User login

Palliative care and hospital medicine partnerships in the pandemic

Patients dying without their loved ones, families forced to remotely decide goals of care without the physical presence or human connection of the care team, overworked staff physically isolated from their critically ill patients, and at-risk community members with uncertain and undocumented goals for care are among the universal challenges confronted by hospitals and hospitalists during this COVID-19 pandemic. Partnerships among hospital medicine (HM) and palliative care (PC) teams at Dell Medical School/Dell Seton Medical Center thrive on mutually shared core values of patient centered care – compassion, empathy, and humanity.

A key PC-HM collaboration was adapting our multidisciplinary huddle to focus on communication effectiveness and efficiency in the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Expanded interprofessional and cross-specialty collaboration promoted streamlined, succinct, and standardized communication with patients’ families while their loved ones were critically ill with COVID-19. The PC team attended daily MICU multidisciplinary huddles, attentive to both the medical and psychosocial updates for each patient. During huddles, residents or HM providers were asked to end their presentation with a clinical status “headline” and solicited feedback from the multidisciplinary team before messaging to the family. The PC team then communicated with families a succinct and cohesive medical update and continuously explored goals of care. This allowed the HM team, often overwhelmed with admissions, co-managing intensive care patients, and facilitating safe discharges, to focus on urgent issues while PC provided continuity and personalized support for patients and families. PC’s ability to synthesize and summarize clinical information from multiple teams and then provide cohesive updates in patient-friendly language modeled important communication skills for learners and simultaneously benefited HM providers.

Our chaplains, too, were central to facilitating timely, proactive conversations and documentation of Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA) for patients with COVID-19 admitted to our hospital. HM prioritized early admission conversations with patients to counsel them on severity of illness, prognosis based on risk factors, to elucidate wishes for intubation or resuscitation, and to capture their desired medical decision maker. HM was notified of all COVID and PUI admissions, allowing us to speak with even critically ill patients in the ER or ICU prior to intubation in order to quickly and accurately capture patients’ wishes for treatment and delegate decision makers. Our chaplains supported and supplemented these efforts by diligently and dutifully soliciting, hearing, and documenting patient MPOA delegates, with over 50% MPOA completion by 24 hours of hospitalization.

Another early PC-HM project, “Meet My Loved One,” was adapted from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Palliative and Comfort Unit. The absence of families visiting the ICU and sharing pictures, stories, anecdotes of our patients left a deeply felt, dehumanizing void in the halls and rooms of our hospital. To fill this space with life and humanity, furloughed medical students on their “transition of care” electives contacted family members of their “continuity” patients focusing primarily on those patients expected to have prolonged ICU or hospital stays and solicited personal, humanizing information about our patients. Questions included: “What is your loved one’s preferred name or nickname?” and “What are three things we should know to take better care of your loved one?” With family permission, we posted this information on the door outside the patient’s room. Nursing staff, in particular, appreciated getting to know their patients more personally and families appreciated the staff’s desire to know their loved one as an individual.

It is also important to acknowledge setbacks. Early efforts to engage technology proved more foe than friend. We continue to struggle with using our iPads for video visits. Most of our families prefer “WhatsApp” for video communication, which is not compatible with operating systems on early versions of the iPad, which were generously and widely donated by local school systems. Desperate to allow families to connect, many providers resorted to using personal devices to facilitate video visits and family meetings. And we discovered that many video visits caused more not less family angst, especially for critically ill patients. Families often required preparation and coaching on what to expect and how to interact with intubated, sedated, proned, and paralyzed loved ones.

Our hospital medicine and palliative care teams have an established strong partnership. The COVID-19 pandemic created novel communication challenges but our shared mission toward patient-centered care allowed us to effectively collaborate to bring the patients goals of care to the forefront aligning patients, families, physicians, nurses, and staff during the COVID-19 surge.

Dr. Johnston is associate professor at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas in Austin. She practices hospital medicine and inpatient palliative care at Dell Seton Medical Center. Dr. Cooremans is a resident physician at Dell Medical School. Dr. Salib is the internal medicine clerkship director and an associate professor at Dell Medical School. Dr. Nieto is an assistant professor and associate chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Patel is an assistant professor at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series written by members of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School, exploring lessons learned from the coronavirus pandemic and outlining an approach for creating COVID-19 Centers of Excellence. The article first appeared in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Patients dying without their loved ones, families forced to remotely decide goals of care without the physical presence or human connection of the care team, overworked staff physically isolated from their critically ill patients, and at-risk community members with uncertain and undocumented goals for care are among the universal challenges confronted by hospitals and hospitalists during this COVID-19 pandemic. Partnerships among hospital medicine (HM) and palliative care (PC) teams at Dell Medical School/Dell Seton Medical Center thrive on mutually shared core values of patient centered care – compassion, empathy, and humanity.

