User login

Health professionals fight against COVID-19 myths and misinformation

Misinformation about the COVID-19 travels faster than the virus and complicates the job of doctors who are treating those infected and responding to concerns of their other patients.

An array of myths springing up around this disease can be found on the Internet. The main themes appear to be false narratives about the origin of the virus, the size of the outbreak in the United States and in other countries, the availability of cures and treatments, and ways to prevent infection. Widespread misinformation hampers public health efforts to control the disease outbreak, confuses the public, and requires medical professionals to spend time refuting myths and re-educating patients.

A group of infectious disease experts became so alarmed by the misinformation trend they published a statement in The Lancet decrying the spread of false statements being circulated by some media outlets. “The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation ... Conspiracy theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our global collaboration in the fight against this virus,” wrote Charles H. Calisher, PhD, of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and colleagues.

What can physicians do to counter misinformation?

Pulmonologist and critical care physician Cedric “Jamie” Rutland, MD, who practices in Riverside, Calif., sees misinformation about the novel coronavirus every day at home and on the job. His patients worry that everyone who gets infected will die or end up in the ICU. His neighbors ask him to pilfer surgical masks to protect them from the false notion that Chinese people in their community posed some kind of COVID-19 risk.

As he pondered how to counter myths with facts, Dr. Rutland turned to an unusual resource: His 7-year-old daughter Amelia. He explained to her how COVID-19 works and found that she could easily understand the basics. Now, Dr. Rutland draws upon the lessons from chats with his daughter as he explains COVID-19 to his patient audience on his YouTube channel “Medicine Deconstructed.” Simplicity, but not too much simplicity, is key, he said. Dr. Rutland uses a visual aid – a rough drawing of a virus – and shows how inflammation and antibodies enter the picture after infection. “I just teach them that if you’re a healthy person, this is how the body works, and this is what the immune system will do,” he said. “For the most part, you can calm people down when you make time for education.”

What are best practices? In a series of interviews, specialists emphasized the importance of fact-finding, wide-ranging communication, and – perhaps most difficult of all – humility.

Dr. Rutland emphasizes thoughtful communication based on facts and humility when communicating to patients about this potential health risk. “A lot of people finish medical school and think, ‘Everyone should trust me because I’m the pulmonologist or the GI doc.’ That’s not how it works. You still have to earn people’s trust,” he said.

Make sure all staff get reliable information

Hospitals are scrambling to keep staff safe with up-to-date directives and debunk false narratives about the virus. Keeping all hospital staff informed with verified and authoritative facts about the coronavirus is a key objective of the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Disaster Medicine. The Center’s coronavirus educational materials are distributed to all staffers from physicians to janitors. “These provide information that they need to understand the risks and keep themselves safe,” said Eileen Searle, PhD, the Biothreats Clinical Operations program manager in the CDM.

According to Dr. Searle, the hospital keeps a continually updated COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions document in its internal computer system. All employees can access it, she said, and it’s updated to include questions as they come up.

Even valets and front-desk volunteers are encouraged to read the FAQ, she said, since “they’re the first people that family and patients are interacting with.” The document “gives them reassurance about delivering messages,” she said.

Use patience with your patients

Dr. Rutland urges colleagues to take the time to listen to patients and educate them. “Reduce the gap between you and them,” said Dr. Rutland, who treats patients in Orange and Riverside counties. “Take off your white coat, sit down, and talk to the person about their concerns.”

Boston cardiologist Haider Warraich, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s important to “put medical information into a greater human context.” For example, he has told patients that he’s still taking his daughter to school despite COVID-19 risks. “I take the information I provide and apply it to my own life,” he said.

The Washington State Department of Health offers this advice to physicians to counter false information and stigma: “Stay updated and informed on COVID-19 to avoid miscommunication or inaccurate information. Talk openly about the harm of stigma. View people directly impacted by stigma as people first. Be conscious of your language. Acknowledge access and language barriers.”

Speak out on social media – but don’t fight

Should medical professionals speak out about COVID-19 misinformation via social media? It’s an individual decision, Dr. Warraich said, “but my sense is that it’s never been more important for physicians to be part of the fray and help quell the epidemic of misinformation that almost always follows any type of medial calamity.”

Dr. Rutland, vice president and founding member of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, cautioned that effective communication via social media requires care. Avoid confrontation, he advised. “Don’t call people stupid or say things like, ‘I went to medical school and I’m smarter than you.’ ”

Instead, he said, “it’s important to just state the facts: These are the people who are dying, these are the people who are getting infected.”

And, he added, remember to push the most important message of all: Wash your hands!

Public health organizations fight the ‘infodemic’

In a trend that hearkens back to the days of snake oil cures for all maladies, advertisements for fake treatments are popping up on the Internet and on other media.

Facebook and Amazon have acted to remove these ads but these messages continue to flood social media such as Twitter, WhatsApp, and other sites. Discussion groups on platforms such as Reddit continue to pump out misinformation about COVID-19. Conspiracy theories that link the virus to espionage and bioweapons are making the rounds on the Internet and talk radio. Wrong information about the effectiveness of non-N95 face masks to protect wearers against infection is widespread, leading to shortages for medical personnel and price gouging. Pernicious rumors about the effectiveness of substances such a vinegar, silver, garlic, lemon juice, and even vodka to disinfect hands and surfaces abound on the Internet. An especially dangerous stream of misinformation stigmatizes ethnic groups and individuals as sources of the infection.

The World Health Organization identified early in the COVID-19 outbreak the global wave of misinformation about the virus and dubbed the problem the “infodemic.” The WHO “Q & A” page on COVID-19 is updated frequently and addresses myths and rumors currently circulating.

According to the WHO website, the agency has reached out to social media players such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, and Weibo, the microblogging site in China. WHO has worked with these sites to curb the “infodemic” of misinformation and has used these sites for public education outreach on COVID-19. “Myth busting” infographics posted on a WHO web page are also reposted on major social media sites.

The CDC has followed with its own “frequently asked questions” page to address questions and rumors. State health agencies have put up COVID-19 pages to address public concerns and offer advice on prevention. The Maryland Department of Health web page directly addresses dangerous misinformation: “Do not stigmatize people of any specific ethnicities or racial background. Viruses do not target people from specific populations, ethnicities or racial backgrounds. Stay informed and seek information from reliable, official sources. Be wary of myths, rumors and misinformation circulating online and elsewhere. Health information shared through social media is frequently inaccurate, unless coming from an official, reliable source such as the CDC, MDH or local health departments.”

The Washington State Department of Health has taken a more assertive stance on stigma. The COVID-19 web page recommends to the public: “Show compassion and support for individuals and communities more closely impacted. Avoid stigmatizing people who are in quarantine. They are making the right choice for their communities. Do not make assumptions about someone’s health status based on their ethnicity, race or national origin.”

Misinformation about the COVID-19 travels faster than the virus and complicates the job of doctors who are treating those infected and responding to concerns of their other patients.

An array of myths springing up around this disease can be found on the Internet. The main themes appear to be false narratives about the origin of the virus, the size of the outbreak in the United States and in other countries, the availability of cures and treatments, and ways to prevent infection. Widespread misinformation hampers public health efforts to control the disease outbreak, confuses the public, and requires medical professionals to spend time refuting myths and re-educating patients.

A group of infectious disease experts became so alarmed by the misinformation trend they published a statement in The Lancet decrying the spread of false statements being circulated by some media outlets. “The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation ... Conspiracy theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our global collaboration in the fight against this virus,” wrote Charles H. Calisher, PhD, of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and colleagues.

What can physicians do to counter misinformation?

