User login

FDA OKs first drug for Rett syndrome

Rett syndrome is a rare, genetic neurodevelopmental disorder that affects about 6,000-9,000 people in the United States, mostly females.

Symptoms typically present between 6 and 18 months of age, with patients experiencing a rapid decline with loss of fine motor and communication skills.

Trofinetide is a synthetic analogue of the amino-terminal tripeptide of insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which occurs naturally in the brain. The drug is designed to treat the core symptoms of Rett syndrome by potentially reducing neuroinflammation and supporting synaptic function.

The approval of trofinetide was supported by results from the pivotal phase 3 LAVENDER study that tested the efficacy and safety of trofinetide vs. placebo in 187 female patients with Rett syndrome, aged 5-20 years.

A total of 93 participants were randomly assigned to twice-daily oral trofinetide, and 94 received placebo for 12 weeks.

After 12 weeks, trofinetide showed a statistically significant improvement from baseline, compared with placebo, on both the caregiver-assessed Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ) and 7-point Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale.

The drug also outperformed placebo at 12 weeks in a key secondary endpoint: the composite score on the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile Infant-Toddler Checklist-Social (CSBS-DP-IT Social), a scale on which caregivers assess nonverbal communication.

The most common adverse events with trofinetide treatment were diarrhea and vomiting. Almost all these events were considered mild or moderate.

‘Historic day’

“This is a historic day for the Rett syndrome community and a meaningful moment for the patients and caregivers who have eagerly awaited the arrival of an approved treatment for this condition,” Melissa Kennedy, MHA, chief executive officer of the International Rett Syndrome Foundation, said in a news release issued by Acadia.

“Rett syndrome is a complicated, devastating disease that affects not only the individual patient, but whole families. With today’s FDA decision, those impacted by Rett have a promising new treatment option that has demonstrated benefit across a variety of Rett symptoms, including those that impact the daily lives of those living with Rett and their loved ones,” Ms. Kennedy said.

Trofinetide is expected to be available in the United States by the end of April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rett syndrome is a rare, genetic neurodevelopmental disorder that affects about 6,000-9,000 people in the United States, mostly females.

Symptoms typically present between 6 and 18 months of age, with patients experiencing a rapid decline with loss of fine motor and communication skills.

Trofinetide is a synthetic analogue of the amino-terminal tripeptide of insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which occurs naturally in the brain. The drug is designed to treat the core symptoms of Rett syndrome by potentially reducing neuroinflammation and supporting synaptic function.

The approval of trofinetide was supported by results from the pivotal phase 3 LAVENDER study that tested the efficacy and safety of trofinetide vs. placebo in 187 female patients with Rett syndrome, aged 5-20 years.

A total of 93 participants were randomly assigned to twice-daily oral trofinetide, and 94 received placebo for 12 weeks.

After 12 weeks, trofinetide showed a statistically significant improvement from baseline, compared with placebo, on both the caregiver-assessed Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ) and 7-point Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale.

The drug also outperformed placebo at 12 weeks in a key secondary endpoint: the composite score on the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile Infant-Toddler Checklist-Social (CSBS-DP-IT Social), a scale on which caregivers assess nonverbal communication.

The most common adverse events with trofinetide treatment were diarrhea and vomiting. Almost all these events were considered mild or moderate.

‘Historic day’

“This is a historic day for the Rett syndrome community and a meaningful moment for the patients and caregivers who have eagerly awaited the arrival of an approved treatment for this condition,” Melissa Kennedy, MHA, chief executive officer of the International Rett Syndrome Foundation, said in a news release issued by Acadia.

“Rett syndrome is a complicated, devastating disease that affects not only the individual patient, but whole families. With today’s FDA decision, those impacted by Rett have a promising new treatment option that has demonstrated benefit across a variety of Rett symptoms, including those that impact the daily lives of those living with Rett and their loved ones,” Ms. Kennedy said.

Trofinetide is expected to be available in the United States by the end of April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Rett syndrome is a rare, genetic neurodevelopmental disorder that affects about 6,000-9,000 people in the United States, mostly females.

Symptoms typically present between 6 and 18 months of age, with patients experiencing a rapid decline with loss of fine motor and communication skills.

Trofinetide is a synthetic analogue of the amino-terminal tripeptide of insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which occurs naturally in the brain. The drug is designed to treat the core symptoms of Rett syndrome by potentially reducing neuroinflammation and supporting synaptic function.

The approval of trofinetide was supported by results from the pivotal phase 3 LAVENDER study that tested the efficacy and safety of trofinetide vs. placebo in 187 female patients with Rett syndrome, aged 5-20 years.

A total of 93 participants were randomly assigned to twice-daily oral trofinetide, and 94 received placebo for 12 weeks.

After 12 weeks, trofinetide showed a statistically significant improvement from baseline, compared with placebo, on both the caregiver-assessed Rett Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (RSBQ) and 7-point Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I) scale.

The drug also outperformed placebo at 12 weeks in a key secondary endpoint: the composite score on the Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales Developmental Profile Infant-Toddler Checklist-Social (CSBS-DP-IT Social), a scale on which caregivers assess nonverbal communication.

The most common adverse events with trofinetide treatment were diarrhea and vomiting. Almost all these events were considered mild or moderate.

‘Historic day’

“This is a historic day for the Rett syndrome community and a meaningful moment for the patients and caregivers who have eagerly awaited the arrival of an approved treatment for this condition,” Melissa Kennedy, MHA, chief executive officer of the International Rett Syndrome Foundation, said in a news release issued by Acadia.

“Rett syndrome is a complicated, devastating disease that affects not only the individual patient, but whole families. With today’s FDA decision, those impacted by Rett have a promising new treatment option that has demonstrated benefit across a variety of Rett symptoms, including those that impact the daily lives of those living with Rett and their loved ones,” Ms. Kennedy said.

