted by the education program were reinforced by the guideline, which were further reinforced by the order set.

Given the known risks of RBC transfusion and the data supporting a restrictive approach to RBC transfusion practice, improved patient safety by aligning RBC transfusion with best‐practice guidelines was the primary goal of our RBC transfusion program.[1, 2] Although we were not able to look at specific complications such as infection rate, there was no change in overall hospital mortality. The total RBC units transfused at our institution fell by almost 30%. We estimate that in the 18 months following initiation of our program we saved approximately 3200 RBC units as compared with the number of RBC units that would have been transfused based on the transfusion rate prior to the initiation of our educational program. This preserves a scarce resource, RBCs, as a well as reduces cost. The cost of an RBC transfusion involves both the direct cost of the RBC unit as well as the cost of activities surrounding an RBC transfusion. Shander et al.,[18] using an activities‐based costing model, have estimated the direct and indirect cost of an RBC transfusion as between $522 and $1183 (mean $761). Over the last 18 months we have achieved a direct savings of $704,000 for purchase of RBC units and, using the low estimate based on the activities‐based costing model, a total savings of at least $1.7 million.

This study is limited by the fact that it reflects a single‐institution experience. Although we cannot exclude other factors contributing to the decrease in RBC transfusion, the pattern of response suggests that the RBC transfusion program was largely responsible for the results observed. Further, patient volumes at our institution have remained constant, as have surgical volumes. RBC transfusions are reduced comparably whether analyzed as total units transfused, units transfused per admission, or units transfused per 100 patient‐days. The complexity of care also limits our ability to draw any conclusions regarding the impact of RBC transfusion reduction on patient outcome. We also do not know how consistent RBC transfusion practice prior to our program was with our guideline; however, the significant decline in RBC units transfused following our intervention suggests that there was a discrepancy in RBC transfusion practice preintervention.

In conclusion, an education program coupled with institutional adoption of a best‐practice RBC transfusion guideline and a RBC transfusion order set resulted in consistent reduction in RBC units transfused. The improvement in RBC transfusion practice was additive with implementation of each intervention. RBC transfusion practice was changed in all areas of the hospital and resulted in less exposure of patients to RBC transfusion risks, preserved a scarce resource, and was a direct cost savings.

Historically, red blood cell (RBC) transfusions have been viewed as safe and effective means of treating anemia and improving oxygen delivery to tissues. Beginning in the early 1980s, primarily driven by concerns related to the risks of transfusion‐related infection, transfusion practice began to come under scrutiny.

Numerous studies over the past 2 decades have failed to demonstrate a benefit of RBC transfusion in many of the clinical situations in which RBC transfusions are routinely given, and many of these studies have in fact shown that RBC transfusion may lead to worse clinical outcomes in some patients.[1, 2] The few available large, randomized clinical trials and prospective observational studies that have assessed the effectiveness of allogeneic RBC transfusion have demonstrated that a more restrictive approach to RBC transfusion results in at least equivalent patient outcomes as compared to a liberal approach, and may in fact reduce morbidity and mortality rates.[1, 2]

Over the last decade, RBC transfusion best‐practice guidelines have been developed by a number of professional societies,[3] addressing RBC transfusion practice in specific patient populations including critical care as well as more general hospitalized populations. These guidelines are generally consistent, strongly recommending a restrictive RBC transfusion approach in most clinical populations. However, despite the general consistency of the guidelines and the lack of evidence for the efficacy of RBC transfusion, there still remains significant variability in clinical RBC transfusion practice.[4, 5]

The difficulty in getting physicians to follow clinical guidelines in general has been well described.[6] Over the last 2 decades there have been reports of a variety of interventions directed toward improving RBC transfusion practice either in specific care units (eg, intensive care units [ICUs]) or institution wide.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These initiatives have had varying degrees of success and have employed strategies that have included clinical guidelines, education, audit/feedback, and most recently computer order entry and decision support. We report on the effectiveness of an institution‐wide intervention to align RBC transfusion practice with best‐practice clinical guidelines. Our approach included institutional endorsement of a RBC transfusion guideline coupled with an ongoing education program and RBC transfusion order set.

