User login

Pyogenic Hepatic Abscess in an Immunocompetent Patient With Poor Oral Health and COVID-19 Infection

Pyogenic hepatic abscess (PHA) is a collection of pus in the liver caused by bacterial infection of the liver parenchyma. This potentially life-threatening condition has a mortality rate reported to be as high as 47%.1 The incidence of PHA is reported to be 2.3 per 100,000 individuals and is more common in immunosuppressed individuals and those with diabetes mellitus, cancer, and liver transplant.2,3 PHA infections are usually polymicrobial and most commonly include enteric organisms like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.4

We present a rare cause of PHA with Fusobacterium nucleatum (F nucleatum) in an immunocompetent patient with poor oral health, history of diverticulitis, and recent COVID-19 infection whose only symptoms were chest pain and a 4-week history of fever and malaise.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man initially presented to the C.W. Bill Young Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CWBYVAMC) emergency department in Bay Pines, Florida, for fever, malaise, and right-sided chest pain on inspiration. The fever and malaise began while he was on vacation 4 weeks prior. He originally presented to an outside hospital where he tested positive for COVID-19 and was recommended ibuprofen and rest. His symptoms did not improve, and he returned a second time to the outside hospital 2 weeks later and was diagnosed with pneumonia and placed on outpatient antibiotics. The patient subsequently returned to CWBYVAMC 2 weeks after starting antibiotics when he began to develop right-sided inspiratory chest pain. He reported no other recent travel and no abdominal pain. The patient’s history was significant for diverticulitis 2 years before. A colonoscopy was performed during that time and showed no masses.

On presentation, the patient was febrile with a temperature of 100.8 °F; otherwise, his vital signs were stable. Physical examinations, including abdominal, respiratory, and cardiovascular, were unremarkable. The initial laboratory workup revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 18.7 K/μL (reference range, 5-10 K/μL) and microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 8.8 g/dL. The comprehensive metabolic panel revealed normal aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and total bilirubin levels and elevated alkaline phosphatase of 215 U/L (reference range, 44-147 U/L), revealing possible mild intrahepatic cholestasis. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria and urobilinogen. Coagulation studies showed elevated D-dimer and procalcitonin levels at 1.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.1 ng/mL) and 1.21 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.5 ng/mL), respectively, with normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. The patient had a normal troponin, fecal, and blood culture; entamoeba serology was negative.

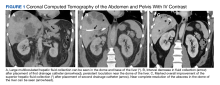

A computed tomograph (CT) angiography of the chest was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism, revealing liver lesions suspicious for abscess or metastatic disease. Minimal pleural effusion was detected bilaterally. A subsequent CT

Following the procedure, the patient developed shaking chills, hypertension, fever, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He improved with oxygen and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he had an increase in temperature and became septic without shock. A repeat blood culture was negative. An echocardiogram revealed no vegetation. Vancomycin was added for empiric coverage of potentially resistant organisms. The patient clinically improved and was able to leave the ICU 2 days later on hospital day 4.

The patient’s renal function worsened on day 5, and piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin were discontinued due to possible acute interstitial nephritis and renal toxicity. He started cefepime and continued metronidazole, and his renal function returned to normal 2 days later. Vancomycin was then re-administered. The results of the culture taken from the abscess came back positive for monomicrobial growth of F nucleatum on hospital day 9.

Due to the patient’s persisting fever and WBC count, a repeat CT of the abdomen on hospital day 10 revealed a partial decrease in the abscess with a persistent collection superior to the location of the initial pigtail catheter placement. A second pigtail catheter was then placed near the dome of the liver 1 day later on hospital day 11. Following the procedure, the patient improved significantly. The repeat CT after 1 week showed marked overall resolution of the abscess, and the repeat culture of the abscess did not reveal any organism growth. Vancomycin was discontinued on day 19, and the drains were removed on hospital day 20. He was discharged home in stable condition on metronidazole and cefdinir for 21 days with follow-up appointments for CT of the abdomen and with primary care, infectious disease, and a dental specialist.

Discussion

F nucleatum is a gram-negative, nonmotile, spindle-shaped rod found in dental plaques.5 The incidence of F nucleatum bacteremia is 0.34 per 100,000 people and increases with age, with the median age being 53.5 years.6 Although our patient did not present with F nucleatum bacteremia, it is possible that bacteremia was present before hospitalization but resolved by the time the sample was drawn for culture. F nucleatum bacteremia can lead to a variety of presentations. The most common primary diagnoses are intra-abdominal infections (eg, PHA, respiratory tract infections, and hematological disorders).1,6

PHA Presentation

The most common presenting symptoms of PHA are fever (88%), abdominal pain (79%), and vomiting (50%).4 The patient’s presentation of inspiratory right-sided chest pain is likely due to irritation of the diaphragmatic pleura of the right lung secondary to the abscess formation. The patient did not experience abdominal pain throughout the course of this disease or on palpation of his right upper quadrant. To our knowledge, this is the only case of PHA in the literature of a patient with inspiratory chest pain without respiratory infection, abdominal pain, and cardiac abnormalities. There was no radiologic evidence or signs of hypoxia on admission to CWBYVAMC, which makes respiratory infection an unlikely cause of the chest pain. Moreover, the patient presented with new-onset chest pain 2 weeks after the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Common laboratory findings of PHA include transaminitis, leukocytosis, and bilirubinemia.4 Of note, increased procalcitonin has also been associated with PHA and extreme elevation (> 200 μg/L) may be a useful biomarker to identify F nucleatum infections before the presence of leukocytosis.3 CT of PHA usually reveals right lobe involvement, and F nucleatum infection usually demonstrates multiple abscesses.4,7

Contributing Factors in F nucleatum PHA

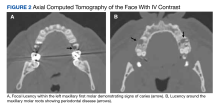

F nucleatum is associated with several oral diseases, such as periodontitis and gingivitis.8 It is important to do an oral inspection on patients with F nucleatum infections because it can spread from oral cavities to different body parts.

F nucleatum is also found in the gut.9 Any disease that can cause a break in the gastrointestinal mucosa may result in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA. This may be why F nucleatum has been associated with a variety of different diseases, such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, and colorectal cancer.10,11 Our patient had a history of diverticulosis with diverticulitis. Bawa and colleagues described a patient with recurrent diverticulitis who developed F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA.11 Our patient did not have any signs of diverticulitis.

Our patient’s COVID-19 infection also had a role in delaying the appropriate treatment of PHA. Without any symptoms of PHA, a diagnosis is difficult in a patient with a positive COVID-19 test, and treatment was delayed 1 month. Moreover, COVID-19 has been reported to delay the diagnosis of PHA even in the absence of a positive COVID-19 test. Collins and Diamond presented a patient during the COVID-19 pandemic who developed a periodontal abscess, which resulted in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA due to delayed hospital presentation after the patient’s practitioners recommended self-isolation, despite a negative COVID-19 test.12 This highlights the impact that COVID-19 may have on the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with PHA.

Malignancy has been associated with F nucleatum bacteremia.1,13 Possibly the association is due to gastrointestinal mucosa malignancy’s ability to cause micro-abrasions, resulting in F nucleatum bacteremia.10 Additionally, F nucleatum may promote the development of colorectal neoplasms.8 Due to this association, screening for colorectal cancer in patients with F nucleatum infection is important. In our patient, a colonoscopy was performed during the patient’s hospitalization for diverticulitis 2 years prior. No signs of colorectal neoplasm were noted

Conclusions

PHA due to F nucleatum is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that must be diagnosed and treated promptly. It usually presents with fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting but can present with chest pain in the absence of a respiratory infection, cardiac abnormalities, and abdominal pain, as in our patient. A wide spectrum of infections can occur with F nucleatum, including PHA.

