User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Listen to Joaquin Cigarroa, MD, of Oregon Health & Science University, discuss the overlap of cardiology and hospital medicine

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

Click here to listen to Dr. Cigarroa

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, discusses the differences in opinion over the SHM/SCCM critical care fellowship proposal

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Special Skills Hospitalists Need for the Intensive Care Unit

Critical-care experts point to three types of competency that are crucial for any hospitalist working within an ICU environment. First, hospitalists need a solid knowledge base of the pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology of critical illnesses and conditions such as renal failure, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, sepsis, and seizures.

Second, providers need to acquire an array of psychomotor and interpersonal skills. Core skills like endotracheal intubation, chest-tube placement, and arterial and central venous catheterization are essential. But so are broader abilities like bringing people together to work as a team, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta.

“Does that sound familiar? It’s what hospitalists do,” he says. “So the conceptual structure of a high-functioning intensivist team is nearly identical to the conceptual structure of a high-functioning hospitalist team; it’s just located in a smaller area, with a higher acuity patient population.”

Dr. Siegal emphasizes the importance of inpatient procedural skills, which he says are no longer emphasized in internal-medicine training. “The good news is, those skills are definable, are fairly easily taught, and are simply a matter of repetition,” he says.

Finally, hospitalists need to adopt the right attitude about what care is or isn’t possible for critically-ill patients, and how families can be integrated into complex, culturally-sensitive decision-making about difficult topics such as organ donation.

“That’s very different when the patient is unable to speak for him or herself,” Dr. Buchman says. “There’s a list of what I would call attitudinal competencies, which is longer than I think most people understand it to be to be an effective clinician. … Although all of them, to some degree, overlap with experience during residency training, they are often at a complexity level that can only be mastered through additional training.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Critical-care experts point to three types of competency that are crucial for any hospitalist working within an ICU environment. First, hospitalists need a solid knowledge base of the pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology of critical illnesses and conditions such as renal failure, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, sepsis, and seizures.

Second, providers need to acquire an array of psychomotor and interpersonal skills. Core skills like endotracheal intubation, chest-tube placement, and arterial and central venous catheterization are essential. But so are broader abilities like bringing people together to work as a team, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta.

“Does that sound familiar? It’s what hospitalists do,” he says. “So the conceptual structure of a high-functioning intensivist team is nearly identical to the conceptual structure of a high-functioning hospitalist team; it’s just located in a smaller area, with a higher acuity patient population.”

Dr. Siegal emphasizes the importance of inpatient procedural skills, which he says are no longer emphasized in internal-medicine training. “The good news is, those skills are definable, are fairly easily taught, and are simply a matter of repetition,” he says.

Finally, hospitalists need to adopt the right attitude about what care is or isn’t possible for critically-ill patients, and how families can be integrated into complex, culturally-sensitive decision-making about difficult topics such as organ donation.

“That’s very different when the patient is unable to speak for him or herself,” Dr. Buchman says. “There’s a list of what I would call attitudinal competencies, which is longer than I think most people understand it to be to be an effective clinician. … Although all of them, to some degree, overlap with experience during residency training, they are often at a complexity level that can only be mastered through additional training.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Critical-care experts point to three types of competency that are crucial for any hospitalist working within an ICU environment. First, hospitalists need a solid knowledge base of the pharmacology, physiology, and pathophysiology of critical illnesses and conditions such as renal failure, respiratory failure, cardiac failure, sepsis, and seizures.

Second, providers need to acquire an array of psychomotor and interpersonal skills. Core skills like endotracheal intubation, chest-tube placement, and arterial and central venous catheterization are essential. But so are broader abilities like bringing people together to work as a team, says Timothy Buchman, PhD, MD, director of Emory University’s Center for Critical Care in Atlanta.

“Does that sound familiar? It’s what hospitalists do,” he says. “So the conceptual structure of a high-functioning intensivist team is nearly identical to the conceptual structure of a high-functioning hospitalist team; it’s just located in a smaller area, with a higher acuity patient population.”

Dr. Siegal emphasizes the importance of inpatient procedural skills, which he says are no longer emphasized in internal-medicine training. “The good news is, those skills are definable, are fairly easily taught, and are simply a matter of repetition,” he says.

Finally, hospitalists need to adopt the right attitude about what care is or isn’t possible for critically-ill patients, and how families can be integrated into complex, culturally-sensitive decision-making about difficult topics such as organ donation.

“That’s very different when the patient is unable to speak for him or herself,” Dr. Buchman says. “There’s a list of what I would call attitudinal competencies, which is longer than I think most people understand it to be to be an effective clinician. … Although all of them, to some degree, overlap with experience during residency training, they are often at a complexity level that can only be mastered through additional training.”

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical writer in Seattle.

Penalties for Hospitals with Excessive Readmissions Take Effect

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

The new era of penalizing hospitals for higher-than-predicted 30-day avoidable readmissions rates has begun. Under the federal Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, some calculate a hospital's excessive readmissions rate for each applicable condition.

Penalties for the current fiscal year—FY 2013, which began Oct. 1, 2012—will be based on discharges that occurred during the three-year period from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011, according to the program guidelines. For hospitals that don't improve, the penalty grows to a maximum 2% next year (FY14) and 3% in FY15.

Hospitalists are not penalized directly for readmissions, and many hospitalists are wondering about the extent to which they're responsible for a readmission after the patient leaves the hospital, notes Mark Williams, MD, FACP, MHM, chief of the division of hospital medicine at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago.

Dr. Williams is the principal investigator of SHM’s Project BOOST (Better Outcomes for Older Adults through Safe Transitions), one of several national quality initiatives that teach hospitals and other healthcare providers how to improve transitions of care through such techniques as patient coaching and community partnerships.

"These new penalties mean that hospitals will start talking to their physicians about readmissions, and looking for methods to incentivize the hospitalists to get involved in preventing them," Dr. Williams says.

Study: Neurohospitalists Benefit Academic Medical Centers

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Seasonality

Did you notice that your practice was slower than normal last February? In fact, if you plot your patient census over a few years, you will probably discover that it dips every February. And you will discover other slow periods, like December, and busy months during other parts of the year.

Seasonal fluctuations are a reality in every business, including private medical practices. Why are people more or less willing to spend money at certain times of the year? Analysts usually blame slow business during January and February on reluctance to buy products or services after the holiday season. They attribute summer peaks to everything from warm weather to an increased propensity to buy when students are on vacation. It is not always easy – or necessary – to explain seasonality. The point is that such behavior patterns do exist.

It would seem that this behavior would be easy to change through advertising or by sending out an e-mail blast, but, unfortunately, altering a seasonal pattern is not an option for a small private practice. It can be done, but it is a deep-pockets game requiring long, expensive campaigns that are only practical for a large, nationwide corporation.

Take soup, for example. For many years, canned soup was purchased and consumed almost exclusively during the winter months because it was universally perceived as a cold-weather product. After years of pervasive advertising extolling its nutritional virtues (remember Campbell’s slogan "Soup is good food"?), the soup industry succeeded in convincing the public to buy their product year round. Obviously, that kind of large-scale behavior modification is not practical for a local medical practice.

Does that mean that there is nothing we can do about our practices’ seasonal variations? Not at all, but we must work within the realities of our patients’ seasonal behavior, rather than attempting to change that behavior outright.

Plotting seasonality is easy: You can make a graph using Microsoft Excel in a few minutes. Ask your office manager or accountant for month-by-month billing figures for the last 2-3 years. (Make sure it’s the amount billed, not collected, since the latter lags the former by several weeks at least.) Plot those figures on the vertical arm and time (in months) on the horizontal. Alternatively, you can plot patient visits per month. I do both.

Once you know your seasonality, review your options, which could mean modifying your own habits when necessary. If you typically take a vacation in August, for example, you many want to reconsider if August is one of your busiest months. Consider vacationing during predictable slow periods instead.

