User login

Award Demonstrates HM Job Satisfaction

Hospitalists can buck the tide of physician dissatisfaction in this era of reimbursement uncertainties, productivity pressures, and regulatory burdens.

Here’s fresh evidence: One of the larger HM groups in the U.S.—IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc.—recently was named one of the "Best Places to Work in Healthcare" by Modern Healthcare. The 2009 rankings were based on employee perceptions of work environment, role satisfaction, leadership and planning, culture and communications, pay and benefits, and other variables.

“Infrastructure support is key to our physicians’ satisfaction,” says IPC founder, chairman, and CEO Adam Singer, MD. A virtual office enables IPC physicians to consult with more than 1,000 colleagues serving close to 500 facilities in 19 states. Extensive business training also helps IPC physicians become proficient in coding and billing, leading meetings, speaking the language of hospital administration, and other business-savvy topics, Dr. Singer says.

Professional respect and autonomy are other chief drivers of satisfaction, according to Douglas W. Carlson, MD, FHM, SHM Career Satisfaction Task Force member. "While compensation is certainly a factor, more important is the recognition hospitalists now receive from colleagues in other specialties who see them as real go-to leaders and experts in hospital-based care," says Dr. Carlson, who is director of the division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at St. Louis Children's Hospital. Also key, he adds, is the move to shift schedules with more balanced workloads that allow hospitalists to stay intellectually stimulated.

Hospitalists can buck the tide of physician dissatisfaction in this era of reimbursement uncertainties, productivity pressures, and regulatory burdens.

Here’s fresh evidence: One of the larger HM groups in the U.S.—IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc.—recently was named one of the "Best Places to Work in Healthcare" by Modern Healthcare. The 2009 rankings were based on employee perceptions of work environment, role satisfaction, leadership and planning, culture and communications, pay and benefits, and other variables.

“Infrastructure support is key to our physicians’ satisfaction,” says IPC founder, chairman, and CEO Adam Singer, MD. A virtual office enables IPC physicians to consult with more than 1,000 colleagues serving close to 500 facilities in 19 states. Extensive business training also helps IPC physicians become proficient in coding and billing, leading meetings, speaking the language of hospital administration, and other business-savvy topics, Dr. Singer says.

Professional respect and autonomy are other chief drivers of satisfaction, according to Douglas W. Carlson, MD, FHM, SHM Career Satisfaction Task Force member. "While compensation is certainly a factor, more important is the recognition hospitalists now receive from colleagues in other specialties who see them as real go-to leaders and experts in hospital-based care," says Dr. Carlson, who is director of the division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at St. Louis Children's Hospital. Also key, he adds, is the move to shift schedules with more balanced workloads that allow hospitalists to stay intellectually stimulated.

Hospitalists can buck the tide of physician dissatisfaction in this era of reimbursement uncertainties, productivity pressures, and regulatory burdens.

Here’s fresh evidence: One of the larger HM groups in the U.S.—IPC: The Hospitalist Company Inc.—recently was named one of the "Best Places to Work in Healthcare" by Modern Healthcare. The 2009 rankings were based on employee perceptions of work environment, role satisfaction, leadership and planning, culture and communications, pay and benefits, and other variables.

“Infrastructure support is key to our physicians’ satisfaction,” says IPC founder, chairman, and CEO Adam Singer, MD. A virtual office enables IPC physicians to consult with more than 1,000 colleagues serving close to 500 facilities in 19 states. Extensive business training also helps IPC physicians become proficient in coding and billing, leading meetings, speaking the language of hospital administration, and other business-savvy topics, Dr. Singer says.

Professional respect and autonomy are other chief drivers of satisfaction, according to Douglas W. Carlson, MD, FHM, SHM Career Satisfaction Task Force member. "While compensation is certainly a factor, more important is the recognition hospitalists now receive from colleagues in other specialties who see them as real go-to leaders and experts in hospital-based care," says Dr. Carlson, who is director of the division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine at St. Louis Children's Hospital. Also key, he adds, is the move to shift schedules with more balanced workloads that allow hospitalists to stay intellectually stimulated.

Dabigatran comparable to warfarin for acute VTE

NEW ORLEANS—The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate is a safe, effective anticoagulant that, unlike warfarin, does not require routine monitoring or dose adjustments, according a presentation at 2009 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the past 20 years, research has intensified to find a competitor to warfarin, said Sam Schulman, MD, of McMaster University in Ontario, Canada.

Ximelagatran had been approved in Europe and other countries for the prevention of venous thromboembolis (VTE), but it was withdrawn in 2006 due to the induction of liver problems.

Dabigatran, like ximelagatran, slows down thrombin, Dr Schulman said.

“Dabigatran is an oral drug with quick onset; it works within 1 to 2 hours,” he explained. “There are few interactions of dabigatran with other drugs, and there is no metabolism in the liver. It can be delivered in a fixed dose that does not require monitoring and should make life easier for patients.”

The drug has been approved in Europe and Canada for the prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients and has been studied in atrial fibrillation.

Dr Schulman led the RE-COVER trial, a randomized, double-blind, trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin in 2539 patients with acute VTE.

Patients were first treated with low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin for 5 to 11 days. They then received dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily in a fixed dose (n=1274) or warfarin dose-adjusted to an International Normalized Ratio of 2.0 and 3.0 (n=1265). Patients received treatment for 6 months.

The patient characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups, Dr Shulman said. The patients had a mean age of 55 years and were predominantly Caucasian. There were slightly more men than women. One quarter of the patients had had a previous VTE.

Both groups showed similar treatment improvements. At 6 months, 30 patients (2.4%) taking dabigatran and 27 patients (2.1%) taking warfarin developed new blood clots.

“This is well below the predetermined margin for non-inferiority of dabigatran,” Dr Shulman said.

Subgroup analyses showed dabigatran was just as effective as warfarin.

Safety data showed that 20 patients (1.6%) on dabigatran and 24 patients (1.9%) on warfarin developed major bleeding. There was 1 fatal bleeding episode in each group. In the dabigatran arm, 207 patients experienced any bleeding, compared to 280 patients in the warfarin arm.

Dabigatran also led to a 37% reduction in the risk of clinically relevant bleeding, Dr Shulman said.

There was no difference between the two groups in other major side effects, including myocardial infarction and abnormal liver function tests.

“Dabigatran shows comparable efficacy to warfarin,” Dr Shulman said. “It is as safe as warfarin in terms of bleeding rates. Dabigatran provides a more convenient, fixed-dose treatment for acute VTE with the potential to replace warfarin.”

He added that parallel studies in acute VTE are planned to test dabigatran in a population that includes more Asians. Two studies of extended therapy are planned, one to compare dabigatran to placebo and the other to compare it to warfarin. ![]()

NEW ORLEANS—The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate is a safe, effective anticoagulant that, unlike warfarin, does not require routine monitoring or dose adjustments, according a presentation at 2009 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the past 20 years, research has intensified to find a competitor to warfarin, said Sam Schulman, MD, of McMaster University in Ontario, Canada.

Ximelagatran had been approved in Europe and other countries for the prevention of venous thromboembolis (VTE), but it was withdrawn in 2006 due to the induction of liver problems.

Dabigatran, like ximelagatran, slows down thrombin, Dr Schulman said.

“Dabigatran is an oral drug with quick onset; it works within 1 to 2 hours,” he explained. “There are few interactions of dabigatran with other drugs, and there is no metabolism in the liver. It can be delivered in a fixed dose that does not require monitoring and should make life easier for patients.”

The drug has been approved in Europe and Canada for the prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients and has been studied in atrial fibrillation.

Dr Schulman led the RE-COVER trial, a randomized, double-blind, trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin in 2539 patients with acute VTE.

Patients were first treated with low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin for 5 to 11 days. They then received dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily in a fixed dose (n=1274) or warfarin dose-adjusted to an International Normalized Ratio of 2.0 and 3.0 (n=1265). Patients received treatment for 6 months.

