User login

Antioxidants may ease anxiety and depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depression has increased worldwide, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Therefore, identifying specific interventions that improve depressive status is critical for public health policy,” wrote Huan Wang, MD, of First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China, and colleagues.

Recent evidence suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors, including nutrition, may have a positive impact on symptoms of anxiety and depression, and observational studies have shown that antioxidant supplements affect depressive status, but data from randomized, controlled trials are limited by small sample sizes, they wrote.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 52 studies with a total of 4,049 patients. Of these, 2,004 received antioxidant supplements and 2,045 received a placebo supplement or no supplements. The median treatment duration was 11 weeks; treatment durations ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years. All 52 studies addressed the effect of antioxidants on depressive status, and 21 studies also assessed anxiety status. The studies used a range of depression scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Overall, the meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement in depressive status associated with antioxidant supplement use (standardized mean difference, 0.60; P < .00001). When broken down by supplement, significant positive effects appeared for magnesium (SMD = 0.16; P = .03), zinc (SMD = 0.59; P = .01), selenium (SMD = 0.33; P = .009), CoQ10 (SMD = 0.97; P = .05), tea and coffee (SMD = 1.15; P = .001) and crocin (MD = 6.04; P < .00001).

As a secondary outcome, antioxidant supplementation had a significantly positive effect on anxiety (SMD = 0.40; P < .00001).

The mechanism of action for the effect of antioxidants remains unclear, the researchers wrote in their discussion, but, “Depriving or boosting the supply of food components with antioxidant capabilities might worsen or lessen oxidative stress,” they said.

The researchers attempted a subgroup analysis across countries, and found that, while antioxidant supplementation improved depressive status in populations from Iran, China, and Italy, “no significant improvement was found in the United States, Australia, Italy and other countries.” The reasons for this difference might be related to fewer studies from these countries, or “the improvement brought about by antioxidants might be particularly pronounced in people with significant depression and higher depression scores,” they wrote. “Studies have shown that Asian countries have fewer psychiatrists and more expensive treatments,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to include all types of antioxidant supplements, the range of depression rating scales, and insufficient subgroup analysis of the range of populations from the included studies, the researchers noted.

“Additional data from large clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of antioxidant supplements in improving depressive status,” they said. However, the results suggest that antioxidants may play a role as an adjunct treatment to conventional antidepressants, they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression has increased worldwide, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Therefore, identifying specific interventions that improve depressive status is critical for public health policy,” wrote Huan Wang, MD, of First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China, and colleagues.

Recent evidence suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors, including nutrition, may have a positive impact on symptoms of anxiety and depression, and observational studies have shown that antioxidant supplements affect depressive status, but data from randomized, controlled trials are limited by small sample sizes, they wrote.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 52 studies with a total of 4,049 patients. Of these, 2,004 received antioxidant supplements and 2,045 received a placebo supplement or no supplements. The median treatment duration was 11 weeks; treatment durations ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years. All 52 studies addressed the effect of antioxidants on depressive status, and 21 studies also assessed anxiety status. The studies used a range of depression scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Overall, the meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement in depressive status associated with antioxidant supplement use (standardized mean difference, 0.60; P < .00001). When broken down by supplement, significant positive effects appeared for magnesium (SMD = 0.16; P = .03), zinc (SMD = 0.59; P = .01), selenium (SMD = 0.33; P = .009), CoQ10 (SMD = 0.97; P = .05), tea and coffee (SMD = 1.15; P = .001) and crocin (MD = 6.04; P < .00001).

As a secondary outcome, antioxidant supplementation had a significantly positive effect on anxiety (SMD = 0.40; P < .00001).

The mechanism of action for the effect of antioxidants remains unclear, the researchers wrote in their discussion, but, “Depriving or boosting the supply of food components with antioxidant capabilities might worsen or lessen oxidative stress,” they said.

The researchers attempted a subgroup analysis across countries, and found that, while antioxidant supplementation improved depressive status in populations from Iran, China, and Italy, “no significant improvement was found in the United States, Australia, Italy and other countries.” The reasons for this difference might be related to fewer studies from these countries, or “the improvement brought about by antioxidants might be particularly pronounced in people with significant depression and higher depression scores,” they wrote. “Studies have shown that Asian countries have fewer psychiatrists and more expensive treatments,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to include all types of antioxidant supplements, the range of depression rating scales, and insufficient subgroup analysis of the range of populations from the included studies, the researchers noted.

“Additional data from large clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of antioxidant supplements in improving depressive status,” they said. However, the results suggest that antioxidants may play a role as an adjunct treatment to conventional antidepressants, they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression has increased worldwide, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. “Therefore, identifying specific interventions that improve depressive status is critical for public health policy,” wrote Huan Wang, MD, of First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China, and colleagues.

Recent evidence suggests that modifiable lifestyle factors, including nutrition, may have a positive impact on symptoms of anxiety and depression, and observational studies have shown that antioxidant supplements affect depressive status, but data from randomized, controlled trials are limited by small sample sizes, they wrote.

In a study published in the Journal of Affective Disorders, the researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 52 studies with a total of 4,049 patients. Of these, 2,004 received antioxidant supplements and 2,045 received a placebo supplement or no supplements. The median treatment duration was 11 weeks; treatment durations ranged from 2 weeks to 2 years. All 52 studies addressed the effect of antioxidants on depressive status, and 21 studies also assessed anxiety status. The studies used a range of depression scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Overall, the meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement in depressive status associated with antioxidant supplement use (standardized mean difference, 0.60; P < .00001). When broken down by supplement, significant positive effects appeared for magnesium (SMD = 0.16; P = .03), zinc (SMD = 0.59; P = .01), selenium (SMD = 0.33; P = .009), CoQ10 (SMD = 0.97; P = .05), tea and coffee (SMD = 1.15; P = .001) and crocin (MD = 6.04; P < .00001).

As a secondary outcome, antioxidant supplementation had a significantly positive effect on anxiety (SMD = 0.40; P < .00001).

The mechanism of action for the effect of antioxidants remains unclear, the researchers wrote in their discussion, but, “Depriving or boosting the supply of food components with antioxidant capabilities might worsen or lessen oxidative stress,” they said.

The researchers attempted a subgroup analysis across countries, and found that, while antioxidant supplementation improved depressive status in populations from Iran, China, and Italy, “no significant improvement was found in the United States, Australia, Italy and other countries.” The reasons for this difference might be related to fewer studies from these countries, or “the improvement brought about by antioxidants might be particularly pronounced in people with significant depression and higher depression scores,” they wrote. “Studies have shown that Asian countries have fewer psychiatrists and more expensive treatments,” they added.

The findings were limited by several factors including the inability to include all types of antioxidant supplements, the range of depression rating scales, and insufficient subgroup analysis of the range of populations from the included studies, the researchers noted.

“Additional data from large clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of antioxidant supplements in improving depressive status,” they said. However, the results suggest that antioxidants may play a role as an adjunct treatment to conventional antidepressants, they concluded.

The study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF AFFECTIVE DISORDERS

Notes on direct admission of pediatric patients

Scenario: Yesterday you saw a 6-month-old infant with what appeared to be viral gastroenteritis and mild dehydration. When you called his parents today to check on his condition he was not improving despite your recommendations about his diet and oral rehydration. Should you have him brought to your office for a reevaluation, have his parents take him to the local emergency department for evaluation and probable hospital admission, or ask his parents to take him to the hospital telling them that you will call and arrange for a direct admission.

Obviously, I haven’t given you enough background information to allow you to give me an answer you are comfortable with. What time of day is it? Is it a holiday weekend? What’s the weather like? How far is it from the patient’s home to your office? To the emergency department? How is the local ED staffed? Are there hospitalists? What is their training?

Whether or not you choose to see the patient first in the office, is direct admission to the hospital an option that you are likely to choose? What steps do you take to see that it happens smoothly?

At least one-quarter of the unscheduled pediatric hospitalizations begin with a direct admission, meaning that the patients are not first evaluated in that hospital’s ED. In a recent policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care explored the pluses and minuses of direct admission and issued a list of seven recommendations. Among the concerns raised by the authors are “potential delays in initial evaluation and treatment, inconsistent admission processes, and difficulties in determining the appropriateness of patients for direct admission.” The committee makes it clear that they understand each community has it own strengths and challenges and the unique needs of each patient make it difficult to define a set of recommendations that fits all.

However, as I read through the committee’s seven recommendations, one leapt off the screen as a unifying concept that should apply in every situation. Recommendation No. 2 reads, “[There should be] clear systems of communication between members of the health care team and with families of children requiring admission.”

First, who is on this “health care team”? Are you a team member with the hospital folks – the ED nurses and doctors, the hospitalists, the floor nurses? Do you share an employer? Are you in the same town? Have your ever met them face to face? Do you do so regularly?

