User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

CT Poses Risk for Malignant Hematopathies Among Children

More than a million European children undergo a CT scan each year. Ionizing radiation at moderate (> 100 mGy) to high (> 1 Gy) doses is a recognized risk factor for malignant hematopathies. The risk associated with exposure to low doses (< 100 mGy), typically delivered during a CT scan in children or adolescents, is unknown.

Previous studies assessed the risk for malignant hematopathies related to ionizing radiation from CT scans in young patients. Some showed an increased risk for leukemia with repeated scans, but confounding factors resulted in a lack of statistical power or biases in some cases. The EPI-CT study, coordinated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, aimed to evaluate the cancer risk among children and adolescents after exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation during CT scans.

A European Cohort

A recent article presents an assessment of observed malignant hematopathies following CT scan. The authors followed a multinational European cohort of 948,174 patients who had a CT scan before age 22 years. Ionizing radiation doses to the bone marrow were evaluated based on the scanned body region, patient characteristics, scan year, and the technical parameters of the machine. The analysis involved 876,771 patients who underwent 1,331,896 scans (an average of 1.52 per patient) and were followed for at least 2 years after the first scan.

In total, 790 malignant hematopathies were diagnosed, including 578 lymphoid hematopathies and 203 myeloid hematopathies and acute leukemias. The average follow-up period was 7.8 years. At the time of diagnosis, 51% of patients were under the age of 20 years, and 88.5% were under the age of 30 years. There was an association between cumulative dose and the observed malignant hematopathy, with an observed rate of 1.96 per 100 mGy (790 cases).

This rate corresponds to a 16% increased rate per scan (for a dose observed per scan of 8 mGy). A higher rate for any type of malignant hematopathy was observed for doses > 10 mGy, with an observed rate of 2.66 for doses > 50 mGy, compared with doses < 5 mGy.

The rate of malignant hematopathy increased with older age at the time of radiation exposure, particularly for lymphoid observations. The rate in the 5- to 9-year age group and the > 10-year age group was, respectively, two times and three to four times higher than that in the < 5-year age group. The rate decreased over time, with the highest observed rate between 2 and 5 years after ionizing radiation exposure and the lowest after 10 years.

CT Scans Must Be Warranted

This study, which involved nearly a million patients, has higher statistical power than previous studies, despite missing or approximate data (including that related to actually delivered doses). An association was shown between cumulative dose to the bone marrow and the risk of developing malignant hematopathy, both lymphoid and myeloid, with an increased risk even at low doses (10-15 mGy).

The results suggest that for every 10,000 children examined today (with a dose per scan of 8 mGy), 1-2 could develop a radiation-related malignant hematopathy in the next 12 years (1.4 cases). This study confirms the higher risk for cancer at low radiation doses and emphasizes the importance of justifying each pediatric CT scan and optimizing delivered doses. It is important to recall that an MRI or ultrasound can sometimes be an adequate substitute for a CT scan.

This article was translated from JIM , which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

More than a million European children undergo a CT scan each year. Ionizing radiation at moderate (> 100 mGy) to high (> 1 Gy) doses is a recognized risk factor for malignant hematopathies. The risk associated with exposure to low doses (< 100 mGy), typically delivered during a CT scan in children or adolescents, is unknown.

Previous studies assessed the risk for malignant hematopathies related to ionizing radiation from CT scans in young patients. Some showed an increased risk for leukemia with repeated scans, but confounding factors resulted in a lack of statistical power or biases in some cases. The EPI-CT study, coordinated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, aimed to evaluate the cancer risk among children and adolescents after exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation during CT scans.

A European Cohort

A recent article presents an assessment of observed malignant hematopathies following CT scan. The authors followed a multinational European cohort of 948,174 patients who had a CT scan before age 22 years. Ionizing radiation doses to the bone marrow were evaluated based on the scanned body region, patient characteristics, scan year, and the technical parameters of the machine. The analysis involved 876,771 patients who underwent 1,331,896 scans (an average of 1.52 per patient) and were followed for at least 2 years after the first scan.

In total, 790 malignant hematopathies were diagnosed, including 578 lymphoid hematopathies and 203 myeloid hematopathies and acute leukemias. The average follow-up period was 7.8 years. At the time of diagnosis, 51% of patients were under the age of 20 years, and 88.5% were under the age of 30 years. There was an association between cumulative dose and the observed malignant hematopathy, with an observed rate of 1.96 per 100 mGy (790 cases).

This rate corresponds to a 16% increased rate per scan (for a dose observed per scan of 8 mGy). A higher rate for any type of malignant hematopathy was observed for doses > 10 mGy, with an observed rate of 2.66 for doses > 50 mGy, compared with doses < 5 mGy.

The rate of malignant hematopathy increased with older age at the time of radiation exposure, particularly for lymphoid observations. The rate in the 5- to 9-year age group and the > 10-year age group was, respectively, two times and three to four times higher than that in the < 5-year age group. The rate decreased over time, with the highest observed rate between 2 and 5 years after ionizing radiation exposure and the lowest after 10 years.

CT Scans Must Be Warranted

This study, which involved nearly a million patients, has higher statistical power than previous studies, despite missing or approximate data (including that related to actually delivered doses). An association was shown between cumulative dose to the bone marrow and the risk of developing malignant hematopathy, both lymphoid and myeloid, with an increased risk even at low doses (10-15 mGy).

