User login

Botulinum toxin A tops list of nonsurgical cosmetic procedures in 2013

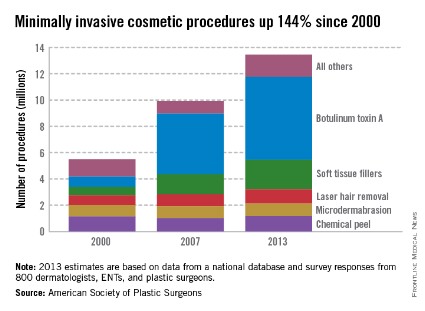

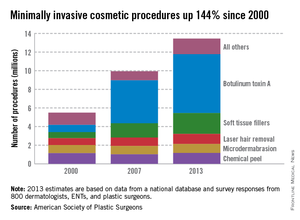

Injection of botulinum toxin type A continues to be the most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery, with a total of more than 6.3 million procedures performed in 2013, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported.

Overall, botulinum toxins such as Botox and Dysport accounted for 47% of the market for minimally invasive procedures, which totaled 13.4 million procedures in 2013, according to the ASPS.

The second most popular surgery was injection of soft tissue fillers, with 2.2 million procedures performed, followed by chemical peels (1.2 million procedures), laser hair removal (1.1 million), and microdermabrasion (970,000), the ASPS said.

The total number of minimally invasive procedures increased by 3% from 2012, as did the number of botulinum injections. The largest increase for a single type of procedure was seen for the soft tissue fillers, with hyaluronic acid injections up 18% from 2012 to 2013, the ASPS noted.

The estimates for 2013 are based on data from a national database and survey responses from 800 dermatologists, ENTs, and plastic surgeons.

Injection of botulinum toxin type A continues to be the most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery, with a total of more than 6.3 million procedures performed in 2013, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported.

Overall, botulinum toxins such as Botox and Dysport accounted for 47% of the market for minimally invasive procedures, which totaled 13.4 million procedures in 2013, according to the ASPS.

The second most popular surgery was injection of soft tissue fillers, with 2.2 million procedures performed, followed by chemical peels (1.2 million procedures), laser hair removal (1.1 million), and microdermabrasion (970,000), the ASPS said.

The total number of minimally invasive procedures increased by 3% from 2012, as did the number of botulinum injections. The largest increase for a single type of procedure was seen for the soft tissue fillers, with hyaluronic acid injections up 18% from 2012 to 2013, the ASPS noted.

The estimates for 2013 are based on data from a national database and survey responses from 800 dermatologists, ENTs, and plastic surgeons.

Injection of botulinum toxin type A continues to be the most popular form of minimally invasive cosmetic surgery, with a total of more than 6.3 million procedures performed in 2013, the American Society of Plastic Surgeons reported.

Overall, botulinum toxins such as Botox and Dysport accounted for 47% of the market for minimally invasive procedures, which totaled 13.4 million procedures in 2013, according to the ASPS.

The second most popular surgery was injection of soft tissue fillers, with 2.2 million procedures performed, followed by chemical peels (1.2 million procedures), laser hair removal (1.1 million), and microdermabrasion (970,000), the ASPS said.

The total number of minimally invasive procedures increased by 3% from 2012, as did the number of botulinum injections. The largest increase for a single type of procedure was seen for the soft tissue fillers, with hyaluronic acid injections up 18% from 2012 to 2013, the ASPS noted.

The estimates for 2013 are based on data from a national database and survey responses from 800 dermatologists, ENTs, and plastic surgeons.

They love me, they love me not ...

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

It was the worst of days. It was the best of days.

When I opened the mail one day last week, I found a letter from someone I’ll call Thelma. It read, in part:

"Last Monday you were kind enough to look at my rash, which you thought was just eczema. You gave me cream and asked me to e-mail you Thursday about my condition. When I did and said I was still itchy, you said I should stick with the same and that I could come back Monday, but I couldn’t wait because I itched so bad I couldn’t take it anymore. I saw another doctor Friday who said the patch was host to something called pityriasis rosea. He said the rash was so textbook it should have been picked up immediately. I had to be put on an oral steroid right away.

"I am so upset that I’m sending you back your bill [for a $15 co-pay] because I had to go to another doctor who could really help me."

I thought of a few choice words for my esteemed Friday colleague, but kept them to myself. A single scaly patch is a textbook case of pityriasis rosea? Oral steroids for pityriasis? Really?

As far as this patient is concerned, I must be a bum. Thirty-five years on the job, and I haven’t mastered the textbook yet.

Sunk in gloom, I opened an e-mail sent to my website by a patient I’ll call Louise:

"I suffer from psoriasis and have been to countless dermatologists since I was 8 years old. I recently had a terrible outbreak and was really hesitant to even go to a dermatologist because I’ve never been satisfied with any of them. Your associate is wonderful! I can’t say enough about her. She is warm, thorough, and really takes the time to sit with you and listen. You can tell she truly cares about her patients and loves her job."

I looked at the patient’s chart. What was the wonderful and satisfying treatment that my associate had prescribed to deal with this patient’s lifelong, recalcitrant psoriasis?

Betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05%. Wow.

I e-mailed my associate at once and we shared a gratified chuckle. Guess no one ever thought of treating Louise’s psoriasis with a topical steroid before. We must be geniuses, right out there on the cutting edge.

