User login

Good or bad, immune responses to cancer are similar

Credit: Aaron Logan

SAN DIEGO—Researchers have found evidence to suggest there may be little difference between an immune response that kills cancer cells and one that stimulates tumor growth.

The team set out to determine whether the immune responses that mediate cancer immunosurveillance and those responsible for inflammatory facilitation are qualitatively or quantitatively distinct.

They tested antibodies in mouse models of a few different cancers, including rituximab in Burkitt lymphoma.

And they found that lower antibody concentrations stimulated tumor growth, while higher concentrations inhibited growth, and the dose range was “surprisingly narrow.”

The researchers reported these findings in a paper published in PNAS and a poster presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1063).

“We have found that the intensity difference between an immune response that stimulates cancer and one that kills it may not be very much,” said principal investigator Ajit Varki, MD, of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“This may come as a surprise to researchers exploring two areas typically considered distinct: the role of the immune system in preventing and killing cancers and the role of chronic inflammation in stimulating cancers. As always, it turns out that the immune system is a double-edged sword.”

The concept of naturally occurring immunosurveillance against malignancies is not new, and there is compelling evidence for it. But understanding this process is confounded by the fact that some types of immune reaction promote tumor development.

Dr Varki and his colleagues looked specifically at a non-human sialic acid sugar molecule called Neu5Gc. Previous research showed that Neu5Gc accumulates in human tumors from dietary sources, despite an ongoing antibody response against it.

The researchers deployed antibodies against Neu5Gc in a mouse tumor model to determine whether and to what degree the antibodies altered tumor progression. The team found that low antibody doses stimulated growth, but high doses inhibited it.

The effect occurred over a “linear and remarkably narrow range,” according to Dr Varki, generating an immune response curve or “inverse hormesis.” Moreover, this curve could be shifted to the left or right simply by modifying the quality of the immune response.

The researchers uncovered similar findings in experiments with mouse models of colon and lung cancer, as well as when they used rituximab in a model of Burkitt lymphoma.

Dr Varki said these results could have implications for all aspects of cancer research. The immune response can have multiple roles in the genesis of cancers, in altering the progress of established tumors and in anticancer therapies that use antibodies as drugs.

Dr Varki is a co-founder of the company Sialix, Inc., which has licensed UC San Diego technologies related to anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in cancer. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

SAN DIEGO—Researchers have found evidence to suggest there may be little difference between an immune response that kills cancer cells and one that stimulates tumor growth.

The team set out to determine whether the immune responses that mediate cancer immunosurveillance and those responsible for inflammatory facilitation are qualitatively or quantitatively distinct.

They tested antibodies in mouse models of a few different cancers, including rituximab in Burkitt lymphoma.

And they found that lower antibody concentrations stimulated tumor growth, while higher concentrations inhibited growth, and the dose range was “surprisingly narrow.”

The researchers reported these findings in a paper published in PNAS and a poster presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1063).

“We have found that the intensity difference between an immune response that stimulates cancer and one that kills it may not be very much,” said principal investigator Ajit Varki, MD, of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“This may come as a surprise to researchers exploring two areas typically considered distinct: the role of the immune system in preventing and killing cancers and the role of chronic inflammation in stimulating cancers. As always, it turns out that the immune system is a double-edged sword.”

The concept of naturally occurring immunosurveillance against malignancies is not new, and there is compelling evidence for it. But understanding this process is confounded by the fact that some types of immune reaction promote tumor development.

Dr Varki and his colleagues looked specifically at a non-human sialic acid sugar molecule called Neu5Gc. Previous research showed that Neu5Gc accumulates in human tumors from dietary sources, despite an ongoing antibody response against it.

The researchers deployed antibodies against Neu5Gc in a mouse tumor model to determine whether and to what degree the antibodies altered tumor progression. The team found that low antibody doses stimulated growth, but high doses inhibited it.

The effect occurred over a “linear and remarkably narrow range,” according to Dr Varki, generating an immune response curve or “inverse hormesis.” Moreover, this curve could be shifted to the left or right simply by modifying the quality of the immune response.

The researchers uncovered similar findings in experiments with mouse models of colon and lung cancer, as well as when they used rituximab in a model of Burkitt lymphoma.

Dr Varki said these results could have implications for all aspects of cancer research. The immune response can have multiple roles in the genesis of cancers, in altering the progress of established tumors and in anticancer therapies that use antibodies as drugs.

Dr Varki is a co-founder of the company Sialix, Inc., which has licensed UC San Diego technologies related to anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in cancer. ![]()

Credit: Aaron Logan

SAN DIEGO—Researchers have found evidence to suggest there may be little difference between an immune response that kills cancer cells and one that stimulates tumor growth.

The team set out to determine whether the immune responses that mediate cancer immunosurveillance and those responsible for inflammatory facilitation are qualitatively or quantitatively distinct.

They tested antibodies in mouse models of a few different cancers, including rituximab in Burkitt lymphoma.

And they found that lower antibody concentrations stimulated tumor growth, while higher concentrations inhibited growth, and the dose range was “surprisingly narrow.”

The researchers reported these findings in a paper published in PNAS and a poster presentation at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014 (abstract 1063).

“We have found that the intensity difference between an immune response that stimulates cancer and one that kills it may not be very much,” said principal investigator Ajit Varki, MD, of the University of California, San Diego School of Medicine.

“This may come as a surprise to researchers exploring two areas typically considered distinct: the role of the immune system in preventing and killing cancers and the role of chronic inflammation in stimulating cancers. As always, it turns out that the immune system is a double-edged sword.”

The concept of naturally occurring immunosurveillance against malignancies is not new, and there is compelling evidence for it. But understanding this process is confounded by the fact that some types of immune reaction promote tumor development.

Dr Varki and his colleagues looked specifically at a non-human sialic acid sugar molecule called Neu5Gc. Previous research showed that Neu5Gc accumulates in human tumors from dietary sources, despite an ongoing antibody response against it.

The researchers deployed antibodies against Neu5Gc in a mouse tumor model to determine whether and to what degree the antibodies altered tumor progression. The team found that low antibody doses stimulated growth, but high doses inhibited it.

The effect occurred over a “linear and remarkably narrow range,” according to Dr Varki, generating an immune response curve or “inverse hormesis.” Moreover, this curve could be shifted to the left or right simply by modifying the quality of the immune response.

The researchers uncovered similar findings in experiments with mouse models of colon and lung cancer, as well as when they used rituximab in a model of Burkitt lymphoma.

Dr Varki said these results could have implications for all aspects of cancer research. The immune response can have multiple roles in the genesis of cancers, in altering the progress of established tumors and in anticancer therapies that use antibodies as drugs.

Dr Varki is a co-founder of the company Sialix, Inc., which has licensed UC San Diego technologies related to anti-Neu5Gc antibodies in cancer. ![]()

How autophagy helps cancer cells evade death

Credit: Sarah Pfau

SAN DIEGO—New research suggests that autophagy may allow cancer cells to recover and divide, rather than die, when faced with chemotherapy.

“What we showed is that if this mechanism doesn’t work right—for example, if autophagy is too high or if the target regulated by autophagy isn’t around—cancer cells may be able to rescue themselves from death caused by chemotherapies,” said study author Andrew Thorburn, PhD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

He and his colleagues believe this finding has important implications. It demonstrates a mechanism whereby autophagy controls cell death, and it further reinforces the clinical potential of inhibiting autophagy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Dr Thorburn and his colleagues recounted their research in Cell Reports and presented it in an education session at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

The researchers had set out to examine how autophagy affects canonical death receptor-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and apoptosis. They found that MOMP occurs at variable times in cells, and it’s delayed by autophagy.

Furthermore, autophagy leads to inefficient MOMP. This causes some cells to die via a slower process than typical apoptosis, which allows them to eventually recover and divide.

Specifically, the researchers found that, as a cancer cell begins to die, mitochondrial cell walls break down. And the cell’s mitochondria release proteins via MOMP.

But then, high autophagy allows the cell to encapsulate and “digest” these released proteins before MOMP can keep the cell well and truly dead. The cell recovers and goes on to divide.

“The implication here is that if you inhibit autophagy, you’d make this less likely to happen; ie, when you kill cancer cells, they would stay dead,” Dr Thorburn said.

He and his colleagues also found that autophagy depends on the target PUMA to regulate cell death. When PUMA is absent, it doesn’t matter if autophagy is inhibited. Without the communicating action of PUMA, cancer cells evade apoptosis and continue to survive.

The researchers said this suggests autophagy can control apoptosis via a regulator that makes MOMP faster and more efficient, thus ensuring the rapid completion of apoptosis.

