User login

Anti-TNF Resistant Crohn's Disease May Respond to Ustekinumab

Ustekinumab induced a clinical response in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease that was resistant to tumor necrosis factor antagonists, in a phase IIb clinical trial published online Oct. 17 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

However, the agent did not improve remission rates, compared with placebo, said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Diego, La Jolla, and his associates.

"A sizable proportion" of patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease do not respond to TNF antagonists, have an unsustained response, or must discontinue the medications because of adverse effects. After ustekinumab showed efficacy in such patients in a phase IIa clinical study, Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues performed a 36-week double-blind phase II2b trial in 526 adults at 153 medical centers in 12 countries.

Ustekinumab, a human IgG monoclonal antibody that inhibits the receptors for interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 on T cells, natural killer cells, and antigen-presenting cells, has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in plaque psoriasis. This clinical trial was sponsored by an affiliate of the manufacturer, Janssen Biotech.

During an 8-week induction phase, the study subjects were randomly assigned to receive intravenous placebo (132 patients) or ustekinumab in 1-mg/kg (131 patients), 3-mg/kg (132 patients), or 6-mg/kg (131 patients) doses. Then, during weeks 8-36, the study subjects who showed a response to induction therapy and those who did not show a response were separately randomized to receive either subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) or placebo at week 8 and week 16, as maintenance therapy.

Treatment efficacy was assessed at week 22, and patients were followed through week 36 for a safety analysis. A total of 36.1% of the subjects discontinued the study before week 36.

The primary end point was a clinical response, defined as a decrease of 100 points or more on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score.

A total of 39.7% of patients receiving the 6-mg induction dose showed a clinical response, which was significantly greater than the 23.5% of patients receiving placebo, the investigators said (New Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1203572]).

A greater number of patients receiving the lower doses of ustekinumab than receiving placebo showed a clinical response, but the differences between these low-dose groups and the placebo group did not reach statistical significance.

The 6-mg/kg dose was effective across most demographic and disease characteristics, judging from the findings of a subgroup analysis. It was consistently effective in patients who had failed on their first attempt at therapy with TNF antagonists, patients who had failed on two or more TNF antagonists, and patients who had only had a transient response to TNF antagonists.

However, rates of clinical remission did not differ significantly between patients receiving ustekinumab and those receiving placebo, Dr. Sandborn and his associates said.

At all follow-up visits, the proportion of patients who had a 70-point clinical response was significantly higher, the reductions in mean CDAI scores were significantly greater, and the reductions in C-reactive protein levels were significantly greater in patients receiving 6 mg per kg of ustekinumab than in the placebo group.

As a maintenance therapy, 90 mg of subcutaneous ustekinumab appeared to be effective in patients who responded to the induction dose of the agent. The proportion of patients who showed a clinical response at week 22 was 69.4% in those receiving maintenance ustekinumab, significantly greater than the 42.5% response rate among those receiving maintenance placebo.

Among patients who responded to induction-phase ustekinumab, 41.7% of those who also received maintenance ustekinumab achieved clinical remission at week 22, compared with only 27.4% of those who received maintenance placebo.

Similarly, among patients who showed a response to induction ustekinumab, reductions in both CDAI scores and CRP levels were sustained if they continued on maintenance ustekinumab but were not sustained if they continued on placebo for the maintenance period.

However, patients who did not show a response to induction ustekinumab also did not benefit from additional ustekinumab in the maintenance phase of the study.

The results of the safety analysis were "somewhat limited" by the small sample size and the short duration of treatment. No deaths, serious opportunistic infections, or major adverse cardiovascular events were reported, "but large studies of longer duration are needed to assess uncommon adverse events," the investigators said.

Of note, one patient receiving ustekinumab as both induction and maintenance therapy developed a basal cell carcinoma. Among patients taking ustekinumab in the induction phase of the study, six developed serious infections: Clostridium difficile, viral gastroenteritis, UTI, anal abscess, vaginal abscess, and a staph infection of a central catheter.

This study was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development; Janssen Biotech makes ustekinumab. Dr. Sandborn and his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Ustekinumab induced a clinical response in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease that was resistant to tumor necrosis factor antagonists, in a phase IIb clinical trial published online Oct. 17 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

However, the agent did not improve remission rates, compared with placebo, said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Diego, La Jolla, and his associates.

"A sizable proportion" of patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease do not respond to TNF antagonists, have an unsustained response, or must discontinue the medications because of adverse effects. After ustekinumab showed efficacy in such patients in a phase IIa clinical study, Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues performed a 36-week double-blind phase II2b trial in 526 adults at 153 medical centers in 12 countries.

Ustekinumab, a human IgG monoclonal antibody that inhibits the receptors for interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 on T cells, natural killer cells, and antigen-presenting cells, has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in plaque psoriasis. This clinical trial was sponsored by an affiliate of the manufacturer, Janssen Biotech.

During an 8-week induction phase, the study subjects were randomly assigned to receive intravenous placebo (132 patients) or ustekinumab in 1-mg/kg (131 patients), 3-mg/kg (132 patients), or 6-mg/kg (131 patients) doses. Then, during weeks 8-36, the study subjects who showed a response to induction therapy and those who did not show a response were separately randomized to receive either subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) or placebo at week 8 and week 16, as maintenance therapy.

Treatment efficacy was assessed at week 22, and patients were followed through week 36 for a safety analysis. A total of 36.1% of the subjects discontinued the study before week 36.

The primary end point was a clinical response, defined as a decrease of 100 points or more on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score.

A total of 39.7% of patients receiving the 6-mg induction dose showed a clinical response, which was significantly greater than the 23.5% of patients receiving placebo, the investigators said (New Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1203572]).

A greater number of patients receiving the lower doses of ustekinumab than receiving placebo showed a clinical response, but the differences between these low-dose groups and the placebo group did not reach statistical significance.

The 6-mg/kg dose was effective across most demographic and disease characteristics, judging from the findings of a subgroup analysis. It was consistently effective in patients who had failed on their first attempt at therapy with TNF antagonists, patients who had failed on two or more TNF antagonists, and patients who had only had a transient response to TNF antagonists.

However, rates of clinical remission did not differ significantly between patients receiving ustekinumab and those receiving placebo, Dr. Sandborn and his associates said.

At all follow-up visits, the proportion of patients who had a 70-point clinical response was significantly higher, the reductions in mean CDAI scores were significantly greater, and the reductions in C-reactive protein levels were significantly greater in patients receiving 6 mg per kg of ustekinumab than in the placebo group.

As a maintenance therapy, 90 mg of subcutaneous ustekinumab appeared to be effective in patients who responded to the induction dose of the agent. The proportion of patients who showed a clinical response at week 22 was 69.4% in those receiving maintenance ustekinumab, significantly greater than the 42.5% response rate among those receiving maintenance placebo.

Among patients who responded to induction-phase ustekinumab, 41.7% of those who also received maintenance ustekinumab achieved clinical remission at week 22, compared with only 27.4% of those who received maintenance placebo.

Similarly, among patients who showed a response to induction ustekinumab, reductions in both CDAI scores and CRP levels were sustained if they continued on maintenance ustekinumab but were not sustained if they continued on placebo for the maintenance period.

However, patients who did not show a response to induction ustekinumab also did not benefit from additional ustekinumab in the maintenance phase of the study.

The results of the safety analysis were "somewhat limited" by the small sample size and the short duration of treatment. No deaths, serious opportunistic infections, or major adverse cardiovascular events were reported, "but large studies of longer duration are needed to assess uncommon adverse events," the investigators said.

Of note, one patient receiving ustekinumab as both induction and maintenance therapy developed a basal cell carcinoma. Among patients taking ustekinumab in the induction phase of the study, six developed serious infections: Clostridium difficile, viral gastroenteritis, UTI, anal abscess, vaginal abscess, and a staph infection of a central catheter.

This study was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development; Janssen Biotech makes ustekinumab. Dr. Sandborn and his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Ustekinumab induced a clinical response in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease that was resistant to tumor necrosis factor antagonists, in a phase IIb clinical trial published online Oct. 17 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

However, the agent did not improve remission rates, compared with placebo, said Dr. William J. Sandborn, professor of medicine and chief of the division of gastroenterology at the University of California San Diego, La Jolla, and his associates.

