User login

Managing dyspepsia

› Review the medications taken by patients who suffer from dyspepsia, as many drugs—bisphosphonates, antibiotics, steroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, among others—are associated with this condition. B

› Order an esophagogastroduodenoscopy for patients ages 55 years or older with new-onset dyspepsia and those who have red flags for more serious conditions, eg, a history of upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancer, unintended weight loss, GI bleeding, dysphagia, or a palpable mass. C

› Prescribe acid suppression therapy as first-line treatment for patients who have dyspepsia but are at low risk or have tested negative for Helicobacter pylori infection. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year, an estimated 25% to 30% of the US population suffers from dyspepsia.1 Most self-treat with home remedies and over-the-counter products, but others seek medical care. Dyspepsia accounts for an estimated 2% to 5% of primary care visits annually,2 mostly by patients who are found to have no organic, or structural, cause for their symptoms.1,3

Such patients are said to have functional dyspepsia (FD), a category that applies to about two-thirds of those with dyspepsia.1 A small number of cases are categorized as organic dyspepsia, indicating the presence of a clear structural or anatomic cause, such as an ulcer or mass. The remainder are said to have undifferentiated dyspepsia, which simply means that their signs and symptoms do not rise to the level for which further investigation is warranted and thus it is not known whether it is functional or organic.

There are many possible causes of FD, ranging from medications3,4 to abnormal gastroduodenal motility5,6 to Helicobacter pylori infection,7 and a comprehensive differential diagnosis. The first step in an investigation is to rule out red flags suggestive of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer or other serious disorders.

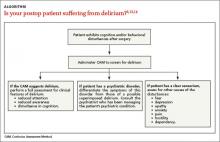

Patients with FD, like the vast majority of those you’ll treat in a primary care setting, suffer significant morbidity. Most have chronic symptoms, with intermittent flare-ups interspersed with periods of remission.8 In the text and dyspepsia treatment ALGORITHM5,7-12 that follow, you’ll find an evidence-based patient management approach.

Symptoms and causes: What to look for

The primary symptoms of dyspepsia include bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain and burning. To meet the Rome criteria for dyspepsia, these symptoms must have been present for the last 3 months and have had an onset ≥6 months prior to diagnosis.2 Recurrent belching and nausea are also common, but are not included in the Rome diagnostic criteria.

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of the condition, however, and more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.13,14 Indeed, anxiety is a common comorbidity in patients with FD and a risk factor for the diagnosis. Compared with the general public, patients with FD have been found to have higher levels of anxiety, chronic tension, hostility, and hypochondriasis, and a tendency to be more pessimistic.15

Possible causes of FD

While the etiology of organic dyspepsia is clear, the cause of FD is often far more difficult to determine.

Medication use should always be considered, as many types of drugs—including bisphosphonates, antibiotics, narcotics, steroids, iron, metformin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—are associated with dyspepsia.3,4

Gastroduodenal motility and accommodation, which has been found in numerous studies of patients with FD, is a proposed etiology.5,6

Visceral hypersensitivity also appears to play a role. In one study of patients with severe dyspepsia, 87% of those with FD had a reduced or altered GI pain threshold, compared with 20% of those with organic dyspepsia.16

H pylori, commonly linked to peptic ulcer disease (PUD), is also associated with both organic dyspepsia and FD.17,18 The gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium is present in approximately half of the population worldwide, but is more common in developing nations.7H pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) is more prevalent in patients with dyspepsia, particularly in those younger than 30 years of age. The exact mechanism by which H pylori causes non-ulcerative dyspepsia is not clear, but inflammation, dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and alteration of acid secretion have all been proposed.17

Dysfunctional intestinal epithelium is increasingly being considered in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia, among other conditions. Researchers theorize that certain foods, toxins, infections, and/or other stressors lead to changes in the structure and function of tight junctions, resulting in increased intestinal permeability.19 This in turn is thought to allow the outflow of antigens through the leaky epithelium and to stimulate an immune response—a process that may play a role in the increased GI inflammation or hypersensitivity associated with dyspepsia. The “leaky gut” theory may eventually lead to new ways to treat dyspepsia, but thus far, highquality evidence of the efficacy of treatments aimed at this mechanism is lacking.

A range of disorders included in the differential

The primary differential diagnosis for dyspepsia includes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, chronic PUD (including both gastric and duodenal ulcers), and malignancy. The differential may also include biliary disorder, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or other liver disease; chronic abdominal wall pain, irritable bowel syndrome, motility disorders, or infiltrative diseases of the stomach (eosinophilic gastritis, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis); celiac disease and food sensitivities/allergies, including gluten, lactose, and other intolerances; cardiac disease, including acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias; intestinal angina; small intestine bacterial overgrowth; heavy metal toxicity; and hypercalcemia.8

Ulcers are found in approximately 10% of patients undergoing evaluation for dyspepsia.8 Previously, PUD was almost exclusively due to H pylori infection. In developed countries, however, chronic use of NSAIDs, including aspirin, has increased, and is now responsible for most ulcer diseases.20,21 The combination of H pylori infection and NSAID usage appears to be synergistic, with the risk of uncomplicated PUD estimated to be 17.5 times higher among those who test positive for H pylori and take NSAIDs vs a 3- to 4-fold increase in ulcer incidence among those with either of these risk factors alone.22

The work-up starts with a search for red flags

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of dyspepsia; more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.

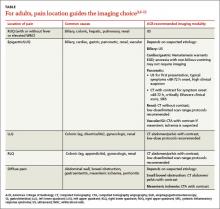

Evaluation of a patient with dyspepsia begins with a thorough history. Start by determining whether the patient has any red flags, or alarm features, that may be associated with a more serious condition—particularly an underlying malignancy. One or more of the following is an indication for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD):5,8,12

• family and/or personal history of upper GI cancer

• unintended weight loss

• GI bleeding

• progressive dysphagia

• unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

• persistent vomiting

• palpable mass or lymphadenopathy

• jaundice.

While it is important to rule out these red flags, they are poor predictors of malignancy.23,24 With the exception of a single study, their positive predictive value was a mere 1%.8 Their usefulness lies in their ability to exclude malignancy, however; when none of these features is present, the negative predictive value for malignancy is >97%.8

Age is also a risk factor. In addition to red flags, EGD is recommended by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) for patients with new-onset dyspepsia who are 55 years or older—an age at which upper GI malignancy becomes more common. A repeat EGD is rarely indicated, unless Barrett’s esophagus or severe erosive esophagitis is found on the initial EGD.25

Physical exam, H pylori evaluation follow

A physical examination of all patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia is crucial. While the exam is usually normal, it may reveal epigastric tenderness on abdominal palpation. Rebound tenderness, guarding, or evidence of other abnormalities should raise the prospect of alternative diagnoses. GERD, for example, has many symptoms in common with dyspepsia, but is a more likely diagnosis in a patient who has retrosternal burning discomfort and regurgitation and reports that symptoms worsen at night and when lying down.

Lab work has limited value. Although laboratory work is not specifically addressed in the AGA guidelines (except for H pylori testing), a complete blood count is a reasonable part of an initial evaluation of dyspepsia to check for anemia. Other routine blood work is not needed, but further lab testing may be warranted based on the history, exam, and differential diagnosis.

