User login

Guidance issued on COVID vaccine use in patients with dermal fillers

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

outlining the potential risk and clinical relevance.

The association is not surprising, since other vaccines, including the influenza vaccine, have also been associated with inflammatory reactions in patients with dermal fillers. A warning about inflammatory events from these and other immunologic triggers should be part of routine informed consent, according to Sue Ellen Cox, MD, a coauthor of the guidance and the ASDS president-elect.

“Patients who have had dermal filler should not be discouraged from receiving the vaccine, and those who have received the vaccine should not be discouraged from receiving dermal filler,” Dr. Cox, who practices in Chapel Hill, N.C., said in an interview.

The only available data to assess the risk came from the trial of the Moderna vaccine. Of a total of 15,184 participants who received at least one dose of mRNA-1273, three developed facial or lip swelling that was presumably related to dermal filler. In the placebo group, there were no comparable inflammatory events.

“This is a very small number, but there is no reliable information about the number of patients in either group who had dermal filler, so we do not know the denominator,” Dr. Cox said.

In all three cases, the swelling at the site of dermal filler was observed within 2 days of the vaccination. None were considered a serious adverse event and all resolved. The filler had been administered 2 weeks prior to vaccination in one case, 6 months prior in a second, and time of administration was unknown in the third.

The resolution of the inflammatory reactions associated with the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is similar to those related to dermal fillers following other immunologic triggers, which not only include other vaccines, but viral or bacterial illnesses and dental procedures. Typically, they are readily controlled with oral corticosteroids, but also typically resolve even in the absence of treatment, according to Dr. Cox.

“The good news is that these will go away,” Dr. Cox said.

The ASDS guidance is meant to alert clinicians and patients to the potential association between inflammatory events and SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with dermal filler, but Dr. Cox said that it will ultimately have very little effect on her own practice. She already employs an informed consent that includes language warning about the potential risk of local reactions to immunological triggers that include vaccines. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination can now be added to examples of potential triggers, but it does not change the importance of informing patients of such triggers, Dr. Cox explained.

Asked if patients should be informed specifically about the association between dermal filler inflammatory reactions and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, the current ASDS president and first author of the guidance, Mathew Avram, MD, JD, suggested that they should. Although he emphasized that the side effect is clearly rare, he believes it deserves attention.

“We wanted dermatologists and other physicians to be aware of the potential. We focused on the available data but specifically decided not to provide any treatment recommendations at this time,” he said in an interview.

As new data become available, the Soft-Tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

“Our guidance was based only on the trial data, but there will soon be tens of millions of patients exposed to several different SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. We may learn things we do not know now, and we plan to communicate to our membership and others any new information as events unfold,” said Dr. Avram, who is director of dermatologic surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston,

Based on her own expertise in the field, Dr. Cox suggested that administration of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine and administration of dermal filler should be separated by at least 2 weeks regardless of which comes first. Her recommendation is not based on controlled data, but she considers this a prudent interval even if it has not been tested in a controlled study.

The full ASDS guidance is scheduled to appear in an upcoming issue of Dermatologic Surgery.

As new data become available, the Soft-tissue Fillers Guideline Task Force of the ASDS, which provided the guidance, will continue to monitor the relationship between SARS-CoV-2 vaccinations and dermal filler reactions, including other types of vaccines and the relative risks for hyaluronic acid and non–hyaluronic acid types of fillers.

This article was updated 1/7/21.