So which are we, dear colleagues – geniuses or bums?

We’re neither, of course, which doesn’t stop our patients from forming firm opinions one way or the other. Which they can share by angry letter, fulsome e-mail, or, of course, any on-line reviews they can slip past the mysterious algorithms of the Yelps and Angie’s Lists of the world.

When I get messages like Thelma’s and Louise’s, I show them to my students and make three suggestions:

• Don’t try to look smart at someone else’s expense. Next time around a patient will be in somebody else’s office calling you a fool.

• Don’t respond to snippy patients’ complaints by contacting the complainer and trying to justify yourself. Learn something if you can, and move on.

• Be grateful for praise. Just don’t take it too seriously.

In the meantime, the insurers and assorted bureaucrats who run our lives these days are busy defining good care and claiming to measure it so they can reward quality and punish inefficiency. I’m sure they think they’re doing a fine job, although I remain deeply skeptical that what they choose to measure has much relevance to what actually goes on in offices like ours.

I could, of course, try to tell them why I think so. (I have tried, in fact.) Getting through to people with a completely different way of looking at things than yours is not very rewarding, even when large sums of money are not involved. I would have as good a chance of winning them over as I would of convincing Thelma that a scaly patch is not textbook pityriasis that needs prednisone and Louise that betamethasone cream is not the breakthrough that will change her life.

So: Not the best of times. Not the worst of times. Just another day at the office.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass. He is on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. Dr. Rockoff has contributed to the Under My Skin column in Skin & Allergy News since 1997.

ACC/AHA cardiovascular risk equations get a thumbs-up

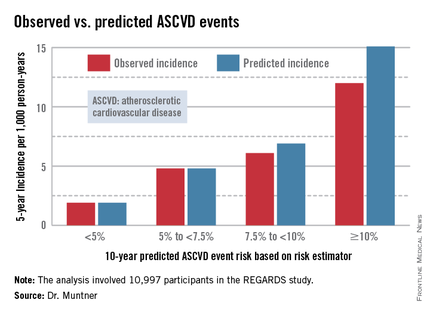

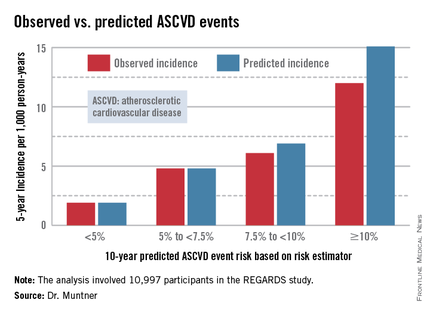

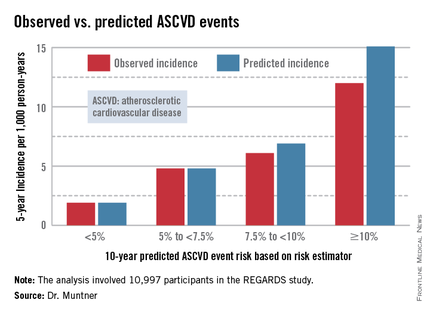

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

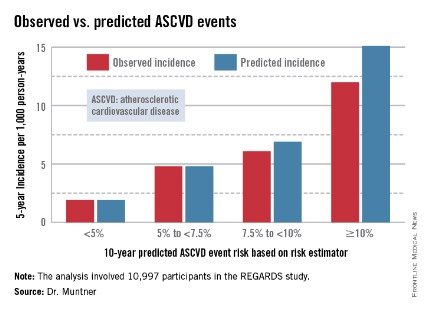

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

WASHINGTON – The controversial cardiovascular risk estimator introduced in the current American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk-assessment guidelines demonstrated "moderate to good" predictive performance when applied to a large U.S. cohort for whom consideration of statin therapy is clinically relevant, Paul Muntner, Ph.D., reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

"We believe that the current study supports the validity of the pooled cohort risk equations to inform clinical management decisions," said Dr. Muntner, professor of epidemiology and of medicine at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The risk estimator has come under strong criticism since the guidelines were released last November. When critics applied the risk estimator to participants in the Women's Health Study, the Physicians' Health Study, and the Women's Health Initiative, they found a big discrepancy between the observed atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) event rates during follow-up and the predicted rates based on the risk calculator, with the ACC/AHA risk estimator tending to markedly overestimate risk. But those analyses involved studies lacking surveillance mechanisms to identify ASCVD events that weren’t reported by participants, according to Dr. Muntner.

"One of the challenges with those big studies is the underreporting of events. Let’s look at the Women’s Health Initiative. Roughly 25% of adjudicated events in that study were not detected because of the reliance on patient reporting. There were two reasons for this: Participants didn’t report a subsequently validated event, or hospital consent forms didn’t permit release of the chart to study investigators," he asserted.

Dr. Muntner presented a new analysis in which the ASCVD risk estimator was applied to participants in the REGARDS (Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke) study, a prospective, observational, population-based study of more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients. He and his coworkers compared the observed 5-year rates of the combined endpoint of death from coronary heart disease, nonfatal MI, or fatal or nonfatal stroke to rates projected by the risk equations.

The analysis was restricted to the 10,997 REGARDS participants who fell into the category of the population for whom the risk equations were designed as a guide in decision making regarding initiation of statin therapy: people aged 40-79 years without atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease or diabetes, not on a statin, and with an LDL cholesterol level of 70-189 mg/dL.