The results suggest that for every 10,000 children examined today (with a dose per scan of 8 mGy), 1-2 could develop a radiation-related malignant hematopathy in the next 12 years (1.4 cases). This study confirms the higher risk for cancer at low radiation doses and emphasizes the importance of justifying each pediatric CT scan and optimizing delivered doses. It is important to recall that an MRI or ultrasound can sometimes be an adequate substitute for a CT scan.

This article was translated from JIM , which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

More than a million European children undergo a CT scan each year. Ionizing radiation at moderate (> 100 mGy) to high (> 1 Gy) doses is a recognized risk factor for malignant hematopathies. The risk associated with exposure to low doses (< 100 mGy), typically delivered during a CT scan in children or adolescents, is unknown.

Previous studies assessed the risk for malignant hematopathies related to ionizing radiation from CT scans in young patients. Some showed an increased risk for leukemia with repeated scans, but confounding factors resulted in a lack of statistical power or biases in some cases. The EPI-CT study, coordinated by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, aimed to evaluate the cancer risk among children and adolescents after exposure to low doses of ionizing radiation during CT scans.

A European Cohort

A recent article presents an assessment of observed malignant hematopathies following CT scan. The authors followed a multinational European cohort of 948,174 patients who had a CT scan before age 22 years. Ionizing radiation doses to the bone marrow were evaluated based on the scanned body region, patient characteristics, scan year, and the technical parameters of the machine. The analysis involved 876,771 patients who underwent 1,331,896 scans (an average of 1.52 per patient) and were followed for at least 2 years after the first scan.

In total, 790 malignant hematopathies were diagnosed, including 578 lymphoid hematopathies and 203 myeloid hematopathies and acute leukemias. The average follow-up period was 7.8 years. At the time of diagnosis, 51% of patients were under the age of 20 years, and 88.5% were under the age of 30 years. There was an association between cumulative dose and the observed malignant hematopathy, with an observed rate of 1.96 per 100 mGy (790 cases).

This rate corresponds to a 16% increased rate per scan (for a dose observed per scan of 8 mGy). A higher rate for any type of malignant hematopathy was observed for doses > 10 mGy, with an observed rate of 2.66 for doses > 50 mGy, compared with doses < 5 mGy.

The rate of malignant hematopathy increased with older age at the time of radiation exposure, particularly for lymphoid observations. The rate in the 5- to 9-year age group and the > 10-year age group was, respectively, two times and three to four times higher than that in the < 5-year age group. The rate decreased over time, with the highest observed rate between 2 and 5 years after ionizing radiation exposure and the lowest after 10 years.

CT Scans Must Be Warranted

This study, which involved nearly a million patients, has higher statistical power than previous studies, despite missing or approximate data (including that related to actually delivered doses). An association was shown between cumulative dose to the bone marrow and the risk of developing malignant hematopathy, both lymphoid and myeloid, with an increased risk even at low doses (10-15 mGy).

The results suggest that for every 10,000 children examined today (with a dose per scan of 8 mGy), 1-2 could develop a radiation-related malignant hematopathy in the next 12 years (1.4 cases). This study confirms the higher risk for cancer at low radiation doses and emphasizes the importance of justifying each pediatric CT scan and optimizing delivered doses. It is important to recall that an MRI or ultrasound can sometimes be an adequate substitute for a CT scan.

This article was translated from JIM , which is part of the Medscape Professional Network. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com .

Doctors With Limited Vacation Have Increased Burnout Risk

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A recent study sheds light on the heightened risk for burnout among physicians who take infrequent vacations and engage in patient-related work during their time off.

Conducted by the American Medical Association (AMA), the study focuses on the United States, where labor regulations regarding vacation days and compensation differ from German norms. Despite this distinction, it provides valuable insights into the vacation behavior of doctors and its potential impact on burnout risk.

Christine A. Sinsky, MD, study author and senior physician advisor for physician satisfaction at the AMA, and her colleagues invited more than 90,000 physicians to participate in a survey that used postal and computer-based methods. In all, 3024 physicians, mainly those contacted by mail, filled out the questionnaire.

Limited Vacation Days

A significant proportion (59.6%) of respondents reported having taken fewer than 15 vacation days in the previous year, with nearly 20% taking fewer than 5 days off. Even when officially on vacation, most (70.4%) found themselves dealing with patient-related tasks. For one-third, these tasks consumed at least 30 minutes on a typical vacation day, often longer. This phenomenon was noted especially among female physicians.

Doctors who took less vacation and worked during their time off displayed higher emotional exhaustion and reported feeling less fulfilled in their profession.

Administrative Tasks

Administrative tasks, though no longer confined to paper, significantly influenced physicians’ vacation behavior. In the United States, handling messages from patients through the electronic health records (EHR) inbox demands a considerable amount of time.

Courses and tutorials on EHR inbox management are on the rise. A 2023 review linked electronic health records management to an increased burnout risk in the US medical community.

Lack of Coverage

Many physicians lack coverage for their EHR inbox during their absence. Less than half (49.1%) stated that someone else manages their inbox while they are on vacation.

Difficulty in finding coverage, whether for the EHR inbox or patient care, is a leading reason why many physicians seldom take more than 3 weeks of vacation per year. Financial considerations also contribute to this decision, as revealed in the survey.

Vacation Lowers Risk

Further analysis showed that doctors who took more than 3 weeks of vacation per year, which is not common, had a lower risk of developing burnout. Having coverage for vacation was also associated with reduced burnout risk and increased professional fulfillment.

However, these benefits applied only when physicians truly took a break during their vacation. Respondents who spent 30 minutes or more per day on patient-related work had a higher burnout risk. The risk was 1.58 times greater for 30-60 minutes, 1.97 times greater for 60-90 minutes, and 1.92 times greater for more than 90 minutes.

