User login

In the Literature: Research You Need to Know

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

Clinical question: What is the relationship between well-being and demographic factors, educational debt, and medical knowledge in internal-medicine residents?

Background: Physician distress during training is common and can negatively impact patient care. There has never been a study of internal-medicine residents nationally that examined the patterns of distress across demographic factors or the association of these factors with medical knowledge.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: U.S. internal-medicine residency programs.

Synopsis: Of the 21,208 U.S. internal-medicine residents who completed the 2008 in-training examination, 77.3% had both survey and demographic data available for analysis. Nearly 15% of these 16,394 residents rated quality of life “as bad as it can be” or “somewhat bad,” and 32.9% felt somewhat or very dissatisfied with work-life balance.

Overall burnout, high levels of weekly emotional exhaustion, and weekly depersonalization were reported by 51.5%, 45.8%, and 28.9% of residents, respectively. Symptoms of emotional exhaustion decreased as training increased, while depersonalization increased after the first postgraduate year. Residents reporting quality of life “as bad as it can be,” emotional exhaustion, or debt greater than $200,000 had mean exam scores 2.7, 4.2, and 5 points, respectively, lower than others surveyed.

Although unlikely given the study design, nonresponse bias could affect these results. Not all demographic variables or domains of well-being were studied, and self-reported educational debt could have been misclassified. Nonetheless, findings suggest that distress remains among residents despite the changes made to duty-hour regulations in 2003.

Bottom line: Suboptimal quality of life and burnout were common among internal-medicine residents nationally; symptoms of burnout were associated with higher debt and lower exam scores.

Citation: West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306:952-960.

Visit our website for more physician reviews of HM-related research.

The EHR Report Podcast: Integrated Smartphones and EHRs

Welcome to the EHR Report Podcast!

In this edition of the EHR Report Podcast, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte take a look at how handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and PDAs can fit into an EHR system.

To download this podcast, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the EHR Report Podcast!

In this edition of the EHR Report Podcast, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte take a look at how handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and PDAs can fit into an EHR system.

To download this podcast, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Welcome to the EHR Report Podcast!

In this edition of the EHR Report Podcast, Dr. Neil Skolnik and Dr. Chris Notte take a look at how handheld devices such as smartphones, tablets, and PDAs can fit into an EHR system.

To download this podcast, click here.

To listen via this Web page, click on the player below:

Join Team Hospitalist

Team Hospitalist is the only reader-involvement program of its kind in hospital medicine. The 12-member advisory panel provides invaluable information about the current state of hospital medicine, including the daily issues facing hospitalists, group leaders, and their patients. Team members offer ideas for articles, assist writers with contacts and expert sources, and participate in monthly conference calls to discuss new ideas.

The team will seat new members for tw0-year terms at HM12 in San Diego, April 1-4. Team members must be an SHM member in good standing and be able to attend SHM's annual meetings. To apply, email the editors your CV and a letter of interest no later than Feb. 15, 2012.

Team Hospitalist is the only reader-involvement program of its kind in hospital medicine. The 12-member advisory panel provides invaluable information about the current state of hospital medicine, including the daily issues facing hospitalists, group leaders, and their patients. Team members offer ideas for articles, assist writers with contacts and expert sources, and participate in monthly conference calls to discuss new ideas.

The team will seat new members for tw0-year terms at HM12 in San Diego, April 1-4. Team members must be an SHM member in good standing and be able to attend SHM's annual meetings. To apply, email the editors your CV and a letter of interest no later than Feb. 15, 2012.

Team Hospitalist is the only reader-involvement program of its kind in hospital medicine. The 12-member advisory panel provides invaluable information about the current state of hospital medicine, including the daily issues facing hospitalists, group leaders, and their patients. Team members offer ideas for articles, assist writers with contacts and expert sources, and participate in monthly conference calls to discuss new ideas.

The team will seat new members for tw0-year terms at HM12 in San Diego, April 1-4. Team members must be an SHM member in good standing and be able to attend SHM's annual meetings. To apply, email the editors your CV and a letter of interest no later than Feb. 15, 2012.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Med-Peds Physicians Make their Mark

Every day in the life of an internist and pediatrician, clinical questions arise. For HM practitioners, treating patients with chronic illnesses who are also on the cusp of adulthood presents a new set of challenges.

That’s when physicians trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) can lend their expertise. Once a physician successfully completes a four-year combined med-peds residency program, he or she may take the board certification exams in both internal medicine and pediatrics. Med-peds programs are now accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) as a combined program instead of separate accreditation in internal medicine and pediatrics.

“The best solution would be to have more med-peds specialists as hospitalists,” says Moises Auron, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic. They “can facilitate the transition by identifying these patients and providing an increased sensibility to the pediatric provider to ‘let the patient go’ and to open new insights to the adult providers to welcome those patients,” he says.

Broad-Based Training

—Moises Auron, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

A med-peds physician can care for people of all ages—from newborns to geriatric patients. He or she is prepared for the demands of private practice, academic medicine, hospitalist programs, and fellowships, according to the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association.

While med-peds residency offers exceptional training for primary care, it also leaves open the option of pursuing a subspecialty in either internal medicine or pediatrics, or both. Subspecialties include cardiology, infectious disease, pulmonary/critical care, women’s health, and sports medicine.

Med-peds celebrated its 40th anniversary as a formal training option in 2007. There are currently about 1,400 med-peds residents in training and about 6,300 med-peds physicians in practice, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ section on med-peds.

This broad-based training helps ensure smoother transitions of care. “It’s incumbent upon adult physicians to make the pediatric physicians aware of what services they offer, and also for the pediatricians to reach out with specific patients and refer them to adult physicians,” says W. Benjamin Rothwell, MD, associate program director of the med-peds residency at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans.

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

Every day in the life of an internist and pediatrician, clinical questions arise. For HM practitioners, treating patients with chronic illnesses who are also on the cusp of adulthood presents a new set of challenges.

That’s when physicians trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) can lend their expertise. Once a physician successfully completes a four-year combined med-peds residency program, he or she may take the board certification exams in both internal medicine and pediatrics. Med-peds programs are now accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) as a combined program instead of separate accreditation in internal medicine and pediatrics.

“The best solution would be to have more med-peds specialists as hospitalists,” says Moises Auron, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic. They “can facilitate the transition by identifying these patients and providing an increased sensibility to the pediatric provider to ‘let the patient go’ and to open new insights to the adult providers to welcome those patients,” he says.

Broad-Based Training

—Moises Auron, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

A med-peds physician can care for people of all ages—from newborns to geriatric patients. He or she is prepared for the demands of private practice, academic medicine, hospitalist programs, and fellowships, according to the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association.

While med-peds residency offers exceptional training for primary care, it also leaves open the option of pursuing a subspecialty in either internal medicine or pediatrics, or both. Subspecialties include cardiology, infectious disease, pulmonary/critical care, women’s health, and sports medicine.

Med-peds celebrated its 40th anniversary as a formal training option in 2007. There are currently about 1,400 med-peds residents in training and about 6,300 med-peds physicians in practice, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ section on med-peds.

This broad-based training helps ensure smoother transitions of care. “It’s incumbent upon adult physicians to make the pediatric physicians aware of what services they offer, and also for the pediatricians to reach out with specific patients and refer them to adult physicians,” says W. Benjamin Rothwell, MD, associate program director of the med-peds residency at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans.

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

Every day in the life of an internist and pediatrician, clinical questions arise. For HM practitioners, treating patients with chronic illnesses who are also on the cusp of adulthood presents a new set of challenges.

That’s when physicians trained in both internal medicine and pediatrics (med-peds) can lend their expertise. Once a physician successfully completes a four-year combined med-peds residency program, he or she may take the board certification exams in both internal medicine and pediatrics. Med-peds programs are now accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) as a combined program instead of separate accreditation in internal medicine and pediatrics.

“The best solution would be to have more med-peds specialists as hospitalists,” says Moises Auron, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic. They “can facilitate the transition by identifying these patients and providing an increased sensibility to the pediatric provider to ‘let the patient go’ and to open new insights to the adult providers to welcome those patients,” he says.

