User login

Chronicling gastroenterology’s history

Each May, the gastroenterology community gathers for Digestive Disease Week® to be inspired, meet up with friends and colleagues from across the globe, and learn the latest in scientific advances to inform how we care for our patients in the clinic, on inpatient wards, and in our endoscopy suites. DDW® 2023, held in the Windy City of Chicago, does not disappoint. This year’s conference features a dizzying array of offerings, including 3,500 poster and ePoster presentations and 1,300 abstract lectures, as well as the perennially well-attended AGA Post-Graduate Course and other offerings.

This year’s AGA Presidential Plenary, hosted on May 8 by outgoing AGA President Dr. John M. Carethers, is not to be missed. The session will honor the 125-year history of the AGA and recognizes the barriers overcome in diversifying the practice of gastroenterology. You will learn about individuals such as Alexis St. Martin, MD; Basil Hirschowitz, MD, AGAF; Leonidas Berry, MD; Sadye Curry, MD; and, other barrier-breakers in GI who have been instrumental in shaping the modern practice of gastroenterology. I hope you will join me in attending.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we introduce the winner of the 2023 AGA Shark Tank innovation competition, which was held during the 2023 AGA Tech Summit. We also report on a landmark phase 4, double-blind randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the effectiveness of vedolizumab in inducing remission in chronic pouchitis, and a new AGA clinical practice update on the role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis.

The AGA Government Affairs Committee also updates us on their advocacy to reform prior authorization policies affecting GI practice, and explains how you can assist in these efforts. In our Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Sharmila Anandasabapthy, MD, who shares her passion for global health and the one piece of career advice she’s glad she ignored.

Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo presents our quarterly Perspectives column highlighting differing approaches to clinical management of pancreatic cystic lesions. We hope you enjoy all of the exciting content featured in this issue and look forward to seeing you in Chicago (or, virtually) for DDW.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Each May, the gastroenterology community gathers for Digestive Disease Week® to be inspired, meet up with friends and colleagues from across the globe, and learn the latest in scientific advances to inform how we care for our patients in the clinic, on inpatient wards, and in our endoscopy suites. DDW® 2023, held in the Windy City of Chicago, does not disappoint. This year’s conference features a dizzying array of offerings, including 3,500 poster and ePoster presentations and 1,300 abstract lectures, as well as the perennially well-attended AGA Post-Graduate Course and other offerings.

This year’s AGA Presidential Plenary, hosted on May 8 by outgoing AGA President Dr. John M. Carethers, is not to be missed. The session will honor the 125-year history of the AGA and recognizes the barriers overcome in diversifying the practice of gastroenterology. You will learn about individuals such as Alexis St. Martin, MD; Basil Hirschowitz, MD, AGAF; Leonidas Berry, MD; Sadye Curry, MD; and, other barrier-breakers in GI who have been instrumental in shaping the modern practice of gastroenterology. I hope you will join me in attending.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we introduce the winner of the 2023 AGA Shark Tank innovation competition, which was held during the 2023 AGA Tech Summit. We also report on a landmark phase 4, double-blind randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the effectiveness of vedolizumab in inducing remission in chronic pouchitis, and a new AGA clinical practice update on the role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis.

The AGA Government Affairs Committee also updates us on their advocacy to reform prior authorization policies affecting GI practice, and explains how you can assist in these efforts. In our Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Sharmila Anandasabapthy, MD, who shares her passion for global health and the one piece of career advice she’s glad she ignored.

Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo presents our quarterly Perspectives column highlighting differing approaches to clinical management of pancreatic cystic lesions. We hope you enjoy all of the exciting content featured in this issue and look forward to seeing you in Chicago (or, virtually) for DDW.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

Each May, the gastroenterology community gathers for Digestive Disease Week® to be inspired, meet up with friends and colleagues from across the globe, and learn the latest in scientific advances to inform how we care for our patients in the clinic, on inpatient wards, and in our endoscopy suites. DDW® 2023, held in the Windy City of Chicago, does not disappoint. This year’s conference features a dizzying array of offerings, including 3,500 poster and ePoster presentations and 1,300 abstract lectures, as well as the perennially well-attended AGA Post-Graduate Course and other offerings.

This year’s AGA Presidential Plenary, hosted on May 8 by outgoing AGA President Dr. John M. Carethers, is not to be missed. The session will honor the 125-year history of the AGA and recognizes the barriers overcome in diversifying the practice of gastroenterology. You will learn about individuals such as Alexis St. Martin, MD; Basil Hirschowitz, MD, AGAF; Leonidas Berry, MD; Sadye Curry, MD; and, other barrier-breakers in GI who have been instrumental in shaping the modern practice of gastroenterology. I hope you will join me in attending.

In this month’s issue of GIHN, we introduce the winner of the 2023 AGA Shark Tank innovation competition, which was held during the 2023 AGA Tech Summit. We also report on a landmark phase 4, double-blind randomized trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine demonstrating the effectiveness of vedolizumab in inducing remission in chronic pouchitis, and a new AGA clinical practice update on the role of EUS-guided gallbladder drainage in acute cholecystitis.

The AGA Government Affairs Committee also updates us on their advocacy to reform prior authorization policies affecting GI practice, and explains how you can assist in these efforts. In our Member Spotlight, we introduce you to gastroenterologist Sharmila Anandasabapthy, MD, who shares her passion for global health and the one piece of career advice she’s glad she ignored.

Finally, GIHN Associate Editor Dr. Avi Ketwaroo presents our quarterly Perspectives column highlighting differing approaches to clinical management of pancreatic cystic lesions. We hope you enjoy all of the exciting content featured in this issue and look forward to seeing you in Chicago (or, virtually) for DDW.