Suspicion for infection with this organism should be kept high in middle-aged and older individuals who present with an indolent disease course and have risk factors, such as poor oral health and comorbidities. Suspicion should be kept high even in the event of COVID-19 infection, especially in individuals with prolonged fever without other signs indicating respiratory infection. We believe that the most likely causes of this patient’s infection were his dental caries and periodontal disease. The timing of his symptoms is not consistent with his previous episode of diverticulitis. Due to the mortality of PHA, diagnosis and treatment must be prompt. Initial treatment with drainage and empiric anaerobic coverage is recommended, followed by a tailored antibiotic regiment if indicated by culture, and further drainage if suggested by imaging.

1. Yang CC, Ye JJ, Hsu PC, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of Fusobacterium nucleatum bacteremia—a 6-year experience at a tertiary care hospital in northern Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(2):167-174. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.017

2. Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(11):1032-1038. doi:10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8

3. Cao SA, Hinchey S. Identification and management of fusobacterium nucleatum liver abscess and bacteremia in a young healthy man. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12303. doi:10.7759/cureus.12303

4. Abbas MT, Khan FY, Muhsin SA, Al-Dehwe B, Abukamar M, Elzouki AN. Epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of liver abscess: a single reference center experience in Qatar. Oman Med J. 2014;29(4):260-263. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.69

5. Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(1):55-71. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.1.55

6. Afra K, Laupland K, Leal J, Lloyd T, Gregson D. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Fusobacterium species bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:264. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-264

7. Crippin JS, Wang KK. An unrecognized etiology for pyogenic hepatic abscesses in normal hosts: dental disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(12):1740-1743.

8. Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(3):71-81. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v10.i3.71

9. Allen-Vercoe E, Strauss J, Chadee K. Fusobacterium nucleatum: an emerging gut pathogen? Gut Microbes. 2011;2(5):294-298. doi:10.4161/gmic.2.5.18603

10. Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013

11. Bawa A, Kainat A, Raza H, George TB, Omer H, Pillai AC. Fusobacterium bacteremia causing hepatic abscess in a patient with diverticulitis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26938. doi:10.7759/cureus.26938

12. Collins L, Diamond T. Fusobacterium nucleatum causing a pyogenic liver abscess: a rare complication of periodontal disease that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e240080. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-240080

13. Nohrstrom E, Mattila T, Pettila V, et al. Clinical spectrum of bacteraemic Fusobacterium infections: from septic shock to nosocomial bacteraemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(6-7):463-470. doi:10.3109/00365548.2011.565071

Pyogenic hepatic abscess (PHA) is a collection of pus in the liver caused by bacterial infection of the liver parenchyma. This potentially life-threatening condition has a mortality rate reported to be as high as 47%.1 The incidence of PHA is reported to be 2.3 per 100,000 individuals and is more common in immunosuppressed individuals and those with diabetes mellitus, cancer, and liver transplant.2,3 PHA infections are usually polymicrobial and most commonly include enteric organisms like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.4

We present a rare cause of PHA with Fusobacterium nucleatum (F nucleatum) in an immunocompetent patient with poor oral health, history of diverticulitis, and recent COVID-19 infection whose only symptoms were chest pain and a 4-week history of fever and malaise.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man initially presented to the C.W. Bill Young Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CWBYVAMC) emergency department in Bay Pines, Florida, for fever, malaise, and right-sided chest pain on inspiration. The fever and malaise began while he was on vacation 4 weeks prior. He originally presented to an outside hospital where he tested positive for COVID-19 and was recommended ibuprofen and rest. His symptoms did not improve, and he returned a second time to the outside hospital 2 weeks later and was diagnosed with pneumonia and placed on outpatient antibiotics. The patient subsequently returned to CWBYVAMC 2 weeks after starting antibiotics when he began to develop right-sided inspiratory chest pain. He reported no other recent travel and no abdominal pain. The patient’s history was significant for diverticulitis 2 years before. A colonoscopy was performed during that time and showed no masses.

On presentation, the patient was febrile with a temperature of 100.8 °F; otherwise, his vital signs were stable. Physical examinations, including abdominal, respiratory, and cardiovascular, were unremarkable. The initial laboratory workup revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 18.7 K/μL (reference range, 5-10 K/μL) and microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 8.8 g/dL. The comprehensive metabolic panel revealed normal aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and total bilirubin levels and elevated alkaline phosphatase of 215 U/L (reference range, 44-147 U/L), revealing possible mild intrahepatic cholestasis. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria and urobilinogen. Coagulation studies showed elevated D-dimer and procalcitonin levels at 1.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.1 ng/mL) and 1.21 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.5 ng/mL), respectively, with normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. The patient had a normal troponin, fecal, and blood culture; entamoeba serology was negative.

A computed tomograph (CT) angiography of the chest was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism, revealing liver lesions suspicious for abscess or metastatic disease. Minimal pleural effusion was detected bilaterally. A subsequent CT

Following the procedure, the patient developed shaking chills, hypertension, fever, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He improved with oxygen and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he had an increase in temperature and became septic without shock. A repeat blood culture was negative. An echocardiogram revealed no vegetation. Vancomycin was added for empiric coverage of potentially resistant organisms. The patient clinically improved and was able to leave the ICU 2 days later on hospital day 4.

The patient’s renal function worsened on day 5, and piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin were discontinued due to possible acute interstitial nephritis and renal toxicity. He started cefepime and continued metronidazole, and his renal function returned to normal 2 days later. Vancomycin was then re-administered. The results of the culture taken from the abscess came back positive for monomicrobial growth of F nucleatum on hospital day 9.

Due to the patient’s persisting fever and WBC count, a repeat CT of the abdomen on hospital day 10 revealed a partial decrease in the abscess with a persistent collection superior to the location of the initial pigtail catheter placement. A second pigtail catheter was then placed near the dome of the liver 1 day later on hospital day 11. Following the procedure, the patient improved significantly. The repeat CT after 1 week showed marked overall resolution of the abscess, and the repeat culture of the abscess did not reveal any organism growth. Vancomycin was discontinued on day 19, and the drains were removed on hospital day 20. He was discharged home in stable condition on metronidazole and cefdinir for 21 days with follow-up appointments for CT of the abdomen and with primary care, infectious disease, and a dental specialist.

Discussion

F nucleatum is a gram-negative, nonmotile, spindle-shaped rod found in dental plaques.5 The incidence of F nucleatum bacteremia is 0.34 per 100,000 people and increases with age, with the median age being 53.5 years.6 Although our patient did not present with F nucleatum bacteremia, it is possible that bacteremia was present before hospitalization but resolved by the time the sample was drawn for culture. F nucleatum bacteremia can lead to a variety of presentations. The most common primary diagnoses are intra-abdominal infections (eg, PHA, respiratory tract infections, and hematological disorders).1,6

PHA Presentation

The most common presenting symptoms of PHA are fever (88%), abdominal pain (79%), and vomiting (50%).4 The patient’s presentation of inspiratory right-sided chest pain is likely due to irritation of the diaphragmatic pleura of the right lung secondary to the abscess formation. The patient did not experience abdominal pain throughout the course of this disease or on palpation of his right upper quadrant. To our knowledge, this is the only case of PHA in the literature of a patient with inspiratory chest pain without respiratory infection, abdominal pain, and cardiac abnormalities. There was no radiologic evidence or signs of hypoxia on admission to CWBYVAMC, which makes respiratory infection an unlikely cause of the chest pain. Moreover, the patient presented with new-onset chest pain 2 weeks after the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Common laboratory findings of PHA include transaminitis, leukocytosis, and bilirubinemia.4 Of note, increased procalcitonin has also been associated with PHA and extreme elevation (> 200 μg/L) may be a useful biomarker to identify F nucleatum infections before the presence of leukocytosis.3 CT of PHA usually reveals right lobe involvement, and F nucleatum infection usually demonstrates multiple abscesses.4,7

Contributing Factors in F nucleatum PHA

F nucleatum is associated with several oral diseases, such as periodontitis and gingivitis.8 It is important to do an oral inspection on patients with F nucleatum infections because it can spread from oral cavities to different body parts.

