User login

Long COVID could spell kidney troubles down the line

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Physicians caring for COVID-19 survivors should routinely check kidney function, which is often damaged by the SARS-CoV-2 virus months after both severe and milder cases, new research indicates.

The largest study to date with the longest follow-up of COVID-19-related kidney outcomes also found that every type of kidney problem, including end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), was far more common in COVID-19 survivors who were admitted to the ICU or experienced acute kidney injury (AKI) while hospitalized.

Researchers analyzed U.S. Veterans Health Administration data from more than 1.7 million patients, including more than 89,000 who tested positive for COVID-19, for the study, which was published online Sept. 1, 2021, in the Journal of the American Society of Nephrology.

The risk of kidney problems “is more robust or pronounced in people who have had severe infection, but present in even asymptomatic and mild disease, which shouldn’t be discounted. Those people represent the majority of those with COVID-19,” said senior author Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the Veteran Affairs St. Louis Health Care System.

“That’s why the results are important, because even in people with mild disease to start with, the risk of kidney problems is not trivial,” he told this news organization. “It’s smaller than in people who were in the ICU, but it’s not ... zero.”

Experts aren’t yet certain how COVID-19 can damage the kidneys, hypothesizing that several factors may be at play. The virus may directly infect kidney cells rich in ACE2 receptors, which are key to infection, said nephrologist F. Perry Wilson, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and a member of Medscape’s advisory board.

Kidneys might also be particularly vulnerable to the inflammatory cascade or blood clotting often seen in COVID-19, Dr. Al-Aly and Wilson both suggested.

COVID-19 survivors more likely to have kidney damage than controls

“A lot of health systems either have or are establishing post-COVID care clinics, which we think should definitely incorporate a kidney component,” Dr. Al-Aly advised. “They should check patients’ blood and urine for kidney problems.”

This is particularly important because “kidney problems, for the most part, are painless and silent,” he added.

“Realizing 2 years down the road that someone has ESKD, where they need dialysis or a kidney transplant, is what we don’t want. We don’t want this to be unrecognized, uncared for, unattended to,” he said.

Dr. Al-Aly and colleagues evaluated VA health system records, including data from 89,216 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 between March 2020 and March 2021, as well as 1.7 million controls who did not have COVID-19. Over a median follow-up of about 5.5 months, participants’ estimated glomerular filtration rate and serum creatinine levels were tracked to assess kidney health and outcomes according to infection severity.

Results were striking, with COVID-19 survivors about one-third more likely than controls to have kidney damage or significant declines in kidney function between 1 and 6 months after infection. More than 4,700 COVID-19 survivors had lost at least 30% of their kidney function within a year, and these patients were 25% more likely to reach that level of decline than controls.

Additionally, COVID-19 survivors were nearly twice as likely to experience AKI and almost three times as likely to be diagnosed with ESKD as controls.

If your patient had COVID-19, ‘it’s reasonable to check kidney function’

“This information tells us that if your patient was sick with COVID-19 and comes for follow-up visits, it’s reasonable to check their kidney function,” Dr. Wilson, who was not involved with the research, told this news organization.

“Even for patients who were not hospitalized, if they were laid low or dehydrated ... it should be part of the post-COVID care package,” he said.

If just a fraction of the millions of COVID-19 survivors in the United States develop long-term kidney problems, the ripple effect on American health care could be substantial, Dr. Wilson and Dr. Al-Aly agreed.

“We’re still living in a pandemic, so it’s hard to tell the total impact,” Dr. Al-Aly said. “But this ultimately will contribute to a rise in burden of kidney disease. This and other long COVID manifestations are going to alter the landscape of clinical care and health care in the United States for a decade or more.”

Because renal problems can limit a patient’s treatment options for other major diseases, including diabetes and cancer, COVID-related kidney damage can ultimately impact survivability.

“There are a lot of medications you can’t use in people with advanced kidney problems,” Dr. Al-Aly said.

The main study limitation was that patients were mostly older White men (median age, 68 years), although more than 9,000 women were included in the VA data, Dr. Al-Aly noted. Additionally, controls were more likely to be younger, Black, living in long-term care, and have higher rates of chronic health conditions and medication use.

The experts agreed that ongoing research tracking kidney outcomes is crucial for years to come.

“We also need to be following a cohort of these patients as part of a research protocol where they come in every 6 months for a standard set of lab tests to really understand what’s going on with their kidneys,” Dr. Wilson said.

“Lastly – and a much tougher sell – is we need biopsies. It’s very hard to infer what’s going on in complex disease with the kidneys without biopsy tissue,” he added.

The study was funded by the American Society of Nephrology and the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Al-Aly and Dr. Wilson reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medical education must takes broader view of disabilities

“All physicians, regardless of specialty, will work with patients with disabilities,” Corrie Harris, MD, of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said in a plenary session presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Disabilities vary in their visibility, from cognitive and sensory impairments that are not immediately obvious to an obvious physical disability, she said.

One in four adults and one in six children in the United States has a disability, said Dr. Harris. The prevalence of disability increases with age, but occurs across the lifespan, and will likely increase in the future with greater improvements in health care overall.

Dr. Harris reviewed the current conceptual model that forms the basis for the World Health Organization definition of functioning disability. This “functional model” defines disability as caused by interactions between health conditions and the environment, and the response is to “prioritize function to meet patient goals,” Dr. Harris said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

This model is based on collaboration between health care providers and their patients with disabilities, and training is important to help providers make this collaboration successful, said Dr. Harris. Without training, physicians may be ineffective in communicating with patients with disabilities by not speaking directly to the patient, not speaking in a way the patient can understand clearly, and not providing accessible patient education materials. Physicians also tend to minimize the extent of the patient’s expertise in their own condition based on their lived experiences, and tend to underestimate the abilities of patients with disabilities.

However, direct experience with disabled patients and an understanding of the health disparities they endure can help physicians look at these patients “through a more intersectional lens,” that also takes into account social determinants of health, Dr. Harris said. “I have found that people with disabilities are the best teachers about disability, because they have expertise that comes from their lived experience.”