System-Level Interventions

The vacation behavior observed in this study likely exacerbates the effects of chronic workplace overload that are associated with long working hours, thus increasing the risk for burnout, according to the researchers.

“System-level measures must be implemented to ensure physicians take an appropriate number of vacation days,” wrote the researchers. “This includes having coverage available to handle clinical activities and administrative tasks, such as managing the EHR inbox. This could potentially reduce the burnout rate among physicians.”

This article was translated from the Medscape German edition. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Mental Health Screening May Benefit Youth With Obesity

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Mental health comorbidities are prevalent among youth with overweight or obesity, with the strongest risk factors being male sex, older age, and extreme obesity.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers compared clinical characteristics and outcomes among children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity with or without a comorbid mental disorder who participated in a lifestyle intervention program.

- Overall, data from 114,248 individuals (age, 6-30 years; 53% females) from 226 centers in Germany and Austria participating in the Adiposity Patient Registry were evaluated.

- Individuals were excluded if they had bariatric surgery or used weight-modifying drugs (metformin, orlistat, or glucagon-like peptide-1 analogues).

- Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as a standard deviation score (SDS) from a German youth population reference and was used to define overweight (90th to < 97th percentile), obesity (97th percentile), and severe obesity (≥ 99.5th percentile), which at age 18 correspond to adult cutoffs for overweight and obesity (25 kg/m2 and 30 kg/m2, respectively).

- Regression analysis identified the factors associated with mental disorders in those with overweight or obesity.

TAKEAWAY:

- A comorbid mental disorder was reported in 3969 individuals, with attention-deficit disorder (ADHD, 42.5%), anxiety (31.3%), depression (24.3%), and eating disorders (12.9%) being the most common.

- The factors most strongly associated with mental health comorbidity were male sex (odds ratio [OR], 1.39; 95% CI, 1.27-1.52), older age (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.25-1.62), and severe obesity (OR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.30-1.63).

- Mean BMI-SDS was higher in individuals with depression and eating disorders and lower in individuals with ADHD (both P < .001) than in those without mental disorders.

- Individuals with and without mental disorders benefited from similar BMI changes from lifestyle intervention programs.

IN PRACTICE:

The authors wrote, “Healthcare professionals caring for youth with overweight or obesity should be aware of comorbid mental disorders, and regular mental health screening should be considered.”

SOURCE:

This study, led by Angela Galler from the Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, was published online on January 9, 2024, in the International Journal of Obesity.

LIMITATIONS:

The study’s findings are based on data from a group of children, adolescents, and young adults with overweight or obesity treated in specialized obesity centers and may not be generalizable to all youth with obesity. Moreover, the study could not establish any conclusions regarding the cause or effect between obesity and mental disorders. Individuals were not tested psychologically for mental disorders and might have been underreported.

DISCLOSURES:

The manuscript is part of the Stratification of Obesity Phenotypes to Optimize Future Obesity Therapy project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Microbiome Impacts Vaccine Responses

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

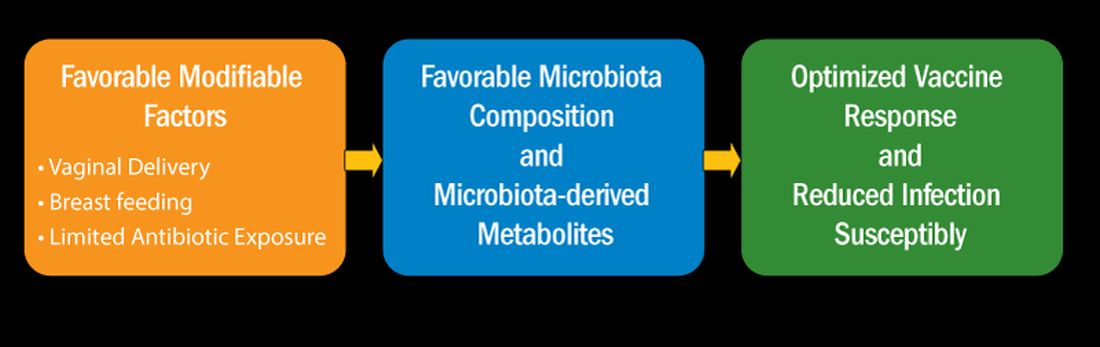

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

When infants are born, they have nearly a clean slate with regard to their immune systems. Virtually all their immune cells are naive. They have no immunity memory. Vaccines at birth, and in the first 2 years of life, elicit variable antibody levels and cellular immune responses. Sometimes, this leaves fully vaccinated children unprotected against vaccine-preventable infectious diseases.

Newborns are bombarded at birth with microbes and other antigenic stimuli from the environment; food in the form of breast milk, formula, water; and vaccines, such as hepatitis B and, in other countries, with BCG. At birth, to avoid immunologically-induced injury, immune responses favor immunologic tolerance. However, adaptation must be rapid to avoid life-threatening infections. To navigate the gauntlet of microbe and environmental exposures and vaccines, the neonatal immune system moves through a gradual maturation process toward immune responsivity. The maturation occurs at different rates in different children.