Pulmonologist and critical care physician Cedric “Jamie” Rutland, MD, who practices in Riverside, Calif., sees misinformation about the novel coronavirus every day at home and on the job. His patients worry that everyone who gets infected will die or end up in the ICU. His neighbors ask him to pilfer surgical masks to protect them from the false notion that Chinese people in their community posed some kind of COVID-19 risk.

As he pondered how to counter myths with facts, Dr. Rutland turned to an unusual resource: His 7-year-old daughter Amelia. He explained to her how COVID-19 works and found that she could easily understand the basics. Now, Dr. Rutland draws upon the lessons from chats with his daughter as he explains COVID-19 to his patient audience on his YouTube channel “Medicine Deconstructed.” Simplicity, but not too much simplicity, is key, he said. Dr. Rutland uses a visual aid – a rough drawing of a virus – and shows how inflammation and antibodies enter the picture after infection. “I just teach them that if you’re a healthy person, this is how the body works, and this is what the immune system will do,” he said. “For the most part, you can calm people down when you make time for education.”

What are best practices? In a series of interviews, specialists emphasized the importance of fact-finding, wide-ranging communication, and – perhaps most difficult of all – humility.

Dr. Rutland emphasizes thoughtful communication based on facts and humility when communicating to patients about this potential health risk. “A lot of people finish medical school and think, ‘Everyone should trust me because I’m the pulmonologist or the GI doc.’ That’s not how it works. You still have to earn people’s trust,” he said.

Make sure all staff get reliable information

Hospitals are scrambling to keep staff safe with up-to-date directives and debunk false narratives about the virus. Keeping all hospital staff informed with verified and authoritative facts about the coronavirus is a key objective of the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Disaster Medicine. The Center’s coronavirus educational materials are distributed to all staffers from physicians to janitors. “These provide information that they need to understand the risks and keep themselves safe,” said Eileen Searle, PhD, the Biothreats Clinical Operations program manager in the CDM.

According to Dr. Searle, the hospital keeps a continually updated COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions document in its internal computer system. All employees can access it, she said, and it’s updated to include questions as they come up.

Even valets and front-desk volunteers are encouraged to read the FAQ, she said, since “they’re the first people that family and patients are interacting with.” The document “gives them reassurance about delivering messages,” she said.

Use patience with your patients

Dr. Rutland urges colleagues to take the time to listen to patients and educate them. “Reduce the gap between you and them,” said Dr. Rutland, who treats patients in Orange and Riverside counties. “Take off your white coat, sit down, and talk to the person about their concerns.”

Boston cardiologist Haider Warraich, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s important to “put medical information into a greater human context.” For example, he has told patients that he’s still taking his daughter to school despite COVID-19 risks. “I take the information I provide and apply it to my own life,” he said.

The Washington State Department of Health offers this advice to physicians to counter false information and stigma: “Stay updated and informed on COVID-19 to avoid miscommunication or inaccurate information. Talk openly about the harm of stigma. View people directly impacted by stigma as people first. Be conscious of your language. Acknowledge access and language barriers.”

Speak out on social media – but don’t fight

Should medical professionals speak out about COVID-19 misinformation via social media? It’s an individual decision, Dr. Warraich said, “but my sense is that it’s never been more important for physicians to be part of the fray and help quell the epidemic of misinformation that almost always follows any type of medial calamity.”

Dr. Rutland, vice president and founding member of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, cautioned that effective communication via social media requires care. Avoid confrontation, he advised. “Don’t call people stupid or say things like, ‘I went to medical school and I’m smarter than you.’ ”

Instead, he said, “it’s important to just state the facts: These are the people who are dying, these are the people who are getting infected.”

And, he added, remember to push the most important message of all: Wash your hands!

Public health organizations fight the ‘infodemic’

In a trend that hearkens back to the days of snake oil cures for all maladies, advertisements for fake treatments are popping up on the Internet and on other media.

Facebook and Amazon have acted to remove these ads but these messages continue to flood social media such as Twitter, WhatsApp, and other sites. Discussion groups on platforms such as Reddit continue to pump out misinformation about COVID-19. Conspiracy theories that link the virus to espionage and bioweapons are making the rounds on the Internet and talk radio. Wrong information about the effectiveness of non-N95 face masks to protect wearers against infection is widespread, leading to shortages for medical personnel and price gouging. Pernicious rumors about the effectiveness of substances such a vinegar, silver, garlic, lemon juice, and even vodka to disinfect hands and surfaces abound on the Internet. An especially dangerous stream of misinformation stigmatizes ethnic groups and individuals as sources of the infection.

The World Health Organization identified early in the COVID-19 outbreak the global wave of misinformation about the virus and dubbed the problem the “infodemic.” The WHO “Q & A” page on COVID-19 is updated frequently and addresses myths and rumors currently circulating.

According to the WHO website, the agency has reached out to social media players such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, and Weibo, the microblogging site in China. WHO has worked with these sites to curb the “infodemic” of misinformation and has used these sites for public education outreach on COVID-19. “Myth busting” infographics posted on a WHO web page are also reposted on major social media sites.

The CDC has followed with its own “frequently asked questions” page to address questions and rumors. State health agencies have put up COVID-19 pages to address public concerns and offer advice on prevention. The Maryland Department of Health web page directly addresses dangerous misinformation: “Do not stigmatize people of any specific ethnicities or racial background. Viruses do not target people from specific populations, ethnicities or racial backgrounds. Stay informed and seek information from reliable, official sources. Be wary of myths, rumors and misinformation circulating online and elsewhere. Health information shared through social media is frequently inaccurate, unless coming from an official, reliable source such as the CDC, MDH or local health departments.”

The Washington State Department of Health has taken a more assertive stance on stigma. The COVID-19 web page recommends to the public: “Show compassion and support for individuals and communities more closely impacted. Avoid stigmatizing people who are in quarantine. They are making the right choice for their communities. Do not make assumptions about someone’s health status based on their ethnicity, race or national origin.”

Misinformation about the COVID-19 travels faster than the virus and complicates the job of doctors who are treating those infected and responding to concerns of their other patients.

An array of myths springing up around this disease can be found on the Internet. The main themes appear to be false narratives about the origin of the virus, the size of the outbreak in the United States and in other countries, the availability of cures and treatments, and ways to prevent infection. Widespread misinformation hampers public health efforts to control the disease outbreak, confuses the public, and requires medical professionals to spend time refuting myths and re-educating patients.

A group of infectious disease experts became so alarmed by the misinformation trend they published a statement in The Lancet decrying the spread of false statements being circulated by some media outlets. “The rapid, open, and transparent sharing of data on this outbreak is now being threatened by rumours and misinformation ... Conspiracy theories do nothing but create fear, rumours, and prejudice that jeopardise our global collaboration in the fight against this virus,” wrote Charles H. Calisher, PhD, of Colorado State University, Fort Collins, and colleagues.

What can physicians do to counter misinformation?

Pulmonologist and critical care physician Cedric “Jamie” Rutland, MD, who practices in Riverside, Calif., sees misinformation about the novel coronavirus every day at home and on the job. His patients worry that everyone who gets infected will die or end up in the ICU. His neighbors ask him to pilfer surgical masks to protect them from the false notion that Chinese people in their community posed some kind of COVID-19 risk.

As he pondered how to counter myths with facts, Dr. Rutland turned to an unusual resource: His 7-year-old daughter Amelia. He explained to her how COVID-19 works and found that she could easily understand the basics. Now, Dr. Rutland draws upon the lessons from chats with his daughter as he explains COVID-19 to his patient audience on his YouTube channel “Medicine Deconstructed.” Simplicity, but not too much simplicity, is key, he said. Dr. Rutland uses a visual aid – a rough drawing of a virus – and shows how inflammation and antibodies enter the picture after infection. “I just teach them that if you’re a healthy person, this is how the body works, and this is what the immune system will do,” he said. “For the most part, you can calm people down when you make time for education.”

