User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

10 devastating consequences of psychotic relapses

It breaks my heart every time young patients with functional disability and a history of several psychotic episodes are referred to me. It makes me wonder why they weren’t protected from a lifetime of disability with the use of one of the FDA-approved long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics right after discharge from their initial hospitalization for first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Two decades ago, psychiatric research discovered that psychotic episodes are neurotoxic and neurodegenerative, with grave consequences for the brain if they recur. Although many clinicians are aware of the high rate of nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia—which inevitably leads to a psychotic relapse—the vast majority (>99%, in my estimate) never prescribe an LAI after the FEP to guarantee full adherence and protect the patient’s brain from further atrophy due to relapses. The overall rate of LAI antipsychotic use is astonishingly low (approximately 10%), despite the neurologic malignancy of psychotic episodes. Further, LAIs are most often used after a patient has experienced multiple psychotic episodes, at which point the patient has already lost a significant amount of brain tissue and has already descended into a life of permanent disability.

Oral antipsychotics have the same efficacy as their LAI counterparts, and certainly should be used initially in the hospital during FEP to ascertain the absence of an allergic reaction after initial exposure, and to establish tolerability. Inpatient nurses are experts at making sure a reluctant patient actually swallows the pills and does not cheek them to spit them out later. So patients who have had FEP do improve with oral medications in the hospital, but all bets are off that those patients will regularly ingest tablets every day after discharge. Studies show patients have a high rate of nonadherence within days or weeks after leaving the hospital for FEP.1 This leads to repetitive psychotic relapses and rehospitalizations, with dire consequences for young patients with schizophrenia—a very serious brain disorder that had been labeled “the worst disease of mankind”2 in the era before studies showed LAI second-generation antipsychotics for FEP had remarkable rates of relapse prevention and recovery.3,4

Psychiatrists should approach FEP the same way oncologists approach cancer when it is diagnosed as Stage 1. Oncologists immediately take action to prevent the recurrence of the patient’s cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and do not wait for the cancer to advance to Stage 4, with widespread metastasis, before administering these potentially life-saving therapies (despite their toxic adverse effects). In schizophrenia, functional disability is the equivalent of Stage 4 cancer and should be aggressively prevented by using LAIs at the time of initial diagnosis, which is Stage 1 schizophrenia. Knowing the grave consequences of psychotic relapses, there is no logical reason whatsoever not to switch patients who have had FEP to an LAI before they are discharged from the hospital. A well-known study by a UCLA research group that compared patients who had FEP and were assigned to oral vs LAI antipsychotics at the time of discharge reported a stunning difference at the end of 1 year: a 650% higher relapse rate among the oral medication group compared with the LAI group!5 In light of such a massive difference, wouldn’t psychiatrists want to treat their sons or daughters with an LAI antipsychotic right after FEP? I certainly would, and I have always believed in treating every patient like a family member.

Catastrophic consequences

This lack of early intervention with LAI antipsychotics following FEP is the main reason schizophrenia is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes. Patients are prescribed pills that they often take erratically or not at all, and end up relapsing repeatedly, with multiple catastrophic consequences, such as:

1. Brain tissue loss. Until recently, psychiatry did not know that psychosis destroys gray and white matter in the brain and causes progressive brain atrophy with every psychotic relapse.6,7 The neurotoxicity of psychosis is attributed to 2 destructive processes: neuroinflammation8,9 and free radicals.10 Approximately 11 cc of brain tissue is lost during FEP and with every subsequent relapse.6 Simple math shows that after 3 to 5 relapses, patients’ brains will shrink by 35 cc to 60 cc. No wonder recurrent psychoses lead to a life of permanent disability. As I have said in a past editorial,11 just as cardiologists do everything they can to prevent a second myocardial infarction (“heart attack”), psychiatrists must do the same to prevent a second psychotic episode (“brain attack”).

2. Treatment resistance. With each psychotic episode, the low antipsychotic dose that worked well in FEP is no longer enough and must be increased. The neurodegenerative effects of psychosis implies that the brain structure changes with each episode. Higher and higher doses become necessary with every psychotic recurrence, and studies show that approximately 1 in 8 patients may stop responding altogether after a psychotic relapse.12

Continue to: Disability

3. Disability. Functional disability, both vocational and social, usually begins after the second psychotic episode, which is why it is so important to prevent the second episode.13 Patients usually must drop out of high school or college or quit the job they held before FEP. Most patients with multiple psychotic episodes will never be able to work, get married, have children, live independently, or develop a circle of friends. Disability in schizophrenia is essentially a functional death sentence.14

4. Incarceration and criminalization. So many of our patients with schizophrenia get arrested when they become psychotic and behave erratically due to delusions, hallucinations, or both. They typically are taken to jail instead of a hospital because almost all the state hospitals around the country have been closed. It is outrageous that a medical condition of the brain leads to criminalization of patients with schizophrenia.15 The only solution for this ongoing crisis of incarceration of our patients with schizophrenia is to prevent them from relapsing into psychosis. The so-called deinstitutionalization movement has mutated into trans-institutionalization, moving patients who are medically ill from state hospitals to more restrictive state prisons. Patients with schizophrenia should be surrounded by a mental health team, not by armed prison guards. The rate of recidivism among these individuals is extremely high because patients who are released often stop taking their medications and get re-arrested when their behavior deteriorates.

5. Suicide. The rate of suicide in the first year after FEP is astronomical. A recent study reported an unimaginably high suicide rate: 17,000% higher than that of the general population.16 Many patients with FEP commit suicide after they stop taking their antipsychotic medication, and often no antipsychotic medication is detected in their postmortem blood samples.

6. Homelessness. A disproportionate number of patients with schizophrenia become homeless.17 It started in the 1980s, when the shuttering of state hospitals began and patients with chronic illnesses were released into the community to fend for themselves. Many perished. Others became homeless, living on the streets of urban areas.

7. Early mortality. Schizophrenia has repeatedly been shown to be associated with early mortality, with a loss of approximately 25 potential years of life.17 This is attributed to lifestyle risk factors (eg, sedentary living, poor diet) and multiple medical comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, hypertension). To make things worse, patients with schizophrenia do not receive basic medical care to protect them from cardiovascular morbidity, an appalling disparity of care.18 Interestingly, a recent 7-year follow-up study of patients with schizophrenia found that the lowest rate of mortality from all causes was among patients receiving a second-generation LAI.19 Relapse prevention with LAIs can reduce mortality! According to that study, the worst mortality rate was observed in patients with schizophrenia who were not receiving any antipsychotic medication.

Continue to: Posttraumatic stress disorder

8. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many studies report that psychosis triggers PTSD symptoms20 because delusions and hallucinations can represent a life-threatening experience. The symptoms of PTSD get embedded within the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and every psychotic relapse serves as a “booster shot” for PTSD, leading to depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggressive behavior, and suicide.

9. Hopelessness, depression, and demoralization. The stigma of a severe psychiatric brain disorder such as schizophrenia, with multiple episodes, disability, incarceration, and homelessness, extends to the patients themselves, who become hopeless and demoralized by a chronic illness that marginalizes them into desperately ill individuals.21 The more psychotic episodes, the more intense the demoralization, hopelessness, and depression.

10. Family burden. The repercussions of psychotic relapses after FEP leads to significant financial and emotional stress on patients’ families.22 The heavy burden of caregiving among family members can be highly distressing, leading to depression and medical illness due to compromised immune functions.

Preventing relapse: It is not rocket science

It is obvious that the single most important therapeutic action for patients with schizophrenia is to prevent psychotic relapses. Even partial nonadherence must be prevented, because a drop of 25% in a patient’s serum antipsychotic level has been reported to lead to a psychotic relapse.23 Preventing relapse after FEP is not rocket science: Switch the patient to an LAI before discharge from the hospital,24 and provide the clinically necessary psychosocial treatments at every monthly follow-up visit (supportive psychotherapy, social skill training, vocational rehabilitation, and cognitive remediation). I have witnessed firsthand how stable and functional a patient who has had FEP can become when started on a second-generation LAI very soon after the onset of the illness.

