User login

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Audio interview with Lee H. Schwamm, MD

Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital are the Boston-based hubs for the Partners TeleStroke Network. The system connects 27 participating hospitals across three states with an escalating chain of access to stroke resources. Spoke hospitals transmit, through a secure link, such clinical data as noncontrast head CT scans to the hub, where a stroke expert “examines” the patient via live video feed and shares in the responsibility for deciding whether to initiate t-PA.

Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital are the Boston-based hubs for the Partners TeleStroke Network. The system connects 27 participating hospitals across three states with an escalating chain of access to stroke resources. Spoke hospitals transmit, through a secure link, such clinical data as noncontrast head CT scans to the hub, where a stroke expert “examines” the patient via live video feed and shares in the responsibility for deciding whether to initiate t-PA.

Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital are the Boston-based hubs for the Partners TeleStroke Network. The system connects 27 participating hospitals across three states with an escalating chain of access to stroke resources. Spoke hospitals transmit, through a secure link, such clinical data as noncontrast head CT scans to the hub, where a stroke expert “examines” the patient via live video feed and shares in the responsibility for deciding whether to initiate t-PA.

The Role of Incretin-Based Therapies in Treating Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Supplement Editor:

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Contents

Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus: New therapeutic mechanisms

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Current antihyperglycemic treatment strategies for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Lawrence Blonde, MD

Role of the incretin pathway in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Jeffrey S. Freeman, DO

Patient and treatment perspectives: Revisiting the link between type 2 diabetes, weight gain, and cardiovascular risk

Anne L. Peters, MD, CDE

Advances in therapy for type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors

Jaime A. Davidson, MD

Redefining treatment success in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Comprehensive targeting of core defects

William T. Cefalu, MD; Robert J. Richards, MD; and Lydia Y. Melendez-Ramirez, MD

Supplement Editor:

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Contents

Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus: New therapeutic mechanisms

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Current antihyperglycemic treatment strategies for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Lawrence Blonde, MD

Role of the incretin pathway in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Jeffrey S. Freeman, DO

Patient and treatment perspectives: Revisiting the link between type 2 diabetes, weight gain, and cardiovascular risk

Anne L. Peters, MD, CDE

Advances in therapy for type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors

Jaime A. Davidson, MD

Redefining treatment success in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Comprehensive targeting of core defects

William T. Cefalu, MD; Robert J. Richards, MD; and Lydia Y. Melendez-Ramirez, MD

Supplement Editor:

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Contents

Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus: New therapeutic mechanisms

Laurence Kennedy, MD

Current antihyperglycemic treatment strategies for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Lawrence Blonde, MD

Role of the incretin pathway in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus

Jeffrey S. Freeman, DO

Patient and treatment perspectives: Revisiting the link between type 2 diabetes, weight gain, and cardiovascular risk

Anne L. Peters, MD, CDE

Advances in therapy for type 2 diabetes: GLP-1 receptor agonists and DPP-4 inhibitors

Jaime A. Davidson, MD

Redefining treatment success in type 2 diabetes mellitus: Comprehensive targeting of core defects

William T. Cefalu, MD; Robert J. Richards, MD; and Lydia Y. Melendez-Ramirez, MD

Incretin-based therapies for type 2 diabetes mellitus: New therapeutic mechanisms

Almost a decade into the 21st century, the global epidemic of diabetes—which accelerated in the 1970s—shows no sign of slowing. At the same time, our insights into both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have increased at a similarly rapid rate.

At the beginning of the 1970s, it was far from clear whether improved glycemic control made much difference in the long-term well-being of people with diabetes other than to relieve their symptoms of hyperglycemia and decrease the likelihood of diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma. Concerns were expressed about the risk/benefit ratio of antihyperglycemic drugs—so there is nothing new under the sun! The drugs available in the United States were limited to insulin and sulfonylureas. The rest of the world also had access to metformin, but, in truth, its potential was underestimated until much later.

RECOGNIZING THE VALUE OF GLYCEMIC CONTROL

Out of this milieu of scientific uncertainty grew the two clinical trials that effectively ended the debate about the value of glycemic control: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)1 for type 1 diabetes, and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)2,3 for T2DM. The conduct of these trials was facilitated by the timely demonstration of the utility of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as an objective measure of glycemic control, and of microalbuminuria as a marker of early nephropathy.

Both the DCCT and the UKPDS, in their initial “end of study” analyses in the 1990s, established the role of glycemic control in reducing the risk of retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy—the microvascular complications of diabetes. Additionally, the UKPDS demonstrated that in T2DM, hypertension management was at least as important as glycemic control in reducing the risk of microvascular complications.

Neither the DCCT nor the UKPDS was powered to determine initially whether glycemic control was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease; however, careful longer-term surveillance of the patient cohorts in the studies has recently borne fruit in this regard. Reports from both studies have shown that efforts to control glycemia early in the course of diabetes are rewarded many years later by a decreased risk of cardiovascular events and death.4,5 This is true even when excellent glycemic control achieved early on is not sustained indefinitely. It has also become widely recognized that the management of diabetes, with prevention of microvascular and cardiovascular disease as major aims, involves much more than a simple preoccupation with glycemic control—important as that is.

NEW TREATMENT OPTIONS

Concurrent with the DCCT and the UKPDS being conducted with, in effect, the therapeutic tools of the 1970s, considerable strides were being made in the development of new classes of antihyperglycemic agents for use in T2DM. These include the thiazolidinediones (TZDs), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, nonsulfonylurea insulin secretagogues (also known as glinides), and, more recently, the incretin-based drugs that are the focus of this supplement to the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Understandable enthusiasm for tapping into the hitherto unexploited pathways and mechanisms targeted by a new drug class is inevitably tempered by known, or sometimes unforeseen, adverse effects. Some of the adverse effects typically associated with antihyperglycemic drugs used before the incretin-based therapies became available include hypoglycemia, weight gain, and fluid retention; all of these are perceived as possibly increasing the risk of the very thing we are striving to avoid in diabetes—cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Such is the concern about this risk—epitomized, rightly or wrongly, in the controversial meta-analysis of clinical trials involving rosiglitazone6—that the US Food and Drug Administration now requires new antihyperglycemic drugs not only to meet efficacy standards for improving glycemia but also to show no sign of increased cardiovascular risk. The requirement must be met in preapproval trials, to be followed by postmarketing studies to prove the lack of cardiovascular risk.

As the contributions in this supplement point out, incretin-based therapies generally are either weight neutral or promote weight loss; by their modes of action, they are unlikely to cause hypoglycemia; and, as shown thus far, they are unassociated with fluid retention or increased likelihood of heart failure. Continued vigilance regarding cardiovascular risk will be important for the new incretin-based therapies, however.

BETA-CELL FUNCTION STILL A CHALLENGE

Another aspect of T2DM highlighted by the UKPDS is the degree of pancreatic beta-cell function loss—typically about 50% or more—at the time of clinical diagnosis, and the steady decline in function thereafter.7 This, as much as the understandable fatigue with lifestyle modification that normal humans experience, accounts for the frequent failure of oral antihyperglycemic monotherapy or dual therapy to maintain satisfactory glycemic control over the years. Relieving hyperglycemia at the time of diagnosis by any means usually leads to a temporary improvement in beta-cell function, but the possibility of slowing or even reversing the long-term decline has been an elusive therapeutic goal.