In participants in the lower 10-year ASCVD risk categories based on the equations, the predicted 5-year event rates were spot on with the observed rates. In patients at the higher end of the 10-year risk spectrum, the equations tended to overestimate the event risk (see chart). However, it should be noted that roughly 40% of the REGARDS cohort initiated statin therapy during the 5-year follow-up period, and that would have lowered their event rate, Dr. Muntner said.

The investigators also compared observed and predicted 5-year event rates in a separate REGARDS subgroup composed of 3,333 study participants with Medicare Part A insurance. In this older cohort, the risk equations tended to modestly underestimate the observed ASCVD event rate. "Overall, though, I would say this is pretty good calibration," the epidemiologist commented.

Simultaneous with Dr. Muntner’s presentation at ACC 14, the study results were published (JAMA 2014 April 9;311:1406-15).

The REGARDS study is funded by the National Institutes of Health, as was Dr. Muntner’s analysis. He reported having no relevant financial interests.

AT ACC 14

Major finding: The controversial cardiovascular risk equations at the heart of the latest ACC/AHA risk-assessment guidelines turned in a moderate to good performance in a validation study involving nearly 11,000 participants in a large, observational, prospective study.

Data source: The REGARDS study is a population-based study in which more than 30,000 U.S. black and white patients are being followed prospectively.

Disclosures: The analysis was funded by the National Institutes of Health. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Heparanase regulates response to chemo in MM, team says

SAN DIEGO—Experiments conducted in the lab and the clinic suggest the enzyme heparanase enhances resistance to chemotherapy in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers first found that expression of heparanase, an endoglycosidase that cleaves heparan sulfate, is highly elevated in MM patients after chemotherapy.

The team then used MM cell lines to investigate the mechanism behind this phenomenon.

Their results indicate that, by inhibiting heparanase, we might be able to prevent or delay relapse in MM.

Vishnu Ramani, PhD, of the University of Alabama Birmingham, and his colleagues conducted this research and presented the results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1708).

Several years ago, Dr Ramani’s colleagues (in the lab of Ralph Sanderson, PhD) identified heparanase as a master regulator of aggressive MM. Since then, research has suggested that heparanase fuels aggressive MM by upregulating the expression of pro-angiogenic genes, driving osteolysis, upregulating prometastatic molecules, and controlling the tumor microenvironment.

“We have done a lot of work on the biology of how this molecule works in myeloma, but the one thing I was really interested in was its role in drug resistance,” Dr Ramani said.

So he and his colleagues decided to study heparanase levels in 9 MM patients undergoing chemotherapy. The team isolated tumor cells from patients before and after 2 rounds of chemotherapy and compared heparanase levels at the different time points.

“What we find—and this is really remarkable—is that the expression of heparanase over rounds of therapy goes up several thousand-fold, and this is in the majority of patients,” Dr Ramani said. “In 8 out of 9 patients that we studied, at the end of chemotherapy, the cells that survive have extremely high levels of heparanase.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the researchers studied it in MM cell lines. The team introduced bortezomib to RPMI-8226 and CAG cells and found that heparanase levels increased “dramatically” after treatment.

“The treatment is not only increasing the heparanase expression inside the cell,” Dr Ramani explained. “What the cells do is that, if you continue the treatment, they die, but they don’t take the heparanase with them. They leave it out in the media, and this can be taken in by other cells. So this can activate other cells to promote aggressive tumor growth too.”

Additional investigation revealed that the NF-κB pathway plays a role—namely, chemotherapy activates the pathway to upregulate heparanase. But inhibiting NF-κB activity can prevent that increase in heparanase.

The researchers tested the NF-κB inhibitors BAY 11-7085 and BMS345541 in combination with bortezomib. And they found that both agents prevented bortezomib from elevating heparanase expression in CAG cells.

Dr Ramani and his colleagues also evaluated heparanase levels in chemoresistant MM cell lines. Heparanase levels were 4-fold higher in a doxorubicin-resistant MM cell line and 10-fold higher in a melphalan-resistant cell line, when compared to a wild-type MM cell line.

Next, the researchers compared MM cells with high heparanase expression to those with low heparanase expression. And they discovered that high heparanase levels protect cells from chemotherapy.

After treatment with bortezomib, cells with high heparanase expression were significantly more viable than those with low expression (P<0.05). And there was a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic cells among the low-heparanase population compared to the high-heparanase population (P<0.05).

“If you take cells that have high heparanase and another group of cells that have low heparanase and expose both of them to therapy, the cells with high heparanase always survive better because the heparanase upregulates certain pathways, like the MAP kinase pathway, which helps the cells to survive the onslaught of chemotherapy,” Dr Ramani said. “So myeloma cells are actually hijacking the heparanase pathway to survive better after therapy.”

Building upon that finding, the researchers decided to assess whether inhibiting ERK activity might help cells overcome heparanase-mediated chemoresistance. And experiments showed that the ERK inhibitor U0126 can sensitize cells with high heparanase levels to treatment with bortezomib.

To take this research to the next level, Dr Ramani and his colleagues are collaborating with a company called Sigma Tau, which is developing a heparanase inhibitor called SST-0001. A phase 1 study of the drug in MM patients has been completed, and phase 2 studies are currently recruiting patients in Europe.