Although I have said that you can’t change most seasonal behavior, it is possible to "retrain" some of your long-time, loyal patients to come in during slower periods for at least some of their care. Use insurance company rules as a financial incentive, where possible. Many of my patients are on Medicare, so I send a notice to all of them in early November, encouraging them to come in during December (one of my light months) before their deductible has to be paid again.

If you advertise your services, do the bulk of it during your busiest months. That might seem counterintuitive: Why not advertise during slow periods to fill the empty slots? Because you cannot change seasonal behavior with a low-budget, local advertising campaign; physicians who attempt it invariably get a poor response. Advertise during your busy periods, when seasonal patterns predict that potential patients are more willing to spend money and are more likely to respond to your message.

Then, try to flatten your seasonal dips by persuading as many existing patients as possible to return during slower seasons. You can then encourage new patients to make appointments when they are receptive to purchasing new services, which would be the seasonal peaks. Once in your practice, some of them can then be shifted into slower periods, especially for predictable, periodic care.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. To respond to this column, e-mail Dr. Eastern at our editorial offices at [email protected].

Did you notice that your practice was slower than normal last February? In fact, if you plot your patient census over a few years, you will probably discover that it dips every February. And you will discover other slow periods, like December, and busy months during other parts of the year.

Seasonal fluctuations are a reality in every business, including private medical practices. Why are people more or less willing to spend money at certain times of the year? Analysts usually blame slow business during January and February on reluctance to buy products or services after the holiday season. They attribute summer peaks to everything from warm weather to an increased propensity to buy when students are on vacation. It is not always easy – or necessary – to explain seasonality. The point is that such behavior patterns do exist.

It would seem that this behavior would be easy to change through advertising or by sending out an e-mail blast, but, unfortunately, altering a seasonal pattern is not an option for a small private practice. It can be done, but it is a deep-pockets game requiring long, expensive campaigns that are only practical for a large, nationwide corporation.

Take soup, for example. For many years, canned soup was purchased and consumed almost exclusively during the winter months because it was universally perceived as a cold-weather product. After years of pervasive advertising extolling its nutritional virtues (remember Campbell’s slogan "Soup is good food"?), the soup industry succeeded in convincing the public to buy their product year round. Obviously, that kind of large-scale behavior modification is not practical for a local medical practice.

Does that mean that there is nothing we can do about our practices’ seasonal variations? Not at all, but we must work within the realities of our patients’ seasonal behavior, rather than attempting to change that behavior outright.

Plotting seasonality is easy: You can make a graph using Microsoft Excel in a few minutes. Ask your office manager or accountant for month-by-month billing figures for the last 2-3 years. (Make sure it’s the amount billed, not collected, since the latter lags the former by several weeks at least.) Plot those figures on the vertical arm and time (in months) on the horizontal. Alternatively, you can plot patient visits per month. I do both.

Once you know your seasonality, review your options, which could mean modifying your own habits when necessary. If you typically take a vacation in August, for example, you many want to reconsider if August is one of your busiest months. Consider vacationing during predictable slow periods instead.

Although I have said that you can’t change most seasonal behavior, it is possible to "retrain" some of your long-time, loyal patients to come in during slower periods for at least some of their care. Use insurance company rules as a financial incentive, where possible. Many of my patients are on Medicare, so I send a notice to all of them in early November, encouraging them to come in during December (one of my light months) before their deductible has to be paid again.

If you advertise your services, do the bulk of it during your busiest months. That might seem counterintuitive: Why not advertise during slow periods to fill the empty slots? Because you cannot change seasonal behavior with a low-budget, local advertising campaign; physicians who attempt it invariably get a poor response. Advertise during your busy periods, when seasonal patterns predict that potential patients are more willing to spend money and are more likely to respond to your message.

Then, try to flatten your seasonal dips by persuading as many existing patients as possible to return during slower seasons. You can then encourage new patients to make appointments when they are receptive to purchasing new services, which would be the seasonal peaks. Once in your practice, some of them can then be shifted into slower periods, especially for predictable, periodic care.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. To respond to this column, e-mail Dr. Eastern at our editorial offices at [email protected].

Did you notice that your practice was slower than normal last February? In fact, if you plot your patient census over a few years, you will probably discover that it dips every February. And you will discover other slow periods, like December, and busy months during other parts of the year.

Seasonal fluctuations are a reality in every business, including private medical practices. Why are people more or less willing to spend money at certain times of the year? Analysts usually blame slow business during January and February on reluctance to buy products or services after the holiday season. They attribute summer peaks to everything from warm weather to an increased propensity to buy when students are on vacation. It is not always easy – or necessary – to explain seasonality. The point is that such behavior patterns do exist.

It would seem that this behavior would be easy to change through advertising or by sending out an e-mail blast, but, unfortunately, altering a seasonal pattern is not an option for a small private practice. It can be done, but it is a deep-pockets game requiring long, expensive campaigns that are only practical for a large, nationwide corporation.

Take soup, for example. For many years, canned soup was purchased and consumed almost exclusively during the winter months because it was universally perceived as a cold-weather product. After years of pervasive advertising extolling its nutritional virtues (remember Campbell’s slogan "Soup is good food"?), the soup industry succeeded in convincing the public to buy their product year round. Obviously, that kind of large-scale behavior modification is not practical for a local medical practice.

Does that mean that there is nothing we can do about our practices’ seasonal variations? Not at all, but we must work within the realities of our patients’ seasonal behavior, rather than attempting to change that behavior outright.

Plotting seasonality is easy: You can make a graph using Microsoft Excel in a few minutes. Ask your office manager or accountant for month-by-month billing figures for the last 2-3 years. (Make sure it’s the amount billed, not collected, since the latter lags the former by several weeks at least.) Plot those figures on the vertical arm and time (in months) on the horizontal. Alternatively, you can plot patient visits per month. I do both.

Once you know your seasonality, review your options, which could mean modifying your own habits when necessary. If you typically take a vacation in August, for example, you many want to reconsider if August is one of your busiest months. Consider vacationing during predictable slow periods instead.

Although I have said that you can’t change most seasonal behavior, it is possible to "retrain" some of your long-time, loyal patients to come in during slower periods for at least some of their care. Use insurance company rules as a financial incentive, where possible. Many of my patients are on Medicare, so I send a notice to all of them in early November, encouraging them to come in during December (one of my light months) before their deductible has to be paid again.

If you advertise your services, do the bulk of it during your busiest months. That might seem counterintuitive: Why not advertise during slow periods to fill the empty slots? Because you cannot change seasonal behavior with a low-budget, local advertising campaign; physicians who attempt it invariably get a poor response. Advertise during your busy periods, when seasonal patterns predict that potential patients are more willing to spend money and are more likely to respond to your message.

Then, try to flatten your seasonal dips by persuading as many existing patients as possible to return during slower seasons. You can then encourage new patients to make appointments when they are receptive to purchasing new services, which would be the seasonal peaks. Once in your practice, some of them can then be shifted into slower periods, especially for predictable, periodic care.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. To respond to this column, e-mail Dr. Eastern at our editorial offices at [email protected].

VIP Quality Improvement Network

Currently, 3%5% of infants under a year of age will be admitted to a hospital for acute viral bronchiolitis each year, making it the leading cause of hospitalization in children.15 The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline on the diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis advocates primarily supportive care for this self‐limited disease.6 Specifically, the routine use of therapies such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids are not recommended, nor is routine evaluation with diagnostic testing.6 Numerous studies have established the presence of unwarranted variation in most aspects of bronchiolitis care,713 and the current evidence does not support the routine usage of specific interventions in inpatients.1418

Acute bronchiolitis accounts for direct inpatient medical costs of over $500 million per year.19 Based on estimates from the Healthcare Utilization Project Kids' Inpatient Database, acute bronchiolitis is second only to respiratory distress syndrome as the most expensive disease of hospitalized children.1 Although charges may not correlate directly with costs or even the actual intensity of resource utilization, the national bill, based on charges, is approximately 1.4 billion dollars per year.1 Either way, the leading cause of hospitalization in children is expensive and suffers from dramatic variation in care characterized by overutilization of ineffective interventions.

