User login

Hospitalists and ACC in Pandemic Flu

Major natural disasters, such as Hurricane Rita and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, have reinforced the reality that health care workers may be asked to treat patients outside the traditional hospital setting.1 The emergence of H5N1 avian influenza in Southeast Asia has also raised concerns about a potential worldwide pandemic influenza.2 Since 2003, the number of avian influenza cases in humans has totaled 387, with 245 deaths.3 While H5N1 influenza has thus far been largely confined to avian populations, the virulence of this strain has raised concern regarding the possible emergence of enhanced human transmission.4 While impossible to accurately forecast the devastation of the next pandemic on the health system, anything similar to the pandemics of the past century will require a large coordinated response by the health system. The most severe pandemic in the past century occurred in 1918 to 1919. The estimated deaths attributed to this worldwide ranges from 20 to 100 million persons,57 with >500,000 of these deaths in the United States.6, 7 In comparison, the annual rate of deaths related to influenza in the United States ranges from 30,000 to 50,000.2, 5 It has been estimated that the next pandemic influenza could cause 75 to 100 million people to become ill, and lead to as many as 1.9 million deaths in the United States.8 In response, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has stressed the importance of advanced planning,9 and the most recent Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD‐21) directs health care organizations and the federal government to develop preparedness plans to provide surge capacity care in times of a catastrophic health event.10 A previous report by one of the authors emphasized the need for hospitalists to play a major role in institutional planning for a pandemic influenza.11

The Alternate Care Center

The concept of offsite care in an influenza pandemic has previously been described, and we will refer to these as Alternate Care Centers (ACCs). Although the literature describes different models of care at an ACC (Table 1),12 we believe an ACC should be activated as an extension of the supporting hospital, once the hospital becomes over capacity despite measures to grow its inpatient service volume.

| Overflow hospital providing full range of care |

| Patient isolation and alternative to home care for infectious patients |

| Expanded ambulatory care |

| Care for recovering, noninfectious patients |

| Limited supportive care for noncritical patients |

| Primary triage and rapid patient screening |

| Quarantine |

Our health system is a large academic medical center, and we have been working with our state to develop a plan to establish and operate an ACC for the next pandemic influenza. Our plans call for an ACC to be activated as an overflow hospital once our hospitals are beyond 120% capacity. We have gone through several functional and tabletop exercises to help identify critical issues that are likely to arise during a real pandemic. Subsequent to these exercises, we have convened an ACC Planning Work Group, reviewed the available literature on surge hospitals, and have focused our recent efforts on several key areas.13 First, it will be important to clearly outline the general services that will be available at this offsite location (Table 2), and this information should be disseminated to the local medical community and the general public. An informed public, with a clear understanding that the ACC is an extension of the hospital with hospitalists in charge of medical care, is more likely to accept getting healthcare in this setting.

|

| IVF administration |

| Parenteral medication administration (eg, antibiotics, steroids, narcotic analgesics, antiemetics) |

| Oxygen support |

| Palliative care services |

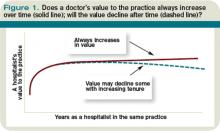

Second, hospitals and the ACCas an extension to the main hospitalwill be asked to provide care to patients referred from several external facilities. Thus, the relationship between the ACC and the main hospital is critical. In a situation where local and even national health care assets will be overwhelmed, having a traditional hospital take full ownership of the ACC and facilitate the transport of patients in and out of the center will be vital to the maintenance of operations. Figure 1 illustrates an example of how patients may be transitioned from 1 site of care to another.

Third, the logistics of establishing an ACC should include details regarding: (1) securing a location that is able to accommodate the needs of the ACC; (2) predetermining the scope of care that can be provided; (3) procuring the necessary equipment and supplies; (4) planning for an adequate number of workforce and staff members; and (5) ensuring a reliable communication plan within the local health system and with state and federal public health officials.14 Staffing shortages and communication barriers are worthy of further emphasis. Given conservative estimates that up to 35% of staff may become ill, refuse to work, or remain home to care for ill family members,15 it is essential that hospitals and regional emergency planners develop a staffing model for the ACC, well in advance of a pandemic. These may include scenarios in which the recommended provider‐to‐patient ratio can not be met. Among the essential lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto (Ontario, Canada) was the importance of developing redundant and reliable communication plans among the healthcare providers.16, 17

Last, healthcare workers' concerns about occupational health and safety must be addressed, and strict measures to protect providers in the ACC need to be implemented.16 This includes providing all exposed staff with adequate personal protective equipment (eg, N‐95 masks), ensuring that all staff are vaccinated against the influenza virus, and implementing strict infection control (eg, hand washing) practices.

For more information, we refer the reader to references that contain further details on our ACC exercises13 and documents that outline concepts of operations in an ACC, developed by the Joint Commission and a multiagency working group.1, 14

The Hospitalist Physician and the ACC

During an influenza pandemic, physicians from all specialties will be vital to the success of the health systems' response. General internists,18 family practitioners, and pediatricians will be overextended in the ambulatory setting to provide intravenous (IV) fluids, antibiotics, and vaccines. Emergency physicians will be called upon to provide care for a burgeoning number of patient arrivals to the Emergency Department (ED), whose acuity is higher than in nonpandemic times. These physicians' clinical expertise at their sites of practice may be severely tested. Hospitalists, given their inpatient focus will be ideally suited to provide medical care to patients admitted to the ACC.

Previous physician leadership at surge hospitals has come from multiple specialties. Case studies describing the heroic physician leadership after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita represented pediatricians, family physicians, emergency department physicians, and internists.1 In an influenza pandemic, patients in the ACC will require medical care that would, under nonsurge situations, warrant inpatient care. Hospitalists are well poised to lead the response in the ACC for pandemic flu. Hospitalists have expanded their presence into many clinical and administrative responsibilities in their local health systems,19 and the specialty of hospital medicine has evolved to incorporate many of the skills and expertise that would be required of physician leaders who manage an ACC during an influenza pandemic.

While the actual morbidity and mortality associated with the next pandemic are uncertain, it is likely that the number of patients who seek out medical care will exceed current capacity. With constrained space and resources, patients will require appropriate and safe transition to and from the hospital and the ACC. Hospitalists have become leaders in developing and promoting quality transition of care out of acute care settings.20, 21 Their expertise in optimizing this vulnerable time period in patients' healthcare experience should help hospitalists make efficient and appropriate transition care decisions even during busy times and in an alternate care location. Many hospitalists have also developed local and national expertise in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety (PS) initiatives in acute care settings.22 Hospitalists can lead the efforts to apply QI and PS practices in the ACC. These interventions should focus on the potential to be effective in improving patient care, but also consider issues such as ease of implementation, cost, and potential for harm.23

An influenza pandemic will require all levels of the healthcare system to work together to develop a coordinated approach to patient care. Previously, Kisuule et al.24 described how hospitalists can expand their role to include public health. The hospitalists' leadership in the ACC fits well with their descriptions, and hospitalists should work with local, state, and national public health officials in pandemic flu planning. Their scope of practice and clinical expertise will call on them to play key roles in recognition of the development of a pandemic; help lead the response efforts; provide education to staff, patients, and family members; develop clinical care guidelines and pathways for patients; utilize best practices in the use of antimicrobial therapy; and provide appropriate palliative care. Depending on the severity of the influenza pandemic, mortality could be considerable. Many hospitalists have expertise in palliative care at their hospitals,2527 and this skill set will be invaluable in providing compassionate end‐of‐life care to patients in the ACC.

