User login

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability ... Rash and hives not taken seriously enough ... More

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

Failure to monitor INR leads to severe bleeding, disability

A MAN WITH A HISTORY OF DEEP VEIN THROMBOSIS was taking warfarin 10 mg every even day and 7.5 mg every odd day. His physician changed the warfarin dosage while the patient was taking ciprofloxacin, then resumed the original regimen once the patient finished taking the antibiotic.

No new prescriptions were written to confirm the change nor, the patient claimed, was a proper explanation of the new regimen provided. His international normalized ratio (INR) wasn’t checked after the dosage change.

After 2 weeks on the new warfarin dosage, the patient went to the emergency department (ED) complaining of groin pain and a change in urine color. Urinalysis found red blood cells too numerous to count. Although the patient told the ED staff he was taking warfarin, they didn’t check his INR. He was given a diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) and discharged.

Three days later, the patient returned to the ED because of increased bleeding from his Foley catheter. Once again his INR wasn’t checked and he was discharged with a UTI diagnosis and a prescription for antibiotics. Two days afterwards, he was taken back to the hospital bleeding from all orifices. His INR was 75.

The patient spent a month in the hospital, most of it in the intensive care unit, followed by 3 months in a rehabilitation facility before returning home. He remained confined to a hospital bed.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The physician and hospital were negligent for failing to instruct the patient regarding the change in warfarin dosage and neglecting to check his INR.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $700,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT The management of anticoagulation has numerous pitfalls for the unwary. Careful monitoring can save lives—and lawsuits.

Rash and hives not taken seriously enough

A HISTORY OF 3 SEIZURES in a 7-year-old boy prompted a neurologist to prescribe valproic acid. The neurologist later added lamotrigine because of the child’s behavior problems. After taking both medications for 2 weeks, the child developed a rash, at which point the neurologist discontinued the lamotrigine and started diphenhydramine.

The following day, the child was brought to the ED with an itchy rash and hives on his torso and extremities. An allergic reaction was diagnosed and the child was discharged with instructions to take diphenhydramine along with acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. When informed of the ED visit, the neurologist requested a follow-up appointment in 4 weeks.

Two days later, the child was back in the ED because the rash had progressed to include redness and swelling of the face. Once again, he was discharged with a diagnosis of allergic reaction and instructions to take diphenhydramine and acetaminophen.

Two days afterward, the child was taken to a different ED, from which he was airlifted to a tertiary care center and admitted to the intensive care unit for treatment of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. The condition advanced to toxic epidermal necrolysis with sloughing of skin and the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. Several weeks later, the child died.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The neurologist was negligent in prescribing lamotrigine for the behavior problem instead of referring the boy to a child psychologist. The lamotrigine dosage was excessive; the neurologist didn’t respond properly to the report of a rash.

The pharmacist was negligent in failing to contact the neurologist to discuss the excessive dosage. Discharging the child from the ED with a life-threatening drug reaction was unreasonable.

THE DEFENSE The defendants denied that they were negligent or caused the child’s death. They were prepared to present the histories of the parents, whose backgrounds included drug abuse, and state investigations regarding the care of the child.

VERDICT $1.55 million Washington settlement.

COMMENT When prescribing a drug with a potentially serious adverse effect, it’s always prudent to document patient education and follow-up thoroughly. Even though hindsight is 20/20, an “allergic reaction” in a patient on lamotrigine should raise red flags.

Delay in spotting compartment syndrome has permanent consequences

SEVERE NUMBNESS, TINGLING, AND PAIN IN HER LEFT CALF brought a 20-year-old woman to the ED. She couldn’t lift her left foot or bear weight on her left foot or leg. She reported awakening with the symptoms after a New Year’s Eve party the previous evening. After an examination, but no tests, she was discharged with a diagnosis of “floppy foot syndrome” and a prescription for a non-narcotic pain medication.

The young woman went to another ED the next day, complaining of continued pain and swelling in her left calf. She was admitted to the hospital for an orthopedic consultation, which resulted in a diagnosis of compartment syndrome. By that time, the patient had gone into renal failure from rhabdomyolysis caused by tissue breakdown. She underwent a fasciotomy, after which she required hemodialysis (until her kidney function returned) and rehabilitation. Damage to the nerves of her left calf and leg left her with permanent foot drop.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM The hospital was negligent in failing to diagnose compartment syndrome when the woman went to the ED. Proper diagnosis and treatment at that time would have prevented the nerve damage and foot drop.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $750,000 Maryland settlement.

