User login

When Is GI Bleeding Prophylaxis Indicated in Hospitalized Patients?

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

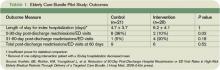

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

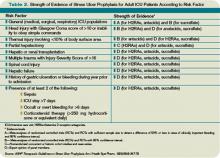

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.

Case

A 69-year-old man with Type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is admitted to the ICU with respiratory compromise related to community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), accompanied by delirium, hyperglycemia, and hypovolemia. He responds well to supportive, noninvasive ventilatory therapy, but develops positive stool occult blood testing during the second day in the ICU. Upon clinical improvement, you transfer him to the general medical floor. What is the best strategy for preventing clinically significant gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding during his hospitalization?

Background

Stress-related mucosal disease (SRMD) refers to superficial erosions or focal ulceration of the proximal gastrointestinal mucosa resulting from physiologic demand in acute illness. Multiple factors contribute to its development, including disruption of the protective mucosal barrier, splanchnic vasculature hypoperfusion, and release of inflammatory mediators.1,2 Increasing severity and number of lesions are associated with the propensity for stress-related mucosal bleeding (SRMB). Based on severity, GI hemorrhage can be defined as occult (detected on chemical testing), overt (grossly evident), or clinically important (overt with compromised hemodynamics or requiring transfusion).3

The majority of clinically significant GI bleeding events occur in critically ill patients. Although more than 75% of patients have endoscopic evidence of SRMD within 24 hours of ICU admission, lesions often resolve spontaneously as patients stabilize, and the average frequency of significant bleeding is only 6%. However, when present, SRMB in ICU patients increases the length of hospitalization, cost, and mortality rates.1,3 By contrast, significant GI bleeding occurs in less than 1% of inpatients without critical illness.4

While preventing clinically important bleeding in hospitalized patients is a crucial objective, current practice reflects significant stress ulcer phophylaxis (SUP) overutilization, with substantial economic impact and potential for harm. One in three patients takes antisecretory therapy (AST) upon admission.5 Additionally, SUP is prescribed in 32% to 54% of general medical inpatients, despite the low risk for SRMB. Importantly, these prophylactic agents are continued on discharge in more than half of these patients.6-9 Clinician prescribing practices potentially can set an unfounded standard of care for obligatory prophylaxis among inpatients.

Data for Clinical Decision-Making

Several studies report the risks for gastrointestinal hemorrhage related to acute illness. In a prospective study of 2,252 ICU patients, two independent predictors of clinically important, new-onset SRMB were identified: mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and coagulopathy (see Table 1). Of these risk factors, respiratory failure was present in virtually all patients with GI hemorrhage; only one patient had coagulopathy alone. Mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy was associated with a 4% risk of clinically important GI bleeding, whereas patients with neither symptom had a 0.1% risk.

Though GI bleeding was uncommon, mortality associated with bleeding was 49%, compared with 9% in the nonbleeding group. In the absence of one of these two risk factors, 900 ICU patients would need to be treated to prevent one clinically important GI bleeding event.3 Other studies identify an increased risk of GI bleeding in subsets of patients with trauma, thermal injury, and organ transplantation. Additional possible risk factors might include septic shock, glucocorticoid or NSAID use, renal or hepatic failure, and prior GI bleeding or ulcer.10 The likelihood of GI bleeding increases proportionate to the number of risk factors present.

Limited data for non-ICU patients demonstrate an increased bleeding risk in the presence of ischemic heart disease, chronic renal failure, mechanical ventilation, or prior ICU stay.11 One study of 17,707 general medical patients found a low overall incidence (0.4%) of overt or clinically important GI bleeding, mainly in patients treated with anticoagulants without a mortality difference related to bleeding events.4

The 1999 American Society of Health System Pharmacists (ASHP) Therapeutic Guidelines on Stress Ulcer Prophylaxis reviewed extensive data by level of evidence to identify clinical indicators of patients at higher risk (see Table 2, p. 31).10 The bottom line is that stress-related bleeding depends on the type and severity of illness. Independent risk factors for critically ill patients include mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. Stable general medical inpatients are at very low risk of clinically significant GI bleeding.