“Autophagy is complex and, as yet, not fully understood,” Dr Thorburn said. “But now that we see a molecular mechanism whereby cell fate can be determined by autophagy, we hope to discover patient populations that could benefit from drugs that inhibit this action.” ![]()

Credit: Sarah Pfau

SAN DIEGO—New research suggests that autophagy may allow cancer cells to recover and divide, rather than die, when faced with chemotherapy.

“What we showed is that if this mechanism doesn’t work right—for example, if autophagy is too high or if the target regulated by autophagy isn’t around—cancer cells may be able to rescue themselves from death caused by chemotherapies,” said study author Andrew Thorburn, PhD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

He and his colleagues believe this finding has important implications. It demonstrates a mechanism whereby autophagy controls cell death, and it further reinforces the clinical potential of inhibiting autophagy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Dr Thorburn and his colleagues recounted their research in Cell Reports and presented it in an education session at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

The researchers had set out to examine how autophagy affects canonical death receptor-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and apoptosis. They found that MOMP occurs at variable times in cells, and it’s delayed by autophagy.

Furthermore, autophagy leads to inefficient MOMP. This causes some cells to die via a slower process than typical apoptosis, which allows them to eventually recover and divide.

Specifically, the researchers found that, as a cancer cell begins to die, mitochondrial cell walls break down. And the cell’s mitochondria release proteins via MOMP.

But then, high autophagy allows the cell to encapsulate and “digest” these released proteins before MOMP can keep the cell well and truly dead. The cell recovers and goes on to divide.

“The implication here is that if you inhibit autophagy, you’d make this less likely to happen; ie, when you kill cancer cells, they would stay dead,” Dr Thorburn said.

He and his colleagues also found that autophagy depends on the target PUMA to regulate cell death. When PUMA is absent, it doesn’t matter if autophagy is inhibited. Without the communicating action of PUMA, cancer cells evade apoptosis and continue to survive.

The researchers said this suggests autophagy can control apoptosis via a regulator that makes MOMP faster and more efficient, thus ensuring the rapid completion of apoptosis.

“Autophagy is complex and, as yet, not fully understood,” Dr Thorburn said. “But now that we see a molecular mechanism whereby cell fate can be determined by autophagy, we hope to discover patient populations that could benefit from drugs that inhibit this action.” ![]()

Credit: Sarah Pfau

SAN DIEGO—New research suggests that autophagy may allow cancer cells to recover and divide, rather than die, when faced with chemotherapy.

“What we showed is that if this mechanism doesn’t work right—for example, if autophagy is too high or if the target regulated by autophagy isn’t around—cancer cells may be able to rescue themselves from death caused by chemotherapies,” said study author Andrew Thorburn, PhD, of the University of Colorado Denver.

He and his colleagues believe this finding has important implications. It demonstrates a mechanism whereby autophagy controls cell death, and it further reinforces the clinical potential of inhibiting autophagy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy.

Dr Thorburn and his colleagues recounted their research in Cell Reports and presented it in an education session at the AACR Annual Meeting 2014.

The researchers had set out to examine how autophagy affects canonical death receptor-induced mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and apoptosis. They found that MOMP occurs at variable times in cells, and it’s delayed by autophagy.

Furthermore, autophagy leads to inefficient MOMP. This causes some cells to die via a slower process than typical apoptosis, which allows them to eventually recover and divide.

Specifically, the researchers found that, as a cancer cell begins to die, mitochondrial cell walls break down. And the cell’s mitochondria release proteins via MOMP.

But then, high autophagy allows the cell to encapsulate and “digest” these released proteins before MOMP can keep the cell well and truly dead. The cell recovers and goes on to divide.

“The implication here is that if you inhibit autophagy, you’d make this less likely to happen; ie, when you kill cancer cells, they would stay dead,” Dr Thorburn said.

He and his colleagues also found that autophagy depends on the target PUMA to regulate cell death. When PUMA is absent, it doesn’t matter if autophagy is inhibited. Without the communicating action of PUMA, cancer cells evade apoptosis and continue to survive.

The researchers said this suggests autophagy can control apoptosis via a regulator that makes MOMP faster and more efficient, thus ensuring the rapid completion of apoptosis.

“Autophagy is complex and, as yet, not fully understood,” Dr Thorburn said. “But now that we see a molecular mechanism whereby cell fate can be determined by autophagy, we hope to discover patient populations that could benefit from drugs that inhibit this action.” ![]()

Clinical Deterioration Alerts

Patients deemed suitable for care on a general hospital unit are not expected to deteriorate; however, triage systems are not perfect, and some patients on general nursing units do develop critical illness during their hospitalization. Fortunately, there is mounting evidence that deteriorating patients exhibit measurable pathologic changes that could possibly be used to identify them prior to significant adverse outcomes, such as cardiac arrest.[1, 2, 3] Given the evidence that unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) transfers of patients on general units result in worse outcomes than more controlled ICU admissions,[1, 4, 5, 6] it is logical to assume that earlier identification of a deteriorating patient could provide a window of opportunity to prevent adverse outcomes.

The most commonly proposed systematic solution to the problem of identifying and stabilizing deteriorating patients on general hospital units includes some combination of an early warning system (EWS) to detect the deterioration and a rapid response team (RRT) to deal with it.[7, 8, 9, 10] We previously demonstrated that a relatively simple hospital‐specific method for generating EWS alerts derived from the electronic medical record (EMR) database is capable of predicting clinical deterioration and the need for ICU transfer, as well as hospital mortality, in non‐ICU patients admitted to general inpatient medicine units.[11, 12, 13, 14] However, our data also showed that simply providing the EWS alerts to these nursing units did not result in any demonstrable improvement in patient outcomes.[14] Therefore, we set out to determine whether linking real‐time EWS alerts to an intervention and notification of the RRT for patient evaluation could improve the outcomes of patients cared for on general inpatient units.

METHODS

Study Location

The study was conducted on 8 adult inpatient medicine units of Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1250‐bed academic medical center in St. Louis, MO (January 15, 2013May 9, 2013). Patient care on the inpatient medicine units is delivered by either attending hospitalist physicians or dedicated housestaff physicians under the supervision of an attending physician. Continuous electronic vital sign monitoring is not provided on these units. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. This was a nonblinded study (

Patients and Procedures

Patients admitted to the 8 medicine units received usual care during the study except as noted below. Manually obtained vital signs, laboratory data, and pharmacy data inputted in real time into the EMR were continuously assessed. The EWS searched for the 36 input variables previously described[11, 14] from the EMR for all patients admitted to the 8 medicine units 24 hours per day and 7 days a week. Values for every continuous parameter were scaled so that all measurements lay in the interval (0, 1) and were normalized by the minimum and maximum of the parameter as previously described.[14] To capture the temporal effects in our data, we retained a sliding window of all the collected data points within the last 24 hours. We then subdivided these data into a series of 6 sequential buckets of 4 hours each. We excluded the 2 hours of data prior to ICU transfer in building the model (so the data were 26 hours to 2 hours prior to ICU transfer for ICU transfer patients, and the first 24 hours of admission for everyone else). Eligible patients were selected for study entry when they triggered an alert for clinical deterioration as determined by the EWS.[11, 14]

The EWS alert was implemented in an internally developed, Java‐based clinical decision support rules engine, which identified when new data relevant to the model were available in a real‐time central data repository. In a clinical application, it is important to capture unusual changes in vital‐sign data over time. Such changes may precede clinical deterioration by hours, providing a chance to intervene if detected early enough. In addition, not all readings in time‐series data should be treated equally; the value of some kinds of data may change depending on their age. For example, a patient's condition may be better reflected by a blood‐oxygenation reading collected 1 hour ago than a reading collected 12 hours ago. This is the rationale for our use of a sliding window of all collected data points within the last 24 hours performed on a real‐time basis to determine the alert status of the patient.[11, 14]

We applied various threshold cut points to convert the EWS alert predictions into binary values and compared the results against the actual ICU transfer outcome.[14] A threshold of 0.9760 for specificity was chosen to achieve a sensitivity of approximately 40%. These operating characteristics were chosen in turn to generate a manageable number of alerts per hospital nursing unit per day (estimated at 12 per nursing unit per day). At this cut point, the C statistic was 0.8834, with an overall accuracy of 0.9292. In other words, our EWS alert system is calibrated so that for every 1000 patient discharges per year from these 8 hospital units, there would be 75 patients generating an alert, of which 30 patients would be expected to have the study outcome (ie, clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer).

