User login

ICU admissions raise chronic condition risk

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

SAN DIEGO – The research showed rising likelihood of conditions such as depression, diabetes, and heart disease.

By merging two existing databases, the researchers were able to capture a more comprehensive picture of post-ICU patients. “We were able to include almost the entire country,” Ilse van Beusekom, a PhD candidate in health sciences at the University of Amsterdam and data manager at the National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) foundation, said in an interview.

Ms. van Beusekom presented the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. The study was simultaneously published in Critical Care Medicine.

The work compared 56,760 ICU survivors from 81 facilities across the Netherlands to 75,232 age-, sex-, and socioeconomic status–matched controls. The mean age was 65 years and 60% of the population was male. “The types of chronic conditions are the same, only the prevalences are different,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

The researchers compared chronic conditions in the year before ICU admission and the year after, based on data pulled from the NICE national quality database, which includes data describing the first 24 hours of ICU admission, and the Vektis insurance claims database, which includes information on medical treatment. Before ICU admission, 45% of the ICU population was free of chronic conditions, as were 62% of controls. One chronic condition was present in 36% of ICU patients, versus 29% of controls, and two or more conditions were present in 19% versus 9% of controls.

The ICU population was more likely to have high cholesterol (16% vs. 14%), heart disease (14% vs. 6%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8% vs. 3%), type II diabetes (8% vs. 6%), type I diabetes (6% vs. 3%), and depression (6% vs. 4%).

The ICU population also was at greater risk of developing one or more new chronic conditions during the year following their stay. The risk was three- to fourfold higher throughout age ranges.

The study suggests the need for greater follow-up after an ICU admission in order to help patients cope with lingering problems. Ms. van Beusekom noted that there are follow-up programs in the Netherlands for several patient groups, but none for ICU survivors. One possibility would be to have the patient return to the ICU 3 months or so after release to discuss their diagnosis, treatment, and any lingering concerns. “A lot of people don’t know that their complaints are linked with the ICU visit,” said Ms. van Beusekom.

Timothy G. Buchman, MD, professor of surgery at Emory University, Atlanta, who moderated the session, wondered why the ICU seems to be an inflection point for developing new chronic conditions. Could it simply be because patients are sicker to begin with and have reached an inflection point of their illness, or could the treatments in ICU be contributing to or exposing those conditions? Ms. van Beusekom believed it was likely a combination of factors, and she referred to data she had not presented showing that even control patients who had been to the hospital (though not the ICU) during the study period were at lower risk of new chronic conditions than ICU patients.

Ms. van Beusekom’s group plans to investigate ICU-related variables that might be associated with risk of chronic conditions.

The study was not funded. Ms. van Beusekom had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: van Beusekom I et al. CCC48, Abstract Crit Care Med. 2019;47:324-30.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Helping quality improvement teams succeed

QI coaches may be the answer

Hospitalists understand the need for quality improvement (QI) as an important part of health care, and they take active roles in – or personally drive – many of the QI efforts at their own facilities. But too often the results are inconsistent and the adoption of new practices slow.

Help can come from a QI Coach, according to a recent paper describing a model of successful coaching. “We wanted to be able to help novice QI teams to be successful,” said the paper’s lead author Danielle Olds, PhD. “Unfortunately, most QI projects are not successful for a variety of reasons including inadequate project planning, a lack of QI skills, a lack of leadership and stakeholder buy-in, and inappropriate measures and methods.”

The coaching model outlined comes from the VAQS program, launched in 1998 to provide structured training around QI and the care of veterans. The seven-step process outlined in the paper provides a road map to overcoming typical QI stumbling blocks and create more successful projects.

“Improvement should be a part of everyone’s practice, however most clinicians have not been trained in how to successfully lead a formal QI project,” said Dr. Olds, who is based at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. “Hospitals can bridge this gap by providing QI coaches as a resource to guide teams through the process.”

The model offers a new way for hospitalists to take the lead on QI. “Hospitalists who may have extensive experience in conducting QI could use a model, such as ours, to guide their coaching of teams within their facility,” she said. “Because of the nature of hospitalist practice, they are in an ideal position to understand improvement needs at a systems level within their facility. I would strongly encourage hospitalists to engage in QI because of the wealth of knowledge and experience that they could bring.”

Reference

Olds DM et al. “VA Quality Scholars Quality Improvement Coach Model to Facilitate Learning and Success.” Qual Manag Healthcare. 2018;27(2):87-92. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000164. Accessed 2018 Jun 11.

QI coaches may be the answer

QI coaches may be the answer

Hospitalists understand the need for quality improvement (QI) as an important part of health care, and they take active roles in – or personally drive – many of the QI efforts at their own facilities. But too often the results are inconsistent and the adoption of new practices slow.

Help can come from a QI Coach, according to a recent paper describing a model of successful coaching. “We wanted to be able to help novice QI teams to be successful,” said the paper’s lead author Danielle Olds, PhD. “Unfortunately, most QI projects are not successful for a variety of reasons including inadequate project planning, a lack of QI skills, a lack of leadership and stakeholder buy-in, and inappropriate measures and methods.”

The coaching model outlined comes from the VAQS program, launched in 1998 to provide structured training around QI and the care of veterans. The seven-step process outlined in the paper provides a road map to overcoming typical QI stumbling blocks and create more successful projects.

“Improvement should be a part of everyone’s practice, however most clinicians have not been trained in how to successfully lead a formal QI project,” said Dr. Olds, who is based at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. “Hospitals can bridge this gap by providing QI coaches as a resource to guide teams through the process.”

The model offers a new way for hospitalists to take the lead on QI. “Hospitalists who may have extensive experience in conducting QI could use a model, such as ours, to guide their coaching of teams within their facility,” she said. “Because of the nature of hospitalist practice, they are in an ideal position to understand improvement needs at a systems level within their facility. I would strongly encourage hospitalists to engage in QI because of the wealth of knowledge and experience that they could bring.”

Reference

Olds DM et al. “VA Quality Scholars Quality Improvement Coach Model to Facilitate Learning and Success.” Qual Manag Healthcare. 2018;27(2):87-92. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000164. Accessed 2018 Jun 11.

Hospitalists understand the need for quality improvement (QI) as an important part of health care, and they take active roles in – or personally drive – many of the QI efforts at their own facilities. But too often the results are inconsistent and the adoption of new practices slow.

Help can come from a QI Coach, according to a recent paper describing a model of successful coaching. “We wanted to be able to help novice QI teams to be successful,” said the paper’s lead author Danielle Olds, PhD. “Unfortunately, most QI projects are not successful for a variety of reasons including inadequate project planning, a lack of QI skills, a lack of leadership and stakeholder buy-in, and inappropriate measures and methods.”

The coaching model outlined comes from the VAQS program, launched in 1998 to provide structured training around QI and the care of veterans. The seven-step process outlined in the paper provides a road map to overcoming typical QI stumbling blocks and create more successful projects.

“Improvement should be a part of everyone’s practice, however most clinicians have not been trained in how to successfully lead a formal QI project,” said Dr. Olds, who is based at the University of Kansas Medical Center in Kansas City. “Hospitals can bridge this gap by providing QI coaches as a resource to guide teams through the process.”