In a pandemic, the most vulnerable patient populations will likely be disproportionately affected, including the elderly, children, and the immune‐compromised. Hospitalists who care regularly for these diverse groups of patients through the spectrum of illness and recovery will be able to address the variety of clinical and nonclinical issues that arise. If the ACC will provide care for children, hospitalists with training in pediatrics, medicine‐pediatrics, or family medicine should be available.

Additional Considerations

While many unanswered questions remain about how to best utilize the ACC, hospitalists are ideally suited to help lead planning efforts for an ACC for pandemic flu. Other issues that may require additional considerations include: (1) whether to strictly care for patients with influenza symptoms and influenza‐related illnesses or to provide care for all patients at the ACC; (2) what to do when patients refuse transfer to and from the ACC; (3) determining the optimal staffing model for patient care providers and to provide care for a wide range of age groups; (4) how the ACC will be funded; (5) how and where to store stockpiles; (6) developing redundant and coordinated communication plans; and (7) planning for reliable access to information and technology from the ACC.

Conclusions

We have introduced the concept of the ACC for the hospitalist community, and emphasized the benefits of engaging hospitalists to lead the ACC initiative at their own health organizations during pandemic flu. As hospitalists currently serve in many of these roles and possess the skills to provide care and lead these initiatives, we encourage hospitalists to contact their hospital administrators to volunteer to assist with preparation efforts.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Surge Hospitals: Providing Safe Care in Emergencies;2006. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/802E9DA4‐AE80‐4584‐A205‐48989C5BD684/0/surge_hospital.pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- .Pandemic influenza: are we ready?Disaster Manag Response.2005;3(3):61–67.

- Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO.2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2008_09_10/en/index.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,, et al.Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus.Lancet.2008;371(9622):1464–1475.

- .Preparing for the next pandemic.N Engl J Med.2005;352(18):1839–1842.

- ,,.Influenza pandemic preparedness action plan for the United States: 2002 update.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(5):590–596.

- ,,, et al.Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918‐1919 influenza pandemic.JAMA.2007;298(6):644–654.

- The Health Care Response to Pandemic Influenza: Position Paper.Philadelphia, PA:American College of Physicians;2006.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HHS Pandemic Influenza Plan. November2005. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan. Accessed May 2009.

- Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD‐21.2007. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2007/10/20071018‐10.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,.Pandemic influenza and the hospitalist: apocalypse when?J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):118–123.

- ,,,,.The prospect of using alternative medical care facilities in an influenza pandemic.Biosecur Bioterror.2006;4(4):384–390.

- ,,, et al.Pandemic influenza and acute care centers (ACCs): taking care of sick patients in a non‐hospital setting.Biosecur Bioterror.2008;6(4):335–348.

- ,,.Acute Care Center. Modular Emergency Medical System: Concept of Operations for the Acute Care Center (ACC).Mass Casualty Care Strategy for A Biological Terrorism Incident. May2003. Available at: http://dms.dartmouth.edu/nnemmrs/resources/surge_capacity_guidance/documents/acute_care_center__concept_ of_operations. pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- Illinois Department of Public Health. Influenza.2007. Available at: http://www.idph.state.il.us/flu/pandemicfs.htm. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,.Learning from SARS in Hong Kong and Toronto.JAMA.2004;291(20):2483–2487.

- .Planning for epidemics—the lessons of SARS.N Engl J Med.2004;350(23):2332–2334.

- .The role of internists during epidemics, outbreaks, and bioterrorist attacks.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(1):131–136.

- ,.The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States.Swiss Med Wkly.2006;136(37‐38):591–596.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):314–323.

- ,.Executing high‐quality care transitions: a call to do it right.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):287–290.

- .Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later.J Hosp Med.2006;1(4):248–252.

- ,.Implementing patient safety interventions in your hospital: what to try and what to avoid.Med Clin North Am.2008;92(2):275–293, vii‐viii.

- ,,,.Expanding the roles of hospitalist physicians to include public health.J Hosp Med.2007;2(,2):93–101.

- ,,,,,.Evaluating the California hospital initiative in palliative services.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(2):227–230.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):5–6.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):21–28.

Major natural disasters, such as Hurricane Rita and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, have reinforced the reality that health care workers may be asked to treat patients outside the traditional hospital setting.1 The emergence of H5N1 avian influenza in Southeast Asia has also raised concerns about a potential worldwide pandemic influenza.2 Since 2003, the number of avian influenza cases in humans has totaled 387, with 245 deaths.3 While H5N1 influenza has thus far been largely confined to avian populations, the virulence of this strain has raised concern regarding the possible emergence of enhanced human transmission.4 While impossible to accurately forecast the devastation of the next pandemic on the health system, anything similar to the pandemics of the past century will require a large coordinated response by the health system. The most severe pandemic in the past century occurred in 1918 to 1919. The estimated deaths attributed to this worldwide ranges from 20 to 100 million persons,57 with >500,000 of these deaths in the United States.6, 7 In comparison, the annual rate of deaths related to influenza in the United States ranges from 30,000 to 50,000.2, 5 It has been estimated that the next pandemic influenza could cause 75 to 100 million people to become ill, and lead to as many as 1.9 million deaths in the United States.8 In response, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has stressed the importance of advanced planning,9 and the most recent Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD‐21) directs health care organizations and the federal government to develop preparedness plans to provide surge capacity care in times of a catastrophic health event.10 A previous report by one of the authors emphasized the need for hospitalists to play a major role in institutional planning for a pandemic influenza.11

The Alternate Care Center

The concept of offsite care in an influenza pandemic has previously been described, and we will refer to these as Alternate Care Centers (ACCs). Although the literature describes different models of care at an ACC (Table 1),12 we believe an ACC should be activated as an extension of the supporting hospital, once the hospital becomes over capacity despite measures to grow its inpatient service volume.

| Overflow hospital providing full range of care |

| Patient isolation and alternative to home care for infectious patients |

| Expanded ambulatory care |

| Care for recovering, noninfectious patients |

| Limited supportive care for noncritical patients |

| Primary triage and rapid patient screening |

| Quarantine |

Our health system is a large academic medical center, and we have been working with our state to develop a plan to establish and operate an ACC for the next pandemic influenza. Our plans call for an ACC to be activated as an overflow hospital once our hospitals are beyond 120% capacity. We have gone through several functional and tabletop exercises to help identify critical issues that are likely to arise during a real pandemic. Subsequent to these exercises, we have convened an ACC Planning Work Group, reviewed the available literature on surge hospitals, and have focused our recent efforts on several key areas.13 First, it will be important to clearly outline the general services that will be available at this offsite location (Table 2), and this information should be disseminated to the local medical community and the general public. An informed public, with a clear understanding that the ACC is an extension of the hospital with hospitalists in charge of medical care, is more likely to accept getting healthcare in this setting.

|

| IVF administration |

| Parenteral medication administration (eg, antibiotics, steroids, narcotic analgesics, antiemetics) |

| Oxygen support |

| Palliative care services |

Second, hospitals and the ACCas an extension to the main hospitalwill be asked to provide care to patients referred from several external facilities. Thus, the relationship between the ACC and the main hospital is critical. In a situation where local and even national health care assets will be overwhelmed, having a traditional hospital take full ownership of the ACC and facilitate the transport of patients in and out of the center will be vital to the maintenance of operations. Figure 1 illustrates an example of how patients may be transitioned from 1 site of care to another.