A key PC-HM collaboration was adapting our multidisciplinary huddle to focus on communication effectiveness and efficiency in the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Expanded interprofessional and cross-specialty collaboration promoted streamlined, succinct, and standardized communication with patients’ families while their loved ones were critically ill with COVID-19. The PC team attended daily MICU multidisciplinary huddles, attentive to both the medical and psychosocial updates for each patient. During huddles, residents or HM providers were asked to end their presentation with a clinical status “headline” and solicited feedback from the multidisciplinary team before messaging to the family. The PC team then communicated with families a succinct and cohesive medical update and continuously explored goals of care. This allowed the HM team, often overwhelmed with admissions, co-managing intensive care patients, and facilitating safe discharges, to focus on urgent issues while PC provided continuity and personalized support for patients and families. PC’s ability to synthesize and summarize clinical information from multiple teams and then provide cohesive updates in patient-friendly language modeled important communication skills for learners and simultaneously benefited HM providers.

Our chaplains, too, were central to facilitating timely, proactive conversations and documentation of Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA) for patients with COVID-19 admitted to our hospital. HM prioritized early admission conversations with patients to counsel them on severity of illness, prognosis based on risk factors, to elucidate wishes for intubation or resuscitation, and to capture their desired medical decision maker. HM was notified of all COVID and PUI admissions, allowing us to speak with even critically ill patients in the ER or ICU prior to intubation in order to quickly and accurately capture patients’ wishes for treatment and delegate decision makers. Our chaplains supported and supplemented these efforts by diligently and dutifully soliciting, hearing, and documenting patient MPOA delegates, with over 50% MPOA completion by 24 hours of hospitalization.

Another early PC-HM project, “Meet My Loved One,” was adapted from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Palliative and Comfort Unit. The absence of families visiting the ICU and sharing pictures, stories, anecdotes of our patients left a deeply felt, dehumanizing void in the halls and rooms of our hospital. To fill this space with life and humanity, furloughed medical students on their “transition of care” electives contacted family members of their “continuity” patients focusing primarily on those patients expected to have prolonged ICU or hospital stays and solicited personal, humanizing information about our patients. Questions included: “What is your loved one’s preferred name or nickname?” and “What are three things we should know to take better care of your loved one?” With family permission, we posted this information on the door outside the patient’s room. Nursing staff, in particular, appreciated getting to know their patients more personally and families appreciated the staff’s desire to know their loved one as an individual.

It is also important to acknowledge setbacks. Early efforts to engage technology proved more foe than friend. We continue to struggle with using our iPads for video visits. Most of our families prefer “WhatsApp” for video communication, which is not compatible with operating systems on early versions of the iPad, which were generously and widely donated by local school systems. Desperate to allow families to connect, many providers resorted to using personal devices to facilitate video visits and family meetings. And we discovered that many video visits caused more not less family angst, especially for critically ill patients. Families often required preparation and coaching on what to expect and how to interact with intubated, sedated, proned, and paralyzed loved ones.

Our hospital medicine and palliative care teams have an established strong partnership. The COVID-19 pandemic created novel communication challenges but our shared mission toward patient-centered care allowed us to effectively collaborate to bring the patients goals of care to the forefront aligning patients, families, physicians, nurses, and staff during the COVID-19 surge.

Dr. Johnston is associate professor at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas in Austin. She practices hospital medicine and inpatient palliative care at Dell Seton Medical Center. Dr. Cooremans is a resident physician at Dell Medical School. Dr. Salib is the internal medicine clerkship director and an associate professor at Dell Medical School. Dr. Nieto is an assistant professor and associate chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Patel is an assistant professor at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series written by members of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School, exploring lessons learned from the coronavirus pandemic and outlining an approach for creating COVID-19 Centers of Excellence. The article first appeared in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Patients dying without their loved ones, families forced to remotely decide goals of care without the physical presence or human connection of the care team, overworked staff physically isolated from their critically ill patients, and at-risk community members with uncertain and undocumented goals for care are among the universal challenges confronted by hospitals and hospitalists during this COVID-19 pandemic. Partnerships among hospital medicine (HM) and palliative care (PC) teams at Dell Medical School/Dell Seton Medical Center thrive on mutually shared core values of patient centered care – compassion, empathy, and humanity.