I assume you call the ED or the pediatric floor to arrange a direct admit? Maybe you don’t. I can recall working in situations where several infamous “local docs” would just send the patients in with a scribbled note (or not) and no phone call. Will you be speaking to folks who are even vaguely familiar with you or even your name? Do you get to speak with people who will be hands on with the patient?

Obviously, where I’m going with this is that, if you and the hospital staff are truly on the same health care team, communication should flow freely among the members and having some familiarity allows this to happen more smoothly. It can start on our end as the referring physician by making the call personally. Likewise, the receiving hospital must make frontline people available so you can speak with staff who will be working with the patient. Do you have enough information to tell the family what to expect?

Of course legible and complete records are a must. But nothing beats personal contact and a name. If you can tell a parent “I spoke to Martha, the nurse who will meet you on the floor,” that can be a giant first step forward in the healing process.

Most of us trained at hospitals that accepted direct admit patients and can remember the challenges. And most of us recall EDs that weren’t pediatric friendly. Whether our local situation favors direct admission or ED preadmission evaluation, it is our job to make the communication flow with the patient’s safety and the family’s comfort in mind.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Scenario: Yesterday you saw a 6-month-old infant with what appeared to be viral gastroenteritis and mild dehydration. When you called his parents today to check on his condition he was not improving despite your recommendations about his diet and oral rehydration. Should you have him brought to your office for a reevaluation, have his parents take him to the local emergency department for evaluation and probable hospital admission, or ask his parents to take him to the hospital telling them that you will call and arrange for a direct admission.

Obviously, I haven’t given you enough background information to allow you to give me an answer you are comfortable with. What time of day is it? Is it a holiday weekend? What’s the weather like? How far is it from the patient’s home to your office? To the emergency department? How is the local ED staffed? Are there hospitalists? What is their training?

Whether or not you choose to see the patient first in the office, is direct admission to the hospital an option that you are likely to choose? What steps do you take to see that it happens smoothly?

At least one-quarter of the unscheduled pediatric hospitalizations begin with a direct admission, meaning that the patients are not first evaluated in that hospital’s ED. In a recent policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care explored the pluses and minuses of direct admission and issued a list of seven recommendations. Among the concerns raised by the authors are “potential delays in initial evaluation and treatment, inconsistent admission processes, and difficulties in determining the appropriateness of patients for direct admission.” The committee makes it clear that they understand each community has it own strengths and challenges and the unique needs of each patient make it difficult to define a set of recommendations that fits all.

However, as I read through the committee’s seven recommendations, one leapt off the screen as a unifying concept that should apply in every situation. Recommendation No. 2 reads, “[There should be] clear systems of communication between members of the health care team and with families of children requiring admission.”

First, who is on this “health care team”? Are you a team member with the hospital folks – the ED nurses and doctors, the hospitalists, the floor nurses? Do you share an employer? Are you in the same town? Have your ever met them face to face? Do you do so regularly?

I assume you call the ED or the pediatric floor to arrange a direct admit? Maybe you don’t. I can recall working in situations where several infamous “local docs” would just send the patients in with a scribbled note (or not) and no phone call. Will you be speaking to folks who are even vaguely familiar with you or even your name? Do you get to speak with people who will be hands on with the patient?

Obviously, where I’m going with this is that, if you and the hospital staff are truly on the same health care team, communication should flow freely among the members and having some familiarity allows this to happen more smoothly. It can start on our end as the referring physician by making the call personally. Likewise, the receiving hospital must make frontline people available so you can speak with staff who will be working with the patient. Do you have enough information to tell the family what to expect?

Of course legible and complete records are a must. But nothing beats personal contact and a name. If you can tell a parent “I spoke to Martha, the nurse who will meet you on the floor,” that can be a giant first step forward in the healing process.

Most of us trained at hospitals that accepted direct admit patients and can remember the challenges. And most of us recall EDs that weren’t pediatric friendly. Whether our local situation favors direct admission or ED preadmission evaluation, it is our job to make the communication flow with the patient’s safety and the family’s comfort in mind.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

Scenario: Yesterday you saw a 6-month-old infant with what appeared to be viral gastroenteritis and mild dehydration. When you called his parents today to check on his condition he was not improving despite your recommendations about his diet and oral rehydration. Should you have him brought to your office for a reevaluation, have his parents take him to the local emergency department for evaluation and probable hospital admission, or ask his parents to take him to the hospital telling them that you will call and arrange for a direct admission.

Obviously, I haven’t given you enough background information to allow you to give me an answer you are comfortable with. What time of day is it? Is it a holiday weekend? What’s the weather like? How far is it from the patient’s home to your office? To the emergency department? How is the local ED staffed? Are there hospitalists? What is their training?

Whether or not you choose to see the patient first in the office, is direct admission to the hospital an option that you are likely to choose? What steps do you take to see that it happens smoothly?

At least one-quarter of the unscheduled pediatric hospitalizations begin with a direct admission, meaning that the patients are not first evaluated in that hospital’s ED. In a recent policy statement, the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Hospital Care explored the pluses and minuses of direct admission and issued a list of seven recommendations. Among the concerns raised by the authors are “potential delays in initial evaluation and treatment, inconsistent admission processes, and difficulties in determining the appropriateness of patients for direct admission.” The committee makes it clear that they understand each community has it own strengths and challenges and the unique needs of each patient make it difficult to define a set of recommendations that fits all.

However, as I read through the committee’s seven recommendations, one leapt off the screen as a unifying concept that should apply in every situation. Recommendation No. 2 reads, “[There should be] clear systems of communication between members of the health care team and with families of children requiring admission.”

First, who is on this “health care team”? Are you a team member with the hospital folks – the ED nurses and doctors, the hospitalists, the floor nurses? Do you share an employer? Are you in the same town? Have your ever met them face to face? Do you do so regularly?

I assume you call the ED or the pediatric floor to arrange a direct admit? Maybe you don’t. I can recall working in situations where several infamous “local docs” would just send the patients in with a scribbled note (or not) and no phone call. Will you be speaking to folks who are even vaguely familiar with you or even your name? Do you get to speak with people who will be hands on with the patient?

Obviously, where I’m going with this is that, if you and the hospital staff are truly on the same health care team, communication should flow freely among the members and having some familiarity allows this to happen more smoothly. It can start on our end as the referring physician by making the call personally. Likewise, the receiving hospital must make frontline people available so you can speak with staff who will be working with the patient. Do you have enough information to tell the family what to expect?

Of course legible and complete records are a must. But nothing beats personal contact and a name. If you can tell a parent “I spoke to Martha, the nurse who will meet you on the floor,” that can be a giant first step forward in the healing process.

Most of us trained at hospitals that accepted direct admit patients and can remember the challenges. And most of us recall EDs that weren’t pediatric friendly. Whether our local situation favors direct admission or ED preadmission evaluation, it is our job to make the communication flow with the patient’s safety and the family’s comfort in mind.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at [email protected].