Megan A. Adams, MD, JD, MSc

Editor-in-Chief

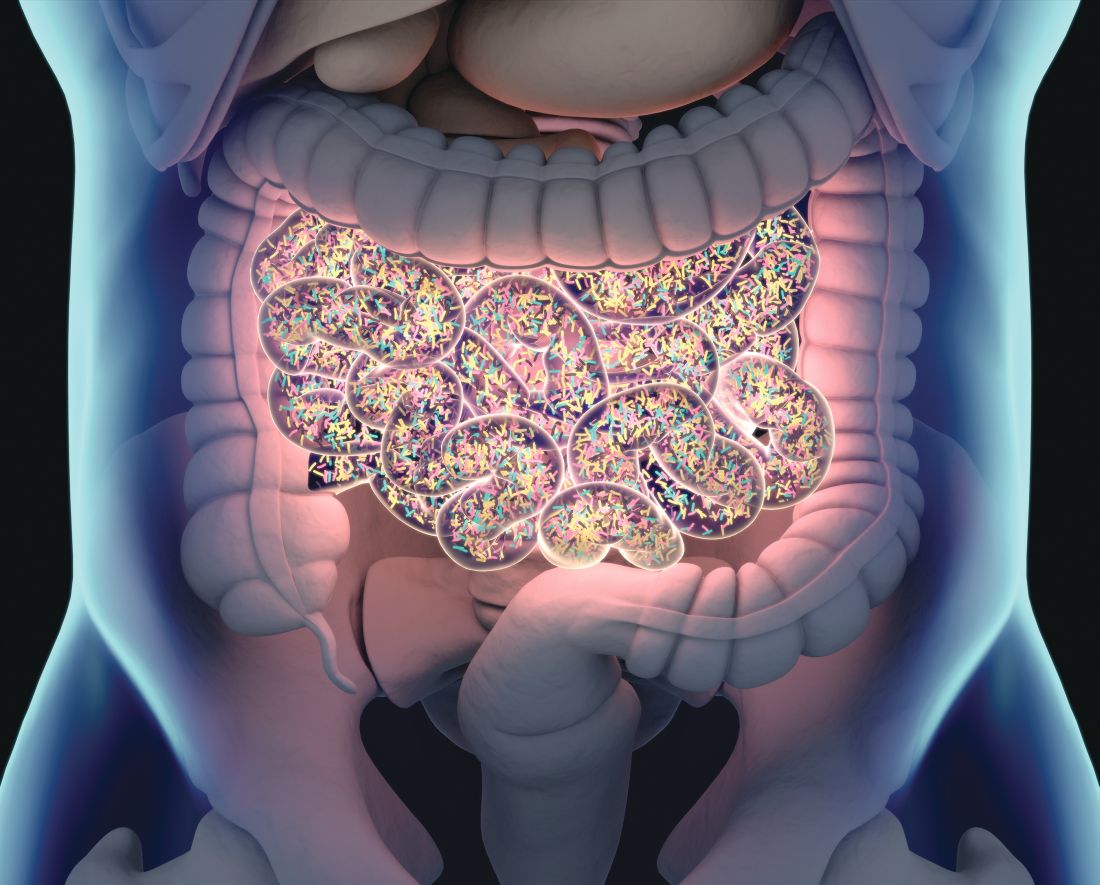

Pancreas cysts – What’s the best approach?

Dear colleagues,

Pancreas cysts have become almost ubiquitous in this era of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging. They are a common GI consult with patients and providers worried about the potential risk of malignant transformation. Despite significant research over the past few decades, predicting the natural history of these cysts, especially the side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), remains difficult. There have been a variety of expert recommendations and guidelines, but heterogeneity exists in management especially regarding timing of endoscopic ultrasound, imaging surveillance, and cessation of surveillance. Some centers will present these cysts at multidisciplinary conferences, while others will follow general or local algorithms. In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Lauren G. Khanna, assistant professor of medicine at NYU Langone Health, New York, and Dr. Santhi Vege, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., present updated and differing approaches to managing these cysts. Which side of the debate are you on? We welcome your thoughts, questions and input– share with us on Twitter @AGA_GIHN

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Continuing pancreas cyst surveillance indefinitely is reasonable

BY LAUREN G. KHANNA, MD, MS

Pancreas cysts remain a clinical challenge. The true incidence of pancreas cysts is unknown, but from MRI and autopsy series, may be up to 50%. Patients presenting with a pancreas cyst often have significant anxiety about their risk of pancreas cancer. We as a medical community initially did too; but over the past few decades as we have gathered more data, we have become more comfortable observing many pancreas cysts. Yet our recommendations for how, how often, and for how long to evaluate pancreas cysts are still very much under debate; there are multiple guidelines with discordant recommendations. In this article, I will discuss my approach to patients with a pancreas cyst.

At the first evaluation, I review available imaging to see if there are characteristic features to determine the type of pancreas cyst: IPMN (including main duct, branch duct, or mixed type), serous cystic neoplasm (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN), cystic neuroendocrine tumor (NET), or pseudocyst. I also review symptoms, including abdominal pain, weight loss, history of pancreatitis, and onset of diabetes, and check hemoglobin A1c and Ca19-9. I often recommend magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) if it has not already been obtained and is feasible (that is, if a patient does not have severe claustrophobia or a medical device incompatible with MRI). If a patient is not a candidate for treatment should a pancreatic malignancy be identified, because of age, comorbidities, or preference, I recommend no further evaluation.

Where cyst type remains unclear despite MRCP, and for cysts over 2 cm, I recommend endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for fluid sampling to assist in determining cyst type and to rule out any other high-risk features. In accordance with international guidelines, if a patient has any concerning imaging features, including main pancreatic duct dilation >5 mm, solid component or mural nodule, or thickened or enhancing duct walls, regardless of cyst size, I recommend EUS to assess for and biopsy any solid component and to sample cyst fluid to examine for dysplasia. Given the lower sensitivity of CT for high-risk features, if MRCP is not feasible, for cysts 1-2 cm, I recommend EUS for better evaluation.

If a cyst is determined to be a cystic NET; main duct or mixed-type IPMN; MCN; or SPN; or a branch duct IPMN with mural nodule, high-grade dysplasia, or adenocarcinoma, and the patient is a surgical candidate, I refer the patient for surgical evaluation. If a cyst is determined to be an SCA, the malignant potential is minimal, and patients do not require follow-up. Patients with a pseudocyst are managed according to their clinical scenario.

Many patients have a proven or suspected branch duct IPMN, an indeterminate cyst, or multiple cysts. Cyst management during surveillance is then determined by the size of the largest cyst and stability of the cyst(s). Of note, patients with an IPMN also have been shown to have an elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma, which I believe is one of the strongest arguments for heightened surveillance of the entire pancreas in pancreas cyst patients. EUS in particular can identify small or subtle lesions that are not detected by cross-sectional imaging.

If a patient has no prior imaging, in accordance with international and European guidelines, I recommend the first surveillance MRCP at a 6-month interval for cysts <2 cm, which may offer the opportunity to identify rapidly progressing cysts. If a patient has previous imaging available demonstrating stability, I recommend surveillance on an annual basis for cysts <2 cm. For patients with a cyst >2 cm, as above, I recommend EUS, and if there are no concerning features on imaging or EUS, I then recommend annual surveillance.

While the patient is under surveillance, if there is more than minimal cyst growth, a change in cyst appearance, or development of any imaging high-risk feature, pancreatitis, new onset or worsening diabetes, or elevation of Ca19-9, I recommend EUS for further evaluation and consideration of surgery based on EUS findings. If an asymptomatic cyst <2 cm remains stable for 5 years, I offer patients the option to extend imaging to every 2 years, if they are comfortable. In my experience, though, many patients prefer to continue annual imaging. The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines promote stopping surveillance after 5 years of stability, however there are studies demonstrating development of malignancy in cysts that were initially stable over the first 5 years of surveillance. Therefore, I discuss with patients that it is reasonable to continue cyst surveillance indefinitely, until they would no longer be interested in pursuing treatment of any kind if a malignant lesion were to be identified.

There are two special groups of pancreas cyst patients who warrant specific attention. Patients who are at elevated risk of pancreas adenocarcinoma because of an associated genetic mutation or a family history of pancreatic cancer already may be undergoing annual pancreas cancer screening with either MRCP, EUS, or alternating MRCP and EUS. When these high-risk patients also have pancreas cysts, I utilize whichever strategy would image their pancreas most frequently and do not extend beyond 1-year intervals. Another special group is patients who have undergone partial pancreatectomy for IPMN. As discussed above, given the elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma in IPMN patients, I recommend indefinite continued surveillance of the remaining pancreas parenchyma in these patients.

Given the prevalence of pancreas cysts, it certainly would be convenient if guidelines were straightforward enough for primary care physicians to manage pancreas cyst surveillance, as they do for breast cancer screening. However, the complexities of pancreas cysts necessitate the expertise of gastroenterologists and pancreas surgeons, and a multidisciplinary team approach is best where possible.

Dr. Khanna is chief, advanced endoscopy, Tisch Hospital; director, NYU Advanced Endoscopy Fellowship; assistant professor of medicine, NYU Langone Health. Email: [email protected]. There are no relevant conflicts to disclose.

References

Tanaka M et al. Pancreatology. 2017 Sep-Oct;17(5):738-75.

Sahora K et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 Feb;42(2):197-204.

Del Chiaro M et al. Gut. 2018 May;67(5):789-804

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015 Apr;148(4):819-22

Petrone MC et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun 13;9(6):158

Pancreas cysts: More is not necessarily better!