The model offers a new way for hospitalists to take the lead on QI. “Hospitalists who may have extensive experience in conducting QI could use a model, such as ours, to guide their coaching of teams within their facility,” she said. “Because of the nature of hospitalist practice, they are in an ideal position to understand improvement needs at a systems level within their facility. I would strongly encourage hospitalists to engage in QI because of the wealth of knowledge and experience that they could bring.”

Reference

Olds DM et al. “VA Quality Scholars Quality Improvement Coach Model to Facilitate Learning and Success.” Qual Manag Healthcare. 2018;27(2):87-92. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000164. Accessed 2018 Jun 11.

Opportunities missed for advance care planning for elderly ICU patients

SAN DIEGO – A nationally representative survey of the problem is more pronounced among some blacks and Hispanics and those with lower net worth. The study also found that these patients see physicians an average of 20 times in the year preceding the ICU visit, which suggests that there are plenty of opportunities to put ACP in place.

“Over two-thirds were seen by a doctor in the last 2 weeks. So they’re seeing doctors, but they’re still not doing advance care planning,” said Brian Block, MD, during a presentation of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Block is with the University of California, San Francisco.

Lack of advance planning can put major road blocks in front of patient care in the ICU, as well as complicate communication between physicians and family members. The findings underscore the need to encourage conversations about end-of-life care between physicians and their patients – before the patients wind up in intensive care.

One audience member believes these conversations are already happening. Paul Yodice, MD, chairman of medicine at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J., suggested that physicians are attempting to engage older patients and family members in ACP, but many are unready to make decisions. “In my experience, it is happening much more frequently than is captured either in the medical record or in the research that we’ve been publishing. I’ve been a part of those conversations. Those individuals who are faced with those toughest of choices choose to delay making the decision or speaking about it further because it’s just too painful to consider, and they hold out hope of being the one to beat the odds, to have one more day,” said Dr. Yodice.

He called for further research to document whether ACP conversations are happening and to identify barriers to decisions and the means to overcome them. “A next good study would be to send out a respectful survey to the families of those who have lost people they love and ask: Has someone in the past year spoken with you or offered to have a discussion about end-of-life issues? We could get a better handle on [how often] the discussion is being had, and then find a solution,” said Dr. Yodice.

ACP can also be difficult for the provider, he added. Family members and patients, desperate for another treatment option, will often ask if there’s anything else that can be done. “In medicine, the answer almost always is ‘Well, we can try something else even though I know it’s not going to work.’ And people hold on to that, including us,” said Dr. Yodice.

The study analyzed data from a Medicare cohort of 1,109 patients who died during 2000-2013 and had an ICU admission within the last 30 days of their life. Ages were fairly evenly distributed, with 29% aged 65-74 years, 39% aged 75-84, and 32% aged 85 and over. Fifty-four percent were women, 26% were nonwhite, 42% had not completed high school, and 11% were in skilled nursing facilities.

About 35% had no ACP in 2000-2001, and that percentage gradually declined, to about 20% in 2012-2013 (slope, –1.6%/year; P = .009).

Seventeen percent of white participants had no ACP, compared with 51% of blacks and 49% of Hispanics. Net worth was also strongly associated with having ACP: The top quartile had 13% lacking ACP, compared with 43% of the bottom quartile.

The study found that 94% of patients who had no ACP had visited a health care provider in the past year. The average number of visits in the past year was 20, and 83% had seen a provider within the past 30 days.

Dr. Block did not declare a source of funding or potential conflicts. Dr. Yodice had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Block B et al. CCC48, Abstract 401.

SAN DIEGO – A nationally representative survey of the problem is more pronounced among some blacks and Hispanics and those with lower net worth. The study also found that these patients see physicians an average of 20 times in the year preceding the ICU visit, which suggests that there are plenty of opportunities to put ACP in place.

“Over two-thirds were seen by a doctor in the last 2 weeks. So they’re seeing doctors, but they’re still not doing advance care planning,” said Brian Block, MD, during a presentation of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Block is with the University of California, San Francisco.

Lack of advance planning can put major road blocks in front of patient care in the ICU, as well as complicate communication between physicians and family members. The findings underscore the need to encourage conversations about end-of-life care between physicians and their patients – before the patients wind up in intensive care.

One audience member believes these conversations are already happening. Paul Yodice, MD, chairman of medicine at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J., suggested that physicians are attempting to engage older patients and family members in ACP, but many are unready to make decisions. “In my experience, it is happening much more frequently than is captured either in the medical record or in the research that we’ve been publishing. I’ve been a part of those conversations. Those individuals who are faced with those toughest of choices choose to delay making the decision or speaking about it further because it’s just too painful to consider, and they hold out hope of being the one to beat the odds, to have one more day,” said Dr. Yodice.

He called for further research to document whether ACP conversations are happening and to identify barriers to decisions and the means to overcome them. “A next good study would be to send out a respectful survey to the families of those who have lost people they love and ask: Has someone in the past year spoken with you or offered to have a discussion about end-of-life issues? We could get a better handle on [how often] the discussion is being had, and then find a solution,” said Dr. Yodice.

ACP can also be difficult for the provider, he added. Family members and patients, desperate for another treatment option, will often ask if there’s anything else that can be done. “In medicine, the answer almost always is ‘Well, we can try something else even though I know it’s not going to work.’ And people hold on to that, including us,” said Dr. Yodice.

The study analyzed data from a Medicare cohort of 1,109 patients who died during 2000-2013 and had an ICU admission within the last 30 days of their life. Ages were fairly evenly distributed, with 29% aged 65-74 years, 39% aged 75-84, and 32% aged 85 and over. Fifty-four percent were women, 26% were nonwhite, 42% had not completed high school, and 11% were in skilled nursing facilities.

About 35% had no ACP in 2000-2001, and that percentage gradually declined, to about 20% in 2012-2013 (slope, –1.6%/year; P = .009).

Seventeen percent of white participants had no ACP, compared with 51% of blacks and 49% of Hispanics. Net worth was also strongly associated with having ACP: The top quartile had 13% lacking ACP, compared with 43% of the bottom quartile.

The study found that 94% of patients who had no ACP had visited a health care provider in the past year. The average number of visits in the past year was 20, and 83% had seen a provider within the past 30 days.

Dr. Block did not declare a source of funding or potential conflicts. Dr. Yodice had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Block B et al. CCC48, Abstract 401.

SAN DIEGO – A nationally representative survey of the problem is more pronounced among some blacks and Hispanics and those with lower net worth. The study also found that these patients see physicians an average of 20 times in the year preceding the ICU visit, which suggests that there are plenty of opportunities to put ACP in place.

“Over two-thirds were seen by a doctor in the last 2 weeks. So they’re seeing doctors, but they’re still not doing advance care planning,” said Brian Block, MD, during a presentation of the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Block is with the University of California, San Francisco.

Lack of advance planning can put major road blocks in front of patient care in the ICU, as well as complicate communication between physicians and family members. The findings underscore the need to encourage conversations about end-of-life care between physicians and their patients – before the patients wind up in intensive care.

One audience member believes these conversations are already happening. Paul Yodice, MD, chairman of medicine at Saint Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, N.J., suggested that physicians are attempting to engage older patients and family members in ACP, but many are unready to make decisions. “In my experience, it is happening much more frequently than is captured either in the medical record or in the research that we’ve been publishing. I’ve been a part of those conversations. Those individuals who are faced with those toughest of choices choose to delay making the decision or speaking about it further because it’s just too painful to consider, and they hold out hope of being the one to beat the odds, to have one more day,” said Dr. Yodice.