I will finish with a simple question to my clinician readers: given the many devastating consequences of psychotic relapses, what would you do for your young patient with FEP? I hope you will treat them like a family member, and protect them from brain atrophy, disability, incarceration, homelessness, and suicide by starting them on an LAI antipsychotic before they leave the hospital. We must do no less for this highly vulnerable, young patient population.

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449-468.

2. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

3. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

4. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021:S2215-0366(21)00039-0. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0

5. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

6. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

7. Lei W, Kirkpatrick B, Wang Q, et al. Progressive brain structural changes after the first year of treatment in first-episode treatment-naive patients with deficit or nondeficit schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;288:12-20.

8. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;42:115-121.

9. Köhler-Forsberg O, Müller N, Lennox BR. Editorial: The role of inflammation in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:603296. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603296

10. Noto C, Ota VK, Gadelha A, et al. Oxidative stress in drug naïve first episode psychosis and antioxidant effects of risperidone. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:210-216.

11. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

12. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

13. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

14. Weye N, Santomauro DF, Agerbo E, et al. Register-based metrics of years lived with disability associated with mental and substance use disorders: a register-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):310-319.

15. Kirchebner J, Günther MP, Lau S. Identifying influential factors distinguishing recidivists among offender patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia via machine learning algorithms. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;315:110435. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110435

16. Zaheer J, Olfson M, Mallia E, et al. Predictors of suicide at time of diagnosis in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a 20-year total population study in Ontario, Canada. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:382-388.

17. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

18. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, et al. Linking posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis: a look at epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(10):675-681.

21. Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, et al. The role of demoralization and hopelessness in suicide risk in schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(5):200.

22. Khalil SA, Elbatrawy AN, Saleh NM, et al. The burden of care and burn out syndrome in caregivers of an Egyptian sample of schizophrenia patients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;10. doi: 10.1177/0020764021993155

23. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

24. Garner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: Rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33-45.

It breaks my heart every time young patients with functional disability and a history of several psychotic episodes are referred to me. It makes me wonder why they weren’t protected from a lifetime of disability with the use of one of the FDA-approved long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics right after discharge from their initial hospitalization for first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Two decades ago, psychiatric research discovered that psychotic episodes are neurotoxic and neurodegenerative, with grave consequences for the brain if they recur. Although many clinicians are aware of the high rate of nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia—which inevitably leads to a psychotic relapse—the vast majority (>99%, in my estimate) never prescribe an LAI after the FEP to guarantee full adherence and protect the patient’s brain from further atrophy due to relapses. The overall rate of LAI antipsychotic use is astonishingly low (approximately 10%), despite the neurologic malignancy of psychotic episodes. Further, LAIs are most often used after a patient has experienced multiple psychotic episodes, at which point the patient has already lost a significant amount of brain tissue and has already descended into a life of permanent disability.

Oral antipsychotics have the same efficacy as their LAI counterparts, and certainly should be used initially in the hospital during FEP to ascertain the absence of an allergic reaction after initial exposure, and to establish tolerability. Inpatient nurses are experts at making sure a reluctant patient actually swallows the pills and does not cheek them to spit them out later. So patients who have had FEP do improve with oral medications in the hospital, but all bets are off that those patients will regularly ingest tablets every day after discharge. Studies show patients have a high rate of nonadherence within days or weeks after leaving the hospital for FEP.1 This leads to repetitive psychotic relapses and rehospitalizations, with dire consequences for young patients with schizophrenia—a very serious brain disorder that had been labeled “the worst disease of mankind”2 in the era before studies showed LAI second-generation antipsychotics for FEP had remarkable rates of relapse prevention and recovery.3,4

Psychiatrists should approach FEP the same way oncologists approach cancer when it is diagnosed as Stage 1. Oncologists immediately take action to prevent the recurrence of the patient’s cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and do not wait for the cancer to advance to Stage 4, with widespread metastasis, before administering these potentially life-saving therapies (despite their toxic adverse effects). In schizophrenia, functional disability is the equivalent of Stage 4 cancer and should be aggressively prevented by using LAIs at the time of initial diagnosis, which is Stage 1 schizophrenia. Knowing the grave consequences of psychotic relapses, there is no logical reason whatsoever not to switch patients who have had FEP to an LAI before they are discharged from the hospital. A well-known study by a UCLA research group that compared patients who had FEP and were assigned to oral vs LAI antipsychotics at the time of discharge reported a stunning difference at the end of 1 year: a 650% higher relapse rate among the oral medication group compared with the LAI group!5 In light of such a massive difference, wouldn’t psychiatrists want to treat their sons or daughters with an LAI antipsychotic right after FEP? I certainly would, and I have always believed in treating every patient like a family member.

Catastrophic consequences

This lack of early intervention with LAI antipsychotics following FEP is the main reason schizophrenia is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes. Patients are prescribed pills that they often take erratically or not at all, and end up relapsing repeatedly, with multiple catastrophic consequences, such as:

1. Brain tissue loss. Until recently, psychiatry did not know that psychosis destroys gray and white matter in the brain and causes progressive brain atrophy with every psychotic relapse.6,7 The neurotoxicity of psychosis is attributed to 2 destructive processes: neuroinflammation8,9 and free radicals.10 Approximately 11 cc of brain tissue is lost during FEP and with every subsequent relapse.6 Simple math shows that after 3 to 5 relapses, patients’ brains will shrink by 35 cc to 60 cc. No wonder recurrent psychoses lead to a life of permanent disability. As I have said in a past editorial,11 just as cardiologists do everything they can to prevent a second myocardial infarction (“heart attack”), psychiatrists must do the same to prevent a second psychotic episode (“brain attack”).

2. Treatment resistance. With each psychotic episode, the low antipsychotic dose that worked well in FEP is no longer enough and must be increased. The neurodegenerative effects of psychosis implies that the brain structure changes with each episode. Higher and higher doses become necessary with every psychotic recurrence, and studies show that approximately 1 in 8 patients may stop responding altogether after a psychotic relapse.12

Continue to: Disability

3. Disability. Functional disability, both vocational and social, usually begins after the second psychotic episode, which is why it is so important to prevent the second episode.13 Patients usually must drop out of high school or college or quit the job they held before FEP. Most patients with multiple psychotic episodes will never be able to work, get married, have children, live independently, or develop a circle of friends. Disability in schizophrenia is essentially a functional death sentence.14

4. Incarceration and criminalization. So many of our patients with schizophrenia get arrested when they become psychotic and behave erratically due to delusions, hallucinations, or both. They typically are taken to jail instead of a hospital because almost all the state hospitals around the country have been closed. It is outrageous that a medical condition of the brain leads to criminalization of patients with schizophrenia.15 The only solution for this ongoing crisis of incarceration of our patients with schizophrenia is to prevent them from relapsing into psychosis. The so-called deinstitutionalization movement has mutated into trans-institutionalization, moving patients who are medically ill from state hospitals to more restrictive state prisons. Patients with schizophrenia should be surrounded by a mental health team, not by armed prison guards. The rate of recidivism among these individuals is extremely high because patients who are released often stop taking their medications and get re-arrested when their behavior deteriorates.

5. Suicide. The rate of suicide in the first year after FEP is astronomical. A recent study reported an unimaginably high suicide rate: 17,000% higher than that of the general population.16 Many patients with FEP commit suicide after they stop taking their antipsychotic medication, and often no antipsychotic medication is detected in their postmortem blood samples.

6. Homelessness. A disproportionate number of patients with schizophrenia become homeless.17 It started in the 1980s, when the shuttering of state hospitals began and patients with chronic illnesses were released into the community to fend for themselves. Many perished. Others became homeless, living on the streets of urban areas.

7. Early mortality. Schizophrenia has repeatedly been shown to be associated with early mortality, with a loss of approximately 25 potential years of life.17 This is attributed to lifestyle risk factors (eg, sedentary living, poor diet) and multiple medical comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, hypertension). To make things worse, patients with schizophrenia do not receive basic medical care to protect them from cardiovascular morbidity, an appalling disparity of care.18 Interestingly, a recent 7-year follow-up study of patients with schizophrenia found that the lowest rate of mortality from all causes was among patients receiving a second-generation LAI.19 Relapse prevention with LAIs can reduce mortality! According to that study, the worst mortality rate was observed in patients with schizophrenia who were not receiving any antipsychotic medication.