Reassessing Vaccine Responsiveness

Vaccine responsiveness is usually assessed by measuring antibody levels in blood. Until recently, it was thought to be “bad luck” when a child failed to develop protective immunity following vaccination. The bad luck was suggested to involve illness at the time of vaccination, especially illness occurring with fever, and especially common viral infections. But studies proved that notion incorrect. About 10 years ago I became more interested in variability in vaccine responses in the first 2 years of life. In 2016, my laboratory described a specific population of children with specific cellular immune deficiencies that we classified as low vaccine responders (LVRs).1 To preclude the suggestion that low vaccine responses were to be considered normal biological variation, we chose an a priori definition of LVR as those with sub-protective IgG antibody levels to four (≥ 66 %) of six tested vaccines in DTaP-Hib (diphtheria toxoid, tetanus toxoid, pertussis toxoid, pertactin, and filamentous hemagglutinin [DTaP] and Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide capsule [Hib]). Antibody levels were measured at 1 year of age following primary vaccinations at child age 2, 4, and 6 months old. The remaining 89% of children we termed normal vaccine responders (NVRs). We additionally tested antibody responses to viral protein and pneumococcal polysaccharide conjugated antigens (polio serotypes 1, 2, and 3, hepatitis B, and Streptococcus pneumoniae capsular polysaccharides serotypes 6B, 14, and 23F). Responses to these vaccine antigens were similar to the six vaccines (DTaP/Hib) used to define LVR. We and other groups have used alternative definitions of low vaccine responses that rely on statistics.

I recently reviewed the topic of the determinants of vaccine responses in early life, with a focus on the infant microbiome and metabolome: a.) cesarean section versus vaginal delivery, b.) breast versus formula feeding and c.) antibiotic exposure, that impact the immune response2 (Figure). In the review I also discussed how microbiome may serve as natural adjuvants for vaccine responses, how microbiota-derived metabolites influence vaccine responses, and how low vaccine responses in early life may be linked to increased infection susceptibility (Figure).

Cesarean section births occur in nearly 30% of newborns. Cesarean section birth has been associated with adverse effects on immune development, including predisposing to infections, allergies, and inflammatory disorders. The association of these adverse outcomes has been linked to lower total microbiome diversity. Fecal microbiome seeding from mother to infant in vaginal-delivered infants results in a more favorable and stable microbiome compared with cesarean-delivered infants. Nasopharyngeal microbiome may also be adversely affected by cesarean delivery. In turn, those microbiome differences can be linked to variation in vaccine responsiveness in infants.

Multiple studies strongly support the notion that breastfeeding has a favorable impact on immune development in early life associated with better vaccine responses, mediated by the microbiome. The mechanism of favorable immune responses to vaccines largely relates to the presence of a specific bacteria species, Bifidobacterium infantis. Breast milk contains human milk oligosaccharides that are not digestible by newborns. B. infantis is a strain of bacteria that utilizes these non-digestible oligosaccharides. Thereby, infants fed breast milk provides B. infantis the essential source of nutrition for its growth and predominance in the newborn gut. Studies have shown that Bifidobacterium spp. abundance in early life is correlated with better immune responses to multiple vaccines. Bifidobacterium spp. abundance has been positively correlated with antibody responses measured after 2 years, linking the microbiome composition to the durability of vaccine-induced immune responses.

Antibiotic exposure in early life may disproportionately damage the newborn and infant microbiome compared with later childhood. The average child receives about three antibiotic courses by the age of 2 years. My lab was among the first to describe the adverse effects of antibiotics on vaccine responses in early life.3 We found that broader spectrum antibiotics had a greater adverse effect on vaccine-induced antibody levels than narrower spectrum antibiotics. Ten-day versus five-day treatment courses had a greater negative effect. Multiple antibiotic courses over time (cumulative antibiotic exposure) was negatively associated with vaccine-induced antibody levels.

Over 11 % of live births worldwide occur preterm. Because bacterial infections are frequent complications of preterm birth, 79 % of very low birthweight and 87 % of extremely low birthweight infants in US NICUs receive antibiotics within 3 days of birth. Recently, my group studied full-term infants at birth and found that exposure to parenteral antibiotics at birth or during the first days of life had an adverse effect on vaccine responses.4

Microbiome Impacts Immunity

How does the microbiome affect immunity, and specifically vaccine responses? Microbial-derived metabolites affect host immunity. Gut bacteria produce short chain fatty acids (SCFAs: acetate, propionate, butyrate) [115]. SCFAs positively influence immunity cells. Vitamin D metabolites are generated by intestinal bacteria and those metabolites positively influence immunity. Secondary bile acids produced by Clostridium spp. are involved in favorable immune responses. Increased levels of phenylpyruvic acid produced by gut and/or nasopharyngeal microbiota correlate with reduced vaccine responses and upregulated metabolome genes that encode for oxidative phosphorylation correlate with increased vaccine responses.

In summary, immune development commences at birth. Impairment in responses to vaccination in children have been linked to disturbance in the microbiome. Cesarean section and absence of breastfeeding are associated with adverse microbiota composition. Antibiotics perturb healthy microbiota development. The microbiota affect immunity in several ways, among them are effects by metabolites generated by the commensals that inhabit the child host. A child who responds poorly to vaccines and has specific immune cell dysfunction caused by problems with the microbiome also displays increased infection proneness. But that is a story for another column, later.

Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases, Center for Infectious Diseases and Immunology, and director of the Research Institute, at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. He has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

1. Pichichero ME et al. J Infect Dis. 2016 Jun 15;213(12):2014-2019. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw053.

2. Pichichero ME. Cell Immunol. 2023 Nov-Dec:393-394:104777. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2023.104777.

3. Chapman TJ et al. Pediatrics. 2022 May 1;149(5):e2021052061. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052061.