Patients are the best teachers

Several initiatives are helping physicians to bridge this gap in understanding and reduce disparities in care. One such program is FRAME: Faces Redefining the Art of Medical Education. FRAME is a web-based film library designed to present medical information to health care providers in training, clinicians, families, and communities in a dignified and humanizing way. FRAME was developed in part by fashion photographer Rick Guidotti, who was inspired after meeting a young woman with albinism to create Positive Exposure, an ongoing project featuring children and adolescents with various disabilities.

FRAME films are “short films presenting all the basic hallmark characteristics of a certain genetic condition, but presented by somebody living with that condition,” said Mr. Guidotti in his presentation during the session.

The National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine (NCIDM) is designed to incorporate care for individuals with disabilities into medical education. NCIDM is a project created by the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD).

“The need for this program is that there is no U.S. requirement for medical schools to teach about intellectual and developmental disabilities,” Priya Chandan, MD, also of the University of Louisville, said in her presentation during the session. “Approximately 81% of graduating medical students have no training in caring for adults with disabilities,” said Dr. Chandan, who serves as director of the NCIDM.

The current NCIDM was created as a 5-year partnership between the AADMD and Special Olympics, supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Chandan said. The purpose was to provide training to medical students in the field of developmental medicine, meaning the care of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDD) across the lifespan. The AADMD has expanded to 26 medical schools in the United States and will reach approximately 4,000 medical students by the conclusion of the current initiative.

One challenge in medical education is getting past the idea that people living with disabilities need to be fixed, said Dr. Chandan. The NCIDM approach reflects Mr. Guidotti’s approach in both the FRAME initiatives and his Positive Exposure foundation, with a focus on treating people as people, and letting individuals with disabilities represent themselves.

Dr. Chandan described the NCIDM curriculum as allowing for flexible teaching methodologies and materials, as long as they meet the NCIDM-created learning goals and objectives. The curriculum also includes standardized evaluations. Each NCIDM program in a participating medical school includes a faculty champion, and the curriculum supports meeting people with IDD not only inside medical settings, but also outside in the community.

NCIDM embraces the idea of community-engaged scholarship, which Dr. Chandan defined as “a form of scholarship that directly benefits the community and is consistent with university and unit missions.” This method combined teaching and conducting research while providing a service to the community.

The next steps for the current NCIDM initiative are to complete collection of data and course evaluations from participating schools by early 2022, followed by continued dissemination and collaboration through AADMD.

Overall, the content of the curriculum explores how and where IDD fits into clinical care, Dr. Chandan said, who also emphasized the implications of communication. “How we think affects how we communicate,” she added. Be mindful of the language used to talk to and about patients with disabilities, both to colleagues and to learners.

When talking to the patient, find something in common, beyond the diagnosis, said Dr. Chandan. Remember that some disabilities are visible and some are not. “Treat people with respect, because you won’t know what their functional level is just by looking,” she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“All physicians, regardless of specialty, will work with patients with disabilities,” Corrie Harris, MD, of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said in a plenary session presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Disabilities vary in their visibility, from cognitive and sensory impairments that are not immediately obvious to an obvious physical disability, she said.

One in four adults and one in six children in the United States has a disability, said Dr. Harris. The prevalence of disability increases with age, but occurs across the lifespan, and will likely increase in the future with greater improvements in health care overall.

Dr. Harris reviewed the current conceptual model that forms the basis for the World Health Organization definition of functioning disability. This “functional model” defines disability as caused by interactions between health conditions and the environment, and the response is to “prioritize function to meet patient goals,” Dr. Harris said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

This model is based on collaboration between health care providers and their patients with disabilities, and training is important to help providers make this collaboration successful, said Dr. Harris. Without training, physicians may be ineffective in communicating with patients with disabilities by not speaking directly to the patient, not speaking in a way the patient can understand clearly, and not providing accessible patient education materials. Physicians also tend to minimize the extent of the patient’s expertise in their own condition based on their lived experiences, and tend to underestimate the abilities of patients with disabilities.

However, direct experience with disabled patients and an understanding of the health disparities they endure can help physicians look at these patients “through a more intersectional lens,” that also takes into account social determinants of health, Dr. Harris said. “I have found that people with disabilities are the best teachers about disability, because they have expertise that comes from their lived experience.”

Patients are the best teachers

Several initiatives are helping physicians to bridge this gap in understanding and reduce disparities in care. One such program is FRAME: Faces Redefining the Art of Medical Education. FRAME is a web-based film library designed to present medical information to health care providers in training, clinicians, families, and communities in a dignified and humanizing way. FRAME was developed in part by fashion photographer Rick Guidotti, who was inspired after meeting a young woman with albinism to create Positive Exposure, an ongoing project featuring children and adolescents with various disabilities.

FRAME films are “short films presenting all the basic hallmark characteristics of a certain genetic condition, but presented by somebody living with that condition,” said Mr. Guidotti in his presentation during the session.

The National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine (NCIDM) is designed to incorporate care for individuals with disabilities into medical education. NCIDM is a project created by the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD).

“The need for this program is that there is no U.S. requirement for medical schools to teach about intellectual and developmental disabilities,” Priya Chandan, MD, also of the University of Louisville, said in her presentation during the session. “Approximately 81% of graduating medical students have no training in caring for adults with disabilities,” said Dr. Chandan, who serves as director of the NCIDM.

The current NCIDM was created as a 5-year partnership between the AADMD and Special Olympics, supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Chandan said. The purpose was to provide training to medical students in the field of developmental medicine, meaning the care of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDD) across the lifespan. The AADMD has expanded to 26 medical schools in the United States and will reach approximately 4,000 medical students by the conclusion of the current initiative.

One challenge in medical education is getting past the idea that people living with disabilities need to be fixed, said Dr. Chandan. The NCIDM approach reflects Mr. Guidotti’s approach in both the FRAME initiatives and his Positive Exposure foundation, with a focus on treating people as people, and letting individuals with disabilities represent themselves.

