User login

Medicare Fee Inspection

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

No one can call 2009 a dull year for healthcare policy. And 2010 already is shaping up as another humdinger, with several issues bubbling to the surface. One of the biggest comes courtesy of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care (www.dartmouthatlas.org), as politicians, analysts, researchers, and physicians grapple over how to resolve the contentious issue of geographical disparities in healthcare spending.

One of the main bodies of evidence driving the debate, the interactive Dartmouth map, depicts a color-coded nation in which wide swaths of the Midwest and West are colored with a pale green hue, which represents a significantly reduced amount of Medicare reimbursements. Meanwhile, states such as New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Florida, Texas, and Louisiana are marked by a darker shade of green—representing the nation’s most expensive per capita reimbursement rates.

Tucked within 2009’s massive Affordable Health Care for America Act passed by the House is a provision calling for a study of “geographic variation in healthcare spending and promoting high-value healthcare,” which is aiming for a more evenly colored landscape.

More than 50 legislators, hailing primarily from the Midwest and Pacific Northwest and calling themselves the Quality Care Coalition, pushed through the wording as a condition for supporting the larger healthcare reform bill. One measure would direct the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) to check the accuracy of the geographic adjustment factors that underlie existing Medicare reimbursements and suggest necessary revisions. The second would call upon the IOM “to conduct a study on geographic variation and growth in volume and intensity of services in per capita healthcare spending among the Medicare, Medicaid, privately insured, and uninsured populations.”

Recommendations to Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius as a result of that study would go into effect unless the House and Senate passed a joint resolution of disapproval with a two-thirds vote.

Reimbursement Battles

The implicit message is that some states, cities, and health providers have been shortchanged in their reimbursements—a complaint that flows into the larger meme that the country’s dysfunctional payment system rewards quantity, not quality. Officials at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., have suggested in media accounts that the current Medicare formula cost the clinic $840 million in lost reimbursements in 2008 alone.

Rep. Jay Inslee (D-Washington), whose district lies northwest of Seattle, served as one of the lead negotiators on the issue. According to Inslee spokesman Robert Kellar, the geographical disparity in healthcare spending has been a perennial concern for the Washington delegation due to reimbursement rates that lag by as much as 50%, depending on the procedure. “Hospitals haven’t been able to keep or attract the personnel that they could have because of this issue,” Kellar says. In Washington state, per capita Medicare reimbursements in 2006 hovered about $1,200 below the national average, though 15 other states, led by Hawaii, received even less.

Despite the specter of a skirmish between urban and rural states and hospitals, however, the Dartmouth Atlas suggests that many disparities are more geographically nuanced. In 2006, for example, the Miami hospital referral region received more than $16,300 in Medicare reimbursements per enrollee, while nearby Fort Lauderdale received $9,800 and Atlanta less than $7,400. By comparison, New York netted $12,100, Seattle received $7,200, Rochester, Minn., received $6,700, and Honolulu was reimbursed only $5,300.

Representatives of higher-spending areas have complained that the atlas doesn’t tell the whole story—that steep living costs, poorer populations seeking medical care, and infrastructure necessary for teaching institutions can drive up Medicare expenses. As part of a compromise negotiated with the Quality Care Coalition, the examination of per capita spending will not include expenses related to graduate medical education, disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments, and health information technology.

In attempting to get at the source of remaining cost disparities, however, the IOM has been charged with considering such factors as a local population’s relative health and socioeconomic status (race, ethnicity, gender, age, income, and education). The study will scrutinize healthcare providers’ organizational models, practice patterns, healthcare outcomes, quality benchmarks, and doctors’ discretion in making treatment decisions, among other criteria.

Differences of Opinion

Dylan Roby, an assistant professor at the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, says the general expectation among healthcare analysts is that significant differences will remain even with additional sophisticated modeling techniques. “The main hypothesis by most people in the field is that it’s differences in practice patterns that are really driving this, not differences in need or differences in disease burden,” he says.

But what about outcomes? A recent study of heart failure patients at six California hospitals seemed to throw cold water on the notion that higher resource use doesn’t equate with better results with patients.1 The study found more treatment did lead to higher odds of survival.

Roby thinks the study’s results lay the framework for looking at hospital-to-hospital differences in how providers deliver care and allocate resources, but he cautions that they shouldn’t be overanalyzed. All six of the California hospitals in the study are linked to universities and have ample access to resources, he points out.

HM at the Forefront

As for hospitalists, Roby hopes they will be increasingly called upon as focal points for improving efficiencies within provider networks. He concedes that plenty of challenges remain: An institution’s internal politics, for instance, could stymie even the most efficient and proactive physician. Even so, Roby is hopeful that an independent study could at least spur a dialogue about best practices. “I think what the study could potentially do, rather than just act as a way to penalize hospitals that might not be efficient with care, is really offer the ability for us to look at the characteristics of hospitals, in terms of how the care is delivered,” he says.