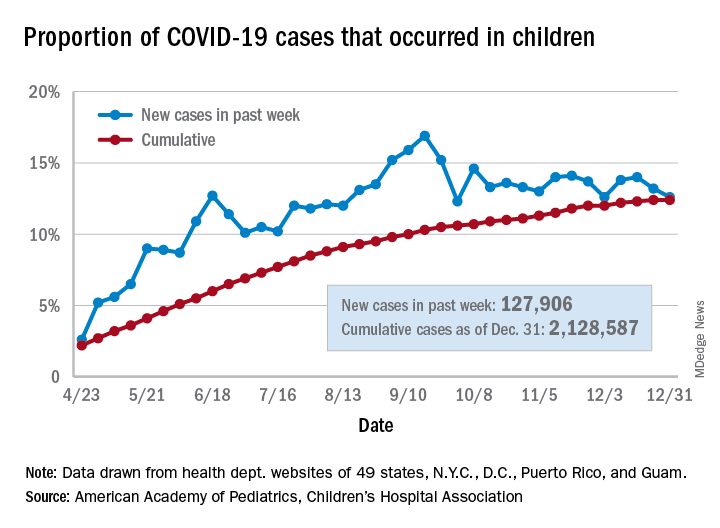

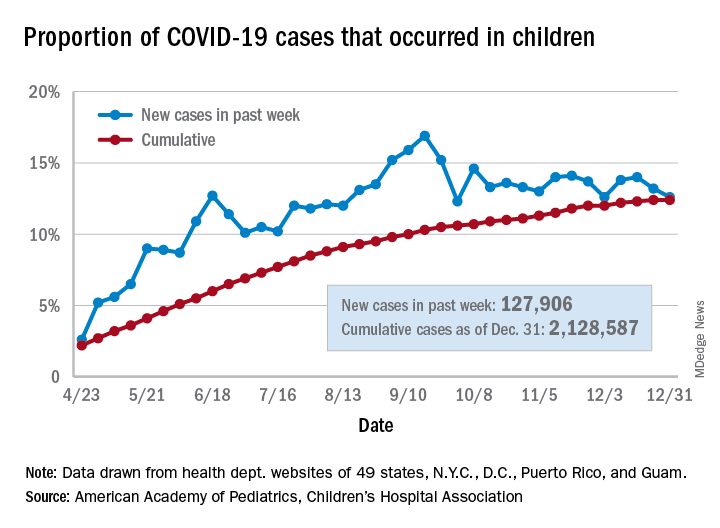

No increase seen in children’s cumulative COVID-19 burden

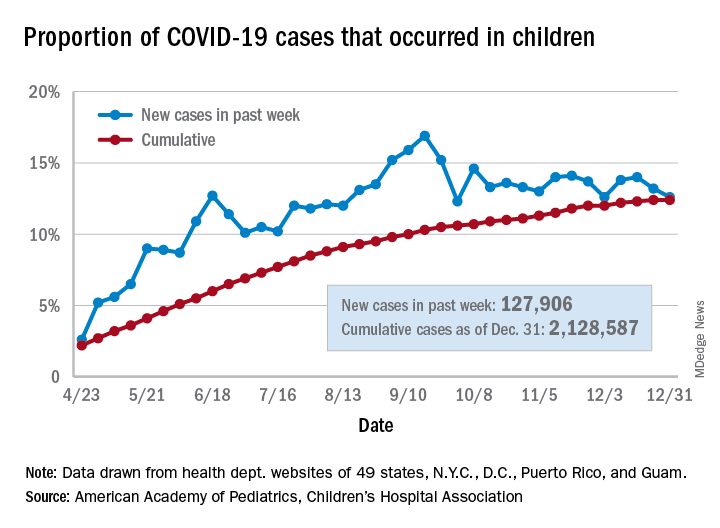

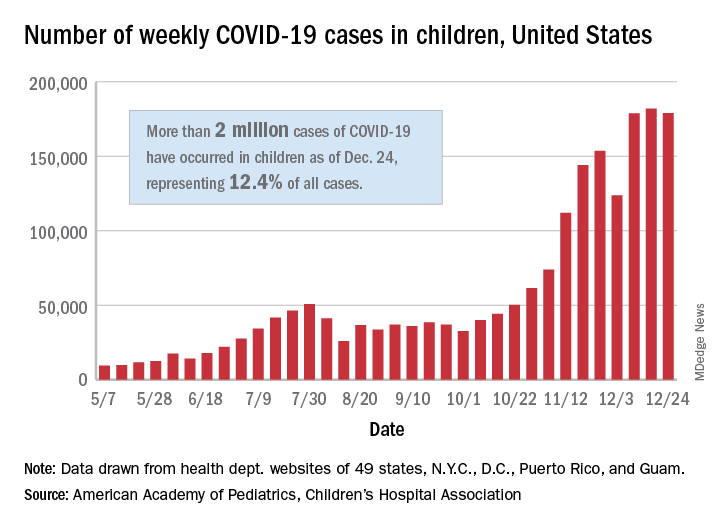

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

Children’s share of the cumulative COVID-19 burden remained at 12.4% for a second consecutive week, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly report. The last full week of 2020 also marked the second consecutive drop in new cases, although that may be holiday related.

There were almost 128,000 new cases of COVID-19 reported in children for the week, down from 179,000 cases the week before (Dec. 24) and down from the pandemic high of 182,000 reported 2 weeks earlier (Dec.17), based on data from 49 state health departments (excluding New York), along with the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam.

Children’s proportion of new cases for the week, 12.6%, is at its lowest point since early October after dropping for the second week in a row. The cumulative rate of COVID-19 infection, however, is now 2,828 cases per 100,000 children, up from 2,658 the previous week, the AAP and CHA said.

State-level metrics show that North Dakota has the highest cumulative rate at 7,851 per 100,000 children and Hawaii the lowest at 828. Wyoming’s cumulative proportion of child cases, 20.3%, is the highest in the country, while Florida, which uses an age range of 0-14 years for children, is the lowest at 7.1%. California’s total of 268,000 cases is almost double the number of second-place Illinois (138,000), the AAP/CHA data show.

Cumulative child deaths from COVID-19 are up to 179 in the jurisdictions reporting such data (43 states and New York City). That represents just 0.6% of all coronavirus-related deaths and has changed little over the last several months – never rising higher than 0.7% or dropping below 0.6% since early July, according to the report.

FDA warns about risk for false negatives from Curative COVID test

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

which is being used in Los Angeles and other large metropolitan areas in the United States.

The real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test was developed by Menlo Park, Calif.–based health care start-up Curative. Results are analyzed by the company’s clinical lab, KorvaLabs. The test, which is authorized for prescription use only, received emergency-use authorization from the FDA on April 16, 2020. By Nov. 9, the company had processed 6 million test results, according to the company.

