User login

Visceral angioedema due to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy

A 57-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department with severe, dull abdominal pain associated with nonbilious vomiting and nausea. She had diabetes mellitus and hypertension, for which she had been taking metformin (Glucophage) 500 mg twice a day and lisinopril (available as Prinivil and Zestril) 20 mg daily for the last 4 years.

Multiple admissions in the past 4 years

The patient started taking lisinopril 10 mg daily in 2005, and she presented to her medical provider 2 weeks later with abdominal discomfort. Colonoscopy was performed, which revealed a benign polyp. She continued taking her medications, including lisinopril.

She continued to occasionally have abdominal pain of variable severity, but it was tolerable until 6 months later, when she presented to the emergency department with severe recurrent abdominal pain.

In view of the clinical picture, her physicians decided to treat her for small bowel obstruction, and an exploratory laparotomy was performed. The surgeons noted that she had moderate ascites, adhesions on the omentum, and a thickened high loop of the small bowel that was unequivocally viable and hyperemic, with thickening of the mesentery. Ascitic fluid was evacuated, adhesions were lysed, and the abdomen was closed. She was discharged with the same medications, including lisinopril; the dose was subsequently increased for better control of her hypertension.

The woman was admitted three more times within the same year for the same symptoms and underwent multiple workups for pancreatitis, gastritis, small-bowel obstruction, and other common gastrointestinal diseases.

Present admission

On review of systems, she denied any dry cough, weight loss or gain, food allergies, new medications, or hematochezia.

On physical examination, she had hypoactive bowel sounds and diffuse tenderness with guarding around the epigastric area.

Laboratory tests did not reveal any abnormalities; in particular, her C1 esterase concentration was normal. Stool studies were negative for infectious diseases.

Plain radiography of the abdomen showed a nonobstructive bowel-gas pattern.

She was diagnosed with gastrointestinal angioedema secondary to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Her lisinopril was discontinued, and the symptoms resolved completely in 24 hours. On follow-up 8 weeks and 16 months later, her symptoms had not returned.

A RARE COMPLICATION OF ACE-INHIBITOR THERAPY

Angioedema occurs in 0.1% to 0.7% of patients taking ACE inhibitors, and it can affect about 1 of 2,500 patients during the first week of exposure.1–3 It usually manifests as swelling of the face, tongue, and lips, and in rare cases, the gastrointestinal wall. Thus, visceral angioedema is a rare complication of ACE-inhibitor therapy.

Because angioedema is less obvious when it involves abdominal organs, it presents a diagnostic challenge. It is placed lower in the differential diagnosis, as other, more common, and occasionally more high-risk medical conditions are generally considered first. Most of the time, the diagnosis is missed. Some physicians may not be aware of this problem, since only a few case reports have been published. Nevertheless, this potential complication needs to be considered when any patient receiving ACE inhibitors for treatment of hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or diabetic nephropathy presents with diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, or edema of the upper airways.4–8

If a high level of suspicion is applied along with good clinical judgment, then hospitalizations, unnecessary procedures, patient discomfort, and unnecessary health care costs can be prevented.

A MEDLINE SEARCH

To investigate the characteristics associated with this unusual presentation, including the time of symptom onset, the types of symptoms, and the diagnostic studies performed on the patients with visceral angioedema, we performed a MEDLINE search to identify case reports and case series published in English from 1980 to 2010 on the topic of abdominal or visceral angioedema. The search terms used were “visceral,” “intestinal angioedema,” “ACE-inhibitor side effects,” and the names of various ACE inhibitors.

Pertinent articles were identified, and clinical characteristics were collected, including demographics, onset of symptoms, the drug’s name, and others. In our summary below, data are presented as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

SUMMARY OF REPORTED CASES

Our search revealed 27 reported cases of visceral angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors (a table summarizing our findings is available).9–34 The drug most often involved was lisinopril (11 cases), followed by enalapril (Vasotec) (8 cases).

Twenty-three (82%) of the cases were in women. The mean age of the patients was 49.5 ± 12.2 years (range 29–77 years); the mean age was 46.7 ± 11.7 years in women and 57 ± 13 years in men. Unfortunately, the race and ethnicity of the patients was documented in only some cases.

In 15 (54%) of the cases, the patient presented to a physician or emergency department within 72 hours (41.1 ± 17.4) of starting therapy, and in 8 cases the patient presented between 2 weeks and 18 months.

In 10 cases (including the case we are reporting here), the patients were kept on ACE inhibitors from 2 to 9 years after the initial presentation, as the diagnosis was missed.9,12,14,18,20,31,32 In 2 cases, the dose of the ACE inhibitor had been increased after the patient presented with the abdominal pain.

All of the patients were hospitalized for further diagnostic workup.

As for the presenting symptoms, all the patients had abdominal pain, 24 (86%) had emesis, 14 (50%) had diarrhea, and 20 (71%) had ascites. Laboratory results were mostly nonspecific. Twelve (44%) of the patients had leukocytosis. The C1 esterase inhibitor concentration was measured in 18 patients, and the results were normal in all of them.

Twenty-four (86%) of the patients underwent abdominal and pelvic CT or ultrasonography as part of the initial diagnostic evaluation, and intestinal wall-thickening was found in 21 (87.5%) of them.

Either surgery or gastrointestinal biopsy was performed in 16 (57%) of the patients; the surgical procedures included 2 cholecystectomies and 1 bone marrow biopsy. Only 1 case was diagnosed on the basis of clinical suspicion and abdominal radiographs alone.

The combination of intestinal and stomach angioedema was found in only 2 cases.

Two patients were kept on an ACE inhibitor in spite of symptoms and intestinal wall edema that showed a migratory pattern on imaging after chronic exposure.

The thickening involved the jejunum in 14 patients (50%), the ileum in 8 (29%), the duodenum in 5 (18%), the stomach in 2, and the sigmoid colon in 1.

In 12 cases (43%), visceral angioedema and its symptoms resolved within 48 hours of stopping the ACE inhibitor.

A DIAGNOSIS TO KEEP IN MIND

As we have seen, the diagnosis of visceral angioedema needs to be kept in mind when a patient—especially a middle-aged woman—taking an ACE inhibitor presents with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, leukocytosis, ascites, and wall-thickening of the small bowel on imaging studies.9,35,36

The diagnosis is hard to establish, and in the interim the patient may undergo invasive and unnecessary procedures, which can be avoided by a heightened awareness of this complication. In all of the reported cases, the patients required hospitalization because of the severity of symptoms and attempts to exclude other possible diseases.36

POSSIBLY DUE TO BRADYKININ

Several theories have been proposed to explain how visceral angioedema is induced by ACE inhibitors. The possible mechanisms that have been described include the following:

- The accumulation of bradykinin and substance P secondary to the effect of the ACE inhibitor, which may lead to the inflammatory response, therefore increasing permeability of the vascular compartment

- Deficiency of complement and the enzymes carboxypeptidase N and alpha-1 antitrypsin

- An antibody-antigen reaction37

- Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone (suggested by the greater number of women represented38)

- Contrast media used for imaging39

- Genetic predisposition

- Inflammation due to acute-phase proteins

- C1-inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction (however, the levels of C1/C4 and the C1-esterase inhibitor functional activity usually are normal2,10,40).

Many other theories are being explored.11,12,38,41–53

The most plausible mechanism is an increase in the levels of bradykinin and its metabolites.45 The absence of ACE can lead to breakdown of bradykinin to des-Arg bradykinin via the minor pathway, which can lead to more pronounced vasodilation and vascular permeability.54,55 During an acute attack of angioedema secondary to ACE inhibition, the bradykinin concentration can increase to more than 10 times the normal level.56

Moreover, C-reactive protein levels were higher (mean 4.42 mg/dL ± 0.15 mg/dL) in patients with ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema than in those with other causes of angioedema (P < .0001).52 The patients taking ACE inhibitors without any previous angioedema had normal C-reactive protein levels (0.39 mg/dL ± 0.1 mg/dL).52

INCIDENCE RATES

In our review of the literature, all of the patients were taking an ACE inhibitor, and some were taking both an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB).