COMMENT Compartment syndrome can be challenging to recognize. Recently I have come across several allegations of malpractice for untimely diagnosis. Remember this important problem when faced with a patient with leg pain.

Multiple errors end in death from pneumonia

A 24-YEAR-OLD MAN WITH CHEST PAIN AND A COUGH went to his physician, who diagnosed chest wall pain and prescribed a narcotic pain reliever. The young man returned the next day complaining of increased chest pain. He said he’d been spitting up blood-stained sputum. He was perspiring and vomited in the doctor’s waiting room. The doctor diagnosed an upper respiratory infection and prescribed a cough syrup containing more narcotics.

Later that day the patient had a radiograph at a hospital. It revealed pneumonia. Shortly afterward, the hospital confirmed by fax with the doctor’s office that the doctor had received the results. The doctor didn’t read the radiograph results for 2 days.

After the doctor read the radiograph report, his office tried to contact the patient but misdialed his phone number, then made no further attempts at contact. The patient’s former wife found him at home unresponsive. He was admitted to the ED, where he died of pneumonia shortly thereafter.

PLAINTIFF’S CLAIM No information about the plaintiff’s claim is available.

THE DEFENSE No information about the defense is available.

VERDICT $1.85 million net verdict in Virginia.

COMMENT A cascade of mistakes (sometimes referred to as the Swiss cheese effect) occurs, and a preventable death results. Are you at risk for such an event? What fail-safe measures do you have in place in your practice?

ACIP immunization update

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

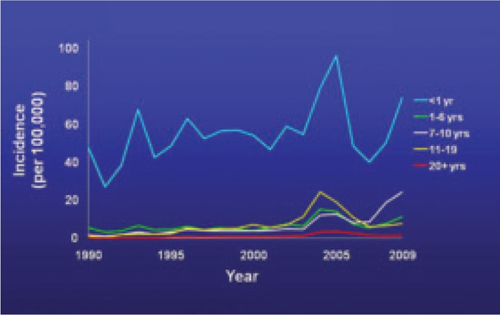

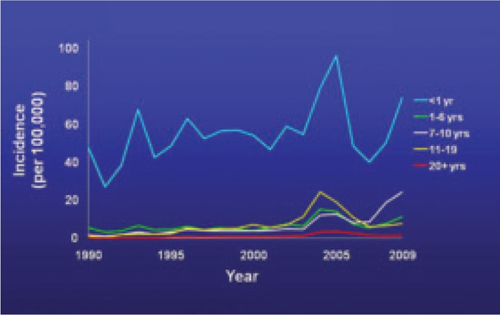

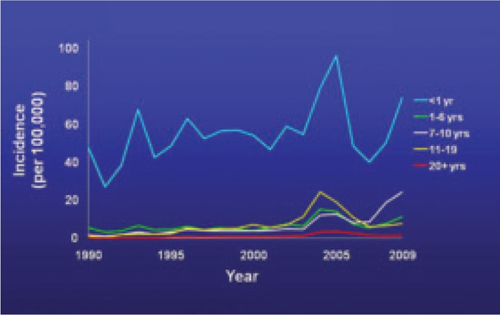

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

Keeping up with the ever-changing immunization schedules recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) can be difficult. The most recent changes are the interim recommendations from the February 2011 ACIP meeting pertaining to tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP) for health care personnel. Updated schedules for routine immunization of children and adults that incorporate additions and changes made in the preceding year were published by the CDC in February.1,2

ACIP widens the scope of pertussis prevention

The past decade has seen an increase in pertussis cases, including an increase in the number of cases among infants and adolescents (FIGURE). In 2010, California reported 8383 cases, including 10 infant deaths. This was the highest number and rate of cases reported in more than 50 years.3 Other states have also experienced recent increases.