H pylori risk. Because of the association between dyspepsia and H pylori, evaluating the patient’s risk for infection with this bacterium, based primarily on his or her current and previous living conditions (TABLE 1),9 is the next step. Although a test for H pylori could be included in the initial work-up of all patients with dyspepsia, a better—and more cost-effective—strategy is to initially test only those at high risk. (More on testing and treating H pylori in a bit.)

Initiate acid suppression therapy for low-risk patients

First-line treatment for patients with dyspepsia who have no red flags for malignancy or other serious conditions and either are not at high risk for H pylori or are at high risk but have been tested for it and had negative results is a 4- to 8-week course of acid suppression therapy. Patients at low risk for H pylori should be tested for the bacterium only if therapy fails to alleviate their symptoms.9

H2RAs or PPIs? A look at the evidence

In a Cochrane review, both H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were significantly more effective than placebo for treating FD.26 However, H2RAs can lead to tachyphylaxis—an acute decrease in response to a drug—within 2 to 6 weeks, thus limiting their long-term efficacy.27

PPIs appear to be more effective than H2RAs, and are the AGA’s acid suppression drug of choice.11 The CADET study, a randomized controlled trial comparing PPIs (omeprazole 20 mg/d) with an H2RA (ranitidine 150 mg BID) and a prokinetic agent (cisapride 20 mg BID) as well as placebo for dyspepsia, found the PPI to be superior to the H2RA at 6 months.28 In a systematic review, the number needed to treat with PPI therapy for improvement of dyspepsia symptoms was 9.29

There is no specified time limit for the use of PPIs. AGA guidelines recommend that patients who respond to initial therapy stop treatment after 4 to 8 weeks.11 If symptoms recur, another course of the same treatment is justified; if necessary, therapy can continue long term. However, patients should be made aware of the risk for vitamin deficiency, osteoporosis, and fracture, as well as arrhythmias, Clostridium difficile infection, and rebound upon abrupt discontinuation of PPIs.

When to test for H pylori ...

Empiric treatment for H pylori is not recommended. Thus, testing is indicated for patients who have risk factors for the bacterium or who fail to respond to acid suppression therapy. There are various ways to test for the presence of H pylori. Which test you choose depends, in part, on patient-specific factors.

Serology. IgG serology testing is extremely useful in patients who have never been diagnosed with H pylori. It is best suited for those who are currently taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or who recently completed a course of antibiotics, since neither medication affects the results of the serology test.

Serology testing should not be used, however, for any patient who was previously diagnosed with or treated for H pylori, because this type of test cannot distinguish between an active or past infection. The IgG serology test has a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 67%.30

Stool antigen. Stool tests using monoclonal antibodies to detect the presence of H pylori have a sensitivity of 87% to 92% and a specificity of 70%. Stool antigen is also an excellent post-treatment test to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated.31

Stool testing has some drawbacks, however. PPIs can decrease the sensitivity and should be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to stool testing.32 In addition, a stool test for H pylori is not accurate if the patient has an acute GI bleed.

Urea breath testing. This is the most sensitive and specific test for active H pylori infection (90%-96% sensitivity and 88%-96% specificity).33 PPIs can lower the sensitivity of the test, however, and are typically discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Urea breath testing, like stool testing, is an excellent way to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated after treatment. However, it is more expensive than other tests for H pylori and often inconvenient to obtain.13

An EGD is indicated for a patient who has failed to respond to acid suppression therapy and has a negative serology, stool antigen, or urea breath test for H pylori.

Biopsy-based testing for H pylori is performed with EGD and is therefore reserved for patients who have red flags or other indications of a need for invasive testing. There are 3 types of biopsy-based tests: urease (sensitivity, 70%-90%; specificity, 95%); histology (87%-92% and 70%, respectively); and culture (85%-88% and 69%, respectively). Overall, the specificity is slightly better than that of noninvasive testing, but the sensitivity can be lowered by recent use of PPIs, bismuth, or antibiotics.12,34

... and how to treat it

H pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of noncardiac gastric adenocarcinoma, but a decreased risk of cardiac gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma.35,36 Thus, the potential to reduce the risk of gastric cancer is not considered an indication for H pylori treatment. The possibility of improving dyspepsia symptoms is a reason to treat H pylori infection, although eradicating it does not always do so.

In a 2006 Cochrane Review, treating H pylori had a small but statistically significant benefit for patients with FD (NNT=14).37 A 2011 study on the effects of H pylori eradication on symptoms and quality of life in primary care patients with FD revealed a 12.5% improvement in quality of life and a 10.6% improvement in symptoms.38

The triple therapy regimen (a PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin) is the most common first-line H pylori treatment in the United States, and a good initial choice in regions in which clarithromycin resistance is low (TABLE 2).39-44 The standard duration is 7 days. A 2013 Cochrane Review showed that a longer duration (14 days) increased the rate of eradication (82% vs 73%), but this remains controversial.39 The addition of bismuth subsalicylate to the triple therapy regimen has been shown to increase the eradication rate of H pylori by approximately 10%.45 Adding probiotics (saccharomyces or lactobacillus) appears to increase eradication rates, as well.40

Sequential therapy consists of a 5-day course of treatment in which a PPI and amoxicillin are taken twice a day, followed by another 5-day course of a PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole. A recent meta-analysis of sequential therapy showed that it is superior to 7-day triple therapy but equivalent to 14-day triple therapy.40

LOAD (levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline) therapy for 7 to 10 days can be used in place of triple therapy in areas of high resistance or for persistent H pylori. In one study, the H pylori eradication rate for a 7-day course of LOAD therapy—levofloxacin and doxycycline taken once a day, omeprazole before breakfast, and nitazoxanide twice daily—was 90% vs 73.3% for a 7-day course of triple therapy.41

Quadruple therapy has 2 variations: bismuth-based and non-bismuth (concomitant) therapy. The latter uses the base triple therapy and adds either metronidazole or tinidazole for 7 to 14 days. In a multicenter randomized trial, this concomitant therapy was found to have similar efficacy to sequential therapy.42

Bismuth-based quad therapy includes a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline. A meta-analysis found it to have a higher rate of eradication than triple therapy for patients with antibiotic resistance.43,44

For persistent H pylori, a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10 days has been shown to be more effective and better tolerated than quadruple therapy.12

Confirmation is indicated when symptoms persist

If dyspepsia symptoms persist after H pylori treatment, it is reasonable to retest to confirm that the infection has in fact been eradicated. Confirmation is also indicated if the patient has an H pylori-associated ulcer or a prior history of gastric cancer.

