User login

Can topiramate reduce nightmares in posttraumatic stress disorder?

Re-experiencing a previous life-threatening stress through nightmares or recurrent memories is a hallmark of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the United States, the lifetime risk of PTSD is 10.1% and the 12-month prevalence is 3.7%.1 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for treating PTSD; clinicians commonly use any SSRI for this disorder. Although SSRIs can alleviate many PTSD symptoms, at times patients experience only a partial response, which necessitates other interventions.

Rationale for using topiramate

The anticonvulsant topiramate blocks voltage-sensitive sodium channels, augments γ-aminobutyric acid type A, antagonizes the glutamate receptor, and inhibits carbonic anhydrase. Researchers have hypothesized that limbic nuclei become sensitized and “kindled” after exposure to a traumatic event. Anticonvulsants such as topiramate may help mitigate stress-activated kindling in PTSD.2,3

What does the evidence say?

Although less compelling than double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, small open-label studies and some case reports indicate a potential role for topiramate in PTSD for specific populations.4,5 In an 8-week open- label study, Alderman et al6 found adjunctive topiramate led to a statistically significant reduction in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores and nightmares in 43 male veterans with combat-related PTSD. There was a nonsignificant decrease in high-risk alcohol use.

In a 2002 retrospective case series, Berlant et al7 found topiramate as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy reduced nightmares in 35 patients with chronic, non-combat PTSD. Nightmares decreased in 79% of patients and flashbacks decreased in 86%, with symptom improvement in a median of 4 days. Limitations of this study included lack of placebo control, a low number of participants, and a high dropout rate (9/35).

Two years later, Berlant8 used the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C) to assess response to topiramate in an open-label study of 33 patients with chronic, non-hallucinatory PTSD. Twenty-eight patients used topiramate as add-on therapy. PCL-C scores decreased by ≥30% in 77% of patients in 4 weeks, with a median dose of 50 mg/d and a median response time of 9 days.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Tucker et al9 assessed 38 civilian patients who took topiramate monotherapy for PTSD. Using the CAPS, researchers concluded that topiramate reduced re-experiencing symptoms, but the effect was not statistically significant.9

Lindley et al10 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study the effect of add-on topiramate in 40 patients with chronic, combat-related PTSD. Because many patients in this study had a history of depression and substance use disorders, topiramate was added to antidepressants; no anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines were used. Similar to previous studies, researchers found no statistically significant effect on PTSD symptom severity or global symptom improvement. However, the small number of participants and a high dropout rate limited this study.10

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 35 men and women age 18 to 62 with PTSD, Yeh et al11 found that topiramate (mean dose: 102.94 mg/d) lead to a statistically significant overall CAPS score reduction, with significant improvements in re-experiencing symptoms, such as nightmares.

Our opinion

FDA-approved treatments such as SSRIs should be the first pharmacologic intervention for PTSD. If a patient’s response is partial or inadequate, consider additional treatment options. For patients with persistent re-experiencing symptoms, evidence and experience with prazosin and trazodone are more robust than that for topiramate.12

Using topiramate to reduce re-experiencing symptoms such as nightmares in PTSD is not supported by statistically significant evidence from double-blind, placebo- controlled trials. However, numerous open-label studies and case reports suggest that there may be a role for topiramate in PTSD patients who do not respond to other treatments. Data indicate that topiramate may be helpful for PTSD patients who have high-risk alcohol use6 or migraine headaches.13 Because some patients who take topiramate lose weight, the medication may be useful for PTSD patients who are overweight.13

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Related Resource

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Nightmares and PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/nightmares.asp.

Drug Brand Names

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

2. Berlin HA. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(4):291-300.

3. Khan S, Liberzon I. Topiramate attenuates exaggerated acoustic startle in an animal model of PTSD. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(2):225-229.

4. Berlant JL. Topiramate in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary clinical observations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 17):60-63.

5. Tucker P, Masters B, Nawar O. Topiramate in the treatment of comorbid night eating syndrome and PTSD: a case study. Eat Disord. 2004;12(1):75-78.

6. Alderman CP, McCarthy LC, Condon JT, et al. Topiramate in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):635-641.

7. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

8. Berlant JL. Prospective open-label study of add-on and monotherapy topiramate in civilians with chronic nonhallucinatory posttraumatic stress disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:24.-

9. Tucker P, Trautman RP, Wyatt DB, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate monotherapy in civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(2):201-206.

10. Lindley SE, Carlson EB, Hill K. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation topiramate for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):677-681.

11. Yeh MS, Mari JJ, Costa MC, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial to study the efficacy of topiramate in a civilian sample of PTSD. CNW Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):305-310.

12. Bajor LA, Ticlea AN, Osser DN. The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on posttraumatic stress disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):240-258.

13. Topax [package insert]. Titusville NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

Re-experiencing a previous life-threatening stress through nightmares or recurrent memories is a hallmark of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the United States, the lifetime risk of PTSD is 10.1% and the 12-month prevalence is 3.7%.1 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for treating PTSD; clinicians commonly use any SSRI for this disorder. Although SSRIs can alleviate many PTSD symptoms, at times patients experience only a partial response, which necessitates other interventions.

Rationale for using topiramate

The anticonvulsant topiramate blocks voltage-sensitive sodium channels, augments γ-aminobutyric acid type A, antagonizes the glutamate receptor, and inhibits carbonic anhydrase. Researchers have hypothesized that limbic nuclei become sensitized and “kindled” after exposure to a traumatic event. Anticonvulsants such as topiramate may help mitigate stress-activated kindling in PTSD.2,3

What does the evidence say?

Although less compelling than double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, small open-label studies and some case reports indicate a potential role for topiramate in PTSD for specific populations.4,5 In an 8-week open- label study, Alderman et al6 found adjunctive topiramate led to a statistically significant reduction in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores and nightmares in 43 male veterans with combat-related PTSD. There was a nonsignificant decrease in high-risk alcohol use.

In a 2002 retrospective case series, Berlant et al7 found topiramate as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy reduced nightmares in 35 patients with chronic, non-combat PTSD. Nightmares decreased in 79% of patients and flashbacks decreased in 86%, with symptom improvement in a median of 4 days. Limitations of this study included lack of placebo control, a low number of participants, and a high dropout rate (9/35).

Two years later, Berlant8 used the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C) to assess response to topiramate in an open-label study of 33 patients with chronic, non-hallucinatory PTSD. Twenty-eight patients used topiramate as add-on therapy. PCL-C scores decreased by ≥30% in 77% of patients in 4 weeks, with a median dose of 50 mg/d and a median response time of 9 days.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Tucker et al9 assessed 38 civilian patients who took topiramate monotherapy for PTSD. Using the CAPS, researchers concluded that topiramate reduced re-experiencing symptoms, but the effect was not statistically significant.9

Lindley et al10 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study the effect of add-on topiramate in 40 patients with chronic, combat-related PTSD. Because many patients in this study had a history of depression and substance use disorders, topiramate was added to antidepressants; no anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines were used. Similar to previous studies, researchers found no statistically significant effect on PTSD symptom severity or global symptom improvement. However, the small number of participants and a high dropout rate limited this study.10

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 35 men and women age 18 to 62 with PTSD, Yeh et al11 found that topiramate (mean dose: 102.94 mg/d) lead to a statistically significant overall CAPS score reduction, with significant improvements in re-experiencing symptoms, such as nightmares.