Although direct quantitative assessment of beta-cell function in humans is difficult in routine practice or outside of strict research protocols, a randomized study comparing different monotherapies for T2DM showed that over several years, the rise in HbA1c was more gradual with rosiglitazone than with glyburide or metformin; this suggests that, at least compared with metformin and sulfonylureas, the TZDs may have some longer-term benefit with respect to beta-cell function.8

That incretin-based treatments may help preserve or improve beta-cell function has been suggested by animal data.9 Proving that that is the case in humans will be much more challenging. A recent randomized study in patients with T2DM already taking metformin showed that addition of exenatide for 1 year resulted in improved beta-cell function, assessed by C-peptide responses to glucose and to arginine during a combined euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic clamp procedure. The improvement was evident compared with baseline function and with patients randomized to receive insulin glargine in addition to metformin for a year.10 However, 4 weeks after exenatide and glargine were discontinued, the beta-cell function had reverted to the pretreatment level and was not significantly different in the two groups of patients. Moreover, 3 months after treatment discontinuation, the HbA1c levels, which had decreased during the year to a similar extent in both groups, had returned to pretreatment levels. The investigators acknowledged that it was impossible in their study to “discriminate between acute and long-term effects of exenatide on beta-cell function.”10 So, in my opinion, the challenge remains to show that meaningful long-term effects on beta-cell function can be achieved with incretin-based therapy.

That said, there is no doubt that the incretin-based therapies bring a new dimension to our ability to treat diabetes. The articles in this supplement will provide both the specialist and nonspecialist with a better understanding of these relatively new therapies.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998; 352:854–865.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457–2471.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UK prospective diabetes study 16: overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. Diabetes 1995; 44:1249–1258.

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2427–2443.

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2131–2157.

- Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetes patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:762–768.

Almost a decade into the 21st century, the global epidemic of diabetes—which accelerated in the 1970s—shows no sign of slowing. At the same time, our insights into both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have increased at a similarly rapid rate.

At the beginning of the 1970s, it was far from clear whether improved glycemic control made much difference in the long-term well-being of people with diabetes other than to relieve their symptoms of hyperglycemia and decrease the likelihood of diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma. Concerns were expressed about the risk/benefit ratio of antihyperglycemic drugs—so there is nothing new under the sun! The drugs available in the United States were limited to insulin and sulfonylureas. The rest of the world also had access to metformin, but, in truth, its potential was underestimated until much later.

RECOGNIZING THE VALUE OF GLYCEMIC CONTROL

Out of this milieu of scientific uncertainty grew the two clinical trials that effectively ended the debate about the value of glycemic control: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)1 for type 1 diabetes, and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)2,3 for T2DM. The conduct of these trials was facilitated by the timely demonstration of the utility of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as an objective measure of glycemic control, and of microalbuminuria as a marker of early nephropathy.

Both the DCCT and the UKPDS, in their initial “end of study” analyses in the 1990s, established the role of glycemic control in reducing the risk of retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy—the microvascular complications of diabetes. Additionally, the UKPDS demonstrated that in T2DM, hypertension management was at least as important as glycemic control in reducing the risk of microvascular complications.

Neither the DCCT nor the UKPDS was powered to determine initially whether glycemic control was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease; however, careful longer-term surveillance of the patient cohorts in the studies has recently borne fruit in this regard. Reports from both studies have shown that efforts to control glycemia early in the course of diabetes are rewarded many years later by a decreased risk of cardiovascular events and death.4,5 This is true even when excellent glycemic control achieved early on is not sustained indefinitely. It has also become widely recognized that the management of diabetes, with prevention of microvascular and cardiovascular disease as major aims, involves much more than a simple preoccupation with glycemic control—important as that is.

NEW TREATMENT OPTIONS

Concurrent with the DCCT and the UKPDS being conducted with, in effect, the therapeutic tools of the 1970s, considerable strides were being made in the development of new classes of antihyperglycemic agents for use in T2DM. These include the thiazolidinediones (TZDs), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, nonsulfonylurea insulin secretagogues (also known as glinides), and, more recently, the incretin-based drugs that are the focus of this supplement to the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Understandable enthusiasm for tapping into the hitherto unexploited pathways and mechanisms targeted by a new drug class is inevitably tempered by known, or sometimes unforeseen, adverse effects. Some of the adverse effects typically associated with antihyperglycemic drugs used before the incretin-based therapies became available include hypoglycemia, weight gain, and fluid retention; all of these are perceived as possibly increasing the risk of the very thing we are striving to avoid in diabetes—cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Such is the concern about this risk—epitomized, rightly or wrongly, in the controversial meta-analysis of clinical trials involving rosiglitazone6—that the US Food and Drug Administration now requires new antihyperglycemic drugs not only to meet efficacy standards for improving glycemia but also to show no sign of increased cardiovascular risk. The requirement must be met in preapproval trials, to be followed by postmarketing studies to prove the lack of cardiovascular risk.

As the contributions in this supplement point out, incretin-based therapies generally are either weight neutral or promote weight loss; by their modes of action, they are unlikely to cause hypoglycemia; and, as shown thus far, they are unassociated with fluid retention or increased likelihood of heart failure. Continued vigilance regarding cardiovascular risk will be important for the new incretin-based therapies, however.

BETA-CELL FUNCTION STILL A CHALLENGE

Another aspect of T2DM highlighted by the UKPDS is the degree of pancreatic beta-cell function loss—typically about 50% or more—at the time of clinical diagnosis, and the steady decline in function thereafter.7 This, as much as the understandable fatigue with lifestyle modification that normal humans experience, accounts for the frequent failure of oral antihyperglycemic monotherapy or dual therapy to maintain satisfactory glycemic control over the years. Relieving hyperglycemia at the time of diagnosis by any means usually leads to a temporary improvement in beta-cell function, but the possibility of slowing or even reversing the long-term decline has been an elusive therapeutic goal.

Although direct quantitative assessment of beta-cell function in humans is difficult in routine practice or outside of strict research protocols, a randomized study comparing different monotherapies for T2DM showed that over several years, the rise in HbA1c was more gradual with rosiglitazone than with glyburide or metformin; this suggests that, at least compared with metformin and sulfonylureas, the TZDs may have some longer-term benefit with respect to beta-cell function.8

That incretin-based treatments may help preserve or improve beta-cell function has been suggested by animal data.9 Proving that that is the case in humans will be much more challenging. A recent randomized study in patients with T2DM already taking metformin showed that addition of exenatide for 1 year resulted in improved beta-cell function, assessed by C-peptide responses to glucose and to arginine during a combined euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic clamp procedure. The improvement was evident compared with baseline function and with patients randomized to receive insulin glargine in addition to metformin for a year.10 However, 4 weeks after exenatide and glargine were discontinued, the beta-cell function had reverted to the pretreatment level and was not significantly different in the two groups of patients. Moreover, 3 months after treatment discontinuation, the HbA1c levels, which had decreased during the year to a similar extent in both groups, had returned to pretreatment levels. The investigators acknowledged that it was impossible in their study to “discriminate between acute and long-term effects of exenatide on beta-cell function.”10 So, in my opinion, the challenge remains to show that meaningful long-term effects on beta-cell function can be achieved with incretin-based therapy.

That said, there is no doubt that the incretin-based therapies bring a new dimension to our ability to treat diabetes. The articles in this supplement will provide both the specialist and nonspecialist with a better understanding of these relatively new therapies.

Almost a decade into the 21st century, the global epidemic of diabetes—which accelerated in the 1970s—shows no sign of slowing. At the same time, our insights into both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have increased at a similarly rapid rate.