Continue to: Posttraumatic stress disorder

8. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many studies report that psychosis triggers PTSD symptoms20 because delusions and hallucinations can represent a life-threatening experience. The symptoms of PTSD get embedded within the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and every psychotic relapse serves as a “booster shot” for PTSD, leading to depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggressive behavior, and suicide.

9. Hopelessness, depression, and demoralization. The stigma of a severe psychiatric brain disorder such as schizophrenia, with multiple episodes, disability, incarceration, and homelessness, extends to the patients themselves, who become hopeless and demoralized by a chronic illness that marginalizes them into desperately ill individuals.21 The more psychotic episodes, the more intense the demoralization, hopelessness, and depression.

10. Family burden. The repercussions of psychotic relapses after FEP leads to significant financial and emotional stress on patients’ families.22 The heavy burden of caregiving among family members can be highly distressing, leading to depression and medical illness due to compromised immune functions.

Preventing relapse: It is not rocket science

It is obvious that the single most important therapeutic action for patients with schizophrenia is to prevent psychotic relapses. Even partial nonadherence must be prevented, because a drop of 25% in a patient’s serum antipsychotic level has been reported to lead to a psychotic relapse.23 Preventing relapse after FEP is not rocket science: Switch the patient to an LAI before discharge from the hospital,24 and provide the clinically necessary psychosocial treatments at every monthly follow-up visit (supportive psychotherapy, social skill training, vocational rehabilitation, and cognitive remediation). I have witnessed firsthand how stable and functional a patient who has had FEP can become when started on a second-generation LAI very soon after the onset of the illness.

I will finish with a simple question to my clinician readers: given the many devastating consequences of psychotic relapses, what would you do for your young patient with FEP? I hope you will treat them like a family member, and protect them from brain atrophy, disability, incarceration, homelessness, and suicide by starting them on an LAI antipsychotic before they leave the hospital. We must do no less for this highly vulnerable, young patient population.

It breaks my heart every time young patients with functional disability and a history of several psychotic episodes are referred to me. It makes me wonder why they weren’t protected from a lifetime of disability with the use of one of the FDA-approved long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics right after discharge from their initial hospitalization for first-episode psychosis (FEP).

Two decades ago, psychiatric research discovered that psychotic episodes are neurotoxic and neurodegenerative, with grave consequences for the brain if they recur. Although many clinicians are aware of the high rate of nonadherence in patients with schizophrenia—which inevitably leads to a psychotic relapse—the vast majority (>99%, in my estimate) never prescribe an LAI after the FEP to guarantee full adherence and protect the patient’s brain from further atrophy due to relapses. The overall rate of LAI antipsychotic use is astonishingly low (approximately 10%), despite the neurologic malignancy of psychotic episodes. Further, LAIs are most often used after a patient has experienced multiple psychotic episodes, at which point the patient has already lost a significant amount of brain tissue and has already descended into a life of permanent disability.

Oral antipsychotics have the same efficacy as their LAI counterparts, and certainly should be used initially in the hospital during FEP to ascertain the absence of an allergic reaction after initial exposure, and to establish tolerability. Inpatient nurses are experts at making sure a reluctant patient actually swallows the pills and does not cheek them to spit them out later. So patients who have had FEP do improve with oral medications in the hospital, but all bets are off that those patients will regularly ingest tablets every day after discharge. Studies show patients have a high rate of nonadherence within days or weeks after leaving the hospital for FEP.1 This leads to repetitive psychotic relapses and rehospitalizations, with dire consequences for young patients with schizophrenia—a very serious brain disorder that had been labeled “the worst disease of mankind”2 in the era before studies showed LAI second-generation antipsychotics for FEP had remarkable rates of relapse prevention and recovery.3,4

Psychiatrists should approach FEP the same way oncologists approach cancer when it is diagnosed as Stage 1. Oncologists immediately take action to prevent the recurrence of the patient’s cancer with chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, and do not wait for the cancer to advance to Stage 4, with widespread metastasis, before administering these potentially life-saving therapies (despite their toxic adverse effects). In schizophrenia, functional disability is the equivalent of Stage 4 cancer and should be aggressively prevented by using LAIs at the time of initial diagnosis, which is Stage 1 schizophrenia. Knowing the grave consequences of psychotic relapses, there is no logical reason whatsoever not to switch patients who have had FEP to an LAI before they are discharged from the hospital. A well-known study by a UCLA research group that compared patients who had FEP and were assigned to oral vs LAI antipsychotics at the time of discharge reported a stunning difference at the end of 1 year: a 650% higher relapse rate among the oral medication group compared with the LAI group!5 In light of such a massive difference, wouldn’t psychiatrists want to treat their sons or daughters with an LAI antipsychotic right after FEP? I certainly would, and I have always believed in treating every patient like a family member.

Catastrophic consequences

This lack of early intervention with LAI antipsychotics following FEP is the main reason schizophrenia is associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes. Patients are prescribed pills that they often take erratically or not at all, and end up relapsing repeatedly, with multiple catastrophic consequences, such as:

1. Brain tissue loss. Until recently, psychiatry did not know that psychosis destroys gray and white matter in the brain and causes progressive brain atrophy with every psychotic relapse.6,7 The neurotoxicity of psychosis is attributed to 2 destructive processes: neuroinflammation8,9 and free radicals.10 Approximately 11 cc of brain tissue is lost during FEP and with every subsequent relapse.6 Simple math shows that after 3 to 5 relapses, patients’ brains will shrink by 35 cc to 60 cc. No wonder recurrent psychoses lead to a life of permanent disability. As I have said in a past editorial,11 just as cardiologists do everything they can to prevent a second myocardial infarction (“heart attack”), psychiatrists must do the same to prevent a second psychotic episode (“brain attack”).

2. Treatment resistance. With each psychotic episode, the low antipsychotic dose that worked well in FEP is no longer enough and must be increased. The neurodegenerative effects of psychosis implies that the brain structure changes with each episode. Higher and higher doses become necessary with every psychotic recurrence, and studies show that approximately 1 in 8 patients may stop responding altogether after a psychotic relapse.12

Continue to: Disability

3. Disability. Functional disability, both vocational and social, usually begins after the second psychotic episode, which is why it is so important to prevent the second episode.13 Patients usually must drop out of high school or college or quit the job they held before FEP. Most patients with multiple psychotic episodes will never be able to work, get married, have children, live independently, or develop a circle of friends. Disability in schizophrenia is essentially a functional death sentence.14

4. Incarceration and criminalization. So many of our patients with schizophrenia get arrested when they become psychotic and behave erratically due to delusions, hallucinations, or both. They typically are taken to jail instead of a hospital because almost all the state hospitals around the country have been closed. It is outrageous that a medical condition of the brain leads to criminalization of patients with schizophrenia.15 The only solution for this ongoing crisis of incarceration of our patients with schizophrenia is to prevent them from relapsing into psychosis. The so-called deinstitutionalization movement has mutated into trans-institutionalization, moving patients who are medically ill from state hospitals to more restrictive state prisons. Patients with schizophrenia should be surrounded by a mental health team, not by armed prison guards. The rate of recidivism among these individuals is extremely high because patients who are released often stop taking their medications and get re-arrested when their behavior deteriorates.

5. Suicide. The rate of suicide in the first year after FEP is astronomical. A recent study reported an unimaginably high suicide rate: 17,000% higher than that of the general population.16 Many patients with FEP commit suicide after they stop taking their antipsychotic medication, and often no antipsychotic medication is detected in their postmortem blood samples.

6. Homelessness. A disproportionate number of patients with schizophrenia become homeless.17 It started in the 1980s, when the shuttering of state hospitals began and patients with chronic illnesses were released into the community to fend for themselves. Many perished. Others became homeless, living on the streets of urban areas.