The patient characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups, Dr Shulman said. The patients had a mean age of 55 years and were predominantly Caucasian. There were slightly more men than women. One quarter of the patients had had a previous VTE.

Both groups showed similar treatment improvements. At 6 months, 30 patients (2.4%) taking dabigatran and 27 patients (2.1%) taking warfarin developed new blood clots.

“This is well below the predetermined margin for non-inferiority of dabigatran,” Dr Shulman said.

Subgroup analyses showed dabigatran was just as effective as warfarin.

Safety data showed that 20 patients (1.6%) on dabigatran and 24 patients (1.9%) on warfarin developed major bleeding. There was 1 fatal bleeding episode in each group. In the dabigatran arm, 207 patients experienced any bleeding, compared to 280 patients in the warfarin arm.

Dabigatran also led to a 37% reduction in the risk of clinically relevant bleeding, Dr Shulman said.

There was no difference between the two groups in other major side effects, including myocardial infarction and abnormal liver function tests.

“Dabigatran shows comparable efficacy to warfarin,” Dr Shulman said. “It is as safe as warfarin in terms of bleeding rates. Dabigatran provides a more convenient, fixed-dose treatment for acute VTE with the potential to replace warfarin.”

He added that parallel studies in acute VTE are planned to test dabigatran in a population that includes more Asians. Two studies of extended therapy are planned, one to compare dabigatran to placebo and the other to compare it to warfarin. ![]()

NEW ORLEANS—The direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran etexilate is a safe, effective anticoagulant that, unlike warfarin, does not require routine monitoring or dose adjustments, according a presentation at 2009 ASH Annual Meeting.

In the past 20 years, research has intensified to find a competitor to warfarin, said Sam Schulman, MD, of McMaster University in Ontario, Canada.

Ximelagatran had been approved in Europe and other countries for the prevention of venous thromboembolis (VTE), but it was withdrawn in 2006 due to the induction of liver problems.

Dabigatran, like ximelagatran, slows down thrombin, Dr Schulman said.

“Dabigatran is an oral drug with quick onset; it works within 1 to 2 hours,” he explained. “There are few interactions of dabigatran with other drugs, and there is no metabolism in the liver. It can be delivered in a fixed dose that does not require monitoring and should make life easier for patients.”

The drug has been approved in Europe and Canada for the prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients and has been studied in atrial fibrillation.

Dr Schulman led the RE-COVER trial, a randomized, double-blind, trial comparing dabigatran and warfarin in 2539 patients with acute VTE.

Patients were first treated with low-molecular-weight or unfractionated heparin for 5 to 11 days. They then received dabigatran at 150 mg twice daily in a fixed dose (n=1274) or warfarin dose-adjusted to an International Normalized Ratio of 2.0 and 3.0 (n=1265). Patients received treatment for 6 months.

The patient characteristics were well-balanced between the two groups, Dr Shulman said. The patients had a mean age of 55 years and were predominantly Caucasian. There were slightly more men than women. One quarter of the patients had had a previous VTE.

Both groups showed similar treatment improvements. At 6 months, 30 patients (2.4%) taking dabigatran and 27 patients (2.1%) taking warfarin developed new blood clots.

“This is well below the predetermined margin for non-inferiority of dabigatran,” Dr Shulman said.

Subgroup analyses showed dabigatran was just as effective as warfarin.

Safety data showed that 20 patients (1.6%) on dabigatran and 24 patients (1.9%) on warfarin developed major bleeding. There was 1 fatal bleeding episode in each group. In the dabigatran arm, 207 patients experienced any bleeding, compared to 280 patients in the warfarin arm.

Dabigatran also led to a 37% reduction in the risk of clinically relevant bleeding, Dr Shulman said.

There was no difference between the two groups in other major side effects, including myocardial infarction and abnormal liver function tests.

“Dabigatran shows comparable efficacy to warfarin,” Dr Shulman said. “It is as safe as warfarin in terms of bleeding rates. Dabigatran provides a more convenient, fixed-dose treatment for acute VTE with the potential to replace warfarin.”

He added that parallel studies in acute VTE are planned to test dabigatran in a population that includes more Asians. Two studies of extended therapy are planned, one to compare dabigatran to placebo and the other to compare it to warfarin. ![]()

Fostamatinib successfully targets the B-cell receptor

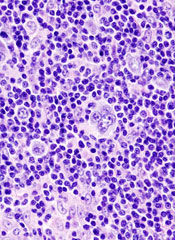

NEW YORK—Fostamatinib, a potent, specific inhibitor of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), shows promise as a targeted therapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and leukemia.

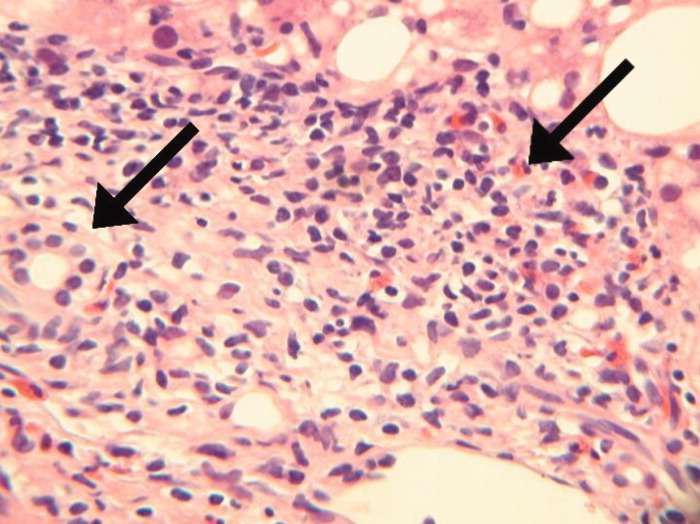

The B-cell receptor is present on both normal B cells and malignant B cells. Signaling through this receptor is necessary for B-cell maturation and survival. A subset of aggressive lymphomas, as well as follicular lymphomas, appear to rely on signaling from this receptor for survival, said Jonathan Friedberg, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Syk mediates and amplifies the B-cell receptor signal and initiates downstream events. Inhibition of Syk results in lymphoma cell death in vitro, he said.

“Syk is expressed in aggressive B-cell lines. Altered B-cell receptor signaling distinguishes follicular lymphoma cells from non-malignant B cells,” said Dr Friedberg. “Syk activity is increased in follicular lymphoma cells compared to normal cells.”

Fostamatinib is an orally available drug that has been shown to be safe in healthy human volunteers and is active in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). A study of 19 ITP patients found the drug was well tolerated and yielded a 75% response rate.

Dr Friedberg presented the results of the first phase 1/2 trial of fostamatinib in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory NHL. The phase 1 study evaluated 200 mg and 250 mg twice-daily doses of fostamatinib in 13 patients, median age 74 years. The dose-limiting toxicities were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and diarrhea. The 200 mg twice-daily dose was chosen for phase 2 testing.

The phase 2 study enrolled 68 patients with relapsed/refractory disease, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (23 patients), follicular lymphoma (21 patients), and other NHLs (24 patients). The other NHLs mainly included patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL).

The drug was well tolerated, he said. Adverse events were mainly grade 1 or 2. The most common toxicities included diarrhea, fatigue, cytopenias, nausea, and hypertension. He noted that 20% of patients developed hypertension, which was easily controlled. Five patients developed febrile neutropenia and 1 patient had pancytopenia.

Response rates were 21% for DLBCL patients, 10% for follicular lymphoma patients, 55% for CLL/SLL. Stable disease was observed in an additional 22 patients. Median progression-free survival was 4.2 months and response duration exceeded 4 months.

“Some patients had bulky lymphadenopathy that resolved completely with this agent,” said Dr Friedberg. “As the lymphocyte count increased, the lymph nodes melted away.” White blood cell counts normalized in almost all CLL patients, he noted.

