User login

MIS-C follow-up proves challenging across pediatric hospitals

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

The discovery of any novel disease or condition means a steep learning curve as physicians must develop protocols for diagnosis, management, and follow-up on the fly in the midst of admitting and treating patients. Medical society task forces and committees often release interim guidance during the learning process, but each institution ultimately has to determine what works for them based on their resources, clinical experience, and patient population.

But when the novel condition demands the involvement of multiple different specialties, the challenge of management grows even more complex – as does follow-up after patients are discharged. Such has been the story with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), a complication of COVID-19 that shares some features with Kawasaki disease.

The similarities to Kawasaki provided physicians a place to start in developing appropriate treatment regimens and involved a similar interdisciplinary team from, at the least, cardiology and rheumatology, plus infectious disease since MIS-C results from COVID-19.

“It literally has it in the name – multisystem essentially hints that there are multiple specialties involved, multiple hands in the pot trying to manage the kids, and so each specialty has their own kind of unique role in the patient’s care even on the outpatient side,” said Samina S. Bhumbra, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at Riley Hospital for Children and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University in Indianapolis. “This isn’t a disease that falls under one specialty.”

By July, the American College of Rheumatology had issued interim clinical guidance for management that most children’s hospitals have followed or slightly adapted. But ACR guidelines could not address how each institution should handle outpatient follow-up visits, especially since those visits required, again, at least cardiology and rheumatology if not infectious disease or other specialties as well.

“When their kids are admitted to the hospital, to be told at discharge you have to be followed up by all these specialists is a lot to handle,” Dr. Bhumbra said. But just as it’s difficult for parents to deal with the need to see several different doctors after discharge, it can be difficult at some institutions for physicians to design a follow-up schedule that can accommodate families, especially families who live far from the hospital in the first place.

“Some of our follow-up is disjointed because all of our clinics had never been on the same day just because of staff availability,” Dr. Bhumbra said. “But it can be a 2- to 3-hour drive for some of our patients, depending on how far they’re coming.”

Many of them can’t make that drive more than once in the same month, much less the same week.

“If you have multiple visits, it makes it more likely that they’re not showing up,” said Ryan M. Serrano, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Riley and assistant professor of pediatrics at Indiana University. Riley used telehealth when possible, especially if families could get labs done near home. But pediatric echocardiograms require technicians who have experience with children, so families need to come to the hospital.

Children’s hospitals have therefore had to adapt scheduling strategies or develop pediatric specialty clinics to coordinate across the multiple departments and accommodate a complex follow-up regimen that is still evolving as physicians learn more about MIS-C.

Determining a follow-up regimen

Even before determining how to coordinate appointments, hospitals had to decide what follow-up itself should be.

“How long do we follow these patients and how often do we follow them?” said Melissa S. Oliver, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University.

“We’re seeing that a lot of our patients rapidly respond when they get appropriate therapy, but we don’t know about long-term outcomes yet. We’re all still learning.”

At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, infectious disease follows up 4-6 weeks post discharge. The cardiology division came up with a follow-up plan that has evolved over time, said Matthew Elias, MD, an attending cardiologist at CHOP’s Cardiac Center and clinical assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Patients get an EKG and echocardiogram at 2 weeks and, if their condition is stable, 6 weeks after discharge. After that, it depends on the patient’s clinical situation. Patients with moderately diminished left ventricular systolic function are recommended to get an MRI scan 3 months after discharge and, if old enough, exercise stress tests. Otherwise, they are seen at 6 months, but that appointment is optional for those whose prior echos have consistently been normal.

Other institutions, including Riley, are following a similar schedule of 2-week, 6-week, and 6-month postdischarge follow-ups, and most plan to do a 1-year follow-up as well, although that 1-year mark hasn’t arrived yet for most. Most do rheumatology labs at the 2-week appointment and use that to determine steroids management and whether labs are needed at the 6-week appointment. If labs have normalized, they aren’t done at 6 months. Small variations in follow-up management exist across institutions, but all are remaining open to changes. Riley, for example, is considering MRI screening for ongoing cardiac inflammation at 6 months to a year for all patients, Dr. Serrano said.

The dedicated clinic model

The two challenges Riley needed to address were the lack of a clear consensus on what MIS-C follow-up should look like and the need for continuity of care, Dr. Serrano said.

Regular discussion in departmental meetings at Riley “progressed from how do we take care of them and what treatments do we give them to how do we follow them and manage them in outpatient,” Dr. Oliver said. In the inpatient setting, they had an interdisciplinary team, but how could they maintain that for outpatients without overwhelming the families?

“I think the main challenge is for the families to identify who is leading the care for them,” said Martha M. Rodriguez, MD, a rheumatologist at Riley and assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University. That sometimes led to families picking which follow-up appointments they would attend and which they would skip if they could not make them all – and sometimes they skipped the more important ones. “They would go to the appointment with me and then miss the cardiology appointments and the echocardiogram, which was more important to follow any abnormalities in the heart,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

After trying to coordinate separate follow-up appointments for months, Riley ultimately decided to form a dedicated clinic for MIS-C follow-up – a “one-stop shop” single appointment at each follow-up, Dr. Bhumbra said, that covers labs, EKG, echocardiogram, and any other necessary tests.

“Our goal with the clinic is to make life easier for the families and to be able to coordinate the appointments,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “They will be able to see the three of us, and it would be easier for us to communicate with each other about their plan.”

