User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Comments open for U.K.’s transgender care guideline

Gynecologic and obstetric health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse adults, including fertility preservation, ending masculinizing hormones in pregnancy, and support for “chest-feeding” are proposed in a novel draft guideline issued by the U.K.’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

The draft Green-top Guideline on Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is open for consultation and comment until Sept. 6. It aims to address the specific needs of transgender and gender-diverse individuals that, according to the guideline, are currently not consistently included in specialist training programs or in continuing professional development.

With a rise in the number of people seeking to transition, obstetricians and gynecologists are seeing more transgender and gender-diverse patients. Phil Rolland, MD, consultant gynecological oncologist from Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cheltenham, and member of the guideline committee, said that, “It is highly likely that if an obstetrician or gynaecologist hasn’t already consulted or treated a trans or gender-diverse patient then it is only a matter of time before they do.”

He stressed the importance of ensuring inclusivity in obstetric and gynecologic care. “We know that trans people are more likely to have poor experiences when accessing health care, and we can do better.”

The U.K.-based guideline follows a similar document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, put in place in March 2021, as reported by this news organization. It called for greater “awareness, knowledge, and sensitivity” in caring for these patients and noted that “bias from health care professionals leads to inadequate access to, underuse of, and inequities within the health care system for transgender patients.”

Guideline addresses fertility preservation, obstetric care, and more

Regarding fertility preservation, discussions around protecting future options should be held before endocrine interventions and/or gender-affirming genital or pelvic surgery procedures, says the guideline. In addition, gynecologic problems that can be experienced need to be explained.

The guideline also addresses obstetric care, advising that trans men on long-acting masculinizing hormone therapy should stop therapy 3 months prior to conception. People who conceive while taking masculinizing hormone therapy should discontinue the therapy as soon as possible.

Birth mode should be discussed with all trans men who plan to conceive, ideally at a prepregnancy counseling appointment, but at minimum, before the third trimester. Choice of feeding manner should also be addressed in the antenatal period, with trans men who wish to chest feed offered chest-feeding support, similar to that given to cis women.

The RCOG guideline comes in the wake of the U.K. government’s new Women’s Health Strategy for England, released in July, which notes that trans men (with female reproductive organs) should be able to access screening services for cervical and breast cancer, a position upheld by the RCOG guideline.

Other key recommendations include that obstetricians and gynecologists, when approached by transgender and gender-diverse people to help with identity-related issues, should liaise with gender-identity specialist services to provide appropriate care.

Removing bias, providing affirming care

Asha Kasliwal, MD, consultant in Community Gynaecology and Reproductive Health Care, Manchester, England, and president of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, also reflected on how transgender and gender-diverse people often feel uncomfortable accessing care, which could lead to, “many people failing to seek or continue health care because of concerns over how they will be treated,” adding that there were associated reports of poor clinical outcomes.

She highlighted that the draft guideline pointed out the importance of language during consultation with transgender and gender-diverse people, noting that “misuse of language, and particularly deliberate misuse of language associated with the sex assigned at birth (misgendering), may cause profound offence.”

Dr. Kasliwal cited the example of “using the correct pronouns when addressing someone and receiving any information about a person’s gender diversity neutrally and nonjudgementally.”

Edward Morris, MD, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, acknowledged that trans and gender-diverse individuals say they often feel judged and misunderstood by the health service. “This can act as a barrier for them when it comes to accessing vital care, and we as health care professionals have a role to play in making them feel listened to and recognized.”

“This draft guideline is our first attempt to ensure we are providing personalised care for all our patients,” said Dr. Morris. “We welcome feedback on this draft to ensure the guideline is the best as it can be for clinicians and the trans and gender-diverse individuals who use our services.”

The draft guideline as peer-review draft, Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is available on the RCOG website. Consultation is open until Sept. 6, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gynecologic and obstetric health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse adults, including fertility preservation, ending masculinizing hormones in pregnancy, and support for “chest-feeding” are proposed in a novel draft guideline issued by the U.K.’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

The draft Green-top Guideline on Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is open for consultation and comment until Sept. 6. It aims to address the specific needs of transgender and gender-diverse individuals that, according to the guideline, are currently not consistently included in specialist training programs or in continuing professional development.

With a rise in the number of people seeking to transition, obstetricians and gynecologists are seeing more transgender and gender-diverse patients. Phil Rolland, MD, consultant gynecological oncologist from Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cheltenham, and member of the guideline committee, said that, “It is highly likely that if an obstetrician or gynaecologist hasn’t already consulted or treated a trans or gender-diverse patient then it is only a matter of time before they do.”

He stressed the importance of ensuring inclusivity in obstetric and gynecologic care. “We know that trans people are more likely to have poor experiences when accessing health care, and we can do better.”

The U.K.-based guideline follows a similar document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, put in place in March 2021, as reported by this news organization. It called for greater “awareness, knowledge, and sensitivity” in caring for these patients and noted that “bias from health care professionals leads to inadequate access to, underuse of, and inequities within the health care system for transgender patients.”

Guideline addresses fertility preservation, obstetric care, and more

Regarding fertility preservation, discussions around protecting future options should be held before endocrine interventions and/or gender-affirming genital or pelvic surgery procedures, says the guideline. In addition, gynecologic problems that can be experienced need to be explained.

The guideline also addresses obstetric care, advising that trans men on long-acting masculinizing hormone therapy should stop therapy 3 months prior to conception. People who conceive while taking masculinizing hormone therapy should discontinue the therapy as soon as possible.

Birth mode should be discussed with all trans men who plan to conceive, ideally at a prepregnancy counseling appointment, but at minimum, before the third trimester. Choice of feeding manner should also be addressed in the antenatal period, with trans men who wish to chest feed offered chest-feeding support, similar to that given to cis women.

The RCOG guideline comes in the wake of the U.K. government’s new Women’s Health Strategy for England, released in July, which notes that trans men (with female reproductive organs) should be able to access screening services for cervical and breast cancer, a position upheld by the RCOG guideline.

Other key recommendations include that obstetricians and gynecologists, when approached by transgender and gender-diverse people to help with identity-related issues, should liaise with gender-identity specialist services to provide appropriate care.

Removing bias, providing affirming care

Asha Kasliwal, MD, consultant in Community Gynaecology and Reproductive Health Care, Manchester, England, and president of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, also reflected on how transgender and gender-diverse people often feel uncomfortable accessing care, which could lead to, “many people failing to seek or continue health care because of concerns over how they will be treated,” adding that there were associated reports of poor clinical outcomes.

She highlighted that the draft guideline pointed out the importance of language during consultation with transgender and gender-diverse people, noting that “misuse of language, and particularly deliberate misuse of language associated with the sex assigned at birth (misgendering), may cause profound offence.”