4. Shaffer M et al. mSystems. 2023 Oct 26;8(5):e0066123. doi: 10.1128/msystems.00661-23.

Ibuprofen Fails for Patent Ductus Arteriosus in Preterm Infants

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

The study population included infants born between 23 weeks 0 days’ and 28 weeks 6 days’ gestation. The researchers randomized 326 extremely preterm infants with patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) at 72 hours or less after birth to ibuprofen at a loading dose of 10 mg/kg followed by two doses of 5 mg/kg at least 24 hours apart, and 327 to placebo.

The PDAs in the infants had a diameter of at least 1.5 mm with pulsatile flow.

Severe dysplasia outcome

The study’s primary outcome was a composite of death or moderate to severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age. Overall, a primary outcome occurred in 69.2% of infants who received ibuprofen and 63.5% of those who received a placebo.

Risk of death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age was not reduced by early ibuprofen vs. placebo for preterm infants, the researchers concluded. Moderate or severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia occurred in 64.2% of the infants in the ibuprofen group and 59.3% of the placebo group who survived to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

‘Unforeseeable’ serious adverse events

Forty-four deaths occurred in the ibuprofen group and 33 in the placebo group (adjusted risk ratio 1.09). Two “unforeseeable” serious adverse events occurred during the study that were potentially related to ibuprofen.

The lead author was Samir Gupta, MD, of Sidra Medicine, Doha, Qatar. The study was published online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Study limitations include incomplete data for some patients.

The study was supported by the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Programme. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

PCPs Increasingly Chained to EHRs

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’

Dr. Sinsky said the motivation for conducting the current study was that PCPs have reported an increase in their workload, especially EHR tasks outside of work (“pajama time”) since the onset of the pandemic.

The research followed up on a 2017 analysis from the same group and other findings showing an increase in the time physicians spend in EHR tasks and the number of Inbox messages they receive from patients seeking medical advice increased during the months following the start of the pandemic.

“As a busy practicing PCP with a large panel of patients, my sense was that the workload was increasing even more, which is what our study confirmed,” said Brian G. Arndt, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Heath at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, Wisconsin, who led the new study.

The researchers analyzed EHR usage of 141 academic PCPs practicing family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics, two thirds (66.7%) of whom were female. They compared the amount of time spent on EHR tasks during four timespans:

- May 2019 to February 2020

- June 2020 to March 2021

- May 2021 to March 2022

- April 2022 to March 2023

Each PCP’s time and Inbox message volume were calculated and then normalized over 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments.

Increased Time, Increased Burnout

The study found evidence PCPs have reduced their clinical hours in response to their growing digital workload.

“We have a serious shortage of primary care physicians,” Dr. Sinsky said. “When PCPs cut back their clinical [work] as a coping mechanism for an unmanageable workload, this further exacerbates the primary care shortage, reducing access to care for patients.”

