User login

BNP levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Does B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) have prognostic value outside of heart failure (HF) patients?

Background: BNP levels are influenced by both cardiac and extracardiac stimuli and thus might have prognostic value outside of the traditional use to guide therapy for HF patients.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study of the Vanderbilt electronic health record.

Setting: Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn.

Synopsis: The study evaluated 30,487 patients with at least two BNP values for 2002-2015. Within this cohort, 62% of patients did not have a HF diagnosis. Risk of death was elevated in all patients regardless of HF status as BNP values rose. An increase from the 25th to 75th percentile in BNP value was associated with an increased risk of death in non-HF patients (hazard ratio, 2.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.99-2.2). Additionally, in a multivariate analysis BNP was the strongest predictor of death, compared with traditional risk factors in both HF and non-HF patients. The main limitation to this study was the use of ICD codes for diagnosis of HF.

Bottom line: BNP has predictive value for risk of death in non-HF patients; as BNP levels rise, regardless of HF status, so does risk of death.

Citation: York MK et al. B-type natriuretic peptide levels and mortality in patients with and without heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 15;71(19):2079-88.

Dr. Abramowicz is an assistant professor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

FDA approval of powerful opioid tinged with irony

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

The timing of the Food and Drug Administration’s Nov. 2 approval of the medication Dsuvia, a sublingual formulation of the synthetic opioid sufentanil, is interesting – to say the least. Dsuvia is a powerful pain medication, said to be 10 times more potent than fentanyl and 1,000 times more potent than morphine. The medication, developed by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals for use in medically supervised settings, has an indication for moderate to severe pain, and is packaged in single-dose applicators.

The chairperson of the FDA’s Anesthetic and Analgesics Drug Product Advisory Committee, Raeford E. Brown Jr., MD, a professor of pediatric anesthesia at the University of Kentucky, Lexington, could not be present Oct. 12 at the committee vote recommending approval. With the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, Dr. Brown wrote a letter to FDA leaders detailing concerns about the new formulation of sufentanil.

“It is my observation,” Dr. Brown wrote, “that once the FDA approves an opioid compound, there are no safeguards as to the population that will be exposed, the postmarketing analysis of prescribing behavior, or the ongoing analysis of the risks of the drug to the general population relative to its benefit to the public health. Briefly stated, for all of the opioids that have been marketed in the last 10 years, there has not been sufficient demonstration of safety, nor has there been postmarketing assessment of who is taking the drug, how often prescribing is inappropriate, and whether there was ever a reason to risk the health of the general population by having one more opioid on the market.”

Dr. Brown went on to detail his concerns about sufentanil. In the intravenous formulation, the medication has been in use for more than two decades.

“It is so potent that abusers of this intravenous formulation often die when they inject the first dose; I have witnessed this in resuscitating physicians, medical students, technicians, and other health care providers, some successfully, as a part of my duties as a clinician in a major academic medical center. Because it is so potent, the dosing volume, whether in the IV formulation or the sublingual form, can be quite small. It is thus an extremely divertible drug, and I predict that we will encounter diversion, abuse, and death within the early months of its availability on the market.”

The letter finishes by criticizing the fact that the full Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee was not invited to the Oct. 12 meeting, and finally, about the ease of diversion among health care professionals – and anesthesiologists in particular.

Meanwhile, Scott Gottlieb, MD, commissioner of the FDA, posted a lengthy explanation on the organization’s website on Nov. 2, after the vote. In his statement on the agency’s approval of Dsuvia and the FDA’s future consideration of new opioids, Dr. Gottlieb explains: “To address concerns about the potential risks associated with Dsuvia, this product will have strong limitations on its use. It can’t be dispensed to patients for home use and should not be used for more than 72 hours. And it should only be administered by a health care provider using a single-dose applicator. That means it won’t be available at retail pharmacies for patients to take home. These measures to restrict the use of this product only within a supervised health care setting, and not for home use, are important steps to help prevent misuse and abuse of Dsuvia, as well reduce the potential for diversion. Because of the risks of addiction, abuse, and misuse with opioids, Dsuvia also is to be reserved for use in patients for whom alternative pain treatment options have not been tolerated, or are not expected to be tolerated, where existing treatment options have not provided adequate analgesia, or where these alternatives are not expected to provide adequate analgesia.”