This evolving epidemiology of pertussis has prompted ACIP to recommend a routine single Tdap dose for adolescents between the ages of 11 and 18 years who have completed the recommended DTP/DTaP (diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and pertussis/diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis) vaccination series and for adults ages 19 to 64 years. ACIP also recommends a single dose for children ages 7 to 10 if they are not fully vaccinated against pertussis and for adults 65 and older who have not previously received Tdap and who are in close contact with infants. The last 2 are off-label recommendations. ACIP has also eliminated any recommended interval between the time of vaccination with tetanus or diphtheriatoxoid (Td) containing vaccine and the administration of Tdap.4

FIGURE

Reported pertussis incidence by age group, 1990-2009

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): surveillance and reporting. Available at: www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed March 21, 2011.

2 new recommendations for clinician postexposure prophylaxis

Interim recommendations from the most recent ACIP meeting in February 20115 re-emphasize that health care personnel should receive Tdap and recommend that health care facilities take steps to increase adherence, including providing the vaccine at no cost.5

Since health care personnel are at increased risk of exposure to pertussis, ACIP also made 2 recommendations for PEP.

- All health care personnel (vaccinated or not) in close contact with a pertussis patient (as defined in TABLE 1) who are likely to expose patients at high risk for complications from pertussis (infants <1 year of age and those with certain immunodeficiency conditions, chronic lung disease, respiratory insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis) should receive PEP.

- Exposed personnel who do not work with high-risk patients should receive PEP or be monitored daily for 21 days, treated at first signs of infection, and excluded from patient contact for 5 days if symptoms develop. The antimicrobials and doses for treatment and prevention of pertussis have been published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.6 Options for PEP include azithromycin, clarithromycin, erythromycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.6

TABLE 1

Definition of close contact with a pertussis patient

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005.6 |

Coming soon: Complete vaccine recommendations for health care workers

Recent experience with pertussis (and influenza) has highlighted the need for health care personnel to be vaccinated against infectious diseases to protect themselves, their patients, and their families. To that end, ACIP plans to publish a compendium later this year that brings together all recommendations regarding immunizations for health care personnel. When it becomes available, family physicians will be able to refer to this document to ensure that they and their staff are immunized in line with CDC recommendations.

The latest on influenza vaccine, PCV13, MCV4, hepatitis B, and HPV

The most notable additions to the routine schedules ACIP announced during the past year are universal, yearly influenza immunization from the age of 6 months on and the replacement of the 7-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV7) with a 13-valent product (PCV13) for infants and children. Details of these recommendations, including how to transition from PCV7 to PCV13, were published late last year by the CDC and described in another Practice Alert.7-9

In addition, changes were made in the schedules for meningococcal conjugate vaccine. A 2-dose primary series, instead of a single dose, of MCV4 is now recommended for those with compromised immunity. A booster of MCV4 is now recommended at age 16 for those vaccinated at 11 or 12 years, and at age 16 to 18 for those vaccinated at 13 to 15 years.10 The MCV4 recommendations are summarized in TABLE 2.

More schedule details in the footnotes. The new schedules contain a number of clarifications in the footnotes that:1,11

- explain the spacing of the 3-dose primary series for hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) for infants if they do not receive a dose immediately after birth

- clarify the circumstances in which children younger than age 9 need 2 doses of influenza vaccine

- describe the availability of both a quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV4) and a bivalent vaccine (HPV2) to prevent precancerous cervical lesions and cancer

- list the option for using HPV4 for males for the prevention of genital warts.

TABLE 2

Meningococcal conjugate vaccine recommendations by risk group, ACIP 2010

| Risk group | Primary series | Booster dose |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals ages 11-18 years | 1 dose, preferably at age 11 or 12 years |

|

| HIV-infected individuals ages 11-18 years | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with persistent complement component deficiency such as C5-C9, properdin, or factor D, or functional or anatomic asplenia | 2 doses, 2 months apart |

|

| Individuals ages 2-55 years with prolonged increased risk of exposure, such as microbiologists routinely working with Neisseria meningitidis and travelers to, or residents of, countries where meningococcal disease is hyperendemic or epidemic | 1 dose |

|

| Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011.10 | ||

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended immunization schedules for persons aged 0 through 18 years—United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep QuickGuide. 2011;60(5):1-4.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended adult immunization schedule-United States, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):1-4.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (whooping cough): outbreaks. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed March 19, 2011.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(1):13-15.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. ACIP presentation slides: February 2011 meeting. Available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/slides-feb11.htm#pertussis. Accessed March 19, 2011.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommended antimicrobial agents for treatment and postexposure prophylaxis of pertussis: 2005 CDC guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-14):1-16.