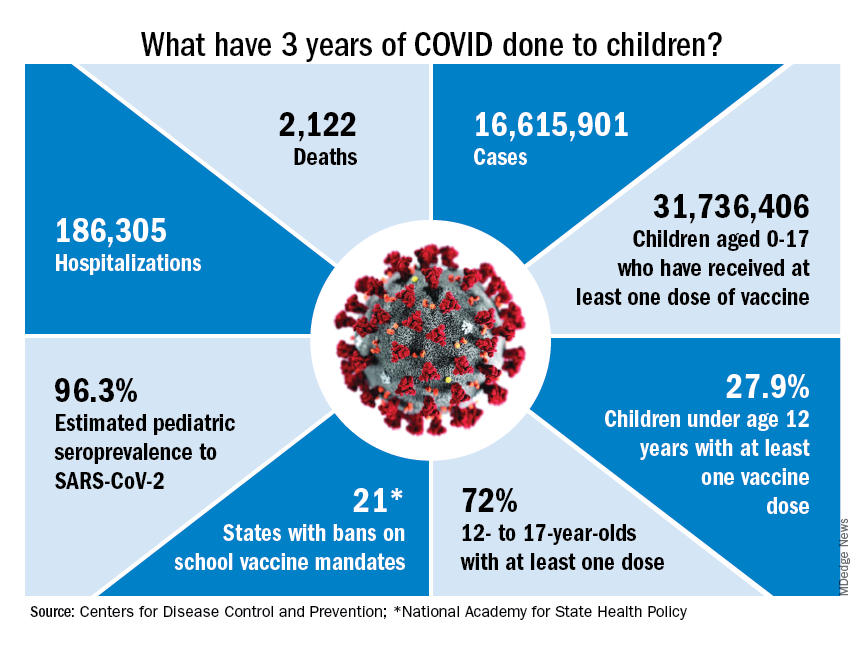

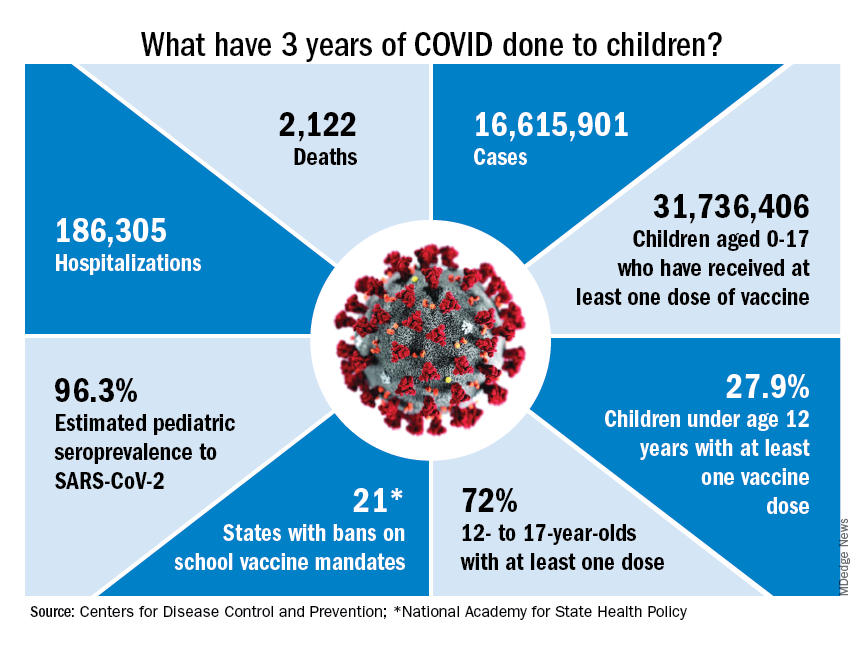

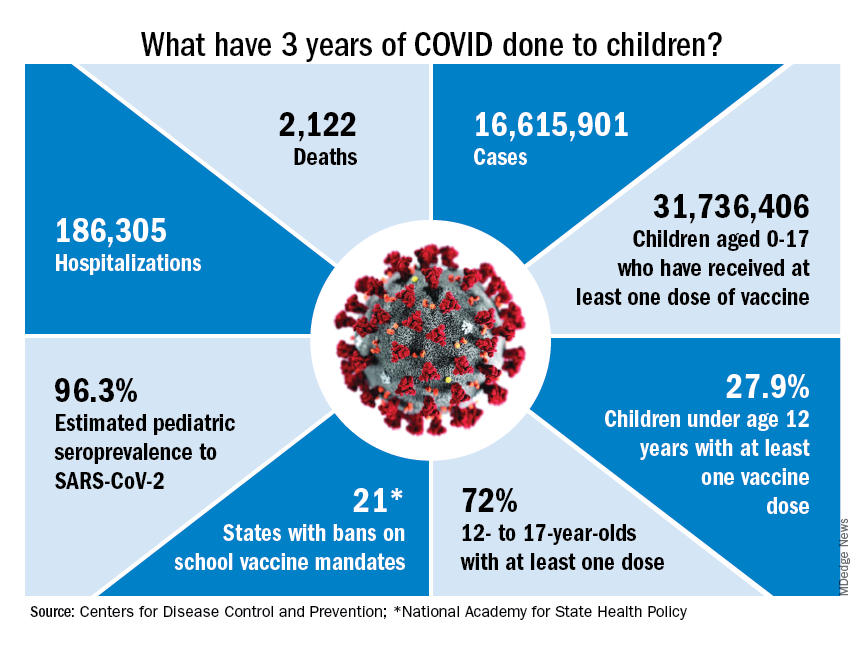

Pandemic hit Black children harder, study shows

Black children had almost three times as many COVID-related deaths as White children and about twice as many hospitalizations, according to a new study.

The study said that 1,556 children have died from the start of the pandemic until Nov. 30, 2022, with 593 of those children being 4 and under. Black children died of COVID-related causes 2.7 times more often than White children and were hospitalized 2.2 times more often than White children, the study said.

Lower vaccination rates for Black people may be a factor. The study said 43.6% of White children have received two or more vaccinations, compared with 40.2% of Black children.

“First and foremost, this study repudiates the misunderstanding that COVID-19 has not been of consequence to children who have had more than 15.5 million reported cases, representing 18 percent of all cases in the United States,” Reed Tuckson, MD, a member of the Black Coalition Against COVID board of directors and former District of Columbia public health commissioner, said in a news release.

“And second, our research shows that like their adult counterparts, Black and other children of color have shouldered more of the burden of COVID-19 than the White population.”

The study was commissioned by BCAC and conducted by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta. It’s based on studies conducted by other agencies over 2 years.

Black and Hispanic children also had more severe COVID cases, the study said. Among 281 pediatric patients in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 23.3% of severe cases were Black and 51% of severe cases were Hispanic.

The study says 1 in 310 Black children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID between April 2020 and June 2012, compared with 1 in 738 White children.

Economic and health-related hardships were experienced by 31% of Black households, 29% of Latino households, and 16% of White households, the study said.

“Children with COVID-19 in communities of color were sicker, [were] hospitalized and died at higher rates than White children,” Sandra Harris-Hooker, the interim executive director at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of Morehouse School, said in the release. “We can now fully understand the devastating impact the virus had on communities of color across generations.”

The study recommends several changes, such as modifying eligibility requirements for the Children’s Health Insurance Program to help more children who fall into coverage gaps and expanding the Child Tax Credit.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Black children had almost three times as many COVID-related deaths as White children and about twice as many hospitalizations, according to a new study.

The study said that 1,556 children have died from the start of the pandemic until Nov. 30, 2022, with 593 of those children being 4 and under. Black children died of COVID-related causes 2.7 times more often than White children and were hospitalized 2.2 times more often than White children, the study said.

Lower vaccination rates for Black people may be a factor. The study said 43.6% of White children have received two or more vaccinations, compared with 40.2% of Black children.

“First and foremost, this study repudiates the misunderstanding that COVID-19 has not been of consequence to children who have had more than 15.5 million reported cases, representing 18 percent of all cases in the United States,” Reed Tuckson, MD, a member of the Black Coalition Against COVID board of directors and former District of Columbia public health commissioner, said in a news release.

“And second, our research shows that like their adult counterparts, Black and other children of color have shouldered more of the burden of COVID-19 than the White population.”

The study was commissioned by BCAC and conducted by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta. It’s based on studies conducted by other agencies over 2 years.

Black and Hispanic children also had more severe COVID cases, the study said. Among 281 pediatric patients in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 23.3% of severe cases were Black and 51% of severe cases were Hispanic.

The study says 1 in 310 Black children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID between April 2020 and June 2012, compared with 1 in 738 White children.

Economic and health-related hardships were experienced by 31% of Black households, 29% of Latino households, and 16% of White households, the study said.

“Children with COVID-19 in communities of color were sicker, [were] hospitalized and died at higher rates than White children,” Sandra Harris-Hooker, the interim executive director at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of Morehouse School, said in the release. “We can now fully understand the devastating impact the virus had on communities of color across generations.”

The study recommends several changes, such as modifying eligibility requirements for the Children’s Health Insurance Program to help more children who fall into coverage gaps and expanding the Child Tax Credit.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Black children had almost three times as many COVID-related deaths as White children and about twice as many hospitalizations, according to a new study.

The study said that 1,556 children have died from the start of the pandemic until Nov. 30, 2022, with 593 of those children being 4 and under. Black children died of COVID-related causes 2.7 times more often than White children and were hospitalized 2.2 times more often than White children, the study said.

Lower vaccination rates for Black people may be a factor. The study said 43.6% of White children have received two or more vaccinations, compared with 40.2% of Black children.

“First and foremost, this study repudiates the misunderstanding that COVID-19 has not been of consequence to children who have had more than 15.5 million reported cases, representing 18 percent of all cases in the United States,” Reed Tuckson, MD, a member of the Black Coalition Against COVID board of directors and former District of Columbia public health commissioner, said in a news release.

“And second, our research shows that like their adult counterparts, Black and other children of color have shouldered more of the burden of COVID-19 than the White population.”

The study was commissioned by BCAC and conducted by the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of the Morehouse School of Medicine, Atlanta. It’s based on studies conducted by other agencies over 2 years.

Black and Hispanic children also had more severe COVID cases, the study said. Among 281 pediatric patients in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, 23.3% of severe cases were Black and 51% of severe cases were Hispanic.

The study says 1 in 310 Black children lost a parent or caregiver to COVID between April 2020 and June 2012, compared with 1 in 738 White children.

Economic and health-related hardships were experienced by 31% of Black households, 29% of Latino households, and 16% of White households, the study said.

“Children with COVID-19 in communities of color were sicker, [were] hospitalized and died at higher rates than White children,” Sandra Harris-Hooker, the interim executive director at the Satcher Health Leadership Institute of Morehouse School, said in the release. “We can now fully understand the devastating impact the virus had on communities of color across generations.”