Retesting should be performed at least 4 to 6 weeks after treatment is completed. If H pylori has not been eradicated, you can try another regimen. If retesting confirms eradication and symptoms persist, EGD with biopsy is indicated. Although EGD typically has a very low yield, even for patients with red flags, this invasive test often provides reassurance and increased satisfaction for patients with persistent symptoms.46

More options for challenging cases

Managing FD is challenging when both initial acid suppression therapy and H pylori eradication fail. Unproven but low-risk treatments include modification of eating habits (eg, eating slower, not gulping food), reducing stress, discontinuing medications that may be related to symptoms, avoiding foods that seem to exacerbate symptoms, and cutting down or eliminating tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated beverages.8 Bismuth salts have been shown to be superior to placebo for the treatment of dyspepsia.25 Small studies have also demonstrated a favorable risk–benefit ratio for peppermint oil and caraway oil for the treatment of FD.47 Prokinetics have shown efficacy compared with placebo, although a Cochrane review questioned their efficacy based on publication bias.26

There is no good evidence of efficacy for over-the-counter antacids, such as TUMS, or for GI “cocktails” (antacid, antispasmotic, and lidocaine), sucralfate, psychological interventions (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis), or antidepressants.48,49 Several recent randomized controlled trials have shown the efficacy of acupuncture for the treatment of dyspepsia.49,50 Ginger may also be helpful; it has been found to help with nausea in other GI conditions, but it’s uncertain whether it can help patients with dyspepsia.51

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Malone, MD, 845 Fishburn Road, Hershey, PA 17053; [email protected]

1. Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210-2216.

2. Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management guidelines for the millennium. Gut. 2002;50(suppl 4):iv72–iv78.

3. Harmon RC, Peura DA. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:87–98.

4. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1773-1784.

5. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479.

6. Haag S, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Symptom patterns in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: relationship to disturbances in gastric emptying and response to a nutrient challenge in consulters and non-consulters. Gut. 2004;53:1445-1451.

7. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al; European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

8. Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780.

9. Moayyedi P, Axon AT. The usefulness of the likelihood ratio in the diagnosis of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3122-3125.

10. McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604.

11. Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383-1391.

12. Chey WD, Wong BC; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

13. Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Fennerty MB, et al. Can the clinical history distinguish between organic and functional dyspepsia? JAMA. 2006;295:1566-1576.

14. Eslick GD, Howell SC, Hammer J, et al. Empirically derived symptom sub-groups correspond poorly with diagnostic criteria for functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. A factor and cluster analysis of a patient sample. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:133-140.

15. Aro P, Talley NJ, Ronkainen J, et al. Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:94-100.

16. Mertz H, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, et al. Symptoms and visceral perception in severe functional and organic dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:814-822.

17. O’Morain C. Role of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2677-2680.

18. Shmuely H, Obure S, Passaro DJ, et al. Dyspepsia symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infection, Nakuru, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1103-1107.

19. Barbara G, Zecchi L, Barbaro R, et al. Mucosal permeability and immune activation as potential therapeutic targets of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(suppl):S52-S55.

20. Liu NJ, Lee CS, Tang JH, et al. Outcomes of bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e340-e347.

21. Ramsoekh D, van Leerdam ME, Rauws EA, et al. Outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:859-864.

22. Papatheodoridis GV, Sougioultzis S, Archimandritis AJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on peptic ulcer disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:130-142.

23. Bai Y, Li ZS, Zou DW, et al. Alarm features and age for predicting upper gastrointestinal malignancy in Chinese patients with dyspepsia with high background prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and upper gastrointestinal malignancy: an endoscopic database review of 102,665 patients from 1996 to 2006. Gut. 2010;59:722-728.

24. Vakil N. Dyspepsia, peptic ulcer, and H. pylori: a remembrance of things past. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:572-574.

25. Shaheen NJ, Weinberg DS, Denberg TD, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Upper endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:808-816.

26. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001960.

27. Chiu CT, Hsu CM, Wang CC, et al. Randomised clinical trial: sodium alginate oral suspension is non-inferior to omeprazole in the treatment of patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1054-1064.

28. Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Chiba N, Armstrong D, et al. A randomized trial comparing omeprazole, ranitidine, cisapride, or placebo in helicobacter pylori negative, primary care patients with dyspepsia: the CADET-HN Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1477-1488.

29. Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, et al. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329-1337.

30. Garza-González E, Bosques-Padilla FJ, Tijerina-Menchaca R, et al. Comparison of endoscopy-based and serum-based methods for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:101-106.

31. Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, et al. Influence of proton pump inhibitor treatment on Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:44-48.

32. Shimoyama T. Stool antigen tests for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8188-8191.

33. Howden CW, Hunt RH. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ad Hoc Committee on Practice Parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2330-2338.

34. Gisbert J, Abraira V. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:848-863.

35. Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Blaser MJ, et al. Opposing risks of gastric cardiac and noncardia gastric adenocarcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1445-1452.

36. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prevent Res (Phila). 2008;1:329-338.

37. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD002096.

38. Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Francesconi CF, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication in functional dyspepsia: HEROES trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1929-1936.

39. Yuan Y, Ford AC, Khan KJ, et al. Optimum duration of regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD008337.

40. Zou J, Dong J, Yu X. Meta-analysis: Lactobacillus containing quadruple therapy versus standard triple first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14:97-107.

41. Basu PP, Rayapudi K, Pacana T, et al. A randomized study comparing levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline versus triple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1970-1975.

42. Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with 4 drugs are equally effective for eradication of H. pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36–41.

43. Osato R, Reddy R, Reddy SG, et al. Pattern of primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1217-1220.

44. Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple firstline therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:343-357.

45. Hinostroza Morales D, Díaz Ferrer J. Addition of bismuth subsalicylate to triple eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: efficiency and adverse events. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2014;34:315-320.

46. Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Souchek J, et al. Impact of upper endoscopy on satisfaction in patients with previously uninvestigated dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:295-299.

47. Hojo M, Miwa H, Yokoyama T, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with antianxiety or antidepressive agents: systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1036-1042.

48. Soo S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al. Psychological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002301.

49. Lima FA, Ferreira LE, Pace FH. Acupuncture effectiveness as a complementary therapy in functional dyspepsia patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:202-207.

50. Ma TT, Yu SY, Li Y, et al. Randomised clinical trial: an assessment of acupuncture on specific meridian or specific acupoint vs. sham acupuncture for treating functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:552-561.

51. Koretz RL, Rotblatt M. Complementary and alternative medicine in gastroenterology: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:957-967.

› Review the medications taken by patients who suffer from dyspepsia, as many drugs—bisphosphonates, antibiotics, steroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, among others—are associated with this condition. B

› Order an esophagogastroduodenoscopy for patients ages 55 years or older with new-onset dyspepsia and those who have red flags for more serious conditions, eg, a history of upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancer, unintended weight loss, GI bleeding, dysphagia, or a palpable mass. C

› Prescribe acid suppression therapy as first-line treatment for patients who have dyspepsia but are at low risk or have tested negative for Helicobacter pylori infection. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year, an estimated 25% to 30% of the US population suffers from dyspepsia.1 Most self-treat with home remedies and over-the-counter products, but others seek medical care. Dyspepsia accounts for an estimated 2% to 5% of primary care visits annually,2 mostly by patients who are found to have no organic, or structural, cause for their symptoms.1,3

Such patients are said to have functional dyspepsia (FD), a category that applies to about two-thirds of those with dyspepsia.1 A small number of cases are categorized as organic dyspepsia, indicating the presence of a clear structural or anatomic cause, such as an ulcer or mass. The remainder are said to have undifferentiated dyspepsia, which simply means that their signs and symptoms do not rise to the level for which further investigation is warranted and thus it is not known whether it is functional or organic.

There are many possible causes of FD, ranging from medications3,4 to abnormal gastroduodenal motility5,6 to Helicobacter pylori infection,7 and a comprehensive differential diagnosis. The first step in an investigation is to rule out red flags suggestive of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer or other serious disorders.