A key PC-HM collaboration was adapting our multidisciplinary huddle to focus on communication effectiveness and efficiency in the medical intensive care unit (MICU). Expanded interprofessional and cross-specialty collaboration promoted streamlined, succinct, and standardized communication with patients’ families while their loved ones were critically ill with COVID-19. The PC team attended daily MICU multidisciplinary huddles, attentive to both the medical and psychosocial updates for each patient. During huddles, residents or HM providers were asked to end their presentation with a clinical status “headline” and solicited feedback from the multidisciplinary team before messaging to the family. The PC team then communicated with families a succinct and cohesive medical update and continuously explored goals of care. This allowed the HM team, often overwhelmed with admissions, co-managing intensive care patients, and facilitating safe discharges, to focus on urgent issues while PC provided continuity and personalized support for patients and families. PC’s ability to synthesize and summarize clinical information from multiple teams and then provide cohesive updates in patient-friendly language modeled important communication skills for learners and simultaneously benefited HM providers.

Our chaplains, too, were central to facilitating timely, proactive conversations and documentation of Medical Power of Attorney (MPOA) for patients with COVID-19 admitted to our hospital. HM prioritized early admission conversations with patients to counsel them on severity of illness, prognosis based on risk factors, to elucidate wishes for intubation or resuscitation, and to capture their desired medical decision maker. HM was notified of all COVID and PUI admissions, allowing us to speak with even critically ill patients in the ER or ICU prior to intubation in order to quickly and accurately capture patients’ wishes for treatment and delegate decision makers. Our chaplains supported and supplemented these efforts by diligently and dutifully soliciting, hearing, and documenting patient MPOA delegates, with over 50% MPOA completion by 24 hours of hospitalization.

Another early PC-HM project, “Meet My Loved One,” was adapted from the University of Alabama at Birmingham Palliative and Comfort Unit. The absence of families visiting the ICU and sharing pictures, stories, anecdotes of our patients left a deeply felt, dehumanizing void in the halls and rooms of our hospital. To fill this space with life and humanity, furloughed medical students on their “transition of care” electives contacted family members of their “continuity” patients focusing primarily on those patients expected to have prolonged ICU or hospital stays and solicited personal, humanizing information about our patients. Questions included: “What is your loved one’s preferred name or nickname?” and “What are three things we should know to take better care of your loved one?” With family permission, we posted this information on the door outside the patient’s room. Nursing staff, in particular, appreciated getting to know their patients more personally and families appreciated the staff’s desire to know their loved one as an individual.

It is also important to acknowledge setbacks. Early efforts to engage technology proved more foe than friend. We continue to struggle with using our iPads for video visits. Most of our families prefer “WhatsApp” for video communication, which is not compatible with operating systems on early versions of the iPad, which were generously and widely donated by local school systems. Desperate to allow families to connect, many providers resorted to using personal devices to facilitate video visits and family meetings. And we discovered that many video visits caused more not less family angst, especially for critically ill patients. Families often required preparation and coaching on what to expect and how to interact with intubated, sedated, proned, and paralyzed loved ones.

Our hospital medicine and palliative care teams have an established strong partnership. The COVID-19 pandemic created novel communication challenges but our shared mission toward patient-centered care allowed us to effectively collaborate to bring the patients goals of care to the forefront aligning patients, families, physicians, nurses, and staff during the COVID-19 surge.

Dr. Johnston is associate professor at Dell Medical School at The University of Texas in Austin. She practices hospital medicine and inpatient palliative care at Dell Seton Medical Center. Dr. Cooremans is a resident physician at Dell Medical School. Dr. Salib is the internal medicine clerkship director and an associate professor at Dell Medical School. Dr. Nieto is an assistant professor and associate chief of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School. Dr. Patel is an assistant professor at Dell Medical School. This article is part of a series written by members of the Division of Hospital Medicine at Dell Medical School, exploring lessons learned from the coronavirus pandemic and outlining an approach for creating COVID-19 Centers of Excellence. The article first appeared in The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

CDC data strengthen link between obesity and severe COVID

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Officials have previously linked being overweight or obese to a greater risk for more severe COVID-19. A report today from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention adds numbers and some nuance to the association.

Data from nearly 150,000 U.S. adults hospitalized with COVID-19 nationwide indicate that risk for more severe disease outcomes increases along with body mass index (BMI). The risk of COVID-19–related hospitalization and death associated with obesity was particularly high among people younger than 65.

“As clinicians develop care plans for COVID-19 patients, they should consider the risk for severe outcomes in patients with higher BMIs, especially for those with severe obesity,” the researchers note. They add that their findings suggest “progressively intensive management of COVID-19 might be needed for patients with more severe obesity.”

People with COVID-19 close to the border between a healthy and overweight BMI – from 23.7 kg/m2 to 25.9 kg/m2 – had the lowest risks for adverse outcomes.

The study was published online today in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Greater need for critical care

The risk of ICU admission was particularly associated with severe obesity. For example, those with a BMI in the 40-44.9 kg/m2 category had a 6% increased risk, which jumped to 16% higher among those with a BMI of 45 or greater.