At the beginning of the 1970s, it was far from clear whether improved glycemic control made much difference in the long-term well-being of people with diabetes other than to relieve their symptoms of hyperglycemia and decrease the likelihood of diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperglycemic hyperosmolar nonketotic coma. Concerns were expressed about the risk/benefit ratio of antihyperglycemic drugs—so there is nothing new under the sun! The drugs available in the United States were limited to insulin and sulfonylureas. The rest of the world also had access to metformin, but, in truth, its potential was underestimated until much later.

RECOGNIZING THE VALUE OF GLYCEMIC CONTROL

Out of this milieu of scientific uncertainty grew the two clinical trials that effectively ended the debate about the value of glycemic control: the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT)1 for type 1 diabetes, and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)2,3 for T2DM. The conduct of these trials was facilitated by the timely demonstration of the utility of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) as an objective measure of glycemic control, and of microalbuminuria as a marker of early nephropathy.

Both the DCCT and the UKPDS, in their initial “end of study” analyses in the 1990s, established the role of glycemic control in reducing the risk of retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy—the microvascular complications of diabetes. Additionally, the UKPDS demonstrated that in T2DM, hypertension management was at least as important as glycemic control in reducing the risk of microvascular complications.

Neither the DCCT nor the UKPDS was powered to determine initially whether glycemic control was a risk factor for cardiovascular disease; however, careful longer-term surveillance of the patient cohorts in the studies has recently borne fruit in this regard. Reports from both studies have shown that efforts to control glycemia early in the course of diabetes are rewarded many years later by a decreased risk of cardiovascular events and death.4,5 This is true even when excellent glycemic control achieved early on is not sustained indefinitely. It has also become widely recognized that the management of diabetes, with prevention of microvascular and cardiovascular disease as major aims, involves much more than a simple preoccupation with glycemic control—important as that is.

NEW TREATMENT OPTIONS

Concurrent with the DCCT and the UKPDS being conducted with, in effect, the therapeutic tools of the 1970s, considerable strides were being made in the development of new classes of antihyperglycemic agents for use in T2DM. These include the thiazolidinediones (TZDs), alpha-glucosidase inhibitors, nonsulfonylurea insulin secretagogues (also known as glinides), and, more recently, the incretin-based drugs that are the focus of this supplement to the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Understandable enthusiasm for tapping into the hitherto unexploited pathways and mechanisms targeted by a new drug class is inevitably tempered by known, or sometimes unforeseen, adverse effects. Some of the adverse effects typically associated with antihyperglycemic drugs used before the incretin-based therapies became available include hypoglycemia, weight gain, and fluid retention; all of these are perceived as possibly increasing the risk of the very thing we are striving to avoid in diabetes—cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Such is the concern about this risk—epitomized, rightly or wrongly, in the controversial meta-analysis of clinical trials involving rosiglitazone6—that the US Food and Drug Administration now requires new antihyperglycemic drugs not only to meet efficacy standards for improving glycemia but also to show no sign of increased cardiovascular risk. The requirement must be met in preapproval trials, to be followed by postmarketing studies to prove the lack of cardiovascular risk.

As the contributions in this supplement point out, incretin-based therapies generally are either weight neutral or promote weight loss; by their modes of action, they are unlikely to cause hypoglycemia; and, as shown thus far, they are unassociated with fluid retention or increased likelihood of heart failure. Continued vigilance regarding cardiovascular risk will be important for the new incretin-based therapies, however.

BETA-CELL FUNCTION STILL A CHALLENGE

Another aspect of T2DM highlighted by the UKPDS is the degree of pancreatic beta-cell function loss—typically about 50% or more—at the time of clinical diagnosis, and the steady decline in function thereafter.7 This, as much as the understandable fatigue with lifestyle modification that normal humans experience, accounts for the frequent failure of oral antihyperglycemic monotherapy or dual therapy to maintain satisfactory glycemic control over the years. Relieving hyperglycemia at the time of diagnosis by any means usually leads to a temporary improvement in beta-cell function, but the possibility of slowing or even reversing the long-term decline has been an elusive therapeutic goal.

Although direct quantitative assessment of beta-cell function in humans is difficult in routine practice or outside of strict research protocols, a randomized study comparing different monotherapies for T2DM showed that over several years, the rise in HbA1c was more gradual with rosiglitazone than with glyburide or metformin; this suggests that, at least compared with metformin and sulfonylureas, the TZDs may have some longer-term benefit with respect to beta-cell function.8

That incretin-based treatments may help preserve or improve beta-cell function has been suggested by animal data.9 Proving that that is the case in humans will be much more challenging. A recent randomized study in patients with T2DM already taking metformin showed that addition of exenatide for 1 year resulted in improved beta-cell function, assessed by C-peptide responses to glucose and to arginine during a combined euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic clamp procedure. The improvement was evident compared with baseline function and with patients randomized to receive insulin glargine in addition to metformin for a year.10 However, 4 weeks after exenatide and glargine were discontinued, the beta-cell function had reverted to the pretreatment level and was not significantly different in the two groups of patients. Moreover, 3 months after treatment discontinuation, the HbA1c levels, which had decreased during the year to a similar extent in both groups, had returned to pretreatment levels. The investigators acknowledged that it was impossible in their study to “discriminate between acute and long-term effects of exenatide on beta-cell function.”10 So, in my opinion, the challenge remains to show that meaningful long-term effects on beta-cell function can be achieved with incretin-based therapy.

That said, there is no doubt that the incretin-based therapies bring a new dimension to our ability to treat diabetes. The articles in this supplement will provide both the specialist and nonspecialist with a better understanding of these relatively new therapies.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998; 352:854–865.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457–2471.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UK prospective diabetes study 16: overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. Diabetes 1995; 44:1249–1258.

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2427–2443.

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2131–2157.

- Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetes patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:762–768.

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:977–986.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34). Lancet 1998; 352:854–865.

- Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2643–2653.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007; 356:2457–2471.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. UK prospective diabetes study 16: overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. Diabetes 1995; 44:1249–1258.

- Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2427–2443.

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ. Biology of incretins: GLP-1 and GIP. Gastroenterology 2007; 132:2131–2157.

- Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetes patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:762–768.

Current antihyperglycemic treatment strategies for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that almost 24 million Americans, or 7.8% of the population, have diabetes; 90% to 95% of these have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Diabetes and excessive weight often coexist. An analysis of data from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that among individuals with diabetes, 85% were overweight or obese and 55% were obese.2

Gaps remain in the management of T2DM between the goals for clinical parameters of care (eg, control of glucose, blood pressure [BP], and lipids) and actual clinical practice.3 NHANES data reveal that glycemic control improved from a mean glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 7.82% in 1999–2000 to 7.18% in 2003–2004.4 Hazard models based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 10-year outcomes data in 4,320 newly diagnosed T2DM patients suggest that a sustained decrease in HbA1c of 0.511 percentage points could reduce diabetes complications by 10.7%.4,5

Additional analysis of NHANES data showed that in 2003–2004, about 57% of individuals achieved glycemic control, 48% reached BP targets, and 50% achieved target cholesterol goals.Only about 13% of diabetes patients achieved their target goals for all three parameters concurrently.6

This article reviews the association between cardiometabolic risk and the current antihyperglycemic treatments for patients with T2DM, with a focus on the role of incretin-related therapies.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CARDIOMETABOLIC RISK IN T2DM