BY SANTHI SWAROOP VEGE, MD

Pancreas cysts (PC) are very common, incidental findings on cross-sectional imaging, performed for non–pancreas-related symptoms. The important issues in management of patients with PC in my practice are the prevalence, natural history, frequency of occurrence of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and/or pancreatic cancer (PDAC), concerning clinical symptoms and imaging findings, indications for EUS and fine-needle aspiration cytology, ideal method and frequency of surveillance, indications for surgery (up front and during follow-up), follow-up after surgery, stopping surveillance, costs, and unintentional harms of management. Good population-based evidence regarding many of the issues described above does not exist, and all information is from selected clinic, radiology, EUS, and surgical cohorts (very important when trying to assess the publications). Cohort studies should start with all PC undergoing surveillance and assess various outcomes, rather than looking backward from EUS or surgical cohorts.

The 2015 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on asymptomatic neoplastic pancreas cysts, which I coauthored, recommend, consistent with principles of High Value Care (minimal unintentional harms and cost effectiveness), that two of three high-risk features (mural nodule, cyst size greater than 3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct) be present for EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). By the same token, they advise surgery for those with two of three high-risk features and or concerning features on EUS and cytology. Finally, they suggest stopping surveillance at 5 years if there are no significant changes. Rigorous GRADE methodology along with systematic review of all relevant questions (rather than cohorts of 500 or fewer patients) formed the basis of the guidelines. Those meta-analyses showed that risk of PDAC in mural nodules, cyst size >3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct, while elevated, still is very low in absolute terms. Less than 20% of resections for highly selected, high-risk cysts showed PDAC. The guidelines were met with a lot of resistance from several societies and physician groups. The recommendations for stopping surveillance after 5 years and no surveillance for absent or low-grade dysplasia after surgery are hotly contested, and these areas need larger, long-term studies.

The whole area of cyst fluid molecular markers that would suggest mucinous type (KRAS and GNAS mutations) and, more importantly, the presence or imminent development of PDAC (next-generation sequencing or NGS) is an exciting field. One sincerely hopes that there will be a breakthrough in this area to achieve the holy grail. Cost effectiveness studies demonstrate the futility of existing guidelines and favor a less intensive approach. Guidelines are only a general framework, and management of individual patients in the clinic is entirely at the discretion of the treating physician. One should make every attempt to detect advanced lesions in PC, but such effort should not subject a large majority of patients to unintentional harms by overtreatment and add further to the burgeoning health care costs in the country.

PC are extremely common (10% of all abdominal imaging), increase with age, are seen in as many as 40%-50% of MRI examinations for nonpancreatic indications, and most (>50%) are IPMNs. Most of the debate centers around the concerns of PDAC and/or HGD associated with mucinous cysts (MCN, IPMN, side-branch, main duct, or mixed).

The various guidelines by multiple societies differ in some aspects, such as in selection of patients based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings for up-front surgery or surveillance, the frequency of surveillance based on the size of the cyst and the presence of other concerning cyst features (usually with MRCP), the indications for EUS (both initial and subsequent), importance of the magnitude of growth (most IPMNs slowly grow over a period of time), indications for surgery during surveillance and postsurgery surveillance, and the decision to stop surveillance at some point in time. The literature is replete with small case series reporting a proportion of cancers detected and often ignoring the harms of surgery. Incidence of and mortality caused by PDAC are very low (about 1% for both) in a large national cohort of VA pancreatic cyst patients with long-term follow-up and other studies.

Marcov modeling suggests that none of the guidelines would lead to cost-effective care with low mortality because of overtreatment of low-risk lesions, and a specificity of 67% or more for PDAC/HGB is required. AGA guidelines came close to it but with low sensitivity. Monte Carlo modeling suggests that less intensive strategies, compared with more intensive, result in a similar number of deaths at a much lower cost. While molecular markers in PC fluid are reported to increase the specificity of PDAC/HGD to greater than 70%, it should be observed that such validation was done in a small percentage of patients who had both those markers and resection.

The costs of expensive procedures like EUS, MRI, and surgery, the 3% complication rate with EUS-FNA (primarily acute pancreatitis), and the 1% mortality and approximately 20%-30% morbidity with surgery (bleeding, infection, fistula) and postpancreatectomy diabetes of approximately 30% in the long run need special attention.

In conclusion, one could say pancreas cysts are extremely frequent, most of the neoplastic cysts are mucinous (IPMN and MCN) and slowly growing over time without an associated cancer, and the greatest need at this time is to identify the small proportion of such cysts with PDAC and/or HGD. Until such time, judicious selection of patients for surveillance and reasonable intervals of such surveillance with selective use of EUS will help identify patients requiring resection. In our enthusiasm to detect every possible pancreatic cancer, we should not ignore the unintentional outcomes of surgery to a large majority of patients who would never develop PDAC and the astronomical costs associated with such practice.

Dr. Vege is professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic. He reported having no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819-22.

Lobo JM et al. Surgery. 2020;168:601-9.

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1663-7.

Harris RP. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:787-9.

Dear colleagues,

Pancreas cysts have become almost ubiquitous in this era of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging. They are a common GI consult with patients and providers worried about the potential risk of malignant transformation. Despite significant research over the past few decades, predicting the natural history of these cysts, especially the side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), remains difficult. There have been a variety of expert recommendations and guidelines, but heterogeneity exists in management especially regarding timing of endoscopic ultrasound, imaging surveillance, and cessation of surveillance. Some centers will present these cysts at multidisciplinary conferences, while others will follow general or local algorithms. In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Lauren G. Khanna, assistant professor of medicine at NYU Langone Health, New York, and Dr. Santhi Vege, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., present updated and differing approaches to managing these cysts. Which side of the debate are you on? We welcome your thoughts, questions and input– share with us on Twitter @AGA_GIHN

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Continuing pancreas cyst surveillance indefinitely is reasonable

BY LAUREN G. KHANNA, MD, MS

Pancreas cysts remain a clinical challenge. The true incidence of pancreas cysts is unknown, but from MRI and autopsy series, may be up to 50%. Patients presenting with a pancreas cyst often have significant anxiety about their risk of pancreas cancer. We as a medical community initially did too; but over the past few decades as we have gathered more data, we have become more comfortable observing many pancreas cysts. Yet our recommendations for how, how often, and for how long to evaluate pancreas cysts are still very much under debate; there are multiple guidelines with discordant recommendations. In this article, I will discuss my approach to patients with a pancreas cyst.

At the first evaluation, I review available imaging to see if there are characteristic features to determine the type of pancreas cyst: IPMN (including main duct, branch duct, or mixed type), serous cystic neoplasm (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN), cystic neuroendocrine tumor (NET), or pseudocyst. I also review symptoms, including abdominal pain, weight loss, history of pancreatitis, and onset of diabetes, and check hemoglobin A1c and Ca19-9. I often recommend magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) if it has not already been obtained and is feasible (that is, if a patient does not have severe claustrophobia or a medical device incompatible with MRI). If a patient is not a candidate for treatment should a pancreatic malignancy be identified, because of age, comorbidities, or preference, I recommend no further evaluation.

Where cyst type remains unclear despite MRCP, and for cysts over 2 cm, I recommend endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for fluid sampling to assist in determining cyst type and to rule out any other high-risk features. In accordance with international guidelines, if a patient has any concerning imaging features, including main pancreatic duct dilation >5 mm, solid component or mural nodule, or thickened or enhancing duct walls, regardless of cyst size, I recommend EUS to assess for and biopsy any solid component and to sample cyst fluid to examine for dysplasia. Given the lower sensitivity of CT for high-risk features, if MRCP is not feasible, for cysts 1-2 cm, I recommend EUS for better evaluation.