"A sizable proportion" of patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease do not respond to TNF antagonists, have an unsustained response, or must discontinue the medications because of adverse effects. After ustekinumab showed efficacy in such patients in a phase IIa clinical study, Dr. Sandborn and his colleagues performed a 36-week double-blind phase II2b trial in 526 adults at 153 medical centers in 12 countries.

Ustekinumab, a human IgG monoclonal antibody that inhibits the receptors for interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 on T cells, natural killer cells, and antigen-presenting cells, has Food and Drug Administration approval for use in plaque psoriasis. This clinical trial was sponsored by an affiliate of the manufacturer, Janssen Biotech.

During an 8-week induction phase, the study subjects were randomly assigned to receive intravenous placebo (132 patients) or ustekinumab in 1-mg/kg (131 patients), 3-mg/kg (132 patients), or 6-mg/kg (131 patients) doses. Then, during weeks 8-36, the study subjects who showed a response to induction therapy and those who did not show a response were separately randomized to receive either subcutaneous ustekinumab (90 mg) or placebo at week 8 and week 16, as maintenance therapy.

Treatment efficacy was assessed at week 22, and patients were followed through week 36 for a safety analysis. A total of 36.1% of the subjects discontinued the study before week 36.

The primary end point was a clinical response, defined as a decrease of 100 points or more on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) score.

A total of 39.7% of patients receiving the 6-mg induction dose showed a clinical response, which was significantly greater than the 23.5% of patients receiving placebo, the investigators said (New Engl. J. Med. 2012 [doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1203572]).

A greater number of patients receiving the lower doses of ustekinumab than receiving placebo showed a clinical response, but the differences between these low-dose groups and the placebo group did not reach statistical significance.

The 6-mg/kg dose was effective across most demographic and disease characteristics, judging from the findings of a subgroup analysis. It was consistently effective in patients who had failed on their first attempt at therapy with TNF antagonists, patients who had failed on two or more TNF antagonists, and patients who had only had a transient response to TNF antagonists.

However, rates of clinical remission did not differ significantly between patients receiving ustekinumab and those receiving placebo, Dr. Sandborn and his associates said.

At all follow-up visits, the proportion of patients who had a 70-point clinical response was significantly higher, the reductions in mean CDAI scores were significantly greater, and the reductions in C-reactive protein levels were significantly greater in patients receiving 6 mg per kg of ustekinumab than in the placebo group.

As a maintenance therapy, 90 mg of subcutaneous ustekinumab appeared to be effective in patients who responded to the induction dose of the agent. The proportion of patients who showed a clinical response at week 22 was 69.4% in those receiving maintenance ustekinumab, significantly greater than the 42.5% response rate among those receiving maintenance placebo.

Among patients who responded to induction-phase ustekinumab, 41.7% of those who also received maintenance ustekinumab achieved clinical remission at week 22, compared with only 27.4% of those who received maintenance placebo.

Similarly, among patients who showed a response to induction ustekinumab, reductions in both CDAI scores and CRP levels were sustained if they continued on maintenance ustekinumab but were not sustained if they continued on placebo for the maintenance period.

However, patients who did not show a response to induction ustekinumab also did not benefit from additional ustekinumab in the maintenance phase of the study.

The results of the safety analysis were "somewhat limited" by the small sample size and the short duration of treatment. No deaths, serious opportunistic infections, or major adverse cardiovascular events were reported, "but large studies of longer duration are needed to assess uncommon adverse events," the investigators said.

Of note, one patient receiving ustekinumab as both induction and maintenance therapy developed a basal cell carcinoma. Among patients taking ustekinumab in the induction phase of the study, six developed serious infections: Clostridium difficile, viral gastroenteritis, UTI, anal abscess, vaginal abscess, and a staph infection of a central catheter.

This study was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development; Janssen Biotech makes ustekinumab. Dr. Sandborn and his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Major Finding: Of patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease who received ustekinumab (6 mg/kg), 39.7% showed a decrease of 100 points or more in CDAI score, compared with 23.5% of those who received placebo.

Data Source: The data come from a 36-week,international phase IIb randomized clinical trial comparing 3 doses of ustekinumab with placebo in 526 adults who had refractory Crohn’ disease.

Disclosures: This study was sponsored by Janssen Research and Development; Janssen Biotech makes ustekinumab. Dr. Sandborn and his associates reported numerous ties to industry sources.

Get the Government to Fund Your ACO Start-Up Costs

There seems to be a cruel irony at work: It is generally recognized that a primary care physician–based accountable care organization stands the greatest chance of successfully squeezing the waste out of our health care system – yet that same system has historically deprived primary care of the means to finance an ACO.

Worse, most of the payments that are necessary to fund and sustain ACOs are deferred for more than a year, because they come from savings created during the prior year. It is the proverbial "you can’t get there from here" problem.

How do we avoid this "Catch-22," in which the primary care–driven ACO model is best suited to meet the goals of ACOs but often is least able to afford the costs of creating ACOs?

The answer may be the federal government. There are several viable options available to have the government effectively fund 100% of your ACO start-up costs.

Consider the following:

• Meaningful use incentives. Why not have the government pay for your ACO technology platform? If you think ahead, the health information exchange you will want for your ACO will likely qualify you for stage 2 and stage 3 meaningful use incentives. You can earn up to $44,000 over 5 years from Medicare, or up to $63,750 over 6 years from Medicaid. Instead of data being a burden under fee for service, access to and exchange capability of data will be a huge asset.

You will need to make these investments anyway. If you have your ACO game plan in place, much of what you and your colleagues do to meet the meaningful use criteria can be used to fund your ACO.

• Advance payment model program. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services apparently recognized the "you can’t get there from here" dilemma by creating the advance payment model program. Physician-run ACOs in rural areas have been singled out to receive enough up-front funding to completely pay for the development and implementation of the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACO until shared savings payments kick in.

In addition to the MSSP application, ACOs that wish to receive advance funding from the CMS Innovation Center must also complete the advance payment model application. The advance payment model is open to only two types of ACOs: ACOs that do not include any inpatient facilities and have less than $50 million in total annual revenue; and ACOs in which the only inpatient facilities are critical access hospitals and/or Medicare low-volume rural hospitals, and that have less than $80 million in total annual revenue. ACOs that are co-owned with a health plan will be ineligible, regardless of whether they also fall into one of the above categories.

The advance payment model application consists of two primary sections: the ACO’s financial characteristics; and the ACO’s investment plan.

With respect to the financial characteristics, the ACO will need to list the total annual revenue and total Medicaid revenue for each ACO participant during the preceding 3 years. The information submitted by the ACO will need to be based on either federal tax returns or audited financial statements.

The second key section of the advance payment model application is the ACO investment plan. The ACO must explain how it intends to use the advance payment funds awarded from CMS.

Specifically, the investment plan must include:

• A description of the types of staffing and infrastructure that the ACO will acquire and/or expand using the funding available through the advance payment model.

• The timing of such acquisitions or expansions, and the estimated unit costs.

• A description of how such investments build on staff and infrastructure the ACO already has or plans to acquire through its own upcoming investments.

• An explanation of how each investment will support the ACO in achieving the three-part aim of better health, better health care, and lower per capita costs for Medicare beneficiaries.

The advance payment model money may not be renewed once the initial $1 billion budgeted amount is exhausted. But if the results and return on investment are as powerful as predicted for the targeted ACOs, this could be viewed as a sound investment by CMS.

At current levels, an ACO will receive an up-front fixed amount of $250,000, a variable $36/member, and then $8/member per month. This will be repaid if there are ACO shared savings later on.

Beyond the dollars and cents impact, the APM program is vivid evidence for primary care physicians of just how promising CMS believes physician-directed ACOs are.