What are best practices? In a series of interviews, specialists emphasized the importance of fact-finding, wide-ranging communication, and – perhaps most difficult of all – humility.

Dr. Rutland emphasizes thoughtful communication based on facts and humility when communicating to patients about this potential health risk. “A lot of people finish medical school and think, ‘Everyone should trust me because I’m the pulmonologist or the GI doc.’ That’s not how it works. You still have to earn people’s trust,” he said.

Make sure all staff get reliable information

Hospitals are scrambling to keep staff safe with up-to-date directives and debunk false narratives about the virus. Keeping all hospital staff informed with verified and authoritative facts about the coronavirus is a key objective of the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Center for Disaster Medicine. The Center’s coronavirus educational materials are distributed to all staffers from physicians to janitors. “These provide information that they need to understand the risks and keep themselves safe,” said Eileen Searle, PhD, the Biothreats Clinical Operations program manager in the CDM.

According to Dr. Searle, the hospital keeps a continually updated COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions document in its internal computer system. All employees can access it, she said, and it’s updated to include questions as they come up.

Even valets and front-desk volunteers are encouraged to read the FAQ, she said, since “they’re the first people that family and patients are interacting with.” The document “gives them reassurance about delivering messages,” she said.

Use patience with your patients

Dr. Rutland urges colleagues to take the time to listen to patients and educate them. “Reduce the gap between you and them,” said Dr. Rutland, who treats patients in Orange and Riverside counties. “Take off your white coat, sit down, and talk to the person about their concerns.”

Boston cardiologist Haider Warraich, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s important to “put medical information into a greater human context.” For example, he has told patients that he’s still taking his daughter to school despite COVID-19 risks. “I take the information I provide and apply it to my own life,” he said.

The Washington State Department of Health offers this advice to physicians to counter false information and stigma: “Stay updated and informed on COVID-19 to avoid miscommunication or inaccurate information. Talk openly about the harm of stigma. View people directly impacted by stigma as people first. Be conscious of your language. Acknowledge access and language barriers.”

Speak out on social media – but don’t fight

Should medical professionals speak out about COVID-19 misinformation via social media? It’s an individual decision, Dr. Warraich said, “but my sense is that it’s never been more important for physicians to be part of the fray and help quell the epidemic of misinformation that almost always follows any type of medial calamity.”

Dr. Rutland, vice president and founding member of the Association for Healthcare Social Media, cautioned that effective communication via social media requires care. Avoid confrontation, he advised. “Don’t call people stupid or say things like, ‘I went to medical school and I’m smarter than you.’ ”

Instead, he said, “it’s important to just state the facts: These are the people who are dying, these are the people who are getting infected.”

And, he added, remember to push the most important message of all: Wash your hands!

Public health organizations fight the ‘infodemic’

In a trend that hearkens back to the days of snake oil cures for all maladies, advertisements for fake treatments are popping up on the Internet and on other media.

Facebook and Amazon have acted to remove these ads but these messages continue to flood social media such as Twitter, WhatsApp, and other sites. Discussion groups on platforms such as Reddit continue to pump out misinformation about COVID-19. Conspiracy theories that link the virus to espionage and bioweapons are making the rounds on the Internet and talk radio. Wrong information about the effectiveness of non-N95 face masks to protect wearers against infection is widespread, leading to shortages for medical personnel and price gouging. Pernicious rumors about the effectiveness of substances such a vinegar, silver, garlic, lemon juice, and even vodka to disinfect hands and surfaces abound on the Internet. An especially dangerous stream of misinformation stigmatizes ethnic groups and individuals as sources of the infection.

The World Health Organization identified early in the COVID-19 outbreak the global wave of misinformation about the virus and dubbed the problem the “infodemic.” The WHO “Q & A” page on COVID-19 is updated frequently and addresses myths and rumors currently circulating.

According to the WHO website, the agency has reached out to social media players such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, Pinterest, TikTok, and Weibo, the microblogging site in China. WHO has worked with these sites to curb the “infodemic” of misinformation and has used these sites for public education outreach on COVID-19. “Myth busting” infographics posted on a WHO web page are also reposted on major social media sites.

The CDC has followed with its own “frequently asked questions” page to address questions and rumors. State health agencies have put up COVID-19 pages to address public concerns and offer advice on prevention. The Maryland Department of Health web page directly addresses dangerous misinformation: “Do not stigmatize people of any specific ethnicities or racial background. Viruses do not target people from specific populations, ethnicities or racial backgrounds. Stay informed and seek information from reliable, official sources. Be wary of myths, rumors and misinformation circulating online and elsewhere. Health information shared through social media is frequently inaccurate, unless coming from an official, reliable source such as the CDC, MDH or local health departments.”

The Washington State Department of Health has taken a more assertive stance on stigma. The COVID-19 web page recommends to the public: “Show compassion and support for individuals and communities more closely impacted. Avoid stigmatizing people who are in quarantine. They are making the right choice for their communities. Do not make assumptions about someone’s health status based on their ethnicity, race or national origin.”

Coronavirus in dermatology: What steps to take

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is presenting a severe challenge to global health care, but its impact isn’t just felt in the emergency department. Specialists, including dermatologists, must also navigate the presence of the virus and its impact on patients and practices.

A new report from dermatologists in China’s Wuhan province, where the 2019-nCoV outbreak began, outlines initial experiences and provides a blueprint for triaging potential cases before they reach the dermatology clinic. Despite its presence in the epicenter of the outbreak, the hospital has not detected any 2019-nCoV-infected patients in any of its departments.

The commentary appeared in the British Journal of Dermatology and was authored by a group led by Juan Tao of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19011).

The hospital triages all patients at the hospital entrance. Those who are suspected of having 2019-nCoV infection are sent to a designated department. Those with a skin condition who are not suspected of being infected are allowed to go to a dermatology triage center, where they are examined again. If the second examination raises suspicion, they are sent to the designated 2019-nCoV department. If no infection is suspected, or a patient from the 2019-nCoV department is cleared, they are allowed access to the dermatology clinic.

The team also suggested that skin lesions associated with dermatological conditions could lead to increased risk of 2019-nCoV infection. Contacted by email, Dr. Tao outlined a theoretical risk that the virus could lead to infection through contact with subcutaneous tissues, mucosal surfaces, or blood vessels. He did not respond to a request for evidence that such a route of transmission had occurred.

However, Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he doubted any such transmission would occur since the virus does not infect keratinocytes, and expressed concern that the suggestion could add to the stigma experienced by dermatological patients, whose noticeable rashes can sometimes lead to social avoidance. “I don’t want to add to that,” said Dr. Friedman in an interview.

A critical aspect of dermatology is the immunosuppressive agents often used in dermatology patients. Such drugs could make them more susceptible to infections, or to worse outcomes in the event of disease. Dr. Friedman recounted sending a letter to one patient on an immunosuppressive medication, suggesting that she work remotely. “I think that’s something we have to think about in at-risk individuals. I know there’s such a focus on the elderly, but there’s a large population of individuals on medications that lower their immune system who are going to be at risk for more severe infections,” said Dr. Friedman.

To reduce patient exposure, the commentary recommended that dermatologists perform online consultation for mild and nonemergency cases.

The authors also covered hospitalized patients with primary or secondary skin conditions. A dermatologist is on site at the dermatology triage station to conduct in-depth assessments if needed. If a patient has a fever that is believed to be caused by a dermatologic condition, the on-site dermatologist assists in the consult.