Dr Ramani is now conducting experiments in mice to determine how the inhibitor might work in combination with chemotherapy and when it should be administered in order to overcome treatment resistance. He is also looking for other molecular pathways that could be involved in heparanase-related treatment resistance. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—Experiments conducted in the lab and the clinic suggest the enzyme heparanase enhances resistance to chemotherapy in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers first found that expression of heparanase, an endoglycosidase that cleaves heparan sulfate, is highly elevated in MM patients after chemotherapy.

The team then used MM cell lines to investigate the mechanism behind this phenomenon.

Their results indicate that, by inhibiting heparanase, we might be able to prevent or delay relapse in MM.

Vishnu Ramani, PhD, of the University of Alabama Birmingham, and his colleagues conducted this research and presented the results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1708).

Several years ago, Dr Ramani’s colleagues (in the lab of Ralph Sanderson, PhD) identified heparanase as a master regulator of aggressive MM. Since then, research has suggested that heparanase fuels aggressive MM by upregulating the expression of pro-angiogenic genes, driving osteolysis, upregulating prometastatic molecules, and controlling the tumor microenvironment.

“We have done a lot of work on the biology of how this molecule works in myeloma, but the one thing I was really interested in was its role in drug resistance,” Dr Ramani said.

So he and his colleagues decided to study heparanase levels in 9 MM patients undergoing chemotherapy. The team isolated tumor cells from patients before and after 2 rounds of chemotherapy and compared heparanase levels at the different time points.

“What we find—and this is really remarkable—is that the expression of heparanase over rounds of therapy goes up several thousand-fold, and this is in the majority of patients,” Dr Ramani said. “In 8 out of 9 patients that we studied, at the end of chemotherapy, the cells that survive have extremely high levels of heparanase.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the researchers studied it in MM cell lines. The team introduced bortezomib to RPMI-8226 and CAG cells and found that heparanase levels increased “dramatically” after treatment.

“The treatment is not only increasing the heparanase expression inside the cell,” Dr Ramani explained. “What the cells do is that, if you continue the treatment, they die, but they don’t take the heparanase with them. They leave it out in the media, and this can be taken in by other cells. So this can activate other cells to promote aggressive tumor growth too.”

Additional investigation revealed that the NF-κB pathway plays a role—namely, chemotherapy activates the pathway to upregulate heparanase. But inhibiting NF-κB activity can prevent that increase in heparanase.

The researchers tested the NF-κB inhibitors BAY 11-7085 and BMS345541 in combination with bortezomib. And they found that both agents prevented bortezomib from elevating heparanase expression in CAG cells.

Dr Ramani and his colleagues also evaluated heparanase levels in chemoresistant MM cell lines. Heparanase levels were 4-fold higher in a doxorubicin-resistant MM cell line and 10-fold higher in a melphalan-resistant cell line, when compared to a wild-type MM cell line.

Next, the researchers compared MM cells with high heparanase expression to those with low heparanase expression. And they discovered that high heparanase levels protect cells from chemotherapy.

After treatment with bortezomib, cells with high heparanase expression were significantly more viable than those with low expression (P<0.05). And there was a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic cells among the low-heparanase population compared to the high-heparanase population (P<0.05).

“If you take cells that have high heparanase and another group of cells that have low heparanase and expose both of them to therapy, the cells with high heparanase always survive better because the heparanase upregulates certain pathways, like the MAP kinase pathway, which helps the cells to survive the onslaught of chemotherapy,” Dr Ramani said. “So myeloma cells are actually hijacking the heparanase pathway to survive better after therapy.”

Building upon that finding, the researchers decided to assess whether inhibiting ERK activity might help cells overcome heparanase-mediated chemoresistance. And experiments showed that the ERK inhibitor U0126 can sensitize cells with high heparanase levels to treatment with bortezomib.

To take this research to the next level, Dr Ramani and his colleagues are collaborating with a company called Sigma Tau, which is developing a heparanase inhibitor called SST-0001. A phase 1 study of the drug in MM patients has been completed, and phase 2 studies are currently recruiting patients in Europe.

Dr Ramani is now conducting experiments in mice to determine how the inhibitor might work in combination with chemotherapy and when it should be administered in order to overcome treatment resistance. He is also looking for other molecular pathways that could be involved in heparanase-related treatment resistance. ![]()

SAN DIEGO—Experiments conducted in the lab and the clinic suggest the enzyme heparanase enhances resistance to chemotherapy in multiple myeloma (MM).

Researchers first found that expression of heparanase, an endoglycosidase that cleaves heparan sulfate, is highly elevated in MM patients after chemotherapy.

The team then used MM cell lines to investigate the mechanism behind this phenomenon.

Their results indicate that, by inhibiting heparanase, we might be able to prevent or delay relapse in MM.

Vishnu Ramani, PhD, of the University of Alabama Birmingham, and his colleagues conducted this research and presented the results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1708).

Several years ago, Dr Ramani’s colleagues (in the lab of Ralph Sanderson, PhD) identified heparanase as a master regulator of aggressive MM. Since then, research has suggested that heparanase fuels aggressive MM by upregulating the expression of pro-angiogenic genes, driving osteolysis, upregulating prometastatic molecules, and controlling the tumor microenvironment.

“We have done a lot of work on the biology of how this molecule works in myeloma, but the one thing I was really interested in was its role in drug resistance,” Dr Ramani said.