7. Early mortality. Schizophrenia has repeatedly been shown to be associated with early mortality, with a loss of approximately 25 potential years of life.17 This is attributed to lifestyle risk factors (eg, sedentary living, poor diet) and multiple medical comorbidities (eg, obesity, diabetes, hypertension). To make things worse, patients with schizophrenia do not receive basic medical care to protect them from cardiovascular morbidity, an appalling disparity of care.18 Interestingly, a recent 7-year follow-up study of patients with schizophrenia found that the lowest rate of mortality from all causes was among patients receiving a second-generation LAI.19 Relapse prevention with LAIs can reduce mortality! According to that study, the worst mortality rate was observed in patients with schizophrenia who were not receiving any antipsychotic medication.

Continue to: Posttraumatic stress disorder

8. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Many studies report that psychosis triggers PTSD symptoms20 because delusions and hallucinations can represent a life-threatening experience. The symptoms of PTSD get embedded within the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and every psychotic relapse serves as a “booster shot” for PTSD, leading to depression, anxiety, personality changes, aggressive behavior, and suicide.

9. Hopelessness, depression, and demoralization. The stigma of a severe psychiatric brain disorder such as schizophrenia, with multiple episodes, disability, incarceration, and homelessness, extends to the patients themselves, who become hopeless and demoralized by a chronic illness that marginalizes them into desperately ill individuals.21 The more psychotic episodes, the more intense the demoralization, hopelessness, and depression.

10. Family burden. The repercussions of psychotic relapses after FEP leads to significant financial and emotional stress on patients’ families.22 The heavy burden of caregiving among family members can be highly distressing, leading to depression and medical illness due to compromised immune functions.

Preventing relapse: It is not rocket science

It is obvious that the single most important therapeutic action for patients with schizophrenia is to prevent psychotic relapses. Even partial nonadherence must be prevented, because a drop of 25% in a patient’s serum antipsychotic level has been reported to lead to a psychotic relapse.23 Preventing relapse after FEP is not rocket science: Switch the patient to an LAI before discharge from the hospital,24 and provide the clinically necessary psychosocial treatments at every monthly follow-up visit (supportive psychotherapy, social skill training, vocational rehabilitation, and cognitive remediation). I have witnessed firsthand how stable and functional a patient who has had FEP can become when started on a second-generation LAI very soon after the onset of the illness.

I will finish with a simple question to my clinician readers: given the many devastating consequences of psychotic relapses, what would you do for your young patient with FEP? I hope you will treat them like a family member, and protect them from brain atrophy, disability, incarceration, homelessness, and suicide by starting them on an LAI antipsychotic before they leave the hospital. We must do no less for this highly vulnerable, young patient population.

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449-468.

2. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

3. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

4. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021:S2215-0366(21)00039-0. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0

5. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

6. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

7. Lei W, Kirkpatrick B, Wang Q, et al. Progressive brain structural changes after the first year of treatment in first-episode treatment-naive patients with deficit or nondeficit schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;288:12-20.

8. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;42:115-121.

9. Köhler-Forsberg O, Müller N, Lennox BR. Editorial: The role of inflammation in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:603296. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603296

10. Noto C, Ota VK, Gadelha A, et al. Oxidative stress in drug naïve first episode psychosis and antioxidant effects of risperidone. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:210-216.

11. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

12. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

13. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

14. Weye N, Santomauro DF, Agerbo E, et al. Register-based metrics of years lived with disability associated with mental and substance use disorders: a register-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):310-319.

15. Kirchebner J, Günther MP, Lau S. Identifying influential factors distinguishing recidivists among offender patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia via machine learning algorithms. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;315:110435. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110435

16. Zaheer J, Olfson M, Mallia E, et al. Predictors of suicide at time of diagnosis in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a 20-year total population study in Ontario, Canada. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:382-388.

17. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

18. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, et al. Linking posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis: a look at epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(10):675-681.

21. Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, et al. The role of demoralization and hopelessness in suicide risk in schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(5):200.

22. Khalil SA, Elbatrawy AN, Saleh NM, et al. The burden of care and burn out syndrome in caregivers of an Egyptian sample of schizophrenia patients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;10. doi: 10.1177/0020764021993155

23. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

24. Garner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: Rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33-45.

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2017;11:449-468.

2. Where next with psychiatric illness? Nature. 1988;336(6195):95-96.

3. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Remission in patients with first-episode schizophrenia receiving assured antipsychotic medication: a study with risperidone long-acting injection. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(6):325-331.

4. Kishimoto T, Hagi K, Kurokawa S, et al. Long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics for the maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of randomised, cohort, and pre-post studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021:S2215-0366(21)00039-0. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00039-0

5. Subotnik KL, Casaus LR, Ventura J, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone for relapse prevention and control of breakthrough symptoms after a recent first episode of schizophrenia. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):822-829.

6. Cahn W, Hulshoff Pol HE, Lems EB, et al. Brain volume changes in first-episode schizophrenia: a 1-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(11):1002-1010.

7. Lei W, Kirkpatrick B, Wang Q, et al. Progressive brain structural changes after the first year of treatment in first-episode treatment-naive patients with deficit or nondeficit schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2019;288:12-20.

8. Monji A, Kato TA, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Neuroinflammation in schizophrenia especially focused on the role of microglia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;42:115-121.

9. Köhler-Forsberg O, Müller N, Lennox BR. Editorial: The role of inflammation in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:603296. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.603296

10. Noto C, Ota VK, Gadelha A, et al. Oxidative stress in drug naïve first episode psychosis and antioxidant effects of risperidone. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;68:210-216.

11. Nasrallah HA. For first-episode psychosis, psychiatrists should behave like cardiologists. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(8):4-7.

12. Emsley R, Oosthuizen P, Koen L, et al. Comparison of treatment response in second-episode versus first-episode schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):80-83.

13. Alvarez-Jiménez M, Parker AG, Hetrick SE, et al. Preventing the second episode: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial and pharmacological trials in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(3):619-630.

14. Weye N, Santomauro DF, Agerbo E, et al. Register-based metrics of years lived with disability associated with mental and substance use disorders: a register-based cohort study in Denmark. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(4):310-319.

15. Kirchebner J, Günther MP, Lau S. Identifying influential factors distinguishing recidivists among offender patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia via machine learning algorithms. Forensic Sci Int. 2020;315:110435. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110435

16. Zaheer J, Olfson M, Mallia E, et al. Predictors of suicide at time of diagnosis in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a 20-year total population study in Ontario, Canada. Schizophr Res. 2020;222:382-388.

17. Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3(2):A42.

18. Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1-3):15-22.

19. Taipale H, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Alexanderson K, et al. Antipsychotics and mortality in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:274-280.

20. Seedat S, Stein MB, Oosthuizen PP, et al. Linking posttraumatic stress disorder and psychosis: a look at epidemiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(10):675-681.

21. Berardelli I, Sarubbi S, Rogante E, et al. The role of demoralization and hopelessness in suicide risk in schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(5):200.

22. Khalil SA, Elbatrawy AN, Saleh NM, et al. The burden of care and burn out syndrome in caregivers of an Egyptian sample of schizophrenia patients. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;10. doi: 10.1177/0020764021993155

23. Subotnik KL, Nuechterlein KH, Ventura J, et al. Risperidone nonadherence and return of positive symptoms in the early course of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(3):286-292.

24. Garner KN, Nasrallah HA. Managing first-episode psychosis: Rationale and evidence for nonstandard first-line treatments for schizophrenia. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(7):33-45.

‘Canceling’ obsolete terms

I wanted to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his most important editorial, “Let’s ‘cancel’ these obsolete terms in DSM” (From the Editor,

Robert Barris, MD

Nassau University Medical Center

East Meadow, New York

How sad! This is my reaction to reading Dr. Nasrallah’s January 2021 editorial. Although biological psychiatry is synonymous with brain neurotransmitters and psychopharmacology, absent from this perspective is the visible biology of the human organism, specifically Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the psychosexual development of the infant and child and Wilhelm Reich’s discovery of characterological and muscular armor. Medicine, a natural science, is founded and grounded in observation. Psychiatry, having ignored and eliminated (“canceled”) recognition of these readily observable phenomena essential to understanding psychiatric disorders, including neurosis and schizophrenia, allows Dr. Nasrallah to suggest we “cancel” what should be at the heart of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Sadly, this heart has been lost for decades.

