User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Asenapine transdermal system for schizophrenia

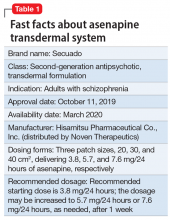

The asenapine transdermal system is available in 3 patch sizes: 20, 30, and 40 cm2, which deliver 3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours of asenapine, respectively.3 Based on the average exposure (area under the plasma concentration curve [AUC]) of asenapine, 3.8 mg/24 hours corresponds to 5 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine, and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to 10 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine.3 The “in-between” dose strength of 5.7 mg/24 hours would correspond to exposure to a total of 15 mg/d of sublingual asenapine. The recommended starting dose for asenapine transdermal system is 3.8 mg/24 hours. The dosage may be increased to 5.7 mg/24 hours or 7.6 mg/24 hours, as needed, after 1 week. The safety of doses above 7.6 mg/24 hours has not been evaluated in clinical studies. Asenapine transdermal system is applied once daily and should be worn for 24 hours only, with only 1 patch at any time. Application sites include the upper arm, upper back, abdomen, and hip. A different application site of clean, dry, intact skin should be selected each time a new patch is applied. Although showering is permitted, the use of asenapine transdermal system during swimming or taking a bath has not been evaluated. Of note, prolonged application of heat over an asenapine transdermal system increases plasma concentrations of asenapine, and thus application of external heat sources (eg, heating pads) over the patch should be avoided.

How it works

Product labeling notes that asenapine is an atypical antipsychotic, and that its efficacy in schizophrenia could be mediated through a combination of antagonist activity at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.3 The pharmacodynamic profile of asenapine is complex5 and receptor-binding assays performed using cloned human serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, and muscarinic receptors demonstrated picomolar affinity (extremely high) for 5-HT2C and 5-HT2A receptors, subnanomolar affinity (very high) for 5-HT7, 5-HT2B, 5-HT6, and D3 receptors, and nanomolar affinity (high) for D2 receptors, as well as histamine H1, D4, a1-adrenergic, a2-adrenergic, D1, 5-HT5, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and histamine H2 receptors. Activity of asenapine is that of antagonism at these receptors. Asenapine has no appreciable affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

The asenapine receptor-binding “fingerprint” differs from that of other antipsychotics. Some of these receptor affinities are of special interest in terms of potential efficacy for pro-cognitive effects and amelioration of abnormal mood.5,9 In terms of tolerability, a relative absence of affinity to muscarinic receptors would predict a low risk for anticholinergic adverse effects, but antagonism at histamine H1 and at a1-adrenergic receptors, either alone or in combination, may cause sedation, and blockade of H1 receptors would also predict weight gain.9 Antagonism of a1-adrenergic receptors can be associated with orthostatic hypotension and neurally mediated reflex bradycardia.9

Clinical pharmacokinetics

Three open-label, randomized, phase 1 studies were conducted to assess the relative bioavailability of asenapine transdermal system vs sublingual asenapine.10 These included single- and multiple-dose studies and clinical trials that examined the effects of different application sites and ethnic groups, and the effect of external heat on medication absorption. Studies were conducted in healthy individuals, except for the multiple-dose study, which was performed in adults with schizophrenia. The AUC for asenapine transdermal system was within the range of that of equivalent doses of sublingual asenapine, but peak exposure (maximum concentration) was significantly lower. As already noted, the AUC of the asenapine patch for 3.8 mg/24 hours and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to sublingual asenapine 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively. Maximum asenapine concentrations are typically reached between 12 and 24 hours, with sustained concentrations during the 24-hour wear time.3 On average, approximately 60% of the available asenapine is released from the transdermal system over 24 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations for asenapine transdermal system were achieved approximately 72 hours after the first application and, in contrast to sublingual asenapine, the peak-trough fluctuations were small (peak-to-trough ratio is 1.5 for asenapine transdermal system compared with >3 for sublingual asenapine). Dose-proportionality at steady state was evident for asenapine transdermal system. This is in contrast to sublingual asenapine, where exposure increases 1.7-fold with a 2-fold increase in dose.4,5 Following patch removal, the apparent elimination half-life is approximately 30 hours.3 The pharmacokinetics of the patch did not vary with regards to the application site (upper arm, upper back, abdomen, or hip area), and the pharmacokinetic profile was similar across the ethnic groups that participated in the study. Direct exposure to external heat did increase both the rate and extent of absorption, so external heat sources should be avoided.3