The clinic began Feb. 11 and occurs twice a month. Though it’s just begun, Dr. Oliver said the first clinic went well, and it’s helping them figure out the role each specialty needs to play in follow-up care.

“For us with rheumatology, after lab values have returned to normal and they’re off steroids, sometimes we think there isn’t much more we can contribute to,” she said. And then there are the patients who didn’t see any rheumatologists while inpatients.

“That’s what we’re trying to figure out as well,” Dr. Oliver said. “Should we be seeing every single kid regardless of whether we were involved in their inpatient [stay] or only seeing the ones we’ve seen?” She expects the coming months will help them work that out.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston also uses a dedicated clinic, but they set it up before the first MIS-C patient came through the doors, said Sara Kristen Sexson Tejtel, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Texas Children’s. The hospital already has other types of multidisciplinary clinics, and they anticipated the challenge of getting families to come to too many appointments in a short period of time.

“Getting someone to come back once is hard enough,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Getting them to come back twice is impossible.”

Infectious disease is less involved at Texas Children’s, so it’s primarily Dr. Sexson Tejtel and her rheumatologist colleague who see the patients. They hold the clinic once a week, twice if needed.

“It does make the appointment a little longer, but I think the patients appreciate that everything can be addressed with that one visit,” Dr. Sexson Tejtel said. “Being in the hospital as long as some of these kids are is so hard, so making any of that easy as possible is so helpful.” A single appointment also allows the doctors to work together on what labs are needed so that children don’t need multiple labs drawn.

At the appointment, she and the rheumatologist enter the patient’s room and take the patient’s history together.

“It’s nice because it makes the family not to have to repeat things and tell the same story over and over,” she said. “Sometimes I ask questions that then the rheumatologist jumps off of, and then sometimes he’ll ask questions, and I’ll think, ‘Ooh, I’ll ask more questions about that.’ ”

In fact, this team approach at all clinics has made her a more thoughtful, well-rounded physician, she said.

“I have learned so much going to all of my multidisciplinary clinics, and I think I’m able to better care for my patients because I’m not just thinking about it from a cardiac perspective,” she said. “It takes some work, but it’s not hard and I think it is beneficial both for the patient and for the physician. This team approach is definitely where we’re trying to live right now.”

Separate but coordinated appointments

A dedicated clinic isn’t the answer for all institutions, however. At Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, the size of the networks and all its satellites made a one-stop shop impractical.

“We talked about a consolidated clinic early on, when MIS-C was first emerging and all our groups were collaborating and coming up with our inpatient and outpatient care pathways,” said Sanjeev K. Swami, MD, an infectious disease pediatrician at CHOP and associate professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania. But timing varies on when each specialist wants to see the families return, and existing clinic schedules and locations varied too much.

So CHOP coordinates appointments individually for each patient, depending on where the patient lives and sometimes stacking them on the same day when possible. Sometimes infectious disease or rheumatology use telehealth, and CHOP, like the other hospitals, prioritizes cardiology, especially for the patients who had cardiac abnormalities in the hospital, Dr. Swami said.

“All three of our groups try to be as flexible as possible. We’ve had a really good collaboration between our groups,” he said, and spreading out follow-up allows specialists to ask about concerns raised at previous appointments, ensuring stronger continuity of care.

“We can make sure things are getting followed up on,” Dr. Swami said. “I think that has been beneficial to make sure things aren’t falling through the cracks.”

CHOP cardiologist Dr. Elias said that ongoing communication, among providers and with families, has been absolutely crucial.

“Everyone’s been talking so frequently about our MIS-C patients while inpatient that by the time they’re an outpatient, it seems to work smoothly, where families are hearing similar items but with a different flair, one from infectious, one from rheumatology, and one from cardiology,” he said.

Children’s Mercy in Kansas City, Mo., also has multiple satellite clinics and follows a model similar to that of CHOP. They discussed having a dedicated multidisciplinary team for each MIS-C patient, but even the logistics of that were difficult, said Emily J. Fox, MD, a rheumatologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Instead, Children’s Mercy tries to coordinate follow-up appointments to be on the same day and often use telehealth for the rheumatology appointments. Families that live closer to the hospital’s location in Joplin, Mo., go in for their cardiology appointment there, and then Dr. Fox conducts a telehealth appointment with the help of nurses in Joplin.

“We really do try hard, especially since these kids are in the hospital for a long time, to make the coordination as easy as possible,” Dr. Fox said. “This was all was very new, especially in the beginning, but I think at least our group is getting a little bit more comfortable in managing these patients.”

Looking ahead

The biggest question that still looms is what happens to these children, if anything, down the line.

“What was unique about this was this was a new disease we were all learning about together with no baseline,” Dr. Swami said. “None of us had ever seen this condition before.”

So far, the prognosis for the vast majority of children is good. “Most of these kids survive, most of them are doing well, and they almost all recover,” Dr. Serrano said. Labs tend to normalize by 6 weeks post discharge, if not much earlier, and not much cardiac involvement is showing up at later follow-ups. But not even a year has passed, so there’s plenty to learn. “We don’t know if there’s long-term risk. I would not be surprised if 20 years down the road we’re finding out things about this that we had no idea” about, Dr. Serrano said. “Everybody wants answers, and nobody has any, and the answers we have may end up being wrong. That’s how it goes when you’re dealing with something you’ve never seen.”

Research underway will ideally begin providing those answers soon. CHOP is a participating site in an NIH-NHLBI–sponsored study, called COVID MUSIC, that is tracking long-term outcomes for MIS-C at 30 centers across the United States and Canada for 5 years.