He called for further research to document whether ACP conversations are happening and to identify barriers to decisions and the means to overcome them. “A next good study would be to send out a respectful survey to the families of those who have lost people they love and ask: Has someone in the past year spoken with you or offered to have a discussion about end-of-life issues? We could get a better handle on [how often] the discussion is being had, and then find a solution,” said Dr. Yodice.

ACP can also be difficult for the provider, he added. Family members and patients, desperate for another treatment option, will often ask if there’s anything else that can be done. “In medicine, the answer almost always is ‘Well, we can try something else even though I know it’s not going to work.’ And people hold on to that, including us,” said Dr. Yodice.

The study analyzed data from a Medicare cohort of 1,109 patients who died during 2000-2013 and had an ICU admission within the last 30 days of their life. Ages were fairly evenly distributed, with 29% aged 65-74 years, 39% aged 75-84, and 32% aged 85 and over. Fifty-four percent were women, 26% were nonwhite, 42% had not completed high school, and 11% were in skilled nursing facilities.

About 35% had no ACP in 2000-2001, and that percentage gradually declined, to about 20% in 2012-2013 (slope, –1.6%/year; P = .009).

Seventeen percent of white participants had no ACP, compared with 51% of blacks and 49% of Hispanics. Net worth was also strongly associated with having ACP: The top quartile had 13% lacking ACP, compared with 43% of the bottom quartile.

The study found that 94% of patients who had no ACP had visited a health care provider in the past year. The average number of visits in the past year was 20, and 83% had seen a provider within the past 30 days.

Dr. Block did not declare a source of funding or potential conflicts. Dr. Yodice had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Block B et al. CCC48, Abstract 401.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

The ever-evolving scope of hospitalists’ clinical services

More care ‘beyond the walls’ of the hospital

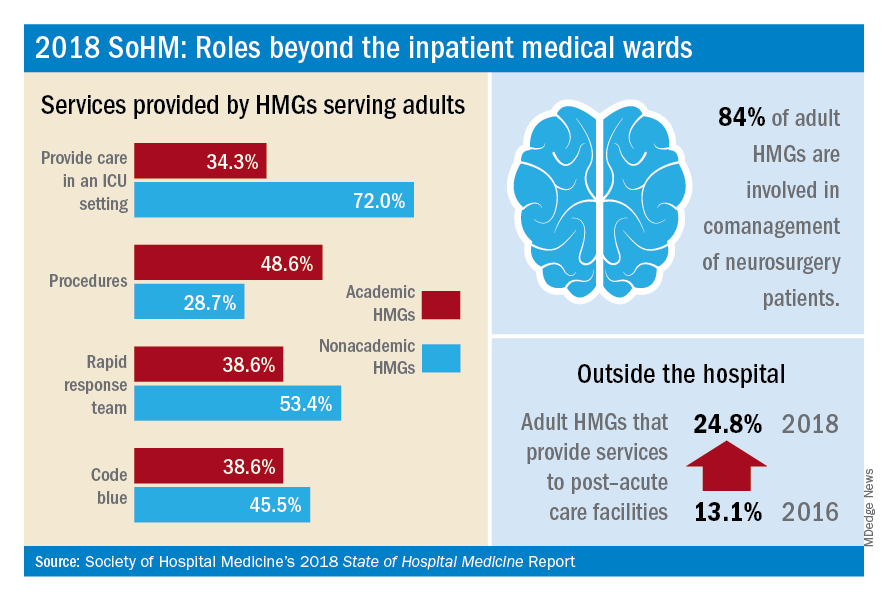

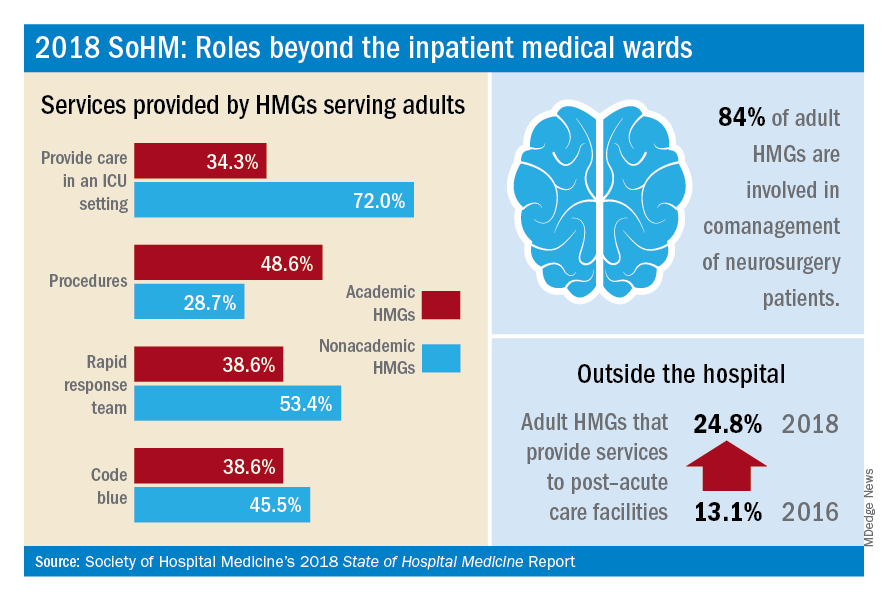

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report provides indispensable data about the scope of clinical services routinely provided by adult and pediatric hospitalists. This year’s SoHM report reveals that a growing number of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) serving adults are involved in roles beyond the inpatient medical wards, including various surgical comanagement programs, outpatient care, and post-acute care services.

The survey also compares services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs, which remain markedly different in some areas. As the landscape of health care continues to evolve, hospitalists transform their scope of services to meet the needs of the institutions and communities they serve.

In the previous three SoHM reports, it was well established that more than 87% of adult hospital medicine groups play some role in comanaging surgical patients. In this year’s SoHM report, that role was further stratified to capture the various subspecialties represented, and to identify whether the hospitalists generally served as admitting/attending physician or consultant.

Hospitalists’ roles in comanagement are most prominent for care of orthopedic and general surgery patients, but more than 50% of surveyed HMGs reported being involved in comanagement in some capacity with neurosurgery, obstetrics, and cardiovascular surgery. Additionally, almost 95% of surveyed adult HMGs reported that they provided comanagement services for at least one other surgical specialty that was not listed in the survey.

The report also displays comanagement services provided to various medical subspecialties, including neurology, GI/liver, oncology, and more. Of the medical subspecialties represented, adult HMGs comanaged GI/liver (98.2%) and oncology (97.7%) services more often than others.

Interestingly, more HMGs are providing care for patients beyond the walls of the hospital. In the 2018 SoHM report, over 17% of surveyed HMG respondents reported providing care in an outpatient setting, representing an increase of 6.5 percentage points over 2016. Most strikingly, from 2016 to 2018, there was a 12 percentage point increase in adult HMGs reporting services provided to post-acute care facilities (from 13.1% to 24.8%).

These trends were most notable in the Midwest region where nearly 28% of HMGs provide patient care in an outpatient setting and up to 34% in post-acute care facilities. In part, this trend may result from the increased emphasis on improving transitions of care, by providing prehospital preoperative services, postdischarge follow-up encounters, or offering posthospitalization extensivist care.