Clinical predictors help define patients at the greatest risk of SRMB. However, to be meaningful, SUP must improve clinical outcomes. Despite extensive studies on the efficacy of pharmacologic agents in the prevention of significant bleeding, several trials do not show a benefit of SUP over placebo, even in patients with major risk factors.4,12,13 Other independent studies and meta-analyses demonstrate that H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) prevent ICU bleeding, reducing events by approximately 50%.10 Of all the available prophylactic agents, H2RAs are FDA-approved for this use, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are likely as effective, and both are well-tolerated. However, data suggest that the use of AST is associated with C. difficile-associated disease, hip fracture, and pneumonia.

Outside of the ICU, there is no difference in de novo GI bleeding among general medical patients prescribed SUP. The ASHP guidelines thus conclude there is no indication for SUP in stable, general medical inpatients.10

Prevention Strategies

A subset of seriously ill patients has an increased risk for significant SRMB, but ideal prevention is not well-defined. As noted in the ASHP guidelines, “prophylaxis does not necessarily prevent bleeding in patients with documented risk factors, and the efficacy of prophylaxis varies in different patient populations.”

Given the effect of SRMB, it is reasonable to provide preventive agents to subgroups of critically ill patients with significant risk factors of mechanical ventilation for more than 48 hours and underlying coagulopathy. Studies report that judicious SUP prescription when these risks are present reduces cost without increasing morbidity or mortality in the ICU.14

Back to the Case

Our case addresses a patient in both an ICU and general medical setting. Based on his lack of risk factors for significant GI bleeding, SUP was not indicated. In this case, the patient improved. Had he developed ventilatory failure requiring intubation, the risk of clinically important GI bleeding would have approached 4%, and H2RA prophylaxis would have been recommended. Although the optimal length of prophylaxis is unknown, SUP likely can be discontinued on transfer out of the ICU, as clinical stability is associated with a substantially lower risk of clinically important bleeding.

Bottom Line

Literature supports the limited use of SUP in hospitalized medical inpatients. SUP can be reserved for critically-ill patients with major risk factors, including prolonged mechanical ventilation or coagulopathy. TH

Dr. Wright is associate professor and head of the section of hospital medicine of the Department of Medicine at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

References

1. Stollman N, Metz D. Pathophysiology and prophylaxis of stress ulcer in intensive care unit patients. J Crit Care. 2005;20:35-45.

2. Fennerty M. Pathophysiology of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the critically ill patient: rationale for the therapeutic benefits of acid suppression. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(6 Suppl):S351-S355.

3. Cook D, Fuller H, Guyatt G, et al. Risk factors for gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients. New Engl J Med. 1994;330:377-381.

4. Qadeer M, Richter J, Brotman D. Hospital-acquired gastrointestinal bleeding outside the critical care unit: risk factors, role of acid suppression, and endoscopy findings. J Hosp Med. 2006;1:13-20.

5. Heidelbaugh J, Inadomi J. Magnitude and economic impact of inappropriate use of stress ulcer prophylaxis in non-ICU hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2200-2205.

6. Nardino R, Vender R, Herbert P. Overuse of acid-suppressive therapy in hospitalized patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3118-3122.

7. Pham C, Regal R, Bostwick T, Knauf K. Acid suppressive therapy use on an inpatient internal medicine service. Ann Pharmacother. 2006;40:1261-1266.

8. Hwang K, Kolarov S, Cheng L, Griffith R. Stress ulcer prophylaxis for non-critically ill patients on a teaching service. J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:716-721.

9. Wohlt P, Hansen L, Fish J. Inappropriate continuation of stress ulcer prophylactic therapy after discharge. Ann Pharmachother. 2007;41:1611-1616.

10. ASHP therapeutic guidelines on stress ulcer prophylaxis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:347-379.

11. Janicki T, Stewart S. Stress-ulcer prophylaxis for general medical patients: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2007;2:86-92.

12. Faisy C, Guerot E, Diehl J, Iftimovici E, Fagon J. Clinically significant gastrointestinal bleeding in critically ill patients with and without stress-ulcer prophylaxis. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1306-1313.

13. Kantorova I, Svoboda P, Scheer P, et al. Stress ulcer prophylaxis in critically ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:757-761.

14. Coursol C, Sanzari S. Impact of stress ulcer prophylaxis algorithm study. Ann Pharmacother. 2005;39:810-816.

Misunderstood Modifiers

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Modifiers are two-digit representations used in conjunction with a service or procedure code (e.g., 99233-25) during claim submission to alert payors that the service or procedure was performed under a special circumstance. Modifiers can:

- Identify body areas;

- Distinguish multiple, separately identifiable services;

- Identify reduced or multiple services of the same or a different nature; or

- Categorize unusual events surrounding a particular service.1

Many questions arise over appropriate modifier use. Hospitalist misconceptions typically involve surgical comanagement or multiple services on the same day. Understanding when to use modifiers is imperative for proper claim submission and reimbursement.