Howard Chavis, MD

New York, New York

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Psychiatry, like all medical and scientific disciplines, must go through an ongoing renewal, including the update of its terminology, with or without a change in its concepts or principles. Anxiety is a more accurate description of clinical symptoms than neurosis, and psychosis spectrum is more accurate than schizophrenia. Besides the accuracy issue, “neurotic” and “schizophrenic” have unfortunately devolved into pejorative and stigmatizing terms. The lexicon of psychiatry has gone through seismic changes over the past several decades, as I described in a previous editorial.1 Psychiatry is a vibrant, constantly evolving biopsychosocial/clinical neuroscience, not a static descriptive discipline.

Reference

1. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

I found myself having difficulty with Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about canceling “obsolete” terms. I agree that making a diagnosis of borderline or narcissistic personality disorder can be pejorative if the clinician is using it to manage their own unprocessed countertransference. While all behavior is brain-mediated, human behavior is influenced by psychological events great and small. I am concerned that you seem to be reducing personality trait disturbances to biological abnormality, pure and simple. Losing psychological understanding of patients while overexplaining behavior as pathological brain dysfunction risks losing why patients see us in the first place.

Michael Friedman, DO

Cherry Hill, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

The renaming I suggest goes beyond countertransference. It has to do with scientific validity of the diagnostic construct. And yes, personality traits are heavily genetic, but with some modulation by environmental factors. I suggest reading the seminal works of Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., PhD, and Kenneth S. Kendler, MD, on identical twins reared together or apart for more details about the genetics of personality traits.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I wanted to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his most important editorial, “Let’s ‘cancel’ these obsolete terms in DSM” (From the Editor,

Robert Barris, MD

Nassau University Medical Center

East Meadow, New York

How sad! This is my reaction to reading Dr. Nasrallah’s January 2021 editorial. Although biological psychiatry is synonymous with brain neurotransmitters and psychopharmacology, absent from this perspective is the visible biology of the human organism, specifically Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the psychosexual development of the infant and child and Wilhelm Reich’s discovery of characterological and muscular armor. Medicine, a natural science, is founded and grounded in observation. Psychiatry, having ignored and eliminated (“canceled”) recognition of these readily observable phenomena essential to understanding psychiatric disorders, including neurosis and schizophrenia, allows Dr. Nasrallah to suggest we “cancel” what should be at the heart of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Sadly, this heart has been lost for decades.

Howard Chavis, MD

New York, New York

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Psychiatry, like all medical and scientific disciplines, must go through an ongoing renewal, including the update of its terminology, with or without a change in its concepts or principles. Anxiety is a more accurate description of clinical symptoms than neurosis, and psychosis spectrum is more accurate than schizophrenia. Besides the accuracy issue, “neurotic” and “schizophrenic” have unfortunately devolved into pejorative and stigmatizing terms. The lexicon of psychiatry has gone through seismic changes over the past several decades, as I described in a previous editorial.1 Psychiatry is a vibrant, constantly evolving biopsychosocial/clinical neuroscience, not a static descriptive discipline.

Reference

1. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

I found myself having difficulty with Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about canceling “obsolete” terms. I agree that making a diagnosis of borderline or narcissistic personality disorder can be pejorative if the clinician is using it to manage their own unprocessed countertransference. While all behavior is brain-mediated, human behavior is influenced by psychological events great and small. I am concerned that you seem to be reducing personality trait disturbances to biological abnormality, pure and simple. Losing psychological understanding of patients while overexplaining behavior as pathological brain dysfunction risks losing why patients see us in the first place.

Michael Friedman, DO

Cherry Hill, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

The renaming I suggest goes beyond countertransference. It has to do with scientific validity of the diagnostic construct. And yes, personality traits are heavily genetic, but with some modulation by environmental factors. I suggest reading the seminal works of Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., PhD, and Kenneth S. Kendler, MD, on identical twins reared together or apart for more details about the genetics of personality traits.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

I wanted to thank Dr. Nasrallah for his most important editorial, “Let’s ‘cancel’ these obsolete terms in DSM” (From the Editor,

Robert Barris, MD

Nassau University Medical Center

East Meadow, New York

How sad! This is my reaction to reading Dr. Nasrallah’s January 2021 editorial. Although biological psychiatry is synonymous with brain neurotransmitters and psychopharmacology, absent from this perspective is the visible biology of the human organism, specifically Sigmund Freud’s discovery of the psychosexual development of the infant and child and Wilhelm Reich’s discovery of characterological and muscular armor. Medicine, a natural science, is founded and grounded in observation. Psychiatry, having ignored and eliminated (“canceled”) recognition of these readily observable phenomena essential to understanding psychiatric disorders, including neurosis and schizophrenia, allows Dr. Nasrallah to suggest we “cancel” what should be at the heart of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. Sadly, this heart has been lost for decades.

Howard Chavis, MD

New York, New York

Dr. Nasrallah responds

Psychiatry, like all medical and scientific disciplines, must go through an ongoing renewal, including the update of its terminology, with or without a change in its concepts or principles. Anxiety is a more accurate description of clinical symptoms than neurosis, and psychosis spectrum is more accurate than schizophrenia. Besides the accuracy issue, “neurotic” and “schizophrenic” have unfortunately devolved into pejorative and stigmatizing terms. The lexicon of psychiatry has gone through seismic changes over the past several decades, as I described in a previous editorial.1 Psychiatry is a vibrant, constantly evolving biopsychosocial/clinical neuroscience, not a static descriptive discipline.

Reference

1. Nasrallah HA. From bedlam to biomarkers: the transformation of psychiatry’s terminology reflects its 4 conceptual earthquakes. Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):5-7.

I found myself having difficulty with Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial about canceling “obsolete” terms. I agree that making a diagnosis of borderline or narcissistic personality disorder can be pejorative if the clinician is using it to manage their own unprocessed countertransference. While all behavior is brain-mediated, human behavior is influenced by psychological events great and small. I am concerned that you seem to be reducing personality trait disturbances to biological abnormality, pure and simple. Losing psychological understanding of patients while overexplaining behavior as pathological brain dysfunction risks losing why patients see us in the first place.

Michael Friedman, DO

Cherry Hill, New Jersey

Dr. Nasrallah responds

The renaming I suggest goes beyond countertransference. It has to do with scientific validity of the diagnostic construct. And yes, personality traits are heavily genetic, but with some modulation by environmental factors. I suggest reading the seminal works of Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., PhD, and Kenneth S. Kendler, MD, on identical twins reared together or apart for more details about the genetics of personality traits.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Bright light therapy for bipolar depression: A review of 6 studies

Depressive episodes are part of DSM-5 criteria for bipolar II disorder, and are also often experienced by patients with bipolar I disorder.1 Depressive episodes predominate the clinical course of bipolar disorder.2,3 Compared with manic and hypomanic episodes, bipolar depressive episodes have a stronger association with long-term morbidity, suicidal behavior, and impaired functioning.4,5 Approximately 20% to 60% of patients with bipolar disorder attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime, and 4% to 19% die by suicide. Compared with the general population, the risk of death by suicide is 10 to 30 times higher in patients with bipolar disorder.6

Treatment of bipolar depression is less investigated than treatment of unipolar depression or bipolar mania. The mainstays of treatment for bipolar depression include mood stabilizers (eg, lithium, valproic acid, or lamotrigine), second-generation antipsychotics (eg, risperidone, quetiapine, lurasidone, or olanzapine), adjunctive antidepressants (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or bupropion), and combinations of the above. While significant progress has been made in the treatment of mania, achieving remission for patients with bipolar depression remains a challenge. Anti-manic medications reduce depressive symptoms in only one-third of patients.7 Antidepressant monotherapy can induce hypomania and rapid cycling.8 Electroconvulsive therapy has also been used for treatment-resistant bipolar depression, but is usually reserved as a last resort.9

