User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

CDC expert answers top COVID-19 questions

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

With new developments daily and lingering uncertainty about COVID-19, questions about testing and treatment for the coronavirus are at the forefront.

To address these top questions, Jay C. Butler, MD, deputy director for infectious diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sat down with JAMA editor Howard Bauchner, MD, to discuss the latest data on COVID-19 and to outline updated guidance from the agency. The following question-and-answer session was part of a live stream interview hosted by JAMA on March 16, 2020. The questions have been edited for length and clarity.

What test is being used to identify COVID-19?

In the United States, the most common and widely available test is the RT-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR), which over the past few weeks has become available at public health labs across the country, Dr. Butler said during the JAMA interview. Capacity for the test is now possible in all 50 states and in Washington, D.C.

“More recently, there’s been a number of commercial labs that have come online to be able to do the testing,” Dr. Butler said. “Additionally, a number of academic centers are now able to run [Food and Drug Administration]–approved testing using slightly different PCR platforms.”

How accurate is the test?

Dr. Butler called PCR the “gold standard,” for testing COVID-19, and said it’s safe to say the test’s likelihood of identifying infection or past infection is extremely high. However, data on test sensitivity is limited.

“This may be frustrating to those of us who really like to know specifics of how to interpret the test results, but it’s important to keep in mind, we’re talking about a virus that we didn’t know existed 3 months ago,” he said.

At what point does a person with coronavirus test positive?

When exactly a test becomes positive is an unknown, Dr. Butler said. The assumption is that a patient who tests positive is more likely to be infectious, and data suggest the level of infectiousness is greatest after the onset of symptoms.

“There is at least some anecdotal reports that suggest that transmission could occur before onset of symptoms, but the data is still very limited,” he said. “Of course that has big implications in terms of how well we can really slow the spread of the virus.”

Who should get tested?

Dr. Butler said the focus should be individuals who are symptomatic with evidence of respiratory tract infection. People who are concerned about the virus and want a test are not the target.

“It’s important when talking to patients to help them to understand, this is different than a test for HIV or hepatitis C, where much of the message is: ‘Please get tested.’ ” he said. “This a situation where we’re trying to diagnose an acute infection. We do have a resource that may become limited again as some of the equipment required for running the test or collecting the specimen may come into short supply, so we want to focus on those people who are symptomatic and particularly on people who may be at higher risk of more severe illness.”

If a previously infected patient tests negative, can they still shed virus?

The CDC is currently analyzing how a negative PCR test relates to viral load, according to Dr. Butler. He added there have been situations in which a patient has twice tested negative for the virus, but a third swab resulted in a weakly positive result.

“It’s not clear if those are people who are actually infectious,” he said. “The PCR is detecting viral RNA, it doesn’t necessarily indicate there is viable virus present in the respiratory tract. So in general, I think it is safe to go back to work, but a positive test in a situation like that can be very difficult to interpret because we think it probably doesn’t reflect infectivity, but we don’t know for sure.”

Do we have an adequate supply of tests in the United States?

The CDC has addressed supply concerns by broadening the number of PCR platforms that can be used to run COVID-19 analyses, Dr. Butler said. Expansion of these platforms has been one way the government is furthering testing options and enabling consumer labs and academic centers to contribute to testing.

When can people who test positive go back to work?

The CDC is still researching that question and reviewing the data, Dr. Butler said. The current recommendation is that a patient who tests positive is considered clear to return to work after two negative tests at least 24 hours apart, following the resolution of symptoms. The CDC has not yet made an official recommendation on an exact time frame, but the CDC is considering a 14-day minimum of quarantine.

“The one caveat I’ll add is that someone who is a health care worker, even if they have resolved symptoms, it’s still a good idea to wear a surgical mask [when they return to work], just as an extra precaution.”

What do we know about immunity? Can patients get reinfected?

Long-term immunity after exposure and infection is virtually unknown, Dr. Butler said. Investigators know those with COVID-19 have an antibody response, but whether that is protective or not, is unclear. In regard to older coronaviruses, such as those that cause colds, patients generally develop an antibody response and may have a period of immunity, but that immunity eventually wanes and reinfection can occur.

What is the latest on therapies?

A number of trials are underway in China and in the United States to test possible therapies for COVID-19, Dr. Butler said. One of the candidate drugs is the broad spectrum antiviral drug remdesivir, which was developed for the treatment of the Ebola virus. Additionally, the National Institutes of Health is studying the potential for monoclonal antibodies to treat COVID-19.