The future development of the drug is likely to include rational combinations with other agents. Ongoing laboratory studies are evaluating fostamatinib with mTOR inhibitors, rituximab, proteasome inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents.

“Additional clinical trials are planned to identify lymphomas dependent upon the BCR pathway, and to confirm the exciting effects of this truly targeted therapy for B-cell lymphomas and leukemia,” he said. ![]()

NEW YORK—Fostamatinib, a potent, specific inhibitor of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), shows promise as a targeted therapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and leukemia.

The B-cell receptor is present on both normal B cells and malignant B cells. Signaling through this receptor is necessary for B-cell maturation and survival. A subset of aggressive lymphomas, as well as follicular lymphomas, appear to rely on signaling from this receptor for survival, said Jonathan Friedberg, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Syk mediates and amplifies the B-cell receptor signal and initiates downstream events. Inhibition of Syk results in lymphoma cell death in vitro, he said.

“Syk is expressed in aggressive B-cell lines. Altered B-cell receptor signaling distinguishes follicular lymphoma cells from non-malignant B cells,” said Dr Friedberg. “Syk activity is increased in follicular lymphoma cells compared to normal cells.”

Fostamatinib is an orally available drug that has been shown to be safe in healthy human volunteers and is active in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). A study of 19 ITP patients found the drug was well tolerated and yielded a 75% response rate.

Dr Friedberg presented the results of the first phase 1/2 trial of fostamatinib in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory NHL. The phase 1 study evaluated 200 mg and 250 mg twice-daily doses of fostamatinib in 13 patients, median age 74 years. The dose-limiting toxicities were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and diarrhea. The 200 mg twice-daily dose was chosen for phase 2 testing.

The phase 2 study enrolled 68 patients with relapsed/refractory disease, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (23 patients), follicular lymphoma (21 patients), and other NHLs (24 patients). The other NHLs mainly included patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL).

The drug was well tolerated, he said. Adverse events were mainly grade 1 or 2. The most common toxicities included diarrhea, fatigue, cytopenias, nausea, and hypertension. He noted that 20% of patients developed hypertension, which was easily controlled. Five patients developed febrile neutropenia and 1 patient had pancytopenia.

Response rates were 21% for DLBCL patients, 10% for follicular lymphoma patients, 55% for CLL/SLL. Stable disease was observed in an additional 22 patients. Median progression-free survival was 4.2 months and response duration exceeded 4 months.

“Some patients had bulky lymphadenopathy that resolved completely with this agent,” said Dr Friedberg. “As the lymphocyte count increased, the lymph nodes melted away.” White blood cell counts normalized in almost all CLL patients, he noted.

The future development of the drug is likely to include rational combinations with other agents. Ongoing laboratory studies are evaluating fostamatinib with mTOR inhibitors, rituximab, proteasome inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents.

“Additional clinical trials are planned to identify lymphomas dependent upon the BCR pathway, and to confirm the exciting effects of this truly targeted therapy for B-cell lymphomas and leukemia,” he said. ![]()

NEW YORK—Fostamatinib, a potent, specific inhibitor of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk), shows promise as a targeted therapy for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) and leukemia.

The B-cell receptor is present on both normal B cells and malignant B cells. Signaling through this receptor is necessary for B-cell maturation and survival. A subset of aggressive lymphomas, as well as follicular lymphomas, appear to rely on signaling from this receptor for survival, said Jonathan Friedberg, MD, of the University of Rochester in New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Syk mediates and amplifies the B-cell receptor signal and initiates downstream events. Inhibition of Syk results in lymphoma cell death in vitro, he said.

“Syk is expressed in aggressive B-cell lines. Altered B-cell receptor signaling distinguishes follicular lymphoma cells from non-malignant B cells,” said Dr Friedberg. “Syk activity is increased in follicular lymphoma cells compared to normal cells.”

Fostamatinib is an orally available drug that has been shown to be safe in healthy human volunteers and is active in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). A study of 19 ITP patients found the drug was well tolerated and yielded a 75% response rate.

Dr Friedberg presented the results of the first phase 1/2 trial of fostamatinib in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory NHL. The phase 1 study evaluated 200 mg and 250 mg twice-daily doses of fostamatinib in 13 patients, median age 74 years. The dose-limiting toxicities were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and diarrhea. The 200 mg twice-daily dose was chosen for phase 2 testing.

The phase 2 study enrolled 68 patients with relapsed/refractory disease, including diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (23 patients), follicular lymphoma (21 patients), and other NHLs (24 patients). The other NHLs mainly included patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and small lymphocytic lymphoma (SLL).

The drug was well tolerated, he said. Adverse events were mainly grade 1 or 2. The most common toxicities included diarrhea, fatigue, cytopenias, nausea, and hypertension. He noted that 20% of patients developed hypertension, which was easily controlled. Five patients developed febrile neutropenia and 1 patient had pancytopenia.

Response rates were 21% for DLBCL patients, 10% for follicular lymphoma patients, 55% for CLL/SLL. Stable disease was observed in an additional 22 patients. Median progression-free survival was 4.2 months and response duration exceeded 4 months.

“Some patients had bulky lymphadenopathy that resolved completely with this agent,” said Dr Friedberg. “As the lymphocyte count increased, the lymph nodes melted away.” White blood cell counts normalized in almost all CLL patients, he noted.

The future development of the drug is likely to include rational combinations with other agents. Ongoing laboratory studies are evaluating fostamatinib with mTOR inhibitors, rituximab, proteasome inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents.

“Additional clinical trials are planned to identify lymphomas dependent upon the BCR pathway, and to confirm the exciting effects of this truly targeted therapy for B-cell lymphomas and leukemia,” he said. ![]()

Patient Knowledge of Hospital Medication

Inpatient medication errors represent an important patient safety issue. The magnitude of the problem is staggering, with 1 review finding almost 1 in every 5 medication doses in error, with 7% having potential for adverse drug events.1 While mistakes made at the ordering stage are frequently intercepted by pharmacist or nursing review, administration errors are particularly difficult to prevent.2 The patient, as the last link in the medication administration chain, represents the final individual capable of preventing an incorrect medication administration. It is perhaps surprising then that patients generally lack a formal role in detecting and preventing adverse medication administration events.3

There have been some ambitious attempts to improve patient education regarding hospital medications and involve selected patients in the medication administration process. Such initiatives may result in increased patient participation and satisfaction.47 There is also potential that increased patient knowledge of their hospital medications could promote the goal of medication safety, as the actively involved patient may be able to catch medication errors in the hospital.

Knowledge of prescribed medications is a prerequisite to patient involvement in prevention of inpatient medication errors and yet there is little research on patient knowledge of their hospital medications. Furthermore, as the experience of hospitalization may be disorienting and disempowering for patients, it remains to be seen if patient attitudes toward participation in inpatient medication safety are favorable. To that end, we conducted a pilot study in which we assessed current patient awareness of their in‐hospital medications and surveyed attitudes toward increased patient knowledge of hospital medications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a cross‐sectional study of 50 cognitively intact adult internal medicine inpatients at the University of Colorado Hospital, a tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital. This study was part of a larger project designed to examine potential for patient involvement in the medication reconciliation process. A professional research assistant approached eligible patients within 24 hours of admission. To be eligible, patients had to self‐identify as knowing their outpatient medications, speak English, and have been admitted from the community. Nursing home residents and patients with a past medical history of dementia were excluded. Enrollment was tracked during the first half of the study to estimate effect of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thirty‐eight percent of hospital admissions to medicine services were excluded based on the specified criteria. Thirty‐four percent of eligible patients were approached and 50% of approached patients agreed to participate in the study. Patient knowledge of their outpatient medication regimen was compared to admitting physician medication reconciliation to assess accuracy of patient self‐report of outpatient medication knowledge.

After consenting to participate, study patients completed a structured list of their outpatient medications and a survey of attitudes about being shown their in‐hospital medications, hospital medication errors, and patient involvement in hospital safety. They then completed a list of the medications they believed to be prescribed to them in the hospital.