In addition to the statement posted on the FDA’s website, Dr. Gottlieb made the approval of Dsuvia the topic of his weekly #SundayTweetorial on Nov. 4. In this venue, Dr. Gottlieb posts tweets on a single topic. On both Twitter and the FDA website, he noted that a major factor in the approval of Dsuvia was advantages it might convey for pain control to soldiers on the battlefield, where oral medications might take time to work and intravenous access might not be possible.

One tweet read: “Whether there’s a need for another powerful opioid in the throes of a massive crisis of addiction is a critical question. As a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question for patients with pain, for the addiction crisis, for innovators, for all Americans.”

Another tweet stated, “While Dsuvia brings another highly potent opioid to market it fulfills a limited, unmet medical need in treating our nation’s soldiers on the battlefield. That’s why the Pentagon worked closely with the sponsor on developing Dsuvia. FDA committed to prioritize needs of our troops.”

in possible deaths from misdirected use of a very potent agent. And while the new opioid may have been geared toward unmet military needs, Dsuvia will be available for use in civilian medical facilities as well.

There is some irony to the idea that a pharmaceutical company would continue to develop opioids when there is so much need for nonaddictive agents for pain control and so much pressure on physicians to limit access of opiates to pain patients. We are left to stand by and watch as yet another potent opioid preparation is introduced.

Dr. Miller is coauthor of “Committed: The Battle Over Involuntary Psychiatric Care” (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016), and assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.

Guideline authors inconsistently disclose conflicts

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730. Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

None of the guidelines included in either study was fully compliant with National Academy of Medicine standards, which include written disclosure, appointing committee chairs or cochairs with no conflicts of interest, and keeping committee members with conflicts to a minority of the committee membership, wrote Colette DeJong, MD, and Robert Steinbrook, MD, in an accompanying editorial. In the study by Khan et al., “Notably, 14 of the 18 panels had chairs with industry payments, and 10 had a majority of members with payments,” they wrote.

However, the federal government has so far shown no interest in supporting a fully independent entity to develop clinical practice guidelines, as occurs in the United Kingdom via the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Preparation of guidelines by an independent public body with assured funding and independence could be an effective approach, not only for eliminating issues related to financial conflicts of interest but also for assuring the use of rigorous methodologies and avoiding the wasteful duplication of efforts by multiple committees,” they wrote.

Financial conflicts in clinical practice guidelines persist in the United States in part because many professional societies have financial conflicts with industry, the editorialists wrote.

“Robust, objective, and unbiased clinical practice guidelines support improvements in patient care; the best interests of patients are the paramount consideration,” they emphasized (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4974).

Dr. DeJong is affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Steinbrook is Editor at Large for JAMA Internal Medicine. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

None of the guidelines included in either study was fully compliant with National Academy of Medicine standards, which include written disclosure, appointing committee chairs or cochairs with no conflicts of interest, and keeping committee members with conflicts to a minority of the committee membership, wrote Colette DeJong, MD, and Robert Steinbrook, MD, in an accompanying editorial. In the study by Khan et al., “Notably, 14 of the 18 panels had chairs with industry payments, and 10 had a majority of members with payments,” they wrote.

However, the federal government has so far shown no interest in supporting a fully independent entity to develop clinical practice guidelines, as occurs in the United Kingdom via the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Preparation of guidelines by an independent public body with assured funding and independence could be an effective approach, not only for eliminating issues related to financial conflicts of interest but also for assuring the use of rigorous methodologies and avoiding the wasteful duplication of efforts by multiple committees,” they wrote.

Financial conflicts in clinical practice guidelines persist in the United States in part because many professional societies have financial conflicts with industry, the editorialists wrote.

“Robust, objective, and unbiased clinical practice guidelines support improvements in patient care; the best interests of patients are the paramount consideration,” they emphasized (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4974).

Dr. DeJong is affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Steinbrook is Editor at Large for JAMA Internal Medicine. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

None of the guidelines included in either study was fully compliant with National Academy of Medicine standards, which include written disclosure, appointing committee chairs or cochairs with no conflicts of interest, and keeping committee members with conflicts to a minority of the committee membership, wrote Colette DeJong, MD, and Robert Steinbrook, MD, in an accompanying editorial. In the study by Khan et al., “Notably, 14 of the 18 panels had chairs with industry payments, and 10 had a majority of members with payments,” they wrote.

However, the federal government has so far shown no interest in supporting a fully independent entity to develop clinical practice guidelines, as occurs in the United Kingdom via the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. “Preparation of guidelines by an independent public body with assured funding and independence could be an effective approach, not only for eliminating issues related to financial conflicts of interest but also for assuring the use of rigorous methodologies and avoiding the wasteful duplication of efforts by multiple committees,” they wrote.