Patients with FD, like the vast majority of those you’ll treat in a primary care setting, suffer significant morbidity. Most have chronic symptoms, with intermittent flare-ups interspersed with periods of remission.8 In the text and dyspepsia treatment ALGORITHM5,7-12 that follow, you’ll find an evidence-based patient management approach.

Symptoms and causes: What to look for

The primary symptoms of dyspepsia include bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain and burning. To meet the Rome criteria for dyspepsia, these symptoms must have been present for the last 3 months and have had an onset ≥6 months prior to diagnosis.2 Recurrent belching and nausea are also common, but are not included in the Rome diagnostic criteria.

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of the condition, however, and more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.13,14 Indeed, anxiety is a common comorbidity in patients with FD and a risk factor for the diagnosis. Compared with the general public, patients with FD have been found to have higher levels of anxiety, chronic tension, hostility, and hypochondriasis, and a tendency to be more pessimistic.15

Possible causes of FD

While the etiology of organic dyspepsia is clear, the cause of FD is often far more difficult to determine.

Medication use should always be considered, as many types of drugs—including bisphosphonates, antibiotics, narcotics, steroids, iron, metformin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—are associated with dyspepsia.3,4

Gastroduodenal motility and accommodation, which has been found in numerous studies of patients with FD, is a proposed etiology.5,6

Visceral hypersensitivity also appears to play a role. In one study of patients with severe dyspepsia, 87% of those with FD had a reduced or altered GI pain threshold, compared with 20% of those with organic dyspepsia.16

H pylori, commonly linked to peptic ulcer disease (PUD), is also associated with both organic dyspepsia and FD.17,18 The gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium is present in approximately half of the population worldwide, but is more common in developing nations.7H pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) is more prevalent in patients with dyspepsia, particularly in those younger than 30 years of age. The exact mechanism by which H pylori causes non-ulcerative dyspepsia is not clear, but inflammation, dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and alteration of acid secretion have all been proposed.17

Dysfunctional intestinal epithelium is increasingly being considered in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia, among other conditions. Researchers theorize that certain foods, toxins, infections, and/or other stressors lead to changes in the structure and function of tight junctions, resulting in increased intestinal permeability.19 This in turn is thought to allow the outflow of antigens through the leaky epithelium and to stimulate an immune response—a process that may play a role in the increased GI inflammation or hypersensitivity associated with dyspepsia. The “leaky gut” theory may eventually lead to new ways to treat dyspepsia, but thus far, highquality evidence of the efficacy of treatments aimed at this mechanism is lacking.

A range of disorders included in the differential

The primary differential diagnosis for dyspepsia includes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, chronic PUD (including both gastric and duodenal ulcers), and malignancy. The differential may also include biliary disorder, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or other liver disease; chronic abdominal wall pain, irritable bowel syndrome, motility disorders, or infiltrative diseases of the stomach (eosinophilic gastritis, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis); celiac disease and food sensitivities/allergies, including gluten, lactose, and other intolerances; cardiac disease, including acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias; intestinal angina; small intestine bacterial overgrowth; heavy metal toxicity; and hypercalcemia.8

Ulcers are found in approximately 10% of patients undergoing evaluation for dyspepsia.8 Previously, PUD was almost exclusively due to H pylori infection. In developed countries, however, chronic use of NSAIDs, including aspirin, has increased, and is now responsible for most ulcer diseases.20,21 The combination of H pylori infection and NSAID usage appears to be synergistic, with the risk of uncomplicated PUD estimated to be 17.5 times higher among those who test positive for H pylori and take NSAIDs vs a 3- to 4-fold increase in ulcer incidence among those with either of these risk factors alone.22

The work-up starts with a search for red flags

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of dyspepsia; more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.

Evaluation of a patient with dyspepsia begins with a thorough history. Start by determining whether the patient has any red flags, or alarm features, that may be associated with a more serious condition—particularly an underlying malignancy. One or more of the following is an indication for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD):5,8,12

• family and/or personal history of upper GI cancer

• unintended weight loss

• GI bleeding

• progressive dysphagia

• unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

• persistent vomiting

• palpable mass or lymphadenopathy

• jaundice.

While it is important to rule out these red flags, they are poor predictors of malignancy.23,24 With the exception of a single study, their positive predictive value was a mere 1%.8 Their usefulness lies in their ability to exclude malignancy, however; when none of these features is present, the negative predictive value for malignancy is >97%.8

Age is also a risk factor. In addition to red flags, EGD is recommended by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) for patients with new-onset dyspepsia who are 55 years or older—an age at which upper GI malignancy becomes more common. A repeat EGD is rarely indicated, unless Barrett’s esophagus or severe erosive esophagitis is found on the initial EGD.25

Physical exam, H pylori evaluation follow

A physical examination of all patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia is crucial. While the exam is usually normal, it may reveal epigastric tenderness on abdominal palpation. Rebound tenderness, guarding, or evidence of other abnormalities should raise the prospect of alternative diagnoses. GERD, for example, has many symptoms in common with dyspepsia, but is a more likely diagnosis in a patient who has retrosternal burning discomfort and regurgitation and reports that symptoms worsen at night and when lying down.

Lab work has limited value. Although laboratory work is not specifically addressed in the AGA guidelines (except for H pylori testing), a complete blood count is a reasonable part of an initial evaluation of dyspepsia to check for anemia. Other routine blood work is not needed, but further lab testing may be warranted based on the history, exam, and differential diagnosis.

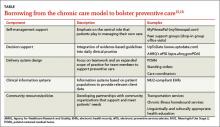

H pylori risk. Because of the association between dyspepsia and H pylori, evaluating the patient’s risk for infection with this bacterium, based primarily on his or her current and previous living conditions (TABLE 1),9 is the next step. Although a test for H pylori could be included in the initial work-up of all patients with dyspepsia, a better—and more cost-effective—strategy is to initially test only those at high risk. (More on testing and treating H pylori in a bit.)

Initiate acid suppression therapy for low-risk patients

First-line treatment for patients with dyspepsia who have no red flags for malignancy or other serious conditions and either are not at high risk for H pylori or are at high risk but have been tested for it and had negative results is a 4- to 8-week course of acid suppression therapy. Patients at low risk for H pylori should be tested for the bacterium only if therapy fails to alleviate their symptoms.9

H2RAs or PPIs? A look at the evidence

In a Cochrane review, both H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were significantly more effective than placebo for treating FD.26 However, H2RAs can lead to tachyphylaxis—an acute decrease in response to a drug—within 2 to 6 weeks, thus limiting their long-term efficacy.27

PPIs appear to be more effective than H2RAs, and are the AGA’s acid suppression drug of choice.11 The CADET study, a randomized controlled trial comparing PPIs (omeprazole 20 mg/d) with an H2RA (ranitidine 150 mg BID) and a prokinetic agent (cisapride 20 mg BID) as well as placebo for dyspepsia, found the PPI to be superior to the H2RA at 6 months.28 In a systematic review, the number needed to treat with PPI therapy for improvement of dyspepsia symptoms was 9.29

There is no specified time limit for the use of PPIs. AGA guidelines recommend that patients who respond to initial therapy stop treatment after 4 to 8 weeks.11 If symptoms recur, another course of the same treatment is justified; if necessary, therapy can continue long term. However, patients should be made aware of the risk for vitamin deficiency, osteoporosis, and fracture, as well as arrhythmias, Clostridium difficile infection, and rebound upon abrupt discontinuation of PPIs.