So he and his colleagues decided to study heparanase levels in 9 MM patients undergoing chemotherapy. The team isolated tumor cells from patients before and after 2 rounds of chemotherapy and compared heparanase levels at the different time points.

“What we find—and this is really remarkable—is that the expression of heparanase over rounds of therapy goes up several thousand-fold, and this is in the majority of patients,” Dr Ramani said. “In 8 out of 9 patients that we studied, at the end of chemotherapy, the cells that survive have extremely high levels of heparanase.”

To gain more insight into this phenomenon, the researchers studied it in MM cell lines. The team introduced bortezomib to RPMI-8226 and CAG cells and found that heparanase levels increased “dramatically” after treatment.

“The treatment is not only increasing the heparanase expression inside the cell,” Dr Ramani explained. “What the cells do is that, if you continue the treatment, they die, but they don’t take the heparanase with them. They leave it out in the media, and this can be taken in by other cells. So this can activate other cells to promote aggressive tumor growth too.”

Additional investigation revealed that the NF-κB pathway plays a role—namely, chemotherapy activates the pathway to upregulate heparanase. But inhibiting NF-κB activity can prevent that increase in heparanase.

The researchers tested the NF-κB inhibitors BAY 11-7085 and BMS345541 in combination with bortezomib. And they found that both agents prevented bortezomib from elevating heparanase expression in CAG cells.

Dr Ramani and his colleagues also evaluated heparanase levels in chemoresistant MM cell lines. Heparanase levels were 4-fold higher in a doxorubicin-resistant MM cell line and 10-fold higher in a melphalan-resistant cell line, when compared to a wild-type MM cell line.

Next, the researchers compared MM cells with high heparanase expression to those with low heparanase expression. And they discovered that high heparanase levels protect cells from chemotherapy.

After treatment with bortezomib, cells with high heparanase expression were significantly more viable than those with low expression (P<0.05). And there was a significantly higher percentage of apoptotic cells among the low-heparanase population compared to the high-heparanase population (P<0.05).

“If you take cells that have high heparanase and another group of cells that have low heparanase and expose both of them to therapy, the cells with high heparanase always survive better because the heparanase upregulates certain pathways, like the MAP kinase pathway, which helps the cells to survive the onslaught of chemotherapy,” Dr Ramani said. “So myeloma cells are actually hijacking the heparanase pathway to survive better after therapy.”

Building upon that finding, the researchers decided to assess whether inhibiting ERK activity might help cells overcome heparanase-mediated chemoresistance. And experiments showed that the ERK inhibitor U0126 can sensitize cells with high heparanase levels to treatment with bortezomib.

To take this research to the next level, Dr Ramani and his colleagues are collaborating with a company called Sigma Tau, which is developing a heparanase inhibitor called SST-0001. A phase 1 study of the drug in MM patients has been completed, and phase 2 studies are currently recruiting patients in Europe.

Dr Ramani is now conducting experiments in mice to determine how the inhibitor might work in combination with chemotherapy and when it should be administered in order to overcome treatment resistance. He is also looking for other molecular pathways that could be involved in heparanase-related treatment resistance. ![]()

How mechanical forces affect T cells

used for T-cell force research,

with 3 glass micropipettes

shown under green light.

Georgia Tech/Rob Felt

Investigators say they’ve discovered how T-cell receptors (TCRs) use mechanical contact to decide if the cells they encounter

pose a threat to the body.

The team made their discovery using a sensor based on a red blood cell and a technique for detecting calcium ions emitted by T cells as part of the signaling process.

The researchers studied the binding of antigens to more than a hundred T cells, measuring the forces involved in the binding and the lifetimes of the bonds.

Results revealed that force prolongs TCR bonds for agonists but shortens them for antagonists. And the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“This is the first systematic study of how T-cell recognition is affected by mechanical force, and it shows that forces play an important role in the functions of T cells,” said study author Cheng Zhu, PhD, of Georgia Tech and Emory University in Atlanta. “We think that mechanical force plays a role in almost every step of T-cell biology.”

Dr Zhu and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team used a biomembrane force probe to measure the strength and longevity of bonds between T cells and antigens. The probe consists, in part, of a red blood cell aspirated to a micropipette.

Attached to the red blood cell is a bead on which the investigators placed the antigen under study. Using a delicate mechanism that precisely controls motion, they moved the bead into contact with a TCR, allowing binding to take place.

To test the strength of the bond formed between an antigen and the TCR, the researchers applied piconewton forces to separate the bead holding the antigen from the TCR. The red blood cell then acted as a spring, stretching and allowing a measurement of the forces needed to separate the TCR and antigen.

To assess the impact of the binding on intracellular signaling, the investigators injected a dye into the cells that fluoresces when exposed to calcium signaling ions. Detecting the fluorescence allowed the team to determine when the mechanical force triggered T-cell signaling.

In this way, the researchers learned that interactions between the TCRs and agonist peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) form catch bonds that become stronger with the application of additional force to initiate intracellular signaling.

And less active MHC complexes form slip bonds that weaken with force and don’t initiate signaling.

Overall, the investigators found that the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“Force adds another dimension to interactions with T cells,” Dr Zhu explained. “Antigens that have a bond lifetime that is prolonged by force would have a higher likelihood of triggering signaling. Repeat engagements and lifetime accumulations play a role, and the decision to signal is usually made based on the accumulation of actions, not a single action.”