“Of course these are drugs not yet FDA approved,” he said. “We all want to have them in our toolbox as soon as possible, but we want to make sure these drugs are going to benefit and not harm, and that they really do have the utility that we hope for.”

Is there specific guidance for healthcare workers about COVID-19?

Health care workers have a much higher likelihood of being exposed or exposing others who are at high risk of severe infection, Dr. Butler said. That’s why, if a health care worker becomes infected and recovers, it’s still important to take extra precautions when going back to work, such as wearing a mask.

“These are recommendations that are in-draft,” he said. “I want to be clear, I’m floating concepts out there that people can consider. ... I recognize as a former infection control medical director at a hospital that sometimes you have to adapt those guidelines based on your local conditions.”

Trump to governors: Don’t wait for feds on medical supplies

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

President Donald Trump has advised state governors not to wait on the federal government when it comes to ensuring readiness for a surge in patients from the COVID-19 outbreak.

“If they are able to get ventilators, respirators, if they are able to get certain things without having to go through the longer process of federal government,” they should order on their own and bypass the federal government ordering system, the president stated during a March 16 press briefing.

That being said, he noted that the federal government is “ordering tremendous numbers of ventilators, respirators, [and] masks,” although he could not give a specific number on how much has been ordered or how many has already been stockpiled.

“It is always going to be faster if they can get them directly, if they need them, and I have given them authorization to order directly,” President Trump said.

The comments came as the White House revised recommendations on gatherings. The new guidelines now limit gatherings to no more than 10 people. Officials are further advising Americans to self-quarantine for 2 weeks if they are sick, if someone in their house is sick, or if someone in their house has tested positive for COVID-19.

Additionally, the White House called on Americans to limit discretionary travel and to avoid eating and drinking in restaurants, bars, and food courts during the next 15 days, even if they are feeling healthy and are asymptomatic.

“With several weeks of focused action, we can turn the corner and turn it quickly,” the president said.

In terms of testing, the Food and Drug Administration has granted emergency use authorization to two commercial diagnostic tests: Thermo Fisher for its TaqPath COVID-19 Combo Kit and Roche for its cobas SARS-CoV-2 test. White House officials said up to 1 million tests will be available this week, with 2 million next week.

The president also announced that phase 1 testing of a vaccine has begun. The test involves more than 40 healthy volunteers in the Seattle area who will receive three shots over the trial period. Phase 1 testing is generally conducted to determine safety of a new therapeutic.

ESC says continue hypertension meds despite COVID-19 concern

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has issued a statement urging physicians and patients to continue treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), in light of a newly described theory that those agents could increase the risk of developing COVID-19 and/or worsen its severity.

The concern arises from the observation that the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 causing COVID-19 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to infect cells, and both ACE inhibitors and ARBs increase ACE2 levels.

This mechanism has been theorized as a possible risk factor for facilitating the acquisition of COVID-19 infection and worsening its severity. However, paradoxically, it has also been hypothesized to protect against acute lung injury from the disease.

Meanwhile, a Lancet Respiratory Medicine article was published March 11 entitled, “Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection?”

“We ... hypothesize that diabetes and hypertension treatment with ACE2-stimulating drugs increases the risk of developing severe and fatal COVID-19,” said the authors.

This prompted some media coverage in the United Kingdom and “social media-related amplification,” leading to concern and, in some cases, discontinuation of the drugs by patients.

But on March 13, the ESC Council on Hypertension dismissed the concerns as entirely speculative, in a statement posted to the ESC website.

It said that the council “strongly recommend that physicians and patients should continue treatment with their usual antihypertensive therapy because there is no clinical or scientific evidence to suggest that treatment with ACE inhibitors or ARBs should be discontinued because of the COVID-19 infection.”

The statement, signed by Council Chair Professor Giovanni de Simone, MD, on behalf of the nucleus members, also says that in regard to the theorized protective effect against serious lung complications in individuals with COVID-19, the data come only from animal, and not human, studies.

“Speculation about the safety of ACE-inhibitor or ARB treatment in relation to COVID-19 does not have a sound scientific basis or evidence to support it,” the ESC panel concludes.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Psychiatric patients and pandemics

What can psychiatric clinicians do to keep their patients healthy in this coronavirus time?

In the 3 days between starting this column and finishing it, the world has gone into a tailspin. Perhaps what I write is no longer relevant. But hopefully it is.

I have no right or wrong answers here but thoughts about factors to consider.

- On inpatient psychiatry wards, the emphasis is on communal living. On our ward, bedrooms and bathrooms are shared. Patients eat together. There are numerous group therapies.