Our opinion

FDA-approved treatments such as SSRIs should be the first pharmacologic intervention for PTSD. If a patient’s response is partial or inadequate, consider additional treatment options. For patients with persistent re-experiencing symptoms, evidence and experience with prazosin and trazodone are more robust than that for topiramate.12

Using topiramate to reduce re-experiencing symptoms such as nightmares in PTSD is not supported by statistically significant evidence from double-blind, placebo- controlled trials. However, numerous open-label studies and case reports suggest that there may be a role for topiramate in PTSD patients who do not respond to other treatments. Data indicate that topiramate may be helpful for PTSD patients who have high-risk alcohol use6 or migraine headaches.13 Because some patients who take topiramate lose weight, the medication may be useful for PTSD patients who are overweight.13

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Related Resource

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Nightmares and PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/nightmares.asp.

Drug Brand Names

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Re-experiencing a previous life-threatening stress through nightmares or recurrent memories is a hallmark of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the United States, the lifetime risk of PTSD is 10.1% and the 12-month prevalence is 3.7%.1 The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) sertraline and paroxetine are FDA-approved for treating PTSD; clinicians commonly use any SSRI for this disorder. Although SSRIs can alleviate many PTSD symptoms, at times patients experience only a partial response, which necessitates other interventions.

Rationale for using topiramate

The anticonvulsant topiramate blocks voltage-sensitive sodium channels, augments γ-aminobutyric acid type A, antagonizes the glutamate receptor, and inhibits carbonic anhydrase. Researchers have hypothesized that limbic nuclei become sensitized and “kindled” after exposure to a traumatic event. Anticonvulsants such as topiramate may help mitigate stress-activated kindling in PTSD.2,3

What does the evidence say?

Although less compelling than double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, small open-label studies and some case reports indicate a potential role for topiramate in PTSD for specific populations.4,5 In an 8-week open- label study, Alderman et al6 found adjunctive topiramate led to a statistically significant reduction in Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores and nightmares in 43 male veterans with combat-related PTSD. There was a nonsignificant decrease in high-risk alcohol use.

In a 2002 retrospective case series, Berlant et al7 found topiramate as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy reduced nightmares in 35 patients with chronic, non-combat PTSD. Nightmares decreased in 79% of patients and flashbacks decreased in 86%, with symptom improvement in a median of 4 days. Limitations of this study included lack of placebo control, a low number of participants, and a high dropout rate (9/35).

Two years later, Berlant8 used the PTSD Checklist-Civilian version (PCL-C) to assess response to topiramate in an open-label study of 33 patients with chronic, non-hallucinatory PTSD. Twenty-eight patients used topiramate as add-on therapy. PCL-C scores decreased by ≥30% in 77% of patients in 4 weeks, with a median dose of 50 mg/d and a median response time of 9 days.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Tucker et al9 assessed 38 civilian patients who took topiramate monotherapy for PTSD. Using the CAPS, researchers concluded that topiramate reduced re-experiencing symptoms, but the effect was not statistically significant.9

Lindley et al10 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to study the effect of add-on topiramate in 40 patients with chronic, combat-related PTSD. Because many patients in this study had a history of depression and substance use disorders, topiramate was added to antidepressants; no anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, or benzodiazepines were used. Similar to previous studies, researchers found no statistically significant effect on PTSD symptom severity or global symptom improvement. However, the small number of participants and a high dropout rate limited this study.10

In a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 35 men and women age 18 to 62 with PTSD, Yeh et al11 found that topiramate (mean dose: 102.94 mg/d) lead to a statistically significant overall CAPS score reduction, with significant improvements in re-experiencing symptoms, such as nightmares.

Our opinion

FDA-approved treatments such as SSRIs should be the first pharmacologic intervention for PTSD. If a patient’s response is partial or inadequate, consider additional treatment options. For patients with persistent re-experiencing symptoms, evidence and experience with prazosin and trazodone are more robust than that for topiramate.12

Using topiramate to reduce re-experiencing symptoms such as nightmares in PTSD is not supported by statistically significant evidence from double-blind, placebo- controlled trials. However, numerous open-label studies and case reports suggest that there may be a role for topiramate in PTSD patients who do not respond to other treatments. Data indicate that topiramate may be helpful for PTSD patients who have high-risk alcohol use6 or migraine headaches.13 Because some patients who take topiramate lose weight, the medication may be useful for PTSD patients who are overweight.13

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Related Resource

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Nightmares and PTSD. www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/nightmares.asp.

Drug Brand Names

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Prazosin • Minipress

- Topiramate • Topamax

- Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

1. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

2. Berlin HA. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(4):291-300.

3. Khan S, Liberzon I. Topiramate attenuates exaggerated acoustic startle in an animal model of PTSD. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(2):225-229.

4. Berlant JL. Topiramate in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary clinical observations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 17):60-63.

5. Tucker P, Masters B, Nawar O. Topiramate in the treatment of comorbid night eating syndrome and PTSD: a case study. Eat Disord. 2004;12(1):75-78.

6. Alderman CP, McCarthy LC, Condon JT, et al. Topiramate in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):635-641.

7. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

8. Berlant JL. Prospective open-label study of add-on and monotherapy topiramate in civilians with chronic nonhallucinatory posttraumatic stress disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:24.-

9. Tucker P, Trautman RP, Wyatt DB, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate monotherapy in civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(2):201-206.

10. Lindley SE, Carlson EB, Hill K. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation topiramate for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):677-681.

11. Yeh MS, Mari JJ, Costa MC, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial to study the efficacy of topiramate in a civilian sample of PTSD. CNW Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):305-310.

12. Bajor LA, Ticlea AN, Osser DN. The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on posttraumatic stress disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):240-258.

13. Topax [package insert]. Titusville NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

1. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

2. Berlin HA. Antiepileptic drugs for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(4):291-300.

3. Khan S, Liberzon I. Topiramate attenuates exaggerated acoustic startle in an animal model of PTSD. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(2):225-229.

4. Berlant JL. Topiramate in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary clinical observations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 17):60-63.

5. Tucker P, Masters B, Nawar O. Topiramate in the treatment of comorbid night eating syndrome and PTSD: a case study. Eat Disord. 2004;12(1):75-78.

6. Alderman CP, McCarthy LC, Condon JT, et al. Topiramate in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(4):635-641.

7. Berlant J, van Kammen DP. Open-label topiramate as primary or adjunctive therapy in chronic civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(1):15-20.