Ideally, the ability to learn would be followed by the impetus to change. But as analysts have noted, a panel’s recommendations on how to improve healthcare delivery don’t always neatly translate into federal policy.

Consider November’s uproar over mammogram recommendations. When the 16-member U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended that women wait until age 50 for routine mammograms instead of starting the screening process at 40, in large part to prevent overtreatment, the fallout was fast and furious. Sebelius quickly signaled in a strongly worded statement that federal policy wasn’t about to change, despite the evidence-based conclusions of a panel convened by her department’s Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A group of Republican legislators decried the recommendation as evidence of bureaucrats intruding on healthcare decisions, and even Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schulz (D-Florida), herself a breast-cancer survivor, called the panel’s recommendations “disturbing” and considered Congressional hearings.

The take-home message is readily transferrable to hospitalists: The perception that patients might receive less care can spark public upheaval and force policy makers to beat a hasty retreat away from evidence-based medicine.

Despite the best intentions, a federal panel’s recommendations over resolving geographical disparities in spending could unleash far more drama. Inevitably, such a study will identify both winners and losers, the latter of whom might not accept reduced payments willingly or quietly. TH

Bryn Nelson is a freelance writer based in Seattle.

Reference

- Ellis SG, Miller D, Keys TF. Comparing physician-specific two-year patient outcomes after coronary angiography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1278-1285.

Consultation Elimination

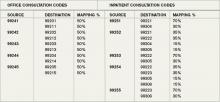

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

As of Jan. 1, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) ceased physician payment for consultations. The elimination of consult codes will affect physician group payments as well as relative-value-unit (RVU)-based incentive payments to individual physicians.

The Medicare-designated status of outpatient consultation (99241-99245) and inpatient consultation (99251-99255) codes has changed from “A” (separately payable under the physician fee schedule, when covered) to “I” (not valid for Medicare purposes; Medicare uses another code for the reporting of and the payment for these services). So if you submit consultation codes for Medicare beneficiaries, the result will be nonpayment.

While many physicians fear the negative impact of this ruling, hospitalists should consider its potential. Let’s take a look at a scenario hospitalists encounter on a routine basis.

Typical HM Scenario

A surgeon admits a 76-year-old man for aortic valve replacement. The patient’s history also includes well-controlled hypertension and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Postoperatively, the patient experiences an exacerbation of COPD related to anesthesia, elevated blood pressure, and hyperglycemia. The surgeon requests the hospitalist’s advice on appropriate medical interventions of these conditions. How should the hospitalist report the initial encounter with this Medicare beneficiary?

The hospitalist should select the CPT code that best fits the service and the payor. While most physicians regard this requested service as an inpatient consultation (99251-99255), Medicare no longer recognizes those codes. Instead, the hospitalist should report this encounter as an initial hospital care service (99221-99223).

Comanagement Issues

CMS and Medicare administrative contractors regularly uncover reporting errors for co-management requests. CMS decided the nature of these services were not consultative because the surgeon is not asking the physician or qualified nonphysician provider’s (NPP’s) opinion or advice for the surgeon’s use in treating the patient. Instead, these services constituted concurrent care and should have been billed using subsequent hospital care codes (99231-99233) in the hospital inpatient setting, subsequent NF care codes (99307-99310) in the SNF/NF setting, or office or other outpatient visit codes (99201-99215) in the office or outpatient settings.1

The new ruling simplifies coding and reduces reporting errors. The initial encounter with the patient is reported as such. Regardless of who is the attending of record or the consultant, the first physician from a particular provider group reports initial hospital care codes (i.e., 99221-99223) to represent the first patient encounter, even when this encounter does not occur on the admission date. Other physicians of the same specialty within the same provider group will not be permitted to report initial hospital care codes for their own initial encounter if someone from the group and specialty has already seen the patient during that hospitalization. In other words, the first hospitalist in the provider group reports 9922x, while the remaining hospitalists use subsequent hospital care codes (9923x).

In order to differentiate “consultant” services from “attending” services, CMS will be creating a modifier. The anticipated “AI” modifier must be appended to the attending physician’s initial encounter. Other initial hospital care codes reported throughout the hospital stay, as appropriate, are presumed to be that of “consultants” (i.e., physicians with a different specialty designation than the attending physician) participating in the case. Therefore, the hospitalist now can rightfully recover the increased work effort of the initial patient encounter (99223: 3.79 relative value units, ~$147 vs. 99233: 2.0 relative value units, ~$78, based on 2010 Medicare rates). Physicians will be required to meet the minimum documentation required for the selected visit code.

