User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

Managing metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia

Mr. N, age 55, has a long, documented history of schizophrenia. His overall baseline functioning has been poor because he is socially isolated, does not work, and lives in subsidized housing paid for by the county where he lives. His psychosocial circumstances have limited his ability to afford or otherwise obtain nutritious food or participate in any type of regular exercise program. He has been maintained on olanzapine, 20 mg nightly, for the past 5 years. During the past year, his functioning and overall quality of life have declined even further after he was diagnosed with hypertension. Mr. N’s in-office blood pressure was 160/95 mm Hg (normal range: systolic blood pressure, 90 to 120 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure, 60 to 80 mm Hg). He says his primary care physician informed him that he is pre-diabetic after his hemoglobin A1c came back at 6.0 mg/dL (normal range <5.7 mg/dL) and his body mass index was 32 kg/m2 (normal range 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). Currently, Mr. N’s psychiatric symptoms are stable, but his functional decline is now largely driven by metabolic parameters. Along with lifestyle changes and nonpharmacologic interventions, what else should you consider to help him?

In addition to positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, schizophrenia is accompanied by disturbances in metabolism,1 inflammatory markers,2 and sleep/wake cycles.3 Current treatment strategies focus on addressing symptoms and functioning, but the metabolic and inflammatory targets that account for significant morbidity and mortality remain largely unaddressed.

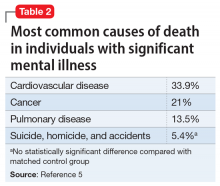

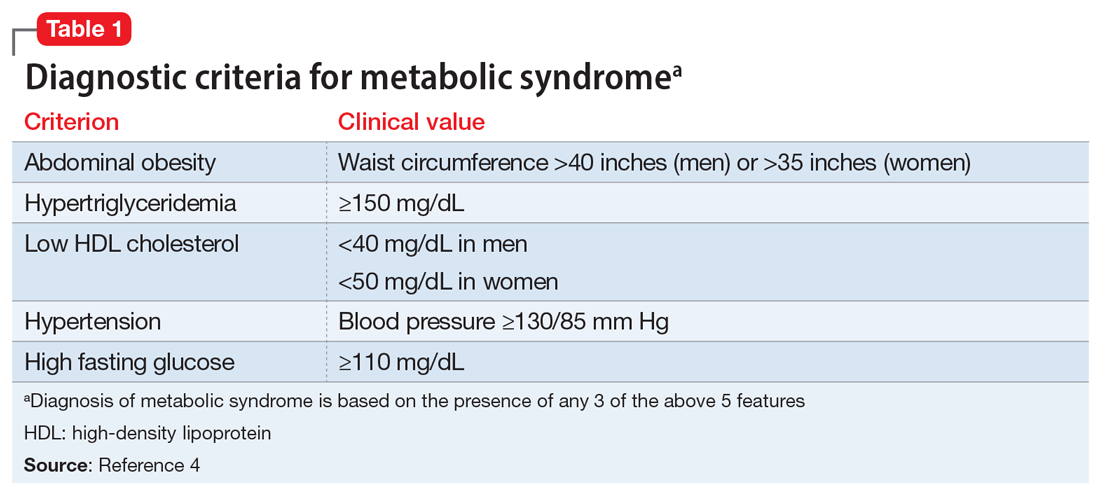

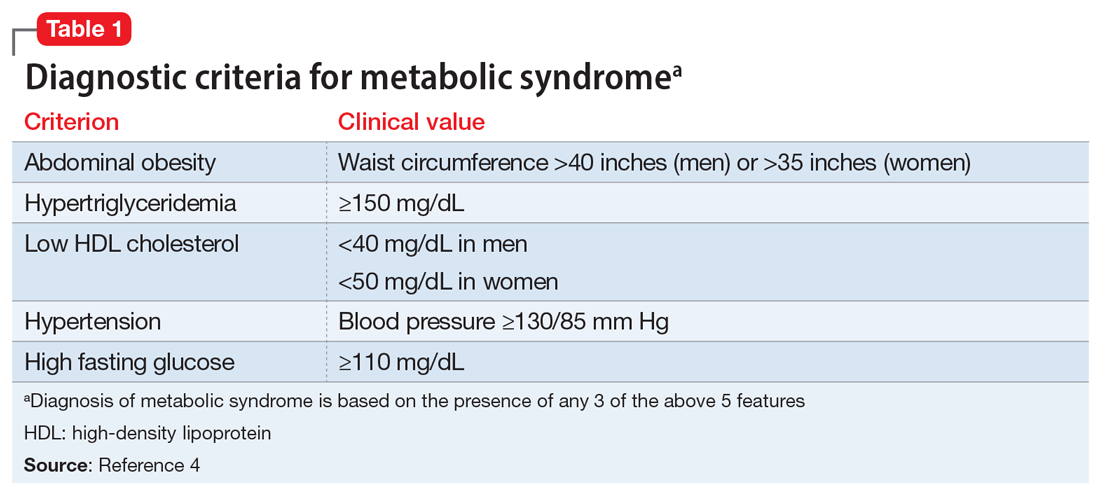

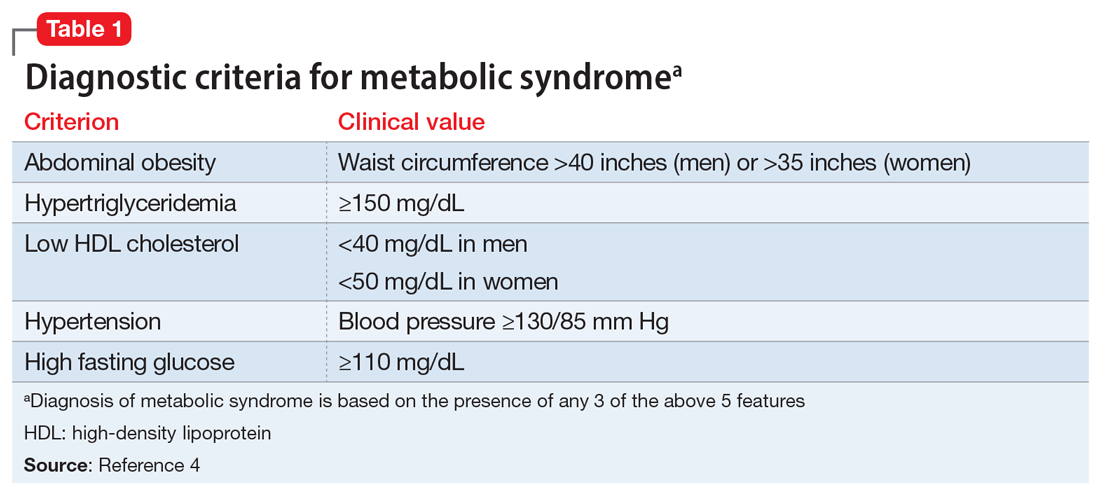

Some patients with schizophrenia meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions—including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Table 14). Metabolic syndrome and its related consequences are a major barrier to the successful treatment of patients with schizophrenia, and lead to increased mortality. Druss et al5 found that individuals with significant mental illness died on average 8.2 years earlier than age-matched controls. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (Table 25).