Compared to people with a healthy BMI, the need for invasive mechanical ventilation was 12% more likely among overweight adults with a BMI of 25-29.2. The risked jumped to 108% greater among the most obese people, those with a BMI of 45 or greater, lead CDC researcher Lyudmyla Kompaniyets, PhD, and colleagues reported.

Moreover, the risks for hospitalization and death increased in a dose-response relationship with obesity.

For example, risks of being hospitalized were 7% greater for adults with a BMI between 30 and 34.9 and climbed to 33% greater for those with a BMI of 45. Risks were calculated as adjusted relative risks compared with people with a healthy BMI between 18.5 and 24.9.

Interestingly, being underweight was associated with elevated risk for COVID-19 hospitalization as well. For example, people with a BMI of less than 18.5 had a 20% greater chance of admission vs. people in the healthy BMI range. Unknown underlying medical conditions or issues related to nutrition or immune function could be contributing factors, the researchers note.

Elevated risk of dying

The risk of death in adults with obesity ranged from 8% higher in the 30-34.9 range up to 61% greater for those with a BMI of 45.

Chronic inflammation or impaired lung function from excess weight are possible reasons that higher BMI imparts greater risk, the researchers note.

The CDC researchers evaluated 148,494 adults from 238 hospitals participating in PHD-SR database. Because the study was limited to people hospitalized with COVID-19, the findings may not apply to all adults with COVID-19.

Another potential limitation is that investigators were unable to calculate BMI for all patients in the database because about 28% of participating hospitals did not report height and weight.