Financial conflicts in clinical practice guidelines persist in the United States in part because many professional societies have financial conflicts with industry, the editorialists wrote.

“Robust, objective, and unbiased clinical practice guidelines support improvements in patient care; the best interests of patients are the paramount consideration,” they emphasized (JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4974).

Dr. DeJong is affiliated with the University of California, San Francisco; Dr. Steinbrook is Editor at Large for JAMA Internal Medicine. They had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730. Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

Financial conflicts are often underreported by authors of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) in several specialties including oncology, rheumatology, and gastroenterology, according to a pair of research letters published in JAMA Internal Medicine. The Institute of Medicine recommends that guideline authors include no more than 50% individuals with financial conflicts.

In one research letter, Rishad Khan, BSc, of the University of Toronto in Ontario and his colleagues reviewed data on undeclared financial conflicts of interest among authors of guidelines related to high-revenue medications.

The researchers identified CPGs via the National Guideline Clearinghouse and selected 18 CPGs for 10 high-revenue medications published between 2013 and 2017. Financial conflicts of interest were based on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Open Payments.

Of the 160 authors involved in the various guidelines, 79 (49.4%) disclosed a payment in the CPG or supplemental materials, and 50 (31.3%) disclosed payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in the related guidelines.

Another 41 authors (25.6%) received but did not disclose payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications in CPGs.

Overall, 91 authors (56.9%) were found to have financial conflicts of interest that involved 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications, and “the median value of undeclared payments from companies marketing 1 of the 10 high-revenue medications recommended in the CPGs was $522 (interquartile range, $0-$40,444) from two companies,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including “potential inaccuracies in CMS-OP reporting, which are rarely corrected, and lack of generalizability outside the United States” and by the limited time frame for data collection, which may have led to underestimation of conflicts for the guidelines, the researchers noted. In addition, “we did not have access to guideline voting records and thus did not know when conflicted panel members recommended against a medication or recused themselves from voting,” they said.

Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals.

In a second research letter, half of the authors of gastroenterology guidelines received payments from industry, wrote Tyler Combs, BS, of Oklahoma State University, Tulsa, and his colleagues. Previous studies have reviewed the financial conflicts of interest in specialties including oncology, dermatology, and otolaryngology, but financial conflicts of interest among authors of gastroenterology guidelines have not been examined, the researchers said.

Mr. Combs and his colleagues identified 15 CPGs published by the American College of Gastroenterology between 2014 and 2016. They identified 83 authors, with an average of 4 authors for each guideline. Overall, 53% of the authors received industry payments, according to based on data from the 2014 to 2016 Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Open Payments database (OPD).

However, OPD information was not always consistent with information published with the guidelines, the researchers noted. They found that 16 (19%) of the 83 authors both disclosed financial conflicts of interests in the CPGs and had received payments according to OPD or had disclosed no financial conflicts of interest and had received no payments according to OPD. In addition, 49 (34%) of 146 cumulative financial conflicts of interest disclosed in the CPGs and 148 relationships identified on OPD were both disclosed as financial conflicts of interest and evidenced by OPD payment records. In this review, the median total payment was $1,000, with an interquartile range from $0 to $39,938.

The study findings were limited by a relatively short 12-month time frame, the researchers noted. However, “our finding that FCOI [financial conflicts of interest] disclosure only corroborates with OPD payment records between 19% and 34% of the time also suggests that guidance from the ACG [American College of Gastroenterology] may be needed to improve FCOI disclosure efforts in future iterations of gastroenterology CPGs,” they said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730. Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Financial conflicts of interest in the development of clinical guidelines persist in the United States.

Major finding: Approximately half of the committee members of guidelines in both studies had financial relationships; many were undisclosed and involved substantial payments.

Study details: The data come from two research letters, including 15 gastroenterology guidelines and 18 guidelines from multiple specialties.

Disclosures: Mr. Khan disclosed research funding from AbbVie and Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Mr. Combs had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Combs T et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730. Khan R et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Oct 29. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5106.

Quick Byte: Palliative care

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

Rapid adoption of a key program

Rapid adoption of a key program

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

In 2015, 75% of U.S. hospitals with more than 50 beds had palliative care programs – a sharp increase from the 25% that had palliative care in 2000.