Dr. Chandan described the NCIDM curriculum as allowing for flexible teaching methodologies and materials, as long as they meet the NCIDM-created learning goals and objectives. The curriculum also includes standardized evaluations. Each NCIDM program in a participating medical school includes a faculty champion, and the curriculum supports meeting people with IDD not only inside medical settings, but also outside in the community.

NCIDM embraces the idea of community-engaged scholarship, which Dr. Chandan defined as “a form of scholarship that directly benefits the community and is consistent with university and unit missions.” This method combined teaching and conducting research while providing a service to the community.

The next steps for the current NCIDM initiative are to complete collection of data and course evaluations from participating schools by early 2022, followed by continued dissemination and collaboration through AADMD.

Overall, the content of the curriculum explores how and where IDD fits into clinical care, Dr. Chandan said, who also emphasized the implications of communication. “How we think affects how we communicate,” she added. Be mindful of the language used to talk to and about patients with disabilities, both to colleagues and to learners.

When talking to the patient, find something in common, beyond the diagnosis, said Dr. Chandan. Remember that some disabilities are visible and some are not. “Treat people with respect, because you won’t know what their functional level is just by looking,” she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“All physicians, regardless of specialty, will work with patients with disabilities,” Corrie Harris, MD, of the University of Louisville (Ky.), said in a plenary session presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Disabilities vary in their visibility, from cognitive and sensory impairments that are not immediately obvious to an obvious physical disability, she said.

One in four adults and one in six children in the United States has a disability, said Dr. Harris. The prevalence of disability increases with age, but occurs across the lifespan, and will likely increase in the future with greater improvements in health care overall.

Dr. Harris reviewed the current conceptual model that forms the basis for the World Health Organization definition of functioning disability. This “functional model” defines disability as caused by interactions between health conditions and the environment, and the response is to “prioritize function to meet patient goals,” Dr. Harris said at the meeting, sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

This model is based on collaboration between health care providers and their patients with disabilities, and training is important to help providers make this collaboration successful, said Dr. Harris. Without training, physicians may be ineffective in communicating with patients with disabilities by not speaking directly to the patient, not speaking in a way the patient can understand clearly, and not providing accessible patient education materials. Physicians also tend to minimize the extent of the patient’s expertise in their own condition based on their lived experiences, and tend to underestimate the abilities of patients with disabilities.

However, direct experience with disabled patients and an understanding of the health disparities they endure can help physicians look at these patients “through a more intersectional lens,” that also takes into account social determinants of health, Dr. Harris said. “I have found that people with disabilities are the best teachers about disability, because they have expertise that comes from their lived experience.”

Patients are the best teachers

Several initiatives are helping physicians to bridge this gap in understanding and reduce disparities in care. One such program is FRAME: Faces Redefining the Art of Medical Education. FRAME is a web-based film library designed to present medical information to health care providers in training, clinicians, families, and communities in a dignified and humanizing way. FRAME was developed in part by fashion photographer Rick Guidotti, who was inspired after meeting a young woman with albinism to create Positive Exposure, an ongoing project featuring children and adolescents with various disabilities.

FRAME films are “short films presenting all the basic hallmark characteristics of a certain genetic condition, but presented by somebody living with that condition,” said Mr. Guidotti in his presentation during the session.

The National Curriculum Initiative in Developmental Medicine (NCIDM) is designed to incorporate care for individuals with disabilities into medical education. NCIDM is a project created by the American Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry (AADMD).

“The need for this program is that there is no U.S. requirement for medical schools to teach about intellectual and developmental disabilities,” Priya Chandan, MD, also of the University of Louisville, said in her presentation during the session. “Approximately 81% of graduating medical students have no training in caring for adults with disabilities,” said Dr. Chandan, who serves as director of the NCIDM.

The current NCIDM was created as a 5-year partnership between the AADMD and Special Olympics, supported in part by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Chandan said. The purpose was to provide training to medical students in the field of developmental medicine, meaning the care of individuals with intellectual/developmental disabilities (IDD) across the lifespan. The AADMD has expanded to 26 medical schools in the United States and will reach approximately 4,000 medical students by the conclusion of the current initiative.

One challenge in medical education is getting past the idea that people living with disabilities need to be fixed, said Dr. Chandan. The NCIDM approach reflects Mr. Guidotti’s approach in both the FRAME initiatives and his Positive Exposure foundation, with a focus on treating people as people, and letting individuals with disabilities represent themselves.

Dr. Chandan described the NCIDM curriculum as allowing for flexible teaching methodologies and materials, as long as they meet the NCIDM-created learning goals and objectives. The curriculum also includes standardized evaluations. Each NCIDM program in a participating medical school includes a faculty champion, and the curriculum supports meeting people with IDD not only inside medical settings, but also outside in the community.

NCIDM embraces the idea of community-engaged scholarship, which Dr. Chandan defined as “a form of scholarship that directly benefits the community and is consistent with university and unit missions.” This method combined teaching and conducting research while providing a service to the community.

The next steps for the current NCIDM initiative are to complete collection of data and course evaluations from participating schools by early 2022, followed by continued dissemination and collaboration through AADMD.

Overall, the content of the curriculum explores how and where IDD fits into clinical care, Dr. Chandan said, who also emphasized the implications of communication. “How we think affects how we communicate,” she added. Be mindful of the language used to talk to and about patients with disabilities, both to colleagues and to learners.

When talking to the patient, find something in common, beyond the diagnosis, said Dr. Chandan. Remember that some disabilities are visible and some are not. “Treat people with respect, because you won’t know what their functional level is just by looking,” she concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PHM 2021

Choosing Wisely campaign targets waste and overuse in hospital pediatrics

“Health care spending and health care waste is a huge problem in the U.S., including for children,” Vivian Lee, MD, of Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, said in a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Data from a 2019 study suggested that approximately 25% of health care spending in the United States qualifies as “wasteful spending,” in categories such as overtesting, and unnecessary hospitalization, Dr. Lee said. “It is essential for physicians in hospitals to be stewards of high-value care,” she emphasized.

To combat wasteful spending and control health care costs, the Choosing Wisely campaign was created in 2012 as an initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. An ongoing goal of the campaign is to raise awareness among physicians and patients about potential areas of low-value services and overuse. The overall campaign includes clinician-driven recommendations from multiple medical organizations.