- We have decided to restrict visitors out of the concern that one may infect a ward of patients and staff. We are hoping to do video visitation, but that may take a while to implement.

- An open question is how we are going to provide our involuntary patients with access to the public defense attorneys. Public defenders still have the ability to come onto the inpatient ward, but we will start screening them first.

- In terms of sanitation, wall sanitizers are forbidden, since sanitizers may be drank or made into a firebomb. So we are incessantly wiping down the shared phones and game board pieces.

- Looking at the outpatient arena, we have moved our chairs around, so that there are 3 feet between chairs. We have opened up another waiting room to provide more distance.

- We are trying to decide whether to cancel groups. We did cancel our senior group, and I think I will cancel the rest of them shortly.

- We are seriously looking at telepsychiatry.

- Schools are closed. Many of my clinicians have young children, so they may be out. We are expecting many patients to cancel and will see how that plays out. Others of us have elderly parents. My mother’s assisted-living facility is on lockdown. So, having been locked out after a visit, she is with me tonight.

- Psychiatrists are expected to keep up their relative value unit count. Can they meet their targets? Probably not. Will it matter?

- And what about all our homeless patients, who cannot disinfect their tents or shelters?

- Conferences no longer seem so important. I am less worried about coverage for the American Psychiatric Association meeting, since the 2020 conference has been canceled.

On the rosy side, maybe this will be a wake-up call about climate change. So we live in interesting times.

Take care of your patients and each other.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures.

What can psychiatric clinicians do to keep their patients healthy in this coronavirus time?

In the 3 days between starting this column and finishing it, the world has gone into a tailspin. Perhaps what I write is no longer relevant. But hopefully it is.

I have no right or wrong answers here but thoughts about factors to consider.

- On inpatient psychiatry wards, the emphasis is on communal living. On our ward, bedrooms and bathrooms are shared. Patients eat together. There are numerous group therapies.

- We have decided to restrict visitors out of the concern that one may infect a ward of patients and staff. We are hoping to do video visitation, but that may take a while to implement.

- An open question is how we are going to provide our involuntary patients with access to the public defense attorneys. Public defenders still have the ability to come onto the inpatient ward, but we will start screening them first.

- In terms of sanitation, wall sanitizers are forbidden, since sanitizers may be drank or made into a firebomb. So we are incessantly wiping down the shared phones and game board pieces.

- Looking at the outpatient arena, we have moved our chairs around, so that there are 3 feet between chairs. We have opened up another waiting room to provide more distance.

- We are trying to decide whether to cancel groups. We did cancel our senior group, and I think I will cancel the rest of them shortly.

- We are seriously looking at telepsychiatry.

- Schools are closed. Many of my clinicians have young children, so they may be out. We are expecting many patients to cancel and will see how that plays out. Others of us have elderly parents. My mother’s assisted-living facility is on lockdown. So, having been locked out after a visit, she is with me tonight.

- Psychiatrists are expected to keep up their relative value unit count. Can they meet their targets? Probably not. Will it matter?

- And what about all our homeless patients, who cannot disinfect their tents or shelters?

- Conferences no longer seem so important. I am less worried about coverage for the American Psychiatric Association meeting, since the 2020 conference has been canceled.

On the rosy side, maybe this will be a wake-up call about climate change. So we live in interesting times.

Take care of your patients and each other.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures.

What can psychiatric clinicians do to keep their patients healthy in this coronavirus time?

In the 3 days between starting this column and finishing it, the world has gone into a tailspin. Perhaps what I write is no longer relevant. But hopefully it is.

I have no right or wrong answers here but thoughts about factors to consider.

- On inpatient psychiatry wards, the emphasis is on communal living. On our ward, bedrooms and bathrooms are shared. Patients eat together. There are numerous group therapies.

- We have decided to restrict visitors out of the concern that one may infect a ward of patients and staff. We are hoping to do video visitation, but that may take a while to implement.

- An open question is how we are going to provide our involuntary patients with access to the public defense attorneys. Public defenders still have the ability to come onto the inpatient ward, but we will start screening them first.

- In terms of sanitation, wall sanitizers are forbidden, since sanitizers may be drank or made into a firebomb. So we are incessantly wiping down the shared phones and game board pieces.

- Looking at the outpatient arena, we have moved our chairs around, so that there are 3 feet between chairs. We have opened up another waiting room to provide more distance.

- We are trying to decide whether to cancel groups. We did cancel our senior group, and I think I will cancel the rest of them shortly.

- We are seriously looking at telepsychiatry.