Because some patients may only become symptomatic after admission to a ward, the authors recommend hospitals have a COVID-19 trained contingency group on hand to prevent and control outbreaks within the institution. The team should be in communication with respiratory intensive care and radiology departments to exclude 2019-nCoV when cases develop in-hospital, and to ensure proper care infected patients who require it.

When a hospitalized 2019-nCoV-infected patient has a skin condition requiring treatment, the authors recommend that pictures be sent to the dermatologist for evaluation, along with teleconferences to further assess the patient. If necessary, the dermatologist should go to the patient’s bedside, with as much information as possible related in advance in order to minimize bedside exposure.

There was no funding source. Dr. Tao and Dr. Friedman have no relevant financial conflicts.

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is presenting a severe challenge to global health care, but its impact isn’t just felt in the emergency department. Specialists, including dermatologists, must also navigate the presence of the virus and its impact on patients and practices.

A new report from dermatologists in China’s Wuhan province, where the 2019-nCoV outbreak began, outlines initial experiences and provides a blueprint for triaging potential cases before they reach the dermatology clinic. Despite its presence in the epicenter of the outbreak, the hospital has not detected any 2019-nCoV-infected patients in any of its departments.

The commentary appeared in the British Journal of Dermatology and was authored by a group led by Juan Tao of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19011).

The hospital triages all patients at the hospital entrance. Those who are suspected of having 2019-nCoV infection are sent to a designated department. Those with a skin condition who are not suspected of being infected are allowed to go to a dermatology triage center, where they are examined again. If the second examination raises suspicion, they are sent to the designated 2019-nCoV department. If no infection is suspected, or a patient from the 2019-nCoV department is cleared, they are allowed access to the dermatology clinic.

The team also suggested that skin lesions associated with dermatological conditions could lead to increased risk of 2019-nCoV infection. Contacted by email, Dr. Tao outlined a theoretical risk that the virus could lead to infection through contact with subcutaneous tissues, mucosal surfaces, or blood vessels. He did not respond to a request for evidence that such a route of transmission had occurred.

However, Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he doubted any such transmission would occur since the virus does not infect keratinocytes, and expressed concern that the suggestion could add to the stigma experienced by dermatological patients, whose noticeable rashes can sometimes lead to social avoidance. “I don’t want to add to that,” said Dr. Friedman in an interview.

A critical aspect of dermatology is the immunosuppressive agents often used in dermatology patients. Such drugs could make them more susceptible to infections, or to worse outcomes in the event of disease. Dr. Friedman recounted sending a letter to one patient on an immunosuppressive medication, suggesting that she work remotely. “I think that’s something we have to think about in at-risk individuals. I know there’s such a focus on the elderly, but there’s a large population of individuals on medications that lower their immune system who are going to be at risk for more severe infections,” said Dr. Friedman.

To reduce patient exposure, the commentary recommended that dermatologists perform online consultation for mild and nonemergency cases.

The authors also covered hospitalized patients with primary or secondary skin conditions. A dermatologist is on site at the dermatology triage station to conduct in-depth assessments if needed. If a patient has a fever that is believed to be caused by a dermatologic condition, the on-site dermatologist assists in the consult.

Because some patients may only become symptomatic after admission to a ward, the authors recommend hospitals have a COVID-19 trained contingency group on hand to prevent and control outbreaks within the institution. The team should be in communication with respiratory intensive care and radiology departments to exclude 2019-nCoV when cases develop in-hospital, and to ensure proper care infected patients who require it.

When a hospitalized 2019-nCoV-infected patient has a skin condition requiring treatment, the authors recommend that pictures be sent to the dermatologist for evaluation, along with teleconferences to further assess the patient. If necessary, the dermatologist should go to the patient’s bedside, with as much information as possible related in advance in order to minimize bedside exposure.

There was no funding source. Dr. Tao and Dr. Friedman have no relevant financial conflicts.

The novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) is presenting a severe challenge to global health care, but its impact isn’t just felt in the emergency department. Specialists, including dermatologists, must also navigate the presence of the virus and its impact on patients and practices.

A new report from dermatologists in China’s Wuhan province, where the 2019-nCoV outbreak began, outlines initial experiences and provides a blueprint for triaging potential cases before they reach the dermatology clinic. Despite its presence in the epicenter of the outbreak, the hospital has not detected any 2019-nCoV-infected patients in any of its departments.

The commentary appeared in the British Journal of Dermatology and was authored by a group led by Juan Tao of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Br J Dermatol. 2020 Mar 5. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19011).

The hospital triages all patients at the hospital entrance. Those who are suspected of having 2019-nCoV infection are sent to a designated department. Those with a skin condition who are not suspected of being infected are allowed to go to a dermatology triage center, where they are examined again. If the second examination raises suspicion, they are sent to the designated 2019-nCoV department. If no infection is suspected, or a patient from the 2019-nCoV department is cleared, they are allowed access to the dermatology clinic.

The team also suggested that skin lesions associated with dermatological conditions could lead to increased risk of 2019-nCoV infection. Contacted by email, Dr. Tao outlined a theoretical risk that the virus could lead to infection through contact with subcutaneous tissues, mucosal surfaces, or blood vessels. He did not respond to a request for evidence that such a route of transmission had occurred.

However, Adam Friedman, MD, professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said he doubted any such transmission would occur since the virus does not infect keratinocytes, and expressed concern that the suggestion could add to the stigma experienced by dermatological patients, whose noticeable rashes can sometimes lead to social avoidance. “I don’t want to add to that,” said Dr. Friedman in an interview.

A critical aspect of dermatology is the immunosuppressive agents often used in dermatology patients. Such drugs could make them more susceptible to infections, or to worse outcomes in the event of disease. Dr. Friedman recounted sending a letter to one patient on an immunosuppressive medication, suggesting that she work remotely. “I think that’s something we have to think about in at-risk individuals. I know there’s such a focus on the elderly, but there’s a large population of individuals on medications that lower their immune system who are going to be at risk for more severe infections,” said Dr. Friedman.

To reduce patient exposure, the commentary recommended that dermatologists perform online consultation for mild and nonemergency cases.

The authors also covered hospitalized patients with primary or secondary skin conditions. A dermatologist is on site at the dermatology triage station to conduct in-depth assessments if needed. If a patient has a fever that is believed to be caused by a dermatologic condition, the on-site dermatologist assists in the consult.

Because some patients may only become symptomatic after admission to a ward, the authors recommend hospitals have a COVID-19 trained contingency group on hand to prevent and control outbreaks within the institution. The team should be in communication with respiratory intensive care and radiology departments to exclude 2019-nCoV when cases develop in-hospital, and to ensure proper care infected patients who require it.

When a hospitalized 2019-nCoV-infected patient has a skin condition requiring treatment, the authors recommend that pictures be sent to the dermatologist for evaluation, along with teleconferences to further assess the patient. If necessary, the dermatologist should go to the patient’s bedside, with as much information as possible related in advance in order to minimize bedside exposure.

There was no funding source. Dr. Tao and Dr. Friedman have no relevant financial conflicts.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Early GI symptoms in COVID-19 may indicate fecal transmission

Fecal-oral transmission may be part of the COVID-19 clinical picture, according to two reports published in Gastroenterology. The researchers find that RNA and proteins from SARS-CoV-2, the viral cause of COVID-19, are shed in feces early in infection and persist after respiratory symptoms abate.

But the discovery is preliminary. “There is evidence of the virus in stool, but not evidence of infectious virus,” David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, told Medscape Medical News.