“The rapid adoption of this high-value program, which is voluntary and runs counter to the dominant culture in U.S. hospitals, was catalyzed by tens of millions of dollars in philanthropic support for innovation, dissemination, and professionalization in the palliative care field,” according to research published in Health Affairs.

Reference

Cassel JB et al. Palliative care leadership centers are key to the diffusion of palliative care innovation. Health Aff. 2018 Feb. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1122.

FDA approves sufentanil for adults with acute pain

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

The Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 approved sufentanil (Dsuvia) for managing acute pain in adult patients in certified, medically supervised health care settings.

Sufentanil, an opioid analgesic manufactured by AcelRx Pharmaceuticals, was approved as a 30-mcg sublingual tablet. The efficacy of Dsuvia was shown in a randomized, clinical trial where patients who received the drug demonstrated significantly greater pain relief after both 15 minutes and 12 hours, compared with placebo.

“As a single-dose, noninvasive medication with a rapid reduction in pain intensity, Dsuvia represents an important alternative for health care providers to offer patients for acute pain management,” David Leiman, MD, of the department of surgery at the University of Texas, Houston, said in the AcelRx press statement.

FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, commented on the approval amid concerns expressed by some, such as the advocacy group Public Citizen, that the drug is “more than 1,000 times more potent than morphine,” and that approval could lead to diversion and abuse – particularly in light of the U.S. opioid epidemic.

In his statement, Dr. Gottlieb identified one broad, significant issue. “Why do we need an oral formulation of sufentanil – a more potent form of fentanyl that’s been approved for intravenous and epidural use in the U.S. since 1984 – on the market?”

In particular, he focused on the needs of the military. The Department of Defense has taken interest in sufentanil as it fulfills a small but specific battlefield need, namely as a means of pain relief in battlefield situations where soldiers cannot swallow oral medication and access to intravenous medication is limited.

Dr. Gottlieb made clear that sufentanil was meant only to be taken in controlled settings and will have strong limitations on its use. It cannot be prescribed for home use, and treatment should be limited to 72 hours. It can only be delivered by health care professionals using a single-dose applicator and will not be available in pharmacies. It is only to be used in patients who have not tolerated or are expected not to tolerate alternative methods of pain management.

“The FDA has implemented a REMS [Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy] that reflects the potential risks associated with this product and mandates that Dsuvia will only be made available for use in a certified medically supervised heath care setting, including its use on the battlefield,” Dr. Gottlieb said.

However, he recognized that the debate runs deeper than how the FDA should mitigate risk over a new drug, and “as a public health agency, we have an obligation to address this question openly and directly. As a physician and regulator, I won’t bypass legitimate questions and concerns related to our role in addressing the opioid crisis,” he said.

Find Dr. Gottlieb’s full statement on the FDA website.

Focus on patient experience to cut readmission rates

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Incorporate patient-reported quality measures

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

Hospitalists have focused much attention on reducing 30-day readmission rates, at a time when 15-20% of health care dollars spent on those readmissions is considered potentially preventable.

But until very recently, no study has explored patient perceptions of the likelihood of readmission during index admission. Now, that’s changed.

“Our objective was to examine associations between patient perceptions of care during index hospital admission and 30-day readmission,” says Jocelyn Carter, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and lead author of November 2017 study in BMJ Quality & Safety.

Enrolled in the study were 846 patients at two inpatient adult medicine units at Massachusetts General, Boston; 201 (23.8%) of these patients were readmitted within 30 days. In multivariable models adjusting for baseline differences, respondents who reported being “very satisfied” with the care received during the index hospitalization were less likely to be readmitted; participants reporting that doctors “always listened to them carefully” also were less likely to be readmitted.

“These findings are important since they suggest that engaging patients in an assessment of communication quality, unmet needs, concerns, and overall experience during admission may help to identify issues that might not be captured in standard postdischarge surveys when the appropriate time for quality improvement interventions has passed,” Dr. Carter said. “Incorporating patient-reported measures during index hospitalizations may improve readmission rates and help predict which patients are more likely to be readmitted.”

Reference

Carter J et al. The association between patient experience factors and likelihood of 30-day readmission: A prospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf. 16 Nov 2017. Accessed Feb 2, 2018.

In pediatric ICU, being underweight can be deadly

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

SAN DIEGO – Underweight people don’t get much attention amid the obesity epidemic. But a new analysis of worldwide data finds that underweight pediatric ICU patients worldwide face a higher risk of death within 28 days than all their counterparts, even the overweight and obese.