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among people with diabetes and is the reported cause of mortality in up to 65% of deaths in persons with diabetes in the United States.7 The risk of CVD is two- to fourfold greater among adults with diabetes than among adults who do not have diabetes.8 The risk of CVD in patients with T2DM was evident in the UKPDS 17, where macrovascular complications, including CVD, were about twice as common as microvascular complications (20% vs 9%) after 9 years of follow-up.9 A study that involved more than 44,000 patients showed an almost double rate of mortality from all causes among individuals with T2DM compared with those with no diabetes (hazard ratio, 1.93; 95% confidence interval, 1.89 to 1.97).10 Current guidelines recommend aggressive management of CV risk factors, including BP control, correction of atherogenic dyslipidemia, glycemic control, weight reduction for those who are overweight or obese, and smoking cessation for those who smoke.3,11 Lifestyle interventions, including weight reduction and appropriately prescribed physical activity, result in reduced CV risk factors, which can help slow the progression of T2DM.12

GOALS OF T2DM THERAPY

Several studies have demonstrated that glycemic control can delay or prevent the development and progression of microvascular complications.13,14 UKPDS 33 showed that more intensive blood glucose control (median HbA1c 7.0%) in patients with T2DM followed over 10 years significantly (P = .029) reduced the risk for any diabetes-related end point by 12% compared with conventional therapy (median HbA1c 7.9%). Most of the risk reduction was accounted for by a 25% risk reduction in microvascular end points (P = .0099).13 Another report (UKPDS 35) demonstrated that HbA1c was strongly related to microvascular effects, with a 1% reduction in HbA1c associated with a 37% reduction in microvascular complications.14

Does intensive glucose control reduce CV risk?

To resolve the ongoing question of whether intensive glucose control can lead to a reduction in CV risk in patients with T2DM, three large, long-term trials were conducted within the last decade.15–18 Two of these, the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) and Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trials, each enrolled more than 10,000 previously treated patients with long-standing T2DM. Patients were randomized to standard or intensive glycemic control for 3.5 years in the ACCORD trial and for 5 years in the ADVANCE trial.15,16

The ACCORD and ADVANCE trials, along with the smaller Veterans Administration Diabetes Trial (VADT) (N = 1,791), failed to show that more intensive glycemic control significantly reduced CVD.15–17 Additionally, the glycemic control component of ACCORD was halted because of increased mortality in the intensive arm compared with the standard arm.15 Further analyses of ACCORD data presented at the 69th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) showed that HbA1c values lower than 7.0% did not explain the increased mortality. The 20% higher risk of death for every 1.0% increase in HbA1c greater than 6.0% suggests that glucose concentrations even lower than the general HbA1c goal of less than 7.0% may be appropriate in some patients.18 The most recent finding from VADT was that CV risk was dependent on disease duration and presence of comorbidities. Intensive therapy seemed to work best in patients with diabetes of less than 15 years’ duration, while risk of a CV event was more than doubled with intensive therapy in patients having diabetes for more than 21 years.

Clarification of treatment goals

A position statement of the ADA and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association19 concluded that the “evidence obtained from ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VADT does not suggest the need for major changes in glycemic control targets but, rather, additional clarification of the language that has consistently stressed individualization.” They state that while the general HbA1c goal of less than 7.0% seems reasonable, even lower HbA1c goals may be appropriate for some patients if they can be achieved without significant hypoglycemia or other adverse effects. Such patients might include those with diabetes of short duration, long life expectancy, or no significant CVD or hypoglycemia. Conversely, higher HbA1c goals may be appropriate for patients with limited life expectancy, a history of severe hypoglycemia, established microvascular or macrovascular complications, significant other comorbid conditions, or longstanding diabetes in whom an HbA1c of less than 7.0% has been difficult to attain despite optimal treatment and diabetes self-management education.19

Long-term risk reduction

A 10-year, postinterventional follow-up study (UKPDS 80) of the UKPDS survivor cohort was reported recently.20 Results showed that despite an early loss of glycemic differences between patients treated with diet and those treated with intensive regimens (sulfonylurea or insulin; metformin in overweight patients), the pharmacotherapy group demonstrated a prolonged reduction in microvascular risk as well as a significant reduction in the risk for myocardial infarction (15% [P = .01] in the sulfonylurea-insulin group and 33% [P = .005] in the metformin group) and death from any cause.20 This suggests that early improvement in glycemic control is associated with long-term benefits in the micro- and macrovascular health of patients with T2DM.

Additionally, the recent long-term follow-up of the Steno-2 study21 showed that a multifactorial intervention striving for intensive glucose, BP, and lipid control that included the use of renin-angiotensin system blockers, aspirin, and lipid-lowering agents not only reduced the risk of nonfatal CVD among patients with T2DM and microalbuminuria, but also had sustained beneficial effects on vascular complications and on rates of death from any cause and from CV causes. From a health care payer perspective, intensive multifactorial intervention was more likely to be cost-effective than conventional treatment in Denmark, especially if applied in a primary care setting.22

Comprehensive care needed

The lower-than-expected rates of CV outcomes in the ACCORD, ADVANCE, VADT, and Steno-2 studies reinforce the importance of comprehensive diabetes care that treats not only hyperglycemia but also elevated BP and dyslipidemia; these are considered the “ABCs” of diabetes.11,19 The 2009 ADA standards of medical care guidelines recommend that for most T2DM patients, HbA1c should be maintained at less than 7.0%,3 while the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) 2007 guidelines state that HbA1c should be 6.5% or less.11 Both organizations stress the importance of individualized goals, as discussed above, and advocate BP goals of less than 130/80 mm Hg and dyslipidemia goals of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) less than 100 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) greater than 40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women, and triglycerides less than 150 mg/dL. It is recommended that an optional LDL-C goal of less than 70 mg/dL be considered for individuals with overt CVD.

CURRENT ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC TREATMENT STRATEGIES

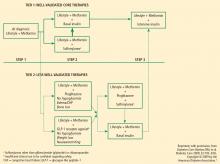

In response to new insights from clinical research and emerging treatment strategies, disease-specific organizations and medical specialty societies regularly revise and update their treatment guidelines and algorithms. These resources recommend that glycemic progress should be regularly monitored and pharmacologic therapy titrated or new drugs added promptly if glycemic goals are not met after 2 to 3 months.

Several algorithms combine scientific evidence with expert clinical opinion to guide physicians in treating their patients with T2DM. The American College of Endocrinology (ACE)/AACE road maps are designed to help develop individualized treatment regimens to achieve an HbA1c of 6.5% or less.23 The algorithm from a writing group assembled by the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) similarly promotes pharmacologic treatment together with lifestyle modifications to maintain a glycemic goal of HbA1c less than 7.0%.24

OVERVIEW OF ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC TREATMENT APPROACHES

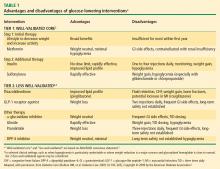

Initial oral therapy

T2DM is usually treated initially with a single oral agent. Consistent with the progressive nature of the disease, patients often eventually require one or more additional oral agents and in many cases insulin.13,27 Choice of specific agents is based on individual patient circumstances, including the need for weight loss and control of fasting versus postprandial glucose, the presence of dyslipidemia and hypertension, and the risk for and potential consequences of hypoglycemia.24 T2DM patients with severely uncontrolled and symptomatic hyperglycemia are best treated, at least initially, with a combination of insulin therapy and lifestyle intervention, often with metformin.