Broad-Based Training

—Moises Auron, MD, assistant professor of medicine and pediatrics, Cleveland Clinic

A med-peds physician can care for people of all ages—from newborns to geriatric patients. He or she is prepared for the demands of private practice, academic medicine, hospitalist programs, and fellowships, according to the National Med-Peds Residents’ Association.

While med-peds residency offers exceptional training for primary care, it also leaves open the option of pursuing a subspecialty in either internal medicine or pediatrics, or both. Subspecialties include cardiology, infectious disease, pulmonary/critical care, women’s health, and sports medicine.

Med-peds celebrated its 40th anniversary as a formal training option in 2007. There are currently about 1,400 med-peds residents in training and about 6,300 med-peds physicians in practice, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics’ section on med-peds.

This broad-based training helps ensure smoother transitions of care. “It’s incumbent upon adult physicians to make the pediatric physicians aware of what services they offer, and also for the pediatricians to reach out with specific patients and refer them to adult physicians,” says W. Benjamin Rothwell, MD, associate program director of the med-peds residency at Tulane University School of Medicine in New Orleans.

Susan Kreimer is a freelance medical writer based in New York.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Shifting Strategies Can Make Physician Workloads Manageable

As hospitalists have learned, sometimes a workload problem is related to how that work is apportioned. The trick is to devise a solution that’s good for patients, doctors, and the hospital.

Adam Singer, MD, CEO of North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company, has long advocated changing from a shift-based model to a more full-time model that expands the number of days worked per month. Although the concept has faced resistance from many rank-and-file hospitalists, Dr. Singer argues that the latter model means that more staff will be available to care for patients on any given day, leading to a lower and more manageable average census. Dr. Singer concedes that switching to a full-time model can be a “painful process,” but it’s one that has led to improved patient outcomes, higher revenues, and more sustainable workloads.

John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that titrating the same annual workload over more shifts is desirable. “If you work a small number of days in a year, then every day you work, you’re going to get smacked,” says Dr. Nelson, co-founder of SHM and longtime practice management columnist for The Hospitalist. “It’s going to be hard. And that’s just not smart. It’s not a good idea.”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice, Overlake Hospital Medical Center, Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder

Dr. Nelson worries that a straightforward, Monday-to-Friday model with periodic weekend responsibilities, though, can be disruptive to doctor-patient continuity. Another strategy, he says, is to take each doctor’s workload preferences into account when devising a practice’s schedule, with compensation distributed accordingly. At one practice in the Pacific Northwest, for example, the hospitalists all decided they wanted to work about half as much as they were. Their pay dropped accordingly, Dr. Nelson says, providing the necessary funds for hiring new doctors to pick up the slack.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist in Seattle.

As hospitalists have learned, sometimes a workload problem is related to how that work is apportioned. The trick is to devise a solution that’s good for patients, doctors, and the hospital.

Adam Singer, MD, CEO of North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company, has long advocated changing from a shift-based model to a more full-time model that expands the number of days worked per month. Although the concept has faced resistance from many rank-and-file hospitalists, Dr. Singer argues that the latter model means that more staff will be available to care for patients on any given day, leading to a lower and more manageable average census. Dr. Singer concedes that switching to a full-time model can be a “painful process,” but it’s one that has led to improved patient outcomes, higher revenues, and more sustainable workloads.

John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that titrating the same annual workload over more shifts is desirable. “If you work a small number of days in a year, then every day you work, you’re going to get smacked,” says Dr. Nelson, co-founder of SHM and longtime practice management columnist for The Hospitalist. “It’s going to be hard. And that’s just not smart. It’s not a good idea.”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice, Overlake Hospital Medical Center, Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder

Dr. Nelson worries that a straightforward, Monday-to-Friday model with periodic weekend responsibilities, though, can be disruptive to doctor-patient continuity. Another strategy, he says, is to take each doctor’s workload preferences into account when devising a practice’s schedule, with compensation distributed accordingly. At one practice in the Pacific Northwest, for example, the hospitalists all decided they wanted to work about half as much as they were. Their pay dropped accordingly, Dr. Nelson says, providing the necessary funds for hiring new doctors to pick up the slack.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist in Seattle.

As hospitalists have learned, sometimes a workload problem is related to how that work is apportioned. The trick is to devise a solution that’s good for patients, doctors, and the hospital.

Adam Singer, MD, CEO of North Hollywood, Calif.-based IPC: The Hospitalist Company, has long advocated changing from a shift-based model to a more full-time model that expands the number of days worked per month. Although the concept has faced resistance from many rank-and-file hospitalists, Dr. Singer argues that the latter model means that more staff will be available to care for patients on any given day, leading to a lower and more manageable average census. Dr. Singer concedes that switching to a full-time model can be a “painful process,” but it’s one that has led to improved patient outcomes, higher revenues, and more sustainable workloads.

John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice at Overlake Hospital Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., agrees that titrating the same annual workload over more shifts is desirable. “If you work a small number of days in a year, then every day you work, you’re going to get smacked,” says Dr. Nelson, co-founder of SHM and longtime practice management columnist for The Hospitalist. “It’s going to be hard. And that’s just not smart. It’s not a good idea.”

—John Nelson, MD, MHM, FACP, medical director of the hospitalist practice, Overlake Hospital Medical Center, Bellevue, Wash., SHM co-founder

Dr. Nelson worries that a straightforward, Monday-to-Friday model with periodic weekend responsibilities, though, can be disruptive to doctor-patient continuity. Another strategy, he says, is to take each doctor’s workload preferences into account when devising a practice’s schedule, with compensation distributed accordingly. At one practice in the Pacific Northwest, for example, the hospitalists all decided they wanted to work about half as much as they were. Their pay dropped accordingly, Dr. Nelson says, providing the necessary funds for hiring new doctors to pick up the slack.

Bryn Nelson is a freelance medical journalist in Seattle.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Hospitalist, IHO president discuss how hospitals become overwhelmed with patients

Click here to listen to Drs. Knight and Litvak

Click here to listen to Drs. Knight and Litvak

Click here to listen to Drs. Knight and Litvak

Contribution of Predischarge ID Consult

With dramatically increasing costs of healthcare, it has become increasingly necessary for healthcare providers to demonstrate value in the delivery of care. Porter and Teisberg have strongly advocated that healthcare reform efforts should focus on improving value rather than limiting cost, with value being defined as quality per unit cost.1 However, it has been pointed out that value means different things to different people.2 The biggest challenge in defining value stems mainly from the difficulty in defining quality, because it, too, means vastly different things to different people. Modern medicine is increasingly characterized by multidisciplinary care. With limited or shrinking resources, it will become necessary for individual specialists to describe and articulate, in quantitative terms, their specific contributions to the overall outcome of individual patients.

Previous publications have provided broad descriptions of the value provided by infectious disease (ID) specialists in the domains of sepsis, infection control, outpatient antibiotic therapy, antimicrobial stewardship, and directive care and teaching.3, 4 Studies have also shown the value of ID physicians in specific disease conditions. ID consultation is associated with lower mortality5, 6 and lower relapse rates7 in hospitalized patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. In another study evaluating the impact of ID consultants, patients seen by ID consultants had longer lengths of hospital stay, longer intensive care unit lengths of stay, and higher antibiotic costs than matched controls not seen by ID consultants.8 It can be argued that a major limitation of the study was that controls were not matched for the ID diagnosis, nor for the causative microorganisms, but it is clear that ID physicians are challenged to demonstrate their contribution to the care of patients.

A unique activity of ID physicians is the management of community‐based parenteral anti‐infective therapy (CoPAT). At Baystate Medical Center, a policy of mandatory ID consultation was instituted for patients leaving hospital on parenteral antibiotics. A study was conducted on the impact of predischarge ID consultation for 44 patients who were not already being followed by the ID service. The study documented change from intravenous (IV) to oral formulation, change of antibiotic choice, and change of dose/duration of treatment in a substantial proportion of patients.9 These are significant changes, but ID consultation contributes more than the themes explored in the study.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ID consultation when consulted for CoPAT, an activity specific to ID practice, in a different institution, and using an expanded definition of medical contribution.