METHODS

Study Setting

The University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) is a tertiary care university teaching hospital with a total of 437 patient beds. UAMS is a level 1 trauma center and has 52 ICU beds. The study took place between July 2012 and December 2013. At the time of study initiation, there was no institutional RBC transfusion protocol or guideline.

Study Design

In June 2012, a program was initiated to align RBC transfusion practice at UAMS with best‐practice RBC transfusion guidelines. This initiative consisted of several components: a series of educational programs, followed by hospital medical board approval of an intuitional RBC transfusion guideline, and initiation of an RBC transfusion order set of approved RBC transfusion guideline recommendations (Table 1).

| RBC Transfusion Guideline | |

|---|---|

| |

| PURPOSE: Unnecessary blood transfusions increase healthcare costs and expose patients to potential infectious and noninfectious risks. The purpose of this clinical practice guideline is to establish an evidence‐based approach to the transfusion of RBCs in hospitalized patients at UAMS. | |

| GUIDELINE: In order to avoid the potential risks and increased costs associated with unnecessary blood transfusions, the medical staff of UAMS will adhere to a restrictive transfusion strategy in which: | |

| (I) RBC transfusion should be considered unnecessary for hospitalized, hemodynamically stable patients unless the hemoglobin concentration is <78 g/dL. | |

| (II) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients who have evidence of acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock. | |

| (III) RBC transfusion is appropriate for patients with acute MI or unstable myocardial ischemia if the hemoglobin concentration is 8 g/dL. | |

| (IV) The use of the hemoglobin concentration alone as a trigger for RBC transfusion should be avoided. The decision to order an RBC transfusion should also consider a patient's intravascular volume status, evidence of shock, duration and extent of anemia, and cardiopulmonary physiologic parameters as well as other symptomatology. | |

| (V) In the absence of acute hemorrhage, an RBC transfusion should be ordered and administered as single units. | |

| (VI) It is the physician's responsibility to weigh the risks and benefits of an RBC transfusion for a particular patient based on their medical condition. As such, it is recognized that there will be situations in which an RBC transfusion is appropriate outside of the guidelines put forth in this document. In these instances, the physician should document in the medical record his/her rationale for the RBC transfusion. | |

| RBC Transfusion Order Form | |

| The following are RBC transfusion indications consistent with UAMS‐approved guidelines (check 1): | |

| Acute hemorrhage or hemorrhagic shock | Yes |

| Hgb <78 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute MI, Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| Acute coronary syndrome Hgb 8 g/dL | Yes |

| If the RBC transfusion is for an indication other than those listed above, please note the indication and attending physician in the space provided. | |

| Other indications/attending physician | Free text of other indications. |

| In the absence of acute hemorrhage or a hemoglobin concentration <6.5 g/dL, it is recommended that RBCs be ordered as single units. | |

The educational program included grand rounds presentations for all major clinical departments (internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, geriatrics, anesthesiology), presentations to high‐volume transfusing services (hematology, vascular surgery, cardiac surgery), presentations to hightransfusion‐volume nursing units (eg, medical and surgical ICUs, intermediate care unit, hematology), and scheduled and ad hoc resident educational programs. Educational sessions were repeated over the 18 months of the study and were presented by a clinical content expert.

A UAMS‐specific transfusion guideline was developed based on published best‐practice guidelines.[15, 16] The UAMS medical board approved this guideline in November 2012 (Table 1). The guidelines were disseminated to the entire medical staff in December 2012 via email communication from the hospital's chief medical officer. Membership of the medical board included clinical leadership of the medical center (ie, department chairs) as well as ad hoc members from the hospital administrative leadership.

An RBC transfusion order form that included the guideline recommendations was implemented in the electronic medical record (Sunrise Enterprise 5.5; Eclipsys Corp., Atlanta, GA) in March 2013. There was no hard stop for an RBC transfusion order that was outside of the guideline recommendations; however, for documentation, the ordering physician was required to note the indication and the supervising attending physician for these out‐of‐guideline RBC transfusions. RBC transfusion orders are entered in an electronic medical record. There was no alert triggered by an RBC transfusion order outside of the RBC transfusion guideline.