Within the hospital itself, there remain striking differences in certain services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs serving adults. Nonacademic HMGs are far more likely to cover patients in an ICU than their academic counterparts (72.0% vs. 34.3%). In contrast, academic hospitalist groups were significantly more inclined to perform procedures. However, the report also showed that there was an overall downtrend of percentage of HMGs that cover patients in an ICU or perform procedures.

As the scope of hospitalist services continues to change over time, should there be concern for scope creep? It depends on how one might view the change. As health care becomes ever more complex, high-functioning HMGs are needed to navigate it, both within and beyond the hospital. Some might consider scope evolution to be a reflection of hospitalists being recognized for their ability to provide high-quality, efficient, and comprehensive care. Hospital medicine groups will likely continue to evolve to meet the needs of an ever-changing health care environment.

Dr. Kurian is chief of the academic division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health in New York. She is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

More care ‘beyond the walls’ of the hospital

More care ‘beyond the walls’ of the hospital

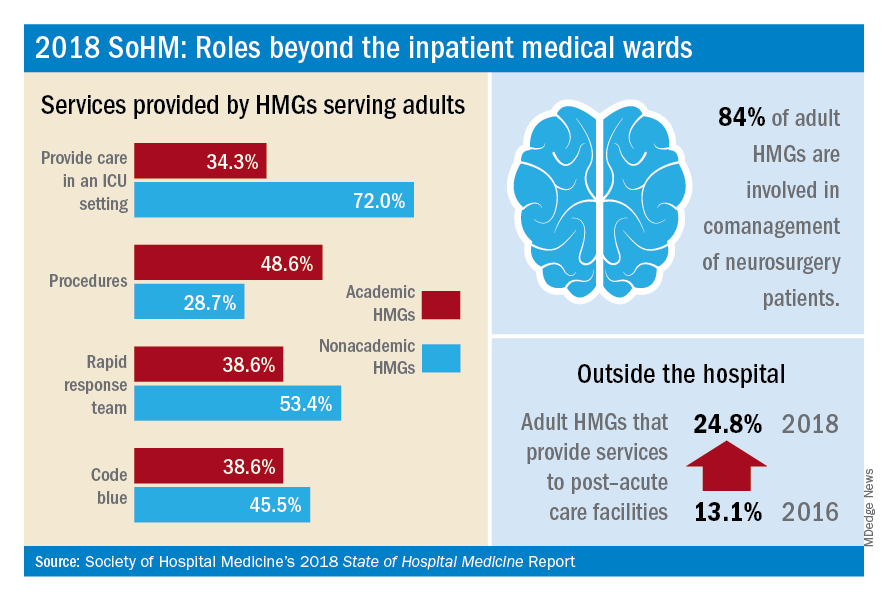

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report provides indispensable data about the scope of clinical services routinely provided by adult and pediatric hospitalists. This year’s SoHM report reveals that a growing number of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) serving adults are involved in roles beyond the inpatient medical wards, including various surgical comanagement programs, outpatient care, and post-acute care services.

The survey also compares services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs, which remain markedly different in some areas. As the landscape of health care continues to evolve, hospitalists transform their scope of services to meet the needs of the institutions and communities they serve.

In the previous three SoHM reports, it was well established that more than 87% of adult hospital medicine groups play some role in comanaging surgical patients. In this year’s SoHM report, that role was further stratified to capture the various subspecialties represented, and to identify whether the hospitalists generally served as admitting/attending physician or consultant.

Hospitalists’ roles in comanagement are most prominent for care of orthopedic and general surgery patients, but more than 50% of surveyed HMGs reported being involved in comanagement in some capacity with neurosurgery, obstetrics, and cardiovascular surgery. Additionally, almost 95% of surveyed adult HMGs reported that they provided comanagement services for at least one other surgical specialty that was not listed in the survey.

The report also displays comanagement services provided to various medical subspecialties, including neurology, GI/liver, oncology, and more. Of the medical subspecialties represented, adult HMGs comanaged GI/liver (98.2%) and oncology (97.7%) services more often than others.

Interestingly, more HMGs are providing care for patients beyond the walls of the hospital. In the 2018 SoHM report, over 17% of surveyed HMG respondents reported providing care in an outpatient setting, representing an increase of 6.5 percentage points over 2016. Most strikingly, from 2016 to 2018, there was a 12 percentage point increase in adult HMGs reporting services provided to post-acute care facilities (from 13.1% to 24.8%).

These trends were most notable in the Midwest region where nearly 28% of HMGs provide patient care in an outpatient setting and up to 34% in post-acute care facilities. In part, this trend may result from the increased emphasis on improving transitions of care, by providing prehospital preoperative services, postdischarge follow-up encounters, or offering posthospitalization extensivist care.

Within the hospital itself, there remain striking differences in certain services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs serving adults. Nonacademic HMGs are far more likely to cover patients in an ICU than their academic counterparts (72.0% vs. 34.3%). In contrast, academic hospitalist groups were significantly more inclined to perform procedures. However, the report also showed that there was an overall downtrend of percentage of HMGs that cover patients in an ICU or perform procedures.

As the scope of hospitalist services continues to change over time, should there be concern for scope creep? It depends on how one might view the change. As health care becomes ever more complex, high-functioning HMGs are needed to navigate it, both within and beyond the hospital. Some might consider scope evolution to be a reflection of hospitalists being recognized for their ability to provide high-quality, efficient, and comprehensive care. Hospital medicine groups will likely continue to evolve to meet the needs of an ever-changing health care environment.

Dr. Kurian is chief of the academic division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health in New York. She is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

The 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report provides indispensable data about the scope of clinical services routinely provided by adult and pediatric hospitalists. This year’s SoHM report reveals that a growing number of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) serving adults are involved in roles beyond the inpatient medical wards, including various surgical comanagement programs, outpatient care, and post-acute care services.

The survey also compares services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs, which remain markedly different in some areas. As the landscape of health care continues to evolve, hospitalists transform their scope of services to meet the needs of the institutions and communities they serve.

In the previous three SoHM reports, it was well established that more than 87% of adult hospital medicine groups play some role in comanaging surgical patients. In this year’s SoHM report, that role was further stratified to capture the various subspecialties represented, and to identify whether the hospitalists generally served as admitting/attending physician or consultant.

Hospitalists’ roles in comanagement are most prominent for care of orthopedic and general surgery patients, but more than 50% of surveyed HMGs reported being involved in comanagement in some capacity with neurosurgery, obstetrics, and cardiovascular surgery. Additionally, almost 95% of surveyed adult HMGs reported that they provided comanagement services for at least one other surgical specialty that was not listed in the survey.

The report also displays comanagement services provided to various medical subspecialties, including neurology, GI/liver, oncology, and more. Of the medical subspecialties represented, adult HMGs comanaged GI/liver (98.2%) and oncology (97.7%) services more often than others.

Interestingly, more HMGs are providing care for patients beyond the walls of the hospital. In the 2018 SoHM report, over 17% of surveyed HMG respondents reported providing care in an outpatient setting, representing an increase of 6.5 percentage points over 2016. Most strikingly, from 2016 to 2018, there was a 12 percentage point increase in adult HMGs reporting services provided to post-acute care facilities (from 13.1% to 24.8%).

These trends were most notable in the Midwest region where nearly 28% of HMGs provide patient care in an outpatient setting and up to 34% in post-acute care facilities. In part, this trend may result from the increased emphasis on improving transitions of care, by providing prehospital preoperative services, postdischarge follow-up encounters, or offering posthospitalization extensivist care.