Dr. Kasliwal cited the example of “using the correct pronouns when addressing someone and receiving any information about a person’s gender diversity neutrally and nonjudgementally.”

Edward Morris, MD, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, acknowledged that trans and gender-diverse individuals say they often feel judged and misunderstood by the health service. “This can act as a barrier for them when it comes to accessing vital care, and we as health care professionals have a role to play in making them feel listened to and recognized.”

“This draft guideline is our first attempt to ensure we are providing personalised care for all our patients,” said Dr. Morris. “We welcome feedback on this draft to ensure the guideline is the best as it can be for clinicians and the trans and gender-diverse individuals who use our services.”

The draft guideline as peer-review draft, Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is available on the RCOG website. Consultation is open until Sept. 6, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Gynecologic and obstetric health care needs of transgender and gender-diverse adults, including fertility preservation, ending masculinizing hormones in pregnancy, and support for “chest-feeding” are proposed in a novel draft guideline issued by the U.K.’s Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

The draft Green-top Guideline on Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is open for consultation and comment until Sept. 6. It aims to address the specific needs of transgender and gender-diverse individuals that, according to the guideline, are currently not consistently included in specialist training programs or in continuing professional development.

With a rise in the number of people seeking to transition, obstetricians and gynecologists are seeing more transgender and gender-diverse patients. Phil Rolland, MD, consultant gynecological oncologist from Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cheltenham, and member of the guideline committee, said that, “It is highly likely that if an obstetrician or gynaecologist hasn’t already consulted or treated a trans or gender-diverse patient then it is only a matter of time before they do.”

He stressed the importance of ensuring inclusivity in obstetric and gynecologic care. “We know that trans people are more likely to have poor experiences when accessing health care, and we can do better.”

The U.K.-based guideline follows a similar document from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, put in place in March 2021, as reported by this news organization. It called for greater “awareness, knowledge, and sensitivity” in caring for these patients and noted that “bias from health care professionals leads to inadequate access to, underuse of, and inequities within the health care system for transgender patients.”

Guideline addresses fertility preservation, obstetric care, and more

Regarding fertility preservation, discussions around protecting future options should be held before endocrine interventions and/or gender-affirming genital or pelvic surgery procedures, says the guideline. In addition, gynecologic problems that can be experienced need to be explained.

The guideline also addresses obstetric care, advising that trans men on long-acting masculinizing hormone therapy should stop therapy 3 months prior to conception. People who conceive while taking masculinizing hormone therapy should discontinue the therapy as soon as possible.

Birth mode should be discussed with all trans men who plan to conceive, ideally at a prepregnancy counseling appointment, but at minimum, before the third trimester. Choice of feeding manner should also be addressed in the antenatal period, with trans men who wish to chest feed offered chest-feeding support, similar to that given to cis women.

The RCOG guideline comes in the wake of the U.K. government’s new Women’s Health Strategy for England, released in July, which notes that trans men (with female reproductive organs) should be able to access screening services for cervical and breast cancer, a position upheld by the RCOG guideline.

Other key recommendations include that obstetricians and gynecologists, when approached by transgender and gender-diverse people to help with identity-related issues, should liaise with gender-identity specialist services to provide appropriate care.

Removing bias, providing affirming care

Asha Kasliwal, MD, consultant in Community Gynaecology and Reproductive Health Care, Manchester, England, and president of the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, also reflected on how transgender and gender-diverse people often feel uncomfortable accessing care, which could lead to, “many people failing to seek or continue health care because of concerns over how they will be treated,” adding that there were associated reports of poor clinical outcomes.

She highlighted that the draft guideline pointed out the importance of language during consultation with transgender and gender-diverse people, noting that “misuse of language, and particularly deliberate misuse of language associated with the sex assigned at birth (misgendering), may cause profound offence.”

Dr. Kasliwal cited the example of “using the correct pronouns when addressing someone and receiving any information about a person’s gender diversity neutrally and nonjudgementally.”

Edward Morris, MD, president of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, acknowledged that trans and gender-diverse individuals say they often feel judged and misunderstood by the health service. “This can act as a barrier for them when it comes to accessing vital care, and we as health care professionals have a role to play in making them feel listened to and recognized.”

“This draft guideline is our first attempt to ensure we are providing personalised care for all our patients,” said Dr. Morris. “We welcome feedback on this draft to ensure the guideline is the best as it can be for clinicians and the trans and gender-diverse individuals who use our services.”

The draft guideline as peer-review draft, Care of Trans and Gender Diverse Adults in Obstetrics and Gynaecology is available on the RCOG website. Consultation is open until Sept. 6, 2022.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