When to test for H pylori ...

Empiric treatment for H pylori is not recommended. Thus, testing is indicated for patients who have risk factors for the bacterium or who fail to respond to acid suppression therapy. There are various ways to test for the presence of H pylori. Which test you choose depends, in part, on patient-specific factors.

Serology. IgG serology testing is extremely useful in patients who have never been diagnosed with H pylori. It is best suited for those who are currently taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or who recently completed a course of antibiotics, since neither medication affects the results of the serology test.

Serology testing should not be used, however, for any patient who was previously diagnosed with or treated for H pylori, because this type of test cannot distinguish between an active or past infection. The IgG serology test has a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 67%.30

Stool antigen. Stool tests using monoclonal antibodies to detect the presence of H pylori have a sensitivity of 87% to 92% and a specificity of 70%. Stool antigen is also an excellent post-treatment test to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated.31

Stool testing has some drawbacks, however. PPIs can decrease the sensitivity and should be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to stool testing.32 In addition, a stool test for H pylori is not accurate if the patient has an acute GI bleed.

Urea breath testing. This is the most sensitive and specific test for active H pylori infection (90%-96% sensitivity and 88%-96% specificity).33 PPIs can lower the sensitivity of the test, however, and are typically discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Urea breath testing, like stool testing, is an excellent way to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated after treatment. However, it is more expensive than other tests for H pylori and often inconvenient to obtain.13

An EGD is indicated for a patient who has failed to respond to acid suppression therapy and has a negative serology, stool antigen, or urea breath test for H pylori.

Biopsy-based testing for H pylori is performed with EGD and is therefore reserved for patients who have red flags or other indications of a need for invasive testing. There are 3 types of biopsy-based tests: urease (sensitivity, 70%-90%; specificity, 95%); histology (87%-92% and 70%, respectively); and culture (85%-88% and 69%, respectively). Overall, the specificity is slightly better than that of noninvasive testing, but the sensitivity can be lowered by recent use of PPIs, bismuth, or antibiotics.12,34

... and how to treat it

H pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of noncardiac gastric adenocarcinoma, but a decreased risk of cardiac gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma.35,36 Thus, the potential to reduce the risk of gastric cancer is not considered an indication for H pylori treatment. The possibility of improving dyspepsia symptoms is a reason to treat H pylori infection, although eradicating it does not always do so.

In a 2006 Cochrane Review, treating H pylori had a small but statistically significant benefit for patients with FD (NNT=14).37 A 2011 study on the effects of H pylori eradication on symptoms and quality of life in primary care patients with FD revealed a 12.5% improvement in quality of life and a 10.6% improvement in symptoms.38

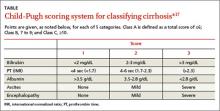

The triple therapy regimen (a PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin) is the most common first-line H pylori treatment in the United States, and a good initial choice in regions in which clarithromycin resistance is low (TABLE 2).39-44 The standard duration is 7 days. A 2013 Cochrane Review showed that a longer duration (14 days) increased the rate of eradication (82% vs 73%), but this remains controversial.39 The addition of bismuth subsalicylate to the triple therapy regimen has been shown to increase the eradication rate of H pylori by approximately 10%.45 Adding probiotics (saccharomyces or lactobacillus) appears to increase eradication rates, as well.40

Sequential therapy consists of a 5-day course of treatment in which a PPI and amoxicillin are taken twice a day, followed by another 5-day course of a PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole. A recent meta-analysis of sequential therapy showed that it is superior to 7-day triple therapy but equivalent to 14-day triple therapy.40

LOAD (levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline) therapy for 7 to 10 days can be used in place of triple therapy in areas of high resistance or for persistent H pylori. In one study, the H pylori eradication rate for a 7-day course of LOAD therapy—levofloxacin and doxycycline taken once a day, omeprazole before breakfast, and nitazoxanide twice daily—was 90% vs 73.3% for a 7-day course of triple therapy.41

Quadruple therapy has 2 variations: bismuth-based and non-bismuth (concomitant) therapy. The latter uses the base triple therapy and adds either metronidazole or tinidazole for 7 to 14 days. In a multicenter randomized trial, this concomitant therapy was found to have similar efficacy to sequential therapy.42

Bismuth-based quad therapy includes a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline. A meta-analysis found it to have a higher rate of eradication than triple therapy for patients with antibiotic resistance.43,44

For persistent H pylori, a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10 days has been shown to be more effective and better tolerated than quadruple therapy.12

Confirmation is indicated when symptoms persist

If dyspepsia symptoms persist after H pylori treatment, it is reasonable to retest to confirm that the infection has in fact been eradicated. Confirmation is also indicated if the patient has an H pylori-associated ulcer or a prior history of gastric cancer.

Retesting should be performed at least 4 to 6 weeks after treatment is completed. If H pylori has not been eradicated, you can try another regimen. If retesting confirms eradication and symptoms persist, EGD with biopsy is indicated. Although EGD typically has a very low yield, even for patients with red flags, this invasive test often provides reassurance and increased satisfaction for patients with persistent symptoms.46

More options for challenging cases

Managing FD is challenging when both initial acid suppression therapy and H pylori eradication fail. Unproven but low-risk treatments include modification of eating habits (eg, eating slower, not gulping food), reducing stress, discontinuing medications that may be related to symptoms, avoiding foods that seem to exacerbate symptoms, and cutting down or eliminating tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated beverages.8 Bismuth salts have been shown to be superior to placebo for the treatment of dyspepsia.25 Small studies have also demonstrated a favorable risk–benefit ratio for peppermint oil and caraway oil for the treatment of FD.47 Prokinetics have shown efficacy compared with placebo, although a Cochrane review questioned their efficacy based on publication bias.26

There is no good evidence of efficacy for over-the-counter antacids, such as TUMS, or for GI “cocktails” (antacid, antispasmotic, and lidocaine), sucralfate, psychological interventions (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis), or antidepressants.48,49 Several recent randomized controlled trials have shown the efficacy of acupuncture for the treatment of dyspepsia.49,50 Ginger may also be helpful; it has been found to help with nausea in other GI conditions, but it’s uncertain whether it can help patients with dyspepsia.51

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Malone, MD, 845 Fishburn Road, Hershey, PA 17053; [email protected]

› Review the medications taken by patients who suffer from dyspepsia, as many drugs—bisphosphonates, antibiotics, steroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, among others—are associated with this condition. B

› Order an esophagogastroduodenoscopy for patients ages 55 years or older with new-onset dyspepsia and those who have red flags for more serious conditions, eg, a history of upper gastrointestinal (GI) cancer, unintended weight loss, GI bleeding, dysphagia, or a palpable mass. C

› Prescribe acid suppression therapy as first-line treatment for patients who have dyspepsia but are at low risk or have tested negative for Helicobacter pylori infection. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year, an estimated 25% to 30% of the US population suffers from dyspepsia.1 Most self-treat with home remedies and over-the-counter products, but others seek medical care. Dyspepsia accounts for an estimated 2% to 5% of primary care visits annually,2 mostly by patients who are found to have no organic, or structural, cause for their symptoms.1,3

Such patients are said to have functional dyspepsia (FD), a category that applies to about two-thirds of those with dyspepsia.1 A small number of cases are categorized as organic dyspepsia, indicating the presence of a clear structural or anatomic cause, such as an ulcer or mass. The remainder are said to have undifferentiated dyspepsia, which simply means that their signs and symptoms do not rise to the level for which further investigation is warranted and thus it is not known whether it is functional or organic.

