User login

COPD in Primary Care

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Unexplained leukocytosis in a hospitalized patient

A 70-year-old man is evaluated for a persistent leukocytosis. He was hospitalized 10 days ago for a severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was intubated for 3 days, was diagnosed with a left lower lobe pneumonia, and was treated with antibiotics. His white blood cell count on admission was 20,000 per mcL. It dropped as low as 15,000 on day 6 but is now 25,000, with 23,000 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (10% band forms). He is on oral prednisone 15 mg once daily. Chest x-ray shows no infiltrate. Urinalysis without WBCs.

What is the most likely cause of his leukocytosis?

A) Pulmonary embolus.

B) Lung abscess.

C) Perinephric abscess.

D) Prednisone.

E) Clostridium difficile infection.

The most likely diagnosis in otherwise unexplained leukocytosis in a hospitalized patient is C. difficile.

Anna Wanahita, MD, of the St. John Clinic in Tulsa, Okla., and her colleagues prospectively studied 60 patients admitted to a VA hospital who had unexplained leukocytosis.1 All patients had stool specimens sent for C. difficile toxin; in addition, 26 hospitalized control patients without leukocytosis also had stool sent for C. difficile toxin. For study purposes, leukocytosis was defined as a WBC greater than 15,000 per mcL. Any patient for whom C. difficile toxin was sent because of clinical suspicion and who was positive was excluded from the study results.

Almost 60% of the patients with unexplained leukocytosis (35 of 60) had a positive C. difficile toxin, compared with 12% of the controls (P less than .001). More than half of the patients with a positive C. difficile test had the onset of leukocytosis prior to any symptoms of colitis. Leukocytosis responded to treatment with metronidazole in 83% of the patients with a positive C. difficile toxin, and 75% of the patients who had leukocytosis did not have a positive C. difficile toxin.

In another study, Mamatha Bulusu, and colleagues did a retrospective study of 70 hospitalized patients who had diarrhea and underwent testing for C. difficile.2 They evaluated the pattern of white blood cell counts in patients who were positive and negative for C. difficile toxin. The mean WBC for C. difficile–positive patients was 15,800, compared with 7,700 for the patients who were C. difficile negative (P less than .01). They described three patterns: one in which leukocytosis occurred at the onset of diarrhea; a pattern in which unexplained leukocytosis occurred days prior to diarrhea; and a pattern in which patients treated for infection with leukocytosis had a worsening of their leukocytosis at the onset of diarrheal symptoms. Treatment with metronidazole led to a resolution of leukocytosis in all the C. difficile–positive patients.

Another possibility in this case was WBC elevation because of the patient’s prednisone. Prednisone can increase WBC as early as the first day of therapy.3 The elevation and rapidity of increase are dose related. The important pearl is that steroid-induced leukocytosis involves an increase of polymorphonuclear white blood cells with a rise in monocytes and a decrease in eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Pearl: Think of underlying C. difficile infection in your hospitalized patient with unexplained leukocytosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Med. 2003 Nov;115(7):543-6.

2. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Nov;95(11):3137-41.

3. J Clin Invest. 1975 Oct;56(4):808-13.

4. Am J Med. 1981 Nov;71(5):773-8.

A 70-year-old man is evaluated for a persistent leukocytosis. He was hospitalized 10 days ago for a severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was intubated for 3 days, was diagnosed with a left lower lobe pneumonia, and was treated with antibiotics. His white blood cell count on admission was 20,000 per mcL. It dropped as low as 15,000 on day 6 but is now 25,000, with 23,000 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (10% band forms). He is on oral prednisone 15 mg once daily. Chest x-ray shows no infiltrate. Urinalysis without WBCs.

What is the most likely cause of his leukocytosis?

A) Pulmonary embolus.

B) Lung abscess.

C) Perinephric abscess.

D) Prednisone.

E) Clostridium difficile infection.

The most likely diagnosis in otherwise unexplained leukocytosis in a hospitalized patient is C. difficile.

Anna Wanahita, MD, of the St. John Clinic in Tulsa, Okla., and her colleagues prospectively studied 60 patients admitted to a VA hospital who had unexplained leukocytosis.1 All patients had stool specimens sent for C. difficile toxin; in addition, 26 hospitalized control patients without leukocytosis also had stool sent for C. difficile toxin. For study purposes, leukocytosis was defined as a WBC greater than 15,000 per mcL. Any patient for whom C. difficile toxin was sent because of clinical suspicion and who was positive was excluded from the study results.

Almost 60% of the patients with unexplained leukocytosis (35 of 60) had a positive C. difficile toxin, compared with 12% of the controls (P less than .001). More than half of the patients with a positive C. difficile test had the onset of leukocytosis prior to any symptoms of colitis. Leukocytosis responded to treatment with metronidazole in 83% of the patients with a positive C. difficile toxin, and 75% of the patients who had leukocytosis did not have a positive C. difficile toxin.

In another study, Mamatha Bulusu, and colleagues did a retrospective study of 70 hospitalized patients who had diarrhea and underwent testing for C. difficile.2 They evaluated the pattern of white blood cell counts in patients who were positive and negative for C. difficile toxin. The mean WBC for C. difficile–positive patients was 15,800, compared with 7,700 for the patients who were C. difficile negative (P less than .01). They described three patterns: one in which leukocytosis occurred at the onset of diarrhea; a pattern in which unexplained leukocytosis occurred days prior to diarrhea; and a pattern in which patients treated for infection with leukocytosis had a worsening of their leukocytosis at the onset of diarrheal symptoms. Treatment with metronidazole led to a resolution of leukocytosis in all the C. difficile–positive patients.

Another possibility in this case was WBC elevation because of the patient’s prednisone. Prednisone can increase WBC as early as the first day of therapy.3 The elevation and rapidity of increase are dose related. The important pearl is that steroid-induced leukocytosis involves an increase of polymorphonuclear white blood cells with a rise in monocytes and a decrease in eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Pearl: Think of underlying C. difficile infection in your hospitalized patient with unexplained leukocytosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Med. 2003 Nov;115(7):543-6.

2. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Nov;95(11):3137-41.

3. J Clin Invest. 1975 Oct;56(4):808-13.

4. Am J Med. 1981 Nov;71(5):773-8.

A 70-year-old man is evaluated for a persistent leukocytosis. He was hospitalized 10 days ago for a severe exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He was intubated for 3 days, was diagnosed with a left lower lobe pneumonia, and was treated with antibiotics. His white blood cell count on admission was 20,000 per mcL. It dropped as low as 15,000 on day 6 but is now 25,000, with 23,000 polymorphonuclear leukocytes (10% band forms). He is on oral prednisone 15 mg once daily. Chest x-ray shows no infiltrate. Urinalysis without WBCs.

What is the most likely cause of his leukocytosis?

A) Pulmonary embolus.

B) Lung abscess.

C) Perinephric abscess.

D) Prednisone.

E) Clostridium difficile infection.

The most likely diagnosis in otherwise unexplained leukocytosis in a hospitalized patient is C. difficile.

Anna Wanahita, MD, of the St. John Clinic in Tulsa, Okla., and her colleagues prospectively studied 60 patients admitted to a VA hospital who had unexplained leukocytosis.1 All patients had stool specimens sent for C. difficile toxin; in addition, 26 hospitalized control patients without leukocytosis also had stool sent for C. difficile toxin. For study purposes, leukocytosis was defined as a WBC greater than 15,000 per mcL. Any patient for whom C. difficile toxin was sent because of clinical suspicion and who was positive was excluded from the study results.

Almost 60% of the patients with unexplained leukocytosis (35 of 60) had a positive C. difficile toxin, compared with 12% of the controls (P less than .001). More than half of the patients with a positive C. difficile test had the onset of leukocytosis prior to any symptoms of colitis. Leukocytosis responded to treatment with metronidazole in 83% of the patients with a positive C. difficile toxin, and 75% of the patients who had leukocytosis did not have a positive C. difficile toxin.

In another study, Mamatha Bulusu, and colleagues did a retrospective study of 70 hospitalized patients who had diarrhea and underwent testing for C. difficile.2 They evaluated the pattern of white blood cell counts in patients who were positive and negative for C. difficile toxin. The mean WBC for C. difficile–positive patients was 15,800, compared with 7,700 for the patients who were C. difficile negative (P less than .01). They described three patterns: one in which leukocytosis occurred at the onset of diarrhea; a pattern in which unexplained leukocytosis occurred days prior to diarrhea; and a pattern in which patients treated for infection with leukocytosis had a worsening of their leukocytosis at the onset of diarrheal symptoms. Treatment with metronidazole led to a resolution of leukocytosis in all the C. difficile–positive patients.

Another possibility in this case was WBC elevation because of the patient’s prednisone. Prednisone can increase WBC as early as the first day of therapy.3 The elevation and rapidity of increase are dose related. The important pearl is that steroid-induced leukocytosis involves an increase of polymorphonuclear white blood cells with a rise in monocytes and a decrease in eosinophils and lymphocytes.

Pearl: Think of underlying C. difficile infection in your hospitalized patient with unexplained leukocytosis.

Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and he serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Am J Med. 2003 Nov;115(7):543-6.

2. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000 Nov;95(11):3137-41.