Primary care physicians are starting to understand the professional and financial rewards behind ACOs. They should not be dismayed by lack of funding. The payers know that funding these ACOs is a smart "investment" in reforming our inefficient and wasteful current system.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

There seems to be a cruel irony at work: It is generally recognized that a primary care physician–based accountable care organization stands the greatest chance of successfully squeezing the waste out of our health care system – yet that same system has historically deprived primary care of the means to finance an ACO.

Worse, most of the payments that are necessary to fund and sustain ACOs are deferred for more than a year, because they come from savings created during the prior year. It is the proverbial "you can’t get there from here" problem.

How do we avoid this "Catch-22," in which the primary care–driven ACO model is best suited to meet the goals of ACOs but often is least able to afford the costs of creating ACOs?

The answer may be the federal government. There are several viable options available to have the government effectively fund 100% of your ACO start-up costs.

Consider the following:

• Meaningful use incentives. Why not have the government pay for your ACO technology platform? If you think ahead, the health information exchange you will want for your ACO will likely qualify you for stage 2 and stage 3 meaningful use incentives. You can earn up to $44,000 over 5 years from Medicare, or up to $63,750 over 6 years from Medicaid. Instead of data being a burden under fee for service, access to and exchange capability of data will be a huge asset.

You will need to make these investments anyway. If you have your ACO game plan in place, much of what you and your colleagues do to meet the meaningful use criteria can be used to fund your ACO.

• Advance payment model program. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services apparently recognized the "you can’t get there from here" dilemma by creating the advance payment model program. Physician-run ACOs in rural areas have been singled out to receive enough up-front funding to completely pay for the development and implementation of the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACO until shared savings payments kick in.

In addition to the MSSP application, ACOs that wish to receive advance funding from the CMS Innovation Center must also complete the advance payment model application. The advance payment model is open to only two types of ACOs: ACOs that do not include any inpatient facilities and have less than $50 million in total annual revenue; and ACOs in which the only inpatient facilities are critical access hospitals and/or Medicare low-volume rural hospitals, and that have less than $80 million in total annual revenue. ACOs that are co-owned with a health plan will be ineligible, regardless of whether they also fall into one of the above categories.

The advance payment model application consists of two primary sections: the ACO’s financial characteristics; and the ACO’s investment plan.

With respect to the financial characteristics, the ACO will need to list the total annual revenue and total Medicaid revenue for each ACO participant during the preceding 3 years. The information submitted by the ACO will need to be based on either federal tax returns or audited financial statements.

The second key section of the advance payment model application is the ACO investment plan. The ACO must explain how it intends to use the advance payment funds awarded from CMS.

Specifically, the investment plan must include:

• A description of the types of staffing and infrastructure that the ACO will acquire and/or expand using the funding available through the advance payment model.

• The timing of such acquisitions or expansions, and the estimated unit costs.

• A description of how such investments build on staff and infrastructure the ACO already has or plans to acquire through its own upcoming investments.

• An explanation of how each investment will support the ACO in achieving the three-part aim of better health, better health care, and lower per capita costs for Medicare beneficiaries.

The advance payment model money may not be renewed once the initial $1 billion budgeted amount is exhausted. But if the results and return on investment are as powerful as predicted for the targeted ACOs, this could be viewed as a sound investment by CMS.

At current levels, an ACO will receive an up-front fixed amount of $250,000, a variable $36/member, and then $8/member per month. This will be repaid if there are ACO shared savings later on.

Beyond the dollars and cents impact, the APM program is vivid evidence for primary care physicians of just how promising CMS believes physician-directed ACOs are.

Primary care physicians are starting to understand the professional and financial rewards behind ACOs. They should not be dismayed by lack of funding. The payers know that funding these ACOs is a smart "investment" in reforming our inefficient and wasteful current system.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

There seems to be a cruel irony at work: It is generally recognized that a primary care physician–based accountable care organization stands the greatest chance of successfully squeezing the waste out of our health care system – yet that same system has historically deprived primary care of the means to finance an ACO.

Worse, most of the payments that are necessary to fund and sustain ACOs are deferred for more than a year, because they come from savings created during the prior year. It is the proverbial "you can’t get there from here" problem.

How do we avoid this "Catch-22," in which the primary care–driven ACO model is best suited to meet the goals of ACOs but often is least able to afford the costs of creating ACOs?

The answer may be the federal government. There are several viable options available to have the government effectively fund 100% of your ACO start-up costs.

Consider the following:

• Meaningful use incentives. Why not have the government pay for your ACO technology platform? If you think ahead, the health information exchange you will want for your ACO will likely qualify you for stage 2 and stage 3 meaningful use incentives. You can earn up to $44,000 over 5 years from Medicare, or up to $63,750 over 6 years from Medicaid. Instead of data being a burden under fee for service, access to and exchange capability of data will be a huge asset.

You will need to make these investments anyway. If you have your ACO game plan in place, much of what you and your colleagues do to meet the meaningful use criteria can be used to fund your ACO.

• Advance payment model program. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services apparently recognized the "you can’t get there from here" dilemma by creating the advance payment model program. Physician-run ACOs in rural areas have been singled out to receive enough up-front funding to completely pay for the development and implementation of the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) ACO until shared savings payments kick in.

In addition to the MSSP application, ACOs that wish to receive advance funding from the CMS Innovation Center must also complete the advance payment model application. The advance payment model is open to only two types of ACOs: ACOs that do not include any inpatient facilities and have less than $50 million in total annual revenue; and ACOs in which the only inpatient facilities are critical access hospitals and/or Medicare low-volume rural hospitals, and that have less than $80 million in total annual revenue. ACOs that are co-owned with a health plan will be ineligible, regardless of whether they also fall into one of the above categories.

The advance payment model application consists of two primary sections: the ACO’s financial characteristics; and the ACO’s investment plan.

With respect to the financial characteristics, the ACO will need to list the total annual revenue and total Medicaid revenue for each ACO participant during the preceding 3 years. The information submitted by the ACO will need to be based on either federal tax returns or audited financial statements.

The second key section of the advance payment model application is the ACO investment plan. The ACO must explain how it intends to use the advance payment funds awarded from CMS.

Specifically, the investment plan must include:

• A description of the types of staffing and infrastructure that the ACO will acquire and/or expand using the funding available through the advance payment model.

• The timing of such acquisitions or expansions, and the estimated unit costs.

• A description of how such investments build on staff and infrastructure the ACO already has or plans to acquire through its own upcoming investments.

• An explanation of how each investment will support the ACO in achieving the three-part aim of better health, better health care, and lower per capita costs for Medicare beneficiaries.

The advance payment model money may not be renewed once the initial $1 billion budgeted amount is exhausted. But if the results and return on investment are as powerful as predicted for the targeted ACOs, this could be viewed as a sound investment by CMS.

At current levels, an ACO will receive an up-front fixed amount of $250,000, a variable $36/member, and then $8/member per month. This will be repaid if there are ACO shared savings later on.

Beyond the dollars and cents impact, the APM program is vivid evidence for primary care physicians of just how promising CMS believes physician-directed ACOs are.

Primary care physicians are starting to understand the professional and financial rewards behind ACOs. They should not be dismayed by lack of funding. The payers know that funding these ACOs is a smart "investment" in reforming our inefficient and wasteful current system.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Topical Fluorocarbon Speeds Tattoo Removal Process

ATLANTA – Applying the topical fluorocarbon perfluorodecalin prior to Q-switched laser treatment for tattoo removal allows for immediate retreatment of the tattoo, thereby improving results while decreasing overall treatment time, according to Dr. Roy Geronemus.

The findings have important implications for improving outcomes and patient satisfaction, given that tattoo removal can require 10-20 sessions, depending on factors such as the age and colors of the tattoo, and that tattoos – and thus tattoo removal – continue to increase in popularity, he said. "For a busy practice or impatient patients like we have in New York, this has been a nice advance," Dr. Geronemus said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The approach builds on the "R20 technique" described earlier this year in a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. R20 involves the use of multiple treatment passes that are made at 20-minute intervals.

Typically, after an initial pass, tiny white bubbles form in the superficial papillary dermis, appearing as a whitening of the skin. Retreatment while these bubbles are present elicits a limited reaction.