Efficacy

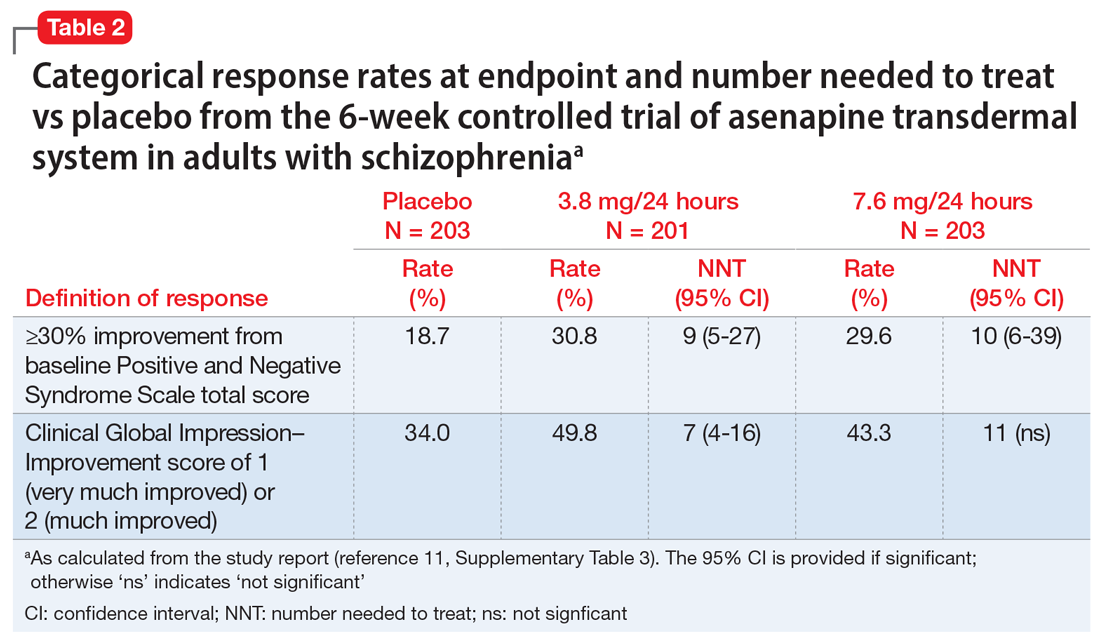

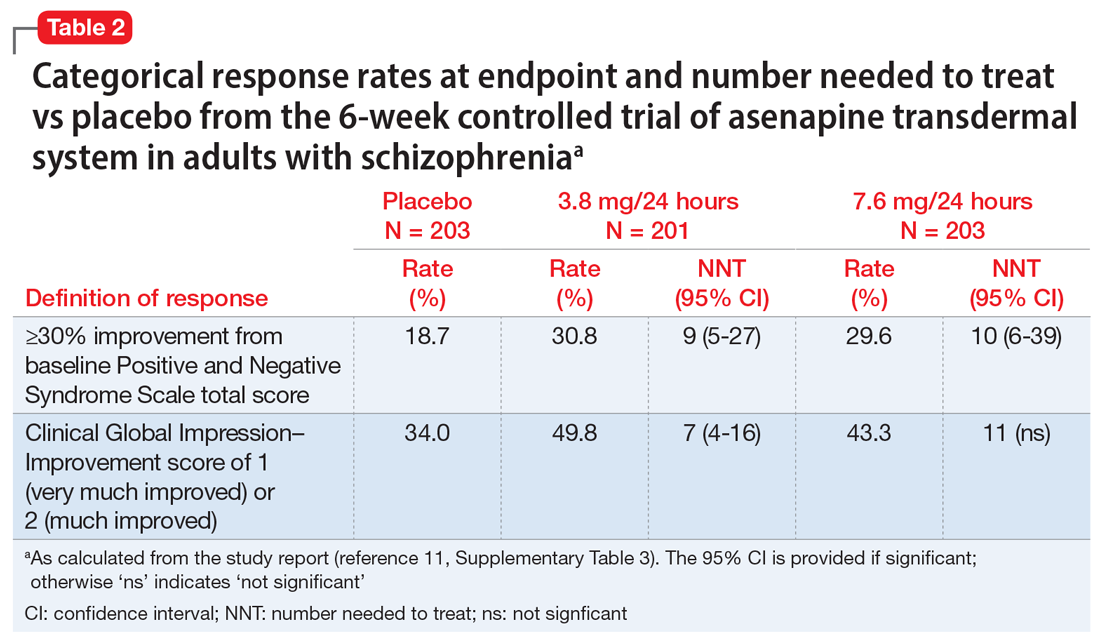

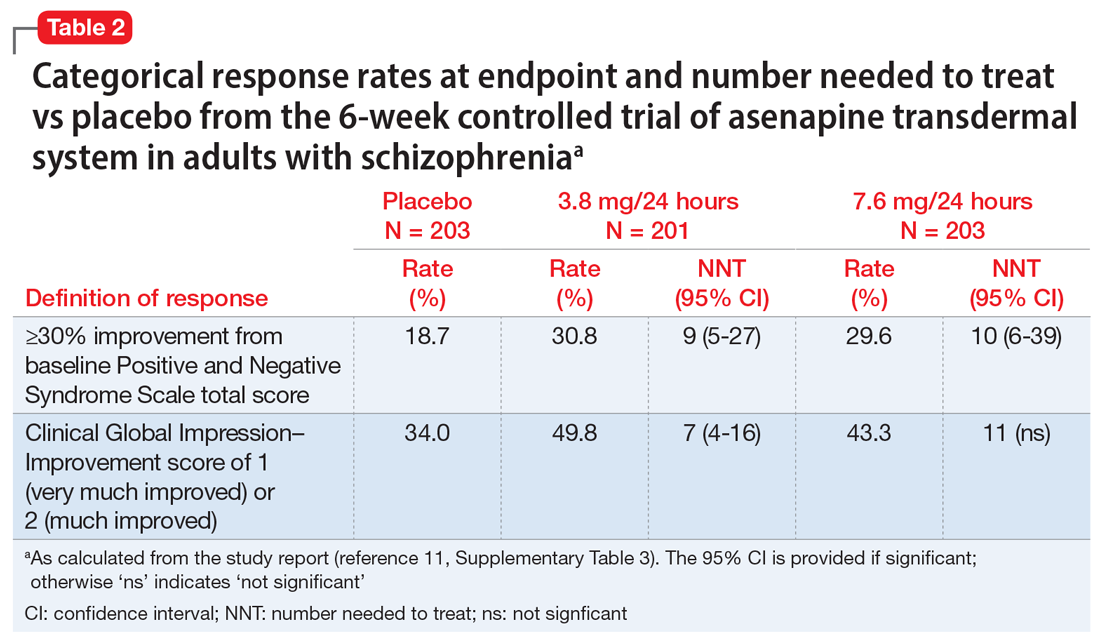

The efficacy profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to mirror that for sublingual asenapine.6,7 In addition to data supporting the use of asenapine as administered sublingually, a phase 3 study specifically assessed efficacy and safety of asenapine transdermal system in adults with schizophrenia.11,12 This study was conducted in the United States and 4 other countries at a total of 59 study sites, and 616 patients with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia were enrolled. After a 3- to 14-day screening/single-blind run-in washout period, participants entered a 6-week inpatient double-blind period. Randomization was 1:1:1 to asenapine transdermal system 3.8 mg/24 hours, 7.6 mg/24 hours, or a placebo patch. Each of the patch doses demonstrated significant improvement vs placebo at Week 6 for the primary (change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score) and key secondary (change in Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness) endpoints. Response at endpoint, as defined by a ≥30% improvement from baseline PANSS total score, or by a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), was also assessed. For either definition of response, both doses of asenapine transdermal system were superior to placebo, with number needed to treat (NNT) (Box) values <10 for the 3.8 mg/24 hours dose (Table 2). These effect sizes are similar to what is known about sublingual asenapine as determined in a meta-analysis performed by the manufacturer and using individual patient data.13

Box

Clinical trials produce a mountain of data that can be difficult to interpret and apply to clinical practice. When reading about studies, you may wonder:

- How large is the effect being measured?

- Is it clinically important?

- Are we reviewing a result that may be statistically significant but irrelevant for day-today patient care?

Number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH)—two tools of evidence-based medicine—can help answer these questions. NNT helps us gauge effect size or clinical significance. It is different from knowing if a clinical trial result is statistically significant. NNT allows us to place a number on how often we can expect to encounter a difference between two interventions. If we see a therapeutic difference once every 100 patients (NNT of 100), the difference between the treatments is not of great concern under most circumstances. But if a difference in outcome is seen once in every 7 patients being treated with an intervention vs another (NNT of 7), the result will likely influence dayto-day practice.

How to calculate NNT (or NNH):

What is the NNT for an outcome for drug A vs drug B?

fA = frequency of outcome for drug A

fB = frequency of outcome for drug B

NNT = 1/[ fA - fB]

By convention, we round up the NNT to the next higher whole number.

For example, let’s say drugs A and B are used to treat depression, and they result in 6-week response rates of 55% and 75%, respectively. The NNT to encounter a difference between drug B and drug A in terms of responders at 6 weeks can be calculated as follows:

- Difference in response rates: .75 -.55 = .20

- NNT: 1/.20 = 5

A rule of thumb: NNT values for a medication vs placebo <10 usually denote a medication we use on a regular basis to treat patients.

a Adapted from Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71. Citrome L. Can you interpret confidence intervals? It’s not that difficult. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):77-82. Additional information can be found in Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407-411 (free to access at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijcp.12142)

Overall tolerability and safety

The systemic safety and tolerability profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to be similar to that for sublingual asenapine, unless there are adverse events that are related to high peak plasma concentrations or large differences between peak and trough plasma concentrations.6 Nonsystemic local application site adverse events would, of course, differ between sublingual vs transdermal administration.

Continue to: Use of asenapine transdermal system...

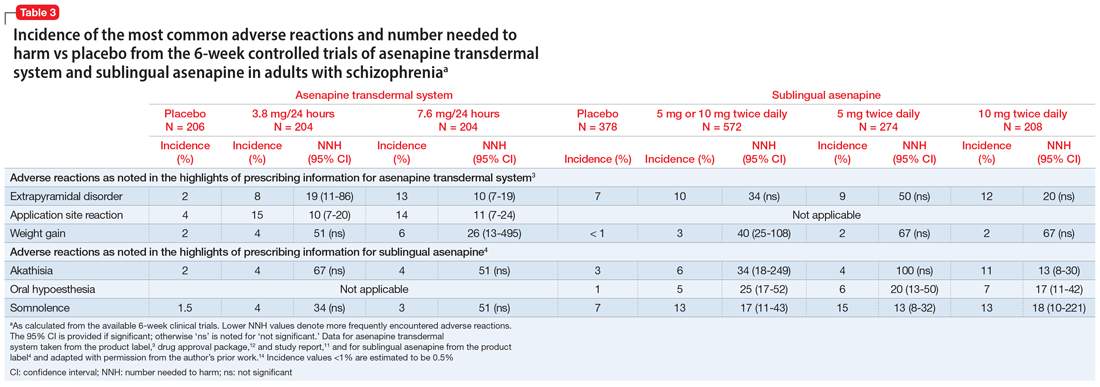

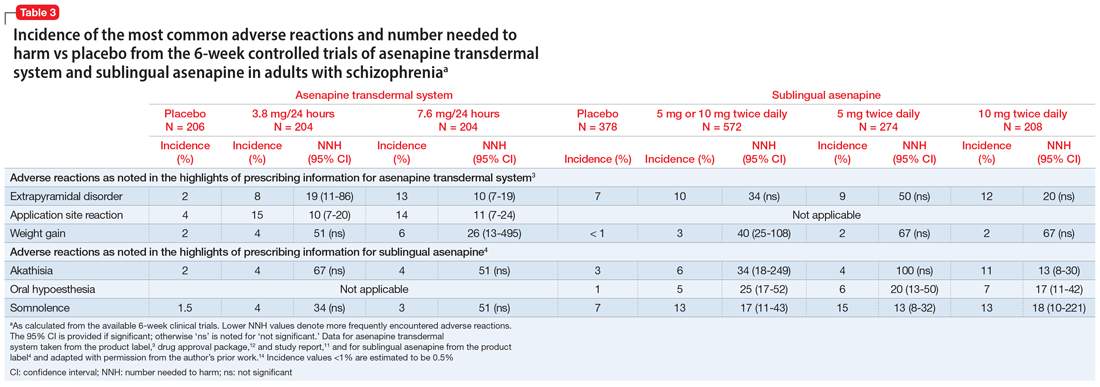

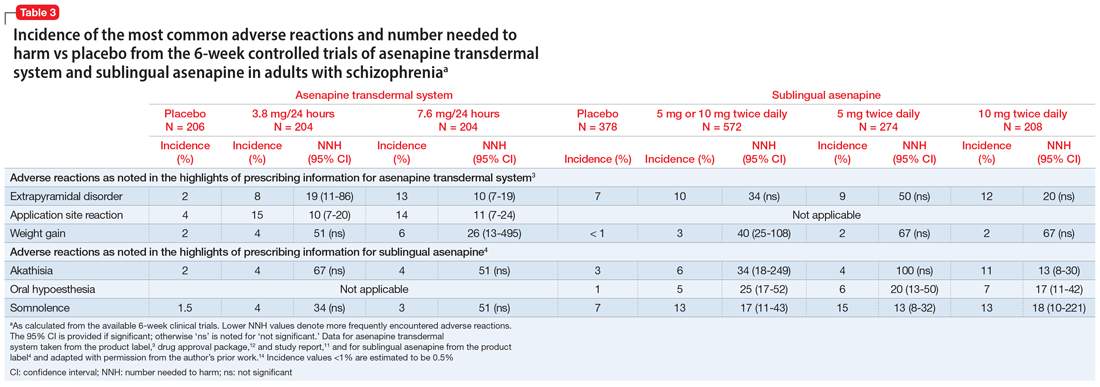

Use of asenapine transdermal system avoids the dysgeusia and oral hypoesthesia that can be observed with sublingual asenapine4,6; however, dermal effects need to be considered (see Dermal safety). The most commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice that for placebo) for asenapine transdermal system are extrapyramidal disorder, application site reaction, and weight gain.3 For sublingual asenapine for adults with schizophrenia, the list includes akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence.4 These adverse events can be further described using the metric of number needed to harm (NNH) as shown in Table 3.3,4,11,12,14 Of note, extrapyramidal disorder and weight gain appear to be dose-related for asenapine transdermal system. Akathisia appears to be dose-related for sublingual asenapine but not for asenapine transdermal system. Somnolence appears to be associated with sublingual asenapine but not necessarily with asenapine transdermal system.