F nucleatum is also found in the gut.9 Any disease that can cause a break in the gastrointestinal mucosa may result in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA. This may be why F nucleatum has been associated with a variety of different diseases, such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, and colorectal cancer.10,11 Our patient had a history of diverticulosis with diverticulitis. Bawa and colleagues described a patient with recurrent diverticulitis who developed F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA.11 Our patient did not have any signs of diverticulitis.

Our patient’s COVID-19 infection also had a role in delaying the appropriate treatment of PHA. Without any symptoms of PHA, a diagnosis is difficult in a patient with a positive COVID-19 test, and treatment was delayed 1 month. Moreover, COVID-19 has been reported to delay the diagnosis of PHA even in the absence of a positive COVID-19 test. Collins and Diamond presented a patient during the COVID-19 pandemic who developed a periodontal abscess, which resulted in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA due to delayed hospital presentation after the patient’s practitioners recommended self-isolation, despite a negative COVID-19 test.12 This highlights the impact that COVID-19 may have on the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with PHA.

Malignancy has been associated with F nucleatum bacteremia.1,13 Possibly the association is due to gastrointestinal mucosa malignancy’s ability to cause micro-abrasions, resulting in F nucleatum bacteremia.10 Additionally, F nucleatum may promote the development of colorectal neoplasms.8 Due to this association, screening for colorectal cancer in patients with F nucleatum infection is important. In our patient, a colonoscopy was performed during the patient’s hospitalization for diverticulitis 2 years prior. No signs of colorectal neoplasm were noted

Conclusions

PHA due to F nucleatum is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that must be diagnosed and treated promptly. It usually presents with fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting but can present with chest pain in the absence of a respiratory infection, cardiac abnormalities, and abdominal pain, as in our patient. A wide spectrum of infections can occur with F nucleatum, including PHA.

Suspicion for infection with this organism should be kept high in middle-aged and older individuals who present with an indolent disease course and have risk factors, such as poor oral health and comorbidities. Suspicion should be kept high even in the event of COVID-19 infection, especially in individuals with prolonged fever without other signs indicating respiratory infection. We believe that the most likely causes of this patient’s infection were his dental caries and periodontal disease. The timing of his symptoms is not consistent with his previous episode of diverticulitis. Due to the mortality of PHA, diagnosis and treatment must be prompt. Initial treatment with drainage and empiric anaerobic coverage is recommended, followed by a tailored antibiotic regiment if indicated by culture, and further drainage if suggested by imaging.

Pyogenic hepatic abscess (PHA) is a collection of pus in the liver caused by bacterial infection of the liver parenchyma. This potentially life-threatening condition has a mortality rate reported to be as high as 47%.1 The incidence of PHA is reported to be 2.3 per 100,000 individuals and is more common in immunosuppressed individuals and those with diabetes mellitus, cancer, and liver transplant.2,3 PHA infections are usually polymicrobial and most commonly include enteric organisms like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae.4

We present a rare cause of PHA with Fusobacterium nucleatum (F nucleatum) in an immunocompetent patient with poor oral health, history of diverticulitis, and recent COVID-19 infection whose only symptoms were chest pain and a 4-week history of fever and malaise.

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man initially presented to the C.W. Bill Young Veterans Affairs Medical Center (CWBYVAMC) emergency department in Bay Pines, Florida, for fever, malaise, and right-sided chest pain on inspiration. The fever and malaise began while he was on vacation 4 weeks prior. He originally presented to an outside hospital where he tested positive for COVID-19 and was recommended ibuprofen and rest. His symptoms did not improve, and he returned a second time to the outside hospital 2 weeks later and was diagnosed with pneumonia and placed on outpatient antibiotics. The patient subsequently returned to CWBYVAMC 2 weeks after starting antibiotics when he began to develop right-sided inspiratory chest pain. He reported no other recent travel and no abdominal pain. The patient’s history was significant for diverticulitis 2 years before. A colonoscopy was performed during that time and showed no masses.

On presentation, the patient was febrile with a temperature of 100.8 °F; otherwise, his vital signs were stable. Physical examinations, including abdominal, respiratory, and cardiovascular, were unremarkable. The initial laboratory workup revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 18.7 K/μL (reference range, 5-10 K/μL) and microcytic anemia with a hemoglobin level of 8.8 g/dL. The comprehensive metabolic panel revealed normal aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, and total bilirubin levels and elevated alkaline phosphatase of 215 U/L (reference range, 44-147 U/L), revealing possible mild intrahepatic cholestasis. Urinalysis showed trace proteinuria and urobilinogen. Coagulation studies showed elevated D-dimer and procalcitonin levels at 1.9 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.1 ng/mL) and 1.21 ng/mL (reference range, < 0.5 ng/mL), respectively, with normal prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times. The patient had a normal troponin, fecal, and blood culture; entamoeba serology was negative.

A computed tomograph (CT) angiography of the chest was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism, revealing liver lesions suspicious for abscess or metastatic disease. Minimal pleural effusion was detected bilaterally. A subsequent CT

Following the procedure, the patient developed shaking chills, hypertension, fever, and acute hypoxic respiratory failure. He improved with oxygen and was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) where he had an increase in temperature and became septic without shock. A repeat blood culture was negative. An echocardiogram revealed no vegetation. Vancomycin was added for empiric coverage of potentially resistant organisms. The patient clinically improved and was able to leave the ICU 2 days later on hospital day 4.

The patient’s renal function worsened on day 5, and piperacillin-tazobactam and vancomycin were discontinued due to possible acute interstitial nephritis and renal toxicity. He started cefepime and continued metronidazole, and his renal function returned to normal 2 days later. Vancomycin was then re-administered. The results of the culture taken from the abscess came back positive for monomicrobial growth of F nucleatum on hospital day 9.

Due to the patient’s persisting fever and WBC count, a repeat CT of the abdomen on hospital day 10 revealed a partial decrease in the abscess with a persistent collection superior to the location of the initial pigtail catheter placement. A second pigtail catheter was then placed near the dome of the liver 1 day later on hospital day 11. Following the procedure, the patient improved significantly. The repeat CT after 1 week showed marked overall resolution of the abscess, and the repeat culture of the abscess did not reveal any organism growth. Vancomycin was discontinued on day 19, and the drains were removed on hospital day 20. He was discharged home in stable condition on metronidazole and cefdinir for 21 days with follow-up appointments for CT of the abdomen and with primary care, infectious disease, and a dental specialist.

Discussion

F nucleatum is a gram-negative, nonmotile, spindle-shaped rod found in dental plaques.5 The incidence of F nucleatum bacteremia is 0.34 per 100,000 people and increases with age, with the median age being 53.5 years.6 Although our patient did not present with F nucleatum bacteremia, it is possible that bacteremia was present before hospitalization but resolved by the time the sample was drawn for culture. F nucleatum bacteremia can lead to a variety of presentations. The most common primary diagnoses are intra-abdominal infections (eg, PHA, respiratory tract infections, and hematological disorders).1,6

PHA Presentation

The most common presenting symptoms of PHA are fever (88%), abdominal pain (79%), and vomiting (50%).4 The patient’s presentation of inspiratory right-sided chest pain is likely due to irritation of the diaphragmatic pleura of the right lung secondary to the abscess formation. The patient did not experience abdominal pain throughout the course of this disease or on palpation of his right upper quadrant. To our knowledge, this is the only case of PHA in the literature of a patient with inspiratory chest pain without respiratory infection, abdominal pain, and cardiac abnormalities. There was no radiologic evidence or signs of hypoxia on admission to CWBYVAMC, which makes respiratory infection an unlikely cause of the chest pain. Moreover, the patient presented with new-onset chest pain 2 weeks after the diagnosis of pneumonia.