Outcomes

The number of RBC units transfused during the baseline period of January 2011 through June 2012 was compared with RBC units transfused July 2012 through December 2013. The latter period was further divided into the time period July 2012 through December 2012, during which the education program was initiated (education) as well as the time period January 2013 through December 2013 following the transfusion guideline approval and the initiation of the transfusion order set (decision support). All adult inpatient RBC units transfused, excluding RBC units transfused in the operating room and emergency room, were included in the analysis. RBC transfusions per month were normalized to RBC transfusions per 28 days. RBC transfusions were also calculated as RBC units per adult hospital admission and RBC units per 100 patient‐days.

Hospital mortality is presented as mortality index (observed/predicted mortality). The mean weighted diagnosis‐related group (DRG) was calculated using the monthly average of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)‐derived relative weighted DRGs.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as meanstandard deviation. Comparisons were by Student t test or analysis of variance as appropriate. GraphPad InStat (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis, and Minitab (Minitab Inc., State College, PA) was used for control graphs.

RESULTS

There were 28,393 adult admissions (excluding psychiatry) during the baseline period (January 2011June 2012) and 35,743 (12,353 education, 23,390 decision support) adult admissions during the study period (July 2012December 2013). The patient demographics for the 3 time periods were comparable (Table 2).

| Baseline | Education | Decision Support | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Total patients | 28,393 | 12,353 | 23,390 |

| Age, mean, y* | 48.20.6 | 480.1 | 480.5 |

| Gender, % female | 56 | 57 | 58 |

| Race, % non‐Caucasian | 63 | 61 | 61 |

| Weighted DRG | 1.60 | 1.59 | 1.59 |

| MDC, % | |||

| Nervous system | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Circulatory system | 11 | 12 | 11 |

| Digestive system | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Respiratory system | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Musculoskeletal system | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Kidney and urinary tract | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Hepatobiliary system | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Infectious and parasitic | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Endocrine, metabolic | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Blood, immunologic | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Myeloproliferative | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Multiple significant trauma | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 20 | 20 | 22 |

There was a significant decrease in the mean number of RBC units transfused as a result of the RBC transfusion program (Figure 1A). As compared to the baseline period, the mean number of RBC units transfused fell immediately during the 6 months following the initiation of the education program (92368 to 85240, P=0.02), and further still during the subsequent 12 months following the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the UAMS medical board and initiation of the RBC transfusion order set (to 69052, P<0.0001). These results do not reflect a change in the number of hospital admissions or length of stay; results are comparable if calculated based on RBC units transfused per patient admission or RBC per 100 patient‐days (Figure 1B,C). Overall, there was a 29% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per hospital admission (0.580.040.410.03, P=0.0001) and a 27% reduction in mean RBC units transfused per 100 hospital‐days (10.560.87.680.63, P=0.0001).

RBC transfusion reduction was observed in both the medical and surgical ICUs (Figure 2B) as well as the general patient wards (Figure 2A). The trends noted above were similar in the medical ICU and general patient wards; however, in the surgical ICU, the RBC transfusion rate fell on initiation of the education program and remained stable at this lower rate for the subsequent 18 months, with no further decrease following RBC transfusion guideline approval and initiation of the RBC order set.

There was no significant difference in hospital mortality observed pre‐ versus post‐RBC transfusion program (mortality index 0.890.05 vs 0.840.04, P=0.13).

DISCUSSION

We were able to demonstrate a 25% reduction in total RBC units transfused with an ongoing education program coupled with an institutional adoption of an RBC transfusion guideline that was incorporated into an RBC transfusion order set. Our program was novel in that the RBC transfusion guideline was approved by the hospital medical board as an institutional practice guideline. Importantly, the RBC transfusion reduction has been maintained over a 18‐month period. The program was instituted in stages: educational program, followed by guideline approval by the hospital medical board, and the initiation of an RBC transfusion order set. At each stage we observed an additive increase in RBC transfusion reduction, with the largest reduction following guideline approval and initiation of the order set.