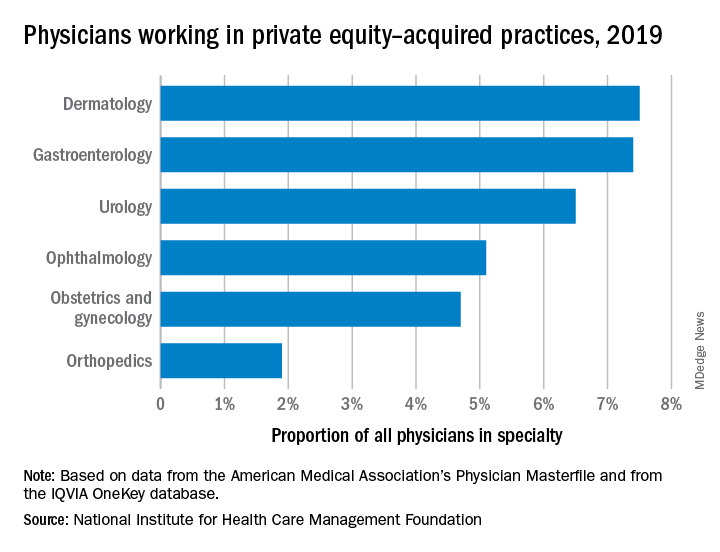

Six specialties attracting the highest private equity acquisitions

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

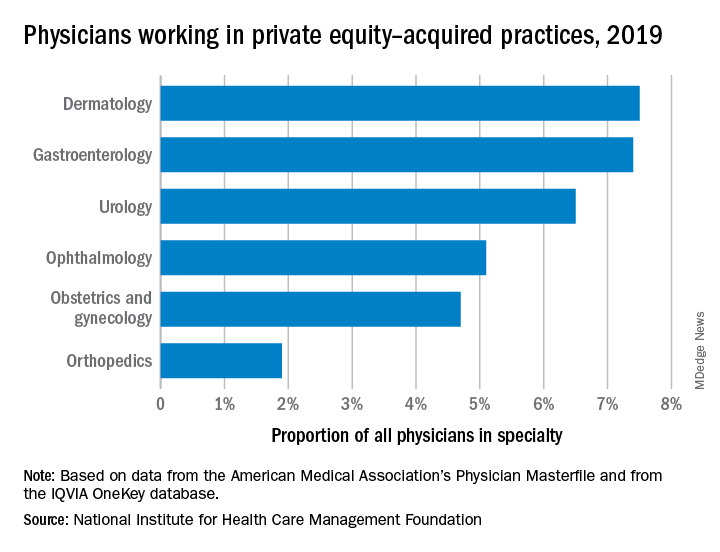

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

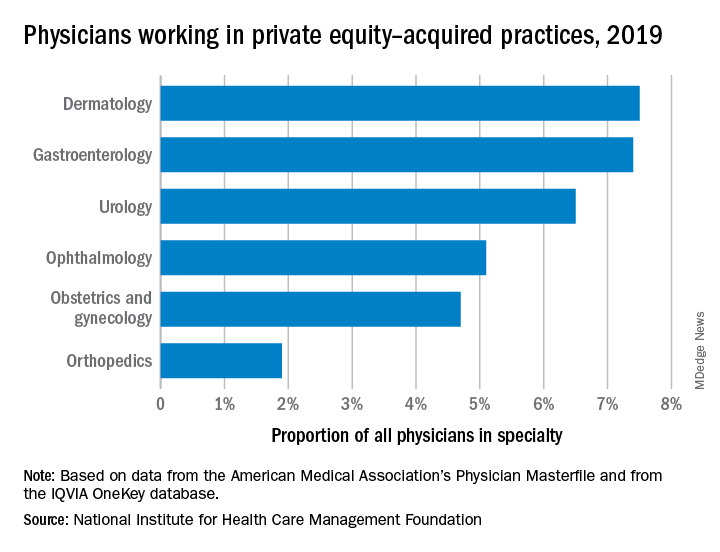

While tracking the extent of physician practice acquisition by private equity firms may be difficult, new research highlights what specialties and U.S. regions are most affected by such purchases.

The study, supported by the National Institute for Health Care Management (NIHCM), examined 97,094 physicians practicing in six specialties, 4,738 of whom worked in private equity–acquired practices. Of these specialties,

“These specialties offer private equity firms diverse revenue streams. You have a mix of commercially insured individuals with Medicare insurance and self-pay,” said Yashaswini Singh, MPA, a doctoral student at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, and coauthor of the study, which was published in JAMA Health Forum as a research letter.

“In dermatology, you have a mix of surgical procedures that are covered under insurance, but also a lot of cosmetic procedures that are most likely to be self-pay procedures. This offers private equity several mechanisms to which they can increase their revenues.”

Ms. Singh’s coauthors were part of a previous study looking at private practice penetration by private equity firms. That research found such deals surged from 59 deals in 2013 representing 843 physicians, to 136 private equity acquisition deals representing 1,882 physicians in 2016.

The most recent study notes limited data and use of nondisclosure agreements during early negotiations as part of the difficulty in truly pinpointing private equity’s presence in health care. Monitoring private equity activity has become necessary across all industries, noted the authors of the study. If continued at this rate, long-term private equity acquisition has a multitude of potential pros and cons.

Ms. Singh explained that such specialties are highly fragmented and they allow for economies of scale and scope. In particular, an aging population increases demand for dermatology, ophthalmology, and gastroenterology services such as skin biopsies, cataracts, and colonoscopies. This makes these specialties very attractive to private equity firms. The same can be said for obstetrics and gynecology, as fertility clinics have attracted many private equity investments.

“This is another area where understanding changes to physician practice patterns and patient outcomes is critical as women continue to delay motherhood,” said Ms. Singh.

Reducing competition, increasing focus on patient care

Researchers found significant geographical trends for private equity penetration, as it varies across the country. It is highest in the Northeast, Florida, and Arizona in hospital referral regions. Researchers are still analyzing the cause of this occurrence.

Geographic concentration of private equity penetration likely reflects strategic selection of investment opportunities by private equity funds as the decision to invest in a practice does not happen at random, Ms. Singh noted.

Ms. Singh said she hopes that by documenting a variation and geographic concentration that the NIHCM is providing the first foundational step to tackle questions related to incentives and regulations that facilitate investment.

“Understanding the regulatory and economic environments that facilitate private equity activity is an interesting and important question to explore further,” she said in an interview. “This can include supply-side factors that can shape the business environment, e.g., taxation environment, regulatory burden to complete acquisitions, as well as demand-side factors that facilitate growth.”

Researchers found that continued growth of private equity penetration may lead to consolidation among independent practices facing financial pressures, as well as reduced competition and increased prices within each local health care market.

“Localized consolidation in certain markets has the potential for competition to reduce, [and] reduced competition has been shown in a variety of settings to be associated with increases in prices and reduced access for patients,” said Ms. Singh.

Conversely, Ms. Singh addressed several benefits of growing private equity presence. Companies can exploit their full potential through the addition of private equity expertise and contacts. Specifically, health care development of technological infrastructure is likely, along with reduced patient wait times and the expansion of business hours. It could also be a way for practices to offload administrative responsibilities and for physicians to focus more on the care delivery process.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

Node-negative triple-negative breast cancer prognosis lies within stromal lymphocytes

and may be suitable candidates for reduced intensity pre- or postoperative chemotherapy, according to a team of European investigators.

Among 441 women in a Dutch cancer registry who were younger than 40 when they were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC and had not undergone systemic therapy, those who had 75% or more TILs in the intratumoral stromal area had a 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases or death of just 2.1%, and every 10% increase in sTILs was associated with a 19% decrease in the risk of death.

In contrast, the 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases was 38.4% for women with stromal TIL scores of less than 30%, according to researchers writing in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“These data could be used as a starting point for designing a randomized controlled chemotherapy de-escalation trial. The current study confirms the importance of sTILs as a valuable addition to the set of standard prognostic factors in patients with TNBC,” wrote the researchers, who were led by Sabine C. Linn, MD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam.

Markers for immune response

Stromal TILs, a mixture of mononuclear immune cells, have been shown in previous studies to be prognostic for outcomes in patients with early-stage TNBC treated either with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

For example, investigators cited a study published in JCO in 2014, that showed among women with TNBC enrolled in the phase 3 ECOG 2197 clinical trial and the related ECOG 119 clinical trial, after a nearly 11-year follow-up, higher sTIL scores were associated with significantly better prognosis with every 10% increase translating into a 14% reduction in the risk of recurrence or death (P = .02).

“The prognostic importance of sTILs is, however, unexplored in patients diagnosed under age 40 years, let alone in the subgroup of systemic therapy–naive patients,” Dr. Linn and colleagues wrote.