Evidence‐based guidelines for bronchiolitis are readily available and their successful adoption within larger, academic children's hospitals has been demonstrated.2028 However, upwards of 70% of all children in this country are cared for outside of freestanding children's hospitals,1 and very little has been published about wide dissemination of evidence‐based guidelines in these settings.29 In 2008, the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics (VIP) network was created, as an inclusive pediatric inpatient quality improvement collaborative with a focus on linking academic and community‐based hospitalist groups, to disseminate evidence‐based management strategies for bronchiolitis. We hypothesized that group norming, through benchmarking and public goal setting at the level of the hospitalist group, would decrease overall utilization of nonevidence‐based therapies. Specifically, we were trying to decrease the utilization of bronchodilators, steroids, chest physiotherapy, chest radiography, and viral testing in hospitalized children diagnosed with uncomplicated bronchiolitis.

METHODS

Beginning in early 2008, we recruited pediatric hospitalists into a voluntary bronchiolitis quality improvement collaborative from within the community of hospitalists created by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine. Participants were recruited through open calls at national conferences and mass e‐mails to the section membership through the listserve. The guiding principle for the collaborative was the idea that institutional adoption of evidence‐based disease‐management strategies would result in higher value of care, and that this process could be facilitated by benchmarking local performance against norms created within the larger community. We used group consensus to identify the therapies and tests to benchmark, although the chosen measures meshed with those addressed in the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline. Use of bronchodilators, corticosteroids, chest physiotherapy, chest radiography, and viral testing were all felt to be significantly overutilized in participating clinical sites. We were unaware of any published national targets for utilization of these therapies or tests, and none of the participating hospitalist groups was actively benchmarking their utilization against any peer group at the start of the project. Length of stay, rates of readmission within 72 hours of discharge, and variable direct costs were chosen as balancing measures for the project.

We collected data on hospitalizations for bronchiolitis for 4 calendar years, from 2007 through 2010, based on the following inclusion criteria: children under 24 months of age, hospitalized for the primary diagnosis of acute viral bronchiolitis as defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes 466.11 and 466.19. We specifically included patients who were in observation status as well as those in inpatient status, and excluded all intensive care unit admissions. Other exclusions were specific ICD‐9 codes for: chronic lung diseases, asthma, chromosomal abnormalities, heart disease, and neurological diseases. We then tracked overall utilization of any bronchodilator (albuterol, levalbuterol, epinephrine, or ipratropium) during the hospitalization, including the emergency department; total number of bronchodilator doses per patient; utilization of any corticosteroids (inhaled or systemic); chest radiography; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) testing; and chest physiotherapy; as well as variable direct costs per hospitalization for each center. A standardized toolkit was provided to participating centers to facilitate data collection. Data was sought from administrative sources, collected in aggregate form and not at the patient level, and no protected health information was collected as part of the project. The project was categorized as exempt by the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio Institutional Review Board, the location of the data repository.

The project began in 2008, though we requested that centers provide 2007 data to supplement our baseline. We held the first group meeting in July 2009 and began the facilitated sharing of resources to promote evidence‐based care, such as guidelines, protocols, respiratory scores, and patient handouts, across sites using data from 2007 and 2008 as our baseline for benchmarking and later assessing any improvement. Centers adopted guidelines at their own pace and we did not require guideline adoption for continued participation. We provided summaries of the available literature by topic, in the event that site leaders wished to give institutional grand rounds or other presentations. All dissemination of guidelines or protocols was done based on the request of the center, and no specific resource was created or sanctioned by the group, though the AAP Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis6 remained a guiding document. Some of our centers participated in more extensive collaborative projects which involved small‐group goal setting, adoption of similar protocols, and conference calls, though this never encompassed more than 25% of the network.

The main product of the project was a yearly report benchmarking each hospital against the network average on each of our chosen utilization measures. The first report was disseminated in July 2009 and included data on calendar year 2007 and 2008, which we considered our group baseline. Most institutions began local Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycles by mid‐2009 using the data we provided as they benchmarked their performance against other members of the collaborative, and these continued through 2010. Hospitals were coded and remained anonymous. However, we publicly honored the high performers within the network at a yearly meeting, and urged these centers to share their tools and strategies, which was facilitated through a project Web site.30 All participation was voluntary, and all costs were borne by individuals or their respective centers.

In order to assess data quality, we undertook a validation project for calendar year 2009. We requested local direct chart review of a 10% sample, or a minimum of 10 charts, to confirm reported utilization rates for the therapies and tests we tracked. Any center with less than 80% accuracy was then asked to review data collection methods and make adjustments accordingly. One center identified and resolved a significant data discrepancy and 2 centers refused to participate in the validation project, citing their participation in a large national database for which there was already a very rigorous data validation process (Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System database). Given that we did not uncover major discrepancies in data quality within our network, we did not request further data validation but rather promoted year‐to‐year consistency of collection methods, seeking to collect the same type/quality of data that hospitals use in their own internal performance assessments.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat, version 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Descriptive statistics (including interquartile range ([IQR], the range from 25th to 75th percentile of the data) are provided. Analysis of process measures over the series of years was performed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), as were intra‐hospital comparisons for all measures. Hospitals were not weighted by volume of admissions, ie, the unit of analysis was the hospital and not individual hospitalizations. Data were analyzed for normality using the method of Kolmogorov and Smirnoff, and in cases where normality was not satisfied (steroids and chest physiotherapy), the data were transformed and nonparametric methods were used. Post‐test adjustment for multiple comparisons was done using the TukeyKramer test in cases where ANOVA P values were <0.05. Fisher's exact test was used to analyze contingency tables for categorical variables such as presence or absence of a protocol.

RESULTS

Data encompassing 11,568 bronchiolitis hospitalizations in 17 centers, for calendar years 2007 to 2010, were analyzed for this report. A total of 31 centers ever participated in the project; however, this report is restricted to centers who participated for the entirety of the project from 2008 through 2010, and who consented to have their data reported. Specifically, 18 centers met inclusion criteria and 1 center opted out of the project, leaving the 17 centers described in Table 1. The overall network makeup shifted each year, but was always more than 80% non‐freestanding children's hospitals and approximately 30% urban, as defined as located in a population center of more than 1 million. A large majority of the participants did not have a local bronchiolitis protocol or guideline at the start of the project, although 88% of participants adopted some form of protocolized care by 2010. Calendar years 2007 and 2008 served as our network baseline, with most interventions (in institutions where they occurred) begun by calendar year 2009. The level of intervention varied greatly among institutions, with a few institutions doing nothing more than benchmarking their performance.

| Participating Centers (Alphabetically by State) | Type of Facility | Average Yearly Bronchiolitis Admissions | Approximate Medicaid (%) | Guideline Prior to Joining Project? | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Scottsdale Healthcare Scottsdale, AZ | PEDS | 133 | 26 | No | Suburban |

| Shands Hospital for Children at the University of Florida Gainesville, FL | CHWH | 107 | 59 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital of Illinois Peoria, IL | CHWH | 97 | 15 | No | Suburban |

| Kentucky Children's Hospital Lexington, KY | CHWH | 135 | 60 | Yes | Suburban |

| Our Lady of the Lake Baton Rouge, LA | CHWH | 138 | 70 | No | Suburban |

| The Barbara Bush Children's Hospital Portland, ME | CHWH | 31 | 41 | Yes | Suburban |

| Franklin Square Hospital Center Baltimore, MD | PEDS | 66 | 40 | No | Suburban |

| Anne Arundel Medical Center Annapolis, MD | CHWH | 56 | 36 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital at Montefiore Bronx, NY | CHWH | 220 | 65 | No | Urban |

| Mission Children's Hospital Asheville, NC | CHWH | 112 | 21 | Yes | Suburban |

| Cleveland Clinic Children's Hospital Cleveland, OH | CHWH | 58 | 24 | Yes | Urban |

| Palmetto Health Children's Hospital Columbia, SC | CHWH | 181 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| East Tennessee Children's Hospital Knoxville, TN | FSCH | 373 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| Texas Children's Hospital Houston, TX | FSCH | 619 | 60 | Yes | Urban |

| Christus Santa Rosa Children's Hospital San Antonio, TX | CHWH | 390 | 71 | No | Urban |

| Children's Hospital of The Kings' Daughters Norfolk, VA | FSCH | 303 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital of Richmond Richmond, VA | CHWH | 40 | 60 | No | Urban |

Mean length of stay (LOS), readmission rates, and variable direct costs did not differ significantly during the project time period. Mean LOS for the network ranged from a low of 2.4 days (IQR, 2.22.8 days) to a high of 2.7 days (IQR, 2.43.1 days), and mean readmission rates ranged from 1.2% (IQR, 0.7%1.8%) to 1.7% (IQR, 0.7%2.5%) during the project. Mean variable direct costs ranged from $1639 (IQR, $1383$1864) to $1767 (IQR, $1365$2320).