For sublingual asenapine, the additional indications (bipolar I disorder as acute monotherapy treatment of manic or mixed episodes in adults and pediatric patients age 10 to 17, adjunctive treatment to lithium or valproate in adults, and maintenance monotherapy treatment in adults) have varying commonly encountered adverse reactions.4 Both transdermal asenapine system and sublingual asenapine are contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh C) and those with known hypersensitivity to asenapine or to any components in the formulation. Both formulations carry similar warnings in their prescribing information regarding increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, cerebrovascular adverse reactions in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, metabolic changes, orthostatic hypotension, leukopenia (and neutropenia and agranulocytosis), QT prolongation, seizures, and potential for cognitive and motor impairment.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment in the asenapine transdermal system pivotal trial occurred in 4.9%, 7.8%, and 6.8% of participants in the 3.8 mg/24 hour, 7.6 mg/24 hour, and placebo groups, respectively.11

Dermal safety

In the pivotal efficacy study,11 the incidence of adverse events at patch application sites was higher in the active groups vs placebo (Table 33,4,11,12,14). The most frequently reported patch application site reactions were erythema and pruritus, occurring in approximately 10% and 4% in the active treatment arms vs 1.5% and 1.9% for placebo, respectively. With the exception of 1 adverse event of severe application site erythema during Week 2 (participant received 7.6 mg/24 hour, erythema resolved without intervention, and the patient continued the study), all other patch application site events were mild or moderate in severity. Rates of discontinuation due to application site reactions or skin disorders were ≤0.5% across all groups. In the pharmacokinetic studies,10 no patches were removed because of unacceptable irritation.

Why Rx?

Asenapine transdermal system is the first antipsychotic “patch” FDA-approved for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. Asenapine has been available since 2009 as a sublingual formulation administered twice daily. The pharmacokinetic profile of the once-daily transdermal system demonstrates dose-proportional kinetics and sustained delivery of asenapine with a low peak-to-trough plasma level ratio. Three dosage strengths (3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours) are available, corresponding to blood levels attained with sublingual asenapine exposures of 10, 15, and 20 mg/d, respectively. Application sites are rotated daily and include the upper arms, upper back, abdomen, or hip. Dysgeusia and hypoesthesia of the tongue are avoided with the use of the patch, and there are no food or drink restrictions. Attention will be needed in case of dermal reactions, similar to that observed with other medication patches.

Bottom Line

The asenapine transdermal drug delivery system appears to be efficacious and reasonably well tolerated. The treatment of schizophrenia is complex and requires individualized choices in order to optimize outcomes. A patch may be the preferred formulation for selected patients, and caregivers will have the ability to visually check if the medication is being used.

Related Resource

- Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine sublingual • Saphris

Asenapine transdermal system • Secuado

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Valproate • Depakote

1. Noven. US FDA approves SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system, the first-and-only transdermal patch for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. October 15, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.noven.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PR101519.pdf

2. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: 212268Orig1s000. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000Approv.pdf

3. Hisam itsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

4. Allergan USA, Inc. SAPHRIS® (asenapine) sublingual tablets prescribing information. February 2017. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/Final_labeling_text_SAPHRIS-clean-02-2017.pdf

5. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

6. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part II: clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(6):803-830.

7. Citrome L. Chapter 31: Asenapine. In: Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:797-808.

8. Citrome L, Zeni CM, Correll CU. Patches: established and emerging transdermal treatments in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(4):18nr12554. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18nr12554

9. Shayegan DK, Stahl SM. Atypical antipsychotics: matching receptor profile to individual patient’s clinical profile. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(10 suppl 11):6-14.

10. Castelli M, Suzuki K, Komaroff M, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of asenapine transdermal system HP-3070: The first antipsychotic patch in the US. Poster presented virtually at the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 Annual Meeting, May 29-30, 2020. https://www.psychiatrist.com/ascpcorner/Documents/ascp2020/3_ASCP%20Poster%20Abstracts%202020-JCP.pdf

11. Citrome L, Walling DP, Zeni CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of HP-3070, an asenapine transdermal system, in patients with schizophrenia: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13602

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Approval Package: SECAUDO. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000TOC.cfm

13. Szegedi A, Verweij P, van Duijnhoven W, et al. Meta-analyses of the efficacy of asenapine for acute schizophrenia: comparisons with placebo and other antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):1533-1540.

14. Citrome L. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved sublingually absorbed second-generation antipsychotic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(12):1762-1784.

The asenapine transdermal system is available in 3 patch sizes: 20, 30, and 40 cm2, which deliver 3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours of asenapine, respectively.3 Based on the average exposure (area under the plasma concentration curve [AUC]) of asenapine, 3.8 mg/24 hours corresponds to 5 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine, and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to 10 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine.3 The “in-between” dose strength of 5.7 mg/24 hours would correspond to exposure to a total of 15 mg/d of sublingual asenapine. The recommended starting dose for asenapine transdermal system is 3.8 mg/24 hours. The dosage may be increased to 5.7 mg/24 hours or 7.6 mg/24 hours, as needed, after 1 week. The safety of doses above 7.6 mg/24 hours has not been evaluated in clinical studies. Asenapine transdermal system is applied once daily and should be worn for 24 hours only, with only 1 patch at any time. Application sites include the upper arm, upper back, abdomen, and hip. A different application site of clean, dry, intact skin should be selected each time a new patch is applied. Although showering is permitted, the use of asenapine transdermal system during swimming or taking a bath has not been evaluated. Of note, prolonged application of heat over an asenapine transdermal system increases plasma concentrations of asenapine, and thus application of external heat sources (eg, heating pads) over the patch should be avoided.

How it works

Product labeling notes that asenapine is an atypical antipsychotic, and that its efficacy in schizophrenia could be mediated through a combination of antagonist activity at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.3 The pharmacodynamic profile of asenapine is complex5 and receptor-binding assays performed using cloned human serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, and muscarinic receptors demonstrated picomolar affinity (extremely high) for 5-HT2C and 5-HT2A receptors, subnanomolar affinity (very high) for 5-HT7, 5-HT2B, 5-HT6, and D3 receptors, and nanomolar affinity (high) for D2 receptors, as well as histamine H1, D4, a1-adrenergic, a2-adrenergic, D1, 5-HT5, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and histamine H2 receptors. Activity of asenapine is that of antagonism at these receptors. Asenapine has no appreciable affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

The asenapine receptor-binding “fingerprint” differs from that of other antipsychotics. Some of these receptor affinities are of special interest in terms of potential efficacy for pro-cognitive effects and amelioration of abnormal mood.5,9 In terms of tolerability, a relative absence of affinity to muscarinic receptors would predict a low risk for anticholinergic adverse effects, but antagonism at histamine H1 and at a1-adrenergic receptors, either alone or in combination, may cause sedation, and blockade of H1 receptors would also predict weight gain.9 Antagonism of a1-adrenergic receptors can be associated with orthostatic hypotension and neurally mediated reflex bradycardia.9

Clinical pharmacokinetics

Three open-label, randomized, phase 1 studies were conducted to assess the relative bioavailability of asenapine transdermal system vs sublingual asenapine.10 These included single- and multiple-dose studies and clinical trials that examined the effects of different application sites and ethnic groups, and the effect of external heat on medication absorption. Studies were conducted in healthy individuals, except for the multiple-dose study, which was performed in adults with schizophrenia. The AUC for asenapine transdermal system was within the range of that of equivalent doses of sublingual asenapine, but peak exposure (maximum concentration) was significantly lower. As already noted, the AUC of the asenapine patch for 3.8 mg/24 hours and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to sublingual asenapine 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively. Maximum asenapine concentrations are typically reached between 12 and 24 hours, with sustained concentrations during the 24-hour wear time.3 On average, approximately 60% of the available asenapine is released from the transdermal system over 24 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations for asenapine transdermal system were achieved approximately 72 hours after the first application and, in contrast to sublingual asenapine, the peak-trough fluctuations were small (peak-to-trough ratio is 1.5 for asenapine transdermal system compared with >3 for sublingual asenapine). Dose-proportionality at steady state was evident for asenapine transdermal system. This is in contrast to sublingual asenapine, where exposure increases 1.7-fold with a 2-fold increase in dose.4,5 Following patch removal, the apparent elimination half-life is approximately 30 hours.3 The pharmacokinetics of the patch did not vary with regards to the application site (upper arm, upper back, abdomen, or hip area), and the pharmacokinetic profile was similar across the ethnic groups that participated in the study. Direct exposure to external heat did increase both the rate and extent of absorption, so external heat sources should be avoided.3