The pattern of RBC transfusion reduction was observed in all areas of the hospital with the exception of the surgical ICU, where transfusion practice remained stable after the initial decrease in RBC transfusions following initiation of the education program. That RBC transfusion practice on the general surgical wards mirrored practice in other areas of the hospital suggests that the difference seen in the surgical ICU reflects factors unique to that specific area rather than the general approach of surgeons to RBC transfusion.

Despite the substantial data now available regarding RBC transfusion risks and the proliferation of RBC transfusion practice guidelines, wide variation in clinical practice still exists.[4, 5] The delay for evidence from clinical studies to be incorporated into clinical practice can be considerable. Balas and Boren[17] have estimated that it may take over 15 years from publication of a landmark study for the results to reach a 50% utilization rate in clinical practice. The barriers to guideline adherence have been described, including lack of familiarity, lack of agreement, and external factors.[6] Overcoming these barriers involve approaches toward knowledge, attitudes, and behavior.

There have been a number of approaches to changing RBC transfusion practice over the last 2 decades.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] These interventions have all achieved varying degrees of success. Most have involved some combination of education, practice guideline, and audit/feedback. More recently, technology has allowed computer‐assisted order entry and feedback. Goodnough et al.,[7] employing real‐time clinical decision support and best‐practice alerts, were able to achieve sustained adherence to clinical guidelines and a 24% reduction in RBC units transfused. Other recent reports have shown improvement in RBC transfusion practices comparable to what we observed with programs including audit/feedback and educational efforts.[13, 14]

Our approach to RBC transfusion practice was relatively simple, involving education followed by institutional adoption of a best‐practice guideline and simple RBC transfusion order form. We were able to begin to change RBC transfusion practice with the initiation of an education program; however, there was a more marked and persistent decrease in RBC transfusions following the adoption of the institution's RBC transfusion guideline and RBC transfusion order set. Although education alone is often ineffective in causing sustained change in behavior, a key aspect of our program was the approval of the RBC transfusion guideline by the hospital medical board. The approval by the hospital medical board, made up in part by the clinical leadership, was instrumental in changing the transfusion culture, or beliefs, in the institution. The consistency of practice seen within the time periods both before and after our intervention suggest a given set of beliefs driving RBC transfusion in each time period. Further supporting this view is the consistency of RBC transfusion practice change throughout the institution, and the fact that patient volumes and severity of illness were comparable pre‐ and postintervention. It is difficult to know which elements of the program were most important. It is likely that optimal transfusion practices promoted by the education program were reinforced by the guideline, which were further reinforced by the order set.

Given the known risks of RBC transfusion and the data supporting a restrictive approach to RBC transfusion practice, improved patient safety by aligning RBC transfusion with best‐practice guidelines was the primary goal of our RBC transfusion program.[1, 2] Although we were not able to look at specific complications such as infection rate, there was no change in overall hospital mortality. The total RBC units transfused at our institution fell by almost 30%. We estimate that in the 18 months following initiation of our program we saved approximately 3200 RBC units as compared with the number of RBC units that would have been transfused based on the transfusion rate prior to the initiation of our educational program. This preserves a scarce resource, RBCs, as a well as reduces cost. The cost of an RBC transfusion involves both the direct cost of the RBC unit as well as the cost of activities surrounding an RBC transfusion. Shander et al.,[18] using an activities‐based costing model, have estimated the direct and indirect cost of an RBC transfusion as between $522 and $1183 (mean $761). Over the last 18 months we have achieved a direct savings of $704,000 for purchase of RBC units and, using the low estimate based on the activities‐based costing model, a total savings of at least $1.7 million.

This study is limited by the fact that it reflects a single‐institution experience. Although we cannot exclude other factors contributing to the decrease in RBC transfusion, the pattern of response suggests that the RBC transfusion program was largely responsible for the results observed. Further, patient volumes at our institution have remained constant, as have surgical volumes. RBC transfusions are reduced comparably whether analyzed as total units transfused, units transfused per admission, or units transfused per 100 patient‐days. The complexity of care also limits our ability to draw any conclusions regarding the impact of RBC transfusion reduction on patient outcome. We also do not know how consistent RBC transfusion practice prior to our program was with our guideline; however, the significant decline in RBC units transfused following our intervention suggests that there was a discrepancy in RBC transfusion practice preintervention.