There are many possible causes of FD, ranging from medications3,4 to abnormal gastroduodenal motility5,6 to Helicobacter pylori infection,7 and a comprehensive differential diagnosis. The first step in an investigation is to rule out red flags suggestive of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer or other serious disorders.

Patients with FD, like the vast majority of those you’ll treat in a primary care setting, suffer significant morbidity. Most have chronic symptoms, with intermittent flare-ups interspersed with periods of remission.8 In the text and dyspepsia treatment ALGORITHM5,7-12 that follow, you’ll find an evidence-based patient management approach.

Symptoms and causes: What to look for

The primary symptoms of dyspepsia include bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain and burning. To meet the Rome criteria for dyspepsia, these symptoms must have been present for the last 3 months and have had an onset ≥6 months prior to diagnosis.2 Recurrent belching and nausea are also common, but are not included in the Rome diagnostic criteria.

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of the condition, however, and more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.13,14 Indeed, anxiety is a common comorbidity in patients with FD and a risk factor for the diagnosis. Compared with the general public, patients with FD have been found to have higher levels of anxiety, chronic tension, hostility, and hypochondriasis, and a tendency to be more pessimistic.15

Possible causes of FD

While the etiology of organic dyspepsia is clear, the cause of FD is often far more difficult to determine.

Medication use should always be considered, as many types of drugs—including bisphosphonates, antibiotics, narcotics, steroids, iron, metformin, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)—are associated with dyspepsia.3,4

Gastroduodenal motility and accommodation, which has been found in numerous studies of patients with FD, is a proposed etiology.5,6

Visceral hypersensitivity also appears to play a role. In one study of patients with severe dyspepsia, 87% of those with FD had a reduced or altered GI pain threshold, compared with 20% of those with organic dyspepsia.16

H pylori, commonly linked to peptic ulcer disease (PUD), is also associated with both organic dyspepsia and FD.17,18 The gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium is present in approximately half of the population worldwide, but is more common in developing nations.7H pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) is more prevalent in patients with dyspepsia, particularly in those younger than 30 years of age. The exact mechanism by which H pylori causes non-ulcerative dyspepsia is not clear, but inflammation, dysmotility, visceral hypersensitivity, and alteration of acid secretion have all been proposed.17

Dysfunctional intestinal epithelium is increasingly being considered in the pathophysiology of dyspepsia, among other conditions. Researchers theorize that certain foods, toxins, infections, and/or other stressors lead to changes in the structure and function of tight junctions, resulting in increased intestinal permeability.19 This in turn is thought to allow the outflow of antigens through the leaky epithelium and to stimulate an immune response—a process that may play a role in the increased GI inflammation or hypersensitivity associated with dyspepsia. The “leaky gut” theory may eventually lead to new ways to treat dyspepsia, but thus far, highquality evidence of the efficacy of treatments aimed at this mechanism is lacking.

A range of disorders included in the differential

The primary differential diagnosis for dyspepsia includes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), esophagitis, chronic PUD (including both gastric and duodenal ulcers), and malignancy. The differential may also include biliary disorder, pancreatitis, hepatitis, or other liver disease; chronic abdominal wall pain, irritable bowel syndrome, motility disorders, or infiltrative diseases of the stomach (eosinophilic gastritis, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis); celiac disease and food sensitivities/allergies, including gluten, lactose, and other intolerances; cardiac disease, including acute coronary syndrome, myocardial infarction, and arrhythmias; intestinal angina; small intestine bacterial overgrowth; heavy metal toxicity; and hypercalcemia.8

Ulcers are found in approximately 10% of patients undergoing evaluation for dyspepsia.8 Previously, PUD was almost exclusively due to H pylori infection. In developed countries, however, chronic use of NSAIDs, including aspirin, has increased, and is now responsible for most ulcer diseases.20,21 The combination of H pylori infection and NSAID usage appears to be synergistic, with the risk of uncomplicated PUD estimated to be 17.5 times higher among those who test positive for H pylori and take NSAIDs vs a 3- to 4-fold increase in ulcer incidence among those with either of these risk factors alone.22

The work-up starts with a search for red flags

Symptom severity is a poor predictor of the seriousness of dyspepsia; more intense symptoms are no more likely than milder cases to have an organic cause.

Evaluation of a patient with dyspepsia begins with a thorough history. Start by determining whether the patient has any red flags, or alarm features, that may be associated with a more serious condition—particularly an underlying malignancy. One or more of the following is an indication for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD):5,8,12

• family and/or personal history of upper GI cancer

• unintended weight loss

• GI bleeding

• progressive dysphagia

• unexplained iron-deficiency anemia

• persistent vomiting

• palpable mass or lymphadenopathy

• jaundice.

While it is important to rule out these red flags, they are poor predictors of malignancy.23,24 With the exception of a single study, their positive predictive value was a mere 1%.8 Their usefulness lies in their ability to exclude malignancy, however; when none of these features is present, the negative predictive value for malignancy is >97%.8

Age is also a risk factor. In addition to red flags, EGD is recommended by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) for patients with new-onset dyspepsia who are 55 years or older—an age at which upper GI malignancy becomes more common. A repeat EGD is rarely indicated, unless Barrett’s esophagus or severe erosive esophagitis is found on the initial EGD.25

Physical exam, H pylori evaluation follow

A physical examination of all patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia is crucial. While the exam is usually normal, it may reveal epigastric tenderness on abdominal palpation. Rebound tenderness, guarding, or evidence of other abnormalities should raise the prospect of alternative diagnoses. GERD, for example, has many symptoms in common with dyspepsia, but is a more likely diagnosis in a patient who has retrosternal burning discomfort and regurgitation and reports that symptoms worsen at night and when lying down.

Lab work has limited value. Although laboratory work is not specifically addressed in the AGA guidelines (except for H pylori testing), a complete blood count is a reasonable part of an initial evaluation of dyspepsia to check for anemia. Other routine blood work is not needed, but further lab testing may be warranted based on the history, exam, and differential diagnosis.

H pylori risk. Because of the association between dyspepsia and H pylori, evaluating the patient’s risk for infection with this bacterium, based primarily on his or her current and previous living conditions (TABLE 1),9 is the next step. Although a test for H pylori could be included in the initial work-up of all patients with dyspepsia, a better—and more cost-effective—strategy is to initially test only those at high risk. (More on testing and treating H pylori in a bit.)