“Off-label” prescribing has been used in an attempt to delay or treat emerging metabolic syndrome in individuals with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, comprehensive strategies with a uniform application in clinical settings remain elusive. In this article, we review 3 off-label agents—metformin, topiramate, and melatonin—that may be used to address weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia.

Metformin

Metformin is an oral medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It works by decreasing glucose absorption, suppressing gluconeogenesis in the liver, and increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. It was FDA-approved for use in the United States in 1994. In addition to improving glucose homeostasis, metformin has also been associated with decreased body mass index (BMI), triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in individuals at risk for diabetes.6

Recent consensus guidelines suggest that metformin has sufficient evidence to support its clinical use for preventing or treating antipsychotic-induced weight gain.7 A meta-analysis that included >40 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) found that metformin8-11:

- reduces antipsychotic-induced weight gain (approximately 3 kg, up to 5 kg in patients with first-episode psychosis)

- reduces fasting glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c, fasting insulin levels, and insulin resistance

- leads to a more favorable lipid profile (reduced triglycerides, LDL, and total cholesterol, and increased HDL).

Not surprisingly, metformin’s effects are augmented when used in conjunction with lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise), leading to further weight reductions of 1.5 kg and BMI reductions of 1.08 kg/m2 when compared with metformin alone.11 The mechanism underlying metformin’s attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain is not fully understood, but preclinical studies suggest that it may prevent olanzapine-induced brown adipose tissue loss,12,13 alter Wnt signaling (an assortment of signal transduction pathways important for glucose homeostasis and metabolism),13 and influence the gut microbiome.14

Continue to: Metformin is generally...

Metformin is generally well tolerated. Common adverse effects include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain, which are generally transient and can be ameliorated by using the extended-release formulation and lower starting doses.15 The frequency of medication discontinuation was minimal and similar in patients receiving metformin vs placebo.8,16 Despite these positive findings, most studies of metformin have had a follow-up of ≤24 weeks, and its long-term effects on antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic parameters remain unknown.

When prescribing metformin for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 500 mg twice daily.

Topiramate

Topiramate is FDA-approved for treating generalized tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures17 and for migraine prophylaxis. More recently, it has been used off-label for weight loss in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients. Topiramate’s proposed mechanism for weight loss is by decreasing plasma leptin levels and increasing plasma adiponectin. A recent literature review of 8 RCTS that included 336 patients who received second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and adjunctive placebo or topiramate (100 to 300 mg/d) found that patients who received topiramate lost a statistically significant 2.83 kg vs placebo.18 Several case studies confirm similar findings, showing that patients with schizophrenia lost 2 to 5 kg when started on topiramate along with an SGA.19 Importantly, weight loss has been observed both in patients started on topiramate prophylactically along with an SGA, and those who had been receiving SGAs for an extended period of time before starting topiramate.

Tolerability has been a concern in patients receiving topiramate. Frequent complaints include cognitive dulling, sedation, and coldness or tingling of the extremities. In a meta-analysis of topiramate, metformin, and other medications used to induce weight loss in patients receiving SGAs, Zhuo et al20 found that topiramate was reported intolerable more frequently than other agents, although the difference was not statistically significant.

When prescribing topiramate for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 25 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Melatonin

Melatonin

Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that is available over-the-counter and is frequently used to treat insomnia. Melatonin appears to have few adverse effects, is not habit-forming, and is inexpensive. It is a hormone produced primarily by the pineal gland, although it is also produced by many other cell types, including the skin, gut, bone marrow, thymus, and retina.21,22 Melatonin is a highly conserved essential hormone23 that acts via both G protein-coupled membrane bound receptors and nuclear receptors.23-25 Its ability to function both intra- and extracellularly implies it has an essential role in maintaining homeostatic mechanisms. Melatonin’s putative mechanism of action may derive from its effects on circadian rhythms, which in turn affect systolic blood pressure, glycemic control, and oxidative stress. In rodents, pinealectomy led to the rapid development of hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Daily administration of melatonin26 in these animals restored metabolism by decreasing abdominal fat and plasma leptin levels. These studies suggest that melatonin plays a central role in metabolism.

A recent study of patients with first-episode psychosis (n = 48) examined the effects of melatonin (3 mg/d) as an add-on treatment to olanzapine vs placebo.27 Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the melatonin group experienced a statistically significant decrease in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and triglyceride levels.27 In another study, the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon was used in conjunction with SGAs.28 Augmentation with ramelteon led to significantly lower rises in total cholesterol levels compared with placebo.28

When recommending melatonin for a patient with schizophrenia, suggest that he/she begin by taking a starting dose of 3 mg nightly.

Weighing the options

Which medication to prescribe for a patient such as Mr. N would depend on the patient’s specific complaint/health target.

Weight gain or diabetes. If the patient’s primary concerns are avoiding weight gain or the development of diabetes, metformin is an excellent starting point.

Continue to: Migraines or desire to lose weight

Migraines or desire to lose weight. If the patient reports frequent migraines or a history of migraines, or if he/she is interested in weight loss, a trial of topiramate may be appropriate.

Sleep difficulties. If sleep is the patient’s primary concern, then adding melatonin might be a good first choice.

At this point, the available data points to metformin as the most efficacious medication in ameliorating some of the metabolic adverse effects associated with the long-term use of SGAs.8-11 Comprehensive treatment of patients with schizophrenia should include addressing underlying metabolic issues not only to improve health outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality, but also to improve psychosocial functioning and quality of life.

Bottom Line

Preventing or treating metabolic syndrome is an important consideration in all patients with schizophrenia. Metformin, topiramate, and melatonin show some promise in helping ameliorate metabolic syndrome and its associated morbidity and mortality, and also may help improve patients’ functioning and quality of life.

Related Resources

- Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):306-318.

- Majeed MH, Khalil HA. Cardiovascular adverse effects of psychotropics: what to look for. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(7):54-55

- Wake, LA, Balon R. Should psychiatrists prescribe nonpsychotropic medications? Current Psychiatry. 2019; 18(11):52-56.

Drug Brand Names

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Bushe C, Holt R. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;184(suppl 47):S67-S71.

2. Harvey PD. Inflammation in schizophrenia: what it means and how to treat it. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):62-63.

3. Chouinard S, Poulin J, Stip E. Sleep in untreated patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):957-967.

4. Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(5-6):231-237.

5. Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, et al. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599-604.

6. Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Kahn JA, et al. Meta-analysis: metformin treatment in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):149-157.

7. Faulkner G, Duncan M. Metformin to reduce weight gain and metabolic disturbance in schizophrenia. Evid Based Ment Health. 2015;18(3):89.

8. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

9. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1385-1403.

10. Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, et al. Metformin for clozapine associated obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156208.

11. Wu T, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. New insights into the anti-diabetic actions of metformin: from the liver to the gut. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11(2):157-166.

12. Hu Y, Young AJ, Ehli EA, et al. Metformin and berberine prevent olanzapine-induced weight gain in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093310.

13. Li R, Ou J, Li L, et al. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 mediates olanzapine-induced weight gain and insulin resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:379.

14. Luo C, Wang X, Huang H, et al. Effect of metformin on antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysfunction: the potential role of gut-brain axis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:371.

15. Flory JH, Keating SJ, Siscovick D, et al. Identifying prevalence and risk factors for metformin non-persistence: a retrospective cohort study using an electronic health record. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021505.

16. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

17. Maryanoff BE. Phenotypic assessment and the discovery of topiramate. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7(7):662-665.

18. Mahmood S, Booker I, Huang J, et al. Effect of topiramate on weight gain in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):90-94.

19. Lin YH, Liu CY, Hsiao MC. Management of atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain in schizophrenic patients with topiramate. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):613-615.

20. Zhuo C, Xu Y, Liu S, et al. Topiramate and metformin are effective add-on treatments in controlling antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1393.

21. Nduhirabandi F, du Toit EF, Lochner A. Melatonin and the metabolic syndrome: a tool for effective therapy in obesity-associated abnormalities? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2012;205(2):209-223.

22. Srinivasan V, Ohta Y, Espino J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, its pathophysiology and the role of melatonin. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2013;7(1):11-25.

23. Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):313-316.

24. Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan V, et al. Melatonin--a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator molecule. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):350-384.

25. Wiesenberg I, Missbach M, Carlberg C. The potential role of the transcription factor RZR/ROR as a mediator of nuclear melatonin signaling. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1998;12(2-3):143-150.

26. Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, et al. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284(3):F447-F454.

27. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

28. Borba CP, Fan X, Copeland PM, et al. Placebo-controlled pilot study of ramelteon for adiposity and lipids in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):653-658.

Mr. N, age 55, has a long, documented history of schizophrenia. His overall baseline functioning has been poor because he is socially isolated, does not work, and lives in subsidized housing paid for by the county where he lives. His psychosocial circumstances have limited his ability to afford or otherwise obtain nutritious food or participate in any type of regular exercise program. He has been maintained on olanzapine, 20 mg nightly, for the past 5 years. During the past year, his functioning and overall quality of life have declined even further after he was diagnosed with hypertension. Mr. N’s in-office blood pressure was 160/95 mm Hg (normal range: systolic blood pressure, 90 to 120 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure, 60 to 80 mm Hg). He says his primary care physician informed him that he is pre-diabetic after his hemoglobin A1c came back at 6.0 mg/dL (normal range <5.7 mg/dL) and his body mass index was 32 kg/m2 (normal range 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). Currently, Mr. N’s psychiatric symptoms are stable, but his functional decline is now largely driven by metabolic parameters. Along with lifestyle changes and nonpharmacologic interventions, what else should you consider to help him?

In addition to positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, schizophrenia is accompanied by disturbances in metabolism,1 inflammatory markers,2 and sleep/wake cycles.3 Current treatment strategies focus on addressing symptoms and functioning, but the metabolic and inflammatory targets that account for significant morbidity and mortality remain largely unaddressed.

Some patients with schizophrenia meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions—including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Table 14). Metabolic syndrome and its related consequences are a major barrier to the successful treatment of patients with schizophrenia, and lead to increased mortality. Druss et al5 found that individuals with significant mental illness died on average 8.2 years earlier than age-matched controls. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (Table 25).

“Off-label” prescribing has been used in an attempt to delay or treat emerging metabolic syndrome in individuals with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, comprehensive strategies with a uniform application in clinical settings remain elusive. In this article, we review 3 off-label agents—metformin, topiramate, and melatonin—that may be used to address weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia.

Metformin

Metformin is an oral medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It works by decreasing glucose absorption, suppressing gluconeogenesis in the liver, and increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. It was FDA-approved for use in the United States in 1994. In addition to improving glucose homeostasis, metformin has also been associated with decreased body mass index (BMI), triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in individuals at risk for diabetes.6

Recent consensus guidelines suggest that metformin has sufficient evidence to support its clinical use for preventing or treating antipsychotic-induced weight gain.7 A meta-analysis that included >40 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) found that metformin8-11:

- reduces antipsychotic-induced weight gain (approximately 3 kg, up to 5 kg in patients with first-episode psychosis)

- reduces fasting glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c, fasting insulin levels, and insulin resistance

- leads to a more favorable lipid profile (reduced triglycerides, LDL, and total cholesterol, and increased HDL).

Not surprisingly, metformin’s effects are augmented when used in conjunction with lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise), leading to further weight reductions of 1.5 kg and BMI reductions of 1.08 kg/m2 when compared with metformin alone.11 The mechanism underlying metformin’s attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain is not fully understood, but preclinical studies suggest that it may prevent olanzapine-induced brown adipose tissue loss,12,13 alter Wnt signaling (an assortment of signal transduction pathways important for glucose homeostasis and metabolism),13 and influence the gut microbiome.14

Continue to: Metformin is generally...

Metformin is generally well tolerated. Common adverse effects include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain, which are generally transient and can be ameliorated by using the extended-release formulation and lower starting doses.15 The frequency of medication discontinuation was minimal and similar in patients receiving metformin vs placebo.8,16 Despite these positive findings, most studies of metformin have had a follow-up of ≤24 weeks, and its long-term effects on antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic parameters remain unknown.

When prescribing metformin for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 500 mg twice daily.

Topiramate

Topiramate is FDA-approved for treating generalized tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures17 and for migraine prophylaxis. More recently, it has been used off-label for weight loss in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients. Topiramate’s proposed mechanism for weight loss is by decreasing plasma leptin levels and increasing plasma adiponectin. A recent literature review of 8 RCTS that included 336 patients who received second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and adjunctive placebo or topiramate (100 to 300 mg/d) found that patients who received topiramate lost a statistically significant 2.83 kg vs placebo.18 Several case studies confirm similar findings, showing that patients with schizophrenia lost 2 to 5 kg when started on topiramate along with an SGA.19 Importantly, weight loss has been observed both in patients started on topiramate prophylactically along with an SGA, and those who had been receiving SGAs for an extended period of time before starting topiramate.