Trofinetide is expected to be available in the United States by the end of April.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

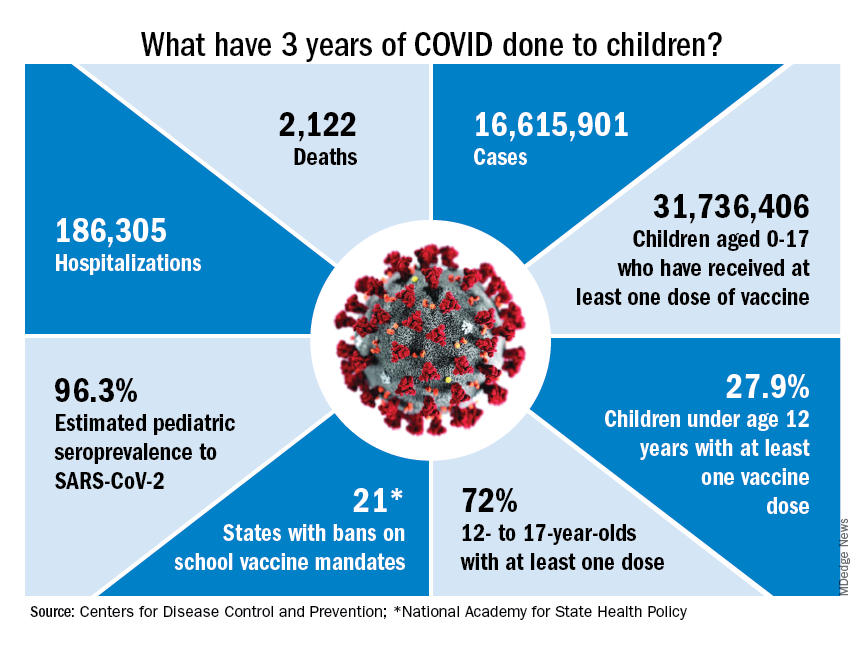

Children and COVID: A look back as the fourth year begins

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

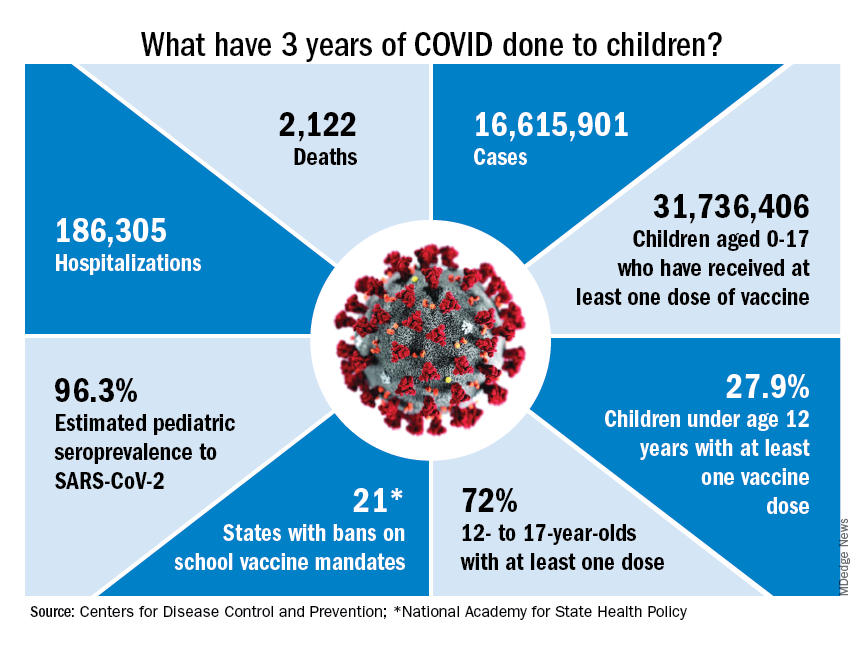

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

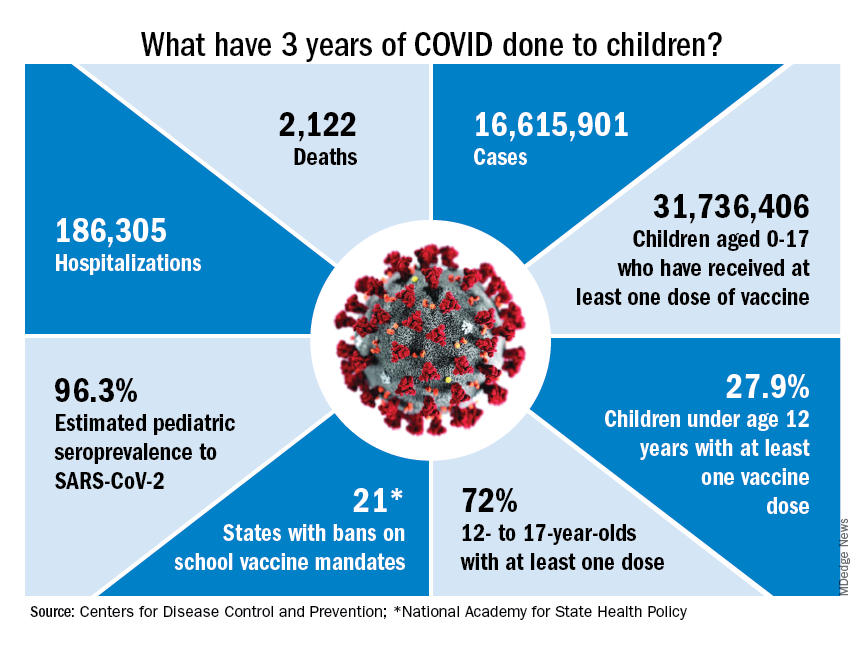

With 3 years of the COVID-19 experience now past, it’s safe to say that SARS-CoV-2 changed American society in ways that could not have been predicted when the first U.S. cases were reported in January of 2020.

Who would have guessed back then that not one but two vaccines would be developed, approved, and widely distributed before the end of the year? Or that those vaccines would be rejected by large segments of the population on ideological grounds? Could anyone have predicted in early 2020 that schools in 21 states would be forbidden by law to require COVID-19 vaccination in students?