Initiate acid suppression therapy for low-risk patients

First-line treatment for patients with dyspepsia who have no red flags for malignancy or other serious conditions and either are not at high risk for H pylori or are at high risk but have been tested for it and had negative results is a 4- to 8-week course of acid suppression therapy. Patients at low risk for H pylori should be tested for the bacterium only if therapy fails to alleviate their symptoms.9

H2RAs or PPIs? A look at the evidence

In a Cochrane review, both H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) were significantly more effective than placebo for treating FD.26 However, H2RAs can lead to tachyphylaxis—an acute decrease in response to a drug—within 2 to 6 weeks, thus limiting their long-term efficacy.27

PPIs appear to be more effective than H2RAs, and are the AGA’s acid suppression drug of choice.11 The CADET study, a randomized controlled trial comparing PPIs (omeprazole 20 mg/d) with an H2RA (ranitidine 150 mg BID) and a prokinetic agent (cisapride 20 mg BID) as well as placebo for dyspepsia, found the PPI to be superior to the H2RA at 6 months.28 In a systematic review, the number needed to treat with PPI therapy for improvement of dyspepsia symptoms was 9.29

There is no specified time limit for the use of PPIs. AGA guidelines recommend that patients who respond to initial therapy stop treatment after 4 to 8 weeks.11 If symptoms recur, another course of the same treatment is justified; if necessary, therapy can continue long term. However, patients should be made aware of the risk for vitamin deficiency, osteoporosis, and fracture, as well as arrhythmias, Clostridium difficile infection, and rebound upon abrupt discontinuation of PPIs.

When to test for H pylori ...

Empiric treatment for H pylori is not recommended. Thus, testing is indicated for patients who have risk factors for the bacterium or who fail to respond to acid suppression therapy. There are various ways to test for the presence of H pylori. Which test you choose depends, in part, on patient-specific factors.

Serology. IgG serology testing is extremely useful in patients who have never been diagnosed with H pylori. It is best suited for those who are currently taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or who recently completed a course of antibiotics, since neither medication affects the results of the serology test.

Serology testing should not be used, however, for any patient who was previously diagnosed with or treated for H pylori, because this type of test cannot distinguish between an active or past infection. The IgG serology test has a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 67%.30

Stool antigen. Stool tests using monoclonal antibodies to detect the presence of H pylori have a sensitivity of 87% to 92% and a specificity of 70%. Stool antigen is also an excellent post-treatment test to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated.31

Stool testing has some drawbacks, however. PPIs can decrease the sensitivity and should be discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to stool testing.32 In addition, a stool test for H pylori is not accurate if the patient has an acute GI bleed.

Urea breath testing. This is the most sensitive and specific test for active H pylori infection (90%-96% sensitivity and 88%-96% specificity).33 PPIs can lower the sensitivity of the test, however, and are typically discontinued at least 2 weeks prior to testing. Urea breath testing, like stool testing, is an excellent way to confirm that H pylori has been eradicated after treatment. However, it is more expensive than other tests for H pylori and often inconvenient to obtain.13

An EGD is indicated for a patient who has failed to respond to acid suppression therapy and has a negative serology, stool antigen, or urea breath test for H pylori.

Biopsy-based testing for H pylori is performed with EGD and is therefore reserved for patients who have red flags or other indications of a need for invasive testing. There are 3 types of biopsy-based tests: urease (sensitivity, 70%-90%; specificity, 95%); histology (87%-92% and 70%, respectively); and culture (85%-88% and 69%, respectively). Overall, the specificity is slightly better than that of noninvasive testing, but the sensitivity can be lowered by recent use of PPIs, bismuth, or antibiotics.12,34

... and how to treat it

H pylori infection is associated with an increased risk of noncardiac gastric adenocarcinoma, but a decreased risk of cardiac gastric adenocarcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma.35,36 Thus, the potential to reduce the risk of gastric cancer is not considered an indication for H pylori treatment. The possibility of improving dyspepsia symptoms is a reason to treat H pylori infection, although eradicating it does not always do so.

In a 2006 Cochrane Review, treating H pylori had a small but statistically significant benefit for patients with FD (NNT=14).37 A 2011 study on the effects of H pylori eradication on symptoms and quality of life in primary care patients with FD revealed a 12.5% improvement in quality of life and a 10.6% improvement in symptoms.38

The triple therapy regimen (a PPI + amoxicillin + clarithromycin) is the most common first-line H pylori treatment in the United States, and a good initial choice in regions in which clarithromycin resistance is low (TABLE 2).39-44 The standard duration is 7 days. A 2013 Cochrane Review showed that a longer duration (14 days) increased the rate of eradication (82% vs 73%), but this remains controversial.39 The addition of bismuth subsalicylate to the triple therapy regimen has been shown to increase the eradication rate of H pylori by approximately 10%.45 Adding probiotics (saccharomyces or lactobacillus) appears to increase eradication rates, as well.40

Sequential therapy consists of a 5-day course of treatment in which a PPI and amoxicillin are taken twice a day, followed by another 5-day course of a PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole. A recent meta-analysis of sequential therapy showed that it is superior to 7-day triple therapy but equivalent to 14-day triple therapy.40

LOAD (levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline) therapy for 7 to 10 days can be used in place of triple therapy in areas of high resistance or for persistent H pylori. In one study, the H pylori eradication rate for a 7-day course of LOAD therapy—levofloxacin and doxycycline taken once a day, omeprazole before breakfast, and nitazoxanide twice daily—was 90% vs 73.3% for a 7-day course of triple therapy.41

Quadruple therapy has 2 variations: bismuth-based and non-bismuth (concomitant) therapy. The latter uses the base triple therapy and adds either metronidazole or tinidazole for 7 to 14 days. In a multicenter randomized trial, this concomitant therapy was found to have similar efficacy to sequential therapy.42

Bismuth-based quad therapy includes a PPI, bismuth, metronidazole, and tetracycline. A meta-analysis found it to have a higher rate of eradication than triple therapy for patients with antibiotic resistance.43,44

For persistent H pylori, a PPI, levofloxacin, and amoxicillin for 10 days has been shown to be more effective and better tolerated than quadruple therapy.12

Confirmation is indicated when symptoms persist

If dyspepsia symptoms persist after H pylori treatment, it is reasonable to retest to confirm that the infection has in fact been eradicated. Confirmation is also indicated if the patient has an H pylori-associated ulcer or a prior history of gastric cancer.

Retesting should be performed at least 4 to 6 weeks after treatment is completed. If H pylori has not been eradicated, you can try another regimen. If retesting confirms eradication and symptoms persist, EGD with biopsy is indicated. Although EGD typically has a very low yield, even for patients with red flags, this invasive test often provides reassurance and increased satisfaction for patients with persistent symptoms.46

More options for challenging cases

Managing FD is challenging when both initial acid suppression therapy and H pylori eradication fail. Unproven but low-risk treatments include modification of eating habits (eg, eating slower, not gulping food), reducing stress, discontinuing medications that may be related to symptoms, avoiding foods that seem to exacerbate symptoms, and cutting down or eliminating tobacco, caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated beverages.8 Bismuth salts have been shown to be superior to placebo for the treatment of dyspepsia.25 Small studies have also demonstrated a favorable risk–benefit ratio for peppermint oil and caraway oil for the treatment of FD.47 Prokinetics have shown efficacy compared with placebo, although a Cochrane review questioned their efficacy based on publication bias.26

There is no good evidence of efficacy for over-the-counter antacids, such as TUMS, or for GI “cocktails” (antacid, antispasmotic, and lidocaine), sucralfate, psychological interventions (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis), or antidepressants.48,49 Several recent randomized controlled trials have shown the efficacy of acupuncture for the treatment of dyspepsia.49,50 Ginger may also be helpful; it has been found to help with nausea in other GI conditions, but it’s uncertain whether it can help patients with dyspepsia.51

CORRESPONDENCE

Michael Malone, MD, 845 Fishburn Road, Hershey, PA 17053; [email protected]

1. Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210-2216.

2. Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management guidelines for the millennium. Gut. 2002;50(suppl 4):iv72–iv78.

3. Harmon RC, Peura DA. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:87–98.

4. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1773-1784.

5. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479.

6. Haag S, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Symptom patterns in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: relationship to disturbances in gastric emptying and response to a nutrient challenge in consulters and non-consulters. Gut. 2004;53:1445-1451.

7. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al; European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

8. Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780.

9. Moayyedi P, Axon AT. The usefulness of the likelihood ratio in the diagnosis of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3122-3125.

10. McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604.

11. Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383-1391.

12. Chey WD, Wong BC; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

13. Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Fennerty MB, et al. Can the clinical history distinguish between organic and functional dyspepsia? JAMA. 2006;295:1566-1576.

14. Eslick GD, Howell SC, Hammer J, et al. Empirically derived symptom sub-groups correspond poorly with diagnostic criteria for functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. A factor and cluster analysis of a patient sample. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:133-140.

15. Aro P, Talley NJ, Ronkainen J, et al. Anxiety is associated with uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) in a Swedish population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:94-100.

16. Mertz H, Fullerton S, Naliboff B, et al. Symptoms and visceral perception in severe functional and organic dyspepsia. Gut. 1998;42:814-822.

17. O’Morain C. Role of Helicobacter pylori in functional dyspepsia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2677-2680.

18. Shmuely H, Obure S, Passaro DJ, et al. Dyspepsia symptoms and Helicobacter pylori infection, Nakuru, Kenya. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1103-1107.

19. Barbara G, Zecchi L, Barbaro R, et al. Mucosal permeability and immune activation as potential therapeutic targets of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46(suppl):S52-S55.

20. Liu NJ, Lee CS, Tang JH, et al. Outcomes of bleeding peptic ulcers: a prospective study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e340-e347.

21. Ramsoekh D, van Leerdam ME, Rauws EA, et al. Outcome of peptic ulcer bleeding, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:859-864.

22. Papatheodoridis GV, Sougioultzis S, Archimandritis AJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on peptic ulcer disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:130-142.

23. Bai Y, Li ZS, Zou DW, et al. Alarm features and age for predicting upper gastrointestinal malignancy in Chinese patients with dyspepsia with high background prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection and upper gastrointestinal malignancy: an endoscopic database review of 102,665 patients from 1996 to 2006. Gut. 2010;59:722-728.

24. Vakil N. Dyspepsia, peptic ulcer, and H. pylori: a remembrance of things past. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:572-574.

25. Shaheen NJ, Weinberg DS, Denberg TD, et al; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Upper endoscopy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: best practice advice from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:808-816.

26. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(4):CD001960.

27. Chiu CT, Hsu CM, Wang CC, et al. Randomised clinical trial: sodium alginate oral suspension is non-inferior to omeprazole in the treatment of patients with non-erosive gastroesophageal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:1054-1064.

28. Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Chiba N, Armstrong D, et al. A randomized trial comparing omeprazole, ranitidine, cisapride, or placebo in helicobacter pylori negative, primary care patients with dyspepsia: the CADET-HN Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1477-1488.

29. Moayyedi P, Delaney BC, Vakil N, et al. The efficacy of proton pump inhibitors in nonulcer dyspepsia: a systematic review and economic analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1329-1337.

30. Garza-González E, Bosques-Padilla FJ, Tijerina-Menchaca R, et al. Comparison of endoscopy-based and serum-based methods for the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17:101-106.

31. Kodama M, Murakami K, Okimoto T, et al. Influence of proton pump inhibitor treatment on Helicobacter pylori stool antigen test. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:44-48.

32. Shimoyama T. Stool antigen tests for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:8188-8191.

33. Howden CW, Hunt RH. Guidelines for the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Ad Hoc Committee on Practice Parameters of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2330-2338.

34. Gisbert J, Abraira V. Accuracy of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic tests in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:848-863.

35. Kamangar F, Dawsey SM, Blaser MJ, et al. Opposing risks of gastric cardiac and noncardia gastric adenocarcinomas associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1445-1452.

36. Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prevent Res (Phila). 2008;1:329-338.

37. Moayyedi P, Soo S, Deeks J, et al. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD002096.

38. Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Francesconi CF, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication in functional dyspepsia: HEROES trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1929-1936.

39. Yuan Y, Ford AC, Khan KJ, et al. Optimum duration of regimens for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD008337.

40. Zou J, Dong J, Yu X. Meta-analysis: Lactobacillus containing quadruple therapy versus standard triple first-line therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2009;14:97-107.

41. Basu PP, Rayapudi K, Pacana T, et al. A randomized study comparing levofloxacin, omeprazole, nitazoxanide, and doxycycline versus triple therapy for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1970-1975.

42. Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy with 4 drugs are equally effective for eradication of H. pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36–41.

43. Osato R, Reddy R, Reddy SG, et al. Pattern of primary resistance of Helicobacter pylori to metronidazole or clarithromycin in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1217-1220.

44. Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple firstline therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:343-357.

45. Hinostroza Morales D, Díaz Ferrer J. Addition of bismuth subsalicylate to triple eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: efficiency and adverse events. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2014;34:315-320.

46. Rabeneck L, Wristers K, Souchek J, et al. Impact of upper endoscopy on satisfaction in patients with previously uninvestigated dyspepsia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:295-299.

47. Hojo M, Miwa H, Yokoyama T, et al. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with antianxiety or antidepressive agents: systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1036-1042.

48. Soo S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al. Psychological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD002301.

49. Lima FA, Ferreira LE, Pace FH. Acupuncture effectiveness as a complementary therapy in functional dyspepsia patients. Arq Gastroenterol. 2013;50:202-207.

50. Ma TT, Yu SY, Li Y, et al. Randomised clinical trial: an assessment of acupuncture on specific meridian or specific acupoint vs. sham acupuncture for treating functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:552-561.

51. Koretz RL, Rotblatt M. Complementary and alternative medicine in gastroenterology: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:957-967.

1. Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210-2216.

2. Talley NJ. Dyspepsia: management guidelines for the millennium. Gut. 2002;50(suppl 4):iv72–iv78.

3. Harmon RC, Peura DA. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:87–98.

4. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60:1773-1784.

5. Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466-1479.

6. Haag S, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Symptom patterns in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: relationship to disturbances in gastric emptying and response to a nutrient challenge in consulters and non-consulters. Gut. 2004;53:1445-1451.

7. Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al; European Helicobacter Study Group. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection—the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664.

8. Talley NJ, Vakil NB, Moayyedi P. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the evaluation of dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:1756-1780.

9. Moayyedi P, Axon AT. The usefulness of the likelihood ratio in the diagnosis of dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3122-3125.

10. McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604.

11. Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, et al; American Gastroenterological Association. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383-1391.

12. Chey WD, Wong BC; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

13. Moayyedi P, Talley NJ, Fennerty MB, et al. Can the clinical history distinguish between organic and functional dyspepsia? JAMA. 2006;295:1566-1576.