METHODS

The Cleveland Clinic's Department of Infectious Disease has 24 staff physicians and 11 inpatient ID consultative services. These include: 2 solid organ transplant services; a bone marrow transplant and oncologic service; 2 infective endocarditis/cardiac device infection services; an intensive care unit (ICU) service; a bone and joint infection service; a neuroinfection service; and 3 general ID consult services. Consultative services are provided 7 days a week. At the Cleveland Clinic, ID consultation is required prior to discharge on parenteral antibiotic therapy.10, 11 ID consultation for CoPAT usually occurs when the primary service deems the patient is close to being discharged from hospital. This circumstance allows for assessing the specific contribution of ID physicians beyond that of the primary service and other consulting services.

Case Ascertainment

The study was approved by the institutional review board. In February 2010, an electronic form for requesting ID consultations had been introduced into the computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system at the Cleveland Clinic. One of the required questions on the form was whether the consultation was regarding CoPAT, with options of Yes, No, or Not sure. These electronic ID consultation requests were screened to identify consultation requests for this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All adult ID consultations between February 11, 2010 and May 15, 2010 for which the CoPAT consult? field was marked Yes were included in the study. All other consultations, including not sure for CoPAT, were excluded.

Definitions

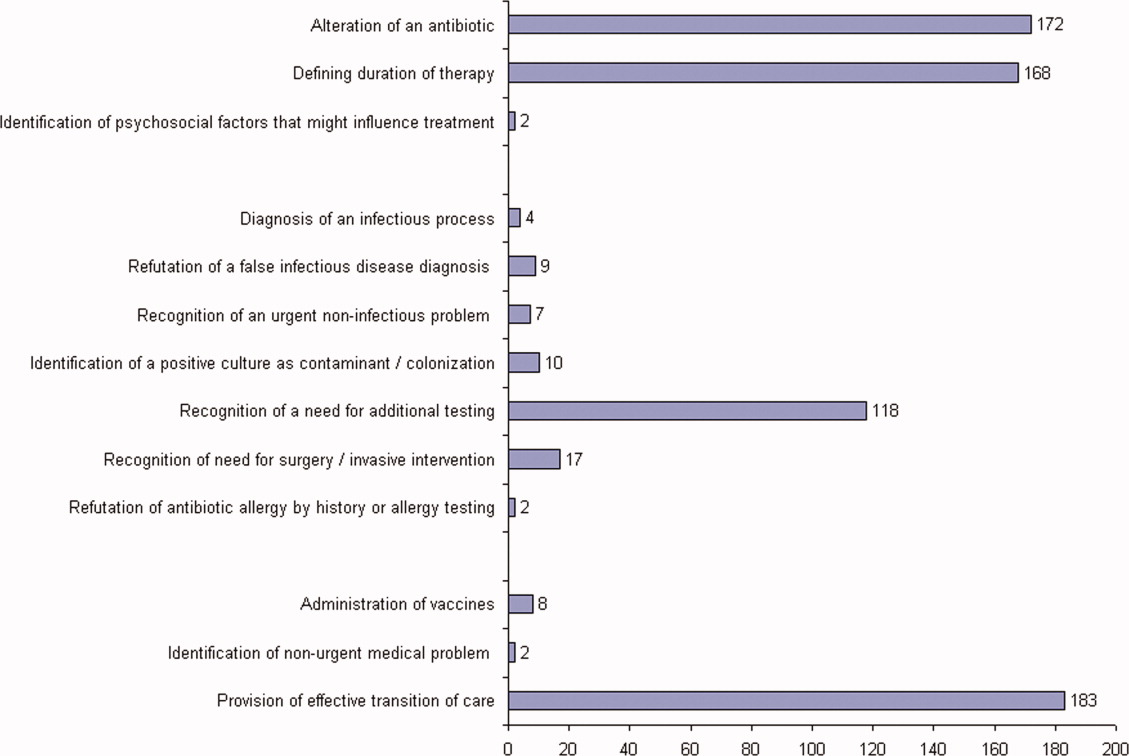

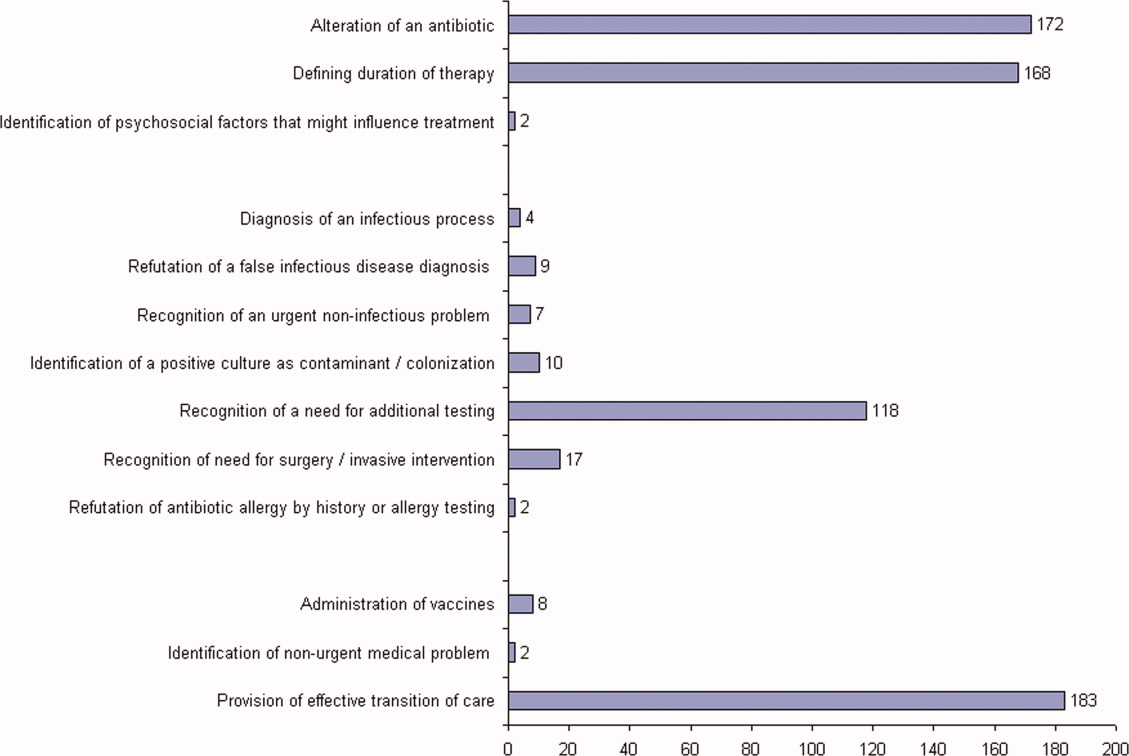

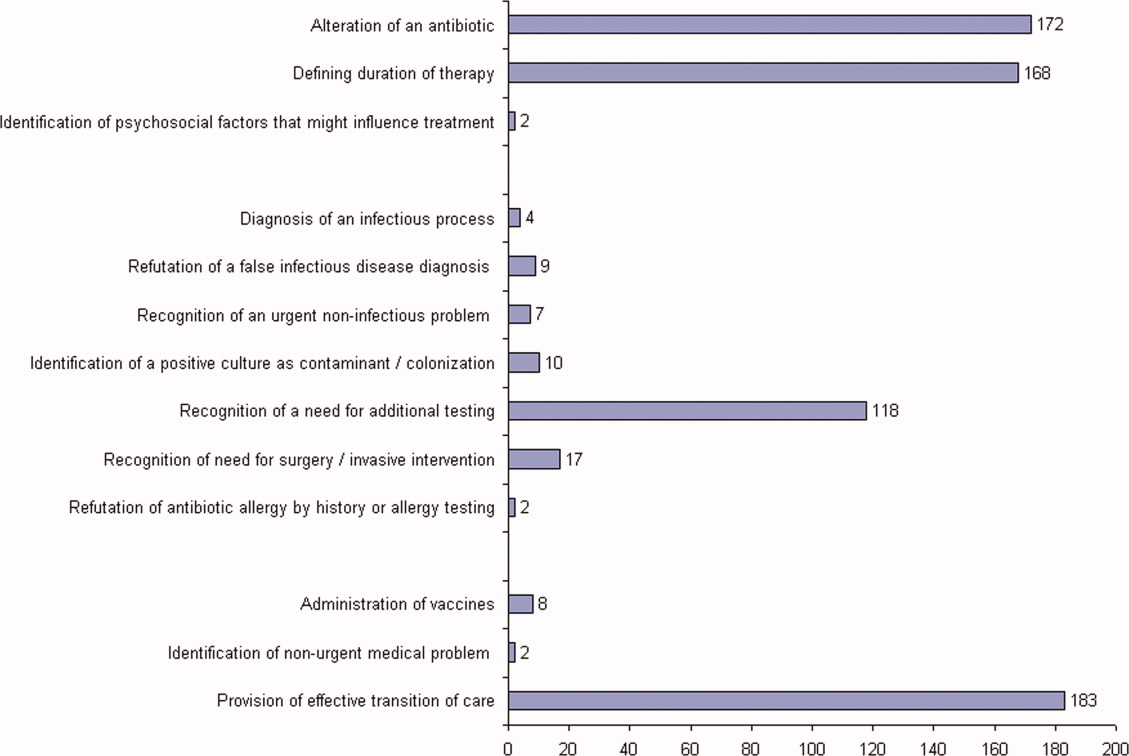

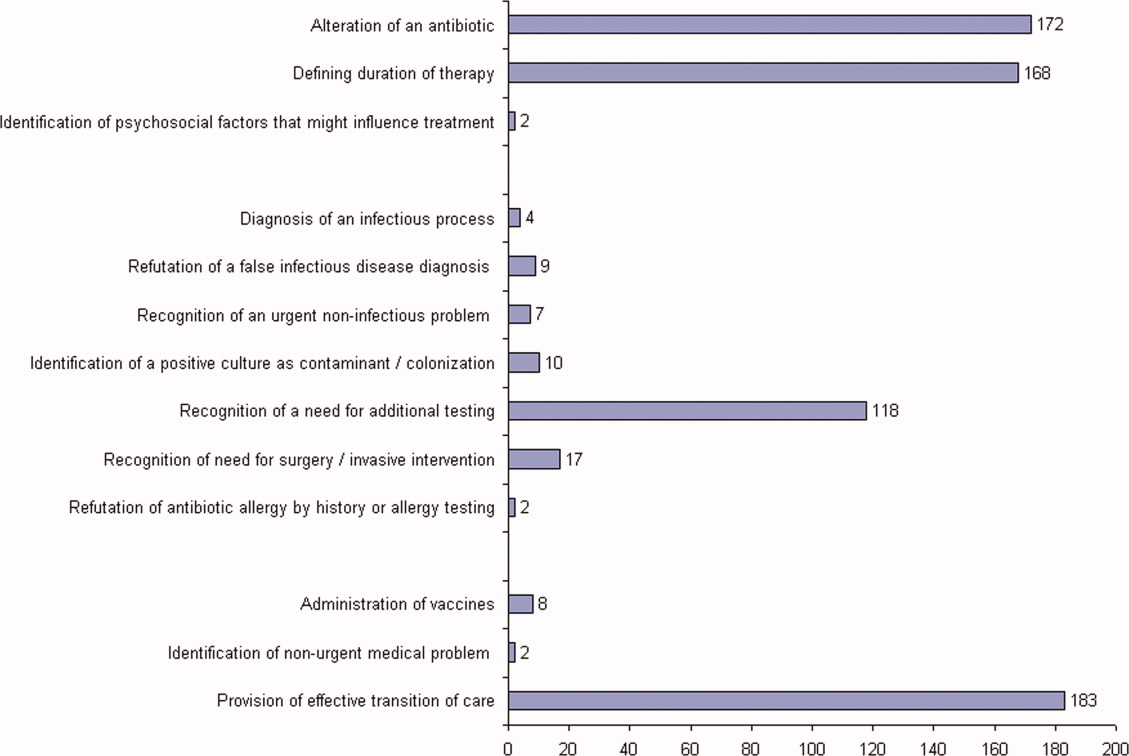

The first ID consultation during a hospitalization was considered an initial consultation. ID consultations for patients whom an ID service had previously seen during the same hospitalization were deemed reconsultations. Value provided was defined as contribution of the ID consultation team in the following domains: 1) optimization of antimicrobial therapy, 2) significant change in patient assessment, 3) additional medical care contribution. Specific contributions included in each domain are outlined in Table 1.

|

| Domain 1: Optimization of antibiotic therapy |

| Alteration of an antibiotic (change of antibiotic or route of administration) |

| Defining duration of therapy |

| Identification of psychosocial factors (eg, injection drug use) that influence treatment |

| Domain 2: Significant change in patient assessment |

| Diagnosis of an infectious process |

| Better appreciation of extent of disease |

| Refutation of a false infectious disease diagnosis |

| Recognition of a noninfectious process needing urgent attention |

| Identification of a positive culture as contaminant/colonization |

| Recognition of a need for additional testing (testing needed to arrive at a diagnosis or clarify a treatment plan before a patient could be safely discharged from hospital) |

| Recognition of need for surgery/emnvasive intervention |

| Refutation of antibiotic allergy by history or allergy testing |

| Domain 3: Additional medical care contribution |

| Administration of vaccines |

| Identification of an unrecognized medical problem that needed to be addressed after discharge from hospital |

| Provision of effective transition of care (ensuring that the same ID physician who saw the patient in hospital followed the patient after discharge from hospital) |

Data Collected