The PHM produced its first set of five recommendations in 2012, Dr. Lee said. These recommendations, titled “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question,” have been updated for 2021. The updated recommendations were created as a partnership among the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. A joint committee reviewed the latest evidence, and the updates were approved by the societies and published by the ABIM in January 2021.

“We think these recommendations truly reflect an exciting and evolving landscape for pediatric hospitalists,” Dr. Lee said. “There is a greater focus on opportunities to transition out of the hospital sooner, or avoid hospitalization altogether. There is an emphasis on antibiotic stewardship and a growing recognition of the impact that overuse may have on our vulnerable neonatal population,” she said. Several members of the Choosing Wisely panel presented the recommendations during the virtual presentation.

Revised recommendations

The new “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question” are as follows:

1. Do not prescribe IV antibiotics for predetermined durations for patients hospitalized with infections such as pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia. Consider early transition to oral antibiotics.

Many antibiotic doses used in clinical practice are preset durations that are not based on high-quality evidence, said Mike Tchou, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Colorado in Aurora. However, studies now show that earlier transition to enteral antibiotics can improve a range of outcomes including neonatal UTIs, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia, he said. Considering early transition based on a patient’s response can decrease adverse events, pain, length of stay, and health care costs, he explained.

2. Do not continue hospitalization in well-appearing febrile infants once bacterial cultures (i.e., blood, cerebrospinal, and/or urine) have been confirmed negative for 24-36 hours, if adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured.

Recent data indicate that continuing hospitalization beyond 24-36 hours of confirmed negative bacterial cultures does not improve clinical outcomes for well-appearing infants admitted for concern of serious bacterial infection, said Paula Soung, MD, of Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. In fact, “blood culture yield is highest in the first 12-36 hours after incubation with multiple studies demonstrating > 90% of pathogen cultures being positive by 24 hours,” Dr. Soung said. “If adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured, discharging well-appearing febrile infants at 24-36 hours after confirming cultures are negative has many positive outcomes,” she said.

3. Do not initiate phototherapy in term or late preterm well-appearing infants with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia if their bilirubin is below levels at which the AAP guidelines recommend treatment.

In making this recommendation, “we considered that the risk of kernicterus and cerebral palsy is extremely low in otherwise healthy term and late preterm newborns,” said Allison Holmes, MD, of Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Manchester, N.H. “Subthreshold phototherapy leads to unnecessary hospitalization and its associated costs and harms,” and data show that kernicterus generally occurs close to 40 mg/dL and occurs most often in infants with hemolysis, she added.

The evidence for the recommendations included data showing that, among other factors, 8.6 of 100,000 babies have a bilirubin greater than 30 mg/dL, said Dr. Holmes. Risks of using subthreshold phototherapy include increased length of stay, increased readmissions, and increased costs, as well as decreased breastfeeding, bonding with parents, and increased parental anxiety. “Adding prolonged hospitalization for an intervention that might not be necessary can be stressful for parents,” she said.

4. Do not use broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone for children hospitalized with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. Use narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin.

Michelle Lossius, MD, of the Shands Hospital for Children at the University of Florida, Gainesville, noted that the recommendations reflect IDSA guidelines from 2011 advising the use of ampicillin or penicillin for this population of children. More recent studies with large populations support the ability of narrow-spectrum antibiotics to limit the development of resistant organisms while achieving the same or better outcomes for children hospitalized with CAP, she said.

5. Do not start IV antibiotic therapy on well-appearing newborn infants with isolated risk factors for sepsis such as maternal chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, or untreated group-B streptococcal colonization. Use clinical tools such as an evidence-based sepsis risk calculator to guide management.

“This recommendation combines other recommendations,” said Prabi Rajbhandari, MD, of Akron (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. The evidence is ample, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of sepsis calculators to guide clinical management in sepsis patients, she said.

Data comparing periods before and after the adoption of a sepsis risk calculator showed a significant reduction in the use of blood cultures and antibiotics, she noted. Other risks of jumping to IV antibiotics include increased hospital stay, increased parental anxiety, and decreased parental bonding, Dr. Rajbhandari added.

Next steps include how to prioritize implementation, as well as deimplementation of outdated practices, said Francisco Alvarez, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif. “A lot of our practices were started without good evidence for why they should be done,” he said. Other steps include value improvement research; use of dashboards and benchmarking; involving other stakeholders including patients, families, and other health care providers; and addressing racial disparities, he concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“Health care spending and health care waste is a huge problem in the U.S., including for children,” Vivian Lee, MD, of Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, said in a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Data from a 2019 study suggested that approximately 25% of health care spending in the United States qualifies as “wasteful spending,” in categories such as overtesting, and unnecessary hospitalization, Dr. Lee said. “It is essential for physicians in hospitals to be stewards of high-value care,” she emphasized.

To combat wasteful spending and control health care costs, the Choosing Wisely campaign was created in 2012 as an initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. An ongoing goal of the campaign is to raise awareness among physicians and patients about potential areas of low-value services and overuse. The overall campaign includes clinician-driven recommendations from multiple medical organizations.

The PHM produced its first set of five recommendations in 2012, Dr. Lee said. These recommendations, titled “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question,” have been updated for 2021. The updated recommendations were created as a partnership among the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. A joint committee reviewed the latest evidence, and the updates were approved by the societies and published by the ABIM in January 2021.

“We think these recommendations truly reflect an exciting and evolving landscape for pediatric hospitalists,” Dr. Lee said. “There is a greater focus on opportunities to transition out of the hospital sooner, or avoid hospitalization altogether. There is an emphasis on antibiotic stewardship and a growing recognition of the impact that overuse may have on our vulnerable neonatal population,” she said. Several members of the Choosing Wisely panel presented the recommendations during the virtual presentation.

Revised recommendations

The new “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question” are as follows:

1. Do not prescribe IV antibiotics for predetermined durations for patients hospitalized with infections such as pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia. Consider early transition to oral antibiotics.