Common laboratory findings of PHA include transaminitis, leukocytosis, and bilirubinemia.4 Of note, increased procalcitonin has also been associated with PHA and extreme elevation (> 200 μg/L) may be a useful biomarker to identify F nucleatum infections before the presence of leukocytosis.3 CT of PHA usually reveals right lobe involvement, and F nucleatum infection usually demonstrates multiple abscesses.4,7

Contributing Factors in F nucleatum PHA

F nucleatum is associated with several oral diseases, such as periodontitis and gingivitis.8 It is important to do an oral inspection on patients with F nucleatum infections because it can spread from oral cavities to different body parts.

F nucleatum is also found in the gut.9 Any disease that can cause a break in the gastrointestinal mucosa may result in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA. This may be why F nucleatum has been associated with a variety of different diseases, such as diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, appendicitis, and colorectal cancer.10,11 Our patient had a history of diverticulosis with diverticulitis. Bawa and colleagues described a patient with recurrent diverticulitis who developed F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA.11 Our patient did not have any signs of diverticulitis.

Our patient’s COVID-19 infection also had a role in delaying the appropriate treatment of PHA. Without any symptoms of PHA, a diagnosis is difficult in a patient with a positive COVID-19 test, and treatment was delayed 1 month. Moreover, COVID-19 has been reported to delay the diagnosis of PHA even in the absence of a positive COVID-19 test. Collins and Diamond presented a patient during the COVID-19 pandemic who developed a periodontal abscess, which resulted in F nucleatum bacteremia and PHA due to delayed hospital presentation after the patient’s practitioners recommended self-isolation, despite a negative COVID-19 test.12 This highlights the impact that COVID-19 may have on the timely diagnosis and treatment of patients with PHA.

Malignancy has been associated with F nucleatum bacteremia.1,13 Possibly the association is due to gastrointestinal mucosa malignancy’s ability to cause micro-abrasions, resulting in F nucleatum bacteremia.10 Additionally, F nucleatum may promote the development of colorectal neoplasms.8 Due to this association, screening for colorectal cancer in patients with F nucleatum infection is important. In our patient, a colonoscopy was performed during the patient’s hospitalization for diverticulitis 2 years prior. No signs of colorectal neoplasm were noted

Conclusions

PHA due to F nucleatum is a rare but potentially life-threatening condition that must be diagnosed and treated promptly. It usually presents with fever, abdominal pain, and vomiting but can present with chest pain in the absence of a respiratory infection, cardiac abnormalities, and abdominal pain, as in our patient. A wide spectrum of infections can occur with F nucleatum, including PHA.

Suspicion for infection with this organism should be kept high in middle-aged and older individuals who present with an indolent disease course and have risk factors, such as poor oral health and comorbidities. Suspicion should be kept high even in the event of COVID-19 infection, especially in individuals with prolonged fever without other signs indicating respiratory infection. We believe that the most likely causes of this patient’s infection were his dental caries and periodontal disease. The timing of his symptoms is not consistent with his previous episode of diverticulitis. Due to the mortality of PHA, diagnosis and treatment must be prompt. Initial treatment with drainage and empiric anaerobic coverage is recommended, followed by a tailored antibiotic regiment if indicated by culture, and further drainage if suggested by imaging.

1. Yang CC, Ye JJ, Hsu PC, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of Fusobacterium nucleatum bacteremia—a 6-year experience at a tertiary care hospital in northern Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(2):167-174. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.017

2. Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(11):1032-1038. doi:10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8

3. Cao SA, Hinchey S. Identification and management of fusobacterium nucleatum liver abscess and bacteremia in a young healthy man. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12303. doi:10.7759/cureus.12303

4. Abbas MT, Khan FY, Muhsin SA, Al-Dehwe B, Abukamar M, Elzouki AN. Epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of liver abscess: a single reference center experience in Qatar. Oman Med J. 2014;29(4):260-263. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.69

5. Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(1):55-71. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.1.55

6. Afra K, Laupland K, Leal J, Lloyd T, Gregson D. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Fusobacterium species bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:264. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-264

7. Crippin JS, Wang KK. An unrecognized etiology for pyogenic hepatic abscesses in normal hosts: dental disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(12):1740-1743.

8. Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(3):71-81. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v10.i3.71

9. Allen-Vercoe E, Strauss J, Chadee K. Fusobacterium nucleatum: an emerging gut pathogen? Gut Microbes. 2011;2(5):294-298. doi:10.4161/gmic.2.5.18603

10. Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013

11. Bawa A, Kainat A, Raza H, George TB, Omer H, Pillai AC. Fusobacterium bacteremia causing hepatic abscess in a patient with diverticulitis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26938. doi:10.7759/cureus.26938

12. Collins L, Diamond T. Fusobacterium nucleatum causing a pyogenic liver abscess: a rare complication of periodontal disease that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e240080. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-240080

13. Nohrstrom E, Mattila T, Pettila V, et al. Clinical spectrum of bacteraemic Fusobacterium infections: from septic shock to nosocomial bacteraemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(6-7):463-470. doi:10.3109/00365548.2011.565071

1. Yang CC, Ye JJ, Hsu PC, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of Fusobacterium nucleatum bacteremia—a 6-year experience at a tertiary care hospital in northern Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;70(2):167-174. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.12.017

2. Kaplan GG, Gregson DB, Laupland KB. Population-based study of the epidemiology of and the risk factors for pyogenic liver abscess. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2(11):1032-1038. doi:10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00459-8

3. Cao SA, Hinchey S. Identification and management of fusobacterium nucleatum liver abscess and bacteremia in a young healthy man. Cureus. 2020;12(12):e12303. doi:10.7759/cureus.12303

4. Abbas MT, Khan FY, Muhsin SA, Al-Dehwe B, Abukamar M, Elzouki AN. Epidemiology, clinical features and outcome of liver abscess: a single reference center experience in Qatar. Oman Med J. 2014;29(4):260-263. doi:10.5001/omj.2014.69

5. Bolstad AI, Jensen HB, Bakken V. Taxonomy, biology, and periodontal aspects of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9(1):55-71. doi:10.1128/CMR.9.1.55

6. Afra K, Laupland K, Leal J, Lloyd T, Gregson D. Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of Fusobacterium species bacteremia. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:264. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-13-264

7. Crippin JS, Wang KK. An unrecognized etiology for pyogenic hepatic abscesses in normal hosts: dental disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(12):1740-1743.

8. Shang FM, Liu HL. Fusobacterium nucleatum and colorectal cancer: a review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018;10(3):71-81. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v10.i3.71

9. Allen-Vercoe E, Strauss J, Chadee K. Fusobacterium nucleatum: an emerging gut pathogen? Gut Microbes. 2011;2(5):294-298. doi:10.4161/gmic.2.5.18603

10. Han YW. Fusobacterium nucleatum: a commensal-turned pathogen. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;23:141-147. doi:10.1016/j.mib.2014.11.013

11. Bawa A, Kainat A, Raza H, George TB, Omer H, Pillai AC. Fusobacterium bacteremia causing hepatic abscess in a patient with diverticulitis. Cureus. 2022;14(7):e26938. doi:10.7759/cureus.26938

12. Collins L, Diamond T. Fusobacterium nucleatum causing a pyogenic liver abscess: a rare complication of periodontal disease that occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14(1):e240080. doi:10.1136/bcr-2020-240080

13. Nohrstrom E, Mattila T, Pettila V, et al. Clinical spectrum of bacteraemic Fusobacterium infections: from septic shock to nosocomial bacteraemia. Scand J Infect Dis. 2011;43(6-7):463-470. doi:10.3109/00365548.2011.565071

Impact of Pharmacist Interventions at an Outpatient US Coast Guard Clinic

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.