Table 2 describes the mean overall utilization of bronchodilators, chest radiography, RSV testing, steroids, and chest physiotherapy among the group from 2007 to 2010. By 2010, we saw a 46% decline in the volume of bronchodilator used within the network, a 3.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.45.8) dose per patient absolute decrease (P < 0.01). We also saw a 12% (95% CI 5%25%) absolute decline in the overall percentage of patients exposed to any bronchodilator (P < 0.01). Finally, there was a 10% (95% CI 3%18%) absolute decline in the overall utilization of any chest physiotherapy (P < 0.01). The project did not demonstrate a significant impact on utilization of corticosteroids, chest radiography, or viral testing, although several centers achieved significant decreases on a local level (data not shown).

| Utilization Measure | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | |

| ||||

| Bronchodilator doses per patient (P < 0.01) | 7.9 (4.69.8) | 6.4 (4.08.4) | 5.7 (3.67.6) | 4.3 (3.05.9) |

| Any bronchodilators (P < 0.01) | 70% (59%83%) | 67% (56%77%) | 68% (61%76%) | 58% (46%69%) |

| Chest physiotherapy (P < 0.01) | 14% (5%19%) | 10% (1%8%) | 7% (2%6%) | 4% (1%7%) |

| Chest radiography (P = NS) | 64% (54%81%) | 66% (55%79%) | 64% (60%73%) | 59% (50%73%) |

| Any steroids (P = NS) | 21% (14%26%) | 20% (15%28%) | 21% (14%22%) | 16% (13%25%) |

| RSV testing (P = NS) | 64% (52%84%) | 61% (49%78%) | 62% (50%78%) | 57% (44%75%) |