7. Prevention and control of influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-8):1-62.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of pneumococcal disease among infants and children—use of 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine—recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-11):1-18.

9. Campos-Outcalt D. Your guide to the new pneumococcal vaccine for children. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:394-398.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated recommendations for use of meningococcal conjugate vaccines—Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:72-76.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:626-629.

Returning traveler with painful penile mass

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis

The clinical history was consistent with a diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis complicated by a periurethral gland abscess. The location of the swelling was most consistent with an abscess in the Tyson’s gland (also known as tysonitis). The Tyson’s (or preputial) glands of the penis are sebaceous-type glands on either side of the frenulum at the balanopreputial sulcus.1 In women, an abscess of the periurethral Skene’s gland is an analogous gonorrheal complication.

Case reports of gonorrheal infection of Tyson’s gland have documented infection with and without symptoms of urethritis.2-4 Diagnosis in this case was confirmed by sending the discharge for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which was positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and negative for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Other diagnostic possibilities. The differential diagnosis of acute swelling on the penile shaft includes syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, Behçet’s syndrome, a drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, scabies, trauma, and cancer.5

How this patient’s attempt at “safe sex” failed

Oropharyngeal gonococcal infection was the route of transmission implicated in this patient’s infection. When specifically asked about his sexual encounter, our patient admitted that while he was diligent about using a condom for intercourse, he did not use a condom when he received oral sex.

The prevalence of pharyngeal involvement is estimated to be 10% to 20% among women and MSM (men who have sex with men) who have genital gonorrheal infection.6 The risk of contracting N gonorrhoeae when receiving oral sex from an infected partner is unknown.

A common disease, a not-so-common complication

Genital infection by N gonorrhoeae remains the second most common notifiable disease in the United States, with 301,174 cases reported in 2009.7 Effective antimicrobial treatment has reduced the occurrence of local complications of gonococcal infection. Nevertheless, complications of gonococcal urethritis like the ones that follow do occur.

Acute epididymitis is the most common complication of urethral gonorrhea. It is characterized by a swollen and inflamed scrotum, localized epididymal pain, fever, and pyuria.8

Penile edema (“bull-headed clap”) is another common complication.8 It may be limited to the meatus or extend to the distal penile shaft and prepuce and may occur in the absence of other inflammatory signs.

Urethral stricture, once thought to be a common complication, is actually relatively rare, occurring in just 0.5% of cases.6 Urethral strictures attributed to gonorrheal urethritis during the pre-antibiotic era may have actually resulted from the caustic treatments administered during that time.

Acute prostatitis with sudden onset of chills, fever, malaise, and warmth and swelling of the prostate can also develop, although it is more commonly caused by gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli or Proteus mirabilis.8

Chronic prostatitis, usually caused by recurrent urinary tract infections, has also been documented as a complication of gonorrheal infection.9

Infection of the Cowper’s, or bulbourethral glands, can occur, leading to perineal swelling.10

Periurethral abscess results when an infected Littre’s or Tyson’s gland ruptures and the infection extends into the deeper tissues.11

Seminal vesiculitis has previously been described as an uncommon complication of gonorrheal infection. However, a recent small study showed ultrasonographic evidence of vesiculitis in 46% of patients with urethritis due to gonorrhea or chlamydia.12

Penile sclerosing lymphangitis presents as an acute, firm, cordlike lesion of the coronal sulcus. A quarter of reported cases have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea.13

NAAT is key to diagnosis

Infection with genitourinary N gonorrhoeae can be detected in various ways, including gram staining of a male urethral specimen, culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and NAAT. NAAT, which we used with our patient, has the advantage of being approved for use with urine specimens from men and women, as well as with endocervical or urethral samples.

Diagnosis of nongenital infection (ie, pharynx, rectum) typically requires culture. Other diagnostic methods are not FDA-approved for use with specimens from nongenital sites and may yield false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with organisms other than N gonorrhoeae.14 Patients tested for gonorrhea should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Treat patients with ceftriaxone

Treatment for tysonitis is similar to treatment for gonococcal urethritis and centers on the use of appropriate antibiotics.15 Quinolone-resistant N gonorrhoeae is increasingly common; it is estimated that up to 40% of strains in Asia are now quinolone resistant.16 Because of this, the CDC recommends treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.17 As with urethritis, presumptive treatment for chlamydia is warranted. For tysonitis, incision and drainage may also be necessary.18

A good outcome for our patient

This patient was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g as a single oral dose. The abscess was incised and drained under local anesthesia, with 2 cc of pus obtained.