3. J Clin Invest. 1975 Oct;56(4):808-13.

4. Am J Med. 1981 Nov;71(5):773-8.

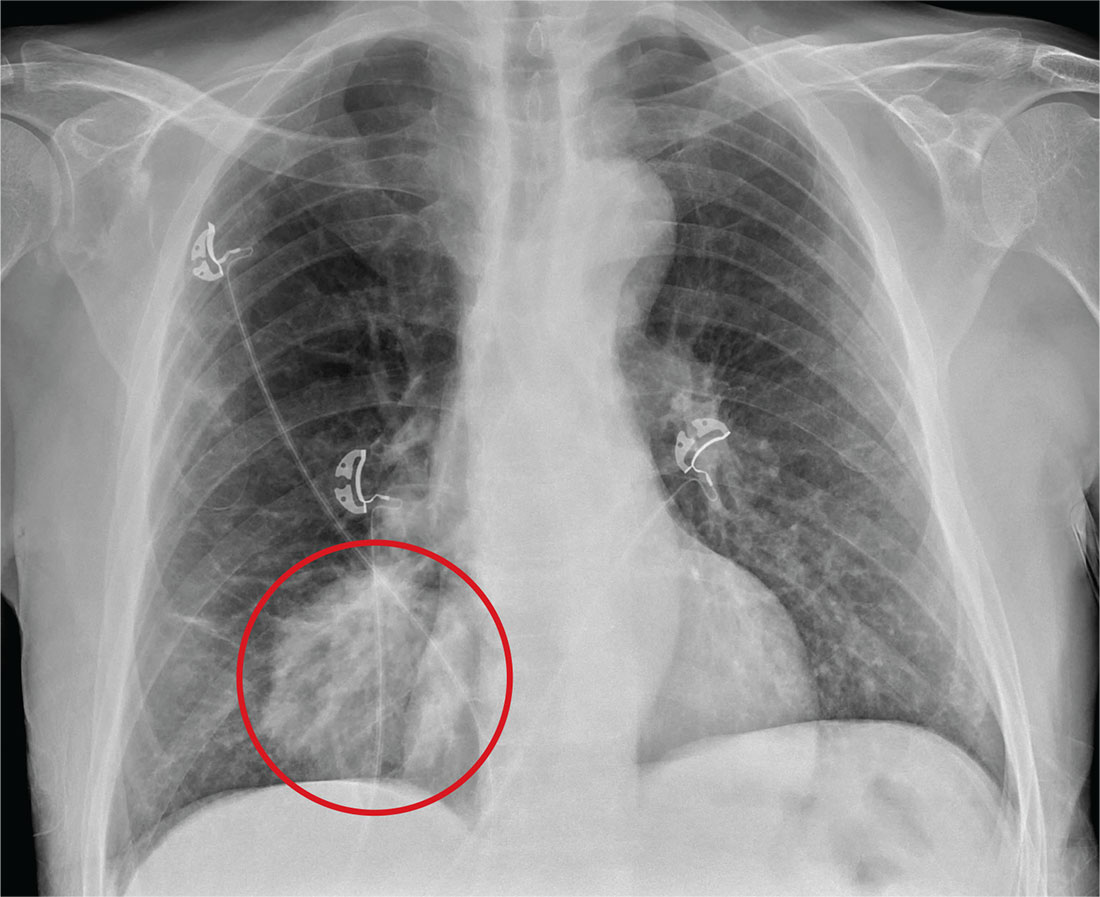

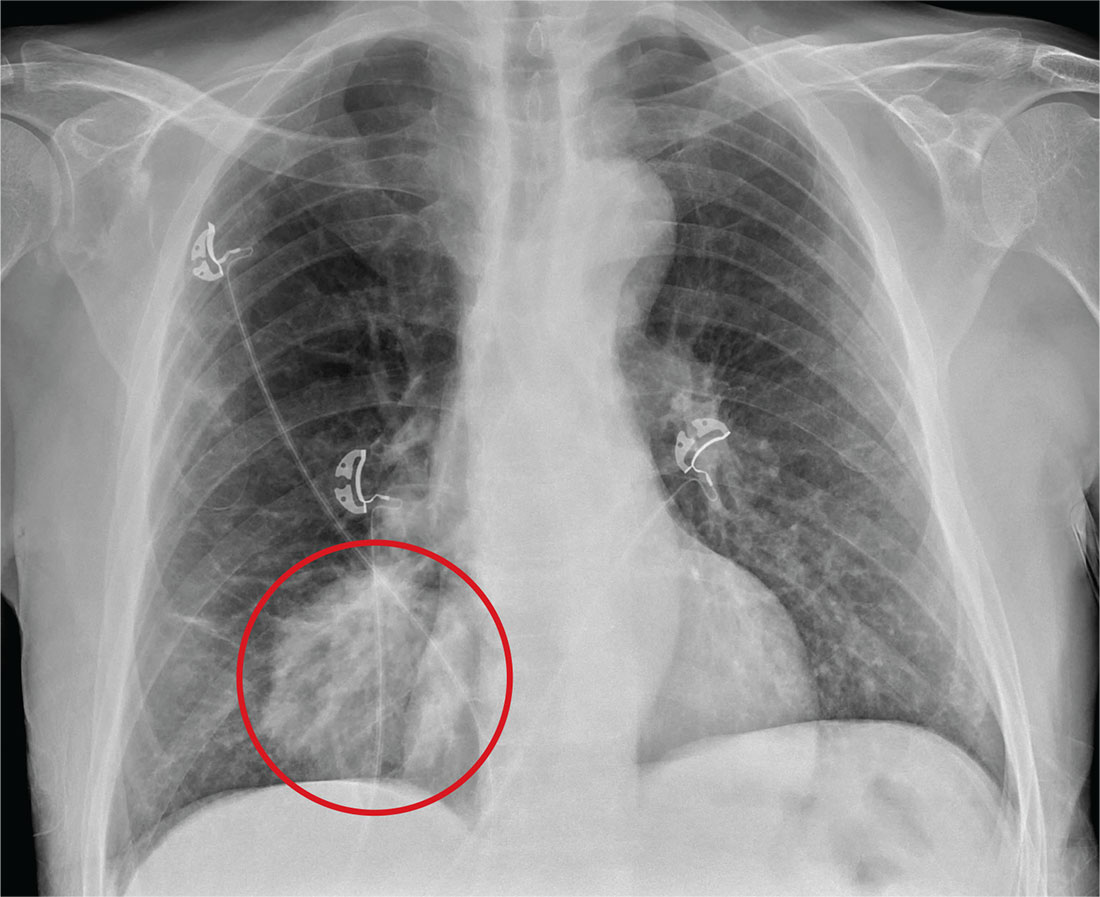

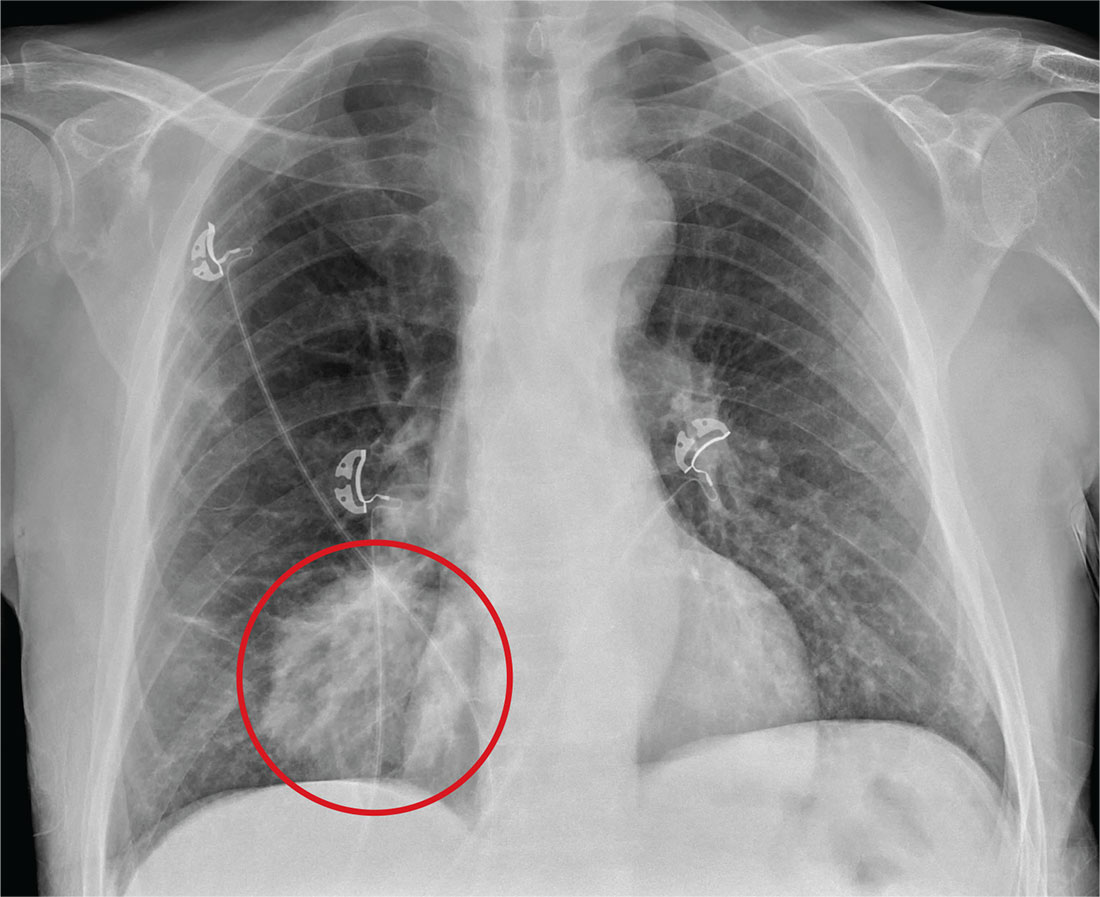

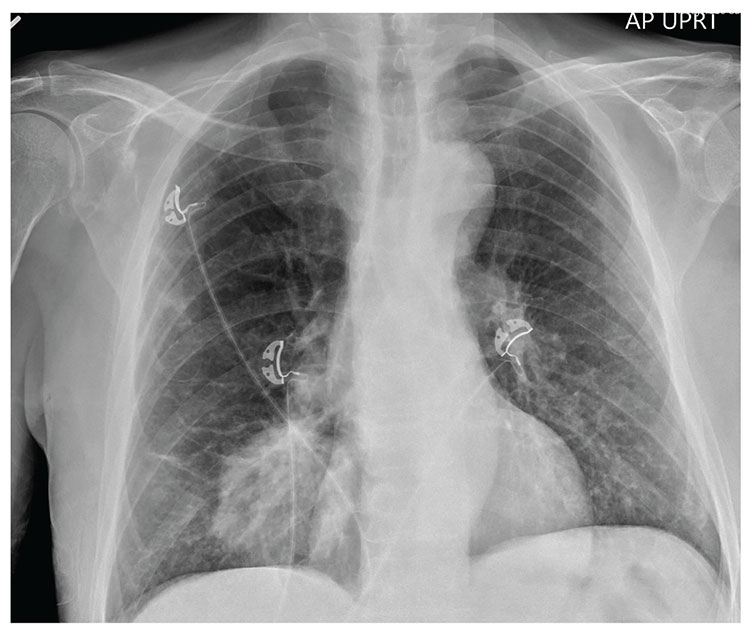

The Signs That Can’t Be Ignored

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a large, round hyperdensity within the right lower lobe. This lesion is highly concerning for malignancy and warrants further work-up.

With his gastrointestinal bleed and hypercoagulability from warfarin toxicity, the patient required admission anyway. Subsequent biopsy confirmed the presence of a primary lung carcinoma.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a large, round hyperdensity within the right lower lobe. This lesion is highly concerning for malignancy and warrants further work-up.

With his gastrointestinal bleed and hypercoagulability from warfarin toxicity, the patient required admission anyway. Subsequent biopsy confirmed the presence of a primary lung carcinoma.

ANSWER

The radiograph shows a large, round hyperdensity within the right lower lobe. This lesion is highly concerning for malignancy and warrants further work-up.

With his gastrointestinal bleed and hypercoagulability from warfarin toxicity, the patient required admission anyway. Subsequent biopsy confirmed the presence of a primary lung carcinoma.

For several days, a 60-year-old man has been feeling weak. He has also noticed that he bruises easily, and he’s experienced black, tarry stools and episodic hemoptysis. He presents to the emergency department, where the triage team sends him for further evaluation.

The patient’s history is significant for a remote diagnosis of a deep venous thrombosis in one of his lower extremities, for which he takes warfarin. He does not recall his most recent INR level. He reports smoking up to one pack of cigarettes per day and consuming alcohol regularly.