The primary outcomes were the proportions of as needed (PRN), scheduled, and total hospital medications omitted by the patient, compared to the inpatient medication administration record (MAR) (patient errors of omission). Secondary outcomes included the number of in‐hospital medications listed by the patient that did not appear on the inpatient MAR (patient errors of commission), as well as patient attitudes measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 indicated strongly disagree and 5 indicated strongly agree.) Descriptive data included age, race, gender, and number of inpatient medications prescribed. Separate analysis of variance (ANOVA) models provided mean estimates of the primary outcomes and tested differences according to each of the patient characteristics: age in years (65 or 65), self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications, and self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety. Similar ANOVA models adjusted for number of medications were also examined to determine whether the relationship between the primary outcomes according to patient characteristics were altered by the number of medications. The protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Participants averaged 54 years of age (standard deviation [SD] = 17, range = 21‐89). Forty‐six percent (23/50) were male, and 74% (37/50) were non‐Hispanic white. Using a structured, patient‐completed, outpatient medication list, patients in the study were on an average of 5.3 outpatient prescription medications (range = 0‐17), 2.2 over‐the‐counter medications (range = 0‐8), and 0.2 herbal medications (range = 0‐7). The admitting physician's medication reconciliation list demonstrated similar number of outpatient prescription medications (average = 5.7) to the patient‐generated list. Fifty‐four percent of patient‐completed home medication lists included all of the prescription medications on the physician's medication reconciliation at admission. According to the inpatient MAR, study patients were prescribed an average of 11.3 scheduled and PRN hospital medications (range = 2‐26) at time of study enrollment.

Patient Knowledge of Their Hospital Medication List

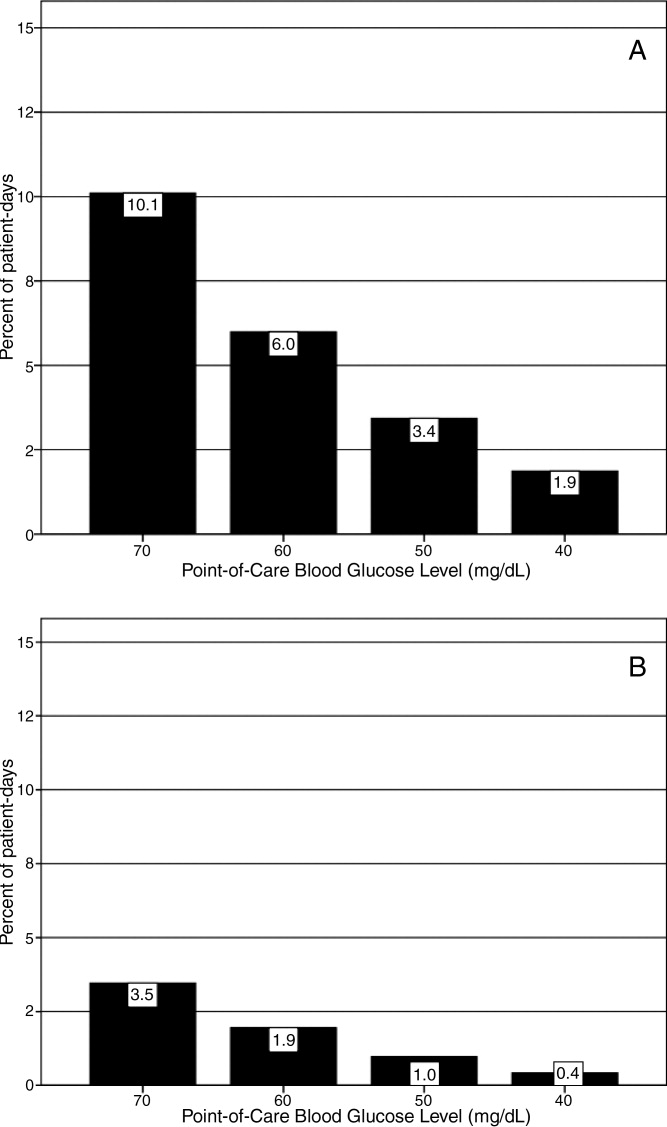

Ninety‐six percent (48/50) of study patients omitted 1 or more of their hospital medications. On average, patients omitted 6.8 medications (range = 0‐22) (Table 1). Among scheduled medications, patients most commonly omitted antibiotics (17%), cardiovascular medications (16%), and antithrombotics (15%) (Figure 1). Among PRN medications, patients most commonly omitted analgesics (33%) and gastrointestinal medications (29%) (Figure 2).

| Total Medications | Scheduled Medications | PRN Medications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients with at least 1 hospital medication they could not name (95% CI) | 96% (90‐100%) | 94% (87‐100%) | 80% (69‐92%) |

| Average number of hospital medications omitted by patient (range) | 6.8 (0‐22) | 5.2 (0‐15) | 1.6 (0‐7) |

| Percentage of hospital medications omitted by patient (95% CI) | 60% (52‐67%) | 60% (52‐67%) | 68% (57‐78%) |

Patients less than 65 years omitted 60% of their PRN medications whereas patients greater than 65 years omitted 88% (P = 0.01). This difference remained even after adjustment for number of medications. There were no significant differences, based on age, in ability to name scheduled or total medications. Forty‐four percent of patients (22/50) believed they were receiving a medication in the hospital that was not actually prescribed.

Patient Attitudes Toward Increased Knowledge of Hospital Medications

Only 28% (14/50) of patients reported having seen their hospital medication list, although 78% (39/50) favored being given such a list, and 81% (39/48) reported that this would improve their satisfaction with care. Ninety percent (45/50) wanted to review their hospital medication list for accuracy and 94% (47/50) felt patient participation in reviewing hospital medications had potential to reduce errors. No associations were found between self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications or self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety and the proportion of PRN, scheduled, or total medications omitted.

DISCUSSION

Overall, patients in the study were able to name fewer than one‐half of their hospital medications. Our study suggests that adult medicine inpatients believe learning about their hospital medications would increase their satisfaction and has potential to promote medication safety. At the same time, patients did not know many of their hospital medications and this would limit their ability to fully participate in the medication safety process. Study patients frequently committed both errors of omission (ie, they did not know which medications were prescribed), and errors of commission (ie, they believed they were prescribed medications that were not prescribed). Younger patients were aware of more of their PRN medications than older patients, potentially reflecting greater patient care involvement in younger generations. However, study patients, regardless of age, were able to name fewer than one‐half of their PRN hospital medications. The most common scheduled hospital medications that patients were unable to name come from medication classes which can be associated with significant adverse events, including antibiotics, cardiovascular medications, and antithrombotics.

We posit that without systematically educating patients about their hospital medications, significant deficits in patient knowledge are inevitable. Some might argue that patients should not be asked to know their hospital medications or identify medication errors while sick and vulnerable. Certainly with multiple medication changes, formulary substitutions, and frequent modifications based on changes in clinical status, inpatient medication education could be time consuming and potentially introduce patient confusion or anxiety. Incorrect patient feedback could have potential to introduce new errors. An educational program might use graded participation based on patient interest and ability. Models for this exist in the literature, even extending to patient medication self‐administration.57 In our sample of inpatients, the majority desired a more active role in learning about their hospital medications and believed that their involvement might prevent hospital medication errors from occurring.

Medication literacy, education, and active patient involvement in medication monitoring as a means to improve patient outcomes has received significant attention in the outpatient setting, with lessons applicable to the hospital.8, 9 More broadly, the Joint Commission has established a Hospital National Patient Safety Goal to encourage patients' active involvement in their own care as a patient safety strategy.10 Examples set forth by the Joint Commission include involving patients in infection control measures, marking of procedural sites, and reporting of safety concerns relating to treatment.