Tolerability has been a concern in patients receiving topiramate. Frequent complaints include cognitive dulling, sedation, and coldness or tingling of the extremities. In a meta-analysis of topiramate, metformin, and other medications used to induce weight loss in patients receiving SGAs, Zhuo et al20 found that topiramate was reported intolerable more frequently than other agents, although the difference was not statistically significant.

When prescribing topiramate for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 25 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Melatonin

Melatonin

Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that is available over-the-counter and is frequently used to treat insomnia. Melatonin appears to have few adverse effects, is not habit-forming, and is inexpensive. It is a hormone produced primarily by the pineal gland, although it is also produced by many other cell types, including the skin, gut, bone marrow, thymus, and retina.21,22 Melatonin is a highly conserved essential hormone23 that acts via both G protein-coupled membrane bound receptors and nuclear receptors.23-25 Its ability to function both intra- and extracellularly implies it has an essential role in maintaining homeostatic mechanisms. Melatonin’s putative mechanism of action may derive from its effects on circadian rhythms, which in turn affect systolic blood pressure, glycemic control, and oxidative stress. In rodents, pinealectomy led to the rapid development of hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Daily administration of melatonin26 in these animals restored metabolism by decreasing abdominal fat and plasma leptin levels. These studies suggest that melatonin plays a central role in metabolism.

A recent study of patients with first-episode psychosis (n = 48) examined the effects of melatonin (3 mg/d) as an add-on treatment to olanzapine vs placebo.27 Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the melatonin group experienced a statistically significant decrease in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and triglyceride levels.27 In another study, the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon was used in conjunction with SGAs.28 Augmentation with ramelteon led to significantly lower rises in total cholesterol levels compared with placebo.28

When recommending melatonin for a patient with schizophrenia, suggest that he/she begin by taking a starting dose of 3 mg nightly.

Weighing the options

Which medication to prescribe for a patient such as Mr. N would depend on the patient’s specific complaint/health target.

Weight gain or diabetes. If the patient’s primary concerns are avoiding weight gain or the development of diabetes, metformin is an excellent starting point.

Continue to: Migraines or desire to lose weight

Migraines or desire to lose weight. If the patient reports frequent migraines or a history of migraines, or if he/she is interested in weight loss, a trial of topiramate may be appropriate.

Sleep difficulties. If sleep is the patient’s primary concern, then adding melatonin might be a good first choice.

At this point, the available data points to metformin as the most efficacious medication in ameliorating some of the metabolic adverse effects associated with the long-term use of SGAs.8-11 Comprehensive treatment of patients with schizophrenia should include addressing underlying metabolic issues not only to improve health outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality, but also to improve psychosocial functioning and quality of life.

Bottom Line

Preventing or treating metabolic syndrome is an important consideration in all patients with schizophrenia. Metformin, topiramate, and melatonin show some promise in helping ameliorate metabolic syndrome and its associated morbidity and mortality, and also may help improve patients’ functioning and quality of life.

Related Resources

- Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):306-318.

- Majeed MH, Khalil HA. Cardiovascular adverse effects of psychotropics: what to look for. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(7):54-55

- Wake, LA, Balon R. Should psychiatrists prescribe nonpsychotropic medications? Current Psychiatry. 2019; 18(11):52-56.

Drug Brand Names

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Topiramate • Topamax

Mr. N, age 55, has a long, documented history of schizophrenia. His overall baseline functioning has been poor because he is socially isolated, does not work, and lives in subsidized housing paid for by the county where he lives. His psychosocial circumstances have limited his ability to afford or otherwise obtain nutritious food or participate in any type of regular exercise program. He has been maintained on olanzapine, 20 mg nightly, for the past 5 years. During the past year, his functioning and overall quality of life have declined even further after he was diagnosed with hypertension. Mr. N’s in-office blood pressure was 160/95 mm Hg (normal range: systolic blood pressure, 90 to 120 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure, 60 to 80 mm Hg). He says his primary care physician informed him that he is pre-diabetic after his hemoglobin A1c came back at 6.0 mg/dL (normal range <5.7 mg/dL) and his body mass index was 32 kg/m2 (normal range 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2). Currently, Mr. N’s psychiatric symptoms are stable, but his functional decline is now largely driven by metabolic parameters. Along with lifestyle changes and nonpharmacologic interventions, what else should you consider to help him?

In addition to positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms, schizophrenia is accompanied by disturbances in metabolism,1 inflammatory markers,2 and sleep/wake cycles.3 Current treatment strategies focus on addressing symptoms and functioning, but the metabolic and inflammatory targets that account for significant morbidity and mortality remain largely unaddressed.

Some patients with schizophrenia meet the criteria for metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions—including obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hypertension—that increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Table 14). Metabolic syndrome and its related consequences are a major barrier to the successful treatment of patients with schizophrenia, and lead to increased mortality. Druss et al5 found that individuals with significant mental illness died on average 8.2 years earlier than age-matched controls. The most common cause of death was cardiovascular disease (Table 25).

“Off-label” prescribing has been used in an attempt to delay or treat emerging metabolic syndrome in individuals with schizophrenia. Unfortunately, comprehensive strategies with a uniform application in clinical settings remain elusive. In this article, we review 3 off-label agents—metformin, topiramate, and melatonin—that may be used to address weight gain and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia.

Metformin

Metformin is an oral medication used to treat type 2 diabetes. It works by decreasing glucose absorption, suppressing gluconeogenesis in the liver, and increasing insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. It was FDA-approved for use in the United States in 1994. In addition to improving glucose homeostasis, metformin has also been associated with decreased body mass index (BMI), triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol in individuals at risk for diabetes.6

Recent consensus guidelines suggest that metformin has sufficient evidence to support its clinical use for preventing or treating antipsychotic-induced weight gain.7 A meta-analysis that included >40 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) found that metformin8-11:

- reduces antipsychotic-induced weight gain (approximately 3 kg, up to 5 kg in patients with first-episode psychosis)

- reduces fasting glucose levels, hemoglobin A1c, fasting insulin levels, and insulin resistance

- leads to a more favorable lipid profile (reduced triglycerides, LDL, and total cholesterol, and increased HDL).

Not surprisingly, metformin’s effects are augmented when used in conjunction with lifestyle interventions (diet and exercise), leading to further weight reductions of 1.5 kg and BMI reductions of 1.08 kg/m2 when compared with metformin alone.11 The mechanism underlying metformin’s attenuation of antipsychotic-induced weight gain is not fully understood, but preclinical studies suggest that it may prevent olanzapine-induced brown adipose tissue loss,12,13 alter Wnt signaling (an assortment of signal transduction pathways important for glucose homeostasis and metabolism),13 and influence the gut microbiome.14

Continue to: Metformin is generally...