The study authors had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

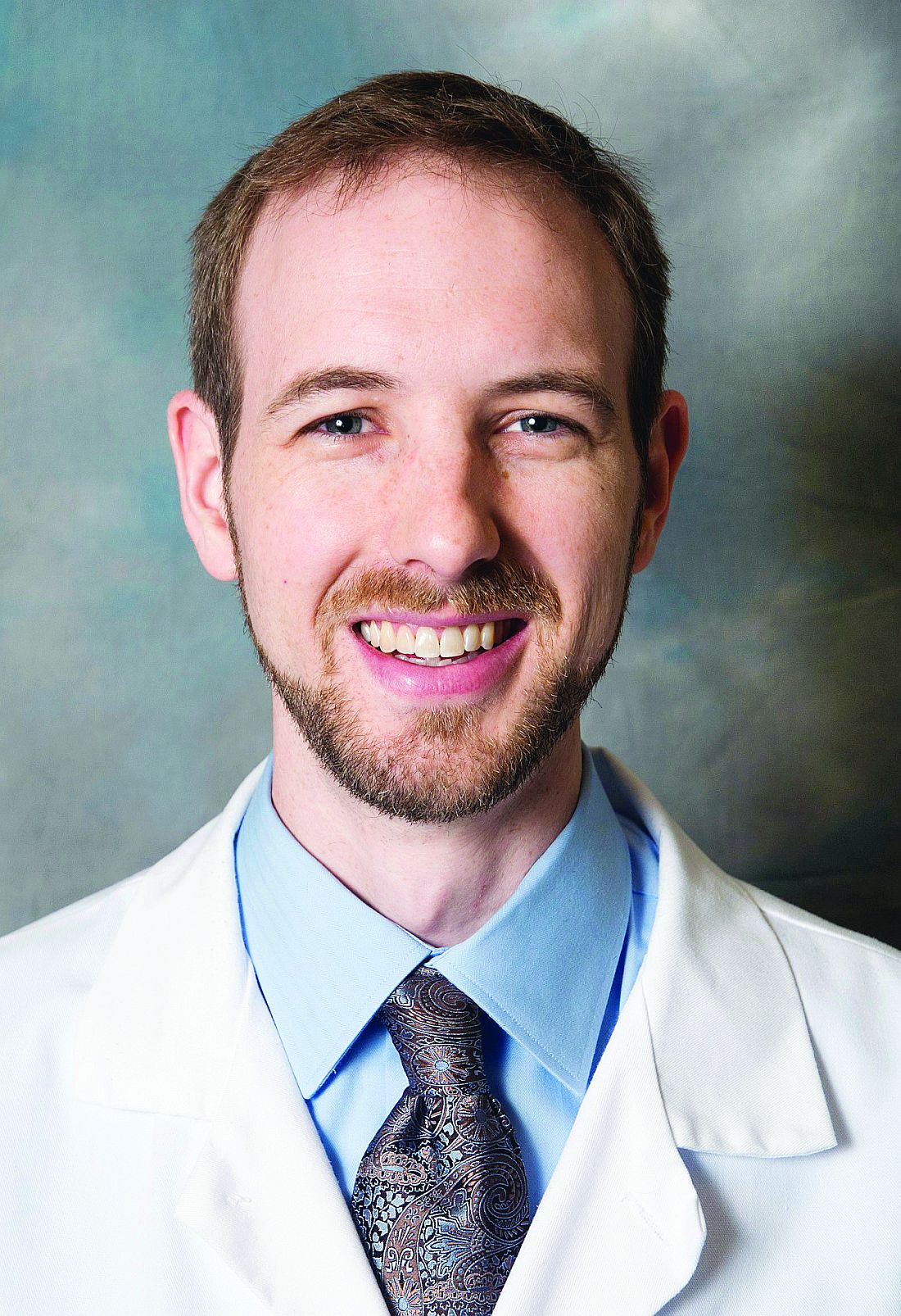

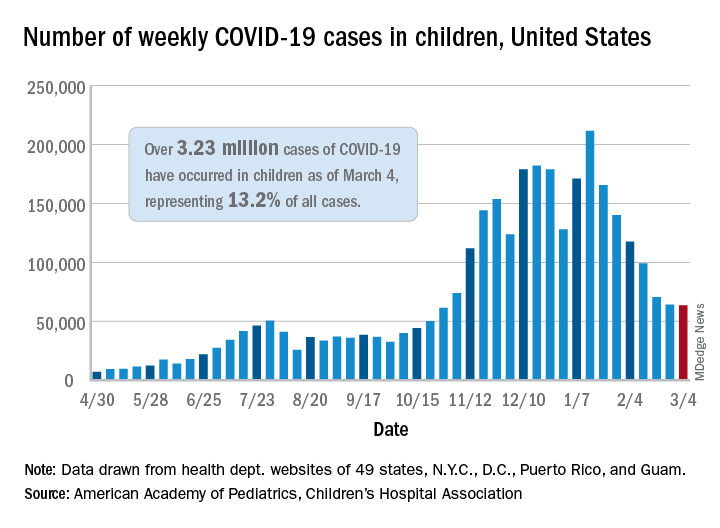

Decline in weekly child COVID-19 cases has almost stopped

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

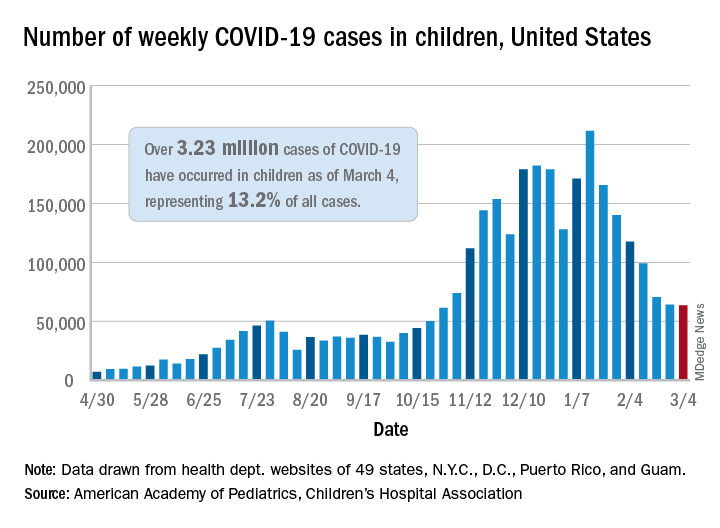

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

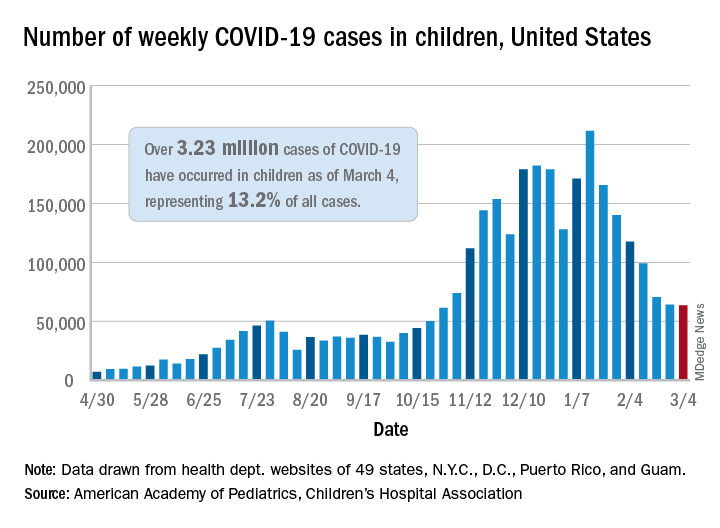

A third COVID-19 vaccine is now in circulation and states are starting to drop mask mandates, but the latest decline in weekly child cases barely registers as a decline, according to new data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

That’s only 702 cases – a drop of just 1.1% – the smallest by far since weekly cases peaked in mid-January, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID-19 report. Since that peak, the last 7 weeks of declines have looked like this: 21.7%, 15.3%, 16.2%, 15.7%, 28.7%, 9.0%, and 1.1%.