“That will really definitely be helpful in answering some of the questions about long-term outcomes,” Dr. Elias said. “We hope this is going to be a transient issue and that patients won’t have any long-term manifestations, but we don’t know that yet.”

Meanwhile, one benefit that has come out of the pandemic is strong collaboration, Dr. Bhumbra said.

“The biggest thing we’re all eagerly waiting and hoping for is standard guidelines on how best to follow-up on these kids, but I know that’s a ways away,” Dr. Bhumbra said. So for now, each institution is doing what it can to develop protocols that they feel best serve the patients’ needs, such as Riley’s new dedicated MIS-C clinic. “It takes a village to take care of these kids, and MIS-C has proven that having a clinic with all three specialties at one clinic is going to be great for the families.”

Dr. Fox serves on a committee for Pfizer unrelated to MIS-C. No other doctors interviewed for this story had relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Heart failure redefined with new classifications, staging

The terminology and classification scheme for heart failure (HF) is changing in ways that experts hope will directly impact patient outcomes.

In a new consensus statement, a multisociety group of experts proposed a new universal definition of heart failure and made substantial revisions to the way in which the disease is staged and classified.

The authors of the statement, led by writing committee chair and immediate past president of the Heart Failure Society of America Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, hope their efforts will go far to improve standardization of terminology, but more importantly will facilitate better management of the disease in ways that keep pace with current knowledge and advances in the field.

“There is a great need for reframing and standardizing the terminology across societies and different stakeholders, and importantly for patients because a lot of the terminology we were using was understood by academicians, but were not being translated in important ways to ensure patients are being appropriately treated,” said Dr. Bozkurt, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The consensus statement was a group effort led by the HFSA, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Japanese Heart Failure Society, with endorsements from the Canadian Heart Failure Society, the Heart Failure Association of India, the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the Chinese Heart Failure Association.

The article was published March 1 in the Journal of Cardiac Failure and the European Journal of Heart Failure, authored by a writing committee of 38 individuals with domain expertise in HF, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular disease.

“This is a very thorough and very carefully written document that I think will be helpful for clinicians because they’ve tapped into important changes in the field that have occurred over the past 10 years and that now allow us to do more for patients than we could before,” Eugene Braunwald, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Braunwald and Elliott M. Antman, MD, both from TIMI Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, wrote an editorial that accompanied the European Journal of Heart Failure article.

A new universal definition

“[Heart failure] is a clinical syndrome with symptoms and or signs caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and/or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion.”

This proposed definition, said the authors, is designed to be contemporary and simple “but conceptually comprehensive, with near universal applicability, prognostic and therapeutic viability, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity.”

Both left and right HF qualifies under this definition, said the authors, but conditions that result in marked volume overload, such as chronic kidney disease, which may present with signs and symptoms of HF, do not.

“Although some of these patients may have concomitant HF, these patients have a primary abnormality that may require a specific treatment beyond that for HF,” said the consensus statement authors.

For his part, Douglas L. Mann, MD, is happy to see what he considers a more accurate and practical definition for heart failure.

“We’ve had some wacky definitions in heart failure that haven’t made sense for 30 years, the principal of which is the definition of heart failure that says it’s the inability of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body,” Dr. Mann, of Washington University, St. Louis, said in an interview.

“I think this description was developed thinking about people with end-stage heart failure, but it makes no sense in clinical practice. Does it make sense to say about someone with New York Heart Association class I heart failure that their heart can’t meet the metabolic demands of the body?” said Dr. Mann, who was not involved with the writing of the consensus statement.