The study recommends several changes, such as modifying eligibility requirements for the Children’s Health Insurance Program to help more children who fall into coverage gaps and expanding the Child Tax Credit.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Navigating your childcare options in a post-COVID world

When we found out we were expecting our first child, we were ecstatic. Our excitement soon gave way to panic, however, as we realized that we needed a plan for childcare. As full-time physicians early in our careers, neither of us was prepared to drop to part-time or become a stay-at-home caregiver. Not knowing where to start, we turned to our friends and colleagues, and of course, the Internet, for advice on our options.

In our research, we discovered three things. First, with COVID-19, the cost of childcare has skyrocketed, and availability has decreased. Second, there are several options for childcare, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Third, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Family

Using family members to provide childcare is often cost-effective and provides a familiar, supportive environment for children. Proximity does not guarantee a willingness or ability to provide long-term care, however, and it can cause strain on family relationships, lead to intrusions and boundary issues, and create feelings of obligation and guilt. It is important to have very honest, up-front discussions with family members about hopes and expectations if this is your childcare plan.

Daycare, facility-based

Daycare centers are commercial facilities that offer care to multiple children of varying ages, starting from as young as 6 weeks. They have trained professionals and provide structured activities and educational programs for children. Many daycares also provide snacks and lunch, which is included in their tuition. They are a popular choice for families seeking full-time childcare and the social and educational benefits that come with a structured setting.

Daycares also have some downsides. They usually operate during normal workday hours, from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., which may not be convenient for physicians who work outside of these hours. Even with feasible hours, getting children dressed, ready, and dropped off each morning could add significant time and stress to your morning routine. Additionally, most daycares have policies that prohibit attendance if a child is sick or febrile, which is a common occurrence, particularly for daycare kids. In case of an illness outbreak, the daycare may even close for several days. Both scenarios require at least one parent to take a day off or have an alternative childcare plan available on short notice.

Availability of daycare can be limited, particularly since the COVID pandemic, creating waitlists that can be several months long. Early registration, even during pregnancy, is recommended to secure a spot. It can be helpful to find out if your employer has an agreement with a specific daycare that has “physician-friendly” hours and gives waitlist priority to trainees or even attending physicians. The cost of daycare for one child is typically affordable, around $12,000 per year on average, but can be as high as $25,000 in cities with high cost of living. A sibling discount may be offered, but the cost of daycare for multiple children could still exceed in-home childcare options.1

Daycare, home-based (also known as family care centers)

Family care centers offer a home-like alternative to daycares, with smaller staff-to-child ratios and often more personalized care. They are favored by families seeking a more intimate setting. They might offer more flexible scheduling and are typically less expensive than facility-based daycares, at up to 25% lower cost.1 They may lack the same structure and educational opportunities as facility-based daycares, however, and are not subject to the same health and safety regulations.

Nannies

Nannies are professional caregivers who provide in-home childcare services. Their responsibilities may include feeding, changing, dressing, bathing, and playing with children. In some cases, they may also be expected to do light housekeeping tasks like meal preparation, laundry, and cleaning. It is common for nannies in high-demand markets to refuse to perform these additional tasks, however. Nannies are preferred by families with hectic schedules due to their flexibility. They can work early, late, or even overnight shifts, and provide care in the comfort of your home, avoiding the hassle of drop-off and pick-up times. Nannies also can provide personalized care to meet each child’s specific needs, and they can care for children who are sick or febrile.

When hiring a nanny, it is important to have a written contract outlining their expected hours, wages, benefits, and duties to prevent misunderstandings in the future. Finding a trustworthy and reliable nanny can be a challenge, and families have several options for finding one. They can post jobs on free websites and browse nanny CVs or use a fee-based nanny agency. The cost of using an agency can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, so it is important to ask friends and colleagues for recommendations before paying for an agency’s services.

The cost of hiring a nanny is one of its main drawbacks. Nannies typically earn $15 to $30 per hour, and if they work in the family’s home, they are typically considered “household employees” by the IRS. Household employees are entitled to overtime pay for work beyond 40 hours per week, and the employer (you!) is responsible for payroll taxes, withholding, and providing an annual W-2 tax statement.2 There are affordable online nanny payroll services that handle payroll and tax-filing to simplify the process, however. The average annual cost of a full-time nanny is around $40,000 and can be as high as $75,000 in some markets.1 A nanny-share with other families can lower costs, but it may also result in less control over the caregiver and schedule.

It is important to consult a tax professional or the IRS for guidance on nanny wages, taxes, and payroll, as a nanny might rarely be considered an “independent contractor” if they meet certain criteria.

Au pair

An au pair is a live-in childcare provider who travels to a host family’s home from a foreign country on a special J-1 visa. The goal is to provide care for children and participate in cultural exchange activities. Au pairs bring many benefits, such as cost savings compared to traditional childcare options and greater flexibility and customization. They can work up to 10 hours per day and 45 hours a week, performing tasks such as light housekeeping, meal preparation, and transportation for the children. Host families must provide a safe and comfortable living environment, including a private room, meals, and some travel and education expenses.1

The process of hiring an au pair involves working with a designated agency that matches families with applicants and sponsors the J-1 visa. The entire process can take several months, and average program fees cost around $10,000 per placement. Au pairs are hired on a 12-month J-1 visa, which can be extended for up to an additional 12 months, allowing families up to 2 years with the same au pair before needing to find a new placement.

Au pairs earn a minimum weekly stipend of $195.75, set forth by the U.S. State Department.3 Currently, au pairs are not subject to local and state wage requirements, but legal proceedings in various states have recently questioned whether au pairs should be protected under local regulations. Massachusetts has been the most progressive, explicitly protecting au pairs as domestic workers under state labor laws, raising their weekly stipend to roughly $600 to comply with state minimum wage requirements.4 The federal government is expected to provide clarity on this issue, but for the time being, au pairs remain an affordable alternative to a nanny in most states.

Conclusion

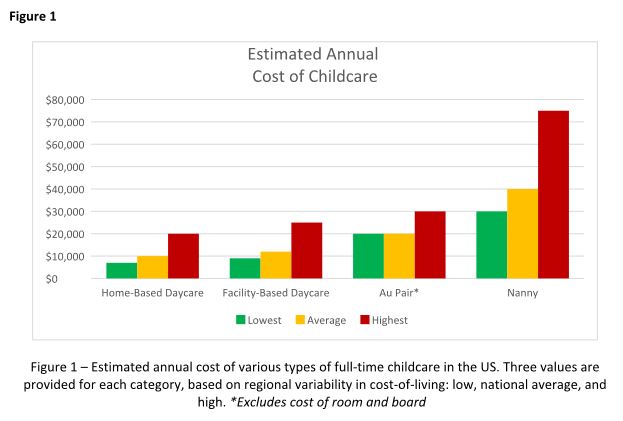

Choosing childcare is a complicated process with multiple factors to consider. Figure 1 breaks down the estimated annual cost of each of the options outlined above for a single child in low, average, and high cost-of-living areas. But your decision likely hinges on much more than just cost, and may include family dynamics, scheduling needs, and personal preferences. Gather as much advice and information as possible, but remember to trust your instincts and make the decision that works best for your family. At the end of the day, what matters most is the happiness and well-being of your child.

Dr. Hathorn and Dr. Creighton are married, and both work full-time with a 1-year-old child. Dr. Hathorn is a bariatric and advanced therapeutic endoscopist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Creighton is an anesthesiologist at UNC Chapel Hill. Neither reported any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Care.com. This is how much childcare costs in 2022. 2022 Jun 15.

2. Internal Revenue Service. Publication 926 - Household Employer’s Tax Guide 2023.

3. U.S. Department of State. Au Pair.

4. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Domestic workers.

Disclaimer

The financial and tax information presented in this article are believed to be true and accurate at the time of writing. However, it’s important to note that tax laws and regulations are subject to change. The authors are not certified financial advisers or tax specialists. It is recommended to seek verification from a local tax expert or the Internal Revenue Service to discuss your specific situation.

When we found out we were expecting our first child, we were ecstatic. Our excitement soon gave way to panic, however, as we realized that we needed a plan for childcare. As full-time physicians early in our careers, neither of us was prepared to drop to part-time or become a stay-at-home caregiver. Not knowing where to start, we turned to our friends and colleagues, and of course, the Internet, for advice on our options.

In our research, we discovered three things. First, with COVID-19, the cost of childcare has skyrocketed, and availability has decreased. Second, there are several options for childcare, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Third, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Family

Using family members to provide childcare is often cost-effective and provides a familiar, supportive environment for children. Proximity does not guarantee a willingness or ability to provide long-term care, however, and it can cause strain on family relationships, lead to intrusions and boundary issues, and create feelings of obligation and guilt. It is important to have very honest, up-front discussions with family members about hopes and expectations if this is your childcare plan.