Meanwhile, children’s share of the COVID-19 burden increased to its highest point ever: 18.0% of all new cases occurred in children during the week ending March 4, climbing from 15.7% the week before and eclipsing the previous high of 16.9%. Cumulatively, the 3.23 million cases in children represent 13.2% of all COVID-19 cases reported in 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

At the state level, the new leader in cumulative share of cases is Vermont at 19.4%, which just edged past Wyoming’s 19.3% as of the week ending March 4. The other states above 18% are Alaska (19.2%) and South Carolina (18.2%). The lowest rates can be found in Florida (8.1%), New Jersey (10.2%), Iowa (10.4%), and Utah (10.5%), the AAP and CHA said.

The overall rate of COVID-19 cases nationwide was 4,294 cases per 100,000 children as of March 4, up from 4,209 per 100,000 the week before. That measure had doubled between Dec. 3 (1,941 per 100,000) and Feb. 4 (3,899) but has only risen about 10% in the last month, the AAP/CHA data show.

Perhaps the most surprising news of the week involves the number of COVID-19 deaths in children, which went from 256 the previous week to 253 after Ohio made a downward revision of its mortality data. So far, children represent just 0.06% of all coronavirus-related deaths, a figure that has held steady since last summer in the 43 states (along with New York City and Guam) that are reporting mortality data by age, the AAP and CHA said.

Call to action on obesity amid COVID-19 pandemic

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide from COVID-19 could have been avoided if obesity rates were lower, a new report says.

An analysis by the World Obesity Federation found that of the 2.5 million COVID-19 deaths reported by the end of February 2021, almost 90% (2.2 million) were in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

The report, released to coincide with World Obesity Day, calls for obesity to be recognized as a disease in its own right around the world, and for people with obesity to be included in priority lists for COVID-19 testing and vaccination.

“Overweight is a highly significant predictor of developing complications from COVID-19, including the need for hospitalization, for intensive care and for mechanical ventilation,” the WOF notes in the report.

It adds that in countries where less than half the adult population is classified as overweight (body mass index > 25 mg/kg2), for example, Vietnam, the likelihood of death from COVID-19 is a small fraction – around one-tenth – of the level seen in countries where more than half the population is classified as overweight.

And while it acknowledges that figures for COVID-19 deaths are affected by the age structure of national populations and a country’s relative wealth and reporting capacity, “our findings appear to be independent of these contributory factors. Furthermore, other studies have found that overweight remains a highly significant predictor of the need for COVID-19 health care after accounting for these other influences.”

As an example, based on the U.K. experience, where an estimated 36% of COVID-19 hospitalizations have been attributed to lack of physical activity and excess body weight, it can be suggested that up to a third of the costs – between $6 trillion and $7 trillion over the longer period – might be attributable to these predisposing risks.

The report said the prevalence of obesity in the United Kingdom is expected to rise from 27.8% in 2016 to more than 35% by 2025.

Rachel Batterham, lead adviser on obesity at the Royal College of Physicians, commented: “The link between high levels of obesity and deaths from COVID-19 in the U.K. is indisputable, as is the urgent need to address the factors that lead so many people to be living with obesity.

“With 30% of COVID-19 hospitalizations in the U.K. directly attributed to overweight and obesity, and three-quarters of all critically ill patients having overweight or obesity, the human and financial costs are high.”

Window of opportunity to prioritize obesity as a disease

WOF says that evolving evidence on the close association between COVID-19 and underlying obesity “provides a new urgency … for political and collective action.”

“Obesity is a disease that does not receive prioritization commensurate with its prevalence and impact, which is rising fastest in emerging economies. It is a gateway to many other noncommunicable diseases and mental-health illness and is now a major factor in COVID-19 complications and mortality.”

The WOF also shows that COVID-19 is not a special case, noting that several other respiratory viruses lead to more severe consequences in people living with excess bodyweight, giving good reasons to expect the next pandemic to have similar effects. “For these reasons we need to recognize overweight as a major risk factor for infectious diseases including respiratory viruses.”

“To prevent pandemic health crises in future requires action now: we call on all readers to support the World Obesity Federation’s call for stronger, more resilient economies that prioritize investment in people’s health.”

There is, it stresses, “a window of opportunity to advocate for, fund and implement these actions in all countries to ensure better, more resilient and sustainable health for all, “now and in our postCOVID-19 future.”

It proposes a ROOTS approach:

- Recognize that obesity is a disease in its own right.