Metformin. The recently revised ADA/EASD writing group algorithm recommends that patients not requiring initial insulin begin treatment with metformin at the time of diagnosis unless there are contraindications.24 Metformin is not associated with hypoglycemia and is considered weight-neutral, although some patients may lose weight.28

Sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells; their use may be associated with hypoglycemia and weight gain. Mechanisms for weight gain with sulfonylureas include reduction of glucosuria and increased caloric intake to prevent or treat hypoglycemia.11,28 Nateglinide and repaglinide are nonsulfonylurea oral insulin secretagogues. They result in rapid and relatively short-lived insulin responses and are usually administered three times a day, before each meal. Their use may be associated with weight gain and hypoglycemia.11

Thiazolidinediones. Thiazolidinediones (TZD) increase insulin sensitivity in muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver. Hypoglycemia is uncommon with TZD monotherapy but weight gain related to increased and redistributed adiposity and fluid retention frequently occurs.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. The alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are administered before meals and primarily reduce postprandial hyperglycemia. They are generally weight-neutral.28

Insulin. Insulin and insulin analogues are the most effective antihyperglycemic agents, but their use can be associated with hypoglycemia and clinically significant weight gain.28

Colesevelam. Colesevelam is a bile acid sequestrant that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an antihyperglycemic therapy in people with T2DM. At a dosage of 1.875 g BID or 3.75 g QD in combination with a sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin therapy, reductions in HbA1c compared with placebo in clinical trials of colesevelam have ranged from –0.5% to –0.7% (P < .02). Frequency of hypoglycemia and weight gain is low with this agent.26

Weight management. Weight reduction is important for overweight or obese patients with T2DM.27,28 Even moderate weight loss (5% of body weight) can be associated with improved insulin action and reduced hyperglycemia.29 Conversely, weight gain has been shown to worsen hyperglycemia and other CV risk factors. Treatment-related weight gain can also lead to decreased regimen adherence, contributing to poor glycemic control.28

THE ROLE OF INCRETIN HORMONES AND INCRETIN-BASED THERAPIES IN T2DM PATIENTS

Over the last few years, the role of incretin hormones and their contribution to diabetes pathophysiology has become more apparent. The incretin effect refers to the observation that orally administered glucose elicits a greater insulin response than does glucose administered intravenously to produce equivalent blood glucose concentrations.30,31 The incretin effect is diminished in patients with T2DM.

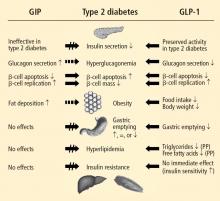

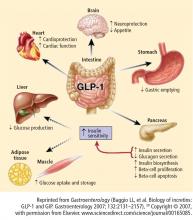

Hormone mediation of the incretin effect

The two hormones that mediate the incretin effect are GIP (also known as gastric inhibitory polypeptide or glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide) and glucagon-like peptide−1 (GLP-1).30,31 GLP-1 has several glucoregulatory actions, including enhancement of endogenous insulin release and suppression of inappropriate glucagon secretion, both in a glucose-dependent manner. Therefore, these effects of GLP-1 occur only when glucose concentrations are elevated, thereby minimizing the risk of hypoglycemia. GLP-1 also regulates gastric emptying; infusions of GLP-1 can slow the accelerated emptying that is often present in T2DM patients. GLP-1 also increases satiety and decreases food intake via a central mechanism.31

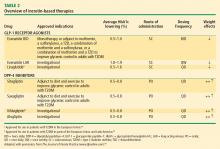

Because GLP-1 is rapidly inactivated by the enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase–4 (DPP-4), therapeutic use of GLP-1 would require continuous infusion, which is impractical.30,31 Two strategies have been used to produce incretin-related therapies. One, inhibition of the DPP-4 enzyme, results in a two- to threefold enhancement of endogenous GLP-1. The other, involving agents that resist breakdown by DPP-4 but bind to and activate the GLP-1 receptor, produces glucoregulatory effects similar to those of GLP-1.30

Following subcutaneous (SC) injection, GLP-1 receptor agonists enhance insulin secretion and suppress inappropriately elevated glucagon, both in a glucose-dependent manner, as well as slow gastric emptying and enhance satiety.30 DPP-4 inhibitors provide glucose-dependent enhanced insulin secretion and glucagon suppression, but they do not have the same effects on gastric emptying or satiety.

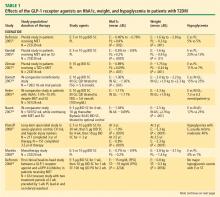

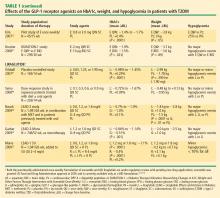

Clinically, the GLP-1 receptor agonists improve glycemia and are associated with weight loss.32–35 Adverse gastrointestinal symptoms are relatively common during the first few weeks of treatment. DPP-4 inhibitors improve glycemia but are weight-neutral and are not generally associated with significant gastrointestinal symptoms.32,36–38

Incretin-based therapies

Incretin-based therapies are currently part of the antihyperglycemic armamentarium.25,32 The AACE guidelines11 and the ACE/AACE roadmaps23 include the GLP-1 receptor agonist exenatide and the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin among antihyperglycemic therapies for patients with T2DM. The most recent update of the consensus algorithm statement of a joint ADA/EASD writing group included GLP-1 receptor agonists (but not DPP-4 inhibitors) in tier 2 of preferred agents, especially for patients who have concerns related to weight and hypoglycemia.24 They noted that DPP-4 inhibitors may be appropriate choices in selected patients.

DPP-4 inhibitors: sitagliptin, saxagliptin. Until recently, sitagliptin was the only DPP-4 inhibitor available in the United States. Sitagliptin is approved by the FDA for treatment of T2DM at a recommended oral dosage of 100 mg QD, either as monotherapy or in combination with other oral antihyperglycemic medications. The dosage of sitagliptin should be reduced to 50 mg/day in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) levels that are between 30 mL/min and 50 mL/min and to 25 mg/day in those with CrCl less than 30 mL/min.39

In a meta-analysis of incretin-based therapies, DPP-4 inhibitors produced a reduction in HbA1c compared with placebo (weighted mean difference of –0.74%; 95% confidence interval, –0.85% to –0.62%).32 DPP-4 inhibitor antihyperglycemic efficacy has been shown to be similar whether used as a monotherapy or add-on therapy.32,37,38 This same meta-analysis showed DPP-4 inhibitors as having a neutral effect on weight.32 More recently, a single-pill combination of metformin and sitagliptin was approved.40

A study comparing metformin, sitagliptin, and the combination of the two as initial monotherapy in T2DM patients with a baseline HbA1c of 8.8% showed 24-week HbA1c reductions from baseline of –0.66% with sitagliptin 100 mg QD, –0.82% with metformin 500 mg BID, and –1.90% with sitagliptin 50 mg + metformin 1,000 mg BID.41

On July 31, 2009, the FDA approved another DPP-4 inhibitor, saxagliptin, for the treatment of T2DM either as monotherapy or in combination with metformin, a sulfonylurea, or a TZD.42

GLP-1 receptor agonist: exenatide. Exenatide, the only FDA-approved GLP-1 receptor agonist, is the synthetic version of exendin-4, which binds to the human GLP-1 receptor and in vitro possesses many of the glucoregulatory effects of endogenous GLP-1.30,32 Exenatide is indicated as monotherapy or adjunctive therapy for patients with T2DM who have not achieved adequate glycemic control with metformin, a sulfonylurea, a TZD, or metformin in combination with a sulfonylurea or a TZD.43 Exenatide is administered by SC injection BID at a starting dosage of 5 mg BID for 4 weeks, followed by an increase to 10 mg BID.