Examination reveals an older appearing male in no obvious distress. His blood pressure is 90/60 mm Hg, and his heart rate is 110 beats/min. You note bruises on both arms. The rest of his physical exam is normal. Lung sounds are clear.

Labwork ordered by the triage team indicates a hemoglobin level of 8 g/dL and an INR of 9. In addition, his stool guaiac test came back positive.

You obtain a portable chest radiograph (shown). What is your impression?

Evidence for medical marijuana largely up in smoke

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Despite the popularity of medical marijuana, robust evidence for its use is limited or nonexistent for most medical conditions.

“This is a tough subject to study,” Ellie Grossman, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “There is federal money that can only be used in very limited ways to study it. Our science is way behind the times in terms of what our patients are doing and using.”

Typical limitations of marijuana studies include self-report of quantity/duration used and the fact that biochemical/quantifiable measures are lacking. “For inhaled marijuana, there is variability in how much is inhaled and how deeply it’s being inhaled,” said Dr. Grossman, an internist who practices in Somerville, Mass.

Then there’s the issue of recall bias and the question as to whether oral cannabinoids equate to the plant-derived forms of medical marijuana that patients obtain from their local dispensaries.

That matters, because the majority of published studies on the topic have evaluated oral cannabinoids, not the plant form. “So, what we’re studying is vastly different from what our patients are using,” she said.