Third, the logistics of establishing an ACC should include details regarding: (1) securing a location that is able to accommodate the needs of the ACC; (2) predetermining the scope of care that can be provided; (3) procuring the necessary equipment and supplies; (4) planning for an adequate number of workforce and staff members; and (5) ensuring a reliable communication plan within the local health system and with state and federal public health officials.14 Staffing shortages and communication barriers are worthy of further emphasis. Given conservative estimates that up to 35% of staff may become ill, refuse to work, or remain home to care for ill family members,15 it is essential that hospitals and regional emergency planners develop a staffing model for the ACC, well in advance of a pandemic. These may include scenarios in which the recommended provider‐to‐patient ratio can not be met. Among the essential lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto (Ontario, Canada) was the importance of developing redundant and reliable communication plans among the healthcare providers.16, 17

Last, healthcare workers' concerns about occupational health and safety must be addressed, and strict measures to protect providers in the ACC need to be implemented.16 This includes providing all exposed staff with adequate personal protective equipment (eg, N‐95 masks), ensuring that all staff are vaccinated against the influenza virus, and implementing strict infection control (eg, hand washing) practices.

For more information, we refer the reader to references that contain further details on our ACC exercises13 and documents that outline concepts of operations in an ACC, developed by the Joint Commission and a multiagency working group.1, 14

The Hospitalist Physician and the ACC

During an influenza pandemic, physicians from all specialties will be vital to the success of the health systems' response. General internists,18 family practitioners, and pediatricians will be overextended in the ambulatory setting to provide intravenous (IV) fluids, antibiotics, and vaccines. Emergency physicians will be called upon to provide care for a burgeoning number of patient arrivals to the Emergency Department (ED), whose acuity is higher than in nonpandemic times. These physicians' clinical expertise at their sites of practice may be severely tested. Hospitalists, given their inpatient focus will be ideally suited to provide medical care to patients admitted to the ACC.

Previous physician leadership at surge hospitals has come from multiple specialties. Case studies describing the heroic physician leadership after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita represented pediatricians, family physicians, emergency department physicians, and internists.1 In an influenza pandemic, patients in the ACC will require medical care that would, under nonsurge situations, warrant inpatient care. Hospitalists are well poised to lead the response in the ACC for pandemic flu. Hospitalists have expanded their presence into many clinical and administrative responsibilities in their local health systems,19 and the specialty of hospital medicine has evolved to incorporate many of the skills and expertise that would be required of physician leaders who manage an ACC during an influenza pandemic.

While the actual morbidity and mortality associated with the next pandemic are uncertain, it is likely that the number of patients who seek out medical care will exceed current capacity. With constrained space and resources, patients will require appropriate and safe transition to and from the hospital and the ACC. Hospitalists have become leaders in developing and promoting quality transition of care out of acute care settings.20, 21 Their expertise in optimizing this vulnerable time period in patients' healthcare experience should help hospitalists make efficient and appropriate transition care decisions even during busy times and in an alternate care location. Many hospitalists have also developed local and national expertise in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety (PS) initiatives in acute care settings.22 Hospitalists can lead the efforts to apply QI and PS practices in the ACC. These interventions should focus on the potential to be effective in improving patient care, but also consider issues such as ease of implementation, cost, and potential for harm.23

An influenza pandemic will require all levels of the healthcare system to work together to develop a coordinated approach to patient care. Previously, Kisuule et al.24 described how hospitalists can expand their role to include public health. The hospitalists' leadership in the ACC fits well with their descriptions, and hospitalists should work with local, state, and national public health officials in pandemic flu planning. Their scope of practice and clinical expertise will call on them to play key roles in recognition of the development of a pandemic; help lead the response efforts; provide education to staff, patients, and family members; develop clinical care guidelines and pathways for patients; utilize best practices in the use of antimicrobial therapy; and provide appropriate palliative care. Depending on the severity of the influenza pandemic, mortality could be considerable. Many hospitalists have expertise in palliative care at their hospitals,2527 and this skill set will be invaluable in providing compassionate end‐of‐life care to patients in the ACC.

In a pandemic, the most vulnerable patient populations will likely be disproportionately affected, including the elderly, children, and the immune‐compromised. Hospitalists who care regularly for these diverse groups of patients through the spectrum of illness and recovery will be able to address the variety of clinical and nonclinical issues that arise. If the ACC will provide care for children, hospitalists with training in pediatrics, medicine‐pediatrics, or family medicine should be available.

Additional Considerations

While many unanswered questions remain about how to best utilize the ACC, hospitalists are ideally suited to help lead planning efforts for an ACC for pandemic flu. Other issues that may require additional considerations include: (1) whether to strictly care for patients with influenza symptoms and influenza‐related illnesses or to provide care for all patients at the ACC; (2) what to do when patients refuse transfer to and from the ACC; (3) determining the optimal staffing model for patient care providers and to provide care for a wide range of age groups; (4) how the ACC will be funded; (5) how and where to store stockpiles; (6) developing redundant and coordinated communication plans; and (7) planning for reliable access to information and technology from the ACC.

Conclusions

We have introduced the concept of the ACC for the hospitalist community, and emphasized the benefits of engaging hospitalists to lead the ACC initiative at their own health organizations during pandemic flu. As hospitalists currently serve in many of these roles and possess the skills to provide care and lead these initiatives, we encourage hospitalists to contact their hospital administrators to volunteer to assist with preparation efforts.

Major natural disasters, such as Hurricane Rita and Hurricane Katrina in 2005, have reinforced the reality that health care workers may be asked to treat patients outside the traditional hospital setting.1 The emergence of H5N1 avian influenza in Southeast Asia has also raised concerns about a potential worldwide pandemic influenza.2 Since 2003, the number of avian influenza cases in humans has totaled 387, with 245 deaths.3 While H5N1 influenza has thus far been largely confined to avian populations, the virulence of this strain has raised concern regarding the possible emergence of enhanced human transmission.4 While impossible to accurately forecast the devastation of the next pandemic on the health system, anything similar to the pandemics of the past century will require a large coordinated response by the health system. The most severe pandemic in the past century occurred in 1918 to 1919. The estimated deaths attributed to this worldwide ranges from 20 to 100 million persons,57 with >500,000 of these deaths in the United States.6, 7 In comparison, the annual rate of deaths related to influenza in the United States ranges from 30,000 to 50,000.2, 5 It has been estimated that the next pandemic influenza could cause 75 to 100 million people to become ill, and lead to as many as 1.9 million deaths in the United States.8 In response, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has stressed the importance of advanced planning,9 and the most recent Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD‐21) directs health care organizations and the federal government to develop preparedness plans to provide surge capacity care in times of a catastrophic health event.10 A previous report by one of the authors emphasized the need for hospitalists to play a major role in institutional planning for a pandemic influenza.11

The Alternate Care Center

The concept of offsite care in an influenza pandemic has previously been described, and we will refer to these as Alternate Care Centers (ACCs). Although the literature describes different models of care at an ACC (Table 1),12 we believe an ACC should be activated as an extension of the supporting hospital, once the hospital becomes over capacity despite measures to grow its inpatient service volume.