Multiple Visits

Most hospitalists know payors allow reimbursement for only one visit per specialty, per patient, per day; however, some payors further limit coverage to a single service (i.e., a visit or a procedure) unless physician documentation demonstrates a medical necessity for each billed service. When two visits are performed on the same date by the same physician, or by two physicians of the same specialty within the same group, only one cumulative service should be reported.2

Consideration of two notes during visit-level selection does not authorize physicians to report a higher visit level (e.g., 99233 for two notes instead of 99232 for one note). If the cumulative documentation does not include the necessary elements of history, exam, or medical decision-making that are associated with 99233, the physician must report the lower visit level that accurately reflects the content of the progress note (for more information on documentation guidelines, visit www.cms.hhs.gov/MLNEdWebGuide/25_EMDOC.asp).

One exception to this “single cumulative service” rule occurs when a physician provides a typical inpatient service (e.g., admission or subsequent hospital care) for chronic obstructive bronchitis with acute exacerbation (diagnosis code 491.21) early in the day, and later the patient requires a second, more intense encounter for acute respiratory distress (diagnosis code 518.82) that meets the definition of critical care (99291). In this scenario, the physician is allowed to report both services on the same date, appending modifier 25 to the initial service (i.e., 99233-25) because each service was performed for distinct reasons.

If different physicians in the same provider group and specialty provided the initial and follow-up services, each physician reports the corresponding service in their own name with modifier 25 appended to the subsequent hospital care service (as above). Please note that physicians may not report both services if critical care is the initial service of the day. In this latter scenario, the physician reports critical-care codes (99291, 99292) for all of his or other group members’ encounters provided in one calendar day.3

Visits and Procedures

When a physician bills for a procedure and a visit (inpatient or outpatient) on the same day, most payors “bundle” the visit payment into that of the procedure. Some payors do provide separate payment for the visit, if the service is separately identifiable from the procedure (i.e., performed for a separate reason). To electronically demonstrate this on the claim form, the physician appends modifier 25 to the visit. Although not required, it is strongly suggested that, when possible, the primary diagnosis for the visit differs from the one used with the procedure. This will further distinguish the services. However, different diagnoses may not be possible when the physician evaluates the patient and decides, during the course of the evaluation, that a procedure is warranted. In this case, the physician may only have a single diagnosis to list with the procedure and the visit.

Payors may request documentation prior to payment to ensure that the visit is not associated with the required preprocedure history and physical. Modifier 57 is not to be confused with modifier 25. Modifier 57 indicates that the physician made the decision for “surgery” during the visit, but this modifier is used with preprocedural visits involving major surgical procedures (i.e., procedures associated with 90-day global periods). Since hospitalists do not perform major surgical procedures, they would not use this modifier with preprocedural visits.

Keep in mind that this “bundling” concept only applies when same-day visits and procedures are performed by the same physician or members of the same provider group with the same specialty designation. In other words, hospitalist visits are typically considered separate from procedures performed by a surgeon, and there is no need to append a modifier to visits on the same day as the surgeon’s procedure. The surgeon’s packaged payment includes preoperative visits after the decision for surgery is made beginning one day prior to surgery, and postoperative visits by the surgeon related to recovery from surgery, postoperative pain management, and discharge care.4 The surgeon is entitled to the full global payment if he provides the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative management.

If the surgeon relinquishes care and formally transfers the preoperative or postoperative management to another physician not associated with the surgical group, the other physician may bill for his portion of the perioperative management by appending modifier 56 (preop) or 55 (postop) to the procedure code. Unfortunately, the hospitalist is subject to the surgeon’s claim reporting. If the surgeon fails to solely report his intraoperative management (modifier 54 appended to the procedure code), the surgeon receives the full packaged payment. The payor will deny the hospitalist’s claim.

The payor is unlikely to retrieve money from one provider to pay another provider, unless a pattern of inappropriate claim submission is detected. Surgical intraoperative responsibilities are not typically reassigned to other provider groups unless special circumstances occur (e.g., geographical restrictions). Therefore, if the surgeon does not relinquish care but merely wants the hospitalist to assist in medical management, the hospitalist reports his medically necessary services with the appropriate inpatient visit code (subsequent hospital care, 99231-99233). TH

Carol Pohlig is a billing and coding expert with the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center, Philadelphia. She is on the faculty of SHM’s inpatient coding course.