The FDA alert cautions that false negative results from any COVID-19 test can lead to delays in or the lack of supportive treatment and increase the risk for viral spread.

To mitigate the risk for false negatives, the agency advises clinicians to perform the Curative test as described in the product’s Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers. This includes limiting its use to people who have had COVID-19 symptoms for 14 days or less. “Consider retesting your patients using a different test if you suspect an inaccurate result was given recently by the Curative SARS-Cov-2 test,” the FDA alert stated. “If testing was performed more than 2 weeks ago, and there is no reason to suspect current SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is not necessary to retest.”

The alert also notes that a negative result from the Curative PCR test “does not rule out COVID-19 and should not be used as the sole basis for treatment or patient management decisions. A negative result does not exclude the possibility of COVID-19.”

According to a press release issued by Curative on Oct. 7, its PCR test is being used by the Department of Defense, as well as the states of Alaska, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia (Atlanta and Savannah), Illinois (Chicago), Louisiana, Texas, and Wyoming. The company also operates Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments–certified laboratories in San Dimas, Calif.; Washington, D.C.; and Pflugerville, Tex.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Social isolation at the time of social distancing

Implications of loneliness and suggested management strategies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

During a busy morning of rounds, our patient, Mrs. M., appeared distraught. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 2 weeks prior and remained inpatient because of medicosocial reasons. Since admission she remained on the same ward, in the same room, cared for by the same group of providers donned in masks, gowns, gloves, and face shields. The personal protective equipment helped to shield us from the virus, but it also shielded Mrs. M. from us.

During initial interaction, Mrs. M. appeared anxious, tearful, and detached. It seemed that she recognized a new voice; however, she did not express much interest in engaging during the visit. When she realized that she was not being discharged, Mrs. M. appeared to lose further interest. She wanted to go home. Her outpatient dialysis arrangements were not complete, and that precluded hospital discharge. Prescribed anxiolytics were doing little to relieve her symptoms.

The next day, Mrs. M. continued to ask if she could go home. She stated that there was nothing for her to do while in the hospital. She was tired of watching TV, she was unable to call her friends, and was not able to see her family. Because of COVID-19 status, Mrs. M was not permitted to leave her hospital room, and she was transported to the dialysis unit via stretcher, being unable to walk. The more we talked, the more engaged Mrs. M. had become. When it was time to complete the encounter, Mrs. M. started pleading with us to “stay a little longer, please don’t leave.”

Throughout her hospitalization, Mrs. M. had an extremely limited number of human encounters. Those encounters were fragmented and brief, centered on the infection mitigation. The chaplain was not permitted to enter her room, and she was unwilling to use the phone. The subspecialty consultants utilized telemedicine visits. As a result, Mrs. M. felt isolated and lonely. Social distancing in the hospital makes human interactions particularly challenging and contributes to the development of isolation, loneliness, and fear.

Loneliness is real

Loneliness is the “subjective experience of involuntary social isolation.”1 As the COVID-19 pandemic began to entrap the world in early 2020, many people have faced new challenges – loneliness and its impact on physical and mental health. The prevalence of loneliness nearly tripled in the early months of the pandemic, leading to psychological distress and reopening conversations on ethical issues.2

Ethical implications of loneliness

Social distancing challenges all four main ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. How do we reconcile these principles from the standpoint of each affected individual, their caregivers, health care providers, and public health at large? How can we continue to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, but also remain attentive to our patients who are still in need of human interactions to recover and thrive?

Social distancing is important, but so is social interaction. What strategies do we have in place to combat loneliness? How do we help our hospitalized patients who feel connected to the “outside world?” Is battling loneliness worth the risks of additional exposure to COVID-19? These dilemmas cannot be easily resolved. However, it is important for us to recognize the negative impacts of loneliness and identify measures to help our patients.

In our mission to fulfill the beneficence and nonmaleficence principles of caring for patients affected by COVID-19, patients like Mrs. M. lose much of their autonomy during hospital admission. Despite our best efforts, our isolated patients during the pandemic, remain alone, which further heightens their feeling of loneliness.

Clinical implications of loneliness

With the advancements in technology, our capabilities to substitute personal human interactions have grown exponentially. The use of telemedicine, video- and audio-conferencing communications have changed the landscape of our capacities to exchange information. This could be a blessing and a curse. While the use of digital platforms for virtual communication is tempting, we should preserve human interactions as much as possible, particularly when caring for patients affected by COVID-19. Interpersonal “connectedness” plays a crucial role in providing psychological and psychotherapeutic support, particularly when the number of human encounters is already limited.

Social distancing requirements have magnified loneliness. Several studies demonstrate that the perception of loneliness leads to poor health outcomes, including lower immunity, increased peripheral vascular resistance,3 and higher overall mortality.4 Loneliness can lead to functional impairment, such as poor social skills, and even increased inflammation.5 The negative emotional impact of SARS-CoV-2 echoes the experiences of patients affected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. However, with COVID-19, we are witnessing the amplified effects of loneliness on a global scale. The majority of affected patients during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Canada reported loneliness, fear, aggression, and boredom: They had concerns about the impacts of the infection on loved ones, and psychological support was required for many patients with mild to moderate SARS disease.6

Nonpharmacological management strategies for battling loneliness

Utilization of early supportive services has been well described in literature and includes extending additional resources such as books, newspapers and, most importantly, additional in-person time to our patients.6 Maintaining rapport with patients’ families is also helpful in reducing anxiety and fear. The following measures have been suggested to prevent the negative impacts of loneliness and should be considered when caring for hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19.7

- Screen patients for depression and delirium and utilize delirium prevention measures throughout the hospitalization.