If a cyst is determined to be a cystic NET; main duct or mixed-type IPMN; MCN; or SPN; or a branch duct IPMN with mural nodule, high-grade dysplasia, or adenocarcinoma, and the patient is a surgical candidate, I refer the patient for surgical evaluation. If a cyst is determined to be an SCA, the malignant potential is minimal, and patients do not require follow-up. Patients with a pseudocyst are managed according to their clinical scenario.

Many patients have a proven or suspected branch duct IPMN, an indeterminate cyst, or multiple cysts. Cyst management during surveillance is then determined by the size of the largest cyst and stability of the cyst(s). Of note, patients with an IPMN also have been shown to have an elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma, which I believe is one of the strongest arguments for heightened surveillance of the entire pancreas in pancreas cyst patients. EUS in particular can identify small or subtle lesions that are not detected by cross-sectional imaging.

If a patient has no prior imaging, in accordance with international and European guidelines, I recommend the first surveillance MRCP at a 6-month interval for cysts <2 cm, which may offer the opportunity to identify rapidly progressing cysts. If a patient has previous imaging available demonstrating stability, I recommend surveillance on an annual basis for cysts <2 cm. For patients with a cyst >2 cm, as above, I recommend EUS, and if there are no concerning features on imaging or EUS, I then recommend annual surveillance.

While the patient is under surveillance, if there is more than minimal cyst growth, a change in cyst appearance, or development of any imaging high-risk feature, pancreatitis, new onset or worsening diabetes, or elevation of Ca19-9, I recommend EUS for further evaluation and consideration of surgery based on EUS findings. If an asymptomatic cyst <2 cm remains stable for 5 years, I offer patients the option to extend imaging to every 2 years, if they are comfortable. In my experience, though, many patients prefer to continue annual imaging. The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines promote stopping surveillance after 5 years of stability, however there are studies demonstrating development of malignancy in cysts that were initially stable over the first 5 years of surveillance. Therefore, I discuss with patients that it is reasonable to continue cyst surveillance indefinitely, until they would no longer be interested in pursuing treatment of any kind if a malignant lesion were to be identified.

There are two special groups of pancreas cyst patients who warrant specific attention. Patients who are at elevated risk of pancreas adenocarcinoma because of an associated genetic mutation or a family history of pancreatic cancer already may be undergoing annual pancreas cancer screening with either MRCP, EUS, or alternating MRCP and EUS. When these high-risk patients also have pancreas cysts, I utilize whichever strategy would image their pancreas most frequently and do not extend beyond 1-year intervals. Another special group is patients who have undergone partial pancreatectomy for IPMN. As discussed above, given the elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma in IPMN patients, I recommend indefinite continued surveillance of the remaining pancreas parenchyma in these patients.

Given the prevalence of pancreas cysts, it certainly would be convenient if guidelines were straightforward enough for primary care physicians to manage pancreas cyst surveillance, as they do for breast cancer screening. However, the complexities of pancreas cysts necessitate the expertise of gastroenterologists and pancreas surgeons, and a multidisciplinary team approach is best where possible.

Dr. Khanna is chief, advanced endoscopy, Tisch Hospital; director, NYU Advanced Endoscopy Fellowship; assistant professor of medicine, NYU Langone Health. Email: [email protected]. There are no relevant conflicts to disclose.

References

Tanaka M et al. Pancreatology. 2017 Sep-Oct;17(5):738-75.

Sahora K et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 Feb;42(2):197-204.

Del Chiaro M et al. Gut. 2018 May;67(5):789-804

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015 Apr;148(4):819-22

Petrone MC et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun 13;9(6):158

Pancreas cysts: More is not necessarily better!

BY SANTHI SWAROOP VEGE, MD

Pancreas cysts (PC) are very common, incidental findings on cross-sectional imaging, performed for non–pancreas-related symptoms. The important issues in management of patients with PC in my practice are the prevalence, natural history, frequency of occurrence of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and/or pancreatic cancer (PDAC), concerning clinical symptoms and imaging findings, indications for EUS and fine-needle aspiration cytology, ideal method and frequency of surveillance, indications for surgery (up front and during follow-up), follow-up after surgery, stopping surveillance, costs, and unintentional harms of management. Good population-based evidence regarding many of the issues described above does not exist, and all information is from selected clinic, radiology, EUS, and surgical cohorts (very important when trying to assess the publications). Cohort studies should start with all PC undergoing surveillance and assess various outcomes, rather than looking backward from EUS or surgical cohorts.

The 2015 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on asymptomatic neoplastic pancreas cysts, which I coauthored, recommend, consistent with principles of High Value Care (minimal unintentional harms and cost effectiveness), that two of three high-risk features (mural nodule, cyst size greater than 3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct) be present for EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). By the same token, they advise surgery for those with two of three high-risk features and or concerning features on EUS and cytology. Finally, they suggest stopping surveillance at 5 years if there are no significant changes. Rigorous GRADE methodology along with systematic review of all relevant questions (rather than cohorts of 500 or fewer patients) formed the basis of the guidelines. Those meta-analyses showed that risk of PDAC in mural nodules, cyst size >3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct, while elevated, still is very low in absolute terms. Less than 20% of resections for highly selected, high-risk cysts showed PDAC. The guidelines were met with a lot of resistance from several societies and physician groups. The recommendations for stopping surveillance after 5 years and no surveillance for absent or low-grade dysplasia after surgery are hotly contested, and these areas need larger, long-term studies.

The whole area of cyst fluid molecular markers that would suggest mucinous type (KRAS and GNAS mutations) and, more importantly, the presence or imminent development of PDAC (next-generation sequencing or NGS) is an exciting field. One sincerely hopes that there will be a breakthrough in this area to achieve the holy grail. Cost effectiveness studies demonstrate the futility of existing guidelines and favor a less intensive approach. Guidelines are only a general framework, and management of individual patients in the clinic is entirely at the discretion of the treating physician. One should make every attempt to detect advanced lesions in PC, but such effort should not subject a large majority of patients to unintentional harms by overtreatment and add further to the burgeoning health care costs in the country.

PC are extremely common (10% of all abdominal imaging), increase with age, are seen in as many as 40%-50% of MRI examinations for nonpancreatic indications, and most (>50%) are IPMNs. Most of the debate centers around the concerns of PDAC and/or HGD associated with mucinous cysts (MCN, IPMN, side-branch, main duct, or mixed).

The various guidelines by multiple societies differ in some aspects, such as in selection of patients based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings for up-front surgery or surveillance, the frequency of surveillance based on the size of the cyst and the presence of other concerning cyst features (usually with MRCP), the indications for EUS (both initial and subsequent), importance of the magnitude of growth (most IPMNs slowly grow over a period of time), indications for surgery during surveillance and postsurgery surveillance, and the decision to stop surveillance at some point in time. The literature is replete with small case series reporting a proportion of cancers detected and often ignoring the harms of surgery. Incidence of and mortality caused by PDAC are very low (about 1% for both) in a large national cohort of VA pancreatic cyst patients with long-term follow-up and other studies.

Marcov modeling suggests that none of the guidelines would lead to cost-effective care with low mortality because of overtreatment of low-risk lesions, and a specificity of 67% or more for PDAC/HGB is required. AGA guidelines came close to it but with low sensitivity. Monte Carlo modeling suggests that less intensive strategies, compared with more intensive, result in a similar number of deaths at a much lower cost. While molecular markers in PC fluid are reported to increase the specificity of PDAC/HGD to greater than 70%, it should be observed that such validation was done in a small percentage of patients who had both those markers and resection.