References

1. Holmes A. Appropriate Use of Modifiers In: Coding for Chest Medicine 2009. Northbrook, Ill.: American College of Chest Physicians; 2008:273-282.

2. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

3. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare claims processing manual. CMS Web site. Available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/manuals/downloads/clm104c12.pdf. Accessed Feb. 10, 2009.

4. Pohlig, C. Sort out surgical cases. The Hospitalist. 2008;12(8):19.

Armed with HM Knowledge

Many physicians use traditional practice as their stepping stone to a hospitalist career. David M. Grace, MD, took a far more unconventional path.

He served as a combat medic in the Army National Guard, joined a disaster medical assistance team at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and volunteered to help the American Red Cross in times of crisis—all before entering medical school.

Dr. Grace became a hospitalist in 2002, and now serves as hospitalist division area medical officer for The Schumacher Group, a staffing and consulting firm in Lafayette, La., that hires physicians as independent contractors to work in hospitals across the country.

But 21 years into his healthcare career, he continues to seek opportunities that offer the same two rewards: “I want to be filled with Adrenalin,” he says, “but I still want to use my brains.”

—David M. Grace, MD, The Schumacher Group, Lafayette, La.

Question: Given your varied background, how did you wind up becoming a hospitalist?

Answer: My predoctoring resume reads like a fast track of becoming an emergency physician. In residency, I had heard the term “hospitalist.” I knew I liked dealing with sick patients. Emergency departments act as a fairly good filter, and anyone who gets through and upstairs truly is a sick patient. I figured if I were a hospitalist, all my patients would be sick, as opposed to just some. That really drove me to hospital medicine.

Q: You founded your own hospitalist company in 2005, but within two years, you joined The Schumacher Group. Why did you make the switch?

A: With the speed with which hospital medicine is growing, I thought if I could tap into their resources and infrastructure … I’d be able to do things I couldn’t do in my own group for years, if not decades. I really thought I would be able to impact a far larger portion of patient lives with them than I could in my own smaller, somewhat homemade group.

Q: When The Schumacher Group formed, it focused on emergency departments. In 2007, it launched a hospitalist service. What’s the benefit?

A: If you put good hospitalist systems under the same umbrella as good emergency department systems, you can do things to boost the synergy between the two disciplines and improve patient care. In the facilities where we’re managing both the ED and the hospitalists, we can effect patient care from the moment the patient swings through the ambulance bay doors until the moment they are discharged.

Q: How successful has the HM effort been?

A: The hospitalist side, by the end of the year, will have about 20 to 25 practices up and running, with growth in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 practices a year expected to come on line.

Q: What are the advantages to a private corporation setup?

A: At the end of the day, doctors need to be patient-care advocates. But if you are employed by a hospital, they sign your check. When push comes to shove on a quality issue, I think there’s a tendency not to shove as hard when the person you’re shoving is the person employing you.

Q: Could this approach be the wave of the future?

A: I think so. It goes back to the idea of focusing all of your resources into one small area, such as hospital medicine or inpatient medicine, so there’s far fewer distractions than for a hospital that runs its own hospitalist program. We saw that in the 1970s, when hospitals were buying primary-care practices left and right. They realized they didn’t have the skills or the resources to make that effective, and they rapidly divested.

Q: Most doctors at the executive level of The Schumacher Group—including yourself—still practice medicine. Why is that so integral to the mission?

A: When I served in the military, the best officers I served under were officers who had been enlisted men earlier in their career. The same follows suit in hospital medicine. When I make an administrative decision, it can affect thousands of patient lives tomorrow. I can mentally track the effects of my decision all the way back to how it will affect the patient laying in the bed. If you’re not having that constantly reinforced by seeing patients, it’s very easy to lose track of it, and that has such a profound effect on patient care.

Q: SHM recently designated you one of the inaugural “Fellows in Hospital Medicine.” What is the biggest reward of a HM career?

A: For me, there are two. One is the ability to see the fruits of your labor much more rapidly than in the outpatient world. I can have a patient in bed in front of me actively dying and watch them a week later walk out of hospital in good condition. That’s a very different timetable than the outpatient world, when you may put a patient on all the right medicines to reduce the risk of a heart attack and, over 60 years, watch them not have a heart attack. The other thing I find very rewarding is the amount of measurements and data collected on what we do. We get feedback ranging from patient satisfaction scores to referring physician scores to readmission rates to data that shows if we are able to get patients better outcomes at lower costs. You just don’t get that type of feedback in many other fields.