| Overflow hospital providing full range of care |

| Patient isolation and alternative to home care for infectious patients |

| Expanded ambulatory care |

| Care for recovering, noninfectious patients |

| Limited supportive care for noncritical patients |

| Primary triage and rapid patient screening |

| Quarantine |

Our health system is a large academic medical center, and we have been working with our state to develop a plan to establish and operate an ACC for the next pandemic influenza. Our plans call for an ACC to be activated as an overflow hospital once our hospitals are beyond 120% capacity. We have gone through several functional and tabletop exercises to help identify critical issues that are likely to arise during a real pandemic. Subsequent to these exercises, we have convened an ACC Planning Work Group, reviewed the available literature on surge hospitals, and have focused our recent efforts on several key areas.13 First, it will be important to clearly outline the general services that will be available at this offsite location (Table 2), and this information should be disseminated to the local medical community and the general public. An informed public, with a clear understanding that the ACC is an extension of the hospital with hospitalists in charge of medical care, is more likely to accept getting healthcare in this setting.

|

| IVF administration |

| Parenteral medication administration (eg, antibiotics, steroids, narcotic analgesics, antiemetics) |

| Oxygen support |

| Palliative care services |

Second, hospitals and the ACCas an extension to the main hospitalwill be asked to provide care to patients referred from several external facilities. Thus, the relationship between the ACC and the main hospital is critical. In a situation where local and even national health care assets will be overwhelmed, having a traditional hospital take full ownership of the ACC and facilitate the transport of patients in and out of the center will be vital to the maintenance of operations. Figure 1 illustrates an example of how patients may be transitioned from 1 site of care to another.

Third, the logistics of establishing an ACC should include details regarding: (1) securing a location that is able to accommodate the needs of the ACC; (2) predetermining the scope of care that can be provided; (3) procuring the necessary equipment and supplies; (4) planning for an adequate number of workforce and staff members; and (5) ensuring a reliable communication plan within the local health system and with state and federal public health officials.14 Staffing shortages and communication barriers are worthy of further emphasis. Given conservative estimates that up to 35% of staff may become ill, refuse to work, or remain home to care for ill family members,15 it is essential that hospitals and regional emergency planners develop a staffing model for the ACC, well in advance of a pandemic. These may include scenarios in which the recommended provider‐to‐patient ratio can not be met. Among the essential lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Toronto (Ontario, Canada) was the importance of developing redundant and reliable communication plans among the healthcare providers.16, 17

Last, healthcare workers' concerns about occupational health and safety must be addressed, and strict measures to protect providers in the ACC need to be implemented.16 This includes providing all exposed staff with adequate personal protective equipment (eg, N‐95 masks), ensuring that all staff are vaccinated against the influenza virus, and implementing strict infection control (eg, hand washing) practices.

For more information, we refer the reader to references that contain further details on our ACC exercises13 and documents that outline concepts of operations in an ACC, developed by the Joint Commission and a multiagency working group.1, 14

The Hospitalist Physician and the ACC

During an influenza pandemic, physicians from all specialties will be vital to the success of the health systems' response. General internists,18 family practitioners, and pediatricians will be overextended in the ambulatory setting to provide intravenous (IV) fluids, antibiotics, and vaccines. Emergency physicians will be called upon to provide care for a burgeoning number of patient arrivals to the Emergency Department (ED), whose acuity is higher than in nonpandemic times. These physicians' clinical expertise at their sites of practice may be severely tested. Hospitalists, given their inpatient focus will be ideally suited to provide medical care to patients admitted to the ACC.

Previous physician leadership at surge hospitals has come from multiple specialties. Case studies describing the heroic physician leadership after Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita represented pediatricians, family physicians, emergency department physicians, and internists.1 In an influenza pandemic, patients in the ACC will require medical care that would, under nonsurge situations, warrant inpatient care. Hospitalists are well poised to lead the response in the ACC for pandemic flu. Hospitalists have expanded their presence into many clinical and administrative responsibilities in their local health systems,19 and the specialty of hospital medicine has evolved to incorporate many of the skills and expertise that would be required of physician leaders who manage an ACC during an influenza pandemic.

While the actual morbidity and mortality associated with the next pandemic are uncertain, it is likely that the number of patients who seek out medical care will exceed current capacity. With constrained space and resources, patients will require appropriate and safe transition to and from the hospital and the ACC. Hospitalists have become leaders in developing and promoting quality transition of care out of acute care settings.20, 21 Their expertise in optimizing this vulnerable time period in patients' healthcare experience should help hospitalists make efficient and appropriate transition care decisions even during busy times and in an alternate care location. Many hospitalists have also developed local and national expertise in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety (PS) initiatives in acute care settings.22 Hospitalists can lead the efforts to apply QI and PS practices in the ACC. These interventions should focus on the potential to be effective in improving patient care, but also consider issues such as ease of implementation, cost, and potential for harm.23

An influenza pandemic will require all levels of the healthcare system to work together to develop a coordinated approach to patient care. Previously, Kisuule et al.24 described how hospitalists can expand their role to include public health. The hospitalists' leadership in the ACC fits well with their descriptions, and hospitalists should work with local, state, and national public health officials in pandemic flu planning. Their scope of practice and clinical expertise will call on them to play key roles in recognition of the development of a pandemic; help lead the response efforts; provide education to staff, patients, and family members; develop clinical care guidelines and pathways for patients; utilize best practices in the use of antimicrobial therapy; and provide appropriate palliative care. Depending on the severity of the influenza pandemic, mortality could be considerable. Many hospitalists have expertise in palliative care at their hospitals,2527 and this skill set will be invaluable in providing compassionate end‐of‐life care to patients in the ACC.

In a pandemic, the most vulnerable patient populations will likely be disproportionately affected, including the elderly, children, and the immune‐compromised. Hospitalists who care regularly for these diverse groups of patients through the spectrum of illness and recovery will be able to address the variety of clinical and nonclinical issues that arise. If the ACC will provide care for children, hospitalists with training in pediatrics, medicine‐pediatrics, or family medicine should be available.

Additional Considerations

While many unanswered questions remain about how to best utilize the ACC, hospitalists are ideally suited to help lead planning efforts for an ACC for pandemic flu. Other issues that may require additional considerations include: (1) whether to strictly care for patients with influenza symptoms and influenza‐related illnesses or to provide care for all patients at the ACC; (2) what to do when patients refuse transfer to and from the ACC; (3) determining the optimal staffing model for patient care providers and to provide care for a wide range of age groups; (4) how the ACC will be funded; (5) how and where to store stockpiles; (6) developing redundant and coordinated communication plans; and (7) planning for reliable access to information and technology from the ACC.

Conclusions

We have introduced the concept of the ACC for the hospitalist community, and emphasized the benefits of engaging hospitalists to lead the ACC initiative at their own health organizations during pandemic flu. As hospitalists currently serve in many of these roles and possess the skills to provide care and lead these initiatives, we encourage hospitalists to contact their hospital administrators to volunteer to assist with preparation efforts.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Surge Hospitals: Providing Safe Care in Emergencies;2006. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/802E9DA4‐AE80‐4584‐A205‐48989C5BD684/0/surge_hospital.pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- .Pandemic influenza: are we ready?Disaster Manag Response.2005;3(3):61–67.

- Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO.2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2008_09_10/en/index.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,, et al.Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus.Lancet.2008;371(9622):1464–1475.

- .Preparing for the next pandemic.N Engl J Med.2005;352(18):1839–1842.

- ,,.Influenza pandemic preparedness action plan for the United States: 2002 update.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(5):590–596.

- ,,, et al.Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918‐1919 influenza pandemic.JAMA.2007;298(6):644–654.

- The Health Care Response to Pandemic Influenza: Position Paper.Philadelphia, PA:American College of Physicians;2006.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HHS Pandemic Influenza Plan. November2005. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan. Accessed May 2009.

- Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD‐21.2007. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2007/10/20071018‐10.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,.Pandemic influenza and the hospitalist: apocalypse when?J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):118–123.

- ,,,,.The prospect of using alternative medical care facilities in an influenza pandemic.Biosecur Bioterror.2006;4(4):384–390.

- ,,, et al.Pandemic influenza and acute care centers (ACCs): taking care of sick patients in a non‐hospital setting.Biosecur Bioterror.2008;6(4):335–348.

- ,,.Acute Care Center. Modular Emergency Medical System: Concept of Operations for the Acute Care Center (ACC).Mass Casualty Care Strategy for A Biological Terrorism Incident. May2003. Available at: http://dms.dartmouth.edu/nnemmrs/resources/surge_capacity_guidance/documents/acute_care_center__concept_ of_operations. pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- Illinois Department of Public Health. Influenza.2007. Available at: http://www.idph.state.il.us/flu/pandemicfs.htm. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,.Learning from SARS in Hong Kong and Toronto.JAMA.2004;291(20):2483–2487.

- .Planning for epidemics—the lessons of SARS.N Engl J Med.2004;350(23):2332–2334.

- .The role of internists during epidemics, outbreaks, and bioterrorist attacks.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(1):131–136.

- ,.The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States.Swiss Med Wkly.2006;136(37‐38):591–596.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):314–323.

- ,.Executing high‐quality care transitions: a call to do it right.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):287–290.

- .Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later.J Hosp Med.2006;1(4):248–252.

- ,.Implementing patient safety interventions in your hospital: what to try and what to avoid.Med Clin North Am.2008;92(2):275–293, vii‐viii.

- ,,,.Expanding the roles of hospitalist physicians to include public health.J Hosp Med.2007;2(,2):93–101.

- ,,,,,.Evaluating the California hospital initiative in palliative services.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(2):227–230.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):5–6.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):21–28.

- Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Surge Hospitals: Providing Safe Care in Emergencies;2006. Available at: http://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/802E9DA4‐AE80‐4584‐A205‐48989C5BD684/0/surge_hospital.pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- .Pandemic influenza: are we ready?Disaster Manag Response.2005;3(3):61–67.

- Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO.2008. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/avian_influenza/country/cases_table_2008_09_10/en/index.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,, et al.Human infection with highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus.Lancet.2008;371(9622):1464–1475.

- .Preparing for the next pandemic.N Engl J Med.2005;352(18):1839–1842.

- ,,.Influenza pandemic preparedness action plan for the United States: 2002 update.Clin Infect Dis.2002;35(5):590–596.

- ,,, et al.Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918‐1919 influenza pandemic.JAMA.2007;298(6):644–654.

- The Health Care Response to Pandemic Influenza: Position Paper.Philadelphia, PA:American College of Physicians;2006.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). HHS Pandemic Influenza Plan. November2005. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/pandemicflu/plan. Accessed May 2009.

- Homeland Security Presidential Directive/HSPD‐21.2007. Available at: http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2007/10/20071018‐10.html. Accessed May 2009.

- ,.Pandemic influenza and the hospitalist: apocalypse when?J Hosp Med.2006;1(2):118–123.

- ,,,,.The prospect of using alternative medical care facilities in an influenza pandemic.Biosecur Bioterror.2006;4(4):384–390.

- ,,, et al.Pandemic influenza and acute care centers (ACCs): taking care of sick patients in a non‐hospital setting.Biosecur Bioterror.2008;6(4):335–348.

- ,,.Acute Care Center. Modular Emergency Medical System: Concept of Operations for the Acute Care Center (ACC).Mass Casualty Care Strategy for A Biological Terrorism Incident. May2003. Available at: http://dms.dartmouth.edu/nnemmrs/resources/surge_capacity_guidance/documents/acute_care_center__concept_ of_operations. pdf. Accessed May 2009.

- Illinois Department of Public Health. Influenza.2007. Available at: http://www.idph.state.il.us/flu/pandemicfs.htm. Accessed May 2009.

- ,,.Learning from SARS in Hong Kong and Toronto.JAMA.2004;291(20):2483–2487.

- .Planning for epidemics—the lessons of SARS.N Engl J Med.2004;350(23):2332–2334.

- .The role of internists during epidemics, outbreaks, and bioterrorist attacks.J Gen Intern Med.2007;22(1):131–136.

- ,.The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States.Swiss Med Wkly.2006;136(37‐38):591–596.

- ,,,.Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):314–323.

- ,.Executing high‐quality care transitions: a call to do it right.J Hosp Med.2007;2(5):287–290.

- .Reflections: the hospitalist movement a decade later.J Hosp Med.2006;1(4):248–252.

- ,.Implementing patient safety interventions in your hospital: what to try and what to avoid.Med Clin North Am.2008;92(2):275–293, vii‐viii.

- ,,,.Expanding the roles of hospitalist physicians to include public health.J Hosp Med.2007;2(,2):93–101.

- ,,,,,.Evaluating the California hospital initiative in palliative services.Arch Intern Med.2006;166(2):227–230.

- .Palliative care and hospitalists: a partnership for hope.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):5–6.

- .Palliative care in hospitals.J Hosp Med.2006;1(1):21–28.

Agent shows promise in acute leukemias

Delivering drugs in combination requires a certain balance, a balance that ensures the drugs act synergistically. And researchers say they have struck the right balance with a new drug that combines two old standbys.

Daunorubicin and cytarabine (or ara-C) have proven activity against acute leukemia. However, neither of the drugs has elicited impressive survival rates when given alone, according to Eric Feldman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a presentation at Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium XXVII, Dr Feldman discussed a new agent comprised of the two drugs that he theorizes will prove more effective than either drug alone.

“When you combine different combinations of cytarabine and daunorubicin, there are some ratios that, in fact, may be antagonistic or just additive,” Dr Feldman said. “But… there are some—particularly this 5-to-1 ara-C-to-daunorubicin—that may be synergistic. And the question is, how do you deliver to the leukemia cell this synergistic combination of drugs?”

For a long time, Dr Feldman said, scientists did not have the appropriate technology to accomplish that. But now they do, and they have made significant strides with the compound CPX-351.

“Basically, this is a liposomal combination of daunorubicin and ara-C,” Dr Feldman said. “But the unique feature is that it fixes a 5-to-1 molar ratio of ara-C with daunorubicin and delivers to the cell this ratio in this concentration.”

To test the tolerability and efficacy of this compound, researchers began a phase 1 trial of CPX-351. The majority of patients on the trial had acute myeloid leukemia, though there were a few with acute lymphocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. All were refractory to prior therapy, and most were over the age of 60 years.