The costs of expensive procedures like EUS, MRI, and surgery, the 3% complication rate with EUS-FNA (primarily acute pancreatitis), and the 1% mortality and approximately 20%-30% morbidity with surgery (bleeding, infection, fistula) and postpancreatectomy diabetes of approximately 30% in the long run need special attention.

In conclusion, one could say pancreas cysts are extremely frequent, most of the neoplastic cysts are mucinous (IPMN and MCN) and slowly growing over time without an associated cancer, and the greatest need at this time is to identify the small proportion of such cysts with PDAC and/or HGD. Until such time, judicious selection of patients for surveillance and reasonable intervals of such surveillance with selective use of EUS will help identify patients requiring resection. In our enthusiasm to detect every possible pancreatic cancer, we should not ignore the unintentional outcomes of surgery to a large majority of patients who would never develop PDAC and the astronomical costs associated with such practice.

Dr. Vege is professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic. He reported having no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819-22.

Lobo JM et al. Surgery. 2020;168:601-9.

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1663-7.

Harris RP. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:787-9.

Dear colleagues,

Pancreas cysts have become almost ubiquitous in this era of high-resolution cross-sectional imaging. They are a common GI consult with patients and providers worried about the potential risk of malignant transformation. Despite significant research over the past few decades, predicting the natural history of these cysts, especially the side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs), remains difficult. There have been a variety of expert recommendations and guidelines, but heterogeneity exists in management especially regarding timing of endoscopic ultrasound, imaging surveillance, and cessation of surveillance. Some centers will present these cysts at multidisciplinary conferences, while others will follow general or local algorithms. In this issue of Perspectives, Dr. Lauren G. Khanna, assistant professor of medicine at NYU Langone Health, New York, and Dr. Santhi Vege, professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., present updated and differing approaches to managing these cysts. Which side of the debate are you on? We welcome your thoughts, questions and input– share with us on Twitter @AGA_GIHN

Gyanprakash A. Ketwaroo, MD, MSc, is associate professor of medicine, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and chief of endoscopy at West Haven (Conn.) VA Medical Center. He is an associate editor for GI & Hepatology News.

Continuing pancreas cyst surveillance indefinitely is reasonable

BY LAUREN G. KHANNA, MD, MS

Pancreas cysts remain a clinical challenge. The true incidence of pancreas cysts is unknown, but from MRI and autopsy series, may be up to 50%. Patients presenting with a pancreas cyst often have significant anxiety about their risk of pancreas cancer. We as a medical community initially did too; but over the past few decades as we have gathered more data, we have become more comfortable observing many pancreas cysts. Yet our recommendations for how, how often, and for how long to evaluate pancreas cysts are still very much under debate; there are multiple guidelines with discordant recommendations. In this article, I will discuss my approach to patients with a pancreas cyst.

At the first evaluation, I review available imaging to see if there are characteristic features to determine the type of pancreas cyst: IPMN (including main duct, branch duct, or mixed type), serous cystic neoplasm (SCA), mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN), solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN), cystic neuroendocrine tumor (NET), or pseudocyst. I also review symptoms, including abdominal pain, weight loss, history of pancreatitis, and onset of diabetes, and check hemoglobin A1c and Ca19-9. I often recommend magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) if it has not already been obtained and is feasible (that is, if a patient does not have severe claustrophobia or a medical device incompatible with MRI). If a patient is not a candidate for treatment should a pancreatic malignancy be identified, because of age, comorbidities, or preference, I recommend no further evaluation.

Where cyst type remains unclear despite MRCP, and for cysts over 2 cm, I recommend endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for fluid sampling to assist in determining cyst type and to rule out any other high-risk features. In accordance with international guidelines, if a patient has any concerning imaging features, including main pancreatic duct dilation >5 mm, solid component or mural nodule, or thickened or enhancing duct walls, regardless of cyst size, I recommend EUS to assess for and biopsy any solid component and to sample cyst fluid to examine for dysplasia. Given the lower sensitivity of CT for high-risk features, if MRCP is not feasible, for cysts 1-2 cm, I recommend EUS for better evaluation.

If a cyst is determined to be a cystic NET; main duct or mixed-type IPMN; MCN; or SPN; or a branch duct IPMN with mural nodule, high-grade dysplasia, or adenocarcinoma, and the patient is a surgical candidate, I refer the patient for surgical evaluation. If a cyst is determined to be an SCA, the malignant potential is minimal, and patients do not require follow-up. Patients with a pseudocyst are managed according to their clinical scenario.

Many patients have a proven or suspected branch duct IPMN, an indeterminate cyst, or multiple cysts. Cyst management during surveillance is then determined by the size of the largest cyst and stability of the cyst(s). Of note, patients with an IPMN also have been shown to have an elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma, which I believe is one of the strongest arguments for heightened surveillance of the entire pancreas in pancreas cyst patients. EUS in particular can identify small or subtle lesions that are not detected by cross-sectional imaging.

If a patient has no prior imaging, in accordance with international and European guidelines, I recommend the first surveillance MRCP at a 6-month interval for cysts <2 cm, which may offer the opportunity to identify rapidly progressing cysts. If a patient has previous imaging available demonstrating stability, I recommend surveillance on an annual basis for cysts <2 cm. For patients with a cyst >2 cm, as above, I recommend EUS, and if there are no concerning features on imaging or EUS, I then recommend annual surveillance.

While the patient is under surveillance, if there is more than minimal cyst growth, a change in cyst appearance, or development of any imaging high-risk feature, pancreatitis, new onset or worsening diabetes, or elevation of Ca19-9, I recommend EUS for further evaluation and consideration of surgery based on EUS findings. If an asymptomatic cyst <2 cm remains stable for 5 years, I offer patients the option to extend imaging to every 2 years, if they are comfortable. In my experience, though, many patients prefer to continue annual imaging. The American Gastroenterological Association guidelines promote stopping surveillance after 5 years of stability, however there are studies demonstrating development of malignancy in cysts that were initially stable over the first 5 years of surveillance. Therefore, I discuss with patients that it is reasonable to continue cyst surveillance indefinitely, until they would no longer be interested in pursuing treatment of any kind if a malignant lesion were to be identified.

There are two special groups of pancreas cyst patients who warrant specific attention. Patients who are at elevated risk of pancreas adenocarcinoma because of an associated genetic mutation or a family history of pancreatic cancer already may be undergoing annual pancreas cancer screening with either MRCP, EUS, or alternating MRCP and EUS. When these high-risk patients also have pancreas cysts, I utilize whichever strategy would image their pancreas most frequently and do not extend beyond 1-year intervals. Another special group is patients who have undergone partial pancreatectomy for IPMN. As discussed above, given the elevated risk of concurrent pancreas adenocarcinoma in IPMN patients, I recommend indefinite continued surveillance of the remaining pancreas parenchyma in these patients.

Given the prevalence of pancreas cysts, it certainly would be convenient if guidelines were straightforward enough for primary care physicians to manage pancreas cyst surveillance, as they do for breast cancer screening. However, the complexities of pancreas cysts necessitate the expertise of gastroenterologists and pancreas surgeons, and a multidisciplinary team approach is best where possible.

Dr. Khanna is chief, advanced endoscopy, Tisch Hospital; director, NYU Advanced Endoscopy Fellowship; assistant professor of medicine, NYU Langone Health. Email: [email protected]. There are no relevant conflicts to disclose.

References

Tanaka M et al. Pancreatology. 2017 Sep-Oct;17(5):738-75.

Sahora K et al. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016 Feb;42(2):197-204.

Del Chiaro M et al. Gut. 2018 May;67(5):789-804

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015 Apr;148(4):819-22

Petrone MC et al. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2018 Jun 13;9(6):158

Pancreas cysts: More is not necessarily better!