Other and Undefined Service Locations

Consultations in nursing facilities are handled much like inpatient hospital care. Physicians should report initial nursing facility services (99203-99306) for the first patient encounter, and subsequent nursing facility care codes (99307-99310) for each encounter thereafter. The attending physician of record appends the assigned modifier (presumed to be “AI”) when submitting their initial care service. All other initial care codes are presumed to be those of “consulting” physicians.

Initial information from CMS does not address observation services. Logically, these hospital-based services would follow the same methodology as inpatient care: report initial observation care (99218-99220) for the first “consulting” encounter. However, this might not be appropriate given Medicare’s existing rules for observation services, which guide physicians other than the admitting physician/group to “bill the office and other outpatient service codes or outpatient consultation codes as appropriate when they provide services to the patient.”2 With Medicare’s elimination of consultation codes, the consultant reports “office and other outpatient service codes” (i.e., new patient, 99201-99205, or established patient codes, 99212-99215) by default.

Without further clarification on observation services, hospitalists should report new or established patient service codes, depending on whether the patient has been seen by a group member within the last three years.

Medicare also has existing guidelines for the ED, which suggest that any physician not meeting the consultation criteria report ED service codes (99281-99285). Without further clarification, hospitalists should continue to follow this instruction for Medicare beneficiaries.

Nonphysician Providers

Medicare’s split/shared billing guidelines apply to most hospital inpatient, hospital outpatient, and ED evaluation and management (E/M) services, with consultations as one exception. Now, in accordance with the new ruling, hospitalists should select the appropriate initial service codes that correspond to patient’s location (e.g., 99223 for inpatients). NPPs can participate in the initial service provided to patients in these locations without the hospitalist having to replicate the entire service. The hospitalist can submit the claim in their name after selecting the visit level based upon the cumulative service personally provided on the same calendar day by both the NPP and the physician. TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center in Philadelphia. She also is faculty for SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.10I. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/ manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- Medicare Claims Processing Manual: Chapter 12, Section 30.6.8A. CMS Web site. Available at: www. cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Nov. 14, 2009.

- PFS Federal Regulation Notices: Proposed Revisions to Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Part B for CY 2010. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/itemdetail.asp?filterType=none&filterByDID=99&sortByDID=4&sortOrder=descending&itemID=CMS1223902&intNumPerPage=10. Accessed Nov. 12, 2009.

- Payment Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule and Other Revisions to Part B (for CY 2010). CMS Web site. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/OFR Upload/OFRData/2009-26502_PI.pdf. Accessed Nov. 10, 2009.

What Is the Appropriate Evaluation and Treatment of Funguria?

Case

A previously healthy 74-year-old female was admitted to the ICU nine days ago for treatment of severe streptococcal pneumonia. Her initial urine culture, which was collected on hospital day one, showed no growth; however, Candida albicans was isolated from a urine culture collected seven days later. Her second urinalysis revealed mild pyuria. What is the appropriate evaluation and treatment of funguria?

Background

Funguria is a relatively common clinical finding, and it is considerably more prevalent in patients with severe illnesses compared with healthy individuals. One study found that 2.2% of healthy, community-dwelling patients have Candida species (spp) in their urine.1 Candida spp are opportunistic organisms, which is implied by the fact that they can be isolated from 22% of patients admitted to an ICU.2

Despite the frequent isolation of Candida spp from urine cultures, the clinical significance is often unclear. It is difficult to determine if the funguria is caused by contamination, colonization, or a true urinary tract infection (UTI)—there is no test to reliably differentiate between these three possibilities. This is in contrast to bacterial UTIs, in which the findings of pyuria, bacteriuria, and a defined number of colony-forming units strongly support this diagnosis.3

Since it often is difficult to determine the true importance of funguria, its treatment has been controversial.3 The presence of a chronically indwelling urinary catheter often results in the funguria development, and, in many instances, simply removing the catheter will lead to its resolution.4 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that for most patients with asymptomatic funguria, treatment with antifungal therapy has no effect on morbidity or mortality.5,6 Also, the propensity for funguria recurrence after completion of a course of antifungal therapy often discourages clinicians from ordering pharmacologic therapy.7,8

Review of the Data

The prevalence of funguria is increasing worldwide, primarily due to the increased use of antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapy, as well as the more frequent utilization of invasive procedures.1,7 Candida spp cause as many as 30% of all nosocomial UTIs, and they are most commonly isolated from patients who require ICU treatment.9 In fact, in one large study, only 10.9% of 861 patients with funguria had no underlying illnesses.10

Common risk factors for funguria development include the use of urinary tract drainage devices, hyperalimentation, steroids, recent antibiotic therapy, diabetes mellitus, increased age, urinary tract abnormalities, female sex, malignancy, and a previous surgical procedure.1,2,3,7,10,11,12,13,14