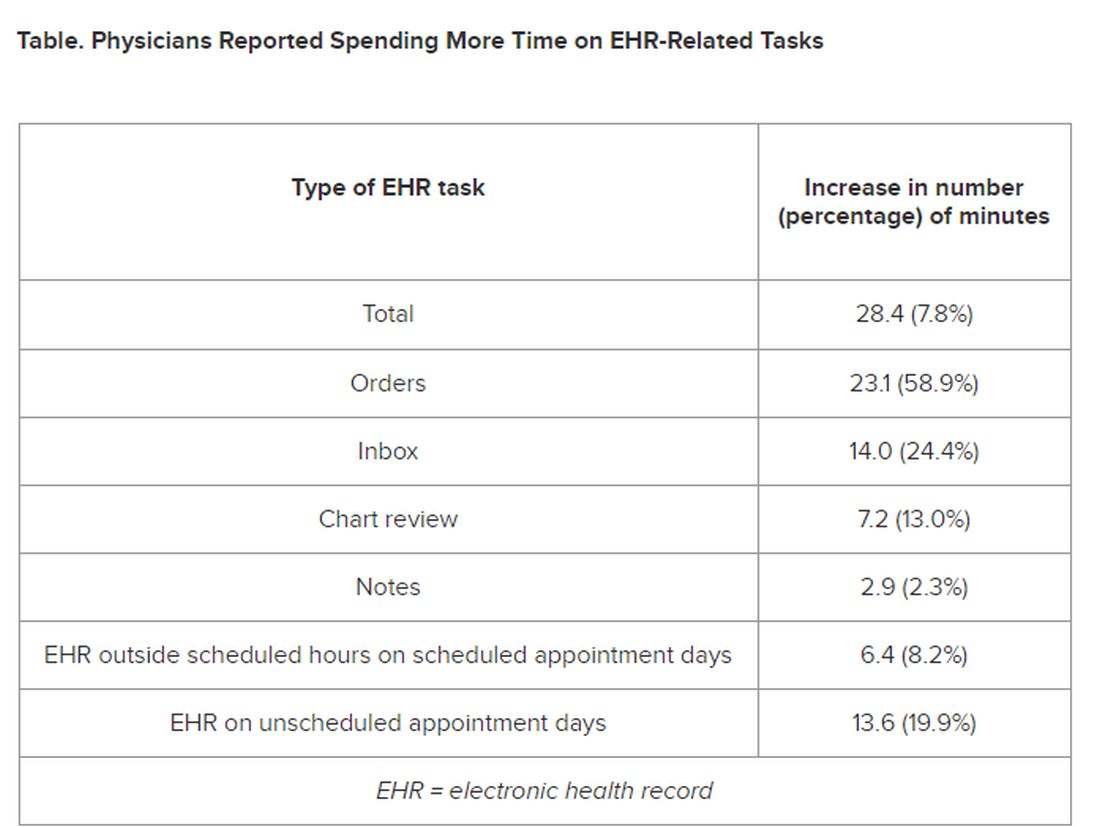

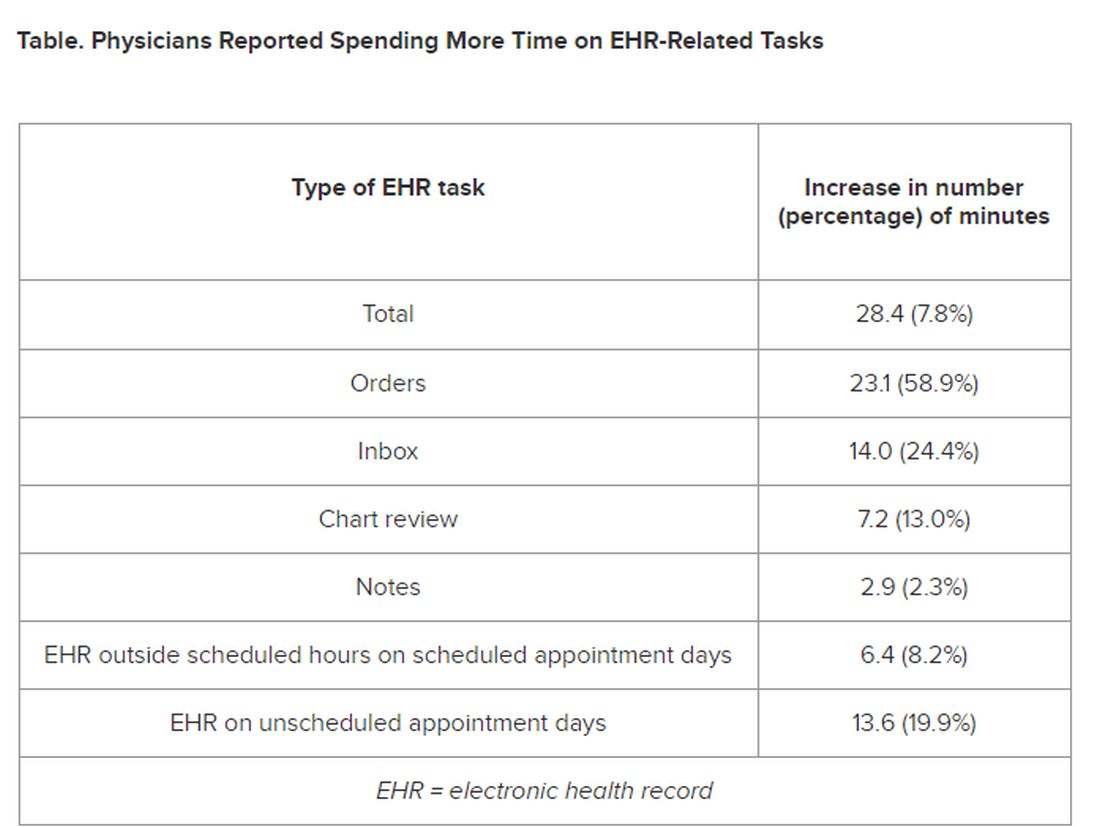

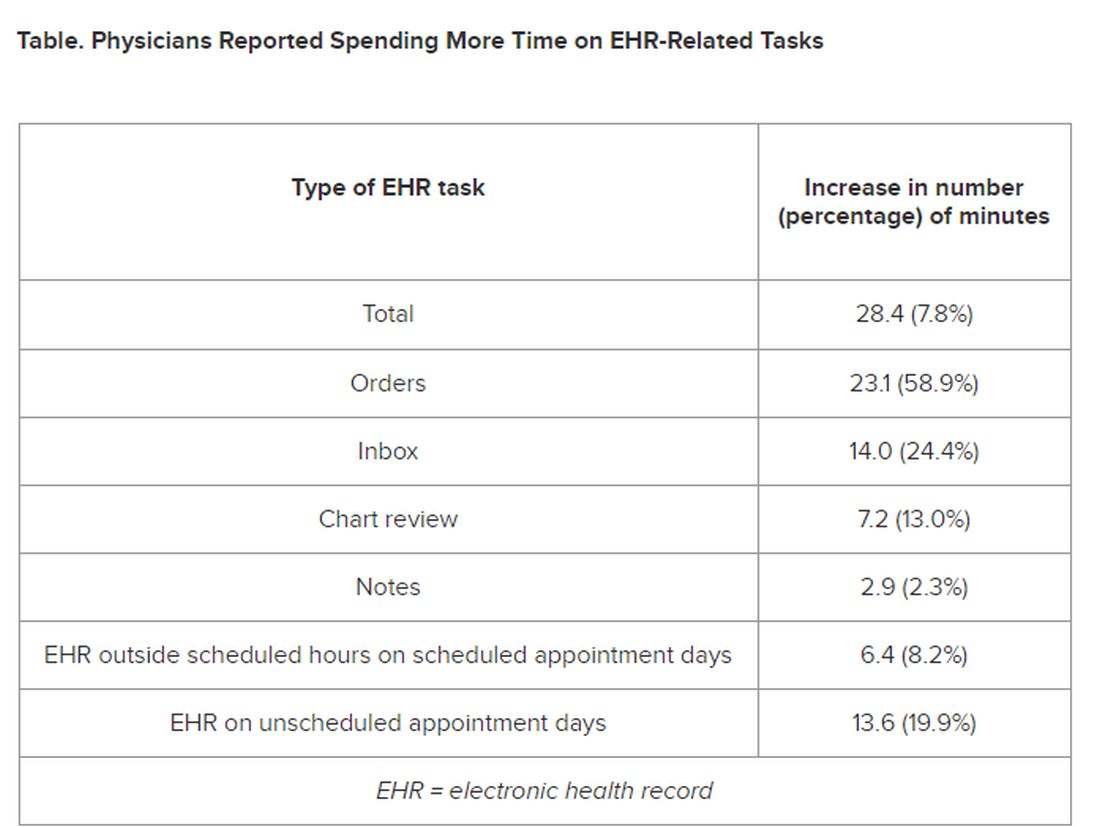

The researchers found increases from the first prepandemic period to the final period of their study in average time that PCPs spent at the EHR per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments (Table).

PCPs were inundated with several types of EHR-related responsibilities, including more medical advice requests (+55.5%) and more prescription messages (+19.5%) per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments. On the other hand, they had slightly fewer patient calls (−10.5%) and messages concerning test results (−2.7%).

A recent study of 307 PCPs across 31 primary care practices paralleled these findings. It found that physicians spent 36.2 minutes on the EHR per visit (interquartile range, 28.9-45.7 minutes). Included were 6.2 minutes of “pajama time” per visit and 7.8 minutes on the EHR per visit.

The amount of EHR time exceeded the amount of time allotted to a primary care visit (30 minutes). The authors commented that the EHR time burden “and the burnout associated with this burden represent a serious threat to the primary care physician workforce.”

“As more health systems across the country transition from fee-for-service to value-based payment arrangements, they need to balance the time PCPs and their care teams need for face-to-face care — in-person or video visits — with the increasing asynchronous care patients are seeking from us through the portal, for example, MyChart,” Dr. Arndt said.

Sinsky noted that when patients receive care from a PCP, quality is higher and costs are lower. “When access to primary care is further limited by virtue of physicians being overwhelmed by administrative work implemented via the EHR, so that they are reducing their hours, then we can expect negative consequences for patient care and costs of care.”

Tips for Reducing EHR Time

Arndt noted that some “brief investments” of time with patients “lead to high rates of return on decreased MyChart messaging.” For example, he has said to patients: “In the future, there’s no need to respond in MyChart with a ‘Thank you.’” Or “In the future, if you have questions from preappointment labs, no need to send me a separate message in MyChart prior to your visit since they’re typically just a few days out. I look closely at your labs and would always pick up the phone and call you if there was anything more urgent or pressing that needs more immediate action.”

Sinsky recommended two “high-yield opportunities” to reduce EHR-associated workload. The AMA offers a brief Inbox reduction checklist as well as a detailed toolkit to guide physicians and operational leaders in reducing the volume of unnecessary Inbox messages, she said.

Distribution of work among the team also can reduce the time physicians spent on order entry. “It doesn’t take a medical school education to enter orders for flu shots, lipid profiles, mammograms, and other tests, and yet we have primary care physicians around the country spending an hour or more per 8 hours of patient visits on this task,” she said.

‘Growing Mountain’

Sally Baxter, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and division chief for Ophthalmology Informatics and Data Sciences at University of California San Diego, said, “Studies like this ... are important for continuing to quantify the burden of EHR work and to evaluate potential interventions to reduce this burden and subsequent burnout.”