The R20 technique was developed when investigators found that the bubbles disappear after 20 minutes, and, thus, tested the technique in a study of 12 adults. The patients were randomized to a single treatment pass with a Q-switched alexandrite laser (5.5 J/cm2, 755 nm, 100-nanosecond pulse duration, 3-mm spot size) or to four passes at 20 minute intervals.

The first treatment caused an immediate whitening reaction, but little or no whitening occurred after subsequent passes at 20-minute intervals. However, at 90-day follow-up, significant improvement was seen in the R20 group, compared with the single-treatment group, and light microscopy demonstrated greater dispersion of tattoo ink with the R20 approach. (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;66:271-7).

Despite the increased efficacy using this approach, the time required to complete four passes at 20-minute intervals makes it impractical in the clinical setting, said Dr. Geronemus, a dermatologist in private practice in New York.

"So with this idea in mind, we began to look at a concept that would allow us to re-treat tattoos immediately without waiting 20 minutes," he said, explaining that topical perfluorodecalin helps dissolve the gas seen after the application of the Q-switched laser and speeds the resolution of the whitening.

"Rather than waiting 20 minutes, the gas dissolves almost immediately, allowing you to re-treat, and we’re now re-treating three or four times in a matter of minutes rather than waiting the 80 minutes that the R20 technique would take for a four-time treatment session," he said.

In his experience, results with perfluorodecalin are comparable to those seen with the R20 technique – but with greater convenience for the patient.

His observations were confirmed on optical coherence tomography scanning, which demonstrated that cavitation levels are indeed reduced by the use of perfluorodecalin.

Dr. Geronemus is an investigator for Cutera, Cynosure, Palomar, Solta Medical, and Syneron. He is also on the medical advisory board for Cynosure, Lumenis, Photomedex, Syneron, and Zeltiq. He reported that he is a Zeltiq shareholder.

ATLANTA – Applying the topical fluorocarbon perfluorodecalin prior to Q-switched laser treatment for tattoo removal allows for immediate retreatment of the tattoo, thereby improving results while decreasing overall treatment time, according to Dr. Roy Geronemus.

The findings have important implications for improving outcomes and patient satisfaction, given that tattoo removal can require 10-20 sessions, depending on factors such as the age and colors of the tattoo, and that tattoos – and thus tattoo removal – continue to increase in popularity, he said. "For a busy practice or impatient patients like we have in New York, this has been a nice advance," Dr. Geronemus said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The approach builds on the "R20 technique" described earlier this year in a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. R20 involves the use of multiple treatment passes that are made at 20-minute intervals.

Typically, after an initial pass, tiny white bubbles form in the superficial papillary dermis, appearing as a whitening of the skin. Retreatment while these bubbles are present elicits a limited reaction.

The R20 technique was developed when investigators found that the bubbles disappear after 20 minutes, and, thus, tested the technique in a study of 12 adults. The patients were randomized to a single treatment pass with a Q-switched alexandrite laser (5.5 J/cm2, 755 nm, 100-nanosecond pulse duration, 3-mm spot size) or to four passes at 20 minute intervals.

The first treatment caused an immediate whitening reaction, but little or no whitening occurred after subsequent passes at 20-minute intervals. However, at 90-day follow-up, significant improvement was seen in the R20 group, compared with the single-treatment group, and light microscopy demonstrated greater dispersion of tattoo ink with the R20 approach. (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;66:271-7).

Despite the increased efficacy using this approach, the time required to complete four passes at 20-minute intervals makes it impractical in the clinical setting, said Dr. Geronemus, a dermatologist in private practice in New York.

"So with this idea in mind, we began to look at a concept that would allow us to re-treat tattoos immediately without waiting 20 minutes," he said, explaining that topical perfluorodecalin helps dissolve the gas seen after the application of the Q-switched laser and speeds the resolution of the whitening.

"Rather than waiting 20 minutes, the gas dissolves almost immediately, allowing you to re-treat, and we’re now re-treating three or four times in a matter of minutes rather than waiting the 80 minutes that the R20 technique would take for a four-time treatment session," he said.

In his experience, results with perfluorodecalin are comparable to those seen with the R20 technique – but with greater convenience for the patient.

His observations were confirmed on optical coherence tomography scanning, which demonstrated that cavitation levels are indeed reduced by the use of perfluorodecalin.

Dr. Geronemus is an investigator for Cutera, Cynosure, Palomar, Solta Medical, and Syneron. He is also on the medical advisory board for Cynosure, Lumenis, Photomedex, Syneron, and Zeltiq. He reported that he is a Zeltiq shareholder.

ATLANTA – Applying the topical fluorocarbon perfluorodecalin prior to Q-switched laser treatment for tattoo removal allows for immediate retreatment of the tattoo, thereby improving results while decreasing overall treatment time, according to Dr. Roy Geronemus.

The findings have important implications for improving outcomes and patient satisfaction, given that tattoo removal can require 10-20 sessions, depending on factors such as the age and colors of the tattoo, and that tattoos – and thus tattoo removal – continue to increase in popularity, he said. "For a busy practice or impatient patients like we have in New York, this has been a nice advance," Dr. Geronemus said at the annual meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery.

The approach builds on the "R20 technique" described earlier this year in a study published in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. R20 involves the use of multiple treatment passes that are made at 20-minute intervals.

Typically, after an initial pass, tiny white bubbles form in the superficial papillary dermis, appearing as a whitening of the skin. Retreatment while these bubbles are present elicits a limited reaction.

The R20 technique was developed when investigators found that the bubbles disappear after 20 minutes, and, thus, tested the technique in a study of 12 adults. The patients were randomized to a single treatment pass with a Q-switched alexandrite laser (5.5 J/cm2, 755 nm, 100-nanosecond pulse duration, 3-mm spot size) or to four passes at 20 minute intervals.

The first treatment caused an immediate whitening reaction, but little or no whitening occurred after subsequent passes at 20-minute intervals. However, at 90-day follow-up, significant improvement was seen in the R20 group, compared with the single-treatment group, and light microscopy demonstrated greater dispersion of tattoo ink with the R20 approach. (J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2012;66:271-7).

Despite the increased efficacy using this approach, the time required to complete four passes at 20-minute intervals makes it impractical in the clinical setting, said Dr. Geronemus, a dermatologist in private practice in New York.

"So with this idea in mind, we began to look at a concept that would allow us to re-treat tattoos immediately without waiting 20 minutes," he said, explaining that topical perfluorodecalin helps dissolve the gas seen after the application of the Q-switched laser and speeds the resolution of the whitening.

"Rather than waiting 20 minutes, the gas dissolves almost immediately, allowing you to re-treat, and we’re now re-treating three or four times in a matter of minutes rather than waiting the 80 minutes that the R20 technique would take for a four-time treatment session," he said.

In his experience, results with perfluorodecalin are comparable to those seen with the R20 technique – but with greater convenience for the patient.

His observations were confirmed on optical coherence tomography scanning, which demonstrated that cavitation levels are indeed reduced by the use of perfluorodecalin.

Dr. Geronemus is an investigator for Cutera, Cynosure, Palomar, Solta Medical, and Syneron. He is also on the medical advisory board for Cynosure, Lumenis, Photomedex, Syneron, and Zeltiq. He reported that he is a Zeltiq shareholder.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL MEETING OF THE AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR DERMATOLOGIC SURGERY

Bedside Tools to ID Severe C. difficile Fall Short

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer severity criteria, but these require the observation of clinical end points and thus are ineffective for assessing patients at initial presentation, she said in a poster presentation at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

The Hines VA scoring system, in addition to missing the most severe cases, also gives a great deal of weight to diagnostic imaging, which "makes it impractical at our institution," she said. The Hines VA tool incorporates temperature, the presence of ileus, systolic blood pressure, leukocytosis, and abnormal CT findings to stratify patients by severity.

"We’re going to continue relying on the clinician’s assessment at the bedside at the time of diagnosis to evaluate whether cases are severe or not severe, and not use any of these tools that are available," Dr. Doan said.