- Educate patients about the signs and symptoms of loneliness, fear, and anxiety.

- Extend additional resources to patients, including books, magazines, and newspapers.

- Keep the patient’s cell or hospital phone within their reach.

- Adequately manage pain and prevent insomnia.

- Communicate frequently, utilizing audio- and visual-teleconferencing platforms that simultaneously include the patient and their loved ones.

- For patients who continue to exhibit feelings of loneliness despite the above interventions, consider consultations with psychiatry to offer additional coping strategies.

- Ensure a multidisciplinary approach when applicable – proactive consultation with the members of a palliative care team, ethics, spiritual health, social and ancillary services.

It is important to recognize how vulnerable our patients are. Diagnosed with COVID-19, and caught in the midst of the current pandemic, not only do they suffer from the physical effects of this novel disease, but they also have to endure prolonged confinement, social isolation, and uncertainty – all wrapped in a cloak of loneliness and fear.

With our main focus being on the management of a largely unknown viral illness, patients’ personal experiences can be easily overlooked. It is vital for us as health care providers on the front lines to recognize, reflect, and reform to ease our patients’ journey through COVID-19.

Dr. Burklin is an assistant professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the department of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Wiley is an assistant professor of medicine, division of infectious disease, at the department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Schlomann A et al. Use of information and communication technology (ICT) devices among the oldest-old: Loneliness, anomie, and autonomy. Innov Aging. 2020 Jan 1;4(2):igz050.

2. McGinty E et al. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by U.S. adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020 Jun 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. 3. Wang J et al. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018 May 29;18(1):156.

4. Luo Y et al. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Mar;74(6):907-14.

5. Smith KJ et al. The association between loneliness, social isolation, and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Feb 21; 112:519-41.

6. Maunder R et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003 May 13;168(10):1245-51.

7. Masi CM et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011 Aug;15(3):219-66.

Implications of loneliness and suggested management strategies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

Implications of loneliness and suggested management strategies in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

During a busy morning of rounds, our patient, Mrs. M., appeared distraught. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 2 weeks prior and remained inpatient because of medicosocial reasons. Since admission she remained on the same ward, in the same room, cared for by the same group of providers donned in masks, gowns, gloves, and face shields. The personal protective equipment helped to shield us from the virus, but it also shielded Mrs. M. from us.

During initial interaction, Mrs. M. appeared anxious, tearful, and detached. It seemed that she recognized a new voice; however, she did not express much interest in engaging during the visit. When she realized that she was not being discharged, Mrs. M. appeared to lose further interest. She wanted to go home. Her outpatient dialysis arrangements were not complete, and that precluded hospital discharge. Prescribed anxiolytics were doing little to relieve her symptoms.

The next day, Mrs. M. continued to ask if she could go home. She stated that there was nothing for her to do while in the hospital. She was tired of watching TV, she was unable to call her friends, and was not able to see her family. Because of COVID-19 status, Mrs. M was not permitted to leave her hospital room, and she was transported to the dialysis unit via stretcher, being unable to walk. The more we talked, the more engaged Mrs. M. had become. When it was time to complete the encounter, Mrs. M. started pleading with us to “stay a little longer, please don’t leave.”

Throughout her hospitalization, Mrs. M. had an extremely limited number of human encounters. Those encounters were fragmented and brief, centered on the infection mitigation. The chaplain was not permitted to enter her room, and she was unwilling to use the phone. The subspecialty consultants utilized telemedicine visits. As a result, Mrs. M. felt isolated and lonely. Social distancing in the hospital makes human interactions particularly challenging and contributes to the development of isolation, loneliness, and fear.

Loneliness is real

Loneliness is the “subjective experience of involuntary social isolation.”1 As the COVID-19 pandemic began to entrap the world in early 2020, many people have faced new challenges – loneliness and its impact on physical and mental health. The prevalence of loneliness nearly tripled in the early months of the pandemic, leading to psychological distress and reopening conversations on ethical issues.2

Ethical implications of loneliness

Social distancing challenges all four main ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. How do we reconcile these principles from the standpoint of each affected individual, their caregivers, health care providers, and public health at large? How can we continue to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, but also remain attentive to our patients who are still in need of human interactions to recover and thrive?

Social distancing is important, but so is social interaction. What strategies do we have in place to combat loneliness? How do we help our hospitalized patients who feel connected to the “outside world?” Is battling loneliness worth the risks of additional exposure to COVID-19? These dilemmas cannot be easily resolved. However, it is important for us to recognize the negative impacts of loneliness and identify measures to help our patients.