8. Berlant JL. Prospective open-label study of add-on and monotherapy topiramate in civilians with chronic nonhallucinatory posttraumatic stress disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 2004;4:24.-

9. Tucker P, Trautman RP, Wyatt DB, et al. Efficacy and safety of topiramate monotherapy in civilian posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(2):201-206.

10. Lindley SE, Carlson EB, Hill K. A randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation topiramate for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):677-681.

11. Yeh MS, Mari JJ, Costa MC, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial to study the efficacy of topiramate in a civilian sample of PTSD. CNW Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(5):305-310.

12. Bajor LA, Ticlea AN, Osser DN. The Psychopharmacology Algorithm Project at the Harvard South Shore Program: an update on posttraumatic stress disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):240-258.

13. Topax [package insert]. Titusville NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals; 2009.

How to adapt cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults

Some older patients with depression, anxiety, or insomnia may be reluctant to turn to pharmacotherapy and may prefer psychotherapeutic treatments.1 Evidence has established cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as an effective intervention for several psychiatric disorders and CBT should be considered when treating geriatric patients (Table 1).2

Table 1

Indications for CBT

| Mild to moderate depression. In the case of severe depression, CBT can be combined with pharmacotherapy |

| Anxiety disorders, mixed anxiety states |

| Insomnia—both primary and comorbid with other medical and/or psychiatric conditions |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Research evaluating the efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults was first published in the early 1980s. Since then, research and application of CBT with older adults has expanded to include other psychiatric disorders and researchers have suggested changes to increase the efficacy of CBT for these patients. This article provides:

- an overview of CBT’s efficacy for older adults with depression, anxiety, and insomnia

- modifications to employ when providing CBT to older patients.

The cognitive model of CBT

In the 1970s, Aaron T. Beck, MD, developed CBT while working with depressed patients. Beck’s patients reported thoughts characterized by inaccuracies and distortions in association with their depressed mood. He found these thoughts could be brought to the patient’s conscious attention and modified to improve the patient’s depression. This finding led to the development of CBT.

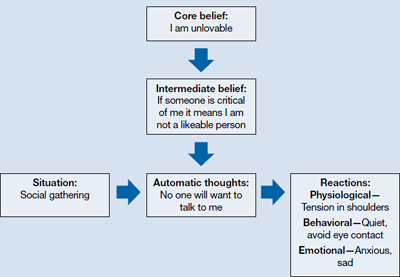

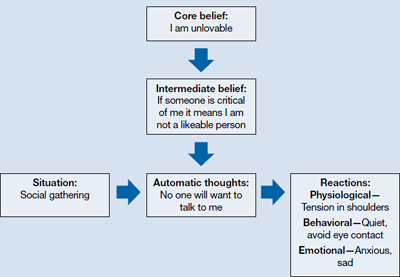

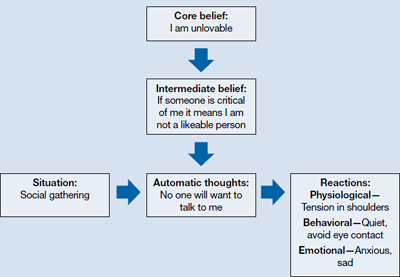

CBT is based on a cognitive model of the relationship among cognition, emotion, and behavior. Mood and behavior are viewed as determined by a person’s perception and interpretation of events, which manifest as a stream of automatically generated thoughts (Figure).3 These automatic thoughts have their origins in an underlying network of beliefs or schema. Patients with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression typically have frequent automatic thoughts that characteristically lack validity because they arise from dysfunctional beliefs. The therapeutic process consists of helping the patient become aware of his or her internal stream of thoughts when distressed, and to identify and modify the dysfunctional thoughts. Behavioral techniques are used to bring about functional changes in behavior, regulate emotion, and help the cognitive restructuring process. Modifying the patient’s underlying dysfunctional beliefs leads to lasting improvements. In this structured therapy, the therapist and patient work collaboratively to use an approach that features reality testing and experimentation.4

Figure

The cognitive model of CBT

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Source: Adapted from reference 3

Indications for CBT in older adults

Depression. Among psychotherapies used in older adults, CBT has received the most research for late-life depression.5 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found CBT is superior to treatment as usual in depressed adults age ≥60.6 It also has been found to be superior to wait-list control7 and talking as control.6,8 Meta-analyses have shown above-average effect sizes for CBT in treating late-life depression.9,10 A follow-up study found improvement was maintained up to 2 years after CBT, which suggests CBT’s impact is likely to be long lasting.11

Thompson et al12 compared 102 depressed patients age >60 who were treated with CBT alone, desipramine alone, or a combination of the 2. A combination of medication and CBT worked best for severely depressed patients; CBT alone or a combination of CBT and medication worked best for moderately depressed patients.

CBT is an option when treating depressed medically ill older adults. Research indicates that CBT could reduce depression in older patients with Parkinson’s disease13 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14

As patients get older, cognitive impairment with comorbid depression can make treatment challenging. Limited research suggests CBT applied in a modified format that involves caregivers and uses problem solving and behavioral strategies can significantly reduce depression in patients with dementia.15

Anxiety. Researchers have examined the efficacy of variants of CBT in treating older adults with anxiety disorders—commonly, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, subjective anxiety, or a combination of these illnesses.16,17 Randomized trials have supported CBT’s efficacy for older patients with GAD and mixed anxiety states; gains made in CBT were maintained over a 1-year follow-up.18,19 In a meta-analysis of 15 studies using cognitive and behavioral methods of treating anxiety in older patients, Nordhus and Pallesen16 reported a significant effect size of 0.55. In a 2008 meta-analysis that included only RCTs, CBT was superior to wait-list conditions as well as active control conditions in treating anxious older patients.20

However, some research suggests that CBT for GAD may not be as effective for older adults as it is for younger adults. In a study of CBT for GAD in older adults, Stanley et al19 reported smaller effect sizes compared with CBT for younger adults. Researchers have found relatively few differences between CBT and comparison conditions—supportive psychotherapy or active control conditions—in treating GAD in older adults.21 Modified, more effective formats of CBT for GAD in older adults need to be established.22 Mohlman et al23 supplemented standard CBT for late-life GAD with memory and learning aids—weekly reading assignments, graphing exercises to chart mood ratings, reminder phone calls from therapists, and homework compliance requirement. This approach improved the response rate from 40% to 75%.23

Insomnia. Studies have found CBT to be an effective means of treating insomnia in geriatric patients. Although sleep problems occur more frequently among older patients, only 15% of chronic insomnia patients receive treatment; psychotherapy rarely is used.24 CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) should be considered for older adults because managing insomnia with medications may be problematic and these patients may prefer nonpharmacologic treatment.2 CBT-I typically incorporates cognitive strategies with established behavioral techniques, including sleep hygiene education, cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, stimulus control, and/or sleep restriction. The CBT-I multicomponent treatment package meets all criteria to be considered an evidence-based treatment for late-life insomnia.25

RCTs have reported significant improvements in late-life insomnia with CBT-I.26,27 Reviews and meta-analyses have also concluded that cognitive-behavioral treatments are effective for treating insomnia in older adults.25,28 Most insomnia cases in geriatric patients are reported to occur secondary to other medical or psychiatric conditions that are judged as causing the insomnia.25 In these cases, direct treatment of the insomnia usually is delayed or omitted.28 Studies evaluating the efficacy of CBT packages for treating insomnia occurring in conjunction with other medical or psychiatric illnesses have reported significant improvement of insomnia.28,29 Because insomnia frequently occurs in older patients with medical illnesses and psychiatric disorders, CBT-I could be beneficial for such patients.