Retrospective study

To see whether the prognostic value of sTILs was as strong among young, systemic therapy–naive women, the investigators conducted a retrospective study of women enrolled in the Netherlands Cancer Registry who were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC from 1989 to 2000. The patients selected had undergone only locoregional treatment, including axillary node dissection, but had not received any systemic therapy.

Pathologists reviewed samples, with TILs reported for the stromal compartment. The samples were grouped by sTIL score categories of high (75% or greater), intermediate (30% to less than 75%), or low (less than 30%). The investigators looked at overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) stratified by sTIL scores,

During a median follow-up of 15 years, 107 women died or developed distant metastases, and 78 experienced a second primary cancer.

The results were as noted, with patients in the highest category of sTILs having very low rates of either death or distant metastases during follow-up.

“We confirm the prognostic value of sTILs in young patients with early-stage N0 TNBC who are systemic therapy naive by taking advantage of a prospectively collected population-based cohort. Increasing sTILs are significantly associated with improved OS and DMFS. Patients with high sTILs (> 75%) had an excellent 10-year overall survival and a very low 10-year incidence of distant metastasis or death.

The study was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, A Sister’s Hope, De Vrienden van UMC Utrecht, Agilent Technologies, the Dutch Cancer Society, and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Linn reported consulting with and receiving compensation from Daiichi Sankyo, as well as receiving research funding from Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Tesaro, Merck, Immunomedics, Eurocept Pharmaceuticals, Agendia, and Novartis.

and may be suitable candidates for reduced intensity pre- or postoperative chemotherapy, according to a team of European investigators.

Among 441 women in a Dutch cancer registry who were younger than 40 when they were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC and had not undergone systemic therapy, those who had 75% or more TILs in the intratumoral stromal area had a 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases or death of just 2.1%, and every 10% increase in sTILs was associated with a 19% decrease in the risk of death.

In contrast, the 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases was 38.4% for women with stromal TIL scores of less than 30%, according to researchers writing in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“These data could be used as a starting point for designing a randomized controlled chemotherapy de-escalation trial. The current study confirms the importance of sTILs as a valuable addition to the set of standard prognostic factors in patients with TNBC,” wrote the researchers, who were led by Sabine C. Linn, MD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam.

Markers for immune response

Stromal TILs, a mixture of mononuclear immune cells, have been shown in previous studies to be prognostic for outcomes in patients with early-stage TNBC treated either with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

For example, investigators cited a study published in JCO in 2014, that showed among women with TNBC enrolled in the phase 3 ECOG 2197 clinical trial and the related ECOG 119 clinical trial, after a nearly 11-year follow-up, higher sTIL scores were associated with significantly better prognosis with every 10% increase translating into a 14% reduction in the risk of recurrence or death (P = .02).

“The prognostic importance of sTILs is, however, unexplored in patients diagnosed under age 40 years, let alone in the subgroup of systemic therapy–naive patients,” Dr. Linn and colleagues wrote.

Retrospective study

To see whether the prognostic value of sTILs was as strong among young, systemic therapy–naive women, the investigators conducted a retrospective study of women enrolled in the Netherlands Cancer Registry who were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC from 1989 to 2000. The patients selected had undergone only locoregional treatment, including axillary node dissection, but had not received any systemic therapy.

Pathologists reviewed samples, with TILs reported for the stromal compartment. The samples were grouped by sTIL score categories of high (75% or greater), intermediate (30% to less than 75%), or low (less than 30%). The investigators looked at overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) stratified by sTIL scores,

During a median follow-up of 15 years, 107 women died or developed distant metastases, and 78 experienced a second primary cancer.

The results were as noted, with patients in the highest category of sTILs having very low rates of either death or distant metastases during follow-up.

“We confirm the prognostic value of sTILs in young patients with early-stage N0 TNBC who are systemic therapy naive by taking advantage of a prospectively collected population-based cohort. Increasing sTILs are significantly associated with improved OS and DMFS. Patients with high sTILs (> 75%) had an excellent 10-year overall survival and a very low 10-year incidence of distant metastasis or death.

The study was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, A Sister’s Hope, De Vrienden van UMC Utrecht, Agilent Technologies, the Dutch Cancer Society, and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Linn reported consulting with and receiving compensation from Daiichi Sankyo, as well as receiving research funding from Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Tesaro, Merck, Immunomedics, Eurocept Pharmaceuticals, Agendia, and Novartis.

and may be suitable candidates for reduced intensity pre- or postoperative chemotherapy, according to a team of European investigators.

Among 441 women in a Dutch cancer registry who were younger than 40 when they were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC and had not undergone systemic therapy, those who had 75% or more TILs in the intratumoral stromal area had a 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases or death of just 2.1%, and every 10% increase in sTILs was associated with a 19% decrease in the risk of death.

In contrast, the 15-year cumulative incidence of distant metastases was 38.4% for women with stromal TIL scores of less than 30%, according to researchers writing in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

“These data could be used as a starting point for designing a randomized controlled chemotherapy de-escalation trial. The current study confirms the importance of sTILs as a valuable addition to the set of standard prognostic factors in patients with TNBC,” wrote the researchers, who were led by Sabine C. Linn, MD, of the Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam.

Markers for immune response

Stromal TILs, a mixture of mononuclear immune cells, have been shown in previous studies to be prognostic for outcomes in patients with early-stage TNBC treated either with or without neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy.

For example, investigators cited a study published in JCO in 2014, that showed among women with TNBC enrolled in the phase 3 ECOG 2197 clinical trial and the related ECOG 119 clinical trial, after a nearly 11-year follow-up, higher sTIL scores were associated with significantly better prognosis with every 10% increase translating into a 14% reduction in the risk of recurrence or death (P = .02).

“The prognostic importance of sTILs is, however, unexplored in patients diagnosed under age 40 years, let alone in the subgroup of systemic therapy–naive patients,” Dr. Linn and colleagues wrote.

Retrospective study

To see whether the prognostic value of sTILs was as strong among young, systemic therapy–naive women, the investigators conducted a retrospective study of women enrolled in the Netherlands Cancer Registry who were diagnosed with node-negative TNBC from 1989 to 2000. The patients selected had undergone only locoregional treatment, including axillary node dissection, but had not received any systemic therapy.

Pathologists reviewed samples, with TILs reported for the stromal compartment. The samples were grouped by sTIL score categories of high (75% or greater), intermediate (30% to less than 75%), or low (less than 30%). The investigators looked at overall survival (OS) and distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) stratified by sTIL scores,

During a median follow-up of 15 years, 107 women died or developed distant metastases, and 78 experienced a second primary cancer.

The results were as noted, with patients in the highest category of sTILs having very low rates of either death or distant metastases during follow-up.