- Schools are closed. Many of my clinicians have young children, so they may be out. We are expecting many patients to cancel and will see how that plays out. Others of us have elderly parents. My mother’s assisted-living facility is on lockdown. So, having been locked out after a visit, she is with me tonight.

- Psychiatrists are expected to keep up their relative value unit count. Can they meet their targets? Probably not. Will it matter?

- And what about all our homeless patients, who cannot disinfect their tents or shelters?

- Conferences no longer seem so important. I am less worried about coverage for the American Psychiatric Association meeting, since the 2020 conference has been canceled.

On the rosy side, maybe this will be a wake-up call about climate change. So we live in interesting times.

Take care of your patients and each other.

Dr. Ritchie is chair of psychiatry at Medstar Washington Hospital Center and professor of psychiatry at Georgetown University, Washington. She has no disclosures.

Here’s what ICUs are putting up against COVID-19

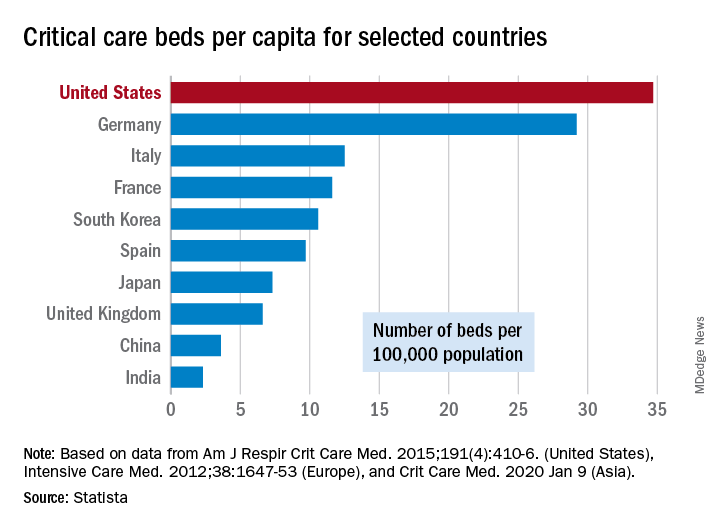

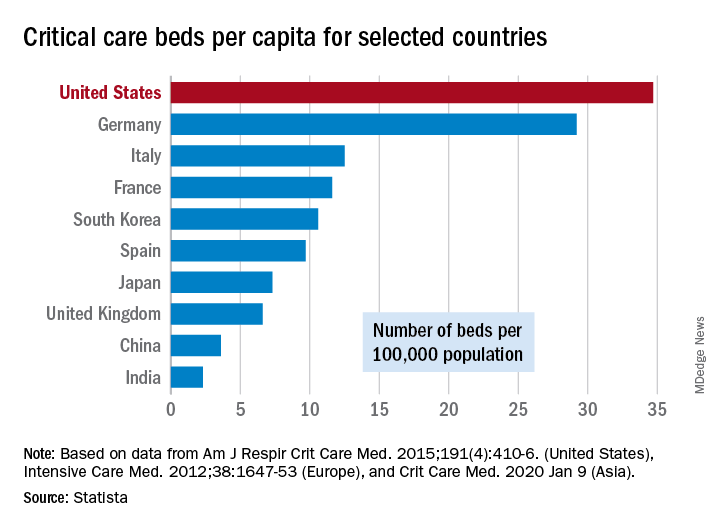

As COVID-19 spreads across the United States, it is important to understand the extent of the nation’s ICU resources, according to the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The SCCM has updated its statistics on the resources available to care for what could become “an overwhelming number of critically ill patients, many of whom may require mechanical ventilation,” the society said in a blog post on March 13.

That overwhelming number was considered at an American Hospital Association webinar in February: Investigators projected that 4.8 million patients could be hospitalized with COVID-19, of whom 1.9 million would be admitted to ICUs and 960,000 would require ventilator support, Neil A. Halpern, MD, director of the critical care center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and Kay See Tan, PhD, of the hospital’s department of epidemiology and biostatistics, reported in that post.