Good candidates for CBT

Clinical experience indicates that older adults in relatively good health with no significant cognitive decline are good candidates for CBT. These patients tend to comply with their assignments, are interested in applying the learned strategies, and are motivated to read self-help books. CBT’s structured, goal-oriented approach makes it a short-term treatment, which makes it cost effective. Insomnia patients may improve after 6 to 8 CBT-I sessions and patients with anxiety or depression may need to undergo 15 to 20 CBT sessions. Patients age ≥65 have basic Medicare coverage that includes mental health care and psychotherapy.

There are no absolute contraindications for CBT, but the greater the cognitive impairment, the less the patient will benefit from CBT (Table 2). Similarly, severe depression and anxiety might make it difficult for patients to participate meaningfully, although CBT may be incorporated gradually as patients improve with medication. Severe medical illnesses and sensory losses such as visual and hearing loss would make it difficult to carry out CBT effectively.

Table 2

Contraindications for CBT

| High levels of cognitive impairment |

| Severe depression with psychotic features |

| Severe anxiety with high levels of agitation |

| Severe medical illness |

| Sensory losses |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Adapting CBT for older patients

When using CBT with older patients, it is important to keep in mind characteristics that define the geriatric population. Laidlaw et al30 developed a model to help clinicians develop a more appropriate conceptualization of older patients that focuses on significant events and related cognitions associated with physical health, changes in role investments, and interactions with younger generations. It emphasizes the need to explore beliefs about aging viewed through each patient’s socio-cultural lens and examine cognitions in the context of the time period in which the individual has lived.

Losses and transitions. For many older patients, the latter years of life are characterized by losses and transitions.31 According to Thompson,31 these losses and transitions can trigger thoughts of missed opportunities or unresolved relationships and reflection on unachieved goals.31 CBT for older adults should focus on the meaning the patient gives to these losses and transitions. For example, depressed patients could view their retirement as a loss of self worth as they become less productive. CBT can help patients identify ways of thinking about the situation that will enable them to adapt to these losses and transitions.

Changes in cognition. Changes in cognitive functioning with aging are not universal and there’s considerable variability, but it’s important to make appropriate adaptations when needed. Patients may experience a decline in cognitive speed, working memory, selective attention, and fluid intelligence. This would require that information be presented slowly, with frequent repetitions and summaries. Also, it might be helpful to present information in alternate ways and to encourage patients to take notes during sessions. To accommodate for a decline in fluid intelligence, presenting new information in the context of previous experiences will help promote learning. Recordings of important information and conclusions from cognitive restructuring that patients can listen to between sessions could serve as helpful reminders that will help patients progress. Phone prompts or alarms can remind patients to carry out certain therapeutic measures, such as breathing exercises. Caretakers can attend sessions to become familiar with strategies performed during CBT and act as a co-therapist at home; however, their inclusion must be done with the consent of both parties and only if it’s viewed as necessary for the patient’s progress.

Additional strategies. For patients with substantial cognitive decline, cognitive restructuring might not be as effective as behavioral strategies—activity scheduling, graded task assignment, graded exposure, and rehearsals. Because older adults often have strengthened dysfunctional beliefs over a long time, modifying them takes longer, which is why the tapering process usually takes longer for older patients than for younger patients. The lengthier tapering ensures learning is well established and the process of modifying dysfunctional beliefs to functional beliefs continues. Collaborating with other professionals—physicians, social workers, and case managers—will help ensure a shared care process in which common goals are met.

The websites of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, American Psychological Association, and Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies can help clinicians who do not offer CBT to locate a qualified therapist for their patients (Related Resources).

- Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

- American Psychological Association. www.apa.org.

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. www.abct.org.

- Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Dick-Siskin L, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy with older people. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003.

Drug Brand Name

- Desipramine • Norpramin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landreville P, Landry J, Baillargeon L, et al. Older adults’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(5):P285-P291.

2. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

3. Beck JS. Cognitive conceptualization. In: Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. New York NY: The Guilford Press; 2011:29–45.

4. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1979.

5. Areán PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):293-303.

6. Laidlaw K, Davidson K, Toner H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy vs treatment as usual in the treatment of mild to moderate late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):843-850.

7. Floyd M, Scogin F, McKendree-Smith NL, et al. Cognitive therapy for depression: a comparison of individual psychotherapy and bibliotherapy for depressed older adults. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(2):297-318.

8. Serfaty MA, Haworth D, Blanchard M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed older people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1332-1340.

9. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. How effective are psychotherapeutic and other psychosocial interventions with older adults? A meta-analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7(2):207-243.

10. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):645-657.

11. Gallagher-Thompson D, Hanley-Peterson P, Thompson LW. Maintenance of gains versus relapse following brief psychotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(3):371-374.

12. Thompson LW, Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Comparison of desipramine and cognitive/behavioral therapy in the treatment of elderly outpatients with mild-to-moderate depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):225-240.

13. Dobkin RD, Menza M, Allen LA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1066-1074.

14. Kunik ME, Braun U, Stanley MA, et al. One session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):717-723.

15. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, et al. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(4):P159-P166.

16. Nordhus IH, Pallesen S. Psychological treatment of late-life anxiety: an empirical review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):643-651.

17. Gorenstein EE, Papp LA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in the elderly. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(1):20-25.

18. Barrowclough C, King P, Colville J, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling for anxiety symptoms in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):756-762.

19. Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(2):309-319.

20. Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GP, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(6):403-411.

21. Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):31-40.

22. Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2010;41(1):46-58.

23. Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):24-32.

24. Flint AJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(5):640-649.

25. McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al. Evidence-based psychological treatments for insomnia in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(1):18-27.

26. Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858.

27. Morgan K, Dixon S, Mathers N, et al. Psychological treatment for insomnia in the regulation of long-term hypnotic drug use. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(8):iii iv, 1-68.

28. Nau SD, McCrae CS, Cook KG, et al. Treatment of insomnia in older adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(5):645-672.

29. Rybarczyk B, Stepanski E, Fogg L, et al. A placebo-controlled test of cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1164-1174.

30. Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Gallagher-Thompson D. Comprehensive conceptualization of cognitive behaviour therapy for late life depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2004;32(4):389-399.