- Obesity monitoring and surveillance must be enhanced.

- Obesity prevention strategies must be developed.

- Treatment of obesity.

- Systems-based approaches should be applied.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygeia and Panacea and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant.

On my desk sits a bust of Hygeia, a mask from Venice, next to a small sculpture and a figurine of the plague doctor. Nearby, there is a Klimt closeup of Hygeia, a postcard portraying Asclepius, St. Sebastian paintings, and quotes from Maimonides. They whisper secrets and nod to the challenges of the past. These medical specters, ancient voices of the past, keep me grounded. They speak, listen, and elevate me, too. They bring life into my otherwise quiet room.

We all began our careers swearing to Apollo, Asclepius, Hygeia, and Panacea when we recited the Hippocratic Oath. I call upon them, and other gods and totems, and saints and ancient healers, now more than ever. As an atheist, I don’t appeal to them as prayers, but as Hippocrates intended. I look to their supernatural healing powers as a source of strength and as revealers of the natural and observable phenomena.

Apollo was one of the Twelve Olympians, a God of medicine, father of Asclepius. He was a healer, though his arrows also bore the plagues of the Gods.

For centuries, Apollo was found floating above the marble dissection table in the Bologna anatomical theater, guiding students who dove into the secrets of the human body.

Asclepius, son of Apollo, was hailed as a god of medicine. He healed many from plagues at his temples throughout the Ancient Greek and Roman empires. He was mentored in the healing arts by the centaur, Chiron. His many daughters and sons represent various aspects of medicine including cures, healing, recovery, sanitation, and beauty. To Asclepius, temples were places of healing, an ancient ancestor to modern hospitals.

Two of his daughters, Panacea and Hygeia, gave us the healing words of panacea and hygiene. Today, these acts of hygiene, handwashing, mask-wearing, and sanitation are discussed across the world louder than ever. While we’re all wishing for a panacea, we know it will take all the attributes of medicine to get us through this pandemic.

Hospitalists are part of the frontline teams facing this pandemic head-on. Gowning up for MRSA isolation seems quaint nowadays.

My attendings spoke of their fears, up against the unknown while on service in the 1980s, when HIV appeared. 2014 brought the Ebola biocontainment units. Now, this generation works daily against a modern plague, where every day is a risk of exposure. When every patient is in isolation, the garb begins to reflect the PPE that emerged during a 17th-century plague epidemics, the plague doctor outfit.

Godfather II fans recall the famous portrayal of the August 16th festival to San Rocco play out in the streets of New York. For those stricken with COVID-19 and recovered, you emulate San Rocco, in your continued return to service.

The Scuola Grande di San Rocco, in Venice, is the epitome of healing and greatness in one building. Tintoretto, the great Venetian painter, assembled the story of healing through art and portraits of San Rocco. The scuola, a confraternity, was a community of healers, gathered in one place to look after the less fortunate.

Hospitalists march into the hospital risking their lives. We always wear PPE for MRSA, ESBL, or C. diff. And enter reverse isolation rooms wearing N95s for possible TB cases. But those don’t elevate to the volume, to the same fear, as gowning up for COVID-19.

Hospitalists, frontline health care workers, embody the story of San Sebastian, another plague saint who absorbed the arrows, the symbolic plagues, onto his own shoulders so no one else had to bear them. San Sebastian was a Christian persecuted by a Roman emperor once his beliefs were discovered. He is often laden with arrows in spots where buboes would have appeared: the armpits and the groin. His sacrifice for others’ recovery became a symbol of absorbing the plague, the wounds, and the impact of the arrows.

This sacrifice epitomizes the daily work the frontline nurses, ER docs, intensivists, hospitalists, and the entire hospital staff perform daily, bearing the slung arrows of coronavirus.

One of the images I think of frequently during this time lies atop Castel San Angelo in Rome. Built in 161 AD, it has served as a mausoleum, prison, papal residence, and is currently a museum. Atop San’Angelo stands St. Michael, the destroyer of the dragon. He is sheathing his sword in representation of the end of the plague in 590.

The arrows flow, yet the sword will be sheathed. Evil will be halted. The stories of these ancient totems and strength can give us strength as they remind us of the work that was done for centuries: pestilence, famine, war. The great killers never go away completely.

Fast forward to today

These medical specters serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so inspiring: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories, we spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day. These specters encourage us to defeat any and all of the scourges that come our way.

I hear and read stories about the frontline heroes, the vaccine makers, the PPE creators, the health care workers, grocery store clerks, and teachers. I’m honored to hear of these stories and your sacrifices. I’m inspired to continue upholding your essence, your fight, and your stories. In keeping with ancient empire metaphors, you are taking the slings of the diseased arrows flying to our brethren as you try to keep yourself and others safe.