A good bedside tool sure would be nice, though, to have a good, objective way of identifying severe C. difficile infection, she added. In a large health system, order sets could be developed based on the tool’s findings "so that everybody would be on the same page in terms of treatment," she said. None of the current tools are good enough for that.

Severe cases of C. difficile are on the rise because of increasing prevalence of the hypervirulent NAP1/BI/027 strain, she noted.

A number of clinicians at the meeting approached her with their own versions of bedside tools for identifying severe C. difficile infection, which Dr. Doan and her associates may evaluate next. They also may compare the tools on different subpopulations of patients with severe infection, such as only patients whose death or surgery was related to C. difficile infection.

Dr. Doan reported having no financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

Reported mortality from Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) in the United States has increased dramatically in recent years (Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007;13: 1417-9). Current guidelines call for the use of oral vancomy-cin as first-line therapy in severe CDI while metronidazole may be used in milder disease (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55). Thus, it becomes important for therapy to identify those with potentially severe CDI early in their clinical course. However, a systematic review published in 2012 that specifically looked at clinical prediction rules (CPRs) for poor outcomes in CDI concluded that the available tools are inadequate for the task (PLoS One 2012;7:e30258).

The study by Dr. Doan and colleagues assessed the utility of bedside severity-of-illness tools in the treatment of patients with CDI. This was a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed CDI. Three CPRs were assessed: The Hines VA system , ; the ATLAS scoring system; and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. . Sensitivity in detecting severe outcomes of CDI were 57%, 68%, and 89%, respectively. However, the most sensitive CPR, the IDSA guideline, showed poor specificity because it categorized 60% of all subjects as severe. Thus, the IDSA guideline will encourage more widespread use of oral vancomycin in CDI.

Therefore, we lack a risk-scoring system for severe CDI that is easy to use, sensitive, specific, and validated. Such a prediction tool is essential to allow us to follow the current CDI treatment guidelines.

CIARAN P. KELLY, M.D., is director of gastroenterology training and is medical director of the Celiac Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston. SAURABH SETHI, M.D., is a fellow in gastroenterology and hepatology at Beth Israe Deaconess. Dr. Kelly reported serving as a consultant or scientific advisor for, being a member of an advisory board for, or receiving research support from many companies developing drugs for C. difficile. Dr. Sethi had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer severity criteria, but these require the observation of clinical end points and thus are ineffective for assessing patients at initial presentation, she said in a poster presentation at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

The Hines VA scoring system, in addition to missing the most severe cases, also gives a great deal of weight to diagnostic imaging, which "makes it impractical at our institution," she said. The Hines VA tool incorporates temperature, the presence of ileus, systolic blood pressure, leukocytosis, and abnormal CT findings to stratify patients by severity.

"We’re going to continue relying on the clinician’s assessment at the bedside at the time of diagnosis to evaluate whether cases are severe or not severe, and not use any of these tools that are available," Dr. Doan said.

A good bedside tool sure would be nice, though, to have a good, objective way of identifying severe C. difficile infection, she added. In a large health system, order sets could be developed based on the tool’s findings "so that everybody would be on the same page in terms of treatment," she said. None of the current tools are good enough for that.

Severe cases of C. difficile are on the rise because of increasing prevalence of the hypervirulent NAP1/BI/027 strain, she noted.

A number of clinicians at the meeting approached her with their own versions of bedside tools for identifying severe C. difficile infection, which Dr. Doan and her associates may evaluate next. They also may compare the tools on different subpopulations of patients with severe infection, such as only patients whose death or surgery was related to C. difficile infection.

Dr. Doan reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN FRANCISCO – A side-by-side comparison of three bedside tools used to identify severe cases of Clostridium difficile infection yielded no clear winner, a reminder that judgment at diagnosis is still the clinician’s best bet.

Criteria from the Infectious Diseases Society of America were more sensitive but the least specific than both the Hines Veterans Affairs (VA) and the ATLAS severity scoring systems, Thien-Ly Doan, Pharm.D. explained in an interview at the annual Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

The Hines VA system for stratifying patients missed 19 of 44 severe/complicated cases of C. difficile infection. The ATLAS scoring system (which incorporates five parameters: age, temperature, leukocytosis, albumin, and systemic concomitant antibiotic use) missed 14 of the 44 cases in a retrospective chart review of 109 patients hospitalized for more than a day with confirmed C. difficile infection.

The IDSA guidelines missed only 5 of the 44 severe/complicated infections, but they cast such a wide net that anyone with a white count above 15,000 cells/mm3 or an elevated creatinine (1.5 times or greater than the premorbid level) is considered to have severe C. difficile infection, she said.

Use of the IDSA guidelines could increase unnecessary use of vancomycin instead of metronidazole, said Dr. Doan, a clinical coordinator at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New Hyde Park, N.Y.

The IDSA criteria suggested that nearly 60% of the 109 patients had severe infection. However, the 44 severe/complicated C. difficile patients comprised just 40% of the study population. They were defined in the study as patients who were in critical care or whose infections were refractory to treatment and who had ileus, severe pancolitis/toxic megacolon, a WBC of 15,000 cells/mL with hypotension, surgery related to C. difficile infection, or who had died from infection.

Dr. Doan and her associates compared the three stratification systems in evaluating the charts of adults with C. difficile infection at the medical center, who had a mean age of 71 years. A total of 74% of patients were on the medicine service, 22% were in critical care, and 4% were on the surgical service; 34% were female.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also offer severity criteria, but these require the observation of clinical end points and thus are ineffective for assessing patients at initial presentation, she said in a poster presentation at the meeting, sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology.

The Hines VA scoring system, in addition to missing the most severe cases, also gives a great deal of weight to diagnostic imaging, which "makes it impractical at our institution," she said. The Hines VA tool incorporates temperature, the presence of ileus, systolic blood pressure, leukocytosis, and abnormal CT findings to stratify patients by severity.

"We’re going to continue relying on the clinician’s assessment at the bedside at the time of diagnosis to evaluate whether cases are severe or not severe, and not use any of these tools that are available," Dr. Doan said.

A good bedside tool sure would be nice, though, to have a good, objective way of identifying severe C. difficile infection, she added. In a large health system, order sets could be developed based on the tool’s findings "so that everybody would be on the same page in terms of treatment," she said. None of the current tools are good enough for that.

Severe cases of C. difficile are on the rise because of increasing prevalence of the hypervirulent NAP1/BI/027 strain, she noted.

A number of clinicians at the meeting approached her with their own versions of bedside tools for identifying severe C. difficile infection, which Dr. Doan and her associates may evaluate next. They also may compare the tools on different subpopulations of patients with severe infection, such as only patients whose death or surgery was related to C. difficile infection.

Dr. Doan reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ANNUAL INTERSCIENCE CONFERENCE ON ANTIMICROBIAL AGENTS AND CHEMOTHERAPY

What Keeps You Awake at Night?

"The greatest enemy of knowledge is the illusion of knowledge." – Stephen Hawking

In my fellowship, I had a challenging RA case. This woman was in her 50s, and usually she was quite dynamic, personable, and spunky. But the disease was wearing her down. She developed methotrexate pneumonitis. Leflunomide gave her severe diarrhea. She got frequent upper respiratory tract infections from etanercept. We could not get her prednisone dose lower than 15 mg/day. Whenever we saw her in clinic and she had encountered a new glitch in her treatment, my preceptor would say to her "you keep me up at night." Disturbed to hear this, I wondered how insecure I would be as a newly minted rheumatologist if my preceptor, with her decades of practice, still had uncertainties.

I feel like in these, the first 3 years of practice after training, I have an inordinate number of patients who keep me up at night. They come in all shapes and sizes. Even cases that I think are straightforward frequently end up being anything but.

I like treating patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, for example, because the relief they get from a little prednisone is so dramatic and immediate. Seems straightforward, no? But I get anxious about the diagnosis sometimes – what if I’m missing a paraneoplastic syndrome? Not infrequently there are patients who absolutely refuse to go on prednisone, and I worry about them, too. Or I get anxious about tapering, because I’ve had it happen often enough that their symptoms recur at 3 mg of prednisone and I need to put them on a DMARD, none of which have any conclusive evidence of efficacy.