New recruits and accessions into the USCG are first screened for disqualifying health conditions, and ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness throughout their careers.2 Therefore, this population tends to be younger and overall healthier compared with the general population. Equally important, medication errors or inappropriate prescribing in the ADSM group could negatively affect their duty status and mission readiness of the USCG in addition to exposing the ADSM to medication-related harms.

Duty status is an important and unique consideration in this population. ADSMs are expected to be deployable worldwide and physically and mentally capable of executing all duties associated with their position. Duty status implications and the perceived ability to stand watch are tied to an ADMS’s specialty, training, and unit role. Duty status is based on various frameworks like the USCG Medical Manual, Aeromedical Policy Letters, and other governing documents.3 Duty status determinations are initiated by privileged USCG medical practitioners and may be executed in consultation with relevant commands and other subject matter experts. An inappropriately dosed antibiotic prescription, for example, can extend the duration that an ADSM would be considered unfit for full duty due to prolonged illness. Accordingly, being on a limited duty status may negatively affect USCG total mission readiness as a whole. USCG pharmacists play a vital role in optimizing ADSMs’ medication therapies to ensure safety and efficacy.

Currently no published literature explores the number of medication interventions or the impact of those interventions made by USCG pharmacists. This study aimed to quantify the number, duty status impact, and replicability of medication interventions made by one pharmacist at the USCG Base Alameda clinic over 6 months.

Methods

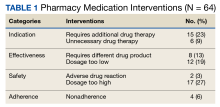

As part of a USCG quality improvement study, a pharmacist tracked all medication interventions on a spreadsheet at USCG Base Alameda clinic from July 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. The study defined a medication intervention as a communication with the prescriber with the intention to change the medication, strength, dose, dosage form, quantity, or instructions. Each intervention was subcategorized as either a drug therapy problem (DTP) or a non-DTP intervention. Interventions were divided into 7 categories.

Each DTP intervention was evaluated in a retrospective chart review by a panel of USCG pharmacists to assess for duty status severity and replicability. For duty status severity, the panel reviewed the intervention after considering patient-specific factors and determined whether the original prescribing (had there not been an intervention) could have reasonably resulted in a change of duty status for the ADSM from a fit for full duty (FFFD) status to a different duty status (eg, fit for limited duty [FFLD]). This duty status review factored in potential impacts across multiple positions and billets, including aviators (pilots) and divers. In addition, the panel, whose members all have prior community pharmacy experience, assessed replicability by determining whether the same intervention could have reasonably been made in the absence of access to the patient EHR, as would be common in a community pharmacy setting.

Interventions without an identified DTP were considered non-DTP interventions. These interventions involved recommendations for a more cost-effective medication or a similar in stock therapeutic option to minimize delay of patient care. The spreadsheet also included the date, medication name, medication class, specific intervention made, outcome, and other descriptive comments.

Results

During the 6-month period, 1751 prescriptions were dispensed at USCG Base Alameda pharmacy with 116 interventions (7%).

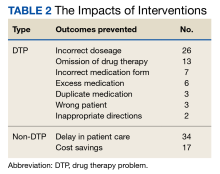

Among the DTP interventions, 26 (41%) dealt with an inappropriate dose, 13 (20%) were for medication omission, 7 (11%) for inappropriate dosage form, and 6 (9%) for excess medication (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is novel in examining the impact of a pharmacist’s medication interventions in a USCG ambulatory care practice setting. A PubMed literature search of the phrases “Coast Guard AND pharmacy” or “Coast Guard AND pharmacy AND intervention” yielded no results specific to pharmacy interventions in a USCG setting. However, the 2021 implementation of the enterprise-wide MHS GENESIS EHR may support additional tracking and analysis tools in the future.

Pharmacist interventions have been studied in diverse patient populations and practice settings, and most conclude that pharmacists make meaningful interventions at their respective organizations.4-7 Many of these studies were conducted at open-door health care systems, whereas USCG clinics serve ADSMs nearly exclusively. The ADSM population tends to be younger and healthier due to age requirements and medical accession and retention standards.

It is important to recognize the value of a USCG pharmacist in identifying and rectifying potential medication errors, particularly those that may affect the ability to stand duty for ADSMs. An example intervention includes changing the daily starting dose of citalopram from the ordered 30 mg to the intended 10 mg. Inappropriately prescribed medication regimens may increase the incidence of adverse effects or prolong duration to therapeutic efficacy, which impairs the ability to stand duty. There were 3 circumstances where the prescriber had ordered the medication for an incorrect ADSM that were rectified by the pharmacist. If left unchanged, these errors could negatively affect the ADSM’s overall health, well-being, and duty status.

The acceptance rate for interventions in this study was 96%. The literature suggests a highly variable acceptance rate of pharmacist interventions when examined across various practice settings, health systems, and geographic locations.8-10 This study’s comparatively high rate could be due to the pharmacist-prescriber relationships at USCG clinics. By virtue of colocatation and teamwork initiatives, the pharmacist has the opportunity to develop positive rapport with physicians, physician assistants, and other clinic staff.

Having access to EHRs allowed the pharmacist to make 18 of the DTP interventions. Chart access is not unique to the USCG and is common in other ambulatory care settings. Those 18 interventions, such as reconciling a prescription ordered as fluticasone/salmeterol but recorded in the EHR as “will prescribe montelukast,” were deemed possible because of EHR access. Such interventions could potentially be lost if ADSMs solely received their pharmaceutical care elsewhere.

USCG uses independent duty health services technicians (IDHSs) who practice in settings where a medical officer is not present, such as at smaller sickbays or aboard Coast Guard cutters. In this study, an IDHS had mistakenly created a medication order for the medical officer to sign for bupropion SR, when the ADSM had been taking and was intended to continue taking bupropion XL. This order was signed off by the medical officer, but this oversight was identified and corrected by the pharmacist before dispensing. This indicates that there is a vital educational role that the USCG pharmacist fulfills when working with health care team members within the AOR.

Equally important to consider are the non-DTP interventions. In a military setting, minimizations of delay in care are a high priority. There were 34 instances where the pharmacist made an intervention to recommend a similar therapeutic medication that was in stock to ensure that the ADSM had timely access to the medication without the need for prior authorization. In the context of short-notice, mission-critical deployments that may last for multiple months, recognizing medication shortages or other inventory constraints and recommending therapeutic alternatives ensures that the USCG can maintain a ready posture for missions in addition to providing timely and quality patient care.

Saving about $1700 over 6 months is also important. While this was not explicitly evaluated in the study, prescribers may not be acutely aware of medication pricing. There are often significant price differences between different formulations of the same medication (eg, naproxen delayed-release vs tablets). Because USCG pharmacists are responsible for ordering medications and managing their regional budget within the AOR, they are best poised to make cost-savings recommendations. These interventions suggest that USCG pharmacists must continue to remain actively involved in the patient care team alongside physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and corpsmen. Throughout this setting and in so many others, patients’ health outcomes improve when pharmacists are more engaged in the pharmacotherapy care plan.

Limitations

Currently, the USCG does not publish ADSM demographic or health-related data, making it difficult to evaluate these interventions in the context of age, gender, or type of disease. Accordingly, potential directions for future research include how USCG pharmacists’ interventions are stratified by duty station and initial diagnosis. Such studies may support future models where USCG pharmacists are providing targeted education to prescribers based on disease or medication classes.