The findings are not entirely unexpected. Both of the coronaviruses behind SARS and MERS are shed in stool, Jinyang Gu, MD, from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in Shanghai, China, and colleagues, note in one of the newly published articles.

In addition, as COVID-19 spread beyond China, clinicians began noticing initial mild gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in some patients, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, preceding the hallmark fever, dry cough, and dyspnea. The first patient diagnosed in the United States with COVID-19 reported having 2 days of nausea and vomiting, with viral RNA detected in fecal and respiratory specimens, according to an earlier report.

Gu and colleagues warn that initial investigations would likely have not considered cases that manifested initially only as mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

Although early reports indicated that only about 10% of people with COVID-19 have GI symptoms, it isn’t known whether some infected individuals have only GI symptoms, Johnson said.

The GI manifestations are consistent with the distribution of ACE2 receptors, which serve as entry points for SARS-CoV-2, as well as SARS-CoV-1, which causes SARS. The receptors are most abundant in the cell membranes of lung AT2 cells, as well as in enterocytes in the ileum and colon.

“Altogether, many efforts should be made to be alert on the initial digestive symptoms of COVID-19 for early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation and early intervention,” Gu and colleagues conclude.

But Johnson cautions, “gastroenterologists are not the ones managing diagnosis of COVID-19. It is diagnosed as a respiratory illness, but we are seeing concomitant gastrointestinal shedding in stool and saliva, and GI symptoms.”

Samples From 73 Patients Studied

In the second article published, Fei Xiao, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong Province, China, and colleagues report detecting viral RNA in samples from the mouths, noses, throats, urine, and feces of 73 patients hospitalized during the first 2 weeks of February.

Of the 73 hospitalized patients, 39 (53.24%; 25 males and 14 females) had viral RNA in their feces, present from 1 to 12 days. Seventeen (23.29%) of the patients continued to have viral RNA in their stool after respiratory symptoms had improved.

One patient underwent endoscopy. There was no evidence of damage to the GI epithelium, but the clinicians detected slightly elevated levels of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

The researcher used laser scanning confocal microscopy to analyze samples taken during the endoscopy. They found evidence of both ACE2 receptors and viral nucleocapsid proteins in the gastric, duodenal, and rectal glandular epithelial cells.

Finding evidence of SARS-CoV-2 throughout the GI system, if not direct infectivity, suggests a fecal-oral route of transmission, the researchers conclude. “Our immunofluorescent data showed that ACE2 protein, a cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is abundantly expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelia, supporting the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cells.”

Detection of viral RNA at different time points in infection, they write, suggests that the virions are continually secreted and therefore likely infectious, which is under investigation. “Prevention of fecal-oral transmission should be taken into consideration to control the spread of the virus,” they write.

Current recommendations do not require that patients’ fecal samples be tested before being considered noninfectious. However, given their findings and evidence from other studies, Xiao and colleagues recommend that real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing of fecal samples be added to current protocols.

Johnson offers practical suggestions based on the “potty hygiene” suggestions he gives to patients dealing with fecal shedding in Clostridioides difficile infection.

“To combat the microaerosolization of C. diff spores, I have patients do a complete bacteriocidal washing out of the toilet bowl, as well as clean surface areas and especially toothbrushes.” Keeping the bowl closed when not in use is important too in preventing “fecal-oral transmission of remnants” of toilet contents, he adds.

The new papers add to other reports suggesting that virus-bearing droplets may reach people in various ways, Johnson said. “Maybe the virus isn’t only spread by a cough or a sneeze.”

The researchers and commentator have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal-oral transmission may be part of the COVID-19 clinical picture, according to two reports published in Gastroenterology. The researchers find that RNA and proteins from SARS-CoV-2, the viral cause of COVID-19, are shed in feces early in infection and persist after respiratory symptoms abate.

But the discovery is preliminary. “There is evidence of the virus in stool, but not evidence of infectious virus,” David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, told Medscape Medical News.

The findings are not entirely unexpected. Both of the coronaviruses behind SARS and MERS are shed in stool, Jinyang Gu, MD, from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in Shanghai, China, and colleagues, note in one of the newly published articles.

In addition, as COVID-19 spread beyond China, clinicians began noticing initial mild gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in some patients, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, preceding the hallmark fever, dry cough, and dyspnea. The first patient diagnosed in the United States with COVID-19 reported having 2 days of nausea and vomiting, with viral RNA detected in fecal and respiratory specimens, according to an earlier report.

Gu and colleagues warn that initial investigations would likely have not considered cases that manifested initially only as mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

Although early reports indicated that only about 10% of people with COVID-19 have GI symptoms, it isn’t known whether some infected individuals have only GI symptoms, Johnson said.

The GI manifestations are consistent with the distribution of ACE2 receptors, which serve as entry points for SARS-CoV-2, as well as SARS-CoV-1, which causes SARS. The receptors are most abundant in the cell membranes of lung AT2 cells, as well as in enterocytes in the ileum and colon.

“Altogether, many efforts should be made to be alert on the initial digestive symptoms of COVID-19 for early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation and early intervention,” Gu and colleagues conclude.

But Johnson cautions, “gastroenterologists are not the ones managing diagnosis of COVID-19. It is diagnosed as a respiratory illness, but we are seeing concomitant gastrointestinal shedding in stool and saliva, and GI symptoms.”

Samples From 73 Patients Studied

In the second article published, Fei Xiao, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong Province, China, and colleagues report detecting viral RNA in samples from the mouths, noses, throats, urine, and feces of 73 patients hospitalized during the first 2 weeks of February.

Of the 73 hospitalized patients, 39 (53.24%; 25 males and 14 females) had viral RNA in their feces, present from 1 to 12 days. Seventeen (23.29%) of the patients continued to have viral RNA in their stool after respiratory symptoms had improved.

One patient underwent endoscopy. There was no evidence of damage to the GI epithelium, but the clinicians detected slightly elevated levels of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

The researcher used laser scanning confocal microscopy to analyze samples taken during the endoscopy. They found evidence of both ACE2 receptors and viral nucleocapsid proteins in the gastric, duodenal, and rectal glandular epithelial cells.

Finding evidence of SARS-CoV-2 throughout the GI system, if not direct infectivity, suggests a fecal-oral route of transmission, the researchers conclude. “Our immunofluorescent data showed that ACE2 protein, a cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is abundantly expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelia, supporting the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cells.”

Detection of viral RNA at different time points in infection, they write, suggests that the virions are continually secreted and therefore likely infectious, which is under investigation. “Prevention of fecal-oral transmission should be taken into consideration to control the spread of the virus,” they write.

Current recommendations do not require that patients’ fecal samples be tested before being considered noninfectious. However, given their findings and evidence from other studies, Xiao and colleagues recommend that real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing of fecal samples be added to current protocols.

Johnson offers practical suggestions based on the “potty hygiene” suggestions he gives to patients dealing with fecal shedding in Clostridioides difficile infection.

“To combat the microaerosolization of C. diff spores, I have patients do a complete bacteriocidal washing out of the toilet bowl, as well as clean surface areas and especially toothbrushes.” Keeping the bowl closed when not in use is important too in preventing “fecal-oral transmission of remnants” of toilet contents, he adds.

The new papers add to other reports suggesting that virus-bearing droplets may reach people in various ways, Johnson said. “Maybe the virus isn’t only spread by a cough or a sneeze.”

The researchers and commentator have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal-oral transmission may be part of the COVID-19 clinical picture, according to two reports published in Gastroenterology. The researchers find that RNA and proteins from SARS-CoV-2, the viral cause of COVID-19, are shed in feces early in infection and persist after respiratory symptoms abate.