Vaccination is generally considered to be an activity of childhood, but that practice has been turned upside down with COVID-19. Among Americans aged 65 years and older, 95% have received at least one dose of vaccine, versus 27.9% of children younger than 12 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The vaccine situation for children mirrors that of the population as a whole. The oldest children have the highest vaccination rates, and the rates decline along with age: 72.0% of those aged 12-17 years have received at least one dose, compared with 39.8% of 5- to 11-year-olds, 10.5% of 2- to 4-year-olds, and 8.0% of children under age 2, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

The youngest children were, of course, the last ones to be eligible for the vaccine, but their uptake has been much slower since emergency use was authorized in June of 2022. In the nearly 9 months since then, 9.5% of children aged 4 and under have received at least one dose, versus 66% of children aged 12-15 years in the first 9 months (May 2021 to March 2022).

Altogether, a total of 31.7 million, or 43%, of all children under age 18 had received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine as of March 8, 2023, according to the most recent CDC data.

Incidence: Counting COVID

Vaccination and other prevention efforts have tried to stem the tide, but what has COVID actually done to children since the Trump administration declared a nationwide emergency on March 13, 2020?

- 16.6 million cases.

- 186,035 new hospital admissions.

- 2,122 deaths.

Even the proportion of total COVID cases in children, 17.2%, is less than might be expected, given their relatively undervaccinated status.

Seroprevalence estimates seem to support the undercounting of pediatric cases. A survey of commercial laboratories working with the CDC put the seroprevalance of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in children at 96.3% as of late 2022, based on tests of almost 27,000 specimens performed over an 8-week period from mid-October to mid-December. That would put the number of infected children at 65.7 million children.

Since Omicron

There has not been another major COVID-19 surge since the winter of 2021-2022, when the weekly rate of new cases reached 1,900 per 100,000 population in children aged 16-17 years in early January 2022 – the highest seen among children of any of the CDC’s age groups (0-4, 5-11, 12-15, 16-17) during the entire pandemic. Since the Omicron surge, the highest weekly rate was 221 per 100,000 during the week of May 15-21, again in 16- to 17-year-olds, the CDC reports.

The widely anticipated surge of COVID in the fall and winter of 2022 and 2023 – the so-called “tripledemic” involving influenza and respiratory syncytial virus – did not occur, possibly because so many Americans were vaccinated or previously infected, experts suggested. New-case rates, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in children have continued to drop as winter comes to a close, CDC data show.

Strong support for CBT as first-line treatment for insomnia in seniors

NEW ORLEANS –

“The lack of awareness among clinicians who take care of older adults that CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment for insomnia is an issue,” Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., told this news organization.

Dr. Tampi was among the speakers during a session as part of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry annual meeting addressing the complex challenges of treating insomnia in older patients, who tend to have higher rates of insomnia than their younger counterparts.

The prevalence of insomnia in older adults is estimated to be 20%-40%, and medication is frequently the first treatment choice, a less than ideal approach, said Dr. Tampi.

“Prescribing sedatives and hypnotics, which can cause severe adverse effects, without a thorough assessment that includes comorbidities that may be causing the insomnia” is among the biggest mistakes clinicians make in the treatment of insomnia in older patients, Dr. Tampi said in an interview.

“It’s our duty as providers to first take a good assessment, talk about polymorbidity, and try to address those conditions, and judiciously use medications in conjunction with at least components of CBT-I,” he said.

Long-term safety, efficacy unclear

About one-third of older adults take at least one form of pharmacological treatment for insomnia symptoms, said Ebony Dix, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a separate talk during the session. This, despite the low-risk profile of CBT and recommendations from various medical societies that CBT should be tried first.

Dr. Dix noted that medications approved for insomnia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, including melatonin receptor agonists, heterocyclics, and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs), can play an important role in the short-term management of insomnia, but their long-term effects are unknown.

“Pharmacotherapeutic agents may be effective in the short term, but there is a lack of sufficient, statistically significant data to support the long-term safety and efficacy of any [sleep] medication, especially in aging adults, due to the impact of hypnotic drugs on sleep architecture, the impact of aging on pharmacokinetics, as well as polypharmacy and drug-to-drug interactions,” Dr. Dix said. She noted that clinical trials of insomnia drugs rarely include geriatric patients.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends CBT-I as first-line treatment for insomnia, with the key benefit being its exemplary safety profile, said Shilpa Srinivasan, MD, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, who also presented during the session.

“The biggest [attribute] of CBT-I management strategies is the low risk of side effects,” she said. “How many medications can we say that about?”

The CBT-I intervention includes a focus on key components of lifestyle and mental health issues to improve sleep. These include the following:

- Strictly restricting sleep hours for bedtime and arising (with napping discouraged).

- Control of stimulus to disrupt falling asleep.

- Cognitive therapy to identify and replace maladaptive beliefs.

- Control of sleep hygiene for optimal sleep.

- Relaxation training.

Keys to success

Dr. Srinivasan noted one recent study of CBT-I among patients aged 60 and older with insomnia and depression. The 156 participants randomized to receive weekly 120-minute CBT-I sessions over 2 months were significantly less likely to develop new or recurrent major depression versus their counterparts randomized to receive sleep education (hazard ratio, 0.51; P = .02).

However, CBT-I is more labor intensive than medication and requires provider training and motivation, and commitment on the part of the patient, to be successful.

“We really need to ensure that even when patients are receiving pharmacologic interventions for insomnia that we provide psychoeducation. At the end of the day, some of these nonpharmacologic components can make or break the success of pharmacotherapy,” said Dr. Srinivasan.

Whether using CBT-I alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy, the intervention does not necessarily have to include all components to be beneficial, she said.

“I think one of the challenges in incorporating CBT-I is the misconception that it is an all-or-nothing approach wherein every modality must be utilized,” she said. “While multicomponent CBT-I has been shown to be effective, the individual components can be incorporated into patient encounters in a stepped approach.”

Informing patients that they have options other than medications and involving them in decision-making is key, she added.

“In the case of insomnia, this is particularly relevant because of the physical and emotional distress that it causes,” Dr. Srinivasan said. “Patients often seek over-the-counter medications or other nonprescribed agents to try to obtain relief even before seeking treatment in a health care setting. There is less awareness about evidence-based and effective nonpharmacologic treatments such as CBT-I.”

Dr. Tampi, Dr. Dix, and Dr. Srinivasan have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

“The lack of awareness among clinicians who take care of older adults that CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment for insomnia is an issue,” Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., told this news organization.