Metformin is generally well tolerated. Common adverse effects include diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain, which are generally transient and can be ameliorated by using the extended-release formulation and lower starting doses.15 The frequency of medication discontinuation was minimal and similar in patients receiving metformin vs placebo.8,16 Despite these positive findings, most studies of metformin have had a follow-up of ≤24 weeks, and its long-term effects on antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic parameters remain unknown.

When prescribing metformin for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 500 mg twice daily.

Topiramate

Topiramate is FDA-approved for treating generalized tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures17 and for migraine prophylaxis. More recently, it has been used off-label for weight loss in both psychiatric and non-psychiatric patients. Topiramate’s proposed mechanism for weight loss is by decreasing plasma leptin levels and increasing plasma adiponectin. A recent literature review of 8 RCTS that included 336 patients who received second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and adjunctive placebo or topiramate (100 to 300 mg/d) found that patients who received topiramate lost a statistically significant 2.83 kg vs placebo.18 Several case studies confirm similar findings, showing that patients with schizophrenia lost 2 to 5 kg when started on topiramate along with an SGA.19 Importantly, weight loss has been observed both in patients started on topiramate prophylactically along with an SGA, and those who had been receiving SGAs for an extended period of time before starting topiramate.

Tolerability has been a concern in patients receiving topiramate. Frequent complaints include cognitive dulling, sedation, and coldness or tingling of the extremities. In a meta-analysis of topiramate, metformin, and other medications used to induce weight loss in patients receiving SGAs, Zhuo et al20 found that topiramate was reported intolerable more frequently than other agents, although the difference was not statistically significant.

When prescribing topiramate for a patient with schizophrenia, consider a starting dose of 25 mg at bedtime.

Continue to: Melatonin

Melatonin

Melatonin is a naturally occurring hormone that is available over-the-counter and is frequently used to treat insomnia. Melatonin appears to have few adverse effects, is not habit-forming, and is inexpensive. It is a hormone produced primarily by the pineal gland, although it is also produced by many other cell types, including the skin, gut, bone marrow, thymus, and retina.21,22 Melatonin is a highly conserved essential hormone23 that acts via both G protein-coupled membrane bound receptors and nuclear receptors.23-25 Its ability to function both intra- and extracellularly implies it has an essential role in maintaining homeostatic mechanisms. Melatonin’s putative mechanism of action may derive from its effects on circadian rhythms, which in turn affect systolic blood pressure, glycemic control, and oxidative stress. In rodents, pinealectomy led to the rapid development of hypertension and metabolic syndrome. Daily administration of melatonin26 in these animals restored metabolism by decreasing abdominal fat and plasma leptin levels. These studies suggest that melatonin plays a central role in metabolism.

A recent study of patients with first-episode psychosis (n = 48) examined the effects of melatonin (3 mg/d) as an add-on treatment to olanzapine vs placebo.27 Compared with those in the placebo group, participants in the melatonin group experienced a statistically significant decrease in body weight, BMI, waist circumference, and triglyceride levels.27 In another study, the melatonin receptor agonist ramelteon was used in conjunction with SGAs.28 Augmentation with ramelteon led to significantly lower rises in total cholesterol levels compared with placebo.28

When recommending melatonin for a patient with schizophrenia, suggest that he/she begin by taking a starting dose of 3 mg nightly.

Weighing the options

Which medication to prescribe for a patient such as Mr. N would depend on the patient’s specific complaint/health target.

Weight gain or diabetes. If the patient’s primary concerns are avoiding weight gain or the development of diabetes, metformin is an excellent starting point.

Continue to: Migraines or desire to lose weight

Migraines or desire to lose weight. If the patient reports frequent migraines or a history of migraines, or if he/she is interested in weight loss, a trial of topiramate may be appropriate.

Sleep difficulties. If sleep is the patient’s primary concern, then adding melatonin might be a good first choice.

At this point, the available data points to metformin as the most efficacious medication in ameliorating some of the metabolic adverse effects associated with the long-term use of SGAs.8-11 Comprehensive treatment of patients with schizophrenia should include addressing underlying metabolic issues not only to improve health outcomes and reduce morbidity and mortality, but also to improve psychosocial functioning and quality of life.

Bottom Line

Preventing or treating metabolic syndrome is an important consideration in all patients with schizophrenia. Metformin, topiramate, and melatonin show some promise in helping ameliorate metabolic syndrome and its associated morbidity and mortality, and also may help improve patients’ functioning and quality of life.

Related Resources

- Mitchell AJ, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(2):306-318.

- Majeed MH, Khalil HA. Cardiovascular adverse effects of psychotropics: what to look for. Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(7):54-55

- Wake, LA, Balon R. Should psychiatrists prescribe nonpsychotropic medications? Current Psychiatry. 2019; 18(11):52-56.

Drug Brand Names

Metformin • Glucophage

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Bushe C, Holt R. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;184(suppl 47):S67-S71.

2. Harvey PD. Inflammation in schizophrenia: what it means and how to treat it. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):62-63.

3. Chouinard S, Poulin J, Stip E. Sleep in untreated patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):957-967.

4. Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(5-6):231-237.

5. Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, et al. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599-604.

6. Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Kahn JA, et al. Meta-analysis: metformin treatment in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):149-157.

7. Faulkner G, Duncan M. Metformin to reduce weight gain and metabolic disturbance in schizophrenia. Evid Based Ment Health. 2015;18(3):89.

8. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

9. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1385-1403.

10. Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, et al. Metformin for clozapine associated obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156208.

11. Wu T, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. New insights into the anti-diabetic actions of metformin: from the liver to the gut. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11(2):157-166.

12. Hu Y, Young AJ, Ehli EA, et al. Metformin and berberine prevent olanzapine-induced weight gain in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093310.

13. Li R, Ou J, Li L, et al. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 mediates olanzapine-induced weight gain and insulin resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:379.

14. Luo C, Wang X, Huang H, et al. Effect of metformin on antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysfunction: the potential role of gut-brain axis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:371.

15. Flory JH, Keating SJ, Siscovick D, et al. Identifying prevalence and risk factors for metformin non-persistence: a retrospective cohort study using an electronic health record. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021505.

16. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

17. Maryanoff BE. Phenotypic assessment and the discovery of topiramate. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7(7):662-665.

18. Mahmood S, Booker I, Huang J, et al. Effect of topiramate on weight gain in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):90-94.

19. Lin YH, Liu CY, Hsiao MC. Management of atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain in schizophrenic patients with topiramate. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):613-615.

20. Zhuo C, Xu Y, Liu S, et al. Topiramate and metformin are effective add-on treatments in controlling antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1393.

21. Nduhirabandi F, du Toit EF, Lochner A. Melatonin and the metabolic syndrome: a tool for effective therapy in obesity-associated abnormalities? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2012;205(2):209-223.