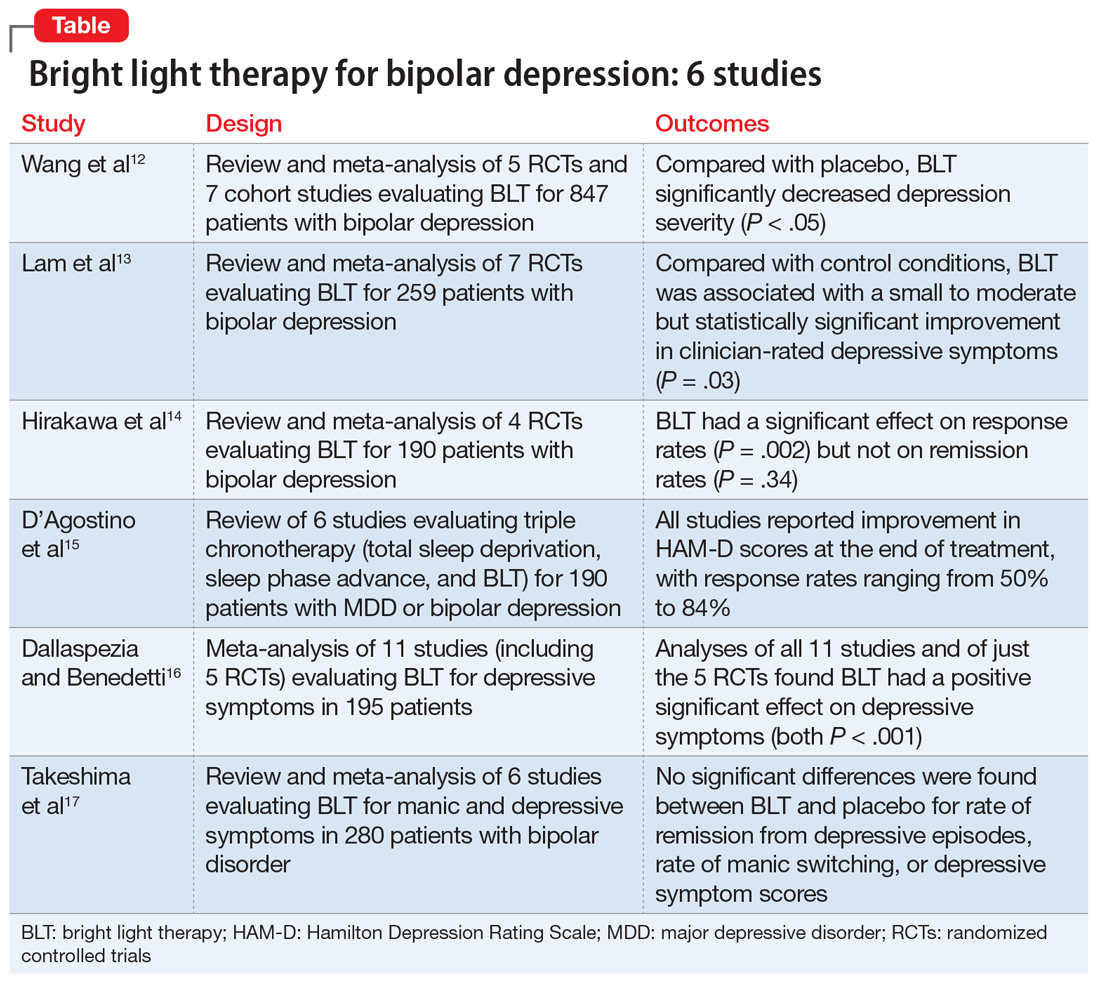

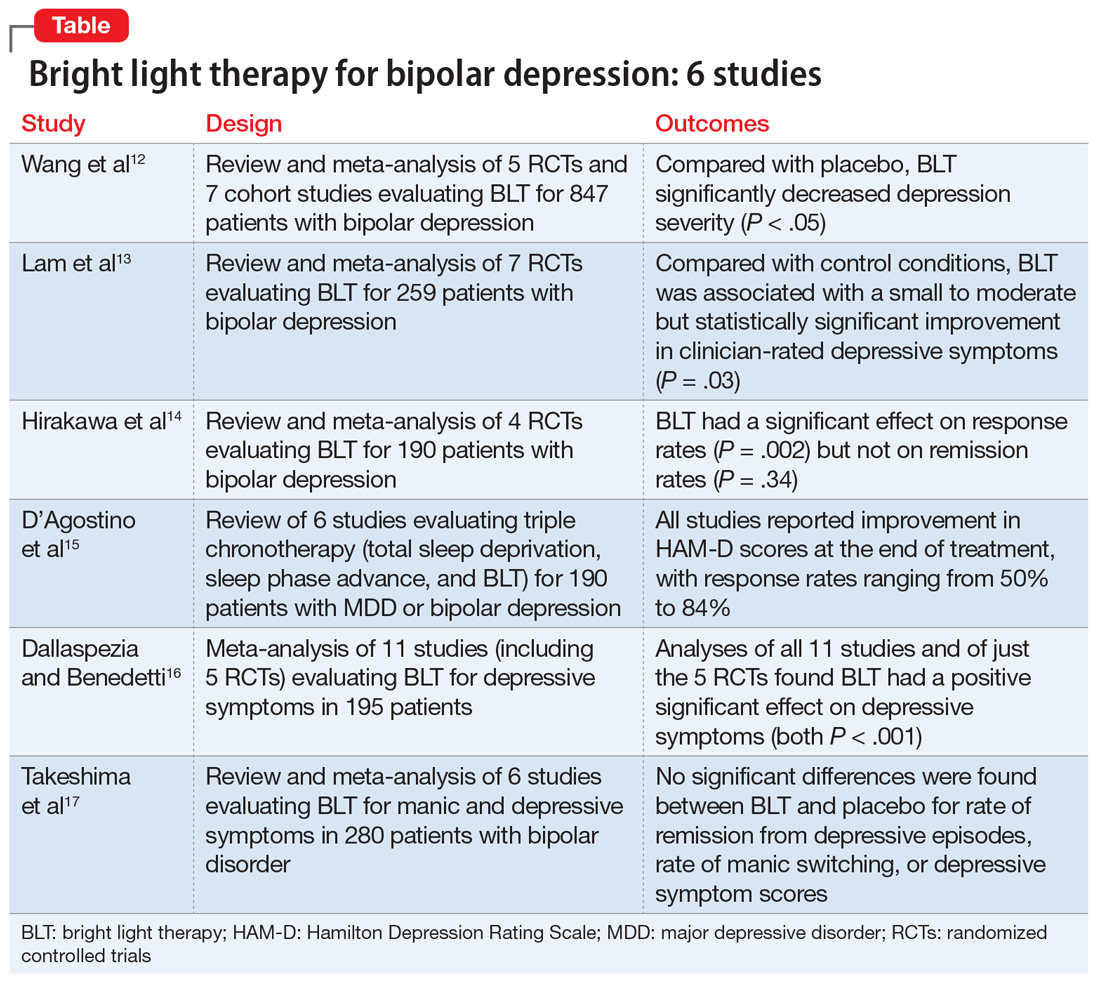

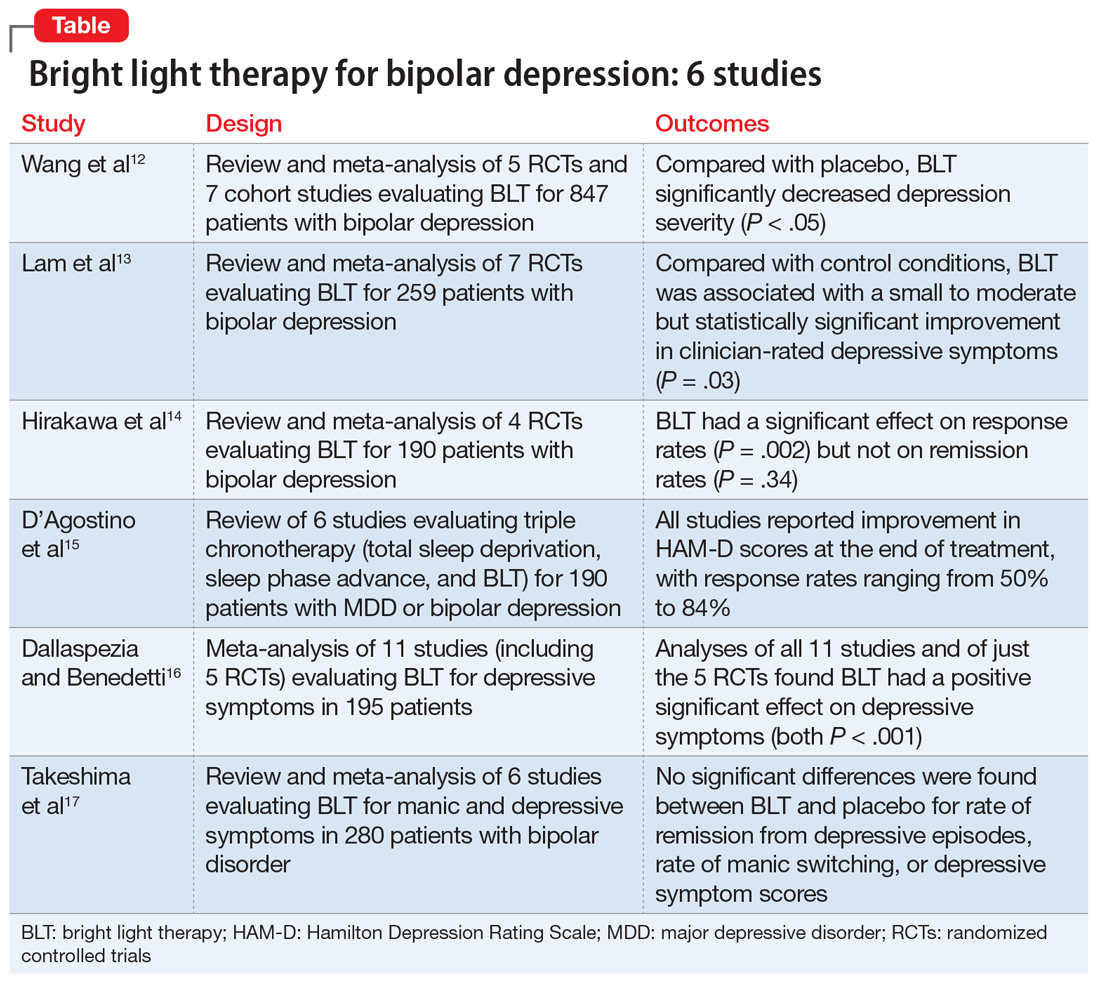

Research to investigate novel therapeutics for bipolar depression is a high priority. Patients with bipolar disorder are susceptible to environmental cues that alter circadian rhythms and trigger relapse. Recent studies have suggested that bright light therapy (BLT), an accepted treatment for seasonal depression, also may be useful for treating nonseasonal depression.10 Patients with bipolar depression frequently have delayed sleep phase and atypical depressive features (hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and lethargy), which predict response to light therapy.11 In this article, we review 6 recent studies that evaluated the efficacy and safety of BLT for treating bipolar depression (Table12-17).

1. Wang S, Zhang Z, Yao L, et al. Bright light therapy in treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232798

In this meta-analysis, Wang et al12 examined the role of BLT in treating bipolar depression. They also explored variables of BLT, including duration, timing, color, and color temperature, and how these factors may affect the severity of depressive symptoms.

Study design

- Two researchers conducted a systematic literature search on PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), as well as 4 Chinese databases from inception to March 2020. Search terms included “phototherapy,” “bright light therapy,” “bipolar disorder,” and “bipolar affective disorder.”

- Inclusion criteria called for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cohort studies that used a clearly defined diagnosis of bipolar depression. Five RCTs and 7 cohort studies with a total of 847 participants were included.

- The primary outcomes were depression severity, efficacy of duration/timing of BLT for depressive symptoms, and efficacy of different light color/color temperatures for depressive symptoms.

Outcomes

- As assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D); Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, Clinician Rating; or the Structured Interview Guide for the HAM-D, depression severity significantly decreased (P < .05) with BLT intensity ≥5,000 lux when compared with placebo.

- Subgroup analyses suggested that BLT can improve depression severity with or without adjuvant therapy. Duration of <10 hours and >10 hours with morning light vs morning plus evening light therapy all produced a significant decrease in depressive symptoms (P < .05).

- White light therapy also significantly decreased depression severity (P < .05). Color temperatures >4,500K and <4,500K both significantly decreased depression severity (P < .05).

- BLT (at various durations, timings, colors, and color temperatures) can reduce depression severity.

- This analysis only included studies that showed short-term improvements in depressive symptoms, which brings into question the long-term utility of BLT.

2. Lam RW, Teng MY, Jung YE, et al. Light therapy for patients with bipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(5):290-300.

Lam et al13 examined the role of BLT for patients with bipolar depression in a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- Investigators conducted a systematic review of RCTs of BLT for patients with bipolar depression. Articles were obtained from Web of Science, Embase, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, and Clinicaltrials.gov using the search terms “light therapy,” “phototherapy,” “light treatment,” and “bipolar.”

- Inclusion criteria required patients diagnosed with bipolar disorder currently experiencing a depressive episode, a clinician-rated measure of depressive symptomatology, a specific light intervention, and a randomized trial design with a control.

- A total of 7 RCTs with 259 participants were reviewed. The primary outcome was improvement in depressive symptoms based on the 17-item HAM-D.