Dr. Tampi was among the speakers during a session as part of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry annual meeting addressing the complex challenges of treating insomnia in older patients, who tend to have higher rates of insomnia than their younger counterparts.

The prevalence of insomnia in older adults is estimated to be 20%-40%, and medication is frequently the first treatment choice, a less than ideal approach, said Dr. Tampi.

“Prescribing sedatives and hypnotics, which can cause severe adverse effects, without a thorough assessment that includes comorbidities that may be causing the insomnia” is among the biggest mistakes clinicians make in the treatment of insomnia in older patients, Dr. Tampi said in an interview.

“It’s our duty as providers to first take a good assessment, talk about polymorbidity, and try to address those conditions, and judiciously use medications in conjunction with at least components of CBT-I,” he said.

Long-term safety, efficacy unclear

About one-third of older adults take at least one form of pharmacological treatment for insomnia symptoms, said Ebony Dix, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a separate talk during the session. This, despite the low-risk profile of CBT and recommendations from various medical societies that CBT should be tried first.

Dr. Dix noted that medications approved for insomnia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, including melatonin receptor agonists, heterocyclics, and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs), can play an important role in the short-term management of insomnia, but their long-term effects are unknown.

“Pharmacotherapeutic agents may be effective in the short term, but there is a lack of sufficient, statistically significant data to support the long-term safety and efficacy of any [sleep] medication, especially in aging adults, due to the impact of hypnotic drugs on sleep architecture, the impact of aging on pharmacokinetics, as well as polypharmacy and drug-to-drug interactions,” Dr. Dix said. She noted that clinical trials of insomnia drugs rarely include geriatric patients.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends CBT-I as first-line treatment for insomnia, with the key benefit being its exemplary safety profile, said Shilpa Srinivasan, MD, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, who also presented during the session.

“The biggest [attribute] of CBT-I management strategies is the low risk of side effects,” she said. “How many medications can we say that about?”

The CBT-I intervention includes a focus on key components of lifestyle and mental health issues to improve sleep. These include the following:

- Strictly restricting sleep hours for bedtime and arising (with napping discouraged).

- Control of stimulus to disrupt falling asleep.

- Cognitive therapy to identify and replace maladaptive beliefs.

- Control of sleep hygiene for optimal sleep.

- Relaxation training.

Keys to success

Dr. Srinivasan noted one recent study of CBT-I among patients aged 60 and older with insomnia and depression. The 156 participants randomized to receive weekly 120-minute CBT-I sessions over 2 months were significantly less likely to develop new or recurrent major depression versus their counterparts randomized to receive sleep education (hazard ratio, 0.51; P = .02).

However, CBT-I is more labor intensive than medication and requires provider training and motivation, and commitment on the part of the patient, to be successful.

“We really need to ensure that even when patients are receiving pharmacologic interventions for insomnia that we provide psychoeducation. At the end of the day, some of these nonpharmacologic components can make or break the success of pharmacotherapy,” said Dr. Srinivasan.

Whether using CBT-I alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy, the intervention does not necessarily have to include all components to be beneficial, she said.

“I think one of the challenges in incorporating CBT-I is the misconception that it is an all-or-nothing approach wherein every modality must be utilized,” she said. “While multicomponent CBT-I has been shown to be effective, the individual components can be incorporated into patient encounters in a stepped approach.”

Informing patients that they have options other than medications and involving them in decision-making is key, she added.

“In the case of insomnia, this is particularly relevant because of the physical and emotional distress that it causes,” Dr. Srinivasan said. “Patients often seek over-the-counter medications or other nonprescribed agents to try to obtain relief even before seeking treatment in a health care setting. There is less awareness about evidence-based and effective nonpharmacologic treatments such as CBT-I.”

Dr. Tampi, Dr. Dix, and Dr. Srinivasan have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS –

“The lack of awareness among clinicians who take care of older adults that CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment for insomnia is an issue,” Rajesh R. Tampi, MD, professor and chairman of the department of psychiatry, Creighton University, Omaha, Neb., told this news organization.

Dr. Tampi was among the speakers during a session as part of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry annual meeting addressing the complex challenges of treating insomnia in older patients, who tend to have higher rates of insomnia than their younger counterparts.

The prevalence of insomnia in older adults is estimated to be 20%-40%, and medication is frequently the first treatment choice, a less than ideal approach, said Dr. Tampi.

“Prescribing sedatives and hypnotics, which can cause severe adverse effects, without a thorough assessment that includes comorbidities that may be causing the insomnia” is among the biggest mistakes clinicians make in the treatment of insomnia in older patients, Dr. Tampi said in an interview.

“It’s our duty as providers to first take a good assessment, talk about polymorbidity, and try to address those conditions, and judiciously use medications in conjunction with at least components of CBT-I,” he said.

Long-term safety, efficacy unclear

About one-third of older adults take at least one form of pharmacological treatment for insomnia symptoms, said Ebony Dix, MD, assistant professor of psychiatry at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., in a separate talk during the session. This, despite the low-risk profile of CBT and recommendations from various medical societies that CBT should be tried first.

Dr. Dix noted that medications approved for insomnia by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, including melatonin receptor agonists, heterocyclics, and dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs), can play an important role in the short-term management of insomnia, but their long-term effects are unknown.

“Pharmacotherapeutic agents may be effective in the short term, but there is a lack of sufficient, statistically significant data to support the long-term safety and efficacy of any [sleep] medication, especially in aging adults, due to the impact of hypnotic drugs on sleep architecture, the impact of aging on pharmacokinetics, as well as polypharmacy and drug-to-drug interactions,” Dr. Dix said. She noted that clinical trials of insomnia drugs rarely include geriatric patients.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends CBT-I as first-line treatment for insomnia, with the key benefit being its exemplary safety profile, said Shilpa Srinivasan, MD, a professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, who also presented during the session.

“The biggest [attribute] of CBT-I management strategies is the low risk of side effects,” she said. “How many medications can we say that about?”

The CBT-I intervention includes a focus on key components of lifestyle and mental health issues to improve sleep. These include the following:

- Strictly restricting sleep hours for bedtime and arising (with napping discouraged).