Once patients on the study units were identified as at risk for clinical deterioration by the EWS, they were assigned by a computerized random number generator to the intervention group or the control group. The control group was managed according to the usual care provided on the medicine units. The EWS alerts generated for the control patients were electronically stored, but these alerts were not sent to the RRT nurse, instead they were hidden from all clinical staff. The intervention group had their EWS alerts sent real time to the nursing member of the hospital's RRT. The RRT is composed of a registered nurse, a second‐ or third‐year internal medicine resident, and a respiratory therapist. The RRT was introduced in 2009 for the study units involved in this investigation. For 2009, 2010, and 2011 the RRT nurse was pulled from the staff of 1 of the hospital's ICUs in a rotating manner to respond to calls to the RRT as they occurred. Starting in 2012, the RRT nurse was established as a dedicated position without other clinical responsibilities. The RRT nurse carries a hospital‐issued mobile phone, to which the automated alert messages were sent real time, and was instructed to respond to all EWS alerts within 20 minutes of their receipt.

The RRT nurse would initially evaluate the alerted intervention patients using the Modified Early Warning Score[15, 16] and make further clinical and triage decisions based on those criteria and discussions with the RRT physician or the patient's treating physicians. The RRT focused their interventions using an internally developed tool called the Four Ds (discuss goals of care, drugs needing to be administered, diagnostics needing to be performed, and damage control with the use of oxygen, intravenous fluids, ventilation, and blood products). Patients evaluated by the RRT could have their current level of care maintained, have the frequency of vital sign monitoring increased, be transferred to an ICU, or have a code blue called for emergent resuscitation. The RRT reviewed goals of care for all patients to determine the appropriateness of interventions, especially for patients near the end of life who did not desire intensive care interventions. Nursing staff on the hospital units could also make calls to the RRT for patient evaluation at any time based on their clinical assessments performed during routine nursing rounds.

The primary efficacy outcome was the need for ICU transfer. Secondary outcome measures were hospital mortality and hospital length of stay. Pertinent demographic, laboratory, and clinical data were gathered prospectively including age, gender, race, underlying comorbidities, and severity of illness assessed by the Charlson comorbidity score and Elixhauser comorbidities.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

We required a sample size of 514 patients (257 per group) to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level, based on the superiority design, a baseline event rate for ICU transfer of 20.0%, and an absolute reduction of 8.0% (PS Power and Sample Size Calculations, version 3.0, Vanderbilt Biostatistics, Nashville, TN). Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with 25th and 75th percentiles according to their distribution. The Student t test was used when comparing normally distributed data, and the Mann‐Whitney U test was employed to analyze non‐normally distributed data (eg, hospital length of stay). Categorical data were expressed as frequency distributions, and the [2] test was used to determine if differences existed between groups. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. An interim analysis was planned for the data safety monitoring board to evaluate patient safety after 50% of the patients were recruited. The primary analysis was by intention to treat. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Data Safety Monitoring Board

An independent data safety and monitoring board was convened to monitor the study and to review and approve protocol amendments by the steering committee.

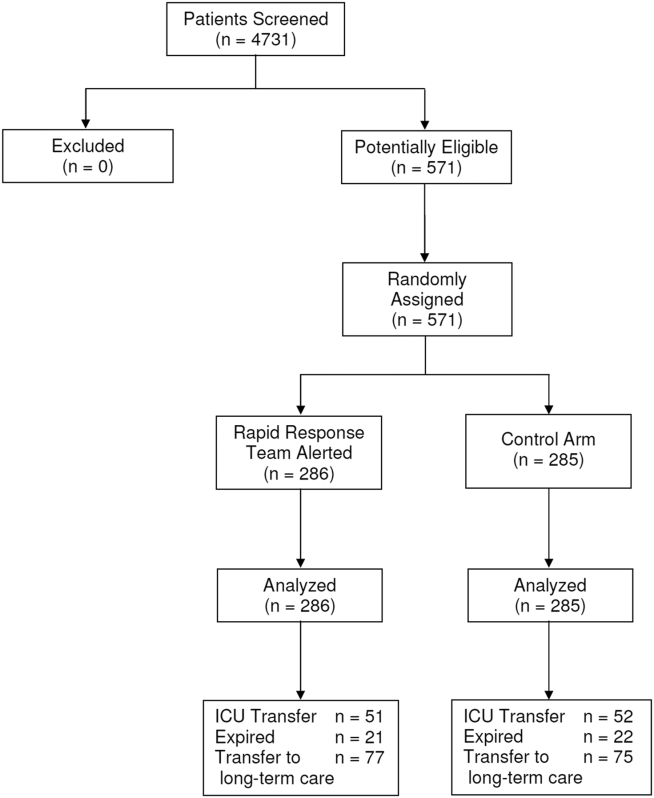

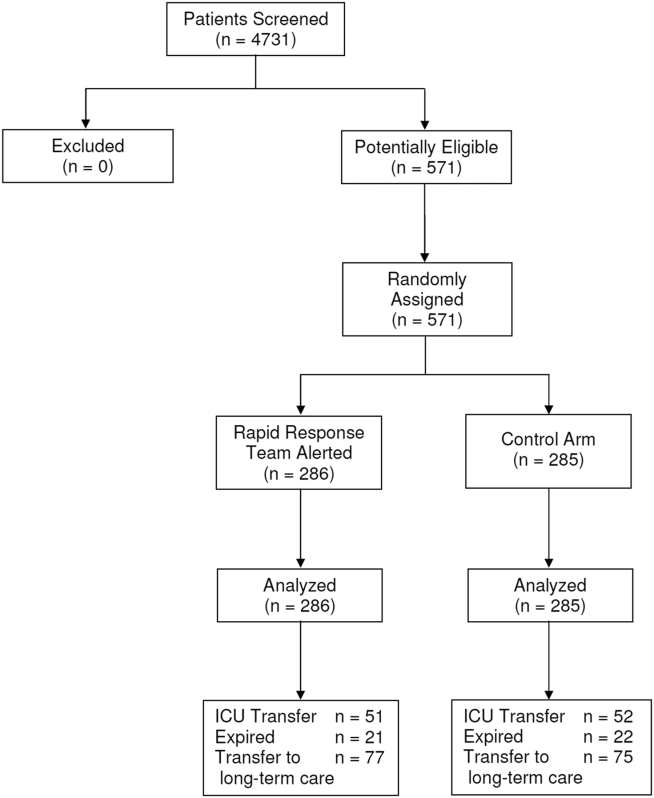

RESULTS

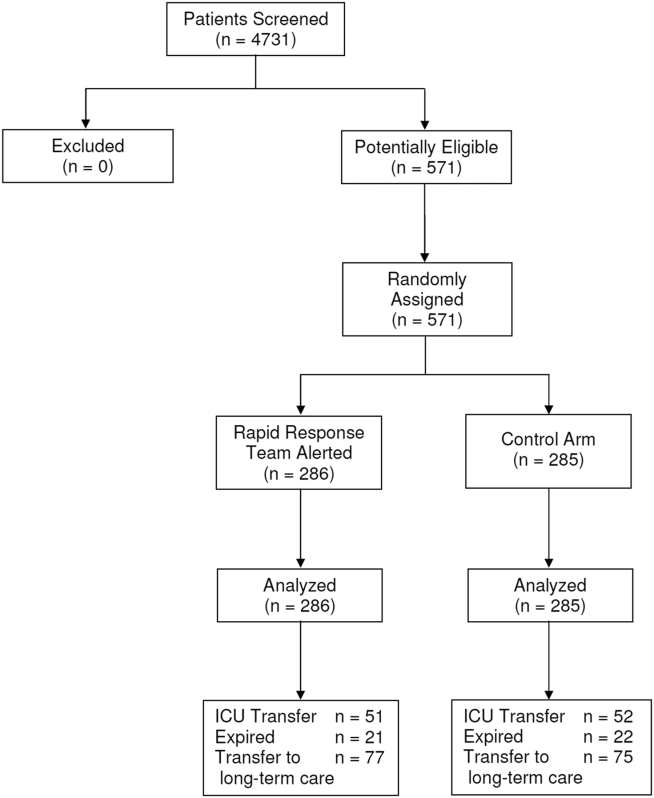

Between January 15, 2013 and May 9, 2013, there were 4731 consecutive patients admitted to the 8 inpatient units and electronically screened as the base population for this investigation. Five hundred seventy‐one (12.1%) patients triggered an alert and were enrolled into the study (Figure 1). There were 286 patients assigned to the intervention group and 285 assigned to the control group. No patients were lost to follow‐up. Demographics, reason for hospital admission, and comorbidities of the 2 groups were similar (Table 1). The number of patients having a separate RRT call by the primary nursing team on the hospital units within 24 hours of generating an alert was greater for the intervention group but did not reach statistical significance (19.9% vs 16.5%; odds ratio: 1.260; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8231.931). Table 2 provides the new diagnostic and therapeutic interventions initiated within 24 hours after a EWS alert was generated. Patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely to have their primary care team physician notified by an RRT nurse regarding medical condition issues and to have oximetry and telemetry started, whereas control patients were significantly more likely to have new antibiotic orders written within 24 hours of generating an alert.