While this study identifies patient knowledge deficit as a barrier to utilizing patients as part of the hospital medication safety process, it does not test whether reducing this knowledge deficit would actually reduce medication error. Our study population was limited to cognitively intact adult medicine patients at a single institution, limiting the generalizability of our conclusions. Our enrollment process may have resulted in a study population with less serious illness, greater knowledge of their hospital medications, and greater interest in participating in medication safety potentially overestimating patient knowledge of hospital medications. Finally, our small sample size limits the power to find differences in study comparisons.

Our findings are striking in that we found significant deficits in patient understanding of their hospital medications even among patients who believed they knew, or desired to know, what is being prescribed to them in the hospital. Without a system to incorporate the patient into hospital medication management, these patients will be disenfranchised from participating in inpatient medication safety. These results are a call to reexamine how we educate and involve patients regarding hospital medications. Mechanisms to allow patients to provide feedback to the medical team on their hospital medications might identify errors or improve patient satisfaction with their care. However, the systems and cultural changes needed to provide education on inpatient medications are considerable. Future research is needed to determine if increasing patient knowledge regarding their hospital medications would reduce medication errors in the inpatient setting and how this could be effectively implemented.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sue Felton, MA, Professional Research Assistant, for enrolling patients in this trial, and Traci Yamashita, MS, Professional Research Assistant, for statistical analysis.

- ,,,,.Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1897–1903.

- ,,, et al.Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group.JAMA.1995;274:29–34.

- ,.Patient Safety: what about the patient?Qual Saf Health Care.2002;11:76–80.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacist involvement in a multidisciplinary inpatient medication education program.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2003;60:1012–1018.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication by patients and family members during hospitalization.Patient Educ Couns.1996;27:103–112.

- ,,,.Hospital inpatient self‐administration of medicine programmes: a critical literature review.Pharm World Sci.2006;28:140–151.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication in hospital: patients' perspectives.J Adv Nurs.2004;46:194–203.

- ,.Outpatient drug safety: new steps in an old direction.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2007;16:160–165.

- ,,.Impact of health literacy on health outcomes in ambulatory care patients: a systematic review.Phamacosociology.2008;42:1272–1281.

- Joint Commission.2009. Standards Improvement Initiative. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/31666E86‐E7F4–423E‐9BE8‐F05BD1CB0AA8/0/HAP_NPSG.pdf. Accessed June 2009.

Inpatient medication errors represent an important patient safety issue. The magnitude of the problem is staggering, with 1 review finding almost 1 in every 5 medication doses in error, with 7% having potential for adverse drug events.1 While mistakes made at the ordering stage are frequently intercepted by pharmacist or nursing review, administration errors are particularly difficult to prevent.2 The patient, as the last link in the medication administration chain, represents the final individual capable of preventing an incorrect medication administration. It is perhaps surprising then that patients generally lack a formal role in detecting and preventing adverse medication administration events.3

There have been some ambitious attempts to improve patient education regarding hospital medications and involve selected patients in the medication administration process. Such initiatives may result in increased patient participation and satisfaction.47 There is also potential that increased patient knowledge of their hospital medications could promote the goal of medication safety, as the actively involved patient may be able to catch medication errors in the hospital.

Knowledge of prescribed medications is a prerequisite to patient involvement in prevention of inpatient medication errors and yet there is little research on patient knowledge of their hospital medications. Furthermore, as the experience of hospitalization may be disorienting and disempowering for patients, it remains to be seen if patient attitudes toward participation in inpatient medication safety are favorable. To that end, we conducted a pilot study in which we assessed current patient awareness of their in‐hospital medications and surveyed attitudes toward increased patient knowledge of hospital medications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a cross‐sectional study of 50 cognitively intact adult internal medicine inpatients at the University of Colorado Hospital, a tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital. This study was part of a larger project designed to examine potential for patient involvement in the medication reconciliation process. A professional research assistant approached eligible patients within 24 hours of admission. To be eligible, patients had to self‐identify as knowing their outpatient medications, speak English, and have been admitted from the community. Nursing home residents and patients with a past medical history of dementia were excluded. Enrollment was tracked during the first half of the study to estimate effect of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thirty‐eight percent of hospital admissions to medicine services were excluded based on the specified criteria. Thirty‐four percent of eligible patients were approached and 50% of approached patients agreed to participate in the study. Patient knowledge of their outpatient medication regimen was compared to admitting physician medication reconciliation to assess accuracy of patient self‐report of outpatient medication knowledge.

After consenting to participate, study patients completed a structured list of their outpatient medications and a survey of attitudes about being shown their in‐hospital medications, hospital medication errors, and patient involvement in hospital safety. They then completed a list of the medications they believed to be prescribed to them in the hospital.

The primary outcomes were the proportions of as needed (PRN), scheduled, and total hospital medications omitted by the patient, compared to the inpatient medication administration record (MAR) (patient errors of omission). Secondary outcomes included the number of in‐hospital medications listed by the patient that did not appear on the inpatient MAR (patient errors of commission), as well as patient attitudes measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 indicated strongly disagree and 5 indicated strongly agree.) Descriptive data included age, race, gender, and number of inpatient medications prescribed. Separate analysis of variance (ANOVA) models provided mean estimates of the primary outcomes and tested differences according to each of the patient characteristics: age in years (65 or 65), self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications, and self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety. Similar ANOVA models adjusted for number of medications were also examined to determine whether the relationship between the primary outcomes according to patient characteristics were altered by the number of medications. The protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Participants averaged 54 years of age (standard deviation [SD] = 17, range = 21‐89). Forty‐six percent (23/50) were male, and 74% (37/50) were non‐Hispanic white. Using a structured, patient‐completed, outpatient medication list, patients in the study were on an average of 5.3 outpatient prescription medications (range = 0‐17), 2.2 over‐the‐counter medications (range = 0‐8), and 0.2 herbal medications (range = 0‐7). The admitting physician's medication reconciliation list demonstrated similar number of outpatient prescription medications (average = 5.7) to the patient‐generated list. Fifty‐four percent of patient‐completed home medication lists included all of the prescription medications on the physician's medication reconciliation at admission. According to the inpatient MAR, study patients were prescribed an average of 11.3 scheduled and PRN hospital medications (range = 2‐26) at time of study enrollment.

Patient Knowledge of Their Hospital Medication List

Ninety‐six percent (48/50) of study patients omitted 1 or more of their hospital medications. On average, patients omitted 6.8 medications (range = 0‐22) (Table 1). Among scheduled medications, patients most commonly omitted antibiotics (17%), cardiovascular medications (16%), and antithrombotics (15%) (Figure 1). Among PRN medications, patients most commonly omitted analgesics (33%) and gastrointestinal medications (29%) (Figure 2).

| Total Medications | Scheduled Medications | PRN Medications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients with at least 1 hospital medication they could not name (95% CI) | 96% (90‐100%) | 94% (87‐100%) | 80% (69‐92%) |

| Average number of hospital medications omitted by patient (range) | 6.8 (0‐22) | 5.2 (0‐15) | 1.6 (0‐7) |

| Percentage of hospital medications omitted by patient (95% CI) | 60% (52‐67%) | 60% (52‐67%) | 68% (57‐78%) |

Patients less than 65 years omitted 60% of their PRN medications whereas patients greater than 65 years omitted 88% (P = 0.01). This difference remained even after adjustment for number of medications. There were no significant differences, based on age, in ability to name scheduled or total medications. Forty‐four percent of patients (22/50) believed they were receiving a medication in the hospital that was not actually prescribed.

Patient Attitudes Toward Increased Knowledge of Hospital Medications

Only 28% (14/50) of patients reported having seen their hospital medication list, although 78% (39/50) favored being given such a list, and 81% (39/48) reported that this would improve their satisfaction with care. Ninety percent (45/50) wanted to review their hospital medication list for accuracy and 94% (47/50) felt patient participation in reviewing hospital medications had potential to reduce errors. No associations were found between self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications or self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety and the proportion of PRN, scheduled, or total medications omitted.