Five days after treatment, the patient reported feeling much better. He was told to call the clinic if he didn’t have complete resolution in 2 weeks. He did not report any further problems.

CORRESPONDENCE Andrew Schechtman, MD, San Jose-O’Connor Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 455 O’Connor Drive,#210, San Jose, CA 95128; [email protected]

1. Batistatou A, Panelos J, Zioga A, et al. Ectomic modified sebaceous glands in human penis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:355-356.

2. Burgess JA. Gonococcal tysonitis without urethritis after prophylactic post-coital urination. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:40-41.

3. Bavidge KJ. Letter: gonococcal infection of the penis. Br J Vener Dis. 1976;52:66.-

4. Abdul Gaffoor PM. Gonococcal tysonitis. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:869-870.

5. Frenkl T, Potts J. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2007:371–385.

6. Nelson AL. Gonorrheal infections. In: Nelson AL, Woodward JA, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Practical Guide for Primary Care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:153–182.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011.

8. Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Sparling PF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone 2009;2753-2770.

9. Adler MW. ABC of sexually transmitted diseases: complications of common genital infections and infections in other sites. Br Med J. 1983;287:1709-1712.

10. Subramanian S. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis and periurethral abscess. Sex Transm Dis. 1981;8:77-78.

11. Komolafe AJ, Cornford PA, Fordham MV, et al. Periurethral abscess complicating male gonococcal urethritis treated by surgical incision and drainage. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:857-858.

12. Furuya R, Takahashi S, Furuya S, et al. Is urethritis accompanied by seminal vesiculitis? Int J Urol. 2009;16:628-631.

13. Rosen T, Hwong H. Sclerosing lymphangitis of the penis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:916-918.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/2006/urethritis-and-cervicitis.htm#uc6. Accessed January 26, 2010.

15. el-Benhawi MO, el-Tonsy MH. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis. Cutis. 1988;41:425-426.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—Hawaii and California, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1041-1044.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

18. Fiumara NJ. Gonococcal tysonitis. Br J Vener Dis. 1977;53:145.

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis

The clinical history was consistent with a diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis complicated by a periurethral gland abscess. The location of the swelling was most consistent with an abscess in the Tyson’s gland (also known as tysonitis). The Tyson’s (or preputial) glands of the penis are sebaceous-type glands on either side of the frenulum at the balanopreputial sulcus.1 In women, an abscess of the periurethral Skene’s gland is an analogous gonorrheal complication.

Case reports of gonorrheal infection of Tyson’s gland have documented infection with and without symptoms of urethritis.2-4 Diagnosis in this case was confirmed by sending the discharge for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which was positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and negative for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Other diagnostic possibilities. The differential diagnosis of acute swelling on the penile shaft includes syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, Behçet’s syndrome, a drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, scabies, trauma, and cancer.5

How this patient’s attempt at “safe sex” failed

Oropharyngeal gonococcal infection was the route of transmission implicated in this patient’s infection. When specifically asked about his sexual encounter, our patient admitted that while he was diligent about using a condom for intercourse, he did not use a condom when he received oral sex.

The prevalence of pharyngeal involvement is estimated to be 10% to 20% among women and MSM (men who have sex with men) who have genital gonorrheal infection.6 The risk of contracting N gonorrhoeae when receiving oral sex from an infected partner is unknown.

A common disease, a not-so-common complication

Genital infection by N gonorrhoeae remains the second most common notifiable disease in the United States, with 301,174 cases reported in 2009.7 Effective antimicrobial treatment has reduced the occurrence of local complications of gonococcal infection. Nevertheless, complications of gonococcal urethritis like the ones that follow do occur.

Acute epididymitis is the most common complication of urethral gonorrhea. It is characterized by a swollen and inflamed scrotum, localized epididymal pain, fever, and pyuria.8

Penile edema (“bull-headed clap”) is another common complication.8 It may be limited to the meatus or extend to the distal penile shaft and prepuce and may occur in the absence of other inflammatory signs.