| Variable | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.7 16.0 | 63.1 15.4 | 0.495 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 132 (46.2) | 140 (49.1) | 0.503 |

| Female | 154 (53.8) | 145 (50.9) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 155 (54.2) | 154 (54.0) | 0.417 |

| African American | 105 (36.7) | 113 (39.6) | |

| Other | 26 (9.1) | 18 (6.3) | |

| Reason for hospital admission | |||

| Cardiac | 12 (4.2) | 15 (5.3) | 0.548 |

| Pulmonary | 64 (22.4) | 72 (25.3) | 0.418 |

| Underlying malignancy | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.1) | 0.504 |

| Renal disease | 31 (10.8) | 22 (7.7) | 0.248 |

| Thromboembolism | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 0.752 |

| Infection | 55 (19.2) | 50 (17.5) | 0.603 |

| Neurologic disease | 33 (11.5) | 22 (7.7) | 0.122 |

| Intra‐abdominal disease | 41 (14.3) | 47 (16.5) | 0.476 |

| Hematologic condition | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 0.752 |

| Endocrine disorder | 12 (4.2) | 6 (2.1) | 0.153 |

| Source of hospital admission | |||

| Emergency department | 201 (70.3) | 203 (71.2) | 0.200 |

| Direct admission | 36 (12.6) | 46 (16.1) | |

| Hospital transfer | 49 (17.1) | 36 (12.6) | |

| Charlson score | 6.7 3.6 | 6.6 3.2 | 0.879 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities score | 7.4 3.5 | 7.5 3.4 | 0.839 |

| Variable | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Antibiotics | 92 (32.2) | 121 (42.5) | 0.011 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 48 (16.8) | 44 (15.4) | 0.662 |

| Anticoagulants | 83 (29.0) | 97 (34.0) | 0.197 |

| Diuretics/antihypertensives | 71 (24.8) | 55 (19.3) | 0.111 |

| Bronchodilators | 78 (27.3) | 73 (25.6) | 0.653 |

| Anticonvulsives | 26 (9.1) | 27 (9.5) | 0.875 |

| Sedatives/narcotics | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.499 |

| Respiratory support, n (%) | |||

| Noninvasive ventilation | 17 (6.0) | 9 (3.1) | 0.106 |

| Escalated oxygen support | 12 (4.2) | 7 (2.5) | 0.247 |

| Enhanced vital signs, n (%) | 50 (17.5) | 47 (16.5) | 0.752 |

| Maintenance intravenous fluids, n (%) | 48 (16.8) | 41 (14.4) | 0.430 |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 57 (19.9) | 61 (21.4) | 0.664 |

| Bolus intravenous fluids, n (%) | 7 (2.4) | 14 (4.9) | 0.118 |

| Telemetry, n (%) | 198 (69.2) | 176 (61.8) | 0.052 |

| Oximetry, n (%) | 20 (7.0) | 6 (2.1) | 0.005 |

| New intravenous access, n (%) | 26 (9.1) | 35 (12.3) | 0.217 |

| Primary care team physician called by RRT nurse, n (%) | 82 (28.7) | 56 (19.6) | 0.012 |

Fifty‐one patients (17.8%) randomly assigned to the intervention group required ICU transfer compared with 52 of 285 patients (18.2%) in the control group (odds ratio: 0.972; 95% CI: 0.6351.490; P=0.898) (Table 3). Twenty‐one patients (7.3%) randomly assigned to the intervention group expired during their hospitalization compared with 22 of 285 patients (7.7%) in the control group (odds ratio: 0.947; 95%CI: 0.5091.764; P=0.865). Hospital length of stay was 8.49.5 days (median, 4.5 days; interquartile range, 2.311.4 days) for patients randomized to the intervention group and 9.411.1 days (median, 5.3 days; interquartile range, 3.211.2 days) for patients randomized to the control group (P=0.038). The ICU length of stay was 4.86.6 days (median, 2.9 days; interquartile range, 1.76.5 days) for patients randomized to the intervention group and 5.86.4 days (median, 2.9 days; interquartile range, 1.57.4) for patients randomized to the control group (P=0.812).The number of patients requiring transfer to a nursing home or long‐term acute care hospital was similar for patients in the intervention and control groups (26.9% vs 26.3%; odds ratio: 1.032; 95% CI: 0.7121.495; P=0.870). Similarly, the number of patients requiring hospital readmission before 30 days and 180 days, respectively, was similar for the 2 treatment groups (Table 3). For the combined study population, the EWS alerts were triggered 94138 hours (median, 27 hours; interquartile range, 7132 hours) prior to ICU transfer and 250204 hours (median200 hours; interquartile range, 54347 hours) prior to hospital mortality. The number of RRT calls for the 8 medicine units studied progressively increased from the start of the RRT program in 2009 through 2013 (121 in 2009, 194 in 2010, 298 in 2011, 415 in 2012, 415 in 2013; P<0.001 for the trend).

| Outcome | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| ICU transfer, n (%) | 51 (17.8) | 52 (18.2) | 0.898 |

| All‐cause hospital mortality, n (%) | 21 (7.3) | 22 (7.7) | 0.865 |

| Transfer to nursing home or LTAC, n (%) | 77 (26.9) | 75 (26.3) | 0.870 |

| 30‐day readmission, n (%) | 53 (18.5) | 62 (21.8) | 0.337 |

| 180‐day readmission, n (%) | 124 (43.4) | 117 (41.1) | 0.577 |

| Hospital length of stay, d* | 8.49.5, 4.5 [2.311.4] | 9.411.1, 5.3 [3.211.2] | 0.038 |

| ICU length of stay, d* | 4.86.6, 2.9 [1.76.5] | 5.86.4, 2.9 [1.57.4] | 0.812 |

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that a real‐time EWS alert sent to a RRT nurse was associated with a modest reduction in hospital length of stay, but similar rates of hospital mortality, ICU transfer, and subsequent need for placement in a long‐term care setting compared with usual care. We also found the number of RRT calls to have increased progressively from 2009 to the present on the study units examined.

Unplanned ICU transfers occurring as early as within 8 hours of hospitalization are relatively common and associated with increased mortality.[6] Bapoje et al. evaluated a total of 152 patients over 1 year who had unplanned ICU transfers.[19] The most common reason was worsening of the problem for which the patient was admitted (48%). Other investigators have also attempted to identify predictors for clinical deterioration resulting in unplanned ICU transfer that could be employed in an EWS.[20, 21] Organizations like the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have called for the development and routine implementation of EWSs to direct the activities of RRTs and improve outcomes.[22] However, a recent systematic review found that much of the evidence in support of EWSs and emergency response teams is of poor quality and lacking prospective randomized trials.[23]

Our earlier experience demonstrated that simply providing an alert to nursing units did not result in any demonstrable improvements in the outcomes of high‐risk patients identified by our EWS.[14] Previous investigations have also had difficulty in demonstrating consistent outcome improvements with the use of EWSs and RRTs.[24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] As a result of mandates from quality improvement organizations, most US hospitals currently employ RRTs for emergent mobilization of resources when a clinically deteriorating patient is identified on a hospital ward.[33, 34] Linking RRT actions with a validated real‐time alert may represent a way of improving the overall effectiveness of such teams for monitoring general hospital units, short of having all hospitalized patients in units staffed and monitored to provide higher levels of supervision (eg, ICUs, step‐down units).[9, 35]

An alternative approach to preventing patient deterioration is to provide closer overall monitoring. This has been accomplished by employing nursing personnel to increase monitoring, or with the use of automated monitoring equipment. Bellomo et al. showed that the deployment of electronic automated vital sign monitors on general hospital units was associated with improved utilization of RRTs, increased patient survival, and decreased time for vital sign measurement and recording.[36] Laurens and Dwyer found that implementation of medical emergency teams (METs) to respond to predefined MET activation criteria as observed by hospital staff resulted in reduced hospital mortality and reduced need for ICU transfer.[37] However, other investigators have observed that imperfect implementation of nursing‐performed observational monitoring resulted in no demonstrable benefit, illustrating the limitations of this approach.[38] Our findings suggest that nursing care of patients on general hospital units may be enhanced with the use of an EWS alert sent to the RRT. This is supported by the observation that communications between the RRT and the primary care teams was greater as was the use of telemetry and oximetry in the intervention arm. Moreover, there appears to have been a learning effect for the nursing staff that occurred on our study units, as evidenced by the increased number of RRT calls that occurred between 2009 and 2013. This change in nursing practices on these units certainly made it more difficult for us to observe outcome differences in our current study with the prescribed intervention, reinforcing the notion that evaluating an already established practice is a difficult proposition.[39]

Our study has several important limitations. First, the EWS alert was developed and validated at Barnes‐Jewish Hospital.[11, 12, 13, 14] We cannot say whether this alert will perform similarly in another hospital. Second, the EWS alert only contains data from medical patients. Development and validation of EWS alerts for other hospitalized populations, including surgical and pediatric patients, are needed to make such systems more generalizable. Third, the primary clinical outcome employed for this trial was problematic. Transfer to an ICU may not be an optimal outcome variable, as it may be desirable to transfer alerted patients to an ICU, which can be perceived to represent a soft landing for such patients once an alert has been generated. A better measure could be 30‐day all‐cause mortality, which would not be subject to clinician biases. Finally, we could not specifically identify explanations for the greater use of antibiotics in the control group despite similar rates of infection for both study arms. Future studies should closely evaluate the ability of EWS alerts to alter specific therapies (eg, reduce antibiotic utilization).