Many antibiotic doses used in clinical practice are preset durations that are not based on high-quality evidence, said Mike Tchou, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Colorado in Aurora. However, studies now show that earlier transition to enteral antibiotics can improve a range of outcomes including neonatal UTIs, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia, he said. Considering early transition based on a patient’s response can decrease adverse events, pain, length of stay, and health care costs, he explained.

2. Do not continue hospitalization in well-appearing febrile infants once bacterial cultures (i.e., blood, cerebrospinal, and/or urine) have been confirmed negative for 24-36 hours, if adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured.

Recent data indicate that continuing hospitalization beyond 24-36 hours of confirmed negative bacterial cultures does not improve clinical outcomes for well-appearing infants admitted for concern of serious bacterial infection, said Paula Soung, MD, of Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. In fact, “blood culture yield is highest in the first 12-36 hours after incubation with multiple studies demonstrating > 90% of pathogen cultures being positive by 24 hours,” Dr. Soung said. “If adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured, discharging well-appearing febrile infants at 24-36 hours after confirming cultures are negative has many positive outcomes,” she said.

3. Do not initiate phototherapy in term or late preterm well-appearing infants with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia if their bilirubin is below levels at which the AAP guidelines recommend treatment.

In making this recommendation, “we considered that the risk of kernicterus and cerebral palsy is extremely low in otherwise healthy term and late preterm newborns,” said Allison Holmes, MD, of Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Manchester, N.H. “Subthreshold phototherapy leads to unnecessary hospitalization and its associated costs and harms,” and data show that kernicterus generally occurs close to 40 mg/dL and occurs most often in infants with hemolysis, she added.

The evidence for the recommendations included data showing that, among other factors, 8.6 of 100,000 babies have a bilirubin greater than 30 mg/dL, said Dr. Holmes. Risks of using subthreshold phototherapy include increased length of stay, increased readmissions, and increased costs, as well as decreased breastfeeding, bonding with parents, and increased parental anxiety. “Adding prolonged hospitalization for an intervention that might not be necessary can be stressful for parents,” she said.

4. Do not use broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone for children hospitalized with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. Use narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin.

Michelle Lossius, MD, of the Shands Hospital for Children at the University of Florida, Gainesville, noted that the recommendations reflect IDSA guidelines from 2011 advising the use of ampicillin or penicillin for this population of children. More recent studies with large populations support the ability of narrow-spectrum antibiotics to limit the development of resistant organisms while achieving the same or better outcomes for children hospitalized with CAP, she said.

5. Do not start IV antibiotic therapy on well-appearing newborn infants with isolated risk factors for sepsis such as maternal chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, or untreated group-B streptococcal colonization. Use clinical tools such as an evidence-based sepsis risk calculator to guide management.

“This recommendation combines other recommendations,” said Prabi Rajbhandari, MD, of Akron (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. The evidence is ample, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of sepsis calculators to guide clinical management in sepsis patients, she said.

Data comparing periods before and after the adoption of a sepsis risk calculator showed a significant reduction in the use of blood cultures and antibiotics, she noted. Other risks of jumping to IV antibiotics include increased hospital stay, increased parental anxiety, and decreased parental bonding, Dr. Rajbhandari added.

Next steps include how to prioritize implementation, as well as deimplementation of outdated practices, said Francisco Alvarez, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif. “A lot of our practices were started without good evidence for why they should be done,” he said. Other steps include value improvement research; use of dashboards and benchmarking; involving other stakeholders including patients, families, and other health care providers; and addressing racial disparities, he concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.

“Health care spending and health care waste is a huge problem in the U.S., including for children,” Vivian Lee, MD, of Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles, said in a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference.

Data from a 2019 study suggested that approximately 25% of health care spending in the United States qualifies as “wasteful spending,” in categories such as overtesting, and unnecessary hospitalization, Dr. Lee said. “It is essential for physicians in hospitals to be stewards of high-value care,” she emphasized.

To combat wasteful spending and control health care costs, the Choosing Wisely campaign was created in 2012 as an initiative from the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. An ongoing goal of the campaign is to raise awareness among physicians and patients about potential areas of low-value services and overuse. The overall campaign includes clinician-driven recommendations from multiple medical organizations.

The PHM produced its first set of five recommendations in 2012, Dr. Lee said. These recommendations, titled “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question,” have been updated for 2021. The updated recommendations were created as a partnership among the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine. A joint committee reviewed the latest evidence, and the updates were approved by the societies and published by the ABIM in January 2021.

“We think these recommendations truly reflect an exciting and evolving landscape for pediatric hospitalists,” Dr. Lee said. “There is a greater focus on opportunities to transition out of the hospital sooner, or avoid hospitalization altogether. There is an emphasis on antibiotic stewardship and a growing recognition of the impact that overuse may have on our vulnerable neonatal population,” she said. Several members of the Choosing Wisely panel presented the recommendations during the virtual presentation.

Revised recommendations

The new “Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question” are as follows:

1. Do not prescribe IV antibiotics for predetermined durations for patients hospitalized with infections such as pyelonephritis, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia. Consider early transition to oral antibiotics.

Many antibiotic doses used in clinical practice are preset durations that are not based on high-quality evidence, said Mike Tchou, MD, of Children’s Hospital of Colorado in Aurora. However, studies now show that earlier transition to enteral antibiotics can improve a range of outcomes including neonatal UTIs, osteomyelitis, and complicated pneumonia, he said. Considering early transition based on a patient’s response can decrease adverse events, pain, length of stay, and health care costs, he explained.

2. Do not continue hospitalization in well-appearing febrile infants once bacterial cultures (i.e., blood, cerebrospinal, and/or urine) have been confirmed negative for 24-36 hours, if adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured.

Recent data indicate that continuing hospitalization beyond 24-36 hours of confirmed negative bacterial cultures does not improve clinical outcomes for well-appearing infants admitted for concern of serious bacterial infection, said Paula Soung, MD, of Children’s Wisconsin in Milwaukee. In fact, “blood culture yield is highest in the first 12-36 hours after incubation with multiple studies demonstrating > 90% of pathogen cultures being positive by 24 hours,” Dr. Soung said. “If adequate outpatient follow-up can be assured, discharging well-appearing febrile infants at 24-36 hours after confirming cultures are negative has many positive outcomes,” she said.