Researchers already have examples of how mechanical force can affect the operation of cellular systems. For instance, mechanical stress created by blood flow acting on the endothelial cells that line blood vessel walls plays a role in atherosclerosis.

So it isn’t surprising that mechanical forces play a role in the immune system, according to Dr Zhu.

“We now have a broader recognition that the physical environment and mechanical environment regulate many of the biological phenomena in the body,” he said. “When you exert a force on the TCR bonds, some of them dissociate faster, while others come off more slowly. This has an effect on the response of the T-cell receptor.”

As a next step, Dr Zhu’s team would like to explore the effects of force on T-cell development using the new experimental techniques. Evidence suggests the forces to which the cells are exposed while in a juvenile stage may affect the fates of their development. ![]()

used for T-cell force research,

with 3 glass micropipettes

shown under green light.

Georgia Tech/Rob Felt

Investigators say they’ve discovered how T-cell receptors (TCRs) use mechanical contact to decide if the cells they encounter

pose a threat to the body.

The team made their discovery using a sensor based on a red blood cell and a technique for detecting calcium ions emitted by T cells as part of the signaling process.

The researchers studied the binding of antigens to more than a hundred T cells, measuring the forces involved in the binding and the lifetimes of the bonds.

Results revealed that force prolongs TCR bonds for agonists but shortens them for antagonists. And the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“This is the first systematic study of how T-cell recognition is affected by mechanical force, and it shows that forces play an important role in the functions of T cells,” said study author Cheng Zhu, PhD, of Georgia Tech and Emory University in Atlanta. “We think that mechanical force plays a role in almost every step of T-cell biology.”

Dr Zhu and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team used a biomembrane force probe to measure the strength and longevity of bonds between T cells and antigens. The probe consists, in part, of a red blood cell aspirated to a micropipette.

Attached to the red blood cell is a bead on which the investigators placed the antigen under study. Using a delicate mechanism that precisely controls motion, they moved the bead into contact with a TCR, allowing binding to take place.

To test the strength of the bond formed between an antigen and the TCR, the researchers applied piconewton forces to separate the bead holding the antigen from the TCR. The red blood cell then acted as a spring, stretching and allowing a measurement of the forces needed to separate the TCR and antigen.

To assess the impact of the binding on intracellular signaling, the investigators injected a dye into the cells that fluoresces when exposed to calcium signaling ions. Detecting the fluorescence allowed the team to determine when the mechanical force triggered T-cell signaling.

In this way, the researchers learned that interactions between the TCRs and agonist peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) form catch bonds that become stronger with the application of additional force to initiate intracellular signaling.

And less active MHC complexes form slip bonds that weaken with force and don’t initiate signaling.

Overall, the investigators found that the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“Force adds another dimension to interactions with T cells,” Dr Zhu explained. “Antigens that have a bond lifetime that is prolonged by force would have a higher likelihood of triggering signaling. Repeat engagements and lifetime accumulations play a role, and the decision to signal is usually made based on the accumulation of actions, not a single action.”

Researchers already have examples of how mechanical force can affect the operation of cellular systems. For instance, mechanical stress created by blood flow acting on the endothelial cells that line blood vessel walls plays a role in atherosclerosis.

So it isn’t surprising that mechanical forces play a role in the immune system, according to Dr Zhu.

“We now have a broader recognition that the physical environment and mechanical environment regulate many of the biological phenomena in the body,” he said. “When you exert a force on the TCR bonds, some of them dissociate faster, while others come off more slowly. This has an effect on the response of the T-cell receptor.”

As a next step, Dr Zhu’s team would like to explore the effects of force on T-cell development using the new experimental techniques. Evidence suggests the forces to which the cells are exposed while in a juvenile stage may affect the fates of their development. ![]()

used for T-cell force research,

with 3 glass micropipettes

shown under green light.

Georgia Tech/Rob Felt

Investigators say they’ve discovered how T-cell receptors (TCRs) use mechanical contact to decide if the cells they encounter

pose a threat to the body.

The team made their discovery using a sensor based on a red blood cell and a technique for detecting calcium ions emitted by T cells as part of the signaling process.

The researchers studied the binding of antigens to more than a hundred T cells, measuring the forces involved in the binding and the lifetimes of the bonds.

Results revealed that force prolongs TCR bonds for agonists but shortens them for antagonists. And the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“This is the first systematic study of how T-cell recognition is affected by mechanical force, and it shows that forces play an important role in the functions of T cells,” said study author Cheng Zhu, PhD, of Georgia Tech and Emory University in Atlanta. “We think that mechanical force plays a role in almost every step of T-cell biology.”

Dr Zhu and his colleagues described this research in Cell.

The team used a biomembrane force probe to measure the strength and longevity of bonds between T cells and antigens. The probe consists, in part, of a red blood cell aspirated to a micropipette.

Attached to the red blood cell is a bead on which the investigators placed the antigen under study. Using a delicate mechanism that precisely controls motion, they moved the bead into contact with a TCR, allowing binding to take place.

To test the strength of the bond formed between an antigen and the TCR, the researchers applied piconewton forces to separate the bead holding the antigen from the TCR. The red blood cell then acted as a spring, stretching and allowing a measurement of the forces needed to separate the TCR and antigen.