- Control of stimulus to disrupt falling asleep.

- Cognitive therapy to identify and replace maladaptive beliefs.

- Control of sleep hygiene for optimal sleep.

- Relaxation training.

Keys to success

Dr. Srinivasan noted one recent study of CBT-I among patients aged 60 and older with insomnia and depression. The 156 participants randomized to receive weekly 120-minute CBT-I sessions over 2 months were significantly less likely to develop new or recurrent major depression versus their counterparts randomized to receive sleep education (hazard ratio, 0.51; P = .02).

However, CBT-I is more labor intensive than medication and requires provider training and motivation, and commitment on the part of the patient, to be successful.

“We really need to ensure that even when patients are receiving pharmacologic interventions for insomnia that we provide psychoeducation. At the end of the day, some of these nonpharmacologic components can make or break the success of pharmacotherapy,” said Dr. Srinivasan.

Whether using CBT-I alone or in combination with pharmacotherapy, the intervention does not necessarily have to include all components to be beneficial, she said.

“I think one of the challenges in incorporating CBT-I is the misconception that it is an all-or-nothing approach wherein every modality must be utilized,” she said. “While multicomponent CBT-I has been shown to be effective, the individual components can be incorporated into patient encounters in a stepped approach.”

Informing patients that they have options other than medications and involving them in decision-making is key, she added.

“In the case of insomnia, this is particularly relevant because of the physical and emotional distress that it causes,” Dr. Srinivasan said. “Patients often seek over-the-counter medications or other nonprescribed agents to try to obtain relief even before seeking treatment in a health care setting. There is less awareness about evidence-based and effective nonpharmacologic treatments such as CBT-I.”

Dr. Tampi, Dr. Dix, and Dr. Srinivasan have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT AAGP 2023

Will new guidelines widen the gap in treating childhood obesity?

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that nearly one in five children have obesity. Since the 1980s, the number of children with obesity has been increasing, with each generation reaching higher rates and greater weights at earlier ages. Even with extensive efforts from parents, clinicians, educators, and policymakers to limit the excessive weight gain among children, the number of obesity and severe obesity diagnoses keeps rising.

In response to this critical public health challenge, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced new clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of obesity in children and adolescents. Developed by an expert panel, the new AAP guidelines present a departure in the conceptualization of obesity, recognizing the role that social determinants of health play in contributing to excessive weight gain.

As a community health researcher who investigates disparities in childhood obesity, I applaud the paradigm shift from the AAP. I specifically endorse the recognition that obesity is a very serious metabolic disease that won’t go away unless we introduce systemic changes and effective treatments.

However, I, like so many of my colleagues and anyone aware of the access barriers to the recommended treatments, worry about the consequences that the new guidelines will have in the context of current and future health disparities.

A recent study, published in Pediatrics, showed that childhood obesity disparities are widening. Younger generations of children are reaching higher weights at younger ages. These alarming trends are greater among Black children and children growing up with the greatest socioeconomic disadvantages. The new AAP guidelines – even while driven by good intentions – can exacerbate these differences and set children who are able to live healthy lives further apart from those with disproportionate obesity risks, who lack access to the treatments recommended by the AAP.

Rather than “watchful waiting,” to see if children outgrow obesity, the new guidelines call for “aggressive treatment,” as reported by this news organization. At least 26 hours of in-person intensive health behavior and lifestyle counseling and treatment are recommended for children aged 2 years old or older who meet the obesity criteria. For children aged 12 years or older, the AAP recommends complementing lifestyle counseling with pharmacotherapy. This breakthrough welcomes the use of promising antiobesity medications (for example, orlistat, Wegovy [semaglutide], Saxenda [liraglutide], Qsymia (phentermine and topiramate]) approved by the Food and Drug Administration for long-term use in children aged 12 and up. For children 13 years or older with severe obesity, bariatric surgery should be considered.

Will cost barriers continue to increase disparity?

The very promising semaglutide (Wegovy) is a GLP-1–based medication currently offered for about $1,000 per month. As with other chronic diseases, children should be prepared to take obesity medications for prolonged periods of time. A study conducted in adults found that when the medication is suspended, any weight loss can be regained. The costs of bariatric surgery total over $20,000.

In the U.S. health care system, at current prices, very few of the children in need of the medications or surgical treatments have access to them. Most private health insurance companies and Medicaid reject coverage for childhood obesity treatments. Barriers to treatment access are greater for Black and Hispanic children, children growing up in poverty, and children living in the U.S. South region, all of whom are more likely to develop obesity earlier in life than their White and wealthier counterparts.

The AAP recognized that a substantial time and financial commitment is required to follow the new treatment recommendations. Members of the AAP Expert Committee that developed the guidelines stated that they are “aware of the multitude of barriers to treatment that patients and their families face.”

Nevertheless, the recognition of the role of social determinants of health in the development of childhood obesity didn’t motivate the introduction of treatment options that aren’t unattainable for most U.S. families.

It’s important to step away from the conclusion that because of the price tag, at the population level, the new AAP guidelines will be inconsequential. This conclusion fails to recognize the potential harm that the guidelines may introduce. In the context of childhood obesity disparities, the new treatment recommendations probably will widen the childhood obesity prevalence gap between the haves – who will benefit from the options available to reduce childhood obesity – and the have-nots, whose obesity rates will continue with their growth.

We live in a world of the haves and have-nots. This applies to financial resources as well as obesity rates. In the long term, the optimists hope that the GLP-1 medications will become ubiquitous, generics will be developed, and insurance companies will expand coverage and grant access to most children in need of effective obesity treatment options. Until this happens, unless intentional policies are promptly introduced, childhood obesity disparities will continue to widen.

To avoid the increasing disparities, brave and intentional actions are required. A lack of attention dealt to this known problem will result in a lost opportunity for the AAP, legislators, and others in a position to help U.S. children.

Liliana Aguayo, PhD, MPH, is assistant professor, Clinical Research Track, Hubert Department of Global Health, Emory University, Atlanta. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Firing patients

One might assume that, just as patients are free to accept or reject their doctors, physicians have an equal right to reject their patients; to a certain extent, that is true. There are no specific laws prohibiting a provider from terminating a patient relationship for any reason, other than a discriminatory one – race, nationality, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, and so on. However, the evolution of ever-larger practice environments has raised new questions.