3. Do not initiate phototherapy in term or late preterm well-appearing infants with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia if their bilirubin is below levels at which the AAP guidelines recommend treatment.

In making this recommendation, “we considered that the risk of kernicterus and cerebral palsy is extremely low in otherwise healthy term and late preterm newborns,” said Allison Holmes, MD, of Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Manchester, N.H. “Subthreshold phototherapy leads to unnecessary hospitalization and its associated costs and harms,” and data show that kernicterus generally occurs close to 40 mg/dL and occurs most often in infants with hemolysis, she added.

The evidence for the recommendations included data showing that, among other factors, 8.6 of 100,000 babies have a bilirubin greater than 30 mg/dL, said Dr. Holmes. Risks of using subthreshold phototherapy include increased length of stay, increased readmissions, and increased costs, as well as decreased breastfeeding, bonding with parents, and increased parental anxiety. “Adding prolonged hospitalization for an intervention that might not be necessary can be stressful for parents,” she said.

4. Do not use broad-spectrum antibiotics such as ceftriaxone for children hospitalized with uncomplicated community-acquired pneumonia. Use narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin, ampicillin, or amoxicillin.

Michelle Lossius, MD, of the Shands Hospital for Children at the University of Florida, Gainesville, noted that the recommendations reflect IDSA guidelines from 2011 advising the use of ampicillin or penicillin for this population of children. More recent studies with large populations support the ability of narrow-spectrum antibiotics to limit the development of resistant organisms while achieving the same or better outcomes for children hospitalized with CAP, she said.

5. Do not start IV antibiotic therapy on well-appearing newborn infants with isolated risk factors for sepsis such as maternal chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, or untreated group-B streptococcal colonization. Use clinical tools such as an evidence-based sepsis risk calculator to guide management.

“This recommendation combines other recommendations,” said Prabi Rajbhandari, MD, of Akron (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. The evidence is ample, as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends the use of sepsis calculators to guide clinical management in sepsis patients, she said.

Data comparing periods before and after the adoption of a sepsis risk calculator showed a significant reduction in the use of blood cultures and antibiotics, she noted. Other risks of jumping to IV antibiotics include increased hospital stay, increased parental anxiety, and decreased parental bonding, Dr. Rajbhandari added.

Next steps include how to prioritize implementation, as well as deimplementation of outdated practices, said Francisco Alvarez, MD, of Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital, Palo Alto, Calif. “A lot of our practices were started without good evidence for why they should be done,” he said. Other steps include value improvement research; use of dashboards and benchmarking; involving other stakeholders including patients, families, and other health care providers; and addressing racial disparities, he concluded.

The presenters had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Academic Pediatric Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Society of Hospital Medicine.