This analysis may have limited applicability to other practice settings even within USCG. Most USCG clinics have a limited number of medical officers; indeed, many have only one, and clinics with pharmacies typically have 1 to 5 medical officers aboard. USCG medical officers have a multitude of other duties, which may impact prescribing patterns and pharmacist interventions. Statistical analyses were limited by the dearth of baseline data or comparative literature. Finally, the assessment of DTP interventions’ impact did not use an official measurement tool like the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Safety Assessment Code matrix.11 Instead, the study used the internal USCG pharmacist panel for the fitness for duty consideration as the main stratification of the DTP interventions’ duty status severity, because maintaining medical readiness is the top priority for a USCG clinic.

Conclusions

The multifaceted role of pharmacists in USCG clinics includes collaborating with the patient care team to make pharmacy interventions that have significant impacts on ADSMs’ wellness and the USCG mission. The ADSMs of this nation deserve quality medical care that translates into mission readiness, and the USCG pharmacy force stands ready to support that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of CDR Christopher Janik, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and LCDR Darin Schneider, US Coast Guard D11 Regional Practice Manager, in the drafting of the manuscript.

1. US Coast Guard. Missions. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions

2. US Coast Guard. Coast Guard Medical Manual. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/14/2003076969/-1/-1/0/CIM_6000_1F.PDF

3. US Coast Guard. USCG Aeromedical Policy Letters. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-1/cg112/cg1121/docs/pdf/USCG_Aeromedical_Policy_Letters.pdf

4. Bedouch P, Sylvoz N, Charpiat B, et al. Trends in pharmacists’ medication order review in French hospitals from 2006 to 2009: analysis of pharmacists’ interventions from the Act-IP website observatory. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(1):32-40. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12214

5. Ooi PL, Zainal H, Lean QY, Ming LC, Ibrahim B. Pharmacists’ interventions on electronic prescriptions from various specialty wards in a Malaysian public hospital: a cross-sectional study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(4):161. Published 2021 Oct 1. doi:10.3390/pharmacy9040161

6. Alomi YA, El-Bahnasawi M, Kamran M, Shaweesh T, Alhaj S, Radwan RA. The clinical outcomes of pharmacist interventions at critical care services of private hospital in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. PTB Report. 2019;5(1):16-19. doi:10.5530/ptb.2019.5.4

7. Garin N, Sole N, Lucas B, et al. Drug related problems in clinical practice: a cross-sectional study on their prevalence, risk factors and associated pharmaceutical interventions. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):883. Published 2021 Jan 13. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80560-2

8. Zaal RJ, den Haak EW, Andrinopoulou ER, van Gelder T, Vulto AG, van den Bemt PMLA. Physicians’ acceptance of pharmacists’ interventions in daily hospital practice. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(1):141-149. doi:10.1007/s11096-020-00970-0

9. Carson GL, Crosby K, Huxall GR, Brahm NC. Acceptance rates for pharmacist-initiated interventions in long-term care facilities. Inov Pharm. 2013;4(4):Article 135.

10. Bondesson A, Holmdahl L, Midlöv P, Höglund P, Andersson E, Eriksson T. Acceptance and importance of clinical pharmacists’ LIMM-based recommendations. Int J Clin Pharm. 2012;34(2):272-276. doi:10.1007/s11096-012-9609-3

11. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Safety assessment code (SAC) matrix. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.patientsafety.va.gov/professionals/publications/matrix.asp

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.

New recruits and accessions into the USCG are first screened for disqualifying health conditions, and ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness throughout their careers.2 Therefore, this population tends to be younger and overall healthier compared with the general population. Equally important, medication errors or inappropriate prescribing in the ADSM group could negatively affect their duty status and mission readiness of the USCG in addition to exposing the ADSM to medication-related harms.

Duty status is an important and unique consideration in this population. ADSMs are expected to be deployable worldwide and physically and mentally capable of executing all duties associated with their position. Duty status implications and the perceived ability to stand watch are tied to an ADMS’s specialty, training, and unit role. Duty status is based on various frameworks like the USCG Medical Manual, Aeromedical Policy Letters, and other governing documents.3 Duty status determinations are initiated by privileged USCG medical practitioners and may be executed in consultation with relevant commands and other subject matter experts. An inappropriately dosed antibiotic prescription, for example, can extend the duration that an ADSM would be considered unfit for full duty due to prolonged illness. Accordingly, being on a limited duty status may negatively affect USCG total mission readiness as a whole. USCG pharmacists play a vital role in optimizing ADSMs’ medication therapies to ensure safety and efficacy.

Currently no published literature explores the number of medication interventions or the impact of those interventions made by USCG pharmacists. This study aimed to quantify the number, duty status impact, and replicability of medication interventions made by one pharmacist at the USCG Base Alameda clinic over 6 months.

Methods

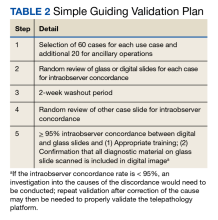

As part of a USCG quality improvement study, a pharmacist tracked all medication interventions on a spreadsheet at USCG Base Alameda clinic from July 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. The study defined a medication intervention as a communication with the prescriber with the intention to change the medication, strength, dose, dosage form, quantity, or instructions. Each intervention was subcategorized as either a drug therapy problem (DTP) or a non-DTP intervention. Interventions were divided into 7 categories.

Each DTP intervention was evaluated in a retrospective chart review by a panel of USCG pharmacists to assess for duty status severity and replicability. For duty status severity, the panel reviewed the intervention after considering patient-specific factors and determined whether the original prescribing (had there not been an intervention) could have reasonably resulted in a change of duty status for the ADSM from a fit for full duty (FFFD) status to a different duty status (eg, fit for limited duty [FFLD]). This duty status review factored in potential impacts across multiple positions and billets, including aviators (pilots) and divers. In addition, the panel, whose members all have prior community pharmacy experience, assessed replicability by determining whether the same intervention could have reasonably been made in the absence of access to the patient EHR, as would be common in a community pharmacy setting.

Interventions without an identified DTP were considered non-DTP interventions. These interventions involved recommendations for a more cost-effective medication or a similar in stock therapeutic option to minimize delay of patient care. The spreadsheet also included the date, medication name, medication class, specific intervention made, outcome, and other descriptive comments.

Results

During the 6-month period, 1751 prescriptions were dispensed at USCG Base Alameda pharmacy with 116 interventions (7%).

Among the DTP interventions, 26 (41%) dealt with an inappropriate dose, 13 (20%) were for medication omission, 7 (11%) for inappropriate dosage form, and 6 (9%) for excess medication (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is novel in examining the impact of a pharmacist’s medication interventions in a USCG ambulatory care practice setting. A PubMed literature search of the phrases “Coast Guard AND pharmacy” or “Coast Guard AND pharmacy AND intervention” yielded no results specific to pharmacy interventions in a USCG setting. However, the 2021 implementation of the enterprise-wide MHS GENESIS EHR may support additional tracking and analysis tools in the future.

Pharmacist interventions have been studied in diverse patient populations and practice settings, and most conclude that pharmacists make meaningful interventions at their respective organizations.4-7 Many of these studies were conducted at open-door health care systems, whereas USCG clinics serve ADSMs nearly exclusively. The ADSM population tends to be younger and healthier due to age requirements and medical accession and retention standards.