Initially, the incidence rate of angioedema was thought to be 0.1% to 0.2%, but recently the Omapatrilat Cardiovascular Treatment Assessment vs Enalapril (OCTAVE) trial had more than 12,000 patients on enalapril and reported the incidence of angioedema to be 0.68%,57 with a higher risk in women than in men (0.84% vs 0.54%)58 and a relative risk of 3.03 for blacks compared with whites.59

Even though ARBs seem to be safer, angioedema can recur in up to one-third of patients who switch from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB.60–63

Moreover, one study in the United States found that the frequency of hospital admission of patients with angioedema increased from 8,839 per year in 1998 to 11,925 in 2005, and the cost was estimated to be close to $123 million in 2005.64

Interestingly, when angioedema involved the face, it developed within the first week in 60% of cases,65 whereas when visceral angioedema developed, it did so within the first week in 59% of cases. Therefore, the timing of the onset is similar regardless of the body area involved.

Smokers who developed ACE-inhibitor-induced cough had a higher risk of ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema in a retrospective cohort study by Morimoto,66 but no relationship to the area of involvement was made.

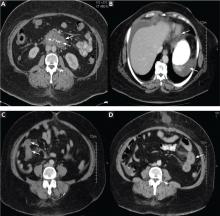

ON IMAGING, A THICKENED BOWEL WALL

Computed tomography can reveal bowel edema and ascites more reliably than plain radiography or barium studies. Edema thickens the bowel wall, with increased contrast enhancement that makes mesenteric vessels show up on the study. In some instances edema is so significant that edematous submucosa can be differentiated from the serosa due to impressive thickening of the mucosal wall.15,16 Oral contrast can be seen in the middle of the lumen, giving it a target-sign appearance. Edema of the small bowel and ascites can lead to fluid sequestration in the abdomen, resulting in a presentation with shock.67

Magnetic resonance imaging can be even more useful in identifying gastrointestinal angioedema, but it would not be cost-effective, and based on our study, CT and ultrasonography of the abdomen were diagnostic in most cases.

AVOIDING UNNECESSARY TESTING

Hemodynamic instability and abdominal pain usually trigger a surgical consult and a more extensive workup, but with a good clinical approach, unnecessary testing and invasive diagnostic procedures can be avoided under the right circumstances.

Numerous surgical procedures have been reported in patients presenting with visceral angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.67 Although a thorough history and physical examination can give us a clue in the diagnosis of drug-induced gastrointestinal angioedema, CT is extremely helpful, as it shows dilated loops, thickened mucosal folds, perihepatic fluid, ascites, mesenteric edema, and a “doughnut” or “stacked coin” appearance.17,68

So far, there have been only two reports of angioedema of the stomach (the case reported by Shahzad et al10 and the current report). Angioedema can affect any visceral organ, but we usually see involvement of the jejunum followed by the ileum and duodenum.40

FINDINGS ON ENDOSCOPY

Usually, endoscopic examination of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract does not reveal any specific pathology, but endoscopy and biopsy can rule out other causes of abdominal pain, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, infection, malignancy, granuloma, and vasculitis. Also, hereditary or acquired C1-esterase deficiency and other autoimmune disorders should be considered in the workup.18,69 In the reported cases, endoscopy revealed petechial bleeding with generalized edema.19

Biopsy often demonstrates an expanded edematous submucosal layer with inflammatory cell infiltration and protrusion of the proper muscular layer into the submucosal layer.15 A proper muscular layer and an edematous submucosal layer can produce edema so severe as to obstruct the intestine.15

Ultrasonography or CT provides essential information as to location, structure, and size, and it rules out other diagnoses. Therefore, consideration should be given to noninvasive imaging studies and laboratory testing (C1-esterase inhibitor, complement, antinuclear antibody, complete metabolic panel, complete blood cell count) before resorting to endoscopy or exploratory laparotomy.20,70 In three case reports,29,30,32 abdominal ultrasonography did not show any thickening of the small-bowel wall. Several cases have been diagnosed with the help of endoscopy.

Symptoms usually resolve when the ACE inhibitor is stopped

There is no standard treatment for ACE-inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. In most patients, stopping the drug, giving nothing by mouth, and giving intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration are sufficient. Symptoms usually resolve within 48 hours.

In several case reports, fresh-frozen plasma was used to increase the levels of kininase II, which can degrade high levels of bradykinin.51,71,72 However, no randomized controlled trial of fresh-frozen plasma for ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema has been published.

Drugs for hereditary angioedema—eg, recombinant C1-INH, the kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide (Kalbitor), and the BKR-2-antagonist icatibant (Firazyr)73—have not been prospectively studied in gastrointestinal angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors. Icatibant has been shown to be effective in the treatment of hereditary angioedema and could be promising in treating angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.8 Rosenberg et al21 described a patient who was on prednisone when she developed intestinal angioedema, thus calling into question the efficacy of steroids in the treatment of visceral angioedema.

RAISING AWARENESS

More than 40 million patients are currently taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs.9 Therefore, we suggest that patients with a known history of angioedema in response to these drugs should wear an identification bracelet to increase awareness and to prevent recurrence of angioedema.

- Brown NJ, Snowden M, Griffin MR. Recurrent angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated angioedema. JAMA 1997; 278:232–233.

- Israili ZH, Hall WD. Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. A review of the literature and pathophysiology. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:234–242.

- Messerli FH, Nussberger J. Vasopeptidase inhibition and angiooedema. Lancet 2000; 356:608–609.

- Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2007–2018.

- Jessup M. The less familiar face of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:224–226.

- Chobanian AV. Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:789–796.

- Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2005; 366:2026–2033.

- Weber MA, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema: estimating the risk. Hypertension 2008; 51:1465–1467.

- Oudit G, Girgrah N, Allard J. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema of the intestine: Case report, incidence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Can J Gastroenterol 2001; 15:827–832.

- Shahzad G, Korsten MA, Blatt C, Motwani P. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-associated angioedema of the stomach and small intestine: a case report. Mt Sinai J Med 2006; 73:1123–1125.

- Chase MP, Fiarman GS, Scholz FJ, MacDermott RP. Angioedema of the small bowel due to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000; 31:254–257.

- Mullins RJ, Shanahan TM, Dobson RT. Visceral angioedema related to treatment with an ACE inhibitor. Med J Aust 1996; 165:319–321.

- Schmidt TD, McGrath KM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema of the intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2002; 324:106–108.

- Smoger SH, Sayed MA. Simultaneous mucosal and small bowel angioedema due to captopril. South Med J 1998; 91:1060–1063.

- Tojo A, Onozato ML, Fujita T. Repeated subileus due to angioedema during renin-angiotensin system blockade. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:36–38.

- De Backer AI, De Schepper AM, Vandevenne JE, Schoeters P, Michielsen P, Stevens WJ. CT of angioedema of the small bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176:649–652.

- Marmery H, Mirvis SE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. Clin Radiol 2006; 61:979–982.

- Orr KK, Myers JR. Intermittent visceral edema induced by long-term enalapril administration. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38:825–827.

- Spahn TW, Grosse-Thie W, Mueller MK. Endoscopic visualization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema as a cause of relapsing abdominal pain using double-balloon enteroscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53:1257–1260.

- Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Landis ME, Heppell JP. Isolated visceral angioedema: an underdiagnosed complication of ACE inhibitors? Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:1201–1204.

- Rosenberg EI, Mishra G, Abdelmalek MF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced isolated visceral angioedema in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation 2003; 75:730–732.

- Salloum H, Locher C, Chenard A, et al. [Small bowel angioedema due to perindopril]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005; 29:1180–1181.

- Arakawa M, Murata Y, Rikimaru Y, Sasaki Y. Drug-induced isolated visceral angioneurotic edema. Intern Med 2005; 44:975–978.

- Abdelmalek MF, Douglas DD. Lisinopril-induced isolated visceral angioedema: review of ACE-inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42:847–850.

- Gregory KW, Davis RC. Images in clinical medicine. Angioedema of the intestine. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1641.

- Farraye FA, Peppercorn MA, Steer ML, Joffe N, Rees M. Acute small-bowel mucosal edema following enalapril use. JAMA 1988; 259:3131.

- Jacobs RL, Hoberman LJ, Goldstein HM. Angioedema of the small bowel caused by an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89:127–128.

- Herman L, Jocums SB, Coleman MD. A 29-year-old woman with crampy abdominal pain. Tenn Med 1999; 92:272–273.

- Guy C, Cathébras P, Rousset H. Suspected angioedema of abdominal viscera. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121:900.

- Dupasquier E. [A rare clinical form of angioneurotic edema caused by enalapril: acute abdomen]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1994; 87:1371–1374.

- Jardine DL, Anderson JC, McClintock AD. Delayed diagnosis of recurrent visceral angio-oedema secondary to ACE inhibitor therapy. Aust N Z J Med 1999; 29:377–378.