While the report suggests that underweight patients weren’t sicker than the other children and young adults, they also faced a higher risk of fluid accumulation and all-stage acute kidney injury, compared with overweight children, study lead author Rajit K. Basu, MD, MS, of Emory University and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, said in an interview. His team’s findings were released at Kidney Week 2018, sponsored by the American Society of Nephrology.

“Obesity gets the lion’s share of the spotlight, but there is a large and likely growing population of children who, for reasons left to be fully parsed out, are underweight,” Dr. Basu said. “These patients have increased attributable risks for poor outcome.”

The new report is a follow-up analysis of a 2017 prospective study by the same team that tracked acute kidney injury and mortality in 4,683 pediatric ICU patients at 32 clinics in Asia, Australia, Europe, and North America. The patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, were recruited over 3 months in 2014 (N Engl J Med 2017;376:11-20).

The researchers launched the study to better understand the risk facing underweight pediatric patients. “There is a paucity of data linking mortality to weight classification in children,” Dr. Basu said. “There are only a few reports, and there is a suggestion that the ‘obesity paradox’ – protection from morbidity and mortality because of excessive weight – exists.”

For the new analysis, researchers tracked 3,719 patients: 29% were underweight, 44% had normal weight, 11% were overweight, and 16% were obese.

The 28-day mortality rate was 4% overall and highest in the underweight patients at 6%, compared with normal (3%), overweight (2%), and obese patients (2%) (P less than .0001). Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of mortality, compared with normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Underweight patients also had “a higher risk of fluid accumulation and a higher incidence of all-stage acute kidney injury, compared to overweight children,” Dr. Basu said.

The study authors also examined mortality rates in the 14% of patients (n = 542) who had sepsis. Again, underweight patients had the highest risk of 28-day mortality (15%), compared with normal weight (7%), overweight (4%), and obese patients (5%) (P = 0.003).

Who are the underweight children? “Analysis of the comorbidities reveals that nearly one-third of these children had some neuromuscular and/or pulmonary comorbidities, implying that these children were most likely static cerebral palsy children or had neuromuscular developmental disorder,” Dr. Basu said. “The demographic data also interestingly pointed out that the underweight population was predominantly Eastern Asian in origin.”

But there wasn’t a sign of increased illness in the underweight patients. “We can say that these kids were no sicker compared to the overweight kids as assessed by objective severity-of-illness scoring tools used in the critically ill population,” he said.

Is there a link between fluid overload and higher mortality numbers in underweight children? “There is a preponderance of data now, particularly in children, associating excessive fluid accumulation and poor outcome,” Dr. Basu said, who pointed to a 2018 systematic review and analysis that linked fluid overload to a higher risk of in-hospital mortality (OR, 4.34; 95% CI, 3.01-6.26) (JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172[3]:257-68).

Fluid accumulation disrupts organs “via hydrostatic pressure overregulation, causing an imbalance in local mediators of hormonal homeostasis and through vascular congestion,” he said. However, best practices regarding fluid are not yet clear.

“Fluid accumulation does occur frequently,” he said, “and it is likely a very important and relevant part of practice for bedside providers to be mindful on a multiple-times-a-day basis of what is happening with net fluid balance and how that relates to end-organ function, particularly the lungs and the kidneys.”

The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

REPORTING FROM KIDNEY WEEK 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Underweight patients had a higher adjusted risk of 28-day mortality than normal-weight patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-2.8).

Study details: A follow-up analysis of 3,719 pediatric ICU patients, aged from 3 months to 25 years, recruited in a prospective study over 3 months in 2014 at 32 worldwide centers.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health provided partial funding for the study. One of the authors received fellowship funding from Gambro/Baxter Healthcare.

How do you evaluate and treat a patient with C. difficile–associated disease?

Metronidazole is no longer recommended

Case

A 45-year-old woman on omeprazole for gastroesophageal reflux disease and recent treatment with ciprofloxacin for a urinary tract infection (UTI), who also has had several days of frequent watery stools, is admitted. She does not appear ill, and her abdominal exam is benign. She has normal renal function and white blood cell count. How should she be evaluated and treated for Clostridium difficile–associated disease (CDAD)?