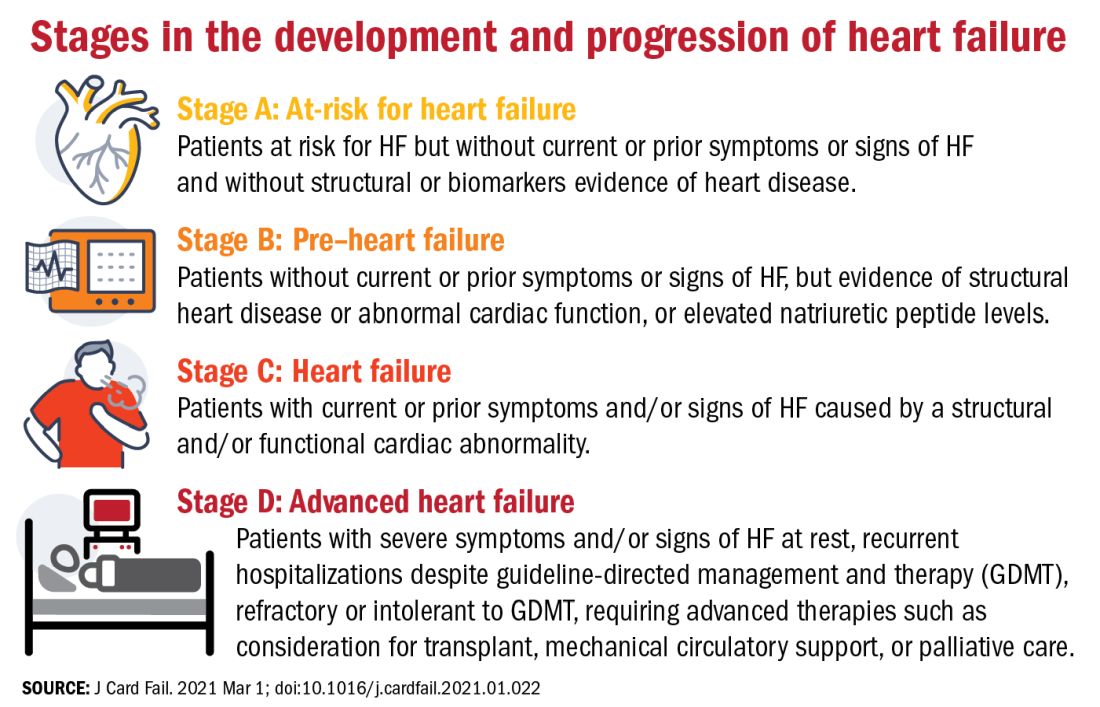

Proposed revised stages of the HF continuum

Overall, minimal changes have been made to the HF stages, with tweaks intended to enhance understanding and address the evolving role of biomarkers.

The authors proposed an approach to staging of HF:

- At-risk for HF (stage A), for patients at risk for HF but without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF and without structural or biomarkers evidence of heart disease.

- Pre-HF (stage B), for patients without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF, but evidence of structural heart disease or abnormal cardiac function, or elevated natriuretic peptide levels.

- HF (stage C), for patients with current or prior symptoms and/or signs of HF caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality.

- Advanced HF (stage D), for patients with severe symptoms and/or signs of HF at rest, recurrent hospitalizations despite guideline-directed management and therapy (GDMT), refractory or intolerant to GDMT, requiring advanced therapies such as consideration for transplant, mechanical circulatory support, or palliative care.

One notable change to the staging scheme is stage B, which the authors have reframed as “pre–heart failure.”

“Pre-cancer is a term widely understood and considered actionable and we wanted to tap into this successful messaging and embrace the pre–heart failure concept as something that is treatable and preventable,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

“We want patients and clinicians to understand that there are things we can do to prevent heart failure, strategies we didn’t have before, like SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes at risk for HF,” she added.

The revision also avoids the stigma of HF before the symptoms are manifest.

“Not calling it stage A and stage B heart failure you might say is semantics, but it’s important semantics,” said Dr. Braunwald. “When you’re talking to a patient or a relative and tell them they have stage A heart failure, it’s scares them unnecessarily. They don’t hear the stage A or B part, just the heart failure part.”

New classifications according to LVEF

And finally, in what some might consider the most obviously needed modification, the document proposes a new and revised classification of HF according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Most agree on how to classify heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but although the middle range has long been understood to be a clinically relevant, it has no proper name or clear delineation.

“For standardization across practice guidelines, to recognize clinical trajectories in HF, and to facilitate the recognition of different heart failure entities in a sensitive and specific manner that can guide therapy, we want to formalize the heart failure categories according to ejection fraction,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

To this end, the authors propose the following four classifications of EF:

- HF with reduced EF (HFrEF): LVEF of up to 40%.

- HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF): LVEF of 41-49%.

- HF with preserved EF (HFpEF)HF with an LVEF of at least 50%.

- HF with improved EF (HFimpEF): HF with a baseline LVEF of 40% or less, an increase of at least 10 points from baseline LVEF, and a second measurement of LVEF of greater than 40%.

HFmrEF is usually a transition period, noted Dr. Bozkurt. “Patients with HF in this range may represent a population whose EF is likely to change, either increase or decrease over time and it’s important to be cognizant of that trajectory. Understanding where your patient is headed is crucial for prognosis and optimization of guideline-directed treatment,” she said.

Improved, not recovered, HF

The last classification of heart failure with improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF) represents an important change to the current classification scheme.

“We want to clarify what terms to use but also which not to use. For example, we don’t want people to use recovered heart failure or heart failure in remission, partly because we don’t want the medication to be stopped. We don’t want to give the false message that there has been full recovery,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

As seen in the TRED-HF trial, guideline-directed medical therapy should be continued in patients with HF with improved EF regardless of whether it has improved to a normal range of above 50% in subsequent measurements.

“This is a distinct group of people, and for a while the guidelines were lumping them in with HFpEF, which I think is totally wrong,” said Dr. Mann.

“I think it’s very important that we emphasize heart failure as a continuum, rather than a one-way street of [inevitable] progression. Because we do see improvements in ejection fraction and we do see that we can prevent heart failure if we do the right things, and this should be reflected in the terminology we use,” he added.

Dr. Bozkurt stressed that HFimpEF only applies if the EF improves to above 40%. A move from an EF of 10%-20% would still see the patient classified as having HFrEF, but a patient whose EF improved from, say, 30% to 45% would be classified as HFimpEF.

“The reason for this, again, is because a transition from, say an EF of 10%-20% does not change therapy, but a move upward over 40% might, especially regarding decisions for device therapies, so the trajectory as well as the absolute EF is important,” she added.

“Particularly in the early stages, people are responsive to therapy and it’s possible in some cases to reverse heart failure, so I think this change helps us understand when that’s happened,” said Dr. Braunwald.

One step toward universality

“The implementation of this terminology and nomenclature into practice will require a variety of tactics,” said Dr. Bozkurt. “For example, the current ICD 10 codes need to incorporate the at-risk and pre–heart failure categories, as well as the mid-range EF, preserved, and improved EF classifications, because the treatment differs between those three domains.”

In terms of how these proposed changes will be worked into practice guidelines, Dr. Bozkurt declined to comment on this to avoid any perception of conflict of interest as she is the cochair of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF guideline writing committee.