The most solid indication clinicians have for recommending medical marijuana is for chronic pain, and the most common condition studied has been neuropathy.

“Most evidence compares cannabinoid to placebo,” said Dr. Grossman, primary care lead for behavioral health integration at Cambridge (Mass.) Health Alliance. “There’s almost nothing out there comparing cannabinoid to any other pain-relieving agent that a patient might choose to use.

“A lot of the literature comes from oral synthesized agents,” she continued. “There’s a little bit of science about inhaled forms, but a lot of this is very different from what my patient got last week in a medical marijuana dispensary in Massachusetts.”

Results from a systematic review of 79 studies of cannabinoids for medical use in 6,462 study participants showed that, compared with placebo, cannabinoids were associated with a greater average number of patients showing a complete nausea and vomiting response (47% vs. 20%; odds ratio, 3.82), reduction in pain (37% vs. 31%; OR, 1.41), a greater average reduction in numerical rating scale pain assessment (on a 0- to 10-point scale; weighted mean difference of –0.46), and average reduction in the Ashworth spasticity scale (–0.36) (JAMA 2015 Jun 23-30;313[24]:2456-73).

A separate meta-analysis of studies compared inhaled cannabis sativa to placebo for chronic painful neuropathy. The researchers found that those patients who used inhaled cannabis sativa were 3.2 times more likely to achieve a 30% or greater reduction in pain, compared with those in the placebo group (J. Pain 2015 Dec;16[12]:1221-32).

However, Dr. Grossman cautioned that the number of patients studied was fewer than 200, “so, you could argue that this is a body of knowledge where the jury is still out.”

According to a 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences titled, “The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids,” another area in which the knowledge base is less solid is the use of oral cannabinoids for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

“There’s a reasonable amount of evidence showing that some of these are better than placebo for relief of these symptoms,” Dr. Grossman said. “That said, the jury’s out as to whether they are any better than our other antiemetic agents. And there are no studies comparing them to neurokinin-1 inhibitors, which are the newest class of drug often used by oncologists for this indication. There is also no good evidence about inhaled plant cannabis.”

Studies of oral cannabinoids for multiple-sclerosis–related spasticity have demonstrated a small improvement on patient-reported spasticity (less than 1 point on a 10-point scale), but there was no improvement in clinician-reported outcomes. At the same time, their use for weight loss/anorexia in HIV “is very limited, and there are no studies of plant-derived cannabis,” Dr. Grossman said.

According to the National Academy of Sciences report, some evidence supports the use of oral cannabinoids for short-term sleep outcomes in patients with chronic diseases such as fibromyalgia and MS. One small study of oral cannabinoid for anxiety found that it improved social anxiety symptoms on the public speaking test, but there have been no studies using inhaled cannabinoids/marijuana.

The health risks of medical marijuana are largely unknown, Dr. Grossman said, noting that most evidence on longer‐term health risks comes from epidemiologic studies of recreational cannabis users.

“Medical marijuana users tend to be older and tend to be sicker,” she said. “We don’t know anything about the long-term effects in that sicker population.”

Among healthier people, Dr. Grossman continued, cannabis use is associated with increased risk of cough, wheeze, and sputum/phlegm. “There’s also an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,” she said. “That is certainly a concern in places where they’re legalizing marijuana.”

Cannabis use is associated with lower neonatal birth weight, case reports/series of unintentional pediatric ingestions, and a possible increase in suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and completed suicides.

“The evidence is very limited regarding associations with myocardial infarction, stroke, COPD, and mortality,” she added. “We don’t really know.”

Dr. Grossman reported having no financial disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Hold your breath

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

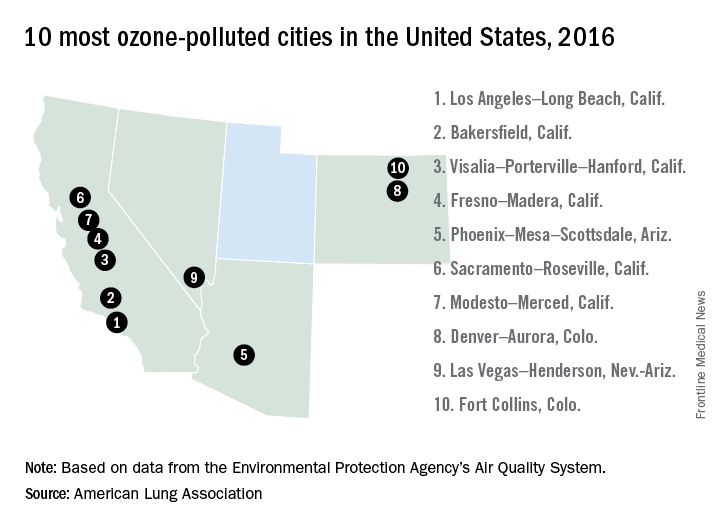

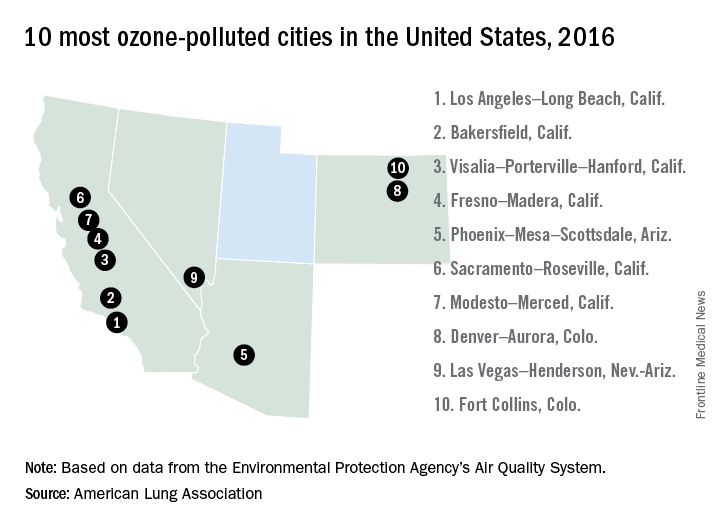

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.”