It is important to recognize the value of a USCG pharmacist in identifying and rectifying potential medication errors, particularly those that may affect the ability to stand duty for ADSMs. An example intervention includes changing the daily starting dose of citalopram from the ordered 30 mg to the intended 10 mg. Inappropriately prescribed medication regimens may increase the incidence of adverse effects or prolong duration to therapeutic efficacy, which impairs the ability to stand duty. There were 3 circumstances where the prescriber had ordered the medication for an incorrect ADSM that were rectified by the pharmacist. If left unchanged, these errors could negatively affect the ADSM’s overall health, well-being, and duty status.

The acceptance rate for interventions in this study was 96%. The literature suggests a highly variable acceptance rate of pharmacist interventions when examined across various practice settings, health systems, and geographic locations.8-10 This study’s comparatively high rate could be due to the pharmacist-prescriber relationships at USCG clinics. By virtue of colocatation and teamwork initiatives, the pharmacist has the opportunity to develop positive rapport with physicians, physician assistants, and other clinic staff.

Having access to EHRs allowed the pharmacist to make 18 of the DTP interventions. Chart access is not unique to the USCG and is common in other ambulatory care settings. Those 18 interventions, such as reconciling a prescription ordered as fluticasone/salmeterol but recorded in the EHR as “will prescribe montelukast,” were deemed possible because of EHR access. Such interventions could potentially be lost if ADSMs solely received their pharmaceutical care elsewhere.

USCG uses independent duty health services technicians (IDHSs) who practice in settings where a medical officer is not present, such as at smaller sickbays or aboard Coast Guard cutters. In this study, an IDHS had mistakenly created a medication order for the medical officer to sign for bupropion SR, when the ADSM had been taking and was intended to continue taking bupropion XL. This order was signed off by the medical officer, but this oversight was identified and corrected by the pharmacist before dispensing. This indicates that there is a vital educational role that the USCG pharmacist fulfills when working with health care team members within the AOR.

Equally important to consider are the non-DTP interventions. In a military setting, minimizations of delay in care are a high priority. There were 34 instances where the pharmacist made an intervention to recommend a similar therapeutic medication that was in stock to ensure that the ADSM had timely access to the medication without the need for prior authorization. In the context of short-notice, mission-critical deployments that may last for multiple months, recognizing medication shortages or other inventory constraints and recommending therapeutic alternatives ensures that the USCG can maintain a ready posture for missions in addition to providing timely and quality patient care.

Saving about $1700 over 6 months is also important. While this was not explicitly evaluated in the study, prescribers may not be acutely aware of medication pricing. There are often significant price differences between different formulations of the same medication (eg, naproxen delayed-release vs tablets). Because USCG pharmacists are responsible for ordering medications and managing their regional budget within the AOR, they are best poised to make cost-savings recommendations. These interventions suggest that USCG pharmacists must continue to remain actively involved in the patient care team alongside physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and corpsmen. Throughout this setting and in so many others, patients’ health outcomes improve when pharmacists are more engaged in the pharmacotherapy care plan.

Limitations

Currently, the USCG does not publish ADSM demographic or health-related data, making it difficult to evaluate these interventions in the context of age, gender, or type of disease. Accordingly, potential directions for future research include how USCG pharmacists’ interventions are stratified by duty station and initial diagnosis. Such studies may support future models where USCG pharmacists are providing targeted education to prescribers based on disease or medication classes.

This analysis may have limited applicability to other practice settings even within USCG. Most USCG clinics have a limited number of medical officers; indeed, many have only one, and clinics with pharmacies typically have 1 to 5 medical officers aboard. USCG medical officers have a multitude of other duties, which may impact prescribing patterns and pharmacist interventions. Statistical analyses were limited by the dearth of baseline data or comparative literature. Finally, the assessment of DTP interventions’ impact did not use an official measurement tool like the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Safety Assessment Code matrix.11 Instead, the study used the internal USCG pharmacist panel for the fitness for duty consideration as the main stratification of the DTP interventions’ duty status severity, because maintaining medical readiness is the top priority for a USCG clinic.

Conclusions

The multifaceted role of pharmacists in USCG clinics includes collaborating with the patient care team to make pharmacy interventions that have significant impacts on ADSMs’ wellness and the USCG mission. The ADSMs of this nation deserve quality medical care that translates into mission readiness, and the USCG pharmacy force stands ready to support that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of CDR Christopher Janik, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and LCDR Darin Schneider, US Coast Guard D11 Regional Practice Manager, in the drafting of the manuscript.

The US Coast Guard (USCG) operates within the US Department of Homeland Security during times of peace and represents a force of > 55,000 active-duty service members (ADSMs), civilians, and reservists. ADSMs account for about 40,000 USCG personnel. The missions of the USCG include activities such as maritime law enforcement (drug interdiction), search and rescue, and defense readiness.1 Akin to other US Department of Defense (DoD) services, USCG ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness to maximize operational success.

Whereas the DoD centralizes its health care services at military treatment facilities, USCG health care tends to be dispersed to smaller clinics and sickbays across large geographic areas. The USCG operates 42 clinics of varying sizes and medical capabilities, providing outpatient, dentistry, pharmacy, laboratory, radiology, physical therapy, optometry, and other health care services. Many ADSMs are evaluated by a USCG medical officer in these outpatient clinics, and ADSMs may choose to fill prescriptions at the in-house pharmacy if present at that clinic.

The USCG has 14 field pharmacists. In addition to the standard dispensing role at their respective clinics, USCG pharmacists provide regional oversight of pharmaceutical services for USCG units within their area of responsibility (AOR). Therefore, USCG pharmacists clinically, operationally, and logistically support these regional assets within their AOR while serving the traditional pharmacist role. USCG pharmacists have access to ADSM electronic health records (EHRs) when evaluating prescription orders, similar to other ambulatory care settings.

New recruits and accessions into the USCG are first screened for disqualifying health conditions, and ADSMs are required to maintain medical readiness throughout their careers.2 Therefore, this population tends to be younger and overall healthier compared with the general population. Equally important, medication errors or inappropriate prescribing in the ADSM group could negatively affect their duty status and mission readiness of the USCG in addition to exposing the ADSM to medication-related harms.

Duty status is an important and unique consideration in this population. ADSMs are expected to be deployable worldwide and physically and mentally capable of executing all duties associated with their position. Duty status implications and the perceived ability to stand watch are tied to an ADMS’s specialty, training, and unit role. Duty status is based on various frameworks like the USCG Medical Manual, Aeromedical Policy Letters, and other governing documents.3 Duty status determinations are initiated by privileged USCG medical practitioners and may be executed in consultation with relevant commands and other subject matter experts. An inappropriately dosed antibiotic prescription, for example, can extend the duration that an ADSM would be considered unfit for full duty due to prolonged illness. Accordingly, being on a limited duty status may negatively affect USCG total mission readiness as a whole. USCG pharmacists play a vital role in optimizing ADSMs’ medication therapies to ensure safety and efficacy.

Currently no published literature explores the number of medication interventions or the impact of those interventions made by USCG pharmacists. This study aimed to quantify the number, duty status impact, and replicability of medication interventions made by one pharmacist at the USCG Base Alameda clinic over 6 months.

Methods

As part of a USCG quality improvement study, a pharmacist tracked all medication interventions on a spreadsheet at USCG Base Alameda clinic from July 1, 2021, to December 31, 2021. The study defined a medication intervention as a communication with the prescriber with the intention to change the medication, strength, dose, dosage form, quantity, or instructions. Each intervention was subcategorized as either a drug therapy problem (DTP) or a non-DTP intervention. Interventions were divided into 7 categories.