- Matsumura M, Haruki K, Kajinami K, Takada T. Angioedema likely related to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Intern Med 1993; 32:424–426.

- Khan MU, Baig MA, Javed RA, et al. Benazepril induced isolated visceral angioedema: a rare and under diagnosed adverse effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Int J Cardiol 2007; 118:e68–e69.

- Adhikari SP, Schneider JI. An unusual cause of abdominal pain and hypotension: angioedema of the bowel. J Emerg Med 2009; 36:23–25.

- Gibbs CR, Lip GY, Beevers DG. Angioedema due to ACE inhibitors: increased risk in patients of African origin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48:861–865.

- Johnsen SP, Jacobsen J, Monster TB, Friis S, McLaughlin JK, Sørensen HT. Risk of first-time hospitalization for angioedema among users of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists. Am J Med 2005; 118:1428–1329.

- Bi CK, Soltani K, Sloan JB, Weber RR, Elliott WJ, Murphy MB. Tissue-specific autoantibodies induced by captopril. Clin Res 1987; 35:922A.

- Bork K, Dewald G. Hereditary angioedema type III, angioedema associated with angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and female sex. Am J Med 2004; 116:644–645.

- Witten DM, Hirsch FD, Hartman GW. Acute reactions to urographic contrast medium: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to history of hypersensitivity states. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 119:832–840.

- Eck SL, Morse JH, Janssen DA, Emerson SG, Markovitz DM. Angioedema presenting as chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:436–439.

- Coleman JW, Yeung JH, Roberts DH, Breckenridge AM, Park BK. Drug-specific antibodies in patients receiving captopril. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 22:161–165.

- Kallenberg CG. Autoantibodies during captopril treatment. Arthritis Rheum 1985; 28:597–598.

- Inman WH, Rawson NS, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Speirs CJ. Postmarketing surveillance of enalapril. I: Results of prescription-event monitoring. BMJ 1988; 297:826–829.

- Lefebvre J, Murphey LJ, Hartert TV, Jiao Shan R, Simmons WH, Brown NJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in patients with ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema. Hypertension 2002; 39:460–464.

- Molinaro G, Cugno M, Perez M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema is characterized by a slower degradation of des-arginine(9)-bradykinin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:232–237.

- Adam A, Cugno M, Molinaro G, Perez M, Lepage Y, Agostoni A. Aminopeptidase P in individuals with a history of angiooedema on ACE inhibitors. Lancet 2002; 359:2088–2089.

- Binkley KE, Davis A. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic characterization of a novel estrogen-dependent inherited form of angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:546–550.

- Yeung JH, Coleman JW, Park BK. Drug-protein conjugates—IX. Immunogenicity of captopril-protein conjugates. Biochem Pharmacol 1985; 34:4005–4012.

- Abbosh J, Anderson JA, Levine AB, Kupin WL. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema more prevalent in transplant patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999; 82:473–476.

- Pichler WJ, Lehner R, Späth PJ. Recurrent angioedema associated with hypogonadism or anti-androgen therapy. Ann Allergy 1989; 63:301–305.

- Bass G, Honan D. Octaplas is not equivalent to fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of acute angioedema. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2007; 24:1062–1063.

- Bas M, Hoffmann TK, Bier H, Kojda G. Increased C-reactive protein in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59:233–238.

- Herman AG. Differences in structure of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors might predict differences in action. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:102C–108C.

- Cunnion KM, Lee JC, Frank MM. Capsule production and growth phase influence binding of complement to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immunol 2001; 69:6796–6803.

- Cunnion KM, Wagner E, Frank MM. Complement and kinins. In:Parlow TG, Stites DP, Imboden JB, editors. Medical Immunology. 10th ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books; 2001:186–188.

- Pellacani A, Brunner HR, Nussberger J. Plasma kinins increase after angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in human subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994; 87:567–574.

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute. FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Book for OMAPATRILAT Tablets NDA 21-188. www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/02/briefing/3877B2_01_BristolMeyersSquibb.pdf. Accessed 2/4/2011.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637–1642.

- Mahoney EJ, Devaiah AK. Angioedema and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: are demographics a risk? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 139:105–108.

- Warner KK, Visconti JA, Tschampel MM. Angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34:526–528.

- Kyrmizakis DE, Papadakis CE, Liolios AD, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:1416–1419.

- MacLean JA, Hannaway PJ. Angioedema and AT1 receptor blockers: proceed with caution. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:1488–1489,

- Abdi R, Dong VM, Lee CJ, Ntoso KA. Angiotensin II receptor blocker-associated angioedema: on the heels of ACE inhibitor angioedema. Pharmacotherapy 2002; 22:1173–1175.

- Lin RY, Shah SN. Increasing hospitalizations due to angioedema in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101:185–192.

- Slater EE, Merrill DD, Guess HA, et al. Clinical profile of angioedema associated with angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibition. JAMA 1988; 260:967–970.

- Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Fiskio JM, et al. An evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Eval Clin Pract 2004; 10:499–509.

- Cohen N, Sharon A, Golik A, Zaidenstein R, Modai D. Hereditary angioneurotic edema with severe hypovolemic shock. J Clin Gastroenterol 1993; 16:237–239.

- Ciaccia D, Brazer SR, Baker ME. Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency causing intestinal angioedema: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 161:1215–1216.

- Malcolm A, Prather CM. Intestinal angioedema mimicking Crohn’s disease. Med J Aust 1999; 171:418–420.

- Schmidt TD, McGrath KM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema of the intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2002; 324:106–108.

- Karim MY, Masood A. Fresh-frozen plasma as a treatment for life-threatening ACE-inhibitor angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109:370–371.

- Warrier MR, Copilevitz CA, Dykewicz MS, Slavin RG. Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of resistant angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004; 92:573–575.

- Bas M, Adams V, Suvorava T, Niehues T, Hoffmann TK, Kojda G. Nonallergic angioedema: role of bradykinin. Allergy 2007; 62:842–856.

- Agostoni A, Cicardi M, Cugno M, Zingale LC, Gioffré D, Nussberger J. Angioedema due to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Immunopharmacology 1999; 44:21–25.

A 57-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department with severe, dull abdominal pain associated with nonbilious vomiting and nausea. She had diabetes mellitus and hypertension, for which she had been taking metformin (Glucophage) 500 mg twice a day and lisinopril (available as Prinivil and Zestril) 20 mg daily for the last 4 years.

Multiple admissions in the past 4 years

The patient started taking lisinopril 10 mg daily in 2005, and she presented to her medical provider 2 weeks later with abdominal discomfort. Colonoscopy was performed, which revealed a benign polyp. She continued taking her medications, including lisinopril.

She continued to occasionally have abdominal pain of variable severity, but it was tolerable until 6 months later, when she presented to the emergency department with severe recurrent abdominal pain.

In view of the clinical picture, her physicians decided to treat her for small bowel obstruction, and an exploratory laparotomy was performed. The surgeons noted that she had moderate ascites, adhesions on the omentum, and a thickened high loop of the small bowel that was unequivocally viable and hyperemic, with thickening of the mesentery. Ascitic fluid was evacuated, adhesions were lysed, and the abdomen was closed. She was discharged with the same medications, including lisinopril; the dose was subsequently increased for better control of her hypertension.

The woman was admitted three more times within the same year for the same symptoms and underwent multiple workups for pancreatitis, gastritis, small-bowel obstruction, and other common gastrointestinal diseases.

Present admission

On review of systems, she denied any dry cough, weight loss or gain, food allergies, new medications, or hematochezia.

On physical examination, she had hypoactive bowel sounds and diffuse tenderness with guarding around the epigastric area.

Laboratory tests did not reveal any abnormalities; in particular, her C1 esterase concentration was normal. Stool studies were negative for infectious diseases.

Plain radiography of the abdomen showed a nonobstructive bowel-gas pattern.

She was diagnosed with gastrointestinal angioedema secondary to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Her lisinopril was discontinued, and the symptoms resolved completely in 24 hours. On follow-up 8 weeks and 16 months later, her symptoms had not returned.

A RARE COMPLICATION OF ACE-INHIBITOR THERAPY

Angioedema occurs in 0.1% to 0.7% of patients taking ACE inhibitors, and it can affect about 1 of 2,500 patients during the first week of exposure.1–3 It usually manifests as swelling of the face, tongue, and lips, and in rare cases, the gastrointestinal wall. Thus, visceral angioedema is a rare complication of ACE-inhibitor therapy.