Outcomes

- BLT was associated with a significant improvement in clinician-rated depressive symptoms (P = .03).

- Data for clinical response obtained from 6 trials showed a significant difference favoring BLT vs control (P = .024). Data for remission obtained from 5 trials showed no significant difference between BLT and control (P = .09).

- Compared with control, BLT was not associated with an increased risk of affective switches (P= .67).

Conclusion

- This study suggests a small to moderate but significant effect of BLT in reducing depressive symptoms.

- Study limitations included inconsistent light parameters, short follow-up time, small sample sizes, and the possibility that control conditions had treatment effects (eg, dim light as control vs no light).

3. Hirakawa H, Terao T, Muronaga M, et al. Adjunctive bright light therapy for treating bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav. 2020;10(12):ee01876. doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1876

Hirakawa et al14 assessed the role of adjunctive BLT for treating bipolar depression. Previous meta-analyses focused on case-control studies that assessed the effects of BLT and sleep deprivation therapy on depressive symptoms, but this meta-analysis reviewed RCTs that did not include sleep deprivation therapy.

Continue to: Study design

Study design

- Two authors searched Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, and Clinicaltrials.gov from inception to September 2019 using the terms “light therapy,” “phototherapy,” and “bipolar disorder.”

- Inclusion criteria called for RCTs, participants age ≥18, a diagnosis of bipolar disorder according to standard diagnostic criteria, evaluation by a standardized scale (HAM-D, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS], Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale with Atypical Depression Supplement [SIGH-ADS]), and light therapy as the experimental group intervention.

- The main outcomes were response rate (defined as ≥50% reduction in depression severity based on a standardized scale) and remission rate (defined as a reduction to 7 points on HAM-D, reduction to 9 points on MADRS, and score <8 on SIGH-ADS).

- Four RCTs with a total of 190 participants with bipolar depression were evaluated.

Outcomes

- BLT had a significant effect on response rate (P = .002).

- There was no significant effect of BLT on remission rates (P = .34).

- No studies reported serious adverse effects. Minor effects included headache (14.9% for BLT vs 12.5% for control), irritability (4.26% for BLT vs 2.08% for control), and sleep disturbance (2.13% for BLT vs 2.08% for control). The manic switch rate was 1.1% in BLT vs 1.2% in control.

Conclusion

- BLT is effective in reducing depressive symptoms in bipolar disorder, but does not affect remission rates.

- This meta-analysis was based on a small number of RCTs, and light therapy parameters were inconsistent across the studies. Furthermore, most patients were also being treated with mood-stabilizing or antidepressant medications.

- It is unclear if BLT is effective as monotherapy, rather than as adjunctive therapy.

4. D’Agostino A, Ferrara P, Terzoni S, et al. Efficacy of triple chronotherapy in unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review of available evidence. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:297-304.

Triple chronotherapy is the combination of total sleep deprivation, sleep phase advance, and BLT. D’Agostino et al15 reviewed all available evidence on the efficacy of triple chronotherapy interventions in treating symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar depression.

Study design

- Researchers conducted a systematic search on PubMed, Scopus, and Embase from inception to December 2019 using the terms “depression,” “sleep deprivation,” “chronotherapy,” and related words.