Daycare, facility-based

Daycare centers are commercial facilities that offer care to multiple children of varying ages, starting from as young as 6 weeks. They have trained professionals and provide structured activities and educational programs for children. Many daycares also provide snacks and lunch, which is included in their tuition. They are a popular choice for families seeking full-time childcare and the social and educational benefits that come with a structured setting.

Daycares also have some downsides. They usually operate during normal workday hours, from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., which may not be convenient for physicians who work outside of these hours. Even with feasible hours, getting children dressed, ready, and dropped off each morning could add significant time and stress to your morning routine. Additionally, most daycares have policies that prohibit attendance if a child is sick or febrile, which is a common occurrence, particularly for daycare kids. In case of an illness outbreak, the daycare may even close for several days. Both scenarios require at least one parent to take a day off or have an alternative childcare plan available on short notice.

Availability of daycare can be limited, particularly since the COVID pandemic, creating waitlists that can be several months long. Early registration, even during pregnancy, is recommended to secure a spot. It can be helpful to find out if your employer has an agreement with a specific daycare that has “physician-friendly” hours and gives waitlist priority to trainees or even attending physicians. The cost of daycare for one child is typically affordable, around $12,000 per year on average, but can be as high as $25,000 in cities with high cost of living. A sibling discount may be offered, but the cost of daycare for multiple children could still exceed in-home childcare options.1

Daycare, home-based (also known as family care centers)

Family care centers offer a home-like alternative to daycares, with smaller staff-to-child ratios and often more personalized care. They are favored by families seeking a more intimate setting. They might offer more flexible scheduling and are typically less expensive than facility-based daycares, at up to 25% lower cost.1 They may lack the same structure and educational opportunities as facility-based daycares, however, and are not subject to the same health and safety regulations.

Nannies

Nannies are professional caregivers who provide in-home childcare services. Their responsibilities may include feeding, changing, dressing, bathing, and playing with children. In some cases, they may also be expected to do light housekeeping tasks like meal preparation, laundry, and cleaning. It is common for nannies in high-demand markets to refuse to perform these additional tasks, however. Nannies are preferred by families with hectic schedules due to their flexibility. They can work early, late, or even overnight shifts, and provide care in the comfort of your home, avoiding the hassle of drop-off and pick-up times. Nannies also can provide personalized care to meet each child’s specific needs, and they can care for children who are sick or febrile.

When hiring a nanny, it is important to have a written contract outlining their expected hours, wages, benefits, and duties to prevent misunderstandings in the future. Finding a trustworthy and reliable nanny can be a challenge, and families have several options for finding one. They can post jobs on free websites and browse nanny CVs or use a fee-based nanny agency. The cost of using an agency can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, so it is important to ask friends and colleagues for recommendations before paying for an agency’s services.

The cost of hiring a nanny is one of its main drawbacks. Nannies typically earn $15 to $30 per hour, and if they work in the family’s home, they are typically considered “household employees” by the IRS. Household employees are entitled to overtime pay for work beyond 40 hours per week, and the employer (you!) is responsible for payroll taxes, withholding, and providing an annual W-2 tax statement.2 There are affordable online nanny payroll services that handle payroll and tax-filing to simplify the process, however. The average annual cost of a full-time nanny is around $40,000 and can be as high as $75,000 in some markets.1 A nanny-share with other families can lower costs, but it may also result in less control over the caregiver and schedule.

It is important to consult a tax professional or the IRS for guidance on nanny wages, taxes, and payroll, as a nanny might rarely be considered an “independent contractor” if they meet certain criteria.

Au pair

An au pair is a live-in childcare provider who travels to a host family’s home from a foreign country on a special J-1 visa. The goal is to provide care for children and participate in cultural exchange activities. Au pairs bring many benefits, such as cost savings compared to traditional childcare options and greater flexibility and customization. They can work up to 10 hours per day and 45 hours a week, performing tasks such as light housekeeping, meal preparation, and transportation for the children. Host families must provide a safe and comfortable living environment, including a private room, meals, and some travel and education expenses.1

The process of hiring an au pair involves working with a designated agency that matches families with applicants and sponsors the J-1 visa. The entire process can take several months, and average program fees cost around $10,000 per placement. Au pairs are hired on a 12-month J-1 visa, which can be extended for up to an additional 12 months, allowing families up to 2 years with the same au pair before needing to find a new placement.

Au pairs earn a minimum weekly stipend of $195.75, set forth by the U.S. State Department.3 Currently, au pairs are not subject to local and state wage requirements, but legal proceedings in various states have recently questioned whether au pairs should be protected under local regulations. Massachusetts has been the most progressive, explicitly protecting au pairs as domestic workers under state labor laws, raising their weekly stipend to roughly $600 to comply with state minimum wage requirements.4 The federal government is expected to provide clarity on this issue, but for the time being, au pairs remain an affordable alternative to a nanny in most states.

Conclusion

Choosing childcare is a complicated process with multiple factors to consider. Figure 1 breaks down the estimated annual cost of each of the options outlined above for a single child in low, average, and high cost-of-living areas. But your decision likely hinges on much more than just cost, and may include family dynamics, scheduling needs, and personal preferences. Gather as much advice and information as possible, but remember to trust your instincts and make the decision that works best for your family. At the end of the day, what matters most is the happiness and well-being of your child.

Dr. Hathorn and Dr. Creighton are married, and both work full-time with a 1-year-old child. Dr. Hathorn is a bariatric and advanced therapeutic endoscopist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Creighton is an anesthesiologist at UNC Chapel Hill. Neither reported any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Care.com. This is how much childcare costs in 2022. 2022 Jun 15.

2. Internal Revenue Service. Publication 926 - Household Employer’s Tax Guide 2023.

3. U.S. Department of State. Au Pair.

4. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Domestic workers.

Disclaimer

The financial and tax information presented in this article are believed to be true and accurate at the time of writing. However, it’s important to note that tax laws and regulations are subject to change. The authors are not certified financial advisers or tax specialists. It is recommended to seek verification from a local tax expert or the Internal Revenue Service to discuss your specific situation.

When we found out we were expecting our first child, we were ecstatic. Our excitement soon gave way to panic, however, as we realized that we needed a plan for childcare. As full-time physicians early in our careers, neither of us was prepared to drop to part-time or become a stay-at-home caregiver. Not knowing where to start, we turned to our friends and colleagues, and of course, the Internet, for advice on our options.

In our research, we discovered three things. First, with COVID-19, the cost of childcare has skyrocketed, and availability has decreased. Second, there are several options for childcare, each with its own benefits and drawbacks. Third, there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Family

Using family members to provide childcare is often cost-effective and provides a familiar, supportive environment for children. Proximity does not guarantee a willingness or ability to provide long-term care, however, and it can cause strain on family relationships, lead to intrusions and boundary issues, and create feelings of obligation and guilt. It is important to have very honest, up-front discussions with family members about hopes and expectations if this is your childcare plan.

Daycare, facility-based

Daycare centers are commercial facilities that offer care to multiple children of varying ages, starting from as young as 6 weeks. They have trained professionals and provide structured activities and educational programs for children. Many daycares also provide snacks and lunch, which is included in their tuition. They are a popular choice for families seeking full-time childcare and the social and educational benefits that come with a structured setting.

Daycares also have some downsides. They usually operate during normal workday hours, from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m., which may not be convenient for physicians who work outside of these hours. Even with feasible hours, getting children dressed, ready, and dropped off each morning could add significant time and stress to your morning routine. Additionally, most daycares have policies that prohibit attendance if a child is sick or febrile, which is a common occurrence, particularly for daycare kids. In case of an illness outbreak, the daycare may even close for several days. Both scenarios require at least one parent to take a day off or have an alternative childcare plan available on short notice.

Availability of daycare can be limited, particularly since the COVID pandemic, creating waitlists that can be several months long. Early registration, even during pregnancy, is recommended to secure a spot. It can be helpful to find out if your employer has an agreement with a specific daycare that has “physician-friendly” hours and gives waitlist priority to trainees or even attending physicians. The cost of daycare for one child is typically affordable, around $12,000 per year on average, but can be as high as $25,000 in cities with high cost of living. A sibling discount may be offered, but the cost of daycare for multiple children could still exceed in-home childcare options.1

Daycare, home-based (also known as family care centers)

Family care centers offer a home-like alternative to daycares, with smaller staff-to-child ratios and often more personalized care. They are favored by families seeking a more intimate setting. They might offer more flexible scheduling and are typically less expensive than facility-based daycares, at up to 25% lower cost.1 They may lack the same structure and educational opportunities as facility-based daycares, however, and are not subject to the same health and safety regulations.