Baxter’s health system allows physicians to bill for asynchronous messaging when certain eligibility criteria are met. “This can deter frivolous messaging and also provide some compensation for the work involved,” she said.

“In addition, we’ve recently piloted using AI tools to help draft replies to patient messages in the EHR as another approach to tackling this important issue,” said Baxter, who wasn’t involved with the current study.

Eve Rittenberg, MD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a PCP at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fish Center for Women’s Health, in Boston, recommended that healthcare systems “monitor EHR workload across gender, specialty, and other variables to develop equitable support and compensation models.”

Dr. Rittenberg, who wasn’t involved with the current study, said healthcare systems should consider supporting physicians by blocking out time during clinic sessions to manage their EHR work. “Cross-coverage systems are vital so that on their days off, physicians can unplug from the computer and know that their patients’ needs are being met,” she added.

This work was supported in part by the AMA Practice Transformation Initiative: EHR-Use Metrics Research which provided grant funding to several of the authors. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. Dr. Arndt and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial information. Dr. Baxter received nonfinancial support from Optonmed and Topcon for research studies and collaborated with some of the study authors on other research but not this particular study. Dr. Rittenberg received internal funding from the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for a previous pilot project of inbasket cross-coverage. She had no relevant current disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’

Dr. Sinsky said the motivation for conducting the current study was that PCPs have reported an increase in their workload, especially EHR tasks outside of work (“pajama time”) since the onset of the pandemic.

The research followed up on a 2017 analysis from the same group and other findings showing an increase in the time physicians spend in EHR tasks and the number of Inbox messages they receive from patients seeking medical advice increased during the months following the start of the pandemic.

“As a busy practicing PCP with a large panel of patients, my sense was that the workload was increasing even more, which is what our study confirmed,” said Brian G. Arndt, MD, of the Department of Family Medicine and Community Heath at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, Wisconsin, who led the new study.

The researchers analyzed EHR usage of 141 academic PCPs practicing family medicine, internal medicine, and general pediatrics, two thirds (66.7%) of whom were female. They compared the amount of time spent on EHR tasks during four timespans:

- May 2019 to February 2020

- June 2020 to March 2021

- May 2021 to March 2022

- April 2022 to March 2023

Each PCP’s time and Inbox message volume were calculated and then normalized over 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments.