The FDA mandated that the initial dose of CPX-351 be very low, so the researchers started with 3 units/m². One unit of CPX-351 is equal to 1 mg of cytarabine and 0.44 mg of daunorubicin. The researchers increased the dose gradually and monitored patients for responses and toxicities.

“We started low… and did not see responses at all until we got to 32 units,” Dr Feldman said. “By 101 [units], we saw multiple responses, and this is the dose that was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.”

This is because, at 134 units, the team observed 3 dose-limiting toxicities. They saw left ventricular systolic dysfunction and 1 patient with hypertensive crisis, although it was not clear whether this event was actually related to the drug.

“The main problem that we found was persistent cytopenias,” Dr Feldman said. “There was 1 patient in this cohort that took over 80 days to achieve a complete remission, meaning recovery of their platelets to 100,000 and neutrophils to 1000. We considered that the true dose-limiting toxicity.”

Apart from this myelosuppression, CPX-351 was well tolerated. Some patients did experience mucositosis, vomiting, and a skin rash, but the rash responded to corticosteroids. Importantly, patients did not experience alopecia.

With these promising results, researchers began a phase 2 study of CPX-351. They enrolled newly diagnosed leukemia patients between 60 and 75 years of age. Patients had high- or intermediate-risk disease.

They were randomized in a 2-to-1 fashion to receive either 100 units of CPX-351 or standard 3 + 7 therapy. The preliminary data from this study were presented at the ASH Annual Meeting in December. ![]()

Delivering drugs in combination requires a certain balance, a balance that ensures the drugs act synergistically. And researchers say they have struck the right balance with a new drug that combines two old standbys.

Daunorubicin and cytarabine (or ara-C) have proven activity against acute leukemia. However, neither of the drugs has elicited impressive survival rates when given alone, according to Eric Feldman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a presentation at Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium XXVII, Dr Feldman discussed a new agent comprised of the two drugs that he theorizes will prove more effective than either drug alone.

“When you combine different combinations of cytarabine and daunorubicin, there are some ratios that, in fact, may be antagonistic or just additive,” Dr Feldman said. “But… there are some—particularly this 5-to-1 ara-C-to-daunorubicin—that may be synergistic. And the question is, how do you deliver to the leukemia cell this synergistic combination of drugs?”

For a long time, Dr Feldman said, scientists did not have the appropriate technology to accomplish that. But now they do, and they have made significant strides with the compound CPX-351.

“Basically, this is a liposomal combination of daunorubicin and ara-C,” Dr Feldman said. “But the unique feature is that it fixes a 5-to-1 molar ratio of ara-C with daunorubicin and delivers to the cell this ratio in this concentration.”

To test the tolerability and efficacy of this compound, researchers began a phase 1 trial of CPX-351. The majority of patients on the trial had acute myeloid leukemia, though there were a few with acute lymphocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. All were refractory to prior therapy, and most were over the age of 60 years.

The FDA mandated that the initial dose of CPX-351 be very low, so the researchers started with 3 units/m². One unit of CPX-351 is equal to 1 mg of cytarabine and 0.44 mg of daunorubicin. The researchers increased the dose gradually and monitored patients for responses and toxicities.

“We started low… and did not see responses at all until we got to 32 units,” Dr Feldman said. “By 101 [units], we saw multiple responses, and this is the dose that was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.”

This is because, at 134 units, the team observed 3 dose-limiting toxicities. They saw left ventricular systolic dysfunction and 1 patient with hypertensive crisis, although it was not clear whether this event was actually related to the drug.

“The main problem that we found was persistent cytopenias,” Dr Feldman said. “There was 1 patient in this cohort that took over 80 days to achieve a complete remission, meaning recovery of their platelets to 100,000 and neutrophils to 1000. We considered that the true dose-limiting toxicity.”

Apart from this myelosuppression, CPX-351 was well tolerated. Some patients did experience mucositosis, vomiting, and a skin rash, but the rash responded to corticosteroids. Importantly, patients did not experience alopecia.

With these promising results, researchers began a phase 2 study of CPX-351. They enrolled newly diagnosed leukemia patients between 60 and 75 years of age. Patients had high- or intermediate-risk disease.

They were randomized in a 2-to-1 fashion to receive either 100 units of CPX-351 or standard 3 + 7 therapy. The preliminary data from this study were presented at the ASH Annual Meeting in December. ![]()

Delivering drugs in combination requires a certain balance, a balance that ensures the drugs act synergistically. And researchers say they have struck the right balance with a new drug that combines two old standbys.

Daunorubicin and cytarabine (or ara-C) have proven activity against acute leukemia. However, neither of the drugs has elicited impressive survival rates when given alone, according to Eric Feldman, MD, of Weill Cornell Medical College.

In a presentation at Chemotherapy Foundation Symposium XXVII, Dr Feldman discussed a new agent comprised of the two drugs that he theorizes will prove more effective than either drug alone.

“When you combine different combinations of cytarabine and daunorubicin, there are some ratios that, in fact, may be antagonistic or just additive,” Dr Feldman said. “But… there are some—particularly this 5-to-1 ara-C-to-daunorubicin—that may be synergistic. And the question is, how do you deliver to the leukemia cell this synergistic combination of drugs?”

For a long time, Dr Feldman said, scientists did not have the appropriate technology to accomplish that. But now they do, and they have made significant strides with the compound CPX-351.

“Basically, this is a liposomal combination of daunorubicin and ara-C,” Dr Feldman said. “But the unique feature is that it fixes a 5-to-1 molar ratio of ara-C with daunorubicin and delivers to the cell this ratio in this concentration.”

To test the tolerability and efficacy of this compound, researchers began a phase 1 trial of CPX-351. The majority of patients on the trial had acute myeloid leukemia, though there were a few with acute lymphocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome. All were refractory to prior therapy, and most were over the age of 60 years.

The FDA mandated that the initial dose of CPX-351 be very low, so the researchers started with 3 units/m². One unit of CPX-351 is equal to 1 mg of cytarabine and 0.44 mg of daunorubicin. The researchers increased the dose gradually and monitored patients for responses and toxicities.

“We started low… and did not see responses at all until we got to 32 units,” Dr Feldman said. “By 101 [units], we saw multiple responses, and this is the dose that was considered the maximum-tolerated dose.”

This is because, at 134 units, the team observed 3 dose-limiting toxicities. They saw left ventricular systolic dysfunction and 1 patient with hypertensive crisis, although it was not clear whether this event was actually related to the drug.

“The main problem that we found was persistent cytopenias,” Dr Feldman said. “There was 1 patient in this cohort that took over 80 days to achieve a complete remission, meaning recovery of their platelets to 100,000 and neutrophils to 1000. We considered that the true dose-limiting toxicity.”

Apart from this myelosuppression, CPX-351 was well tolerated. Some patients did experience mucositosis, vomiting, and a skin rash, but the rash responded to corticosteroids. Importantly, patients did not experience alopecia.

With these promising results, researchers began a phase 2 study of CPX-351. They enrolled newly diagnosed leukemia patients between 60 and 75 years of age. Patients had high- or intermediate-risk disease.

They were randomized in a 2-to-1 fashion to receive either 100 units of CPX-351 or standard 3 + 7 therapy. The preliminary data from this study were presented at the ASH Annual Meeting in December. ![]()

Make The Diagnosis

A 51 year-old-male presented with asymptomatic violaceous, indurated plaques on his left and right cheeks. He also had follicular plugging in the right ear. What’s your diagnosis?