In our mission to fulfill the beneficence and nonmaleficence principles of caring for patients affected by COVID-19, patients like Mrs. M. lose much of their autonomy during hospital admission. Despite our best efforts, our isolated patients during the pandemic, remain alone, which further heightens their feeling of loneliness.

Clinical implications of loneliness

With the advancements in technology, our capabilities to substitute personal human interactions have grown exponentially. The use of telemedicine, video- and audio-conferencing communications have changed the landscape of our capacities to exchange information. This could be a blessing and a curse. While the use of digital platforms for virtual communication is tempting, we should preserve human interactions as much as possible, particularly when caring for patients affected by COVID-19. Interpersonal “connectedness” plays a crucial role in providing psychological and psychotherapeutic support, particularly when the number of human encounters is already limited.

Social distancing requirements have magnified loneliness. Several studies demonstrate that the perception of loneliness leads to poor health outcomes, including lower immunity, increased peripheral vascular resistance,3 and higher overall mortality.4 Loneliness can lead to functional impairment, such as poor social skills, and even increased inflammation.5 The negative emotional impact of SARS-CoV-2 echoes the experiences of patients affected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. However, with COVID-19, we are witnessing the amplified effects of loneliness on a global scale. The majority of affected patients during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Canada reported loneliness, fear, aggression, and boredom: They had concerns about the impacts of the infection on loved ones, and psychological support was required for many patients with mild to moderate SARS disease.6

Nonpharmacological management strategies for battling loneliness

Utilization of early supportive services has been well described in literature and includes extending additional resources such as books, newspapers and, most importantly, additional in-person time to our patients.6 Maintaining rapport with patients’ families is also helpful in reducing anxiety and fear. The following measures have been suggested to prevent the negative impacts of loneliness and should be considered when caring for hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19.7

- Screen patients for depression and delirium and utilize delirium prevention measures throughout the hospitalization.

- Educate patients about the signs and symptoms of loneliness, fear, and anxiety.

- Extend additional resources to patients, including books, magazines, and newspapers.

- Keep the patient’s cell or hospital phone within their reach.

- Adequately manage pain and prevent insomnia.

- Communicate frequently, utilizing audio- and visual-teleconferencing platforms that simultaneously include the patient and their loved ones.

- For patients who continue to exhibit feelings of loneliness despite the above interventions, consider consultations with psychiatry to offer additional coping strategies.

- Ensure a multidisciplinary approach when applicable – proactive consultation with the members of a palliative care team, ethics, spiritual health, social and ancillary services.

It is important to recognize how vulnerable our patients are. Diagnosed with COVID-19, and caught in the midst of the current pandemic, not only do they suffer from the physical effects of this novel disease, but they also have to endure prolonged confinement, social isolation, and uncertainty – all wrapped in a cloak of loneliness and fear.

With our main focus being on the management of a largely unknown viral illness, patients’ personal experiences can be easily overlooked. It is vital for us as health care providers on the front lines to recognize, reflect, and reform to ease our patients’ journey through COVID-19.

Dr. Burklin is an assistant professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the department of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Wiley is an assistant professor of medicine, division of infectious disease, at the department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Schlomann A et al. Use of information and communication technology (ICT) devices among the oldest-old: Loneliness, anomie, and autonomy. Innov Aging. 2020 Jan 1;4(2):igz050.

2. McGinty E et al. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by U.S. adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020 Jun 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. 3. Wang J et al. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018 May 29;18(1):156.

4. Luo Y et al. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Mar;74(6):907-14.

5. Smith KJ et al. The association between loneliness, social isolation, and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Feb 21; 112:519-41.

6. Maunder R et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003 May 13;168(10):1245-51.

7. Masi CM et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011 Aug;15(3):219-66.

During a busy morning of rounds, our patient, Mrs. M., appeared distraught. She was diagnosed with COVID-19 2 weeks prior and remained inpatient because of medicosocial reasons. Since admission she remained on the same ward, in the same room, cared for by the same group of providers donned in masks, gowns, gloves, and face shields. The personal protective equipment helped to shield us from the virus, but it also shielded Mrs. M. from us.

During initial interaction, Mrs. M. appeared anxious, tearful, and detached. It seemed that she recognized a new voice; however, she did not express much interest in engaging during the visit. When she realized that she was not being discharged, Mrs. M. appeared to lose further interest. She wanted to go home. Her outpatient dialysis arrangements were not complete, and that precluded hospital discharge. Prescribed anxiolytics were doing little to relieve her symptoms.

The next day, Mrs. M. continued to ask if she could go home. She stated that there was nothing for her to do while in the hospital. She was tired of watching TV, she was unable to call her friends, and was not able to see her family. Because of COVID-19 status, Mrs. M was not permitted to leave her hospital room, and she was transported to the dialysis unit via stretcher, being unable to walk. The more we talked, the more engaged Mrs. M. had become. When it was time to complete the encounter, Mrs. M. started pleading with us to “stay a little longer, please don’t leave.”

Throughout her hospitalization, Mrs. M. had an extremely limited number of human encounters. Those encounters were fragmented and brief, centered on the infection mitigation. The chaplain was not permitted to enter her room, and she was unwilling to use the phone. The subspecialty consultants utilized telemedicine visits. As a result, Mrs. M. felt isolated and lonely. Social distancing in the hospital makes human interactions particularly challenging and contributes to the development of isolation, loneliness, and fear.