“We confirm the prognostic value of sTILs in young patients with early-stage N0 TNBC who are systemic therapy naive by taking advantage of a prospectively collected population-based cohort. Increasing sTILs are significantly associated with improved OS and DMFS. Patients with high sTILs (> 75%) had an excellent 10-year overall survival and a very low 10-year incidence of distant metastasis or death.

The study was supported by grants from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, A Sister’s Hope, De Vrienden van UMC Utrecht, Agilent Technologies, the Dutch Cancer Society, and Breast Cancer Research Foundation. Dr. Linn reported consulting with and receiving compensation from Daiichi Sankyo, as well as receiving research funding from Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Tesaro, Merck, Immunomedics, Eurocept Pharmaceuticals, Agendia, and Novartis.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Routine weight counseling urged for women at midlife

Midlife women who are of normal weight or are overweight should routinely receive counseling aimed at limiting weight gain and preventing obesity and its associated health risks, a new clinical guideline states.

The recommendation, issued by the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), supports regular lifestyle counseling for women aged 40-60 years with normal or overweight body mass index of 18.5-29.9 kg/m2. Counseling could include individualized discussion of healthy eating and physical activity initiated by health professionals involved in preventive care.

Published online in Annals of Internal Medicine, the guideline addresses the prevalence and health burdens of obesity in U.S. women of middle age and seeks to reduce the known harms of obesity with an intervention of minimal anticipated harms. High BMI increases the risk for many chronic conditions including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

The best way to counsel, however, remains unclear. “Although the optimal approach could not be discerned from existing trials, a range of interventions of varying duration, frequency, and intensity showed benefit with potential clinical significance,” wrote the WPSI guideline panel, led by David P. Chelmow, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

The guideline rests on a systematic literature review led by family doctor Amy G. Cantor, MD, MPH, of the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, suggesting moderate reductions in weight could be achieved by offering advice to this age group.

The federally supported WPSI was launched by ACOG in 2016. The guideline fills a gap in current recommendations in that it targets a specific risk group and specifies individual counseling based on its effectiveness and applicability in primary care settings.

In another benefit of routine counseling, the panel stated, “Normalizing counseling about healthy diet and physical activity by providing it to all midlife women may also mitigate concerns about weight stigma resulting from only counseling women with obesity.”

The panelists noted that during 2017-2018, the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) was 43.3% among U.S. women aged 40-59 years, while the prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2) was highest in this age group at 11.5%. “Midlife women gain weight at an average of approximately 1.5 pounds per year, which increases their risk for transitioning from normal or overweight to obese BMI,” the panelists wrote.

The review

Dr. Cantor’s group analyzed seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published up to October 2021 from 12 publications involving 51,638 participants. Although the trials were largely small and heterogeneous, they suggested that counseling may result in modest differences in weight change without causing important harms.

Four RCTs showed significant favorable weight changes for counseling over no-counseling control groups, with a mean difference of 0.87 to 2.5 kg, whereas one trial of counseling and two trials of exercise showed no differences. One of two RCTs reported improved quality-of-life measures.

As for harms, while interventions did not increase measures of depression or stress in one trial, self-reported falls (37% vs. 29%, P < .001) and injuries (19% vs. 14%, P = .03) were more frequent with exercise counseling in one trial.

“More research is needed to determine optimal content, frequency, length, and number of sessions required and should include additional patient populations,” Dr. Cantor and associates wrote.

In terms of limitations, the authors acknowledged that trials of behavioral interventions in maintaining or reducing weight in midlife women demonstrate small magnitudes of effect.

Offering a nonparticipant’s perspective on the WPSI guideline for this news organization, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, MACP, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said its message is of prime importance for women of middle age and it goes beyond concern about pounds lost or gained.

“Midlife and the transition to menopause are high-risk periods for women in terms of typical changes in body composition that increase the risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes,” said Dr. Manson, professor of women’s health at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Counseling women should be a priority for physicians in clinical practice. And it’s not just whether weight gain is reflected on the scales or not but whether there’s an increase in central abdominal fat, a decrease in lean muscle mass, and an increase in adverse glucose tolerance.”

It is essential for women to be vigilant at this time, she added, and their exercise regimens should include strength and resistance training to preserve lean muscle mass and boost metabolic rate. Dr. Manson’s group has issued several statements stressing how important it is for clinicians to take decisive action on the counseling front and how they can do this in very little time during routine practice.

Also in full support of the guideline is Mary L. Rosser, MD, PhD, assistant professor of women’s health in obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “Midlife is a wonderful opportunity to encourage patients to assess their overall health status and make changes to impact their future health. Women in middle age tend to experience weight gain due to a variety of factors including aging and lifestyle,” said Dr. Rosser, who was not involved in the writing of the review or guideline.

While aging and genetics cannot be altered, behaviors can, and in her view, favorable behaviors would also include stress reduction and adequate sleep.

“The importance of reducing obesity with early intervention and prevention must focus on all women,” Dr. Rosser said. “We must narrow the inequities gap in care especially for high-risk minority groups and underserved populations. This will reduce disease and death and provide women the gift of active living and feeling better.”

The WPSI authors have made available a summary of the review and guideline for patients.

The systematic review and clinical guideline were funded by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration through ACOG. The authors of the guideline and the review authors disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Manson and Dr. Rosser disclosed no relevant competing interests with regard to their comments.

Midlife women who are of normal weight or are overweight should routinely receive counseling aimed at limiting weight gain and preventing obesity and its associated health risks, a new clinical guideline states.

The recommendation, issued by the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), supports regular lifestyle counseling for women aged 40-60 years with normal or overweight body mass index of 18.5-29.9 kg/m2. Counseling could include individualized discussion of healthy eating and physical activity initiated by health professionals involved in preventive care.

Published online in Annals of Internal Medicine, the guideline addresses the prevalence and health burdens of obesity in U.S. women of middle age and seeks to reduce the known harms of obesity with an intervention of minimal anticipated harms. High BMI increases the risk for many chronic conditions including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

The best way to counsel, however, remains unclear. “Although the optimal approach could not be discerned from existing trials, a range of interventions of varying duration, frequency, and intensity showed benefit with potential clinical significance,” wrote the WPSI guideline panel, led by David P. Chelmow, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

The guideline rests on a systematic literature review led by family doctor Amy G. Cantor, MD, MPH, of the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, suggesting moderate reductions in weight could be achieved by offering advice to this age group.

The federally supported WPSI was launched by ACOG in 2016. The guideline fills a gap in current recommendations in that it targets a specific risk group and specifies individual counseling based on its effectiveness and applicability in primary care settings.

In another benefit of routine counseling, the panel stated, “Normalizing counseling about healthy diet and physical activity by providing it to all midlife women may also mitigate concerns about weight stigma resulting from only counseling women with obesity.”