Images courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Panniculitis

Lupus panniculitis, or lupus profundus, represents 2%-3% of all patients with lupus erythematosus. It most commonly occurs in adults aged 20-60. Patients present with tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that tend to develop on the face, upper outer arms, shoulders, hips, and trunk. The distal extremities are usually spared. The overlying skin can show features of chronic cutaneous lupus including scaling, follicular plugging, atrophy, dyspigmentation, telangiectasias, and ulceration.

Histopathology reveals a primarily lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells. One characteristic feature is hyalin necrosis of fat lobules that can extend into the septa.

Treatment options include sunscreen, potent topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, systemic steroids (in initial phases of disease), dapsone, cyclophosphamide, and thalidomide. This patient was treated with thalidomide, which resulted in improvement of his lesions.

This case was first presented at Maryland Derm, at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, by Dr. Bilu Martin and Dr. Anthony Gaspari.

Image courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Histology shows a lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells.

A 51 year-old-male presented with asymptomatic violaceous, indurated plaques on his left and right cheeks. He also had follicular plugging in the right ear. What’s your diagnosis?

Images courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Panniculitis

Lupus panniculitis, or lupus profundus, represents 2%-3% of all patients with lupus erythematosus. It most commonly occurs in adults aged 20-60. Patients present with tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that tend to develop on the face, upper outer arms, shoulders, hips, and trunk. The distal extremities are usually spared. The overlying skin can show features of chronic cutaneous lupus including scaling, follicular plugging, atrophy, dyspigmentation, telangiectasias, and ulceration.

Histopathology reveals a primarily lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells. One characteristic feature is hyalin necrosis of fat lobules that can extend into the septa.

Treatment options include sunscreen, potent topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, systemic steroids (in initial phases of disease), dapsone, cyclophosphamide, and thalidomide. This patient was treated with thalidomide, which resulted in improvement of his lesions.

This case was first presented at Maryland Derm, at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, by Dr. Bilu Martin and Dr. Anthony Gaspari.

Image courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Histology shows a lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells.

A 51 year-old-male presented with asymptomatic violaceous, indurated plaques on his left and right cheeks. He also had follicular plugging in the right ear. What’s your diagnosis?

Images courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Diagnosis: Lupus Erythematosus Panniculitis

Lupus panniculitis, or lupus profundus, represents 2%-3% of all patients with lupus erythematosus. It most commonly occurs in adults aged 20-60. Patients present with tender subcutaneous nodules and plaques that tend to develop on the face, upper outer arms, shoulders, hips, and trunk. The distal extremities are usually spared. The overlying skin can show features of chronic cutaneous lupus including scaling, follicular plugging, atrophy, dyspigmentation, telangiectasias, and ulceration.

Histopathology reveals a primarily lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells. One characteristic feature is hyalin necrosis of fat lobules that can extend into the septa.

Treatment options include sunscreen, potent topical and intralesional corticosteroids, antimalarials, systemic steroids (in initial phases of disease), dapsone, cyclophosphamide, and thalidomide. This patient was treated with thalidomide, which resulted in improvement of his lesions.

This case was first presented at Maryland Derm, at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, by Dr. Bilu Martin and Dr. Anthony Gaspari.

Image courtesy Dr. Donna Bilu Martin

Histology shows a lobular panniculitis with a marked predominance of lymphocytes and scattered plasma cells.

Incomplete Handoffs Hinder Patient Safety, Workflow

Nearly one in five hospitalists admitted uncertainty about transitional patient-care plans after service change, according to a report to be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The review, a single-institution study conducted at the University of Chicago, found 18% of respondents acknowledged uncertainty, 13% reported incomplete handoffs, and 16% attributed at least one “near miss” to incomplete communication. The study suggests that “investments in improving service change could not only improve patient safety, but they could improve hospitalists’ daily workflow,” says senior author Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, an academic hospitalist and associate director of Internal Medicine Residency at the University of Chicago.

Keiki Hinami, MD, MS, instructor of medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, says a unique facet of the report, titled “Understanding Communication During Hospitalist Service Changes: A Mixed Methods Study,” was the understanding by physicians that successful handoffs often involve more than a brief conversation or a pass-through of documentation.

“The outgoing doctor would come back to the incoming doctor and ask for updates, or they would solicit the incoming doctor for more information if they needed it,” says Dr. Hinami, who was one of the study’s authors while employed as a clinical associate by University of Chicago. “The participants of our study naturally adopted a strategy acknowledging that one conversation is not usually sufficient.”

The study measured 60 service changes among 17 hospitalists on a non-teaching service from May to December 2007. Hospitalists who reported incomplete handoffs were more likely to report uncertainty about care plans (71% incomplete vs. 10% complete, P<0.01), discovery of missing information (71% vs. 24%, P=0.01), and near misses/adverse events (57% vs. 10%, P<0.01).

Dr. Arora says work is under way to develop educational programs and evaluation tools to train hospitalists and others to improve service change handoffs.

“How do you teach people to communicate only pertinent information?” Dr. Hinami says. “That’s really a difficult challenge. Even though handoffs are something we do every day, most people have never had any formal training in communicating that.”

Nearly one in five hospitalists admitted uncertainty about transitional patient-care plans after service change, according to a report to be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The review, a single-institution study conducted at the University of Chicago, found 18% of respondents acknowledged uncertainty, 13% reported incomplete handoffs, and 16% attributed at least one “near miss” to incomplete communication. The study suggests that “investments in improving service change could not only improve patient safety, but they could improve hospitalists’ daily workflow,” says senior author Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, an academic hospitalist and associate director of Internal Medicine Residency at the University of Chicago.

Keiki Hinami, MD, MS, instructor of medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, says a unique facet of the report, titled “Understanding Communication During Hospitalist Service Changes: A Mixed Methods Study,” was the understanding by physicians that successful handoffs often involve more than a brief conversation or a pass-through of documentation.

“The outgoing doctor would come back to the incoming doctor and ask for updates, or they would solicit the incoming doctor for more information if they needed it,” says Dr. Hinami, who was one of the study’s authors while employed as a clinical associate by University of Chicago. “The participants of our study naturally adopted a strategy acknowledging that one conversation is not usually sufficient.”

The study measured 60 service changes among 17 hospitalists on a non-teaching service from May to December 2007. Hospitalists who reported incomplete handoffs were more likely to report uncertainty about care plans (71% incomplete vs. 10% complete, P<0.01), discovery of missing information (71% vs. 24%, P=0.01), and near misses/adverse events (57% vs. 10%, P<0.01).

Dr. Arora says work is under way to develop educational programs and evaluation tools to train hospitalists and others to improve service change handoffs.

“How do you teach people to communicate only pertinent information?” Dr. Hinami says. “That’s really a difficult challenge. Even though handoffs are something we do every day, most people have never had any formal training in communicating that.”

Nearly one in five hospitalists admitted uncertainty about transitional patient-care plans after service change, according to a report to be published in this month’s Journal of Hospital Medicine.