DISCUSSION

Overall, patients in the study were able to name fewer than one‐half of their hospital medications. Our study suggests that adult medicine inpatients believe learning about their hospital medications would increase their satisfaction and has potential to promote medication safety. At the same time, patients did not know many of their hospital medications and this would limit their ability to fully participate in the medication safety process. Study patients frequently committed both errors of omission (ie, they did not know which medications were prescribed), and errors of commission (ie, they believed they were prescribed medications that were not prescribed). Younger patients were aware of more of their PRN medications than older patients, potentially reflecting greater patient care involvement in younger generations. However, study patients, regardless of age, were able to name fewer than one‐half of their PRN hospital medications. The most common scheduled hospital medications that patients were unable to name come from medication classes which can be associated with significant adverse events, including antibiotics, cardiovascular medications, and antithrombotics.

We posit that without systematically educating patients about their hospital medications, significant deficits in patient knowledge are inevitable. Some might argue that patients should not be asked to know their hospital medications or identify medication errors while sick and vulnerable. Certainly with multiple medication changes, formulary substitutions, and frequent modifications based on changes in clinical status, inpatient medication education could be time consuming and potentially introduce patient confusion or anxiety. Incorrect patient feedback could have potential to introduce new errors. An educational program might use graded participation based on patient interest and ability. Models for this exist in the literature, even extending to patient medication self‐administration.57 In our sample of inpatients, the majority desired a more active role in learning about their hospital medications and believed that their involvement might prevent hospital medication errors from occurring.

Medication literacy, education, and active patient involvement in medication monitoring as a means to improve patient outcomes has received significant attention in the outpatient setting, with lessons applicable to the hospital.8, 9 More broadly, the Joint Commission has established a Hospital National Patient Safety Goal to encourage patients' active involvement in their own care as a patient safety strategy.10 Examples set forth by the Joint Commission include involving patients in infection control measures, marking of procedural sites, and reporting of safety concerns relating to treatment.

While this study identifies patient knowledge deficit as a barrier to utilizing patients as part of the hospital medication safety process, it does not test whether reducing this knowledge deficit would actually reduce medication error. Our study population was limited to cognitively intact adult medicine patients at a single institution, limiting the generalizability of our conclusions. Our enrollment process may have resulted in a study population with less serious illness, greater knowledge of their hospital medications, and greater interest in participating in medication safety potentially overestimating patient knowledge of hospital medications. Finally, our small sample size limits the power to find differences in study comparisons.

Our findings are striking in that we found significant deficits in patient understanding of their hospital medications even among patients who believed they knew, or desired to know, what is being prescribed to them in the hospital. Without a system to incorporate the patient into hospital medication management, these patients will be disenfranchised from participating in inpatient medication safety. These results are a call to reexamine how we educate and involve patients regarding hospital medications. Mechanisms to allow patients to provide feedback to the medical team on their hospital medications might identify errors or improve patient satisfaction with their care. However, the systems and cultural changes needed to provide education on inpatient medications are considerable. Future research is needed to determine if increasing patient knowledge regarding their hospital medications would reduce medication errors in the inpatient setting and how this could be effectively implemented.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sue Felton, MA, Professional Research Assistant, for enrolling patients in this trial, and Traci Yamashita, MS, Professional Research Assistant, for statistical analysis.

Inpatient medication errors represent an important patient safety issue. The magnitude of the problem is staggering, with 1 review finding almost 1 in every 5 medication doses in error, with 7% having potential for adverse drug events.1 While mistakes made at the ordering stage are frequently intercepted by pharmacist or nursing review, administration errors are particularly difficult to prevent.2 The patient, as the last link in the medication administration chain, represents the final individual capable of preventing an incorrect medication administration. It is perhaps surprising then that patients generally lack a formal role in detecting and preventing adverse medication administration events.3

There have been some ambitious attempts to improve patient education regarding hospital medications and involve selected patients in the medication administration process. Such initiatives may result in increased patient participation and satisfaction.47 There is also potential that increased patient knowledge of their hospital medications could promote the goal of medication safety, as the actively involved patient may be able to catch medication errors in the hospital.

Knowledge of prescribed medications is a prerequisite to patient involvement in prevention of inpatient medication errors and yet there is little research on patient knowledge of their hospital medications. Furthermore, as the experience of hospitalization may be disorienting and disempowering for patients, it remains to be seen if patient attitudes toward participation in inpatient medication safety are favorable. To that end, we conducted a pilot study in which we assessed current patient awareness of their in‐hospital medications and surveyed attitudes toward increased patient knowledge of hospital medications.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We conducted a cross‐sectional study of 50 cognitively intact adult internal medicine inpatients at the University of Colorado Hospital, a tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital. This study was part of a larger project designed to examine potential for patient involvement in the medication reconciliation process. A professional research assistant approached eligible patients within 24 hours of admission. To be eligible, patients had to self‐identify as knowing their outpatient medications, speak English, and have been admitted from the community. Nursing home residents and patients with a past medical history of dementia were excluded. Enrollment was tracked during the first half of the study to estimate effect of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Thirty‐eight percent of hospital admissions to medicine services were excluded based on the specified criteria. Thirty‐four percent of eligible patients were approached and 50% of approached patients agreed to participate in the study. Patient knowledge of their outpatient medication regimen was compared to admitting physician medication reconciliation to assess accuracy of patient self‐report of outpatient medication knowledge.

After consenting to participate, study patients completed a structured list of their outpatient medications and a survey of attitudes about being shown their in‐hospital medications, hospital medication errors, and patient involvement in hospital safety. They then completed a list of the medications they believed to be prescribed to them in the hospital.

The primary outcomes were the proportions of as needed (PRN), scheduled, and total hospital medications omitted by the patient, compared to the inpatient medication administration record (MAR) (patient errors of omission). Secondary outcomes included the number of in‐hospital medications listed by the patient that did not appear on the inpatient MAR (patient errors of commission), as well as patient attitudes measured on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 indicated strongly disagree and 5 indicated strongly agree.) Descriptive data included age, race, gender, and number of inpatient medications prescribed. Separate analysis of variance (ANOVA) models provided mean estimates of the primary outcomes and tested differences according to each of the patient characteristics: age in years (65 or 65), self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications, and self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety. Similar ANOVA models adjusted for number of medications were also examined to determine whether the relationship between the primary outcomes according to patient characteristics were altered by the number of medications. The protocol was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Participants averaged 54 years of age (standard deviation [SD] = 17, range = 21‐89). Forty‐six percent (23/50) were male, and 74% (37/50) were non‐Hispanic white. Using a structured, patient‐completed, outpatient medication list, patients in the study were on an average of 5.3 outpatient prescription medications (range = 0‐17), 2.2 over‐the‐counter medications (range = 0‐8), and 0.2 herbal medications (range = 0‐7). The admitting physician's medication reconciliation list demonstrated similar number of outpatient prescription medications (average = 5.7) to the patient‐generated list. Fifty‐four percent of patient‐completed home medication lists included all of the prescription medications on the physician's medication reconciliation at admission. According to the inpatient MAR, study patients were prescribed an average of 11.3 scheduled and PRN hospital medications (range = 2‐26) at time of study enrollment.

Patient Knowledge of Their Hospital Medication List

Ninety‐six percent (48/50) of study patients omitted 1 or more of their hospital medications. On average, patients omitted 6.8 medications (range = 0‐22) (Table 1). Among scheduled medications, patients most commonly omitted antibiotics (17%), cardiovascular medications (16%), and antithrombotics (15%) (Figure 1). Among PRN medications, patients most commonly omitted analgesics (33%) and gastrointestinal medications (29%) (Figure 2).

| Total Medications | Scheduled Medications | PRN Medications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients with at least 1 hospital medication they could not name (95% CI) | 96% (90‐100%) | 94% (87‐100%) | 80% (69‐92%) |

| Average number of hospital medications omitted by patient (range) | 6.8 (0‐22) | 5.2 (0‐15) | 1.6 (0‐7) |

| Percentage of hospital medications omitted by patient (95% CI) | 60% (52‐67%) | 60% (52‐67%) | 68% (57‐78%) |

Patients less than 65 years omitted 60% of their PRN medications whereas patients greater than 65 years omitted 88% (P = 0.01). This difference remained even after adjustment for number of medications. There were no significant differences, based on age, in ability to name scheduled or total medications. Forty‐four percent of patients (22/50) believed they were receiving a medication in the hospital that was not actually prescribed.