To assess the impact of the binding on intracellular signaling, the investigators injected a dye into the cells that fluoresces when exposed to calcium signaling ions. Detecting the fluorescence allowed the team to determine when the mechanical force triggered T-cell signaling.

In this way, the researchers learned that interactions between the TCRs and agonist peptide-major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) form catch bonds that become stronger with the application of additional force to initiate intracellular signaling.

And less active MHC complexes form slip bonds that weaken with force and don’t initiate signaling.

Overall, the investigators found that the signaling outcome of an interaction between an antigen and a TCR depends on the magnitude, duration, frequency, and timing of the force application.

“Force adds another dimension to interactions with T cells,” Dr Zhu explained. “Antigens that have a bond lifetime that is prolonged by force would have a higher likelihood of triggering signaling. Repeat engagements and lifetime accumulations play a role, and the decision to signal is usually made based on the accumulation of actions, not a single action.”

Researchers already have examples of how mechanical force can affect the operation of cellular systems. For instance, mechanical stress created by blood flow acting on the endothelial cells that line blood vessel walls plays a role in atherosclerosis.

So it isn’t surprising that mechanical forces play a role in the immune system, according to Dr Zhu.

“We now have a broader recognition that the physical environment and mechanical environment regulate many of the biological phenomena in the body,” he said. “When you exert a force on the TCR bonds, some of them dissociate faster, while others come off more slowly. This has an effect on the response of the T-cell receptor.”

As a next step, Dr Zhu’s team would like to explore the effects of force on T-cell development using the new experimental techniques. Evidence suggests the forces to which the cells are exposed while in a juvenile stage may affect the fates of their development. ![]()

Beware of invasive H influenzae disease among pregnant women

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

Experts generally have not considered H influenzae disease to be a substantial contributor to severely adverse fetal outcomes. Yet new research from England and Wales finds that even though pregnant women in their study tended to be younger and healthier than their nonpregnant counterparts, they were far more likely to develop the invasive unencapsulated form of disease and far more likely to present with bacteremia. Not to mention that almost all of their pregnancies resulted in miscarriage, stillbirth, extremely preterm birth, or, at best, the birth of infants with respiratory distress with or without sepsis.

DETAILS OF THE STUDY

Collins and colleagues queried prospectively general practitioners who cared for women of reproductive age (15 to 44 years) with invasive H influenzae disease during the 4-year period of 2009 to 2012. One hundred percent of those queried responded. The study encompassed more than 45 million woman-years of follow-up.

Of the 171 women who developed the infection (confirmed by positive culture from a normally sterile site), approximately 84% (144) had unencapsulated disease. Not quite half (44% or 75) of the 171 women were pregnant at the time of infection. The overall incidence of confirmed invasive H influenzae disease was low at 0.50 per 100,000 women of reproductive age, but the 75 pregnant women were 17.2 (95% confidence interval [CI], 12.2-24.1; P<.001) times as likely to develop the infection as the 96 nonpregnant women (2.98/100,000 woman-years versus 0.17/100,000 woman-years, respectively). And, despite being previously healthy, almost three times as many pregnant as nonpregnant women presented with bacteremia (90.3% versus 33.3%, respectively).

Of 47 women who developed unencapsulated H influenzae infection during the first 24 weeks of pregnancy, 44 lost the fetus and three had extremely preterm births. Of 28 women who developed the infection during the second half of their pregnancy, two had stillbirths. Eight of the 26 live births were preterm, and 21 of the 26 infants had respiratory distress with or without sepsis at birth. The researchers calculated that the rate of pregnancy loss following invasive H influenzae disease was almost 3 times higher than the average rate of pregnancy loss in England and Wales.

CLINICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

It is generally reported that up to one-quarter of the approximately 26,000 stillbirths occurring yearly in the United States are due to some type of maternal or fetal infection.2,3 Dr. Morven S. Edwards, in an editorial4 appearing in the same issue of JAMA as the study, comments, “Given the magnitude of the burden of perinatal deaths, clarifying the extent that bacterial infections result in stillbirth and preterm delivery could potentially inform interventions to improve child and maternal health globally.”

Predicting risk of death in childhood cancer survivors

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Logan Tuttle

Factors other than cancer treatment or chronic health conditions can influence the risk of death among survivors of childhood cancers, according to a study published in the Journal of Cancer Survivorship.

The researchers found an increased risk of death among cancer survivors who rarely exercised, were underweight, visited the doctor 5 or more times a year, considered themselves in “fair” or “poor” health, and had concerns about their future health.

Cheryl Cox, PhD, of the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and her colleagues conducted this research using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

The team compared 7162 childhood cancer survivors to 445 subjects who survived childhood cancer but ultimately died from causes other than cancer or non-health-related events (such as accidents).

The researchers matched subjects according to their primary diagnosis, age at the time of baseline questionnaire, and the time from diagnosis to baseline questionnaire.

Among the 445 subjects who died, the median age at death was 37.6 years. Malignant neoplasms (42%), cardiac conditions (20%), and pulmonary conditions (7%) caused the most deaths.

Subjects who died were slightly older than living subjects and more often of black race (vs white, Hispanic, or “other”). They were less likely to have a post-high school education or to be married. And they were more likely to have a household income below $20,000 or have an existing grade 3 or 4 chronic health condition.