Loneliness is real

Loneliness is the “subjective experience of involuntary social isolation.”1 As the COVID-19 pandemic began to entrap the world in early 2020, many people have faced new challenges – loneliness and its impact on physical and mental health. The prevalence of loneliness nearly tripled in the early months of the pandemic, leading to psychological distress and reopening conversations on ethical issues.2

Ethical implications of loneliness

Social distancing challenges all four main ethical principles: autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. How do we reconcile these principles from the standpoint of each affected individual, their caregivers, health care providers, and public health at large? How can we continue to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, but also remain attentive to our patients who are still in need of human interactions to recover and thrive?

Social distancing is important, but so is social interaction. What strategies do we have in place to combat loneliness? How do we help our hospitalized patients who feel connected to the “outside world?” Is battling loneliness worth the risks of additional exposure to COVID-19? These dilemmas cannot be easily resolved. However, it is important for us to recognize the negative impacts of loneliness and identify measures to help our patients.

In our mission to fulfill the beneficence and nonmaleficence principles of caring for patients affected by COVID-19, patients like Mrs. M. lose much of their autonomy during hospital admission. Despite our best efforts, our isolated patients during the pandemic, remain alone, which further heightens their feeling of loneliness.

Clinical implications of loneliness

With the advancements in technology, our capabilities to substitute personal human interactions have grown exponentially. The use of telemedicine, video- and audio-conferencing communications have changed the landscape of our capacities to exchange information. This could be a blessing and a curse. While the use of digital platforms for virtual communication is tempting, we should preserve human interactions as much as possible, particularly when caring for patients affected by COVID-19. Interpersonal “connectedness” plays a crucial role in providing psychological and psychotherapeutic support, particularly when the number of human encounters is already limited.

Social distancing requirements have magnified loneliness. Several studies demonstrate that the perception of loneliness leads to poor health outcomes, including lower immunity, increased peripheral vascular resistance,3 and higher overall mortality.4 Loneliness can lead to functional impairment, such as poor social skills, and even increased inflammation.5 The negative emotional impact of SARS-CoV-2 echoes the experiences of patients affected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003. However, with COVID-19, we are witnessing the amplified effects of loneliness on a global scale. The majority of affected patients during the 2003 SARS outbreak in Canada reported loneliness, fear, aggression, and boredom: They had concerns about the impacts of the infection on loved ones, and psychological support was required for many patients with mild to moderate SARS disease.6

Nonpharmacological management strategies for battling loneliness

Utilization of early supportive services has been well described in literature and includes extending additional resources such as books, newspapers and, most importantly, additional in-person time to our patients.6 Maintaining rapport with patients’ families is also helpful in reducing anxiety and fear. The following measures have been suggested to prevent the negative impacts of loneliness and should be considered when caring for hospitalized patients diagnosed with COVID-19.7

- Screen patients for depression and delirium and utilize delirium prevention measures throughout the hospitalization.

- Educate patients about the signs and symptoms of loneliness, fear, and anxiety.

- Extend additional resources to patients, including books, magazines, and newspapers.

- Keep the patient’s cell or hospital phone within their reach.

- Adequately manage pain and prevent insomnia.

- Communicate frequently, utilizing audio- and visual-teleconferencing platforms that simultaneously include the patient and their loved ones.

- For patients who continue to exhibit feelings of loneliness despite the above interventions, consider consultations with psychiatry to offer additional coping strategies.

- Ensure a multidisciplinary approach when applicable – proactive consultation with the members of a palliative care team, ethics, spiritual health, social and ancillary services.

It is important to recognize how vulnerable our patients are. Diagnosed with COVID-19, and caught in the midst of the current pandemic, not only do they suffer from the physical effects of this novel disease, but they also have to endure prolonged confinement, social isolation, and uncertainty – all wrapped in a cloak of loneliness and fear.

With our main focus being on the management of a largely unknown viral illness, patients’ personal experiences can be easily overlooked. It is vital for us as health care providers on the front lines to recognize, reflect, and reform to ease our patients’ journey through COVID-19.

Dr. Burklin is an assistant professor of medicine, division of hospital medicine, at the department of medicine, Emory University, Atlanta. Dr. Wiley is an assistant professor of medicine, division of infectious disease, at the department of Medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

References

1. Schlomann A et al. Use of information and communication technology (ICT) devices among the oldest-old: Loneliness, anomie, and autonomy. Innov Aging. 2020 Jan 1;4(2):igz050.

2. McGinty E et al. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by U.S. adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020 Jun 3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740. 3. Wang J et al. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018 May 29;18(1):156.

4. Luo Y et al. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: A national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012 Mar;74(6):907-14.

5. Smith KJ et al. The association between loneliness, social isolation, and inflammation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020 Feb 21; 112:519-41.