Q: What is the greatest challenge facing the profession?

A: One of the biggest is the supply and demand mismatch. Right now, one of the hardest jobs is a hospitalist recruiter. With every physician having five to 10 open job offers …recruiting is difficult, and recruiting the right physician is extremely difficult.

Q: How can that be addressed?

A: One way is to be efficient. Can we see more patients in the same amount of time with no decrease in quality? For us, it involves the use of what we call a practice coordinator. It’s an employee of The Schumacher Group who is located in the individual hospital who does everything from assisting with managing the practice to answering telephone calls. This really allows us to help us organize our time better, so we don’t get bogged down in nonclinical work. Every minute spent on the phone with an insurance company or home health agency is a minute not spent at the bedside. Another way is expanding the use of midlevel providers. The key is not to use them as a replacement for a physician, but as an assistant to the physician—again, to boost capacity.

Q: How did your background with the military, FEMA, and the Red Cross prepare you for what you’re doing now?

A: Business as usual is very difficult to do in a chaotic environment, so I began to appreciate the importance of systems. If you’re relying on an individual and that individual leaves, your entity is in trouble. If you put good systems into place, you’re not so reliant on any one individual. Systems can function long after any individual doctor has come and gone. In the world of hospitalists—where there’s still fairly high turnover, being a young field and there are many opportunities—it’s imperative the systems approach is taken. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Many physicians use traditional practice as their stepping stone to a hospitalist career. David M. Grace, MD, took a far more unconventional path.

He served as a combat medic in the Army National Guard, joined a disaster medical assistance team at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and volunteered to help the American Red Cross in times of crisis—all before entering medical school.

Dr. Grace became a hospitalist in 2002, and now serves as hospitalist division area medical officer for The Schumacher Group, a staffing and consulting firm in Lafayette, La., that hires physicians as independent contractors to work in hospitals across the country.

But 21 years into his healthcare career, he continues to seek opportunities that offer the same two rewards: “I want to be filled with Adrenalin,” he says, “but I still want to use my brains.”

—David M. Grace, MD, The Schumacher Group, Lafayette, La.

Question: Given your varied background, how did you wind up becoming a hospitalist?

Answer: My predoctoring resume reads like a fast track of becoming an emergency physician. In residency, I had heard the term “hospitalist.” I knew I liked dealing with sick patients. Emergency departments act as a fairly good filter, and anyone who gets through and upstairs truly is a sick patient. I figured if I were a hospitalist, all my patients would be sick, as opposed to just some. That really drove me to hospital medicine.

Q: You founded your own hospitalist company in 2005, but within two years, you joined The Schumacher Group. Why did you make the switch?

A: With the speed with which hospital medicine is growing, I thought if I could tap into their resources and infrastructure … I’d be able to do things I couldn’t do in my own group for years, if not decades. I really thought I would be able to impact a far larger portion of patient lives with them than I could in my own smaller, somewhat homemade group.

Q: When The Schumacher Group formed, it focused on emergency departments. In 2007, it launched a hospitalist service. What’s the benefit?

A: If you put good hospitalist systems under the same umbrella as good emergency department systems, you can do things to boost the synergy between the two disciplines and improve patient care. In the facilities where we’re managing both the ED and the hospitalists, we can effect patient care from the moment the patient swings through the ambulance bay doors until the moment they are discharged.

Q: How successful has the HM effort been?

A: The hospitalist side, by the end of the year, will have about 20 to 25 practices up and running, with growth in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 practices a year expected to come on line.

Q: What are the advantages to a private corporation setup?

A: At the end of the day, doctors need to be patient-care advocates. But if you are employed by a hospital, they sign your check. When push comes to shove on a quality issue, I think there’s a tendency not to shove as hard when the person you’re shoving is the person employing you.

Q: Could this approach be the wave of the future?

A: I think so. It goes back to the idea of focusing all of your resources into one small area, such as hospital medicine or inpatient medicine, so there’s far fewer distractions than for a hospital that runs its own hospitalist program. We saw that in the 1970s, when hospitals were buying primary-care practices left and right. They realized they didn’t have the skills or the resources to make that effective, and they rapidly divested.