Urethral stricture, once thought to be a common complication, is actually relatively rare, occurring in just 0.5% of cases.6 Urethral strictures attributed to gonorrheal urethritis during the pre-antibiotic era may have actually resulted from the caustic treatments administered during that time.

Acute prostatitis with sudden onset of chills, fever, malaise, and warmth and swelling of the prostate can also develop, although it is more commonly caused by gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli or Proteus mirabilis.8

Chronic prostatitis, usually caused by recurrent urinary tract infections, has also been documented as a complication of gonorrheal infection.9

Infection of the Cowper’s, or bulbourethral glands, can occur, leading to perineal swelling.10

Periurethral abscess results when an infected Littre’s or Tyson’s gland ruptures and the infection extends into the deeper tissues.11

Seminal vesiculitis has previously been described as an uncommon complication of gonorrheal infection. However, a recent small study showed ultrasonographic evidence of vesiculitis in 46% of patients with urethritis due to gonorrhea or chlamydia.12

Penile sclerosing lymphangitis presents as an acute, firm, cordlike lesion of the coronal sulcus. A quarter of reported cases have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea.13

NAAT is key to diagnosis

Infection with genitourinary N gonorrhoeae can be detected in various ways, including gram staining of a male urethral specimen, culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and NAAT. NAAT, which we used with our patient, has the advantage of being approved for use with urine specimens from men and women, as well as with endocervical or urethral samples.

Diagnosis of nongenital infection (ie, pharynx, rectum) typically requires culture. Other diagnostic methods are not FDA-approved for use with specimens from nongenital sites and may yield false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with organisms other than N gonorrhoeae.14 Patients tested for gonorrhea should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Treat patients with ceftriaxone

Treatment for tysonitis is similar to treatment for gonococcal urethritis and centers on the use of appropriate antibiotics.15 Quinolone-resistant N gonorrhoeae is increasingly common; it is estimated that up to 40% of strains in Asia are now quinolone resistant.16 Because of this, the CDC recommends treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.17 As with urethritis, presumptive treatment for chlamydia is warranted. For tysonitis, incision and drainage may also be necessary.18

A good outcome for our patient

This patient was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g as a single oral dose. The abscess was incised and drained under local anesthesia, with 2 cc of pus obtained.

Five days after treatment, the patient reported feeling much better. He was told to call the clinic if he didn’t have complete resolution in 2 weeks. He did not report any further problems.

CORRESPONDENCE Andrew Schechtman, MD, San Jose-O’Connor Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 455 O’Connor Drive,#210, San Jose, CA 95128; [email protected]

WORRIED THAT HE MIGHT HAVE CONTRACTED CHLAMYDIA, a 27-year-old man visited our clinic for treatment. About 5 days earlier, he’d begun experiencing pain and a burning feeling when he urinated. Three days earlier, a painful lump near the head of his penis developed; the lump was growing.

The patient, who was otherwise healthy, had recently returned from a trip to Vietnam during which he reported having had sex with one female partner. He said, “I thought I was safe. I used a condom.”

On examination, he had a purulent urethral discharge and there was a fluctuant, yellowish-white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum (FIGURE). There were no ulcers. There was, however, a single 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area that was mobile, nontender, nonfluctuant, and of normal consistency.

FIGURE

Swelling with purulent discharge

In addition to the fluctuant, yellowish white, tender swelling on the left side of the frenulum, the patient had purulent urethral discharge and a single, 2-cm lymph node in the right inguinal area.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tysonitis

The clinical history was consistent with a diagnosis of gonococcal urethritis complicated by a periurethral gland abscess. The location of the swelling was most consistent with an abscess in the Tyson’s gland (also known as tysonitis). The Tyson’s (or preputial) glands of the penis are sebaceous-type glands on either side of the frenulum at the balanopreputial sulcus.1 In women, an abscess of the periurethral Skene’s gland is an analogous gonorrheal complication.

Case reports of gonorrheal infection of Tyson’s gland have documented infection with and without symptoms of urethritis.2-4 Diagnosis in this case was confirmed by sending the discharge for nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT), which was positive for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and negative for Chlamydia trachomatis.