Because angioedema is less obvious when it involves abdominal organs, it presents a diagnostic challenge. It is placed lower in the differential diagnosis, as other, more common, and occasionally more high-risk medical conditions are generally considered first. Most of the time, the diagnosis is missed. Some physicians may not be aware of this problem, since only a few case reports have been published. Nevertheless, this potential complication needs to be considered when any patient receiving ACE inhibitors for treatment of hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or diabetic nephropathy presents with diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, or edema of the upper airways.4–8

If a high level of suspicion is applied along with good clinical judgment, then hospitalizations, unnecessary procedures, patient discomfort, and unnecessary health care costs can be prevented.

A MEDLINE SEARCH

To investigate the characteristics associated with this unusual presentation, including the time of symptom onset, the types of symptoms, and the diagnostic studies performed on the patients with visceral angioedema, we performed a MEDLINE search to identify case reports and case series published in English from 1980 to 2010 on the topic of abdominal or visceral angioedema. The search terms used were “visceral,” “intestinal angioedema,” “ACE-inhibitor side effects,” and the names of various ACE inhibitors.

Pertinent articles were identified, and clinical characteristics were collected, including demographics, onset of symptoms, the drug’s name, and others. In our summary below, data are presented as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

SUMMARY OF REPORTED CASES

Our search revealed 27 reported cases of visceral angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors (a table summarizing our findings is available).9–34 The drug most often involved was lisinopril (11 cases), followed by enalapril (Vasotec) (8 cases).

Twenty-three (82%) of the cases were in women. The mean age of the patients was 49.5 ± 12.2 years (range 29–77 years); the mean age was 46.7 ± 11.7 years in women and 57 ± 13 years in men. Unfortunately, the race and ethnicity of the patients was documented in only some cases.

In 15 (54%) of the cases, the patient presented to a physician or emergency department within 72 hours (41.1 ± 17.4) of starting therapy, and in 8 cases the patient presented between 2 weeks and 18 months.

In 10 cases (including the case we are reporting here), the patients were kept on ACE inhibitors from 2 to 9 years after the initial presentation, as the diagnosis was missed.9,12,14,18,20,31,32 In 2 cases, the dose of the ACE inhibitor had been increased after the patient presented with the abdominal pain.

All of the patients were hospitalized for further diagnostic workup.

As for the presenting symptoms, all the patients had abdominal pain, 24 (86%) had emesis, 14 (50%) had diarrhea, and 20 (71%) had ascites. Laboratory results were mostly nonspecific. Twelve (44%) of the patients had leukocytosis. The C1 esterase inhibitor concentration was measured in 18 patients, and the results were normal in all of them.

Twenty-four (86%) of the patients underwent abdominal and pelvic CT or ultrasonography as part of the initial diagnostic evaluation, and intestinal wall-thickening was found in 21 (87.5%) of them.

Either surgery or gastrointestinal biopsy was performed in 16 (57%) of the patients; the surgical procedures included 2 cholecystectomies and 1 bone marrow biopsy. Only 1 case was diagnosed on the basis of clinical suspicion and abdominal radiographs alone.

The combination of intestinal and stomach angioedema was found in only 2 cases.

Two patients were kept on an ACE inhibitor in spite of symptoms and intestinal wall edema that showed a migratory pattern on imaging after chronic exposure.

The thickening involved the jejunum in 14 patients (50%), the ileum in 8 (29%), the duodenum in 5 (18%), the stomach in 2, and the sigmoid colon in 1.

In 12 cases (43%), visceral angioedema and its symptoms resolved within 48 hours of stopping the ACE inhibitor.

A DIAGNOSIS TO KEEP IN MIND

As we have seen, the diagnosis of visceral angioedema needs to be kept in mind when a patient—especially a middle-aged woman—taking an ACE inhibitor presents with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, leukocytosis, ascites, and wall-thickening of the small bowel on imaging studies.9,35,36

The diagnosis is hard to establish, and in the interim the patient may undergo invasive and unnecessary procedures, which can be avoided by a heightened awareness of this complication. In all of the reported cases, the patients required hospitalization because of the severity of symptoms and attempts to exclude other possible diseases.36

POSSIBLY DUE TO BRADYKININ

Several theories have been proposed to explain how visceral angioedema is induced by ACE inhibitors. The possible mechanisms that have been described include the following:

- The accumulation of bradykinin and substance P secondary to the effect of the ACE inhibitor, which may lead to the inflammatory response, therefore increasing permeability of the vascular compartment

- Deficiency of complement and the enzymes carboxypeptidase N and alpha-1 antitrypsin

- An antibody-antigen reaction37

- Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone (suggested by the greater number of women represented38)

- Contrast media used for imaging39

- Genetic predisposition

- Inflammation due to acute-phase proteins

- C1-inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction (however, the levels of C1/C4 and the C1-esterase inhibitor functional activity usually are normal2,10,40).

Many other theories are being explored.11,12,38,41–53

The most plausible mechanism is an increase in the levels of bradykinin and its metabolites.45 The absence of ACE can lead to breakdown of bradykinin to des-Arg bradykinin via the minor pathway, which can lead to more pronounced vasodilation and vascular permeability.54,55 During an acute attack of angioedema secondary to ACE inhibition, the bradykinin concentration can increase to more than 10 times the normal level.56

Moreover, C-reactive protein levels were higher (mean 4.42 mg/dL ± 0.15 mg/dL) in patients with ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema than in those with other causes of angioedema (P < .0001).52 The patients taking ACE inhibitors without any previous angioedema had normal C-reactive protein levels (0.39 mg/dL ± 0.1 mg/dL).52

INCIDENCE RATES

In our review of the literature, all of the patients were taking an ACE inhibitor, and some were taking both an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB).

Initially, the incidence rate of angioedema was thought to be 0.1% to 0.2%, but recently the Omapatrilat Cardiovascular Treatment Assessment vs Enalapril (OCTAVE) trial had more than 12,000 patients on enalapril and reported the incidence of angioedema to be 0.68%,57 with a higher risk in women than in men (0.84% vs 0.54%)58 and a relative risk of 3.03 for blacks compared with whites.59

Even though ARBs seem to be safer, angioedema can recur in up to one-third of patients who switch from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB.60–63

Moreover, one study in the United States found that the frequency of hospital admission of patients with angioedema increased from 8,839 per year in 1998 to 11,925 in 2005, and the cost was estimated to be close to $123 million in 2005.64

Interestingly, when angioedema involved the face, it developed within the first week in 60% of cases,65 whereas when visceral angioedema developed, it did so within the first week in 59% of cases. Therefore, the timing of the onset is similar regardless of the body area involved.

Smokers who developed ACE-inhibitor-induced cough had a higher risk of ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema in a retrospective cohort study by Morimoto,66 but no relationship to the area of involvement was made.

ON IMAGING, A THICKENED BOWEL WALL

Computed tomography can reveal bowel edema and ascites more reliably than plain radiography or barium studies. Edema thickens the bowel wall, with increased contrast enhancement that makes mesenteric vessels show up on the study. In some instances edema is so significant that edematous submucosa can be differentiated from the serosa due to impressive thickening of the mucosal wall.15,16 Oral contrast can be seen in the middle of the lumen, giving it a target-sign appearance. Edema of the small bowel and ascites can lead to fluid sequestration in the abdomen, resulting in a presentation with shock.67

Magnetic resonance imaging can be even more useful in identifying gastrointestinal angioedema, but it would not be cost-effective, and based on our study, CT and ultrasonography of the abdomen were diagnostic in most cases.

AVOIDING UNNECESSARY TESTING

Hemodynamic instability and abdominal pain usually trigger a surgical consult and a more extensive workup, but with a good clinical approach, unnecessary testing and invasive diagnostic procedures can be avoided under the right circumstances.