22. Srinivasan V, Ohta Y, Espino J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, its pathophysiology and the role of melatonin. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2013;7(1):11-25.

23. Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):313-316.

24. Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan V, et al. Melatonin--a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator molecule. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):350-384.

25. Wiesenberg I, Missbach M, Carlberg C. The potential role of the transcription factor RZR/ROR as a mediator of nuclear melatonin signaling. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1998;12(2-3):143-150.

26. Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, et al. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284(3):F447-F454.

27. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

28. Borba CP, Fan X, Copeland PM, et al. Placebo-controlled pilot study of ramelteon for adiposity and lipids in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):653-658.

1. Bushe C, Holt R. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in patients with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2004;184(suppl 47):S67-S71.

2. Harvey PD. Inflammation in schizophrenia: what it means and how to treat it. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;25(1):62-63.

3. Chouinard S, Poulin J, Stip E. Sleep in untreated patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(4):957-967.

4. Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Dis Model Mech. 2009;2(5-6):231-237.

5. Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, et al. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49(6):599-604.

6. Salpeter SR, Buckley NS, Kahn JA, et al. Meta-analysis: metformin treatment in persons at risk for diabetes mellitus. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):149-157.

7. Faulkner G, Duncan M. Metformin to reduce weight gain and metabolic disturbance in schizophrenia. Evid Based Ment Health. 2015;18(3):89.

8. Jarskog LF, Hamer RM, Catellier DJ, et al. Metformin for weight loss and metabolic control in overweight outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1032-1040.

9. Mizuno Y, Suzuki T, Nakagawa A, et al. Pharmacological strategies to counteract antipsychotic-induced weight gain and metabolic adverse effects in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(6):1385-1403.

10. Siskind DJ, Leung J, Russell AW, et al. Metformin for clozapine associated obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0156208. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156208.

11. Wu T, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. New insights into the anti-diabetic actions of metformin: from the liver to the gut. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11(2):157-166.

12. Hu Y, Young AJ, Ehli EA, et al. Metformin and berberine prevent olanzapine-induced weight gain in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e93310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093310.

13. Li R, Ou J, Li L, et al. The Wnt signaling pathway effector TCF7L2 mediates olanzapine-induced weight gain and insulin resistance. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:379.

14. Luo C, Wang X, Huang H, et al. Effect of metformin on antipsychotic-induced metabolic dysfunction: the potential role of gut-brain axis. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:371.

15. Flory JH, Keating SJ, Siscovick D, et al. Identifying prevalence and risk factors for metformin non-persistence: a retrospective cohort study using an electronic health record. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e021505. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021505.

16. Wang M, Tong JH, Zhu G, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2012;138(1):54-57.

17. Maryanoff BE. Phenotypic assessment and the discovery of topiramate. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2016;7(7):662-665.

18. Mahmood S, Booker I, Huang J, et al. Effect of topiramate on weight gain in patients receiving atypical antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(1):90-94.

19. Lin YH, Liu CY, Hsiao MC. Management of atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain in schizophrenic patients with topiramate. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):613-615.

20. Zhuo C, Xu Y, Liu S, et al. Topiramate and metformin are effective add-on treatments in controlling antipsychotic-induced weight gain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:1393.

21. Nduhirabandi F, du Toit EF, Lochner A. Melatonin and the metabolic syndrome: a tool for effective therapy in obesity-associated abnormalities? Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2012;205(2):209-223.

22. Srinivasan V, Ohta Y, Espino J, et al. Metabolic syndrome, its pathophysiology and the role of melatonin. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov. 2013;7(1):11-25.

23. Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):313-316.

24. Hardeland R, Cardinali DP, Srinivasan V, et al. Melatonin--a pleiotropic, orchestrating regulator molecule. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;93(3):350-384.

25. Wiesenberg I, Missbach M, Carlberg C. The potential role of the transcription factor RZR/ROR as a mediator of nuclear melatonin signaling. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1998;12(2-3):143-150.

26. Nava M, Quiroz Y, Vaziri N, et al. Melatonin reduces renal interstitial inflammation and improves hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2003;284(3):F447-F454.

27. Modabbernia A, Heidari P, Soleimani R, et al. Melatonin for prevention of metabolic side-effects of olanzapine in patients with first-episode schizophrenia: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;53:133-140.

28. Borba CP, Fan X, Copeland PM, et al. Placebo-controlled pilot study of ramelteon for adiposity and lipids in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):653-658.

What the Biden-Harris COVID-19 Advisory Board is missing

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply

The mental health system we have now is inadequate for those who are currently diagnosed with mental disorders. Before the pandemic, emergency departments were boarding increasing numbers of patients with psychiatric illness because beds on inpatient units were unavailable. Individuals with insurance faced difficulty finding psychiatrists or psychotherapists who took insurance or who were availabile to accept new patients, given the growing shortage of providers in general. Community health centers continued to grapple with decreases in federal and state funding despite public political support for parity. Individuals with substance use faced few options for the outpatient, residential, or pharmacologic treatment that many needed to maintain sobriety.

Since the pandemic, we have seen rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thinking increase among adults and youth while many clinics have been forced to lay off employees, reduce services, or close their doors. As psychiatrists, we not only see the lack of treatment options for our patients but are forced to find creative solutions to meet their needs. How are we supposed to adapt (or feel confident) when individuals with or without previous mental illness face downstream consequences after COVID-19 when not one of our own is represented in the advisory board? How can we feel confident that downstream solutions acknowledge and address the intricacy of the behavioral health system that we, as mental health providers, know so intimately?

And what about the cumulative impact of everything else that has happened in 2020 in addition to the pandemic?! Although cataloging the various negative events that have happened this year is beyond the scope of this discussion, such lists have been compiled by the mainstream media and include the Australian brush fires, the crisis in Armenia, racial protests, economic uncertainties, and the run-up to and occurrence of the 2020 presidential election. Research is solid in its assertion that chronic stress can disturb our immune and cardiovascular systems, as well as mental health, leading to depression or anxiety. As a result of the pandemic itself, plus the events of this year, mental health providers are already warning not only of the current trauma underlying our day-to-day lives but also that of years to come.

More importantly, healthcare providers, both those represented by members of the advisory board and those who are not, are not immune to these issues. Before the pandemic, rates of suicide among doctors were already above average compared with other professions. After witnessing death repeatedly, self-isolation, the risk for infection to family, and dealing with the continued resistance to wearing masks, who knows what the eventual psychological toll our medical workforce will be?

Mental health providers have stepped up to the plate to provide care outside of traditional models to meet the needs that patients have now. One survey found that 81% of behavioral health providers began using telehealth for the first time in the past 6 months, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. If not for the sake of the mental health of the Biden-Harris advisory board members themselves, who as doctors are likely to downplay the impact when struggling with mental health concerns in their own lives, a mental health provider deserves a seat at the table.