Dr. Braunwald and Dr. Antman suggest it may be premature to call the new terminology and classifications “universal.” In an interview, Dr. Braunwald lamented the absence of the World Heart Federation, the ACC, and the AHA as active participants in this effort and suggested this paper is only the first step of a multistep process that requires input from many stakeholders.

“It’s important that these organizations be involved, not just to bless it, but to contribute their expertise to the process,” he said.

For his part, Dr. Mann hopes these changes will gain widespread acceptance and clinical traction. “The problem sometimes with guidelines is that they’re so data driven that you just can’t come out and say the obvious, so making a position statement is a good first step. And they got good international representation on this, so I think these changes will be accepted in the next heart failure guidelines.”

To encourage further discussion and acceptance, Robert J. Mentz, MD, and Anuradha Lala, MD, editor-in-chief and deputy editor of the Journal of Cardiac Failure, respectively, announced a series of multidisciplinary perspective pieces to be published in the journal monthly, starting in May with editorials from Dr. Clyde W Yancy, MD, MSc, and Carolyn S.P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, both of whom were authors of the consensus statement.

Dr. Bozkurt reports being a consultant for Abbott, Amgen, Baxter, Bristol Myers Squibb, Liva Nova Relypsa/Vifor Pharma, Respicardia, and being on the registry steering committee for Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Braunwald reports research grant support through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, and Novartis; and consulting for Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim/Lilly, Cardurion, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, and Verve. Dr. Mann has been a consultant to Novartis, is on the steering committee for the PARADISE trial, and is on the scientific advisory board for MyoKardia/Bristol Myers Squibb.

The terminology and classification scheme for heart failure (HF) is changing in ways that experts hope will directly impact patient outcomes.

In a new consensus statement, a multisociety group of experts proposed a new universal definition of heart failure and made substantial revisions to the way in which the disease is staged and classified.

The authors of the statement, led by writing committee chair and immediate past president of the Heart Failure Society of America Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, hope their efforts will go far to improve standardization of terminology, but more importantly will facilitate better management of the disease in ways that keep pace with current knowledge and advances in the field.

“There is a great need for reframing and standardizing the terminology across societies and different stakeholders, and importantly for patients because a lot of the terminology we were using was understood by academicians, but were not being translated in important ways to ensure patients are being appropriately treated,” said Dr. Bozkurt, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The consensus statement was a group effort led by the HFSA, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Japanese Heart Failure Society, with endorsements from the Canadian Heart Failure Society, the Heart Failure Association of India, the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the Chinese Heart Failure Association.

The article was published March 1 in the Journal of Cardiac Failure and the European Journal of Heart Failure, authored by a writing committee of 38 individuals with domain expertise in HF, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular disease.

“This is a very thorough and very carefully written document that I think will be helpful for clinicians because they’ve tapped into important changes in the field that have occurred over the past 10 years and that now allow us to do more for patients than we could before,” Eugene Braunwald, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Braunwald and Elliott M. Antman, MD, both from TIMI Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, wrote an editorial that accompanied the European Journal of Heart Failure article.

A new universal definition

“[Heart failure] is a clinical syndrome with symptoms and or signs caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and/or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion.”

This proposed definition, said the authors, is designed to be contemporary and simple “but conceptually comprehensive, with near universal applicability, prognostic and therapeutic viability, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity.”

Both left and right HF qualifies under this definition, said the authors, but conditions that result in marked volume overload, such as chronic kidney disease, which may present with signs and symptoms of HF, do not.

“Although some of these patients may have concomitant HF, these patients have a primary abnormality that may require a specific treatment beyond that for HF,” said the consensus statement authors.

For his part, Douglas L. Mann, MD, is happy to see what he considers a more accurate and practical definition for heart failure.

“We’ve had some wacky definitions in heart failure that haven’t made sense for 30 years, the principal of which is the definition of heart failure that says it’s the inability of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body,” Dr. Mann, of Washington University, St. Louis, said in an interview.

“I think this description was developed thinking about people with end-stage heart failure, but it makes no sense in clinical practice. Does it make sense to say about someone with New York Heart Association class I heart failure that their heart can’t meet the metabolic demands of the body?” said Dr. Mann, who was not involved with the writing of the consensus statement.