In summary, we have demonstrated that an EWS alert linked to a RRT likely contributed to a modest reduction in hospital length of stay, but no reductions in hospital mortality and ICU transfer. These findings suggest that inpatient deterioration on general hospital units can be identified and linked to a specific intervention. Continued efforts are needed to identify and implement systems that will not only accurately identify high‐risk patients on general hospital units but also intervene to improve their outcomes. We are moving forward with the development of a 2‐tiered EWS utilizing both EMR data and real‐time streamed vital sign data, to determine if we can further improve the prediction of clinical deterioration and potentially intervene in a more clinically meaningful manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ann Doyle, BSN, Lisa Mayfield, BSN, and Darain Mitchell for their assistance in carrying out this research protocol; and William Shannon, PhD, from the Division of General Medical Sciences at Washington University, for statistical support.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Foundation, the Chest Foundation of the American College of Chest Physicians, and by grant number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH. The steering committee was responsible for the study design, execution, analysis, and content of the article. The Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Foundation, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the Chest Foundation were not involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the trial. The authors report no conflicts of interest. Marin Kollef, Yixin Chen, Kevin Heard, Gina LaRossa, Chenyang Lu, Nathan Martin, Nelda Martin, Scott Micek, and Thomas Bailey have all made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; have drafted the submitted article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; have provided final approval of the version to be published; and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

- , , , et al. Duration of life‐threatening antecedents prior to intensive care admission. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(11):1629–1634.

- , , , et al. A comparison of antecedents to cardiac arrests, deaths and emergency intensive care admissions in Australia and New Zealand, and the United Kingdom—the ACADEMIA study. Resuscitation. 2004;62(3):275–282.

- , , . Abnormal vital signs are associated with an increased risk for critical events in US veteran inpatients. Resuscitation. 2009;80(11):1264–1269.

- , , , et al. Septic shock: an analysis of outcomes for patients with onset on hospital wards versus intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(6):1020–1024.

- , , , , . Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit: delays are associated with increased mortality and morbidity. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):77–83.

- , , , . Adverse outcomes associated with delayed intensive care unit transfers in an integrated healthcare system. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(3):224–230.

- , , , et al. Findings of the first consensus conference on medical emergency teams. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(9):2463–2478.

- , , , et al. “Identifying the hospitalised patient in crisis”—a consensus conference on the afferent limb of rapid response systems. Resuscitation. 2010;81(4):375–382.

- , , . Rapid‐response teams. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):139–146.

- , , , , . Acute care teams: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):18–26.

- , , , et al. Toward a two‐tier clinical warning system for hospitalized patients. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011;2011:511–519.

- , , , , , . Early prediction of septic shock in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(1):19–25.

- , , , et al. Implementation of a real‐time computerized sepsis alert in nonintensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(3):469–473.

- , , , et al. A trial of a real‐time Alert for clinical deterioration in Patients hospitalized on general medical wards. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(5):236–242.

- , , , , . Prospective evaluation of a modified Early Warning Score to aid earlier detection of patients developing critical illness on a general surgical ward. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:663P.

- , , , . Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM. 2001;94(10):521–526.

- , , . Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD‐9‐CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619.

- , , , . Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36(1):8–27.

- , , , . Unplanned transfers to a medical intensive care unit: causes and relationship to preventable errors in care. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(2):68–72.

- , , , , , . Unplanned transfers to the intensive care unit: the role of the shock index. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(8):460–465.

- , , , , , . Early detection of impending physiologic deterioration among patients who are not in intensive care: development of predictive models using data from an automated electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(5):388–395.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Early warning systems: the next level of rapid response; 2011. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Memberships/MentorHospitalRegistry/Pages/RapidResponseSystems.aspx. Accessed April 6, 2011.

- , . Do either early warning systems or emergency response teams improve hospital patient survival? A systematic review. Resuscitation. 2013;84(12):1652–1667.

- , , , et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward‐randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1398–1404.

- . Out of our reach? Assessing the impact of introducing critical care outreach service. Anaesthesiology. 2003;58(9):882–885.

- , , . Effect of the critical care outreach team on patient survival to discharge from hospital and readmission to critical care: non‐randomised population based study. BMJ. 2003;327(7422):1014.

- , , . Reducing mortality and avoiding preventable ICU utilization: analysis of a successful rapid response program using APR DRGs. J Healthc Qual. 2011;33(5):7–16.

- , , , et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster‐randomised control trial. Lancet. 2005;365(9477):2091–2097.

- , , , , , . The impact of the introduction of critical care outreach services in England: a multicentre interrupted time‐series analysis. Crit Care. 2007;11(5):R113.

- , , , et al. Systematic review and evaluation of physiological track and trigger warning systems for identifying at‐risk patients on the ward. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(4):667–679.

- , , , . Timing and teamwork—an observational pilot study of patients referred to a Rapid Response Team with the aim of identifying factors amenable to re‐design of a Rapid Response System. Resuscitation. 2012;83(6):782–787.

- , , , , , . The impact of rapid response team on outcome of patients transferred from the ward to the ICU: a single‐center study. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(10):2284–2291.

- , , , . Rapid response: a quality improvement conundrum. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):255–257.

- . Rapid response systems now established at 2,900 hospitals. Hospitalist News. 2010;3:1.

- , , . Early warning systems. Hosp Chron. 2012;7:37–43.

- , , , et al. A controlled trial of electronic automated advisory vital signs monitoring in general hospital wards. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2349–2361.

- , . The impact of medical emergency teams on ICU admission rates, cardiopulmonary arrests and mortality in a regional hospital. Resuscitation. 2011;82(6):707–712.

- , , . Imperfect implementation of an early warning scoring system in a danish teaching hospital: a cross‐sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70068.

- , . Introduction of medical emergency teams in Australia and New Zealand: A multicentre study. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):151.

Patients deemed suitable for care on a general hospital unit are not expected to deteriorate; however, triage systems are not perfect, and some patients on general nursing units do develop critical illness during their hospitalization. Fortunately, there is mounting evidence that deteriorating patients exhibit measurable pathologic changes that could possibly be used to identify them prior to significant adverse outcomes, such as cardiac arrest.[1, 2, 3] Given the evidence that unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) transfers of patients on general units result in worse outcomes than more controlled ICU admissions,[1, 4, 5, 6] it is logical to assume that earlier identification of a deteriorating patient could provide a window of opportunity to prevent adverse outcomes.

The most commonly proposed systematic solution to the problem of identifying and stabilizing deteriorating patients on general hospital units includes some combination of an early warning system (EWS) to detect the deterioration and a rapid response team (RRT) to deal with it.[7, 8, 9, 10] We previously demonstrated that a relatively simple hospital‐specific method for generating EWS alerts derived from the electronic medical record (EMR) database is capable of predicting clinical deterioration and the need for ICU transfer, as well as hospital mortality, in non‐ICU patients admitted to general inpatient medicine units.[11, 12, 13, 14] However, our data also showed that simply providing the EWS alerts to these nursing units did not result in any demonstrable improvement in patient outcomes.[14] Therefore, we set out to determine whether linking real‐time EWS alerts to an intervention and notification of the RRT for patient evaluation could improve the outcomes of patients cared for on general inpatient units.