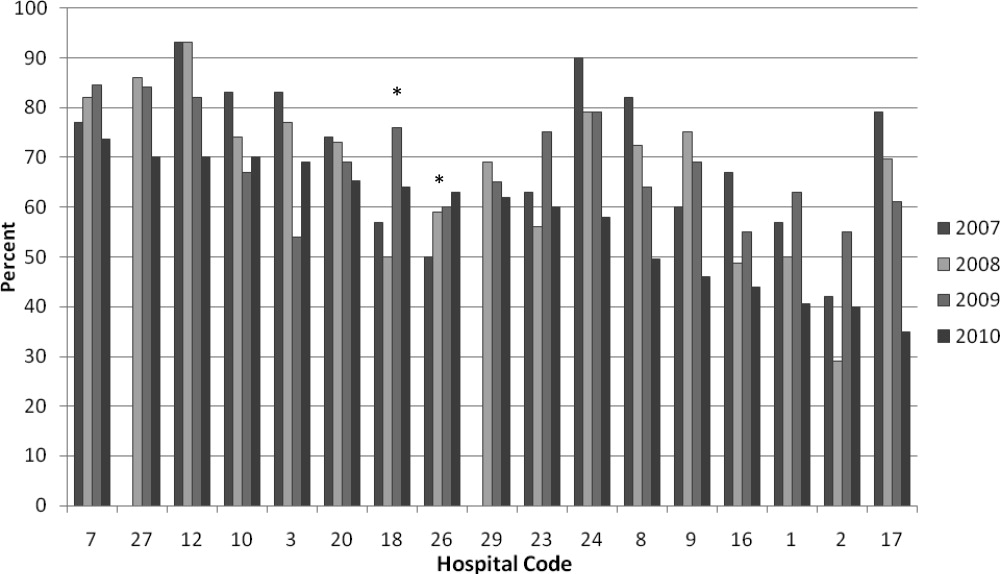

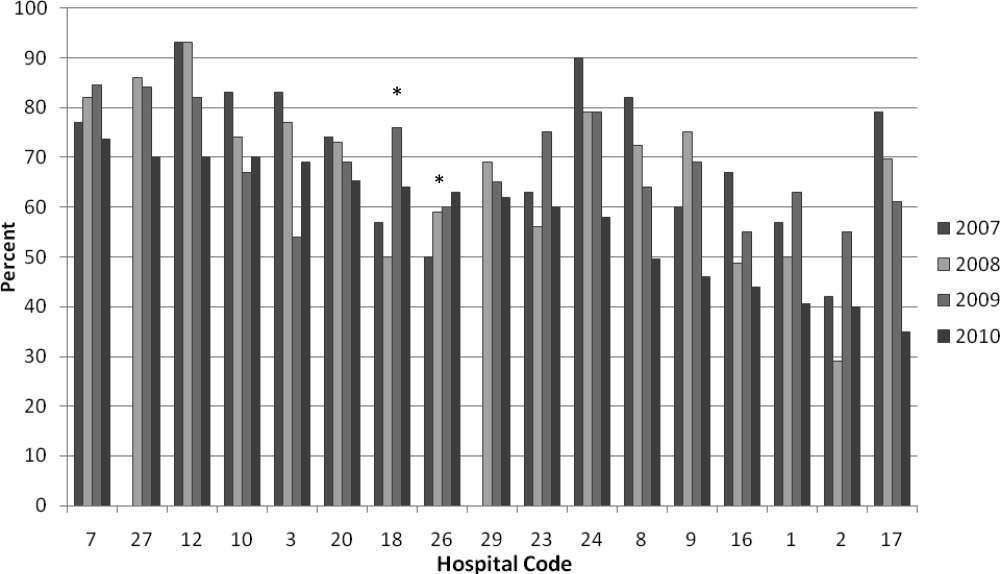

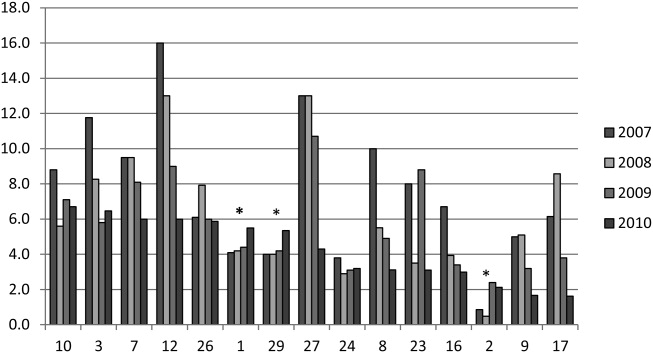

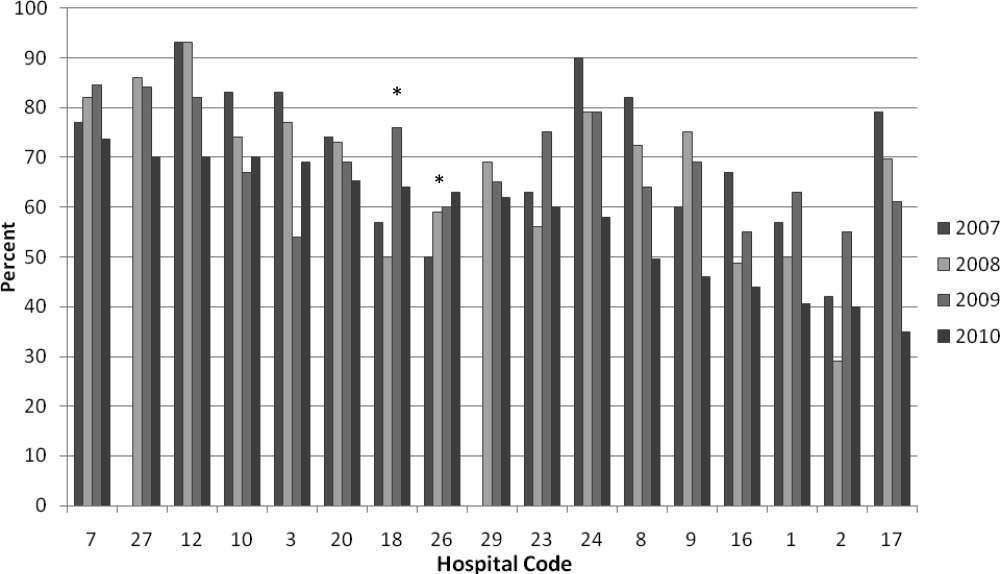

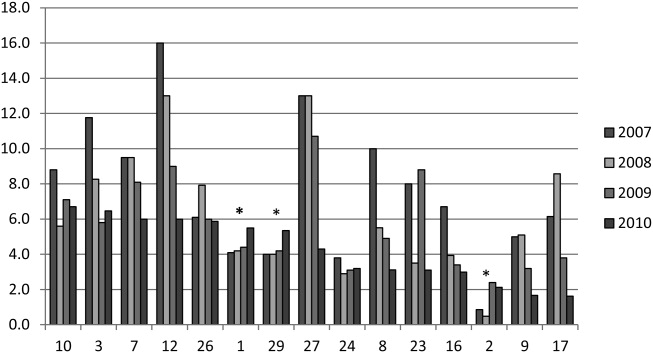

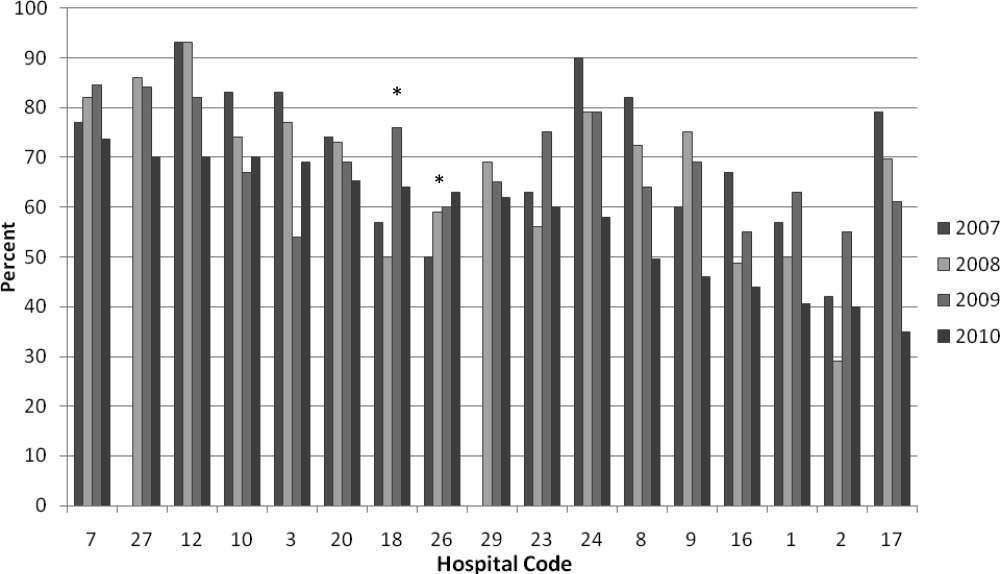

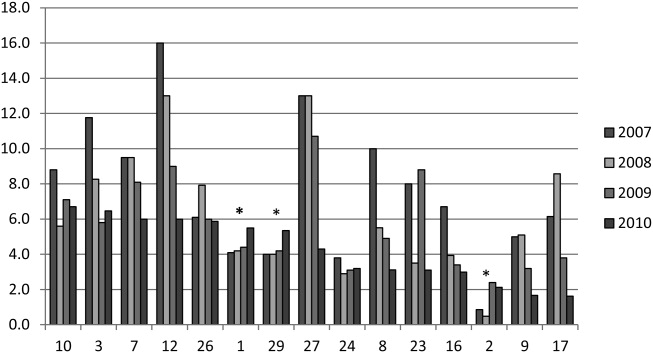

We analyzed within‐hospital trends as well. Figure 1 describes intra‐hospital change over the course of the project for overall bronchodilator usage. In this analysis, 15 of 17 hospitals (88%) achieved a significant decrease in overall bronchodilator utilization by 2010. (Hospitals 27 and 29 were unable to provide 2007 baseline data.) For doses per patient, 15 of 17 institutions provided data on this measure, and 12 of 15 (80%) achieved significant decreases (Figure 2). Of note, the institutions failing to achieve significant decreases in bronchodilator utilization entered the project with utilization rates that were already significantly below network mean at the start of the project. (Institutions failing to improve are denoted with an asterisk in Figures 1 and 2.) Since most institutions made significant improvements in bronchodilator utilization over time, we looked for correlates of failure to decrease utilization. The strongest association for failure to improve during the project period was use of a protocol prior to joining the network (odds ratio [OR] = 11, 95% CI 261).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a significant decline in utilization of bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy in inpatient bronchiolitis within a voluntary quality collaborative focused on benchmarking without employing intensive interventions. This observation is important in that it demonstrates real‐world efficacy for our methods. Prior literature has clearly demonstrated that local bronchiolitis guidelines are effective; however, our data on over 11,000 hospitalizations from a broad array of inpatient settings continue to show a high rate of overutilization. We facilitated dissemination and sharing of guideline‐related tools primarily electronically, and capitalized on perceived peer‐group frustration with inefficient management of a high‐volume, high‐utilization disease. While the project leadership had varying degrees of advanced training in quality improvement methodology, the majority of the site leaders were self‐taught and trained while on the job. Our inclusive collaborative had some success using pragmatic and low‐resource methods which we believe is a novel approach to the issue of overutilization.

These considerations are highlighted given the pressing need to find more efficient and scalable means of bending the cost curve of healthcare in the United States. Learning collaboratives are a relatively new model for improvement, with some history in pediatrics,31, 32 and are attractive because of their potential to generate both widespread capacity for change as well as direct improvement. Both cystic fibrosis31 and neonatology collaboratives32 have been celebrated for their positive impacts on children's healthcare, and both are testaments to the power inherent in creating a community of like‐minded individuals. One of the most popular models for learning collaboratives remains the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series; however, this model is resource intensive in that it typically involves large teams and several yearly face‐to‐face meetings, with significant monetary investment on the part of hospitals. On the other hand, virtual collaboratives have produced mixed results with respect to quality improvement,33 so there is a continued need to maximize our learning about what works efficiently. Our collaborative was able to successfully disseminate tools developed in large academic institutions to be applied in smaller and more varied settings, where resources for quality improvement activities were limited.

One possible reason for any successes in this project was the existence of a well‐known guideline for the management of bronchiolitis published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2006. This guideline recommends primarily symptomatic care, and has a statement supporting the contention that routine use of our targeted therapies is unnecessary. It allows for a trial of bronchodilator, but specifically states that all trials should be accompanied by the use of an objective measure of improvement (typically interpreted to mean a respiratory distress score). A guideline sanctioned by an important national organization of pediatricians was invaluable, and we believe that it should serve as a basis for any nationally promoted inpatient quality measure for this very common pediatric illness. The existence of the AAP guideline also highlights the possibility that our results are merely representative of secular trends in utilization in bronchiolitis care, since we had no control group. The available literature on national guidelines has shown mixed and quite modest impacts in other countries.28, 34 Most of our group took active steps to operationalize the guidelines as part of their participation in this collaborative, though they might have done similar work anyway due to the increasing importance of quality improvement in hospitalist culture over the years of the project.