Rheumatoid arthritis is not always easy, either. I have had my share of refractory cases, which, in this age of different varieties of biologics, is even more frustrating. (Although, for the life of me, I cannot imagine what it must have been like to practice before the age of biologics!) It’s even worse for refractory psoriatic arthritis, for which there are fewer drug options available.

And what about scleroderma? I watched a patient’s hands progress from being simply puffy at presentation to being contracted, with severe skin tightening and skin ulcerations over the PIP joints, in just 2 years. We are lucky to be close enough to Boston that I could send the patient to a medical center there to receive an investigational therapy, which seemed to lessen the patient’s symptoms somewhat. Unfortunately, she developed urinary bladder cancer and is now ineligible to receive the experimental anti-TGF-beta in an open label extension.

But perhaps my most insomnia-inducing patient is a lovely 70-year-old man with a new diagnosis of dermatomyositis. His antinuclear antibody was negative, and he had no myositis-specific antibodies. We knew we should be looking for a malignancy, but a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative. A colonoscopy was next, but if that did not turn anything up, what would be next? Do we keep searching? How do we know where to look?

Worse, the pulse of methylprednisolone did not work completely, and he ended up needing a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube because he failed his swallow evaluation miserably. I was really saddened by all this. It made me feel small and insignificant in the face of such a terrible disease.

In that process of placing a PEG tube, we serendipitously found, on biopsy, adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. Though this was, indeed, terrible news, it was a source of comfort for me that we had found the malignancy and would at least have a target for treatment.

I know he will not be my last dermatomyositis patient, and there are no prescribed guidelines for searching for a malignancy. How can we possibly find something if we have no idea what it is or where it might be?

I can think of so many more lupus, spondyloarthritis, temporal arteritis, even mechanical back pain patients who worry me, to say nothing of the not-insignificant number of patients for whom the diagnosis is uncertain. True, my learning curve has been steep in these first 3 years, but the more patients I see, the more striking the large number of phenotypes of our diseases. It’s quite humbling and has kept me up more nights than I expected.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I. E-mail her at [email protected].

"The greatest enemy of knowledge is the illusion of knowledge." – Stephen Hawking

In my fellowship, I had a challenging RA case. This woman was in her 50s, and usually she was quite dynamic, personable, and spunky. But the disease was wearing her down. She developed methotrexate pneumonitis. Leflunomide gave her severe diarrhea. She got frequent upper respiratory tract infections from etanercept. We could not get her prednisone dose lower than 15 mg/day. Whenever we saw her in clinic and she had encountered a new glitch in her treatment, my preceptor would say to her "you keep me up at night." Disturbed to hear this, I wondered how insecure I would be as a newly minted rheumatologist if my preceptor, with her decades of practice, still had uncertainties.

I feel like in these, the first 3 years of practice after training, I have an inordinate number of patients who keep me up at night. They come in all shapes and sizes. Even cases that I think are straightforward frequently end up being anything but.

I like treating patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, for example, because the relief they get from a little prednisone is so dramatic and immediate. Seems straightforward, no? But I get anxious about the diagnosis sometimes – what if I’m missing a paraneoplastic syndrome? Not infrequently there are patients who absolutely refuse to go on prednisone, and I worry about them, too. Or I get anxious about tapering, because I’ve had it happen often enough that their symptoms recur at 3 mg of prednisone and I need to put them on a DMARD, none of which have any conclusive evidence of efficacy.

Rheumatoid arthritis is not always easy, either. I have had my share of refractory cases, which, in this age of different varieties of biologics, is even more frustrating. (Although, for the life of me, I cannot imagine what it must have been like to practice before the age of biologics!) It’s even worse for refractory psoriatic arthritis, for which there are fewer drug options available.

And what about scleroderma? I watched a patient’s hands progress from being simply puffy at presentation to being contracted, with severe skin tightening and skin ulcerations over the PIP joints, in just 2 years. We are lucky to be close enough to Boston that I could send the patient to a medical center there to receive an investigational therapy, which seemed to lessen the patient’s symptoms somewhat. Unfortunately, she developed urinary bladder cancer and is now ineligible to receive the experimental anti-TGF-beta in an open label extension.

But perhaps my most insomnia-inducing patient is a lovely 70-year-old man with a new diagnosis of dermatomyositis. His antinuclear antibody was negative, and he had no myositis-specific antibodies. We knew we should be looking for a malignancy, but a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative. A colonoscopy was next, but if that did not turn anything up, what would be next? Do we keep searching? How do we know where to look?

Worse, the pulse of methylprednisolone did not work completely, and he ended up needing a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube because he failed his swallow evaluation miserably. I was really saddened by all this. It made me feel small and insignificant in the face of such a terrible disease.

In that process of placing a PEG tube, we serendipitously found, on biopsy, adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. Though this was, indeed, terrible news, it was a source of comfort for me that we had found the malignancy and would at least have a target for treatment.

I know he will not be my last dermatomyositis patient, and there are no prescribed guidelines for searching for a malignancy. How can we possibly find something if we have no idea what it is or where it might be?

I can think of so many more lupus, spondyloarthritis, temporal arteritis, even mechanical back pain patients who worry me, to say nothing of the not-insignificant number of patients for whom the diagnosis is uncertain. True, my learning curve has been steep in these first 3 years, but the more patients I see, the more striking the large number of phenotypes of our diseases. It’s quite humbling and has kept me up more nights than I expected.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I. E-mail her at [email protected].

"The greatest enemy of knowledge is the illusion of knowledge." – Stephen Hawking

In my fellowship, I had a challenging RA case. This woman was in her 50s, and usually she was quite dynamic, personable, and spunky. But the disease was wearing her down. She developed methotrexate pneumonitis. Leflunomide gave her severe diarrhea. She got frequent upper respiratory tract infections from etanercept. We could not get her prednisone dose lower than 15 mg/day. Whenever we saw her in clinic and she had encountered a new glitch in her treatment, my preceptor would say to her "you keep me up at night." Disturbed to hear this, I wondered how insecure I would be as a newly minted rheumatologist if my preceptor, with her decades of practice, still had uncertainties.

I feel like in these, the first 3 years of practice after training, I have an inordinate number of patients who keep me up at night. They come in all shapes and sizes. Even cases that I think are straightforward frequently end up being anything but.

I like treating patients with polymyalgia rheumatica, for example, because the relief they get from a little prednisone is so dramatic and immediate. Seems straightforward, no? But I get anxious about the diagnosis sometimes – what if I’m missing a paraneoplastic syndrome? Not infrequently there are patients who absolutely refuse to go on prednisone, and I worry about them, too. Or I get anxious about tapering, because I’ve had it happen often enough that their symptoms recur at 3 mg of prednisone and I need to put them on a DMARD, none of which have any conclusive evidence of efficacy.

Rheumatoid arthritis is not always easy, either. I have had my share of refractory cases, which, in this age of different varieties of biologics, is even more frustrating. (Although, for the life of me, I cannot imagine what it must have been like to practice before the age of biologics!) It’s even worse for refractory psoriatic arthritis, for which there are fewer drug options available.

And what about scleroderma? I watched a patient’s hands progress from being simply puffy at presentation to being contracted, with severe skin tightening and skin ulcerations over the PIP joints, in just 2 years. We are lucky to be close enough to Boston that I could send the patient to a medical center there to receive an investigational therapy, which seemed to lessen the patient’s symptoms somewhat. Unfortunately, she developed urinary bladder cancer and is now ineligible to receive the experimental anti-TGF-beta in an open label extension.

But perhaps my most insomnia-inducing patient is a lovely 70-year-old man with a new diagnosis of dermatomyositis. His antinuclear antibody was negative, and he had no myositis-specific antibodies. We knew we should be looking for a malignancy, but a CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was negative. A colonoscopy was next, but if that did not turn anything up, what would be next? Do we keep searching? How do we know where to look?

Worse, the pulse of methylprednisolone did not work completely, and he ended up needing a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube because he failed his swallow evaluation miserably. I was really saddened by all this. It made me feel small and insignificant in the face of such a terrible disease.