Exenatide has been shown not only to enhance glucose-dependent insulin secretion but also to restore impaired first-phase insulin response in subjects with T2DM. Exenatide also helps control postprandial glycemic excursions by suppressing inappropriate glucagon secretion, slowing accelerated gastric emptying, and enhancing satiety. The increased satiety results in decreased food intake and weight loss.31,44 In a recent head-to-head crossover study, exenatide was shown to be more effective than sitagliptin in lowering postprandial glucose concentrations, increasing insulin secretion, and reducing postprandial glucagon secretion.45 Exenatide also slowed gastric emptying and reduced caloric intake.

Exenatide, in most studies, resulted in a placebo-subtracted HbA1c reduction of approximately –1.0% and in one study lowered HbA1c from baseline by –1.5%. Completer analyses have shown HbA1c reductions of –1.0% up to 3 years and –0.8% up to 3.5 years. Exenatide has also been associated with a mean weight loss of as much as –3.6 kg at 30 weeks and as much as –5.3 kg at 3.5 years.33–35,46,47 A 1-year study showed that exenatide improved beta-cell secretory function compared with insulin glargine in metformin-treated patients with T2DM.48 Long-term data, including findings from completed and intention-to-treat analyses of 82 weeks49 to at least 3 years47 have demonstrated that exenatide improved CV risk factors, including those related to BP, lipids, and hepatic injury biomarkers.

Therapies in development

Incretin-based therapies in development include a novel once-weekly formulation of exenatide; taspoglutide, another once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist; and liraglutide, a GLP-1 receptor agonist that is administered once daily.50 Liraglutide is currently being evaluated in clinical trials as a once-daily SC injection.51–53 Liraglutide has been reported to reduce HbA1c by –1.1% at 26 weeks and up to –1.14% at 52 weeks and result in weight loss (up to –2.8 kg at 26 weeks and up to –2.5 kg at 52 weeks) in patients with T2DM who are treatment-naïve or taking other antidiabetes agents, including metformin, sulfonylurea, and TZD.51–53 Evaluation of the once-weekly formulation of exenatide showed reductions in HbA1c of –1.9% at 30 weeks and –2.0% at 52 weeks with a weight loss of –3.7 kg at 30 weeks and –4.1 kg over 52 weeks of treatment.46,54

CONCLUSION

In the United States, the epidemics of excessive weight and T2DM have contributed to an increased medical risk for many individuals. Comprehensive diabetes treatments targeting not only hyperglycemia but also frequently associated overweight/obesity, hypertension, and dyslipidemia will be required to reduce such risk. Current treatment strategies have evolved based on updated clinical guidelines and trials, as well as practice experience, including those related to newer agents. Incretin-based therapies, such as the GLP-1 receptor agonist, exenatide, and the DPP-4 inhibitors, sitagliptin and saxagliptin, are important additions to the treatment armamentarium, offering a reduction in hyperglycemia and beneficial effects on weight (reduction with exenatide and neutral with sitagliptin), and have been shown to improve several CV risk factors.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. National Diabetes Statistics, 2007 fact sheet. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2008. Available at: http://www.diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/statistics/index.htm. Accessed September 16, 2009.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among adults with diagnosed diabetes: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004; 53:1066–1068.

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2009. Diabetes Care 2009; 32(suppl 1):S13–S61.

- Hoerger TJ, Segel JE, Gregg EW, Saaddine JB. Is glycemic control improving in U.S. adults? Diabetes Care 2008; 31:81–86.

- Stratton IM, Cull CA, Adler AI, Matthews DR, Neil HA, Holman RR. Additive effects of glycaemia and blood pressure exposure on risk of complications in type 2 diabetes: a prospective observational study (UKPDS 75). Diabetologia 2006; 49:1761–1769.

- Ong KL, Cheung BM, Wong LY, Wat NM, Tan KC, Lam KS. Prevalence, treatment, and control of diagnosed diabetes in the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2004. Ann Epidemiol 2008; 18:222–229.

- Engelgau MM, Geiss LS, Saaddine JB, et al. The evolving diabetes burden in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:945–950.

- Fox CS, Coady S, Sorlie PD, et al. Trends in cardiovascular complications of diabetes. JAMA 2004; 292:2495–2499.

- Turner R, Cull C, Holman R. United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study 17: a 9-year update of a randomized, controlled trial on the effect of improved metabolic control on complications in noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 1996; 124(1 Pt 2):136–145.

- Mulnier HE, Seaman HE, Raleigh VS, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Colhoun HM, Lawrenson RA. Mortality in people with type 2 diabetes in the UK. Diabet Med 2006; 23:516–521.

- AACE Diabetes Mellitus Clinical Practice Guidelines Task Force. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists medical guidelines for clinical practice for the management of diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract 2007; 13(suppl 1):S4–S68.

- American Diabetes Association. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008; 31(suppl 1):S61−S78.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352:837–853.

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000; 321:405–412.

- The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2545–2559.

- The ADVANCE Collaborative Group. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:2560–2572.

- Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T, et al; for the VADT Investigators. Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2009; 360:129–139.

- Kerr M. ADA 2009: intensive glycemic control not directly linked to excess cardiovascular risk. Medscape Medical News Web site. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/704260_print. Published June 11, 2009. Accessed September 16, 2009.

- Skyler JS, Bergenstal R, Bonow RO, et al. Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:187–192.

- Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1577–1589.

- Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:580–591.

- Gaede P, Valentine WJ, Palmer AJ, et al. Cost-effectiveness of intensified versus conventional multifactorial intervention in type 2 diabetes: results and projections from the Steno-2 study. Diabetes Care 2008; 31:1510–1515.

- ACE/AACE Diabetes Road Map Task Force. Road maps to achieve glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract 2007; 13:260–268.

- Nathan DM, Buse JB, Davidson MB, et al. Medical management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a consensus algorithm for the initiation and adjustment of therapy: a consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:193–203.

- Alexander GC, Sehgal NL, Moloney RM, Stafford RS. National trends in treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus, 1994–2007. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:2088–2094.

- Sonnett TE, Levien TL, Neumiller JJ, Gates BJ, Setter SM. Colesevelam hydrochloride for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther 2009; 31:245–259.

- DeFronzo RA. Pharmacologic therapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131:281–303.

- Purnell JQ, Weyer C. Weight effect of current and experimental drugs for diabetes mellitus: from promotion to alleviation of obesity. Treat Endocrinol 2003; 2:33–47.

- Klein S, Sheard NF, Pi-Sunyer X, et al. Weight management through lifestyle modification for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes: rationale and strategies: a statement of the American Diabetes Association, the North American Association for the Study of Obesity, and the American Society for Clinical Nutrition. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:2067–2073.

- Stonehouse A, Okerson T, Kendall D, Maggs D. Emerging incretin based therapies for type 2 diabetes: incretin mimetics and DPP-4 inhibitors. Curr Diabetes Rev 2008; 4:101–109.

- Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab 2006; 3:153–165.

- Amori RE, Lau J, Pittas AG. Efficacy and safety of incretin therapy in type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007; 298:194–206.

- Buse JB, Henry RR, Han J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in sulfonylurea-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:2628–2635.