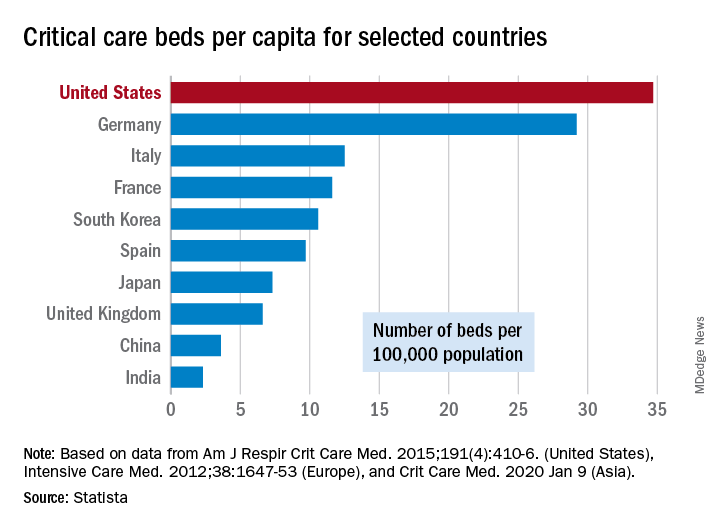

As far as critical care beds are concerned, the United States is in better shape than are other countries dealing with the coronavirus. The United States’ 34.7 critical care beds per 100,000 population put it a good bit ahead of Germany, which has 29.2 beds per 100,000, while other countries in both Europe and Asia are well behind, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan noted.

More recent data from the AHA show that just over half of its registered community hospitals deliver ICU services and have at least 10 acute care beds and one ICU bed, they reported.

Those 2,704 hospitals have nearly 535,000 acute care beds, of which almost 97,000 are ICU beds. Almost 71% of those ICU beds are for adults, with the rest located in neonatal and pediatric units, data from an AHA 2018 survey show.

Since patients with COVID-19 are most often admitted to ICUs with severe hypoxic respiratory failure, the nation’s supply of ventilators also may be tested. U.S. acute care hospitals own about 62,000 full-featured mechanical ventilators and almost 99,000 older ventilators that “may not be capable of adequately supporting patients with severe acute respiratory failure,” Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan said.

As U.S. hospitals reach the crisis levels anticipated in the COVID-19 pandemic, staffing shortages can be expected as well. Almost half (48%) of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, so “other physicians (e.g., pulmonologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc) may be pressed into service as outpatient clinics and elective surgery are suspended,” they wrote.

The blog post includes a tiered staffing strategy that the SCCM “encourages hospitals to adopt in pandemic situations such as COVID-19.”

As COVID-19 spreads across the United States, it is important to understand the extent of the nation’s ICU resources, according to the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The SCCM has updated its statistics on the resources available to care for what could become “an overwhelming number of critically ill patients, many of whom may require mechanical ventilation,” the society said in a blog post on March 13.

That overwhelming number was considered at an American Hospital Association webinar in February: Investigators projected that 4.8 million patients could be hospitalized with COVID-19, of whom 1.9 million would be admitted to ICUs and 960,000 would require ventilator support, Neil A. Halpern, MD, director of the critical care center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and Kay See Tan, PhD, of the hospital’s department of epidemiology and biostatistics, reported in that post.

As far as critical care beds are concerned, the United States is in better shape than are other countries dealing with the coronavirus. The United States’ 34.7 critical care beds per 100,000 population put it a good bit ahead of Germany, which has 29.2 beds per 100,000, while other countries in both Europe and Asia are well behind, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan noted.

More recent data from the AHA show that just over half of its registered community hospitals deliver ICU services and have at least 10 acute care beds and one ICU bed, they reported.

Those 2,704 hospitals have nearly 535,000 acute care beds, of which almost 97,000 are ICU beds. Almost 71% of those ICU beds are for adults, with the rest located in neonatal and pediatric units, data from an AHA 2018 survey show.

Since patients with COVID-19 are most often admitted to ICUs with severe hypoxic respiratory failure, the nation’s supply of ventilators also may be tested. U.S. acute care hospitals own about 62,000 full-featured mechanical ventilators and almost 99,000 older ventilators that “may not be capable of adequately supporting patients with severe acute respiratory failure,” Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan said.

As U.S. hospitals reach the crisis levels anticipated in the COVID-19 pandemic, staffing shortages can be expected as well. Almost half (48%) of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, so “other physicians (e.g., pulmonologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc) may be pressed into service as outpatient clinics and elective surgery are suspended,” they wrote.

The blog post includes a tiered staffing strategy that the SCCM “encourages hospitals to adopt in pandemic situations such as COVID-19.”

As COVID-19 spreads across the United States, it is important to understand the extent of the nation’s ICU resources, according to the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The SCCM has updated its statistics on the resources available to care for what could become “an overwhelming number of critically ill patients, many of whom may require mechanical ventilation,” the society said in a blog post on March 13.