But the discovery is preliminary. “There is evidence of the virus in stool, but not evidence of infectious virus,” David A. Johnson, MD, professor of medicine and chief of gastroenterology at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine in Norfolk, told Medscape Medical News.

The findings are not entirely unexpected. Both of the coronaviruses behind SARS and MERS are shed in stool, Jinyang Gu, MD, from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine in Shanghai, China, and colleagues, note in one of the newly published articles.

In addition, as COVID-19 spread beyond China, clinicians began noticing initial mild gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in some patients, including diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, preceding the hallmark fever, dry cough, and dyspnea. The first patient diagnosed in the United States with COVID-19 reported having 2 days of nausea and vomiting, with viral RNA detected in fecal and respiratory specimens, according to an earlier report.

Gu and colleagues warn that initial investigations would likely have not considered cases that manifested initially only as mild gastrointestinal symptoms.

Although early reports indicated that only about 10% of people with COVID-19 have GI symptoms, it isn’t known whether some infected individuals have only GI symptoms, Johnson said.

The GI manifestations are consistent with the distribution of ACE2 receptors, which serve as entry points for SARS-CoV-2, as well as SARS-CoV-1, which causes SARS. The receptors are most abundant in the cell membranes of lung AT2 cells, as well as in enterocytes in the ileum and colon.

“Altogether, many efforts should be made to be alert on the initial digestive symptoms of COVID-19 for early detection, early diagnosis, early isolation and early intervention,” Gu and colleagues conclude.

But Johnson cautions, “gastroenterologists are not the ones managing diagnosis of COVID-19. It is diagnosed as a respiratory illness, but we are seeing concomitant gastrointestinal shedding in stool and saliva, and GI symptoms.”

Samples From 73 Patients Studied

In the second article published, Fei Xiao, MD, of Sun Yat-sen University in Guangdong Province, China, and colleagues report detecting viral RNA in samples from the mouths, noses, throats, urine, and feces of 73 patients hospitalized during the first 2 weeks of February.

Of the 73 hospitalized patients, 39 (53.24%; 25 males and 14 females) had viral RNA in their feces, present from 1 to 12 days. Seventeen (23.29%) of the patients continued to have viral RNA in their stool after respiratory symptoms had improved.

One patient underwent endoscopy. There was no evidence of damage to the GI epithelium, but the clinicians detected slightly elevated levels of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

The researcher used laser scanning confocal microscopy to analyze samples taken during the endoscopy. They found evidence of both ACE2 receptors and viral nucleocapsid proteins in the gastric, duodenal, and rectal glandular epithelial cells.

Finding evidence of SARS-CoV-2 throughout the GI system, if not direct infectivity, suggests a fecal-oral route of transmission, the researchers conclude. “Our immunofluorescent data showed that ACE2 protein, a cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is abundantly expressed in the glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelia, supporting the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into the host cells.”

Detection of viral RNA at different time points in infection, they write, suggests that the virions are continually secreted and therefore likely infectious, which is under investigation. “Prevention of fecal-oral transmission should be taken into consideration to control the spread of the virus,” they write.

Current recommendations do not require that patients’ fecal samples be tested before being considered noninfectious. However, given their findings and evidence from other studies, Xiao and colleagues recommend that real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) testing of fecal samples be added to current protocols.

Johnson offers practical suggestions based on the “potty hygiene” suggestions he gives to patients dealing with fecal shedding in Clostridioides difficile infection.

“To combat the microaerosolization of C. diff spores, I have patients do a complete bacteriocidal washing out of the toilet bowl, as well as clean surface areas and especially toothbrushes.” Keeping the bowl closed when not in use is important too in preventing “fecal-oral transmission of remnants” of toilet contents, he adds.

The new papers add to other reports suggesting that virus-bearing droplets may reach people in various ways, Johnson said. “Maybe the virus isn’t only spread by a cough or a sneeze.”

The researchers and commentator have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk factors for death from COVID-19 identified in Wuhan patients

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients who did not survive hospitalization for COVID-19 in Wuhan were more likely to be older, have comorbidities, and elevated D-dimer, according to the first study to examine risk factors associated with death among adults hospitalized with COVID-19. “Older age, showing signs of sepsis on admission, underlying diseases like high blood pressure and diabetes, and the prolonged use of noninvasive ventilation were important factors in the deaths of these patients,” coauthor Zhibo Liu said in a news release. Abnormal blood clotting was part of the clinical picture too.

Fei Zhou, MD, from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, and colleagues conducted a retrospective, observational, multicenter cohort study of 191 patients, 137 of whom were discharged and 54 of whom died in the hospital.

The study, published online today in The Lancet, included all adult inpatients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from Jinyintan Hospital and Wuhan Pulmonary Hospital who had been discharged or died by January 31 of this year. Severely ill patients in the province were transferred to these hospitals until February 1.

The researchers compared demographic, clinical, treatment, and laboratory data from electronic medical records between survivors and those who succumbed to the disease. The analysis also tested serial samples for viral RNA. Overall, 91 (48%) of the 191 patients had comorbidity. Most common was hypertension (30%), followed by diabetes (19%) and coronary heart disease (8%).

The odds of dying in the hospital increased with age (odds ratio 1.10; 95% confidence interval, 1.03-1.17; per year increase in age), higher Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score (5.65, 2.61-12.23; P < .0001), and D-dimer level exceeding 1 mcg/L on admission. The SOFA was previously called the “sepsis-related organ failure assessment score” and assesses rate of organ failure in intensive care units. Elevated D-dimer indicates increased risk of abnormal blood clotting, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Nonsurvivors compared with survivors had higher frequencies of respiratory failure (98% vs 36%), sepsis (100%, vs 42%), and secondary infections (50% vs 1%).

The average age of survivors was 52 years compared to 69 for those who died. Liu cited weakening of the immune system and increased inflammation, which damages organs and also promotes viral replication, as explanations for the age effect.

From the time of initial symptoms, median time to discharge from the hospital was 22 days. Average time to death was 18.5 days.

Fever persisted for a median of 12 days among all patients, and cough persisted for a median 19 days; 45% of the survivors were still coughing on discharge. In survivors, shortness of breath improved after 13 days, but persisted until death in the others.

Viral shedding persisted for a median duration of 20 days in survivors, ranging from 8 to 37. The virus (SARS-CoV-2) was detectable in nonsurvivors until death. Antiviral treatment did not curtail viral shedding.

But the viral shedding data come with a caveat. “The extended viral shedding noted in our study has important implications for guiding decisions around isolation precautions and antiviral treatment in patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection. However, we need to be clear that viral shedding time should not be confused with other self-isolation guidance for people who may have been exposed to COVID-19 but do not have symptoms, as this guidance is based on the incubation time of the virus,” explained colead author Bin Cao.

“Older age, elevated D-dimer levels, and high SOFA score could help clinicians to identify at an early stage those patients with COVID-19 who have poor prognosis. Prolonged viral shedding provides the rationale for a strategy of isolation of infected patients and optimal antiviral interventions in the future,” the researchers conclude.