By far, the most common cause of funguria is Candida spp. C. albicans is responsible for at least 50% of all cases of funguria.1,10 Other yeasts that cause funguria include C. glabrata (15.6%), C. tropicalis (7.9%), C. parapsilosis (4.1%), and C. krusei (1%).10

C. glabrata most often is isolated from individuals who have been treated with fluconazole, while C. parapsilos is seen most frequently in neonates. It is noteworthy that for approximately 10% of patients with candiduria, at least two types of Candida spp are isolated from the same urine culture.6,7,14 Other types of fungi that are infrequently isolated from the urine include Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Fusarium, Trichosporon, and such dimorphic fungi as Histoplasma capsulatum and Coccidioides immitis.6 The latter organisms tend to cause funguria in individuals who have a disseminated fungal infection.

Although funguria is a relatively common finding in some patient populations, there is uncertainty about its importance. This is because funguria might be present for one of several reasons, and differentiating colonization from true infection is difficult. Unfortunately, there are no established criteria that reliably differentiate the two entities.3 Most patients with funguria have no symptoms suggestive of a UTI (e.g., dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, or hematuria).1,6,7,10

For bacterial UTIs, the presence of pyuria, and a defined minimum number of colony-forming units (CFUs), is helpful in establishing this diagnosis.1,2,3,6 However, with funguria, neither of these parameters is helpful in distinguishing between colonization, contamination, or a true UTI. The reason is that pyuria commonly develops as a result of either coexistent bacteriuria or local irritation caused by the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter.1,7 Large numbers of fungal CFUs might indicate colonization only, which has no clinical significance.6,14

Candida spp often live as saprophytes on the skin in the genital and perineal areas.13 Women have a 10% to 65% rate of colonization of the vulvovestibular area with Candida spp.7 This readily allows for contamination of urine specimens during the collection process, and facilitates the introduction of organisms into the urinary bladder, particularly through the use of indwelling urinary catheters.6

Colonization of indwelling urinary devices universally occurs, as long as they remain inserted for substantial periods of time.6 Funguria is commonly observed with the use of either urethral or suprapubic catheters.4,7 Fortunately, intermittent urinary catheterization rarely is associated with the development of funguria.15 Additional substrates for the development of colonization include ureteral stents and nephrostomy tubes.7,14

UTIs due to fungi can present in several ways, including asymptomatic funguria, lower-tract UTIs, upper-tract UTIs, and renal candidiasis.7 Asymptomatic funguria is most commonly found in hospitalized patients who have indwelling urinary catheterization devices. Fungal lower-tract UTIs (i.e., cystitis) resulting in symptoms are uncommon in both catheterized and noncatheterized patients.15 Fungal upper-tract UTIs, which usually manifest as pyelonephritis or sepsis due to a UTI, cannot be distinguished from those with a bacterial etiology because their clinical presentations are similar.7 Upper-tract UTIs tend to occur in patients who have either urinary obstruction or a disorder that results in urinary stasis.7 Fungal balls (bezoars) might develop as a serious complication of an upper UTI, and can result in obstruction. Renal candidiasis usually develops as a result of hematogenous dissemination of a fungal infection.7,14

Funguria generally does not predispose to the development of fungemia, but when it does occur, it usually is due to the presence of an upper-urinary-tract obstruction.3,4,6,8,12,14

It has been estimated that disseminated infection can be expected to occur in 1.3% to 10.5% of immunosuppressed patients with funguria.1,3,6,10,15

Until fairly recently, it was thought that renal transplant patients with funguria were at increased risk for developing fungemia, but this assertion is now known to be false.5

In deciding whether to treat funguria, it is important to consider the clinical setting in which it occurs. For example, when funguria occurs in asymptomatic patients with an indwelling urinary catheter, it often is due to colonization of the catheter. In such instances, simply removing the catheter will result in the resolution of between 33% and 40% of funguria cases.1,12 For most patients with asymptomatic funguria, it has been shown that the administration of antifungal therapy has no significant effect on morbidity or mortality.6,16

However, for certain patient populations who are at increased risk for developing a disseminated fungal infection, the treatment of asymptomatic funguria is indicated. This includes neutropenic patients, those with a known urologic obstruction, and those who will undergo a urologic procedure.7 It also is important to recognize that for oncology patients, or those with sepsis, funguria might be the only manifestation of a disseminated fungal infection.6

All patients with symptomatic funguria require treatment with antifungal therapy.6 Septic patients who have funguria require blood cultures and radiologic imaging studies; the latter are obtained in order to localize the anatomic source of infection, and also to evaluate for urinary obstruction.6 Such patients require the prompt administration of appropriate systemic antifungal therapy; failure to do so doubles the risk of in-hospital mortality.2