Increased Time, Increased Burnout

The study found evidence PCPs have reduced their clinical hours in response to their growing digital workload.

“We have a serious shortage of primary care physicians,” Dr. Sinsky said. “When PCPs cut back their clinical [work] as a coping mechanism for an unmanageable workload, this further exacerbates the primary care shortage, reducing access to care for patients.”

The researchers found increases from the first prepandemic period to the final period of their study in average time that PCPs spent at the EHR per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments (Table).

PCPs were inundated with several types of EHR-related responsibilities, including more medical advice requests (+55.5%) and more prescription messages (+19.5%) per 8 hours of scheduled clinic appointments. On the other hand, they had slightly fewer patient calls (−10.5%) and messages concerning test results (−2.7%).

A recent study of 307 PCPs across 31 primary care practices paralleled these findings. It found that physicians spent 36.2 minutes on the EHR per visit (interquartile range, 28.9-45.7 minutes). Included were 6.2 minutes of “pajama time” per visit and 7.8 minutes on the EHR per visit.

The amount of EHR time exceeded the amount of time allotted to a primary care visit (30 minutes). The authors commented that the EHR time burden “and the burnout associated with this burden represent a serious threat to the primary care physician workforce.”

“As more health systems across the country transition from fee-for-service to value-based payment arrangements, they need to balance the time PCPs and their care teams need for face-to-face care — in-person or video visits — with the increasing asynchronous care patients are seeking from us through the portal, for example, MyChart,” Dr. Arndt said.

Sinsky noted that when patients receive care from a PCP, quality is higher and costs are lower. “When access to primary care is further limited by virtue of physicians being overwhelmed by administrative work implemented via the EHR, so that they are reducing their hours, then we can expect negative consequences for patient care and costs of care.”

Tips for Reducing EHR Time

Arndt noted that some “brief investments” of time with patients “lead to high rates of return on decreased MyChart messaging.” For example, he has said to patients: “In the future, there’s no need to respond in MyChart with a ‘Thank you.’” Or “In the future, if you have questions from preappointment labs, no need to send me a separate message in MyChart prior to your visit since they’re typically just a few days out. I look closely at your labs and would always pick up the phone and call you if there was anything more urgent or pressing that needs more immediate action.”

Sinsky recommended two “high-yield opportunities” to reduce EHR-associated workload. The AMA offers a brief Inbox reduction checklist as well as a detailed toolkit to guide physicians and operational leaders in reducing the volume of unnecessary Inbox messages, she said.

Distribution of work among the team also can reduce the time physicians spent on order entry. “It doesn’t take a medical school education to enter orders for flu shots, lipid profiles, mammograms, and other tests, and yet we have primary care physicians around the country spending an hour or more per 8 hours of patient visits on this task,” she said.

‘Growing Mountain’

Sally Baxter, MD, assistant professor of ophthalmology and division chief for Ophthalmology Informatics and Data Sciences at University of California San Diego, said, “Studies like this ... are important for continuing to quantify the burden of EHR work and to evaluate potential interventions to reduce this burden and subsequent burnout.”

Baxter’s health system allows physicians to bill for asynchronous messaging when certain eligibility criteria are met. “This can deter frivolous messaging and also provide some compensation for the work involved,” she said.

“In addition, we’ve recently piloted using AI tools to help draft replies to patient messages in the EHR as another approach to tackling this important issue,” said Baxter, who wasn’t involved with the current study.

Eve Rittenberg, MD, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School and a PCP at Brigham and Women’s Hospital Fish Center for Women’s Health, in Boston, recommended that healthcare systems “monitor EHR workload across gender, specialty, and other variables to develop equitable support and compensation models.”

Dr. Rittenberg, who wasn’t involved with the current study, said healthcare systems should consider supporting physicians by blocking out time during clinic sessions to manage their EHR work. “Cross-coverage systems are vital so that on their days off, physicians can unplug from the computer and know that their patients’ needs are being met,” she added.

This work was supported in part by the AMA Practice Transformation Initiative: EHR-Use Metrics Research which provided grant funding to several of the authors. Sinsky is employed by the AMA. Dr. Arndt and coauthors disclosed no relevant financial information. Dr. Baxter received nonfinancial support from Optonmed and Topcon for research studies and collaborated with some of the study authors on other research but not this particular study. Dr. Rittenberg received internal funding from the Brigham Care Redesign Incubator and Startup Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, for a previous pilot project of inbasket cross-coverage. She had no relevant current disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

If you feel like the day doesn’t hold enough hours for you to get your work done, you’re right: (EHRs).

Investigators followed 141 academic PCPs between May 2019 and March 2023 and found they spent considerably more time engaging in EHR tasks during the final year of the study than in the prepandemic period. EHR time increased by over 8% on days with scheduled appointments and almost 20% on days without scheduled appointments.

“Physicians spend an unsustainable amount of time on EHR-based work, and that amount has increased steadily from 2019 to 2023,” Christine Sinsky, MD, vice president of professional satisfaction at the American Medical Association (AMA) and the senior author of the study, told this news organization. “It is imperative for healthcare systems to develop strategies to change the overall EHR workload trajectory to minimize PCPs’ occupational stress, including improved workflows, where the work is more appropriately distributed amongst the team.”

The study was published online on January 22, 2024, in the Annals of Family Medicine.

‘Pajama Time’