Q: Most doctors at the executive level of The Schumacher Group—including yourself—still practice medicine. Why is that so integral to the mission?

A: When I served in the military, the best officers I served under were officers who had been enlisted men earlier in their career. The same follows suit in hospital medicine. When I make an administrative decision, it can affect thousands of patient lives tomorrow. I can mentally track the effects of my decision all the way back to how it will affect the patient laying in the bed. If you’re not having that constantly reinforced by seeing patients, it’s very easy to lose track of it, and that has such a profound effect on patient care.

Q: SHM recently designated you one of the inaugural “Fellows in Hospital Medicine.” What is the biggest reward of a HM career?

A: For me, there are two. One is the ability to see the fruits of your labor much more rapidly than in the outpatient world. I can have a patient in bed in front of me actively dying and watch them a week later walk out of hospital in good condition. That’s a very different timetable than the outpatient world, when you may put a patient on all the right medicines to reduce the risk of a heart attack and, over 60 years, watch them not have a heart attack. The other thing I find very rewarding is the amount of measurements and data collected on what we do. We get feedback ranging from patient satisfaction scores to referring physician scores to readmission rates to data that shows if we are able to get patients better outcomes at lower costs. You just don’t get that type of feedback in many other fields.

Q: What is the greatest challenge facing the profession?

A: One of the biggest is the supply and demand mismatch. Right now, one of the hardest jobs is a hospitalist recruiter. With every physician having five to 10 open job offers …recruiting is difficult, and recruiting the right physician is extremely difficult.

Q: How can that be addressed?

A: One way is to be efficient. Can we see more patients in the same amount of time with no decrease in quality? For us, it involves the use of what we call a practice coordinator. It’s an employee of The Schumacher Group who is located in the individual hospital who does everything from assisting with managing the practice to answering telephone calls. This really allows us to help us organize our time better, so we don’t get bogged down in nonclinical work. Every minute spent on the phone with an insurance company or home health agency is a minute not spent at the bedside. Another way is expanding the use of midlevel providers. The key is not to use them as a replacement for a physician, but as an assistant to the physician—again, to boost capacity.

Q: How did your background with the military, FEMA, and the Red Cross prepare you for what you’re doing now?

A: Business as usual is very difficult to do in a chaotic environment, so I began to appreciate the importance of systems. If you’re relying on an individual and that individual leaves, your entity is in trouble. If you put good systems into place, you’re not so reliant on any one individual. Systems can function long after any individual doctor has come and gone. In the world of hospitalists—where there’s still fairly high turnover, being a young field and there are many opportunities—it’s imperative the systems approach is taken. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Many physicians use traditional practice as their stepping stone to a hospitalist career. David M. Grace, MD, took a far more unconventional path.

He served as a combat medic in the Army National Guard, joined a disaster medical assistance team at the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and volunteered to help the American Red Cross in times of crisis—all before entering medical school.

Dr. Grace became a hospitalist in 2002, and now serves as hospitalist division area medical officer for The Schumacher Group, a staffing and consulting firm in Lafayette, La., that hires physicians as independent contractors to work in hospitals across the country.

But 21 years into his healthcare career, he continues to seek opportunities that offer the same two rewards: “I want to be filled with Adrenalin,” he says, “but I still want to use my brains.”

—David M. Grace, MD, The Schumacher Group, Lafayette, La.

Question: Given your varied background, how did you wind up becoming a hospitalist?

Answer: My predoctoring resume reads like a fast track of becoming an emergency physician. In residency, I had heard the term “hospitalist.” I knew I liked dealing with sick patients. Emergency departments act as a fairly good filter, and anyone who gets through and upstairs truly is a sick patient. I figured if I were a hospitalist, all my patients would be sick, as opposed to just some. That really drove me to hospital medicine.

Q: You founded your own hospitalist company in 2005, but within two years, you joined The Schumacher Group. Why did you make the switch?

A: With the speed with which hospital medicine is growing, I thought if I could tap into their resources and infrastructure … I’d be able to do things I couldn’t do in my own group for years, if not decades. I really thought I would be able to impact a far larger portion of patient lives with them than I could in my own smaller, somewhat homemade group.

Q: When The Schumacher Group formed, it focused on emergency departments. In 2007, it launched a hospitalist service. What’s the benefit?

A: If you put good hospitalist systems under the same umbrella as good emergency department systems, you can do things to boost the synergy between the two disciplines and improve patient care. In the facilities where we’re managing both the ED and the hospitalists, we can effect patient care from the moment the patient swings through the ambulance bay doors until the moment they are discharged.