31. Thompson LW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and treatment for late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 5):29-37.

Some older patients with depression, anxiety, or insomnia may be reluctant to turn to pharmacotherapy and may prefer psychotherapeutic treatments.1 Evidence has established cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as an effective intervention for several psychiatric disorders and CBT should be considered when treating geriatric patients (Table 1).2

Table 1

Indications for CBT

| Mild to moderate depression. In the case of severe depression, CBT can be combined with pharmacotherapy |

| Anxiety disorders, mixed anxiety states |

| Insomnia—both primary and comorbid with other medical and/or psychiatric conditions |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Research evaluating the efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults was first published in the early 1980s. Since then, research and application of CBT with older adults has expanded to include other psychiatric disorders and researchers have suggested changes to increase the efficacy of CBT for these patients. This article provides:

- an overview of CBT’s efficacy for older adults with depression, anxiety, and insomnia

- modifications to employ when providing CBT to older patients.

The cognitive model of CBT

In the 1970s, Aaron T. Beck, MD, developed CBT while working with depressed patients. Beck’s patients reported thoughts characterized by inaccuracies and distortions in association with their depressed mood. He found these thoughts could be brought to the patient’s conscious attention and modified to improve the patient’s depression. This finding led to the development of CBT.

CBT is based on a cognitive model of the relationship among cognition, emotion, and behavior. Mood and behavior are viewed as determined by a person’s perception and interpretation of events, which manifest as a stream of automatically generated thoughts (Figure).3 These automatic thoughts have their origins in an underlying network of beliefs or schema. Patients with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression typically have frequent automatic thoughts that characteristically lack validity because they arise from dysfunctional beliefs. The therapeutic process consists of helping the patient become aware of his or her internal stream of thoughts when distressed, and to identify and modify the dysfunctional thoughts. Behavioral techniques are used to bring about functional changes in behavior, regulate emotion, and help the cognitive restructuring process. Modifying the patient’s underlying dysfunctional beliefs leads to lasting improvements. In this structured therapy, the therapist and patient work collaboratively to use an approach that features reality testing and experimentation.4

Figure

The cognitive model of CBT

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Source: Adapted from reference 3

Indications for CBT in older adults

Depression. Among psychotherapies used in older adults, CBT has received the most research for late-life depression.5 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found CBT is superior to treatment as usual in depressed adults age ≥60.6 It also has been found to be superior to wait-list control7 and talking as control.6,8 Meta-analyses have shown above-average effect sizes for CBT in treating late-life depression.9,10 A follow-up study found improvement was maintained up to 2 years after CBT, which suggests CBT’s impact is likely to be long lasting.11

Thompson et al12 compared 102 depressed patients age >60 who were treated with CBT alone, desipramine alone, or a combination of the 2. A combination of medication and CBT worked best for severely depressed patients; CBT alone or a combination of CBT and medication worked best for moderately depressed patients.

CBT is an option when treating depressed medically ill older adults. Research indicates that CBT could reduce depression in older patients with Parkinson’s disease13 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14

As patients get older, cognitive impairment with comorbid depression can make treatment challenging. Limited research suggests CBT applied in a modified format that involves caregivers and uses problem solving and behavioral strategies can significantly reduce depression in patients with dementia.15

Anxiety. Researchers have examined the efficacy of variants of CBT in treating older adults with anxiety disorders—commonly, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, subjective anxiety, or a combination of these illnesses.16,17 Randomized trials have supported CBT’s efficacy for older patients with GAD and mixed anxiety states; gains made in CBT were maintained over a 1-year follow-up.18,19 In a meta-analysis of 15 studies using cognitive and behavioral methods of treating anxiety in older patients, Nordhus and Pallesen16 reported a significant effect size of 0.55. In a 2008 meta-analysis that included only RCTs, CBT was superior to wait-list conditions as well as active control conditions in treating anxious older patients.20

However, some research suggests that CBT for GAD may not be as effective for older adults as it is for younger adults. In a study of CBT for GAD in older adults, Stanley et al19 reported smaller effect sizes compared with CBT for younger adults. Researchers have found relatively few differences between CBT and comparison conditions—supportive psychotherapy or active control conditions—in treating GAD in older adults.21 Modified, more effective formats of CBT for GAD in older adults need to be established.22 Mohlman et al23 supplemented standard CBT for late-life GAD with memory and learning aids—weekly reading assignments, graphing exercises to chart mood ratings, reminder phone calls from therapists, and homework compliance requirement. This approach improved the response rate from 40% to 75%.23

Insomnia. Studies have found CBT to be an effective means of treating insomnia in geriatric patients. Although sleep problems occur more frequently among older patients, only 15% of chronic insomnia patients receive treatment; psychotherapy rarely is used.24 CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) should be considered for older adults because managing insomnia with medications may be problematic and these patients may prefer nonpharmacologic treatment.2 CBT-I typically incorporates cognitive strategies with established behavioral techniques, including sleep hygiene education, cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, stimulus control, and/or sleep restriction. The CBT-I multicomponent treatment package meets all criteria to be considered an evidence-based treatment for late-life insomnia.25

RCTs have reported significant improvements in late-life insomnia with CBT-I.26,27 Reviews and meta-analyses have also concluded that cognitive-behavioral treatments are effective for treating insomnia in older adults.25,28 Most insomnia cases in geriatric patients are reported to occur secondary to other medical or psychiatric conditions that are judged as causing the insomnia.25 In these cases, direct treatment of the insomnia usually is delayed or omitted.28 Studies evaluating the efficacy of CBT packages for treating insomnia occurring in conjunction with other medical or psychiatric illnesses have reported significant improvement of insomnia.28,29 Because insomnia frequently occurs in older patients with medical illnesses and psychiatric disorders, CBT-I could be beneficial for such patients.

Good candidates for CBT

Clinical experience indicates that older adults in relatively good health with no significant cognitive decline are good candidates for CBT. These patients tend to comply with their assignments, are interested in applying the learned strategies, and are motivated to read self-help books. CBT’s structured, goal-oriented approach makes it a short-term treatment, which makes it cost effective. Insomnia patients may improve after 6 to 8 CBT-I sessions and patients with anxiety or depression may need to undergo 15 to 20 CBT sessions. Patients age ≥65 have basic Medicare coverage that includes mental health care and psychotherapy.

There are no absolute contraindications for CBT, but the greater the cognitive impairment, the less the patient will benefit from CBT (Table 2). Similarly, severe depression and anxiety might make it difficult for patients to participate meaningfully, although CBT may be incorporated gradually as patients improve with medication. Severe medical illnesses and sensory losses such as visual and hearing loss would make it difficult to carry out CBT effectively.