Efficacy

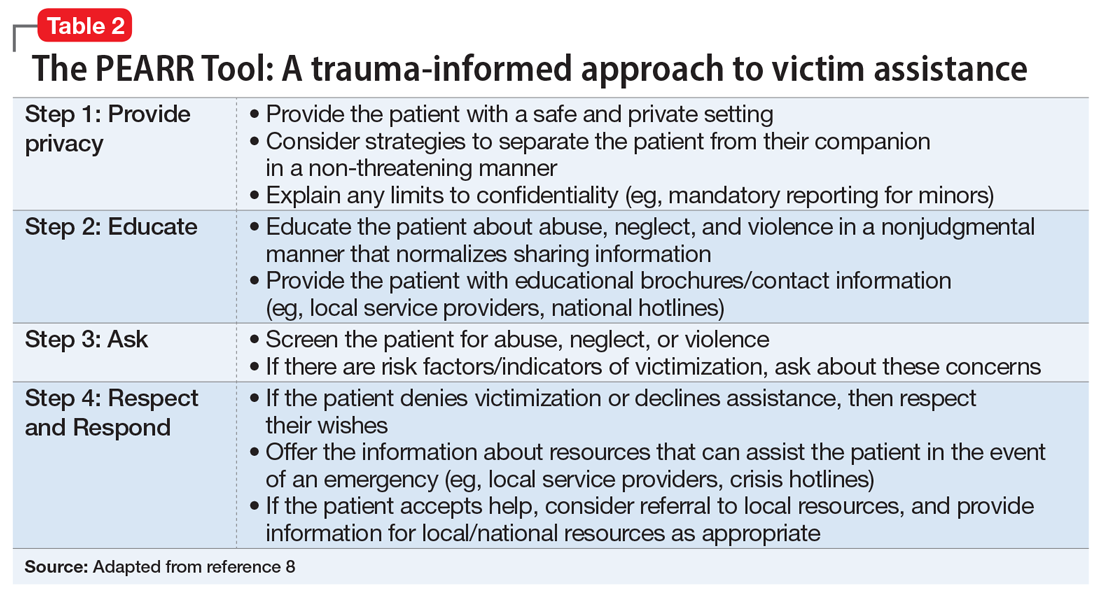

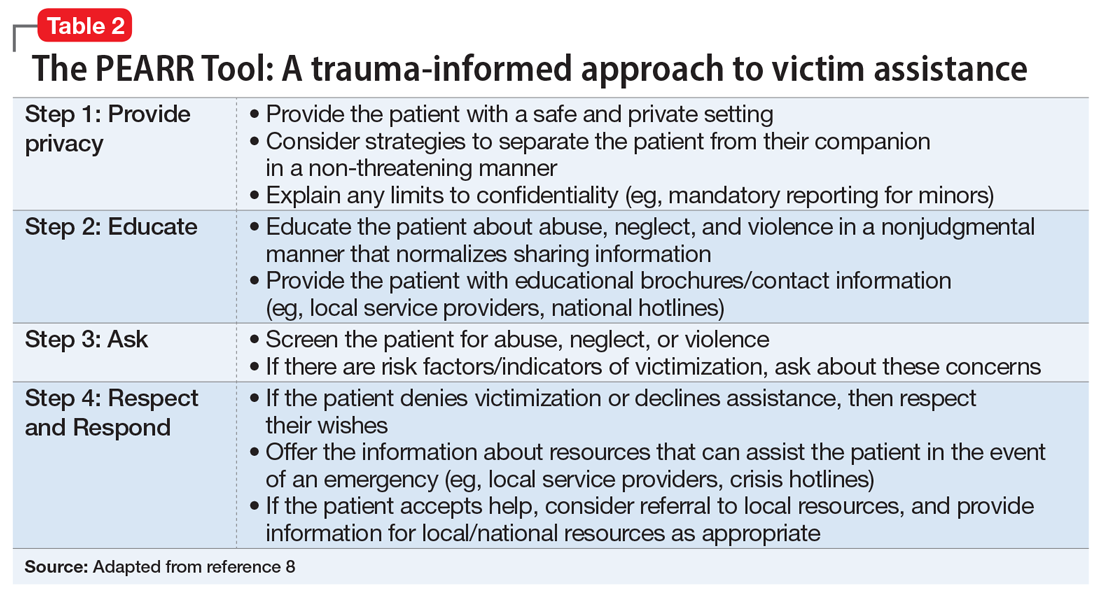

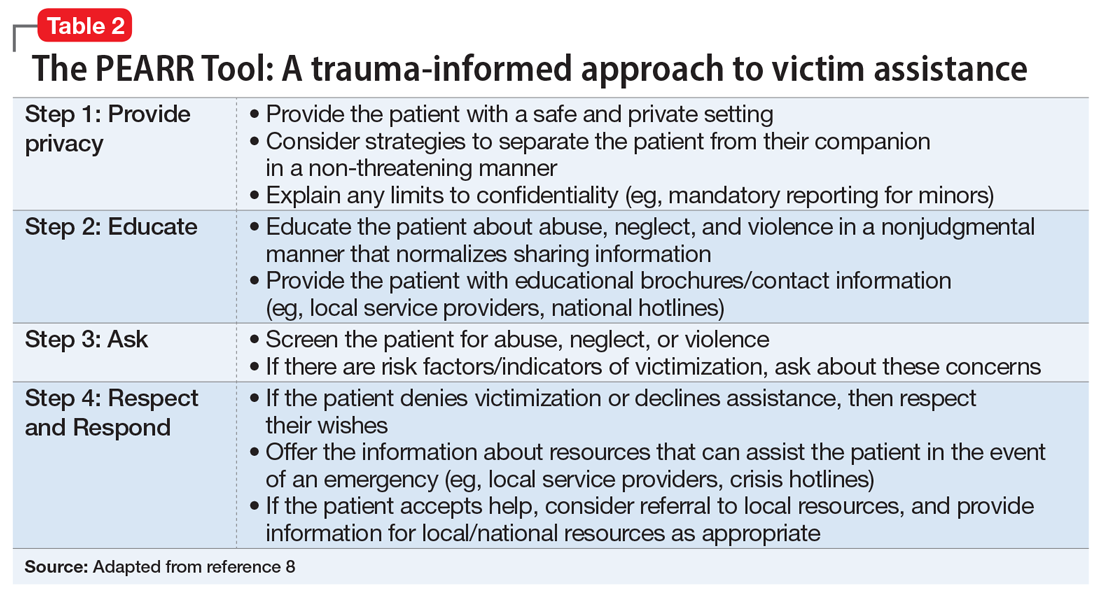

The efficacy profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to mirror that for sublingual asenapine.6,7 In addition to data supporting the use of asenapine as administered sublingually, a phase 3 study specifically assessed efficacy and safety of asenapine transdermal system in adults with schizophrenia.11,12 This study was conducted in the United States and 4 other countries at a total of 59 study sites, and 616 patients with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia were enrolled. After a 3- to 14-day screening/single-blind run-in washout period, participants entered a 6-week inpatient double-blind period. Randomization was 1:1:1 to asenapine transdermal system 3.8 mg/24 hours, 7.6 mg/24 hours, or a placebo patch. Each of the patch doses demonstrated significant improvement vs placebo at Week 6 for the primary (change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score) and key secondary (change in Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness) endpoints. Response at endpoint, as defined by a ≥30% improvement from baseline PANSS total score, or by a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), was also assessed. For either definition of response, both doses of asenapine transdermal system were superior to placebo, with number needed to treat (NNT) (Box) values <10 for the 3.8 mg/24 hours dose (Table 2). These effect sizes are similar to what is known about sublingual asenapine as determined in a meta-analysis performed by the manufacturer and using individual patient data.13

Box

Clinical trials produce a mountain of data that can be difficult to interpret and apply to clinical practice. When reading about studies, you may wonder:

- How large is the effect being measured?

- Is it clinically important?

- Are we reviewing a result that may be statistically significant but irrelevant for day-today patient care?

Number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH)—two tools of evidence-based medicine—can help answer these questions. NNT helps us gauge effect size or clinical significance. It is different from knowing if a clinical trial result is statistically significant. NNT allows us to place a number on how often we can expect to encounter a difference between two interventions. If we see a therapeutic difference once every 100 patients (NNT of 100), the difference between the treatments is not of great concern under most circumstances. But if a difference in outcome is seen once in every 7 patients being treated with an intervention vs another (NNT of 7), the result will likely influence dayto-day practice.

How to calculate NNT (or NNH):

What is the NNT for an outcome for drug A vs drug B?

fA = frequency of outcome for drug A

fB = frequency of outcome for drug B

NNT = 1/[ fA - fB]

By convention, we round up the NNT to the next higher whole number.

For example, let’s say drugs A and B are used to treat depression, and they result in 6-week response rates of 55% and 75%, respectively. The NNT to encounter a difference between drug B and drug A in terms of responders at 6 weeks can be calculated as follows:

- Difference in response rates: .75 -.55 = .20

- NNT: 1/.20 = 5

A rule of thumb: NNT values for a medication vs placebo <10 usually denote a medication we use on a regular basis to treat patients.

a Adapted from Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71. Citrome L. Can you interpret confidence intervals? It’s not that difficult. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):77-82. Additional information can be found in Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407-411 (free to access at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijcp.12142)

Overall tolerability and safety

The systemic safety and tolerability profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to be similar to that for sublingual asenapine, unless there are adverse events that are related to high peak plasma concentrations or large differences between peak and trough plasma concentrations.6 Nonsystemic local application site adverse events would, of course, differ between sublingual vs transdermal administration.

Continue to: Use of asenapine transdermal system...

Use of asenapine transdermal system avoids the dysgeusia and oral hypoesthesia that can be observed with sublingual asenapine4,6; however, dermal effects need to be considered (see Dermal safety). The most commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice that for placebo) for asenapine transdermal system are extrapyramidal disorder, application site reaction, and weight gain.3 For sublingual asenapine for adults with schizophrenia, the list includes akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence.4 These adverse events can be further described using the metric of number needed to harm (NNH) as shown in Table 3.3,4,11,12,14 Of note, extrapyramidal disorder and weight gain appear to be dose-related for asenapine transdermal system. Akathisia appears to be dose-related for sublingual asenapine but not for asenapine transdermal system. Somnolence appears to be associated with sublingual asenapine but not necessarily with asenapine transdermal system.