– U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health.

According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

And yet, nonpolluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8 The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is a former member of the board of directors of the National Wildlife Federation and coauthor of group’s report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.” In 2006, Dr. Van Susteren sought the Democratic nomination for a U.S. Senate seat in Maryland. She also founded Lucky Planet Foods, a company that provides plant-based, low carbon foods.

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686.

2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84.

3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404.

4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82.

5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83.

6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92.

7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25.

8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506.

9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5.

10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003.

11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.

Can a nomogram foretell invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma?

The diagnosis of solitary peripheral subsolid nodule carries with it an undefined risk of invasive pulmonary carcinoma, but clinicians have not had a tool that can help guide their planning for surgery. However, researchers in China have developed a nomogram that they said may aid clinicians to predict the risk of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in these patients.

“Validation by the use of bootstrap resampling revealed optimal discrimination and calibration, indicating that the nomogram may have clinical utility,” said Chenghua Jin, MD, and Jinlin Cao, MD, of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and coauthors. They reported their findings in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:42-9).

The nomogram accounts for the following factors: computed tomography attenuation; nodule size; spiculation; signs of vascular convergence; pleural tags; and solid proportion. “The nomogram showed a robust discrimination with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.894,” Dr. Jin and coauthors reported. An area under the curve of 1 is equivalent to 100%, so the area under the curve this study reported shows close to 90% accuracy.

The study involved a retrospective analysis of 273 consecutive patients who had resection of a solitary peripheral subsolid nodule at Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2013 to December 2014. Subsolid pulmonary nodules include pure ground-glass nodules and part-solid nodules that feature both solid and ground-glass components. “The optimal management of patients with a subsolid nodule is of growing clinical concern, because the most common diagnosis for resected subsolid nodules is lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Jin and colleagues indicated.

Of the study population, 58% were diagnosed with invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Other diagnoses within the group were benign (13%), atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (1%), adenocarcinoma in situ (6.5%) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (21%).

Results of the multivariable analyses showed that invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma correlated with the following characteristics: lesion size; spiculation; vascular convergence; and pleural tag. Factors that were not significant included age, family history of lung cancer, CT attenuation, and solid proportion. However, the researchers did include CT attenuation, along with solid proportion, in the final regression analysis based on their contributions to the statistical analysis.

For the model, CT attenuation of –500 to –200 Hounsfield units carried an odds ratio of 1.690 (P = .228) while CT attenuation greater than –200 HU had an OR of 1.791 (P = .645). Positive spiculation had an OR of 3.312 (no P value given) and negative vascular convergence an OR of 0.300 (no P value given).

While a number of prediction models have been devised and validated to evaluate the likelihood of malignancy in pulmonary nodules, they have not given subsolid nodules “specific or detailed consideration,” Dr. Jin and and coauthors said. “To our knowledge, this study was the first to construct a quantitative nomogram to predict the probability of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in patients with subsolid nodules,” the researchers wrote.

One limitation of the study is its selection bias toward patients with a greater probability of having a malignancy. Also, validation of the nomogram requires external analysis with additional databases from other countries and with more diverse ethnic groups. Another shortcoming is the retrospective nature of the study and a small number of patients who had positron emission tomography. “Further data collection, wider geographic recruitment, and incorporation of positron emission tomography results and some molecular factors could improve this model for future use,” Dr. Jin and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Jin and Dr. Cao had no relevant financial disclosures. The study received funding from the Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Plan.

The nomogram Dr. Jin and coauthors present can be a valuable tool for determining the extent of resection of subsolid pulmonary nodules and to distinguish invasive from preinvasive disease where preoperative needle biopsy and intraopertiave frozen section typically cannot, Bryan Burt, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:460-1).

“However,” Dr. Burt added, “as the accuracy of frozen section for this disease improves, as it has in select centers, the clinical utility of such a nomogram will diminish.”

Use of the nomogram relies on experienced chest radiologists to aid in scoring variables and a validation methodology that a retrospective trial cannot meet, Dr. Burt said. “Of note, this nomogram was constructed from a dataset composed of only surgically resected lesions, and it will be imperative to validate these methods among a larger cohort of individuals with subsolid pulmonary nodules treated both surgically and nonsurgically, ideally in a prospective trial,” Dr. Burt concluded.

Dr. Burt had no relevant financial disclosures.

The nomogram Dr. Jin and coauthors present can be a valuable tool for determining the extent of resection of subsolid pulmonary nodules and to distinguish invasive from preinvasive disease where preoperative needle biopsy and intraopertiave frozen section typically cannot, Bryan Burt, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:460-1).

“However,” Dr. Burt added, “as the accuracy of frozen section for this disease improves, as it has in select centers, the clinical utility of such a nomogram will diminish.”

Use of the nomogram relies on experienced chest radiologists to aid in scoring variables and a validation methodology that a retrospective trial cannot meet, Dr. Burt said. “Of note, this nomogram was constructed from a dataset composed of only surgically resected lesions, and it will be imperative to validate these methods among a larger cohort of individuals with subsolid pulmonary nodules treated both surgically and nonsurgically, ideally in a prospective trial,” Dr. Burt concluded.

Dr. Burt had no relevant financial disclosures.

The nomogram Dr. Jin and coauthors present can be a valuable tool for determining the extent of resection of subsolid pulmonary nodules and to distinguish invasive from preinvasive disease where preoperative needle biopsy and intraopertiave frozen section typically cannot, Bryan Burt, MD, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:460-1).

“However,” Dr. Burt added, “as the accuracy of frozen section for this disease improves, as it has in select centers, the clinical utility of such a nomogram will diminish.”