The review, a single-institution study conducted at the University of Chicago, found 18% of respondents acknowledged uncertainty, 13% reported incomplete handoffs, and 16% attributed at least one “near miss” to incomplete communication. The study suggests that “investments in improving service change could not only improve patient safety, but they could improve hospitalists’ daily workflow,” says senior author Vineet Arora, MD, MAPP, an academic hospitalist and associate director of Internal Medicine Residency at the University of Chicago.

Keiki Hinami, MD, MS, instructor of medicine in the Division of Hospital Medicine at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, says a unique facet of the report, titled “Understanding Communication During Hospitalist Service Changes: A Mixed Methods Study,” was the understanding by physicians that successful handoffs often involve more than a brief conversation or a pass-through of documentation.

“The outgoing doctor would come back to the incoming doctor and ask for updates, or they would solicit the incoming doctor for more information if they needed it,” says Dr. Hinami, who was one of the study’s authors while employed as a clinical associate by University of Chicago. “The participants of our study naturally adopted a strategy acknowledging that one conversation is not usually sufficient.”

The study measured 60 service changes among 17 hospitalists on a non-teaching service from May to December 2007. Hospitalists who reported incomplete handoffs were more likely to report uncertainty about care plans (71% incomplete vs. 10% complete, P<0.01), discovery of missing information (71% vs. 24%, P=0.01), and near misses/adverse events (57% vs. 10%, P<0.01).

Dr. Arora says work is under way to develop educational programs and evaluation tools to train hospitalists and others to improve service change handoffs.

“How do you teach people to communicate only pertinent information?” Dr. Hinami says. “That’s really a difficult challenge. Even though handoffs are something we do every day, most people have never had any formal training in communicating that.”

Avoid Social Networking Pitfalls

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

Although Web sites like Facebook, Linked In, and Ning are touted as valuable tools for social and professional networking, if users aren’t careful, career-related catastrophes can occur. It bears repeating that no online activity is anonymous, especially with more and more healthcare employers and recruiters visiting these sites to learn about job candidates, says Roberta Renaldy, a senior staffing specialist at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“They’re becoming your resume before your resume,” Renaldy says of social networking sites.

To keep career opportunities open, hospitalists should avoid dishing out “digital dirt”—aka put-downs—about other people, she says. Vulgarity, unsavory photos, incorrect spelling and grammar, angry online disputes, and dispensing medical advice also are taboo. Even strong points of view on controversial issues can run hospitalists the risk of getting passed over for a job or promotion.

“Someone might be willing to take this risk, but I encourage people to really think before they express their opinions,” Renaldy says.

On the flip side, hospitalists should create a personal brand that’s compelling and consistent across their social networking profiles, says E. Chandlee Bryan, a certified career coach at the firm Best Fit Forward in New York City. Be accurate about expertise and keep visitors interested by providing constant career updates, she says. Always thank network contacts for the slightest bit of advice, and don’t hesitate to offer others help, Bryan suggests.

Renaldy emphasizes the old-fashioned approach. “Using the Internet is a way to spark a networking relationship, but many times it doesn’t develop the relationship,” she says. “Nothing replaces face-to-face contact in furthering your professional career.”

Dr. Hospitalist

“Hospitalism” Isn’t the Same as HM

If hospitalists are doctors who provide care to hospitalized patients, is the correct term for the care they provide “hospitalism”?

P. Doherty, DO

Fort Collins, Colo.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I am of the belief that the correct term for the general medical care of hospitalized patients is “hospital medicine.” Hospitalism is a term I’ve heard used interchangeably with hospital medicine, but I do not believe it accurately describes the field of medicine practiced by hospitalists.

The dictionary, and online resources like Wikipedia, describes “hospitalism” as a medical condition suffered by children who were “institutionalized for long periods and deprived of substitute maternal care.” This term was first described in the late 1800s and popularized by psychotherapist Rene Spitz in 1945.1

Lee Goldman, MD, and Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, coined the term “hospitalist” in a landmark 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article. Dr. Goldman describes hospitalism as “[a] variety of iatrogenic maladies that were acquired by hospitalized patients and that often were more deadly than the admitting condition itself.” In fact, he described hospitalists as “a cure for hospitalism.”2

I had never heard of the term hospitalism and did not understand its definition before I became a hospitalist. As a hospitalist, I prefer to practice hospital medicine.

Don’t Give Up on Hand-Hygiene Compliance

I am the director of a hospitalist group. How do I convince my colleagues to wash their hands?

B. Hunter, MD

Dr. Hospitalist responds: Dr. Hunter, don’t feel discouraged. You are not alone. Appropriate hand hygiene in the hospital setting is a difficult nut to crack. In some ways, I liken hand-washing noncompliance to smoking or eating junk food: We know that it is bad for us. None of us dispute the facts. There is plenty of research to support the fact that smoking causes chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer; junk food causes obesity, which leads to heart disease and other ailments. But the truth of the matter is that many of us have a hard time resisting cigarettes and greasy burgers.

Hand hygiene is no different. It’s habitual. If it is not part of your routine, cleaning your hands before and after you enter a patient’s hospital room is time-consuming. But the truth remains: There is so much at stake.

Setting cost aside, hospital-acquired infections are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality. We know hand hygiene works. We also know that it is the right thing to do. If any of us were hospitalized, would we want our providers to clean their hands before examining us?

If the hospital where you work is like his or mine, hand-cleanser dispensers are conveniently located near the entry to every patient room. Signs urging compliance are plastered all over the place. The rules are clearly outlined and the rationale thoughtfully explained. Despite that fact, some providers, doctors, nurses, and others simply choose to ignore all the facts and reminders.

Some medical leaders believe hand-hygiene noncompliance is a medical error, and rogue providers should be punished for ignoring patient-safety measures. I agree. If your institution does not yet have a hand-hygiene program in place, it is incumbent on you and the hospital to institute one. If you have a program and providers ignore the rules, it is time to monitor compliance and punish the individuals who are putting our patients’ well-being at risk. TH

References

- Crandall FM. Hospitalism. Neonatology on the Web site. Available at: www.neonatology.org/classics/crandall.html. Accessed Sept. 12, 2009.

- Goldman L. Hospitalists as cure for hospitalism. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2003;114:37-48.

“Hospitalism” Isn’t the Same as HM

If hospitalists are doctors who provide care to hospitalized patients, is the correct term for the care they provide “hospitalism”?

P. Doherty, DO

Fort Collins, Colo.

Dr. Hospitalist responds: I am of the belief that the correct term for the general medical care of hospitalized patients is “hospital medicine.” Hospitalism is a term I’ve heard used interchangeably with hospital medicine, but I do not believe it accurately describes the field of medicine practiced by hospitalists.

The dictionary, and online resources like Wikipedia, describes “hospitalism” as a medical condition suffered by children who were “institutionalized for long periods and deprived of substitute maternal care.” This term was first described in the late 1800s and popularized by psychotherapist Rene Spitz in 1945.1

Lee Goldman, MD, and Robert Wachter, MD, FHM, coined the term “hospitalist” in a landmark 1996 New England Journal of Medicine article. Dr. Goldman describes hospitalism as “[a] variety of iatrogenic maladies that were acquired by hospitalized patients and that often were more deadly than the admitting condition itself.” In fact, he described hospitalists as “a cure for hospitalism.”2

I had never heard of the term hospitalism and did not understand its definition before I became a hospitalist. As a hospitalist, I prefer to practice hospital medicine.

Don’t Give Up on Hand-Hygiene Compliance