For sublingual asenapine, the additional indications (bipolar I disorder as acute monotherapy treatment of manic or mixed episodes in adults and pediatric patients age 10 to 17, adjunctive treatment to lithium or valproate in adults, and maintenance monotherapy treatment in adults) have varying commonly encountered adverse reactions.4 Both transdermal asenapine system and sublingual asenapine are contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh C) and those with known hypersensitivity to asenapine or to any components in the formulation. Both formulations carry similar warnings in their prescribing information regarding increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, cerebrovascular adverse reactions in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, metabolic changes, orthostatic hypotension, leukopenia (and neutropenia and agranulocytosis), QT prolongation, seizures, and potential for cognitive and motor impairment.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment in the asenapine transdermal system pivotal trial occurred in 4.9%, 7.8%, and 6.8% of participants in the 3.8 mg/24 hour, 7.6 mg/24 hour, and placebo groups, respectively.11

Dermal safety

In the pivotal efficacy study,11 the incidence of adverse events at patch application sites was higher in the active groups vs placebo (Table 33,4,11,12,14). The most frequently reported patch application site reactions were erythema and pruritus, occurring in approximately 10% and 4% in the active treatment arms vs 1.5% and 1.9% for placebo, respectively. With the exception of 1 adverse event of severe application site erythema during Week 2 (participant received 7.6 mg/24 hour, erythema resolved without intervention, and the patient continued the study), all other patch application site events were mild or moderate in severity. Rates of discontinuation due to application site reactions or skin disorders were ≤0.5% across all groups. In the pharmacokinetic studies,10 no patches were removed because of unacceptable irritation.

Why Rx?

Asenapine transdermal system is the first antipsychotic “patch” FDA-approved for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. Asenapine has been available since 2009 as a sublingual formulation administered twice daily. The pharmacokinetic profile of the once-daily transdermal system demonstrates dose-proportional kinetics and sustained delivery of asenapine with a low peak-to-trough plasma level ratio. Three dosage strengths (3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours) are available, corresponding to blood levels attained with sublingual asenapine exposures of 10, 15, and 20 mg/d, respectively. Application sites are rotated daily and include the upper arms, upper back, abdomen, or hip. Dysgeusia and hypoesthesia of the tongue are avoided with the use of the patch, and there are no food or drink restrictions. Attention will be needed in case of dermal reactions, similar to that observed with other medication patches.

Bottom Line

The asenapine transdermal drug delivery system appears to be efficacious and reasonably well tolerated. The treatment of schizophrenia is complex and requires individualized choices in order to optimize outcomes. A patch may be the preferred formulation for selected patients, and caregivers will have the ability to visually check if the medication is being used.

Related Resource

- Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine sublingual • Saphris

Asenapine transdermal system • Secuado

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Valproate • Depakote

The asenapine transdermal system is available in 3 patch sizes: 20, 30, and 40 cm2, which deliver 3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours of asenapine, respectively.3 Based on the average exposure (area under the plasma concentration curve [AUC]) of asenapine, 3.8 mg/24 hours corresponds to 5 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine, and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to 10 mg twice daily of sublingual asenapine.3 The “in-between” dose strength of 5.7 mg/24 hours would correspond to exposure to a total of 15 mg/d of sublingual asenapine. The recommended starting dose for asenapine transdermal system is 3.8 mg/24 hours. The dosage may be increased to 5.7 mg/24 hours or 7.6 mg/24 hours, as needed, after 1 week. The safety of doses above 7.6 mg/24 hours has not been evaluated in clinical studies. Asenapine transdermal system is applied once daily and should be worn for 24 hours only, with only 1 patch at any time. Application sites include the upper arm, upper back, abdomen, and hip. A different application site of clean, dry, intact skin should be selected each time a new patch is applied. Although showering is permitted, the use of asenapine transdermal system during swimming or taking a bath has not been evaluated. Of note, prolonged application of heat over an asenapine transdermal system increases plasma concentrations of asenapine, and thus application of external heat sources (eg, heating pads) over the patch should be avoided.

How it works

Product labeling notes that asenapine is an atypical antipsychotic, and that its efficacy in schizophrenia could be mediated through a combination of antagonist activity at dopamine D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.3 The pharmacodynamic profile of asenapine is complex5 and receptor-binding assays performed using cloned human serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, and muscarinic receptors demonstrated picomolar affinity (extremely high) for 5-HT2C and 5-HT2A receptors, subnanomolar affinity (very high) for 5-HT7, 5-HT2B, 5-HT6, and D3 receptors, and nanomolar affinity (high) for D2 receptors, as well as histamine H1, D4, a1-adrenergic, a2-adrenergic, D1, 5-HT5, 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, and histamine H2 receptors. Activity of asenapine is that of antagonism at these receptors. Asenapine has no appreciable affinity for muscarinic cholinergic receptors.

The asenapine receptor-binding “fingerprint” differs from that of other antipsychotics. Some of these receptor affinities are of special interest in terms of potential efficacy for pro-cognitive effects and amelioration of abnormal mood.5,9 In terms of tolerability, a relative absence of affinity to muscarinic receptors would predict a low risk for anticholinergic adverse effects, but antagonism at histamine H1 and at a1-adrenergic receptors, either alone or in combination, may cause sedation, and blockade of H1 receptors would also predict weight gain.9 Antagonism of a1-adrenergic receptors can be associated with orthostatic hypotension and neurally mediated reflex bradycardia.9

Clinical pharmacokinetics

Three open-label, randomized, phase 1 studies were conducted to assess the relative bioavailability of asenapine transdermal system vs sublingual asenapine.10 These included single- and multiple-dose studies and clinical trials that examined the effects of different application sites and ethnic groups, and the effect of external heat on medication absorption. Studies were conducted in healthy individuals, except for the multiple-dose study, which was performed in adults with schizophrenia. The AUC for asenapine transdermal system was within the range of that of equivalent doses of sublingual asenapine, but peak exposure (maximum concentration) was significantly lower. As already noted, the AUC of the asenapine patch for 3.8 mg/24 hours and 7.6 mg/24 hours corresponds to sublingual asenapine 5 mg and 10 mg twice daily, respectively. Maximum asenapine concentrations are typically reached between 12 and 24 hours, with sustained concentrations during the 24-hour wear time.3 On average, approximately 60% of the available asenapine is released from the transdermal system over 24 hours. Steady-state plasma concentrations for asenapine transdermal system were achieved approximately 72 hours after the first application and, in contrast to sublingual asenapine, the peak-trough fluctuations were small (peak-to-trough ratio is 1.5 for asenapine transdermal system compared with >3 for sublingual asenapine). Dose-proportionality at steady state was evident for asenapine transdermal system. This is in contrast to sublingual asenapine, where exposure increases 1.7-fold with a 2-fold increase in dose.4,5 Following patch removal, the apparent elimination half-life is approximately 30 hours.3 The pharmacokinetics of the patch did not vary with regards to the application site (upper arm, upper back, abdomen, or hip area), and the pharmacokinetic profile was similar across the ethnic groups that participated in the study. Direct exposure to external heat did increase both the rate and extent of absorption, so external heat sources should be avoided.3

Efficacy

The efficacy profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to mirror that for sublingual asenapine.6,7 In addition to data supporting the use of asenapine as administered sublingually, a phase 3 study specifically assessed efficacy and safety of asenapine transdermal system in adults with schizophrenia.11,12 This study was conducted in the United States and 4 other countries at a total of 59 study sites, and 616 patients with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia were enrolled. After a 3- to 14-day screening/single-blind run-in washout period, participants entered a 6-week inpatient double-blind period. Randomization was 1:1:1 to asenapine transdermal system 3.8 mg/24 hours, 7.6 mg/24 hours, or a placebo patch. Each of the patch doses demonstrated significant improvement vs placebo at Week 6 for the primary (change in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale [PANSS] total score) and key secondary (change in Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness) endpoints. Response at endpoint, as defined by a ≥30% improvement from baseline PANSS total score, or by a Clinical Global Impression–Improvement score of 1 (very much improved) or 2 (much improved), was also assessed. For either definition of response, both doses of asenapine transdermal system were superior to placebo, with number needed to treat (NNT) (Box) values <10 for the 3.8 mg/24 hours dose (Table 2). These effect sizes are similar to what is known about sublingual asenapine as determined in a meta-analysis performed by the manufacturer and using individual patient data.13

Box

Clinical trials produce a mountain of data that can be difficult to interpret and apply to clinical practice. When reading about studies, you may wonder:

- How large is the effect being measured?

- Is it clinically important?

- Are we reviewing a result that may be statistically significant but irrelevant for day-today patient care?

Number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH)—two tools of evidence-based medicine—can help answer these questions. NNT helps us gauge effect size or clinical significance. It is different from knowing if a clinical trial result is statistically significant. NNT allows us to place a number on how often we can expect to encounter a difference between two interventions. If we see a therapeutic difference once every 100 patients (NNT of 100), the difference between the treatments is not of great concern under most circumstances. But if a difference in outcome is seen once in every 7 patients being treated with an intervention vs another (NNT of 7), the result will likely influence dayto-day practice.

How to calculate NNT (or NNH):

What is the NNT for an outcome for drug A vs drug B?

fA = frequency of outcome for drug A

fB = frequency of outcome for drug B

NNT = 1/[ fA - fB]

By convention, we round up the NNT to the next higher whole number.

For example, let’s say drugs A and B are used to treat depression, and they result in 6-week response rates of 55% and 75%, respectively. The NNT to encounter a difference between drug B and drug A in terms of responders at 6 weeks can be calculated as follows:

- Difference in response rates: .75 -.55 = .20

- NNT: 1/.20 = 5

A rule of thumb: NNT values for a medication vs placebo <10 usually denote a medication we use on a regular basis to treat patients.

a Adapted from Citrome L. Dissecting clinical trials with ‘number needed to treat.’ Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):66-71. Citrome L. Can you interpret confidence intervals? It’s not that difficult. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):77-82. Additional information can be found in Citrome L, Ketter TA. When does a difference make a difference? Interpretation of number needed to treat, number needed to harm, and likelihood to be helped or harmed. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):407-411 (free to access at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ijcp.12142)

Overall tolerability and safety

The systemic safety and tolerability profile for asenapine transdermal system would be expected to be similar to that for sublingual asenapine, unless there are adverse events that are related to high peak plasma concentrations or large differences between peak and trough plasma concentrations.6 Nonsystemic local application site adverse events would, of course, differ between sublingual vs transdermal administration.