A limitation in interpreting the findings of the study is that hospitalized patients do not represent the entire infected population. The researchers caution that “the number of deaths does not reflect the true mortality of COVID-19.” They also note that they did not have enough genetic material to accurately assess duration of viral shedding.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

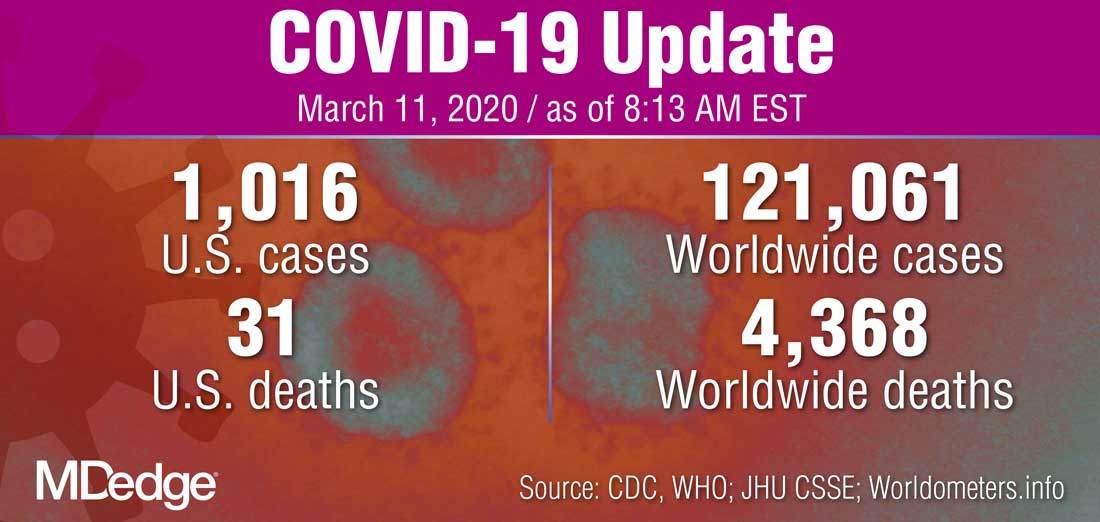

WHO declares COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic

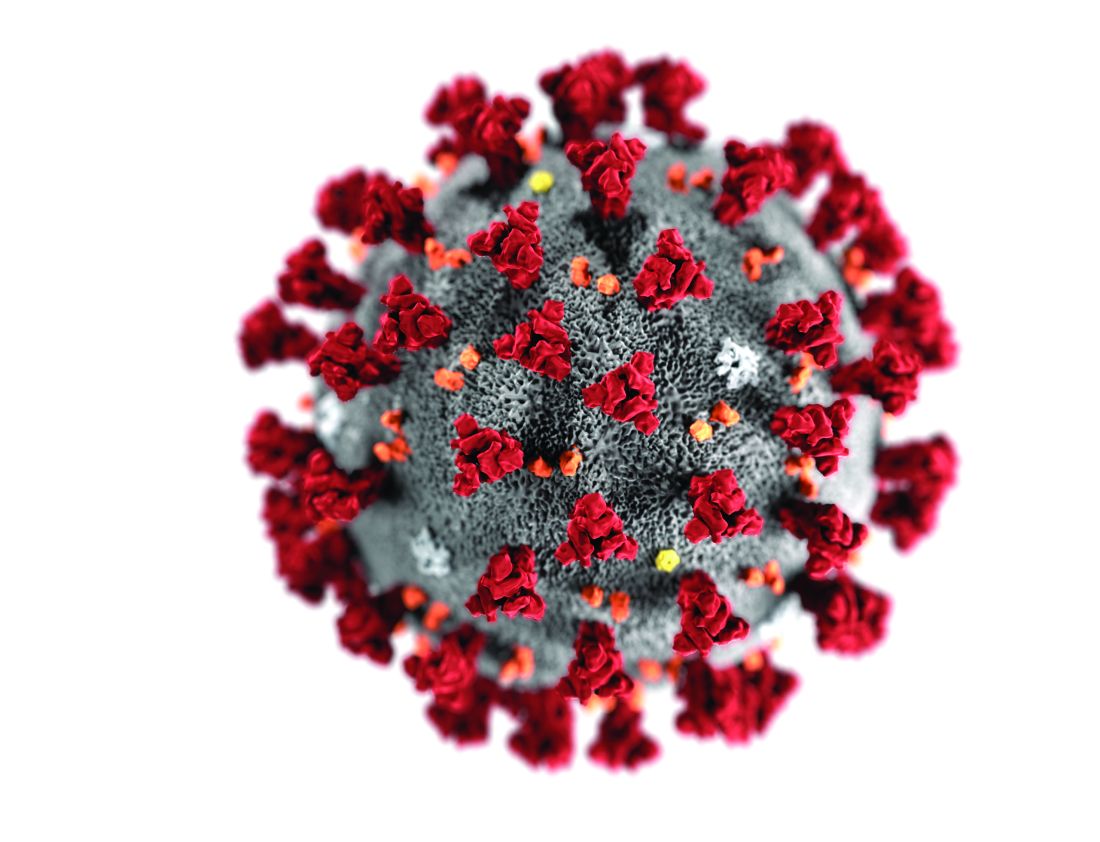

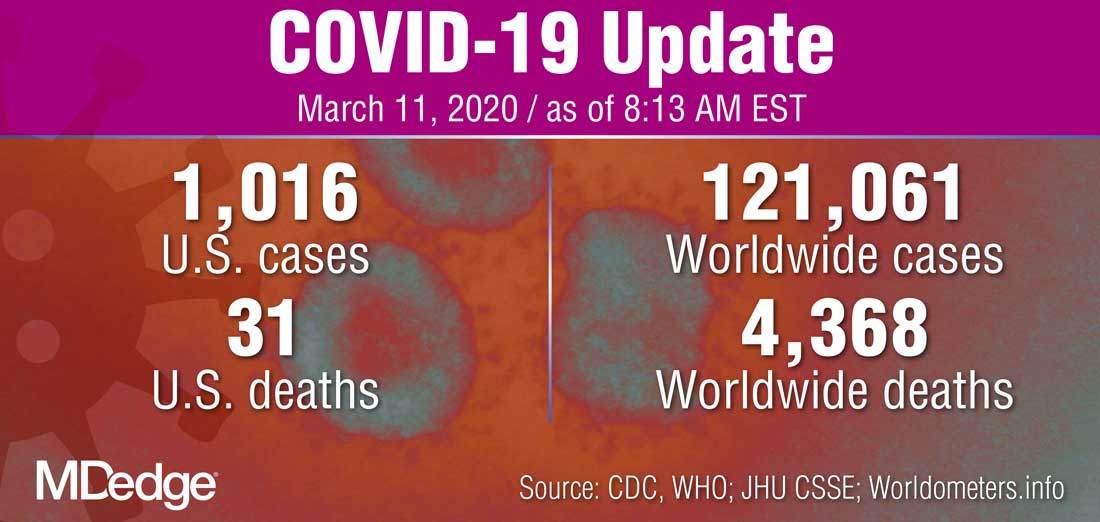

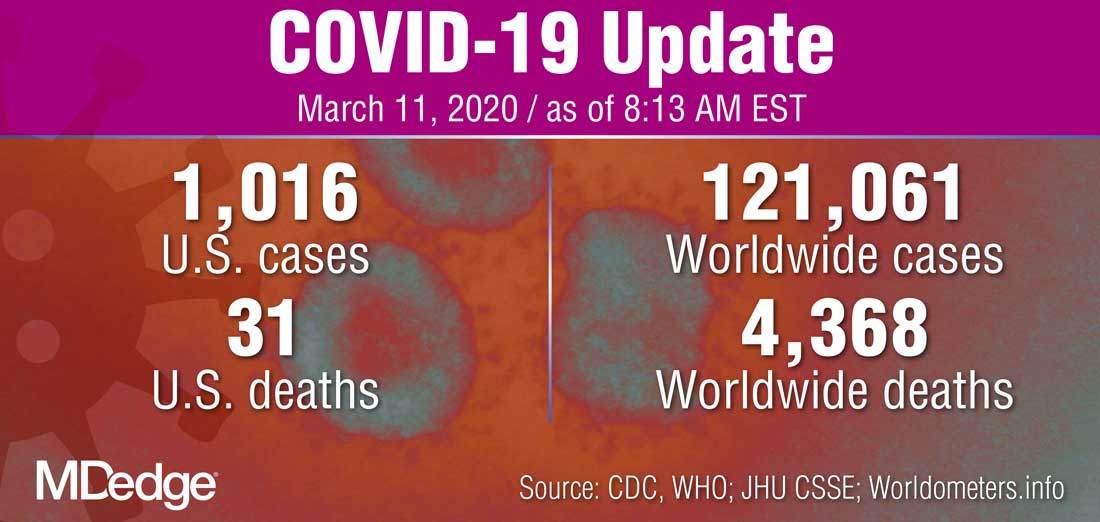

The World Health Organization has formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.