Other diagnostic possibilities. The differential diagnosis of acute swelling on the penile shaft includes syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, Behçet’s syndrome, a drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn’s disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, scabies, trauma, and cancer.5

How this patient’s attempt at “safe sex” failed

Oropharyngeal gonococcal infection was the route of transmission implicated in this patient’s infection. When specifically asked about his sexual encounter, our patient admitted that while he was diligent about using a condom for intercourse, he did not use a condom when he received oral sex.

The prevalence of pharyngeal involvement is estimated to be 10% to 20% among women and MSM (men who have sex with men) who have genital gonorrheal infection.6 The risk of contracting N gonorrhoeae when receiving oral sex from an infected partner is unknown.

A common disease, a not-so-common complication

Genital infection by N gonorrhoeae remains the second most common notifiable disease in the United States, with 301,174 cases reported in 2009.7 Effective antimicrobial treatment has reduced the occurrence of local complications of gonococcal infection. Nevertheless, complications of gonococcal urethritis like the ones that follow do occur.

Acute epididymitis is the most common complication of urethral gonorrhea. It is characterized by a swollen and inflamed scrotum, localized epididymal pain, fever, and pyuria.8

Penile edema (“bull-headed clap”) is another common complication.8 It may be limited to the meatus or extend to the distal penile shaft and prepuce and may occur in the absence of other inflammatory signs.

Urethral stricture, once thought to be a common complication, is actually relatively rare, occurring in just 0.5% of cases.6 Urethral strictures attributed to gonorrheal urethritis during the pre-antibiotic era may have actually resulted from the caustic treatments administered during that time.

Acute prostatitis with sudden onset of chills, fever, malaise, and warmth and swelling of the prostate can also develop, although it is more commonly caused by gram-negative rods, such as Escherichia coli or Proteus mirabilis.8

Chronic prostatitis, usually caused by recurrent urinary tract infections, has also been documented as a complication of gonorrheal infection.9

Infection of the Cowper’s, or bulbourethral glands, can occur, leading to perineal swelling.10

Periurethral abscess results when an infected Littre’s or Tyson’s gland ruptures and the infection extends into the deeper tissues.11

Seminal vesiculitis has previously been described as an uncommon complication of gonorrheal infection. However, a recent small study showed ultrasonographic evidence of vesiculitis in 46% of patients with urethritis due to gonorrhea or chlamydia.12

Penile sclerosing lymphangitis presents as an acute, firm, cordlike lesion of the coronal sulcus. A quarter of reported cases have been linked to sexually transmitted infections, including gonorrhea.13

NAAT is key to diagnosis

Infection with genitourinary N gonorrhoeae can be detected in various ways, including gram staining of a male urethral specimen, culture, nucleic acid hybridization, and NAAT. NAAT, which we used with our patient, has the advantage of being approved for use with urine specimens from men and women, as well as with endocervical or urethral samples.

Diagnosis of nongenital infection (ie, pharynx, rectum) typically requires culture. Other diagnostic methods are not FDA-approved for use with specimens from nongenital sites and may yield false-positive results due to cross-reactivity with organisms other than N gonorrhoeae.14 Patients tested for gonorrhea should also be tested for other sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus.

Treat patients with ceftriaxone

Treatment for tysonitis is similar to treatment for gonococcal urethritis and centers on the use of appropriate antibiotics.15 Quinolone-resistant N gonorrhoeae is increasingly common; it is estimated that up to 40% of strains in Asia are now quinolone resistant.16 Because of this, the CDC recommends treatment with ceftriaxone and azithromycin.17 As with urethritis, presumptive treatment for chlamydia is warranted. For tysonitis, incision and drainage may also be necessary.18

A good outcome for our patient

This patient was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly and azithromycin 1 g as a single oral dose. The abscess was incised and drained under local anesthesia, with 2 cc of pus obtained.

Five days after treatment, the patient reported feeling much better. He was told to call the clinic if he didn’t have complete resolution in 2 weeks. He did not report any further problems.

CORRESPONDENCE Andrew Schechtman, MD, San Jose-O’Connor Hospital Family Medicine Residency, 455 O’Connor Drive,#210, San Jose, CA 95128; [email protected]

1. Batistatou A, Panelos J, Zioga A, et al. Ectomic modified sebaceous glands in human penis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:355-356.

2. Burgess JA. Gonococcal tysonitis without urethritis after prophylactic post-coital urination. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:40-41.