Continue to: Use of asenapine transdermal system...

Use of asenapine transdermal system avoids the dysgeusia and oral hypoesthesia that can be observed with sublingual asenapine4,6; however, dermal effects need to be considered (see Dermal safety). The most commonly observed adverse reactions (incidence ≥5% and at least twice that for placebo) for asenapine transdermal system are extrapyramidal disorder, application site reaction, and weight gain.3 For sublingual asenapine for adults with schizophrenia, the list includes akathisia, oral hypoesthesia, and somnolence.4 These adverse events can be further described using the metric of number needed to harm (NNH) as shown in Table 3.3,4,11,12,14 Of note, extrapyramidal disorder and weight gain appear to be dose-related for asenapine transdermal system. Akathisia appears to be dose-related for sublingual asenapine but not for asenapine transdermal system. Somnolence appears to be associated with sublingual asenapine but not necessarily with asenapine transdermal system.

For sublingual asenapine, the additional indications (bipolar I disorder as acute monotherapy treatment of manic or mixed episodes in adults and pediatric patients age 10 to 17, adjunctive treatment to lithium or valproate in adults, and maintenance monotherapy treatment in adults) have varying commonly encountered adverse reactions.4 Both transdermal asenapine system and sublingual asenapine are contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic impairment (Child-Pugh C) and those with known hypersensitivity to asenapine or to any components in the formulation. Both formulations carry similar warnings in their prescribing information regarding increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, cerebrovascular adverse reactions in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, tardive dyskinesia, metabolic changes, orthostatic hypotension, leukopenia (and neutropenia and agranulocytosis), QT prolongation, seizures, and potential for cognitive and motor impairment.

Adverse events leading to discontinuation of study treatment in the asenapine transdermal system pivotal trial occurred in 4.9%, 7.8%, and 6.8% of participants in the 3.8 mg/24 hour, 7.6 mg/24 hour, and placebo groups, respectively.11

Dermal safety

In the pivotal efficacy study,11 the incidence of adverse events at patch application sites was higher in the active groups vs placebo (Table 33,4,11,12,14). The most frequently reported patch application site reactions were erythema and pruritus, occurring in approximately 10% and 4% in the active treatment arms vs 1.5% and 1.9% for placebo, respectively. With the exception of 1 adverse event of severe application site erythema during Week 2 (participant received 7.6 mg/24 hour, erythema resolved without intervention, and the patient continued the study), all other patch application site events were mild or moderate in severity. Rates of discontinuation due to application site reactions or skin disorders were ≤0.5% across all groups. In the pharmacokinetic studies,10 no patches were removed because of unacceptable irritation.

Why Rx?

Asenapine transdermal system is the first antipsychotic “patch” FDA-approved for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. Asenapine has been available since 2009 as a sublingual formulation administered twice daily. The pharmacokinetic profile of the once-daily transdermal system demonstrates dose-proportional kinetics and sustained delivery of asenapine with a low peak-to-trough plasma level ratio. Three dosage strengths (3.8, 5.7, and 7.6 mg/24 hours) are available, corresponding to blood levels attained with sublingual asenapine exposures of 10, 15, and 20 mg/d, respectively. Application sites are rotated daily and include the upper arms, upper back, abdomen, or hip. Dysgeusia and hypoesthesia of the tongue are avoided with the use of the patch, and there are no food or drink restrictions. Attention will be needed in case of dermal reactions, similar to that observed with other medication patches.

Bottom Line

The asenapine transdermal drug delivery system appears to be efficacious and reasonably well tolerated. The treatment of schizophrenia is complex and requires individualized choices in order to optimize outcomes. A patch may be the preferred formulation for selected patients, and caregivers will have the ability to visually check if the medication is being used.

Related Resource

- Hisamitsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

Drug Brand Names

Asenapine sublingual • Saphris

Asenapine transdermal system • Secuado

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Valproate • Depakote

1. Noven. US FDA approves SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system, the first-and-only transdermal patch for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. October 15, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.noven.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PR101519.pdf

2. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: 212268Orig1s000. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000Approv.pdf

3. Hisam itsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

4. Allergan USA, Inc. SAPHRIS® (asenapine) sublingual tablets prescribing information. February 2017. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/Final_labeling_text_SAPHRIS-clean-02-2017.pdf

5. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

6. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part II: clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(6):803-830.

7. Citrome L. Chapter 31: Asenapine. In: Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:797-808.

8. Citrome L, Zeni CM, Correll CU. Patches: established and emerging transdermal treatments in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(4):18nr12554. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18nr12554

9. Shayegan DK, Stahl SM. Atypical antipsychotics: matching receptor profile to individual patient’s clinical profile. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(10 suppl 11):6-14.

10. Castelli M, Suzuki K, Komaroff M, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of asenapine transdermal system HP-3070: The first antipsychotic patch in the US. Poster presented virtually at the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 Annual Meeting, May 29-30, 2020. https://www.psychiatrist.com/ascpcorner/Documents/ascp2020/3_ASCP%20Poster%20Abstracts%202020-JCP.pdf

11. Citrome L, Walling DP, Zeni CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of HP-3070, an asenapine transdermal system, in patients with schizophrenia: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13602

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Approval Package: SECAUDO. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000TOC.cfm

13. Szegedi A, Verweij P, van Duijnhoven W, et al. Meta-analyses of the efficacy of asenapine for acute schizophrenia: comparisons with placebo and other antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):1533-1540.

14. Citrome L. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved sublingually absorbed second-generation antipsychotic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(12):1762-1784.

1. Noven. US FDA approves SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system, the first-and-only transdermal patch for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia. October 15, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.noven.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/PR101519.pdf

2. US Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Approval Package for: APPLICATION NUMBER: 212268Orig1s000. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000Approv.pdf

3. Hisam itsu Pharmaceutical Co., Inc. SECUADO® (asenapine) transdermal system prescribing information. October 2019. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212268s000lbl.pdf

4. Allergan USA, Inc. SAPHRIS® (asenapine) sublingual tablets prescribing information. February 2017. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://media.allergan.com/actavis/actavis/media/allergan-pdf-documents/product-prescribing/Final_labeling_text_SAPHRIS-clean-02-2017.pdf

5. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part I: chemistry, receptor affinity profile, pharmacokinetics and metabolism. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2014;10(6):893-903.

6. Citrome L. Asenapine review, part II: clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(6):803-830.

7. Citrome L. Chapter 31: Asenapine. In: Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2017:797-808.

8. Citrome L, Zeni CM, Correll CU. Patches: established and emerging transdermal treatments in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(4):18nr12554. doi: 10.4088/JCP.18nr12554

9. Shayegan DK, Stahl SM. Atypical antipsychotics: matching receptor profile to individual patient’s clinical profile. CNS Spectr. 2004;9(10 suppl 11):6-14.

10. Castelli M, Suzuki K, Komaroff M, et al. Pharmacokinetic profile of asenapine transdermal system HP-3070: The first antipsychotic patch in the US. Poster presented virtually at the American Society for Clinical Psychopharmacology (ASCP) 2020 Annual Meeting, May 29-30, 2020. https://www.psychiatrist.com/ascpcorner/Documents/ascp2020/3_ASCP%20Poster%20Abstracts%202020-JCP.pdf

11. Citrome L, Walling DP, Zeni CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of HP-3070, an asenapine transdermal system, in patients with schizophrenia: a phase 3, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;82(1):20m13602. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13602

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Approval Package: SECAUDO. October 11, 2019. Accessed January 15, 2021. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/212268Orig1s000TOC.cfm

13. Szegedi A, Verweij P, van Duijnhoven W, et al. Meta-analyses of the efficacy of asenapine for acute schizophrenia: comparisons with placebo and other antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(12):1533-1540.

14. Citrome L. Asenapine for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the efficacy and safety profile for this newly approved sublingually absorbed second-generation antipsychotic. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(12):1762-1784.

Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder?

CASE Visual, auditory, and tactile hallucinations

Mr. B, age 93, is brought to the emergency department by his son after experiencing hallucinations where he reportedly saw and heard individuals in his home. In frustration, Mr. B wielded a knife because he “wanted them to go away.”

Mr. B and his son report that the hallucinations had begun 2 years ago, without prior trauma, medication changes, changes in social situation, or other apparent precipitating events. The hallucinations “come and go,” without preceding symptoms, but have recurring content involving a friendly man named “Harry,” people coming out of the television, 2 children playing, and water covering the floor. Mr. B acknowledges these are hallucinations and had not felt threatened by them until recently, when he wielded the knife. He often tries to talk to them, but they do not reply.

Mr. B also reports intermittent auditory hallucinations including voices at home (non-command) and papers rustling. He also describes tactile hallucinations, where he says he can feel Harry and others prodding him, knocking things out of his hands, or splashing him with water.

Mr. B is admitted to the hospital because he is a danger to himself and others. While on the inpatient unit, Mr. B is pleasant with staff, and eats and sleeps normally; however, he continues to have hallucinations of Harry. Mr. B reports seeing Harry in the hall, and says that Harry pulls out Mr. B’s earpiece and steals his fork. Mr. B also reports hearing a sound “like a bee buzzing.” Mr. B is started on risperidone, 1 mg nightly, for a presumed psychotic disorder.

HISTORY Independent and in good health

Mr. B lives alone and is independent in his activities of daily living. He spends his days at home, often visited by his children, who bring him groceries and other necessities.