Numerous surgical procedures have been reported in patients presenting with visceral angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.67 Although a thorough history and physical examination can give us a clue in the diagnosis of drug-induced gastrointestinal angioedema, CT is extremely helpful, as it shows dilated loops, thickened mucosal folds, perihepatic fluid, ascites, mesenteric edema, and a “doughnut” or “stacked coin” appearance.17,68

So far, there have been only two reports of angioedema of the stomach (the case reported by Shahzad et al10 and the current report). Angioedema can affect any visceral organ, but we usually see involvement of the jejunum followed by the ileum and duodenum.40

FINDINGS ON ENDOSCOPY

Usually, endoscopic examination of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract does not reveal any specific pathology, but endoscopy and biopsy can rule out other causes of abdominal pain, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, infection, malignancy, granuloma, and vasculitis. Also, hereditary or acquired C1-esterase deficiency and other autoimmune disorders should be considered in the workup.18,69 In the reported cases, endoscopy revealed petechial bleeding with generalized edema.19

Biopsy often demonstrates an expanded edematous submucosal layer with inflammatory cell infiltration and protrusion of the proper muscular layer into the submucosal layer.15 A proper muscular layer and an edematous submucosal layer can produce edema so severe as to obstruct the intestine.15

Ultrasonography or CT provides essential information as to location, structure, and size, and it rules out other diagnoses. Therefore, consideration should be given to noninvasive imaging studies and laboratory testing (C1-esterase inhibitor, complement, antinuclear antibody, complete metabolic panel, complete blood cell count) before resorting to endoscopy or exploratory laparotomy.20,70 In three case reports,29,30,32 abdominal ultrasonography did not show any thickening of the small-bowel wall. Several cases have been diagnosed with the help of endoscopy.

Symptoms usually resolve when the ACE inhibitor is stopped

There is no standard treatment for ACE-inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. In most patients, stopping the drug, giving nothing by mouth, and giving intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration are sufficient. Symptoms usually resolve within 48 hours.

In several case reports, fresh-frozen plasma was used to increase the levels of kininase II, which can degrade high levels of bradykinin.51,71,72 However, no randomized controlled trial of fresh-frozen plasma for ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema has been published.

Drugs for hereditary angioedema—eg, recombinant C1-INH, the kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide (Kalbitor), and the BKR-2-antagonist icatibant (Firazyr)73—have not been prospectively studied in gastrointestinal angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors. Icatibant has been shown to be effective in the treatment of hereditary angioedema and could be promising in treating angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.8 Rosenberg et al21 described a patient who was on prednisone when she developed intestinal angioedema, thus calling into question the efficacy of steroids in the treatment of visceral angioedema.

RAISING AWARENESS

More than 40 million patients are currently taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs.9 Therefore, we suggest that patients with a known history of angioedema in response to these drugs should wear an identification bracelet to increase awareness and to prevent recurrence of angioedema.

A 57-year-old black woman presented to the emergency department with severe, dull abdominal pain associated with nonbilious vomiting and nausea. She had diabetes mellitus and hypertension, for which she had been taking metformin (Glucophage) 500 mg twice a day and lisinopril (available as Prinivil and Zestril) 20 mg daily for the last 4 years.

Multiple admissions in the past 4 years

The patient started taking lisinopril 10 mg daily in 2005, and she presented to her medical provider 2 weeks later with abdominal discomfort. Colonoscopy was performed, which revealed a benign polyp. She continued taking her medications, including lisinopril.

She continued to occasionally have abdominal pain of variable severity, but it was tolerable until 6 months later, when she presented to the emergency department with severe recurrent abdominal pain.

In view of the clinical picture, her physicians decided to treat her for small bowel obstruction, and an exploratory laparotomy was performed. The surgeons noted that she had moderate ascites, adhesions on the omentum, and a thickened high loop of the small bowel that was unequivocally viable and hyperemic, with thickening of the mesentery. Ascitic fluid was evacuated, adhesions were lysed, and the abdomen was closed. She was discharged with the same medications, including lisinopril; the dose was subsequently increased for better control of her hypertension.

The woman was admitted three more times within the same year for the same symptoms and underwent multiple workups for pancreatitis, gastritis, small-bowel obstruction, and other common gastrointestinal diseases.

Present admission

On review of systems, she denied any dry cough, weight loss or gain, food allergies, new medications, or hematochezia.

On physical examination, she had hypoactive bowel sounds and diffuse tenderness with guarding around the epigastric area.

Laboratory tests did not reveal any abnormalities; in particular, her C1 esterase concentration was normal. Stool studies were negative for infectious diseases.

Plain radiography of the abdomen showed a nonobstructive bowel-gas pattern.

She was diagnosed with gastrointestinal angioedema secondary to angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor therapy. Her lisinopril was discontinued, and the symptoms resolved completely in 24 hours. On follow-up 8 weeks and 16 months later, her symptoms had not returned.

A RARE COMPLICATION OF ACE-INHIBITOR THERAPY

Angioedema occurs in 0.1% to 0.7% of patients taking ACE inhibitors, and it can affect about 1 of 2,500 patients during the first week of exposure.1–3 It usually manifests as swelling of the face, tongue, and lips, and in rare cases, the gastrointestinal wall. Thus, visceral angioedema is a rare complication of ACE-inhibitor therapy.

Because angioedema is less obvious when it involves abdominal organs, it presents a diagnostic challenge. It is placed lower in the differential diagnosis, as other, more common, and occasionally more high-risk medical conditions are generally considered first. Most of the time, the diagnosis is missed. Some physicians may not be aware of this problem, since only a few case reports have been published. Nevertheless, this potential complication needs to be considered when any patient receiving ACE inhibitors for treatment of hypertension, myocardial infarction, heart failure, or diabetic nephropathy presents with diffuse abdominal pain, diarrhea, or edema of the upper airways.4–8

If a high level of suspicion is applied along with good clinical judgment, then hospitalizations, unnecessary procedures, patient discomfort, and unnecessary health care costs can be prevented.

A MEDLINE SEARCH

To investigate the characteristics associated with this unusual presentation, including the time of symptom onset, the types of symptoms, and the diagnostic studies performed on the patients with visceral angioedema, we performed a MEDLINE search to identify case reports and case series published in English from 1980 to 2010 on the topic of abdominal or visceral angioedema. The search terms used were “visceral,” “intestinal angioedema,” “ACE-inhibitor side effects,” and the names of various ACE inhibitors.

Pertinent articles were identified, and clinical characteristics were collected, including demographics, onset of symptoms, the drug’s name, and others. In our summary below, data are presented as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

SUMMARY OF REPORTED CASES

Our search revealed 27 reported cases of visceral angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors (a table summarizing our findings is available).9–34 The drug most often involved was lisinopril (11 cases), followed by enalapril (Vasotec) (8 cases).

Twenty-three (82%) of the cases were in women. The mean age of the patients was 49.5 ± 12.2 years (range 29–77 years); the mean age was 46.7 ± 11.7 years in women and 57 ± 13 years in men. Unfortunately, the race and ethnicity of the patients was documented in only some cases.

In 15 (54%) of the cases, the patient presented to a physician or emergency department within 72 hours (41.1 ± 17.4) of starting therapy, and in 8 cases the patient presented between 2 weeks and 18 months.

In 10 cases (including the case we are reporting here), the patients were kept on ACE inhibitors from 2 to 9 years after the initial presentation, as the diagnosis was missed.9,12,14,18,20,31,32 In 2 cases, the dose of the ACE inhibitor had been increased after the patient presented with the abdominal pain.

All of the patients were hospitalized for further diagnostic workup.

As for the presenting symptoms, all the patients had abdominal pain, 24 (86%) had emesis, 14 (50%) had diarrhea, and 20 (71%) had ascites. Laboratory results were mostly nonspecific. Twelve (44%) of the patients had leukocytosis. The C1 esterase inhibitor concentration was measured in 18 patients, and the results were normal in all of them.

Twenty-four (86%) of the patients underwent abdominal and pelvic CT or ultrasonography as part of the initial diagnostic evaluation, and intestinal wall-thickening was found in 21 (87.5%) of them.

Either surgery or gastrointestinal biopsy was performed in 16 (57%) of the patients; the surgical procedures included 2 cholecystectomies and 1 bone marrow biopsy. Only 1 case was diagnosed on the basis of clinical suspicion and abdominal radiographs alone.

The combination of intestinal and stomach angioedema was found in only 2 cases.

Two patients were kept on an ACE inhibitor in spite of symptoms and intestinal wall edema that showed a migratory pattern on imaging after chronic exposure.

The thickening involved the jejunum in 14 patients (50%), the ileum in 8 (29%), the duodenum in 5 (18%), the stomach in 2, and the sigmoid colon in 1.

In 12 cases (43%), visceral angioedema and its symptoms resolved within 48 hours of stopping the ACE inhibitor.