Patient Attitudes Toward Increased Knowledge of Hospital Medications

Only 28% (14/50) of patients reported having seen their hospital medication list, although 78% (39/50) favored being given such a list, and 81% (39/48) reported that this would improve their satisfaction with care. Ninety percent (45/50) wanted to review their hospital medication list for accuracy and 94% (47/50) felt patient participation in reviewing hospital medications had potential to reduce errors. No associations were found between self‐reported knowledge of hospital medications or self‐reported desire to be involved in medication safety and the proportion of PRN, scheduled, or total medications omitted.

DISCUSSION

Overall, patients in the study were able to name fewer than one‐half of their hospital medications. Our study suggests that adult medicine inpatients believe learning about their hospital medications would increase their satisfaction and has potential to promote medication safety. At the same time, patients did not know many of their hospital medications and this would limit their ability to fully participate in the medication safety process. Study patients frequently committed both errors of omission (ie, they did not know which medications were prescribed), and errors of commission (ie, they believed they were prescribed medications that were not prescribed). Younger patients were aware of more of their PRN medications than older patients, potentially reflecting greater patient care involvement in younger generations. However, study patients, regardless of age, were able to name fewer than one‐half of their PRN hospital medications. The most common scheduled hospital medications that patients were unable to name come from medication classes which can be associated with significant adverse events, including antibiotics, cardiovascular medications, and antithrombotics.

We posit that without systematically educating patients about their hospital medications, significant deficits in patient knowledge are inevitable. Some might argue that patients should not be asked to know their hospital medications or identify medication errors while sick and vulnerable. Certainly with multiple medication changes, formulary substitutions, and frequent modifications based on changes in clinical status, inpatient medication education could be time consuming and potentially introduce patient confusion or anxiety. Incorrect patient feedback could have potential to introduce new errors. An educational program might use graded participation based on patient interest and ability. Models for this exist in the literature, even extending to patient medication self‐administration.57 In our sample of inpatients, the majority desired a more active role in learning about their hospital medications and believed that their involvement might prevent hospital medication errors from occurring.

Medication literacy, education, and active patient involvement in medication monitoring as a means to improve patient outcomes has received significant attention in the outpatient setting, with lessons applicable to the hospital.8, 9 More broadly, the Joint Commission has established a Hospital National Patient Safety Goal to encourage patients' active involvement in their own care as a patient safety strategy.10 Examples set forth by the Joint Commission include involving patients in infection control measures, marking of procedural sites, and reporting of safety concerns relating to treatment.

While this study identifies patient knowledge deficit as a barrier to utilizing patients as part of the hospital medication safety process, it does not test whether reducing this knowledge deficit would actually reduce medication error. Our study population was limited to cognitively intact adult medicine patients at a single institution, limiting the generalizability of our conclusions. Our enrollment process may have resulted in a study population with less serious illness, greater knowledge of their hospital medications, and greater interest in participating in medication safety potentially overestimating patient knowledge of hospital medications. Finally, our small sample size limits the power to find differences in study comparisons.

Our findings are striking in that we found significant deficits in patient understanding of their hospital medications even among patients who believed they knew, or desired to know, what is being prescribed to them in the hospital. Without a system to incorporate the patient into hospital medication management, these patients will be disenfranchised from participating in inpatient medication safety. These results are a call to reexamine how we educate and involve patients regarding hospital medications. Mechanisms to allow patients to provide feedback to the medical team on their hospital medications might identify errors or improve patient satisfaction with their care. However, the systems and cultural changes needed to provide education on inpatient medications are considerable. Future research is needed to determine if increasing patient knowledge regarding their hospital medications would reduce medication errors in the inpatient setting and how this could be effectively implemented.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sue Felton, MA, Professional Research Assistant, for enrolling patients in this trial, and Traci Yamashita, MS, Professional Research Assistant, for statistical analysis.

- ,,,,.Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1897–1903.

- ,,, et al.Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group.JAMA.1995;274:29–34.

- ,.Patient Safety: what about the patient?Qual Saf Health Care.2002;11:76–80.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacist involvement in a multidisciplinary inpatient medication education program.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2003;60:1012–1018.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication by patients and family members during hospitalization.Patient Educ Couns.1996;27:103–112.

- ,,,.Hospital inpatient self‐administration of medicine programmes: a critical literature review.Pharm World Sci.2006;28:140–151.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication in hospital: patients' perspectives.J Adv Nurs.2004;46:194–203.

- ,.Outpatient drug safety: new steps in an old direction.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2007;16:160–165.

- ,,.Impact of health literacy on health outcomes in ambulatory care patients: a systematic review.Phamacosociology.2008;42:1272–1281.

- Joint Commission.2009. Standards Improvement Initiative. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/31666E86‐E7F4–423E‐9BE8‐F05BD1CB0AA8/0/HAP_NPSG.pdf. Accessed June 2009.

- ,,,,.Medication errors observed in 36 health care facilities.Arch Intern Med.2002;162:1897–1903.

- ,,, et al.Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group.JAMA.1995;274:29–34.

- ,.Patient Safety: what about the patient?Qual Saf Health Care.2002;11:76–80.

- ,,, et al.Pharmacist involvement in a multidisciplinary inpatient medication education program.Am J Health Syst Pharm.2003;60:1012–1018.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication by patients and family members during hospitalization.Patient Educ Couns.1996;27:103–112.

- ,,,.Hospital inpatient self‐administration of medicine programmes: a critical literature review.Pharm World Sci.2006;28:140–151.

- ,,,.Self‐administration of medication in hospital: patients' perspectives.J Adv Nurs.2004;46:194–203.

- ,.Outpatient drug safety: new steps in an old direction.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf.2007;16:160–165.

- ,,.Impact of health literacy on health outcomes in ambulatory care patients: a systematic review.Phamacosociology.2008;42:1272–1281.

- Joint Commission.2009. Standards Improvement Initiative. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/31666E86‐E7F4–423E‐9BE8‐F05BD1CB0AA8/0/HAP_NPSG.pdf. Accessed June 2009.

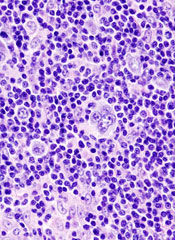

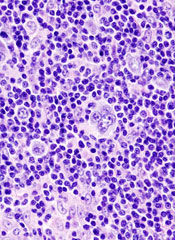

Panobinostat shows promise in refractory Hodgkin lymphoma

New York, NY —Growing evidence suggests that the potent pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589) shows promising clinical activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Panobinostat targets both epigenetic and non-epigenetic oncogenic pathways and is among a group of novel antineoplastic agents that inhibit the activity of histone deacetylases, said Myron Czuczman, MD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Panobinostat is currently under clinical investigation in a variety of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Promising results in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma were presented earlier in the year at the European Hematology Association annual meeting in Berlin, Germany.

Dr Czuczman updated those results from the phase 1/2 trial of Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with a variety of advanced hematologic malignancies who were refractory to treatments. One group of patients had leukemias or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and another group had lymphoma or myeloma.

The patients received 2 schedules of oral panobinostat: once-a-day on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (MWF) every week or MWF every other week. PET and CT data were evaluated for best response.

So far, 61 patients in the lymphoma and myeloma group have been treated, and 53 patients have been evaluated. The investigators have recorded 1 complete response, 10 partial responses, and 31 patients with stable disease. Of the 31 patients with stable disease, 25 patients had a decrease in tumor burden, and additional responses are likely in this group, said Dr Czuczman.