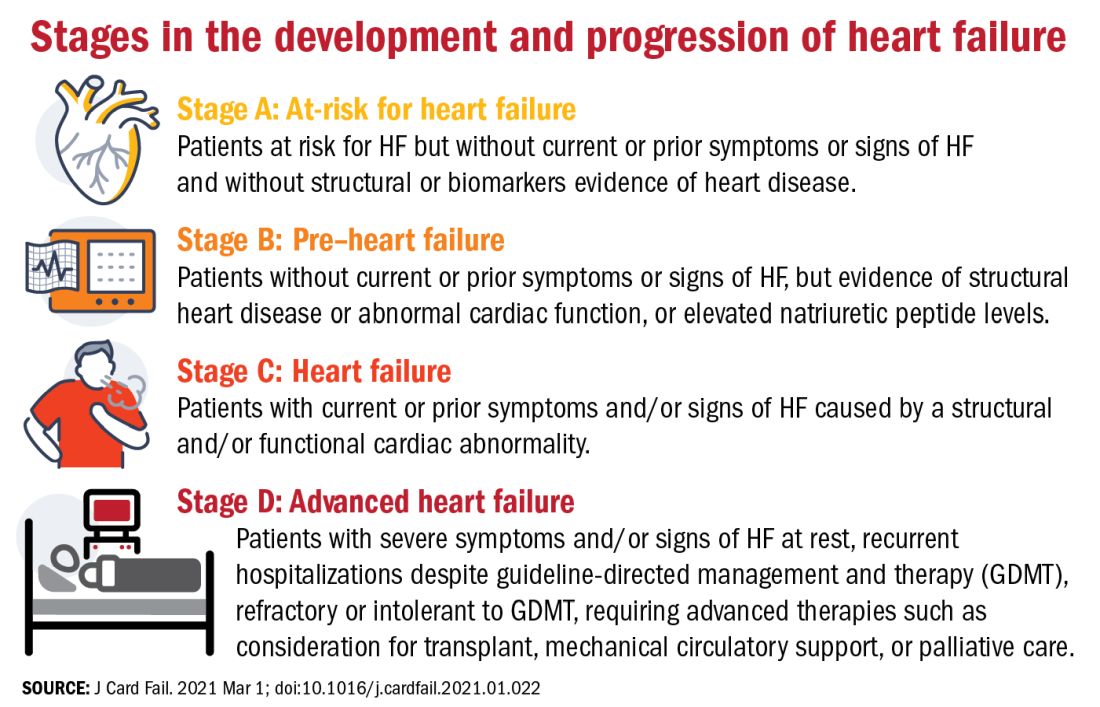

Proposed revised stages of the HF continuum

Overall, minimal changes have been made to the HF stages, with tweaks intended to enhance understanding and address the evolving role of biomarkers.

The authors proposed an approach to staging of HF:

- At-risk for HF (stage A), for patients at risk for HF but without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF and without structural or biomarkers evidence of heart disease.

- Pre-HF (stage B), for patients without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF, but evidence of structural heart disease or abnormal cardiac function, or elevated natriuretic peptide levels.

- HF (stage C), for patients with current or prior symptoms and/or signs of HF caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality.

- Advanced HF (stage D), for patients with severe symptoms and/or signs of HF at rest, recurrent hospitalizations despite guideline-directed management and therapy (GDMT), refractory or intolerant to GDMT, requiring advanced therapies such as consideration for transplant, mechanical circulatory support, or palliative care.

One notable change to the staging scheme is stage B, which the authors have reframed as “pre–heart failure.”

“Pre-cancer is a term widely understood and considered actionable and we wanted to tap into this successful messaging and embrace the pre–heart failure concept as something that is treatable and preventable,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

“We want patients and clinicians to understand that there are things we can do to prevent heart failure, strategies we didn’t have before, like SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes at risk for HF,” she added.

The revision also avoids the stigma of HF before the symptoms are manifest.

“Not calling it stage A and stage B heart failure you might say is semantics, but it’s important semantics,” said Dr. Braunwald. “When you’re talking to a patient or a relative and tell them they have stage A heart failure, it’s scares them unnecessarily. They don’t hear the stage A or B part, just the heart failure part.”

New classifications according to LVEF

And finally, in what some might consider the most obviously needed modification, the document proposes a new and revised classification of HF according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Most agree on how to classify heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but although the middle range has long been understood to be a clinically relevant, it has no proper name or clear delineation.

“For standardization across practice guidelines, to recognize clinical trajectories in HF, and to facilitate the recognition of different heart failure entities in a sensitive and specific manner that can guide therapy, we want to formalize the heart failure categories according to ejection fraction,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

To this end, the authors propose the following four classifications of EF:

- HF with reduced EF (HFrEF): LVEF of up to 40%.

- HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF): LVEF of 41-49%.

- HF with preserved EF (HFpEF)HF with an LVEF of at least 50%.

- HF with improved EF (HFimpEF): HF with a baseline LVEF of 40% or less, an increase of at least 10 points from baseline LVEF, and a second measurement of LVEF of greater than 40%.

HFmrEF is usually a transition period, noted Dr. Bozkurt. “Patients with HF in this range may represent a population whose EF is likely to change, either increase or decrease over time and it’s important to be cognizant of that trajectory. Understanding where your patient is headed is crucial for prognosis and optimization of guideline-directed treatment,” she said.

Improved, not recovered, HF

The last classification of heart failure with improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF) represents an important change to the current classification scheme.

“We want to clarify what terms to use but also which not to use. For example, we don’t want people to use recovered heart failure or heart failure in remission, partly because we don’t want the medication to be stopped. We don’t want to give the false message that there has been full recovery,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

As seen in the TRED-HF trial, guideline-directed medical therapy should be continued in patients with HF with improved EF regardless of whether it has improved to a normal range of above 50% in subsequent measurements.

“This is a distinct group of people, and for a while the guidelines were lumping them in with HFpEF, which I think is totally wrong,” said Dr. Mann.

“I think it’s very important that we emphasize heart failure as a continuum, rather than a one-way street of [inevitable] progression. Because we do see improvements in ejection fraction and we do see that we can prevent heart failure if we do the right things, and this should be reflected in the terminology we use,” he added.

Dr. Bozkurt stressed that HFimpEF only applies if the EF improves to above 40%. A move from an EF of 10%-20% would still see the patient classified as having HFrEF, but a patient whose EF improved from, say, 30% to 45% would be classified as HFimpEF.

“The reason for this, again, is because a transition from, say an EF of 10%-20% does not change therapy, but a move upward over 40% might, especially regarding decisions for device therapies, so the trajectory as well as the absolute EF is important,” she added.

“Particularly in the early stages, people are responsive to therapy and it’s possible in some cases to reverse heart failure, so I think this change helps us understand when that’s happened,” said Dr. Braunwald.