- DeFronzo RA, Ratner RE, Han J, Kim DD, Fineman MS, Baron AD. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control and weight over 30 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2005; 28:1092–1100.

- Kendall DM, Riddle MC, Rosenstock J, et al. Effects of exenatide (exendin-4) on glycemic control over 30 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin and a sulfonylurea. Diabetes Care 2005; 28:1083–1091.

- Aschner P, Kipnes MS, Lunceford JK, et al. Effect of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:2632−2637.

- Charbonnel B, Karasik A, Liu J, Wu M, Meininger G, for the Sitagliptin Study 020 Group. Efficacy and safety of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin added to ongoing metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin alone. Diabetes Care 2006; 29:2638–2643.

- Scott R, Wu M, Sanchez M, Stein P. Efficacy and tolerability of the dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor sitagliptin as monotherapy over 12 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract 2007; 61:171–180.

- Januvia. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 63rd edition. Montvale, NJ: Physicians’ Desk Reference Inc; 2008:2048–2054.

- Janumet. Physicians’ Desk Reference. 63rd edition. Montvale, NJ: Physicians’ Desk Reference Inc; 2008:2041–2048.

- Goldstein BJ, Feinglos MN, Lunceford JK, Johnson J, Williams-Herman DE, for the Sitagliptin 036 Study Group. Effect of initial combination therapy with sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitor, and metformin on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007; 30:1979–1987.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. FDA approves new drug treatment for type 2 diabetes. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm174780.htm. Published July 31, 2009. Accessed September 18, 2009.

- Byetta [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2009.

- Edwards CM, Stanley SA, Davis R, et al. Exendin-4 reduces fasting and postprandial glucose and decreases energy intake in healthy volunteers. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2001; 281:E155–E161.

- DeFronzo RA, Okerson T, Viswanathan P, Guan X, Holcombe JH, MacConell L. Effects of exenatide versus sitagliptin on postprandial glucose, insulin and glucagon secretion, gastric emptying, and caloric intake: a randomized, cross-over study. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24:2943–2952.

- Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K, et al. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority study. Lancet 2008; 372:1240–1250.

- Klonoff DC, Buse JB, Nielsen LL, et al. Exenatide effects on diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular risk factors and hepatic biomarkers in patients with type 2 diabetes treated for at least 3 years. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24:275–286.

- Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:762–768.

- Blonde L, Klein EJ, Han J, et al. Interim analysis of the effects of exenatide treatment on A1C, weight and cardiovascular risk factors over 82 weeks in 314 overweight patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2006; 8:436–447.

- Baggio LL, Drucker DJ, Maida A, Lamont BJ. ADA 2008: incretin-based therapeutics. MedscapeCME Web site. http://www.medscape.com/viewprogram/15786. Accessed September 18, 2009.

- Garber A, Henry R, Ratner R, et al. Liraglutide versus glimepiride monotherapy for type 2 diabetes (LEAD-3 Mono): a randomised, 52-week, phase III, double-blind, parallel-treatment trial. Lancet 2009; 373:473–481.

- Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride, and placebo, all in combination with metformin, in type 2 diabetes: the LEAD (liraglutide effect and action in diabetes)-2 study. Diabetes Care 2009; 32:84–90.

- Marre M, Shaw J, Brändle M, et al. Liraglutide, a once-daily human GLP-1 analogue, added to a sulphonylurea over 26 weeks produces greater improvements in glycaemic and weight control compared with adding rosiglitazone or placebo in subjects with type 2 diabetes (LEAD-1 SU). Diabet Med 2009; 26:268–278.

- Bergenstal RM, Kim T, Trautmann M, Zhuang D, Okerson T, Taylor K. Exenatide once weekly elicited improvements in blood pressure and lipid profile over 52 weeks in patients with type 2 diabetes. Circulation 2008; 118:S1086. Abstract 1239.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that almost 24 million Americans, or 7.8% of the population, have diabetes; 90% to 95% of these have type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1 Diabetes and excessive weight often coexist. An analysis of data from the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) showed that among individuals with diabetes, 85% were overweight or obese and 55% were obese.2

Gaps remain in the management of T2DM between the goals for clinical parameters of care (eg, control of glucose, blood pressure [BP], and lipids) and actual clinical practice.3 NHANES data reveal that glycemic control improved from a mean glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 7.82% in 1999–2000 to 7.18% in 2003–2004.4 Hazard models based on the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 10-year outcomes data in 4,320 newly diagnosed T2DM patients suggest that a sustained decrease in HbA1c of 0.511 percentage points could reduce diabetes complications by 10.7%.4,5

Additional analysis of NHANES data showed that in 2003–2004, about 57% of individuals achieved glycemic control, 48% reached BP targets, and 50% achieved target cholesterol goals.Only about 13% of diabetes patients achieved their target goals for all three parameters concurrently.6

This article reviews the association between cardiometabolic risk and the current antihyperglycemic treatments for patients with T2DM, with a focus on the role of incretin-related therapies.

THE IMPORTANCE OF CARDIOMETABOLIC RISK IN T2DM

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality among people with diabetes and is the reported cause of mortality in up to 65% of deaths in persons with diabetes in the United States.7 The risk of CVD is two- to fourfold greater among adults with diabetes than among adults who do not have diabetes.8 The risk of CVD in patients with T2DM was evident in the UKPDS 17, where macrovascular complications, including CVD, were about twice as common as microvascular complications (20% vs 9%) after 9 years of follow-up.9 A study that involved more than 44,000 patients showed an almost double rate of mortality from all causes among individuals with T2DM compared with those with no diabetes (hazard ratio, 1.93; 95% confidence interval, 1.89 to 1.97).10 Current guidelines recommend aggressive management of CV risk factors, including BP control, correction of atherogenic dyslipidemia, glycemic control, weight reduction for those who are overweight or obese, and smoking cessation for those who smoke.3,11 Lifestyle interventions, including weight reduction and appropriately prescribed physical activity, result in reduced CV risk factors, which can help slow the progression of T2DM.12

GOALS OF T2DM THERAPY

Several studies have demonstrated that glycemic control can delay or prevent the development and progression of microvascular complications.13,14 UKPDS 33 showed that more intensive blood glucose control (median HbA1c 7.0%) in patients with T2DM followed over 10 years significantly (P = .029) reduced the risk for any diabetes-related end point by 12% compared with conventional therapy (median HbA1c 7.9%). Most of the risk reduction was accounted for by a 25% risk reduction in microvascular end points (P = .0099).13 Another report (UKPDS 35) demonstrated that HbA1c was strongly related to microvascular effects, with a 1% reduction in HbA1c associated with a 37% reduction in microvascular complications.14

Does intensive glucose control reduce CV risk?

To resolve the ongoing question of whether intensive glucose control can lead to a reduction in CV risk in patients with T2DM, three large, long-term trials were conducted within the last decade.15–18 Two of these, the Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) and Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron Modified Release Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE) trials, each enrolled more than 10,000 previously treated patients with long-standing T2DM. Patients were randomized to standard or intensive glycemic control for 3.5 years in the ACCORD trial and for 5 years in the ADVANCE trial.15,16

The ACCORD and ADVANCE trials, along with the smaller Veterans Administration Diabetes Trial (VADT) (N = 1,791), failed to show that more intensive glycemic control significantly reduced CVD.15–17 Additionally, the glycemic control component of ACCORD was halted because of increased mortality in the intensive arm compared with the standard arm.15 Further analyses of ACCORD data presented at the 69th Scientific Sessions of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) showed that HbA1c values lower than 7.0% did not explain the increased mortality. The 20% higher risk of death for every 1.0% increase in HbA1c greater than 6.0% suggests that glucose concentrations even lower than the general HbA1c goal of less than 7.0% may be appropriate in some patients.18 The most recent finding from VADT was that CV risk was dependent on disease duration and presence of comorbidities. Intensive therapy seemed to work best in patients with diabetes of less than 15 years’ duration, while risk of a CV event was more than doubled with intensive therapy in patients having diabetes for more than 21 years.