For patients in the lymphoma or myeloma group, “about three-quarters of the patients had some evidence of antitumor activity,” said Dr Czuczman.

He noted that this group has had a range of prior therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. The median number of prior chemotherapeutic regimens was 5. “These patients had limited treatment options,” he said.

Safety analysis reveals that the most common grade 3/4 adverse events with panobinostat therapy have been thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, fatigue, and anemia. The maximum tolerated dose for patients in this group is 40 mg MWF every week or 60 mg MWF every other week. “More than 60% of the patients have had dose reductions, mostly due to cytopenia, which is not surprising given their limited bone marrow reserve,” he said.

Dr Czuczman said that panobinostat was well tolerated and induced antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients. “The drug has a role in the treatment of patients with treatment-refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma and possibly in earlier stages of the disease as well,” he said.

Further updates of this ongoing study will follow, and a global phase 2 study is currently underway using panobinostat at 40 mg/day on MWF every week in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

In addition, Dr Czuczman has started a phase 1 study in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients using panobinostat in an intrapatient dose modification program that allows patients to escalate or deescalate doses depending on their tolerance of the drug.![]()

New York, NY —Growing evidence suggests that the potent pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589) shows promising clinical activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Panobinostat targets both epigenetic and non-epigenetic oncogenic pathways and is among a group of novel antineoplastic agents that inhibit the activity of histone deacetylases, said Myron Czuczman, MD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Panobinostat is currently under clinical investigation in a variety of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Promising results in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma were presented earlier in the year at the European Hematology Association annual meeting in Berlin, Germany.

Dr Czuczman updated those results from the phase 1/2 trial of Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with a variety of advanced hematologic malignancies who were refractory to treatments. One group of patients had leukemias or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and another group had lymphoma or myeloma.

The patients received 2 schedules of oral panobinostat: once-a-day on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (MWF) every week or MWF every other week. PET and CT data were evaluated for best response.

So far, 61 patients in the lymphoma and myeloma group have been treated, and 53 patients have been evaluated. The investigators have recorded 1 complete response, 10 partial responses, and 31 patients with stable disease. Of the 31 patients with stable disease, 25 patients had a decrease in tumor burden, and additional responses are likely in this group, said Dr Czuczman.

For patients in the lymphoma or myeloma group, “about three-quarters of the patients had some evidence of antitumor activity,” said Dr Czuczman.

He noted that this group has had a range of prior therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. The median number of prior chemotherapeutic regimens was 5. “These patients had limited treatment options,” he said.

Safety analysis reveals that the most common grade 3/4 adverse events with panobinostat therapy have been thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, fatigue, and anemia. The maximum tolerated dose for patients in this group is 40 mg MWF every week or 60 mg MWF every other week. “More than 60% of the patients have had dose reductions, mostly due to cytopenia, which is not surprising given their limited bone marrow reserve,” he said.

Dr Czuczman said that panobinostat was well tolerated and induced antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients. “The drug has a role in the treatment of patients with treatment-refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma and possibly in earlier stages of the disease as well,” he said.

Further updates of this ongoing study will follow, and a global phase 2 study is currently underway using panobinostat at 40 mg/day on MWF every week in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

In addition, Dr Czuczman has started a phase 1 study in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients using panobinostat in an intrapatient dose modification program that allows patients to escalate or deescalate doses depending on their tolerance of the drug.![]()

New York, NY —Growing evidence suggests that the potent pan-deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat (LBH589) shows promising clinical activity in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Panobinostat targets both epigenetic and non-epigenetic oncogenic pathways and is among a group of novel antineoplastic agents that inhibit the activity of histone deacetylases, said Myron Czuczman, MD, of Roswell Park Cancer Institute in Buffalo, New York, at the Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium held November 10-13, 2009.

Panobinostat is currently under clinical investigation in a variety of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Promising results in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma were presented earlier in the year at the European Hematology Association annual meeting in Berlin, Germany.

Dr Czuczman updated those results from the phase 1/2 trial of Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients with a variety of advanced hematologic malignancies who were refractory to treatments. One group of patients had leukemias or high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes and another group had lymphoma or myeloma.

The patients received 2 schedules of oral panobinostat: once-a-day on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday (MWF) every week or MWF every other week. PET and CT data were evaluated for best response.

So far, 61 patients in the lymphoma and myeloma group have been treated, and 53 patients have been evaluated. The investigators have recorded 1 complete response, 10 partial responses, and 31 patients with stable disease. Of the 31 patients with stable disease, 25 patients had a decrease in tumor burden, and additional responses are likely in this group, said Dr Czuczman.

For patients in the lymphoma or myeloma group, “about three-quarters of the patients had some evidence of antitumor activity,” said Dr Czuczman.

He noted that this group has had a range of prior therapies, including surgery, radiotherapy, stem cell transplantation, and cytotoxic chemotherapy. The median number of prior chemotherapeutic regimens was 5. “These patients had limited treatment options,” he said.

Safety analysis reveals that the most common grade 3/4 adverse events with panobinostat therapy have been thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, fatigue, and anemia. The maximum tolerated dose for patients in this group is 40 mg MWF every week or 60 mg MWF every other week. “More than 60% of the patients have had dose reductions, mostly due to cytopenia, which is not surprising given their limited bone marrow reserve,” he said.

Dr Czuczman said that panobinostat was well tolerated and induced antitumor activity in heavily pretreated patients. “The drug has a role in the treatment of patients with treatment-refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma and possibly in earlier stages of the disease as well,” he said.

Further updates of this ongoing study will follow, and a global phase 2 study is currently underway using panobinostat at 40 mg/day on MWF every week in patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

In addition, Dr Czuczman has started a phase 1 study in relapsed/refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients using panobinostat in an intrapatient dose modification program that allows patients to escalate or deescalate doses depending on their tolerance of the drug.![]()

Quality Reporting Incentive Payments Surge

A Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) report that shows a nearly 300% increase in bonus payments under Medicare's Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) is further evidence that hospitalists are embracing pay-for-reporting measures, according to the chair of SHM's Performance and Standards Committee.

Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., says increased usage of pay incentives to push quality reform is "past that tipping point, but what's really unknown right now is what's going to happen with the healthcare reform in front of us right now."

"It's an evolution for physicians to accept that pay for performance, starting with pay for reporting, is here to stay," Dr. Torcson says. "It's really a matter of the practice management that's necessary to include performance reporting as part of the workflow of how you take care of patients and report your billing claims."

In 2008, CMS paid $92 million in bonuses under the PQRI program, an increase from $36 million in 2007. However, the program was only active for the second half of 2007, so Dr. Torcson cautions against reading too much into the increase. Still, CMS reported that payments were distributed to more than 85,500 physicians with an average payment of $1,000. In Dr. Torcson's 10-hospitalist group, the average bonus was $1,400. He predicts an average 2009 payment of $2,400 for members of his group.

Dr. Torcson expects more hospitalists will use the incentive program once more HM-specific performance measures are put in place, including yardsticks focused on care transitions and inpatient management of heart failure.

"This truly is the platform for the future pay-for-performance model that's going to affect every hospitalist," he adds. "I can't see any reason to ignore it.”

For more information about reporting PQRI measures, visit the CMS Web site and check out the PQRI toolkit. Visit SHM's Web site for information about getting your hospitalist program started in Medicare's voluntary pay-for-reporting program.

A Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) report that shows a nearly 300% increase in bonus payments under Medicare's Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) is further evidence that hospitalists are embracing pay-for-reporting measures, according to the chair of SHM's Performance and Standards Committee.

Patrick Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., says increased usage of pay incentives to push quality reform is "past that tipping point, but what's really unknown right now is what's going to happen with the healthcare reform in front of us right now."

"It's an evolution for physicians to accept that pay for performance, starting with pay for reporting, is here to stay," Dr. Torcson says. "It's really a matter of the practice management that's necessary to include performance reporting as part of the workflow of how you take care of patients and report your billing claims."