BY SANTHI SWAROOP VEGE, MD

Pancreas cysts (PC) are very common, incidental findings on cross-sectional imaging, performed for non–pancreas-related symptoms. The important issues in management of patients with PC in my practice are the prevalence, natural history, frequency of occurrence of high-grade dysplasia (HGD) and/or pancreatic cancer (PDAC), concerning clinical symptoms and imaging findings, indications for EUS and fine-needle aspiration cytology, ideal method and frequency of surveillance, indications for surgery (up front and during follow-up), follow-up after surgery, stopping surveillance, costs, and unintentional harms of management. Good population-based evidence regarding many of the issues described above does not exist, and all information is from selected clinic, radiology, EUS, and surgical cohorts (very important when trying to assess the publications). Cohort studies should start with all PC undergoing surveillance and assess various outcomes, rather than looking backward from EUS or surgical cohorts.

The 2015 American Gastroenterological Association guidelines on asymptomatic neoplastic pancreas cysts, which I coauthored, recommend, consistent with principles of High Value Care (minimal unintentional harms and cost effectiveness), that two of three high-risk features (mural nodule, cyst size greater than 3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct) be present for EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA). By the same token, they advise surgery for those with two of three high-risk features and or concerning features on EUS and cytology. Finally, they suggest stopping surveillance at 5 years if there are no significant changes. Rigorous GRADE methodology along with systematic review of all relevant questions (rather than cohorts of 500 or fewer patients) formed the basis of the guidelines. Those meta-analyses showed that risk of PDAC in mural nodules, cyst size >3 cm, and dilated pancreatic duct, while elevated, still is very low in absolute terms. Less than 20% of resections for highly selected, high-risk cysts showed PDAC. The guidelines were met with a lot of resistance from several societies and physician groups. The recommendations for stopping surveillance after 5 years and no surveillance for absent or low-grade dysplasia after surgery are hotly contested, and these areas need larger, long-term studies.

The whole area of cyst fluid molecular markers that would suggest mucinous type (KRAS and GNAS mutations) and, more importantly, the presence or imminent development of PDAC (next-generation sequencing or NGS) is an exciting field. One sincerely hopes that there will be a breakthrough in this area to achieve the holy grail. Cost effectiveness studies demonstrate the futility of existing guidelines and favor a less intensive approach. Guidelines are only a general framework, and management of individual patients in the clinic is entirely at the discretion of the treating physician. One should make every attempt to detect advanced lesions in PC, but such effort should not subject a large majority of patients to unintentional harms by overtreatment and add further to the burgeoning health care costs in the country.

PC are extremely common (10% of all abdominal imaging), increase with age, are seen in as many as 40%-50% of MRI examinations for nonpancreatic indications, and most (>50%) are IPMNs. Most of the debate centers around the concerns of PDAC and/or HGD associated with mucinous cysts (MCN, IPMN, side-branch, main duct, or mixed).

The various guidelines by multiple societies differ in some aspects, such as in selection of patients based on clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings for up-front surgery or surveillance, the frequency of surveillance based on the size of the cyst and the presence of other concerning cyst features (usually with MRCP), the indications for EUS (both initial and subsequent), importance of the magnitude of growth (most IPMNs slowly grow over a period of time), indications for surgery during surveillance and postsurgery surveillance, and the decision to stop surveillance at some point in time. The literature is replete with small case series reporting a proportion of cancers detected and often ignoring the harms of surgery. Incidence of and mortality caused by PDAC are very low (about 1% for both) in a large national cohort of VA pancreatic cyst patients with long-term follow-up and other studies.

Marcov modeling suggests that none of the guidelines would lead to cost-effective care with low mortality because of overtreatment of low-risk lesions, and a specificity of 67% or more for PDAC/HGB is required. AGA guidelines came close to it but with low sensitivity. Monte Carlo modeling suggests that less intensive strategies, compared with more intensive, result in a similar number of deaths at a much lower cost. While molecular markers in PC fluid are reported to increase the specificity of PDAC/HGD to greater than 70%, it should be observed that such validation was done in a small percentage of patients who had both those markers and resection.

The costs of expensive procedures like EUS, MRI, and surgery, the 3% complication rate with EUS-FNA (primarily acute pancreatitis), and the 1% mortality and approximately 20%-30% morbidity with surgery (bleeding, infection, fistula) and postpancreatectomy diabetes of approximately 30% in the long run need special attention.

In conclusion, one could say pancreas cysts are extremely frequent, most of the neoplastic cysts are mucinous (IPMN and MCN) and slowly growing over time without an associated cancer, and the greatest need at this time is to identify the small proportion of such cysts with PDAC and/or HGD. Until such time, judicious selection of patients for surveillance and reasonable intervals of such surveillance with selective use of EUS will help identify patients requiring resection. In our enthusiasm to detect every possible pancreatic cancer, we should not ignore the unintentional outcomes of surgery to a large majority of patients who would never develop PDAC and the astronomical costs associated with such practice.

Dr. Vege is professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic. He reported having no conflicts of interest regarding this article.

References

Vege SS et al. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:819-22.

Lobo JM et al. Surgery. 2020;168:601-9.

Lennon AM and Vege SS. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:1663-7.

Harris RP. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:787-9.

Spring reflections

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Dear friends,

I celebrate my achievements (both personal and work related), try not to be too hard on myself with unaccomplished tasks, and plan goals for the upcoming year. Most importantly, it’s a time to be grateful for both opportunities and challenges. Thank you for your engagement with The New Gastroenterologist, and as you go through this issue, I hope you can find time for some spring reflections as well!

In this issue’s In Focus, Dr. Tanisha Ronnie, Dr. Lauren Bloomberg, and Dr. Mukund Venu break down the approach to a patient with dysphagia, a common and difficult encounter in GI practice. They emphasize the importance of a good clinical history as well as understanding the role of diagnostic testing. In our Short Clinical Review section, Dr. Noa Krugliak Cleveland and Dr. David Rubin review the rising role of intestinal ultrasound in inflammatory bowel disease, how to be trained, and how to incorporate it in clinical practice.

As early-career gastroenterologists, Dr. Samad Soudagar and Dr. Mohammad Bilal were tasked with establishing an advanced endoscopy practice, which may be overwhelming for many. They synthesized their experiences into 10 practical tips to build a successful practice. Our Post-fellowship Pathways article highlights Dr. Katie Hutchins’s journey from private practice to academic medicine; she provides insights into the life-changing decision and what she learned about herself to make that pivot.

In our Finance section, Dr. Kelly Hathorn and Dr. David Creighton reflect on navigating as new parents while both working full time in medicine; their article weighs the pros and cons of various childcare options in the post–COVID pandemic world.

In an additional contribution this issue, gastroenterology and hepatology fellowship program leaders at the University of Florida, Gainesville, describe their experience with virtual recruitment, including feedback from their candidates, especially as we enter another cycle of GI Match.

If you are interested in contributing or have ideas for future TNG topics, please contact me ([email protected]), or Jillian Schweitzer ([email protected]), managing editor of TNG.

Until next time, I leave you with a historical fun fact, because we would not be where we are without appreciating where we were: The first formalized gastroenterology fellowship curriculum was a joint publication by four major GI and hepatology societies in 1996 – just 27 years ago!

Yours truly,

Judy A Trieu, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Advanced Endoscopy Fellow

Division of gastroenterology & hepatology

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Taking a global leap into GI technology

Sharmila Anandasabapathy, MD, knew she wanted to focus on endoscopy when she first started her career.

While leading an endoscopy unit in New York City, Dr. Anandasabapathy began developing endoscopic and imaging technologies for underresourced and underserved areas. These technologies eventually made their way into global clinical trials.