Fluconazole is the most utilized medication for funguria treatment. Unlike itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole, it achieves high concentrations in the urine.7,12 The efficacy of Capsofungin for the treatment of funguria has not been established firmly.14,17 Flucytosine has a limited role in the treatment of funguria, but it is very useful in the treatment of non-C. albicans species, which are increasing in frequency and often are resistant to fluconazole.6,14

Amphotericin B bladder irrigation no longer is recognized as a first-line treatment for candiduria, although some investigators still support its use, particularly in special circumstances.15 With the ready availability of an oral agent, IV amphotericin B is not commonly utilized for the treatment of asymptomatic funguria. However, either IV amphotericin B or IV fluconazole are options for the treatment of renal candidiasis.3,7 Unfortunately, the recurrence of funguria after the completion of an appropriate course of antifungal therapy commonly occurs.3,6,8,14,15

Back to the Case

The patient’s initial blood and sputum cultures grew Streptococcus pneumoniae, which was adequately covered by the initial treatments of piperacillin/tazobactam and levofloxacin at the time of admission. Although the patient’s clinical condition improved gradually, she required ICU management throughout her hospital stay. Due to her poor mobility, an indwelling urinary catheter was inserted. The placement of this catheter, along with her age, sex, current antibiotic therapy, and debility, all increased her likelihood of developing funguria.

It is noteworthy that the patient had no suprapubic tenderness, and she had been afebrile for the preceeding 48 hours.

The finding of funguria in this patient should not create undue concern. The true source of her acute illness (Streptococcus pneumoniae) was identified. In this instance, there would be no expected benefit from the initiation of antifungal therapy. Instead, removal of the indwelling urinary drainage device would be advisable.

Bottom Line

Asymptomatic funguria is a common clinical finding, one in which further workups or the administration of antifungal therapy is not necessary in most cases. Symptomatic funguria always requires treatment. TH

Dr. Clarke is a clinical instructor in the section of hospital medicine at Emory University Medical Center in Atlanta. Dr. Razavi is an assistant professor in the section of hospital medicine at Emory.

References

- Colodner R, Nuri Y, Chazan B, Raz R. Community-acquired and hospital-acquired candiduria: comparison of prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:301-305.

- Blot S, Dimopoulos G, Rello J, Vogelaers D. Is Candida really a threat in the ICU? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:600-604.

- Kauffman, CA. Candiduria. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:S371-376.

- Goetz LL, Howard M, Cipher D, Revankar SG. Occurrence of candiduria in a population of chronically catheterized patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;doi:10.1038/SC.2009.81.

- Safdar N, Slattery WR, Knasinski V, et al. Predictors and outcomes of candiduria in renal transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1413-1421.

- Hollenbach E. To treat or not to treat—critically ill patients with candiduria. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl2):12-24.

- Lundstrom T, Sobel J. Nosocomial candiduria: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1602-1607.

- Sobel JD, Kauffman CA, McKinsey D, et al. Candiduria: A randomized, double-blind study of treatment with Fluconazole and placebo. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:19-24.

- Chen SC, Tong ZS, Lee OC, et al. Clinician response to Candida organisms in the urine of patients attending hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:201-208.

- Kauffman CA, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, et al. Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:14-18.

- Gubbins PO, McConnell SA, Penzak SR. Current management of funguria. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(19):1929-1935.

- Drew RH, Arthur RR, Perfect JR. Is it time to abandon the use of amphotericin B bladder irrigation? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1465-1470.

- Bromberg WD. How do UTIs due to Candida differ from other infections? Cortlandt Forum. 1998;11(2):210.

- Bukhary ZA. Candiduria: a review of clinical significance and management. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2008;19(3):350-360.

- Tuon FF, Amato VS, Filho SR. Bladder irrigation with amphotericin B and fungal urinary tract infection—systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J infect Dis. 2009;13(6):701-706.

- Simpson C, Blitz S, Shafran SD. The effect of current management on morbidity and mortality in hospitalized adults with funguria. J Infect. 2004;49(3):248-252.

- JD, Bradshaw SK, Lipka CJ, Kartsonis NA. Capsofungin in the treatment of symptomatic candiduria. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e46.

Case

A previously healthy 74-year-old female was admitted to the ICU nine days ago for treatment of severe streptococcal pneumonia. Her initial urine culture, which was collected on hospital day one, showed no growth; however, Candida albicans was isolated from a urine culture collected seven days later. Her second urinalysis revealed mild pyuria. What is the appropriate evaluation and treatment of funguria?