Nannies

Nannies are professional caregivers who provide in-home childcare services. Their responsibilities may include feeding, changing, dressing, bathing, and playing with children. In some cases, they may also be expected to do light housekeeping tasks like meal preparation, laundry, and cleaning. It is common for nannies in high-demand markets to refuse to perform these additional tasks, however. Nannies are preferred by families with hectic schedules due to their flexibility. They can work early, late, or even overnight shifts, and provide care in the comfort of your home, avoiding the hassle of drop-off and pick-up times. Nannies also can provide personalized care to meet each child’s specific needs, and they can care for children who are sick or febrile.

When hiring a nanny, it is important to have a written contract outlining their expected hours, wages, benefits, and duties to prevent misunderstandings in the future. Finding a trustworthy and reliable nanny can be a challenge, and families have several options for finding one. They can post jobs on free websites and browse nanny CVs or use a fee-based nanny agency. The cost of using an agency can range from a few hundred to several thousand dollars, so it is important to ask friends and colleagues for recommendations before paying for an agency’s services.

The cost of hiring a nanny is one of its main drawbacks. Nannies typically earn $15 to $30 per hour, and if they work in the family’s home, they are typically considered “household employees” by the IRS. Household employees are entitled to overtime pay for work beyond 40 hours per week, and the employer (you!) is responsible for payroll taxes, withholding, and providing an annual W-2 tax statement.2 There are affordable online nanny payroll services that handle payroll and tax-filing to simplify the process, however. The average annual cost of a full-time nanny is around $40,000 and can be as high as $75,000 in some markets.1 A nanny-share with other families can lower costs, but it may also result in less control over the caregiver and schedule.

It is important to consult a tax professional or the IRS for guidance on nanny wages, taxes, and payroll, as a nanny might rarely be considered an “independent contractor” if they meet certain criteria.

Au pair

An au pair is a live-in childcare provider who travels to a host family’s home from a foreign country on a special J-1 visa. The goal is to provide care for children and participate in cultural exchange activities. Au pairs bring many benefits, such as cost savings compared to traditional childcare options and greater flexibility and customization. They can work up to 10 hours per day and 45 hours a week, performing tasks such as light housekeeping, meal preparation, and transportation for the children. Host families must provide a safe and comfortable living environment, including a private room, meals, and some travel and education expenses.1

The process of hiring an au pair involves working with a designated agency that matches families with applicants and sponsors the J-1 visa. The entire process can take several months, and average program fees cost around $10,000 per placement. Au pairs are hired on a 12-month J-1 visa, which can be extended for up to an additional 12 months, allowing families up to 2 years with the same au pair before needing to find a new placement.

Au pairs earn a minimum weekly stipend of $195.75, set forth by the U.S. State Department.3 Currently, au pairs are not subject to local and state wage requirements, but legal proceedings in various states have recently questioned whether au pairs should be protected under local regulations. Massachusetts has been the most progressive, explicitly protecting au pairs as domestic workers under state labor laws, raising their weekly stipend to roughly $600 to comply with state minimum wage requirements.4 The federal government is expected to provide clarity on this issue, but for the time being, au pairs remain an affordable alternative to a nanny in most states.

Conclusion

Choosing childcare is a complicated process with multiple factors to consider. Figure 1 breaks down the estimated annual cost of each of the options outlined above for a single child in low, average, and high cost-of-living areas. But your decision likely hinges on much more than just cost, and may include family dynamics, scheduling needs, and personal preferences. Gather as much advice and information as possible, but remember to trust your instincts and make the decision that works best for your family. At the end of the day, what matters most is the happiness and well-being of your child.

Dr. Hathorn and Dr. Creighton are married, and both work full-time with a 1-year-old child. Dr. Hathorn is a bariatric and advanced therapeutic endoscopist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Creighton is an anesthesiologist at UNC Chapel Hill. Neither reported any conflicts of interest.

References

1. Care.com. This is how much childcare costs in 2022. 2022 Jun 15.

2. Internal Revenue Service. Publication 926 - Household Employer’s Tax Guide 2023.

3. U.S. Department of State. Au Pair.

4. Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Domestic workers.

Disclaimer

The financial and tax information presented in this article are believed to be true and accurate at the time of writing. However, it’s important to note that tax laws and regulations are subject to change. The authors are not certified financial advisers or tax specialists. It is recommended to seek verification from a local tax expert or the Internal Revenue Service to discuss your specific situation.

From private practice to academic medicine: My journey and lessons learned

Loyalty.

This is a quality that I value in relationships. Loyalty was a significant factor contributing to my postfellowship commitment to private practice. In 2001, I graduated from physician assistant school and accepted a job with a private practice GI group in Omaha. I was fortunate to work with supportive gastroenterologists who encouraged me to pursue further training after I expressed an interest in medical school. My goal was to become a gastroenterologist but like every medical student, I would keep an open mind. My decision did not waver, and the support from my first mentors continued. As I graduated from fellowship in 2014, I gravitated toward the same private practice largely based on loyalty and my experience as a PA.

COURTESY AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

My experience in private practice was positive. My focus at that time and currently is clinical medicine with a focus on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. My colleagues were supportive, and I worked with a great team of nurses and APPs. I cared for many patients in both the inpatient and outpatient setting and had an opportunity to complete a high volume and variety of procedures. Overall, the various aspects of my job were rewarding. However, something was missing, and I made personal and professional adjustments. My schedule pulled me from valued family time with my kids (mostly) in the early mornings, therefore, I altered my work schedule. My clinical interest in IBD was diluted by the emphasis to see mostly general GI patients, as is the case for many in private practice. I missed the academic environment, especially working with medical students, residents, and fellows, so I occasionally had residents shadow me. Unfortunately, adjustments did not “fix” that missing component – to me, this was a job that did not feel like a career. I was not professionally fulfilled and on several occasions during the 6 years in private practice, I connected with mentors from my medical training to explore career options while trying to define what was missing.

During the latter part of years 5 and 6, it became apparent to me that loyalty pulled me toward working with a great group of supportive gastroenterologists, but it became increasingly more apparent that this job was not in line with my career goals. I had identified that I wanted to actively participate in medical education while practicing as a gastroenterologist in an academic setting. Additionally, time with my family was a critical part to the work-life integration.

My approach to the next step in my journey was different than my initial job. My goal was to define what was important, as in what were my absolute requirements for career satisfaction and where was I willing to be flexible. Each of us has different absolute and relative requirements based on our values, and I neglected to clearly identify these components with my first job. Admittedly, I have (at times) struggled to acknowledge my values, because I might somehow appear less committed to a career. Owning these values has provided clarity in my path from private practice to academic medicine. During the 3 years I have been in my current position, I have stepped into a leadership role in the University of Nebraska Medicine GI fellowship program while providing clinical medicine at the Fred Paustian IBD Center at Nebraska Medicine. In addition, I continue to have an active endoscopy schedule and derive great satisfaction teaching the fellows how to be effective endoscopists. Personally, the difference in compensation between academic medicine and private practice was not an important factor, although this is a factor for some people (and that’s okay).

When I graduated from fellowship, my path seemed clear, and I did not anticipate the road ahead. However, with each hurdle, I was gifted with lessons that would prove to be valuable as I moved ahead. Thank you for giving me the space to share my story.

Lessons that have helped in my journey from private practice to academics

- Mentorship: Find mentors, not just one mentor. Over the years, I have had several mentors, but what I recognize is that, early in my career, I did not have a mentor. Although a mentor cannot make decisions for you, he/she can provide guidance from a place of experience (both career and life experience).

- Define a mission statement: My mentor pushed me to first define my values and then my mission statement. This serves as the foundation that I reference when making decisions that will impact my family and my career. For example, if I am invited to participate on a committee, I look at how this will impact my family and whether it aligns with my mission. This helps to clarify what I am willing to say yes to and what to pass along to another colleague. Remember that last part ... if you are saying no to something, suggest another colleague for the opportunity.

- Advocate for yourself: Only you know what is best for you. Sometimes the path to discovering what that is can be tortuous and require guidance. Throughout my journey, I worked with colleagues who were supportive of my journey back to medical school and supportive of my job in private practice, but only I could define what a career meant to me.

- Assume positive intent: In medicine, we frequently work in a high-stakes, stressful environment. Assume positive intent in your interactions with others, especially colleagues. This will serve you well.

- Life happens: Each of us will experience an unexpected event in our personal life or career path or both. This will be okay. The path forward may look different and require a pivot. This unexpected event might be that you find your job leaves you wanting something more or something different. Your journey will be right for you.

Dr. Hutchins is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. She reported no conflicts of interest.

Loyalty.

This is a quality that I value in relationships. Loyalty was a significant factor contributing to my postfellowship commitment to private practice. In 2001, I graduated from physician assistant school and accepted a job with a private practice GI group in Omaha. I was fortunate to work with supportive gastroenterologists who encouraged me to pursue further training after I expressed an interest in medical school. My goal was to become a gastroenterologist but like every medical student, I would keep an open mind. My decision did not waver, and the support from my first mentors continued. As I graduated from fellowship in 2014, I gravitated toward the same private practice largely based on loyalty and my experience as a PA.