Use of the nomogram relies on experienced chest radiologists to aid in scoring variables and a validation methodology that a retrospective trial cannot meet, Dr. Burt said. “Of note, this nomogram was constructed from a dataset composed of only surgically resected lesions, and it will be imperative to validate these methods among a larger cohort of individuals with subsolid pulmonary nodules treated both surgically and nonsurgically, ideally in a prospective trial,” Dr. Burt concluded.

Dr. Burt had no relevant financial disclosures.

The diagnosis of solitary peripheral subsolid nodule carries with it an undefined risk of invasive pulmonary carcinoma, but clinicians have not had a tool that can help guide their planning for surgery. However, researchers in China have developed a nomogram that they said may aid clinicians to predict the risk of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in these patients.

“Validation by the use of bootstrap resampling revealed optimal discrimination and calibration, indicating that the nomogram may have clinical utility,” said Chenghua Jin, MD, and Jinlin Cao, MD, of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and coauthors. They reported their findings in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:42-9).

The nomogram accounts for the following factors: computed tomography attenuation; nodule size; spiculation; signs of vascular convergence; pleural tags; and solid proportion. “The nomogram showed a robust discrimination with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.894,” Dr. Jin and coauthors reported. An area under the curve of 1 is equivalent to 100%, so the area under the curve this study reported shows close to 90% accuracy.

The study involved a retrospective analysis of 273 consecutive patients who had resection of a solitary peripheral subsolid nodule at Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2013 to December 2014. Subsolid pulmonary nodules include pure ground-glass nodules and part-solid nodules that feature both solid and ground-glass components. “The optimal management of patients with a subsolid nodule is of growing clinical concern, because the most common diagnosis for resected subsolid nodules is lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Jin and colleagues indicated.

Of the study population, 58% were diagnosed with invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Other diagnoses within the group were benign (13%), atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (1%), adenocarcinoma in situ (6.5%) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (21%).

Results of the multivariable analyses showed that invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma correlated with the following characteristics: lesion size; spiculation; vascular convergence; and pleural tag. Factors that were not significant included age, family history of lung cancer, CT attenuation, and solid proportion. However, the researchers did include CT attenuation, along with solid proportion, in the final regression analysis based on their contributions to the statistical analysis.

For the model, CT attenuation of –500 to –200 Hounsfield units carried an odds ratio of 1.690 (P = .228) while CT attenuation greater than –200 HU had an OR of 1.791 (P = .645). Positive spiculation had an OR of 3.312 (no P value given) and negative vascular convergence an OR of 0.300 (no P value given).

While a number of prediction models have been devised and validated to evaluate the likelihood of malignancy in pulmonary nodules, they have not given subsolid nodules “specific or detailed consideration,” Dr. Jin and and coauthors said. “To our knowledge, this study was the first to construct a quantitative nomogram to predict the probability of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in patients with subsolid nodules,” the researchers wrote.

One limitation of the study is its selection bias toward patients with a greater probability of having a malignancy. Also, validation of the nomogram requires external analysis with additional databases from other countries and with more diverse ethnic groups. Another shortcoming is the retrospective nature of the study and a small number of patients who had positron emission tomography. “Further data collection, wider geographic recruitment, and incorporation of positron emission tomography results and some molecular factors could improve this model for future use,” Dr. Jin and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Jin and Dr. Cao had no relevant financial disclosures. The study received funding from the Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Plan.

The diagnosis of solitary peripheral subsolid nodule carries with it an undefined risk of invasive pulmonary carcinoma, but clinicians have not had a tool that can help guide their planning for surgery. However, researchers in China have developed a nomogram that they said may aid clinicians to predict the risk of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in these patients.

“Validation by the use of bootstrap resampling revealed optimal discrimination and calibration, indicating that the nomogram may have clinical utility,” said Chenghua Jin, MD, and Jinlin Cao, MD, of Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, and coauthors. They reported their findings in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:42-9).

The nomogram accounts for the following factors: computed tomography attenuation; nodule size; spiculation; signs of vascular convergence; pleural tags; and solid proportion. “The nomogram showed a robust discrimination with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.894,” Dr. Jin and coauthors reported. An area under the curve of 1 is equivalent to 100%, so the area under the curve this study reported shows close to 90% accuracy.

The study involved a retrospective analysis of 273 consecutive patients who had resection of a solitary peripheral subsolid nodule at Zhejiang University School of Medicine from January 2013 to December 2014. Subsolid pulmonary nodules include pure ground-glass nodules and part-solid nodules that feature both solid and ground-glass components. “The optimal management of patients with a subsolid nodule is of growing clinical concern, because the most common diagnosis for resected subsolid nodules is lung adenocarcinoma,” Dr. Jin and colleagues indicated.

Of the study population, 58% were diagnosed with invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Other diagnoses within the group were benign (13%), atypical adenomatous hyperplasia (1%), adenocarcinoma in situ (6.5%) and minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (21%).

Results of the multivariable analyses showed that invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma correlated with the following characteristics: lesion size; spiculation; vascular convergence; and pleural tag. Factors that were not significant included age, family history of lung cancer, CT attenuation, and solid proportion. However, the researchers did include CT attenuation, along with solid proportion, in the final regression analysis based on their contributions to the statistical analysis.

For the model, CT attenuation of –500 to –200 Hounsfield units carried an odds ratio of 1.690 (P = .228) while CT attenuation greater than –200 HU had an OR of 1.791 (P = .645). Positive spiculation had an OR of 3.312 (no P value given) and negative vascular convergence an OR of 0.300 (no P value given).

While a number of prediction models have been devised and validated to evaluate the likelihood of malignancy in pulmonary nodules, they have not given subsolid nodules “specific or detailed consideration,” Dr. Jin and and coauthors said. “To our knowledge, this study was the first to construct a quantitative nomogram to predict the probability of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma in patients with subsolid nodules,” the researchers wrote.