When the researchers adjusted their analyses for sociodemographic characteristics, exposure to chemotherapy and/or radiation, and the number and severity of chronic health conditions, they identified a number of factors associated with an increased risk for all-cause mortality.

One of these factors was a lack of exercise—specifically, not exercising at all (odds ratio [OR]=1.72, P<0.001) or exercising 1 to 2 days a week (OR=1.65, P=0.004), compared to exercising 3 or more days a week.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese did not significantly increase a subject’s risk of death, but being underweight did (OR=2.58, P<0.001).

As one might expect, increased use of medical care was associated with an increased risk of mortality.

Subjects who reported 5 to 6 doctor visits per year had twice the risk of death as subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=2.07, P<0.001). And subjects who reported more than 20 annual doctor visits had a nearly 4-fold greater risk of death than subjects who reported 1 to 2 visits (OR=3.87, P<0.001).

Similarly, subjects had an increased risk of mortality if they described their general health as being “poor” or “fair” (OR=1.98, P<0.001). And being “concerned” or “very concerned” about future health was associated with an increased risk of mortality as well (OR=1.54, P=0.01)

On the other hand, smoking did not have a significant impact on the risk of death, and alcohol consumption appeared to have a positive impact on life expectancy.

Subjects who reported consuming 5 or more drinks per month had a lower risk of mortality than subjects who said they did not consume alcohol at all (OR=0.75, P=0.05).

Dr Cox and her colleagues said this research has revealed novel predictors of mortality not associated with a cancer survivor’s primary disease, treatment, or late effects. And continued observation could point to interventions for reducing the risk of death in these patients. ![]()

Molecule can increase Hb in anemic cancer patients

SAN DIEGO—Results of a pilot study suggest an experimental molecule can increase hemoglobin levels in patients with hematologic malignancies who are suffering from anemia.

The molecule, lexaptepid pegol (NOX-H94), is a pegylated L-stereoisomer RNA aptamer that binds and neutralizes hepcidin.

In this phase 2 study, 5 of 12 patients who received lexaptepid pegol experienced a hemoglobin increase of 1 g/dL or greater and qualified as responders.

Researchers presented these results at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 as abstract 3847. The study was supported by NOXXON Pharma AG, the Berlin, Germany-based company developing lexaptepid pegol.

“Our concept is to treat anemia by inhibiting the activity of hepcidin,” said study investigator Kai Riecke, MD, of NOXXON Pharma.

“Hepcidin regulates iron in the blood. The problem is that, in quite a few tumors, hepcidin reduces iron in the circulation, and, over a long period of time, that leads to iron-restricted anemia.”

So Dr Riecke and his colleagues tested their antihepcidin molecule, lexaptepid pegol, in anemic cancer patients. The team enrolled patients with hemoglobin levels less than 10 g/dL who had been diagnosed with multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, or non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

The patients had a median age of 64 years (range, 35-77). At baseline, the mean hemoglobin was 9.5 ± 0.2 g/dL, the mean serum ferritin was 1067 ± 297 μg/L, the mean serum iron was 34 ± 6 μg/dL, and the mean transferrin saturation was 16.7 ± 3.4%.

The patients received twice-weekly intravenous infusions of lexaptepid pegol for 4 weeks, and the researchers observed patients for 1 month after treatment. Patients were not allowed to receive erythropoiesis-stimulating agents or iron products during the study period.

The results showed increases in hemoglobin of 1 g/dL or greater, which qualified as a response, in 5 of the 12 patients (42%). Three patients achieved a response within 2 weeks of treatment initiation. All 5 patients maintained the increase in hemoglobin throughout the follow-up period.

There was no clear difference in response among the different malignancies, Dr Reike said. But he also noted that, as the study included a small number of patients, it wasn’t really possible for the researchers to make a fair comparison.

In addition to increasing hemoglobin levels, lexaptepid pegol decreased the mean serum ferritin from 1067 μg/L to 815 μg/L in the entire cohort of patients (P=0.014) and from 772 μg/L to 462 μg/L in responders (but this was not significant).

Reticulocyte hemoglobin increased from 22.7 pg to 24.9 pg (P=0.019) in responding patients, but there was no increase in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders—but all 7 of the non-responders—due to differences in measurement capabilities at the different research sites).

“During the treatment, we saw a very nice increase in reticulocyte hemoglobin, which shows, in these patients, the red blood cells were able to take up iron and build up more hemoglobin,” Dr Riecke said.

The researchers also observed an increase in the mean reticulocyte index in responding patients, from 0.9 to 1.2, although the increase was not significant.

“So this shows that, not only do you have an increase in hemoglobin within each reticulocyte, but you have an increase in the number of reticulocytes—something that we didn’t really expect in the beginning,” Dr Riecke said. “And this may be a sign that the efficacy of erythropoiesis is improved.”

Additionally, responding patients experienced a decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels, from 10.0 mg/L to 8.6 mg/L, although this was not significant. Soluble transferrin receptor levels remained unchanged in non-responders. (Data for this measurement were only available for 3 of the responders and 4 of the non-responders.)

“The decrease in soluble transferrin receptor levels is a sign that, in the beginning, the cells were very iron-hungry, and then their hunger was satisfied—at least to a certain extent—during the treatment with our drug,” Dr Reike said. “This is a sign that, by reducing hepcidin, more iron is being released into the circulation, and this iron can effectively be used for erythropoiesis.”