Background

Funguria is a relatively common clinical finding, and it is considerably more prevalent in patients with severe illnesses compared with healthy individuals. One study found that 2.2% of healthy, community-dwelling patients have Candida species (spp) in their urine.1 Candida spp are opportunistic organisms, which is implied by the fact that they can be isolated from 22% of patients admitted to an ICU.2

Despite the frequent isolation of Candida spp from urine cultures, the clinical significance is often unclear. It is difficult to determine if the funguria is caused by contamination, colonization, or a true urinary tract infection (UTI)—there is no test to reliably differentiate between these three possibilities. This is in contrast to bacterial UTIs, in which the findings of pyuria, bacteriuria, and a defined number of colony-forming units strongly support this diagnosis.3

Since it often is difficult to determine the true importance of funguria, its treatment has been controversial.3 The presence of a chronically indwelling urinary catheter often results in the funguria development, and, in many instances, simply removing the catheter will lead to its resolution.4 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that for most patients with asymptomatic funguria, treatment with antifungal therapy has no effect on morbidity or mortality.5,6 Also, the propensity for funguria recurrence after completion of a course of antifungal therapy often discourages clinicians from ordering pharmacologic therapy.7,8

Review of the Data

The prevalence of funguria is increasing worldwide, primarily due to the increased use of antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapy, as well as the more frequent utilization of invasive procedures.1,7 Candida spp cause as many as 30% of all nosocomial UTIs, and they are most commonly isolated from patients who require ICU treatment.9 In fact, in one large study, only 10.9% of 861 patients with funguria had no underlying illnesses.10

Common risk factors for funguria development include the use of urinary tract drainage devices, hyperalimentation, steroids, recent antibiotic therapy, diabetes mellitus, increased age, urinary tract abnormalities, female sex, malignancy, and a previous surgical procedure.1,2,3,7,10,11,12,13,14

By far, the most common cause of funguria is Candida spp. C. albicans is responsible for at least 50% of all cases of funguria.1,10 Other yeasts that cause funguria include C. glabrata (15.6%), C. tropicalis (7.9%), C. parapsilosis (4.1%), and C. krusei (1%).10

C. glabrata most often is isolated from individuals who have been treated with fluconazole, while C. parapsilos is seen most frequently in neonates. It is noteworthy that for approximately 10% of patients with candiduria, at least two types of Candida spp are isolated from the same urine culture.6,7,14 Other types of fungi that are infrequently isolated from the urine include Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Fusarium, Trichosporon, and such dimorphic fungi as Histoplasma capsulatum and Coccidioides immitis.6 The latter organisms tend to cause funguria in individuals who have a disseminated fungal infection.

Although funguria is a relatively common finding in some patient populations, there is uncertainty about its importance. This is because funguria might be present for one of several reasons, and differentiating colonization from true infection is difficult. Unfortunately, there are no established criteria that reliably differentiate the two entities.3 Most patients with funguria have no symptoms suggestive of a UTI (e.g., dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, or hematuria).1,6,7,10

For bacterial UTIs, the presence of pyuria, and a defined minimum number of colony-forming units (CFUs), is helpful in establishing this diagnosis.1,2,3,6 However, with funguria, neither of these parameters is helpful in distinguishing between colonization, contamination, or a true UTI. The reason is that pyuria commonly develops as a result of either coexistent bacteriuria or local irritation caused by the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter.1,7 Large numbers of fungal CFUs might indicate colonization only, which has no clinical significance.6,14

Candida spp often live as saprophytes on the skin in the genital and perineal areas.13 Women have a 10% to 65% rate of colonization of the vulvovestibular area with Candida spp.7 This readily allows for contamination of urine specimens during the collection process, and facilitates the introduction of organisms into the urinary bladder, particularly through the use of indwelling urinary catheters.6

Colonization of indwelling urinary devices universally occurs, as long as they remain inserted for substantial periods of time.6 Funguria is commonly observed with the use of either urethral or suprapubic catheters.4,7 Fortunately, intermittent urinary catheterization rarely is associated with the development of funguria.15 Additional substrates for the development of colonization include ureteral stents and nephrostomy tubes.7,14

UTIs due to fungi can present in several ways, including asymptomatic funguria, lower-tract UTIs, upper-tract UTIs, and renal candidiasis.7 Asymptomatic funguria is most commonly found in hospitalized patients who have indwelling urinary catheterization devices. Fungal lower-tract UTIs (i.e., cystitis) resulting in symptoms are uncommon in both catheterized and noncatheterized patients.15 Fungal upper-tract UTIs, which usually manifest as pyelonephritis or sepsis due to a UTI, cannot be distinguished from those with a bacterial etiology because their clinical presentations are similar.7 Upper-tract UTIs tend to occur in patients who have either urinary obstruction or a disorder that results in urinary stasis.7 Fungal balls (bezoars) might develop as a serious complication of an upper UTI, and can result in obstruction. Renal candidiasis usually develops as a result of hematogenous dissemination of a fungal infection.7,14

Funguria generally does not predispose to the development of fungemia, but when it does occur, it usually is due to the presence of an upper-urinary-tract obstruction.3,4,6,8,12,14