COURTESY AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

My experience in private practice was positive. My focus at that time and currently is clinical medicine with a focus on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. My colleagues were supportive, and I worked with a great team of nurses and APPs. I cared for many patients in both the inpatient and outpatient setting and had an opportunity to complete a high volume and variety of procedures. Overall, the various aspects of my job were rewarding. However, something was missing, and I made personal and professional adjustments. My schedule pulled me from valued family time with my kids (mostly) in the early mornings, therefore, I altered my work schedule. My clinical interest in IBD was diluted by the emphasis to see mostly general GI patients, as is the case for many in private practice. I missed the academic environment, especially working with medical students, residents, and fellows, so I occasionally had residents shadow me. Unfortunately, adjustments did not “fix” that missing component – to me, this was a job that did not feel like a career. I was not professionally fulfilled and on several occasions during the 6 years in private practice, I connected with mentors from my medical training to explore career options while trying to define what was missing.

During the latter part of years 5 and 6, it became apparent to me that loyalty pulled me toward working with a great group of supportive gastroenterologists, but it became increasingly more apparent that this job was not in line with my career goals. I had identified that I wanted to actively participate in medical education while practicing as a gastroenterologist in an academic setting. Additionally, time with my family was a critical part to the work-life integration.

My approach to the next step in my journey was different than my initial job. My goal was to define what was important, as in what were my absolute requirements for career satisfaction and where was I willing to be flexible. Each of us has different absolute and relative requirements based on our values, and I neglected to clearly identify these components with my first job. Admittedly, I have (at times) struggled to acknowledge my values, because I might somehow appear less committed to a career. Owning these values has provided clarity in my path from private practice to academic medicine. During the 3 years I have been in my current position, I have stepped into a leadership role in the University of Nebraska Medicine GI fellowship program while providing clinical medicine at the Fred Paustian IBD Center at Nebraska Medicine. In addition, I continue to have an active endoscopy schedule and derive great satisfaction teaching the fellows how to be effective endoscopists. Personally, the difference in compensation between academic medicine and private practice was not an important factor, although this is a factor for some people (and that’s okay).

When I graduated from fellowship, my path seemed clear, and I did not anticipate the road ahead. However, with each hurdle, I was gifted with lessons that would prove to be valuable as I moved ahead. Thank you for giving me the space to share my story.

Lessons that have helped in my journey from private practice to academics

- Mentorship: Find mentors, not just one mentor. Over the years, I have had several mentors, but what I recognize is that, early in my career, I did not have a mentor. Although a mentor cannot make decisions for you, he/she can provide guidance from a place of experience (both career and life experience).

- Define a mission statement: My mentor pushed me to first define my values and then my mission statement. This serves as the foundation that I reference when making decisions that will impact my family and my career. For example, if I am invited to participate on a committee, I look at how this will impact my family and whether it aligns with my mission. This helps to clarify what I am willing to say yes to and what to pass along to another colleague. Remember that last part ... if you are saying no to something, suggest another colleague for the opportunity.

- Advocate for yourself: Only you know what is best for you. Sometimes the path to discovering what that is can be tortuous and require guidance. Throughout my journey, I worked with colleagues who were supportive of my journey back to medical school and supportive of my job in private practice, but only I could define what a career meant to me.

- Assume positive intent: In medicine, we frequently work in a high-stakes, stressful environment. Assume positive intent in your interactions with others, especially colleagues. This will serve you well.

- Life happens: Each of us will experience an unexpected event in our personal life or career path or both. This will be okay. The path forward may look different and require a pivot. This unexpected event might be that you find your job leaves you wanting something more or something different. Your journey will be right for you.

Dr. Hutchins is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. She reported no conflicts of interest.

Loyalty.

This is a quality that I value in relationships. Loyalty was a significant factor contributing to my postfellowship commitment to private practice. In 2001, I graduated from physician assistant school and accepted a job with a private practice GI group in Omaha. I was fortunate to work with supportive gastroenterologists who encouraged me to pursue further training after I expressed an interest in medical school. My goal was to become a gastroenterologist but like every medical student, I would keep an open mind. My decision did not waver, and the support from my first mentors continued. As I graduated from fellowship in 2014, I gravitated toward the same private practice largely based on loyalty and my experience as a PA.

COURTESY AMERICAN GASTROENTEROLOGICAL ASSOCIATION

My experience in private practice was positive. My focus at that time and currently is clinical medicine with a focus on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. My colleagues were supportive, and I worked with a great team of nurses and APPs. I cared for many patients in both the inpatient and outpatient setting and had an opportunity to complete a high volume and variety of procedures. Overall, the various aspects of my job were rewarding. However, something was missing, and I made personal and professional adjustments. My schedule pulled me from valued family time with my kids (mostly) in the early mornings, therefore, I altered my work schedule. My clinical interest in IBD was diluted by the emphasis to see mostly general GI patients, as is the case for many in private practice. I missed the academic environment, especially working with medical students, residents, and fellows, so I occasionally had residents shadow me. Unfortunately, adjustments did not “fix” that missing component – to me, this was a job that did not feel like a career. I was not professionally fulfilled and on several occasions during the 6 years in private practice, I connected with mentors from my medical training to explore career options while trying to define what was missing.

During the latter part of years 5 and 6, it became apparent to me that loyalty pulled me toward working with a great group of supportive gastroenterologists, but it became increasingly more apparent that this job was not in line with my career goals. I had identified that I wanted to actively participate in medical education while practicing as a gastroenterologist in an academic setting. Additionally, time with my family was a critical part to the work-life integration.

My approach to the next step in my journey was different than my initial job. My goal was to define what was important, as in what were my absolute requirements for career satisfaction and where was I willing to be flexible. Each of us has different absolute and relative requirements based on our values, and I neglected to clearly identify these components with my first job. Admittedly, I have (at times) struggled to acknowledge my values, because I might somehow appear less committed to a career. Owning these values has provided clarity in my path from private practice to academic medicine. During the 3 years I have been in my current position, I have stepped into a leadership role in the University of Nebraska Medicine GI fellowship program while providing clinical medicine at the Fred Paustian IBD Center at Nebraska Medicine. In addition, I continue to have an active endoscopy schedule and derive great satisfaction teaching the fellows how to be effective endoscopists. Personally, the difference in compensation between academic medicine and private practice was not an important factor, although this is a factor for some people (and that’s okay).

When I graduated from fellowship, my path seemed clear, and I did not anticipate the road ahead. However, with each hurdle, I was gifted with lessons that would prove to be valuable as I moved ahead. Thank you for giving me the space to share my story.

Lessons that have helped in my journey from private practice to academics

- Mentorship: Find mentors, not just one mentor. Over the years, I have had several mentors, but what I recognize is that, early in my career, I did not have a mentor. Although a mentor cannot make decisions for you, he/she can provide guidance from a place of experience (both career and life experience).

- Define a mission statement: My mentor pushed me to first define my values and then my mission statement. This serves as the foundation that I reference when making decisions that will impact my family and my career. For example, if I am invited to participate on a committee, I look at how this will impact my family and whether it aligns with my mission. This helps to clarify what I am willing to say yes to and what to pass along to another colleague. Remember that last part ... if you are saying no to something, suggest another colleague for the opportunity.

- Advocate for yourself: Only you know what is best for you. Sometimes the path to discovering what that is can be tortuous and require guidance. Throughout my journey, I worked with colleagues who were supportive of my journey back to medical school and supportive of my job in private practice, but only I could define what a career meant to me.

- Assume positive intent: In medicine, we frequently work in a high-stakes, stressful environment. Assume positive intent in your interactions with others, especially colleagues. This will serve you well.

- Life happens: Each of us will experience an unexpected event in our personal life or career path or both. This will be okay. The path forward may look different and require a pivot. This unexpected event might be that you find your job leaves you wanting something more or something different. Your journey will be right for you.

Dr. Hutchins is an assistant professor in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha. She reported no conflicts of interest.