Within the hospital itself, there remain striking differences in certain services provided by academic and nonacademic HMGs serving adults. Nonacademic HMGs are far more likely to cover patients in an ICU than their academic counterparts (72.0% vs. 34.3%). In contrast, academic hospitalist groups were significantly more inclined to perform procedures. However, the report also showed that there was an overall downtrend of percentage of HMGs that cover patients in an ICU or perform procedures.

As the scope of hospitalist services continues to change over time, should there be concern for scope creep? It depends on how one might view the change. As health care becomes ever more complex, high-functioning HMGs are needed to navigate it, both within and beyond the hospital. Some might consider scope evolution to be a reflection of hospitalists being recognized for their ability to provide high-quality, efficient, and comprehensive care. Hospital medicine groups will likely continue to evolve to meet the needs of an ever-changing health care environment.

Dr. Kurian is chief of the academic division of hospital medicine at Northwell Health in New York. She is a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee.

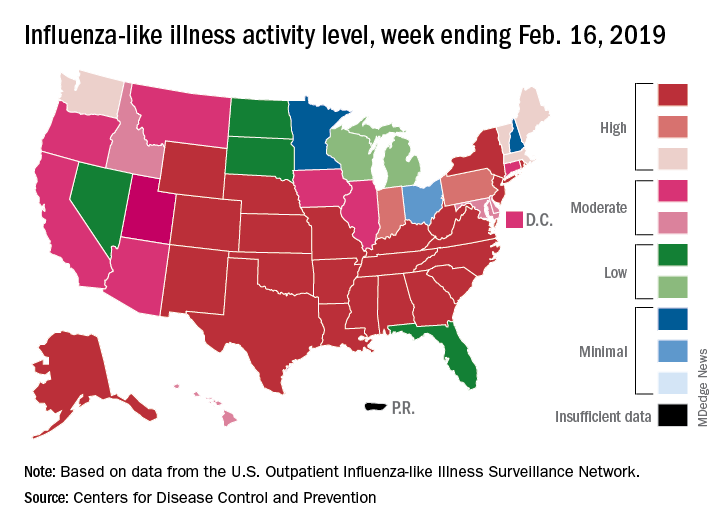

U.S. measles cases up to 159 for the year

Reported measles cases are now up to 159 for the year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent reporting week, which ended Feb. 21, brought another 32 cases of measles and one new outbreak of 4 cases in Illinois. The total number of outbreaks – an outbreak is defined as three or more cases – is now six, and cases have been reported in 10 states, the CDC said Feb. 25.

The majority (17) of those 32 new cases occurred in Brooklyn, one of New York state’s three outbreaks this year. The largest of the 2019 outbreaks is in Washington state, primarily in Clark County, and is up to 66 cases after 4 more were reported in the last week by the state’s department of health. The outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought the disease to the United States.

There are now two measures “advancing through the [Washington] state legislature that would bar parents from using personal or philosophical exemptions to avoid immunizing their school-age children. Both have bipartisan support despite strong antivaccination sentiment in parts of the state,” the Washington Post said on Feb. 25.

Reported measles cases are now up to 159 for the year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent reporting week, which ended Feb. 21, brought another 32 cases of measles and one new outbreak of 4 cases in Illinois. The total number of outbreaks – an outbreak is defined as three or more cases – is now six, and cases have been reported in 10 states, the CDC said Feb. 25.

The majority (17) of those 32 new cases occurred in Brooklyn, one of New York state’s three outbreaks this year. The largest of the 2019 outbreaks is in Washington state, primarily in Clark County, and is up to 66 cases after 4 more were reported in the last week by the state’s department of health. The outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought the disease to the United States.

There are now two measures “advancing through the [Washington] state legislature that would bar parents from using personal or philosophical exemptions to avoid immunizing their school-age children. Both have bipartisan support despite strong antivaccination sentiment in parts of the state,” the Washington Post said on Feb. 25.

Reported measles cases are now up to 159 for the year in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The most recent reporting week, which ended Feb. 21, brought another 32 cases of measles and one new outbreak of 4 cases in Illinois. The total number of outbreaks – an outbreak is defined as three or more cases – is now six, and cases have been reported in 10 states, the CDC said Feb. 25.

The majority (17) of those 32 new cases occurred in Brooklyn, one of New York state’s three outbreaks this year. The largest of the 2019 outbreaks is in Washington state, primarily in Clark County, and is up to 66 cases after 4 more were reported in the last week by the state’s department of health. The outbreaks are linked to travelers who brought the disease to the United States.

There are now two measures “advancing through the [Washington] state legislature that would bar parents from using personal or philosophical exemptions to avoid immunizing their school-age children. Both have bipartisan support despite strong antivaccination sentiment in parts of the state,” the Washington Post said on Feb. 25.

Peripheral perfusion fails septic shock test, but optimism remains

SAN DIEGO – During resuscitation of patients but missed statistical significance.

Although the paper, published online in JAMA, concludes that normalization of capillary refill time cannot be recommended over targeting serum lactate levels, Glenn Hernández, MD, PhD, sounded more optimistic after presenting the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “I think it’s good news to develop techniques that, even though they have this integrated variability, they can provide a signal that is also very close to the [underlying] physiology,” Dr. Hernández, who is a professor of intensive medicine at Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. The Peripheral perfusion was also associated with lower mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score at 72 hours.

The technique involves pressing a glass microscope slide to the ventral surface of the right index finger distal phalanx, increasing pressure and maintaining pressure for 10 seconds. After release, a chronometer assessed return of normal skin color, with refill times over 3 seconds considered abnormal. Clinicians applied the technique every 30 minutes during until normalization (every hour after that), compared with every 2 hours for the lactate arm of the study.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK randomized clinical trial was conducted at 28 hospitals in five countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Uruguay). The trial did not demonstrate superiority of capillary refill, and it was not designed for noninferiority. It nevertheless seems unlikely that assessment of capillary refill is inferior to lactate levels, according an accompanying editorial by JAMA-associated editor Derek Angus, MD, who also is a professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. The simplicity of using a capillary refill could be particularly useful in resource-limited settings, since it can be accomplished visually.

It also a natural marker for resuscitation. The body slows fluid flow to peripheral tissues until vital organs are well perfused. Normal capillary refill time “is an indirect signal of reperfusion,” said Dr. Hernández.

The researchers are not calling for this technique to replace lactate measurements, noting that in many ways the techniques can be complementary, since lactate levels are a good indicator of the patient’s overall improvement. In any case, it would take more research to prove superiority of the capillary refill, and that’s not something Dr. Hernández is planning to undertake. The current study had no external funding and required about half of his time over a 2-year period. Getting the work done at all “was sort of a miracle. We would not repeat this,” he said.

The researchers randomized 416 patients with septic shock (mean age, 63 years; 53% of whom were women) to be managed by peripheral perfusion or lactate measurement. By day 28, 43.4% in the lactate group had died, compared with 34.9% in the peripheral perfusion group (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .06). At 72 hours, the peripheral perfusion group had less organ dysfunction as measured by SOFA (mean, 5.6 vs. 6.6; P = .045). Six other secondary outcomes revealed no between-group differences.

The peripheral perfusion group received an average of 408 fewer mL of resuscitation fluids during the first 8 hours (P = .01).