The panelists noted that during 2017-2018, the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) was 43.3% among U.S. women aged 40-59 years, while the prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2) was highest in this age group at 11.5%. “Midlife women gain weight at an average of approximately 1.5 pounds per year, which increases their risk for transitioning from normal or overweight to obese BMI,” the panelists wrote.

The review

Dr. Cantor’s group analyzed seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published up to October 2021 from 12 publications involving 51,638 participants. Although the trials were largely small and heterogeneous, they suggested that counseling may result in modest differences in weight change without causing important harms.

Four RCTs showed significant favorable weight changes for counseling over no-counseling control groups, with a mean difference of 0.87 to 2.5 kg, whereas one trial of counseling and two trials of exercise showed no differences. One of two RCTs reported improved quality-of-life measures.

As for harms, while interventions did not increase measures of depression or stress in one trial, self-reported falls (37% vs. 29%, P < .001) and injuries (19% vs. 14%, P = .03) were more frequent with exercise counseling in one trial.

“More research is needed to determine optimal content, frequency, length, and number of sessions required and should include additional patient populations,” Dr. Cantor and associates wrote.

In terms of limitations, the authors acknowledged that trials of behavioral interventions in maintaining or reducing weight in midlife women demonstrate small magnitudes of effect.

Offering a nonparticipant’s perspective on the WPSI guideline for this news organization, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, MACP, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said its message is of prime importance for women of middle age and it goes beyond concern about pounds lost or gained.

“Midlife and the transition to menopause are high-risk periods for women in terms of typical changes in body composition that increase the risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes,” said Dr. Manson, professor of women’s health at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Counseling women should be a priority for physicians in clinical practice. And it’s not just whether weight gain is reflected on the scales or not but whether there’s an increase in central abdominal fat, a decrease in lean muscle mass, and an increase in adverse glucose tolerance.”

It is essential for women to be vigilant at this time, she added, and their exercise regimens should include strength and resistance training to preserve lean muscle mass and boost metabolic rate. Dr. Manson’s group has issued several statements stressing how important it is for clinicians to take decisive action on the counseling front and how they can do this in very little time during routine practice.

Also in full support of the guideline is Mary L. Rosser, MD, PhD, assistant professor of women’s health in obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “Midlife is a wonderful opportunity to encourage patients to assess their overall health status and make changes to impact their future health. Women in middle age tend to experience weight gain due to a variety of factors including aging and lifestyle,” said Dr. Rosser, who was not involved in the writing of the review or guideline.

While aging and genetics cannot be altered, behaviors can, and in her view, favorable behaviors would also include stress reduction and adequate sleep.

“The importance of reducing obesity with early intervention and prevention must focus on all women,” Dr. Rosser said. “We must narrow the inequities gap in care especially for high-risk minority groups and underserved populations. This will reduce disease and death and provide women the gift of active living and feeling better.”

The WPSI authors have made available a summary of the review and guideline for patients.

The systematic review and clinical guideline were funded by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration through ACOG. The authors of the guideline and the review authors disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Manson and Dr. Rosser disclosed no relevant competing interests with regard to their comments.

Midlife women who are of normal weight or are overweight should routinely receive counseling aimed at limiting weight gain and preventing obesity and its associated health risks, a new clinical guideline states.

The recommendation, issued by the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), supports regular lifestyle counseling for women aged 40-60 years with normal or overweight body mass index of 18.5-29.9 kg/m2. Counseling could include individualized discussion of healthy eating and physical activity initiated by health professionals involved in preventive care.

Published online in Annals of Internal Medicine, the guideline addresses the prevalence and health burdens of obesity in U.S. women of middle age and seeks to reduce the known harms of obesity with an intervention of minimal anticipated harms. High BMI increases the risk for many chronic conditions including hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, stroke, and all-cause mortality.

The best way to counsel, however, remains unclear. “Although the optimal approach could not be discerned from existing trials, a range of interventions of varying duration, frequency, and intensity showed benefit with potential clinical significance,” wrote the WPSI guideline panel, led by David P. Chelmow, MD, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond.

The guideline rests on a systematic literature review led by family doctor Amy G. Cantor, MD, MPH, of the Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, suggesting moderate reductions in weight could be achieved by offering advice to this age group.

The federally supported WPSI was launched by ACOG in 2016. The guideline fills a gap in current recommendations in that it targets a specific risk group and specifies individual counseling based on its effectiveness and applicability in primary care settings.

In another benefit of routine counseling, the panel stated, “Normalizing counseling about healthy diet and physical activity by providing it to all midlife women may also mitigate concerns about weight stigma resulting from only counseling women with obesity.”

The panelists noted that during 2017-2018, the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30.0 kg/m2) was 43.3% among U.S. women aged 40-59 years, while the prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥ 40.0 kg/m2) was highest in this age group at 11.5%. “Midlife women gain weight at an average of approximately 1.5 pounds per year, which increases their risk for transitioning from normal or overweight to obese BMI,” the panelists wrote.

The review

Dr. Cantor’s group analyzed seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published up to October 2021 from 12 publications involving 51,638 participants. Although the trials were largely small and heterogeneous, they suggested that counseling may result in modest differences in weight change without causing important harms.

Four RCTs showed significant favorable weight changes for counseling over no-counseling control groups, with a mean difference of 0.87 to 2.5 kg, whereas one trial of counseling and two trials of exercise showed no differences. One of two RCTs reported improved quality-of-life measures.

As for harms, while interventions did not increase measures of depression or stress in one trial, self-reported falls (37% vs. 29%, P < .001) and injuries (19% vs. 14%, P = .03) were more frequent with exercise counseling in one trial.

“More research is needed to determine optimal content, frequency, length, and number of sessions required and should include additional patient populations,” Dr. Cantor and associates wrote.

In terms of limitations, the authors acknowledged that trials of behavioral interventions in maintaining or reducing weight in midlife women demonstrate small magnitudes of effect.

Offering a nonparticipant’s perspective on the WPSI guideline for this news organization, JoAnn E. Manson, MD, DrPH, MACP, chief of the division of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, said its message is of prime importance for women of middle age and it goes beyond concern about pounds lost or gained.

“Midlife and the transition to menopause are high-risk periods for women in terms of typical changes in body composition that increase the risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes,” said Dr. Manson, professor of women’s health at Harvard Medical School, Boston. “Counseling women should be a priority for physicians in clinical practice. And it’s not just whether weight gain is reflected on the scales or not but whether there’s an increase in central abdominal fat, a decrease in lean muscle mass, and an increase in adverse glucose tolerance.”

It is essential for women to be vigilant at this time, she added, and their exercise regimens should include strength and resistance training to preserve lean muscle mass and boost metabolic rate. Dr. Manson’s group has issued several statements stressing how important it is for clinicians to take decisive action on the counseling front and how they can do this in very little time during routine practice.