Table 2

Contraindications for CBT

| High levels of cognitive impairment |

| Severe depression with psychotic features |

| Severe anxiety with high levels of agitation |

| Severe medical illness |

| Sensory losses |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Adapting CBT for older patients

When using CBT with older patients, it is important to keep in mind characteristics that define the geriatric population. Laidlaw et al30 developed a model to help clinicians develop a more appropriate conceptualization of older patients that focuses on significant events and related cognitions associated with physical health, changes in role investments, and interactions with younger generations. It emphasizes the need to explore beliefs about aging viewed through each patient’s socio-cultural lens and examine cognitions in the context of the time period in which the individual has lived.

Losses and transitions. For many older patients, the latter years of life are characterized by losses and transitions.31 According to Thompson,31 these losses and transitions can trigger thoughts of missed opportunities or unresolved relationships and reflection on unachieved goals.31 CBT for older adults should focus on the meaning the patient gives to these losses and transitions. For example, depressed patients could view their retirement as a loss of self worth as they become less productive. CBT can help patients identify ways of thinking about the situation that will enable them to adapt to these losses and transitions.

Changes in cognition. Changes in cognitive functioning with aging are not universal and there’s considerable variability, but it’s important to make appropriate adaptations when needed. Patients may experience a decline in cognitive speed, working memory, selective attention, and fluid intelligence. This would require that information be presented slowly, with frequent repetitions and summaries. Also, it might be helpful to present information in alternate ways and to encourage patients to take notes during sessions. To accommodate for a decline in fluid intelligence, presenting new information in the context of previous experiences will help promote learning. Recordings of important information and conclusions from cognitive restructuring that patients can listen to between sessions could serve as helpful reminders that will help patients progress. Phone prompts or alarms can remind patients to carry out certain therapeutic measures, such as breathing exercises. Caretakers can attend sessions to become familiar with strategies performed during CBT and act as a co-therapist at home; however, their inclusion must be done with the consent of both parties and only if it’s viewed as necessary for the patient’s progress.

Additional strategies. For patients with substantial cognitive decline, cognitive restructuring might not be as effective as behavioral strategies—activity scheduling, graded task assignment, graded exposure, and rehearsals. Because older adults often have strengthened dysfunctional beliefs over a long time, modifying them takes longer, which is why the tapering process usually takes longer for older patients than for younger patients. The lengthier tapering ensures learning is well established and the process of modifying dysfunctional beliefs to functional beliefs continues. Collaborating with other professionals—physicians, social workers, and case managers—will help ensure a shared care process in which common goals are met.

The websites of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, American Psychological Association, and Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies can help clinicians who do not offer CBT to locate a qualified therapist for their patients (Related Resources).

- Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

- American Psychological Association. www.apa.org.

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. www.abct.org.

- Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Dick-Siskin L, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy with older people. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003.

Drug Brand Name

- Desipramine • Norpramin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Some older patients with depression, anxiety, or insomnia may be reluctant to turn to pharmacotherapy and may prefer psychotherapeutic treatments.1 Evidence has established cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) as an effective intervention for several psychiatric disorders and CBT should be considered when treating geriatric patients (Table 1).2

Table 1

Indications for CBT

| Mild to moderate depression. In the case of severe depression, CBT can be combined with pharmacotherapy |

| Anxiety disorders, mixed anxiety states |

| Insomnia—both primary and comorbid with other medical and/or psychiatric conditions |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Research evaluating the efficacy of CBT for depression in older adults was first published in the early 1980s. Since then, research and application of CBT with older adults has expanded to include other psychiatric disorders and researchers have suggested changes to increase the efficacy of CBT for these patients. This article provides:

- an overview of CBT’s efficacy for older adults with depression, anxiety, and insomnia

- modifications to employ when providing CBT to older patients.

The cognitive model of CBT

In the 1970s, Aaron T. Beck, MD, developed CBT while working with depressed patients. Beck’s patients reported thoughts characterized by inaccuracies and distortions in association with their depressed mood. He found these thoughts could be brought to the patient’s conscious attention and modified to improve the patient’s depression. This finding led to the development of CBT.

CBT is based on a cognitive model of the relationship among cognition, emotion, and behavior. Mood and behavior are viewed as determined by a person’s perception and interpretation of events, which manifest as a stream of automatically generated thoughts (Figure).3 These automatic thoughts have their origins in an underlying network of beliefs or schema. Patients with psychiatric disorders such as anxiety and depression typically have frequent automatic thoughts that characteristically lack validity because they arise from dysfunctional beliefs. The therapeutic process consists of helping the patient become aware of his or her internal stream of thoughts when distressed, and to identify and modify the dysfunctional thoughts. Behavioral techniques are used to bring about functional changes in behavior, regulate emotion, and help the cognitive restructuring process. Modifying the patient’s underlying dysfunctional beliefs leads to lasting improvements. In this structured therapy, the therapist and patient work collaboratively to use an approach that features reality testing and experimentation.4

Figure

The cognitive model of CBT

CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy

Source: Adapted from reference 3

Indications for CBT in older adults

Depression. Among psychotherapies used in older adults, CBT has received the most research for late-life depression.5 Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found CBT is superior to treatment as usual in depressed adults age ≥60.6 It also has been found to be superior to wait-list control7 and talking as control.6,8 Meta-analyses have shown above-average effect sizes for CBT in treating late-life depression.9,10 A follow-up study found improvement was maintained up to 2 years after CBT, which suggests CBT’s impact is likely to be long lasting.11

Thompson et al12 compared 102 depressed patients age >60 who were treated with CBT alone, desipramine alone, or a combination of the 2. A combination of medication and CBT worked best for severely depressed patients; CBT alone or a combination of CBT and medication worked best for moderately depressed patients.

CBT is an option when treating depressed medically ill older adults. Research indicates that CBT could reduce depression in older patients with Parkinson’s disease13 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.14

As patients get older, cognitive impairment with comorbid depression can make treatment challenging. Limited research suggests CBT applied in a modified format that involves caregivers and uses problem solving and behavioral strategies can significantly reduce depression in patients with dementia.15

Anxiety. Researchers have examined the efficacy of variants of CBT in treating older adults with anxiety disorders—commonly, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, agoraphobia, subjective anxiety, or a combination of these illnesses.16,17 Randomized trials have supported CBT’s efficacy for older patients with GAD and mixed anxiety states; gains made in CBT were maintained over a 1-year follow-up.18,19 In a meta-analysis of 15 studies using cognitive and behavioral methods of treating anxiety in older patients, Nordhus and Pallesen16 reported a significant effect size of 0.55. In a 2008 meta-analysis that included only RCTs, CBT was superior to wait-list conditions as well as active control conditions in treating anxious older patients.20

However, some research suggests that CBT for GAD may not be as effective for older adults as it is for younger adults. In a study of CBT for GAD in older adults, Stanley et al19 reported smaller effect sizes compared with CBT for younger adults. Researchers have found relatively few differences between CBT and comparison conditions—supportive psychotherapy or active control conditions—in treating GAD in older adults.21 Modified, more effective formats of CBT for GAD in older adults need to be established.22 Mohlman et al23 supplemented standard CBT for late-life GAD with memory and learning aids—weekly reading assignments, graphing exercises to chart mood ratings, reminder phone calls from therapists, and homework compliance requirement. This approach improved the response rate from 40% to 75%.23