One limitation of the study is its selection bias toward patients with a greater probability of having a malignancy. Also, validation of the nomogram requires external analysis with additional databases from other countries and with more diverse ethnic groups. Another shortcoming is the retrospective nature of the study and a small number of patients who had positron emission tomography. “Further data collection, wider geographic recruitment, and incorporation of positron emission tomography results and some molecular factors could improve this model for future use,” Dr. Jin and coauthors concluded.

Dr. Jin and Dr. Cao had no relevant financial disclosures. The study received funding from the Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Plan.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE JOURNAL OF THORACIC AND CARDIOVASCULAR SURGERY

Key clinical point: Investigators developed a nomogram that may help predict the risk of invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma for patients with a solitary peripheral subsolid nodule.

Major finding: This nomogram may help clinicians individualize each patient’s prognosis for invasive pulmonary adenocarcinoma and develop treatment plans accordingly.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 273 consecutive patients who had surgery to remove a solitary peripheral subsolid nodule at a single center.

Disclosure: The investigators received support from the Zhejiang Province Science and Technology Plan. Dr. Jin and Dr. Cao reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Will genome editing advance animal-to-human transplantation?

Advances in gene editing are pushing the possibility of raising pigs for organs that may be transplanted into humans with immunosuppression regimens comparable to those now used in human-to-human transplants, coauthors James Butler, MD, and A. Joseph Tector, MD, PhD, stated in an expert opinion in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:488-92).

Developments in genome editing could bring new approaches to management of cardiopulmonary diseases, Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector noted. “Recently, cardiac-specific and lung-specific applications have been described, which will allow for the rapid creation of new models of heart and lung disease,” they said. Specifically, they noted gene targeting might eventually offer a way to treat challenging genetic problems “like the heterogeneous nature of nonsquamous cell lung cancer.”

Dr. Butler is with the department of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and Dr. Tector is with the department of surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

CRISPR technology has been used in developing multiple gene knockout pigs and neutralizing three separate porcine genes that encode human xenoantigens in a single reaction, leading to efficient methods for creating pigs with multiple genetic modifications.

According to the website of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Mass., where researchers perfected the system to work in eukaryotes, CRISPR works by using short RNA sequences designed by researchers to guide the system to matching sequences of DNA. When the target DNA is found, Cas9 – one of the enzymes produced by the CRISPR system – binds to the DNA and cuts it, shutting the targeted gene off.

“By facilitating high-throughput model creation, CRISPR has elucidated which modifications are necessary and which are not; despite the ability to alter many loci concurrently, recent evidence has implicated three porcine genes that are responsible for the majority of human-antiporcine humoral immunity,” Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector wrote.

Those genes are the Gal[alpha]1-3 epitope (Gal-alpha), CMAH and B4GaINT2 genes. “Each of these three genes is expressed in pigs but has been evolutionarily silenced in humans,” the coauthors added.

While CRISPR genome editing has yet to reach its full potential, researchers and clinicians should pay attention, according to Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector.

More recent modifications of CRISPR technology have shown promise in not just knocking out or turning off specific genes, but rather guiding directed replacement of genes with researcher-designed substitutes. This can enable permanent transformation of functional genes with altered behavior, according to the Broad Institute website.

Dr. Tector disclosed he has received funding from United Therapeutics and founded Xenobridge with patents for xenotransplantation. Dr. Butler has no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

CRISPR and CRISPR-associated proteins have emerged as effective genome editing techniques that may lead to cardiac and lung models and possibly xenotransplantation, Ari A. Mennander, MD, PhD, of the Tampere (Finland) University Heart Hospital, said in his invited commentary (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153:492).

The concept Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector discuss involves not using antibodies to ameliorate porcine antibodies that cause rejection in humans, but rather reengineering the genetic composition of pigs to eliminate those antibodies. “According to the wildest of dreams, these genes affecting porcine glycan expression may be silenced, and the human–antiporcine humoral immunity is controlled down to the level comparable with human allograft rejection,” Dr. Mennander said.

However, such a breakthrough carries with it consequences, Dr. Mennander said. “Should one worry about the induction of zoonosis, as well as the ethical aspects of transplanting the patient a whole organ of a pig? Would even a successful xenotransplant program seriously compete with artificial hearts or allografts?” Embracing the method too early would open its advocates to ridicule, he said.

“We are to applaud the researchers for ever-lasting and exemplary enthusiasm for a futuristic new surgical solution; the future may lie as much in current clinical solutions as in innovative discoveries based on persistent scientific experiments,” Dr. Mennander said.

Dr. Mennander had no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Advances in gene editing are pushing the possibility of raising pigs for organs that may be transplanted into humans with immunosuppression regimens comparable to those now used in human-to-human transplants, coauthors James Butler, MD, and A. Joseph Tector, MD, PhD, stated in an expert opinion in the February issue of the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2017;153:488-92).

Developments in genome editing could bring new approaches to management of cardiopulmonary diseases, Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector noted. “Recently, cardiac-specific and lung-specific applications have been described, which will allow for the rapid creation of new models of heart and lung disease,” they said. Specifically, they noted gene targeting might eventually offer a way to treat challenging genetic problems “like the heterogeneous nature of nonsquamous cell lung cancer.”

Dr. Butler is with the department of surgery at Indiana University, Indianapolis, and Dr. Tector is with the department of surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

CRISPR technology has been used in developing multiple gene knockout pigs and neutralizing three separate porcine genes that encode human xenoantigens in a single reaction, leading to efficient methods for creating pigs with multiple genetic modifications.

According to the website of the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, Mass., where researchers perfected the system to work in eukaryotes, CRISPR works by using short RNA sequences designed by researchers to guide the system to matching sequences of DNA. When the target DNA is found, Cas9 – one of the enzymes produced by the CRISPR system – binds to the DNA and cuts it, shutting the targeted gene off.

“By facilitating high-throughput model creation, CRISPR has elucidated which modifications are necessary and which are not; despite the ability to alter many loci concurrently, recent evidence has implicated three porcine genes that are responsible for the majority of human-antiporcine humoral immunity,” Dr. Butler and Dr. Tector wrote.