For each ID consultation episode, clinicians' notes were reviewed from the day of the ID consultation to the day the patient was discharged from hospital or the day the ID service signed off, whichever happened sooner. Results of recommended tests were followed up to determine if results led to a change in patient assessment. Data elements collected for each consultation episode included patient age, gender, race, date of hospitalization, date of discharge, date of ID consultation or reconsultation, primary service, and documentation of ID service contributions. Data were collected and entered in a Microsoft Access relational database. To minimize bias, the data collection was performed by physicians who had not participated in the care of the patient.

Analysis

The proportion of ID consultations in which the ID team contributed in the defined domains were enumerated, and described for the group overall and also separately for initial consultations and reconsultations.

RESULTS

In the time period studied, there were 1326 CPOE requests for ID consultation. The response to the question, CoPAT consult? was Yes for 304, No for 507, and Not sure for 515 requests. Of the 304 consultation requests marked Yes, 41 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: no ID consultation note (21), wrong service consulted (8), consultation request placed while the ID service was already following the patient (7), and duplicate consultation request (5). The remaining 263 consultation requests corresponded to 1 or more CoPAT consultation requests for 249 patients (across different hospitalizations). Of the 263 consultation requests, 172 were initial consultations, while the remaining 91 were reconsultations (patients not actively being followed by the ID service, but previously seen during the same hospitalization).

Consultation characteristics are outlined in Table 2. The most common group of infections for which CoPAT was sought was bone and joint infections, accounting for over 20% of the consultation requests. CoPAT consultations were requested a median of 4 days after hospitalization. Patients were discharged from hospital a median of 3 days after they were seen by the ID service. ID consultation did not delay discharge. The ID service usually saw the patient the same day, and followed the patient in hospital for a median of 1 day. There was no difference in hospital days after consult for patients who did not need antibiotics versus those who did.

| Characteristic | Initial Consultation [172] n (%)* | Reconsultation [91] n (%)* | Overall [263] n (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Patient age in years, mean (SD) | 58 (14) | 62 (13) | 59 (14) |

| Male gender | 98 (60) | 91 (56) | 149 (57) |

| Caucasian race | 126 (73) | 74 (81) | 200 (76) |

| Services requesting consults (5 most common overall) | |||

| Medicine | 41 (17) | 14 (15) | 55 (21) |

| Orthopedics | 34 (14) | 0 (0) | 34 (13) |

| Hematology/Oncology | 16 (7) | 10 (11) | 26 (10) |

| Cardiology | 9 (4) | 15 (16) | 24 (9) |

| Gastroenterology | 14 (6) | 5 (5) | 19 (7) |

| Consult diagnosis (5 most common overall) | |||

| Bone and joint infection | 45 (26) | 9 (10) | 54 (21) |

| Skin or soft tissue infection or rash | 21 (12) | 8 (9) | 29 (11) |

| Endocarditis or cardiac device infection | 7 (4) | 15 (16) | 22 (8) |

| IV catheter or other endovascular infection | 9 (5) | 8 (9) | 17 (6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 (7) | 5 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Days from admission to ID consult, median (IQR) | 4 (1‐11) | 7 (2‐19) | 4 (1‐14) |

| Days to respond to consult request, median (IQR) | 0 (0‐1) | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐0) |

| Days from ID consult to discharge, median (IQR) | 3 (2‐7) | 2 (1‐4.5) | 3 (1‐6) |