Clarification of treatment goals

A position statement of the ADA and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association19 concluded that the “evidence obtained from ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VADT does not suggest the need for major changes in glycemic control targets but, rather, additional clarification of the language that has consistently stressed individualization.” They state that while the general HbA1c goal of less than 7.0% seems reasonable, even lower HbA1c goals may be appropriate for some patients if they can be achieved without significant hypoglycemia or other adverse effects. Such patients might include those with diabetes of short duration, long life expectancy, or no significant CVD or hypoglycemia. Conversely, higher HbA1c goals may be appropriate for patients with limited life expectancy, a history of severe hypoglycemia, established microvascular or macrovascular complications, significant other comorbid conditions, or longstanding diabetes in whom an HbA1c of less than 7.0% has been difficult to attain despite optimal treatment and diabetes self-management education.19

Long-term risk reduction

A 10-year, postinterventional follow-up study (UKPDS 80) of the UKPDS survivor cohort was reported recently.20 Results showed that despite an early loss of glycemic differences between patients treated with diet and those treated with intensive regimens (sulfonylurea or insulin; metformin in overweight patients), the pharmacotherapy group demonstrated a prolonged reduction in microvascular risk as well as a significant reduction in the risk for myocardial infarction (15% [P = .01] in the sulfonylurea-insulin group and 33% [P = .005] in the metformin group) and death from any cause.20 This suggests that early improvement in glycemic control is associated with long-term benefits in the micro- and macrovascular health of patients with T2DM.

Additionally, the recent long-term follow-up of the Steno-2 study21 showed that a multifactorial intervention striving for intensive glucose, BP, and lipid control that included the use of renin-angiotensin system blockers, aspirin, and lipid-lowering agents not only reduced the risk of nonfatal CVD among patients with T2DM and microalbuminuria, but also had sustained beneficial effects on vascular complications and on rates of death from any cause and from CV causes. From a health care payer perspective, intensive multifactorial intervention was more likely to be cost-effective than conventional treatment in Denmark, especially if applied in a primary care setting.22

Comprehensive care needed

The lower-than-expected rates of CV outcomes in the ACCORD, ADVANCE, VADT, and Steno-2 studies reinforce the importance of comprehensive diabetes care that treats not only hyperglycemia but also elevated BP and dyslipidemia; these are considered the “ABCs” of diabetes.11,19 The 2009 ADA standards of medical care guidelines recommend that for most T2DM patients, HbA1c should be maintained at less than 7.0%,3 while the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) 2007 guidelines state that HbA1c should be 6.5% or less.11 Both organizations stress the importance of individualized goals, as discussed above, and advocate BP goals of less than 130/80 mm Hg and dyslipidemia goals of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) less than 100 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) greater than 40 mg/dL for men and 50 mg/dL for women, and triglycerides less than 150 mg/dL. It is recommended that an optional LDL-C goal of less than 70 mg/dL be considered for individuals with overt CVD.

CURRENT ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC TREATMENT STRATEGIES

In response to new insights from clinical research and emerging treatment strategies, disease-specific organizations and medical specialty societies regularly revise and update their treatment guidelines and algorithms. These resources recommend that glycemic progress should be regularly monitored and pharmacologic therapy titrated or new drugs added promptly if glycemic goals are not met after 2 to 3 months.

Several algorithms combine scientific evidence with expert clinical opinion to guide physicians in treating their patients with T2DM. The American College of Endocrinology (ACE)/AACE road maps are designed to help develop individualized treatment regimens to achieve an HbA1c of 6.5% or less.23 The algorithm from a writing group assembled by the ADA and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) similarly promotes pharmacologic treatment together with lifestyle modifications to maintain a glycemic goal of HbA1c less than 7.0%.24

OVERVIEW OF ANTIHYPERGLYCEMIC TREATMENT APPROACHES

Initial oral therapy

T2DM is usually treated initially with a single oral agent. Consistent with the progressive nature of the disease, patients often eventually require one or more additional oral agents and in many cases insulin.13,27 Choice of specific agents is based on individual patient circumstances, including the need for weight loss and control of fasting versus postprandial glucose, the presence of dyslipidemia and hypertension, and the risk for and potential consequences of hypoglycemia.24 T2DM patients with severely uncontrolled and symptomatic hyperglycemia are best treated, at least initially, with a combination of insulin therapy and lifestyle intervention, often with metformin.

Metformin. The recently revised ADA/EASD writing group algorithm recommends that patients not requiring initial insulin begin treatment with metformin at the time of diagnosis unless there are contraindications.24 Metformin is not associated with hypoglycemia and is considered weight-neutral, although some patients may lose weight.28

Sulfonylureas. Sulfonylureas stimulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells; their use may be associated with hypoglycemia and weight gain. Mechanisms for weight gain with sulfonylureas include reduction of glucosuria and increased caloric intake to prevent or treat hypoglycemia.11,28 Nateglinide and repaglinide are nonsulfonylurea oral insulin secretagogues. They result in rapid and relatively short-lived insulin responses and are usually administered three times a day, before each meal. Their use may be associated with weight gain and hypoglycemia.11

Thiazolidinediones. Thiazolidinediones (TZD) increase insulin sensitivity in muscle, adipose tissue, and the liver. Hypoglycemia is uncommon with TZD monotherapy but weight gain related to increased and redistributed adiposity and fluid retention frequently occurs.

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors. The alpha-glucosidase inhibitors are administered before meals and primarily reduce postprandial hyperglycemia. They are generally weight-neutral.28

Insulin. Insulin and insulin analogues are the most effective antihyperglycemic agents, but their use can be associated with hypoglycemia and clinically significant weight gain.28

Colesevelam. Colesevelam is a bile acid sequestrant that was recently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an antihyperglycemic therapy in people with T2DM. At a dosage of 1.875 g BID or 3.75 g QD in combination with a sulfonylurea, metformin, or insulin therapy, reductions in HbA1c compared with placebo in clinical trials of colesevelam have ranged from –0.5% to –0.7% (P < .02). Frequency of hypoglycemia and weight gain is low with this agent.26

Weight management. Weight reduction is important for overweight or obese patients with T2DM.27,28 Even moderate weight loss (5% of body weight) can be associated with improved insulin action and reduced hyperglycemia.29 Conversely, weight gain has been shown to worsen hyperglycemia and other CV risk factors. Treatment-related weight gain can also lead to decreased regimen adherence, contributing to poor glycemic control.28

THE ROLE OF INCRETIN HORMONES AND INCRETIN-BASED THERAPIES IN T2DM PATIENTS

Over the last few years, the role of incretin hormones and their contribution to diabetes pathophysiology has become more apparent. The incretin effect refers to the observation that orally administered glucose elicits a greater insulin response than does glucose administered intravenously to produce equivalent blood glucose concentrations.30,31 The incretin effect is diminished in patients with T2DM.

Hormone mediation of the incretin effect