Brief overview

C. difficile, a gram-positive anaerobic bacillus that exists in vegetative and spore forms, is a leading cause of hospital-associated diarrhea. C. difficile has a variety of presentations, ranging from asymptomatic colonization to CDAD, including severe diarrhea, ileus, and megacolon, and may be associated with a fatal outcome on rare occasions. The incidence of CDAD has been rising since the emergence of a hypervirulent strain (NAP1/BI/027) in the early 2000s and, not surprisingly, the number of deaths attributed to CDAD has also increased.1

CDAD requires acquisition of C. difficile as well as alteration in the colonic microbiota, often precipitated by antibiotics. The vegetative form of C. difficile can produce up to three toxins that are responsible for a cascade of reactions beginning with intestinal epithelial cell death followed by a significant inflammatory response and migration of neutrophils that eventually lead to the formation of the characteristic pseudomembranes.2

Until recently, the mainstay treatment for CDAD consisted of metronidazole and oral preparations of vancomycin. Recent results from randomized controlled trials and the increasing popularity of fecal microbiota transplant (FMT), however, have changed the therapeutic landscape of CDAD dramatically. Not surprisingly, the 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America joint guidelines for CDAD represent a significant change to the treatment of CDAD, compared with previous guidelines.3

Overview of data

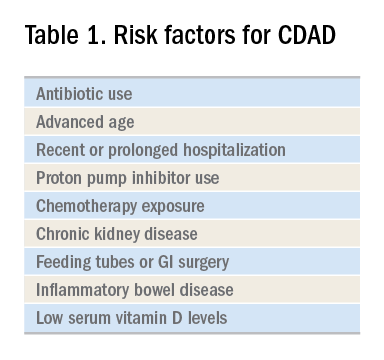

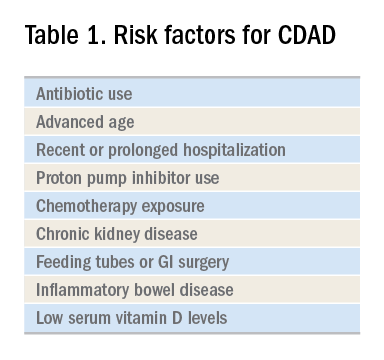

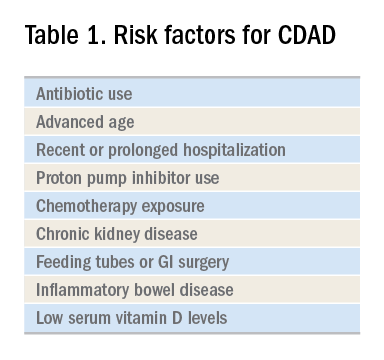

The hallmark of CDAD is a watery, nonbloody diarrhea. Given many other causes of diarrhea in hospitalized patients (e.g., direct effect of antibiotics, laxative use, tube feeding, etc.), hospitalists should focus on testing those patients who have three or more episodes of diarrhea in 24 hours and risk factors for CDAD (See Table 1).

Exposure to antibiotics remains the greatest risk factor. It’s important to note that, while most patients develop CDAD within the first month after receiving systemic antibiotics, many patients remain at risk for up to 3 months.4 Although exposure to antibiotics, particularly in health care settings, is a significant risk factor for CDAD, up to 30%-40% of community-associated cases may not have a substantial antibiotic or health care facility exposure.5

Hospitalists should also not overlook the association between proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of CDAD.3 Although the IDSA/SHEA guidelines do not recommend discontinuation of PPIs solely for treatment or prevention of CDAD, at the minimum, the indication for their continued use in patients with CDAD should be revisited.

Testing for CDAD ranges from immunoassays that detect an enzyme common to all strains of C. difficile, glutamate dehydrogenase antigen (GDH), or toxins to nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), such as polymerase chain reaction [PCR]).1,6 GDH tests have high sensitivity but poor specificity, while testing for the toxin has high specificity but lower sensitivity (40%-80%) for CDAD.1 Although NAATs are highly sensitive and specific, they often have a poor positive predictive value in low-risk populations (e.g., those who do not have true diarrhea or whose diarrhea resolves before test results return). In these patients, a positive NAAT test may reflect colonization with toxigenic C. difficile, not necessarily CDAD. Except in rare instances, laboratories should only accept unformed stools for testing. Since the choice of testing for C. difficile varies by institution, hospitalists should understand the algorithm used by their respective hospitals and familiarize themselves with the sensitivity and specificity of each test.