ID consultation provided value in at least 1 domain in 260 of the 263 consultations. This included optimization of antimicrobial treatment in 84%, significant alteration of patient assessment in 52%, and additional medical care contribution in 71% of consultations. Substantial contributions were made in all domains in both initial consultations and in reconsultations. Specific ID contributions within each of the domains are shown in Figure 1. There was wide overlap of contributions across the 3 domains for individual consultations (Figure 2), with contributions in all domains occurring in 34% of consultations. CoPAT was deemed not to be necessary in 27% of consultations. Among patients who did not require CoPAT, 60% received oral antibiotics and 40% were deemed not to need any antibiotics at hospital discharge. Among the patients discharged on CoPAT, a follow‐up appointment with a Cleveland Clinic ID physician familiar with the patient was set up 86% of the time; the rest either followed up with another physician or it was deemed that a scheduled follow‐up ID visit was not necessary.0

DISCUSSION

Physicians practicing in the specialty of infectious diseases face challenges and opportunities, as they adapt to changing demands within hospital practice in regard to reimbursement in an Accountable Care environment. Other challenges include emerging infections, antimicrobial resistance, need for antimicrobial stewardship, and increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients.12 From a health systems perspective, the overall value of care provided by the entire organization, and overall outcomes, are ultimately what matter. However, healthcare administrators need an appreciation of contributions of individual providers and specialties to fairly allocate resources and compensation for care provided. Articulating unique contributions is particularly challenging for individuals or services that provide purely cognitive input. Shrinking healthcare resources makes it critically important for cognitive specialists to be able to define their unique role in the care of patients with complex problems.

Our study found that a major contribution of ID consultation for CoPAT is that the process identifies a large number of patients who do not need CoPAT, thus effecting a powerful antimicrobial stewardship function. In our study, CoPAT was deemed unnecessary 27% of the time. The Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy emphasize the importance of careful evaluation of patients considered for parenteral antibiotics outside the hospital setting.13 The focus on careful selection of appropriate patients for CoPAT has been a cornerstone of the Cleveland Clinic model of care. Nearly 30 years ago, we found that outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy was unnecessary or not feasible in 40% of the patients referred for evaluation.10 If we adjust the numbers with the assumption that reimbursement issues present at that time are now less of an issue, the proportion of patients who were referred for CoPAT but not discharged on it was 29%, a figure remarkably similar to that found in the current study.

Another major contribution of ID consultation is the provision of effective transition of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. Frequent occurrence of postdischarge adverse events has been recognized as a problem in clinical practice.14 Primary care physicians are rarely involved in discussions about hospital discharge.15 A consensus conference including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, and Society of General Internal Medicine, convened in July 2007 to address quality gaps in transitions of care between inpatient and outpatient settings. It identified 5 principles for effective care transitions: accountability, communication, timeliness, patient and family involvement, and respect for the hub of coordination of care.16 Recognizing gaps in care transition, hospitalists in a hospital‐based infusion program developed a model of care that successfully bridged the hospital‐to‐home care transition for patients who could return to hospital for daily antimicrobial infusions.17 In our system, ID physicians take ownership for directing parenteral antibiotic therapy for the episode of illness, specifying the physician, date, and time of follow‐up before the patient is discharged from hospital, thereby essentially satisfying the principles of effective care transitions identified. The purpose of the ID follow‐up is not to replace other follow‐up care for patients but to ensure safe transition of care while treating an episode of infection.

Attribution of identified contributions to the ID consultation could be done because our study was limited to CoPAT consultations. Such consultations typically occur when patients are deemed close to hospital discharge by the primary service. There should be little controversy about attribution of cognitive input in such consultations, because from the primary service's perspective, the patient is ready or almost ready to be discharged from hospital. It would be fair to state that most of the identified contributions in the study would not have occurred had it not been for the ID consultation.

We acknowledge that the study suffers from many limitations. The biggest limitation is that the contribution elements are defined by ID physicians and sought in the medical record by physicians from the same specialty. This arrangement certainly has potential for significant bias. To limit this bias, data collection was performed by physicians who had not participated in the care of the patient. In addition, we only could assess what was documented in the electronic health record. Our study found that alteration of antibiotic therapy was a substantial contribution, however, documentation of recommendation to change antibiotics in the medical record rarely specified exactly why the change was recommended. Reasons for antibiotic change recommendations included bug‐drug mismatch, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) considerations, pharmacokinetic considerations, adverse effects, convenience of dosing, drug interactions, and insurance coverage. However, it is not possible to quantify the specific contribution of each of these reasons, in a retrospective study, without making assumptions about why specific ID physicians made specific antibiotic change recommendations. There may have been more contributions that might not have been apparent on a retrospective chart review. The lack of a control group also lessens the impact of our findings. We could not have a control group, because no patient is discharged from the Cleveland Clinic on CoPAT without having been seen by an ID physician. Mandatory ID consultation for CoPAT has previously been shown to reduce costs,9 however, our study was not designed to evaluate cost.

The perceived value of ID consultation in our institution can be appreciated when one considers the longstanding institutional policy of requiring ID consultation for CoPAT.10, 11 The perpetuation of this tradition in the hospital is testament to the presumption that mandatory ID consultation is seen to be of value by the institution.

In summary, ID consultation in our institution contributes to the care of inpatients being considered for CoPAT by substantially reducing unnecessary parenteral antibiotic use, optimizing antibiotic therapy, recognizing need for additional testing before discharge from hospital, and by providing effective transition of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

- ,.How physicians can change the future of health care.JAMA.2007;297:1103–1111.

- .Value of the infectious diseases specialist.Clin Infect Dis.1997;24:456.

- ,,, et al.The value of an infectious diseases specialist.Clin Infect Dis.2003;36:1013–1017.

- ,,,,,.The value of infectious diseases specialists: non‐patient care activities.Clin Infect Dis.2008;47:1051–1063.

- ,,,,.The value of infectious diseases consultation in Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.Am J Med.2010;123:631–637.

- ,,,,.Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia.Medicine (Baltimore).2009;88:263–267.

- ,,, et al.Outcome of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia according to compliance with recommendations of infectious diseases specialists: experience with 244 patients.Clin Infect Dis.1998;27:478–486.

- ,,.Infectious diseases consultation: impact on outcomes for hospitalized patients and results of a preliminary study.Clin Infect Dis.1997;24:468–470.

- ,,.Impact of mandatory inpatient infectious disease consultation on outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy.Am J Med Sci.2005;330:60–64.

- ,.Home intravenous antibiotic therapy: a team approach.Ann Intern Med.1983;99:388–392.

- ,,.Transitioning antimicrobial stewardship beyond the hospital: the Cleveland Clinic's community‐based parenteral anti‐infective therapy (CoPAT) program.J Hosp Med.2011;6(suppl 1):S24–S30.

- ,,.Professional challenges and opportunities in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Europe.Lancet Infect Dis.2011;11:408–415.

- ,,, et al.Practice guidelines for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy. IDSA guidelines.Clin Infect Dis.2004;38:1651–1672.

- ,.Addressing postdischarge adverse events: a neglected area.Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf.2008;34:85–97.

- ,,,,,.Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care.JAMA.2007;297:831–841.

- ,,, et al.Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine.J Hosp Med.2009;4:364–370.

- .Hospitalist to home: outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy at an academic center.Clin Infect Dis.2010;51(suppl 2):S220–S223.

With dramatically increasing costs of healthcare, it has become increasingly necessary for healthcare providers to demonstrate value in the delivery of care. Porter and Teisberg have strongly advocated that healthcare reform efforts should focus on improving value rather than limiting cost, with value being defined as quality per unit cost.1 However, it has been pointed out that value means different things to different people.2 The biggest challenge in defining value stems mainly from the difficulty in defining quality, because it, too, means vastly different things to different people. Modern medicine is increasingly characterized by multidisciplinary care. With limited or shrinking resources, it will become necessary for individual specialists to describe and articulate, in quantitative terms, their specific contributions to the overall outcome of individual patients.