That result fits with the greater responsiveness of peripheral perfusion measurements, and it’s relevant because some septic shock patients who are unresponsive to fluids often receive fluids anyway. “The general knowledge, though not correct, is that you treat lactate or blood pressure with fluids,” said coauthor Jan Bakker, MD, PhD, who is a professor at New York-Presbyterian Hospital Columbia University, and Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

After a series of observational studies suggested that warm, well-perfused patients were doing well, the idea was tested in a small interventional trial in which physicians were forbidden from giving fluids once patients were warm and well perfused. Patients did better than did those on standard of care. “We have said, if the patient is warm and well perfused, even if they are hypotensive, don’t give fluids, it won’t benefit them anymore. Give vasopressors or whatever, but don’t give fluids,” said Dr. Bakker.

The latest research also reinforced a signal from the earlier, smaller trial. “You get less organ failure if you use [fewer] fluids,” Dr. Bakker added.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hernández and Dr. Bakker had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Angus received consulting fees from Ferring Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer AG, and others outside the submitted work; he also has patents pending for compounds, compositions, and methods for treating sepsis and for proteomic biomarkers.

SOURCE: Hernández G et al. JAMA 2019 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0071.

SAN DIEGO – During resuscitation of patients but missed statistical significance.

Although the paper, published online in JAMA, concludes that normalization of capillary refill time cannot be recommended over targeting serum lactate levels, Glenn Hernández, MD, PhD, sounded more optimistic after presenting the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “I think it’s good news to develop techniques that, even though they have this integrated variability, they can provide a signal that is also very close to the [underlying] physiology,” Dr. Hernández, who is a professor of intensive medicine at Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. The Peripheral perfusion was also associated with lower mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score at 72 hours.

The technique involves pressing a glass microscope slide to the ventral surface of the right index finger distal phalanx, increasing pressure and maintaining pressure for 10 seconds. After release, a chronometer assessed return of normal skin color, with refill times over 3 seconds considered abnormal. Clinicians applied the technique every 30 minutes during until normalization (every hour after that), compared with every 2 hours for the lactate arm of the study.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK randomized clinical trial was conducted at 28 hospitals in five countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Uruguay). The trial did not demonstrate superiority of capillary refill, and it was not designed for noninferiority. It nevertheless seems unlikely that assessment of capillary refill is inferior to lactate levels, according an accompanying editorial by JAMA-associated editor Derek Angus, MD, who also is a professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. The simplicity of using a capillary refill could be particularly useful in resource-limited settings, since it can be accomplished visually.

It also a natural marker for resuscitation. The body slows fluid flow to peripheral tissues until vital organs are well perfused. Normal capillary refill time “is an indirect signal of reperfusion,” said Dr. Hernández.

The researchers are not calling for this technique to replace lactate measurements, noting that in many ways the techniques can be complementary, since lactate levels are a good indicator of the patient’s overall improvement. In any case, it would take more research to prove superiority of the capillary refill, and that’s not something Dr. Hernández is planning to undertake. The current study had no external funding and required about half of his time over a 2-year period. Getting the work done at all “was sort of a miracle. We would not repeat this,” he said.

The researchers randomized 416 patients with septic shock (mean age, 63 years; 53% of whom were women) to be managed by peripheral perfusion or lactate measurement. By day 28, 43.4% in the lactate group had died, compared with 34.9% in the peripheral perfusion group (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .06). At 72 hours, the peripheral perfusion group had less organ dysfunction as measured by SOFA (mean, 5.6 vs. 6.6; P = .045). Six other secondary outcomes revealed no between-group differences.

The peripheral perfusion group received an average of 408 fewer mL of resuscitation fluids during the first 8 hours (P = .01).

That result fits with the greater responsiveness of peripheral perfusion measurements, and it’s relevant because some septic shock patients who are unresponsive to fluids often receive fluids anyway. “The general knowledge, though not correct, is that you treat lactate or blood pressure with fluids,” said coauthor Jan Bakker, MD, PhD, who is a professor at New York-Presbyterian Hospital Columbia University, and Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

After a series of observational studies suggested that warm, well-perfused patients were doing well, the idea was tested in a small interventional trial in which physicians were forbidden from giving fluids once patients were warm and well perfused. Patients did better than did those on standard of care. “We have said, if the patient is warm and well perfused, even if they are hypotensive, don’t give fluids, it won’t benefit them anymore. Give vasopressors or whatever, but don’t give fluids,” said Dr. Bakker.

The latest research also reinforced a signal from the earlier, smaller trial. “You get less organ failure if you use [fewer] fluids,” Dr. Bakker added.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hernández and Dr. Bakker had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Angus received consulting fees from Ferring Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer AG, and others outside the submitted work; he also has patents pending for compounds, compositions, and methods for treating sepsis and for proteomic biomarkers.

SOURCE: Hernández G et al. JAMA 2019 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0071.

SAN DIEGO – During resuscitation of patients but missed statistical significance.

Although the paper, published online in JAMA, concludes that normalization of capillary refill time cannot be recommended over targeting serum lactate levels, Glenn Hernández, MD, PhD, sounded more optimistic after presenting the study at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. “I think it’s good news to develop techniques that, even though they have this integrated variability, they can provide a signal that is also very close to the [underlying] physiology,” Dr. Hernández, who is a professor of intensive medicine at Pontifical Catholic University in Santiago, Chile. The Peripheral perfusion was also associated with lower mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score at 72 hours.

The technique involves pressing a glass microscope slide to the ventral surface of the right index finger distal phalanx, increasing pressure and maintaining pressure for 10 seconds. After release, a chronometer assessed return of normal skin color, with refill times over 3 seconds considered abnormal. Clinicians applied the technique every 30 minutes during until normalization (every hour after that), compared with every 2 hours for the lactate arm of the study.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK randomized clinical trial was conducted at 28 hospitals in five countries (Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Uruguay). The trial did not demonstrate superiority of capillary refill, and it was not designed for noninferiority. It nevertheless seems unlikely that assessment of capillary refill is inferior to lactate levels, according an accompanying editorial by JAMA-associated editor Derek Angus, MD, who also is a professor of critical care medicine at the University of Pittsburgh. The simplicity of using a capillary refill could be particularly useful in resource-limited settings, since it can be accomplished visually.

It also a natural marker for resuscitation. The body slows fluid flow to peripheral tissues until vital organs are well perfused. Normal capillary refill time “is an indirect signal of reperfusion,” said Dr. Hernández.

The researchers are not calling for this technique to replace lactate measurements, noting that in many ways the techniques can be complementary, since lactate levels are a good indicator of the patient’s overall improvement. In any case, it would take more research to prove superiority of the capillary refill, and that’s not something Dr. Hernández is planning to undertake. The current study had no external funding and required about half of his time over a 2-year period. Getting the work done at all “was sort of a miracle. We would not repeat this,” he said.

The researchers randomized 416 patients with septic shock (mean age, 63 years; 53% of whom were women) to be managed by peripheral perfusion or lactate measurement. By day 28, 43.4% in the lactate group had died, compared with 34.9% in the peripheral perfusion group (hazard ratio, 0.75; P = .06). At 72 hours, the peripheral perfusion group had less organ dysfunction as measured by SOFA (mean, 5.6 vs. 6.6; P = .045). Six other secondary outcomes revealed no between-group differences.

The peripheral perfusion group received an average of 408 fewer mL of resuscitation fluids during the first 8 hours (P = .01).