Plus, the outcomes speak for themselves when behavioral health providers collaborate with primary care providers to give treatment or when mental health experts are members of health crisis teams. Why wouldn’t the same be true for the Biden-Harris advisory board?

Kali Cyrus, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. She sees patients in private practice and offers consultation services in diversity strategy. Ranna Parekh, MD, MPH, is past deputy medical director and director of diversity and health equity for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently a consultant psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the chief diversity and inclusion officer at the American College of Cardiology.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply

The mental health system we have now is inadequate for those who are currently diagnosed with mental disorders. Before the pandemic, emergency departments were boarding increasing numbers of patients with psychiatric illness because beds on inpatient units were unavailable. Individuals with insurance faced difficulty finding psychiatrists or psychotherapists who took insurance or who were availabile to accept new patients, given the growing shortage of providers in general. Community health centers continued to grapple with decreases in federal and state funding despite public political support for parity. Individuals with substance use faced few options for the outpatient, residential, or pharmacologic treatment that many needed to maintain sobriety.

Since the pandemic, we have seen rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thinking increase among adults and youth while many clinics have been forced to lay off employees, reduce services, or close their doors. As psychiatrists, we not only see the lack of treatment options for our patients but are forced to find creative solutions to meet their needs. How are we supposed to adapt (or feel confident) when individuals with or without previous mental illness face downstream consequences after COVID-19 when not one of our own is represented in the advisory board? How can we feel confident that downstream solutions acknowledge and address the intricacy of the behavioral health system that we, as mental health providers, know so intimately?

And what about the cumulative impact of everything else that has happened in 2020 in addition to the pandemic?! Although cataloging the various negative events that have happened this year is beyond the scope of this discussion, such lists have been compiled by the mainstream media and include the Australian brush fires, the crisis in Armenia, racial protests, economic uncertainties, and the run-up to and occurrence of the 2020 presidential election. Research is solid in its assertion that chronic stress can disturb our immune and cardiovascular systems, as well as mental health, leading to depression or anxiety. As a result of the pandemic itself, plus the events of this year, mental health providers are already warning not only of the current trauma underlying our day-to-day lives but also that of years to come.

More importantly, healthcare providers, both those represented by members of the advisory board and those who are not, are not immune to these issues. Before the pandemic, rates of suicide among doctors were already above average compared with other professions. After witnessing death repeatedly, self-isolation, the risk for infection to family, and dealing with the continued resistance to wearing masks, who knows what the eventual psychological toll our medical workforce will be?

Mental health providers have stepped up to the plate to provide care outside of traditional models to meet the needs that patients have now. One survey found that 81% of behavioral health providers began using telehealth for the first time in the past 6 months, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. If not for the sake of the mental health of the Biden-Harris advisory board members themselves, who as doctors are likely to downplay the impact when struggling with mental health concerns in their own lives, a mental health provider deserves a seat at the table.

Plus, the outcomes speak for themselves when behavioral health providers collaborate with primary care providers to give treatment or when mental health experts are members of health crisis teams. Why wouldn’t the same be true for the Biden-Harris advisory board?

Kali Cyrus, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. She sees patients in private practice and offers consultation services in diversity strategy. Ranna Parekh, MD, MPH, is past deputy medical director and director of diversity and health equity for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently a consultant psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the chief diversity and inclusion officer at the American College of Cardiology.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

On Nov. 9, the Biden-Harris administration announced the members of its COVID-19 Advisory Board. Among them were many esteemed infectious disease and public health experts – encouraging, given that, for now, the COVID-19 pandemic shows no signs of slowing down. Not among them was a mental health professional.

As psychiatrists, we did not find this omission surprising, given the sidelined role our specialty too often plays among medical professionals. But we did find it disappointing. Not having a single behavioral health provider on the advisory board will prove to be a mistake that could affect millions of Americans.

Studies continue to roll in showing that patients with COVID-19 can present during and after infection with neuropsychiatric symptoms, including delirium, psychosis, and anxiety. In July, a meta-analysis published in The Lancet regarding the neuropsychological outcomes of earlier diseases caused by coronaviruses – severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome – suggested that, in the short term, close to one-quarter of patients experienced confusion representative of delirium. In the long term, following recovery, respondents frequently reported emotional lability, impaired concentration, and traumatic memories. Additionally, more recent research published in The Lancet suggests that rates of psychiatric disorders, dementia, and insomnia are significantly higher among survivors of COVID-19. This study echoes the findings of an article in JAMA from September that reported that, among patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19, mortality rates were higher for those who had previously been diagnosed with a psychiatric condition. And overall, the pandemic has been associated with significantly increased rates of anxiety and depression symptoms.

Although this research is preliminary,

This is especially true when you consider the following:

- It is very difficult to diagnose and treat mental health symptoms in a primary care setting that is already overburdened. Doing so results in delayed treatment and increased costs.

- In the long term, COVID-19 survivors will overburden the already underfunded mental healthcare system.

- Additional unforeseen psychological outcomes stem from the myriad traumas of events in 2020 (eg, racial unrest, children out of school, loss of jobs, the recent election).

Psychiatric disorders are notoriously difficult to diagnose and treat in the outpatient primary care setting, which is why mental health professionals will need to be a more integral part of the postpandemic treatment model and should be represented on the advisory board. Each year in the United States, there are more than 8 million doctors’ visits for depression, and more than half of these are in the primary care setting. Yet fewer than half of those patients leave with a diagnosis of depression or are treated for it.

Historically, screening for depression in the primary care setting is difficult given its broad presentation of symptoms, which include nonspecific physical complaints, such as digestive problems, headaches, insomnia, or general aches and pains. These shortcomings exist despite multiple changes in guidelines, such as regarding the use of self-screening tools and general screening for specific populations, such as postpartum women.

But screening alone has not been an effective strategy, especially when certain groups are less likely to be screened. These include older adults, Black persons, and men, all of whom are at higher risk for mortality after COVID-19. There is a failure to consistently apply standards of universal screening across all patient groups, and even if it occurs, there is a failure to establish reliable treatment and follow-up regimens. As clinicians, imagine how challenging diagnosis and treatment of more complicated psychiatric syndromes, such as somatoform disorder, will be in the primary care setting after the pandemic.

When almost two-thirds of symptoms in primary care are already “medically unexplained,” how do we expect primary care doctors to differentiate between those presenting with vague coronavirus-related “brain fog,” the run of the mill worrywart, and the 16%-34% with legitimate hypochondriasis of somatoform disorder who won’t improve without the involvement of a mental health provider?