Previous publications have provided broad descriptions of the value provided by infectious disease (ID) specialists in the domains of sepsis, infection control, outpatient antibiotic therapy, antimicrobial stewardship, and directive care and teaching.3, 4 Studies have also shown the value of ID physicians in specific disease conditions. ID consultation is associated with lower mortality5, 6 and lower relapse rates7 in hospitalized patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. In another study evaluating the impact of ID consultants, patients seen by ID consultants had longer lengths of hospital stay, longer intensive care unit lengths of stay, and higher antibiotic costs than matched controls not seen by ID consultants.8 It can be argued that a major limitation of the study was that controls were not matched for the ID diagnosis, nor for the causative microorganisms, but it is clear that ID physicians are challenged to demonstrate their contribution to the care of patients.

A unique activity of ID physicians is the management of community‐based parenteral anti‐infective therapy (CoPAT). At Baystate Medical Center, a policy of mandatory ID consultation was instituted for patients leaving hospital on parenteral antibiotics. A study was conducted on the impact of predischarge ID consultation for 44 patients who were not already being followed by the ID service. The study documented change from intravenous (IV) to oral formulation, change of antibiotic choice, and change of dose/duration of treatment in a substantial proportion of patients.9 These are significant changes, but ID consultation contributes more than the themes explored in the study.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ID consultation when consulted for CoPAT, an activity specific to ID practice, in a different institution, and using an expanded definition of medical contribution.

METHODS

The Cleveland Clinic's Department of Infectious Disease has 24 staff physicians and 11 inpatient ID consultative services. These include: 2 solid organ transplant services; a bone marrow transplant and oncologic service; 2 infective endocarditis/cardiac device infection services; an intensive care unit (ICU) service; a bone and joint infection service; a neuroinfection service; and 3 general ID consult services. Consultative services are provided 7 days a week. At the Cleveland Clinic, ID consultation is required prior to discharge on parenteral antibiotic therapy.10, 11 ID consultation for CoPAT usually occurs when the primary service deems the patient is close to being discharged from hospital. This circumstance allows for assessing the specific contribution of ID physicians beyond that of the primary service and other consulting services.

Case Ascertainment

The study was approved by the institutional review board. In February 2010, an electronic form for requesting ID consultations had been introduced into the computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system at the Cleveland Clinic. One of the required questions on the form was whether the consultation was regarding CoPAT, with options of Yes, No, or Not sure. These electronic ID consultation requests were screened to identify consultation requests for this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All adult ID consultations between February 11, 2010 and May 15, 2010 for which the CoPAT consult? field was marked Yes were included in the study. All other consultations, including not sure for CoPAT, were excluded.

Definitions

The first ID consultation during a hospitalization was considered an initial consultation. ID consultations for patients whom an ID service had previously seen during the same hospitalization were deemed reconsultations. Value provided was defined as contribution of the ID consultation team in the following domains: 1) optimization of antimicrobial therapy, 2) significant change in patient assessment, 3) additional medical care contribution. Specific contributions included in each domain are outlined in Table 1.

|

| Domain 1: Optimization of antibiotic therapy |

| Alteration of an antibiotic (change of antibiotic or route of administration) |

| Defining duration of therapy |

| Identification of psychosocial factors (eg, injection drug use) that influence treatment |

| Domain 2: Significant change in patient assessment |

| Diagnosis of an infectious process |

| Better appreciation of extent of disease |

| Refutation of a false infectious disease diagnosis |

| Recognition of a noninfectious process needing urgent attention |

| Identification of a positive culture as contaminant/colonization |

| Recognition of a need for additional testing (testing needed to arrive at a diagnosis or clarify a treatment plan before a patient could be safely discharged from hospital) |

| Recognition of need for surgery/emnvasive intervention |

| Refutation of antibiotic allergy by history or allergy testing |

| Domain 3: Additional medical care contribution |

| Administration of vaccines |

| Identification of an unrecognized medical problem that needed to be addressed after discharge from hospital |

| Provision of effective transition of care (ensuring that the same ID physician who saw the patient in hospital followed the patient after discharge from hospital) |

Data Collected

For each ID consultation episode, clinicians' notes were reviewed from the day of the ID consultation to the day the patient was discharged from hospital or the day the ID service signed off, whichever happened sooner. Results of recommended tests were followed up to determine if results led to a change in patient assessment. Data elements collected for each consultation episode included patient age, gender, race, date of hospitalization, date of discharge, date of ID consultation or reconsultation, primary service, and documentation of ID service contributions. Data were collected and entered in a Microsoft Access relational database. To minimize bias, the data collection was performed by physicians who had not participated in the care of the patient.

Analysis

The proportion of ID consultations in which the ID team contributed in the defined domains were enumerated, and described for the group overall and also separately for initial consultations and reconsultations.

RESULTS

In the time period studied, there were 1326 CPOE requests for ID consultation. The response to the question, CoPAT consult? was Yes for 304, No for 507, and Not sure for 515 requests. Of the 304 consultation requests marked Yes, 41 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: no ID consultation note (21), wrong service consulted (8), consultation request placed while the ID service was already following the patient (7), and duplicate consultation request (5). The remaining 263 consultation requests corresponded to 1 or more CoPAT consultation requests for 249 patients (across different hospitalizations). Of the 263 consultation requests, 172 were initial consultations, while the remaining 91 were reconsultations (patients not actively being followed by the ID service, but previously seen during the same hospitalization).

Consultation characteristics are outlined in Table 2. The most common group of infections for which CoPAT was sought was bone and joint infections, accounting for over 20% of the consultation requests. CoPAT consultations were requested a median of 4 days after hospitalization. Patients were discharged from hospital a median of 3 days after they were seen by the ID service. ID consultation did not delay discharge. The ID service usually saw the patient the same day, and followed the patient in hospital for a median of 1 day. There was no difference in hospital days after consult for patients who did not need antibiotics versus those who did.

| Characteristic | Initial Consultation [172] n (%)* | Reconsultation [91] n (%)* | Overall [263] n (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Patient age in years, mean (SD) | 58 (14) | 62 (13) | 59 (14) |

| Male gender | 98 (60) | 91 (56) | 149 (57) |

| Caucasian race | 126 (73) | 74 (81) | 200 (76) |

| Services requesting consults (5 most common overall) | |||

| Medicine | 41 (17) | 14 (15) | 55 (21) |

| Orthopedics | 34 (14) | 0 (0) | 34 (13) |

| Hematology/Oncology | 16 (7) | 10 (11) | 26 (10) |

| Cardiology | 9 (4) | 15 (16) | 24 (9) |

| Gastroenterology | 14 (6) | 5 (5) | 19 (7) |

| Consult diagnosis (5 most common overall) | |||

| Bone and joint infection | 45 (26) | 9 (10) | 54 (21) |

| Skin or soft tissue infection or rash | 21 (12) | 8 (9) | 29 (11) |

| Endocarditis or cardiac device infection | 7 (4) | 15 (16) | 22 (8) |

| IV catheter or other endovascular infection | 9 (5) | 8 (9) | 17 (6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 (7) | 5 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Days from admission to ID consult, median (IQR) | 4 (1‐11) | 7 (2‐19) | 4 (1‐14) |

| Days to respond to consult request, median (IQR) | 0 (0‐1) | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐0) |

| Days from ID consult to discharge, median (IQR) | 3 (2‐7) | 2 (1‐4.5) | 3 (1‐6) |

ID consultation provided value in at least 1 domain in 260 of the 263 consultations. This included optimization of antimicrobial treatment in 84%, significant alteration of patient assessment in 52%, and additional medical care contribution in 71% of consultations. Substantial contributions were made in all domains in both initial consultations and in reconsultations. Specific ID contributions within each of the domains are shown in Figure 1. There was wide overlap of contributions across the 3 domains for individual consultations (Figure 2), with contributions in all domains occurring in 34% of consultations. CoPAT was deemed not to be necessary in 27% of consultations. Among patients who did not require CoPAT, 60% received oral antibiotics and 40% were deemed not to need any antibiotics at hospital discharge. Among the patients discharged on CoPAT, a follow‐up appointment with a Cleveland Clinic ID physician familiar with the patient was set up 86% of the time; the rest either followed up with another physician or it was deemed that a scheduled follow‐up ID visit was not necessary.0

DISCUSSION

Physicians practicing in the specialty of infectious diseases face challenges and opportunities, as they adapt to changing demands within hospital practice in regard to reimbursement in an Accountable Care environment. Other challenges include emerging infections, antimicrobial resistance, need for antimicrobial stewardship, and increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients.12 From a health systems perspective, the overall value of care provided by the entire organization, and overall outcomes, are ultimately what matter. However, healthcare administrators need an appreciation of contributions of individual providers and specialties to fairly allocate resources and compensation for care provided. Articulating unique contributions is particularly challenging for individuals or services that provide purely cognitive input. Shrinking healthcare resources makes it critically important for cognitive specialists to be able to define their unique role in the care of patients with complex problems.