It has been estimated that disseminated infection can be expected to occur in 1.3% to 10.5% of immunosuppressed patients with funguria.1,3,6,10,15

Until fairly recently, it was thought that renal transplant patients with funguria were at increased risk for developing fungemia, but this assertion is now known to be false.5

In deciding whether to treat funguria, it is important to consider the clinical setting in which it occurs. For example, when funguria occurs in asymptomatic patients with an indwelling urinary catheter, it often is due to colonization of the catheter. In such instances, simply removing the catheter will result in the resolution of between 33% and 40% of funguria cases.1,12 For most patients with asymptomatic funguria, it has been shown that the administration of antifungal therapy has no significant effect on morbidity or mortality.6,16

However, for certain patient populations who are at increased risk for developing a disseminated fungal infection, the treatment of asymptomatic funguria is indicated. This includes neutropenic patients, those with a known urologic obstruction, and those who will undergo a urologic procedure.7 It also is important to recognize that for oncology patients, or those with sepsis, funguria might be the only manifestation of a disseminated fungal infection.6

All patients with symptomatic funguria require treatment with antifungal therapy.6 Septic patients who have funguria require blood cultures and radiologic imaging studies; the latter are obtained in order to localize the anatomic source of infection, and also to evaluate for urinary obstruction.6 Such patients require the prompt administration of appropriate systemic antifungal therapy; failure to do so doubles the risk of in-hospital mortality.2

Fluconazole is the most utilized medication for funguria treatment. Unlike itraconazole, ketoconazole, and voriconazole, it achieves high concentrations in the urine.7,12 The efficacy of Capsofungin for the treatment of funguria has not been established firmly.14,17 Flucytosine has a limited role in the treatment of funguria, but it is very useful in the treatment of non-C. albicans species, which are increasing in frequency and often are resistant to fluconazole.6,14

Amphotericin B bladder irrigation no longer is recognized as a first-line treatment for candiduria, although some investigators still support its use, particularly in special circumstances.15 With the ready availability of an oral agent, IV amphotericin B is not commonly utilized for the treatment of asymptomatic funguria. However, either IV amphotericin B or IV fluconazole are options for the treatment of renal candidiasis.3,7 Unfortunately, the recurrence of funguria after the completion of an appropriate course of antifungal therapy commonly occurs.3,6,8,14,15

Back to the Case

The patient’s initial blood and sputum cultures grew Streptococcus pneumoniae, which was adequately covered by the initial treatments of piperacillin/tazobactam and levofloxacin at the time of admission. Although the patient’s clinical condition improved gradually, she required ICU management throughout her hospital stay. Due to her poor mobility, an indwelling urinary catheter was inserted. The placement of this catheter, along with her age, sex, current antibiotic therapy, and debility, all increased her likelihood of developing funguria.

It is noteworthy that the patient had no suprapubic tenderness, and she had been afebrile for the preceeding 48 hours.

The finding of funguria in this patient should not create undue concern. The true source of her acute illness (Streptococcus pneumoniae) was identified. In this instance, there would be no expected benefit from the initiation of antifungal therapy. Instead, removal of the indwelling urinary drainage device would be advisable.

Bottom Line

Asymptomatic funguria is a common clinical finding, one in which further workups or the administration of antifungal therapy is not necessary in most cases. Symptomatic funguria always requires treatment. TH

Dr. Clarke is a clinical instructor in the section of hospital medicine at Emory University Medical Center in Atlanta. Dr. Razavi is an assistant professor in the section of hospital medicine at Emory.

References

- Colodner R, Nuri Y, Chazan B, Raz R. Community-acquired and hospital-acquired candiduria: comparison of prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:301-305.

- Blot S, Dimopoulos G, Rello J, Vogelaers D. Is Candida really a threat in the ICU? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:600-604.

- Kauffman, CA. Candiduria. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:S371-376.

- Goetz LL, Howard M, Cipher D, Revankar SG. Occurrence of candiduria in a population of chronically catheterized patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;doi:10.1038/SC.2009.81.

- Safdar N, Slattery WR, Knasinski V, et al. Predictors and outcomes of candiduria in renal transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1413-1421.

- Hollenbach E. To treat or not to treat—critically ill patients with candiduria. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl2):12-24.

- Lundstrom T, Sobel J. Nosocomial candiduria: a review. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1602-1607.

- Sobel JD, Kauffman CA, McKinsey D, et al. Candiduria: A randomized, double-blind study of treatment with Fluconazole and placebo. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:19-24.

- Chen SC, Tong ZS, Lee OC, et al. Clinician response to Candida organisms in the urine of patients attending hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2008;27:201-208.

- Kauffman CA, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, et al. Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:14-18.

- Gubbins PO, McConnell SA, Penzak SR. Current management of funguria. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56(19):1929-1935.