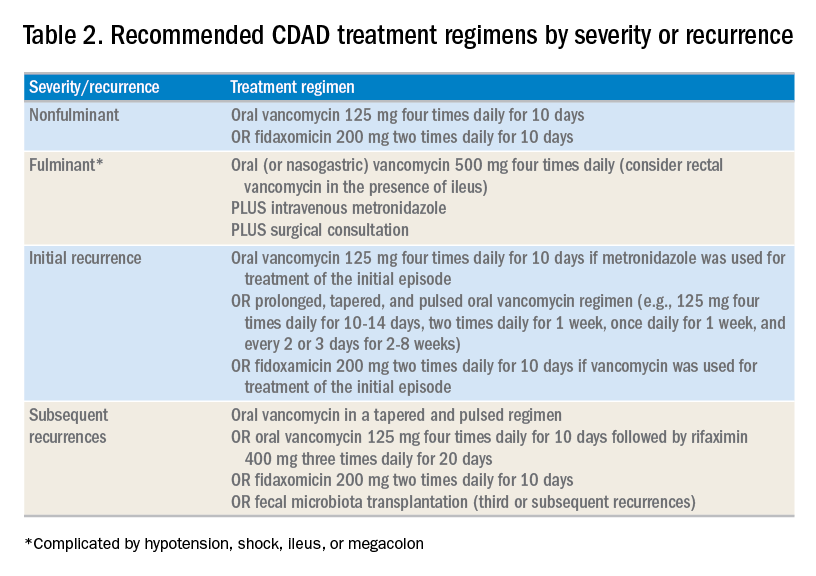

Once a patient is diagnosed with CDAD, the hospitalist should assess the severity of the disease. The IDSA/SHEA guidelines still use leukocytosis and creatinine to separate mild from severe cases; the presence of fever and hypoalbuminemia also points to a more complicated course.3