A DIAGNOSIS TO KEEP IN MIND

As we have seen, the diagnosis of visceral angioedema needs to be kept in mind when a patient—especially a middle-aged woman—taking an ACE inhibitor presents with abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea, leukocytosis, ascites, and wall-thickening of the small bowel on imaging studies.9,35,36

The diagnosis is hard to establish, and in the interim the patient may undergo invasive and unnecessary procedures, which can be avoided by a heightened awareness of this complication. In all of the reported cases, the patients required hospitalization because of the severity of symptoms and attempts to exclude other possible diseases.36

POSSIBLY DUE TO BRADYKININ

Several theories have been proposed to explain how visceral angioedema is induced by ACE inhibitors. The possible mechanisms that have been described include the following:

- The accumulation of bradykinin and substance P secondary to the effect of the ACE inhibitor, which may lead to the inflammatory response, therefore increasing permeability of the vascular compartment

- Deficiency of complement and the enzymes carboxypeptidase N and alpha-1 antitrypsin

- An antibody-antigen reaction37

- Hormones such as estrogen and progesterone (suggested by the greater number of women represented38)

- Contrast media used for imaging39

- Genetic predisposition

- Inflammation due to acute-phase proteins

- C1-inhibitor deficiency or dysfunction (however, the levels of C1/C4 and the C1-esterase inhibitor functional activity usually are normal2,10,40).

Many other theories are being explored.11,12,38,41–53

The most plausible mechanism is an increase in the levels of bradykinin and its metabolites.45 The absence of ACE can lead to breakdown of bradykinin to des-Arg bradykinin via the minor pathway, which can lead to more pronounced vasodilation and vascular permeability.54,55 During an acute attack of angioedema secondary to ACE inhibition, the bradykinin concentration can increase to more than 10 times the normal level.56

Moreover, C-reactive protein levels were higher (mean 4.42 mg/dL ± 0.15 mg/dL) in patients with ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema than in those with other causes of angioedema (P < .0001).52 The patients taking ACE inhibitors without any previous angioedema had normal C-reactive protein levels (0.39 mg/dL ± 0.1 mg/dL).52

INCIDENCE RATES

In our review of the literature, all of the patients were taking an ACE inhibitor, and some were taking both an ACE inhibitor and an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB).

Initially, the incidence rate of angioedema was thought to be 0.1% to 0.2%, but recently the Omapatrilat Cardiovascular Treatment Assessment vs Enalapril (OCTAVE) trial had more than 12,000 patients on enalapril and reported the incidence of angioedema to be 0.68%,57 with a higher risk in women than in men (0.84% vs 0.54%)58 and a relative risk of 3.03 for blacks compared with whites.59

Even though ARBs seem to be safer, angioedema can recur in up to one-third of patients who switch from an ACE inhibitor to an ARB.60–63

Moreover, one study in the United States found that the frequency of hospital admission of patients with angioedema increased from 8,839 per year in 1998 to 11,925 in 2005, and the cost was estimated to be close to $123 million in 2005.64

Interestingly, when angioedema involved the face, it developed within the first week in 60% of cases,65 whereas when visceral angioedema developed, it did so within the first week in 59% of cases. Therefore, the timing of the onset is similar regardless of the body area involved.

Smokers who developed ACE-inhibitor-induced cough had a higher risk of ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema in a retrospective cohort study by Morimoto,66 but no relationship to the area of involvement was made.

ON IMAGING, A THICKENED BOWEL WALL

Computed tomography can reveal bowel edema and ascites more reliably than plain radiography or barium studies. Edema thickens the bowel wall, with increased contrast enhancement that makes mesenteric vessels show up on the study. In some instances edema is so significant that edematous submucosa can be differentiated from the serosa due to impressive thickening of the mucosal wall.15,16 Oral contrast can be seen in the middle of the lumen, giving it a target-sign appearance. Edema of the small bowel and ascites can lead to fluid sequestration in the abdomen, resulting in a presentation with shock.67

Magnetic resonance imaging can be even more useful in identifying gastrointestinal angioedema, but it would not be cost-effective, and based on our study, CT and ultrasonography of the abdomen were diagnostic in most cases.

AVOIDING UNNECESSARY TESTING

Hemodynamic instability and abdominal pain usually trigger a surgical consult and a more extensive workup, but with a good clinical approach, unnecessary testing and invasive diagnostic procedures can be avoided under the right circumstances.

Numerous surgical procedures have been reported in patients presenting with visceral angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.67 Although a thorough history and physical examination can give us a clue in the diagnosis of drug-induced gastrointestinal angioedema, CT is extremely helpful, as it shows dilated loops, thickened mucosal folds, perihepatic fluid, ascites, mesenteric edema, and a “doughnut” or “stacked coin” appearance.17,68

So far, there have been only two reports of angioedema of the stomach (the case reported by Shahzad et al10 and the current report). Angioedema can affect any visceral organ, but we usually see involvement of the jejunum followed by the ileum and duodenum.40

FINDINGS ON ENDOSCOPY

Usually, endoscopic examination of the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract does not reveal any specific pathology, but endoscopy and biopsy can rule out other causes of abdominal pain, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, infection, malignancy, granuloma, and vasculitis. Also, hereditary or acquired C1-esterase deficiency and other autoimmune disorders should be considered in the workup.18,69 In the reported cases, endoscopy revealed petechial bleeding with generalized edema.19

Biopsy often demonstrates an expanded edematous submucosal layer with inflammatory cell infiltration and protrusion of the proper muscular layer into the submucosal layer.15 A proper muscular layer and an edematous submucosal layer can produce edema so severe as to obstruct the intestine.15

Ultrasonography or CT provides essential information as to location, structure, and size, and it rules out other diagnoses. Therefore, consideration should be given to noninvasive imaging studies and laboratory testing (C1-esterase inhibitor, complement, antinuclear antibody, complete metabolic panel, complete blood cell count) before resorting to endoscopy or exploratory laparotomy.20,70 In three case reports,29,30,32 abdominal ultrasonography did not show any thickening of the small-bowel wall. Several cases have been diagnosed with the help of endoscopy.

Symptoms usually resolve when the ACE inhibitor is stopped

There is no standard treatment for ACE-inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. In most patients, stopping the drug, giving nothing by mouth, and giving intravenous fluids to prevent dehydration are sufficient. Symptoms usually resolve within 48 hours.

In several case reports, fresh-frozen plasma was used to increase the levels of kininase II, which can degrade high levels of bradykinin.51,71,72 However, no randomized controlled trial of fresh-frozen plasma for ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema has been published.

Drugs for hereditary angioedema—eg, recombinant C1-INH, the kallikrein inhibitor ecallantide (Kalbitor), and the BKR-2-antagonist icatibant (Firazyr)73—have not been prospectively studied in gastrointestinal angioedema associated with ACE inhibitors. Icatibant has been shown to be effective in the treatment of hereditary angioedema and could be promising in treating angioedema secondary to ACE inhibitors.8 Rosenberg et al21 described a patient who was on prednisone when she developed intestinal angioedema, thus calling into question the efficacy of steroids in the treatment of visceral angioedema.

RAISING AWARENESS

More than 40 million patients are currently taking ACE inhibitors or ARBs.9 Therefore, we suggest that patients with a known history of angioedema in response to these drugs should wear an identification bracelet to increase awareness and to prevent recurrence of angioedema.

- Brown NJ, Snowden M, Griffin MR. Recurrent angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated angioedema. JAMA 1997; 278:232–233.

- Israili ZH, Hall WD. Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. A review of the literature and pathophysiology. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:234–242.

- Messerli FH, Nussberger J. Vasopeptidase inhibition and angiooedema. Lancet 2000; 356:608–609.

- Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2007–2018.

- Jessup M. The less familiar face of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:224–226.

- Chobanian AV. Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:789–796.

- Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2005; 366:2026–2033.

- Weber MA, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema: estimating the risk. Hypertension 2008; 51:1465–1467.

- Oudit G, Girgrah N, Allard J. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema of the intestine: Case report, incidence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Can J Gastroenterol 2001; 15:827–832.

- Shahzad G, Korsten MA, Blatt C, Motwani P. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-associated angioedema of the stomach and small intestine: a case report. Mt Sinai J Med 2006; 73:1123–1125.

- Chase MP, Fiarman GS, Scholz FJ, MacDermott RP. Angioedema of the small bowel due to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000; 31:254–257.

- Mullins RJ, Shanahan TM, Dobson RT. Visceral angioedema related to treatment with an ACE inhibitor. Med J Aust 1996; 165:319–321.

- Schmidt TD, McGrath KM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema of the intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2002; 324:106–108.

- Smoger SH, Sayed MA. Simultaneous mucosal and small bowel angioedema due to captopril. South Med J 1998; 91:1060–1063.

- Tojo A, Onozato ML, Fujita T. Repeated subileus due to angioedema during renin-angiotensin system blockade. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:36–38.