Our study found that a major contribution of ID consultation for CoPAT is that the process identifies a large number of patients who do not need CoPAT, thus effecting a powerful antimicrobial stewardship function. In our study, CoPAT was deemed unnecessary 27% of the time. The Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy emphasize the importance of careful evaluation of patients considered for parenteral antibiotics outside the hospital setting.13 The focus on careful selection of appropriate patients for CoPAT has been a cornerstone of the Cleveland Clinic model of care. Nearly 30 years ago, we found that outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy was unnecessary or not feasible in 40% of the patients referred for evaluation.10 If we adjust the numbers with the assumption that reimbursement issues present at that time are now less of an issue, the proportion of patients who were referred for CoPAT but not discharged on it was 29%, a figure remarkably similar to that found in the current study.

Another major contribution of ID consultation is the provision of effective transition of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. Frequent occurrence of postdischarge adverse events has been recognized as a problem in clinical practice.14 Primary care physicians are rarely involved in discussions about hospital discharge.15 A consensus conference including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, and Society of General Internal Medicine, convened in July 2007 to address quality gaps in transitions of care between inpatient and outpatient settings. It identified 5 principles for effective care transitions: accountability, communication, timeliness, patient and family involvement, and respect for the hub of coordination of care.16 Recognizing gaps in care transition, hospitalists in a hospital‐based infusion program developed a model of care that successfully bridged the hospital‐to‐home care transition for patients who could return to hospital for daily antimicrobial infusions.17 In our system, ID physicians take ownership for directing parenteral antibiotic therapy for the episode of illness, specifying the physician, date, and time of follow‐up before the patient is discharged from hospital, thereby essentially satisfying the principles of effective care transitions identified. The purpose of the ID follow‐up is not to replace other follow‐up care for patients but to ensure safe transition of care while treating an episode of infection.

Attribution of identified contributions to the ID consultation could be done because our study was limited to CoPAT consultations. Such consultations typically occur when patients are deemed close to hospital discharge by the primary service. There should be little controversy about attribution of cognitive input in such consultations, because from the primary service's perspective, the patient is ready or almost ready to be discharged from hospital. It would be fair to state that most of the identified contributions in the study would not have occurred had it not been for the ID consultation.

We acknowledge that the study suffers from many limitations. The biggest limitation is that the contribution elements are defined by ID physicians and sought in the medical record by physicians from the same specialty. This arrangement certainly has potential for significant bias. To limit this bias, data collection was performed by physicians who had not participated in the care of the patient. In addition, we only could assess what was documented in the electronic health record. Our study found that alteration of antibiotic therapy was a substantial contribution, however, documentation of recommendation to change antibiotics in the medical record rarely specified exactly why the change was recommended. Reasons for antibiotic change recommendations included bug‐drug mismatch, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) considerations, pharmacokinetic considerations, adverse effects, convenience of dosing, drug interactions, and insurance coverage. However, it is not possible to quantify the specific contribution of each of these reasons, in a retrospective study, without making assumptions about why specific ID physicians made specific antibiotic change recommendations. There may have been more contributions that might not have been apparent on a retrospective chart review. The lack of a control group also lessens the impact of our findings. We could not have a control group, because no patient is discharged from the Cleveland Clinic on CoPAT without having been seen by an ID physician. Mandatory ID consultation for CoPAT has previously been shown to reduce costs,9 however, our study was not designed to evaluate cost.

The perceived value of ID consultation in our institution can be appreciated when one considers the longstanding institutional policy of requiring ID consultation for CoPAT.10, 11 The perpetuation of this tradition in the hospital is testament to the presumption that mandatory ID consultation is seen to be of value by the institution.

In summary, ID consultation in our institution contributes to the care of inpatients being considered for CoPAT by substantially reducing unnecessary parenteral antibiotic use, optimizing antibiotic therapy, recognizing need for additional testing before discharge from hospital, and by providing effective transition of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting.

With dramatically increasing costs of healthcare, it has become increasingly necessary for healthcare providers to demonstrate value in the delivery of care. Porter and Teisberg have strongly advocated that healthcare reform efforts should focus on improving value rather than limiting cost, with value being defined as quality per unit cost.1 However, it has been pointed out that value means different things to different people.2 The biggest challenge in defining value stems mainly from the difficulty in defining quality, because it, too, means vastly different things to different people. Modern medicine is increasingly characterized by multidisciplinary care. With limited or shrinking resources, it will become necessary for individual specialists to describe and articulate, in quantitative terms, their specific contributions to the overall outcome of individual patients.

Previous publications have provided broad descriptions of the value provided by infectious disease (ID) specialists in the domains of sepsis, infection control, outpatient antibiotic therapy, antimicrobial stewardship, and directive care and teaching.3, 4 Studies have also shown the value of ID physicians in specific disease conditions. ID consultation is associated with lower mortality5, 6 and lower relapse rates7 in hospitalized patients with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. In another study evaluating the impact of ID consultants, patients seen by ID consultants had longer lengths of hospital stay, longer intensive care unit lengths of stay, and higher antibiotic costs than matched controls not seen by ID consultants.8 It can be argued that a major limitation of the study was that controls were not matched for the ID diagnosis, nor for the causative microorganisms, but it is clear that ID physicians are challenged to demonstrate their contribution to the care of patients.

A unique activity of ID physicians is the management of community‐based parenteral anti‐infective therapy (CoPAT). At Baystate Medical Center, a policy of mandatory ID consultation was instituted for patients leaving hospital on parenteral antibiotics. A study was conducted on the impact of predischarge ID consultation for 44 patients who were not already being followed by the ID service. The study documented change from intravenous (IV) to oral formulation, change of antibiotic choice, and change of dose/duration of treatment in a substantial proportion of patients.9 These are significant changes, but ID consultation contributes more than the themes explored in the study.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ID consultation when consulted for CoPAT, an activity specific to ID practice, in a different institution, and using an expanded definition of medical contribution.

METHODS

The Cleveland Clinic's Department of Infectious Disease has 24 staff physicians and 11 inpatient ID consultative services. These include: 2 solid organ transplant services; a bone marrow transplant and oncologic service; 2 infective endocarditis/cardiac device infection services; an intensive care unit (ICU) service; a bone and joint infection service; a neuroinfection service; and 3 general ID consult services. Consultative services are provided 7 days a week. At the Cleveland Clinic, ID consultation is required prior to discharge on parenteral antibiotic therapy.10, 11 ID consultation for CoPAT usually occurs when the primary service deems the patient is close to being discharged from hospital. This circumstance allows for assessing the specific contribution of ID physicians beyond that of the primary service and other consulting services.

Case Ascertainment

The study was approved by the institutional review board. In February 2010, an electronic form for requesting ID consultations had been introduced into the computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system at the Cleveland Clinic. One of the required questions on the form was whether the consultation was regarding CoPAT, with options of Yes, No, or Not sure. These electronic ID consultation requests were screened to identify consultation requests for this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All adult ID consultations between February 11, 2010 and May 15, 2010 for which the CoPAT consult? field was marked Yes were included in the study. All other consultations, including not sure for CoPAT, were excluded.