“We’ve gone to clinical trial in over 2,000 patients worldwide. When I made that jump into global GI, I was able to make that jump into global health in general,” said Dr. Anandasabapathy.

As vice president for global programs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Dr. Anandasabapathy currently focuses on clinical and translational research.

“We’re looking at the development of new, low-cost devices for early cancer detection in GI globally. I oversee our global programs across the whole college, so it’s GI, it’s surgery, it’s anesthesia, it’s obstetrics, it’s everything.”

In an interview, Dr. Anandasabapathy discussed what attracted her to gastroenterology and why she always takes the time to smile at her patients.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

A: There’s two questions in there: Why I chose GI and why I chose endoscopy.

I chose GI because when I was in my internal medicine training, they seemed like the happiest people in the hospital. They liked what they did. You could make a meaningful impact even at 3 a.m. if you were coming in for a variceal bleed. Everybody seemed happy with their choice of specialty. I was ready to be an oncologist, and I ended up becoming a gastroenterologist.

I chose endoscopy because it was where I wanted to be when I woke up in the morning. I was happy there. I love the procedures; I love the hand-eye coordination. I liked the fact that these were relatively shorter procedures, that it was technology based, and there was infinite growth.

Q: Was there a time when you really helped a patient by doing that endoscopy, preventing Barrett’s esophagus or even cancer?

A: I can think of several times where we had early cancers and it was a question between endoscopic treatment or surgery. It was always discussed with the surgeons. We made the decision within a multidisciplinary group and with the patient, but we usually went with the endoscopic options and the patients have done great. We’ve given them a greater quality of life, and I think that’s really rewarding.

Q: What gives you the most joy in your day-to-day practice?

A: My patients. I work with Barrett’s esophagus patients, and they tend to be well informed about the research and the science. I’m lucky to have a patient population that is really interested and willing to participate in that. I also like my students, my junior faculty. I like teaching and the global application of teaching.

Q: What fears did you have to push past to get to where you are in your career?

A: That I would never become an independent researcher and do it alone. I was able to, over time. The ability to transition from being independent to teaching others and making them independent is a wonderful one.

Early on when I was doing GI, I remember looking at my division, and there were about 58 gastroenterologists and only 2 women. I thought at the time, “Well, can I do it? Is this a field that is conducive with being a woman and having a family?” It turned out that it is. Today, I’m really gratified to see that there are more women in GI than there ever were before.

Q: Have you ever received advice that you’ve ignored?A: Yes. Early in my training in internal medicine, I was told that I smiled too much and that my personality was such that patients and others would think I was too glib. Medicine was a serious business, and you shouldn’t be smiling. That’s not my personality – I’m not Eeyore. I think it’s served me well to be positive, and it’s served me well with patients to be smiling. Especially when you’re dealing with patients who have precancer or dysplasia and are scared – they want reassurance and they want a level of confidence. I’m glad I ignored that advice.

Q: What would be your advice to medical students?

A: Think about where you want to be when you wake up in the morning. If it’s either in a GI practice or doing GI research or doing endoscopy, then you should absolutely do it.

Lightning round

Cat person or dog person

Dog

Favorite sport

Tennis

What song do you have to sing along with when you hear it?

Dancing Queen

Favorite music genre

1980s pop

Favorite movie, show, or book

Wuthering Heights

Dr. Anandasabapathy is on LinkedIn and on Twitter at @anandasabapathy , @bcmglobalhealth , and @bcm_gihep .

Sharmila Anandasabapathy, MD, knew she wanted to focus on endoscopy when she first started her career.

While leading an endoscopy unit in New York City, Dr. Anandasabapathy began developing endoscopic and imaging technologies for underresourced and underserved areas. These technologies eventually made their way into global clinical trials.

“We’ve gone to clinical trial in over 2,000 patients worldwide. When I made that jump into global GI, I was able to make that jump into global health in general,” said Dr. Anandasabapathy.

As vice president for global programs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Dr. Anandasabapathy currently focuses on clinical and translational research.

“We’re looking at the development of new, low-cost devices for early cancer detection in GI globally. I oversee our global programs across the whole college, so it’s GI, it’s surgery, it’s anesthesia, it’s obstetrics, it’s everything.”

In an interview, Dr. Anandasabapathy discussed what attracted her to gastroenterology and why she always takes the time to smile at her patients.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

A: There’s two questions in there: Why I chose GI and why I chose endoscopy.

I chose GI because when I was in my internal medicine training, they seemed like the happiest people in the hospital. They liked what they did. You could make a meaningful impact even at 3 a.m. if you were coming in for a variceal bleed. Everybody seemed happy with their choice of specialty. I was ready to be an oncologist, and I ended up becoming a gastroenterologist.

I chose endoscopy because it was where I wanted to be when I woke up in the morning. I was happy there. I love the procedures; I love the hand-eye coordination. I liked the fact that these were relatively shorter procedures, that it was technology based, and there was infinite growth.

Q: Was there a time when you really helped a patient by doing that endoscopy, preventing Barrett’s esophagus or even cancer?

A: I can think of several times where we had early cancers and it was a question between endoscopic treatment or surgery. It was always discussed with the surgeons. We made the decision within a multidisciplinary group and with the patient, but we usually went with the endoscopic options and the patients have done great. We’ve given them a greater quality of life, and I think that’s really rewarding.

Q: What gives you the most joy in your day-to-day practice?

A: My patients. I work with Barrett’s esophagus patients, and they tend to be well informed about the research and the science. I’m lucky to have a patient population that is really interested and willing to participate in that. I also like my students, my junior faculty. I like teaching and the global application of teaching.

Q: What fears did you have to push past to get to where you are in your career?

A: That I would never become an independent researcher and do it alone. I was able to, over time. The ability to transition from being independent to teaching others and making them independent is a wonderful one.

Early on when I was doing GI, I remember looking at my division, and there were about 58 gastroenterologists and only 2 women. I thought at the time, “Well, can I do it? Is this a field that is conducive with being a woman and having a family?” It turned out that it is. Today, I’m really gratified to see that there are more women in GI than there ever were before.

Q: Have you ever received advice that you’ve ignored?A: Yes. Early in my training in internal medicine, I was told that I smiled too much and that my personality was such that patients and others would think I was too glib. Medicine was a serious business, and you shouldn’t be smiling. That’s not my personality – I’m not Eeyore. I think it’s served me well to be positive, and it’s served me well with patients to be smiling. Especially when you’re dealing with patients who have precancer or dysplasia and are scared – they want reassurance and they want a level of confidence. I’m glad I ignored that advice.

Q: What would be your advice to medical students?

A: Think about where you want to be when you wake up in the morning. If it’s either in a GI practice or doing GI research or doing endoscopy, then you should absolutely do it.

Lightning round

Cat person or dog person

Dog

Favorite sport

Tennis

What song do you have to sing along with when you hear it?

Dancing Queen

Favorite music genre

1980s pop

Favorite movie, show, or book

Wuthering Heights

Dr. Anandasabapathy is on LinkedIn and on Twitter at @anandasabapathy , @bcmglobalhealth , and @bcm_gihep .

Sharmila Anandasabapathy, MD, knew she wanted to focus on endoscopy when she first started her career.

While leading an endoscopy unit in New York City, Dr. Anandasabapathy began developing endoscopic and imaging technologies for underresourced and underserved areas. These technologies eventually made their way into global clinical trials.

“We’ve gone to clinical trial in over 2,000 patients worldwide. When I made that jump into global GI, I was able to make that jump into global health in general,” said Dr. Anandasabapathy.

As vice president for global programs at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Dr. Anandasabapathy currently focuses on clinical and translational research.