FROM PHM 2021

United States reaches 5 million cases of child COVID

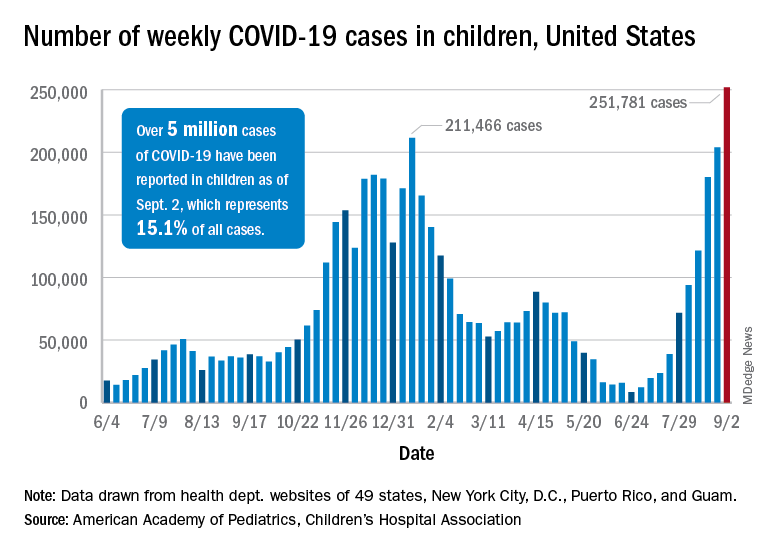

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

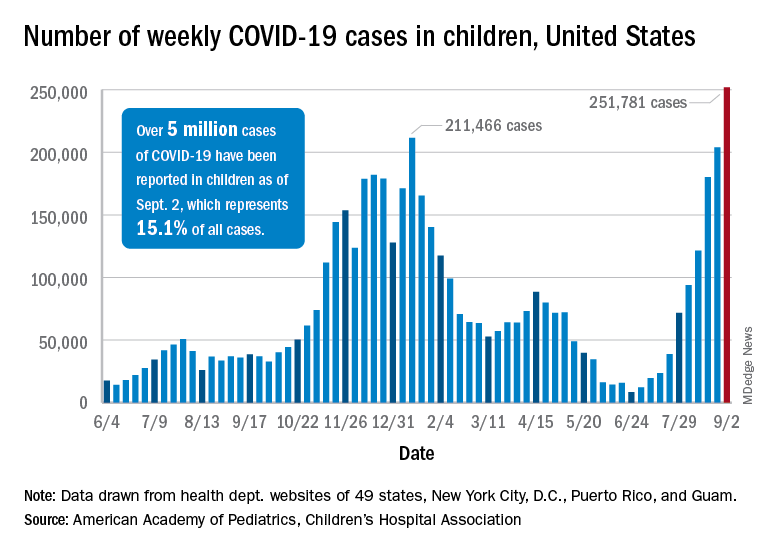

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

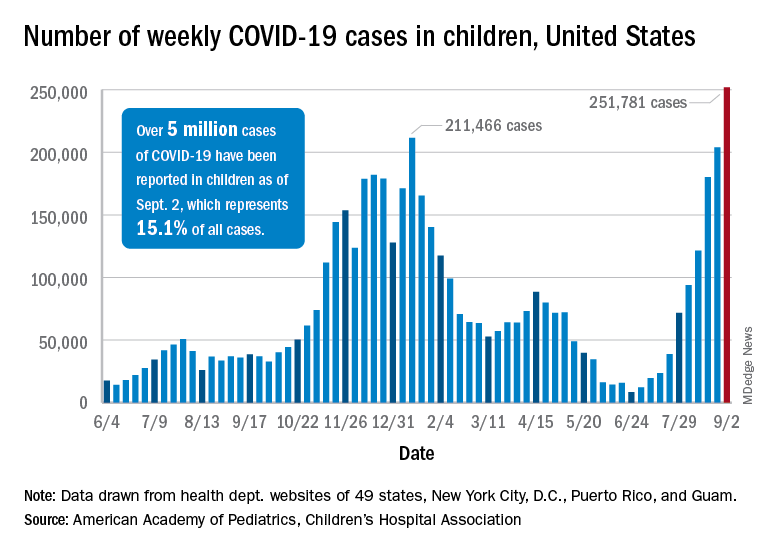

Cases of child COVID-19 set a new 1-week record and the total number of children infected during the pandemic passed 5 million, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The nearly 282,000 new cases reported in the United States during the week ending Sept. 2 broke the record of 211,000 set in mid-January and brought the cumulative count to 5,049,465 children with COVID-19 since the pandemic began, the AAP and the CHA said in their weekly COVID report.

Hospitalizations in children aged 0-17 years have also reached record levels in recent days. The highest daily admission rate since the pandemic began, 0.51 per 100,000 population, was recorded on Sept. 2, less than 2 months after the nation saw its lowest child COVID admission rate for 1 day: 0.07 per 100,000 on July 4. That’s an increase of 629%, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccinations in children, however, did not follow suit. New vaccinations in children aged 12-17 years dropped by 4.5% for the week ending Sept. 6, compared with the week before. Initiations were actually up almost 12% for children aged 16-17, but that was not enough to overcome the continued decline among 12- to 15-year-olds, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker.

Despite the decline in new vaccinations, those younger children passed a noteworthy group milestone: 50.9% of all 12- to 15-year-olds now have received at least one dose, with 38.6% having completed the regimen. The 16- to 17-year-olds got an earlier start and have reached 58.9% coverage for one dose and 47.6% for two, the CDC said.

A total of 12.2 million children aged 12-17 years had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of Sept. 6, of whom almost 9.5 million are fully vaccinated, based on the CDC data.

At the state level, Vermont has the highest rates for vaccine initiation (75%) and full vaccination (65%), with Massachusetts (75%/62%) and Connecticut (73%/59%) just behind. The other end of the scale is occupied by Wyoming (28% initiation/19% full vaccination), Alabama (32%/19%), and North Dakota (32%/23%), the AAP said in a separate report.

In a recent letter to the Food and Drug Administration, AAP President Lee Savio Beers, MD, said that the “Delta variant is surging at extremely alarming rates in every region of America. This surge is seriously impacting all populations, including children.” Dr. Beers urged the FDA to work “aggressively toward authorizing safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines for children under age 12 as soon as possible.”

COVID-19 continues to complicate children’s mental health care

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact child and adolescent mental health, and clinicians are learning as they go to develop strategies that address the challenges of providing both medical and mental health care to young patients, including those who test positive for COVID-19, according to Hani Talebi, PhD, director of pediatric psychology, and Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, director of pediatric hospital medicine, both of the University of Texas at Austin and Dell Children’s Medical Center.

In a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem shared their experiences in identifying the impact of the pandemic on mental health services in a freestanding hospital, and synthesizing inpatient mental health care and medical care outside of a dedicated mental health unit.

Mental health is a significant pediatric issue; approximately one in five children have a diagnosable mental or behavioral health problem, but nearly two-thirds get little or no help, Dr. Talebi said. “COVID-19 has only exacerbated these mental health challenges,” he said.

He noted that beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health-related emergency department visits increased and remained elevated through the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, as families fearful of COVID-19 avoided regular hospital visits.

Data suggest that up to 50% of all adolescent psychiatric crises that led to inpatient admissions were related in some way to COVID-19, Dr. Talebi said. In addition, “individuals with a recent diagnosis of a mental health disorder are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection,” and the risk is even higher among women and African Americans, he said.

The past year significantly impacted the mental wellbeing of parents and children, Dr. Talebi said. He cited a June 2020 study in Pediatrics in which 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children. Ongoing issues including food insecurity, loss of regular child care, and an overall “very disorienting experience in the day-to-day” compromised the mental health of families, Dr. Talebi emphasized. Children isolated at home were not meeting developmental milestones that organically occur when socializing with peers, parents didn’t know how to handle some of their children’s issues without support from schools, and many people were struggling with other preexisting health conditions, he said.

This confluence of factors helped drive a surge in emergency department visits, meaning longer wait times and concerns about meeting urgent medical and mental health needs while maintaining safety, he added.

Parents and children waited longer to seek care, and community hospitals such as Dell Children’s Medical Center were faced with children in the emergency department with crisis-level mental health issues, along with children already waiting in the ED to address medical emergencies. All these patients had to be tested for COVID-19 and managed accordingly, Dr. Talebi noted.

Dr. Talebi emphasized the need for clinically robust care of the children who were in isolation for 10 days on the medical unit, waiting to test negative. New protocols were created for social workers to conduct daily safety checks, and to develop regular schedules for screening, “so they are having an experience on the medical floors similar to what they would have in a mental health unit,” he said.

Dr. Ganem reflected on the logistical challenges of managing mental health care while observing COVID-19 safety protocols. “COVID-19 added a new wrinkle of isolation,” he said. As institutional guidelines on testing and isolation evolved, negative COVID-19 tests were required for admission to the mental health units both in the hospital and throughout the region. Patients who tested positive had to be quarantined for 10 days, at which time they could be admitted to a mental health unit if necessary, he said.

Dr. Ganem shared details of some strategies adopted by Dell Children’s. He explained that the COVID-19 psychiatry patient workflow started with an ED evaluation, followed by medical clearance and consideration for admission.