Mr. B takes no medications, and has no history of psychiatric treatment; psychotic, manic, or depressive episodes; posttraumatic stress disorder; obsessive-compulsive disorder; or recent emotional stress. His medical history includes chronic progressive hearing loss, which is managed with hearing aids; macular degeneration; and prior bilateral cataract surgeries.

EVALUATION Mental status exam and objective findings

During his evaluation, Mr. B appears well-nourished, and wears glasses and hearing aids. During the interview, he is euthymic with appropriately reactive affect. He is talkative but redirectable, with a goal-directed thought process. Mr. B does not appear to be internally preoccupied. His hearing is impaired, and he often requires questions to be repeated loudly. He is oriented to person, place, and time. There are no signs of delusions, paranoia, thought blocking, thought broadcasting/insertion, or referential thinking. He denies depressed mood, anhedonia, fatigue, sleep changes, or manic symptoms. He denies the occurrence of auditory or visual hallucinations during the evaluation.

Continue to: A neurologic exam shows...

A neurologic exam shows impaired hearing bilaterally and impaired visual acuity. Even with glasses, both eyes have acuity only to finger counting. All other cranial nerves are normal, and Mr. B’s strength, sensation, and cerebellar function are all intact, without rigidity, numbness, or tingling. His gait is steady without a walker, with symmetric arm swing and slight dragging of his feet. His vitals are stable, with normal orthostatic pressures.

Other objective data include a score of 24/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, notable for deficits in visuospatial orientation, attention, and calculation, with language and copying limited by poor vision. Mr. B scores 16/22 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Blind (adapted version of MoCA), which is equivalent to a 22/30 on the MoCA, indicating some mild cognitive impairment; however, this modified test is still limited by his poor hearing. His serum and urine laboratory workup show no liver, kidney, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no sign of infection, negative urine drug screen, and normal B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. He undergoes a brain MRI, which shows chronic microvascular ischemic change, without mass lesions, infarction, or other pathology.

[polldaddy:10729178]

The authors’ observations

Given Mr. B’s presentation, we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder. He had no psychiatric history, with organized thought, a reactive affect, and no delusions, paranoia, or other psychotic symptoms, all pointing against psychosis. His brain MRI showed no malignancy or other lesions. He had no substance use history to suggest intoxication/withdrawal. His intact attention and orientation did not suggest delirium, and his serum and urine studies were all negative. Although his blaming Harry for knocking things out of his hands could suggest confabulation, Mr. B had no other signs of Korsakoff syndrome, such as ataxia, general confusion, or malnourishment.

We also considered early dementia. There was suspicion for Lewy body dementia given Mr. B’s prominent fluctuating visual hallucinations; however, he displayed no other signs of the disorder, such as parkinsonism, dysautonomia, or sensitivity to the antipsychotic (risperidone 1 mg nightly) started on admission. The presence of 1 core feature of Lewy body dementia—visual hallucinations—indicated a possible, but not probable, diagnosis. Additionally, Mr. B did not have the characteristic features of other types of dementia, such as the stepwise progression of vascular dementia, the behavioral disinhibition of frontotemporal dementia, or the insidious forgetfulness, confusion, language problems, or paranoia that may appear in Alzheimer’s disease. Remarkably, he had a relatively normal brain MRI for his age, given chronic microvascular ischemic changes, and cognitive testing that indicated only mild impairment further pointed against a dementia process.

Charles Bonnet syndrome

Based on Mr. B’s severe vision loss and history of ocular surgeries, we diagnosed him with CBS, described as visual hallucinations in the presence of impaired vision. Charles Bonnet syndrome has been observed in several disorders that affect vision, most commonly macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma, with an estimated prevalence of 11% to 39% in older patients with ocular disease.1,2 Visual hallucinations in CBS occur due to ocular disease, likely resulting from changes in afferent sensory input to visual cortical regions of the brain. Table 13 outlines the features of visual hallucinations in patients with CBS. The subsequent disinhibition and spontaneous firing of the visual association cortices leads to the “release hallucinations” of the syndrome.4 The disorder is thought to be significantly underdiagnosed—in a survey of patients with CBS, only 15% had reported their visual hallucinations to a physician.5

Continue to: Mr. B's symptoms...

Mr. B’s symptoms are atypical for CBS, but they fit the diagnosis when considering the entire clinical picture. While hallucinations in CBS are more often simple shapes, complex hallucinations including people and scenes have been noted in several instances.6

Similar to Mr. B’s case, patients with CBS can have recurring figures in their hallucinations, and the images may even move across the visual field.1 Patients with CBS also frequently recognize that their hallucinations are not real, and may or may not be distressed by them.4 Patients with CBS often have hallucinations multiple times daily, lasting from a few seconds to many minutes,7 consistent with Mr. B’s temporary symptoms.

Although auditory and tactile hallucinations are typically not included in CBS, they can also be explained by Mr. B’s significant sensory impairment. Severe hearing impairment in geriatric adults has been associated with auditory hallucinations8; in 1 survey, half of these hallucinations consisted of voices.9 In contrast, tactile hallucinations are not described in sensory deprivation literature. However, in the context of Mr. B’s severe comorbid hearing and vision loss, we propose that these hallucinations reflect his interpretation of sensory events around him, and their integration into his extensive hallucination framework. In other words, Harry poking him and causing him to drop things may be Mr. B’s way of rationalizing events that he has trouble perceiving entirely, or his mild forgetfulness. Mr. B’s social isolation is another factor that may worsen his sensory deprivation and contribute to his extensive hallucinations.10 Additionally, his mild cognitive deficits on testing with chronic microvascular changes on the MRI may suggest a mild vascular-related dementia process, which could also exacerbate his hallucinations. While classic CBS occurs without cognitive impairment, dementia can often co-occur with CBS.11

TREATMENT No significant improvement with medications

During his inpatient stay, Mr. B is treated with risperidone, 1 mg nightly, and is also started on donepezil, 5 mg/d, to treat a possible comorbid dementia. However, he continues to hallucinate without significant improvement.

[polldaddy:10729181]

The authors’ observations

There is no definitive treatment for CBS, and while the hallucinations may spontaneously resolve, per case reports, this typically occurs only as visual loss progresses to total blindness.12 However, many patients can have the hallucinations remit after the underlying ocular etiology is corrected, such as through ocular surgery.13 Other optical interventions, such as special glasses or contact lenses, may help maximize remaining vision.8 In patients without this option, such as Mr. B, there are limited data on beneficial medications for CBS.

Continue to: Evidence for treatment of CBS...

Evidence for treatment of CBS with antipsychotic medications is mixed. Some case studies have found them to be ineffective, while others have found agents such as olanzapine or risperidone to be partially helpful in reducing symptoms.14 There are also data from case reports that may support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, antiepileptics (carbamazepine, valproate, gabapentin, and clonazepam), and certain antidepressants (escitalopram, venlafaxine) (Table 28,11).3

Addressing loneliness and social isolation

With minimal definitive evidence for pharmacologic management, the most important intervention for treating CBS may be changing the patient’s sensory environment. Specifically, loneliness and social isolation are major exacerbating factors of CBS, and many clinicians advocate for the consistent presence of a sympathetic professional. Reassurance that hallucinations are from ocular disease rather than a primary mental disorder may be extremely relieving for patients.11 A psychoeducation or support group may also be beneficial, not only for giving patients more social contact, but also for teaching them coping skills or strategies to reduce hallucinations, such as distraction, turning on more lights, or even certain eye/blinking movements.11 Table 28,11 (page 49) outlines behavioral interventions for CBS.

Regardless of etiology, Mr. B’s hallucinations significantly affected his quality of life. During his inpatient stay, he was treated with

OUTCOME Home care and family involvement

After discussion with Mr. B and his family about the risks and benefits of medication, the risperidone and donepezil are discontinued. Ultimately, it is determined that Mr. B requires a higher level of home care, both for his safety and to improve his social contact. Mr. B returns home with a combination of a professional home health aide and increased family involvement.

Bottom Line

When evaluating visual hallucinations in older adults, Charles Bonnet syndrome (CBS) should be considered. Sensory deprivation and social isolation are significant risk factors for CBS. While evidence is inconclusive for medical treatment, reassurance and behavioral interventions can often improve symptoms.

Continue to: Related Resources

Related Resources

- Charles Bonnet Syndrome Foundation. http://www.charlesbonnetsyndrome.org

- Schultz G, Melzack R. The Charles Bonnet syndrome: ‘phantom visual images’. Perception. 1991;20:809-825.

- Menon GJ, Rahman I, Menon SJ, et al. Complex visual hallucinations in the visually impaired: the Charles Bonnet syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(1):58-72.

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Donepezil • Aricept

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depakote

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Menon GJ, Rahman I, Menon SJ, et al. Complex visual hallucinations in the visually impaired: the Charles Bonnet syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003;48(1):58-72.

2. Cox TM, Ffytche DH. Negative outcome Charles Bonnet syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98(9):1236-1239.

3. Pelak VS. Visual release hallucinations (Charles Bonnet syndrome). UpToDate. Updated February 5, 2019. Accessed September 17, 2020. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/visual-release-hallucinations-charles-bonnet-syndrome

4. Burke W. The neural basis of Charles Bonnet hallucinations: a hypothesis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73(5):535-541.

5. Scott IU, Schein OD, Feuer WJ, et al. Visual hallucinations in patients with retinal disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131(5):590-598.

6. Lepore FE. Spontaneous visual phenomena with visual loss: 104 patients with lesions of retinal and neural afferent pathways. Neurology. 1990;40(3 Pt 1):444-447.

7. Nesher R, Nesher G, Epstein E, et al. Charles Bonnet syndrome in glaucoma patients with low vision. J Glaucoma. 2001;10(5):396-400.