- Drew RH, Arthur RR, Perfect JR. Is it time to abandon the use of amphotericin B bladder irrigation? Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:1465-1470.

- Bromberg WD. How do UTIs due to Candida differ from other infections? Cortlandt Forum. 1998;11(2):210.

- Bukhary ZA. Candiduria: a review of clinical significance and management. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transplant. 2008;19(3):350-360.

- Tuon FF, Amato VS, Filho SR. Bladder irrigation with amphotericin B and fungal urinary tract infection—systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J infect Dis. 2009;13(6):701-706.

- Simpson C, Blitz S, Shafran SD. The effect of current management on morbidity and mortality in hospitalized adults with funguria. J Infect. 2004;49(3):248-252.

- JD, Bradshaw SK, Lipka CJ, Kartsonis NA. Capsofungin in the treatment of symptomatic candiduria. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e46.

Case

A previously healthy 74-year-old female was admitted to the ICU nine days ago for treatment of severe streptococcal pneumonia. Her initial urine culture, which was collected on hospital day one, showed no growth; however, Candida albicans was isolated from a urine culture collected seven days later. Her second urinalysis revealed mild pyuria. What is the appropriate evaluation and treatment of funguria?

Background

Funguria is a relatively common clinical finding, and it is considerably more prevalent in patients with severe illnesses compared with healthy individuals. One study found that 2.2% of healthy, community-dwelling patients have Candida species (spp) in their urine.1 Candida spp are opportunistic organisms, which is implied by the fact that they can be isolated from 22% of patients admitted to an ICU.2

Despite the frequent isolation of Candida spp from urine cultures, the clinical significance is often unclear. It is difficult to determine if the funguria is caused by contamination, colonization, or a true urinary tract infection (UTI)—there is no test to reliably differentiate between these three possibilities. This is in contrast to bacterial UTIs, in which the findings of pyuria, bacteriuria, and a defined number of colony-forming units strongly support this diagnosis.3

Since it often is difficult to determine the true importance of funguria, its treatment has been controversial.3 The presence of a chronically indwelling urinary catheter often results in the funguria development, and, in many instances, simply removing the catheter will lead to its resolution.4 Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that for most patients with asymptomatic funguria, treatment with antifungal therapy has no effect on morbidity or mortality.5,6 Also, the propensity for funguria recurrence after completion of a course of antifungal therapy often discourages clinicians from ordering pharmacologic therapy.7,8

Review of the Data

The prevalence of funguria is increasing worldwide, primarily due to the increased use of antibiotics and immunosuppressive therapy, as well as the more frequent utilization of invasive procedures.1,7 Candida spp cause as many as 30% of all nosocomial UTIs, and they are most commonly isolated from patients who require ICU treatment.9 In fact, in one large study, only 10.9% of 861 patients with funguria had no underlying illnesses.10

Common risk factors for funguria development include the use of urinary tract drainage devices, hyperalimentation, steroids, recent antibiotic therapy, diabetes mellitus, increased age, urinary tract abnormalities, female sex, malignancy, and a previous surgical procedure.1,2,3,7,10,11,12,13,14

By far, the most common cause of funguria is Candida spp. C. albicans is responsible for at least 50% of all cases of funguria.1,10 Other yeasts that cause funguria include C. glabrata (15.6%), C. tropicalis (7.9%), C. parapsilosis (4.1%), and C. krusei (1%).10

C. glabrata most often is isolated from individuals who have been treated with fluconazole, while C. parapsilos is seen most frequently in neonates. It is noteworthy that for approximately 10% of patients with candiduria, at least two types of Candida spp are isolated from the same urine culture.6,7,14 Other types of fungi that are infrequently isolated from the urine include Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Fusarium, Trichosporon, and such dimorphic fungi as Histoplasma capsulatum and Coccidioides immitis.6 The latter organisms tend to cause funguria in individuals who have a disseminated fungal infection.

Although funguria is a relatively common finding in some patient populations, there is uncertainty about its importance. This is because funguria might be present for one of several reasons, and differentiating colonization from true infection is difficult. Unfortunately, there are no established criteria that reliably differentiate the two entities.3 Most patients with funguria have no symptoms suggestive of a UTI (e.g., dysuria, suprapubic tenderness, or hematuria).1,6,7,10

For bacterial UTIs, the presence of pyuria, and a defined minimum number of colony-forming units (CFUs), is helpful in establishing this diagnosis.1,2,3,6 However, with funguria, neither of these parameters is helpful in distinguishing between colonization, contamination, or a true UTI. The reason is that pyuria commonly develops as a result of either coexistent bacteriuria or local irritation caused by the presence of an indwelling urinary catheter.1,7 Large numbers of fungal CFUs might indicate colonization only, which has no clinical significance.6,14