6. Maunder R et al. The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. CMAJ. 2003 May 13;168(10):1245-51.

7. Masi CM et al. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011 Aug;15(3):219-66.

Microvascular injury of brain, olfactory bulb seen in COVID-19

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Postmortem MRI brain scans of 13 patients who died from COVID-19 showed abnormalities in 10 of the participants. Of these, nine showed punctate hyperintensities, “which represented areas of microvascular injury and fibrinogen leakage,” the investigators reported. Immunostaining also showed a thinning of the basal lamina in five of these patients.

Further analyses showed punctate hypointensities linked to congested blood vessels in 10 patients. These areas were “interpreted as microhemorrhages,” the researchers noted.

There was no evidence of viral infection, including SARS-CoV-2.

“These findings may inform the interpretation of changes observed on [MRI] of punctate hyperintensities and linear hypointensities in patients with COVID-19,” wrote Myoung-Hwa Lee, PhD, a research fellow at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and colleagues. The findings were published online Dec. 30 in a “correspondence” piece in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Interpret with caution

The investigators examined brains from a convenience sample of 19 patients (mean age, 50 years), all of whom died from COVID-19 between March and July 2020.

An 11.7-tesla scanner was used to obtain magnetic resonance microscopy images for 13 of the patients. In order to scan the olfactory bulb, the scanner was set at a resolution of 25 mcm; for the brain, it was set at 100 mcm.

Chromogenic immunostaining was used to assess brain abnormalities found in 10 of the patients. Multiplex fluorescence imaging was also used for some of the patients.

For 18 study participants, a histopathological brain examination was performed. In the patients who also had medical histories available to the researchers, five had mild respiratory syndrome, four had acute respiratory distress syndrome, two had pulmonary embolism, one had delirium, and three had unknown symptoms.

The punctate hyperintensities found on magnetic resonance microscopy were also found on histopathological exam. Collagen IV immunostaining showed a thinning in the basal lamina of endothelial cells in these areas.

In addition to congested blood vessels, punctate hypointensities were linked to areas of fibrinogen leakage – but also to “relatively intact vasculature,” the investigators reported.

“There was minimal perivascular inflammation in the specimens examined, but there was no vascular occlusion,” they added.

SARS-CoV-2 was also not found in any of the participants. “It is possible that the virus was cleared by the time of death or that viral copy numbers were below the level of detection by our assays,” the researchers noted.

In 13 of the patients, hypertrophic astrocytes, macrophage infiltrates, and perivascular-activated microglia were found. Eight patients showed CD3+ and CD8+ T cells in spaces and lumens next to endothelial cells.

Finally, five patients showed activated microglia next to neurons. This is “suggestive of neuronophagia in the olfactory bulb, substantial nigra, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagal nerve, and the pre-Bötzinger complex in the medulla, which is involved in the generation of spontaneous rhythmic breathing,” wrote the investigators.

In summary, vascular pathology was found in 10 cases, perivascular infiltrates were present in 13 cases, acute ischemic hypoxic neurons were present in 6 cases, and changes suggestive of neuronophagia were present in 5 cases.

The researchers noted that, although the study findings may be helpful when interpreting brain changes on MRI scan in this patient population, availability of clinical information for the participants was limited.

Therefore, “no conclusions can be drawn in relation to neurologic features of COVID-19,” they wrote.

The study was funded by NINDS. Dr. Lee and all but one of the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships; the remaining investigator reported having received grants from NINDS during the conduct of this study.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

U.S. hits 20 million cases as COVID variant spreads

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The United States started 2021 they way it ended 2020: Setting new records amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The country passed the 20 million mark for coronavirus cases on Friday, setting the mark sometime around noon, according to Johns Hopkins University’s COVID-19 tracker. The total is nearly twice as many as the next worst country – India, which has 10.28 million cases.

Along with the case count, more than 346,000 Americans have now died of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. That is 77% more fatalities than Brazil, which ranks second globally with 194,949 deaths.

More than 125,370 coronavirus patients were hospitalized on Thursday, the fourth record-setting day in a row, according to the COVID Tracking Project.

Going by official tallies, it took 292 days for the United States to reach its first 10 million cases, and just 54 more days to double it, CNN reported.

Meanwhile, 12.41 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines have been distributed in the United States as of Wednesday, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Yet only 2.8 million people have received the first of a two-shot regimen.

The slower-than-hoped-for rollout of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines comes as a new variant of the coronavirus has emerged in a third state. Florida officials announced a confirmed case of the new variant – believed to have originated in the United Kingdom – in Martin County in southeast Florida.

The state health department said on Twitter that the patient is a man in his 20s with no history of travel. The department said it is working with the CDC to investigate.

The variant has also been confirmed in cases in Colorado and California. It is believed to be more contagious. The BBC reported that the new variant increases the reproduction, or “R number,” by 0.4 and 0.7. The UK’s most recent R number has been estimated at 1.1-1.3, meaning anyone who has the coronavirus could be assumed to spread it to up to 1.3 people.

The R number needs to be below 1.0 for the spread of the virus to fall.

“There is a huge difference in how easily the variant virus spreads,” Professor Axel Gandy of London’s Imperial College told BBC News. “This is the most serious change in the virus since the epidemic began.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Racism in medicine: Implicit and explicit

With the shootings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and other Black citizens setting off protests and unrest, race was at the forefront of national conversation in the United States – along with COVID-19 – over the past year.