The project did not demonstrate any impact on steroid utilization, or on rates of obtaining chest radiography or viral testing, despite expressly targeting these widely overused interventions. These modalities are often employed in the emergency department and, as a collaborative of pediatric hospitalists, we did not have specific emergency department participation which we recognize as a major weakness and potential impediment to further progress. We hope to collaborate with our respective emergency departments in the future on these particular measures. We also noted that many institutions were inflexible about foregoing viral testing, due to infection control issues arising from the need to cohort patients in shared rooms based on RSV positivity during the busy winter months. A few institutions were able to alter their infection control policies using the strategy of assuming all children with bronchiolitis had RSV (ie, choosing to use both contact precautions and to wear a mask when entering rooms), though this was not universally popular. Finally, we recognize a missed opportunity in not collecting dose per patient level data for steroids, which might have allowed us to distinguish hospitals with ongoing inpatient utilization of steroids from those with only emergency department usage.

Another significant limitation of this project was the lack of annual assessments of data quality. However, we believe our findings are still useful and important, even with this obvious limitation. Most quality improvement work is done using hospital‐supplied data gleaned from administrative databases, exactly the sources used in this project. Key decisions are made in most hospitals in the country based on data of similar quality. Further limitations of the project relate to the issue of replicability. The disease process we addressed is a major source of frustration to pediatric hospitalists, and our sample likely consisted of the most highly motivated individuals, as they sought out and joined a group with the express purpose of decreasing unnecessary utilization in bronchiolitis. We believe this limitation highlights the likely need for quality measures to emerge organically out of a community of practice when resources are limited, ie, we do not believe we would have had significant success using our methods with an unpopular or externally imposed quality measure.

Although a detailed analysis of costs was beyond the scope of the current project, it is possible that decreased utilization resulted in overall cost savings, despite the fact that our data did not demonstrate a significant change in network‐level average variable direct costs related to bronchiolitis. It has been suggested that such savings may be particularly difficult to demonstrate objectively, especially when the principal costs targeted are labor‐based.35 LOS did not significantly vary during the project, whereas the use of labor‐intensive therapies like nebulized bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy declined. It is, however, quite possible that the decreased utilization we demonstrated was accompanied by a concomitant increase in utilization of other unmeasured therapies.

CONCLUSIONS

A volunteer, peer‐group collaborative focused on benchmarking decreased utilization of bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy in bronchiolitis, though had no impact on overuse of other unnecessary therapies and tests.

Acknowledgements

The following authors have participated in the production of this work by: Conception and design of project: Ralston, Garber, Narang, Shen, Pate; Acquisition of data: Ralston, Garber, Narang, Pope, Lossius, Croland, Bennett, Jewell, Krugman, Robbins, Nazif, Liewehr, Miller, Marks, Pappas, Pardue, Quinonez, Fine, Ryan; Analysis and interpretation of data: Ralston, Garber, Narang, Shen, Pate, Pope, Lossius, Croland, Bennett, Jewell, Krugman, Robbins, Nazif, Liewehr, Miller, Marks, Pappas, Pardue, Quinonez, Fine, Ryan; Drafting the article: Ralston, Garber, Shen; Revising it critically for important intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published: Ralston, Garber, Narang, Shen, Pate, Pope, Lossius, Croland, Bennett, Jewell, Krugman, Robbins, Nazif, Liewehr, Miller, Marks, Pappas, Pardue, Quinonez, Fine, Ryan.

Disclosures: The VIP network receives financial/administrative support from the American Academy of Pediatrics through the Quality Improvement Innovations Network. Dr Ralston receives financial support from the American Academy of Pediatrics as editor of the AAP publication, Hospital Pediatrics. Drs Garber, Narang, Shen, Pate, Pope, Lossius, Croland, Bennett, Jewell, Krugman, Robbins, Nazif, Liewehr, Miller, Marks, Pappas, Pardue, Quinonez, Fine, and Ryan report no conflicts.

- HCUPnet. Kids Inpatient Database 2006. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/. Accessed February 6, 2011.

- , . Recent trends in severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) among US infants, 1997 to 2000. J Pediatr. 2003;143:S127–S132.

- , , , , . Infectious disease hospitalizations among infants in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;121:244–252.

- , . Bronchiolitis. Lancet. 2006;368:312–322.

- , , , , . Rates of hospitalization for respiratory syncytial virus infection among children in Medicaid. J Pediatr. 2000;137:865–870.

- Subcommittee on the Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis, 2004–2006. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1774–1793.

- , , . Bronchiolitis in US emergency departments 1992 to 2000: epidemiology and practice variation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:242–247.

- , , , et al. Practice variation among pediatric emergency departments in the treatment of bronchiolitis. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:353–360.

- , , , . Bronchiolitis management preferences and the influence of pulse oximetry and respiratory rate on the decision to admit. Pediatrics. 2003;111:e45–e51.

- , , , , , . Variations in management of common inpatient pediatric illnesses: hospitalists and community pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2006;118:441–447.

- , , , , . Variation in pediatric hospitalists' use of proven and unproven therapies: a study from the Pediatric Research in Inpatient Settings (PRIS) network. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:292–298.

- , , , et al. Pediatric Investigators Collaborative Network on Infections in Canada (PICNIC) study of admission and management variation in patients hospitalized with respiratory syncytial viral lower respiratory tract infection. J Pediatr. 1996;129:390–395.

- , , , , . Effect of practice variation on resource utilization in infants hospitalized for viral lower respiratory illness. Pediatrics. 2001;108:851–855.

- , . Bronchodilators for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8;(12):CD001266.

- , , . Chest physiotherapy for acute bronchiolitis in pediatric patients between 0 and 24 months old. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD004873.

- , , , et al. Epinephrine for bronchiolitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jun 15;(6):CD003123.

- , , , et al. Glucocorticoids for acute bronchiolitis in infants and young children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Oct 6;(10):CD004878.

- , , , . Efficacy of interventions for bronchiolitis in critically ill infants: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2004;5:482–489.

- , , . Direct medical costs of bronchiolitis hospitalizations in the United States. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):2418–2423.

- , , , et al. Evaluation of an evidence‐based guideline for bronchiolitis. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1334–1341.

- , , . Standardizing the care of bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(8):739–744.

- , , , , , . Decreasing overuse of therapies in the treatment of bronchiolitis by incorporating evidence at the point of care. J Pediatr. 2004;144:703–710.

- , , , , , . Effect of point of care information on inpatient management of bronchiolitis. BMC Pediatr. 2007;7:4.

- , , , et al. A clinical pathway for bronchiolitis is effective in reducing readmission rates. J Pediatr. 2005;147:622–626.

- , , , et al. Sustaining the implementation of an evidence‐based guideline for bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:1001–1007.

- , , , , , . Assessment of the French Consensus Conference for Acute Viral Bronchiolitis on outpatient management: progress between 2003 and 2008 [in French]. Arch Pediatr. 2010;17:125–131.

- , , , , , . Impact of a bronchiolitis guideline: a multisite demonstration project. Chest. 2002;121:1789–1797.

- , , , . Management of acute bronchiolitis: can evidence based guidelines alter clinical practice? Thorax. 2008;63:1103–1109.

- , . The “3 T's” roadmap to transform US health care: the “how” of high quality care. JAMA. 2008;299(19):2319–2321.

- The VIP Network. Available at: http://www.vipnetwork.webs.com. Accessed October 5, 2010.

- , . A story of success: continuous quality improvement in cystic fibrosis in the USA. Thorax. 2011;66:1106–1168.