8. Pang L. Hallucinations experienced by visually impaired: Charles Bonnet syndrome. Optom Vis Sci. 2016;93(12):1466-1478.

9. Linszen M, Van Zanten G, Teunisse R, et al. Auditory hallucinations in adults with hearing impairment: a large prevalence study. Psychological Medicine. 2019;49(1):132-139.

10. Teunisse RJ, Cruysberg JR, Hoefnagels WH, et al. Social and psychological characteristics of elderly visually handicapped patients with the Charles Bonnet syndrome. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40(4):315-319.

11. Eperjesi F, Akbarali A. Rehabilitation in Charles Bonnet syndrome: a review of treatment options. Clin Exp Optom. 2004;87(3):149-152.

12. Fernandez A, Lichtshein G, Vieweg WVR. The Charles Bonnet syndrome: a review. J Nen Ment Dis. 1997;185(3):195-200.

13. Rosenbaum F, Harati Y, Rolak L, et al. Visual hallucinations in sane people: Charles Bonnet syndrome. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35(1):66-68.

14. Coletti Moja M, Milano E, Gasverde S, et al. Olanzapine therapy in hallucinatory visions related to Bonnet syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2005;26(3):168-170.

CASE Visual, auditory, and tactile hallucinations

Mr. B, age 93, is brought to the emergency department by his son after experiencing hallucinations where he reportedly saw and heard individuals in his home. In frustration, Mr. B wielded a knife because he “wanted them to go away.”

Mr. B and his son report that the hallucinations had begun 2 years ago, without prior trauma, medication changes, changes in social situation, or other apparent precipitating events. The hallucinations “come and go,” without preceding symptoms, but have recurring content involving a friendly man named “Harry,” people coming out of the television, 2 children playing, and water covering the floor. Mr. B acknowledges these are hallucinations and had not felt threatened by them until recently, when he wielded the knife. He often tries to talk to them, but they do not reply.

Mr. B also reports intermittent auditory hallucinations including voices at home (non-command) and papers rustling. He also describes tactile hallucinations, where he says he can feel Harry and others prodding him, knocking things out of his hands, or splashing him with water.

Mr. B is admitted to the hospital because he is a danger to himself and others. While on the inpatient unit, Mr. B is pleasant with staff, and eats and sleeps normally; however, he continues to have hallucinations of Harry. Mr. B reports seeing Harry in the hall, and says that Harry pulls out Mr. B’s earpiece and steals his fork. Mr. B also reports hearing a sound “like a bee buzzing.” Mr. B is started on risperidone, 1 mg nightly, for a presumed psychotic disorder.

HISTORY Independent and in good health

Mr. B lives alone and is independent in his activities of daily living. He spends his days at home, often visited by his children, who bring him groceries and other necessities.

Mr. B takes no medications, and has no history of psychiatric treatment; psychotic, manic, or depressive episodes; posttraumatic stress disorder; obsessive-compulsive disorder; or recent emotional stress. His medical history includes chronic progressive hearing loss, which is managed with hearing aids; macular degeneration; and prior bilateral cataract surgeries.

EVALUATION Mental status exam and objective findings

During his evaluation, Mr. B appears well-nourished, and wears glasses and hearing aids. During the interview, he is euthymic with appropriately reactive affect. He is talkative but redirectable, with a goal-directed thought process. Mr. B does not appear to be internally preoccupied. His hearing is impaired, and he often requires questions to be repeated loudly. He is oriented to person, place, and time. There are no signs of delusions, paranoia, thought blocking, thought broadcasting/insertion, or referential thinking. He denies depressed mood, anhedonia, fatigue, sleep changes, or manic symptoms. He denies the occurrence of auditory or visual hallucinations during the evaluation.

Continue to: A neurologic exam shows...

A neurologic exam shows impaired hearing bilaterally and impaired visual acuity. Even with glasses, both eyes have acuity only to finger counting. All other cranial nerves are normal, and Mr. B’s strength, sensation, and cerebellar function are all intact, without rigidity, numbness, or tingling. His gait is steady without a walker, with symmetric arm swing and slight dragging of his feet. His vitals are stable, with normal orthostatic pressures.

Other objective data include a score of 24/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, notable for deficits in visuospatial orientation, attention, and calculation, with language and copying limited by poor vision. Mr. B scores 16/22 on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Blind (adapted version of MoCA), which is equivalent to a 22/30 on the MoCA, indicating some mild cognitive impairment; however, this modified test is still limited by his poor hearing. His serum and urine laboratory workup show no liver, kidney, metabolic, or electrolyte abnormalities, no sign of infection, negative urine drug screen, and normal B12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. He undergoes a brain MRI, which shows chronic microvascular ischemic change, without mass lesions, infarction, or other pathology.

[polldaddy:10729178]

The authors’ observations

Given Mr. B’s presentation, we ruled out a primary psychotic disorder. He had no psychiatric history, with organized thought, a reactive affect, and no delusions, paranoia, or other psychotic symptoms, all pointing against psychosis. His brain MRI showed no malignancy or other lesions. He had no substance use history to suggest intoxication/withdrawal. His intact attention and orientation did not suggest delirium, and his serum and urine studies were all negative. Although his blaming Harry for knocking things out of his hands could suggest confabulation, Mr. B had no other signs of Korsakoff syndrome, such as ataxia, general confusion, or malnourishment.

We also considered early dementia. There was suspicion for Lewy body dementia given Mr. B’s prominent fluctuating visual hallucinations; however, he displayed no other signs of the disorder, such as parkinsonism, dysautonomia, or sensitivity to the antipsychotic (risperidone 1 mg nightly) started on admission. The presence of 1 core feature of Lewy body dementia—visual hallucinations—indicated a possible, but not probable, diagnosis. Additionally, Mr. B did not have the characteristic features of other types of dementia, such as the stepwise progression of vascular dementia, the behavioral disinhibition of frontotemporal dementia, or the insidious forgetfulness, confusion, language problems, or paranoia that may appear in Alzheimer’s disease. Remarkably, he had a relatively normal brain MRI for his age, given chronic microvascular ischemic changes, and cognitive testing that indicated only mild impairment further pointed against a dementia process.

Charles Bonnet syndrome

Based on Mr. B’s severe vision loss and history of ocular surgeries, we diagnosed him with CBS, described as visual hallucinations in the presence of impaired vision. Charles Bonnet syndrome has been observed in several disorders that affect vision, most commonly macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy, and glaucoma, with an estimated prevalence of 11% to 39% in older patients with ocular disease.1,2 Visual hallucinations in CBS occur due to ocular disease, likely resulting from changes in afferent sensory input to visual cortical regions of the brain. Table 13 outlines the features of visual hallucinations in patients with CBS. The subsequent disinhibition and spontaneous firing of the visual association cortices leads to the “release hallucinations” of the syndrome.4 The disorder is thought to be significantly underdiagnosed—in a survey of patients with CBS, only 15% had reported their visual hallucinations to a physician.5

Continue to: Mr. B's symptoms...

Mr. B’s symptoms are atypical for CBS, but they fit the diagnosis when considering the entire clinical picture. While hallucinations in CBS are more often simple shapes, complex hallucinations including people and scenes have been noted in several instances.6

Similar to Mr. B’s case, patients with CBS can have recurring figures in their hallucinations, and the images may even move across the visual field.1 Patients with CBS also frequently recognize that their hallucinations are not real, and may or may not be distressed by them.4 Patients with CBS often have hallucinations multiple times daily, lasting from a few seconds to many minutes,7 consistent with Mr. B’s temporary symptoms.

Although auditory and tactile hallucinations are typically not included in CBS, they can also be explained by Mr. B’s significant sensory impairment. Severe hearing impairment in geriatric adults has been associated with auditory hallucinations8; in 1 survey, half of these hallucinations consisted of voices.9 In contrast, tactile hallucinations are not described in sensory deprivation literature. However, in the context of Mr. B’s severe comorbid hearing and vision loss, we propose that these hallucinations reflect his interpretation of sensory events around him, and their integration into his extensive hallucination framework. In other words, Harry poking him and causing him to drop things may be Mr. B’s way of rationalizing events that he has trouble perceiving entirely, or his mild forgetfulness. Mr. B’s social isolation is another factor that may worsen his sensory deprivation and contribute to his extensive hallucinations.10 Additionally, his mild cognitive deficits on testing with chronic microvascular changes on the MRI may suggest a mild vascular-related dementia process, which could also exacerbate his hallucinations. While classic CBS occurs without cognitive impairment, dementia can often co-occur with CBS.11

TREATMENT No significant improvement with medications

During his inpatient stay, Mr. B is treated with risperidone, 1 mg nightly, and is also started on donepezil, 5 mg/d, to treat a possible comorbid dementia. However, he continues to hallucinate without significant improvement.

[polldaddy:10729181]

The authors’ observations

There is no definitive treatment for CBS, and while the hallucinations may spontaneously resolve, per case reports, this typically occurs only as visual loss progresses to total blindness.12 However, many patients can have the hallucinations remit after the underlying ocular etiology is corrected, such as through ocular surgery.13 Other optical interventions, such as special glasses or contact lenses, may help maximize remaining vision.8 In patients without this option, such as Mr. B, there are limited data on beneficial medications for CBS.

Continue to: Evidence for treatment of CBS...

Evidence for treatment of CBS with antipsychotic medications is mixed. Some case studies have found them to be ineffective, while others have found agents such as olanzapine or risperidone to be partially helpful in reducing symptoms.14 There are also data from case reports that may support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors such as donepezil, antiepileptics (carbamazepine, valproate, gabapentin, and clonazepam), and certain antidepressants (escitalopram, venlafaxine) (Table 28,11).3

Addressing loneliness and social isolation