“We’re looking at the development of new, low-cost devices for early cancer detection in GI globally. I oversee our global programs across the whole college, so it’s GI, it’s surgery, it’s anesthesia, it’s obstetrics, it’s everything.”

In an interview, Dr. Anandasabapathy discussed what attracted her to gastroenterology and why she always takes the time to smile at her patients.

Q: Why did you choose GI?

A: There’s two questions in there: Why I chose GI and why I chose endoscopy.

I chose GI because when I was in my internal medicine training, they seemed like the happiest people in the hospital. They liked what they did. You could make a meaningful impact even at 3 a.m. if you were coming in for a variceal bleed. Everybody seemed happy with their choice of specialty. I was ready to be an oncologist, and I ended up becoming a gastroenterologist.

I chose endoscopy because it was where I wanted to be when I woke up in the morning. I was happy there. I love the procedures; I love the hand-eye coordination. I liked the fact that these were relatively shorter procedures, that it was technology based, and there was infinite growth.

Q: Was there a time when you really helped a patient by doing that endoscopy, preventing Barrett’s esophagus or even cancer?

A: I can think of several times where we had early cancers and it was a question between endoscopic treatment or surgery. It was always discussed with the surgeons. We made the decision within a multidisciplinary group and with the patient, but we usually went with the endoscopic options and the patients have done great. We’ve given them a greater quality of life, and I think that’s really rewarding.

Q: What gives you the most joy in your day-to-day practice?

A: My patients. I work with Barrett’s esophagus patients, and they tend to be well informed about the research and the science. I’m lucky to have a patient population that is really interested and willing to participate in that. I also like my students, my junior faculty. I like teaching and the global application of teaching.

Q: What fears did you have to push past to get to where you are in your career?

A: That I would never become an independent researcher and do it alone. I was able to, over time. The ability to transition from being independent to teaching others and making them independent is a wonderful one.

Early on when I was doing GI, I remember looking at my division, and there were about 58 gastroenterologists and only 2 women. I thought at the time, “Well, can I do it? Is this a field that is conducive with being a woman and having a family?” It turned out that it is. Today, I’m really gratified to see that there are more women in GI than there ever were before.

Q: Have you ever received advice that you’ve ignored?A: Yes. Early in my training in internal medicine, I was told that I smiled too much and that my personality was such that patients and others would think I was too glib. Medicine was a serious business, and you shouldn’t be smiling. That’s not my personality – I’m not Eeyore. I think it’s served me well to be positive, and it’s served me well with patients to be smiling. Especially when you’re dealing with patients who have precancer or dysplasia and are scared – they want reassurance and they want a level of confidence. I’m glad I ignored that advice.

Q: What would be your advice to medical students?

A: Think about where you want to be when you wake up in the morning. If it’s either in a GI practice or doing GI research or doing endoscopy, then you should absolutely do it.

Lightning round

Cat person or dog person

Dog

Favorite sport

Tennis

What song do you have to sing along with when you hear it?

Dancing Queen

Favorite music genre

1980s pop

Favorite movie, show, or book

Wuthering Heights

Dr. Anandasabapathy is on LinkedIn and on Twitter at @anandasabapathy , @bcmglobalhealth , and @bcm_gihep .

News & Perspectives from Ob.Gyn. News

MASTER CLASS

Prepare for endometriosis excision surgery with a multidisciplinary approach

Iris Kerin Orbuch, MD

Director, Advanced Gynecologic Laparoscopy Center, Los Angeles and New York City.

Series introduction

Charles Miller, MD

Professor, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Department of Clinical Sciences, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, Illinois.

As I gained more interest and expertise in the treatment of endometriosis, I became aware of several articles concluding that if a woman sought treatment for chronic pelvic pain with an internist, the diagnosis would be irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); with a urologist, it would be interstitial cystitis; and with a gynecologist, endometriosis. Moreover, there is an increased propensity for IBS and IC in patients with endometriosis. There also is an increased risk of small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), as noted by our guest author for this latest installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery, Iris Orbuch, MD.

Like our guest author, I have also noted increased risk of pelvic floor myalgia. Dr. Orbuch clearly outlines why this occurs. In fact, we can now understand why many patients have multiple pelvic pain–inducing issues compounding their pain secondary to endometriosis and leading to remodeling of the central nervous system. Therefore, it certainly makes sense to follow Dr. Orbuch’s recommendation for a multidisciplinary pre- and postsurgical approach “to downregulate the pain generators.”

Dr. Orbuch is a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon in Los Angeles who specializes in the treatment of patients diagnosed with endometriosis. Dr. Orbuch serves on the Board of Directors of the Foundation of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists and has served as the chair of the AAGL’s Special Interest Group on Endometriosis and Reproductive Surgery. She is the coauthor of the book “Beating Endo —How to Reclaim Your Life From Endometriosis” (New York: HarperCollins; 2019). The book is written for patients but addresses many issues discussed in this installment of the Master Class in Gynecologic Surgery.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/master-class

GYNECOLOGIC ONCOLOGY CONSULT

The perils of CA-125 as a diagnostic tool in patients with adnexal masses

Katherine Tucker, MD

Assistant Professor of Gynecologic Oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

CA-125, or cancer antigen 125, is an epitope (antigen) on the transmembrane glycoprotein MUC16, or mucin 16. This protein is expressed on the surface of tissue derived from embryonic coelomic and Müllerian epithelium including the reproductive tract. CA-125 is also expressed in other tissue such as the pleura, lungs, pericardium, intestines, and kidneys. MUC16 plays an important role in tumor proliferation, invasiveness, and cell motility.1 In patients with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), CA-125 may be found on the surface of ovarian cancer cells. It is shed in the bloodstream and can be quantified using a serum test.

There are a number of CA-125 assays in commercial use, and although none have been deemed to be clinically superior, there can be some differences between assays. It is important, if possible, to use the same assay when following serial CA-125 values. Most frequently, this will mean getting the test through the same laboratory.

https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/gynecologic-oncology-consult

LATEST NEWS

Few women identify breast density as a breast cancer risk

Walter Alexander

A qualitative study of breast cancer screening–age women finds that few women identified breast density as a risk factor for breast cancer.

Most women did not feel confident they knew what actions could mitigate breast cancer risk, leading researchers to the conclusion that comprehensive education about breast cancer risks and prevention strategies is needed.

CDC recommends universal hepatitis B screening of adults

Adults should be tested for hepatitis B virus (HBV) at least once in their lifetime, according to updated guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

This is the first update to HBV screening guidelines since 2008, the agency said.

“Risk-based testing alone has not identified most persons living with chronic HBV infection and is considered inefficient for providers to implement,” the authors write in the new guidance, published in the CDC’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. “Universal screening of adults for HBV infection is cost-effective, compared with risk-based screening and averts liver disease and death. Although a curative treatment is not yet available, early diagnosis and treatment of chronic HBV infections reduces the risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, nd death.”

An estimated 580,000 to 2.4 million individuals are living with HBV infection in the United States, and two-thirds may be unaware they are infected, the agency said.

The virus spreads through contact with blood, semen, and other body fluids of an infected person.

The guidance now recommends using the triple panel (HBsAg, anti-HBs, total anti-HBc) for initial screening.

“It can help identify persons who have an active HBV infection and could be linked to care; have [a] resolved infection and might be susceptible to reactivation (for example, immunosuppressed persons); are susceptible and need vaccination; or are vaccinated,” the authors write.

Ectopic pregnancy risk and levonorgestrel-releasing IUD

Diana Swift

Researchers report that use of any levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system was associated with a significantly increased risk of ectopic pregnancy, compared with other hormonal contraceptives, in a study published in JAMA.