Insomnia. Studies have found CBT to be an effective means of treating insomnia in geriatric patients. Although sleep problems occur more frequently among older patients, only 15% of chronic insomnia patients receive treatment; psychotherapy rarely is used.24 CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) should be considered for older adults because managing insomnia with medications may be problematic and these patients may prefer nonpharmacologic treatment.2 CBT-I typically incorporates cognitive strategies with established behavioral techniques, including sleep hygiene education, cognitive restructuring, relaxation training, stimulus control, and/or sleep restriction. The CBT-I multicomponent treatment package meets all criteria to be considered an evidence-based treatment for late-life insomnia.25

RCTs have reported significant improvements in late-life insomnia with CBT-I.26,27 Reviews and meta-analyses have also concluded that cognitive-behavioral treatments are effective for treating insomnia in older adults.25,28 Most insomnia cases in geriatric patients are reported to occur secondary to other medical or psychiatric conditions that are judged as causing the insomnia.25 In these cases, direct treatment of the insomnia usually is delayed or omitted.28 Studies evaluating the efficacy of CBT packages for treating insomnia occurring in conjunction with other medical or psychiatric illnesses have reported significant improvement of insomnia.28,29 Because insomnia frequently occurs in older patients with medical illnesses and psychiatric disorders, CBT-I could be beneficial for such patients.

Good candidates for CBT

Clinical experience indicates that older adults in relatively good health with no significant cognitive decline are good candidates for CBT. These patients tend to comply with their assignments, are interested in applying the learned strategies, and are motivated to read self-help books. CBT’s structured, goal-oriented approach makes it a short-term treatment, which makes it cost effective. Insomnia patients may improve after 6 to 8 CBT-I sessions and patients with anxiety or depression may need to undergo 15 to 20 CBT sessions. Patients age ≥65 have basic Medicare coverage that includes mental health care and psychotherapy.

There are no absolute contraindications for CBT, but the greater the cognitive impairment, the less the patient will benefit from CBT (Table 2). Similarly, severe depression and anxiety might make it difficult for patients to participate meaningfully, although CBT may be incorporated gradually as patients improve with medication. Severe medical illnesses and sensory losses such as visual and hearing loss would make it difficult to carry out CBT effectively.

Table 2

Contraindications for CBT

| High levels of cognitive impairment |

| Severe depression with psychotic features |

| Severe anxiety with high levels of agitation |

| Severe medical illness |

| Sensory losses |

| CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy |

Adapting CBT for older patients

When using CBT with older patients, it is important to keep in mind characteristics that define the geriatric population. Laidlaw et al30 developed a model to help clinicians develop a more appropriate conceptualization of older patients that focuses on significant events and related cognitions associated with physical health, changes in role investments, and interactions with younger generations. It emphasizes the need to explore beliefs about aging viewed through each patient’s socio-cultural lens and examine cognitions in the context of the time period in which the individual has lived.

Losses and transitions. For many older patients, the latter years of life are characterized by losses and transitions.31 According to Thompson,31 these losses and transitions can trigger thoughts of missed opportunities or unresolved relationships and reflection on unachieved goals.31 CBT for older adults should focus on the meaning the patient gives to these losses and transitions. For example, depressed patients could view their retirement as a loss of self worth as they become less productive. CBT can help patients identify ways of thinking about the situation that will enable them to adapt to these losses and transitions.

Changes in cognition. Changes in cognitive functioning with aging are not universal and there’s considerable variability, but it’s important to make appropriate adaptations when needed. Patients may experience a decline in cognitive speed, working memory, selective attention, and fluid intelligence. This would require that information be presented slowly, with frequent repetitions and summaries. Also, it might be helpful to present information in alternate ways and to encourage patients to take notes during sessions. To accommodate for a decline in fluid intelligence, presenting new information in the context of previous experiences will help promote learning. Recordings of important information and conclusions from cognitive restructuring that patients can listen to between sessions could serve as helpful reminders that will help patients progress. Phone prompts or alarms can remind patients to carry out certain therapeutic measures, such as breathing exercises. Caretakers can attend sessions to become familiar with strategies performed during CBT and act as a co-therapist at home; however, their inclusion must be done with the consent of both parties and only if it’s viewed as necessary for the patient’s progress.

Additional strategies. For patients with substantial cognitive decline, cognitive restructuring might not be as effective as behavioral strategies—activity scheduling, graded task assignment, graded exposure, and rehearsals. Because older adults often have strengthened dysfunctional beliefs over a long time, modifying them takes longer, which is why the tapering process usually takes longer for older patients than for younger patients. The lengthier tapering ensures learning is well established and the process of modifying dysfunctional beliefs to functional beliefs continues. Collaborating with other professionals—physicians, social workers, and case managers—will help ensure a shared care process in which common goals are met.

The websites of the Academy of Cognitive Therapy, American Psychological Association, and Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies can help clinicians who do not offer CBT to locate a qualified therapist for their patients (Related Resources).

- Academy of Cognitive Therapy. www.academyofct.org.

- American Psychological Association. www.apa.org.

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. www.abct.org.

- Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Dick-Siskin L, et al. Cognitive behaviour therapy with older people. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2003.

Drug Brand Name

- Desipramine • Norpramin

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Landreville P, Landry J, Baillargeon L, et al. Older adults’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(5):P285-P291.

2. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

3. Beck JS. Cognitive conceptualization. In: Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. New York NY: The Guilford Press; 2011:29–45.

4. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1979.

5. Areán PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):293-303.

6. Laidlaw K, Davidson K, Toner H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy vs treatment as usual in the treatment of mild to moderate late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):843-850.

7. Floyd M, Scogin F, McKendree-Smith NL, et al. Cognitive therapy for depression: a comparison of individual psychotherapy and bibliotherapy for depressed older adults. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(2):297-318.

8. Serfaty MA, Haworth D, Blanchard M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed older people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1332-1340.

9. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. How effective are psychotherapeutic and other psychosocial interventions with older adults? A meta-analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7(2):207-243.

10. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):645-657.

11. Gallagher-Thompson D, Hanley-Peterson P, Thompson LW. Maintenance of gains versus relapse following brief psychotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(3):371-374.

12. Thompson LW, Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Comparison of desipramine and cognitive/behavioral therapy in the treatment of elderly outpatients with mild-to-moderate depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):225-240.

13. Dobkin RD, Menza M, Allen LA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1066-1074.

14. Kunik ME, Braun U, Stanley MA, et al. One session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):717-723.

15. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, et al. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(4):P159-P166.

16. Nordhus IH, Pallesen S. Psychological treatment of late-life anxiety: an empirical review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):643-651.

17. Gorenstein EE, Papp LA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in the elderly. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(1):20-25.

18. Barrowclough C, King P, Colville J, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling for anxiety symptoms in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):756-762.

19. Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(2):309-319.

20. Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GP, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(6):403-411.

21. Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):31-40.

22. Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2010;41(1):46-58.

23. Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):24-32.

24. Flint AJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(5):640-649.

25. McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al. Evidence-based psychological treatments for insomnia in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(1):18-27.

26. Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858.

27. Morgan K, Dixon S, Mathers N, et al. Psychological treatment for insomnia in the regulation of long-term hypnotic drug use. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(8):iii iv, 1-68.

28. Nau SD, McCrae CS, Cook KG, et al. Treatment of insomnia in older adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(5):645-672.

29. Rybarczyk B, Stepanski E, Fogg L, et al. A placebo-controlled test of cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1164-1174.

30. Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Gallagher-Thompson D. Comprehensive conceptualization of cognitive behaviour therapy for late life depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2004;32(4):389-399.

31. Thompson LW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and treatment for late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 5):29-37.

1. Landreville P, Landry J, Baillargeon L, et al. Older adults’ acceptance of psychological and pharmacological treatments for depression. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(5):P285-P291.

2. Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: controversies and evidence. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52:685-716.

3. Beck JS. Cognitive conceptualization. In: Cognitive therapy: basics and beyond. 2nd ed. New York NY: The Guilford Press; 2011:29–45.

4. Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, et al. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1979.

5. Areán PA, Cook BL. Psychotherapy and combined psychotherapy/pharmacotherapy for late-life depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):293-303.

6. Laidlaw K, Davidson K, Toner H, et al. A randomised controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy vs treatment as usual in the treatment of mild to moderate late-life depression. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(8):843-850.

7. Floyd M, Scogin F, McKendree-Smith NL, et al. Cognitive therapy for depression: a comparison of individual psychotherapy and bibliotherapy for depressed older adults. Behavior Modification. 2004;28(2):297-318.

8. Serfaty MA, Haworth D, Blanchard M, et al. Clinical effectiveness of individual cognitive behavioral therapy for depressed older people in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(12):1332-1340.

9. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. How effective are psychotherapeutic and other psychosocial interventions with older adults? A meta-analysis. J Ment Health Aging. 2001;7(2):207-243.

10. Pinquart M, Duberstein PR, Lyness JM. Effects of psychotherapy and other behavioral interventions on clinically depressed older adults: a meta-analysis. Aging Ment Health. 2007;11(6):645-657.

11. Gallagher-Thompson D, Hanley-Peterson P, Thompson LW. Maintenance of gains versus relapse following brief psychotherapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(3):371-374.

12. Thompson LW, Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, et al. Comparison of desipramine and cognitive/behavioral therapy in the treatment of elderly outpatients with mild-to-moderate depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9(3):225-240.

13. Dobkin RD, Menza M, Allen LA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in Parkinson’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1066-1074.

14. Kunik ME, Braun U, Stanley MA, et al. One session cognitive behavioural therapy for elderly patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Psychol Med. 2001;31(4):717-723.

15. Teri L, Logsdon RG, Uomoto J, et al. Behavioral treatment of depression in dementia patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(4):P159-P166.

16. Nordhus IH, Pallesen S. Psychological treatment of late-life anxiety: an empirical review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):643-651.

17. Gorenstein EE, Papp LA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety in the elderly. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(1):20-25.

18. Barrowclough C, King P, Colville J, et al. A randomized trial of the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling for anxiety symptoms in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69(5):756-762.

19. Stanley MA, Beck JG, Novy DM, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of late-life generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(2):309-319.

20. Hendriks GJ, Oude Voshaar RC, Keijsers GP, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for late-life anxiety disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;117(6):403-411.

21. Wetherell JL, Gatz M, Craske MG. Treatment of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(1):31-40.

22. Dugas MJ, Brillon P, Savard P, et al. A randomized clinical trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy and applied relaxation for adults with generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2010;41(1):46-58.

23. Mohlman J, Gorenstein EE, Kleber M, et al. Standard and enhanced cognitive-behavior therapy for late-life generalized anxiety disorder: two pilot investigations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;11(1):24-32.

24. Flint AJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of anxiety disorders in the elderly. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(5):640-649.

25. McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Teri L, et al. Evidence-based psychological treatments for insomnia in older adults. Psychol Aging. 2007;22(1):18-27.

26. Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851-2858.

27. Morgan K, Dixon S, Mathers N, et al. Psychological treatment for insomnia in the regulation of long-term hypnotic drug use. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(8):iii iv, 1-68.

28. Nau SD, McCrae CS, Cook KG, et al. Treatment of insomnia in older adults. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(5):645-672.

29. Rybarczyk B, Stepanski E, Fogg L, et al. A placebo-controlled test of cognitive-behavioral therapy for comorbid insomnia in older adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73(6):1164-1174.

30. Laidlaw K, Thompson LW, Gallagher-Thompson D. Comprehensive conceptualization of cognitive behaviour therapy for late life depression. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2004;32(4):389-399.

31. Thompson LW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and treatment for late-life depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 5):29-37.

A taste for the unusual

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Nauseous and full

Ms. O, age 48, presents to the emergency department reporting a 3-day history of vomiting approximately 5 minutes after consuming solids or liquids. She’s had 10 vomiting episodes, which were associated with “fullness” and an “aching” sensation she rates as 6 on a 10-point scale pain scale that is diffuse over the upper epigastric area, with no palliative factors. Ms. O has not had a bowel movement for 3 days and her last menstrual period was 8 days ago. She is taking lorazepam, 1 mg/d. Her medical and psychiatric history includes anxiety, depression, personality disorder symptoms of affective dysregulation, obesity (270 lbs; medium height), and pica. She was 352 lbs when she underwent a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 2 years ago. One year earlier, she had a laparoscopic gastric bezoar removal and an incisional hernia repair. Ms. O had no pica-related surgeries before undergoing gastric bypass surgery.

Ms. O denies shortness of breath, chest pain, allergies, smoking, or alcohol abuse, but reports uncontrollable cravings for paper products, specifically cardboard, which she describes as “just so delicious.” This craving led her to consume large amounts of cardboard and newspaper in the days before she began vomiting.

What may be causing Ms. O’s pica symptoms?

- iron deficiency anemia

- complications from gastric bypass surgery

- personality disorder

- generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for pica include the persistent eating of non-nutritive substances for ≥1 month that is inappropriate for the level of a person’s development and not an acceptable part of one’s culture.1 If pica occurs with other mental disorders, it must be severe enough to indicate further clinical assessment to receive a separate diagnosis. Often associated with pregnancy, iron deficiency anemia, early development, and mental retardation, pica has been observed in post-gastric bypass surgery patients, all of whom presented with pagophagia (compulsive ice eating), and in one case was associated with a bezoar causing obstruction of the GI tract.1,2 With the dramatic increase in gastric bypass surgery and the required presurgical mental health evaluation, the consequences of failing to screen patients for pica behaviors can be devastating.