In conclusion, an education program coupled with institutional adoption of a best‐practice RBC transfusion guideline and a RBC transfusion order set resulted in consistent reduction in RBC units transfused. The improvement in RBC transfusion practice was additive with implementation of each intervention. RBC transfusion practice was changed in all areas of the hospital and resulted in less exposure of patients to RBC transfusion risks, preserved a scarce resource, and was a direct cost savings.

- , , . Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD002042.

- , . Efficacy of RBC transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2667–2674.

- , , , , . A new perspective on best transfusion practice. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:193–202.

- , , , et al. Variation in use of blood transfusion in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1568–1575.

- , , , et al. RBC transfusion practices among critically ill patients: has evidence changed practice? Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2344–2353.

- , , , et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465.

- , , , , , . Improved blood utilization using real‐time clinical decision support. Transfusion. 2014;54:1358–1365.

- , , , , , . Computerized physician order entry with decision support decreases blood transfusion in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1112–e1119.

- , , , et al. Reducing the amount of blood transfused. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:845–852.

- , , , et al. Assessment of education and computerized decision support interventions for improving transfusion practice. Transfusion. 2007;47:228–239.

- , , , , Transfusion insurgency: practice change through education and evidence‐based recommendations. Am J Surg. 2009;197:279–283.

- , , , et al. Evidence‐based red cell transfusion in the critically ill: quality improvement using computerized physician order entry. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1892–1897.

- , , . The addition of decision support into computerize physician order entry reduces red blood cell transfusion resource utilization in the intensive care unit. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:631–633.

- , , , et al. How we closed the gap between red blood cell utilization and whole blood collections in our institution. Transfusion. 2012;52:1857–1867.

- , , , et al. American College of Critical Care and Eastern Association of Trauma. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion practice in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3124–3157.

- , , , et al. Red blood cell transfusion: a clinical practice guideline of the AABB. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:49–58.

- , . Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. In: Bemmel J, McCray AT, eds. Yearbook of Medical Informatics 2000: Patient‐Centered Systems. Stuttgart, Germany: Schattauer Verlagsgesellschaft; 2000:65–70.

- , , , et al. Activity‐based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion. 2010;50:753–764.

- , , . Transfusion thresholds and other strategies for guiding allogeneic red blood cell transfusion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD002042.

- , . Efficacy of RBC transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2667–2674.

- , , , , . A new perspective on best transfusion practice. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:193–202.

- , , , et al. Variation in use of blood transfusion in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2010;304:1568–1575.

- , , , et al. RBC transfusion practices among critically ill patients: has evidence changed practice? Crit Care Med. 2013;41:2344–2353.

- , , , et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? JAMA. 1999;282:1458–1465.

- , , , , , . Improved blood utilization using real‐time clinical decision support. Transfusion. 2014;54:1358–1365.

- , , , , , . Computerized physician order entry with decision support decreases blood transfusion in children. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e1112–e1119.

- , , , et al. Reducing the amount of blood transfused. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:845–852.

- , , , et al. Assessment of education and computerized decision support interventions for improving transfusion practice. Transfusion. 2007;47:228–239.

- , , , , Transfusion insurgency: practice change through education and evidence‐based recommendations. Am J Surg. 2009;197:279–283.

- , , , et al. Evidence‐based red cell transfusion in the critically ill: quality improvement using computerized physician order entry. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1892–1897.

- , , . The addition of decision support into computerize physician order entry reduces red blood cell transfusion resource utilization in the intensive care unit. Am J Hematol. 2007;82:631–633.

- , , , et al. How we closed the gap between red blood cell utilization and whole blood collections in our institution. Transfusion. 2012;52:1857–1867.

- , , , et al. American College of Critical Care and Eastern Association of Trauma. Clinical practice guideline: red blood cell transfusion practice in adult trauma and critical care. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:3124–3157.