Each DTP intervention was evaluated in a retrospective chart review by a panel of USCG pharmacists to assess for duty status severity and replicability. For duty status severity, the panel reviewed the intervention after considering patient-specific factors and determined whether the original prescribing (had there not been an intervention) could have reasonably resulted in a change of duty status for the ADSM from a fit for full duty (FFFD) status to a different duty status (eg, fit for limited duty [FFLD]). This duty status review factored in potential impacts across multiple positions and billets, including aviators (pilots) and divers. In addition, the panel, whose members all have prior community pharmacy experience, assessed replicability by determining whether the same intervention could have reasonably been made in the absence of access to the patient EHR, as would be common in a community pharmacy setting.

Interventions without an identified DTP were considered non-DTP interventions. These interventions involved recommendations for a more cost-effective medication or a similar in stock therapeutic option to minimize delay of patient care. The spreadsheet also included the date, medication name, medication class, specific intervention made, outcome, and other descriptive comments.

Results

During the 6-month period, 1751 prescriptions were dispensed at USCG Base Alameda pharmacy with 116 interventions (7%).

Among the DTP interventions, 26 (41%) dealt with an inappropriate dose, 13 (20%) were for medication omission, 7 (11%) for inappropriate dosage form, and 6 (9%) for excess medication (Table 2).

Discussion

This study is novel in examining the impact of a pharmacist’s medication interventions in a USCG ambulatory care practice setting. A PubMed literature search of the phrases “Coast Guard AND pharmacy” or “Coast Guard AND pharmacy AND intervention” yielded no results specific to pharmacy interventions in a USCG setting. However, the 2021 implementation of the enterprise-wide MHS GENESIS EHR may support additional tracking and analysis tools in the future.

Pharmacist interventions have been studied in diverse patient populations and practice settings, and most conclude that pharmacists make meaningful interventions at their respective organizations.4-7 Many of these studies were conducted at open-door health care systems, whereas USCG clinics serve ADSMs nearly exclusively. The ADSM population tends to be younger and healthier due to age requirements and medical accession and retention standards.

It is important to recognize the value of a USCG pharmacist in identifying and rectifying potential medication errors, particularly those that may affect the ability to stand duty for ADSMs. An example intervention includes changing the daily starting dose of citalopram from the ordered 30 mg to the intended 10 mg. Inappropriately prescribed medication regimens may increase the incidence of adverse effects or prolong duration to therapeutic efficacy, which impairs the ability to stand duty. There were 3 circumstances where the prescriber had ordered the medication for an incorrect ADSM that were rectified by the pharmacist. If left unchanged, these errors could negatively affect the ADSM’s overall health, well-being, and duty status.

The acceptance rate for interventions in this study was 96%. The literature suggests a highly variable acceptance rate of pharmacist interventions when examined across various practice settings, health systems, and geographic locations.8-10 This study’s comparatively high rate could be due to the pharmacist-prescriber relationships at USCG clinics. By virtue of colocatation and teamwork initiatives, the pharmacist has the opportunity to develop positive rapport with physicians, physician assistants, and other clinic staff.

Having access to EHRs allowed the pharmacist to make 18 of the DTP interventions. Chart access is not unique to the USCG and is common in other ambulatory care settings. Those 18 interventions, such as reconciling a prescription ordered as fluticasone/salmeterol but recorded in the EHR as “will prescribe montelukast,” were deemed possible because of EHR access. Such interventions could potentially be lost if ADSMs solely received their pharmaceutical care elsewhere.

USCG uses independent duty health services technicians (IDHSs) who practice in settings where a medical officer is not present, such as at smaller sickbays or aboard Coast Guard cutters. In this study, an IDHS had mistakenly created a medication order for the medical officer to sign for bupropion SR, when the ADSM had been taking and was intended to continue taking bupropion XL. This order was signed off by the medical officer, but this oversight was identified and corrected by the pharmacist before dispensing. This indicates that there is a vital educational role that the USCG pharmacist fulfills when working with health care team members within the AOR.

Equally important to consider are the non-DTP interventions. In a military setting, minimizations of delay in care are a high priority. There were 34 instances where the pharmacist made an intervention to recommend a similar therapeutic medication that was in stock to ensure that the ADSM had timely access to the medication without the need for prior authorization. In the context of short-notice, mission-critical deployments that may last for multiple months, recognizing medication shortages or other inventory constraints and recommending therapeutic alternatives ensures that the USCG can maintain a ready posture for missions in addition to providing timely and quality patient care.

Saving about $1700 over 6 months is also important. While this was not explicitly evaluated in the study, prescribers may not be acutely aware of medication pricing. There are often significant price differences between different formulations of the same medication (eg, naproxen delayed-release vs tablets). Because USCG pharmacists are responsible for ordering medications and managing their regional budget within the AOR, they are best poised to make cost-savings recommendations. These interventions suggest that USCG pharmacists must continue to remain actively involved in the patient care team alongside physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and corpsmen. Throughout this setting and in so many others, patients’ health outcomes improve when pharmacists are more engaged in the pharmacotherapy care plan.

Limitations

Currently, the USCG does not publish ADSM demographic or health-related data, making it difficult to evaluate these interventions in the context of age, gender, or type of disease. Accordingly, potential directions for future research include how USCG pharmacists’ interventions are stratified by duty station and initial diagnosis. Such studies may support future models where USCG pharmacists are providing targeted education to prescribers based on disease or medication classes.

This analysis may have limited applicability to other practice settings even within USCG. Most USCG clinics have a limited number of medical officers; indeed, many have only one, and clinics with pharmacies typically have 1 to 5 medical officers aboard. USCG medical officers have a multitude of other duties, which may impact prescribing patterns and pharmacist interventions. Statistical analyses were limited by the dearth of baseline data or comparative literature. Finally, the assessment of DTP interventions’ impact did not use an official measurement tool like the US Department of Veterans Affairs’ Safety Assessment Code matrix.11 Instead, the study used the internal USCG pharmacist panel for the fitness for duty consideration as the main stratification of the DTP interventions’ duty status severity, because maintaining medical readiness is the top priority for a USCG clinic.

Conclusions

The multifaceted role of pharmacists in USCG clinics includes collaborating with the patient care team to make pharmacy interventions that have significant impacts on ADSMs’ wellness and the USCG mission. The ADSMs of this nation deserve quality medical care that translates into mission readiness, and the USCG pharmacy force stands ready to support that goal.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of CDR Christopher Janik, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and LCDR Darin Schneider, US Coast Guard D11 Regional Practice Manager, in the drafting of the manuscript.

1. US Coast Guard. Missions. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://www.uscg.mil/About/Missions

2. US Coast Guard. Coast Guard Medical Manual. Updated September 13, 2022. Accessed May 4, 2023. https://media.defense.gov/2022/Sep/14/2003076969/-1/-1/0/CIM_6000_1F.PDF

3. US Coast Guard. USCG Aeromedical Policy Letters. Accessed May 5, 2023. https://www.dcms.uscg.mil/Portals/10/CG-1/cg112/cg1121/docs/pdf/USCG_Aeromedical_Policy_Letters.pdf

4. Bedouch P, Sylvoz N, Charpiat B, et al. Trends in pharmacists’ medication order review in French hospitals from 2006 to 2009: analysis of pharmacists’ interventions from the Act-IP website observatory. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(1):32-40. doi:10.1111/jcpt.12214

5. Ooi PL, Zainal H, Lean QY, Ming LC, Ibrahim B. Pharmacists’ interventions on electronic prescriptions from various specialty wards in a Malaysian public hospital: a cross-sectional study. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(4):161. Published 2021 Oct 1. doi:10.3390/pharmacy9040161

6. Alomi YA, El-Bahnasawi M, Kamran M, Shaweesh T, Alhaj S, Radwan RA. The clinical outcomes of pharmacist interventions at critical care services of private hospital in Riyadh City, Saudi Arabia. PTB Report. 2019;5(1):16-19. doi:10.5530/ptb.2019.5.4