- , , , , , . NICU practices and outcomes associated with 9 years of quality improvement collaboratives. Pediatrics. 2010;125:437–446.

- , , , et al. Quality improvement projects target health care‐associated infections: comparing virtual collaborative and toolkit approaches. J Hosp Med. 2011;6:271–278.

- , , , , . Impact of consensus development conference guidelines on primary care of bronchiolitis: are national guidelines being followed? J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:651–656.

- , , , . The savings illusion—why clinical quality improvement fails to deliver bottom‐line results. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:e48.

Currently, 3%5% of infants under a year of age will be admitted to a hospital for acute viral bronchiolitis each year, making it the leading cause of hospitalization in children.15 The American Academy of Pediatrics guideline on the diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis advocates primarily supportive care for this self‐limited disease.6 Specifically, the routine use of therapies such as bronchodilators and corticosteroids are not recommended, nor is routine evaluation with diagnostic testing.6 Numerous studies have established the presence of unwarranted variation in most aspects of bronchiolitis care,713 and the current evidence does not support the routine usage of specific interventions in inpatients.1418

Acute bronchiolitis accounts for direct inpatient medical costs of over $500 million per year.19 Based on estimates from the Healthcare Utilization Project Kids' Inpatient Database, acute bronchiolitis is second only to respiratory distress syndrome as the most expensive disease of hospitalized children.1 Although charges may not correlate directly with costs or even the actual intensity of resource utilization, the national bill, based on charges, is approximately 1.4 billion dollars per year.1 Either way, the leading cause of hospitalization in children is expensive and suffers from dramatic variation in care characterized by overutilization of ineffective interventions.

Evidence‐based guidelines for bronchiolitis are readily available and their successful adoption within larger, academic children's hospitals has been demonstrated.2028 However, upwards of 70% of all children in this country are cared for outside of freestanding children's hospitals,1 and very little has been published about wide dissemination of evidence‐based guidelines in these settings.29 In 2008, the Value in Inpatient Pediatrics (VIP) network was created, as an inclusive pediatric inpatient quality improvement collaborative with a focus on linking academic and community‐based hospitalist groups, to disseminate evidence‐based management strategies for bronchiolitis. We hypothesized that group norming, through benchmarking and public goal setting at the level of the hospitalist group, would decrease overall utilization of nonevidence‐based therapies. Specifically, we were trying to decrease the utilization of bronchodilators, steroids, chest physiotherapy, chest radiography, and viral testing in hospitalized children diagnosed with uncomplicated bronchiolitis.

METHODS

Beginning in early 2008, we recruited pediatric hospitalists into a voluntary bronchiolitis quality improvement collaborative from within the community of hospitalists created by the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine. Participants were recruited through open calls at national conferences and mass e‐mails to the section membership through the listserve. The guiding principle for the collaborative was the idea that institutional adoption of evidence‐based disease‐management strategies would result in higher value of care, and that this process could be facilitated by benchmarking local performance against norms created within the larger community. We used group consensus to identify the therapies and tests to benchmark, although the chosen measures meshed with those addressed in the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guideline. Use of bronchodilators, corticosteroids, chest physiotherapy, chest radiography, and viral testing were all felt to be significantly overutilized in participating clinical sites. We were unaware of any published national targets for utilization of these therapies or tests, and none of the participating hospitalist groups was actively benchmarking their utilization against any peer group at the start of the project. Length of stay, rates of readmission within 72 hours of discharge, and variable direct costs were chosen as balancing measures for the project.

We collected data on hospitalizations for bronchiolitis for 4 calendar years, from 2007 through 2010, based on the following inclusion criteria: children under 24 months of age, hospitalized for the primary diagnosis of acute viral bronchiolitis as defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) codes 466.11 and 466.19. We specifically included patients who were in observation status as well as those in inpatient status, and excluded all intensive care unit admissions. Other exclusions were specific ICD‐9 codes for: chronic lung diseases, asthma, chromosomal abnormalities, heart disease, and neurological diseases. We then tracked overall utilization of any bronchodilator (albuterol, levalbuterol, epinephrine, or ipratropium) during the hospitalization, including the emergency department; total number of bronchodilator doses per patient; utilization of any corticosteroids (inhaled or systemic); chest radiography; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) testing; and chest physiotherapy; as well as variable direct costs per hospitalization for each center. A standardized toolkit was provided to participating centers to facilitate data collection. Data was sought from administrative sources, collected in aggregate form and not at the patient level, and no protected health information was collected as part of the project. The project was categorized as exempt by the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio Institutional Review Board, the location of the data repository.

The project began in 2008, though we requested that centers provide 2007 data to supplement our baseline. We held the first group meeting in July 2009 and began the facilitated sharing of resources to promote evidence‐based care, such as guidelines, protocols, respiratory scores, and patient handouts, across sites using data from 2007 and 2008 as our baseline for benchmarking and later assessing any improvement. Centers adopted guidelines at their own pace and we did not require guideline adoption for continued participation. We provided summaries of the available literature by topic, in the event that site leaders wished to give institutional grand rounds or other presentations. All dissemination of guidelines or protocols was done based on the request of the center, and no specific resource was created or sanctioned by the group, though the AAP Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis6 remained a guiding document. Some of our centers participated in more extensive collaborative projects which involved small‐group goal setting, adoption of similar protocols, and conference calls, though this never encompassed more than 25% of the network.

The main product of the project was a yearly report benchmarking each hospital against the network average on each of our chosen utilization measures. The first report was disseminated in July 2009 and included data on calendar year 2007 and 2008, which we considered our group baseline. Most institutions began local Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycles by mid‐2009 using the data we provided as they benchmarked their performance against other members of the collaborative, and these continued through 2010. Hospitals were coded and remained anonymous. However, we publicly honored the high performers within the network at a yearly meeting, and urged these centers to share their tools and strategies, which was facilitated through a project Web site.30 All participation was voluntary, and all costs were borne by individuals or their respective centers.

In order to assess data quality, we undertook a validation project for calendar year 2009. We requested local direct chart review of a 10% sample, or a minimum of 10 charts, to confirm reported utilization rates for the therapies and tests we tracked. Any center with less than 80% accuracy was then asked to review data collection methods and make adjustments accordingly. One center identified and resolved a significant data discrepancy and 2 centers refused to participate in the validation project, citing their participation in a large national database for which there was already a very rigorous data validation process (Child Health Corporation of America's Pediatric Health Information System database). Given that we did not uncover major discrepancies in data quality within our network, we did not request further data validation but rather promoted year‐to‐year consistency of collection methods, seeking to collect the same type/quality of data that hospitals use in their own internal performance assessments.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad InStat, version 3.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Descriptive statistics (including interquartile range ([IQR], the range from 25th to 75th percentile of the data) are provided. Analysis of process measures over the series of years was performed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), as were intra‐hospital comparisons for all measures. Hospitals were not weighted by volume of admissions, ie, the unit of analysis was the hospital and not individual hospitalizations. Data were analyzed for normality using the method of Kolmogorov and Smirnoff, and in cases where normality was not satisfied (steroids and chest physiotherapy), the data were transformed and nonparametric methods were used. Post‐test adjustment for multiple comparisons was done using the TukeyKramer test in cases where ANOVA P values were <0.05. Fisher's exact test was used to analyze contingency tables for categorical variables such as presence or absence of a protocol.