Definitions

The first ID consultation during a hospitalization was considered an initial consultation. ID consultations for patients whom an ID service had previously seen during the same hospitalization were deemed reconsultations. Value provided was defined as contribution of the ID consultation team in the following domains: 1) optimization of antimicrobial therapy, 2) significant change in patient assessment, 3) additional medical care contribution. Specific contributions included in each domain are outlined in Table 1.

|

| Domain 1: Optimization of antibiotic therapy |

| Alteration of an antibiotic (change of antibiotic or route of administration) |

| Defining duration of therapy |

| Identification of psychosocial factors (eg, injection drug use) that influence treatment |

| Domain 2: Significant change in patient assessment |

| Diagnosis of an infectious process |

| Better appreciation of extent of disease |

| Refutation of a false infectious disease diagnosis |

| Recognition of a noninfectious process needing urgent attention |

| Identification of a positive culture as contaminant/colonization |

| Recognition of a need for additional testing (testing needed to arrive at a diagnosis or clarify a treatment plan before a patient could be safely discharged from hospital) |

| Recognition of need for surgery/emnvasive intervention |

| Refutation of antibiotic allergy by history or allergy testing |

| Domain 3: Additional medical care contribution |

| Administration of vaccines |

| Identification of an unrecognized medical problem that needed to be addressed after discharge from hospital |

| Provision of effective transition of care (ensuring that the same ID physician who saw the patient in hospital followed the patient after discharge from hospital) |

Data Collected

For each ID consultation episode, clinicians' notes were reviewed from the day of the ID consultation to the day the patient was discharged from hospital or the day the ID service signed off, whichever happened sooner. Results of recommended tests were followed up to determine if results led to a change in patient assessment. Data elements collected for each consultation episode included patient age, gender, race, date of hospitalization, date of discharge, date of ID consultation or reconsultation, primary service, and documentation of ID service contributions. Data were collected and entered in a Microsoft Access relational database. To minimize bias, the data collection was performed by physicians who had not participated in the care of the patient.

Analysis

The proportion of ID consultations in which the ID team contributed in the defined domains were enumerated, and described for the group overall and also separately for initial consultations and reconsultations.

RESULTS

In the time period studied, there were 1326 CPOE requests for ID consultation. The response to the question, CoPAT consult? was Yes for 304, No for 507, and Not sure for 515 requests. Of the 304 consultation requests marked Yes, 41 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: no ID consultation note (21), wrong service consulted (8), consultation request placed while the ID service was already following the patient (7), and duplicate consultation request (5). The remaining 263 consultation requests corresponded to 1 or more CoPAT consultation requests for 249 patients (across different hospitalizations). Of the 263 consultation requests, 172 were initial consultations, while the remaining 91 were reconsultations (patients not actively being followed by the ID service, but previously seen during the same hospitalization).

Consultation characteristics are outlined in Table 2. The most common group of infections for which CoPAT was sought was bone and joint infections, accounting for over 20% of the consultation requests. CoPAT consultations were requested a median of 4 days after hospitalization. Patients were discharged from hospital a median of 3 days after they were seen by the ID service. ID consultation did not delay discharge. The ID service usually saw the patient the same day, and followed the patient in hospital for a median of 1 day. There was no difference in hospital days after consult for patients who did not need antibiotics versus those who did.

| Characteristic | Initial Consultation [172] n (%)* | Reconsultation [91] n (%)* | Overall [263] n (%)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Patient age in years, mean (SD) | 58 (14) | 62 (13) | 59 (14) |

| Male gender | 98 (60) | 91 (56) | 149 (57) |

| Caucasian race | 126 (73) | 74 (81) | 200 (76) |

| Services requesting consults (5 most common overall) | |||

| Medicine | 41 (17) | 14 (15) | 55 (21) |

| Orthopedics | 34 (14) | 0 (0) | 34 (13) |

| Hematology/Oncology | 16 (7) | 10 (11) | 26 (10) |

| Cardiology | 9 (4) | 15 (16) | 24 (9) |

| Gastroenterology | 14 (6) | 5 (5) | 19 (7) |

| Consult diagnosis (5 most common overall) | |||

| Bone and joint infection | 45 (26) | 9 (10) | 54 (21) |

| Skin or soft tissue infection or rash | 21 (12) | 8 (9) | 29 (11) |

| Endocarditis or cardiac device infection | 7 (4) | 15 (16) | 22 (8) |

| IV catheter or other endovascular infection | 9 (5) | 8 (9) | 17 (6) |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 (7) | 5 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Days from admission to ID consult, median (IQR) | 4 (1‐11) | 7 (2‐19) | 4 (1‐14) |

| Days to respond to consult request, median (IQR) | 0 (0‐1) | 0 (0‐0) | 0 (0‐0) |

| Days from ID consult to discharge, median (IQR) | 3 (2‐7) | 2 (1‐4.5) | 3 (1‐6) |

ID consultation provided value in at least 1 domain in 260 of the 263 consultations. This included optimization of antimicrobial treatment in 84%, significant alteration of patient assessment in 52%, and additional medical care contribution in 71% of consultations. Substantial contributions were made in all domains in both initial consultations and in reconsultations. Specific ID contributions within each of the domains are shown in Figure 1. There was wide overlap of contributions across the 3 domains for individual consultations (Figure 2), with contributions in all domains occurring in 34% of consultations. CoPAT was deemed not to be necessary in 27% of consultations. Among patients who did not require CoPAT, 60% received oral antibiotics and 40% were deemed not to need any antibiotics at hospital discharge. Among the patients discharged on CoPAT, a follow‐up appointment with a Cleveland Clinic ID physician familiar with the patient was set up 86% of the time; the rest either followed up with another physician or it was deemed that a scheduled follow‐up ID visit was not necessary.0

DISCUSSION

Physicians practicing in the specialty of infectious diseases face challenges and opportunities, as they adapt to changing demands within hospital practice in regard to reimbursement in an Accountable Care environment. Other challenges include emerging infections, antimicrobial resistance, need for antimicrobial stewardship, and increasing numbers of immunocompromised patients.12 From a health systems perspective, the overall value of care provided by the entire organization, and overall outcomes, are ultimately what matter. However, healthcare administrators need an appreciation of contributions of individual providers and specialties to fairly allocate resources and compensation for care provided. Articulating unique contributions is particularly challenging for individuals or services that provide purely cognitive input. Shrinking healthcare resources makes it critically important for cognitive specialists to be able to define their unique role in the care of patients with complex problems.

Our study found that a major contribution of ID consultation for CoPAT is that the process identifies a large number of patients who do not need CoPAT, thus effecting a powerful antimicrobial stewardship function. In our study, CoPAT was deemed unnecessary 27% of the time. The Infectious Diseases Society of America practice guidelines on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy emphasize the importance of careful evaluation of patients considered for parenteral antibiotics outside the hospital setting.13 The focus on careful selection of appropriate patients for CoPAT has been a cornerstone of the Cleveland Clinic model of care. Nearly 30 years ago, we found that outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy was unnecessary or not feasible in 40% of the patients referred for evaluation.10 If we adjust the numbers with the assumption that reimbursement issues present at that time are now less of an issue, the proportion of patients who were referred for CoPAT but not discharged on it was 29%, a figure remarkably similar to that found in the current study.

Another major contribution of ID consultation is the provision of effective transition of care from the inpatient to the outpatient setting. Frequent occurrence of postdischarge adverse events has been recognized as a problem in clinical practice.14 Primary care physicians are rarely involved in discussions about hospital discharge.15 A consensus conference including the American College of Physicians, Society of Hospital Medicine, and Society of General Internal Medicine, convened in July 2007 to address quality gaps in transitions of care between inpatient and outpatient settings. It identified 5 principles for effective care transitions: accountability, communication, timeliness, patient and family involvement, and respect for the hub of coordination of care.16 Recognizing gaps in care transition, hospitalists in a hospital‐based infusion program developed a model of care that successfully bridged the hospital‐to‐home care transition for patients who could return to hospital for daily antimicrobial infusions.17 In our system, ID physicians take ownership for directing parenteral antibiotic therapy for the episode of illness, specifying the physician, date, and time of follow‐up before the patient is discharged from hospital, thereby essentially satisfying the principles of effective care transitions identified. The purpose of the ID follow‐up is not to replace other follow‐up care for patients but to ensure safe transition of care while treating an episode of infection.

Attribution of identified contributions to the ID consultation could be done because our study was limited to CoPAT consultations. Such consultations typically occur when patients are deemed close to hospital discharge by the primary service. There should be little controversy about attribution of cognitive input in such consultations, because from the primary service's perspective, the patient is ready or almost ready to be discharged from hospital. It would be fair to state that most of the identified contributions in the study would not have occurred had it not been for the ID consultation.