That overwhelming number was considered at an American Hospital Association webinar in February: Investigators projected that 4.8 million patients could be hospitalized with COVID-19, of whom 1.9 million would be admitted to ICUs and 960,000 would require ventilator support, Neil A. Halpern, MD, director of the critical care center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, and Kay See Tan, PhD, of the hospital’s department of epidemiology and biostatistics, reported in that post.

As far as critical care beds are concerned, the United States is in better shape than are other countries dealing with the coronavirus. The United States’ 34.7 critical care beds per 100,000 population put it a good bit ahead of Germany, which has 29.2 beds per 100,000, while other countries in both Europe and Asia are well behind, Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan noted.

More recent data from the AHA show that just over half of its registered community hospitals deliver ICU services and have at least 10 acute care beds and one ICU bed, they reported.

Those 2,704 hospitals have nearly 535,000 acute care beds, of which almost 97,000 are ICU beds. Almost 71% of those ICU beds are for adults, with the rest located in neonatal and pediatric units, data from an AHA 2018 survey show.

Since patients with COVID-19 are most often admitted to ICUs with severe hypoxic respiratory failure, the nation’s supply of ventilators also may be tested. U.S. acute care hospitals own about 62,000 full-featured mechanical ventilators and almost 99,000 older ventilators that “may not be capable of adequately supporting patients with severe acute respiratory failure,” Dr. Halpern and Dr. Tan said.

As U.S. hospitals reach the crisis levels anticipated in the COVID-19 pandemic, staffing shortages can be expected as well. Almost half (48%) of acute care hospitals have no intensivists, so “other physicians (e.g., pulmonologists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, etc) may be pressed into service as outpatient clinics and elective surgery are suspended,” they wrote.

The blog post includes a tiered staffing strategy that the SCCM “encourages hospitals to adopt in pandemic situations such as COVID-19.”

COVID-19 in children, pregnant women: What do we know?

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

A novel coronavirus, the causative agent of the current pandemic of viral respiratory illness and pneumonia, was first identified in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The disease has been given the name, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The virus at last report has spread to more than 100 countries. Much of what we suspect about this virus comes from work on other severe coronavirus respiratory disease outbreaks – Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). MERS-CoV was a viral respiratory disease, first reported in Saudi Arabia, that was identified in more than 27 additional countries. The disease was characterized by severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Among 2,499 cases, only two patients tested positive for MERS-CoV in the United States. SARS-CoV also caused a severe viral respiratory illness. SARS was first recognized in Asia in 2003 and was subsequently reported in approximately 25 countries. The last case reported was in 2004.

As of March 13, there are 137,066 cases worldwide of COVID-19 and 1,701 in the United States, according to the John Hopkins University Coronavirus COVID-19 resource center.

What about children?

The remarkable observation is how few seriously ill children have been identified in the face of global spread. Unlike the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009, where older adults were relatively spared and children were a major target population, COVID-19 appears to be relatively infrequent in children or too mild to come to diagnosis, to date. Specifically, among China’s first approximately 44,000 cases, less than 2% were identified in children less than 20 years of age, and severe disease was uncommon with no deaths in children less than 10 years of age reported. One child, 13 months of age, with acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock was reported in China. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention webcast , children present with fever in about 50% of cases, cough, fatigue, and subsequently some (3%-30%) progress to shortness of breath. Some children and adults have presented with gastrointestinal disease initially. Viral RNA has been detected in respiratory secretions, blood, and stool of affected children; however, the samples were not cultured for virus so whether stool is a potential source for transmission is unclear. In adults, the disease appears to be most severe – with development of pneumonia – in the second week of illness. In both children and adults, the chest x-ray findings are an interstitial pneumonitis, ground glass appearance, and/or patchy infiltrates.

Are some children at greater risk? Are children the source of community transmission? Will children become a greater part of the disease pattern as further cases are identified and further testing is available? We cannot answer many of these questions about COVID-19 in children as yet, but as you are aware, data are accumulating daily, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health are providing regular updates.

A report from China gave us some idea about community transmission and infection risk for children. The Shenzhen CDC identified 391 COVID-19 cases and 1,286 close contacts. Household contacts and those persons traveling with a case of the virus were at highest risk of acquisition. The secondary attack rates within households was 15%; children were as likely to become infected as adults (medRxiv preprint. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.03.20028423).

What about pregnant women?

The data on pregnant women are even more limited. The concern about COVID-19 during pregnancy comes from our knowledge of adverse outcomes from other respiratory viral infections. For example, respiratory viral infections such as influenza have been associated with increased maternal risk of severe disease, and adverse neonatal outcomes, including low birth weight and preterm birth. The experience with SARS also is concerning for excess adverse maternal and neonatal complications such as spontaneous miscarriage, preterm delivery, intrauterine growth restriction, admission to the ICU, renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy all were reported as complications of SARS infection during pregnancy.