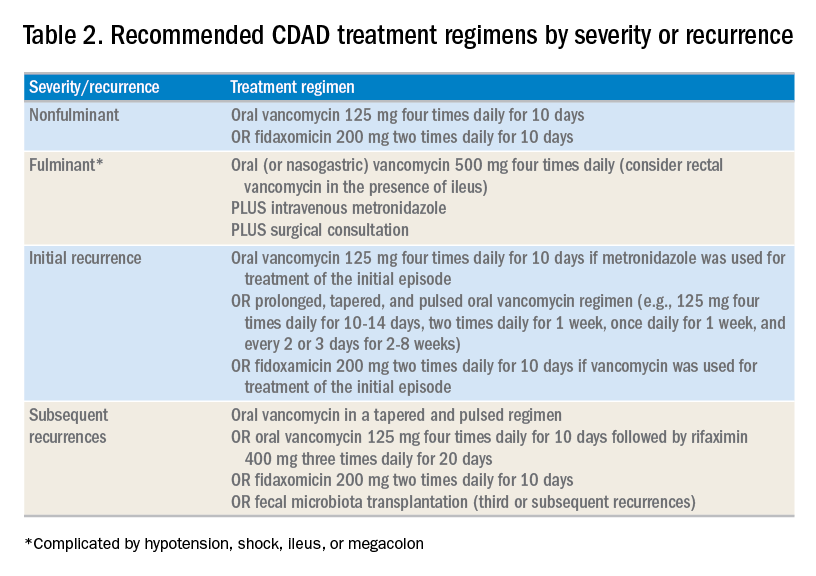

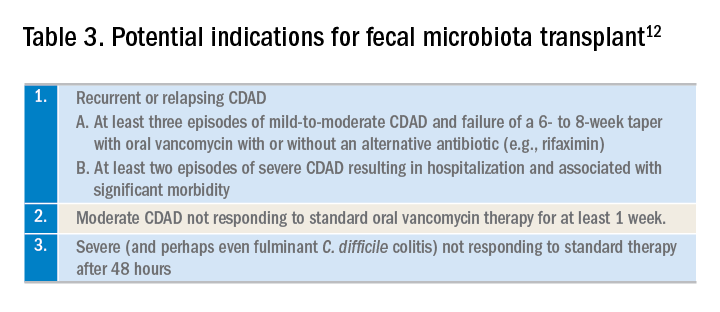

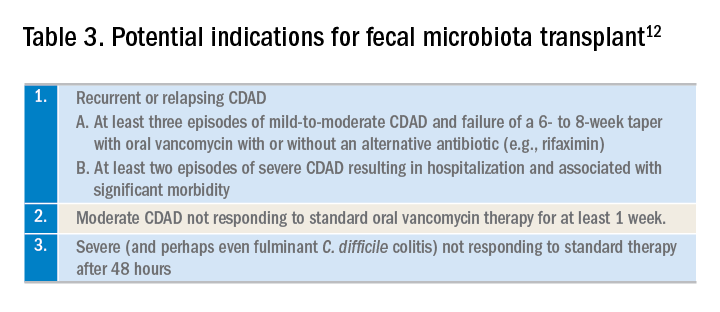

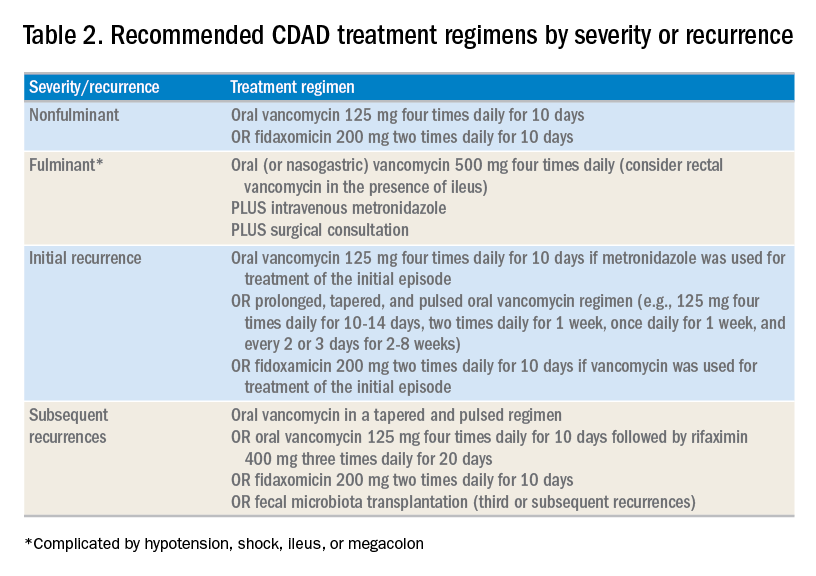

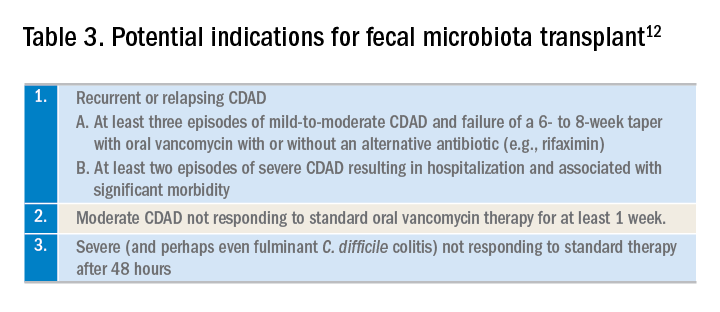

The treatment of CDAD involves a strategy of withdrawing the putative culprit antibiotic(s) whenever possible and initiating of antibiotics effective against C. difficile. Following the publication of two randomized controlled trials demonstrating the inferiority of metronidazole to vancomycin in clinical cure of CDAD,2,7 the IDSA/SHEA guidelines no longer recommend metronidazole for the treatment of CDAD. Instead, a 10-day course of oral vancomycin or fidaxomicin has been recommended.2 Although fidaxomicin is associated with lower rates of recurrence of CDAD, it is also substantially more expensive than oral vancomycin, with a 10-day course often costing over $3,000.8 When choosing oral vancomycin for completion of therapy following discharge, hospitalists should also consider whether the dispensing outpatient pharmacy can provide the less-expensive liquid preparation of vancomycin. In resource-poor settings, consideration can still be given to metronidazole, an inexpensive drug, compared with both oral vancomycin and fidaxomicin. “Test of cure” with follow-up stool testing is not recommended.

For patients who require systemic antibiotics that precipitated their CDAD, it is common practice to extend CDAD treatment by providing a “tail” coverage with an agent effective against CDAD for 7-10 days following the completion of the inciting antibiotic. A common clinical question relates to the management of patients with prior history of CDAD but in need of a new round of systemic antibiotic therapy. In these patients, concurrent prophylactic doses of oral vancomycin have been found to be effective in preventing recurrence.9 The IDSA/SHEA guidelines conclude that “it may be prudent to administer low doses of vancomycin or fidaxomicin (e.g., 125 mg or 200 mg, respectively, once daily) while systemic antibiotics are administered.”3