Q: How successful has the HM effort been?

A: The hospitalist side, by the end of the year, will have about 20 to 25 practices up and running, with growth in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 practices a year expected to come on line.

Q: What are the advantages to a private corporation setup?

A: At the end of the day, doctors need to be patient-care advocates. But if you are employed by a hospital, they sign your check. When push comes to shove on a quality issue, I think there’s a tendency not to shove as hard when the person you’re shoving is the person employing you.

Q: Could this approach be the wave of the future?

A: I think so. It goes back to the idea of focusing all of your resources into one small area, such as hospital medicine or inpatient medicine, so there’s far fewer distractions than for a hospital that runs its own hospitalist program. We saw that in the 1970s, when hospitals were buying primary-care practices left and right. They realized they didn’t have the skills or the resources to make that effective, and they rapidly divested.

Q: Most doctors at the executive level of The Schumacher Group—including yourself—still practice medicine. Why is that so integral to the mission?

A: When I served in the military, the best officers I served under were officers who had been enlisted men earlier in their career. The same follows suit in hospital medicine. When I make an administrative decision, it can affect thousands of patient lives tomorrow. I can mentally track the effects of my decision all the way back to how it will affect the patient laying in the bed. If you’re not having that constantly reinforced by seeing patients, it’s very easy to lose track of it, and that has such a profound effect on patient care.

Q: SHM recently designated you one of the inaugural “Fellows in Hospital Medicine.” What is the biggest reward of a HM career?

A: For me, there are two. One is the ability to see the fruits of your labor much more rapidly than in the outpatient world. I can have a patient in bed in front of me actively dying and watch them a week later walk out of hospital in good condition. That’s a very different timetable than the outpatient world, when you may put a patient on all the right medicines to reduce the risk of a heart attack and, over 60 years, watch them not have a heart attack. The other thing I find very rewarding is the amount of measurements and data collected on what we do. We get feedback ranging from patient satisfaction scores to referring physician scores to readmission rates to data that shows if we are able to get patients better outcomes at lower costs. You just don’t get that type of feedback in many other fields.

Q: What is the greatest challenge facing the profession?

A: One of the biggest is the supply and demand mismatch. Right now, one of the hardest jobs is a hospitalist recruiter. With every physician having five to 10 open job offers …recruiting is difficult, and recruiting the right physician is extremely difficult.

Q: How can that be addressed?

A: One way is to be efficient. Can we see more patients in the same amount of time with no decrease in quality? For us, it involves the use of what we call a practice coordinator. It’s an employee of The Schumacher Group who is located in the individual hospital who does everything from assisting with managing the practice to answering telephone calls. This really allows us to help us organize our time better, so we don’t get bogged down in nonclinical work. Every minute spent on the phone with an insurance company or home health agency is a minute not spent at the bedside. Another way is expanding the use of midlevel providers. The key is not to use them as a replacement for a physician, but as an assistant to the physician—again, to boost capacity.

Q: How did your background with the military, FEMA, and the Red Cross prepare you for what you’re doing now?

A: Business as usual is very difficult to do in a chaotic environment, so I began to appreciate the importance of systems. If you’re relying on an individual and that individual leaves, your entity is in trouble. If you put good systems into place, you’re not so reliant on any one individual. Systems can function long after any individual doctor has come and gone. In the world of hospitalists—where there’s still fairly high turnover, being a young field and there are many opportunities—it’s imperative the systems approach is taken. TH

Mark Leiser is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

The ABCs of CMS

Now, more than ever, major changes in the way healthcare is provided, measured, and paid for seem to be coming from a single source: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). From the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) to last summer’s Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, CMS has an ever-growing influence on U.S. healthcare.

Although it has published numerous articles about CMS and its policies, The Hospitalist has never offered an explanatory overview of one of the largest healthcare agencies in the world. In order to help hospitalists understand the policies, payments, and trends that affect them every day, we have prepared this CMS fact sheet.

Agency Background

CMS falls under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and is tasked primarily with administering the Medicare program and working in partnership with state governments to administer Medicaid and the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). CMS’ current mission is “to ensure effective, up-to-date healthcare coverage and to promote quality care for beneficiaries,” which is a more modern focus than when the Medicare and Medicaid programs were first signed into law in 1965. Those programs were created solely to provide healthcare coverage to Americans over the age of 65, as well as low-income children and people with certain disabilities.