Two studies on COVID-19 in pregnancy have been reported to date. In nine pregnant women reported by Chen et al., COVID-19 pneumonia was identified in the third trimester. The women presented with fever, cough, myalgia, sore throat, and/or malaise. Fetal distress was reported in two; all nine infants were born alive. Apgar scores were 8-10 at 1 minute. Five were found to have lymphopenia; three had increases in hepatic enzymes. None of the infants developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, neonatal throat swab, and breast milk samples from six of the nine patients were tested for the novel coronavirus 2019, and all results were negative (Lancet. 2020 Feb 12. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[20]30360-3)https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30360-3/fulltext.

In a study by Zhu et al., nine pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 infection were identified during Jan. 20-Feb. 5, 2020. The onset of clinical symptoms in these women occurred before delivery in four cases, on the day of delivery in two cases, and after delivery in three cases. Of the 10 neonates (one set of twins) many had clinical symptoms, but none were proven to be COVID-19 positive in their pharyngeal swabs. Shortness of breath was observed in six, fever in two, tachycardia in one. GI symptoms such as feeding intolerance, bloating, GI bleed, and vomiting also were observed. Chest radiography showed abnormalities in seven neonates at admission. Thrombocytopenia and/or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy also was reported. Five neonates recovered and were discharged, one died, and four neonates remained in hospital in a stable condition. It is unclear if the illness in these infants was related to COVID-19 (Transl Pediatrics. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.21037/tp.2020.02.06)http://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/35919/28274.

In the limited experience to date, no evidence of virus has been found in the breast milk of women with COVID-19, which is consistent with the SARS experience. Current recommendations are to separate the infant from known COVID-19 infected mothers either in a different room or in the mother’s room using a six foot rule, a barrier curtain of some type, and mask and hand washing prior to any contact between mother and infant. If the mother desires to breastfeed her child, the same precautions – mask and hand washing – should be in place.

What about treatment?

There are no proven effective therapies and supportive care has been the mainstay to date. Clinical trials of remdesivir have been initiated both by Gilead (compassionate use, open label) and by the National Institutes of Health (randomized remdesivirhttps://www.drugs.com/history/remdesivir.html vs. placebo) in adults based on in vitro data suggesting activity again COVID-19. Lopinavir/ritonavir (combination protease inhibitors) also have been administered off label, but no results are available as yet.

Keeping up

I suggest several valuable resources to keep yourself abreast of the rapidly changing COVID-19 story. First the CDC website or your local Department of Health. These are being updated frequently and include advisories on personal protective equipment, clusters of cases in your local community, and current recommendations for mitigation of the epidemic. I have listened to Anthony S. Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and Robert R. Redfield, MD, the director of the CDC almost daily. I trust their viewpoints and transparency about what is and what is not known, as well as the why and wherefore of their guidance, remembering that each day brings new information and new guidance.

Dr. Pelton is professor of pediatrics and epidemiology at Boston University and public health and senior attending physician at Boston Medical Center. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at [email protected].