METHODS

Study Location

The study was conducted on 8 adult inpatient medicine units of Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1250‐bed academic medical center in St. Louis, MO (January 15, 2013May 9, 2013). Patient care on the inpatient medicine units is delivered by either attending hospitalist physicians or dedicated housestaff physicians under the supervision of an attending physician. Continuous electronic vital sign monitoring is not provided on these units. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. This was a nonblinded study (

Patients and Procedures

Patients admitted to the 8 medicine units received usual care during the study except as noted below. Manually obtained vital signs, laboratory data, and pharmacy data inputted in real time into the EMR were continuously assessed. The EWS searched for the 36 input variables previously described[11, 14] from the EMR for all patients admitted to the 8 medicine units 24 hours per day and 7 days a week. Values for every continuous parameter were scaled so that all measurements lay in the interval (0, 1) and were normalized by the minimum and maximum of the parameter as previously described.[14] To capture the temporal effects in our data, we retained a sliding window of all the collected data points within the last 24 hours. We then subdivided these data into a series of 6 sequential buckets of 4 hours each. We excluded the 2 hours of data prior to ICU transfer in building the model (so the data were 26 hours to 2 hours prior to ICU transfer for ICU transfer patients, and the first 24 hours of admission for everyone else). Eligible patients were selected for study entry when they triggered an alert for clinical deterioration as determined by the EWS.[11, 14]

The EWS alert was implemented in an internally developed, Java‐based clinical decision support rules engine, which identified when new data relevant to the model were available in a real‐time central data repository. In a clinical application, it is important to capture unusual changes in vital‐sign data over time. Such changes may precede clinical deterioration by hours, providing a chance to intervene if detected early enough. In addition, not all readings in time‐series data should be treated equally; the value of some kinds of data may change depending on their age. For example, a patient's condition may be better reflected by a blood‐oxygenation reading collected 1 hour ago than a reading collected 12 hours ago. This is the rationale for our use of a sliding window of all collected data points within the last 24 hours performed on a real‐time basis to determine the alert status of the patient.[11, 14]

We applied various threshold cut points to convert the EWS alert predictions into binary values and compared the results against the actual ICU transfer outcome.[14] A threshold of 0.9760 for specificity was chosen to achieve a sensitivity of approximately 40%. These operating characteristics were chosen in turn to generate a manageable number of alerts per hospital nursing unit per day (estimated at 12 per nursing unit per day). At this cut point, the C statistic was 0.8834, with an overall accuracy of 0.9292. In other words, our EWS alert system is calibrated so that for every 1000 patient discharges per year from these 8 hospital units, there would be 75 patients generating an alert, of which 30 patients would be expected to have the study outcome (ie, clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer).

Once patients on the study units were identified as at risk for clinical deterioration by the EWS, they were assigned by a computerized random number generator to the intervention group or the control group. The control group was managed according to the usual care provided on the medicine units. The EWS alerts generated for the control patients were electronically stored, but these alerts were not sent to the RRT nurse, instead they were hidden from all clinical staff. The intervention group had their EWS alerts sent real time to the nursing member of the hospital's RRT. The RRT is composed of a registered nurse, a second‐ or third‐year internal medicine resident, and a respiratory therapist. The RRT was introduced in 2009 for the study units involved in this investigation. For 2009, 2010, and 2011 the RRT nurse was pulled from the staff of 1 of the hospital's ICUs in a rotating manner to respond to calls to the RRT as they occurred. Starting in 2012, the RRT nurse was established as a dedicated position without other clinical responsibilities. The RRT nurse carries a hospital‐issued mobile phone, to which the automated alert messages were sent real time, and was instructed to respond to all EWS alerts within 20 minutes of their receipt.

The RRT nurse would initially evaluate the alerted intervention patients using the Modified Early Warning Score[15, 16] and make further clinical and triage decisions based on those criteria and discussions with the RRT physician or the patient's treating physicians. The RRT focused their interventions using an internally developed tool called the Four Ds (discuss goals of care, drugs needing to be administered, diagnostics needing to be performed, and damage control with the use of oxygen, intravenous fluids, ventilation, and blood products). Patients evaluated by the RRT could have their current level of care maintained, have the frequency of vital sign monitoring increased, be transferred to an ICU, or have a code blue called for emergent resuscitation. The RRT reviewed goals of care for all patients to determine the appropriateness of interventions, especially for patients near the end of life who did not desire intensive care interventions. Nursing staff on the hospital units could also make calls to the RRT for patient evaluation at any time based on their clinical assessments performed during routine nursing rounds.

The primary efficacy outcome was the need for ICU transfer. Secondary outcome measures were hospital mortality and hospital length of stay. Pertinent demographic, laboratory, and clinical data were gathered prospectively including age, gender, race, underlying comorbidities, and severity of illness assessed by the Charlson comorbidity score and Elixhauser comorbidities.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

We required a sample size of 514 patients (257 per group) to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level, based on the superiority design, a baseline event rate for ICU transfer of 20.0%, and an absolute reduction of 8.0% (PS Power and Sample Size Calculations, version 3.0, Vanderbilt Biostatistics, Nashville, TN). Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with 25th and 75th percentiles according to their distribution. The Student t test was used when comparing normally distributed data, and the Mann‐Whitney U test was employed to analyze non‐normally distributed data (eg, hospital length of stay). Categorical data were expressed as frequency distributions, and the [2] test was used to determine if differences existed between groups. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. An interim analysis was planned for the data safety monitoring board to evaluate patient safety after 50% of the patients were recruited. The primary analysis was by intention to treat. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Data Safety Monitoring Board

An independent data safety and monitoring board was convened to monitor the study and to review and approve protocol amendments by the steering committee.

RESULTS

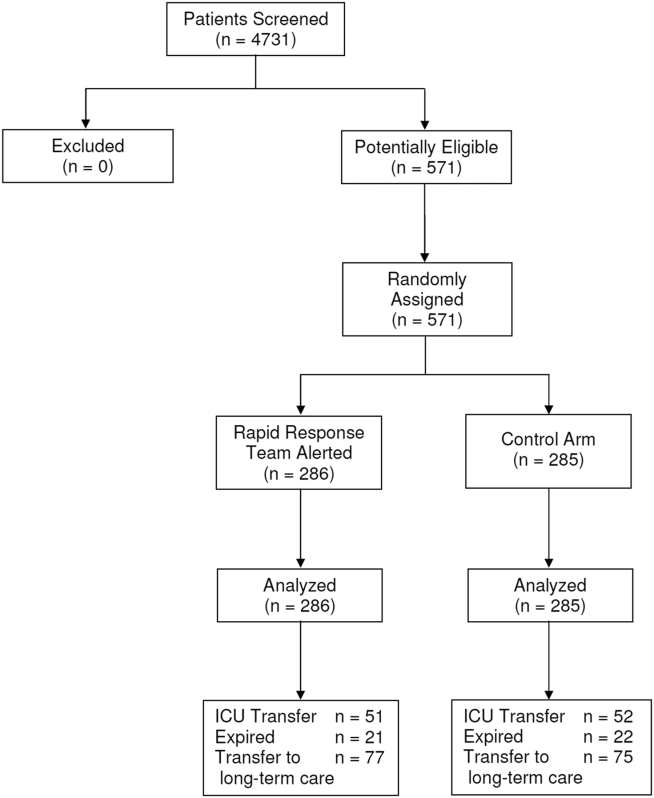

Between January 15, 2013 and May 9, 2013, there were 4731 consecutive patients admitted to the 8 inpatient units and electronically screened as the base population for this investigation. Five hundred seventy‐one (12.1%) patients triggered an alert and were enrolled into the study (Figure 1). There were 286 patients assigned to the intervention group and 285 assigned to the control group. No patients were lost to follow‐up. Demographics, reason for hospital admission, and comorbidities of the 2 groups were similar (Table 1). The number of patients having a separate RRT call by the primary nursing team on the hospital units within 24 hours of generating an alert was greater for the intervention group but did not reach statistical significance (19.9% vs 16.5%; odds ratio: 1.260; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8231.931). Table 2 provides the new diagnostic and therapeutic interventions initiated within 24 hours after a EWS alert was generated. Patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely to have their primary care team physician notified by an RRT nurse regarding medical condition issues and to have oximetry and telemetry started, whereas control patients were significantly more likely to have new antibiotic orders written within 24 hours of generating an alert.