3. Bavidge KJ. Letter: gonococcal infection of the penis. Br J Vener Dis. 1976;52:66.-

4. Abdul Gaffoor PM. Gonococcal tysonitis. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:869-870.

5. Frenkl T, Potts J. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2007:371–385.

6. Nelson AL. Gonorrheal infections. In: Nelson AL, Woodward JA, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Practical Guide for Primary Care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:153–182.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011.

8. Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Sparling PF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone 2009;2753-2770.

9. Adler MW. ABC of sexually transmitted diseases: complications of common genital infections and infections in other sites. Br Med J. 1983;287:1709-1712.

10. Subramanian S. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis and periurethral abscess. Sex Transm Dis. 1981;8:77-78.

11. Komolafe AJ, Cornford PA, Fordham MV, et al. Periurethral abscess complicating male gonococcal urethritis treated by surgical incision and drainage. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:857-858.

12. Furuya R, Takahashi S, Furuya S, et al. Is urethritis accompanied by seminal vesiculitis? Int J Urol. 2009;16:628-631.

13. Rosen T, Hwong H. Sclerosing lymphangitis of the penis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:916-918.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/2006/urethritis-and-cervicitis.htm#uc6. Accessed January 26, 2010.

15. el-Benhawi MO, el-Tonsy MH. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis. Cutis. 1988;41:425-426.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—Hawaii and California, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1041-1044.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

18. Fiumara NJ. Gonococcal tysonitis. Br J Vener Dis. 1977;53:145.

1. Batistatou A, Panelos J, Zioga A, et al. Ectomic modified sebaceous glands in human penis. Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:355-356.

2. Burgess JA. Gonococcal tysonitis without urethritis after prophylactic post-coital urination. Br J Vener Dis. 1971;47:40-41.

3. Bavidge KJ. Letter: gonococcal infection of the penis. Br J Vener Dis. 1976;52:66.-

4. Abdul Gaffoor PM. Gonococcal tysonitis. Postgrad Med J. 1986;62:869-870.

5. Frenkl T, Potts J. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, eds. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2007:371–385.

6. Nelson AL. Gonorrheal infections. In: Nelson AL, Woodward JA, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Practical Guide for Primary Care. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2007:153–182.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf. Accessed March 25, 2011.

8. Marrazzo JM, Handsfield HH, Sparling PF. Neisseria gonorrhoeae. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone 2009;2753-2770.

9. Adler MW. ABC of sexually transmitted diseases: complications of common genital infections and infections in other sites. Br Med J. 1983;287:1709-1712.

10. Subramanian S. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis and periurethral abscess. Sex Transm Dis. 1981;8:77-78.

11. Komolafe AJ, Cornford PA, Fordham MV, et al. Periurethral abscess complicating male gonococcal urethritis treated by surgical incision and drainage. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:857-858.

12. Furuya R, Takahashi S, Furuya S, et al. Is urethritis accompanied by seminal vesiculitis? Int J Urol. 2009;16:628-631.

13. Rosen T, Hwong H. Sclerosing lymphangitis of the penis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:916-918.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2006. Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/STD/treatment/2006/urethritis-and-cervicitis.htm#uc6. Accessed January 26, 2010.

15. el-Benhawi MO, el-Tonsy MH. Gonococcal urethritis with bilateral tysonitis. Cutis. 1988;41:425-426.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fluoroquinolone-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae—Hawaii and California, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:1041-1044.

17. Workowski KA, Berman S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-12):1-110.

18. Fiumara NJ. Gonococcal tysonitis. Br J Vener Dis. 1977;53:145.

How effective—and safe—are systemic steroids for acute low back pain?

SHORT COURSES OF SYSTEMIC STEROIDS ARE LIKELY SAFE, but they are ineffective. A single dose of intramuscular (IM) or intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone doesn’t improve long-term pain scores in patients with low back pain and sciatica and produces conflicting effects on function. Oral prednisone (9-day taper) doesn’t improve pain or function in patients with back pain and sciatica. A single IM dose of methylprednisolone doesn’t improve pain scores or function in patients with back pain without sciatica (strength of recommendation: B, randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

No trials of corticosteroids for back pain reported an increase in adverse outcomes, but studies were small, and only short-term (1 month) follow-up data are available.

Evidence summary