In that process of placing a PEG tube, we serendipitously found, on biopsy, adenocarcinoma at the gastroesophageal junction. Though this was, indeed, terrible news, it was a source of comfort for me that we had found the malignancy and would at least have a target for treatment.

I know he will not be my last dermatomyositis patient, and there are no prescribed guidelines for searching for a malignancy. How can we possibly find something if we have no idea what it is or where it might be?

I can think of so many more lupus, spondyloarthritis, temporal arteritis, even mechanical back pain patients who worry me, to say nothing of the not-insignificant number of patients for whom the diagnosis is uncertain. True, my learning curve has been steep in these first 3 years, but the more patients I see, the more striking the large number of phenotypes of our diseases. It’s quite humbling and has kept me up more nights than I expected.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I. E-mail her at [email protected].

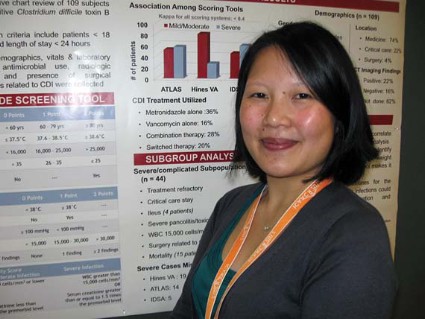

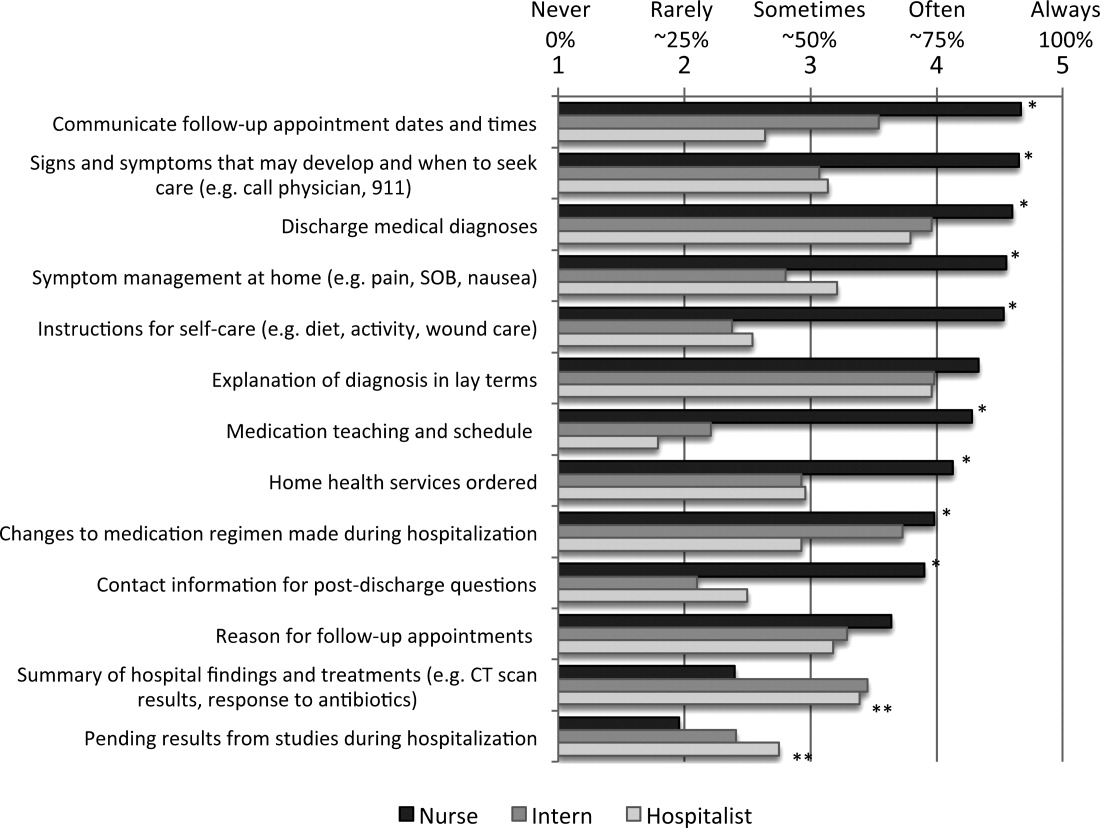

Communicating Discharge Instructions

Discharge from the hospital is a vulnerable time for patients. Nearly 1 in 5 patients experiences an adverse event during this transition, with a third of these being likely preventable.1, 2 Comprehensive discharge instructions are necessary to ensure a smooth transition from hospital to home, as the responsibility for care shifts from providers to the patient and caregivers. Unfortunately, patients often go home without understanding critical information about their hospital stay, such as their discharge diagnosis or medication changes,3, 4 leaving them both dissatisfied with their discharge instructions5 and at risk for hospital readmission.

Efforts to improve discharge education have focused on increasing communication between care provider and patient. The use of designated discharge coordinators,6, 7 implementation of teach‐back techniques to assess and confirm understanding,8 and adoption of patient‐centered educational materials all offer tools to improve communication with patients. However, guidelines for communication between providers and their shared role in patient discharge education, particularly between nurses and physicians, are scarce. Daily interdisciplinary rounds9 and shared electronic health records are potential ways to foster such communication, but the methods and frequency with which providers communicate about discharge instructions with each other is poorly understood. Furthermore, despite a common set of goals for discharge instructions,10, 11 it is unclear where the responsibility to provide these elements lies: with nurses, physicians, neither, or both.

Understanding perceptions and communication practices of providers in their delivery of discharge instructions is an important first step in defining responsibilities and improving accountability for discharge education. In this study, we surveyed nurses and physicians about their discharge education practices to better understand how each group sees their own role in discharge teaching, and how these findings may generate recommendations to improve future practices.

METHODS

Setting and Subjects

University of California, San Francisco Medical Center (UCSFMC) is a 600‐bed tertiary care academic teaching hospital. We surveyed interns, hospitalists on a teaching service, and day‐shift nurses from the inpatient medical service, based on care they provided at UCSFMC from July 2010 to February 2011. The 3 groups are the primary providers at our institution who deliver discharge education. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Committee on Human Research.

Survey Development

We developed a survey tool based on a literature review and expert input from local institutional leaders in nursing, residency training, and hospital medicine. The aims of the survey tool were to: 1) assess perceptions and practice of the nurse and physician role in patient discharge education; 2) describe the current practice of physiciannurse communication at discharge; and 3) assess openness to new communication tools.

Specific elements of discharge education assessed in the survey were established from the existing literature,10, 11 and our local best practices (see Supporting Information, Text Box, in the online version of this article). Prior to survey administration, we conducted informal focus groups of interns, hospitalists, and day‐shift nurses, and piloted the survey to assure clarity in the questions and proposed responses.