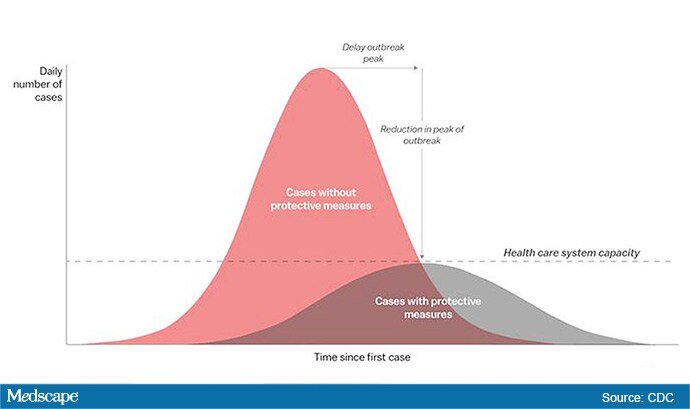

Flattening the curve: Viral graphic shows COVID-19 containment needs

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

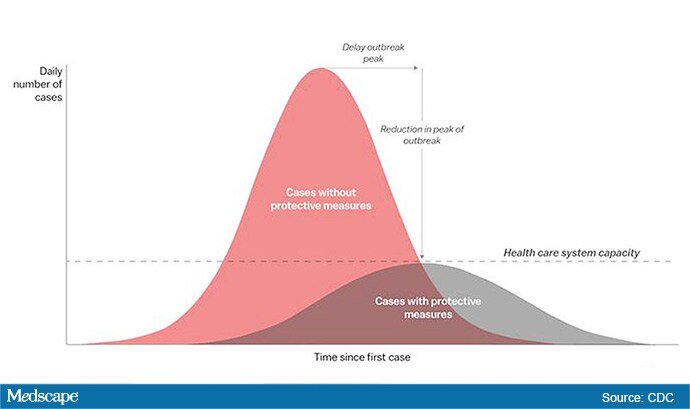

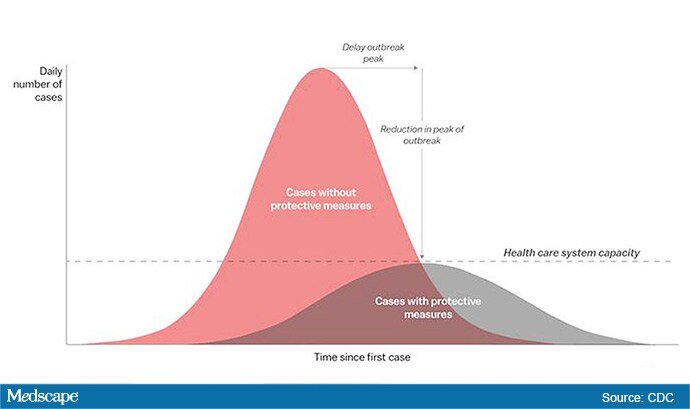

The “Flattening the Curve” graphic, which has, to not use the term lightly, gone viral on social media, visually explains the best currently available strategy to stop the COVID-19 spread, experts told Medscape Medical News.

The height of the curve is the number of potential cases in the United States; along the horizontal X axis, or the breadth, is the amount of time. The line across the middle represents the point at which too many cases in too short a time overwhelm the healthcare system.

Jeanne Marrazzo, MD, MPH, director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham’s School of Medicine explained.

“Not only are you spreading out the new cases but the rate at which people recover,” she told Medscape Medical News. “You have time to get people out of the hospital so you can get new people in and clear out those beds.”

The strategy, with its own Twitter hashtag, #Flattenthecurve, “is about all we have,” without a vaccine, Marrazzo said.

Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said avoiding spikes in cases could mean fewer deaths.

“If you look at the curves of outbreaks, you know, they go big peaks, and then they come down. What we need to do is flatten that down,” Fauci said March 10 in a White House briefing. “You do that by trying to interfere with the natural flow of the outbreak.”

Wuhan, China, at the epicenter of the pandemic, “had an explosive curve” and quickly got overwhelmed without early containment measures, Marrazzo noted. “If you look at Italy right now, it’s clearly in the same situation.”

The Race Is On to Interrupt the Spread

The race is on in the US to interrupt the transmission of the virus and slow the spread, meaning containment measures have increasingly higher and wider stakes.

Closing down Broadway shows and some theme parks and massive sporting events; the escalating numbers of people working from home; and businesses cutting hours or closing all demonstrate the level of US confidence that “social distancing” will work, Marrazzo said.

“We’re clearly ready to disrupt the economy and social infrastructure,” she said.

That appears to have made a difference in Wuhan, Marrazzo said, as the new infections are coming down.

The question, she said, is “we’re not China – so are Americans really going to take to this? Americans greatly value their liberty and there’s some skepticism about public health and its directives. People have never seen a pandemic like this before.”

Dena Grayson, MD, PhD, a Florida-based expert in Ebola and other pandemic threats, told Medscape Medical News that EvergreenHealth in Kirkland, Washington, is a good example of what it means when a virus overwhelms healthcare operations.

The New York Times reported that supplies were so strained at the facility that staff were using sanitary napkins to pad protective helmets.

As of March 11, 65 people who had come into the hospital have tested positive for the virus, and 15 of them had died.

Grayson points out that the COVID-19 cases come on top of a severe flu season and the usual cases hospitals see, so the bar on the graphic is even lower than it usually would be.

“We have a relatively limited capacity with ICU beds to begin with,” she said.

So far, closures, postponements, and cancellations are woefully inadequate, Grayson said.

“We can’t stop this virus. We can hope to contain it and slow down the rate of infection,” she said.

“We need to right now shut down all the schools, preschools, and universities,” Grayson said. “We need to look at shutting down public transportation. We need people to stay home – and not for a day but for a couple of weeks.”