- De Backer AI, De Schepper AM, Vandevenne JE, Schoeters P, Michielsen P, Stevens WJ. CT of angioedema of the small bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176:649–652.

- Marmery H, Mirvis SE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. Clin Radiol 2006; 61:979–982.

- Orr KK, Myers JR. Intermittent visceral edema induced by long-term enalapril administration. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38:825–827.

- Spahn TW, Grosse-Thie W, Mueller MK. Endoscopic visualization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema as a cause of relapsing abdominal pain using double-balloon enteroscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53:1257–1260.

- Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Landis ME, Heppell JP. Isolated visceral angioedema: an underdiagnosed complication of ACE inhibitors? Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:1201–1204.

- Rosenberg EI, Mishra G, Abdelmalek MF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced isolated visceral angioedema in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation 2003; 75:730–732.

- Salloum H, Locher C, Chenard A, et al. [Small bowel angioedema due to perindopril]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005; 29:1180–1181.

- Arakawa M, Murata Y, Rikimaru Y, Sasaki Y. Drug-induced isolated visceral angioneurotic edema. Intern Med 2005; 44:975–978.

- Abdelmalek MF, Douglas DD. Lisinopril-induced isolated visceral angioedema: review of ACE-inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42:847–850.

- Gregory KW, Davis RC. Images in clinical medicine. Angioedema of the intestine. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1641.

- Farraye FA, Peppercorn MA, Steer ML, Joffe N, Rees M. Acute small-bowel mucosal edema following enalapril use. JAMA 1988; 259:3131.

- Jacobs RL, Hoberman LJ, Goldstein HM. Angioedema of the small bowel caused by an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89:127–128.

- Herman L, Jocums SB, Coleman MD. A 29-year-old woman with crampy abdominal pain. Tenn Med 1999; 92:272–273.

- Guy C, Cathébras P, Rousset H. Suspected angioedema of abdominal viscera. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121:900.

- Dupasquier E. [A rare clinical form of angioneurotic edema caused by enalapril: acute abdomen]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1994; 87:1371–1374.

- Jardine DL, Anderson JC, McClintock AD. Delayed diagnosis of recurrent visceral angio-oedema secondary to ACE inhibitor therapy. Aust N Z J Med 1999; 29:377–378.

- Matsumura M, Haruki K, Kajinami K, Takada T. Angioedema likely related to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Intern Med 1993; 32:424–426.

- Khan MU, Baig MA, Javed RA, et al. Benazepril induced isolated visceral angioedema: a rare and under diagnosed adverse effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Int J Cardiol 2007; 118:e68–e69.

- Adhikari SP, Schneider JI. An unusual cause of abdominal pain and hypotension: angioedema of the bowel. J Emerg Med 2009; 36:23–25.

- Gibbs CR, Lip GY, Beevers DG. Angioedema due to ACE inhibitors: increased risk in patients of African origin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48:861–865.

- Johnsen SP, Jacobsen J, Monster TB, Friis S, McLaughlin JK, Sørensen HT. Risk of first-time hospitalization for angioedema among users of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists. Am J Med 2005; 118:1428–1329.

- Bi CK, Soltani K, Sloan JB, Weber RR, Elliott WJ, Murphy MB. Tissue-specific autoantibodies induced by captopril. Clin Res 1987; 35:922A.

- Bork K, Dewald G. Hereditary angioedema type III, angioedema associated with angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and female sex. Am J Med 2004; 116:644–645.

- Witten DM, Hirsch FD, Hartman GW. Acute reactions to urographic contrast medium: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to history of hypersensitivity states. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 119:832–840.

- Eck SL, Morse JH, Janssen DA, Emerson SG, Markovitz DM. Angioedema presenting as chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:436–439.

- Coleman JW, Yeung JH, Roberts DH, Breckenridge AM, Park BK. Drug-specific antibodies in patients receiving captopril. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 22:161–165.

- Kallenberg CG. Autoantibodies during captopril treatment. Arthritis Rheum 1985; 28:597–598.

- Inman WH, Rawson NS, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Speirs CJ. Postmarketing surveillance of enalapril. I: Results of prescription-event monitoring. BMJ 1988; 297:826–829.

- Lefebvre J, Murphey LJ, Hartert TV, Jiao Shan R, Simmons WH, Brown NJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in patients with ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema. Hypertension 2002; 39:460–464.

- Molinaro G, Cugno M, Perez M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema is characterized by a slower degradation of des-arginine(9)-bradykinin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:232–237.

- Adam A, Cugno M, Molinaro G, Perez M, Lepage Y, Agostoni A. Aminopeptidase P in individuals with a history of angiooedema on ACE inhibitors. Lancet 2002; 359:2088–2089.

- Binkley KE, Davis A. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic characterization of a novel estrogen-dependent inherited form of angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:546–550.

- Yeung JH, Coleman JW, Park BK. Drug-protein conjugates—IX. Immunogenicity of captopril-protein conjugates. Biochem Pharmacol 1985; 34:4005–4012.

- Abbosh J, Anderson JA, Levine AB, Kupin WL. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema more prevalent in transplant patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999; 82:473–476.

- Pichler WJ, Lehner R, Späth PJ. Recurrent angioedema associated with hypogonadism or anti-androgen therapy. Ann Allergy 1989; 63:301–305.

- Bass G, Honan D. Octaplas is not equivalent to fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of acute angioedema. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2007; 24:1062–1063.

- Bas M, Hoffmann TK, Bier H, Kojda G. Increased C-reactive protein in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59:233–238.

- Herman AG. Differences in structure of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors might predict differences in action. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:102C–108C.

- Cunnion KM, Lee JC, Frank MM. Capsule production and growth phase influence binding of complement to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immunol 2001; 69:6796–6803.

- Cunnion KM, Wagner E, Frank MM. Complement and kinins. In:Parlow TG, Stites DP, Imboden JB, editors. Medical Immunology. 10th ed. New York, NY: Lange Medical Books; 2001:186–188.

- Pellacani A, Brunner HR, Nussberger J. Plasma kinins increase after angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in human subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994; 87:567–574.

- Bristol-Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute. FDA Advisory Committee Briefing Book for OMAPATRILAT Tablets NDA 21-188. www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/02/briefing/3877B2_01_BristolMeyersSquibb.pdf. Accessed 2/4/2011.

- Kostis JB, Kim HJ, Rusnak J, et al. Incidence and characteristics of angioedema associated with enalapril. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1637–1642.

- Mahoney EJ, Devaiah AK. Angioedema and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: are demographics a risk? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2008; 139:105–108.

- Warner KK, Visconti JA, Tschampel MM. Angiotensin II receptor blockers in patients with ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema. Ann Pharmacother 2000; 34:526–528.

- Kyrmizakis DE, Papadakis CE, Liolios AD, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2004; 130:1416–1419.

- MacLean JA, Hannaway PJ. Angioedema and AT1 receptor blockers: proceed with caution. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:1488–1489,

- Abdi R, Dong VM, Lee CJ, Ntoso KA. Angiotensin II receptor blocker-associated angioedema: on the heels of ACE inhibitor angioedema. Pharmacotherapy 2002; 22:1173–1175.

- Lin RY, Shah SN. Increasing hospitalizations due to angioedema in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101:185–192.

- Slater EE, Merrill DD, Guess HA, et al. Clinical profile of angioedema associated with angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibition. JAMA 1988; 260:967–970.

- Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Fiskio JM, et al. An evaluation of risk factors for adverse drug events associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. J Eval Clin Pract 2004; 10:499–509.

- Cohen N, Sharon A, Golik A, Zaidenstein R, Modai D. Hereditary angioneurotic edema with severe hypovolemic shock. J Clin Gastroenterol 1993; 16:237–239.

- Ciaccia D, Brazer SR, Baker ME. Acquired C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency causing intestinal angioedema: CT appearance. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 161:1215–1216.

- Malcolm A, Prather CM. Intestinal angioedema mimicking Crohn’s disease. Med J Aust 1999; 171:418–420.

- Schmidt TD, McGrath KM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema of the intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2002; 324:106–108.

- Karim MY, Masood A. Fresh-frozen plasma as a treatment for life-threatening ACE-inhibitor angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002; 109:370–371.

- Warrier MR, Copilevitz CA, Dykewicz MS, Slavin RG. Fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of resistant angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004; 92:573–575.

- Bas M, Adams V, Suvorava T, Niehues T, Hoffmann TK, Kojda G. Nonallergic angioedema: role of bradykinin. Allergy 2007; 62:842–856.