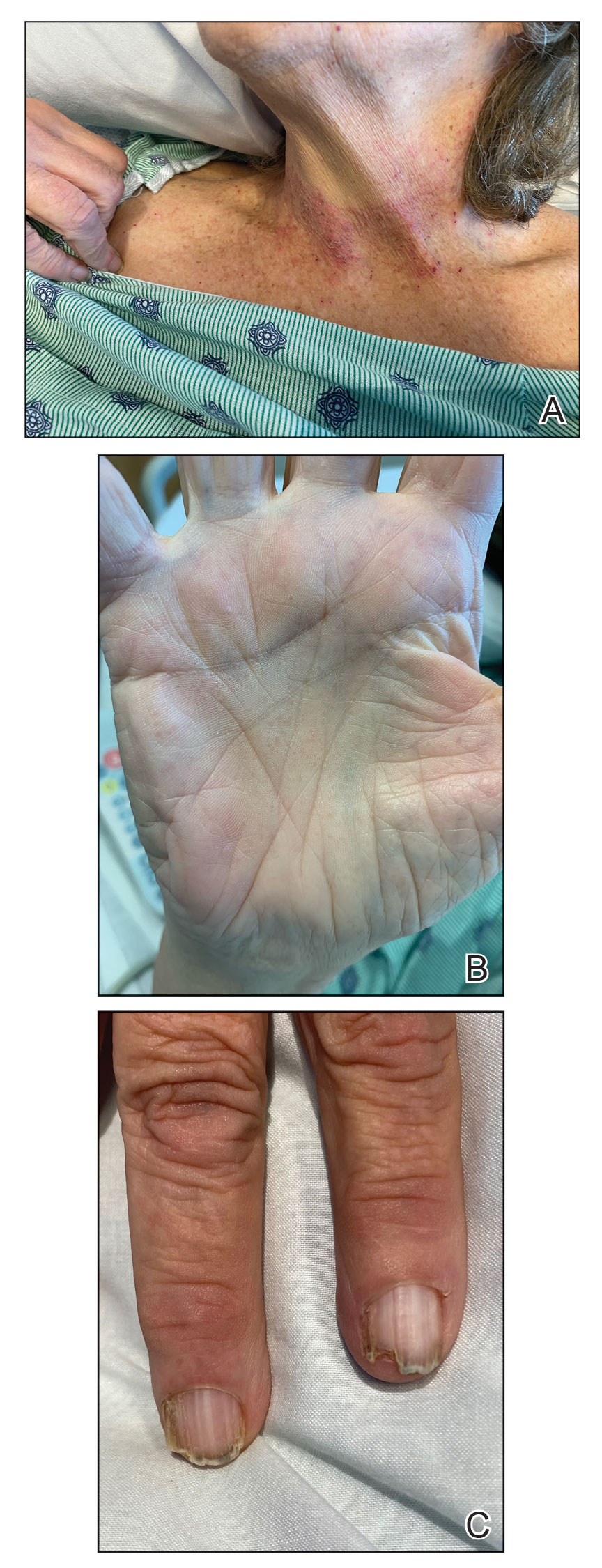

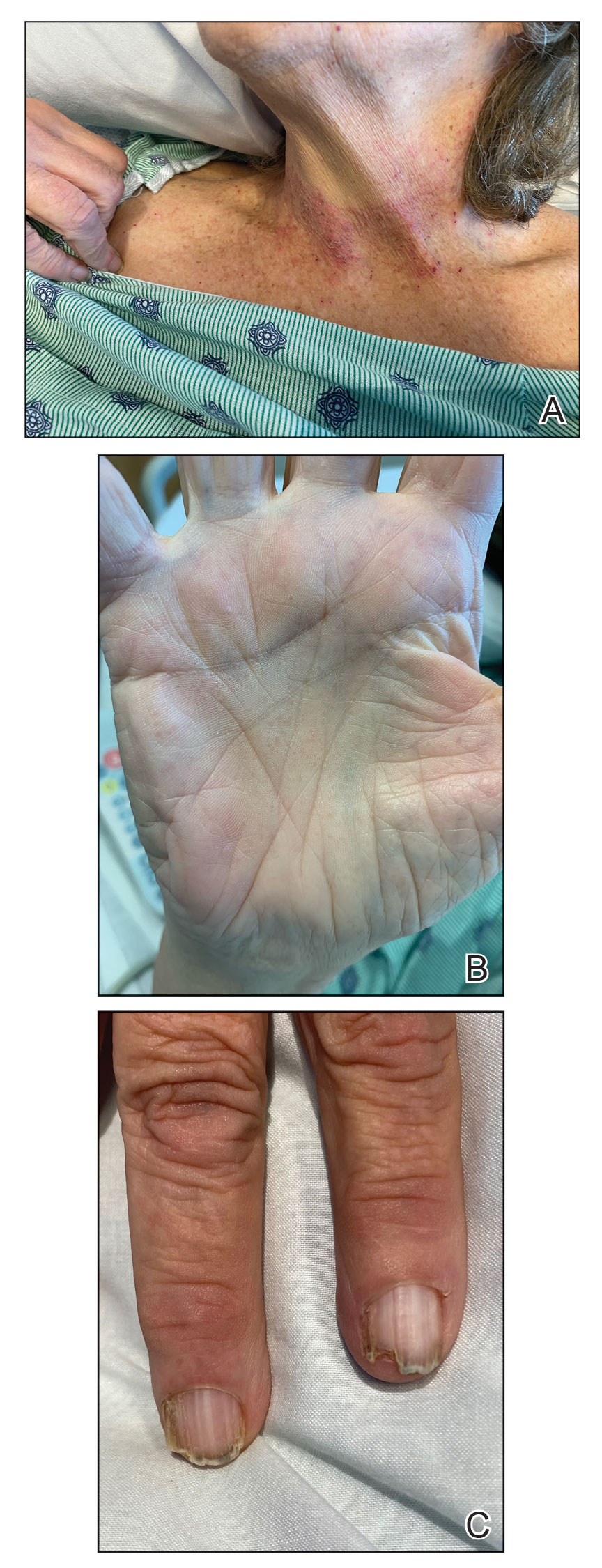

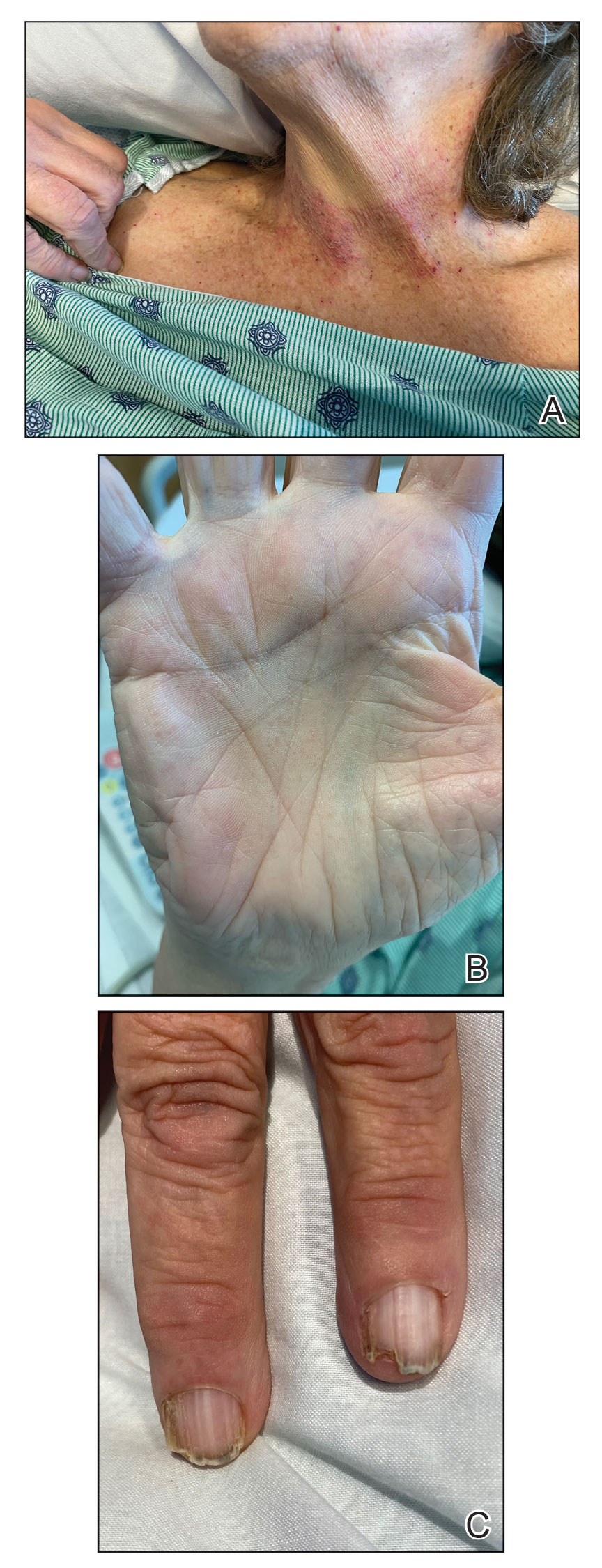

Widespread Erosions in Intertriginous Areas

The Diagnosis: Darier Disease

A clinical diagnosis of Darier disease was made from the skin findings of pruritic, malodorous, keratotic papules in a seborrheic distribution and pathognomonic nail dystrophy, along with a family history that demonstrated autosomal-dominant inheritance. The ulcerations were suspected to be caused by a superimposed herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection in the form of eczema herpeticum. The clinical diagnosis was later confirmed via punch biopsy. Pathology results demonstrated focal acantholytic dyskeratosis, which was consistent with Darier disease given the focal nature and lack of acanthosis. The patient’s father and sister also were confirmed to have Darier disease by an outside dermatologist.