| Variable | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.7 16.0 | 63.1 15.4 | 0.495 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 132 (46.2) | 140 (49.1) | 0.503 |

| Female | 154 (53.8) | 145 (50.9) | |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 155 (54.2) | 154 (54.0) | 0.417 |

| African American | 105 (36.7) | 113 (39.6) | |

| Other | 26 (9.1) | 18 (6.3) | |

| Reason for hospital admission | |||

| Cardiac | 12 (4.2) | 15 (5.3) | 0.548 |

| Pulmonary | 64 (22.4) | 72 (25.3) | 0.418 |

| Underlying malignancy | 6 (2.1) | 3 (1.1) | 0.504 |

| Renal disease | 31 (10.8) | 22 (7.7) | 0.248 |

| Thromboembolism | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 0.752 |

| Infection | 55 (19.2) | 50 (17.5) | 0.603 |

| Neurologic disease | 33 (11.5) | 22 (7.7) | 0.122 |

| Intra‐abdominal disease | 41 (14.3) | 47 (16.5) | 0.476 |

| Hematologic condition | 4 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 0.752 |

| Endocrine disorder | 12 (4.2) | 6 (2.1) | 0.153 |

| Source of hospital admission | |||

| Emergency department | 201 (70.3) | 203 (71.2) | 0.200 |

| Direct admission | 36 (12.6) | 46 (16.1) | |

| Hospital transfer | 49 (17.1) | 36 (12.6) | |

| Charlson score | 6.7 3.6 | 6.6 3.2 | 0.879 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities score | 7.4 3.5 | 7.5 3.4 | 0.839 |

| Variable | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Medications, n (%) | |||

| Antibiotics | 92 (32.2) | 121 (42.5) | 0.011 |

| Antiarrhythmics | 48 (16.8) | 44 (15.4) | 0.662 |

| Anticoagulants | 83 (29.0) | 97 (34.0) | 0.197 |

| Diuretics/antihypertensives | 71 (24.8) | 55 (19.3) | 0.111 |

| Bronchodilators | 78 (27.3) | 73 (25.6) | 0.653 |

| Anticonvulsives | 26 (9.1) | 27 (9.5) | 0.875 |

| Sedatives/narcotics | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | 0.499 |

| Respiratory support, n (%) | |||

| Noninvasive ventilation | 17 (6.0) | 9 (3.1) | 0.106 |

| Escalated oxygen support | 12 (4.2) | 7 (2.5) | 0.247 |

| Enhanced vital signs, n (%) | 50 (17.5) | 47 (16.5) | 0.752 |

| Maintenance intravenous fluids, n (%) | 48 (16.8) | 41 (14.4) | 0.430 |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 57 (19.9) | 61 (21.4) | 0.664 |

| Bolus intravenous fluids, n (%) | 7 (2.4) | 14 (4.9) | 0.118 |

| Telemetry, n (%) | 198 (69.2) | 176 (61.8) | 0.052 |

| Oximetry, n (%) | 20 (7.0) | 6 (2.1) | 0.005 |

| New intravenous access, n (%) | 26 (9.1) | 35 (12.3) | 0.217 |

| Primary care team physician called by RRT nurse, n (%) | 82 (28.7) | 56 (19.6) | 0.012 |

Fifty‐one patients (17.8%) randomly assigned to the intervention group required ICU transfer compared with 52 of 285 patients (18.2%) in the control group (odds ratio: 0.972; 95% CI: 0.6351.490; P=0.898) (Table 3). Twenty‐one patients (7.3%) randomly assigned to the intervention group expired during their hospitalization compared with 22 of 285 patients (7.7%) in the control group (odds ratio: 0.947; 95%CI: 0.5091.764; P=0.865). Hospital length of stay was 8.49.5 days (median, 4.5 days; interquartile range, 2.311.4 days) for patients randomized to the intervention group and 9.411.1 days (median, 5.3 days; interquartile range, 3.211.2 days) for patients randomized to the control group (P=0.038). The ICU length of stay was 4.86.6 days (median, 2.9 days; interquartile range, 1.76.5 days) for patients randomized to the intervention group and 5.86.4 days (median, 2.9 days; interquartile range, 1.57.4) for patients randomized to the control group (P=0.812).The number of patients requiring transfer to a nursing home or long‐term acute care hospital was similar for patients in the intervention and control groups (26.9% vs 26.3%; odds ratio: 1.032; 95% CI: 0.7121.495; P=0.870). Similarly, the number of patients requiring hospital readmission before 30 days and 180 days, respectively, was similar for the 2 treatment groups (Table 3). For the combined study population, the EWS alerts were triggered 94138 hours (median, 27 hours; interquartile range, 7132 hours) prior to ICU transfer and 250204 hours (median200 hours; interquartile range, 54347 hours) prior to hospital mortality. The number of RRT calls for the 8 medicine units studied progressively increased from the start of the RRT program in 2009 through 2013 (121 in 2009, 194 in 2010, 298 in 2011, 415 in 2012, 415 in 2013; P<0.001 for the trend).

| Outcome | Intervention Group, n=286 | Control Group, n=285 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| ICU transfer, n (%) | 51 (17.8) | 52 (18.2) | 0.898 |

| All‐cause hospital mortality, n (%) | 21 (7.3) | 22 (7.7) | 0.865 |

| Transfer to nursing home or LTAC, n (%) | 77 (26.9) | 75 (26.3) | 0.870 |

| 30‐day readmission, n (%) | 53 (18.5) | 62 (21.8) | 0.337 |

| 180‐day readmission, n (%) | 124 (43.4) | 117 (41.1) | 0.577 |

| Hospital length of stay, d* | 8.49.5, 4.5 [2.311.4] | 9.411.1, 5.3 [3.211.2] | 0.038 |

| ICU length of stay, d* | 4.86.6, 2.9 [1.76.5] | 5.86.4, 2.9 [1.57.4] | 0.812 |

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated that a real‐time EWS alert sent to a RRT nurse was associated with a modest reduction in hospital length of stay, but similar rates of hospital mortality, ICU transfer, and subsequent need for placement in a long‐term care setting compared with usual care. We also found the number of RRT calls to have increased progressively from 2009 to the present on the study units examined.

Unplanned ICU transfers occurring as early as within 8 hours of hospitalization are relatively common and associated with increased mortality.[6] Bapoje et al. evaluated a total of 152 patients over 1 year who had unplanned ICU transfers.[19] The most common reason was worsening of the problem for which the patient was admitted (48%). Other investigators have also attempted to identify predictors for clinical deterioration resulting in unplanned ICU transfer that could be employed in an EWS.[20, 21] Organizations like the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have called for the development and routine implementation of EWSs to direct the activities of RRTs and improve outcomes.[22] However, a recent systematic review found that much of the evidence in support of EWSs and emergency response teams is of poor quality and lacking prospective randomized trials.[23]

Our earlier experience demonstrated that simply providing an alert to nursing units did not result in any demonstrable improvements in the outcomes of high‐risk patients identified by our EWS.[14] Previous investigations have also had difficulty in demonstrating consistent outcome improvements with the use of EWSs and RRTs.[24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32] As a result of mandates from quality improvement organizations, most US hospitals currently employ RRTs for emergent mobilization of resources when a clinically deteriorating patient is identified on a hospital ward.[33, 34] Linking RRT actions with a validated real‐time alert may represent a way of improving the overall effectiveness of such teams for monitoring general hospital units, short of having all hospitalized patients in units staffed and monitored to provide higher levels of supervision (eg, ICUs, step‐down units).[9, 35]

An alternative approach to preventing patient deterioration is to provide closer overall monitoring. This has been accomplished by employing nursing personnel to increase monitoring, or with the use of automated monitoring equipment. Bellomo et al. showed that the deployment of electronic automated vital sign monitors on general hospital units was associated with improved utilization of RRTs, increased patient survival, and decreased time for vital sign measurement and recording.[36] Laurens and Dwyer found that implementation of medical emergency teams (METs) to respond to predefined MET activation criteria as observed by hospital staff resulted in reduced hospital mortality and reduced need for ICU transfer.[37] However, other investigators have observed that imperfect implementation of nursing‐performed observational monitoring resulted in no demonstrable benefit, illustrating the limitations of this approach.[38] Our findings suggest that nursing care of patients on general hospital units may be enhanced with the use of an EWS alert sent to the RRT. This is supported by the observation that communications between the RRT and the primary care teams was greater as was the use of telemetry and oximetry in the intervention arm. Moreover, there appears to have been a learning effect for the nursing staff that occurred on our study units, as evidenced by the increased number of RRT calls that occurred between 2009 and 2013. This change in nursing practices on these units certainly made it more difficult for us to observe outcome differences in our current study with the prescribed intervention, reinforcing the notion that evaluating an already established practice is a difficult proposition.[39]

Our study has several important limitations. First, the EWS alert was developed and validated at Barnes‐Jewish Hospital.[11, 12, 13, 14] We cannot say whether this alert will perform similarly in another hospital. Second, the EWS alert only contains data from medical patients. Development and validation of EWS alerts for other hospitalized populations, including surgical and pediatric patients, are needed to make such systems more generalizable. Third, the primary clinical outcome employed for this trial was problematic. Transfer to an ICU may not be an optimal outcome variable, as it may be desirable to transfer alerted patients to an ICU, which can be perceived to represent a soft landing for such patients once an alert has been generated. A better measure could be 30‐day all‐cause mortality, which would not be subject to clinician biases. Finally, we could not specifically identify explanations for the greater use of antibiotics in the control group despite similar rates of infection for both study arms. Future studies should closely evaluate the ability of EWS alerts to alter specific therapies (eg, reduce antibiotic utilization).