That result fits with the greater responsiveness of peripheral perfusion measurements, and it’s relevant because some septic shock patients who are unresponsive to fluids often receive fluids anyway. “The general knowledge, though not correct, is that you treat lactate or blood pressure with fluids,” said coauthor Jan Bakker, MD, PhD, who is a professor at New York-Presbyterian Hospital Columbia University, and Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands.

After a series of observational studies suggested that warm, well-perfused patients were doing well, the idea was tested in a small interventional trial in which physicians were forbidden from giving fluids once patients were warm and well perfused. Patients did better than did those on standard of care. “We have said, if the patient is warm and well perfused, even if they are hypotensive, don’t give fluids, it won’t benefit them anymore. Give vasopressors or whatever, but don’t give fluids,” said Dr. Bakker.

The latest research also reinforced a signal from the earlier, smaller trial. “You get less organ failure if you use [fewer] fluids,” Dr. Bakker added.

The study received no external funding. Dr. Hernández and Dr. Bakker had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Angus received consulting fees from Ferring Pharmaceutical, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer AG, and others outside the submitted work; he also has patents pending for compounds, compositions, and methods for treating sepsis and for proteomic biomarkers.

SOURCE: Hernández G et al. JAMA 2019 Feb 17. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0071.

REPORTING FROM CCC48

Final ‘Vision’ report addresses MOC woes

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.

“A new term that communicates the concept, intent, and expectations of continuing certification programs should be adopted by the ABMS in order to reengage disaffected diplomates and assure the public and other stakeholders that the certificate has enduring meaning and value,” according to the final report. A new term was not suggested.

The commission recommended a continuing certification system with four aims:

- Become a meaningful, contemporary, and relevant professional development activity for diplomates that ensures they remain up-to-date in their specialty.

- Demonstrate a commitment to professional self-regulation to both diplomates and the public.

- Align with international and national standards for certification programs.

- Provide a specialty-based credential that would be of value to diplomates and to multiple stakeholders, including patients, families, the public, and health care institutions.

Testing methods and situations must be simplified and updated, according to the report, which was submitted to ABMS on Feb. 12. Continuing certification “must change to incorporate longitudinal and other innovative formative assessment strategies that support learning, identify knowledge and skills gaps, and help diplomates stay current. The ABMS Boards must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.” In addition, the boards “must no longer use a single point-in-time examination or a series of single point-in-time assessments as the sole method to determine certification status.”

Instead, the commission recommends that ABMS “move quickly to formative assessment formats that are not characterized by high-stakes summative outcomes (pass/fail), specified time frames for high-stakes assessment, or require burdensome testing formats (such as testing centers or remote proctoring) that are inconsistent with the desired goals for continuing certification – support learning; identify knowledge and skills gaps; and help diplomates stay current.”

The commission also defined how the certification process should be used by other stakeholders.

“ABMS must demonstrate and communicate that continuing certification has value, meaning, and purpose in the health care environment,” the report states. “Hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations can independently decide what factors are used in credentialing and privileging decisions. ABMS must inform these organizations that continuing certification should not be the only criterion used in these decisions, and these organizations should use a wide portfolio of criteria in these decisions. ABMS must encourage hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations to not deny credentialing or privileging to a physician solely on the basis of certification status.”

Additionally, the commission report states that “ABMS and the ABMS Boards should collaborate with specialty societies, the [continuing medical education/continuing professional development] community, and other expert stakeholders to develop the infrastructure to support learning activities that produce data-driven advances in clinical practice. The ABMS Boards must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage.”

The report adds that the boards “should readily accept existing activities that diplomates are doing to advance their clinical practice and to provide credit for performing low-resource, high-impact activities as part of their daily practice routine.”

The commission’s final report incorporates a number of changes that physicians offered based on a draft version of the report.

The American College of Physicians commented that it “objects to the use of data regarding quality measures for individual diplomate certification status, because physician-level measures of quality are flawed, and because physician-level data inevitably leads to physician-level documentation burden. Flawed performance measures also often inadequately adjust for patient comorbidities and socioeconomic status, which leads to assessments that do not reflect the actual quality of care.”

Similarly, the American Society of Hematology noted in a statement that it “disagrees with the commission’s recommendation to retain the reporting of practice improvement activities as part of continuous certification due to direct and indirect costs needed to fulfill this requirement on top of requirements for engagement in quality improvement mandated by insurers, institutions, and health systems.”

While the draft report recommended that specialty boards provide aggregated feedback to medical societies, a more individualized dissemination on the gaps in knowledge would be more helpful, according to Doug Henley, MD, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, who said that a more individualized approach would help his organization better provide CME to its members to help fill in the knowledge gaps.

“If we can identify these and use other processes and then target at the individual level to seek improvement, I think that will be a better outcome rather than just x learners don’t do well in diabetic care,” he said in an interview. “That doesn’t really help me in terms of who needs the real education in diabetic care versus who needs it for heart failure.”

The final recommendation notes that ABMS member boards “must collaborate with professional and/or CME/CPD organizations to share data and information to guide and support diplomate engagement in continuing certification.”

The document further clarifies that the boards should examine “the aggregated results from assessments to identify knowledge, skills, and other competency gaps,” and the aggregated data should be shared with specialty societies, CME/CPD providers, quality improvement professionals, and other health care organizations.

One weakness in the draft noted by Dr. Henley was the lack of a more forceful tone within the recommendations. Even though AMBS is not bound by its recommendations, he said that he would like to see stronger language throughout the document.

“We would certainly hope that the ABMS and the member boards will follow the direction of the Vision Commission very directly and succinctly,” he said. “That is why we suggested that some of the recommendations from the Vision Commission should use words like ‘should’ and ‘must’ and not just ‘encourage’ and words like that.”

That recommendation was taken and implemented in the final document.

Societies differed in how often participation in the certification process should occur.

The American College of Rheumatology in its comments challenged a recommendation that certification should be structured to expect participation on an annual basis.

“The ACR supports the importance of ongoing learning,” it stated. “However, no discussion is provided as to how and why the recommendation for annual participation by diplomates was conceived. For some ABMS Boards, an annual requirement will increase physician burden unless continuing certification is modified to a formative pathway. If this recommendation is to be retained, the commission would be encouraged to emphasize that inclusion of annual participation should be part of an overall program structure plan that supports a formative approach to assessment. In addition, the ACR requests that ABMS Boards allow exceptions without penalty to be made to this annual requirement to all for live events.”

The American College of Cardiology took a different point of view with regard to this recommendation.

In its comments, ACC stated that it “concurs with this recommendation. Annual participation is a feature of the ACC’s proposed maintenance of certification solution. The ACC believes that ABMS boards should recognize, and make allowances for, physicians who may, for valid reasons (illness, sabbatical, medical or family issue) may not participate in MOC for a period of a year.” ACC generally concurred with the recommendations in the draft.

The final document presented the commission’s view that the ABMS member boards “need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years. The ABMS Boards should develop a diplomate engagement strategy and support the idea that diplomates are committed to learning and continually improving their practice, skills, and competencies. The ABMS Boards should expect that diplomates would engage in some learning, assessment, or advancing practice work annually.”

The American Gastroenterological Association, in its comment letter on the draft, said it was “greatly concerned” about the inclusion of practice improvement data, noting it is “debatable whether it is even within the appropriate domain of the boards to assume responsibility for clinical practice performance and quality assurance.”