- Agostoni A, Cicardi M, Cugno M, Zingale LC, Gioffré D, Nussberger J. Angioedema due to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Immunopharmacology 1999; 44:21–25.

- Brown NJ, Snowden M, Griffin MR. Recurrent angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor–associated angioedema. JAMA 1997; 278:232–233.

- Israili ZH, Hall WD. Cough and angioneurotic edema associated with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. A review of the literature and pathophysiology. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:234–242.

- Messerli FH, Nussberger J. Vasopeptidase inhibition and angiooedema. Lancet 2000; 356:608–609.

- Jessup M, Brozena S. Heart failure. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:2007–2018.

- Jessup M. The less familiar face of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003; 41:224–226.

- Chobanian AV. Clinical practice. Isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:789–796.

- Casas JP, Chua W, Loukogeorgakis S, et al. Effect of inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system and other antihypertensive drugs on renal outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2005; 366:2026–2033.

- Weber MA, Messerli FH. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angioedema: estimating the risk. Hypertension 2008; 51:1465–1467.

- Oudit G, Girgrah N, Allard J. ACE inhibitor-induced angioedema of the intestine: Case report, incidence, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Can J Gastroenterol 2001; 15:827–832.

- Shahzad G, Korsten MA, Blatt C, Motwani P. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor-associated angioedema of the stomach and small intestine: a case report. Mt Sinai J Med 2006; 73:1123–1125.

- Chase MP, Fiarman GS, Scholz FJ, MacDermott RP. Angioedema of the small bowel due to an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. J Clin Gastroenterol 2000; 31:254–257.

- Mullins RJ, Shanahan TM, Dobson RT. Visceral angioedema related to treatment with an ACE inhibitor. Med J Aust 1996; 165:319–321.

- Schmidt TD, McGrath KM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor angioedema of the intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Sci 2002; 324:106–108.

- Smoger SH, Sayed MA. Simultaneous mucosal and small bowel angioedema due to captopril. South Med J 1998; 91:1060–1063.

- Tojo A, Onozato ML, Fujita T. Repeated subileus due to angioedema during renin-angiotensin system blockade. Am J Med Sci 2006; 332:36–38.

- De Backer AI, De Schepper AM, Vandevenne JE, Schoeters P, Michielsen P, Stevens WJ. CT of angioedema of the small bowel. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176:649–652.

- Marmery H, Mirvis SE. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced visceral angioedema. Clin Radiol 2006; 61:979–982.

- Orr KK, Myers JR. Intermittent visceral edema induced by long-term enalapril administration. Ann Pharmacother 2004; 38:825–827.

- Spahn TW, Grosse-Thie W, Mueller MK. Endoscopic visualization of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema as a cause of relapsing abdominal pain using double-balloon enteroscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53:1257–1260.

- Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Landis ME, Heppell JP. Isolated visceral angioedema: an underdiagnosed complication of ACE inhibitors? Mayo Clin Proc 2000; 75:1201–1204.

- Rosenberg EI, Mishra G, Abdelmalek MF. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced isolated visceral angioedema in a liver transplant recipient. Transplantation 2003; 75:730–732.

- Salloum H, Locher C, Chenard A, et al. [Small bowel angioedema due to perindopril]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2005; 29:1180–1181.

- Arakawa M, Murata Y, Rikimaru Y, Sasaki Y. Drug-induced isolated visceral angioneurotic edema. Intern Med 2005; 44:975–978.

- Abdelmalek MF, Douglas DD. Lisinopril-induced isolated visceral angioedema: review of ACE-inhibitor-induced small bowel angioedema. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42:847–850.

- Gregory KW, Davis RC. Images in clinical medicine. Angioedema of the intestine. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1641.

- Farraye FA, Peppercorn MA, Steer ML, Joffe N, Rees M. Acute small-bowel mucosal edema following enalapril use. JAMA 1988; 259:3131.

- Jacobs RL, Hoberman LJ, Goldstein HM. Angioedema of the small bowel caused by an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Gastroenterol 1994; 89:127–128.

- Herman L, Jocums SB, Coleman MD. A 29-year-old woman with crampy abdominal pain. Tenn Med 1999; 92:272–273.

- Guy C, Cathébras P, Rousset H. Suspected angioedema of abdominal viscera. Ann Intern Med 1994; 121:900.

- Dupasquier E. [A rare clinical form of angioneurotic edema caused by enalapril: acute abdomen]. Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss 1994; 87:1371–1374.

- Jardine DL, Anderson JC, McClintock AD. Delayed diagnosis of recurrent visceral angio-oedema secondary to ACE inhibitor therapy. Aust N Z J Med 1999; 29:377–378.

- Matsumura M, Haruki K, Kajinami K, Takada T. Angioedema likely related to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Intern Med 1993; 32:424–426.

- Khan MU, Baig MA, Javed RA, et al. Benazepril induced isolated visceral angioedema: a rare and under diagnosed adverse effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors. Int J Cardiol 2007; 118:e68–e69.

- Adhikari SP, Schneider JI. An unusual cause of abdominal pain and hypotension: angioedema of the bowel. J Emerg Med 2009; 36:23–25.

- Gibbs CR, Lip GY, Beevers DG. Angioedema due to ACE inhibitors: increased risk in patients of African origin. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48:861–865.

- Johnsen SP, Jacobsen J, Monster TB, Friis S, McLaughlin JK, Sørensen HT. Risk of first-time hospitalization for angioedema among users of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor antagonists. Am J Med 2005; 118:1428–1329.

- Bi CK, Soltani K, Sloan JB, Weber RR, Elliott WJ, Murphy MB. Tissue-specific autoantibodies induced by captopril. Clin Res 1987; 35:922A.

- Bork K, Dewald G. Hereditary angioedema type III, angioedema associated with angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and female sex. Am J Med 2004; 116:644–645.

- Witten DM, Hirsch FD, Hartman GW. Acute reactions to urographic contrast medium: incidence, clinical characteristics and relationship to history of hypersensitivity states. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1973; 119:832–840.

- Eck SL, Morse JH, Janssen DA, Emerson SG, Markovitz DM. Angioedema presenting as chronic gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88:436–439.

- Coleman JW, Yeung JH, Roberts DH, Breckenridge AM, Park BK. Drug-specific antibodies in patients receiving captopril. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 22:161–165.

- Kallenberg CG. Autoantibodies during captopril treatment. Arthritis Rheum 1985; 28:597–598.

- Inman WH, Rawson NS, Wilton LV, Pearce GL, Speirs CJ. Postmarketing surveillance of enalapril. I: Results of prescription-event monitoring. BMJ 1988; 297:826–829.

- Lefebvre J, Murphey LJ, Hartert TV, Jiao Shan R, Simmons WH, Brown NJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity in patients with ACE-inhibitor-associated angioedema. Hypertension 2002; 39:460–464.

- Molinaro G, Cugno M, Perez M, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-associated angioedema is characterized by a slower degradation of des-arginine(9)-bradykinin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 303:232–237.

- Adam A, Cugno M, Molinaro G, Perez M, Lepage Y, Agostoni A. Aminopeptidase P in individuals with a history of angiooedema on ACE inhibitors. Lancet 2002; 359:2088–2089.

- Binkley KE, Davis A. Clinical, biochemical, and genetic characterization of a novel estrogen-dependent inherited form of angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2000; 106:546–550.

- Yeung JH, Coleman JW, Park BK. Drug-protein conjugates—IX. Immunogenicity of captopril-protein conjugates. Biochem Pharmacol 1985; 34:4005–4012.

- Abbosh J, Anderson JA, Levine AB, Kupin WL. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor-induced angioedema more prevalent in transplant patients. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 1999; 82:473–476.

- Pichler WJ, Lehner R, Späth PJ. Recurrent angioedema associated with hypogonadism or anti-androgen therapy. Ann Allergy 1989; 63:301–305.

- Bass G, Honan D. Octaplas is not equivalent to fresh frozen plasma in the treatment of acute angioedema. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2007; 24:1062–1063.

- Bas M, Hoffmann TK, Bier H, Kojda G. Increased C-reactive protein in ACE-inhibitor-induced angioedema. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2005; 59:233–238.

- Herman AG. Differences in structure of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors might predict differences in action. Am J Cardiol 1992; 70:102C–108C.

- Cunnion KM, Lee JC, Frank MM. Capsule production and growth phase influence binding of complement to Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immunol 2001; 69:6796–6803.