In summary, we have demonstrated that an EWS alert linked to a RRT likely contributed to a modest reduction in hospital length of stay, but no reductions in hospital mortality and ICU transfer. These findings suggest that inpatient deterioration on general hospital units can be identified and linked to a specific intervention. Continued efforts are needed to identify and implement systems that will not only accurately identify high‐risk patients on general hospital units but also intervene to improve their outcomes. We are moving forward with the development of a 2‐tiered EWS utilizing both EMR data and real‐time streamed vital sign data, to determine if we can further improve the prediction of clinical deterioration and potentially intervene in a more clinically meaningful manner.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ann Doyle, BSN, Lisa Mayfield, BSN, and Darain Mitchell for their assistance in carrying out this research protocol; and William Shannon, PhD, from the Division of General Medical Sciences at Washington University, for statistical support.

Disclosures: This study was funded in part by the Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Foundation, the Chest Foundation of the American College of Chest Physicians, and by grant number UL1 RR024992 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the NCRR or NIH. The steering committee was responsible for the study design, execution, analysis, and content of the article. The Barnes‐Jewish Hospital Foundation, the American College of Chest Physicians, and the Chest Foundation were not involved in the design, conduct, or analysis of the trial. The authors report no conflicts of interest. Marin Kollef, Yixin Chen, Kevin Heard, Gina LaRossa, Chenyang Lu, Nathan Martin, Nelda Martin, Scott Micek, and Thomas Bailey have all made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; have drafted the submitted article or revised it critically for important intellectual content; have provided final approval of the version to be published; and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Patients deemed suitable for care on a general hospital unit are not expected to deteriorate; however, triage systems are not perfect, and some patients on general nursing units do develop critical illness during their hospitalization. Fortunately, there is mounting evidence that deteriorating patients exhibit measurable pathologic changes that could possibly be used to identify them prior to significant adverse outcomes, such as cardiac arrest.[1, 2, 3] Given the evidence that unplanned intensive care unit (ICU) transfers of patients on general units result in worse outcomes than more controlled ICU admissions,[1, 4, 5, 6] it is logical to assume that earlier identification of a deteriorating patient could provide a window of opportunity to prevent adverse outcomes.

The most commonly proposed systematic solution to the problem of identifying and stabilizing deteriorating patients on general hospital units includes some combination of an early warning system (EWS) to detect the deterioration and a rapid response team (RRT) to deal with it.[7, 8, 9, 10] We previously demonstrated that a relatively simple hospital‐specific method for generating EWS alerts derived from the electronic medical record (EMR) database is capable of predicting clinical deterioration and the need for ICU transfer, as well as hospital mortality, in non‐ICU patients admitted to general inpatient medicine units.[11, 12, 13, 14] However, our data also showed that simply providing the EWS alerts to these nursing units did not result in any demonstrable improvement in patient outcomes.[14] Therefore, we set out to determine whether linking real‐time EWS alerts to an intervention and notification of the RRT for patient evaluation could improve the outcomes of patients cared for on general inpatient units.

METHODS

Study Location

The study was conducted on 8 adult inpatient medicine units of Barnes‐Jewish Hospital, a 1250‐bed academic medical center in St. Louis, MO (January 15, 2013May 9, 2013). Patient care on the inpatient medicine units is delivered by either attending hospitalist physicians or dedicated housestaff physicians under the supervision of an attending physician. Continuous electronic vital sign monitoring is not provided on these units. The study was approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee, and informed consent was waived. This was a nonblinded study (

Patients and Procedures

Patients admitted to the 8 medicine units received usual care during the study except as noted below. Manually obtained vital signs, laboratory data, and pharmacy data inputted in real time into the EMR were continuously assessed. The EWS searched for the 36 input variables previously described[11, 14] from the EMR for all patients admitted to the 8 medicine units 24 hours per day and 7 days a week. Values for every continuous parameter were scaled so that all measurements lay in the interval (0, 1) and were normalized by the minimum and maximum of the parameter as previously described.[14] To capture the temporal effects in our data, we retained a sliding window of all the collected data points within the last 24 hours. We then subdivided these data into a series of 6 sequential buckets of 4 hours each. We excluded the 2 hours of data prior to ICU transfer in building the model (so the data were 26 hours to 2 hours prior to ICU transfer for ICU transfer patients, and the first 24 hours of admission for everyone else). Eligible patients were selected for study entry when they triggered an alert for clinical deterioration as determined by the EWS.[11, 14]

The EWS alert was implemented in an internally developed, Java‐based clinical decision support rules engine, which identified when new data relevant to the model were available in a real‐time central data repository. In a clinical application, it is important to capture unusual changes in vital‐sign data over time. Such changes may precede clinical deterioration by hours, providing a chance to intervene if detected early enough. In addition, not all readings in time‐series data should be treated equally; the value of some kinds of data may change depending on their age. For example, a patient's condition may be better reflected by a blood‐oxygenation reading collected 1 hour ago than a reading collected 12 hours ago. This is the rationale for our use of a sliding window of all collected data points within the last 24 hours performed on a real‐time basis to determine the alert status of the patient.[11, 14]

We applied various threshold cut points to convert the EWS alert predictions into binary values and compared the results against the actual ICU transfer outcome.[14] A threshold of 0.9760 for specificity was chosen to achieve a sensitivity of approximately 40%. These operating characteristics were chosen in turn to generate a manageable number of alerts per hospital nursing unit per day (estimated at 12 per nursing unit per day). At this cut point, the C statistic was 0.8834, with an overall accuracy of 0.9292. In other words, our EWS alert system is calibrated so that for every 1000 patient discharges per year from these 8 hospital units, there would be 75 patients generating an alert, of which 30 patients would be expected to have the study outcome (ie, clinical deterioration requiring ICU transfer).

Once patients on the study units were identified as at risk for clinical deterioration by the EWS, they were assigned by a computerized random number generator to the intervention group or the control group. The control group was managed according to the usual care provided on the medicine units. The EWS alerts generated for the control patients were electronically stored, but these alerts were not sent to the RRT nurse, instead they were hidden from all clinical staff. The intervention group had their EWS alerts sent real time to the nursing member of the hospital's RRT. The RRT is composed of a registered nurse, a second‐ or third‐year internal medicine resident, and a respiratory therapist. The RRT was introduced in 2009 for the study units involved in this investigation. For 2009, 2010, and 2011 the RRT nurse was pulled from the staff of 1 of the hospital's ICUs in a rotating manner to respond to calls to the RRT as they occurred. Starting in 2012, the RRT nurse was established as a dedicated position without other clinical responsibilities. The RRT nurse carries a hospital‐issued mobile phone, to which the automated alert messages were sent real time, and was instructed to respond to all EWS alerts within 20 minutes of their receipt.

The RRT nurse would initially evaluate the alerted intervention patients using the Modified Early Warning Score[15, 16] and make further clinical and triage decisions based on those criteria and discussions with the RRT physician or the patient's treating physicians. The RRT focused their interventions using an internally developed tool called the Four Ds (discuss goals of care, drugs needing to be administered, diagnostics needing to be performed, and damage control with the use of oxygen, intravenous fluids, ventilation, and blood products). Patients evaluated by the RRT could have their current level of care maintained, have the frequency of vital sign monitoring increased, be transferred to an ICU, or have a code blue called for emergent resuscitation. The RRT reviewed goals of care for all patients to determine the appropriateness of interventions, especially for patients near the end of life who did not desire intensive care interventions. Nursing staff on the hospital units could also make calls to the RRT for patient evaluation at any time based on their clinical assessments performed during routine nursing rounds.

The primary efficacy outcome was the need for ICU transfer. Secondary outcome measures were hospital mortality and hospital length of stay. Pertinent demographic, laboratory, and clinical data were gathered prospectively including age, gender, race, underlying comorbidities, and severity of illness assessed by the Charlson comorbidity score and Elixhauser comorbidities.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

We required a sample size of 514 patients (257 per group) to achieve 80% power at a 5% significance level, based on the superiority design, a baseline event rate for ICU transfer of 20.0%, and an absolute reduction of 8.0% (PS Power and Sample Size Calculations, version 3.0, Vanderbilt Biostatistics, Nashville, TN). Continuous variables were reported as means with standard deviations or medians with 25th and 75th percentiles according to their distribution. The Student t test was used when comparing normally distributed data, and the Mann‐Whitney U test was employed to analyze non‐normally distributed data (eg, hospital length of stay). Categorical data were expressed as frequency distributions, and the [2] test was used to determine if differences existed between groups. A P value <0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. An interim analysis was planned for the data safety monitoring board to evaluate patient safety after 50% of the patients were recruited. The primary analysis was by intention to treat. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 11.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL).

Data Safety Monitoring Board

An independent data safety and monitoring board was convened to monitor the study and to review and approve protocol amendments by the steering committee.

RESULTS