“We’ve heard things like, ‘We’re in a post-racial society,’ but I think 2020 in particular has emphasized that we’re not,” said Gregory Johnson, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer of hospital medicine at Sound Physicians, a national physician practice. “Racism is very present in our lives, it’s very present in our world, and it is absolutely present in medicine.”

Yes, race is still an issue in the U.S. as we head into 2021, though this may have come as something of a surprise to people who do not live with racism daily.

“If you have a brain, you have bias, and that bias will likely apply to race as well,” Dr. Johnson said. “When we’re talking about institutional racism, the educational system and the media have led us to create presumptions and prejudices that we don’t necessarily recognize off the top because they’ve just been a part of the fabric of who we are as we’ve grown up.”

The term “racism” has extremely negative connotations because there’s character judgment attached to it, but to say someone is racist or racially insensitive does not equate them with being a Klansman, said Dr. Johnson. “I think we as people have to acknowledge that, yes, it’s possible for me to be racist and I might not be 100% aware of it. It’s being open to the possibility – or rather probability – that you are and then taking steps to figure out how you can address that, so you can limit it. And that requires constant self-evaluation and work,” he said.

Racism in the medical environment

Institutional racism is evident before students are even accepted into medical school, said Areeba Kara, MD, SFHM, associate professor of clinical medicine at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and a hospitalist at IU Health Physicians.

Mean MCAT scores are lower for applicants traditionally underrepresented in medicine (UIM) compared to the scores of well-represented groups.1 “Lower scores are associated with lower acceptance rates into medical school,” Dr. Kara said. “These differences reflect unequal educational opportunities rooted in centuries of legal discrimination.”

Racism is apparent in both the hidden medical education curriculum and in lessons implicitly taught to students, said Ndidi Unaka, MD, MEd, associate program director of the pediatric residency training program at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital.

“These lessons inform the way in which we as physicians see our patients, each other, and how we practice,” she said. “We reinforce race-based medicine and shape clinical decision making through flawed guidelines and practices, which exacerbates health inequities. We teach that race – rather than racism – is a risk factor for poor health outcomes. Our students and trainees watch as we assume the worst of our patients from marginalized communities of color.”

Terms describing patients of color, such as “difficult,” “non-compliant,” or “frequent flyer” are thrown around and sometimes, instead of finding out why, “we view these states of being as static, root causes for poor outcomes rather than symptoms of social conditions and obstacles that impact overall health and wellbeing,” Dr. Unaka said.

Leadership opportunities

Though hospital medicine is a growing field, Dr. Kara noted that the 2020 State of Hospital Medicine Report found that only 5.5% of hospital medical group leaders were Black, and just 2.2% were Hispanic/Latino.2 “I think these numbers speak for themselves,” she said.

Dr. Unaka said that the lack of UIM hospitalists and physician leaders creates fewer opportunities for “race-concordant mentorship relationships.” It also forces UIM physicians to shoulder more responsibilities – often obligations that do little to help them move forward in their careers – all in the name of diversity. And when UIM physicians are given leadership opportunities, Dr. Unaka said they are often unsure as to whether their appointments are genuine or just a hollow gesture made for the sake of diversity.

Dr. Johnson pointed out that Black and Latinx populations primarily get their care from hospital-based specialties, yet this is not reflected in the number of UIM practitioners in leadership roles. He said race and ethnicity, as well as gender, need to be factors when individuals are evaluated for leadership opportunities – for the individual’s sake, as well as for the community he or she is serving.

“When we can evaluate for unconscious bias and factor in that diverse groups tend to have better outcomes, whether it’s business or clinical outcomes, it’s one of the opportunities that we collectively have in the specialty to improve what we’re delivering for hospitals and, more importantly, for patients,” he said.

Relationships with colleagues and patients

Racism creeps into interactions and relationships with others as well, whether it’s between clinicians, clinician to patient, or patient to clinician. Sometimes it’s blatant; often it’s subtle.

A common, recurring example Dr. Unaka has experienced in the clinician to clinician relationship is being confused for other Black physicians, making her feel invisible. “The everyday verbal, nonverbal, and environmental slights, snubs, or insults from colleagues are frequent and contribute to feelings of exclusion, isolation, and exhaustion,” she said. Despite this, she is still expected to “address microaggressions and other forms of interpersonal racism and find ways to move through professional spaces in spite of the trauma, fear, and stress associated with my reality and lived experiences.” She said that clinicians who remain silent on the topic of racism participate in the violence and contribute to the disillusionment of UIM physicians.

Dr. Kara said that the discrimination from the health care team is the hardest to deal with. In the clinician to clinician relationship, there is a sense among UIM physicians that they’re being watched more closely and “have to prove themselves at every single turn.” Unfortunately, this comes from the environment, which tends to be adversarial rather than supportive and nurturing, she said.

“There are lots of opportunities for racism or racial insensitivity to crop up from clinician to clinician,” said Dr. Johnson. When he started his career as a physician after his training, Dr. Johnson was informed that his colleagues were watching him because they were not sure about his clinical skills. The fact that he was a former chief resident and board certified in two specialties did not seem to make any difference.