While verbal abuse, inappropriate treatment demands (particularly for controlled substances), refusal to adhere to mutually agreed treatment plans, and failure to keep appointments or pay bills remain the most common reasons for dismissal, evolving practice environments may require us to modify our responses.

What happens, for example, when a patient is banned from a large clinic that employs most of that community’s physicians, or is the only practice in town with the specialists required by that patient? The medical profession does have an obligation to not exclude such patients from care.

In a large cross-specialty system or consolidated specialist practice, firing a patient has a very different level of consequences than in a small office. There must be a balance between separating patients and doctors who don’t get along and seeing that the patient in question receives competent treatment. The physician, as the professional, has a higher standard to live up to with respect to handling this kind of situation.

If the problem is a personality conflict, the solution may be as simple as transferring the patient to another caregiver within the practice. While it does not make sense for a patient to continue seeing a doctor who does not want to see them, it also does not make sense to ban a patient from a large system where there could well be one or more other doctors who would be a good match. If a patient is unable to pay outstanding bills, a large clinic might prohibit them from making new appointments until they have worked out a payment plan rather than firing them outright.

If you are part of a large practice, take the time to research your group’s official policies for dealing with such situations. If there is no written policy, you might want to start that discussion with your colleagues.

The point is that in any practice, large or small, firing a patient should be a last resort. Try to make every effort to resolve the problem amicably. Communicate with the patient in question, explain your concerns, and discuss options for resolution. Take time to listen to the patient, as they may have an explanation (rational or not) for their objectionable behavior.

You can also send a letter, repeating your concerns and proposed solutions, as further documentation of your efforts to achieve an amicable resolution. All verbal and written warnings must, of course, be documented. If the patient has a managed care policy, we review the managed care contract, which sometimes includes specific requirements for dismissal of its patients.

When such efforts fail, we send the patient two letters – one certified with return receipt, the other by conventional first class, in case the patient refuses the certified copy – explaining the reason for dismissal, and that care will be discontinued in 30 days from the letter’s date. (Most attorneys and medical associations agree that 30 days is sufficient reasonable notice.) We offer to provide care during the interim period, include a list of names and contact information for potential alternate providers, and offer to transfer records after receiving written permission.

Following these precautions will usually protect you from charges of “patient abandonment,” which is generally defined as the unilateral severance by the physician of the physician-patient relationship without giving the patient sufficient advance notice to obtain the services of another practitioner, and at a time when the patient still requires medical attention.

Some states have their own unique definitions of patient abandonment. You should check with your state’s health department, and your attorney, for any unusual requirements in your state, because violating them could lead to intervention by your state licensing board. There is also the risk of civil litigation, which is typically not covered by malpractice policies, and may not be covered by your general liability policy either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

One might assume that, just as patients are free to accept or reject their doctors, physicians have an equal right to reject their patients; to a certain extent, that is true. There are no specific laws prohibiting a provider from terminating a patient relationship for any reason, other than a discriminatory one – race, nationality, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, and so on. However, the evolution of ever-larger practice environments has raised new questions.

While verbal abuse, inappropriate treatment demands (particularly for controlled substances), refusal to adhere to mutually agreed treatment plans, and failure to keep appointments or pay bills remain the most common reasons for dismissal, evolving practice environments may require us to modify our responses.

What happens, for example, when a patient is banned from a large clinic that employs most of that community’s physicians, or is the only practice in town with the specialists required by that patient? The medical profession does have an obligation to not exclude such patients from care.

In a large cross-specialty system or consolidated specialist practice, firing a patient has a very different level of consequences than in a small office. There must be a balance between separating patients and doctors who don’t get along and seeing that the patient in question receives competent treatment. The physician, as the professional, has a higher standard to live up to with respect to handling this kind of situation.

If the problem is a personality conflict, the solution may be as simple as transferring the patient to another caregiver within the practice. While it does not make sense for a patient to continue seeing a doctor who does not want to see them, it also does not make sense to ban a patient from a large system where there could well be one or more other doctors who would be a good match. If a patient is unable to pay outstanding bills, a large clinic might prohibit them from making new appointments until they have worked out a payment plan rather than firing them outright.

If you are part of a large practice, take the time to research your group’s official policies for dealing with such situations. If there is no written policy, you might want to start that discussion with your colleagues.

The point is that in any practice, large or small, firing a patient should be a last resort. Try to make every effort to resolve the problem amicably. Communicate with the patient in question, explain your concerns, and discuss options for resolution. Take time to listen to the patient, as they may have an explanation (rational or not) for their objectionable behavior.

You can also send a letter, repeating your concerns and proposed solutions, as further documentation of your efforts to achieve an amicable resolution. All verbal and written warnings must, of course, be documented. If the patient has a managed care policy, we review the managed care contract, which sometimes includes specific requirements for dismissal of its patients.

When such efforts fail, we send the patient two letters – one certified with return receipt, the other by conventional first class, in case the patient refuses the certified copy – explaining the reason for dismissal, and that care will be discontinued in 30 days from the letter’s date. (Most attorneys and medical associations agree that 30 days is sufficient reasonable notice.) We offer to provide care during the interim period, include a list of names and contact information for potential alternate providers, and offer to transfer records after receiving written permission.

Following these precautions will usually protect you from charges of “patient abandonment,” which is generally defined as the unilateral severance by the physician of the physician-patient relationship without giving the patient sufficient advance notice to obtain the services of another practitioner, and at a time when the patient still requires medical attention.

Some states have their own unique definitions of patient abandonment. You should check with your state’s health department, and your attorney, for any unusual requirements in your state, because violating them could lead to intervention by your state licensing board. There is also the risk of civil litigation, which is typically not covered by malpractice policies, and may not be covered by your general liability policy either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

One might assume that, just as patients are free to accept or reject their doctors, physicians have an equal right to reject their patients; to a certain extent, that is true. There are no specific laws prohibiting a provider from terminating a patient relationship for any reason, other than a discriminatory one – race, nationality, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, and so on. However, the evolution of ever-larger practice environments has raised new questions.