One step toward universality

“The implementation of this terminology and nomenclature into practice will require a variety of tactics,” said Dr. Bozkurt. “For example, the current ICD 10 codes need to incorporate the at-risk and pre–heart failure categories, as well as the mid-range EF, preserved, and improved EF classifications, because the treatment differs between those three domains.”

In terms of how these proposed changes will be worked into practice guidelines, Dr. Bozkurt declined to comment on this to avoid any perception of conflict of interest as she is the cochair of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association HF guideline writing committee.

Dr. Braunwald and Dr. Antman suggest it may be premature to call the new terminology and classifications “universal.” In an interview, Dr. Braunwald lamented the absence of the World Heart Federation, the ACC, and the AHA as active participants in this effort and suggested this paper is only the first step of a multistep process that requires input from many stakeholders.

“It’s important that these organizations be involved, not just to bless it, but to contribute their expertise to the process,” he said.

For his part, Dr. Mann hopes these changes will gain widespread acceptance and clinical traction. “The problem sometimes with guidelines is that they’re so data driven that you just can’t come out and say the obvious, so making a position statement is a good first step. And they got good international representation on this, so I think these changes will be accepted in the next heart failure guidelines.”

To encourage further discussion and acceptance, Robert J. Mentz, MD, and Anuradha Lala, MD, editor-in-chief and deputy editor of the Journal of Cardiac Failure, respectively, announced a series of multidisciplinary perspective pieces to be published in the journal monthly, starting in May with editorials from Dr. Clyde W Yancy, MD, MSc, and Carolyn S.P. Lam, MBBS, PhD, both of whom were authors of the consensus statement.

Dr. Bozkurt reports being a consultant for Abbott, Amgen, Baxter, Bristol Myers Squibb, Liva Nova Relypsa/Vifor Pharma, Respicardia, and being on the registry steering committee for Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Braunwald reports research grant support through Brigham and Women’s Hospital from AstraZeneca, Daiichi Sankyo, Merck, and Novartis; and consulting for Amgen, Boehringer-Ingelheim/Lilly, Cardurion, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, and Verve. Dr. Mann has been a consultant to Novartis, is on the steering committee for the PARADISE trial, and is on the scientific advisory board for MyoKardia/Bristol Myers Squibb.

The terminology and classification scheme for heart failure (HF) is changing in ways that experts hope will directly impact patient outcomes.

In a new consensus statement, a multisociety group of experts proposed a new universal definition of heart failure and made substantial revisions to the way in which the disease is staged and classified.

The authors of the statement, led by writing committee chair and immediate past president of the Heart Failure Society of America Biykem Bozkurt, MD, PhD, hope their efforts will go far to improve standardization of terminology, but more importantly will facilitate better management of the disease in ways that keep pace with current knowledge and advances in the field.

“There is a great need for reframing and standardizing the terminology across societies and different stakeholders, and importantly for patients because a lot of the terminology we were using was understood by academicians, but were not being translated in important ways to ensure patients are being appropriately treated,” said Dr. Bozkurt, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

The consensus statement was a group effort led by the HFSA, the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Japanese Heart Failure Society, with endorsements from the Canadian Heart Failure Society, the Heart Failure Association of India, the Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand, and the Chinese Heart Failure Association.

The article was published March 1 in the Journal of Cardiac Failure and the European Journal of Heart Failure, authored by a writing committee of 38 individuals with domain expertise in HF, cardiomyopathy, and cardiovascular disease.

“This is a very thorough and very carefully written document that I think will be helpful for clinicians because they’ve tapped into important changes in the field that have occurred over the past 10 years and that now allow us to do more for patients than we could before,” Eugene Braunwald, MD, said in an interview.

Dr. Braunwald and Elliott M. Antman, MD, both from TIMI Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, wrote an editorial that accompanied the European Journal of Heart Failure article.

A new universal definition

“[Heart failure] is a clinical syndrome with symptoms and or signs caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality and corroborated by elevated natriuretic peptide levels and/or objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion.”

This proposed definition, said the authors, is designed to be contemporary and simple “but conceptually comprehensive, with near universal applicability, prognostic and therapeutic viability, and acceptable sensitivity and specificity.”

Both left and right HF qualifies under this definition, said the authors, but conditions that result in marked volume overload, such as chronic kidney disease, which may present with signs and symptoms of HF, do not.

“Although some of these patients may have concomitant HF, these patients have a primary abnormality that may require a specific treatment beyond that for HF,” said the consensus statement authors.

For his part, Douglas L. Mann, MD, is happy to see what he considers a more accurate and practical definition for heart failure.

“We’ve had some wacky definitions in heart failure that haven’t made sense for 30 years, the principal of which is the definition of heart failure that says it’s the inability of the heart to meet the metabolic demands of the body,” Dr. Mann, of Washington University, St. Louis, said in an interview.

“I think this description was developed thinking about people with end-stage heart failure, but it makes no sense in clinical practice. Does it make sense to say about someone with New York Heart Association class I heart failure that their heart can’t meet the metabolic demands of the body?” said Dr. Mann, who was not involved with the writing of the consensus statement.