“WHO has been assessing this outbreak around the clock and we are deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a March 11 press briefing. “We therefore made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.”

He noted that this is the first time a coronavirus has been seen as a pandemic.

The Director-General cautioned that just looking at the number of countries affected, 114 countries, “does not tell the full story. ... We cannot say this loudly enough, or clearly enough, or often enough: All countries can still change the course of this pandemic.”

He reiterated the need for a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach to dealing with this, including taking precautions such as isolating, testing, and treating every case and tracing every contact, as well as readying hospitals and health care professionals.

“Let’s look out for each other, because we need each other,” he said.

The World Health Organization has formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.

“WHO has been assessing this outbreak around the clock and we are deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a March 11 press briefing. “We therefore made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.”

He noted that this is the first time a coronavirus has been seen as a pandemic.

The Director-General cautioned that just looking at the number of countries affected, 114 countries, “does not tell the full story. ... We cannot say this loudly enough, or clearly enough, or often enough: All countries can still change the course of this pandemic.”

He reiterated the need for a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach to dealing with this, including taking precautions such as isolating, testing, and treating every case and tracing every contact, as well as readying hospitals and health care professionals.

“Let’s look out for each other, because we need each other,” he said.

The World Health Organization has formally declared the COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic.

“WHO has been assessing this outbreak around the clock and we are deeply concerned both by the alarming levels of spread and severity, and by the alarming levels of inaction,” WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said during a March 11 press briefing. “We therefore made the assessment that COVID-19 can be characterized as a pandemic.”

He noted that this is the first time a coronavirus has been seen as a pandemic.

The Director-General cautioned that just looking at the number of countries affected, 114 countries, “does not tell the full story. ... We cannot say this loudly enough, or clearly enough, or often enough: All countries can still change the course of this pandemic.”

He reiterated the need for a whole-of-government and a whole-of-society approach to dealing with this, including taking precautions such as isolating, testing, and treating every case and tracing every contact, as well as readying hospitals and health care professionals.

“Let’s look out for each other, because we need each other,” he said.

Managing children’s fear, anxiety in the age of COVID-19

With coronavirus disease (COVID-19) reaching epidemic proportions, many US children are growing increasingly anxious about what this means for their own health and safety and that of their friends and family.

The constantly changing numbers of people affected by the virus and the evolving situation mean daily life for many children is affected in some way, with school trips, sports tournaments, and family vacations being postponed or canceled.

All children may have a heightened level of worry, and some who are normally anxious might be obsessing more about handwashing or getting sick.

Experts say there are ways to manage this fear to help children feel safe and appropriately informed.

Clinicians and other adults should provide children with honest and accurate information geared to their age and developmental level, said David Fassler, MD, clinical professor of psychiatry, University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine, Burlington, and member of the Consumer Issues Committee of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

That said, it’s also acceptable to let children know that some questions can’t be answered, said Fassler.

Be truthful, calm

“This is partly because the information keeps changing as we learn more about how the virus spreads, how to best protect communities, and how to treat people who get sick,” he added.

Clinicians and parents should remind children “that there are a lot of adults who are working very hard to keep them safe,” said Eli R. Lebowitz, PhD, associate professor in the Child Study Center, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, who directs a program for anxiety.

It’s important for adults to pay attention not only to what they say to children but also how they say it, said Lebowitz. He highlighted the importance of talking about the virus “in a calm and matter-of-fact way” rather than in an anxious way.

“If you look scared or tense or your voice is conveying that you’re really scared, the child is going to absorb that and feel anxious as well,” he noted.

This advice also applies when adults are discussing the issue among themselves. They should be aware that “children are listening” and are picking up any anxiety or panic adults are expressing.

Children are soaking up information about this virus from the Internet, the media, friends, teachers, and elsewhere. Lebowitz suggests asking children what they have already heard, which provides an opportunity to correct rumors and inaccurate information.

“A child might have a very inflated sense of what the actual risk is. For example, they may think that anyone who gets the virus dies,” he said.

Myth busting

Adults should let children know that not everything they hear from friends or on the Internet “is necessarily correct,” he added.

Some children who have experienced serious illness or losses may be particularly vulnerable to experiencing intense reactions to graphic news reports or images of illness or death and may need extra support, said Fassler.

Adults could use the “framework of knowledge” that children already have, said Lebowitz. He noted that all children are aware of sickness.

“They know people get sick, and they themselves have probably been sick, so you can tell them that this is a sickness like a bad flu,” he said.

Children should be encouraged to approach adults they trust, such as their pediatrician, a parent, or a teacher, with their questions, said Lebowitz. “Those are the people who are able to give them the most accurate information.”

Fassler noted that accurate, up-to-date information is available via fact sheets developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization.

Although it’s helpful and appropriate to be reassuring, Fassler advises not to make unrealistic promises.

“It’s fine to tell kids that you’ll deal with whatever happens, even if it means altering travel plans or work schedules, but you can’t promise that no one in your state or community will get sick,” he said.

Maintain healthy habits

Physicians and other adults can tell children “in an age-appropriate way” how the virus is transmitted and what the symptoms are, but it’s important to emphasize that most people who are sick don’t have COVID-19, said Lebowitz.

“I would emphasize that the people who are the sickest are the elderly who are already sick, rather than healthy younger people,” he said.

Lebowitz recommends continuing to follow guidelines on staying healthy, including coughing into a sleeve instead of your hand and regular handwashing.

It’s also important at this time for children to maintain healthy habits – getting enough physical activity and sleep, eating well, and being outside – because this regime will go a long way toward reducing anxiety, said Lebowitz. Deep breathing and muscle-relaxing exercises can also help, he said.

Lebowitz also suggests maintaining a supportive attitude and showing “some acceptance and validation of what children are feeling, as well as some confidence that they can cope and tolerate feeling uncomfortable sometimes, that they can handle some anxiety.”

While accepting that the child could be anxious, it’s important not to encourage excessive avoidance or unhealthy coping strategies. Fassler and Lebowitz agree that children who are overly anxious or preoccupied with concerns about the coronavirus should be evaluated by a trained, qualified mental health professional.

Signs that a child may need additional help include ongoing sleep difficulties, intrusive thoughts or worries, obsessive-compulsive behaviors, or reluctance or refusal to go to school, said Fassler.

The good news is that most children are resilient, said Fassler. “They’ll adjust, adapt, and go on with their lives.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

With coronavirus disease (COVID-19) reaching epidemic proportions, many US children are growing increasingly anxious about what this means for their own health and safety and that of their friends and family.

The constantly changing numbers of people affected by the virus and the evolving situation mean daily life for many children is affected in some way, with school trips, sports tournaments, and family vacations being postponed or canceled.

All children may have a heightened level of worry, and some who are normally anxious might be obsessing more about handwashing or getting sick.

Experts say there are ways to manage this fear to help children feel safe and appropriately informed.