A specialty in short supply

The mental health system we have now is inadequate for those who are currently diagnosed with mental disorders. Before the pandemic, emergency departments were boarding increasing numbers of patients with psychiatric illness because beds on inpatient units were unavailable. Individuals with insurance faced difficulty finding psychiatrists or psychotherapists who took insurance or who were availabile to accept new patients, given the growing shortage of providers in general. Community health centers continued to grapple with decreases in federal and state funding despite public political support for parity. Individuals with substance use faced few options for the outpatient, residential, or pharmacologic treatment that many needed to maintain sobriety.

Since the pandemic, we have seen rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal thinking increase among adults and youth while many clinics have been forced to lay off employees, reduce services, or close their doors. As psychiatrists, we not only see the lack of treatment options for our patients but are forced to find creative solutions to meet their needs. How are we supposed to adapt (or feel confident) when individuals with or without previous mental illness face downstream consequences after COVID-19 when not one of our own is represented in the advisory board? How can we feel confident that downstream solutions acknowledge and address the intricacy of the behavioral health system that we, as mental health providers, know so intimately?

And what about the cumulative impact of everything else that has happened in 2020 in addition to the pandemic?! Although cataloging the various negative events that have happened this year is beyond the scope of this discussion, such lists have been compiled by the mainstream media and include the Australian brush fires, the crisis in Armenia, racial protests, economic uncertainties, and the run-up to and occurrence of the 2020 presidential election. Research is solid in its assertion that chronic stress can disturb our immune and cardiovascular systems, as well as mental health, leading to depression or anxiety. As a result of the pandemic itself, plus the events of this year, mental health providers are already warning not only of the current trauma underlying our day-to-day lives but also that of years to come.

More importantly, healthcare providers, both those represented by members of the advisory board and those who are not, are not immune to these issues. Before the pandemic, rates of suicide among doctors were already above average compared with other professions. After witnessing death repeatedly, self-isolation, the risk for infection to family, and dealing with the continued resistance to wearing masks, who knows what the eventual psychological toll our medical workforce will be?

Mental health providers have stepped up to the plate to provide care outside of traditional models to meet the needs that patients have now. One survey found that 81% of behavioral health providers began using telehealth for the first time in the past 6 months, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. If not for the sake of the mental health of the Biden-Harris advisory board members themselves, who as doctors are likely to downplay the impact when struggling with mental health concerns in their own lives, a mental health provider deserves a seat at the table.

Plus, the outcomes speak for themselves when behavioral health providers collaborate with primary care providers to give treatment or when mental health experts are members of health crisis teams. Why wouldn’t the same be true for the Biden-Harris advisory board?

Kali Cyrus, MD, MPH, is an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland. She sees patients in private practice and offers consultation services in diversity strategy. Ranna Parekh, MD, MPH, is past deputy medical director and director of diversity and health equity for the American Psychiatric Association. She is currently a consultant psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and the chief diversity and inclusion officer at the American College of Cardiology.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Moderna filing for FDA emergency COVID-19 vaccine approval, reports 94.1% efficacy

The Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in development was 94.1% effective in the final analysis of its 30,000-participant phase 3 study. Bolstered by the new findings, the company plans to file for an emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today, according to a company release.

A total of 11 people in the mRNA-1273 vaccinated group later tested positive for COVID-19, compared with 185 participants given two placebo injections, resulting in a point estimate of 94.1% efficacy. This finding aligns with the 94.5% efficacy in interim trial results announced on November 16, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Furthermore, Moderna announced that the vaccine prevented serious cases of infection. All 30 severe infections occurred among those people randomly assigned to placebo.

The FDA plans to review the Moderna vaccine safety and efficacy data at the next Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting scheduled for December 17. If and when approved, healthcare providers can use the new 91301 CPT code specific to mRNA-1273 vaccination.

“This positive primary analysis confirms the ability of our vaccine to prevent COVID-19 disease with 94.1% efficacy and, importantly, the ability to prevent severe COVID-19 disease,” said Stéphane Bancel, MBA, MEng, chief executive officer of Moderna, in the news release. “We believe that our vaccine will provide a new and powerful tool that may change the course of this pandemic and help prevent severe disease, hospitalizations, and death.”

Vaccine efficacy remained consistent across different groups analyzed by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. The 196 COVID-19 cases in the trial included 33 adults older than 65 years and 42 people from diverse communities, including 29 Hispanic or Latinx, six Black or African Americans, four Asian Americans, and three multiracial participants, the company reported.

No serious vaccine-related safety issues

The mRNA-1273 vaccine was generally well tolerated and no serious safety concerns with the vaccine have been identified to date, the company reported.

Injection site pain, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, headache, and erythema/redness at the injection site were the most common solicited adverse events in a prior analysis. The company noted that these solicited adverse reactions increased in frequency and severity after the second vaccine dose. A continuous review of safety data is ongoing.

One COVID-19-related death in the study occurred in the placebo group.

Ready to start shipping

Moderna expects to have approximately 20 million doses of mRNA-1273 available in the United States by the end of this year. The company reports that it’s on track to manufacture 500 million to 1 billion doses globally in 2021.

The company also is seeking approval from nations and organizations worldwide, including a conditional approval from the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The study is being conducted in collaboration with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA), part of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response at the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Moderna will be the second company to file an EUA with the FDA for a COVID vaccine, after Pfizer requested one for its mRNA vaccine earlier this month.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Moderna COVID-19 vaccine in development was 94.1% effective in the final analysis of its 30,000-participant phase 3 study. Bolstered by the new findings, the company plans to file for an emergency use authorization (EUA) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) today, according to a company release.

A total of 11 people in the mRNA-1273 vaccinated group later tested positive for COVID-19, compared with 185 participants given two placebo injections, resulting in a point estimate of 94.1% efficacy. This finding aligns with the 94.5% efficacy in interim trial results announced on November 16, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Furthermore, Moderna announced that the vaccine prevented serious cases of infection. All 30 severe infections occurred among those people randomly assigned to placebo.

The FDA plans to review the Moderna vaccine safety and efficacy data at the next Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) meeting scheduled for December 17. If and when approved, healthcare providers can use the new 91301 CPT code specific to mRNA-1273 vaccination.

“This positive primary analysis confirms the ability of our vaccine to prevent COVID-19 disease with 94.1% efficacy and, importantly, the ability to prevent severe COVID-19 disease,” said Stéphane Bancel, MBA, MEng, chief executive officer of Moderna, in the news release. “We believe that our vaccine will provide a new and powerful tool that may change the course of this pandemic and help prevent severe disease, hospitalizations, and death.”

Vaccine efficacy remained consistent across different groups analyzed by age, race/ethnicity, and gender. The 196 COVID-19 cases in the trial included 33 adults older than 65 years and 42 people from diverse communities, including 29 Hispanic or Latinx, six Black or African Americans, four Asian Americans, and three multiracial participants, the company reported.

No serious vaccine-related safety issues