- The review included studies of all execution modalities, sequences of interventions, and types of control groups (eg, active control vs placebo). The population included participants of any age with MDD or bipolar depression.

- Two authors independently screened studies. Six articles published between 2009 and 2019 with a total of 190 patients were included.

Continue to: Outcomes

Outcomes

- All studies reported improvement in HAM-D scores at the end of treatment with triple chronotherapy, with response rates ranging from 50% to 84%.

- Most studies had a short follow-up period (up to 3 weeks). In these studies, response rates ranged from 58.3% to 61.5%. One study that had a 7-week follow-up also reported a statistically significant response rate in favor of triple chronotherapy.

- Remission rates, defined by different cut-offs depending on which version of the HAM-D was used, were evaluated in 5 studies. These rates ranged from 33.3% to 77%.

- Two studies that used the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale to assess the effect of triple chronotherapy on suicide risk reported a significant improvement in scores.

Conclusion

- Triple chronotherapy may be an effective and safe adjunctive treatment for depression. Some studies suggest that it also may play a role in remission from depression and reducing suicide risk.

5. Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F. Antidepressant light therapy for bipolar patients: a meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:943-948.

In a meta-analysis, Dallaspezia and Benedetti16 evaluated 11 studies to assess the role of BLT for treating depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder.

Study design

- Researchers searched literature published on PubMed with the terms “mood disorder,” “depression,” and “light therapy.”

- Eleven studies with a total of 195 participants were included. Five studies were RCTs.

- The primary outcome was severity of depression based on scores on the HAM-D, Beck Depression Inventory, or SIGH-ADS. Secondary outcomes were light intensity (measured in lux) and duration of treatment.

Outcomes

- Analysis of all 11 studies revealed a positive effect of BLT on depressive symptoms (P < .001).

- Analysis of just the 5 RCTs found a significant effect of BLT on depressive symptoms (P < .001).

- The switch rate due to BLT was lower than rates for patients being treated with antidepressant monotherapy (15% to 40%) or placebo (4.2%).

- Duration of treatment influenced treatment outcomes (P = .05); a longer duration resulted in the highest clinical effect. However, regardless of duration, BLT showed higher antidepressant effects than placebo.

- Higher light intensity was also found to show greater efficacy.

Continue to: Conclusion

Conclusion

- BLT is an effective adjunctive treatment for bipolar depression.

- Higher light intensity and longer duration of BLT may result in greater antidepressant effects, although the optimum duration and intensity are unknown.

- A significant limitation of this study was that the studies reviewed had high heterogeneity, and only a few were RCTs.

6. Takeshima M, Utsumi T, Aoki Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of bright light therapy for manic and depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(4):247-256.

Takeshima et al17 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy and safety of BLT for manic and depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder. They also evaluated if BLT could prevent recurrent mood episodes in patients with bipolar disorder.

Study design

- Researchers searched for studies of BLT for bipolar disorder in MEDLINE, CENTRAL, Embase, PsychInfo, and Clincialtrials.gov using the terms “bipolar disorder,” “phototherapy,” and “randomized controlled trial.”

- Two groups of 2 authors independently screened titles and abstracts for the following inclusion criteria: RCTs, 80% of patients diagnosed clinically with bipolar disorder, any type of light therapy, and control groups that included sham treatment or no light. Three groups of 2 authors then evaluated the quality of the studies and risk of bias.

- Six studies with a total of 280 participants were included.

- Primary outcome measures included rates of remission from depressive or manic episodes, rates of relapse from euthymic states, and changes in score on depression or mania rating scales.

Outcomes

- No significant differences were found between BLT and placebo for rates of remission from depressive episodes (P = .42), rates of manic switching (P = .26), or depressive symptom scores (P = .30).

- Sensitivity analysis for 3 studies with low overall indirectness revealed that BLT did have a significant antidepressant effect (P = .006).

- The most commonly reported adverse effects of BLT were headache (4.7%) and sleep disturbance (1.4%).

Conclusion

- This meta-analysis suggests that BLT does not have a significant antidepressant effect. However, a sensitivity analysis of studies with low overall indirectness showed that BLT does have a significant antidepressant effect.

- This review was based on a small number of RCTs that had inconsistent placebos (dim light, negative ion, no light, etc.) and varying parameters of BLT (light intensity, exposure duration, color of light), which may have contributed to the inconsistent results.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59(6):530-537.

3. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. A prospective investigation of the natural history of the long-term weekly symptomatic status of bipolar II disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):261-269.

4. Rihmer Z. S34.02 - Prediction and prevention of suicide in bipolar disorders. European Psychiatry. 2008;23(S2):S45-S45.

5. Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(8):1237-1245.

6. Dome P, Rihmer Z, Gonda X. Suicide risk in bipolar disorder: a brief review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2019;55(8):403.

7. Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Calabrese JR, et al. Effectiveness of adjunctive antidepressant treatment for bipolar depression. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(17):1711-1722.

8. Post RM, Altshuler LL, Leverich GS, et al. Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion, and sertraline. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:124-131.

9. Shah N, Grover S, Rao GP. Clinical practice guidelines for management of bipolar disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 2017;59(Suppl 1):S51-S66.

10. Penders TM, Stanciu CN, Schoemann AM, et al. Bright light therapy as augmentation of pharmacotherapy for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(5). doi: 10.4088/PCC.15r01906.

11. Terman M, Amira L, Terman JS, et al. Predictors of response and nonresponse to light treatment for winter depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(11):1423-1429.

12. Wang S, Zhang Z, Yao L, et al. Bright light therapy in treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232798

13. Lam RW, Teng MY, Jung YE, et al. Light therapy for patients with bipolar depression: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(5):290-300.

14. Hirakawa H, Terao T, Muronaga M, et al. Adjunctive bright light therapy for treating bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Brain Behav. 2020;10(12):ee01876. doi.org/10.1002/brb3.1876

15. D’Agostino A, Ferrara P, Terzoni S, et al. Efficacy of triple chronotherapy in unipolar and bipolar depression: a systematic review of available evidence. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:297-304.

16. Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F. Antidepressant light therapy for bipolar patients: a meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2020;274:943-948.

17. Takeshima M, Utsumi T, Aoki Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of bright light therapy for manic and depressive symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(4):247-256.

Depressive episodes are part of DSM-5 criteria for bipolar II disorder, and are also often experienced by patients with bipolar I disorder.1 Depressive episodes predominate the clinical course of bipolar disorder.2,3 Compared with manic and hypomanic episodes, bipolar depressive episodes have a stronger association with long-term morbidity, suicidal behavior, and impaired functioning.4,5 Approximately 20% to 60% of patients with bipolar disorder attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime, and 4% to 19% die by suicide. Compared with the general population, the risk of death by suicide is 10 to 30 times higher in patients with bipolar disorder.6

Treatment of bipolar depression is less investigated than treatment of unipolar depression or bipolar mania. The mainstays of treatment for bipolar depression include mood stabilizers (eg, lithium, valproic acid, or lamotrigine), second-generation antipsychotics (eg, risperidone, quetiapine, lurasidone, or olanzapine), adjunctive antidepressants (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or bupropion), and combinations of the above. While significant progress has been made in the treatment of mania, achieving remission for patients with bipolar depression remains a challenge. Anti-manic medications reduce depressive symptoms in only one-third of patients.7 Antidepressant monotherapy can induce hypomania and rapid cycling.8 Electroconvulsive therapy has also been used for treatment-resistant bipolar depression, but is usually reserved as a last resort.9

Research to investigate novel therapeutics for bipolar depression is a high priority. Patients with bipolar disorder are susceptible to environmental cues that alter circadian rhythms and trigger relapse. Recent studies have suggested that bright light therapy (BLT), an accepted treatment for seasonal depression, also may be useful for treating nonseasonal depression.10 Patients with bipolar depression frequently have delayed sleep phase and atypical depressive features (hypersomnia, hyperphagia, and lethargy), which predict response to light therapy.11 In this article, we review 6 recent studies that evaluated the efficacy and safety of BLT for treating bipolar depression (Table12-17).

1. Wang S, Zhang Z, Yao L, et al. Bright light therapy in treatment of patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(5):e0232798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232798