CMS has grown in size and scope since its inception. “First and foremost, CMS is the largest single payor for healthcare in the United States,” says Patrick J. Torcson, MD, MMM, FACP, director of hospital medicine at St. Tammany Parish Hospital in Covington, La., and chair of SHM’s Performance and Standards Committee. Insurance companies model their coverage and fee schedules after CMS. “That makes it very important for reimbursement.”

Approximately 45 million Americans are Medicare beneficiaries, and CMS pays reimbursements for more than 90 million people through the Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP programs. Hospitalists treat so many of these beneficiaries that Dr. Torcson estimates CMS represents “at least a third” of the payor mix for most adult hospitalists. For hospitals, the percentage is larger: “For acute-care public hospitals, I’d estimate that Medicare is probably 50% of the payor mix,” Dr. Torcson says.

Part A and Part B

When a beneficiary is hospitalized, Medicare pays separately for hospital services (Part A) and physician services (Part B). Because of their unique role in the hospital, most hospitalists receive payment through both Medicare reimbursement plans. “Physicians are never paid under Part A, but most hospital medicine groups receive some subsidy from their hospital, and, of course, that money originally comes from Part A,” Dr. Torcson explains.

Medicare Part A reimbursement applies to inpatient care in hospitals, critical-access hospitals, and skilled nursing facilities. It does not apply to custodial or long-term care, but it does help cover hospice care and some home healthcare.

Medicare Part B covers medically necessary services and supplies. Most beneficiaries pay a premium to receive this coverage, which includes outpatient care, doctor services, physical or occupational therapists, and additional home healthcare. Part B also covers nonphysician services and procedures.

Part B reimbursement is dictated by the CMS Physician Fee Schedule, which is released every year in the agency’s Final Rule (see “Medicare Modifications,” January 2009, p. 17). You may recall the scramble each of the past three years to urge Congress to avert a 10.6% cut in Part B payments to doctors.

“From the physician side, we still have this …hanging over our heads,” Dr. Torcson says. “Every year, we manage to avert a 10% cut in pay. Now we only have until this summer to block that cut again, unless there is a complete reform of how Part B is reimbursed.”

Congress Calls the Shots

Although CMS administers the Medicare programs and writes the checks, Congress sets the agency’s budgets and directives. Congress must pass into law every CMS initiative, including the Physician Compare Web site that publicizes PQRI data and reimbursement for follow-up inpatient telehealth consultations.

Congress is advised on healthcare issues by an independent agency, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC). The 17-member MedPAC board advises Congress about payments to providers in Medicare’s traditional fee-for-service program as well as private health plans participating in Medicare. MedPAC also is tasked with analyzing access to care, quality of care, and other issues relating to Medicare. “They’re not a governing board,” Dr. Torcson says. “MedPAC clearly functions as an advisory panel. The final authority is through Congress.”

CMS Sets the Direction

In addition to putting money in hospitalists’ pockets, CMS plays an important role in setting nationwide trends for healthcare payment and policies. As the largest and most powerful payor in the U.S., the agency often acts as a model for other payors—namely, private insurance companies.

Dr. Torcson points to two historic changes in payment reform: “By 1983, there was a turning point when hospitals began getting payment through the DRG [diagnosis-related group] system. Private payors started following along.” And when the Medicare physician fee schedule was introduced in the 1990s, “private payors began basing their physician payments on the physician fee schedule.”

Private payors are watching CMS initiatives (e.g., PQRI and value-based purchasing) to see how physician payment develops in the future.

“CMS is powerful and it’s going to become more so,” Dr. Torcson predicts. “It’s going to continue to be a model of healthcare reform, with its focus on aligning quality and cost in concepts like value-based purchasing.”

For the time being, no one knows the exact shape U.S. healthcare reform will take or how fast it might happen. But one thing is certain: CMS will be at the forefront of changes that have a major effect on how hospitalists work, as well as how they are compensated. TH

Jane Jerrard is a medical writer based in Chicago.

Now, more than ever, major changes in the way healthcare is provided, measured, and paid for seem to be coming from a single source: the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). From the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) to last summer’s Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, CMS has an ever-growing influence on U.S. healthcare.

Although it has published numerous articles about CMS and its policies, The Hospitalist has never offered an explanatory overview of one of the largest healthcare agencies in the world. In order to help hospitalists understand the policies, payments, and trends that affect them every day, we have prepared this CMS fact sheet.

Agency Background