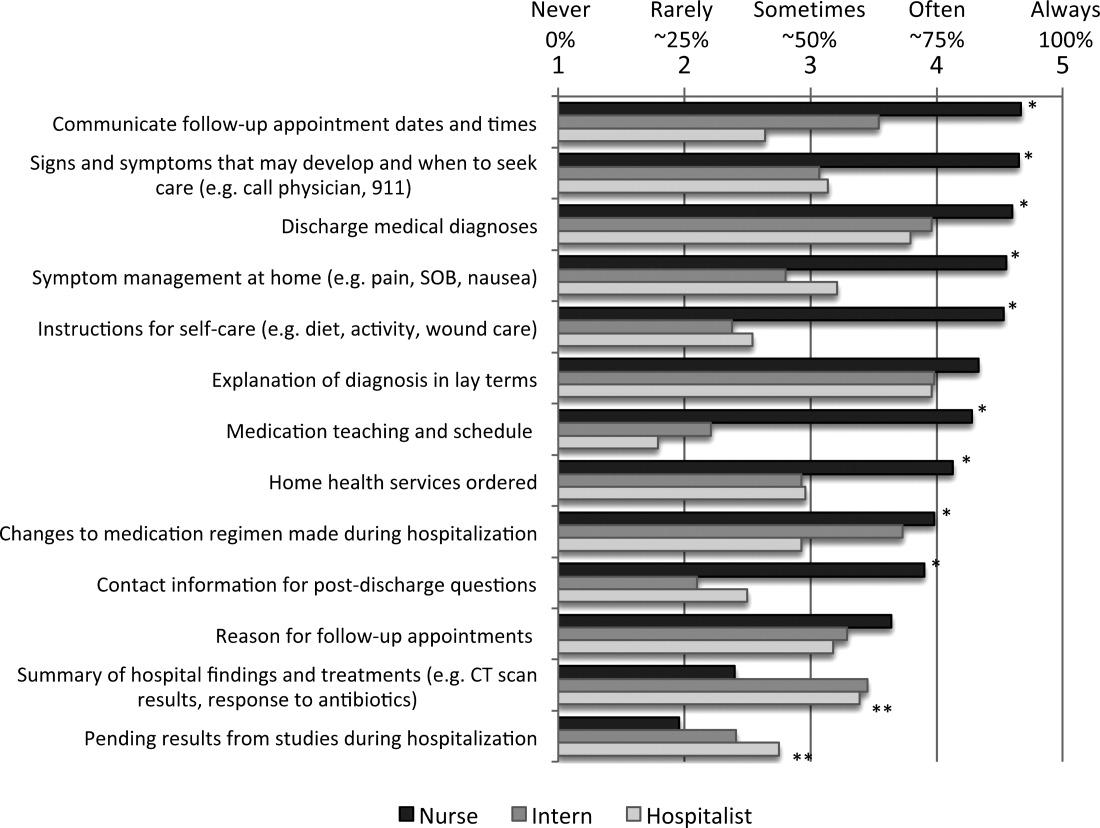

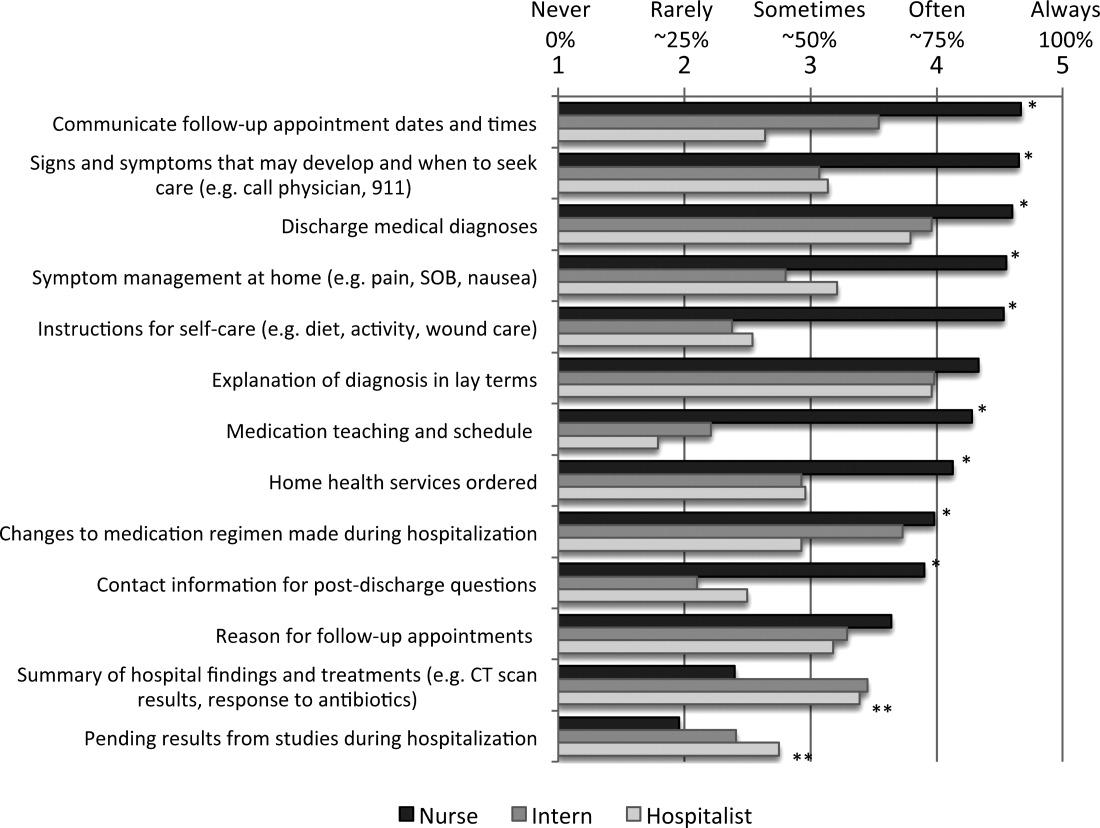

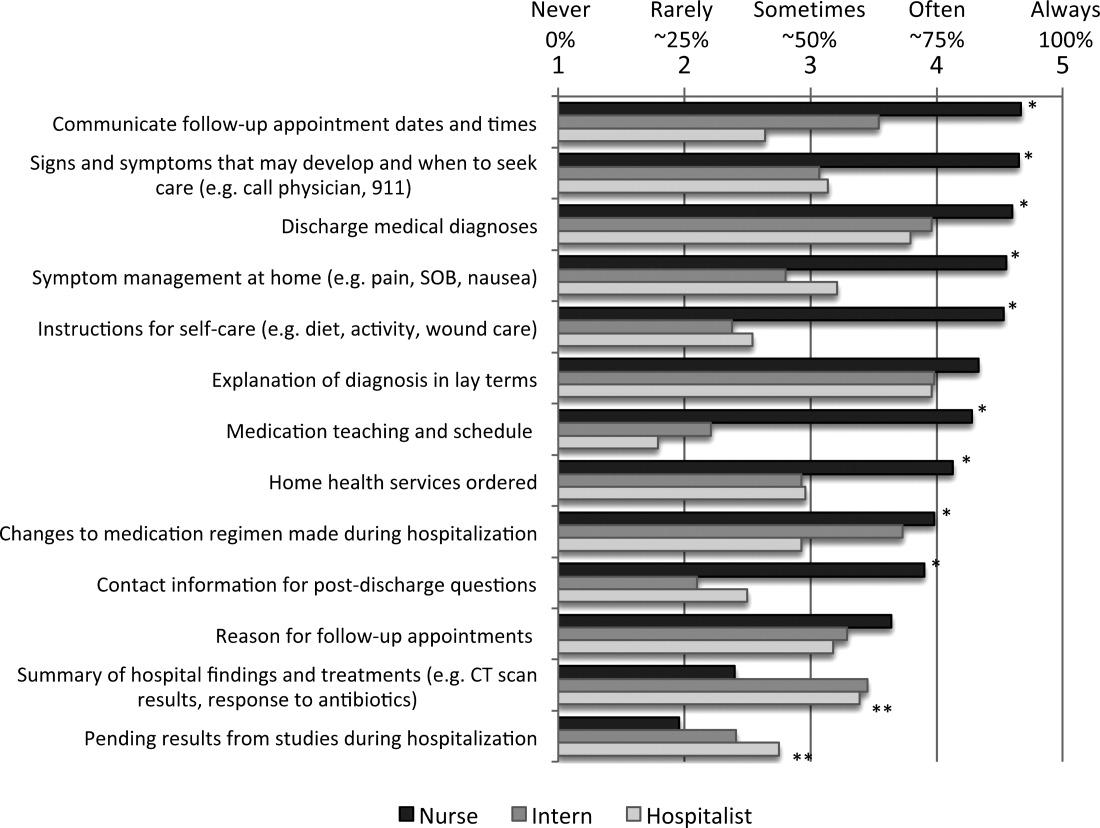

The survey asked respondents to assign responsibility for the discharge education elements to the physician, nurse, both, or neither, and then to describe their current practice in patient education and in physiciannurse communication. The frequency that respondents provide discharge education to patients and the frequency of nursephysician communication around the elements of discharge education were assessed using Likert scales (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = always). Finally, the survey asked respondents about their interest in tools to improve provider communication at discharge.

Survey Administration