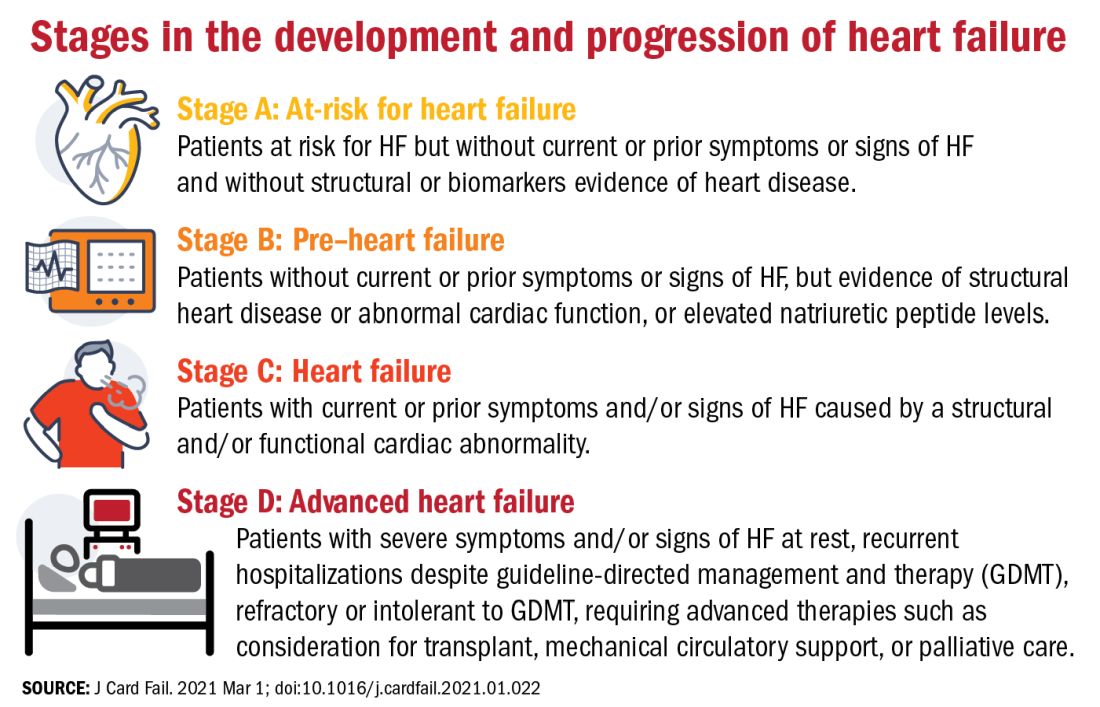

Proposed revised stages of the HF continuum

Overall, minimal changes have been made to the HF stages, with tweaks intended to enhance understanding and address the evolving role of biomarkers.

The authors proposed an approach to staging of HF:

- At-risk for HF (stage A), for patients at risk for HF but without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF and without structural or biomarkers evidence of heart disease.

- Pre-HF (stage B), for patients without current or prior symptoms or signs of HF, but evidence of structural heart disease or abnormal cardiac function, or elevated natriuretic peptide levels.

- HF (stage C), for patients with current or prior symptoms and/or signs of HF caused by a structural and/or functional cardiac abnormality.

- Advanced HF (stage D), for patients with severe symptoms and/or signs of HF at rest, recurrent hospitalizations despite guideline-directed management and therapy (GDMT), refractory or intolerant to GDMT, requiring advanced therapies such as consideration for transplant, mechanical circulatory support, or palliative care.

One notable change to the staging scheme is stage B, which the authors have reframed as “pre–heart failure.”

“Pre-cancer is a term widely understood and considered actionable and we wanted to tap into this successful messaging and embrace the pre–heart failure concept as something that is treatable and preventable,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

“We want patients and clinicians to understand that there are things we can do to prevent heart failure, strategies we didn’t have before, like SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with diabetes at risk for HF,” she added.

The revision also avoids the stigma of HF before the symptoms are manifest.

“Not calling it stage A and stage B heart failure you might say is semantics, but it’s important semantics,” said Dr. Braunwald. “When you’re talking to a patient or a relative and tell them they have stage A heart failure, it’s scares them unnecessarily. They don’t hear the stage A or B part, just the heart failure part.”

New classifications according to LVEF

And finally, in what some might consider the most obviously needed modification, the document proposes a new and revised classification of HF according to left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). Most agree on how to classify heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), but although the middle range has long been understood to be a clinically relevant, it has no proper name or clear delineation.

“For standardization across practice guidelines, to recognize clinical trajectories in HF, and to facilitate the recognition of different heart failure entities in a sensitive and specific manner that can guide therapy, we want to formalize the heart failure categories according to ejection fraction,” said Dr. Bozkurt.

To this end, the authors propose the following four classifications of EF:

- HF with reduced EF (HFrEF): LVEF of up to 40%.

- HF with mildly reduced EF (HFmrEF): LVEF of 41-49%.

- HF with preserved EF (HFpEF)HF with an LVEF of at least 50%.

- HF with improved EF (HFimpEF): HF with a baseline LVEF of 40% or less, an increase of at least 10 points from baseline LVEF, and a second measurement of LVEF of greater than 40%.

HFmrEF is usually a transition period, noted Dr. Bozkurt. “Patients with HF in this range may represent a population whose EF is likely to change, either increase or decrease over time and it’s important to be cognizant of that trajectory. Understanding where your patient is headed is crucial for prognosis and optimization of guideline-directed treatment,” she said.

Improved, not recovered, HF

The last classification of heart failure with improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF) represents an important change to the current classification scheme.

“We want to clarify what terms to use but also which not to use. For example, we don’t want people to use recovered heart failure or heart failure in remission, partly because we don’t want the medication to be stopped. We don’t want to give the false message that there has been full recovery,” said Dr. Bozkurt.