RESULTS

Data encompassing 11,568 bronchiolitis hospitalizations in 17 centers, for calendar years 2007 to 2010, were analyzed for this report. A total of 31 centers ever participated in the project; however, this report is restricted to centers who participated for the entirety of the project from 2008 through 2010, and who consented to have their data reported. Specifically, 18 centers met inclusion criteria and 1 center opted out of the project, leaving the 17 centers described in Table 1. The overall network makeup shifted each year, but was always more than 80% non‐freestanding children's hospitals and approximately 30% urban, as defined as located in a population center of more than 1 million. A large majority of the participants did not have a local bronchiolitis protocol or guideline at the start of the project, although 88% of participants adopted some form of protocolized care by 2010. Calendar years 2007 and 2008 served as our network baseline, with most interventions (in institutions where they occurred) begun by calendar year 2009. The level of intervention varied greatly among institutions, with a few institutions doing nothing more than benchmarking their performance.

| Participating Centers (Alphabetically by State) | Type of Facility | Average Yearly Bronchiolitis Admissions | Approximate Medicaid (%) | Guideline Prior to Joining Project? | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Scottsdale Healthcare Scottsdale, AZ | PEDS | 133 | 26 | No | Suburban |

| Shands Hospital for Children at the University of Florida Gainesville, FL | CHWH | 107 | 59 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital of Illinois Peoria, IL | CHWH | 97 | 15 | No | Suburban |

| Kentucky Children's Hospital Lexington, KY | CHWH | 135 | 60 | Yes | Suburban |

| Our Lady of the Lake Baton Rouge, LA | CHWH | 138 | 70 | No | Suburban |

| The Barbara Bush Children's Hospital Portland, ME | CHWH | 31 | 41 | Yes | Suburban |

| Franklin Square Hospital Center Baltimore, MD | PEDS | 66 | 40 | No | Suburban |

| Anne Arundel Medical Center Annapolis, MD | CHWH | 56 | 36 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital at Montefiore Bronx, NY | CHWH | 220 | 65 | No | Urban |

| Mission Children's Hospital Asheville, NC | CHWH | 112 | 21 | Yes | Suburban |

| Cleveland Clinic Children's Hospital Cleveland, OH | CHWH | 58 | 24 | Yes | Urban |

| Palmetto Health Children's Hospital Columbia, SC | CHWH | 181 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| East Tennessee Children's Hospital Knoxville, TN | FSCH | 373 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| Texas Children's Hospital Houston, TX | FSCH | 619 | 60 | Yes | Urban |

| Christus Santa Rosa Children's Hospital San Antonio, TX | CHWH | 390 | 71 | No | Urban |

| Children's Hospital of The Kings' Daughters Norfolk, VA | FSCH | 303 | 60 | No | Suburban |

| Children's Hospital of Richmond Richmond, VA | CHWH | 40 | 60 | No | Urban |

Mean length of stay (LOS), readmission rates, and variable direct costs did not differ significantly during the project time period. Mean LOS for the network ranged from a low of 2.4 days (IQR, 2.22.8 days) to a high of 2.7 days (IQR, 2.43.1 days), and mean readmission rates ranged from 1.2% (IQR, 0.7%1.8%) to 1.7% (IQR, 0.7%2.5%) during the project. Mean variable direct costs ranged from $1639 (IQR, $1383$1864) to $1767 (IQR, $1365$2320).

Table 2 describes the mean overall utilization of bronchodilators, chest radiography, RSV testing, steroids, and chest physiotherapy among the group from 2007 to 2010. By 2010, we saw a 46% decline in the volume of bronchodilator used within the network, a 3.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.45.8) dose per patient absolute decrease (P < 0.01). We also saw a 12% (95% CI 5%25%) absolute decline in the overall percentage of patients exposed to any bronchodilator (P < 0.01). Finally, there was a 10% (95% CI 3%18%) absolute decline in the overall utilization of any chest physiotherapy (P < 0.01). The project did not demonstrate a significant impact on utilization of corticosteroids, chest radiography, or viral testing, although several centers achieved significant decreases on a local level (data not shown).

| Utilization Measure | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | No. (IQR) | |

| ||||

| Bronchodilator doses per patient (P < 0.01) | 7.9 (4.69.8) | 6.4 (4.08.4) | 5.7 (3.67.6) | 4.3 (3.05.9) |

| Any bronchodilators (P < 0.01) | 70% (59%83%) | 67% (56%77%) | 68% (61%76%) | 58% (46%69%) |

| Chest physiotherapy (P < 0.01) | 14% (5%19%) | 10% (1%8%) | 7% (2%6%) | 4% (1%7%) |

| Chest radiography (P = NS) | 64% (54%81%) | 66% (55%79%) | 64% (60%73%) | 59% (50%73%) |

| Any steroids (P = NS) | 21% (14%26%) | 20% (15%28%) | 21% (14%22%) | 16% (13%25%) |

| RSV testing (P = NS) | 64% (52%84%) | 61% (49%78%) | 62% (50%78%) | 57% (44%75%) |

We analyzed within‐hospital trends as well. Figure 1 describes intra‐hospital change over the course of the project for overall bronchodilator usage. In this analysis, 15 of 17 hospitals (88%) achieved a significant decrease in overall bronchodilator utilization by 2010. (Hospitals 27 and 29 were unable to provide 2007 baseline data.) For doses per patient, 15 of 17 institutions provided data on this measure, and 12 of 15 (80%) achieved significant decreases (Figure 2). Of note, the institutions failing to achieve significant decreases in bronchodilator utilization entered the project with utilization rates that were already significantly below network mean at the start of the project. (Institutions failing to improve are denoted with an asterisk in Figures 1 and 2.) Since most institutions made significant improvements in bronchodilator utilization over time, we looked for correlates of failure to decrease utilization. The strongest association for failure to improve during the project period was use of a protocol prior to joining the network (odds ratio [OR] = 11, 95% CI 261).

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated a significant decline in utilization of bronchodilators and chest physiotherapy in inpatient bronchiolitis within a voluntary quality collaborative focused on benchmarking without employing intensive interventions. This observation is important in that it demonstrates real‐world efficacy for our methods. Prior literature has clearly demonstrated that local bronchiolitis guidelines are effective; however, our data on over 11,000 hospitalizations from a broad array of inpatient settings continue to show a high rate of overutilization. We facilitated dissemination and sharing of guideline‐related tools primarily electronically, and capitalized on perceived peer‐group frustration with inefficient management of a high‐volume, high‐utilization disease. While the project leadership had varying degrees of advanced training in quality improvement methodology, the majority of the site leaders were self‐taught and trained while on the job. Our inclusive collaborative had some success using pragmatic and low‐resource methods which we believe is a novel approach to the issue of overutilization.

These considerations are highlighted given the pressing need to find more efficient and scalable means of bending the cost curve of healthcare in the United States. Learning collaboratives are a relatively new model for improvement, with some history in pediatrics,31, 32 and are attractive because of their potential to generate both widespread capacity for change as well as direct improvement. Both cystic fibrosis31 and neonatology collaboratives32 have been celebrated for their positive impacts on children's healthcare, and both are testaments to the power inherent in creating a community of like‐minded individuals. One of the most popular models for learning collaboratives remains the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Breakthrough Series; however, this model is resource intensive in that it typically involves large teams and several yearly face‐to‐face meetings, with significant monetary investment on the part of hospitals. On the other hand, virtual collaboratives have produced mixed results with respect to quality improvement,33 so there is a continued need to maximize our learning about what works efficiently. Our collaborative was able to successfully disseminate tools developed in large academic institutions to be applied in smaller and more varied settings, where resources for quality improvement activities were limited.

One possible reason for any successes in this project was the existence of a well‐known guideline for the management of bronchiolitis published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 2006. This guideline recommends primarily symptomatic care, and has a statement supporting the contention that routine use of our targeted therapies is unnecessary. It allows for a trial of bronchodilator, but specifically states that all trials should be accompanied by the use of an objective measure of improvement (typically interpreted to mean a respiratory distress score). A guideline sanctioned by an important national organization of pediatricians was invaluable, and we believe that it should serve as a basis for any nationally promoted inpatient quality measure for this very common pediatric illness. The existence of the AAP guideline also highlights the possibility that our results are merely representative of secular trends in utilization in bronchiolitis care, since we had no control group. The available literature on national guidelines has shown mixed and quite modest impacts in other countries.28, 34 Most of our group took active steps to operationalize the guidelines as part of their participation in this collaborative, though they might have done similar work anyway due to the increasing importance of quality improvement in hospitalist culture over the years of the project.