The final report states that ABMS “must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage,” and added that “when appropriate, taking advantage of other organizations’ quality improvement and reporting activities should be maximized to avoid additional burdens on diplomates.”

ABMS and its board are not bound to follow any of the recommendations contained within the report, but the commission states that it “expects that the ABMS and the ABMS Boards, in collaboration with professional organizations and other stakeholders, will prioritize these recommendations and develop the necessary strategies and infrastructure to implement them.”

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.

“A new term that communicates the concept, intent, and expectations of continuing certification programs should be adopted by the ABMS in order to reengage disaffected diplomates and assure the public and other stakeholders that the certificate has enduring meaning and value,” according to the final report. A new term was not suggested.

The commission recommended a continuing certification system with four aims:

- Become a meaningful, contemporary, and relevant professional development activity for diplomates that ensures they remain up-to-date in their specialty.

- Demonstrate a commitment to professional self-regulation to both diplomates and the public.

- Align with international and national standards for certification programs.

- Provide a specialty-based credential that would be of value to diplomates and to multiple stakeholders, including patients, families, the public, and health care institutions.

Testing methods and situations must be simplified and updated, according to the report, which was submitted to ABMS on Feb. 12. Continuing certification “must change to incorporate longitudinal and other innovative formative assessment strategies that support learning, identify knowledge and skills gaps, and help diplomates stay current. The ABMS Boards must offer an alternative to burdensome highly secure, point-in-time examinations of knowledge.” In addition, the boards “must no longer use a single point-in-time examination or a series of single point-in-time assessments as the sole method to determine certification status.”

Instead, the commission recommends that ABMS “move quickly to formative assessment formats that are not characterized by high-stakes summative outcomes (pass/fail), specified time frames for high-stakes assessment, or require burdensome testing formats (such as testing centers or remote proctoring) that are inconsistent with the desired goals for continuing certification – support learning; identify knowledge and skills gaps; and help diplomates stay current.”

The commission also defined how the certification process should be used by other stakeholders.

“ABMS must demonstrate and communicate that continuing certification has value, meaning, and purpose in the health care environment,” the report states. “Hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations can independently decide what factors are used in credentialing and privileging decisions. ABMS must inform these organizations that continuing certification should not be the only criterion used in these decisions, and these organizations should use a wide portfolio of criteria in these decisions. ABMS must encourage hospitals, health systems, payers, and other health care organizations to not deny credentialing or privileging to a physician solely on the basis of certification status.”

Additionally, the commission report states that “ABMS and the ABMS Boards should collaborate with specialty societies, the [continuing medical education/continuing professional development] community, and other expert stakeholders to develop the infrastructure to support learning activities that produce data-driven advances in clinical practice. The ABMS Boards must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage.”

The report adds that the boards “should readily accept existing activities that diplomates are doing to advance their clinical practice and to provide credit for performing low-resource, high-impact activities as part of their daily practice routine.”

The commission’s final report incorporates a number of changes that physicians offered based on a draft version of the report.

The American College of Physicians commented that it “objects to the use of data regarding quality measures for individual diplomate certification status, because physician-level measures of quality are flawed, and because physician-level data inevitably leads to physician-level documentation burden. Flawed performance measures also often inadequately adjust for patient comorbidities and socioeconomic status, which leads to assessments that do not reflect the actual quality of care.”

Similarly, the American Society of Hematology noted in a statement that it “disagrees with the commission’s recommendation to retain the reporting of practice improvement activities as part of continuous certification due to direct and indirect costs needed to fulfill this requirement on top of requirements for engagement in quality improvement mandated by insurers, institutions, and health systems.”

While the draft report recommended that specialty boards provide aggregated feedback to medical societies, a more individualized dissemination on the gaps in knowledge would be more helpful, according to Doug Henley, MD, CEO of the American Academy of Family Physicians, who said that a more individualized approach would help his organization better provide CME to its members to help fill in the knowledge gaps.

“If we can identify these and use other processes and then target at the individual level to seek improvement, I think that will be a better outcome rather than just x learners don’t do well in diabetic care,” he said in an interview. “That doesn’t really help me in terms of who needs the real education in diabetic care versus who needs it for heart failure.”

The final recommendation notes that ABMS member boards “must collaborate with professional and/or CME/CPD organizations to share data and information to guide and support diplomate engagement in continuing certification.”

The document further clarifies that the boards should examine “the aggregated results from assessments to identify knowledge, skills, and other competency gaps,” and the aggregated data should be shared with specialty societies, CME/CPD providers, quality improvement professionals, and other health care organizations.

One weakness in the draft noted by Dr. Henley was the lack of a more forceful tone within the recommendations. Even though AMBS is not bound by its recommendations, he said that he would like to see stronger language throughout the document.

“We would certainly hope that the ABMS and the member boards will follow the direction of the Vision Commission very directly and succinctly,” he said. “That is why we suggested that some of the recommendations from the Vision Commission should use words like ‘should’ and ‘must’ and not just ‘encourage’ and words like that.”

That recommendation was taken and implemented in the final document.

Societies differed in how often participation in the certification process should occur.

The American College of Rheumatology in its comments challenged a recommendation that certification should be structured to expect participation on an annual basis.

“The ACR supports the importance of ongoing learning,” it stated. “However, no discussion is provided as to how and why the recommendation for annual participation by diplomates was conceived. For some ABMS Boards, an annual requirement will increase physician burden unless continuing certification is modified to a formative pathway. If this recommendation is to be retained, the commission would be encouraged to emphasize that inclusion of annual participation should be part of an overall program structure plan that supports a formative approach to assessment. In addition, the ACR requests that ABMS Boards allow exceptions without penalty to be made to this annual requirement to all for live events.”

The American College of Cardiology took a different point of view with regard to this recommendation.

In its comments, ACC stated that it “concurs with this recommendation. Annual participation is a feature of the ACC’s proposed maintenance of certification solution. The ACC believes that ABMS boards should recognize, and make allowances for, physicians who may, for valid reasons (illness, sabbatical, medical or family issue) may not participate in MOC for a period of a year.” ACC generally concurred with the recommendations in the draft.

The final document presented the commission’s view that the ABMS member boards “need to engage with diplomates on an ongoing basis instead of every 2, 5, or 10 years. The ABMS Boards should develop a diplomate engagement strategy and support the idea that diplomates are committed to learning and continually improving their practice, skills, and competencies. The ABMS Boards should expect that diplomates would engage in some learning, assessment, or advancing practice work annually.”

The American Gastroenterological Association, in its comment letter on the draft, said it was “greatly concerned” about the inclusion of practice improvement data, noting it is “debatable whether it is even within the appropriate domain of the boards to assume responsibility for clinical practice performance and quality assurance.”

The final report states that ABMS “must ensure that their continuing certification programs recognize and document participation in a wide range of quality assessment activities in which diplomates already engage,” and added that “when appropriate, taking advantage of other organizations’ quality improvement and reporting activities should be maximized to avoid additional burdens on diplomates.”

ABMS and its board are not bound to follow any of the recommendations contained within the report, but the commission states that it “expects that the ABMS and the ABMS Boards, in collaboration with professional organizations and other stakeholders, will prioritize these recommendations and develop the necessary strategies and infrastructure to implement them.”

Whatever you do, change the name.

That was key among the final recommendations the Vision Initiative Commission submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties on how to improve the maintenance of certification process.