The sheathing of this sword will come. These arrows will be silenced. But until then, I lean on these pictures, these stories, and these saints, to give us all the strength to wake up each morning and continue healing.

They serve as reminders of what makes the field of medicine so great: the selfless acts, the fortitude of spirit, the healers, the long history, and the shoulders of giants we stand upon. From these stories spring the healing waters we bathe in to give us the courage to wake up and care for our patients each day and defeat any and all scourges that come our way.

So, who do you call in those late, quiet hours, when all seems lost?

Dr. Messler is the executive director, quality initiatives at Glytec and works as a hospitalist at Morton Plant Hospitalist group in Clearwater, Fla. This essay appeared initially on The Hospital Leader, the official blog of SHM.

Potential COVID-19 variant surge looms over U.S.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Another coronavirus surge may be on the way in the United States as daily COVID-19 cases continue to plateau around 60,000, states begin to lift restrictions, and people embark on spring break trips this week, according to CNN.

Outbreaks will likely stem from the B.1.1.7 variant, which was first identified in the United Kingdom, and gain momentum during the next 6-14 weeks.

“Four weeks ago, the B.1.1.7 variant made up about 1%-4% of the virus that we were seeing in communities across the country. Today it’s up to 30%-40%,” Michael Osterholm, PhD, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, told NBC’s Meet the Press on March 7.

Dr. Osterholm compared the current situation with the “eye of the hurricane,” where the skies appear clear but more storms are on the way. Across Europe, 27 countries are seeing significant B.1.1.7 case increases, and 10 are getting hit hard, he said.

“What we’ve seen in Europe, when we hit that 50% mark, you see cases surge,” he said. “So right now, we do have to keep America as safe as we can from this virus by not letting up on any of the public health measures we’ve taken.”

In January, the CDC warned that B.1.1.7 variant cases would increase in 2021 and become the dominant variant in the country by this month. The United States has now reported more than 3,000 cases across 46 states, according to the latest CDC tally updated on March 7. More than 600 cases have been found in Florida, followed by more than 400 in Michigan.

The CDC has said the tally doesn’t represent the total number of B.1.1.7 cases in the United States, only the ones that have been identified by analyzing samples through genomic sequencing.

“Where it has hit in the U.K. and now elsewhere in Europe, it has been catastrophic,” Celine Gounder, MD, an infectious disease specialist with New York University Langone Health, told CNN on March 7.

The variant is more transmissible than the original novel coronavirus, and the cases in the United States are “increasing exponentially,” she said.

“It has driven up rates of hospitalizations and deaths and it’s very difficult to control,” Dr. Gounder said.

Vaccination numbers aren’t yet high enough to stop the predicted surge, she added. The United States has shipped more than 116 million vaccine doses, according to the latest CDC update on March 7. Nearly 59 million people have received at least one dose, and 30.6 million people have received two vaccine doses. About 9% of the U.S. population has been fully vaccinated.

States shouldn’t ease restrictions until the vaccination numbers are much higher and daily COVID-19 cases fall below 10,000 – and maybe “considerably less than that,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNN on March 4.

Several states have already begun to lift COVID-19 safety protocols, with Texas and Mississippi removing mask mandates last week. Businesses in Texas will be able to reopen at full capacity on March 10. For now, public health officials are urging Americans to continue to wear masks, avoid crowds, and follow social distancing guidelines as vaccines roll out across the country.

“This is sort of like we’ve been running this really long marathon, and we’re 100 yards from the finish line and we sit down and we give up,” Dr. Gounder told CNN on Sunday. ‘We’re almost there, we just need to give ourselves a bit more time to get a larger proportion of the population covered with vaccines.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

DOACs offered after heart valve surgery despite absence of data

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are used in about 1% of patients undergoing surgical mechanical aortic and mitral valve replacement, but in up to 6% of surgical bioprosthetic valve replacements, according to registry data presented at CRT 2021.

In an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) registry during 2014-2017, DOAC use increased steadily among those undergoing surgical bioprosthetic valve replacement, reaching a number that is potentially clinically significant, according to Ankur Kalra, MD, an interventional cardiologist at Akron General Hospital who has an academic appointment at the Cleveland Clinic.

There was no increase in the use of DOACs observed among patients undergoing mechanical valve replacement, “but even if the number is 1%, they should probably not be used at all until we accrue more data,” Dr. Kalra said.

DOACs discouraged in patients with mechanical or bioprosthetic valves

In Food and Drug Administration labeling, DOACs are contraindicated or not recommended. This can be traced to the randomized RE-ALIGN trial, which was stopped prematurely due to evidence of harm from a DOAC, according to Dr. Kalra.