While verbal abuse, inappropriate treatment demands (particularly for controlled substances), refusal to adhere to mutually agreed treatment plans, and failure to keep appointments or pay bills remain the most common reasons for dismissal, evolving practice environments may require us to modify our responses.

What happens, for example, when a patient is banned from a large clinic that employs most of that community’s physicians, or is the only practice in town with the specialists required by that patient? The medical profession does have an obligation to not exclude such patients from care.

In a large cross-specialty system or consolidated specialist practice, firing a patient has a very different level of consequences than in a small office. There must be a balance between separating patients and doctors who don’t get along and seeing that the patient in question receives competent treatment. The physician, as the professional, has a higher standard to live up to with respect to handling this kind of situation.

If the problem is a personality conflict, the solution may be as simple as transferring the patient to another caregiver within the practice. While it does not make sense for a patient to continue seeing a doctor who does not want to see them, it also does not make sense to ban a patient from a large system where there could well be one or more other doctors who would be a good match. If a patient is unable to pay outstanding bills, a large clinic might prohibit them from making new appointments until they have worked out a payment plan rather than firing them outright.

If you are part of a large practice, take the time to research your group’s official policies for dealing with such situations. If there is no written policy, you might want to start that discussion with your colleagues.

The point is that in any practice, large or small, firing a patient should be a last resort. Try to make every effort to resolve the problem amicably. Communicate with the patient in question, explain your concerns, and discuss options for resolution. Take time to listen to the patient, as they may have an explanation (rational or not) for their objectionable behavior.

You can also send a letter, repeating your concerns and proposed solutions, as further documentation of your efforts to achieve an amicable resolution. All verbal and written warnings must, of course, be documented. If the patient has a managed care policy, we review the managed care contract, which sometimes includes specific requirements for dismissal of its patients.

When such efforts fail, we send the patient two letters – one certified with return receipt, the other by conventional first class, in case the patient refuses the certified copy – explaining the reason for dismissal, and that care will be discontinued in 30 days from the letter’s date. (Most attorneys and medical associations agree that 30 days is sufficient reasonable notice.) We offer to provide care during the interim period, include a list of names and contact information for potential alternate providers, and offer to transfer records after receiving written permission.

Following these precautions will usually protect you from charges of “patient abandonment,” which is generally defined as the unilateral severance by the physician of the physician-patient relationship without giving the patient sufficient advance notice to obtain the services of another practitioner, and at a time when the patient still requires medical attention.

Some states have their own unique definitions of patient abandonment. You should check with your state’s health department, and your attorney, for any unusual requirements in your state, because violating them could lead to intervention by your state licensing board. There is also the risk of civil litigation, which is typically not covered by malpractice policies, and may not be covered by your general liability policy either.

Dr. Eastern practices dermatology and dermatologic surgery in Belleville, N.J. He is the author of numerous articles and textbook chapters, and is a longtime monthly columnist for Dermatology News. Write to him at [email protected].

New clinical guideline for biliary strictures issued

The recommendations provide guidance on the care of patients with extrahepatic and perihilar strictures, with a focus on diagnosis and drainage. Although some of the principles may apply to intrahepatic strictures, the guideline doesn’t specifically address them. The new guideline is considered separate from the 2015 ACG guideline related to primary sclerosing cholangitis.

“The appropriate diagnosis and management of biliary strictures is still a big clinical challenge and has important implications in endoscopic, surgical, and oncological decision-making,” co-author Jennifer Maranki, MD, a professor of medicine and director of endoscopy at Penn State Hershey Medical Center, said in an interview.

“We wanted to provide the best possible guidance to gastroenterologists based on the available body of literature, with key shifts in diagnosis and management based on currently available modalities and tools,” she said.

The guideline was published in the March issue of the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

The recommendations were developed by a diverse group of authors from across the United States in recognition of the potential influence of commercial and intellectual conflicts of interest. The panel used a systematic process that involved structured literature searches by librarians and independent appraisal of the quality of evidence by dedicated methodologists, the authors write.

Overall, the team outlined 11 recommendations and 12 key concepts. A strong recommendation was made when the benefits of the test or intervention clearly outweighed the potential disadvantages. A conditional recommendation was made when some uncertainty remained about the balance of benefits and harms. Key concepts address important clinical questions that lack adequate evidence to inform recommendations. They are based on indirect evidence and expert opinion.

Epidemiology and diagnosis

The burden of biliary strictures is difficult to estimate, owing to the lack of a specific administrative code. The estimated cost of caring for biliary disease in the United States is about $16.9 billion annually, although this figure includes costs associated with gallbladder disease, choledocholithiasis, and other (nonobstructive) biliary disorders, the authors write.

Among the 57,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer each year, at least 60% will cause obstructive jaundice, resulting in about 34,000 annual cases of malignant extrahepatic biliary stricture, the team notes. In addition, about 3,000 cases of malignant perihilar stricture are expected in the United States each year. Patients may also seek care for benign strictures associated with chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune disease, and post-cholecystectomy injury.

Under the first key concept, the authors note that biliary strictures in adults are more likely to be malignant than benign, except in certain well-defined scenarios. This underscores the importance of having a high index of clinical suspicion during evaluation, they add.

In general, a definitive tissue diagnosis is necessary to guide oncologic and endoscopic care for most strictures that aren’t surgically resectable at the time of presentation. For patients with extrahepatic biliary stricture due to an apparent or suspected pancreatic mass, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle sampling (aspiration or biopsy) is recommended over endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as the preferred method of evaluation for malignancy.

For patients with suspected malignant perihilar stricture, multimodality sampling is recommended over brush cytology alone at the time of the index ERCP.

Guidance on drainage

For management, the principal objective is to restore the physiologic flow of bile into the duodenum. Although there is wide variability in the difficulty and risk of drainage, depending on location and complexity, perihilar strictures are generally more challenging and are riskier to drain than extrahepatic strictures. The goals should be to alleviate symptoms, reduce serum bilirubin to a level such that chemotherapy can be safely administered, and optimize surgical outcomes.

For benign extrahepatic biliary strictures, ERCP is the preferred modality for durable treatment. Fully covered self-expanding metallic stent (SEMS) placement is recommended over multiple plastic stents to reduce the number of procedures required for long-term treatment.