Also in full support of the guideline is Mary L. Rosser, MD, PhD, assistant professor of women’s health in obstetrics and gynecology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “Midlife is a wonderful opportunity to encourage patients to assess their overall health status and make changes to impact their future health. Women in middle age tend to experience weight gain due to a variety of factors including aging and lifestyle,” said Dr. Rosser, who was not involved in the writing of the review or guideline.

While aging and genetics cannot be altered, behaviors can, and in her view, favorable behaviors would also include stress reduction and adequate sleep.

“The importance of reducing obesity with early intervention and prevention must focus on all women,” Dr. Rosser said. “We must narrow the inequities gap in care especially for high-risk minority groups and underserved populations. This will reduce disease and death and provide women the gift of active living and feeling better.”

The WPSI authors have made available a summary of the review and guideline for patients.

The systematic review and clinical guideline were funded by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration through ACOG. The authors of the guideline and the review authors disclosed no relevant financial conflicts of interest. Dr. Manson and Dr. Rosser disclosed no relevant competing interests with regard to their comments.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

How doctors are weighing the legal risks of abortion care

The names of the doctors in this story have been changed at their request because of fear of legal repercussions and/or professional retaliation.

When an Ohio ob.gyn. had a patient in need of an abortion in July 2022, he knew he had to move quickly.

Daniel, who also sees patients at an abortion clinic, was treating a woman who came in for an abortion around 5 weeks into her pregnancy. And after going through the mandatory waiting periods, the required ultrasounds at each appointment, the consent process, and the options counseling, she was set for a surgical abortion the following Monday.

But on Monday, pre-op tests showed that her blood pressure was very high, posing a serious health risk if Daniel proceeded with the surgery.

Before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Daniel would have sent the patient home with instructions on how to lower her blood pressure over time. But the patient now had just four days to show the necessary improvement.

In this case, everything worked out. The patient returned Thursday and was able to have the procedure. But this is just one of the many day-to-day medical decisions abortion providers are now having to make with the changing legal risks being as top-of-mind to doctors as the safety of their patients.

Daniel said he doesn’t want the Ohio abortion law to change the way he communicates with his patients. As far as he knows, it’s still legal to talk to patients about self-managed abortions, as long as everything is unbiased and clearly stated, he says.

“But I don’t think I would get a lot of institutional support to have those conversations with patients because of the perceived legal liability,” says Daniel. “I will still have those conversations, but I’m not going to tell my employer that I’m having them and I’m not going to document them in the chart.”

Daniel is aware that having these kinds of discussions, or entertaining the possibility of omitting certain information from patient records, runs the risk of legal and professional consequences. Enforcement of these rules is foggy, too.

Under the Ohio law, if a fellow staff member suspects you of violating a law, you could be reported to a supervisor or licensing body. Abortion providers are aware they must be cautious about what they say because anti-abortion activitists, posing as patients, have secretly recorded conversations in the past, Daniel says.

Enforcement: The past, present, and future legal risks

Before Roe, enforcement of illegal abortion was spotty, says Mary Ziegler, JD, a professor at Florida State University College of Law, who specializes in the legal history of reproductive rights. At the start of the late 19th century, the doctors who provided illegal abortions would, in most cases, be prosecuted if a patient died as a result of the procedure.

A doctor in Ashland, Pa., named Robert Spencer was known for providing abortions in the small mining town where he practiced in the 1920s. He was reportedly arrested three times – once after a patient died as a result of abortion complications – but was ultimately acquitted.

For many doctors performing abortions at the time, “it was very much a kind of roll of the dice,” Ms. Ziegler says. “There was a sense that these laws were not enforced very much.”

Carole Joffe, PhD, a sociologist with expertise in reproductive health, recalls that there were very few doctors arrested, given the sheer number of abortions that were performed. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists estimates that, in the years leading up to the original Roe decision, about 1.2 million women in the U.S. had illegal abortions – a number that exceeds today’s estimates.

Among the most notable cases of a doctor being detained was the arrest of gynecologist Jane Hodgson, MD, in 1970. Dr. Hodgson intentionally violated Minnesota law, which prohibited all abortions except in cases that were life-threatening to the patient.

After performing an abortion on a patient who had contracted rubella, also known as German measles, Dr. Hodgson was arrested, sentenced to 30 days in jail, and put on a year-long probation. She did not end up serving any time in jail, and her conviction was overturned after the Roe decision in 1973.

Now, the abortion restrictions being passed in many states have authorized much more sweeping penalties than those that existed in the pre-Roe era. According to Joffe, there is one key reason why we can anticipate more doctor arrests now.

“There simply was not the modern anti-abortion movement that we have come to know,” she says. “In the old days, there was not that much legal surveillance, and things were very unsafe. Fast forward to the present, we have much safer options now – like medication abortion pills – but we have a very different legal environment.”

Carmel Shachar, JD, MPH, a law and health policy expert at Harvard Law School, also expects that we will see more frequent prosecutions of doctors who provide abortion.

“There’s so much more data available through medical record-keeping and information generated by our phones and internet searches, that I think it would be much harder for a physician to fly under the radar,” Ms. Shachar says.

Also, Ms. Shachar emphasizes the power of prosecutorial discretion in abortion cases, where one prosecutor may choose to apply a law much more aggressively than another prosecutor in the next county over. Such has been seen in DeKalb County, Ga., which includes parts of Atlanta, where District Attorney Sherry Boston says she plans to use her prosecutorial discretion to address crimes like rape and murder, rather than “potentially investigat[ing] women and doctors for medical decisions,” Bloomberg Law reported. State Sen. Jen Jordan, the Democratic nominee for Georgia attorney general, has also said that, if elected, she would not enforce the state’s new 6-week abortion ban.

Is there a legal path forward for abortion care in states that forbid it?

Robin, an ob.gyn., became a complex family planning fellow in Utah to seek out further medical training and education in abortion care. Her plan was to solidify this as an area of expertise, so that, upon completing her fellowship, she could move back to her home state of Arizona to provide services there.

In Utah, where she currently practices, abortion is banned after 18 weeks. In Arizona, abortion is still allowed up to 24-26 weeks, until a pregnancy reaches “viability” (when a fetus is developed enough that it is able to survive outside the uterus with medical assistance). But new restrictions in Arizona may go into effect as early as September which would prohibit abortions after 15 weeks.

Despite the uncertain future of abortion access in Arizona, Robin still plans on moving there after her fellowship, but she hopes to travel to surrounding states to help provide abortion care where it’s less restricted. Even if she isn’t able to provide abortions at all, she says that there are still ways to help patients get safe, above-board abortions so as not to repeat the dangerous and often gruesome outcomes of self-induced abortions or those done by illegitimate practitioners before Roe.