“There was significant coordination between the social worker in the emergency department and the psychiatry social worker,” he said.

Key elements of the treatment plan for children with positive COVID-19 tests included an “interprofessional huddle” to coordinate the plan of care, goals for admission, and goals for safety, Dr. Ganem said.

Patients who required admission were expected to have an initial length of stay of 72 hours, and those who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted to a medical unit with COVID-19 isolation, he said.

Once a patient is admitted, an RN activates a suicide prevention pathway, and an interprofessional team meets to determine what patients need for safe and effective discharge, said Dr. Ganem. He cited the SAFE-T protocol (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) as one of the tools used to determine safe discharge criteria. Considerations on the SAFE-T list include family support, an established outpatient therapist and psychiatrist, no suicide attempts prior to the current admission, or a low lethality attempt, and access to partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs.

Patients who could not be discharged because of suicidality or inadequate support or concerns about safety at home were considered for inpatient admission. Patients with COVID-19–positive tests who had continued need for inpatient mental health services could be transferred to an inpatient mental health unit after a 10-day quarantine.

Overall, “this has been a continuum of lessons learned, with some things we know now that we didn’t know in April or May of 2020,” Dr. Ganem said. Early in the pandemic, the focus was on minimizing risk, securing personal protective equipment, and determining who provided services in a patient’s room. “We developed new paradigms on the fly,” he said, including the use of virtual visits, which included securing and cleaning devices, as well as learning how to use them in this setting,” he said.

More recently, the emphasis has been on providing services to patients before they need to visit the hospital, rather than automatically admitting any patients with suicidal ideation and a positive COVID-19 test, Dr. Ganem said.

Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem had no financial conflicts to disclose. The conference was sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to impact child and adolescent mental health, and clinicians are learning as they go to develop strategies that address the challenges of providing both medical and mental health care to young patients, including those who test positive for COVID-19, according to Hani Talebi, PhD, director of pediatric psychology, and Jorge Ganem, MD, FAAP, director of pediatric hospital medicine, both of the University of Texas at Austin and Dell Children’s Medical Center.

In a presentation at the 2021 virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine conference, Dr. Talebi and Dr. Ganem shared their experiences in identifying the impact of the pandemic on mental health services in a freestanding hospital, and synthesizing inpatient mental health care and medical care outside of a dedicated mental health unit.

Mental health is a significant pediatric issue; approximately one in five children have a diagnosable mental or behavioral health problem, but nearly two-thirds get little or no help, Dr. Talebi said. “COVID-19 has only exacerbated these mental health challenges,” he said.

He noted that beginning in April 2020, the proportion of children’s mental health-related emergency department visits increased and remained elevated through the spring, summer, and fall of 2020, as families fearful of COVID-19 avoided regular hospital visits.

Data suggest that up to 50% of all adolescent psychiatric crises that led to inpatient admissions were related in some way to COVID-19, Dr. Talebi said. In addition, “individuals with a recent diagnosis of a mental health disorder are at increased risk for COVID-19 infection,” and the risk is even higher among women and African Americans, he said.

The past year significantly impacted the mental wellbeing of parents and children, Dr. Talebi said. He cited a June 2020 study in Pediatrics in which 27% of parents reported worsening mental health for themselves, and 14% reported worsening behavioral health for their children. Ongoing issues including food insecurity, loss of regular child care, and an overall “very disorienting experience in the day-to-day” compromised the mental health of families, Dr. Talebi emphasized. Children isolated at home were not meeting developmental milestones that organically occur when socializing with peers, parents didn’t know how to handle some of their children’s issues without support from schools, and many people were struggling with other preexisting health conditions, he said.

This confluence of factors helped drive a surge in emergency department visits, meaning longer wait times and concerns about meeting urgent medical and mental health needs while maintaining safety, he added.

Parents and children waited longer to seek care, and community hospitals such as Dell Children’s Medical Center were faced with children in the emergency department with crisis-level mental health issues, along with children already waiting in the ED to address medical emergencies. All these patients had to be tested for COVID-19 and managed accordingly, Dr. Talebi noted.

Dr. Talebi emphasized the need for clinically robust care of the children who were in isolation for 10 days on the medical unit, waiting to test negative. New protocols were created for social workers to conduct daily safety checks, and to develop regular schedules for screening, “so they are having an experience on the medical floors similar to what they would have in a mental health unit,” he said.

Dr. Ganem reflected on the logistical challenges of managing mental health care while observing COVID-19 safety protocols. “COVID-19 added a new wrinkle of isolation,” he said. As institutional guidelines on testing and isolation evolved, negative COVID-19 tests were required for admission to the mental health units both in the hospital and throughout the region. Patients who tested positive had to be quarantined for 10 days, at which time they could be admitted to a mental health unit if necessary, he said.

Dr. Ganem shared details of some strategies adopted by Dell Children’s. He explained that the COVID-19 psychiatry patient workflow started with an ED evaluation, followed by medical clearance and consideration for admission.

“There was significant coordination between the social worker in the emergency department and the psychiatry social worker,” he said.

Key elements of the treatment plan for children with positive COVID-19 tests included an “interprofessional huddle” to coordinate the plan of care, goals for admission, and goals for safety, Dr. Ganem said.

Patients who required admission were expected to have an initial length of stay of 72 hours, and those who tested positive for COVID-19 were admitted to a medical unit with COVID-19 isolation, he said.

Once a patient is admitted, an RN activates a suicide prevention pathway, and an interprofessional team meets to determine what patients need for safe and effective discharge, said Dr. Ganem. He cited the SAFE-T protocol (Suicide Assessment Five-step Evaluation and Triage) as one of the tools used to determine safe discharge criteria. Considerations on the SAFE-T list include family support, an established outpatient therapist and psychiatrist, no suicide attempts prior to the current admission, or a low lethality attempt, and access to partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient programs.

Patients who could not be discharged because of suicidality or inadequate support or concerns about safety at home were considered for inpatient admission. Patients with COVID-19–positive tests who had continued need for inpatient mental health services could be transferred to an inpatient mental health unit after a 10-day quarantine.