For extrahepatic strictures due to resectable pancreatic cancer or cholangiocarcinoma, the authors recommend against routine preoperative biliary drainage. However, drainage is warranted for some patients, including those with acute cholangitis, severe pruritus, very high serum bilirubin levels, those undergoing neoadjuvant therapy, and those for whom surgery is delayed.

For malignant extrahepatic strictures that are unresectable or borderline resectable, SEMS placement is recommended over plastic stents. The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against uncovered SEMS versus fully covered SEMS.

For perihilar strictures due to suspected malignancy, the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against ERCP versus percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. In addition, for malignant perihilar strictures, the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against plastic stents versus uncovered SEMS.

For perihilar strictures due to cholangiocarcinoma in cases in which resection or transplantation is not possible, adjuvant endobiliary ablation plus plastic stent placement is recommended over plastic stent placement alone.

Overall, for patients with a biliary stricture for which ERCP is indicated but is unsuccessful or impossible, EUS-guided biliary access and drainage is recommended over PTBD, because it is associated with fewer adverse events. However, these interventional EUS procedures should be performed by an endoscopist with substantial experience.

“The workup of biliary strictures is challenging, invasive, and costly, requiring multiple diagnostic tools with highly variable yields,” co-author Victoria Gomez, MD, associate professor of medicine and director of bariatric endoscopy at Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., said in an interview.

“Providers caring for these patients must be up to date with the most current evidence so that they can make the safest and most well-informed decisions for their patients,” she said. “These include considerations such as limiting the use of anesthesia, using tests that will result in the highest diagnostic yield, and providing effective therapies to decompress biliary obstruction.”

Future questions

Additional research is needed in several areas to strengthen recommendations and advance the field, the study authors write.

“Biliary strictures without an associated mass are a diagnostic challenge, and there are exciting opportunities to understand how new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, can be used to improve our assessment,” co-author Anna Tavakkoli, MD, assistant professor of internal medicine in digestive and liver diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, said in an interview.

“Also, we highlighted several controversies in the drainage of perihilar strictures, including whether to use ERCP versus percutaneous drainage, whether metallic or plastic stents are better, and what the optimal stent placement should be,” she said. “Future multicenter studies are needed to address these key controversies.”

Although fully covered SEMS placement remains effective for benign biliary strictures, multiple plastic stents may be a better alternative in some cases. Such cases include those in which the stricture is close to the hilum, those in which the gallbladder is intact and in which crossing the cystic duct orifice cannot be avoided, those in which a fully covered SEMS has previously migrated or was not well tolerated, and those in which stricture has recurred after removal of a fully covered SEMS.

‘Comprehensive list’

“Overall, the authors have done a commendable job putting together a comprehensive list of recommendations that will invariably alter the practice of many therapeutic endoscopists for the diagnosis and management of biliary strictures,” Matthew Fasullo, DO, an advanced endoscopy and gastroenterology fellow at New York University Medical Center, told this news organization.

Dr. Fasullo, who wasn’t involved with the guideline, has published on advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment for post-transplant biliary complications.

“The fact that ... cholangioscopy-directed biopsies after an initial negative evaluation via ERCP reveal malignancy in 54% of cases underscores the need for best practice guidelines and supports advancements in diagnostics to confidently rule in or out cancer,” he said.

“The movement toward multimodality sampling at the time of initial evaluation with a combination of brushing, fluoroscopy-directed biopsies, cholangioscopy-directed biopsies, and fluorescence in situ hybridization should become universally adopted in those with an ambiguous diagnosis,” he added. “As technology continues to improve, next-generation sequencing will prove to be an invaluable adjunct to the current pathological evaluation.”

The authors received no financial support for the guideline. One author has a consultant role for Takeda Pharmaceuticals and is an advisory board member role for Advarra. The other authors and Dr. Fasullo have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The recommendations provide guidance on the care of patients with extrahepatic and perihilar strictures, with a focus on diagnosis and drainage. Although some of the principles may apply to intrahepatic strictures, the guideline doesn’t specifically address them. The new guideline is considered separate from the 2015 ACG guideline related to primary sclerosing cholangitis.

“The appropriate diagnosis and management of biliary strictures is still a big clinical challenge and has important implications in endoscopic, surgical, and oncological decision-making,” co-author Jennifer Maranki, MD, a professor of medicine and director of endoscopy at Penn State Hershey Medical Center, said in an interview.

“We wanted to provide the best possible guidance to gastroenterologists based on the available body of literature, with key shifts in diagnosis and management based on currently available modalities and tools,” she said.

The guideline was published in the March issue of the American Journal of Gastroenterology.

The recommendations were developed by a diverse group of authors from across the United States in recognition of the potential influence of commercial and intellectual conflicts of interest. The panel used a systematic process that involved structured literature searches by librarians and independent appraisal of the quality of evidence by dedicated methodologists, the authors write.

Overall, the team outlined 11 recommendations and 12 key concepts. A strong recommendation was made when the benefits of the test or intervention clearly outweighed the potential disadvantages. A conditional recommendation was made when some uncertainty remained about the balance of benefits and harms. Key concepts address important clinical questions that lack adequate evidence to inform recommendations. They are based on indirect evidence and expert opinion.

Epidemiology and diagnosis

The burden of biliary strictures is difficult to estimate, owing to the lack of a specific administrative code. The estimated cost of caring for biliary disease in the United States is about $16.9 billion annually, although this figure includes costs associated with gallbladder disease, choledocholithiasis, and other (nonobstructive) biliary disorders, the authors write.

Among the 57,000 new cases of pancreatic cancer each year, at least 60% will cause obstructive jaundice, resulting in about 34,000 annual cases of malignant extrahepatic biliary stricture, the team notes. In addition, about 3,000 cases of malignant perihilar stricture are expected in the United States each year. Patients may also seek care for benign strictures associated with chronic pancreatitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune disease, and post-cholecystectomy injury.

Under the first key concept, the authors note that biliary strictures in adults are more likely to be malignant than benign, except in certain well-defined scenarios. This underscores the importance of having a high index of clinical suspicion during evaluation, they add.