“One of the roles that I think I can have as a physician is helping people with wraparound care for self-managed abortion,” says Robin. “If they can get the [abortion] pills online, then I can do the ultrasound beforehand, I can do the ultrasound after, I can talk them through it. I can help them with all the aspects of this care, I just can’t give them the pills myself.”

Whether a doctor can be penalized for “aiding and abetting” abortions that happen in different states remains an open question. In Texas, for example, Senate Bill 8 – which took effect Sept. 1, 2021 – not only established a fetal heartbeat law but added language that would allow private citizens to sue anyone who “knowingly engages in conduct that aids or abets the performance or inducement of an abortion” or anyone who even intends to do so.

That’s what happened to Alan Braid, MD, an ob.gyn. based in San Antonio. He confessed in a Washington Post op-ed that he had performed an abortion after cardiac activity had been detected in the pregnancy. Aware of the legal risks, he has since been sued by three people, and those cases are still underway.

But Ms. Ziegler says the chances of a doctor from a progressive state actually getting extradited and prosecuted by a state with restrictive abortion laws is pretty low – not zero, but low.

Like Robin, Natalie – an ob.gyn. in her early 30s – is a complex family planning fellow in Massachusetts. After her fellowship, she wants to return to Texas, where she completed her residency training.

“I’m at the point in my training where everyone starts looking for jobs and figuring out their next steps,” says Natalie. “The Dobbs decision introduced a ton of chaos due to the vagueness in the laws and how they get enforced, and then there’s chaos within institutions themselves and what kind of risk tolerance they have.”

Looking towards her future career path, Natalie says that she would not consider a job at an institution that didn’t allow her to teach abortion care to students, speak publicly about abortion rights, or let her travel outside of Texas to continue providing abortion care. She’s also preemptively seeking legal counsel and general guidance – advice that Ms. Ziegler strongly urges doctors to heed, sooner rather than later.

In states that have strict abortion bans with exceptions for life-threatening cases, there is still a lack of clarity around what is actually considered life-threatening enough to pass as an exception.

“Is it life-threatening in the next 6 hours? 24 hours? Seven days? One month?” Robin asks. “In medicine, we don’t necessarily talk about if something is life-threatening or not, we just say that there’s a high risk of X thing happening in X period of time. What’s the threshold at which that meets legal criteria? Nobody has an answer for that.”

Robin explains that, in her patients who have cancer, a pregnancy wouldn’t “necessarily kill them within the span of the next 9 months, but it could certainly accelerate their disease that could kill them within the next year or two.”

Right now, she says she doesn’t know what she would do if and when she is put in that position as a doctor.

“I didn’t go to medical school and become a doctor to become a felon,” says Robin. “Our goal is to make as many legal changes as we can to protect our patients and then practice as much harm reduction and as much care as we can within the letter of the law.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The names of the doctors in this story have been changed at their request because of fear of legal repercussions and/or professional retaliation.

When an Ohio ob.gyn. had a patient in need of an abortion in July 2022, he knew he had to move quickly.

Daniel, who also sees patients at an abortion clinic, was treating a woman who came in for an abortion around 5 weeks into her pregnancy. And after going through the mandatory waiting periods, the required ultrasounds at each appointment, the consent process, and the options counseling, she was set for a surgical abortion the following Monday.

But on Monday, pre-op tests showed that her blood pressure was very high, posing a serious health risk if Daniel proceeded with the surgery.

Before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June, Daniel would have sent the patient home with instructions on how to lower her blood pressure over time. But the patient now had just four days to show the necessary improvement.

In this case, everything worked out. The patient returned Thursday and was able to have the procedure. But this is just one of the many day-to-day medical decisions abortion providers are now having to make with the changing legal risks being as top-of-mind to doctors as the safety of their patients.

Daniel said he doesn’t want the Ohio abortion law to change the way he communicates with his patients. As far as he knows, it’s still legal to talk to patients about self-managed abortions, as long as everything is unbiased and clearly stated, he says.

“But I don’t think I would get a lot of institutional support to have those conversations with patients because of the perceived legal liability,” says Daniel. “I will still have those conversations, but I’m not going to tell my employer that I’m having them and I’m not going to document them in the chart.”

Daniel is aware that having these kinds of discussions, or entertaining the possibility of omitting certain information from patient records, runs the risk of legal and professional consequences. Enforcement of these rules is foggy, too.

Under the Ohio law, if a fellow staff member suspects you of violating a law, you could be reported to a supervisor or licensing body. Abortion providers are aware they must be cautious about what they say because anti-abortion activitists, posing as patients, have secretly recorded conversations in the past, Daniel says.

Enforcement: The past, present, and future legal risks

Before Roe, enforcement of illegal abortion was spotty, says Mary Ziegler, JD, a professor at Florida State University College of Law, who specializes in the legal history of reproductive rights. At the start of the late 19th century, the doctors who provided illegal abortions would, in most cases, be prosecuted if a patient died as a result of the procedure.

A doctor in Ashland, Pa., named Robert Spencer was known for providing abortions in the small mining town where he practiced in the 1920s. He was reportedly arrested three times – once after a patient died as a result of abortion complications – but was ultimately acquitted.

For many doctors performing abortions at the time, “it was very much a kind of roll of the dice,” Ms. Ziegler says. “There was a sense that these laws were not enforced very much.”

Carole Joffe, PhD, a sociologist with expertise in reproductive health, recalls that there were very few doctors arrested, given the sheer number of abortions that were performed. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists estimates that, in the years leading up to the original Roe decision, about 1.2 million women in the U.S. had illegal abortions – a number that exceeds today’s estimates.

Among the most notable cases of a doctor being detained was the arrest of gynecologist Jane Hodgson, MD, in 1970. Dr. Hodgson intentionally violated Minnesota law, which prohibited all abortions except in cases that were life-threatening to the patient.

After performing an abortion on a patient who had contracted rubella, also known as German measles, Dr. Hodgson was arrested, sentenced to 30 days in jail, and put on a year-long probation. She did not end up serving any time in jail, and her conviction was overturned after the Roe decision in 1973.

Now, the abortion restrictions being passed in many states have authorized much more sweeping penalties than those that existed in the pre-Roe era. According to Joffe, there is one key reason why we can anticipate more doctor arrests now.

“There simply was not the modern anti-abortion movement that we have come to know,” she says. “In the old days, there was not that much legal surveillance, and things were very unsafe. Fast forward to the present, we have much safer options now – like medication abortion pills – but we have a very different legal environment.”

Carmel Shachar, JD, MPH, a law and health policy expert at Harvard Law School, also expects that we will see more frequent prosecutions of doctors who provide abortion.